User login

Molluscum Contagiosum Superimposed on Lymphangioma Circumscriptum

To the Editor:

Lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) is a benign malformation of the lymphatic system.1 It is postulated to arise from abnormal lymphatic cisterns, and it grows separately from the normal lymphatic system. These cisterns are connected to malformed dermal lymphatic channels, and the contraction of smooth muscles lining cisterns will cause dilatation of connected lymphatic channels in the papillary dermis due to back pressure,1,2 which causes a classic LC manifestation characterized by multiple translucent, sometimes red-brown, small vesicles grouped together. Lymphangioma circumscriptum can be difficult to differentiate from molluscum contagiosum (MC) due to the similar morphology.1 We present a notable case of MC superimposed on LC.

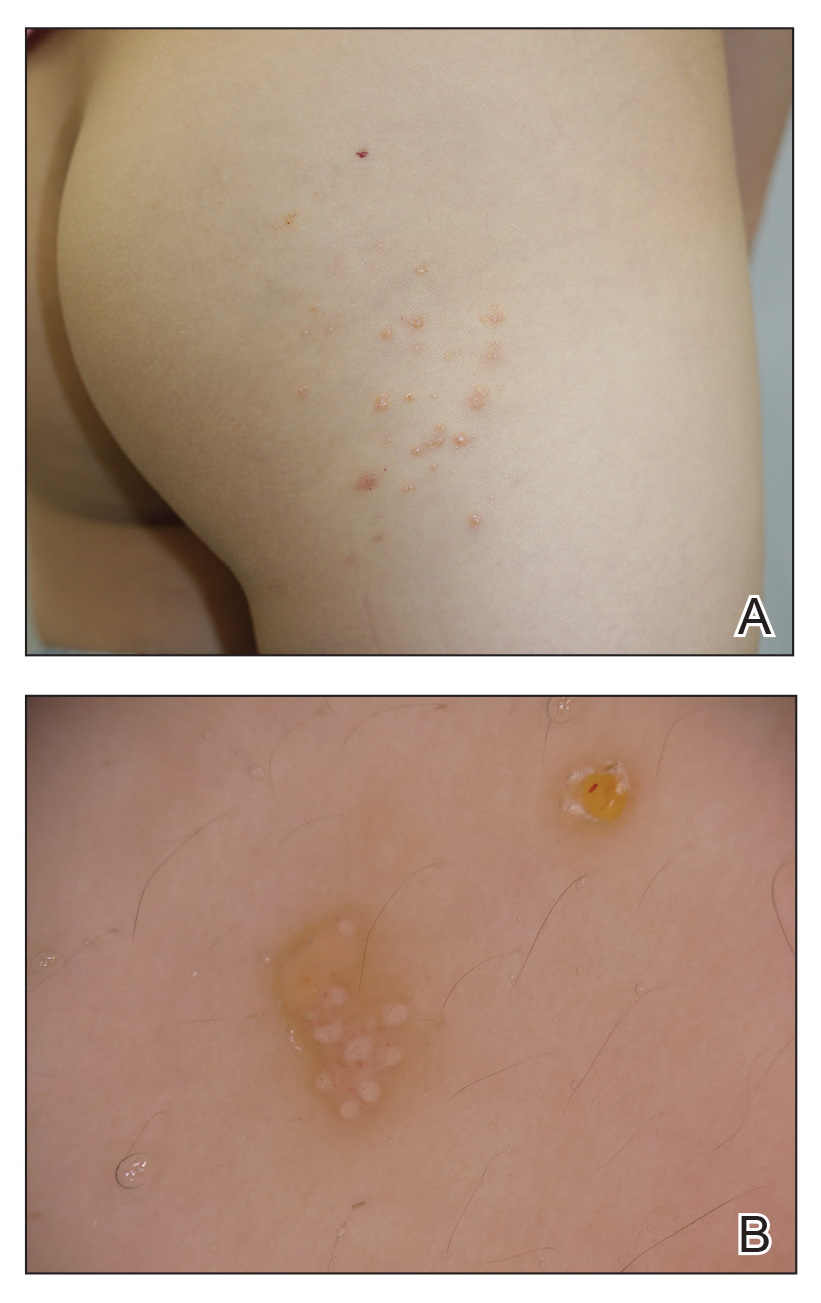

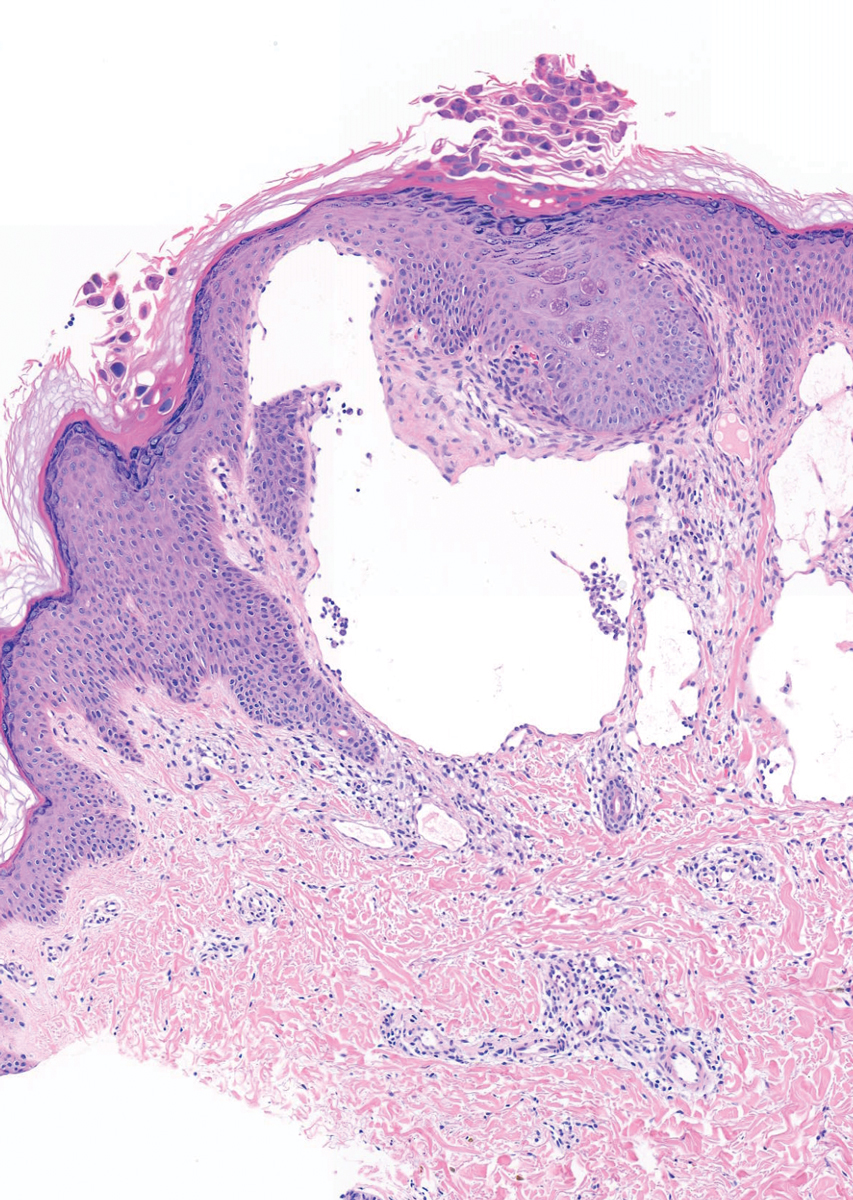

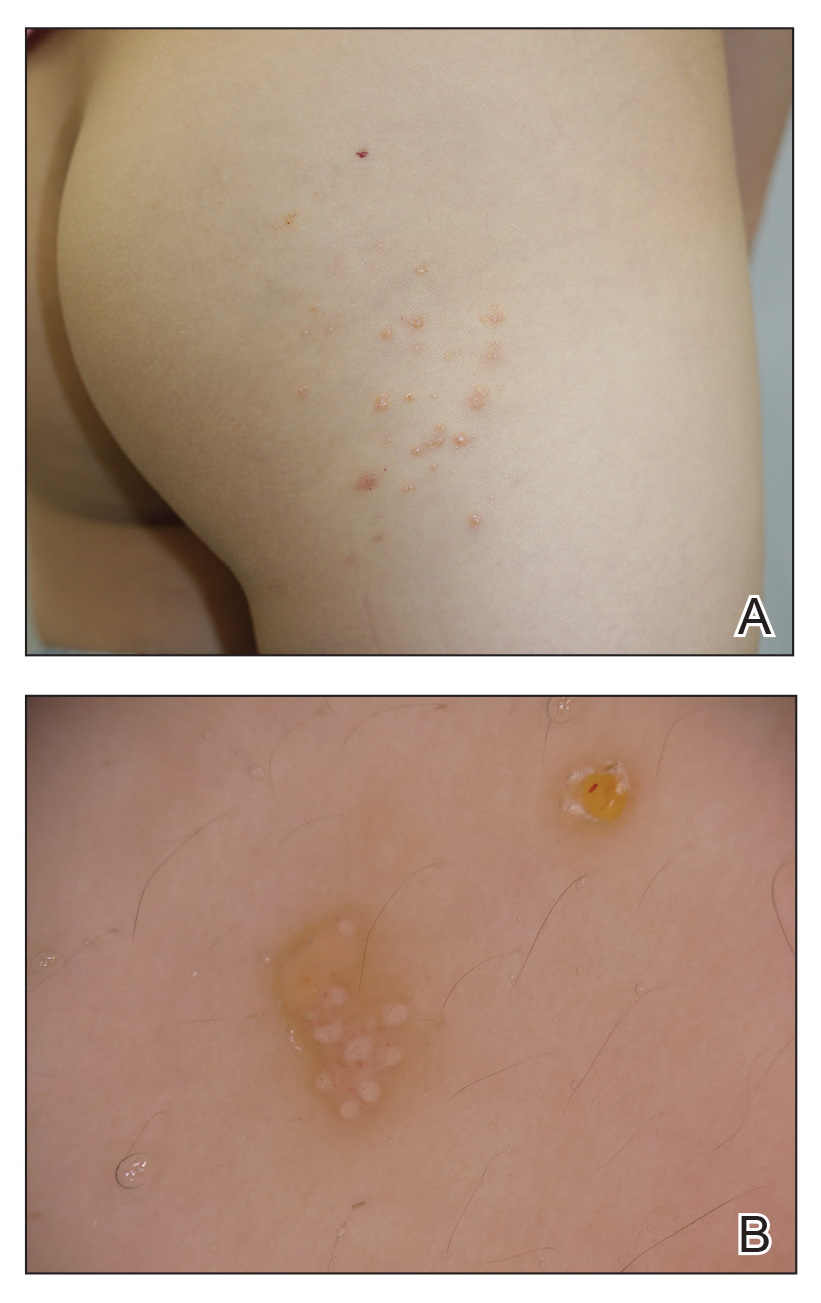

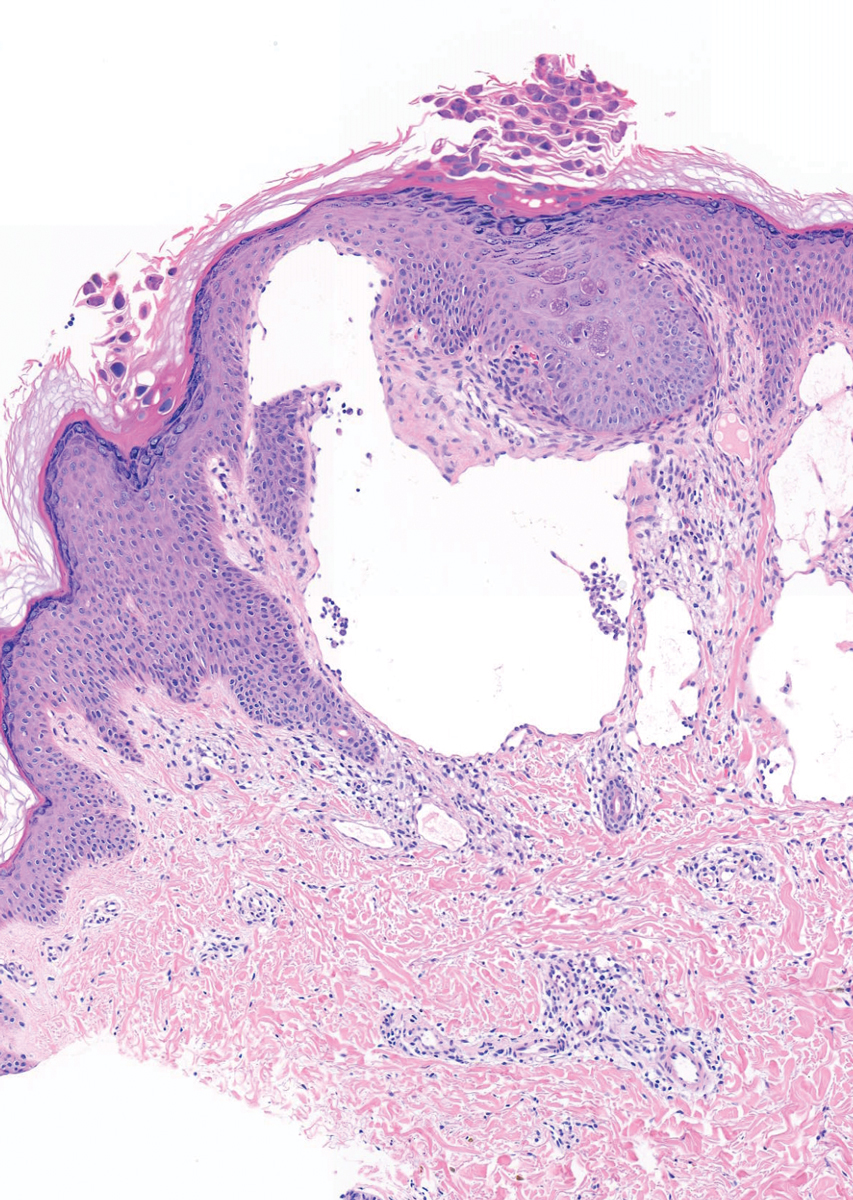

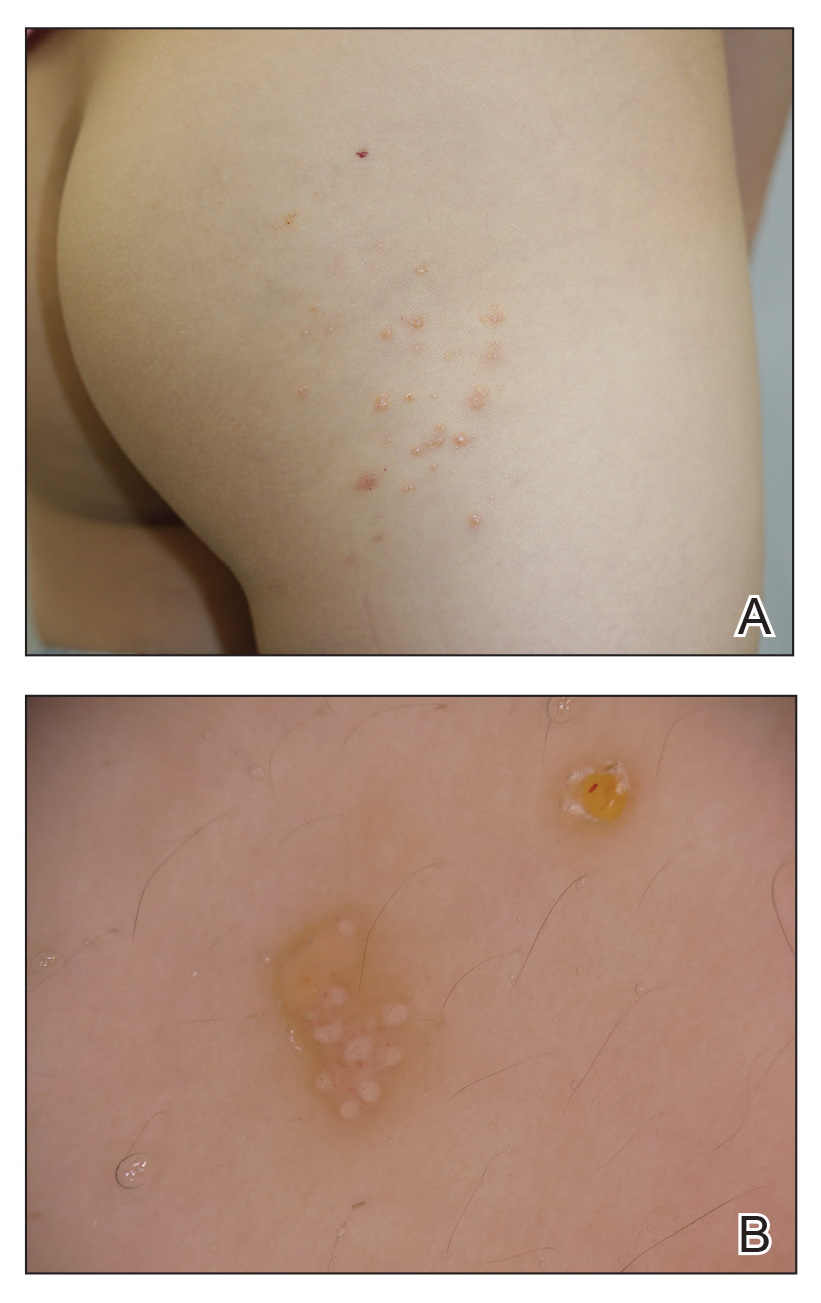

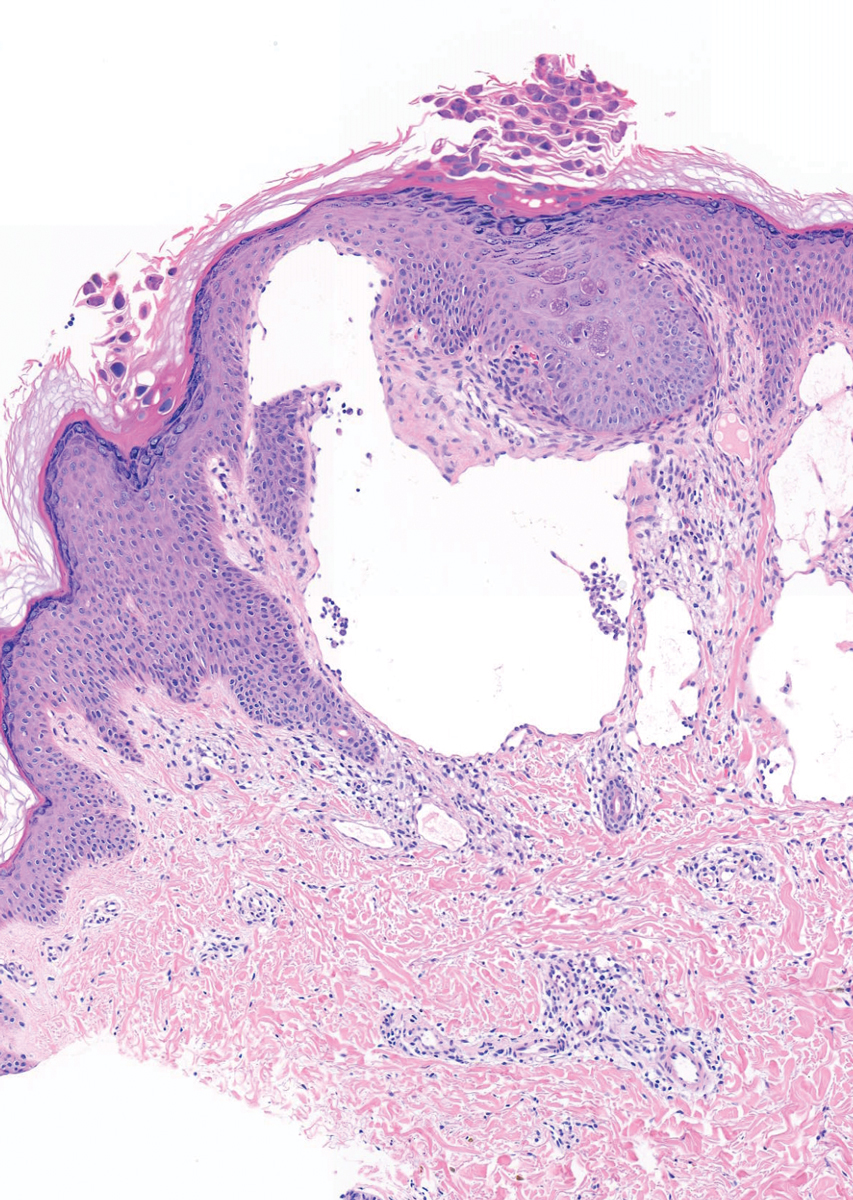

A 6-year-old girl presented with multiple grouped, clear, vesicular papules on the right buttock of 18 months’ duration. Some of the papules showed tiny whitish pearl-like particles on the top (Figure 1). Similar lesions were not present elsewhere on the body. She had no underlying disease and did not have a history of procedure, edema, or malformation of the lower extremities. Histopathology from one of the lesions showed dilated cystic lymphatic spaces in the papillary dermis lined with flattened endothelium and cup-shaped downward proliferation of the epidermis with presence of large intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies—features of both LC and MC (Figure 2). We waited 4 additional months for the MC lesions to self-resolve, but they persisted. The patient’s mother strongly requested for their removal, and the residual MC lesions were carefully removed by CO2 laser. To prevent unnecessary physical damage to underlying LC lesions and minimize scarring, we opted to use the CO2 laser and not simple curettage. She currently is under periodic observation with no signs of clinical recurrence of MC, but the LC lesions naturally persisted.

Due to its vesicular and sometimes warty appearance, LC can sometimes be hard to differentiate from MC. In one report, a vesicular plaquelike lesion on the trunk initially was misdiagnosed and treated as MC but was histologically confirmed as LC several years later.3 Our case demonstrates the coexistence of MC and LC. Although this phenomenon may be coincidental, we have not noticed any additional MC lesions on the body and MC only existed over the LC lesions, implying a possible pathophysiologic relationship. It is unlikely that MC might have preceded the development of LC. Although acquired LC exists, it has mostly been reported in the genital region of patients with conditions leading to lymphatic obstruction such as surgery, radiation therapy, malignancy, or serious infections.4 Because our patient developed lesions at an early age without any remarkable medical history, it is likely that she had congenital LC that was secondarily infected by the MC virus. Vesicular lesions in LC are known to rupture easily and may serve as a vulnerable entry site for pathogens. Subsequent secondary bacterial infections are common, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most prominent entity.1 However, secondary viral infection rarely is reported. It is possible that the abnormally dilated lymphatic channels of LC that lack communication with the normal lymphatic system have contributed to an LC site-specific vulnerability to MC virus. Further studies and subsequent reports are required to confirm this hypothesis.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04226.x

- Fatima S, Uddin N, Idrees R, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: clinicopathological spectrum of 29 cases. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:658-661. doi:09.2015/JCPSP.658661

- Patel GA, Siperstein RD, Ragi G, Schwartz RA. Zosteriform lymphangioma circumscriptum. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2009;18:179-182.

- Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E482-E487. doi:10.1111/ijd.13264

To the Editor:

Lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) is a benign malformation of the lymphatic system.1 It is postulated to arise from abnormal lymphatic cisterns, and it grows separately from the normal lymphatic system. These cisterns are connected to malformed dermal lymphatic channels, and the contraction of smooth muscles lining cisterns will cause dilatation of connected lymphatic channels in the papillary dermis due to back pressure,1,2 which causes a classic LC manifestation characterized by multiple translucent, sometimes red-brown, small vesicles grouped together. Lymphangioma circumscriptum can be difficult to differentiate from molluscum contagiosum (MC) due to the similar morphology.1 We present a notable case of MC superimposed on LC.

A 6-year-old girl presented with multiple grouped, clear, vesicular papules on the right buttock of 18 months’ duration. Some of the papules showed tiny whitish pearl-like particles on the top (Figure 1). Similar lesions were not present elsewhere on the body. She had no underlying disease and did not have a history of procedure, edema, or malformation of the lower extremities. Histopathology from one of the lesions showed dilated cystic lymphatic spaces in the papillary dermis lined with flattened endothelium and cup-shaped downward proliferation of the epidermis with presence of large intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies—features of both LC and MC (Figure 2). We waited 4 additional months for the MC lesions to self-resolve, but they persisted. The patient’s mother strongly requested for their removal, and the residual MC lesions were carefully removed by CO2 laser. To prevent unnecessary physical damage to underlying LC lesions and minimize scarring, we opted to use the CO2 laser and not simple curettage. She currently is under periodic observation with no signs of clinical recurrence of MC, but the LC lesions naturally persisted.

Due to its vesicular and sometimes warty appearance, LC can sometimes be hard to differentiate from MC. In one report, a vesicular plaquelike lesion on the trunk initially was misdiagnosed and treated as MC but was histologically confirmed as LC several years later.3 Our case demonstrates the coexistence of MC and LC. Although this phenomenon may be coincidental, we have not noticed any additional MC lesions on the body and MC only existed over the LC lesions, implying a possible pathophysiologic relationship. It is unlikely that MC might have preceded the development of LC. Although acquired LC exists, it has mostly been reported in the genital region of patients with conditions leading to lymphatic obstruction such as surgery, radiation therapy, malignancy, or serious infections.4 Because our patient developed lesions at an early age without any remarkable medical history, it is likely that she had congenital LC that was secondarily infected by the MC virus. Vesicular lesions in LC are known to rupture easily and may serve as a vulnerable entry site for pathogens. Subsequent secondary bacterial infections are common, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most prominent entity.1 However, secondary viral infection rarely is reported. It is possible that the abnormally dilated lymphatic channels of LC that lack communication with the normal lymphatic system have contributed to an LC site-specific vulnerability to MC virus. Further studies and subsequent reports are required to confirm this hypothesis.

To the Editor:

Lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) is a benign malformation of the lymphatic system.1 It is postulated to arise from abnormal lymphatic cisterns, and it grows separately from the normal lymphatic system. These cisterns are connected to malformed dermal lymphatic channels, and the contraction of smooth muscles lining cisterns will cause dilatation of connected lymphatic channels in the papillary dermis due to back pressure,1,2 which causes a classic LC manifestation characterized by multiple translucent, sometimes red-brown, small vesicles grouped together. Lymphangioma circumscriptum can be difficult to differentiate from molluscum contagiosum (MC) due to the similar morphology.1 We present a notable case of MC superimposed on LC.

A 6-year-old girl presented with multiple grouped, clear, vesicular papules on the right buttock of 18 months’ duration. Some of the papules showed tiny whitish pearl-like particles on the top (Figure 1). Similar lesions were not present elsewhere on the body. She had no underlying disease and did not have a history of procedure, edema, or malformation of the lower extremities. Histopathology from one of the lesions showed dilated cystic lymphatic spaces in the papillary dermis lined with flattened endothelium and cup-shaped downward proliferation of the epidermis with presence of large intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies—features of both LC and MC (Figure 2). We waited 4 additional months for the MC lesions to self-resolve, but they persisted. The patient’s mother strongly requested for their removal, and the residual MC lesions were carefully removed by CO2 laser. To prevent unnecessary physical damage to underlying LC lesions and minimize scarring, we opted to use the CO2 laser and not simple curettage. She currently is under periodic observation with no signs of clinical recurrence of MC, but the LC lesions naturally persisted.

Due to its vesicular and sometimes warty appearance, LC can sometimes be hard to differentiate from MC. In one report, a vesicular plaquelike lesion on the trunk initially was misdiagnosed and treated as MC but was histologically confirmed as LC several years later.3 Our case demonstrates the coexistence of MC and LC. Although this phenomenon may be coincidental, we have not noticed any additional MC lesions on the body and MC only existed over the LC lesions, implying a possible pathophysiologic relationship. It is unlikely that MC might have preceded the development of LC. Although acquired LC exists, it has mostly been reported in the genital region of patients with conditions leading to lymphatic obstruction such as surgery, radiation therapy, malignancy, or serious infections.4 Because our patient developed lesions at an early age without any remarkable medical history, it is likely that she had congenital LC that was secondarily infected by the MC virus. Vesicular lesions in LC are known to rupture easily and may serve as a vulnerable entry site for pathogens. Subsequent secondary bacterial infections are common, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most prominent entity.1 However, secondary viral infection rarely is reported. It is possible that the abnormally dilated lymphatic channels of LC that lack communication with the normal lymphatic system have contributed to an LC site-specific vulnerability to MC virus. Further studies and subsequent reports are required to confirm this hypothesis.

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04226.x

- Fatima S, Uddin N, Idrees R, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: clinicopathological spectrum of 29 cases. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:658-661. doi:09.2015/JCPSP.658661

- Patel GA, Siperstein RD, Ragi G, Schwartz RA. Zosteriform lymphangioma circumscriptum. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2009;18:179-182.

- Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E482-E487. doi:10.1111/ijd.13264

- Patel GA, Schwartz RA. Cutaneous lymphangioma circumscriptum: frog spawn on the skin. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1290-1295. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04226.x

- Fatima S, Uddin N, Idrees R, et al. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: clinicopathological spectrum of 29 cases. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015;25:658-661. doi:09.2015/JCPSP.658661

- Patel GA, Siperstein RD, Ragi G, Schwartz RA. Zosteriform lymphangioma circumscriptum. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2009;18:179-182.

- Chang MB, Newman CC, Davis MD, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasia (lymphangioma circumscriptum) of the vulva: clinicopathologic study of 11 patients from a single institution and 67 from the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E482-E487. doi:10.1111/ijd.13264

Practice Points

- Lymphangioma circumscriptum (LC) is a benign malformation of the lymphatic system that can be misdiagnosed as molluscum contagiosum (MC).

- Secondary infection of LC is common, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most common entity, but MC virus also can be secondarily infected.

Genital Primary Herpetic Infection With Concurrent Hepatitis in an Infant

To the Editor:

Cutaneous herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection generally involves mucocutaneous junctions, but virtually any area of the skin can be affected.1 When the genital area of adult patients is affected, the disease usually is sexually transmitted and mainly caused by HSV-2. In infants, genital primary herpetic infection is rare and more commonly is caused by HSV-1 than by HSV-2. We report a rare case of genital primary herpetic infection with concurrent hepatitis in an infant.

An 8-month-old infant with no underlying medical problems, including atopic dermatitis, was referred for erythematous grouped vesicles with erosions on the perianal area of 4 days’ duration (Figure). The skin color appeared normal, not icterus. She also had a fever (temperature, 37.9 °C), and her urination pattern had changed from normal to frequent leakage, possibly owing to pain related to the eroded lesions. Physical examination did not reveal palpable inguinal lymph nodes. The oral mucosa was not involved. The patient’s father had a history of recurrent herpetic infection on both the perioral and perianal areas.

A Tzanck smear revealed giant multinucleated cells with multiple inflammatory cells. Laboratory tests revealed marked leukocytosis, elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase, 141 IU/L [reference range, 15 IU/L–60 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 422 IU/L [reference range, 13 IU/L–45 IU/L]), and was positive for herpes simplex viral IgM but negative for herpes simplex viral IgG. A viral culture also demonstrated the growth of HSV. An abdominal ultrasound was normal. Based on the cutaneous and laboratory findings, genital primary herpetic infection with concurrent hepatitis was diagnosed. Intravenous acyclovir 50 mg was administered 3 times daily for 7 days, and a wet dressing with topical mupirocin was employed daily until the skin lesions healed. The fever subsided soon after starting treatment. The liver enzyme counts decreased gradually in serial follow-up (aspartate aminotransferase, 75 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 70 IU/L).

Primary herpetic infection usually is asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur, it is characterized by the sudden onset of painful vesicle clusters over erythematous edematous skin. Lesions can be associated with fever and malaise and may involve the perineum. Urinary symptoms may occur. The average age of onset ranges from 6 months to 4 years. The virus commonly is transmitted by asymptomatic carriers. Autoinoculation from concomitant oral primary herpetic infection or individuals with active herpetic infection is one possible route of transmission. In our patient, we assumed that she acquired the virus from her father during close contact. A diagnosis can be made clinically using direct methods including culture, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction, or indirect methods such as serologic tests.2

Hepatitis secondary to HSV infection is rare, especially in immunocompetent patients. It occurs during primary infection and rarely during recurrent infection with or without concomitant skin lesions.3 Symptoms include fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, leukopenia, coagulopathy, and marked elevation of serum transaminase levels without jaundice. Based on our patient’s elevated liver enzyme levels and virological evidence of acute primary HSV infection, a lack of evidence of other hepatic viral infections, and the presence of herpes simplex viremia, we concluded that this infant had viral hepatitis as a part of the clinical presentation of primary HSV infection. We did not perform a direct liver biopsy considering her age and accompanying risks.4

Primary herpetic infection usually has a benign course and a short duration. In children, the prognosis depends on underlying immunologic status, not a particular type of HSV. In children with atopic dermatitis, primary herpetic infection tends to occur earlier and is more severe. Early treatment with acyclovir is effective; intravenous treatment is not required unless local complications or systemic involvement are present. Long-term follow-up is recommended because of the possibility of recurrence.

Although the possibility of systemic involvement including hepatitis due to HSV infection is low, awareness among dermatologists about primary herpetic infection and its possible complications would be helpful in the diagnosis and treatment, especially for atypical or extensive cases.

- Jenson HB, Shapiro ED. Primary herpes simplex virus infection of a diaper rash. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:1136-1138.

- Batalla A, Flórez A, Dávila P, et al. Genital primary herpes simplexinfection in a 5-month-old infant. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:8.

- Norvell JP, Blei AT, Jovanovic BD, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: an analysis of the published literature and institutional cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1428-1434.

- Chen CK, Wu SH, Huang YC. Herpetic gingivostomatitis with severe hepatitis in a previously healthy child. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:324-325.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection generally involves mucocutaneous junctions, but virtually any area of the skin can be affected.1 When the genital area of adult patients is affected, the disease usually is sexually transmitted and mainly caused by HSV-2. In infants, genital primary herpetic infection is rare and more commonly is caused by HSV-1 than by HSV-2. We report a rare case of genital primary herpetic infection with concurrent hepatitis in an infant.

An 8-month-old infant with no underlying medical problems, including atopic dermatitis, was referred for erythematous grouped vesicles with erosions on the perianal area of 4 days’ duration (Figure). The skin color appeared normal, not icterus. She also had a fever (temperature, 37.9 °C), and her urination pattern had changed from normal to frequent leakage, possibly owing to pain related to the eroded lesions. Physical examination did not reveal palpable inguinal lymph nodes. The oral mucosa was not involved. The patient’s father had a history of recurrent herpetic infection on both the perioral and perianal areas.

A Tzanck smear revealed giant multinucleated cells with multiple inflammatory cells. Laboratory tests revealed marked leukocytosis, elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase, 141 IU/L [reference range, 15 IU/L–60 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 422 IU/L [reference range, 13 IU/L–45 IU/L]), and was positive for herpes simplex viral IgM but negative for herpes simplex viral IgG. A viral culture also demonstrated the growth of HSV. An abdominal ultrasound was normal. Based on the cutaneous and laboratory findings, genital primary herpetic infection with concurrent hepatitis was diagnosed. Intravenous acyclovir 50 mg was administered 3 times daily for 7 days, and a wet dressing with topical mupirocin was employed daily until the skin lesions healed. The fever subsided soon after starting treatment. The liver enzyme counts decreased gradually in serial follow-up (aspartate aminotransferase, 75 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 70 IU/L).

Primary herpetic infection usually is asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur, it is characterized by the sudden onset of painful vesicle clusters over erythematous edematous skin. Lesions can be associated with fever and malaise and may involve the perineum. Urinary symptoms may occur. The average age of onset ranges from 6 months to 4 years. The virus commonly is transmitted by asymptomatic carriers. Autoinoculation from concomitant oral primary herpetic infection or individuals with active herpetic infection is one possible route of transmission. In our patient, we assumed that she acquired the virus from her father during close contact. A diagnosis can be made clinically using direct methods including culture, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction, or indirect methods such as serologic tests.2

Hepatitis secondary to HSV infection is rare, especially in immunocompetent patients. It occurs during primary infection and rarely during recurrent infection with or without concomitant skin lesions.3 Symptoms include fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, leukopenia, coagulopathy, and marked elevation of serum transaminase levels without jaundice. Based on our patient’s elevated liver enzyme levels and virological evidence of acute primary HSV infection, a lack of evidence of other hepatic viral infections, and the presence of herpes simplex viremia, we concluded that this infant had viral hepatitis as a part of the clinical presentation of primary HSV infection. We did not perform a direct liver biopsy considering her age and accompanying risks.4

Primary herpetic infection usually has a benign course and a short duration. In children, the prognosis depends on underlying immunologic status, not a particular type of HSV. In children with atopic dermatitis, primary herpetic infection tends to occur earlier and is more severe. Early treatment with acyclovir is effective; intravenous treatment is not required unless local complications or systemic involvement are present. Long-term follow-up is recommended because of the possibility of recurrence.

Although the possibility of systemic involvement including hepatitis due to HSV infection is low, awareness among dermatologists about primary herpetic infection and its possible complications would be helpful in the diagnosis and treatment, especially for atypical or extensive cases.

To the Editor:

Cutaneous herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection generally involves mucocutaneous junctions, but virtually any area of the skin can be affected.1 When the genital area of adult patients is affected, the disease usually is sexually transmitted and mainly caused by HSV-2. In infants, genital primary herpetic infection is rare and more commonly is caused by HSV-1 than by HSV-2. We report a rare case of genital primary herpetic infection with concurrent hepatitis in an infant.

An 8-month-old infant with no underlying medical problems, including atopic dermatitis, was referred for erythematous grouped vesicles with erosions on the perianal area of 4 days’ duration (Figure). The skin color appeared normal, not icterus. She also had a fever (temperature, 37.9 °C), and her urination pattern had changed from normal to frequent leakage, possibly owing to pain related to the eroded lesions. Physical examination did not reveal palpable inguinal lymph nodes. The oral mucosa was not involved. The patient’s father had a history of recurrent herpetic infection on both the perioral and perianal areas.

A Tzanck smear revealed giant multinucleated cells with multiple inflammatory cells. Laboratory tests revealed marked leukocytosis, elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase, 141 IU/L [reference range, 15 IU/L–60 IU/L]; alanine aminotransferase, 422 IU/L [reference range, 13 IU/L–45 IU/L]), and was positive for herpes simplex viral IgM but negative for herpes simplex viral IgG. A viral culture also demonstrated the growth of HSV. An abdominal ultrasound was normal. Based on the cutaneous and laboratory findings, genital primary herpetic infection with concurrent hepatitis was diagnosed. Intravenous acyclovir 50 mg was administered 3 times daily for 7 days, and a wet dressing with topical mupirocin was employed daily until the skin lesions healed. The fever subsided soon after starting treatment. The liver enzyme counts decreased gradually in serial follow-up (aspartate aminotransferase, 75 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 70 IU/L).

Primary herpetic infection usually is asymptomatic, but when symptoms do occur, it is characterized by the sudden onset of painful vesicle clusters over erythematous edematous skin. Lesions can be associated with fever and malaise and may involve the perineum. Urinary symptoms may occur. The average age of onset ranges from 6 months to 4 years. The virus commonly is transmitted by asymptomatic carriers. Autoinoculation from concomitant oral primary herpetic infection or individuals with active herpetic infection is one possible route of transmission. In our patient, we assumed that she acquired the virus from her father during close contact. A diagnosis can be made clinically using direct methods including culture, Tzanck smear, or polymerase chain reaction, or indirect methods such as serologic tests.2

Hepatitis secondary to HSV infection is rare, especially in immunocompetent patients. It occurs during primary infection and rarely during recurrent infection with or without concomitant skin lesions.3 Symptoms include fever, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, leukopenia, coagulopathy, and marked elevation of serum transaminase levels without jaundice. Based on our patient’s elevated liver enzyme levels and virological evidence of acute primary HSV infection, a lack of evidence of other hepatic viral infections, and the presence of herpes simplex viremia, we concluded that this infant had viral hepatitis as a part of the clinical presentation of primary HSV infection. We did not perform a direct liver biopsy considering her age and accompanying risks.4

Primary herpetic infection usually has a benign course and a short duration. In children, the prognosis depends on underlying immunologic status, not a particular type of HSV. In children with atopic dermatitis, primary herpetic infection tends to occur earlier and is more severe. Early treatment with acyclovir is effective; intravenous treatment is not required unless local complications or systemic involvement are present. Long-term follow-up is recommended because of the possibility of recurrence.

Although the possibility of systemic involvement including hepatitis due to HSV infection is low, awareness among dermatologists about primary herpetic infection and its possible complications would be helpful in the diagnosis and treatment, especially for atypical or extensive cases.

- Jenson HB, Shapiro ED. Primary herpes simplex virus infection of a diaper rash. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:1136-1138.

- Batalla A, Flórez A, Dávila P, et al. Genital primary herpes simplexinfection in a 5-month-old infant. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:8.

- Norvell JP, Blei AT, Jovanovic BD, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: an analysis of the published literature and institutional cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1428-1434.

- Chen CK, Wu SH, Huang YC. Herpetic gingivostomatitis with severe hepatitis in a previously healthy child. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:324-325.

- Jenson HB, Shapiro ED. Primary herpes simplex virus infection of a diaper rash. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6:1136-1138.

- Batalla A, Flórez A, Dávila P, et al. Genital primary herpes simplexinfection in a 5-month-old infant. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:8.

- Norvell JP, Blei AT, Jovanovic BD, et al. Herpes simplex virus hepatitis: an analysis of the published literature and institutional cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:1428-1434.

- Chen CK, Wu SH, Huang YC. Herpetic gingivostomatitis with severe hepatitis in a previously healthy child. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:324-325.

Practice Points

- Parents with a history of herpes simplex virus (HSV) need to be educated before the baby is born to be careful about direct skin contact with the child to prevent the spread of HSV infection.

- Although systemic involvement is not typical, additional tests to rule out internal organ involvement may be required, especially in children.