User login

Isolated Scrotal Granular Parakeratosis: An Atypical Clinical Presentation

To the Editor:

Granular parakeratosis is a rare condition with an unclear etiology that results from a myriad of factors, including exposure to irritants, friction, moisture, and heat. The diagnosis is made based on a distinct histologic reaction pattern that may be protective against the triggers. We present a case of isolated scrotal granular parakeratosis in a patient with compensatory hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy.

A 52-year-old man presented with a 5-year history of a recurrent rash affecting the scrotum. He experienced monthly flares that were exacerbated by inguinal hyperhidrosis. His symptoms included a burning sensation and pruritus followed by superficial desquamation, with gradual yet temporary improvement. His medical history was remarkable for primary axillary and palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, with compensatory inguinal hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy 8 years prior to presentation.

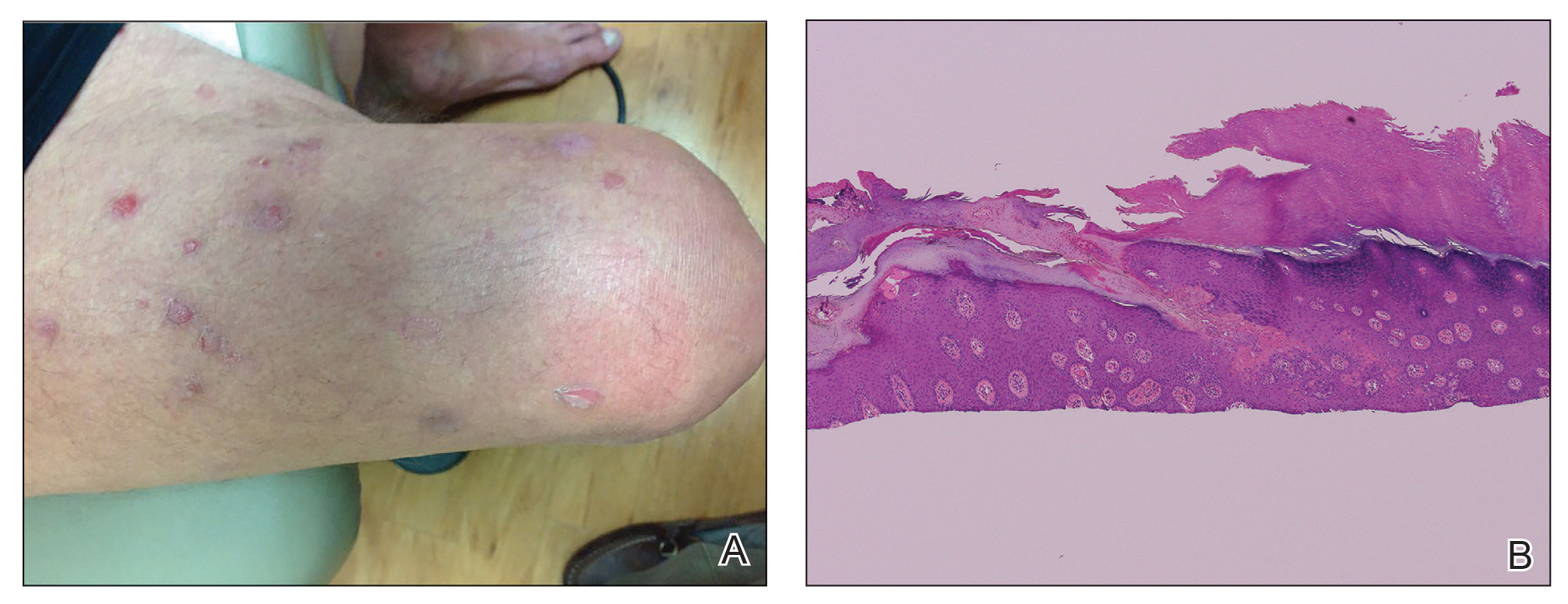

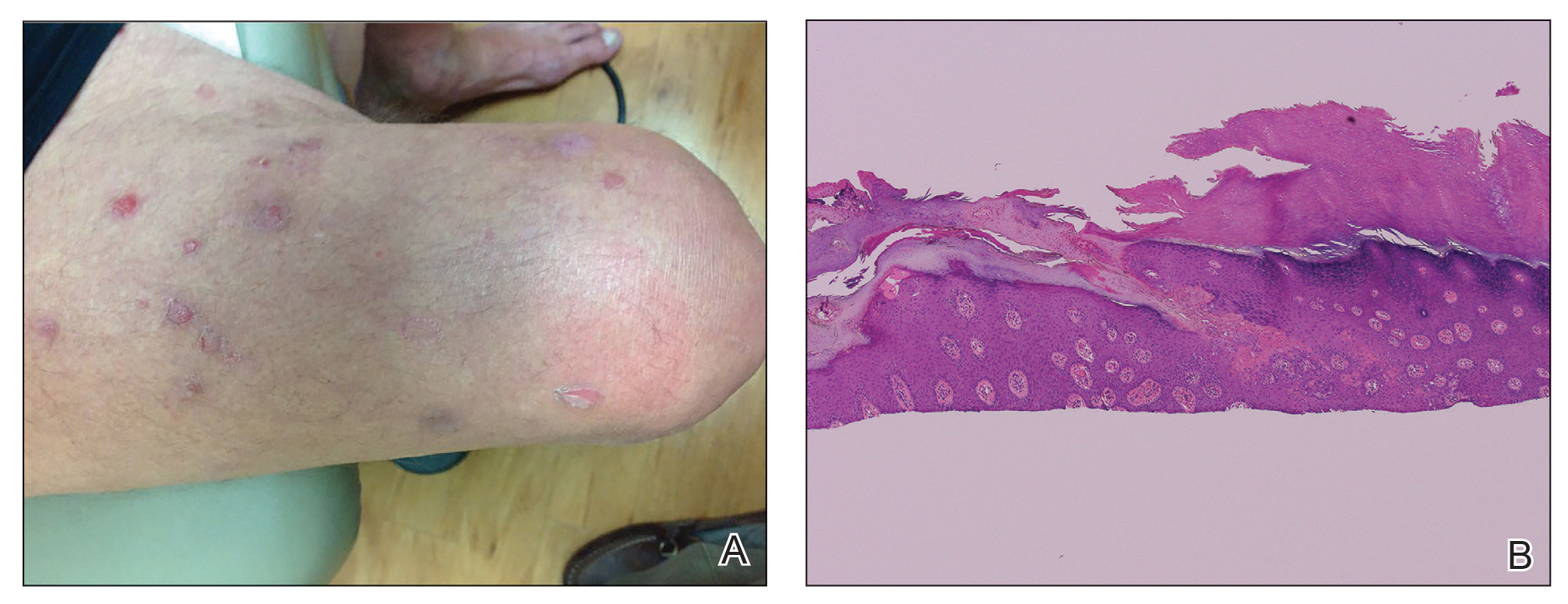

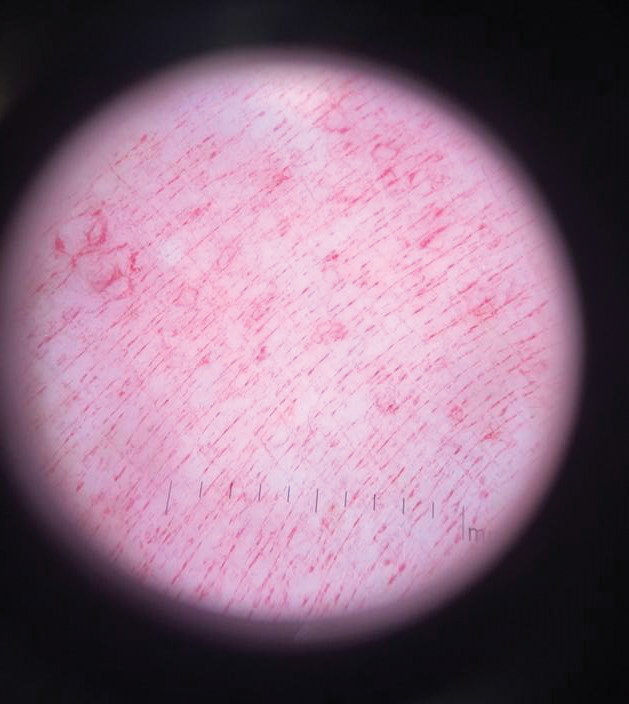

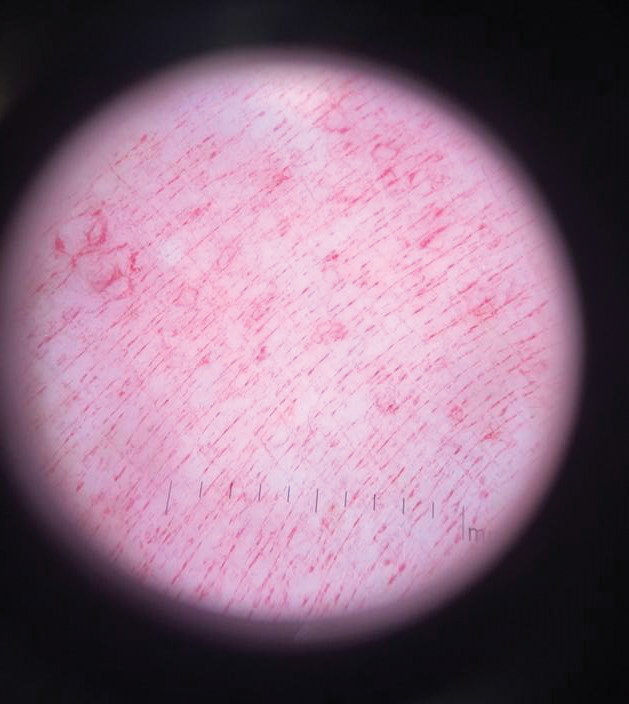

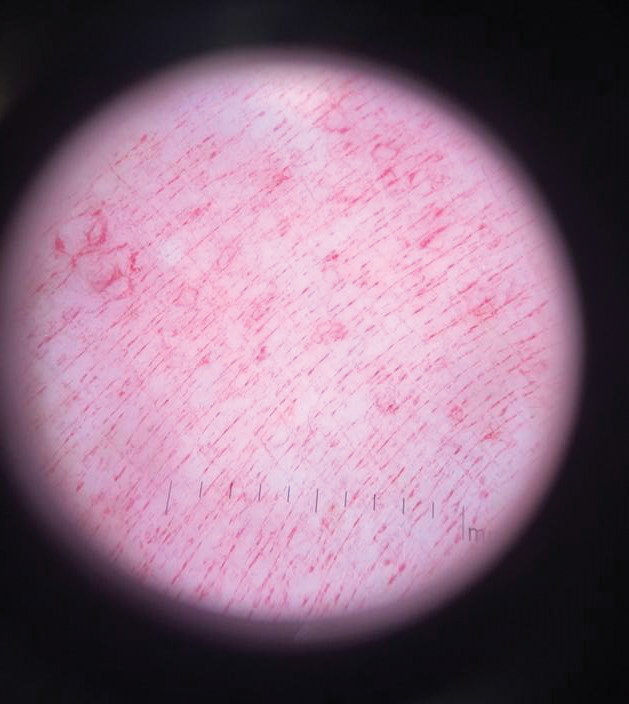

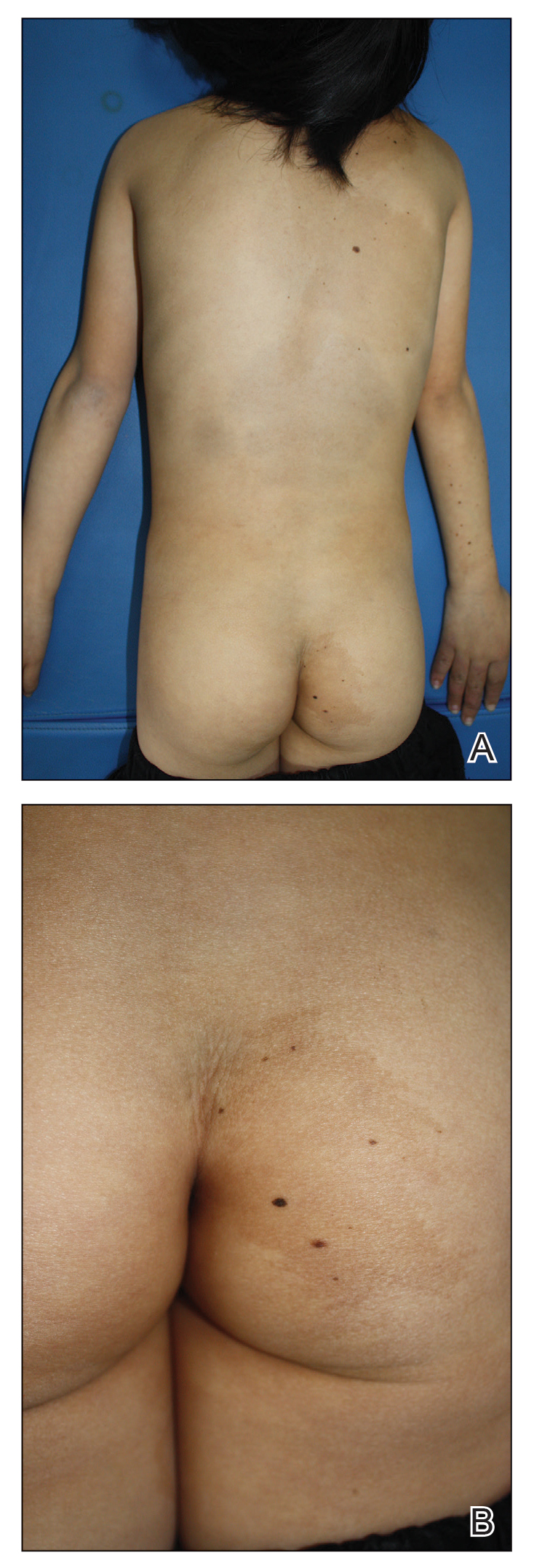

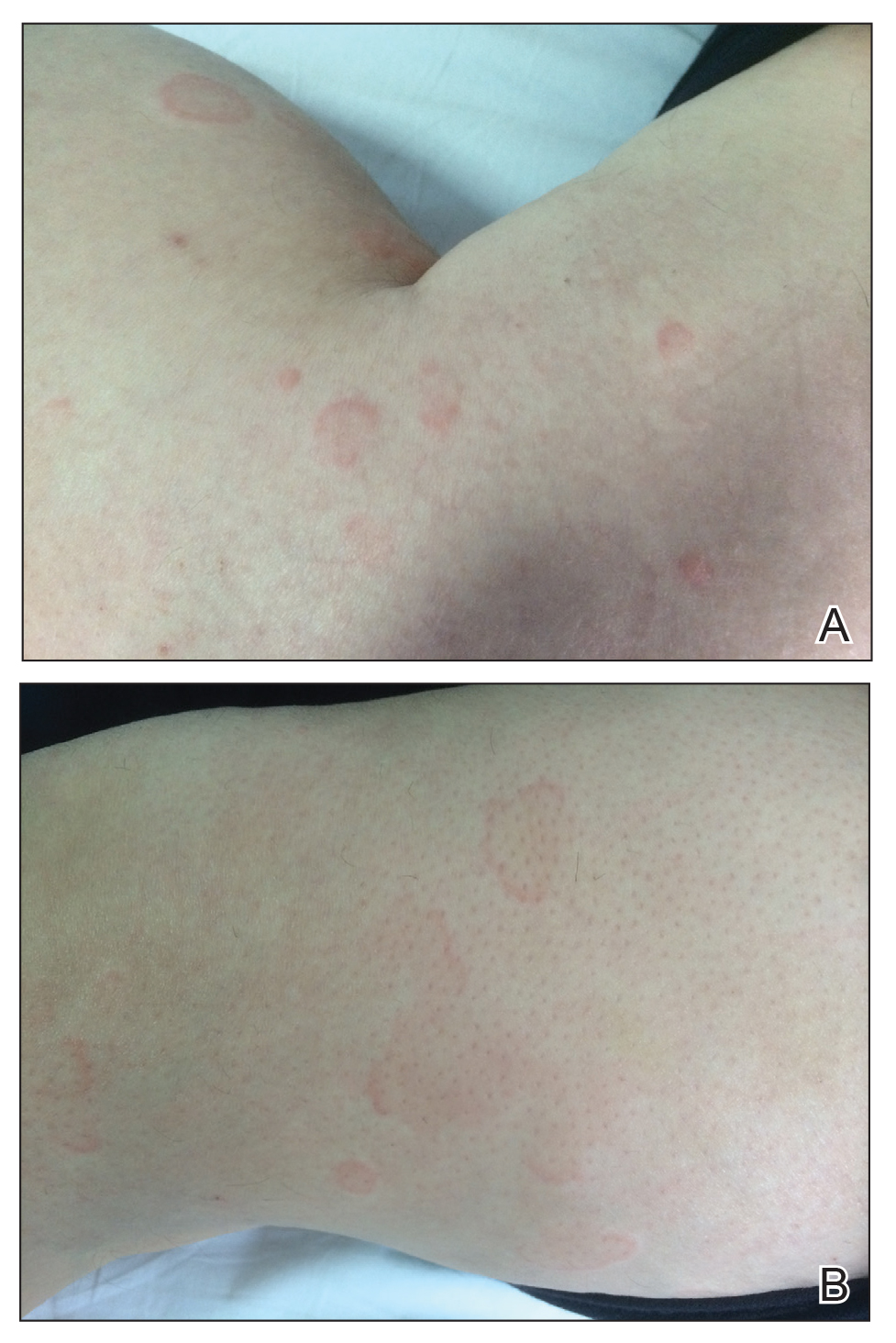

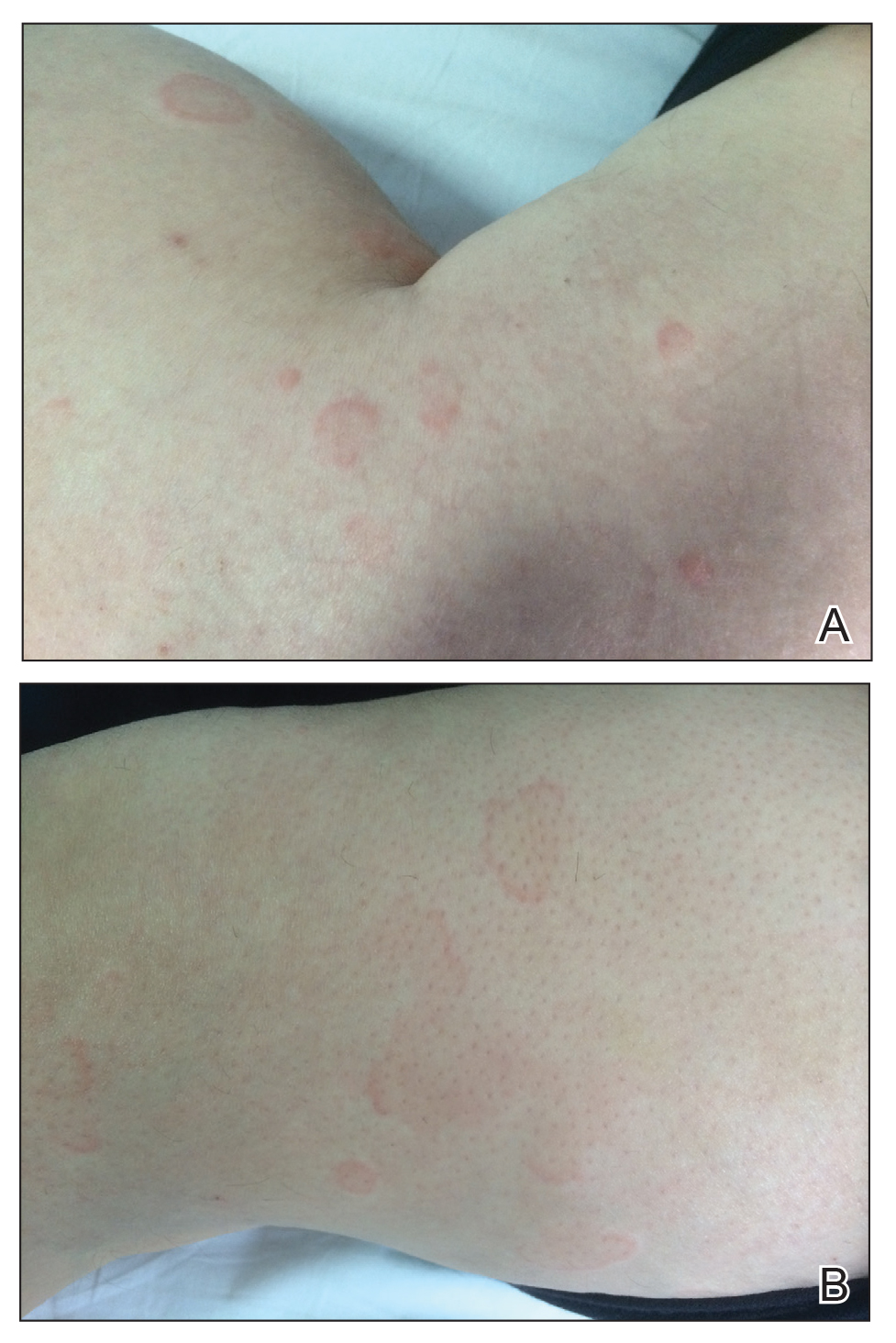

Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaque affecting the scrotal skin with sparing of the median raphe, penis, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). There were no other lesions noted in the axillary region or other skin folds.

Prior treatments prescribed by other providers included topical pimecrolimus, antifungal creams, topical corticosteroids, zinc oxide ointment, and daily application of an over-the-counter medicated powder with no resolution.

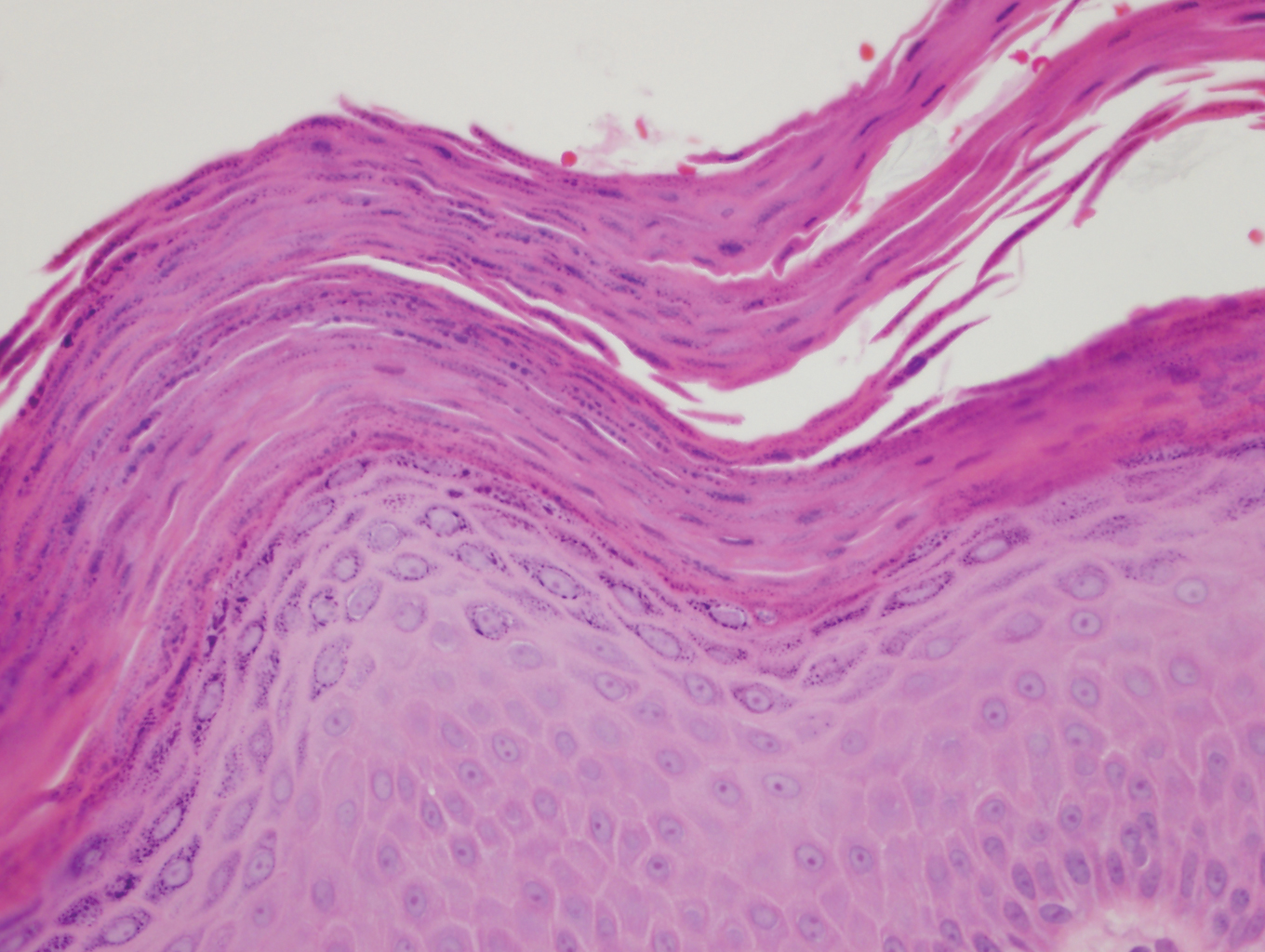

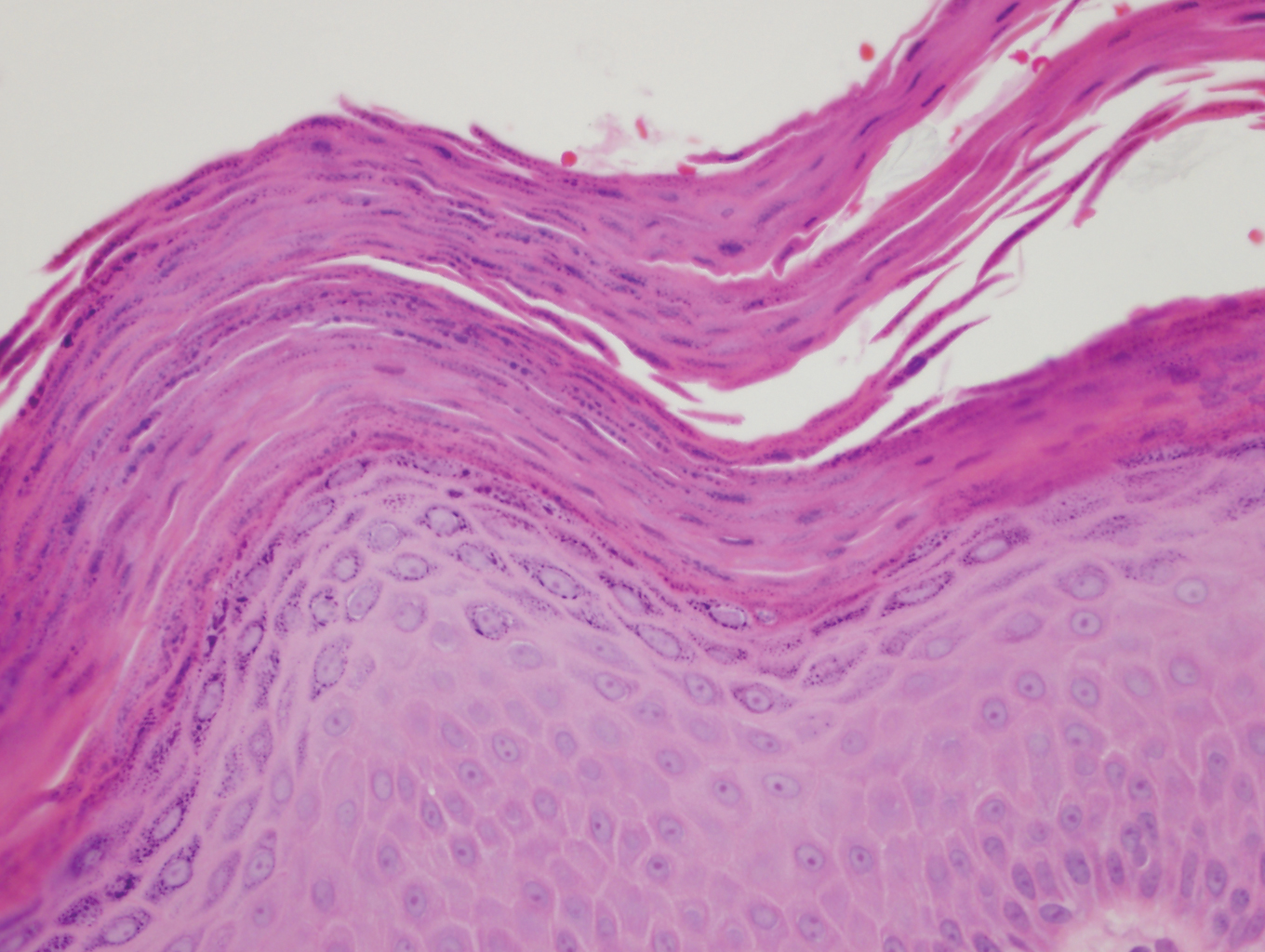

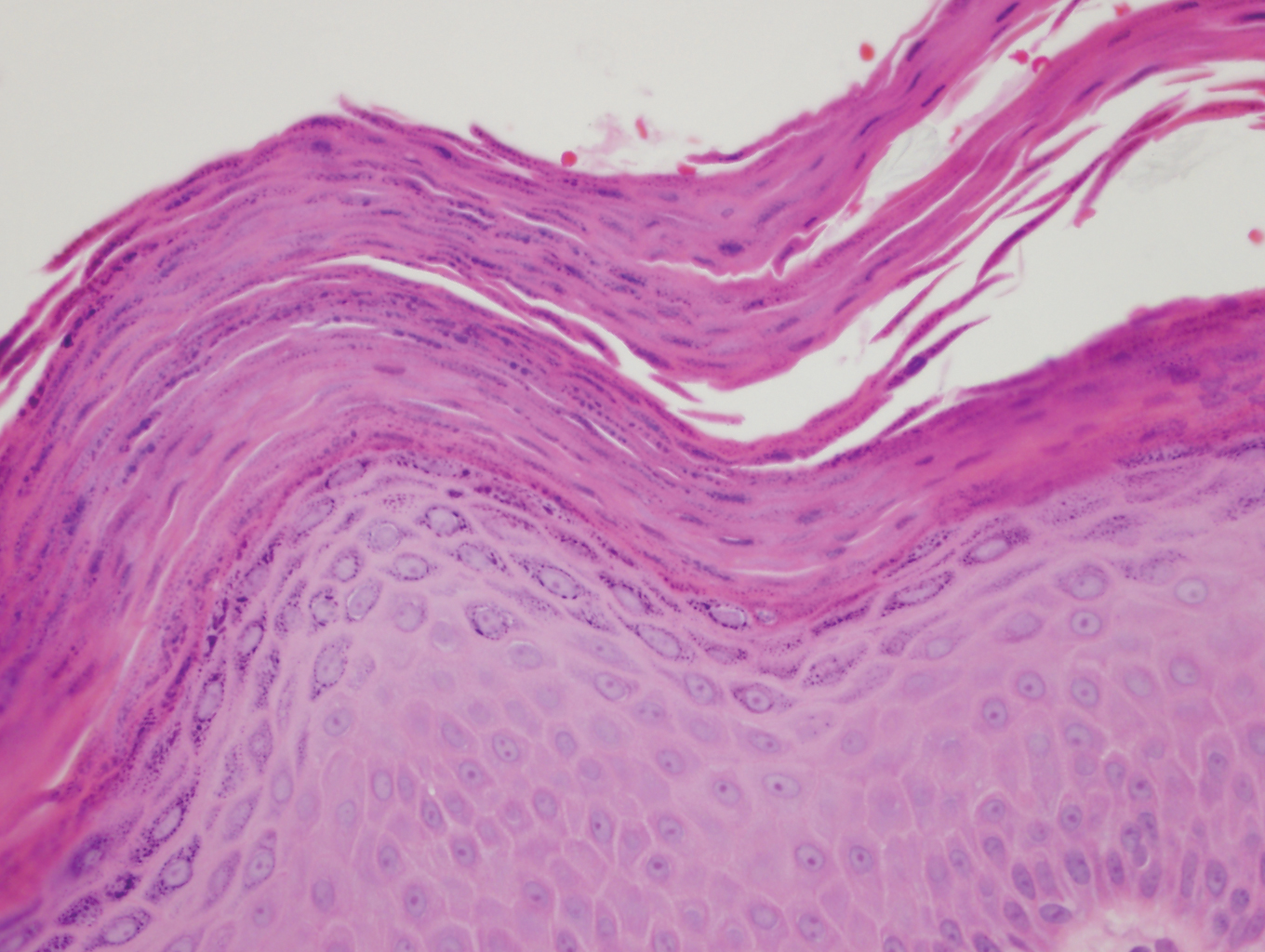

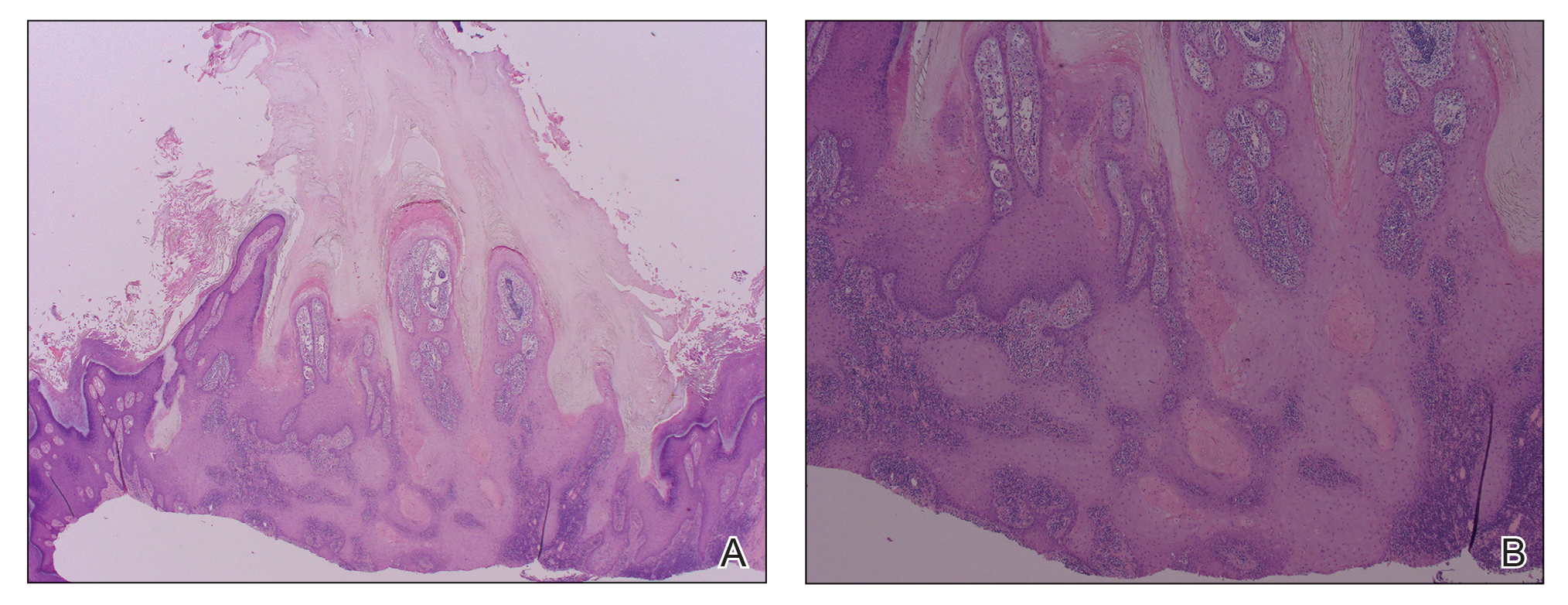

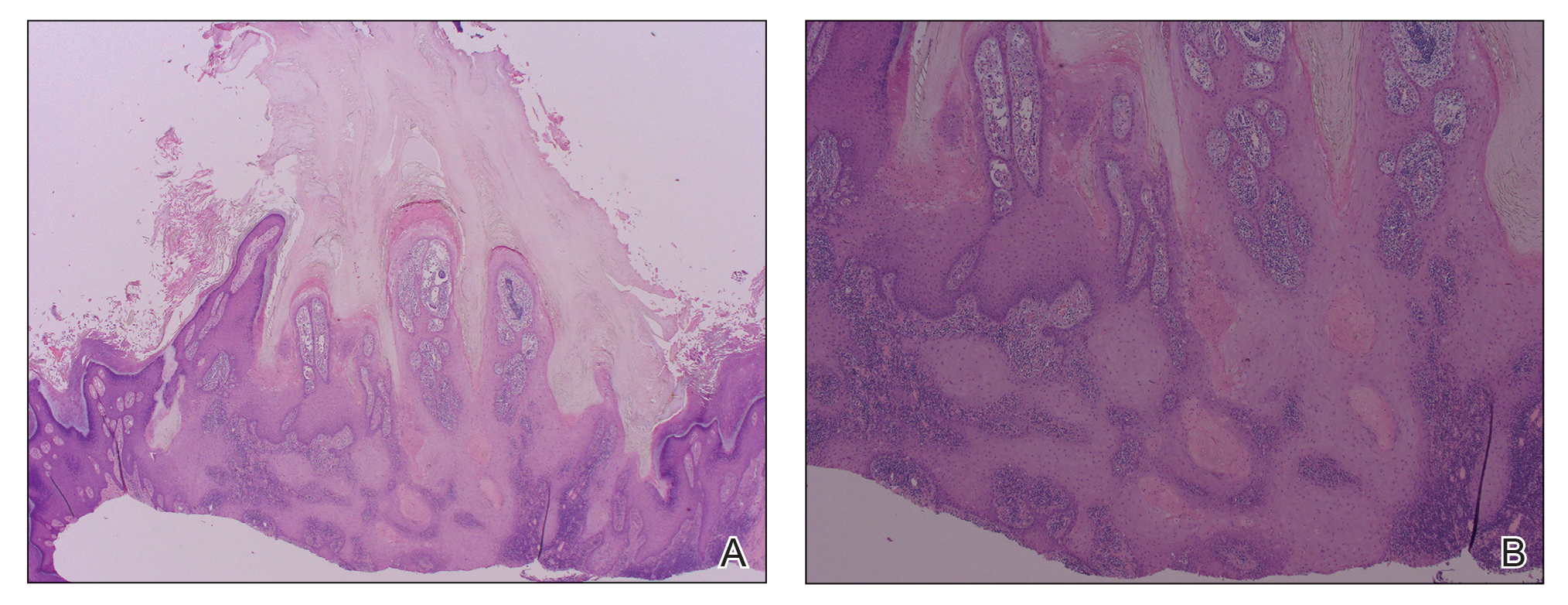

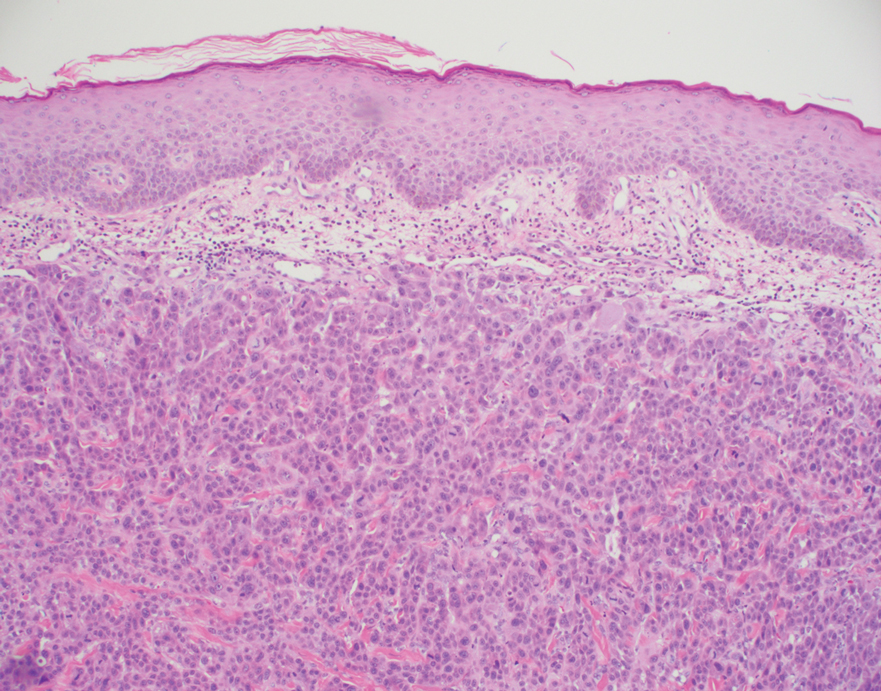

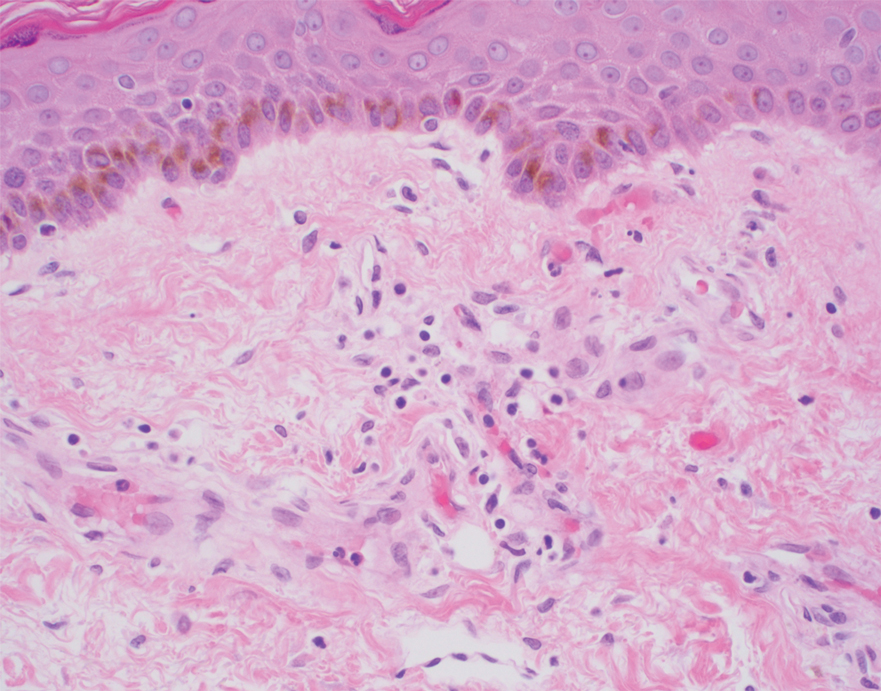

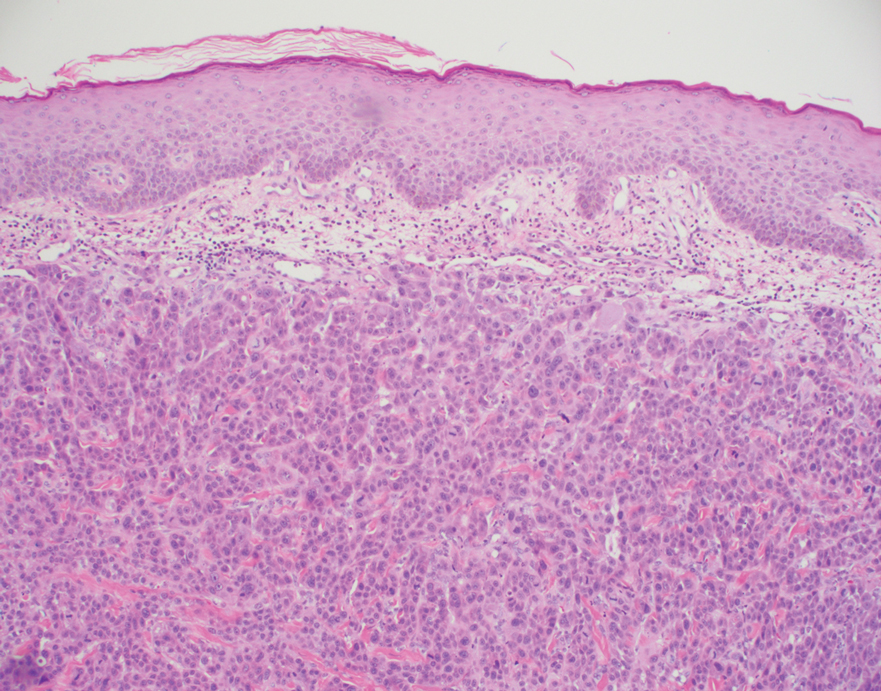

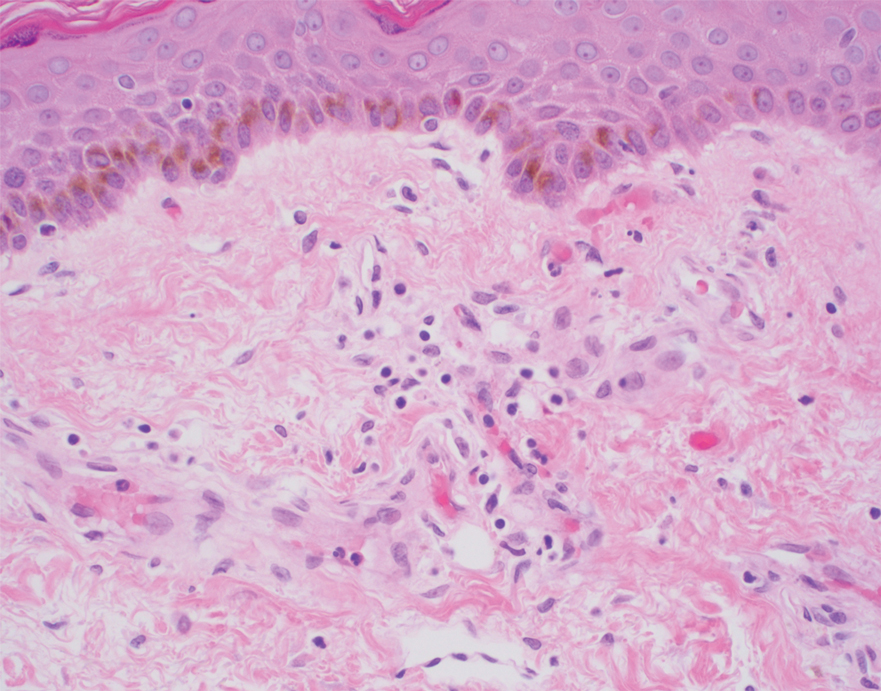

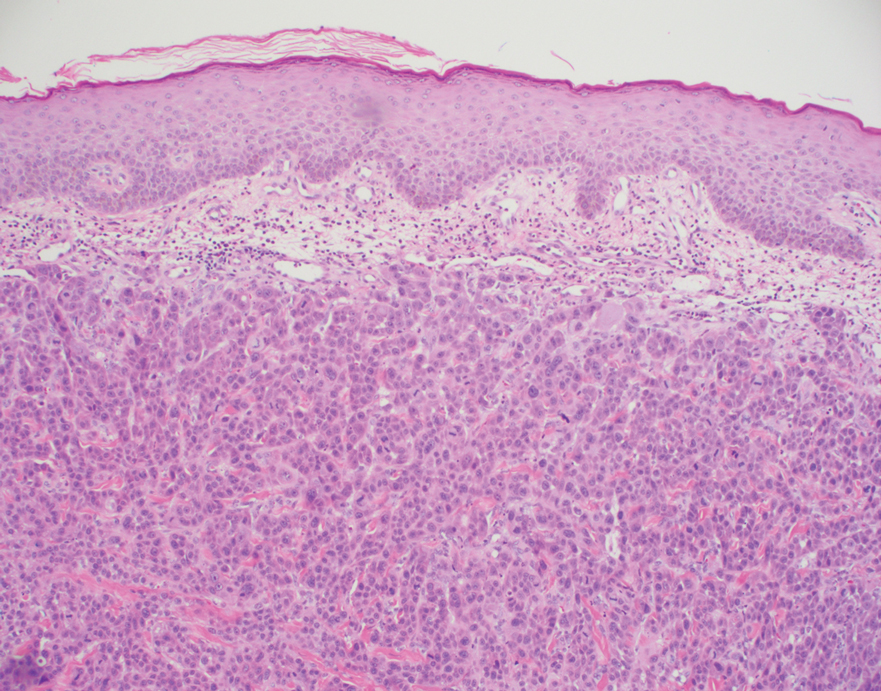

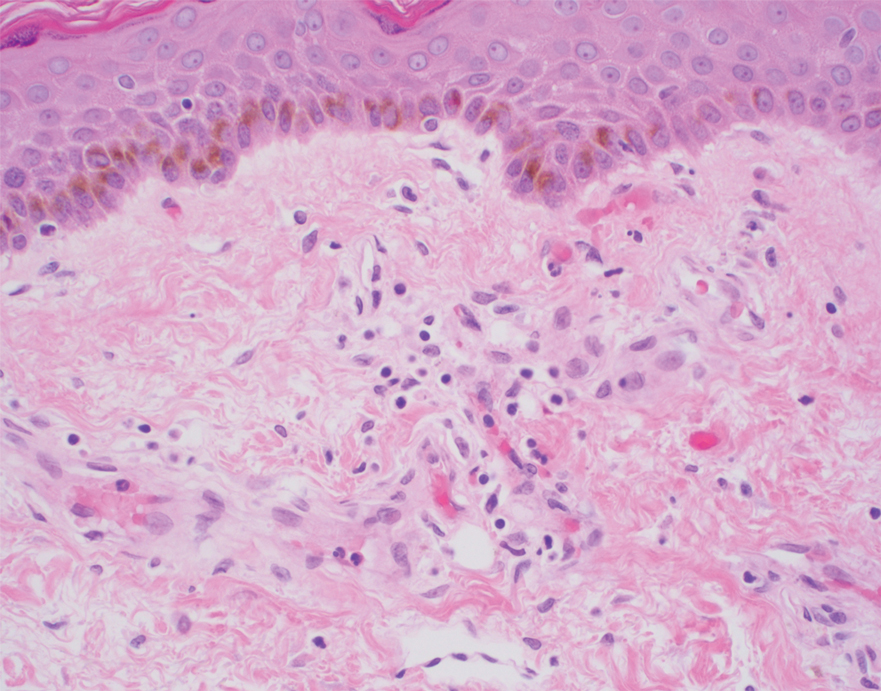

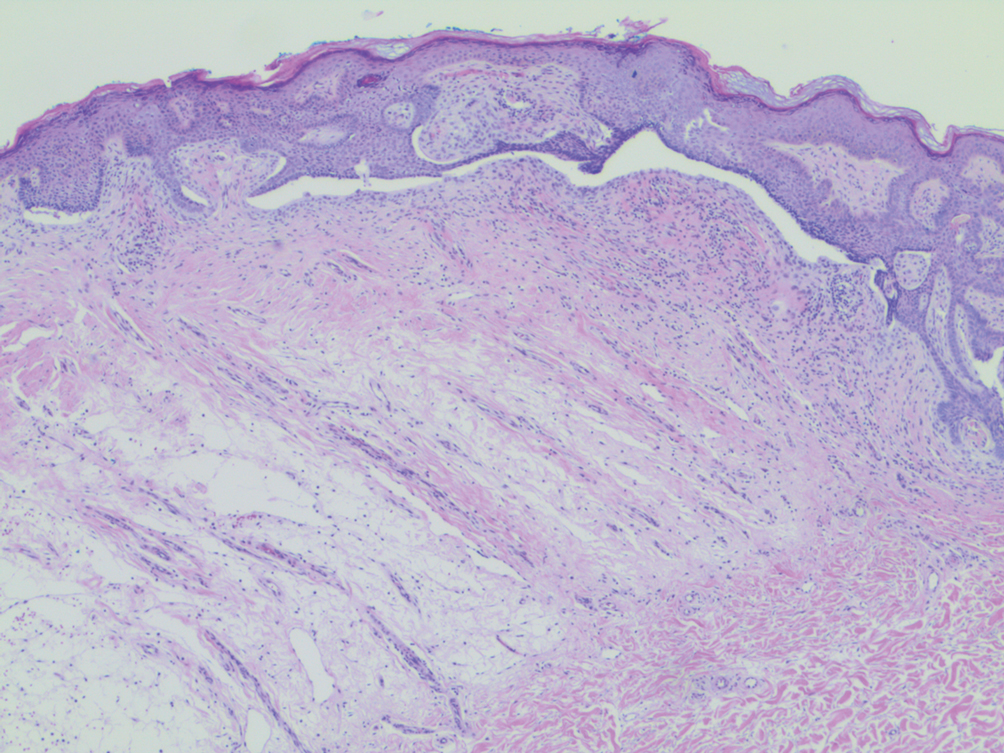

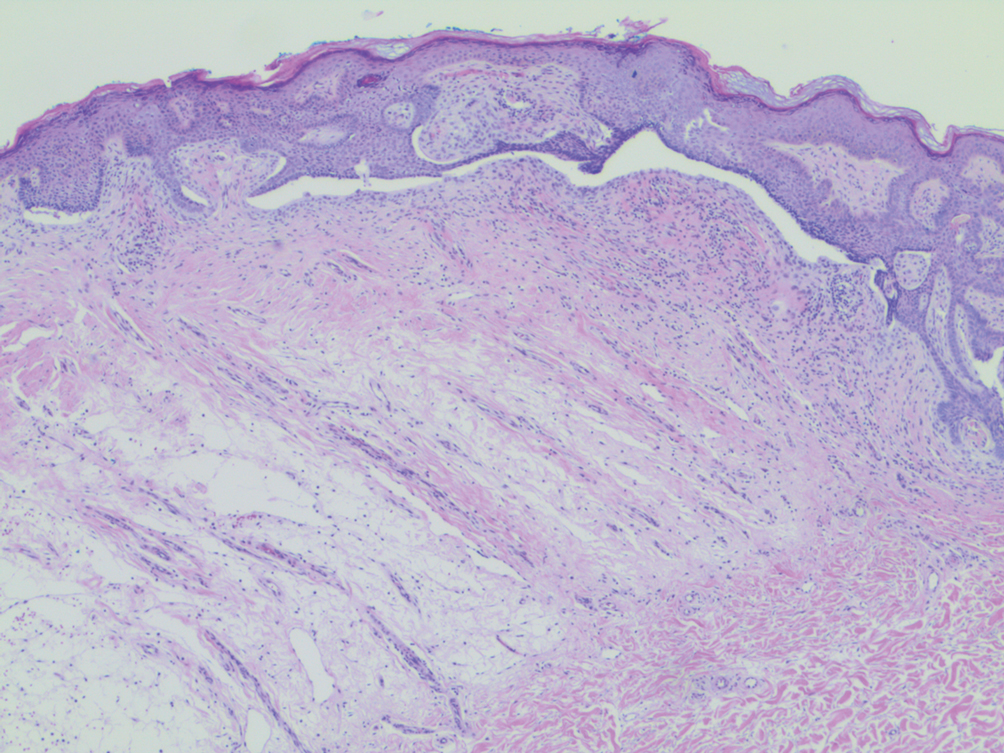

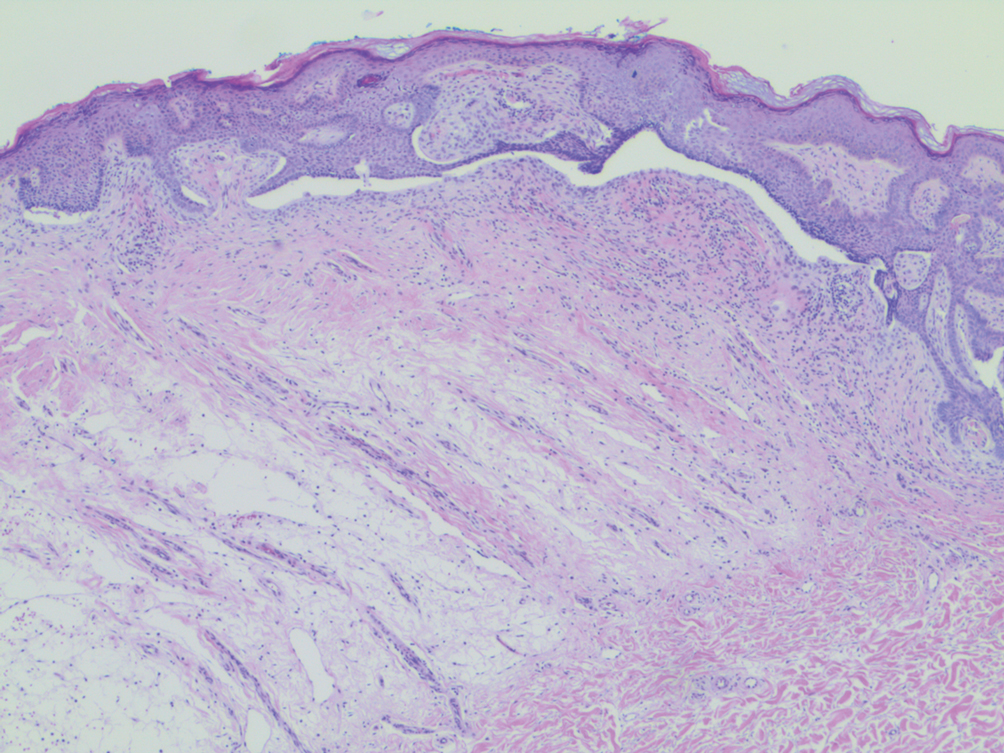

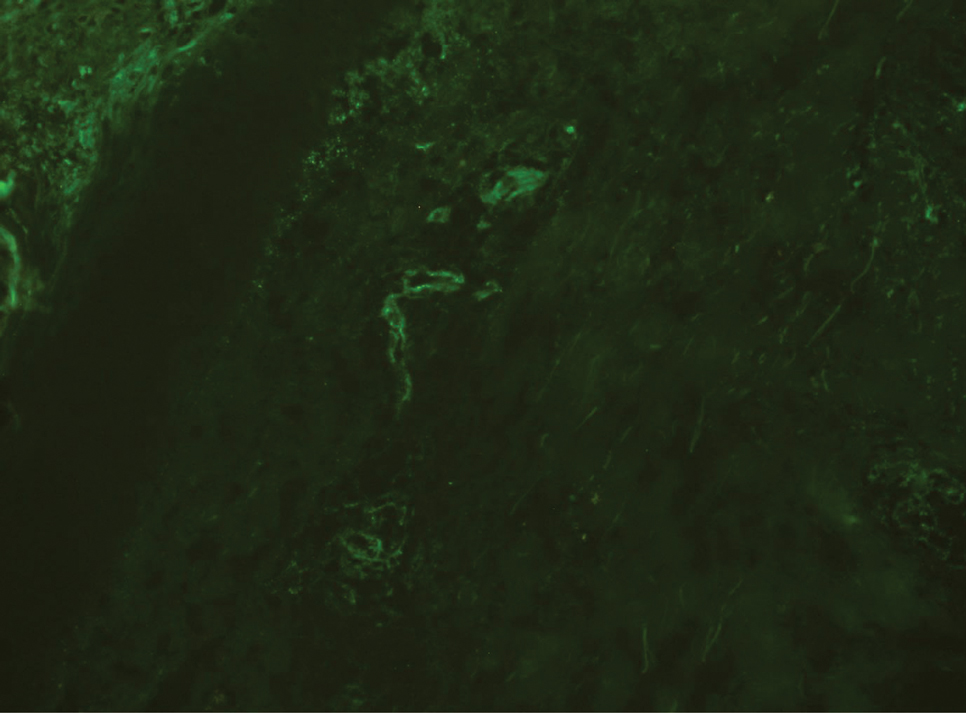

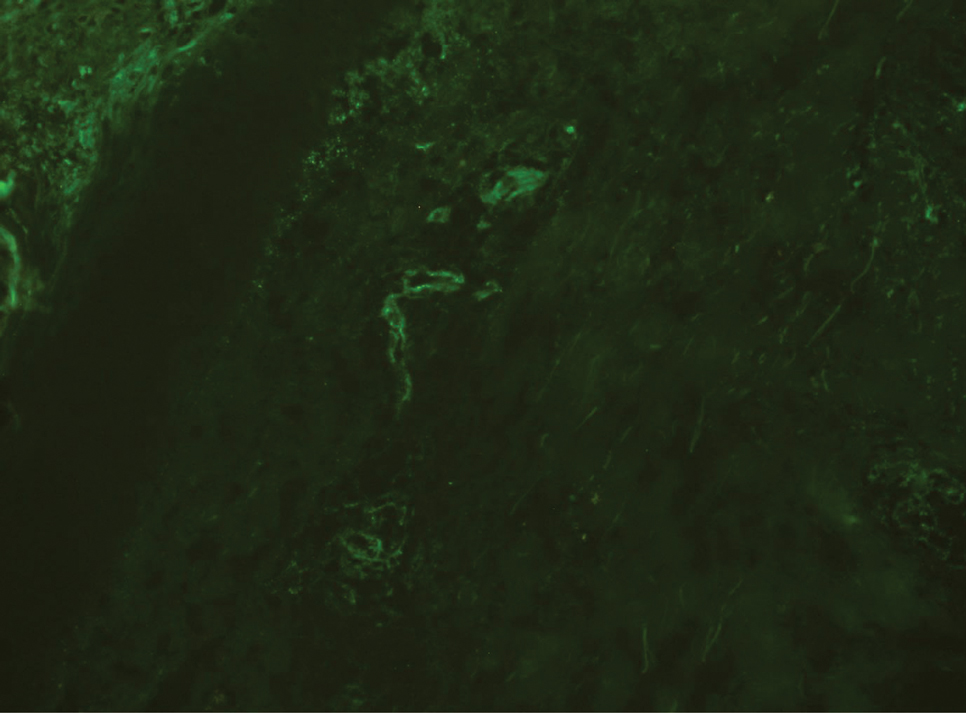

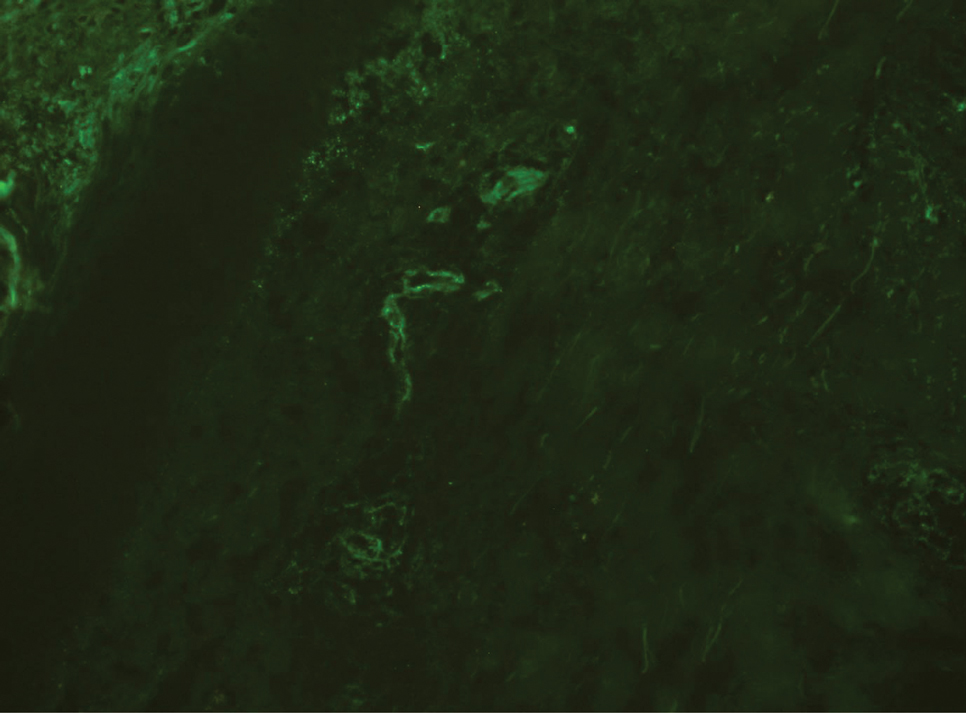

A punch biopsy performed at the current presentation showed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with only a focally diminished granular layer. There was overlying thick parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine- silver staining was negative for fungal elements in the sections examined. Clinical history, morphology of the eruption, and histologic features were consistent with granular parakeratosis.

Since the first reported incident of granular parakeratosis of the axilla in 1991,1 granular parakeratosis has been reported in other intertriginous areas, including the inframammary folds, inguinal folds, genitalia, perianal skin, and beneath the abdominal pannus.2 One case study in 1998 reported a patient with isolated involvement of the inguinal region3; however, this presentation is rare.4 This condition has been reported in both sexes and all age groups, including children.5

Granular parakeratosis classically presents as erythematous to brown hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into plaques.6 It is thought to be a reactive inflammatory condition secondary to aggravating factors such as exposure to heat,7 moisture, and friction; skin occlusion; repeated washing; irritation from external agents; antiperspirants; and use of depilatory creams.8 Histopathology is characteristic and consists of retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum, beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum. Epidermal changes may be varied and include atrophy or hyperplasia.

Murine models have postulated that granular parakeratosis may result from a deficiency in caspase 14, a protease vital to the formation of a well-functioning skin barrier.9 A cornified envelope often is noted in granular parakeratotic cells with no defects in desmosomes and cell membranes, suggesting that the pathogenesis lies within processing of profilaggrin to filaggrin, resulting in a failure to degrade keratohyalin granules and aggregation of keratin filaments.10 Granular parakeratosis is not known to be associated with other medical conditions, but it has been observed in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast11 and ovarian12 carcinomas. In infants with atopic dermatitis, granular parakeratosis was reported in 5 out of 7 cases.6 In our patient with secondary inguinal hyperhidrosis after thoracic sympathectomy, granular parakeratosis may be reactive to excess sweating and friction in the scrotal area.

Granular parakeratosis follows a waxing and waning pattern that may spontaneously resolve without any treatment; it also can follow a protracted course, as in a case with associated facial papules that persisted for 20 years.13 Topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with topical antifungal agents have been used for the treatment of granular parakeratosis with the goal of accelerating resolution.2,14 However, the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions is limited, and no controlled trials are underway. Topical vitamin D analogues15,16 and topical retinoids17 also have been reported with successful outcomes. Spontaneous resolution also has been observed in 2 different cases after previously being unresponsive to topical treatment.18,19 Treatment with Clostridium botulinum toxin A resulted in complete remission of the disease observed at 6-month follow-up. The pharmacologic action of the neurotoxin disrupts the stimulation of eccrine sweat glands, resulting in decreased sweating, a known exacerbating factor of granular parakeratosis.20

In summary, our case represents a unique clinical presentation of granular parakeratosis with classic histopathologic features. A high index of suspicion and a biopsy are vital to arriving at the correct diagnosis.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Mehregan DA, Thomas JE, Mehregan DR. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:495-496.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Prost-Squarcioni C, Hamel-Teillac D, et al. A case of congenital granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:531-533.

- Scheinfeld NS, Mones J. Granular parakeratosis: pathologic and clinical correlation of 18 cases of granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:863-867.

- Akkaya AD, Oram Y, Aydin O. Infantile granular parakeratosis: cytologic examination of superficial scrapings as an aid to diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:392-396.

- Rodríguez G. Axillary granular parakeratosis [in Spanish]. Biomedica. 2002;22:519-523.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Niedt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Hoste E, Denecker G, Gilbert B, et al. Caspase-14-deficient mice are more prone to the development of parakeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:742-750.

- Metze D, Rutten A. Granular parakeratosis—a unique acquired disorder of keratinization. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:339-352.

- Wallace CA, Pichardo RO, Yosipovitch G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:332-335.

- Jaconelli L, Doebelin B, Kanitakis J, et al. Granular parakeratosis in a patient treated with liposomal doxorubicin for ovarian carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5 suppl 1):S84-S87.

- Reddy IS, Swarnalata G, Mody T. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis persisting for 20 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:405-407.

- Dearden C, al-Nakib W, Andries K, et al. Drug resistant rhinoviruses from the nose of experimentally treated volunteers. Arch Virol. 1989;109:71-81.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB Jr. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Contreras ME, Gottfried LC, Bang RH, et al. Axillary intertriginous granular parakeratosis responsive to topical calcipotriene and ammonium lactate. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:382-383.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S279-S280.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:789-790.

- Ravitskiy L, Heymann WR. Botulinum toxin-induced resolution of axillary granular parakeratosis. Skinmed. 2005;4:118-120.

To the Editor:

Granular parakeratosis is a rare condition with an unclear etiology that results from a myriad of factors, including exposure to irritants, friction, moisture, and heat. The diagnosis is made based on a distinct histologic reaction pattern that may be protective against the triggers. We present a case of isolated scrotal granular parakeratosis in a patient with compensatory hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy.

A 52-year-old man presented with a 5-year history of a recurrent rash affecting the scrotum. He experienced monthly flares that were exacerbated by inguinal hyperhidrosis. His symptoms included a burning sensation and pruritus followed by superficial desquamation, with gradual yet temporary improvement. His medical history was remarkable for primary axillary and palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, with compensatory inguinal hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy 8 years prior to presentation.

Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaque affecting the scrotal skin with sparing of the median raphe, penis, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). There were no other lesions noted in the axillary region or other skin folds.

Prior treatments prescribed by other providers included topical pimecrolimus, antifungal creams, topical corticosteroids, zinc oxide ointment, and daily application of an over-the-counter medicated powder with no resolution.

A punch biopsy performed at the current presentation showed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with only a focally diminished granular layer. There was overlying thick parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine- silver staining was negative for fungal elements in the sections examined. Clinical history, morphology of the eruption, and histologic features were consistent with granular parakeratosis.

Since the first reported incident of granular parakeratosis of the axilla in 1991,1 granular parakeratosis has been reported in other intertriginous areas, including the inframammary folds, inguinal folds, genitalia, perianal skin, and beneath the abdominal pannus.2 One case study in 1998 reported a patient with isolated involvement of the inguinal region3; however, this presentation is rare.4 This condition has been reported in both sexes and all age groups, including children.5

Granular parakeratosis classically presents as erythematous to brown hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into plaques.6 It is thought to be a reactive inflammatory condition secondary to aggravating factors such as exposure to heat,7 moisture, and friction; skin occlusion; repeated washing; irritation from external agents; antiperspirants; and use of depilatory creams.8 Histopathology is characteristic and consists of retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum, beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum. Epidermal changes may be varied and include atrophy or hyperplasia.

Murine models have postulated that granular parakeratosis may result from a deficiency in caspase 14, a protease vital to the formation of a well-functioning skin barrier.9 A cornified envelope often is noted in granular parakeratotic cells with no defects in desmosomes and cell membranes, suggesting that the pathogenesis lies within processing of profilaggrin to filaggrin, resulting in a failure to degrade keratohyalin granules and aggregation of keratin filaments.10 Granular parakeratosis is not known to be associated with other medical conditions, but it has been observed in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast11 and ovarian12 carcinomas. In infants with atopic dermatitis, granular parakeratosis was reported in 5 out of 7 cases.6 In our patient with secondary inguinal hyperhidrosis after thoracic sympathectomy, granular parakeratosis may be reactive to excess sweating and friction in the scrotal area.

Granular parakeratosis follows a waxing and waning pattern that may spontaneously resolve without any treatment; it also can follow a protracted course, as in a case with associated facial papules that persisted for 20 years.13 Topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with topical antifungal agents have been used for the treatment of granular parakeratosis with the goal of accelerating resolution.2,14 However, the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions is limited, and no controlled trials are underway. Topical vitamin D analogues15,16 and topical retinoids17 also have been reported with successful outcomes. Spontaneous resolution also has been observed in 2 different cases after previously being unresponsive to topical treatment.18,19 Treatment with Clostridium botulinum toxin A resulted in complete remission of the disease observed at 6-month follow-up. The pharmacologic action of the neurotoxin disrupts the stimulation of eccrine sweat glands, resulting in decreased sweating, a known exacerbating factor of granular parakeratosis.20

In summary, our case represents a unique clinical presentation of granular parakeratosis with classic histopathologic features. A high index of suspicion and a biopsy are vital to arriving at the correct diagnosis.

To the Editor:

Granular parakeratosis is a rare condition with an unclear etiology that results from a myriad of factors, including exposure to irritants, friction, moisture, and heat. The diagnosis is made based on a distinct histologic reaction pattern that may be protective against the triggers. We present a case of isolated scrotal granular parakeratosis in a patient with compensatory hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy.

A 52-year-old man presented with a 5-year history of a recurrent rash affecting the scrotum. He experienced monthly flares that were exacerbated by inguinal hyperhidrosis. His symptoms included a burning sensation and pruritus followed by superficial desquamation, with gradual yet temporary improvement. His medical history was remarkable for primary axillary and palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, with compensatory inguinal hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy 8 years prior to presentation.

Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaque affecting the scrotal skin with sparing of the median raphe, penis, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). There were no other lesions noted in the axillary region or other skin folds.

Prior treatments prescribed by other providers included topical pimecrolimus, antifungal creams, topical corticosteroids, zinc oxide ointment, and daily application of an over-the-counter medicated powder with no resolution.

A punch biopsy performed at the current presentation showed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with only a focally diminished granular layer. There was overlying thick parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine- silver staining was negative for fungal elements in the sections examined. Clinical history, morphology of the eruption, and histologic features were consistent with granular parakeratosis.

Since the first reported incident of granular parakeratosis of the axilla in 1991,1 granular parakeratosis has been reported in other intertriginous areas, including the inframammary folds, inguinal folds, genitalia, perianal skin, and beneath the abdominal pannus.2 One case study in 1998 reported a patient with isolated involvement of the inguinal region3; however, this presentation is rare.4 This condition has been reported in both sexes and all age groups, including children.5

Granular parakeratosis classically presents as erythematous to brown hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into plaques.6 It is thought to be a reactive inflammatory condition secondary to aggravating factors such as exposure to heat,7 moisture, and friction; skin occlusion; repeated washing; irritation from external agents; antiperspirants; and use of depilatory creams.8 Histopathology is characteristic and consists of retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum, beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum. Epidermal changes may be varied and include atrophy or hyperplasia.

Murine models have postulated that granular parakeratosis may result from a deficiency in caspase 14, a protease vital to the formation of a well-functioning skin barrier.9 A cornified envelope often is noted in granular parakeratotic cells with no defects in desmosomes and cell membranes, suggesting that the pathogenesis lies within processing of profilaggrin to filaggrin, resulting in a failure to degrade keratohyalin granules and aggregation of keratin filaments.10 Granular parakeratosis is not known to be associated with other medical conditions, but it has been observed in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast11 and ovarian12 carcinomas. In infants with atopic dermatitis, granular parakeratosis was reported in 5 out of 7 cases.6 In our patient with secondary inguinal hyperhidrosis after thoracic sympathectomy, granular parakeratosis may be reactive to excess sweating and friction in the scrotal area.

Granular parakeratosis follows a waxing and waning pattern that may spontaneously resolve without any treatment; it also can follow a protracted course, as in a case with associated facial papules that persisted for 20 years.13 Topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with topical antifungal agents have been used for the treatment of granular parakeratosis with the goal of accelerating resolution.2,14 However, the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions is limited, and no controlled trials are underway. Topical vitamin D analogues15,16 and topical retinoids17 also have been reported with successful outcomes. Spontaneous resolution also has been observed in 2 different cases after previously being unresponsive to topical treatment.18,19 Treatment with Clostridium botulinum toxin A resulted in complete remission of the disease observed at 6-month follow-up. The pharmacologic action of the neurotoxin disrupts the stimulation of eccrine sweat glands, resulting in decreased sweating, a known exacerbating factor of granular parakeratosis.20

In summary, our case represents a unique clinical presentation of granular parakeratosis with classic histopathologic features. A high index of suspicion and a biopsy are vital to arriving at the correct diagnosis.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Mehregan DA, Thomas JE, Mehregan DR. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:495-496.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Prost-Squarcioni C, Hamel-Teillac D, et al. A case of congenital granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:531-533.

- Scheinfeld NS, Mones J. Granular parakeratosis: pathologic and clinical correlation of 18 cases of granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:863-867.

- Akkaya AD, Oram Y, Aydin O. Infantile granular parakeratosis: cytologic examination of superficial scrapings as an aid to diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:392-396.

- Rodríguez G. Axillary granular parakeratosis [in Spanish]. Biomedica. 2002;22:519-523.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Niedt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Hoste E, Denecker G, Gilbert B, et al. Caspase-14-deficient mice are more prone to the development of parakeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:742-750.

- Metze D, Rutten A. Granular parakeratosis—a unique acquired disorder of keratinization. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:339-352.

- Wallace CA, Pichardo RO, Yosipovitch G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:332-335.

- Jaconelli L, Doebelin B, Kanitakis J, et al. Granular parakeratosis in a patient treated with liposomal doxorubicin for ovarian carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5 suppl 1):S84-S87.

- Reddy IS, Swarnalata G, Mody T. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis persisting for 20 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:405-407.

- Dearden C, al-Nakib W, Andries K, et al. Drug resistant rhinoviruses from the nose of experimentally treated volunteers. Arch Virol. 1989;109:71-81.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB Jr. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Contreras ME, Gottfried LC, Bang RH, et al. Axillary intertriginous granular parakeratosis responsive to topical calcipotriene and ammonium lactate. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:382-383.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S279-S280.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:789-790.

- Ravitskiy L, Heymann WR. Botulinum toxin-induced resolution of axillary granular parakeratosis. Skinmed. 2005;4:118-120.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Mehregan DA, Thomas JE, Mehregan DR. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:495-496.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Prost-Squarcioni C, Hamel-Teillac D, et al. A case of congenital granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:531-533.

- Scheinfeld NS, Mones J. Granular parakeratosis: pathologic and clinical correlation of 18 cases of granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:863-867.

- Akkaya AD, Oram Y, Aydin O. Infantile granular parakeratosis: cytologic examination of superficial scrapings as an aid to diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:392-396.

- Rodríguez G. Axillary granular parakeratosis [in Spanish]. Biomedica. 2002;22:519-523.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Niedt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Hoste E, Denecker G, Gilbert B, et al. Caspase-14-deficient mice are more prone to the development of parakeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:742-750.

- Metze D, Rutten A. Granular parakeratosis—a unique acquired disorder of keratinization. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:339-352.

- Wallace CA, Pichardo RO, Yosipovitch G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:332-335.

- Jaconelli L, Doebelin B, Kanitakis J, et al. Granular parakeratosis in a patient treated with liposomal doxorubicin for ovarian carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5 suppl 1):S84-S87.

- Reddy IS, Swarnalata G, Mody T. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis persisting for 20 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:405-407.

- Dearden C, al-Nakib W, Andries K, et al. Drug resistant rhinoviruses from the nose of experimentally treated volunteers. Arch Virol. 1989;109:71-81.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB Jr. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Contreras ME, Gottfried LC, Bang RH, et al. Axillary intertriginous granular parakeratosis responsive to topical calcipotriene and ammonium lactate. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:382-383.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S279-S280.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:789-790.

- Ravitskiy L, Heymann WR. Botulinum toxin-induced resolution of axillary granular parakeratosis. Skinmed. 2005;4:118-120.

Practice Points

- Granular parakeratosis can occur in response to triggers such as irritants, friction, hyperhidrosis, and heat.

- Granular parakeratosis can have an atypical presentation; therefore, a high index of suspicion and punch biopsy are vital to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

- Classic histopathology demonstrates retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum.

Fulminant Hemorrhagic Bullae of the Upper Extremities Arising in the Setting of IV Placement During Severe COVID-19 Infection: Observations From a Major Consultative Practice

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

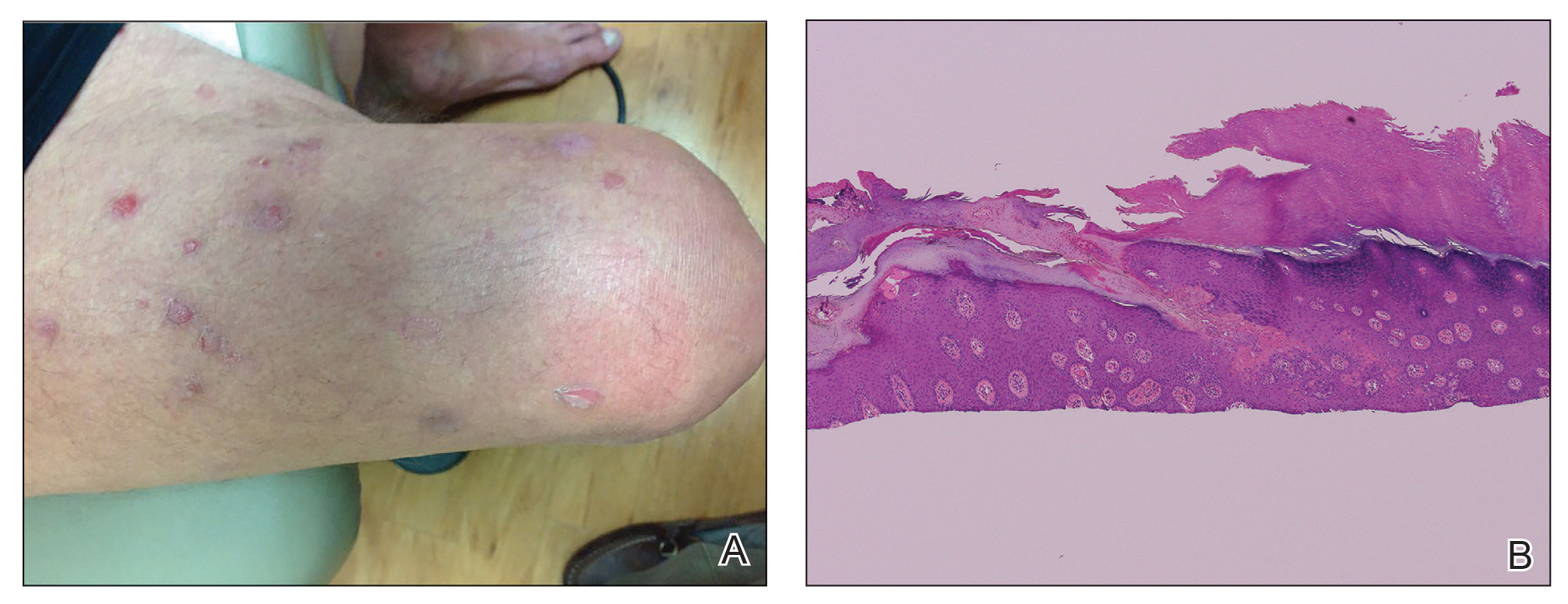

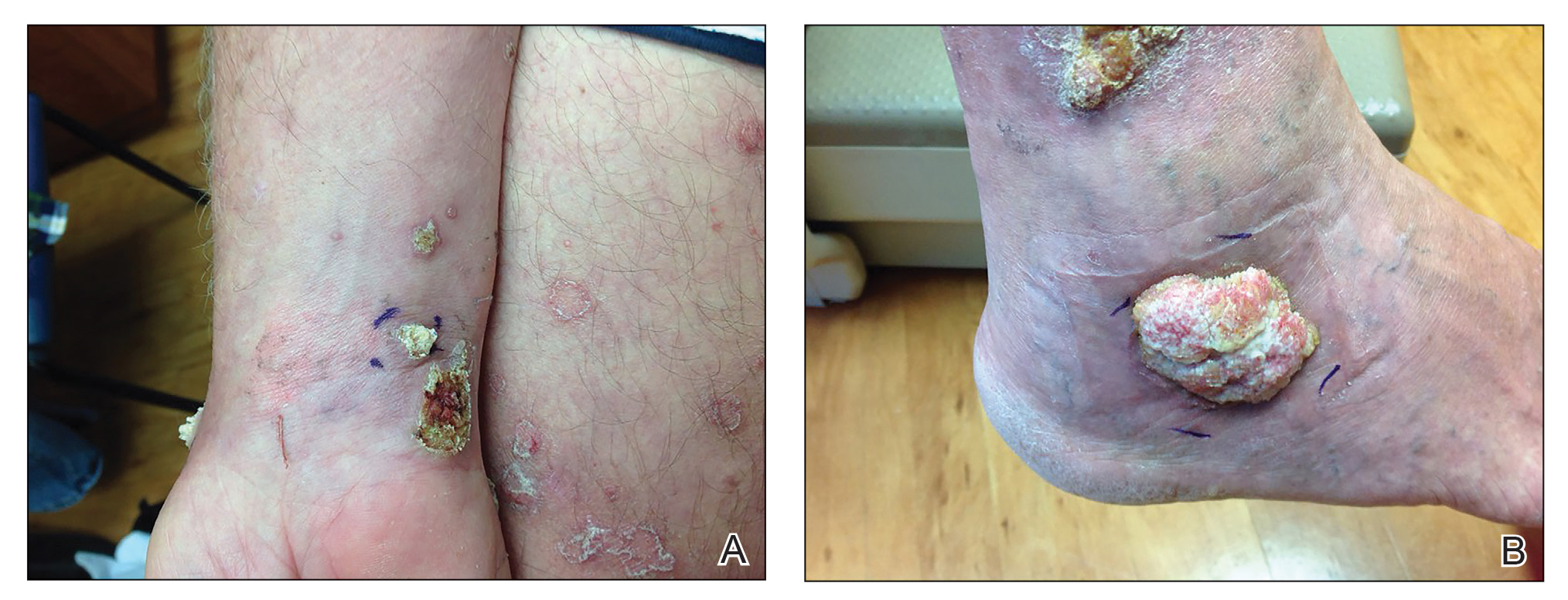

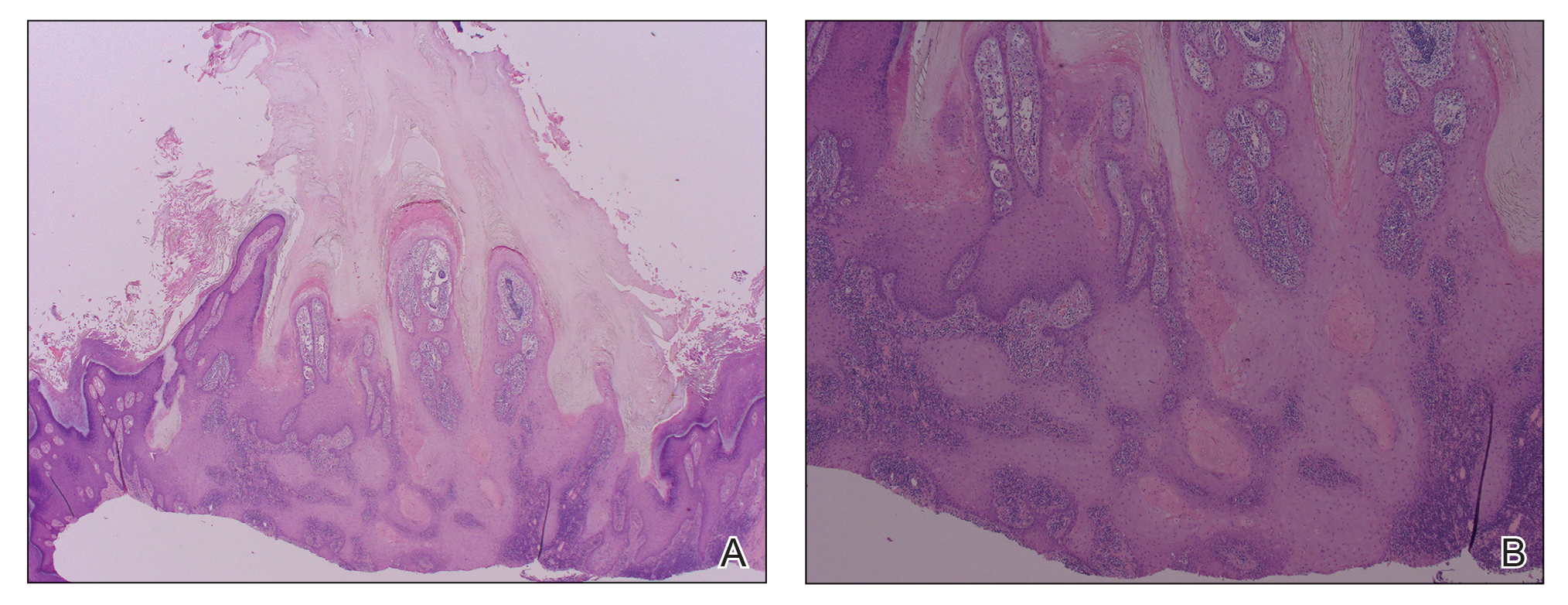

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

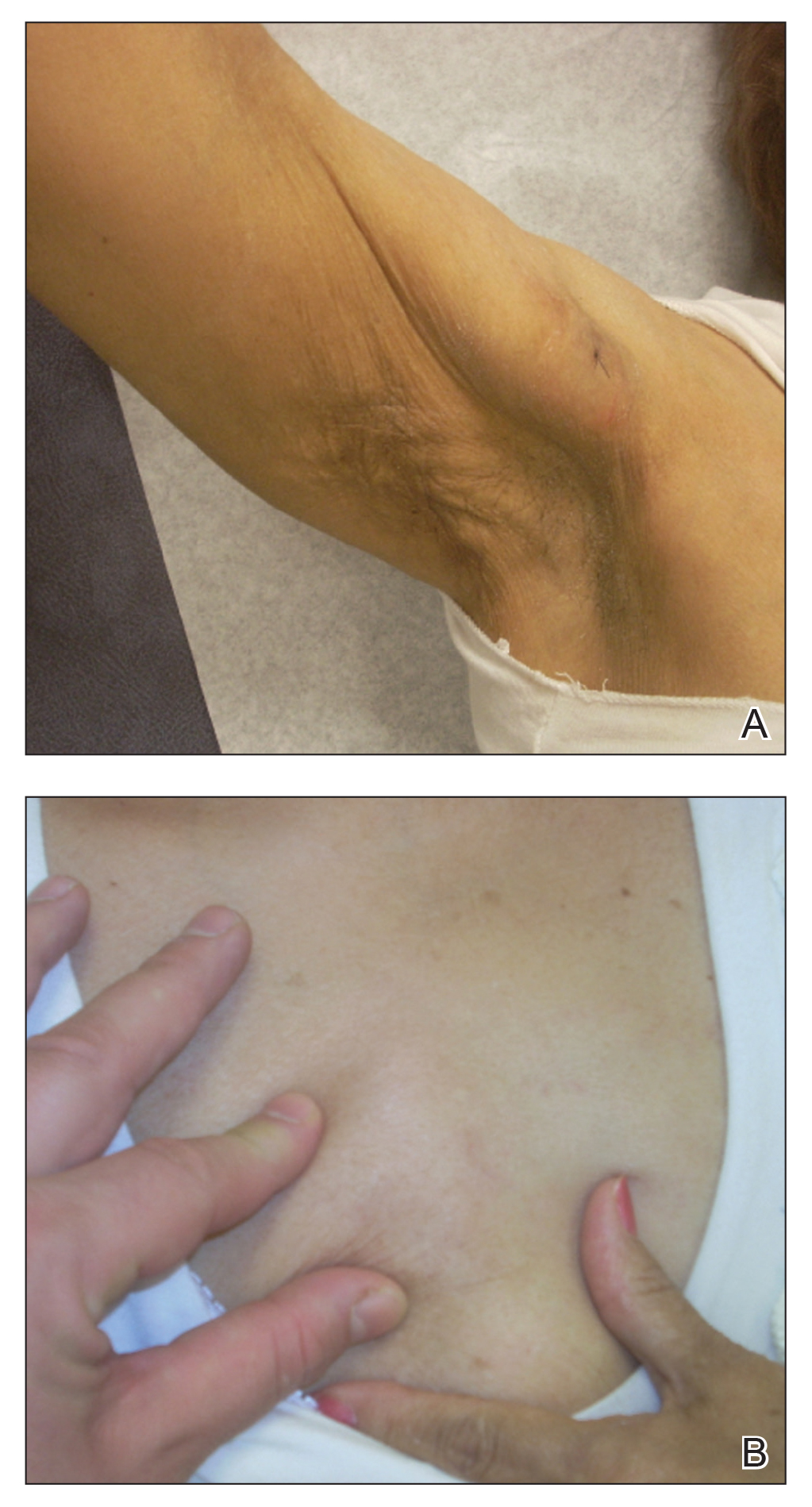

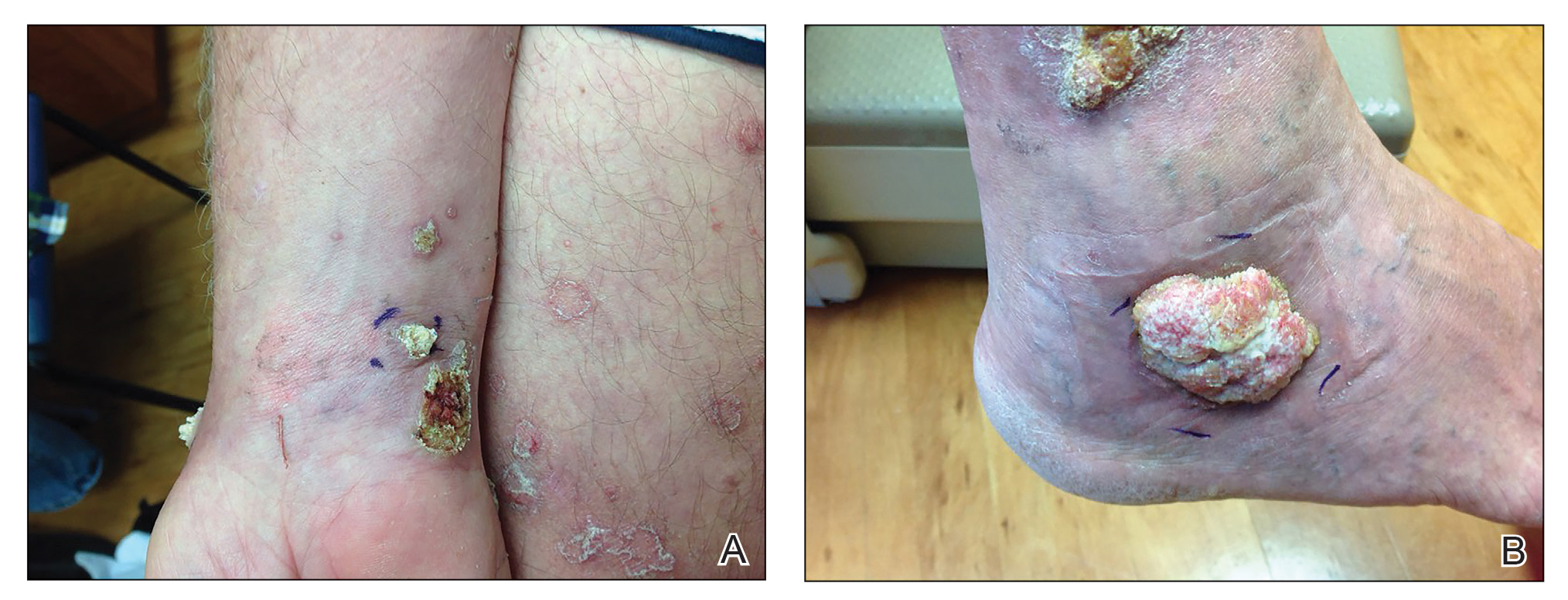

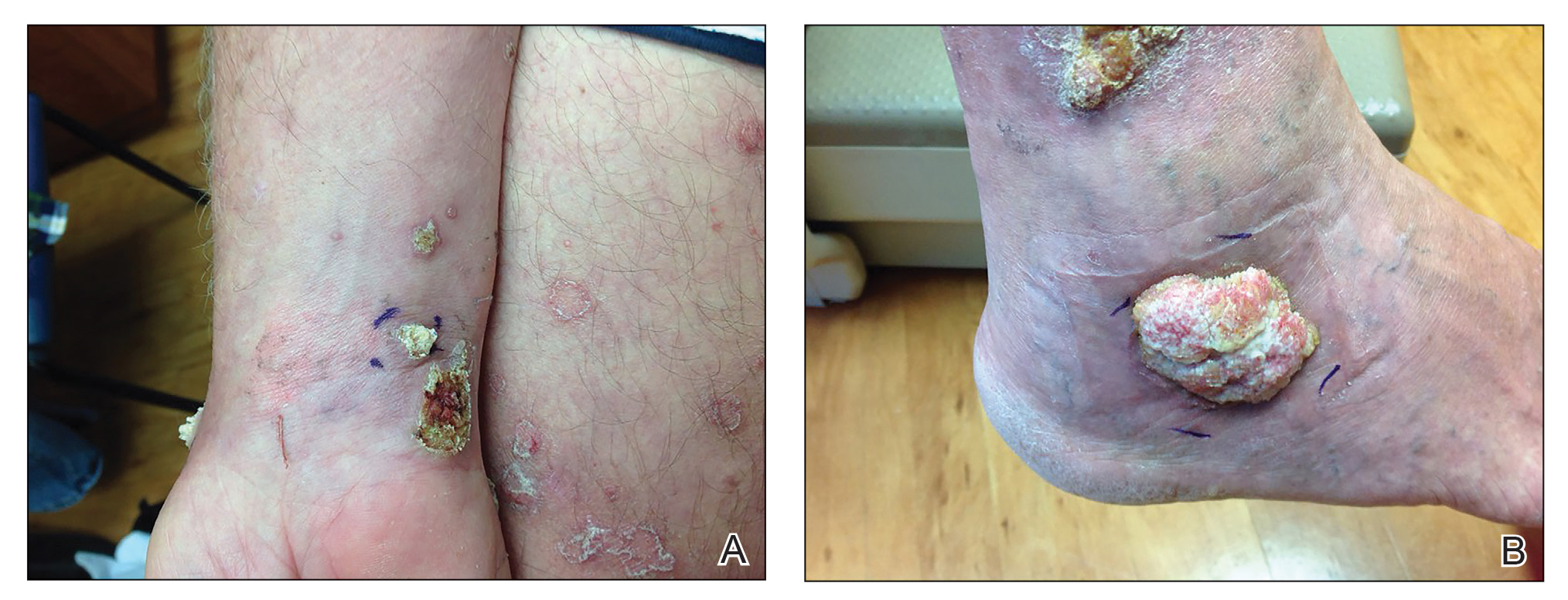

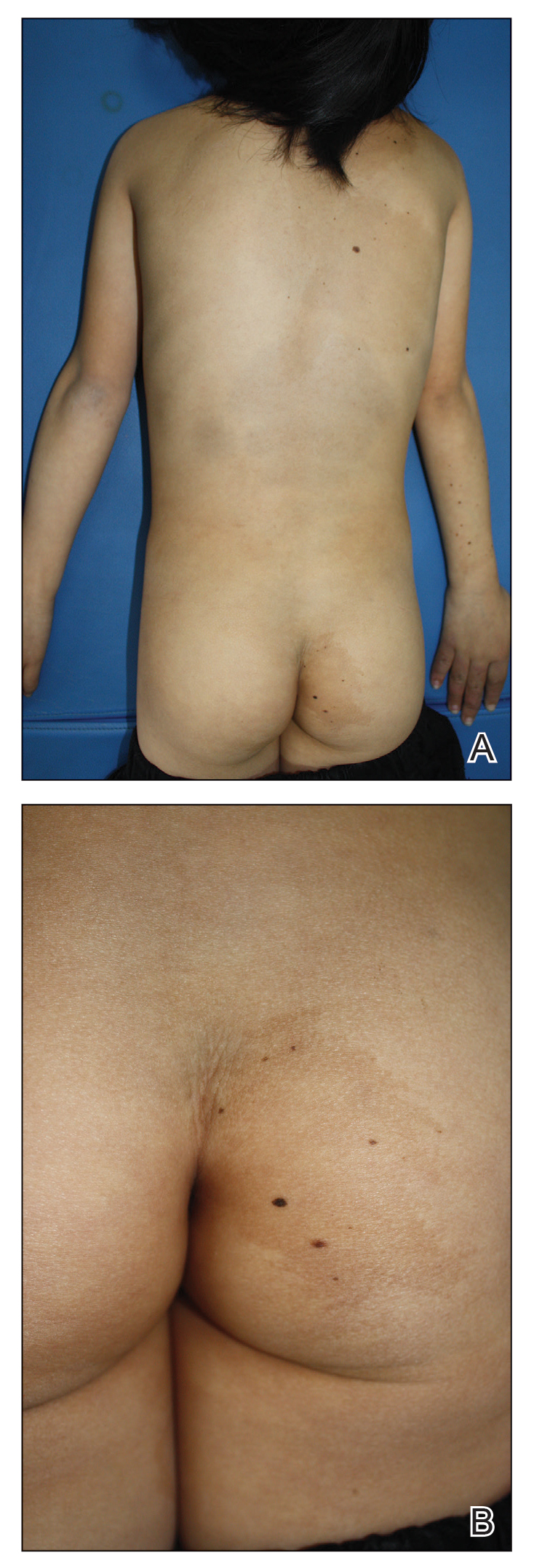

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

To the Editor:

A range of dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19 have been reported, including nonspecific maculopapular exanthems, urticaria, and varicellalike eruptions.1 Additionally, there have been sporadic accounts of cutaneous vasculopathic signs such as perniolike lesions, acro-ischemia, livedo reticularis, and retiform purpura.2 We describe exuberant hemorrhagic bullae occurring on the extremities of 2 critically ill patients with COVID-19. We hypothesized that the bullae were vasculopathic in nature and possibly exacerbated by peripheral intravenous (IV)–related injury.

A 62-year-old woman with a history of diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was admitted to the intensive care unit for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure secondary to COVID-19 infection. Dermatology was consulted for evaluation of blisters on the right arm. A new peripheral IV line was inserted into the patient’s right forearm for treatment of secondary methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The peripheral IV was inserted into the right proximal forearm for 2 days prior to development of ecchymosis and blisters. Intravenous medications included vancomycin, cefepime, methylprednisolone, and famotidine, as well as maintenance fluids (normal saline). Physical examination revealed extensive confluent ecchymoses with overlying tense bullae (Figure 1). Notable laboratory findings included an elevated D-dimer (peak of 8.67 μg/mL fibrinogen-equivalent units [FEUs], reference range <0.5 μg/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (789 mg/dL, reference range 200–400 mg/dL) levels. Three days later she developed worsening edema of the right arm, accompanied by more extensive bullae formation (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the right arm showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and subcutaneous edema. An orthopedic consultation determined that there was no compartment syndrome, and surgical intervention was not recommended. The patient’s course was complicated by multiorgan failure, and she died 18 days after admission.

A 67-year-old man with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, and hemiparesis secondary to stroke was admitted to the intensive care unit due to hypoxemia secondary to COVID-19 pneumonia. Dermatology was consulted for the evaluation of blisters on both arms. The right forearm peripheral IV line was used for 4 days prior to the development of cutaneous symptoms. Intravenous medications included cefepime, famotidine, and methylprednisolone. The left forearm peripheral IV line was in place for 1 day prior to the development of blisters and was used for the infusion of maintenance fluids (lactated Ringer’s solution). On the first day of the eruption, small bullae were noted at sites of prior peripheral IV lines (Figure 3). On day 3 of admission, the eruption progressed to larger and more confluent tense bullae with ecchymosis (Figure 4). Additionally, laboratory test results were notable for an elevated D-dimer (peak of >20.00 ug/mL FEU) and fibrinogen (748 mg/dL) levels. Computed tomography of the arms showed extensive subcutaneous stranding and fluid along the fascial planes of the arms, with no gas or abscess formation. Surgical intervention was not recommended following an orthopedic consultation. The patient’s course was complicated by acute kidney injury and rhabdomyolysis; he was later discharged to a skilled nursing facility in stable condition.

Reports from China indicate that approximately 50% of COVID-19 patients have elevated D-dimer levels and are at risk for thrombosis.3 We hypothesize that the exuberant hemorrhagic bullous eruptions in our 2 cases may be mediated in part by a hypercoagulable state secondary to COVID-19 infection combined with IV-related trauma or extravasation injury. However, a direct cytotoxic effect of the virus cannot be entirely excluded as a potential inciting factor. Other entities considered in the differential for localized bullae included trauma-induced bullous pemphigoid as well as bullous cellulitis. Both patients were treated with high-dose steroids as well as broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were expected to lead to improvement in symptoms of bullous pemphigoid and cellulitis, respectively; however, they did not lead to symptom improvement.

Extravasation injury results from unintentional administration of potentially vesicant substances into tissues surrounding the intended vascular channel.4 The mechanism of action of these injuries is postulated to arise from direct tissue injury from cytotoxic substances, elevated osmotic pressure, and reduced blood supply if vasoconstrictive substances are infused.5 In our patients, these injuries also may have promoted vascular occlusion leading to the brisk reaction observed. Although ecchymoses typically are associated with hypocoagulable states, both of our patients were noted to have normal platelet levels throughout hospitalization. Additionally, findings of elevated D-dimer and fibrinogen levels point to a hypercoagulable state. However, there is a possibility of platelet dysfunction leading to the observed cutaneous findings of ecchymoses. Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in patients with COVID-19 and is found to be associated with increased in-hospital mortality.6 Additional study of these reactions is needed given the propensity for multiorgan failure and death in patients with COVID-19 from suspected diffuse microvascular damage.3

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective [published online March 26, 2020]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.16387

- Zhang Y, Cao W, Xiao M, et al. Clinical and coagulation characteristics of 7 patients with critical COVID-19 pneumonia and acro-ischemia [in Chinese][published online March 28, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E006.

- Mei H, Hu Y. Characteristics, causes, diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 [in Chinese][published online March 14, 2020]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:E002.

- Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, et al. Vesicant extravasation part I: mechanisms, pathogenesis, and nursing care to reduce risk. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:1134-1141.

- Reynolds PM, MacLaren R, Mueller SW, et al. Management of extravasation injuries: a focused evaluation of noncytotoxic medications. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:617-632.

- Yang X, Yang Q, Wang Y, et al. Thrombocytopenia and its association with mortality in patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1469‐1472.

Practice Points

- Hemorrhagic bullae are an uncommon cutaneous manifestation of COVID-19 infection in hospitalized individuals.

- Although there is no reported treatment for COVID-19–associated hemorrhagic bullae, we recommend supportive care and management of underlying etiology.

Persistent Panniculitis in Dermatomyositis

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman with a history of dermatomyositis (DM) presented to dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple subcutaneous nodules. Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient was diagnosed by her primary care physician with DM based on clinical presentation. She initially developed body aches, muscle pain, and weakness of the upper extremities, specifically around the shoulders, and later the lower extremities, specifically around the thighs. The initial physical examination revealed pain with movement, tenderness to palpation, and proximal extremity weakness. The patient also noted a 50-lb weight loss. Over the next year, she noted dysphagia and developed multiple subcutaneous nodules on the right arm, chest, and left axilla. Subsequently, she developed a violaceous, hyperpigmented, periorbital rash and erythema of the anterior chest. She did not experience hair loss, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, or joint pain.

Laboratory testing in the months following the initial presentation revealed a creatine phosphokinase level of 436 U/L (reference range, 20–200 U/L), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h (reference range, <31 mm/h), and an aldolase level of 10.4 U/L (reference range, 1.0–8.0 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti–Jo-1 antibodies, and anti–smooth muscle antibodies all were negative. Total blood complement levels were elevated, but complement C3 and C4 were within normal limits. Imaging demonstrated normal chest radiographs, and a modified barium swallow confirmed swallowing dysfunction. A right quadricep muscle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of DM. A malignancy work-up including mammography, colonoscopy, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative aside from nodular opacities in the chest. She was treated with prednisone (60 mg, 0.9 mg/kg) daily and methotrexate (15–20 mg) weekly for several months. While the treatment attenuated the rash and improved weakness, the nodules persisted, prompting a referral to dermatology.

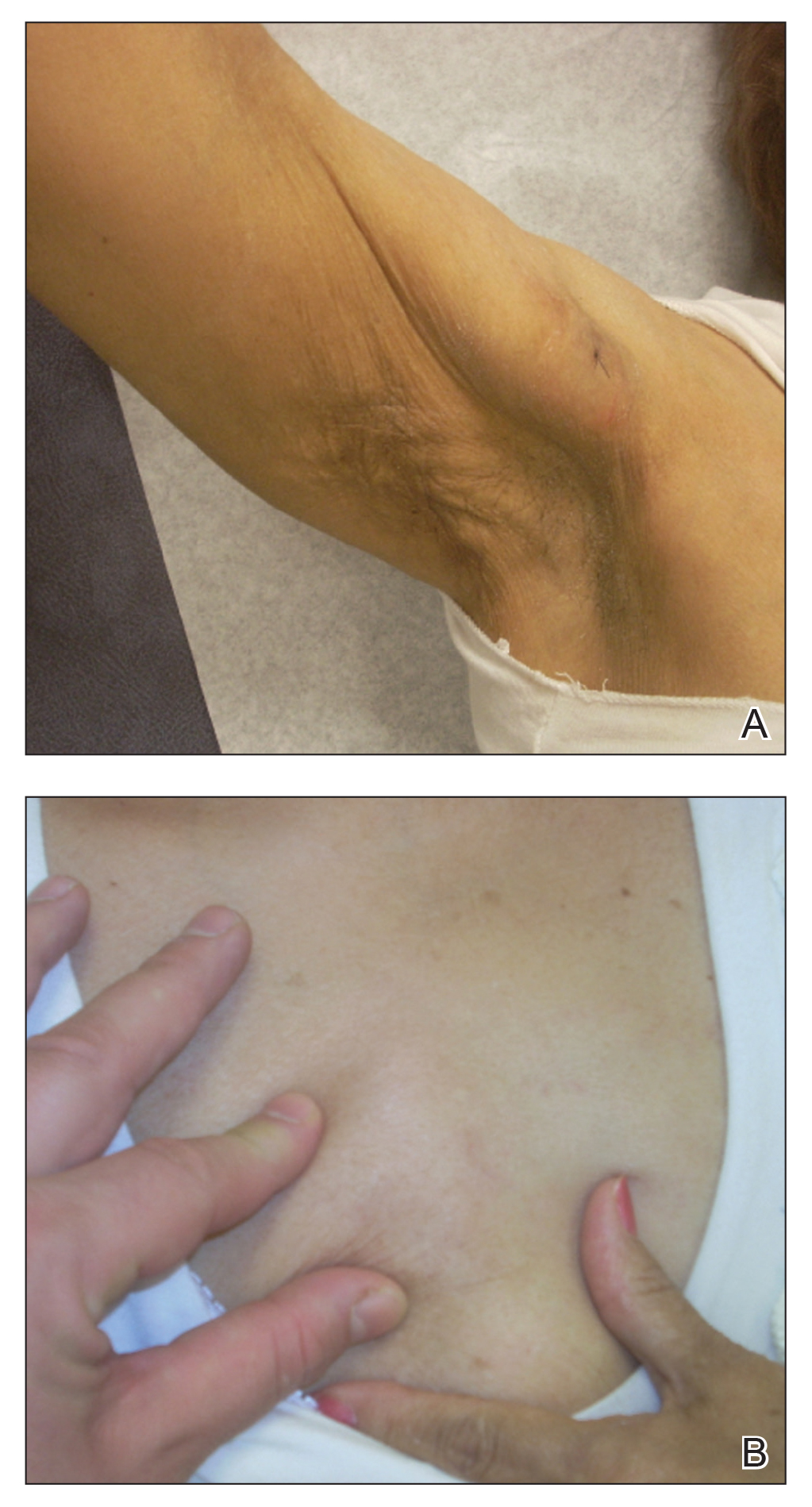

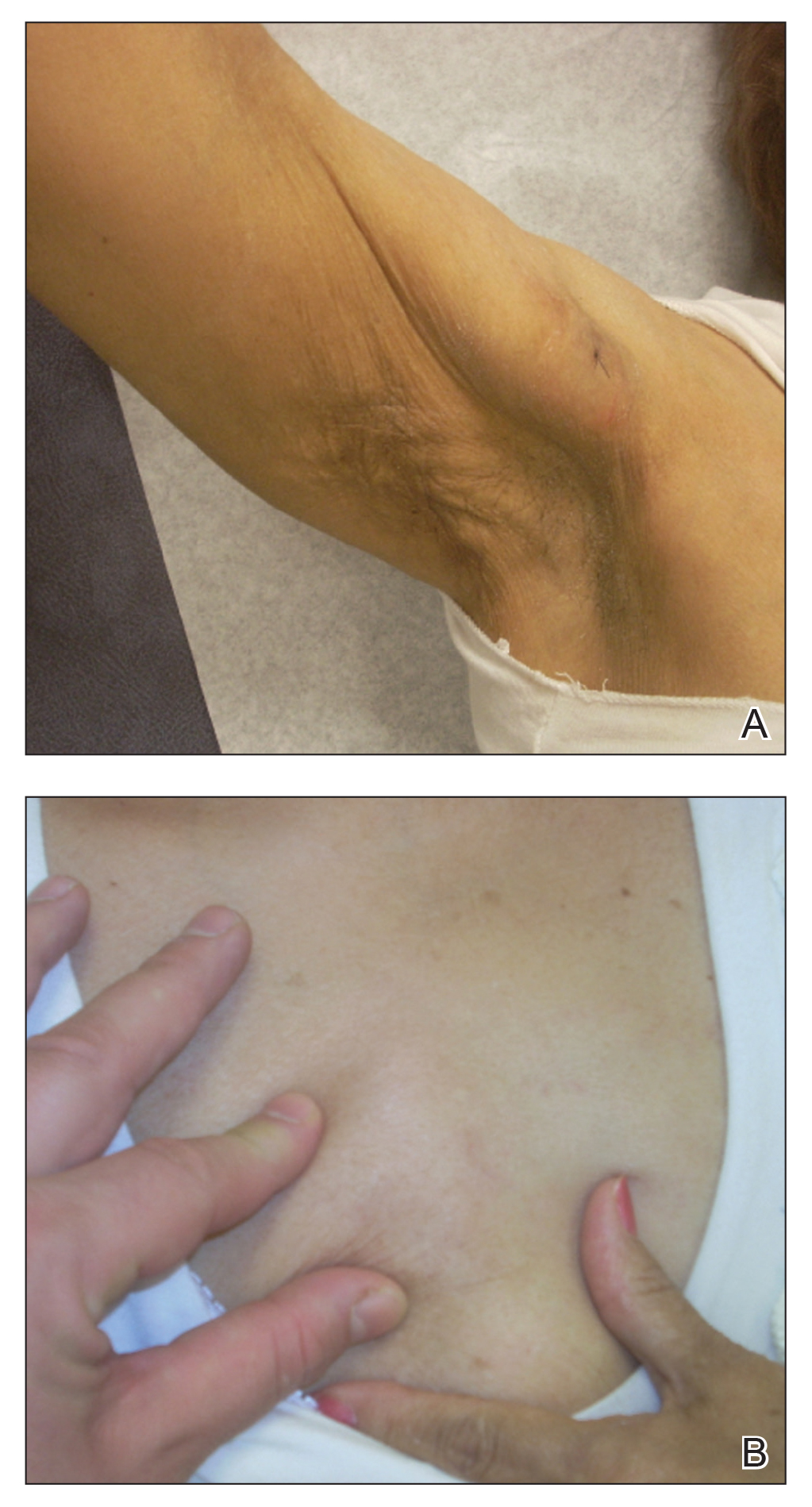

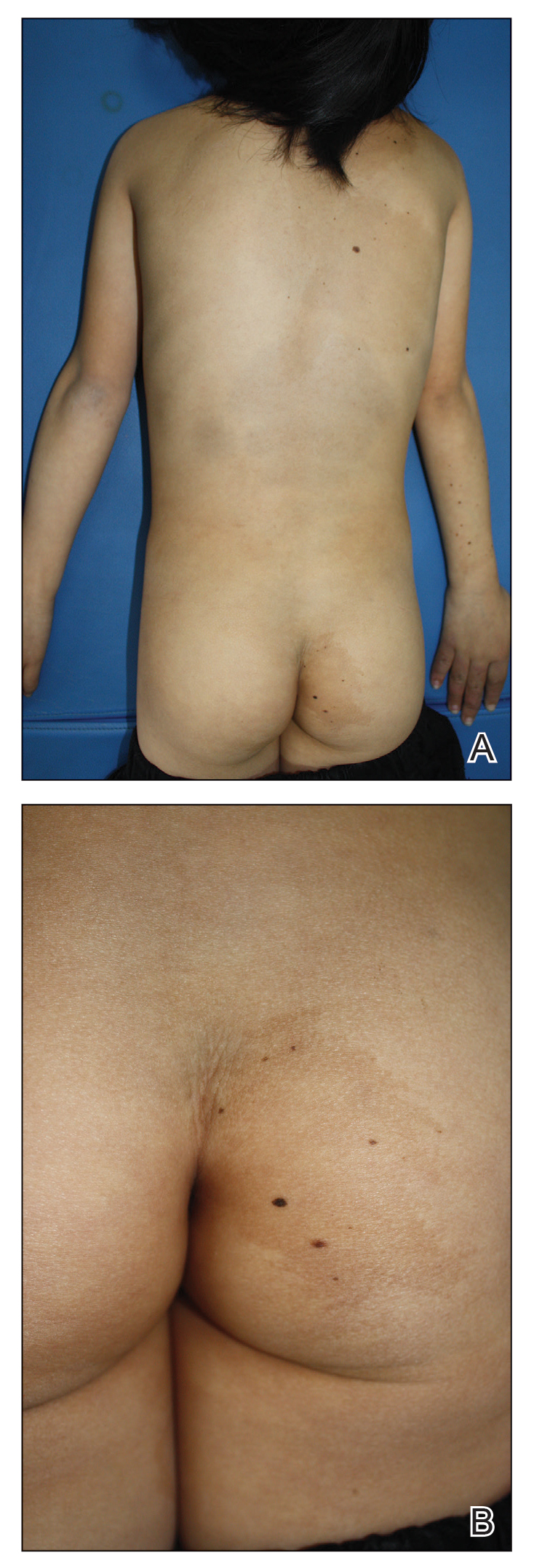

Physical examination at the dermatology clinic demonstrated the persistent subcutaneous nodules were indurated and bilaterally located on the arms, axillae, chest, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs with no pain or erythema (Figure). Laboratory tests demonstrated a normal creatine phosphokinase level, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (70 mm/h), and elevated aldolase level (9.3 U/L). Complement levels were elevated, though complement C3 and C4 remained within normal limits. Histopathology of nodules from the medial right upper arm and left thigh showed lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis, calcification, and interface changes. The patient was treated for several months with daily mycophenolate mofetil (1 g increased to 3 g) and daily hydroxychloroquine (200 mg) without any effect on the nodules.

The histologic features of panniculitis in lupus and DM are similar and include multifocal hyalinization of the subcuticular fat and diffuse lobular infiltrates of mature lymphocytes without nuclear atypia.1 Though clinical panniculitis is a rare finding in DM, histologic panniculitis is a relatively common finding.2 Despite the similar histopathology of lupus and DM, the presence of typical DM clinical and laboratory features in our patient (body aches, muscle pain, proximal weakness, cutaneous manifestations, elevated creatine phosphokinase, normal complement C3 and C4) made a diagnosis of DM more likely.

Clinical panniculitis is a rare subcutaneous manifestation of DM with around 50 cases reported in the literature (Table). A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms dermatomyositis and panniculitis through July 2019. Additionally, a full-text review and search of references within these articles was used to identify all cases of patients presenting with panniculitis in the setting of DM. Exclusion criteria were cases in which another etiology was considered likely (infectious panniculitis and lupus panniculitis) as well as those without an English translation. We identified 43 cases; the average age of the patients was 39.6 years, and 36 (83.7%) of the cases were women. Patients typically presented with persistent, indurated, painful, erythematous, nodular lesions localized to the arms, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs.

While panniculitis has been reported preceding and concurrent with a diagnosis of DM, a number of cases described presentation as late as 5 years following onset of classic DM symptoms.12,13,31 In some cases (3/43 [7.0%]), panniculitis was the only cutaneous manifestation of DM.15,33,36 However, it occurred more commonly with other characteristic skin findings, such as heliotrope rash or Gottron sign.Some investigators have recommended that panniculitis be included as a diagnostic feature of DM and that DM be considered in the differential diagnosis in isolated cases of panniculitis.25,33

Though it seems panniculitis in DM may correlate with a better prognosis, we identified underlying malignancies in 3 cases. Malignancies associated with panniculitis in DM included ovarian adenocarcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and parotid carcinoma, indicating that appropriate cancer screening still is critical in the diagnostic workup.2,11,22

A majority of the reported panniculitis cases in DM have responded to treatment with prednisone; however, treatment with prednisone has been more recalcitrant in other cases. Reports of successful additional therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, mepacrine, or a combination of these entities.19,22 In most cases, improvement of the panniculitis and other DM symptoms occurred simultaneously.25 It is noteworthy that the muscular symptoms often resolved more rapidly than cutaneous manifestations.33 Few reported cases (6 including the current case) found a persistent panniculitis despite improvement and remission of the myositis.3,5,10,11,30

Our patient was treated with both prednisone and methotrexate for several months, leading to remission of muscular symptoms (along with return to baseline of creatine phosphokinase), yet the panniculitis did not improve. The subcutaneous nodules also did not respond to treatment with mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine.

Recent immunohistochemical studies have suggested that panniculitic lesions show better outcomes with immunosuppressive therapy when compared with other DM-related skin lesions.40 However, this was not the case for our patient, who after months of immunosuppressive therapy showed complete resolution of the periorbital and chest rashes with persistence of multiple indurated subcutaneous nodules.

Our case adds to a number of reports of DM presenting with panniculitis. Our patient fit the classic demographic of previously reported cases, as she was an adult woman without evidence of underlying malignancy; however, our case remains an example of the therapeutic challenge that exists when encountering a persistent, treatment-resistant panniculitis despite resolution of all other features of DM.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Girouard SD, Velez NF, Penson RT, et al. Panniculitis associated with dermatomyositis and recurrent ovarian cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:740-744.

- van Dongen HM, van Vugt RM, Stoof TJ. Extensive persistent panniculitis in the context of dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:E187-E188.

- Choi YJ, Yoo WH. Panniculitis, a rare presentation of onset and exacerbation of juvenile dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:367-371.

- Azevedo PO, Castellen NR, Salai AF, et al. Panniculitis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:119-121.

- Agulló A, Hinds B, Larrea M, et al. Livedo racemosa, reticulated ulcerations, panniculitis and violaceous plaques in a 46-year-old woman. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:47-49.

- Hattori Y, Matsuyama K, Takahashi T, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis presenting with cellulitis-like erythema on the mandible as an initial symptom. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:110-114.

- Hasegawa A, Shimomura Y, Kibune N, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:551-553.

- Salman A, Kasapcopur O, Ergun T, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis: report of a case and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:951-953.

- Carroll M, Mellick N, Wagner G. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:224‐226.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kulthanan K, Manapajon A. Calcific panniculitis and nasopharyngeal cancer-associated adult-onset dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Springerplus. 2015;4:201.

- Otero Rivas MM, Vicente Villa A, González Lara L, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:574-575.

- Yanaba K, Tanito K, Hamaguchi Y, et al. Anti‐transcription intermediary factor‐1γ/α/β antibody‐positive dermatomyositis associated with multiple panniculitis lesions. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;20:1831-1834.

- Pau-Charles I, Moreno PJ, Ortiz-Ibanez K, et al. Anti-MDA5 positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting with severe cardiomyopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1097-1102.

- Lamb R, Digby S, Stewart W, et al. Cutaneous ulceration: more than skin deep? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:443-445.

- Arias M, Hernández MI, Cunha LG, et al. Panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:146-148.

- Hemmi S, Kushida R, Nishimura H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of panniculitis in dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:151-153.

- Geddes MR, Sinnreich M, Chalk C. Minocycline-induced dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:547-549.

- Abdul‐Wahab A, Holden CA, Harland C, et al Calcific panniculitis in adult‐onset dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E854-E856.

- Carneiro S, Alvim G, Resende P, et al. Dermatomyositis with panniculitis. Skinmed. 2007;6:46-47.

- Carrera E, Lobrinus JA, Spertini O, et al. Dermatomyositis, lobarpanniculitis and inflammatory myopathy with abundant macrophages. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:468-471.

- Lin JH, Chu CY, Lin RY. Panniculitis in adult onset dermatomyositis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2006;24:194-200.

- Chen GY, Liu MF, Lee JY, et al. Combination of massive mucinosis, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcer, bullae and fatal intestinal vasculopathy in a young female. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:396-400.

- Nakamori A, Yamaguchi Y, Kurimoto I, et al. Vesiculobullous dermatomyositis with panniculitis without muscle disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1136-1139.

- Solans R, Cortés J, Selva A, et al. Panniculitis: a cutaneous manifestation of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:S148-S150.

- Chao YY, Yang LJ. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:141-144.

- Lee MW, Lim YS, Choi JH, et al. Panniculitis showing membranocystic changes in the dermatomyositis. J Dermatol. 1999;26:608‐610.

- Ghali FE, Reed AM, Groben PA, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:270-272.

- Molnar K, Kemeny L, Korom I, et al. Panniculitis in dermatomyositis: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:161‐163.

- Ishikawa O, Tamura A, Ryuzaki K, et al. Membranocystic changes in the panniculitis of dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:773-776.

- Sabroe RA, Wallington TB, Kennedy CT. Dermatomyositis treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins and associated with panniculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:164-167.

- Neidenbach PJ, Sahn EE, Helton J. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:305-307.

- Fusade T, Belanyi P, Joly P, et al. Subcutaneous changes in dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:451-453.

- Winkelmann WJ, Billick RC, Srolovitz H. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:127-128.

- Commens C, O’Neill P, Walker G. Dermatomyositis associated with multifocal lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:966-969.

- Raimer SS, Solomon AR, Daniels JC. Polymyositis presenting with panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2 pt 2):366‐369.

- Feldman D, Hochberg MC, Zizic TM, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis in adult polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:85-89.

- Kimura S, Fukuyama Y. Tubular cytoplasmic inclusions in a case of childhood dermatomyositis with migratory subcutaneous nodules. Eur J Pediatr. 1977;125:275-283.

- Weber FP, Gray AMH. Chronic relapsing polydermatomyositis with predominant involvement of the subcutaneous fat. Br J Dermatol. 1924;36:544-560.

- Santos‐Briz A, Calle A, Linos K, et al. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 18 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1352-1359.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman with a history of dermatomyositis (DM) presented to dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple subcutaneous nodules. Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient was diagnosed by her primary care physician with DM based on clinical presentation. She initially developed body aches, muscle pain, and weakness of the upper extremities, specifically around the shoulders, and later the lower extremities, specifically around the thighs. The initial physical examination revealed pain with movement, tenderness to palpation, and proximal extremity weakness. The patient also noted a 50-lb weight loss. Over the next year, she noted dysphagia and developed multiple subcutaneous nodules on the right arm, chest, and left axilla. Subsequently, she developed a violaceous, hyperpigmented, periorbital rash and erythema of the anterior chest. She did not experience hair loss, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, or joint pain.

Laboratory testing in the months following the initial presentation revealed a creatine phosphokinase level of 436 U/L (reference range, 20–200 U/L), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h (reference range, <31 mm/h), and an aldolase level of 10.4 U/L (reference range, 1.0–8.0 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti–Jo-1 antibodies, and anti–smooth muscle antibodies all were negative. Total blood complement levels were elevated, but complement C3 and C4 were within normal limits. Imaging demonstrated normal chest radiographs, and a modified barium swallow confirmed swallowing dysfunction. A right quadricep muscle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of DM. A malignancy work-up including mammography, colonoscopy, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative aside from nodular opacities in the chest. She was treated with prednisone (60 mg, 0.9 mg/kg) daily and methotrexate (15–20 mg) weekly for several months. While the treatment attenuated the rash and improved weakness, the nodules persisted, prompting a referral to dermatology.

Physical examination at the dermatology clinic demonstrated the persistent subcutaneous nodules were indurated and bilaterally located on the arms, axillae, chest, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs with no pain or erythema (Figure). Laboratory tests demonstrated a normal creatine phosphokinase level, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (70 mm/h), and elevated aldolase level (9.3 U/L). Complement levels were elevated, though complement C3 and C4 remained within normal limits. Histopathology of nodules from the medial right upper arm and left thigh showed lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis, calcification, and interface changes. The patient was treated for several months with daily mycophenolate mofetil (1 g increased to 3 g) and daily hydroxychloroquine (200 mg) without any effect on the nodules.

The histologic features of panniculitis in lupus and DM are similar and include multifocal hyalinization of the subcuticular fat and diffuse lobular infiltrates of mature lymphocytes without nuclear atypia.1 Though clinical panniculitis is a rare finding in DM, histologic panniculitis is a relatively common finding.2 Despite the similar histopathology of lupus and DM, the presence of typical DM clinical and laboratory features in our patient (body aches, muscle pain, proximal weakness, cutaneous manifestations, elevated creatine phosphokinase, normal complement C3 and C4) made a diagnosis of DM more likely.

Clinical panniculitis is a rare subcutaneous manifestation of DM with around 50 cases reported in the literature (Table). A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms dermatomyositis and panniculitis through July 2019. Additionally, a full-text review and search of references within these articles was used to identify all cases of patients presenting with panniculitis in the setting of DM. Exclusion criteria were cases in which another etiology was considered likely (infectious panniculitis and lupus panniculitis) as well as those without an English translation. We identified 43 cases; the average age of the patients was 39.6 years, and 36 (83.7%) of the cases were women. Patients typically presented with persistent, indurated, painful, erythematous, nodular lesions localized to the arms, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs.

While panniculitis has been reported preceding and concurrent with a diagnosis of DM, a number of cases described presentation as late as 5 years following onset of classic DM symptoms.12,13,31 In some cases (3/43 [7.0%]), panniculitis was the only cutaneous manifestation of DM.15,33,36 However, it occurred more commonly with other characteristic skin findings, such as heliotrope rash or Gottron sign.Some investigators have recommended that panniculitis be included as a diagnostic feature of DM and that DM be considered in the differential diagnosis in isolated cases of panniculitis.25,33

Though it seems panniculitis in DM may correlate with a better prognosis, we identified underlying malignancies in 3 cases. Malignancies associated with panniculitis in DM included ovarian adenocarcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and parotid carcinoma, indicating that appropriate cancer screening still is critical in the diagnostic workup.2,11,22

A majority of the reported panniculitis cases in DM have responded to treatment with prednisone; however, treatment with prednisone has been more recalcitrant in other cases. Reports of successful additional therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, mepacrine, or a combination of these entities.19,22 In most cases, improvement of the panniculitis and other DM symptoms occurred simultaneously.25 It is noteworthy that the muscular symptoms often resolved more rapidly than cutaneous manifestations.33 Few reported cases (6 including the current case) found a persistent panniculitis despite improvement and remission of the myositis.3,5,10,11,30

Our patient was treated with both prednisone and methotrexate for several months, leading to remission of muscular symptoms (along with return to baseline of creatine phosphokinase), yet the panniculitis did not improve. The subcutaneous nodules also did not respond to treatment with mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine.

Recent immunohistochemical studies have suggested that panniculitic lesions show better outcomes with immunosuppressive therapy when compared with other DM-related skin lesions.40 However, this was not the case for our patient, who after months of immunosuppressive therapy showed complete resolution of the periorbital and chest rashes with persistence of multiple indurated subcutaneous nodules.

Our case adds to a number of reports of DM presenting with panniculitis. Our patient fit the classic demographic of previously reported cases, as she was an adult woman without evidence of underlying malignancy; however, our case remains an example of the therapeutic challenge that exists when encountering a persistent, treatment-resistant panniculitis despite resolution of all other features of DM.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old woman with a history of dermatomyositis (DM) presented to dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple subcutaneous nodules. Two years prior to the current presentation, the patient was diagnosed by her primary care physician with DM based on clinical presentation. She initially developed body aches, muscle pain, and weakness of the upper extremities, specifically around the shoulders, and later the lower extremities, specifically around the thighs. The initial physical examination revealed pain with movement, tenderness to palpation, and proximal extremity weakness. The patient also noted a 50-lb weight loss. Over the next year, she noted dysphagia and developed multiple subcutaneous nodules on the right arm, chest, and left axilla. Subsequently, she developed a violaceous, hyperpigmented, periorbital rash and erythema of the anterior chest. She did not experience hair loss, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, or joint pain.

Laboratory testing in the months following the initial presentation revealed a creatine phosphokinase level of 436 U/L (reference range, 20–200 U/L), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h (reference range, <31 mm/h), and an aldolase level of 10.4 U/L (reference range, 1.0–8.0 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Antinuclear antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein, anti–Jo-1 antibodies, and anti–smooth muscle antibodies all were negative. Total blood complement levels were elevated, but complement C3 and C4 were within normal limits. Imaging demonstrated normal chest radiographs, and a modified barium swallow confirmed swallowing dysfunction. A right quadricep muscle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of DM. A malignancy work-up including mammography, colonoscopy, and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative aside from nodular opacities in the chest. She was treated with prednisone (60 mg, 0.9 mg/kg) daily and methotrexate (15–20 mg) weekly for several months. While the treatment attenuated the rash and improved weakness, the nodules persisted, prompting a referral to dermatology.

Physical examination at the dermatology clinic demonstrated the persistent subcutaneous nodules were indurated and bilaterally located on the arms, axillae, chest, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs with no pain or erythema (Figure). Laboratory tests demonstrated a normal creatine phosphokinase level, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (70 mm/h), and elevated aldolase level (9.3 U/L). Complement levels were elevated, though complement C3 and C4 remained within normal limits. Histopathology of nodules from the medial right upper arm and left thigh showed lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis, calcification, and interface changes. The patient was treated for several months with daily mycophenolate mofetil (1 g increased to 3 g) and daily hydroxychloroquine (200 mg) without any effect on the nodules.

The histologic features of panniculitis in lupus and DM are similar and include multifocal hyalinization of the subcuticular fat and diffuse lobular infiltrates of mature lymphocytes without nuclear atypia.1 Though clinical panniculitis is a rare finding in DM, histologic panniculitis is a relatively common finding.2 Despite the similar histopathology of lupus and DM, the presence of typical DM clinical and laboratory features in our patient (body aches, muscle pain, proximal weakness, cutaneous manifestations, elevated creatine phosphokinase, normal complement C3 and C4) made a diagnosis of DM more likely.

Clinical panniculitis is a rare subcutaneous manifestation of DM with around 50 cases reported in the literature (Table). A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the terms dermatomyositis and panniculitis through July 2019. Additionally, a full-text review and search of references within these articles was used to identify all cases of patients presenting with panniculitis in the setting of DM. Exclusion criteria were cases in which another etiology was considered likely (infectious panniculitis and lupus panniculitis) as well as those without an English translation. We identified 43 cases; the average age of the patients was 39.6 years, and 36 (83.7%) of the cases were women. Patients typically presented with persistent, indurated, painful, erythematous, nodular lesions localized to the arms, abdomen, buttocks, and thighs.

While panniculitis has been reported preceding and concurrent with a diagnosis of DM, a number of cases described presentation as late as 5 years following onset of classic DM symptoms.12,13,31 In some cases (3/43 [7.0%]), panniculitis was the only cutaneous manifestation of DM.15,33,36 However, it occurred more commonly with other characteristic skin findings, such as heliotrope rash or Gottron sign.Some investigators have recommended that panniculitis be included as a diagnostic feature of DM and that DM be considered in the differential diagnosis in isolated cases of panniculitis.25,33

Though it seems panniculitis in DM may correlate with a better prognosis, we identified underlying malignancies in 3 cases. Malignancies associated with panniculitis in DM included ovarian adenocarcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, and parotid carcinoma, indicating that appropriate cancer screening still is critical in the diagnostic workup.2,11,22

A majority of the reported panniculitis cases in DM have responded to treatment with prednisone; however, treatment with prednisone has been more recalcitrant in other cases. Reports of successful additional therapies include methotrexate, cyclosporine, azathioprine, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, mepacrine, or a combination of these entities.19,22 In most cases, improvement of the panniculitis and other DM symptoms occurred simultaneously.25 It is noteworthy that the muscular symptoms often resolved more rapidly than cutaneous manifestations.33 Few reported cases (6 including the current case) found a persistent panniculitis despite improvement and remission of the myositis.3,5,10,11,30

Our patient was treated with both prednisone and methotrexate for several months, leading to remission of muscular symptoms (along with return to baseline of creatine phosphokinase), yet the panniculitis did not improve. The subcutaneous nodules also did not respond to treatment with mycophenolate mofetil and hydroxychloroquine.

Recent immunohistochemical studies have suggested that panniculitic lesions show better outcomes with immunosuppressive therapy when compared with other DM-related skin lesions.40 However, this was not the case for our patient, who after months of immunosuppressive therapy showed complete resolution of the periorbital and chest rashes with persistence of multiple indurated subcutaneous nodules.

Our case adds to a number of reports of DM presenting with panniculitis. Our patient fit the classic demographic of previously reported cases, as she was an adult woman without evidence of underlying malignancy; however, our case remains an example of the therapeutic challenge that exists when encountering a persistent, treatment-resistant panniculitis despite resolution of all other features of DM.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Girouard SD, Velez NF, Penson RT, et al. Panniculitis associated with dermatomyositis and recurrent ovarian cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:740-744.

- van Dongen HM, van Vugt RM, Stoof TJ. Extensive persistent panniculitis in the context of dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:E187-E188.

- Choi YJ, Yoo WH. Panniculitis, a rare presentation of onset and exacerbation of juvenile dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:367-371.

- Azevedo PO, Castellen NR, Salai AF, et al. Panniculitis associated with amyopathic dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:119-121.

- Agulló A, Hinds B, Larrea M, et al. Livedo racemosa, reticulated ulcerations, panniculitis and violaceous plaques in a 46-year-old woman. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2018;9:47-49.

- Hattori Y, Matsuyama K, Takahashi T, et al. Anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis presenting with cellulitis-like erythema on the mandible as an initial symptom. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:110-114.

- Hasegawa A, Shimomura Y, Kibune N, et al. Panniculitis as the initial manifestation of dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibody. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:551-553.

- Salman A, Kasapcopur O, Ergun T, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis: report of a case and review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2016;43:951-953.

- Carroll M, Mellick N, Wagner G. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:224‐226.

- Chairatchaneeboon M, Kulthanan K, Manapajon A. Calcific panniculitis and nasopharyngeal cancer-associated adult-onset dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Springerplus. 2015;4:201.

- Otero Rivas MM, Vicente Villa A, González Lara L, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:574-575.

- Yanaba K, Tanito K, Hamaguchi Y, et al. Anti‐transcription intermediary factor‐1γ/α/β antibody‐positive dermatomyositis associated with multiple panniculitis lesions. Int J Rheum Dis. 2015;20:1831-1834.

- Pau-Charles I, Moreno PJ, Ortiz-Ibanez K, et al. Anti-MDA5 positive clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis presenting with severe cardiomyopathy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1097-1102.

- Lamb R, Digby S, Stewart W, et al. Cutaneous ulceration: more than skin deep? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:443-445.

- Arias M, Hernández MI, Cunha LG, et al. Panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:146-148.

- Hemmi S, Kushida R, Nishimura H, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging diagnosis of panniculitis in dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:151-153.

- Geddes MR, Sinnreich M, Chalk C. Minocycline-induced dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:547-549.

- Abdul‐Wahab A, Holden CA, Harland C, et al Calcific panniculitis in adult‐onset dermatomyositis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:E854-E856.

- Carneiro S, Alvim G, Resende P, et al. Dermatomyositis with panniculitis. Skinmed. 2007;6:46-47.

- Carrera E, Lobrinus JA, Spertini O, et al. Dermatomyositis, lobarpanniculitis and inflammatory myopathy with abundant macrophages. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:468-471.

- Lin JH, Chu CY, Lin RY. Panniculitis in adult onset dermatomyositis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dermatol Sinica. 2006;24:194-200.

- Chen GY, Liu MF, Lee JY, et al. Combination of massive mucinosis, dermatomyositis, pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcer, bullae and fatal intestinal vasculopathy in a young female. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:396-400.

- Nakamori A, Yamaguchi Y, Kurimoto I, et al. Vesiculobullous dermatomyositis with panniculitis without muscle disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:1136-1139.

- Solans R, Cortés J, Selva A, et al. Panniculitis: a cutaneous manifestation of dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:S148-S150.

- Chao YY, Yang LJ. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:141-144.

- Lee MW, Lim YS, Choi JH, et al. Panniculitis showing membranocystic changes in the dermatomyositis. J Dermatol. 1999;26:608‐610.

- Ghali FE, Reed AM, Groben PA, et al. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16:270-272.

- Molnar K, Kemeny L, Korom I, et al. Panniculitis in dermatomyositis: report of two cases. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:161‐163.

- Ishikawa O, Tamura A, Ryuzaki K, et al. Membranocystic changes in the panniculitis of dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:773-776.

- Sabroe RA, Wallington TB, Kennedy CT. Dermatomyositis treated with high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins and associated with panniculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:164-167.

- Neidenbach PJ, Sahn EE, Helton J. Panniculitis in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:305-307.

- Fusade T, Belanyi P, Joly P, et al. Subcutaneous changes in dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:451-453.

- Winkelmann WJ, Billick RC, Srolovitz H. Dermatomyositis presenting as panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:127-128.

- Commens C, O’Neill P, Walker G. Dermatomyositis associated with multifocal lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:966-969.

- Raimer SS, Solomon AR, Daniels JC. Polymyositis presenting with panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13(2 pt 2):366‐369.

- Feldman D, Hochberg MC, Zizic TM, et al. Cutaneous vasculitis in adult polymyositis/dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:85-89.

- Kimura S, Fukuyama Y. Tubular cytoplasmic inclusions in a case of childhood dermatomyositis with migratory subcutaneous nodules. Eur J Pediatr. 1977;125:275-283.

- Weber FP, Gray AMH. Chronic relapsing polydermatomyositis with predominant involvement of the subcutaneous fat. Br J Dermatol. 1924;36:544-560.

- Santos‐Briz A, Calle A, Linos K, et al. Dermatomyositis panniculitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 18 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1352-1359.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: a summary. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34:261-272.

- Girouard SD, Velez NF, Penson RT, et al. Panniculitis associated with dermatomyositis and recurrent ovarian cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:740-744.

- van Dongen HM, van Vugt RM, Stoof TJ. Extensive persistent panniculitis in the context of dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:E187-E188.

- Choi YJ, Yoo WH. Panniculitis, a rare presentation of onset and exacerbation of juvenile dermatomyositis: a case report and literature review. Arch Rheumatol. 2018;33:367-371.