User login

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease in an Adolescent Boy

To the Editor:

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease, also called histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, was described in 1972 by both Kikuchi1 and Fujimoto et al.2 Most cases are reported in Asia, with limited reports in the United States.3-5 Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare, self-limiting condition consisting of benign lymphadenopathy and oftentimes fever and systemic symptoms. Lymph node involvement may mimic non-Hodgkin lymphoma or other reactive lymphadenopathy, rendering diagnostic accuracy challenging.5 Cutaneous manifestations are reported in only 16% to 40% of patients.6,7 Herein, we describe the clinical and pathologic features of a case of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease with cutaneous involvement in an adolescent boy.

A 13-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history presented to the pediatric emergency department with cervical lymphadenopathy, weight loss, intermittent fever, and an evolving rash on the face, ears, arms, and thighs of 6 weeks’ duration. The illness began with enlarged lymph nodes and erythematous macules on the face and was diagnosed by his primary care physician as lymphadenitis that was unresponsive to clindamycin. Over the subsequent weeks, the rash worsened, and he developed intermittent fevers, night sweats, abdominal pain, and nausea with a 20-pound weight loss. He presented to the emergency department 3 weeks prior to the current admission and was noted to have elevated cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgM and IgG in addition to lymphopenia and anemia. He was discharged with outpatient follow-up. The rash progressed to involve the face, ears, arms, and thighs. One day prior to the current admission, the patient’s abdominal pain worsened acutely, and he experienced several episodes of emesis. He presented to the pediatric emergency department for further evaluation, and a dermatology consultation was requested at that time.

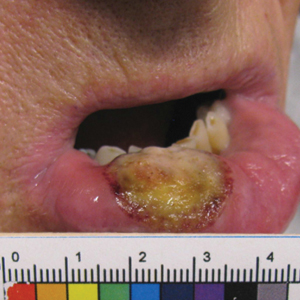

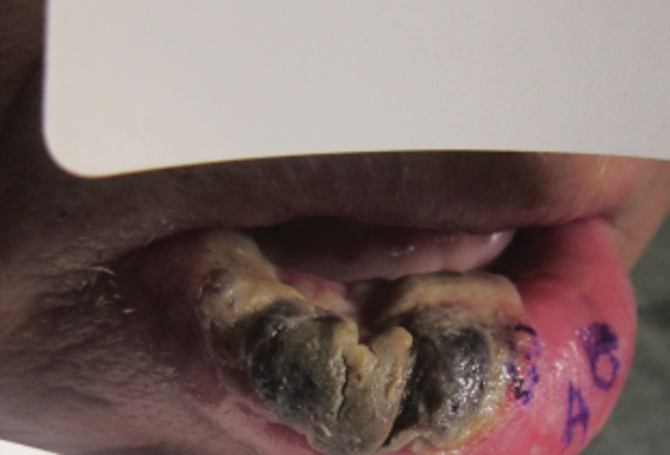

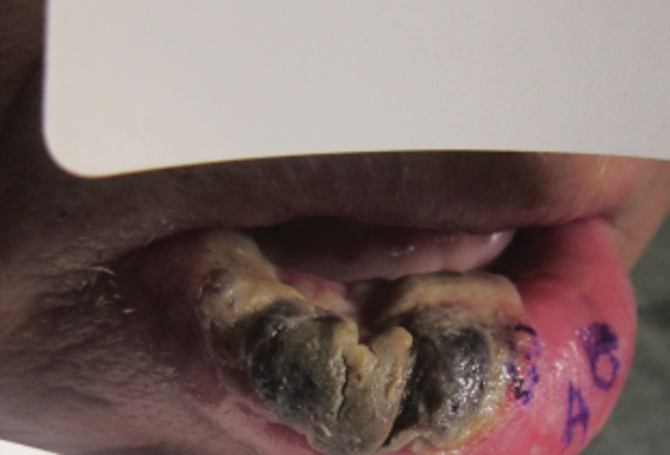

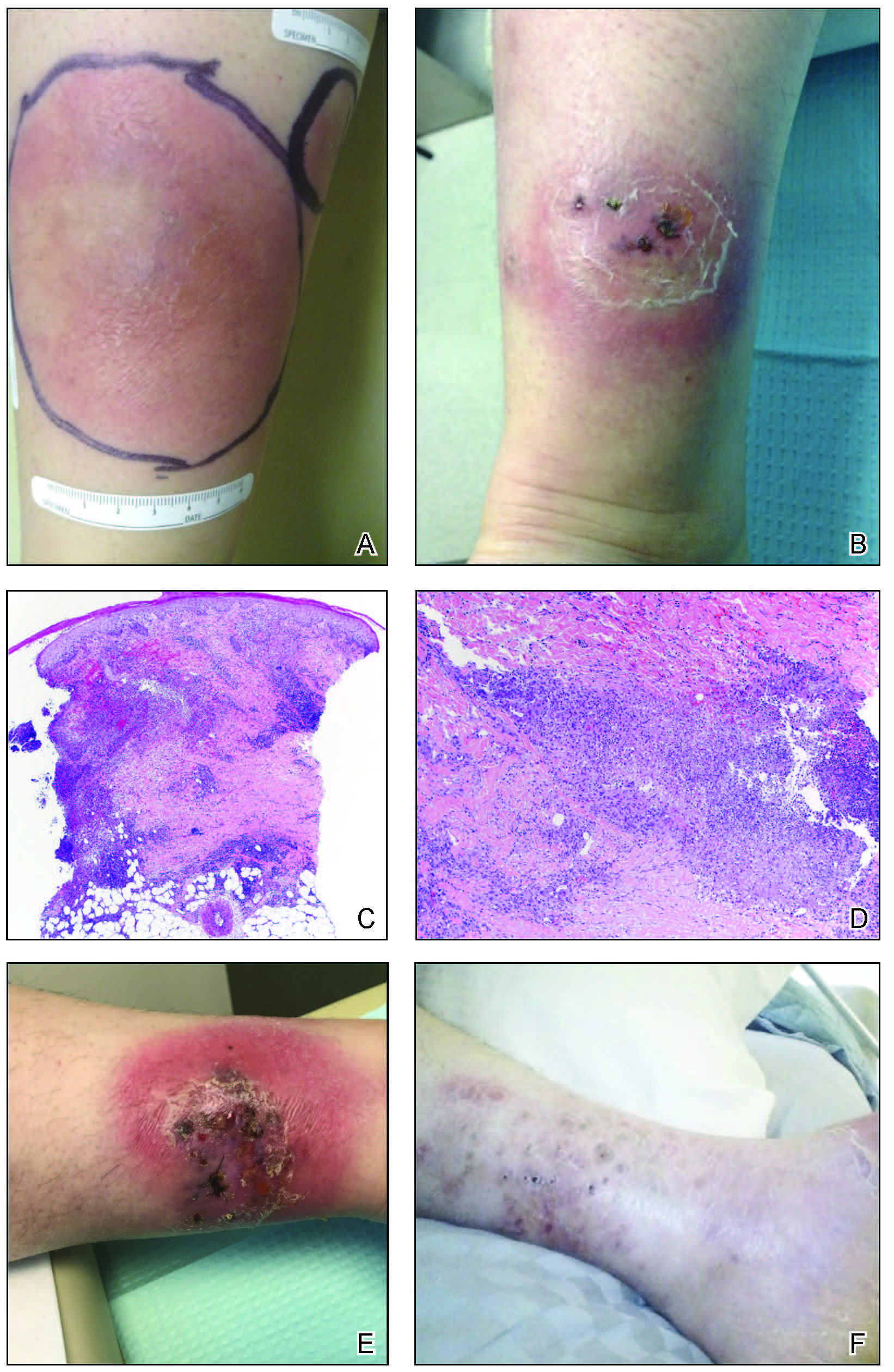

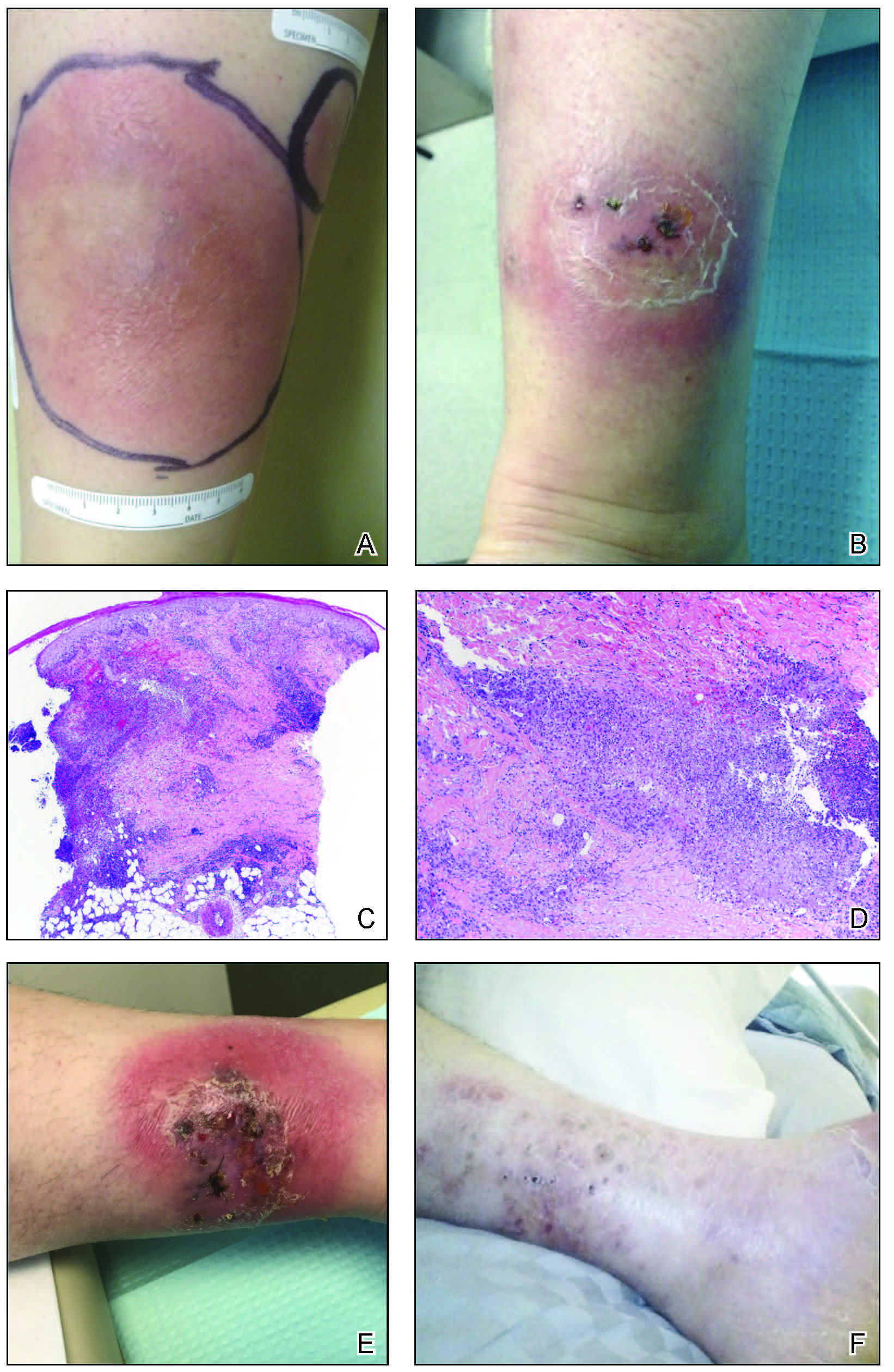

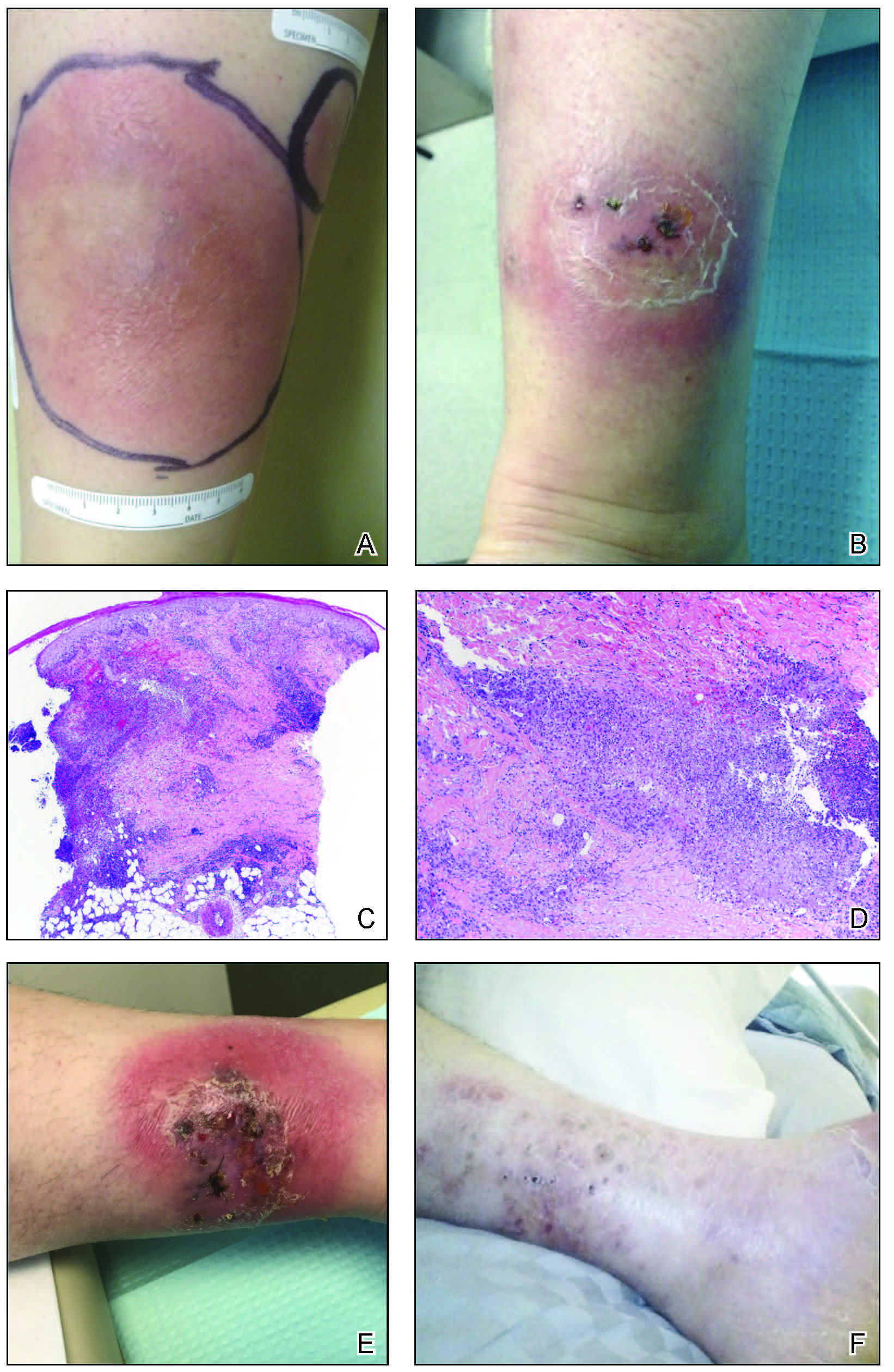

The patient’s rash was asymptomatic. In addition to the above symptoms, he also noted frequent nosebleeds, gingival bleeding, and diffuse myalgia that was most prominent on the hands and feet; he denied diarrhea, sick contacts, recent travel, or insect bites. His vital signs were normal, and he remained afebrile throughout the hospitalization. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing patient with sunken eyes and dry lips. He had pink, oval, scaly plaques on the cheeks, ears, and arms (Figure 1). The thighs exhibited folliculocentric erythematous papules. The ocular conjunctivae were clear, but white exudative plaques were noted on the tongue. Tender, bilateral, cervical lymphadenopathy and diffuse abdominal tenderness with guarding and hepatosplenomegaly also were present. The fingers and toes were tender upon palpation.

Laboratory workup at admission revealed the following: low white blood cell count, 2700/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL); low hemoglobin, 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL); elevated aspartate aminotransferase, 91 U/L (reference range, 10–30 U/L); and elevated alanine aminotransferase, 118 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase (582 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]), ferritin (1681 ng/mL [reference range, 15–200 ng/mL]), and C-reactive protein (6.0 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]) also were elevated. A respiratory viral panel was unremarkable. Blood cultures were negative, and an HIV 1/2 assay was nonreactive. A chest radiograph demonstrated clear lung fields. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed prominent mesenteric, ileocolic, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

The differential diagnoses at this time included acute connective tissue disease, a paraneoplastic phenomenon, cutaneous lymphoma, or an infectious etiology. A punch biopsy of the skin as well as tissue cultures were performed from a lesion on the right arm. Quantitative immunoglobulin (IgA, IgG, IgM) levels were checked, all of which were within reference range. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) assay and rheumatoid factor were normal.

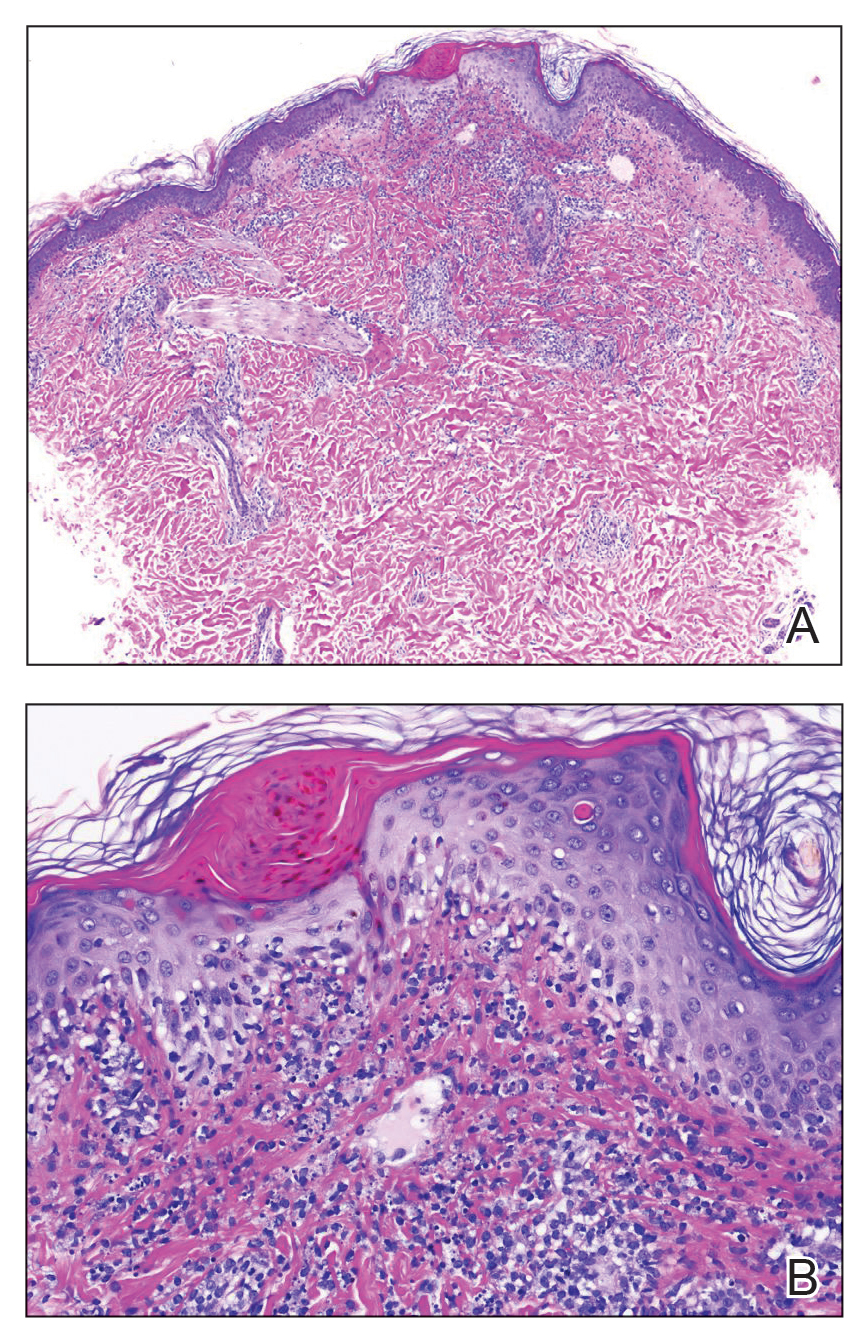

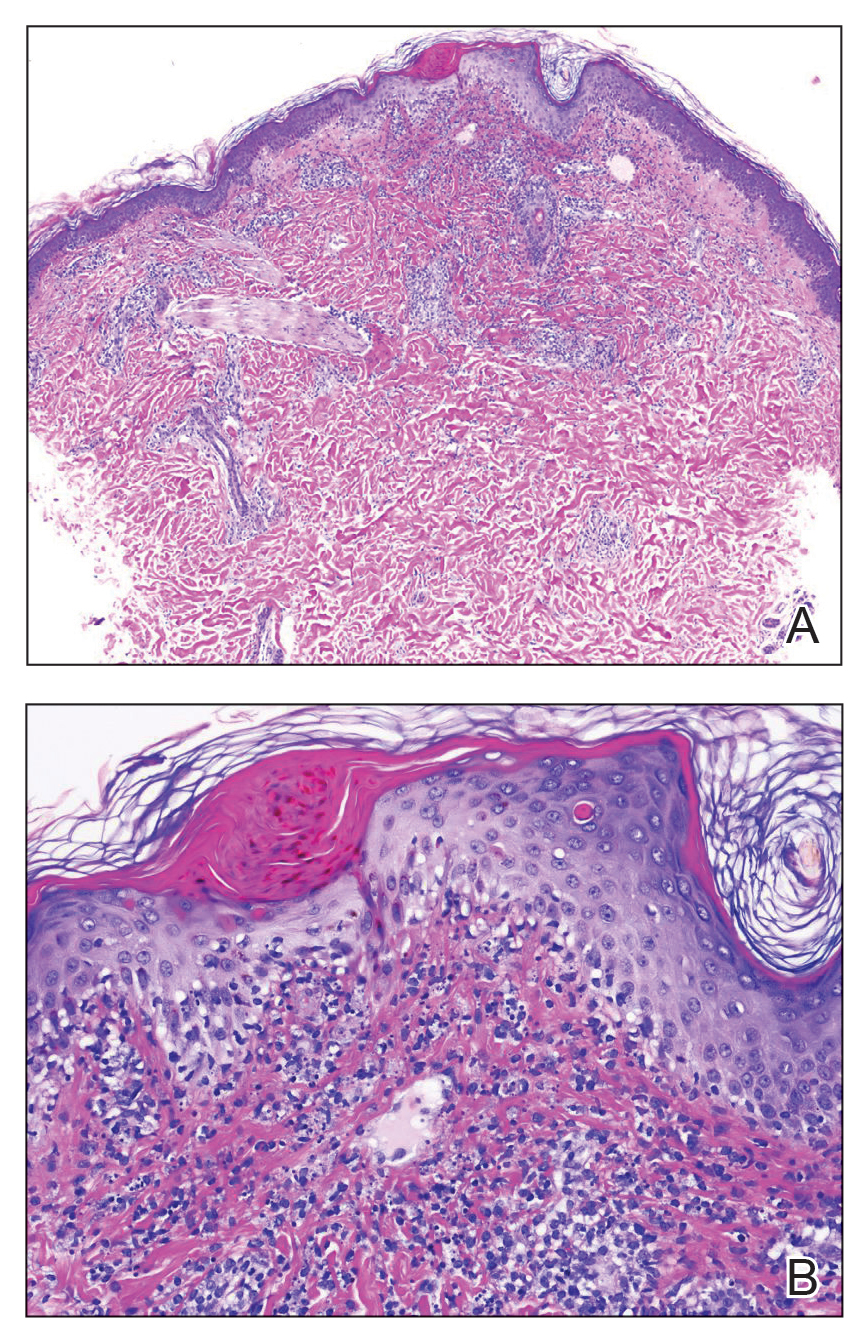

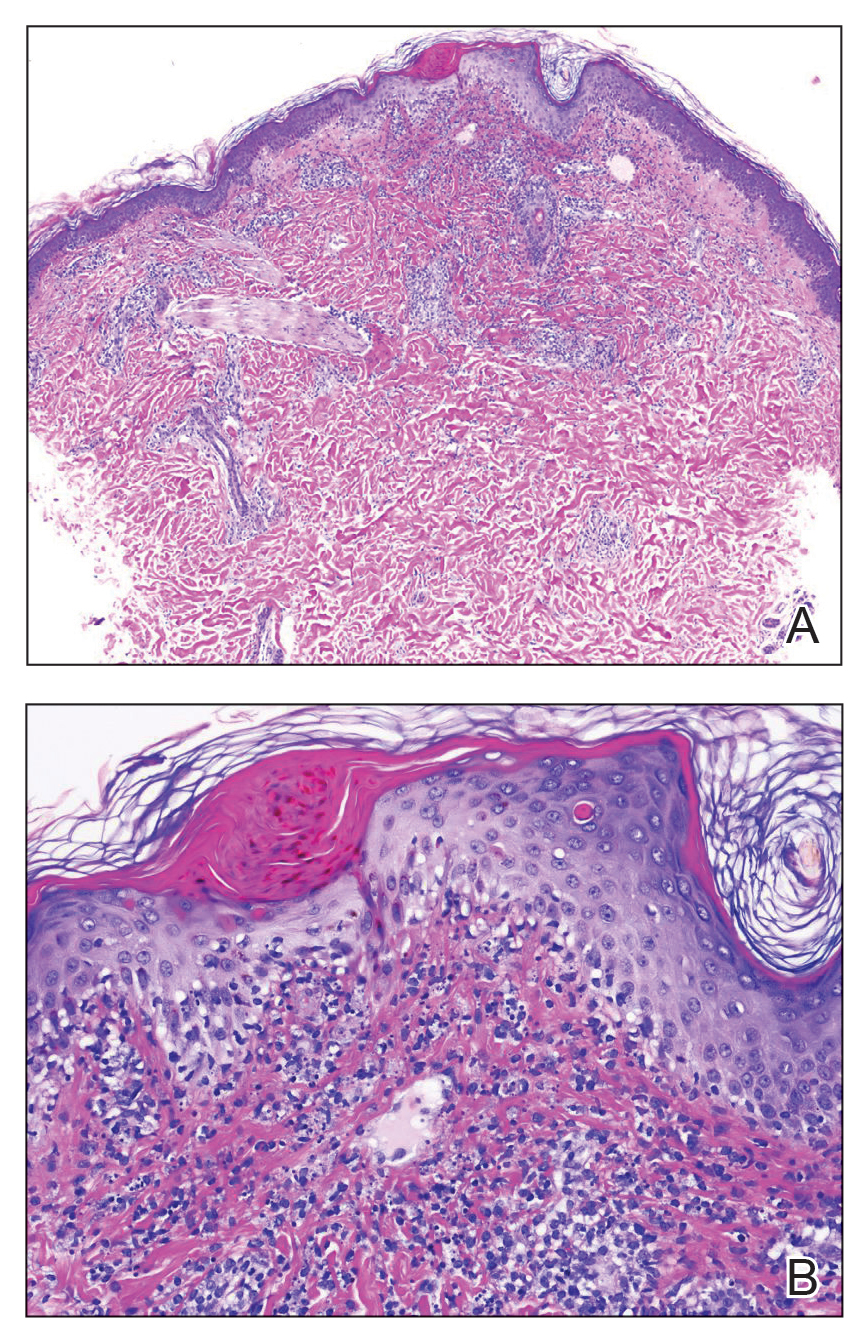

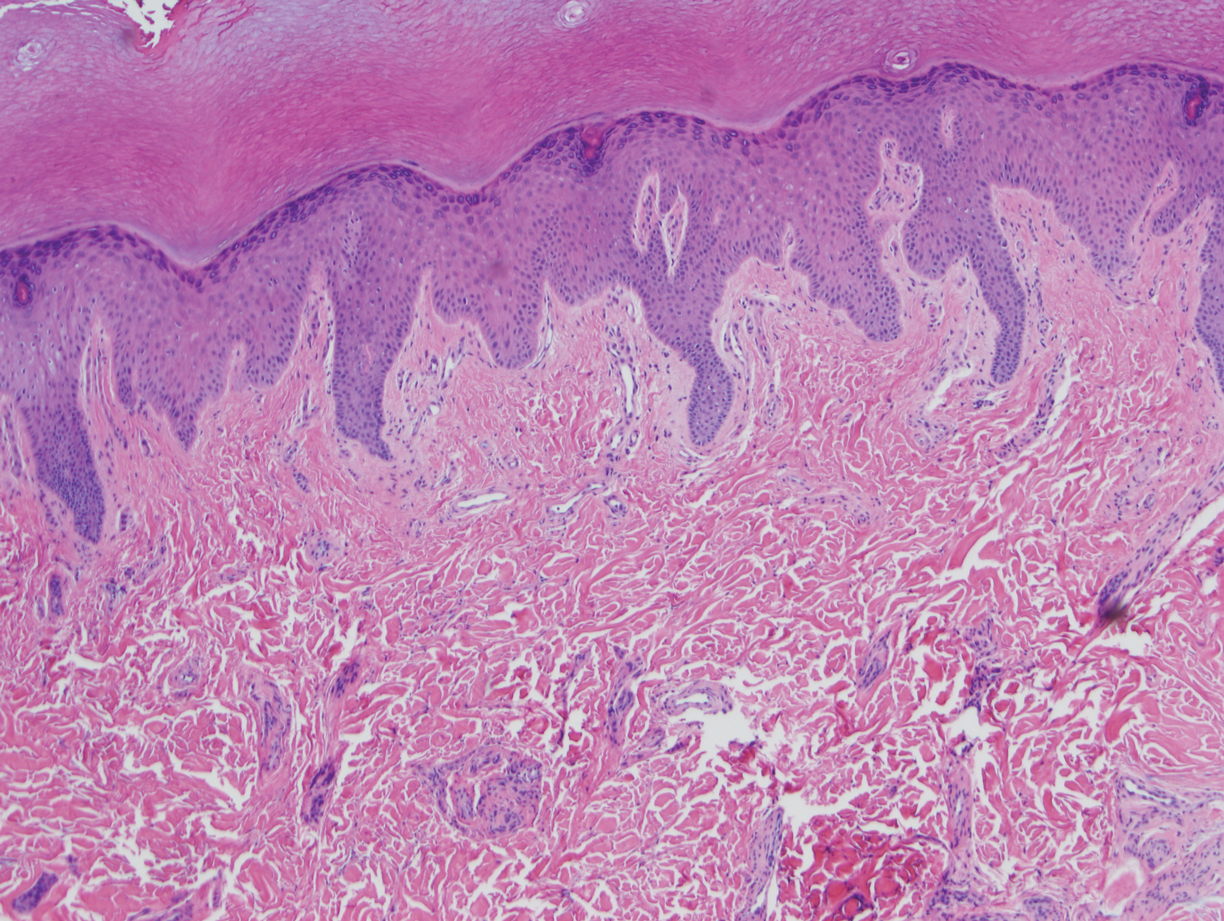

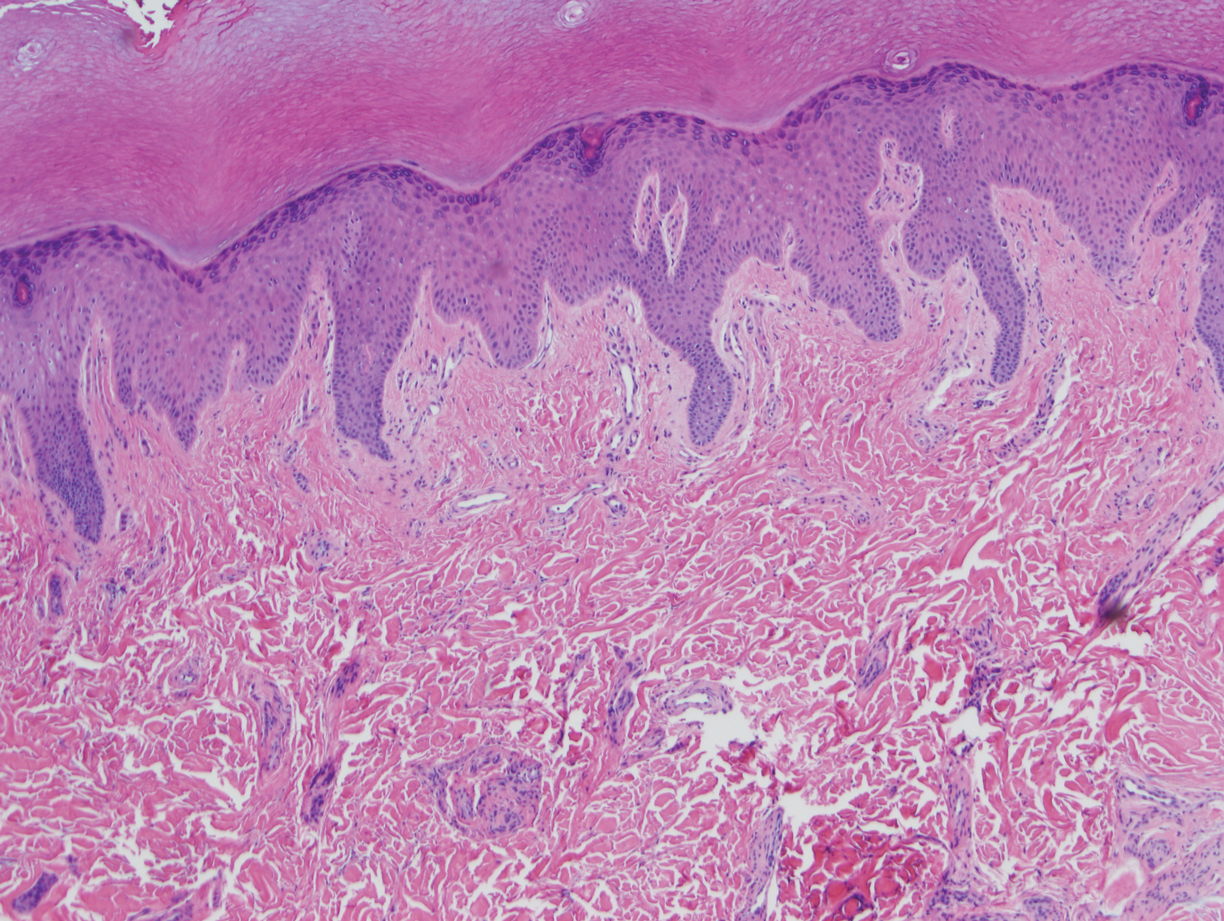

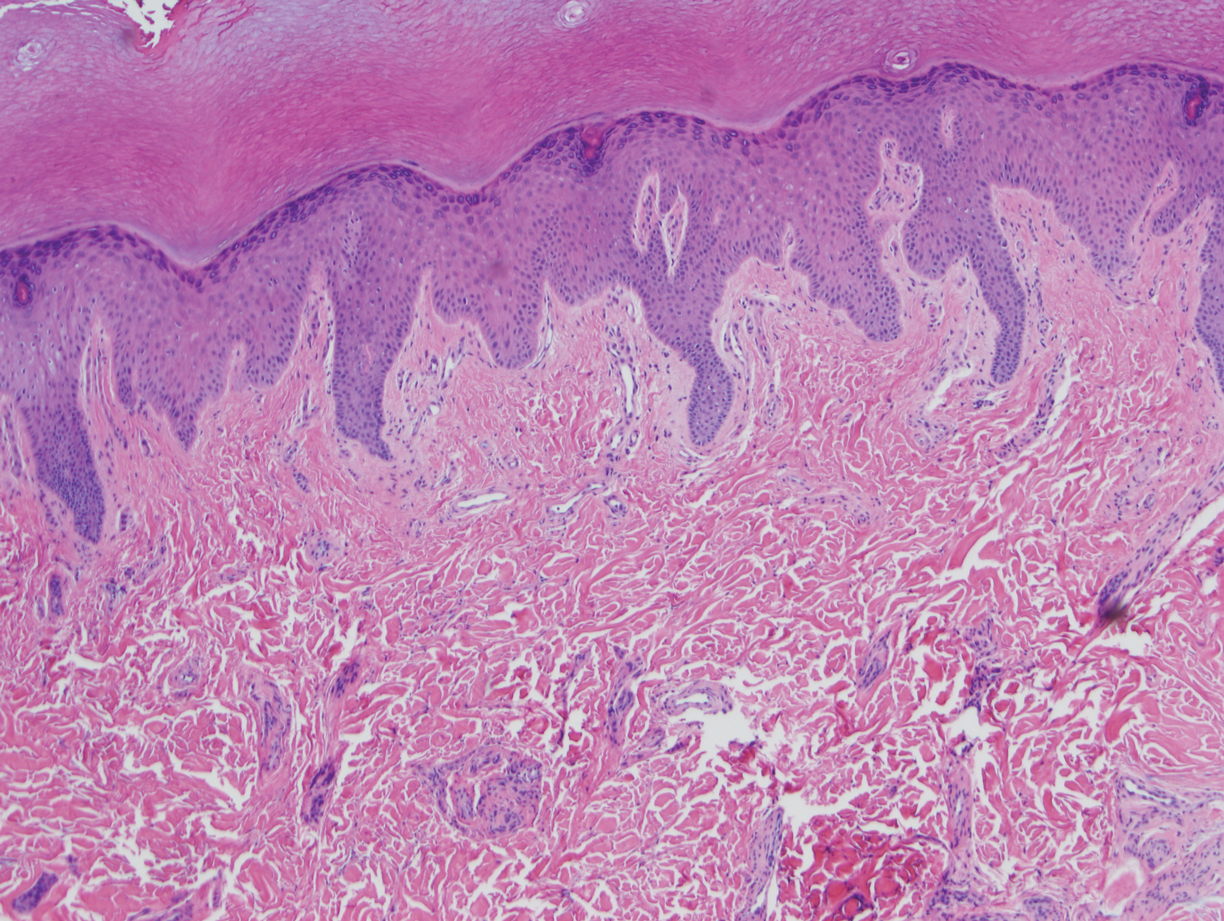

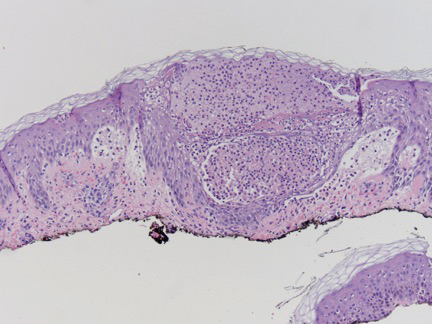

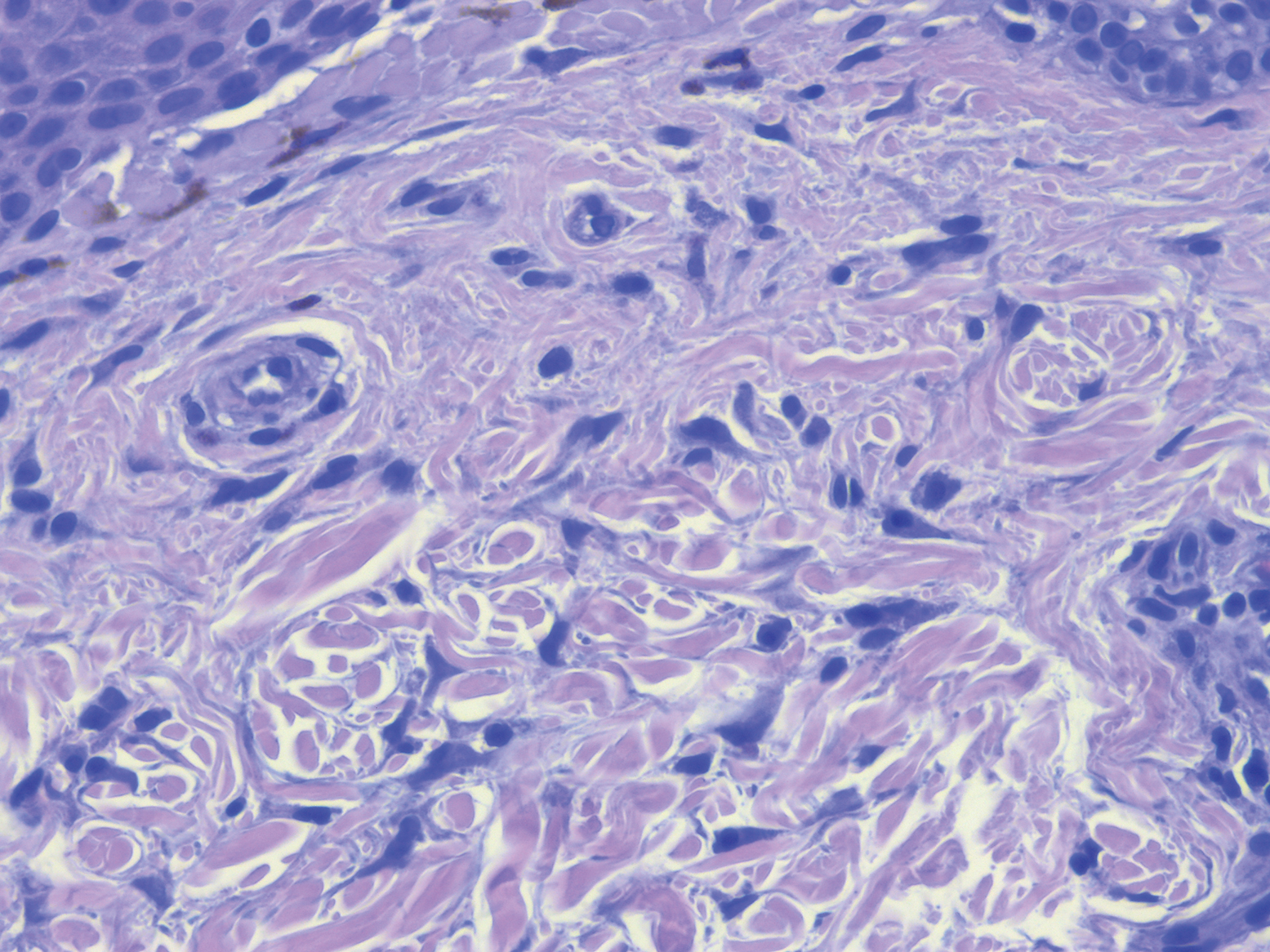

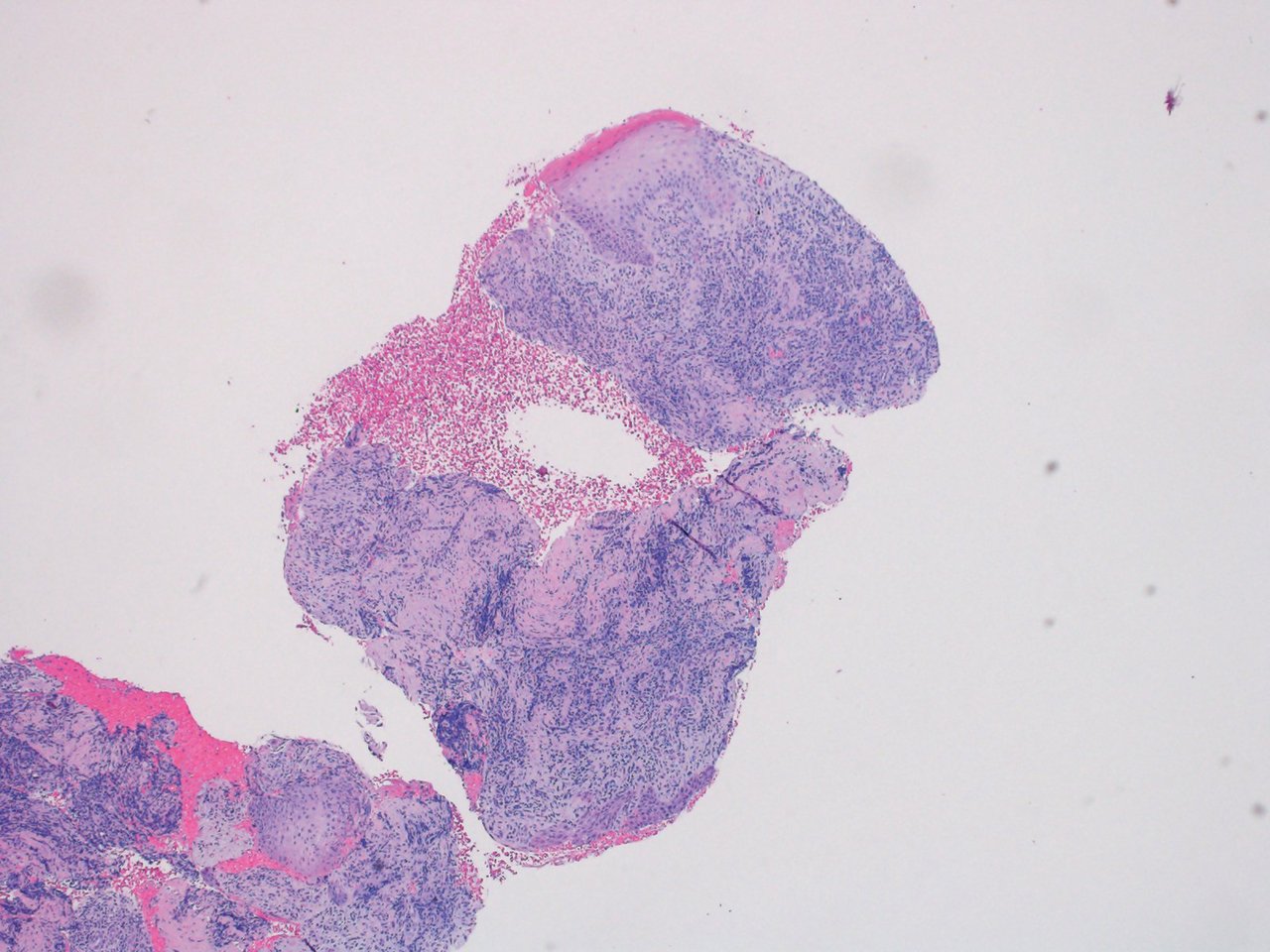

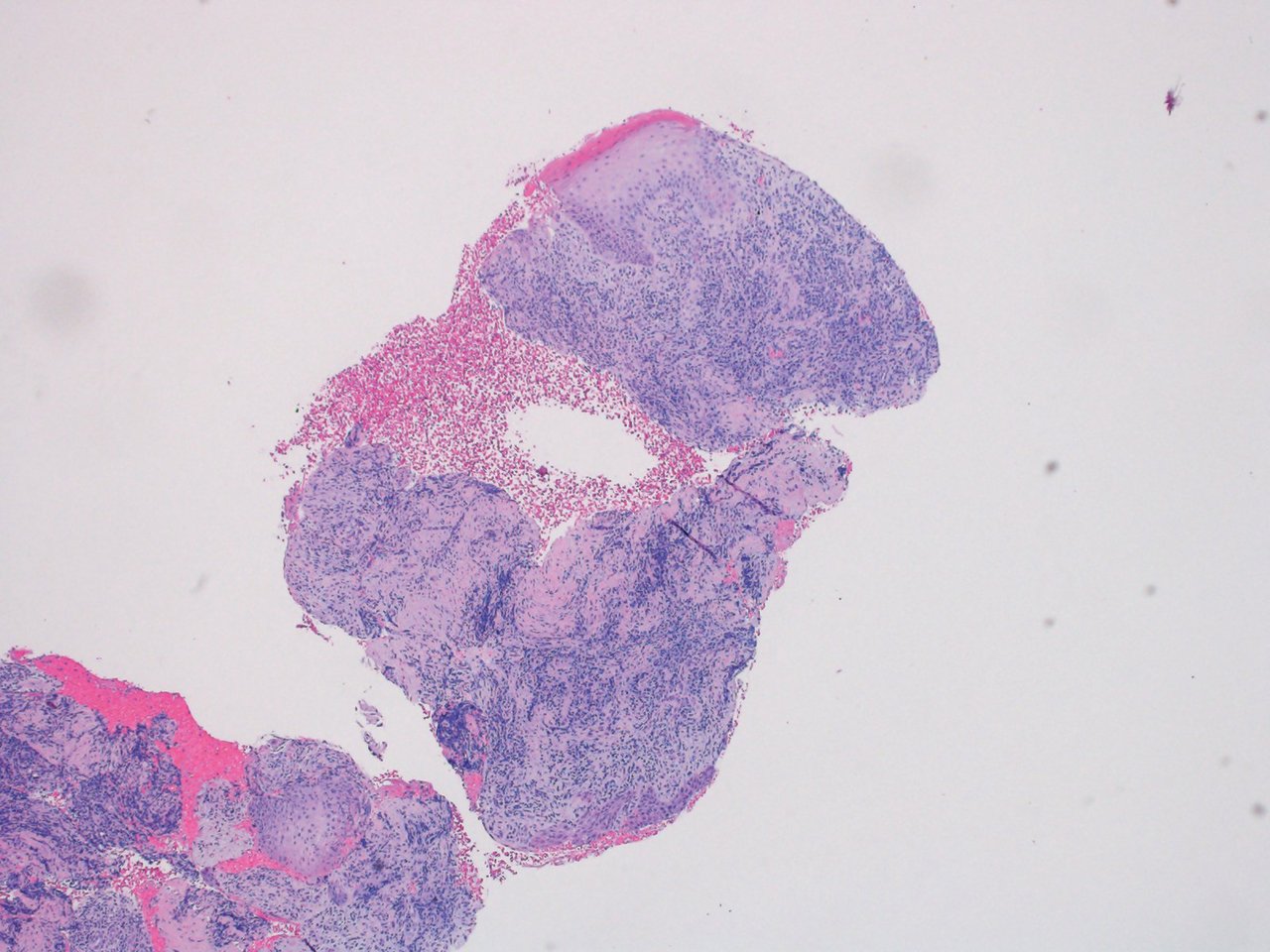

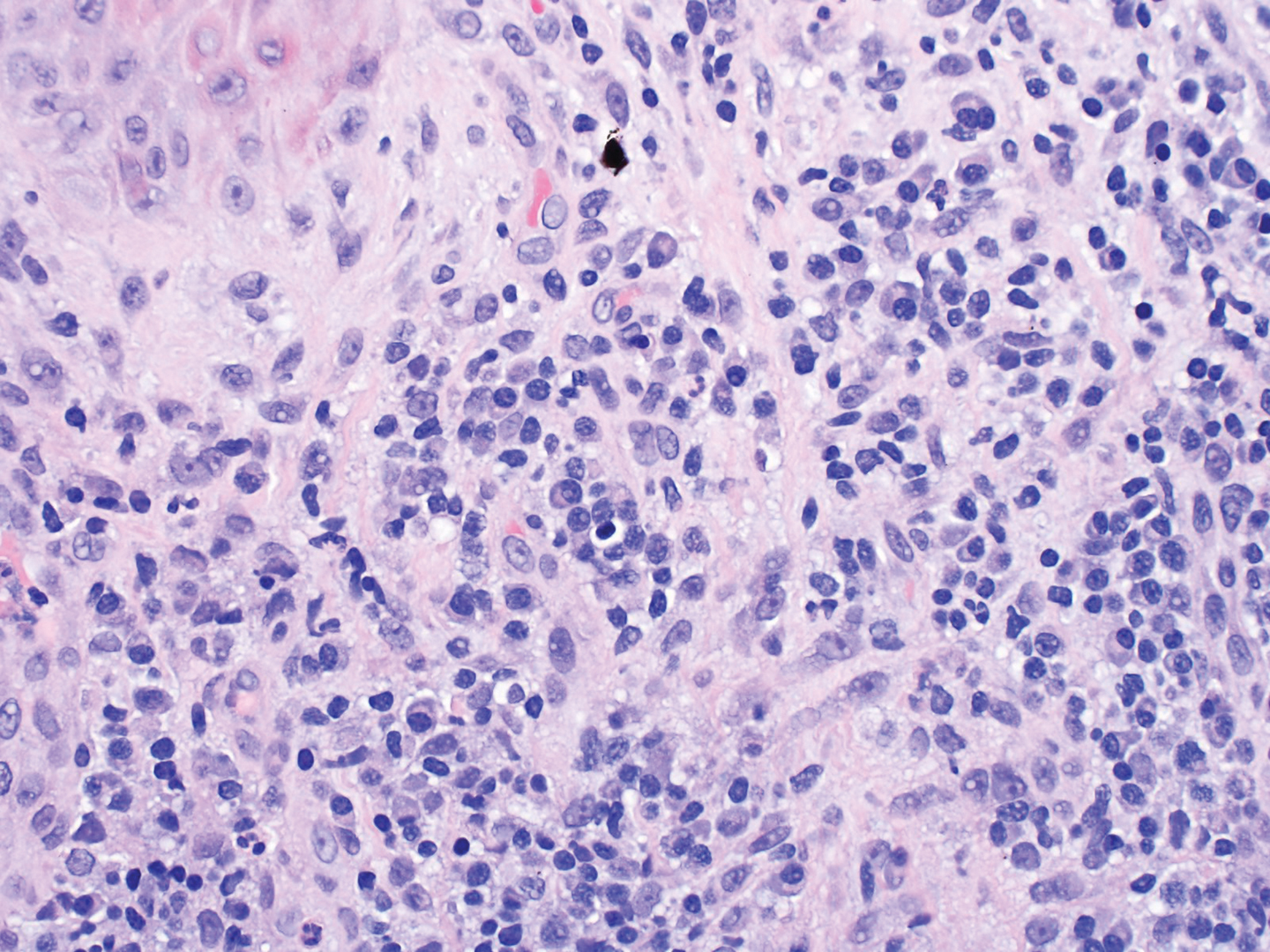

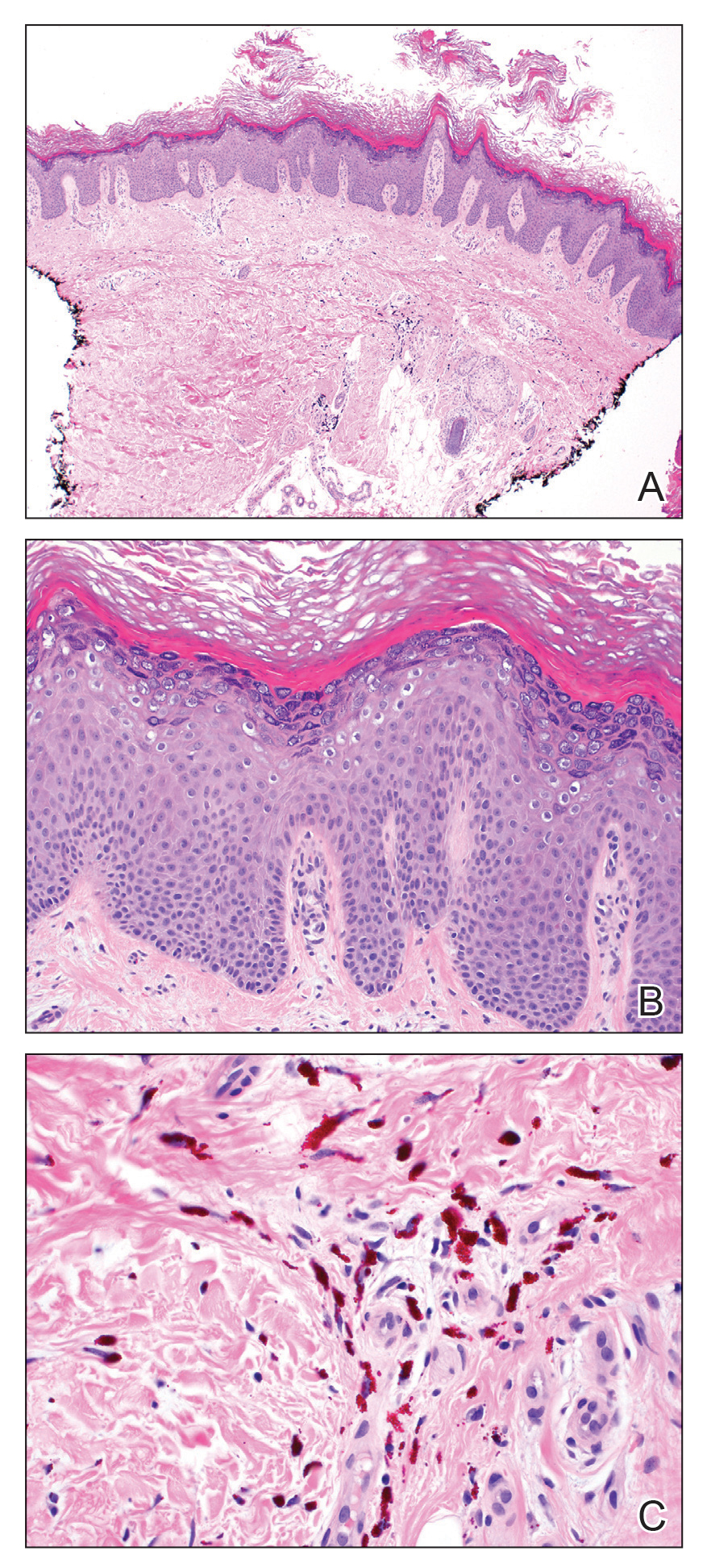

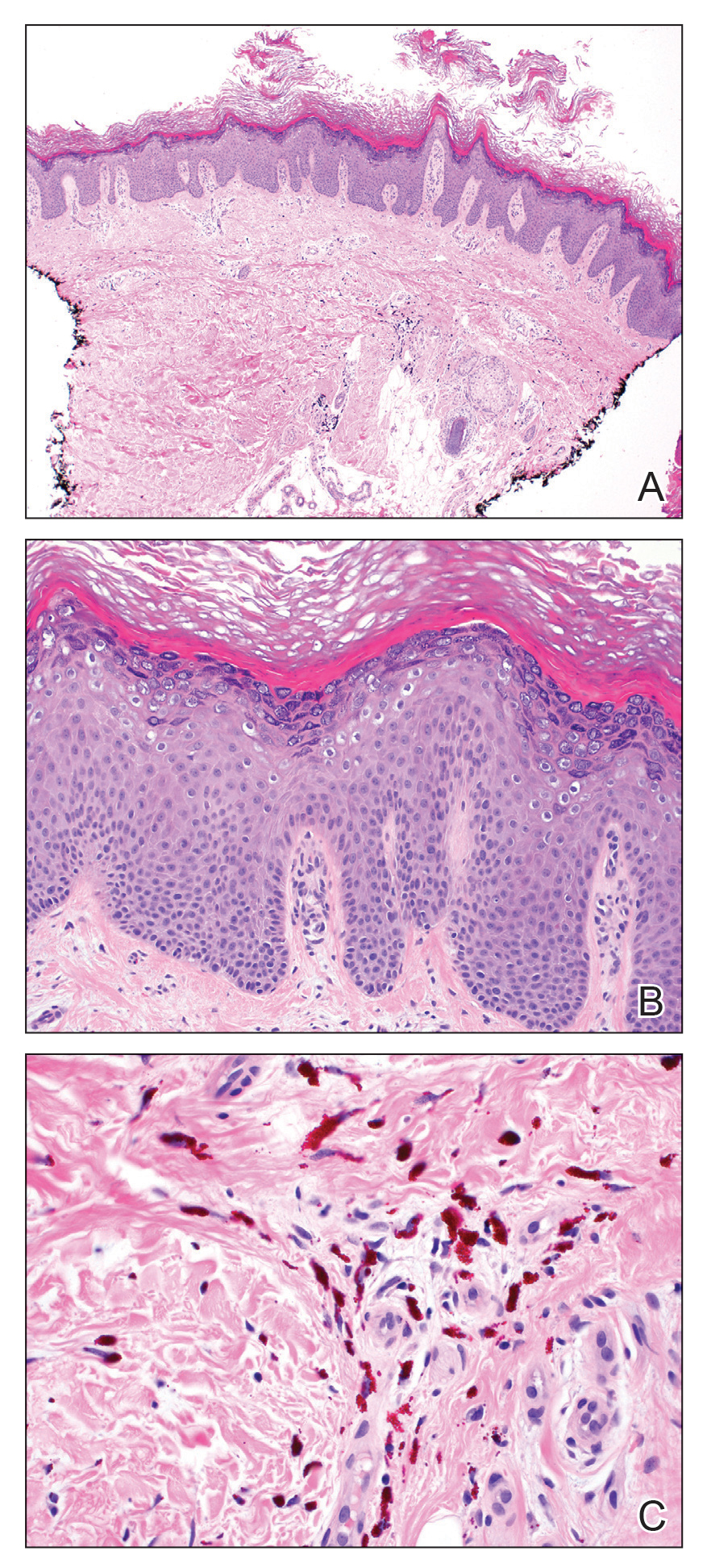

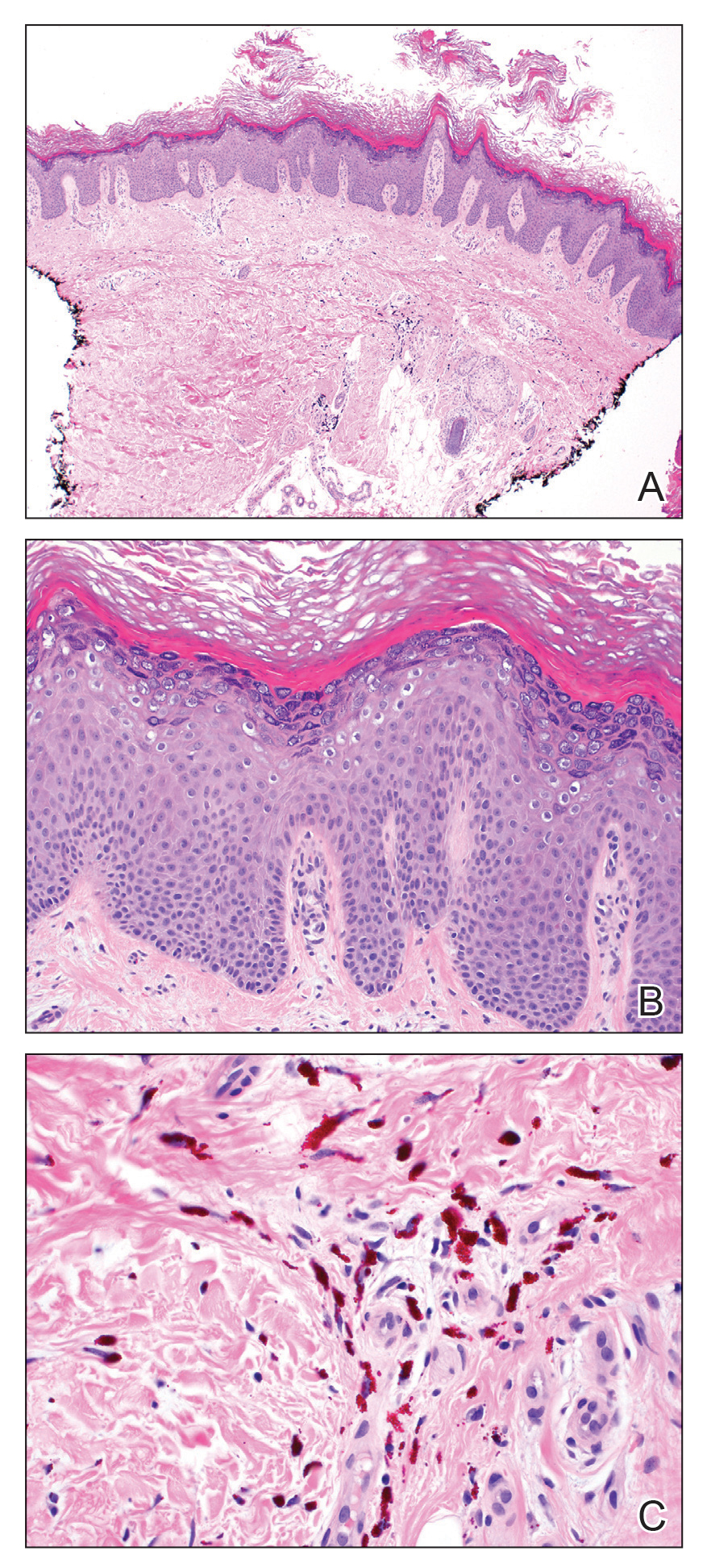

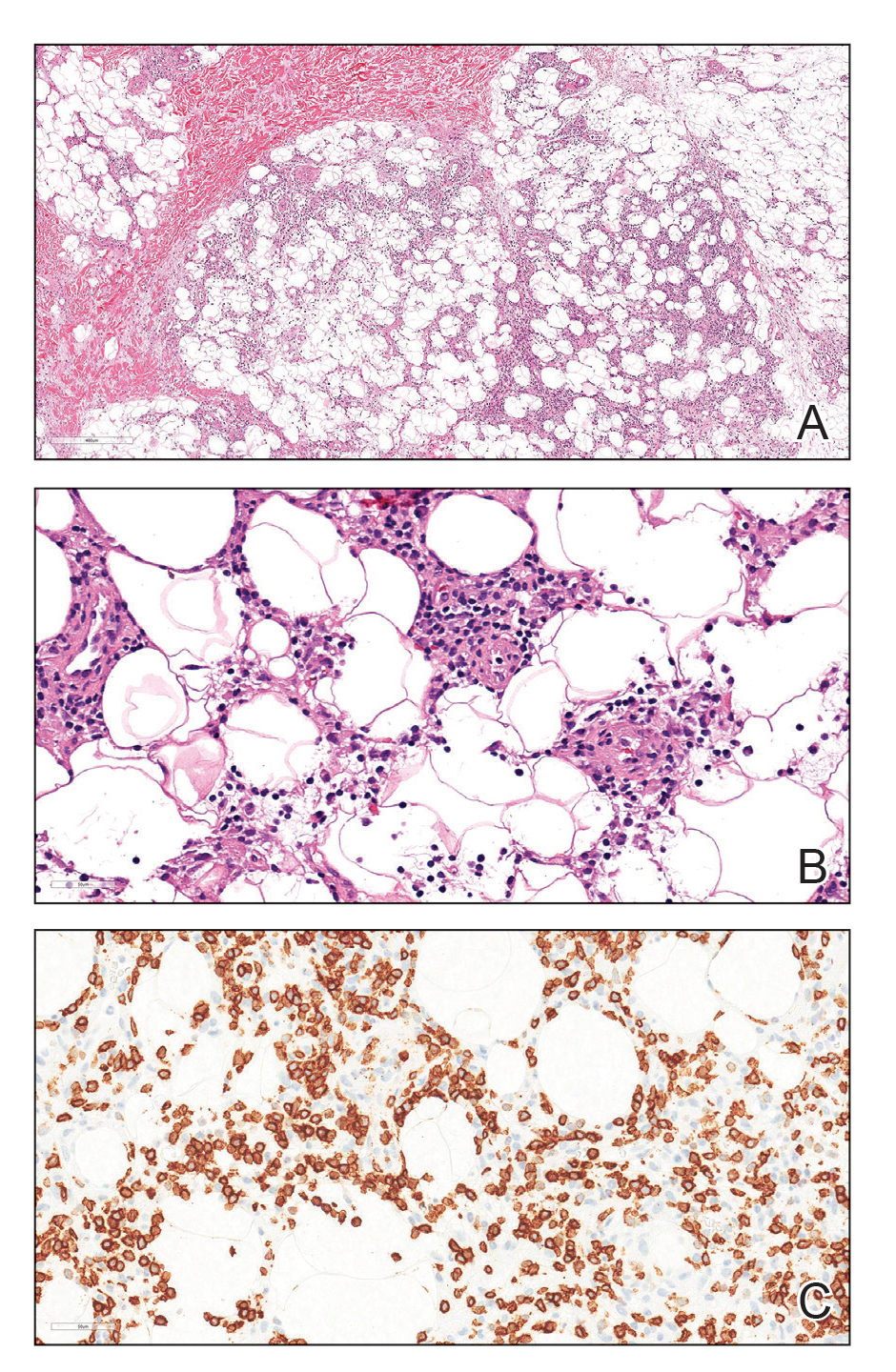

The tissue cultures were negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Microscopic examination of the skin biopsy revealed a moderate perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of predominantly histiocytes and lymphocytes with prominent karyorrhectic debris (nuclear dust) in the upper dermis as well as focal vacuolar interface changes with scattered necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis (Figure 2). Based on these histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was considered. To confirm the diagnosis and to rule out the possibility of lymphoma, an excisional biopsy of the cervical lymph node was performed, which showed typical histopathologic features of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis.

Given the patient’s clinical presentation with arthralgia, anorexia, lymphadenitis, and hepatosplenomegaly along with histopathologic findings from both the skin and lymph node biopsies, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was made. The patient was conservatively managed with acetaminophen and was discharged with improvement in his appetite and systemic symptoms.

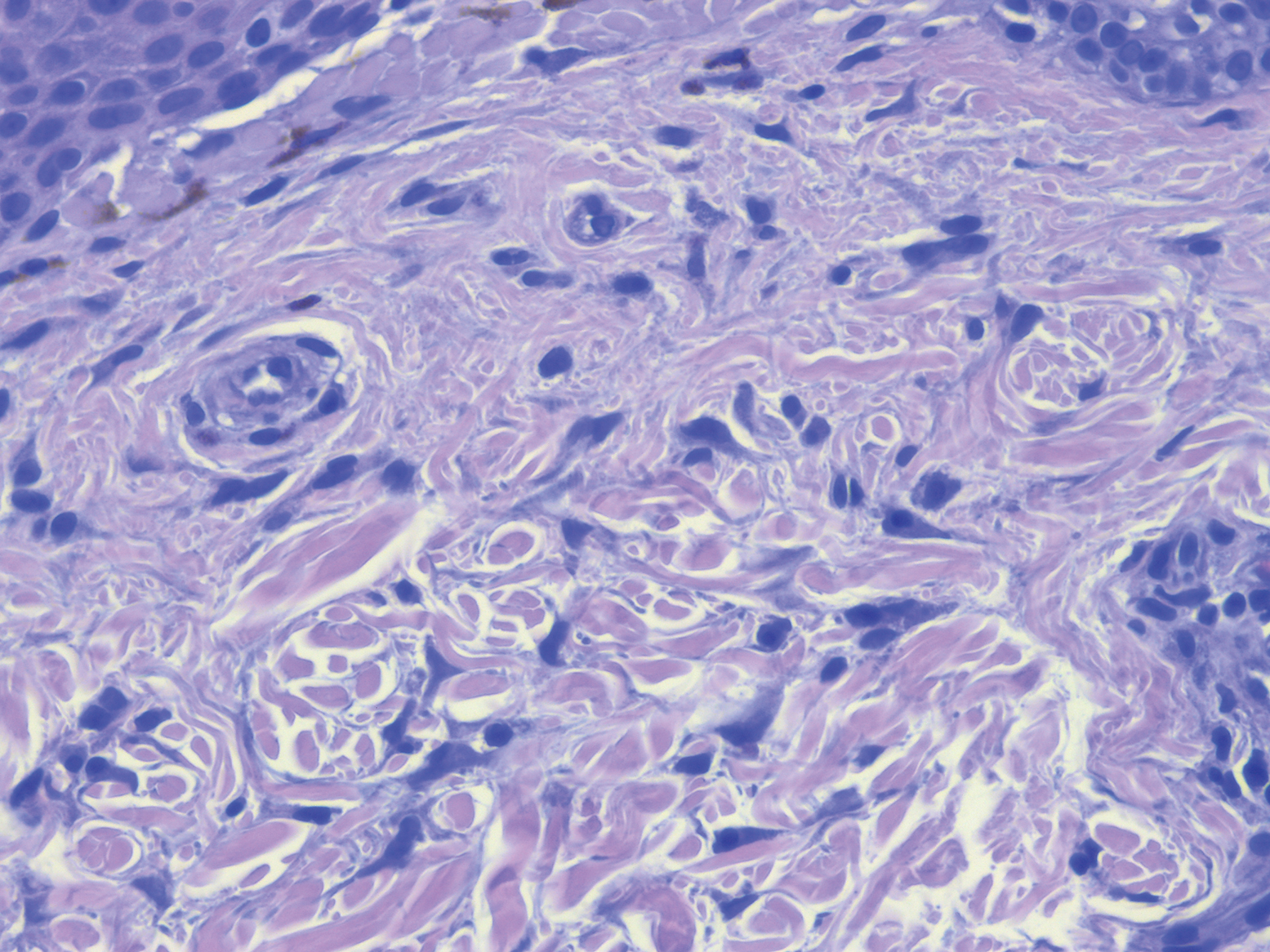

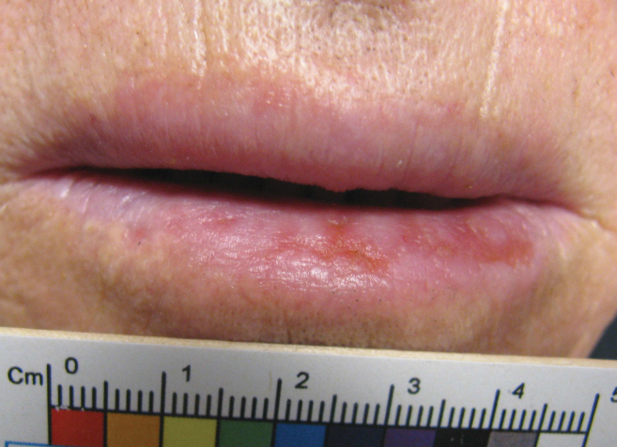

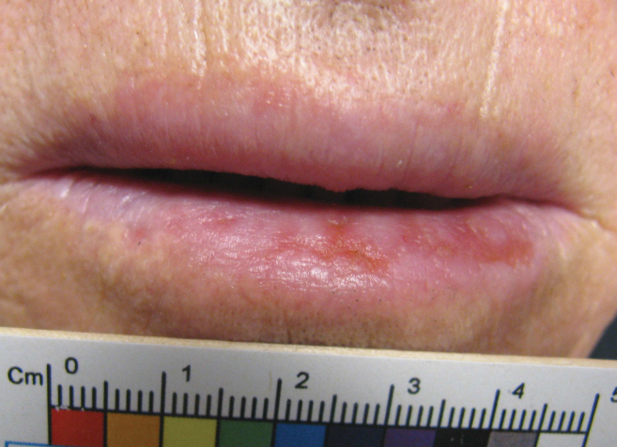

He was seen for follow-up 3 months later in the outpatient clinic. He denied any recurrence of systemic symptoms but endorsed a recent shedding of hair consistent with telogen effluvium. The rash had substantially improved, though residual asymptomatic erythematous plaques remained on the right forehead and right cheek (Figure 3). He was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% to apply to the active area twice daily for the following 2 to 3 weeks.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease presents with a wide clinical spectrum, classically with benign lymphadenopathy and fever of unknown etiology.5,6 Lymphadenopathy most often is cervical (55%–99%)8 and unilateral,4,7 but patients can present with polyadenopathy (52%).7,8 Constitutional signs commonly include fever (35%–76%), weight loss, arthritis (5%–34%), and leukopenia (25%–74%).4,8,9

Cutaneous findings have been described in up to 40% of cases, of which clinical presentation is variable.6 Lesions may include blanchable, erythematous, painful, and/or indurated plaques, nodules, or maculopapules with confluence into patches, urticaria, morbilliform lesions, erythema multiforme, eyelid edema, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, papulopustules, ulcerated gingivae, and mucositis.6,7,10-13 Patients with skin lesions may be at an increased risk for developing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).8 Our patient presented with erythematous scaly plaques with a predominance of lesions in photodistributed locations, which clinically mimicked an underlying connective tissue disease process such as SLE.

Infectious agents such as CMV, parvovirus B19, human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 8 and human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1, HIV, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Toxoplasma have all been implicated as possible causes of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease, but studies have failed to provide convincing causal evidence.9,14,15 Our patient had positive IgM and IgG for CMV, which may have incited his disease.

Definitive diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is made by lymph node excisional biopsy, which histologically exhibits a histiocytic cell proliferation with paracortical foci of necrosis and abundant karyorrhectic debris.5 Cutaneous histologic findings that support the diagnosis are variable and may include a dermal histiocytic infiltrate, epidermal change with necrotic keratinocytes, non-neutrophilic karyorrhectic debris, basal vacuolar change, papillary dermal edema, a nonspecific superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate, and a patchy infiltration of histiocytes and lymphocytes.6,13

Clinical and histopathological features of this disease can mimic other diseases, specifically SLE or lymphoma.7 An association with SLE has been suspected, though it is not well defined and more frequently is associated with cases from Asia than from Europe (28% and 9%, respectively).9 Patients presenting concomitantly with positive ANA, weight loss, arthralgia, and skin lesions are more likely to develop SLE.8 Furthermore, the cutaneous histologic finding of interface change suggests a link between the two diseases. As such, recommendations have been made for ANA screenings and follow-up of patients diagnosed with Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease for clinical evidence of autoimmune disease, particularly SLE.6 Although our patient did not have a positive ANA, his biopsy did demonstrate interface change, and he should be monitored for possible progression of disease in the future.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease differs from lymphoma, as it initially presents with rapid lymph node enlargement as opposed to the gradual enlargement seen in lymphoma. The lymph nodes in Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease often are firm and moveable compared to hard and immobile in lymphoma.3 Excisional lymph node biopsy is necessary for both confirming the diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease and ruling out lymphoma.5

Spontaneous resolution usually occurs in 1 to 4 months.3,6 As such, observation is the most common approach to management. When patients have symptoms that limit activities or cause undue distress such as fevers, joint pains, or abdominal pain, systemic treatment options may be desired. Symptomatic treatment can be managed with a short duration of oral corticosteroids,10,11 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and/or antipyretics.8-15 There are no guidelines regarding systemic steroid regimens, and various treatment schedules have been successful. Systemic therapy was considered for our patient for his weight loss and abdominal pain; however, by the time of discharge the patient was tolerating oral intake and his abdominal pain had improved.

- Kikuchi M. Lymphadenitis showing focal reticulum cell hyperplasia with nuclear debris and phagocytosis. Nippon Ketsueki Gakkai Zasshi. 1972;35:379-380.

- Fujimoto Y, Kojima Y, Yamaguchi K. Cervical subacute necrotizing lymphadenitis: a new clinicopathological entity. Naika. 1972;30:920-927.

- Feder Jr HM, Liu J, Rezuke WN. Kikuchi disease in Connecticut. J Pediatr. 2014;164:196-200.

- Kang HM, Kim JY, Choi EH, et al. Clinical characteristics of severe histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease) in children. J Pediatr. 2016;171:208-212.

- Hutchinson CB, Wang E. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:289-293.

- Atwater AR, Longly BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yen H-R, Lin P-Y, Chuang W-Y, et al. Skin manifestations of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: case report and review. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:210-213.

- Dumas G, Prendki V, Haroche J, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: retrospective study of 91 cases and review of literature. Medicine. 2014;93:372-382.

- Kuc ukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Yasukawa K, Matsumura T, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Kikuchi’s disease and the skin: case report and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:885-889.

- Kaur S, Thami GP, Mohan H, et al. Kikuchi disease with facial rash and erythema multiforme. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:403-405.

- Mauleón C, Valdivielso-Ramos M, Cabeza R, et al. Kikuchi disease with skin lesions mimicking lupus erythematosus. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;3:82-85.

- Obara K, Amoh Y. A case of Kikuchi’s disease (histiocytic necrotizing lymphoadenitis) with histiocytic cutaneous involvement. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1111-1113.

- Rosado FGN, Tang Y-W, Hasserjian RP, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:255-259.

- Chiu CF, Chow KC, Lin TY, et al. Virus infection in patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis in Taiwan. detection of Epstein-Barr virus, type I human T-cell lymphotropic virus, and parvovirus B19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:774-781.

To the Editor:

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease, also called histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, was described in 1972 by both Kikuchi1 and Fujimoto et al.2 Most cases are reported in Asia, with limited reports in the United States.3-5 Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare, self-limiting condition consisting of benign lymphadenopathy and oftentimes fever and systemic symptoms. Lymph node involvement may mimic non-Hodgkin lymphoma or other reactive lymphadenopathy, rendering diagnostic accuracy challenging.5 Cutaneous manifestations are reported in only 16% to 40% of patients.6,7 Herein, we describe the clinical and pathologic features of a case of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease with cutaneous involvement in an adolescent boy.

A 13-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history presented to the pediatric emergency department with cervical lymphadenopathy, weight loss, intermittent fever, and an evolving rash on the face, ears, arms, and thighs of 6 weeks’ duration. The illness began with enlarged lymph nodes and erythematous macules on the face and was diagnosed by his primary care physician as lymphadenitis that was unresponsive to clindamycin. Over the subsequent weeks, the rash worsened, and he developed intermittent fevers, night sweats, abdominal pain, and nausea with a 20-pound weight loss. He presented to the emergency department 3 weeks prior to the current admission and was noted to have elevated cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgM and IgG in addition to lymphopenia and anemia. He was discharged with outpatient follow-up. The rash progressed to involve the face, ears, arms, and thighs. One day prior to the current admission, the patient’s abdominal pain worsened acutely, and he experienced several episodes of emesis. He presented to the pediatric emergency department for further evaluation, and a dermatology consultation was requested at that time.

The patient’s rash was asymptomatic. In addition to the above symptoms, he also noted frequent nosebleeds, gingival bleeding, and diffuse myalgia that was most prominent on the hands and feet; he denied diarrhea, sick contacts, recent travel, or insect bites. His vital signs were normal, and he remained afebrile throughout the hospitalization. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing patient with sunken eyes and dry lips. He had pink, oval, scaly plaques on the cheeks, ears, and arms (Figure 1). The thighs exhibited folliculocentric erythematous papules. The ocular conjunctivae were clear, but white exudative plaques were noted on the tongue. Tender, bilateral, cervical lymphadenopathy and diffuse abdominal tenderness with guarding and hepatosplenomegaly also were present. The fingers and toes were tender upon palpation.

Laboratory workup at admission revealed the following: low white blood cell count, 2700/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL); low hemoglobin, 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL); elevated aspartate aminotransferase, 91 U/L (reference range, 10–30 U/L); and elevated alanine aminotransferase, 118 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase (582 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]), ferritin (1681 ng/mL [reference range, 15–200 ng/mL]), and C-reactive protein (6.0 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]) also were elevated. A respiratory viral panel was unremarkable. Blood cultures were negative, and an HIV 1/2 assay was nonreactive. A chest radiograph demonstrated clear lung fields. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed prominent mesenteric, ileocolic, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

The differential diagnoses at this time included acute connective tissue disease, a paraneoplastic phenomenon, cutaneous lymphoma, or an infectious etiology. A punch biopsy of the skin as well as tissue cultures were performed from a lesion on the right arm. Quantitative immunoglobulin (IgA, IgG, IgM) levels were checked, all of which were within reference range. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) assay and rheumatoid factor were normal.

The tissue cultures were negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Microscopic examination of the skin biopsy revealed a moderate perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of predominantly histiocytes and lymphocytes with prominent karyorrhectic debris (nuclear dust) in the upper dermis as well as focal vacuolar interface changes with scattered necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis (Figure 2). Based on these histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was considered. To confirm the diagnosis and to rule out the possibility of lymphoma, an excisional biopsy of the cervical lymph node was performed, which showed typical histopathologic features of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis.

Given the patient’s clinical presentation with arthralgia, anorexia, lymphadenitis, and hepatosplenomegaly along with histopathologic findings from both the skin and lymph node biopsies, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was made. The patient was conservatively managed with acetaminophen and was discharged with improvement in his appetite and systemic symptoms.

He was seen for follow-up 3 months later in the outpatient clinic. He denied any recurrence of systemic symptoms but endorsed a recent shedding of hair consistent with telogen effluvium. The rash had substantially improved, though residual asymptomatic erythematous plaques remained on the right forehead and right cheek (Figure 3). He was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% to apply to the active area twice daily for the following 2 to 3 weeks.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease presents with a wide clinical spectrum, classically with benign lymphadenopathy and fever of unknown etiology.5,6 Lymphadenopathy most often is cervical (55%–99%)8 and unilateral,4,7 but patients can present with polyadenopathy (52%).7,8 Constitutional signs commonly include fever (35%–76%), weight loss, arthritis (5%–34%), and leukopenia (25%–74%).4,8,9

Cutaneous findings have been described in up to 40% of cases, of which clinical presentation is variable.6 Lesions may include blanchable, erythematous, painful, and/or indurated plaques, nodules, or maculopapules with confluence into patches, urticaria, morbilliform lesions, erythema multiforme, eyelid edema, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, papulopustules, ulcerated gingivae, and mucositis.6,7,10-13 Patients with skin lesions may be at an increased risk for developing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).8 Our patient presented with erythematous scaly plaques with a predominance of lesions in photodistributed locations, which clinically mimicked an underlying connective tissue disease process such as SLE.

Infectious agents such as CMV, parvovirus B19, human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 8 and human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1, HIV, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Toxoplasma have all been implicated as possible causes of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease, but studies have failed to provide convincing causal evidence.9,14,15 Our patient had positive IgM and IgG for CMV, which may have incited his disease.

Definitive diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is made by lymph node excisional biopsy, which histologically exhibits a histiocytic cell proliferation with paracortical foci of necrosis and abundant karyorrhectic debris.5 Cutaneous histologic findings that support the diagnosis are variable and may include a dermal histiocytic infiltrate, epidermal change with necrotic keratinocytes, non-neutrophilic karyorrhectic debris, basal vacuolar change, papillary dermal edema, a nonspecific superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate, and a patchy infiltration of histiocytes and lymphocytes.6,13

Clinical and histopathological features of this disease can mimic other diseases, specifically SLE or lymphoma.7 An association with SLE has been suspected, though it is not well defined and more frequently is associated with cases from Asia than from Europe (28% and 9%, respectively).9 Patients presenting concomitantly with positive ANA, weight loss, arthralgia, and skin lesions are more likely to develop SLE.8 Furthermore, the cutaneous histologic finding of interface change suggests a link between the two diseases. As such, recommendations have been made for ANA screenings and follow-up of patients diagnosed with Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease for clinical evidence of autoimmune disease, particularly SLE.6 Although our patient did not have a positive ANA, his biopsy did demonstrate interface change, and he should be monitored for possible progression of disease in the future.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease differs from lymphoma, as it initially presents with rapid lymph node enlargement as opposed to the gradual enlargement seen in lymphoma. The lymph nodes in Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease often are firm and moveable compared to hard and immobile in lymphoma.3 Excisional lymph node biopsy is necessary for both confirming the diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease and ruling out lymphoma.5

Spontaneous resolution usually occurs in 1 to 4 months.3,6 As such, observation is the most common approach to management. When patients have symptoms that limit activities or cause undue distress such as fevers, joint pains, or abdominal pain, systemic treatment options may be desired. Symptomatic treatment can be managed with a short duration of oral corticosteroids,10,11 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and/or antipyretics.8-15 There are no guidelines regarding systemic steroid regimens, and various treatment schedules have been successful. Systemic therapy was considered for our patient for his weight loss and abdominal pain; however, by the time of discharge the patient was tolerating oral intake and his abdominal pain had improved.

To the Editor:

Kikuchi-Fujimoto Disease, also called histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis, was described in 1972 by both Kikuchi1 and Fujimoto et al.2 Most cases are reported in Asia, with limited reports in the United States.3-5 Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a rare, self-limiting condition consisting of benign lymphadenopathy and oftentimes fever and systemic symptoms. Lymph node involvement may mimic non-Hodgkin lymphoma or other reactive lymphadenopathy, rendering diagnostic accuracy challenging.5 Cutaneous manifestations are reported in only 16% to 40% of patients.6,7 Herein, we describe the clinical and pathologic features of a case of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease with cutaneous involvement in an adolescent boy.

A 13-year-old adolescent boy with no notable medical history presented to the pediatric emergency department with cervical lymphadenopathy, weight loss, intermittent fever, and an evolving rash on the face, ears, arms, and thighs of 6 weeks’ duration. The illness began with enlarged lymph nodes and erythematous macules on the face and was diagnosed by his primary care physician as lymphadenitis that was unresponsive to clindamycin. Over the subsequent weeks, the rash worsened, and he developed intermittent fevers, night sweats, abdominal pain, and nausea with a 20-pound weight loss. He presented to the emergency department 3 weeks prior to the current admission and was noted to have elevated cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgM and IgG in addition to lymphopenia and anemia. He was discharged with outpatient follow-up. The rash progressed to involve the face, ears, arms, and thighs. One day prior to the current admission, the patient’s abdominal pain worsened acutely, and he experienced several episodes of emesis. He presented to the pediatric emergency department for further evaluation, and a dermatology consultation was requested at that time.

The patient’s rash was asymptomatic. In addition to the above symptoms, he also noted frequent nosebleeds, gingival bleeding, and diffuse myalgia that was most prominent on the hands and feet; he denied diarrhea, sick contacts, recent travel, or insect bites. His vital signs were normal, and he remained afebrile throughout the hospitalization. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing patient with sunken eyes and dry lips. He had pink, oval, scaly plaques on the cheeks, ears, and arms (Figure 1). The thighs exhibited folliculocentric erythematous papules. The ocular conjunctivae were clear, but white exudative plaques were noted on the tongue. Tender, bilateral, cervical lymphadenopathy and diffuse abdominal tenderness with guarding and hepatosplenomegaly also were present. The fingers and toes were tender upon palpation.

Laboratory workup at admission revealed the following: low white blood cell count, 2700/μL (reference range, 4500–11,000/μL); low hemoglobin, 9.6 g/dL (reference range, 14.0–17.5 g/dL); elevated aspartate aminotransferase, 91 U/L (reference range, 10–30 U/L); and elevated alanine aminotransferase, 118 U/L (reference range, 10–40 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase (582 U/L [reference range, 100–200 U/L]), ferritin (1681 ng/mL [reference range, 15–200 ng/mL]), and C-reactive protein (6.0 mg/L [reference range, 0.08–3.1 mg/L]) also were elevated. A respiratory viral panel was unremarkable. Blood cultures were negative, and an HIV 1/2 assay was nonreactive. A chest radiograph demonstrated clear lung fields. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed prominent mesenteric, ileocolic, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes.

The differential diagnoses at this time included acute connective tissue disease, a paraneoplastic phenomenon, cutaneous lymphoma, or an infectious etiology. A punch biopsy of the skin as well as tissue cultures were performed from a lesion on the right arm. Quantitative immunoglobulin (IgA, IgG, IgM) levels were checked, all of which were within reference range. An antinuclear antibody (ANA) assay and rheumatoid factor were normal.

The tissue cultures were negative for bacteria, fungi, and mycobacteria. Microscopic examination of the skin biopsy revealed a moderate perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of predominantly histiocytes and lymphocytes with prominent karyorrhectic debris (nuclear dust) in the upper dermis as well as focal vacuolar interface changes with scattered necrotic keratinocytes in the epidermis (Figure 2). Based on these histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was considered. To confirm the diagnosis and to rule out the possibility of lymphoma, an excisional biopsy of the cervical lymph node was performed, which showed typical histopathologic features of histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis.

Given the patient’s clinical presentation with arthralgia, anorexia, lymphadenitis, and hepatosplenomegaly along with histopathologic findings from both the skin and lymph node biopsies, a diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease was made. The patient was conservatively managed with acetaminophen and was discharged with improvement in his appetite and systemic symptoms.

He was seen for follow-up 3 months later in the outpatient clinic. He denied any recurrence of systemic symptoms but endorsed a recent shedding of hair consistent with telogen effluvium. The rash had substantially improved, though residual asymptomatic erythematous plaques remained on the right forehead and right cheek (Figure 3). He was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% to apply to the active area twice daily for the following 2 to 3 weeks.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease presents with a wide clinical spectrum, classically with benign lymphadenopathy and fever of unknown etiology.5,6 Lymphadenopathy most often is cervical (55%–99%)8 and unilateral,4,7 but patients can present with polyadenopathy (52%).7,8 Constitutional signs commonly include fever (35%–76%), weight loss, arthritis (5%–34%), and leukopenia (25%–74%).4,8,9

Cutaneous findings have been described in up to 40% of cases, of which clinical presentation is variable.6 Lesions may include blanchable, erythematous, painful, and/or indurated plaques, nodules, or maculopapules with confluence into patches, urticaria, morbilliform lesions, erythema multiforme, eyelid edema, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, papulopustules, ulcerated gingivae, and mucositis.6,7,10-13 Patients with skin lesions may be at an increased risk for developing systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).8 Our patient presented with erythematous scaly plaques with a predominance of lesions in photodistributed locations, which clinically mimicked an underlying connective tissue disease process such as SLE.

Infectious agents such as CMV, parvovirus B19, human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 8 and human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1, HIV, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Toxoplasma have all been implicated as possible causes of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease, but studies have failed to provide convincing causal evidence.9,14,15 Our patient had positive IgM and IgG for CMV, which may have incited his disease.

Definitive diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is made by lymph node excisional biopsy, which histologically exhibits a histiocytic cell proliferation with paracortical foci of necrosis and abundant karyorrhectic debris.5 Cutaneous histologic findings that support the diagnosis are variable and may include a dermal histiocytic infiltrate, epidermal change with necrotic keratinocytes, non-neutrophilic karyorrhectic debris, basal vacuolar change, papillary dermal edema, a nonspecific superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate, and a patchy infiltration of histiocytes and lymphocytes.6,13

Clinical and histopathological features of this disease can mimic other diseases, specifically SLE or lymphoma.7 An association with SLE has been suspected, though it is not well defined and more frequently is associated with cases from Asia than from Europe (28% and 9%, respectively).9 Patients presenting concomitantly with positive ANA, weight loss, arthralgia, and skin lesions are more likely to develop SLE.8 Furthermore, the cutaneous histologic finding of interface change suggests a link between the two diseases. As such, recommendations have been made for ANA screenings and follow-up of patients diagnosed with Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease for clinical evidence of autoimmune disease, particularly SLE.6 Although our patient did not have a positive ANA, his biopsy did demonstrate interface change, and he should be monitored for possible progression of disease in the future.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease differs from lymphoma, as it initially presents with rapid lymph node enlargement as opposed to the gradual enlargement seen in lymphoma. The lymph nodes in Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease often are firm and moveable compared to hard and immobile in lymphoma.3 Excisional lymph node biopsy is necessary for both confirming the diagnosis of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease and ruling out lymphoma.5

Spontaneous resolution usually occurs in 1 to 4 months.3,6 As such, observation is the most common approach to management. When patients have symptoms that limit activities or cause undue distress such as fevers, joint pains, or abdominal pain, systemic treatment options may be desired. Symptomatic treatment can be managed with a short duration of oral corticosteroids,10,11 nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and/or antipyretics.8-15 There are no guidelines regarding systemic steroid regimens, and various treatment schedules have been successful. Systemic therapy was considered for our patient for his weight loss and abdominal pain; however, by the time of discharge the patient was tolerating oral intake and his abdominal pain had improved.

- Kikuchi M. Lymphadenitis showing focal reticulum cell hyperplasia with nuclear debris and phagocytosis. Nippon Ketsueki Gakkai Zasshi. 1972;35:379-380.

- Fujimoto Y, Kojima Y, Yamaguchi K. Cervical subacute necrotizing lymphadenitis: a new clinicopathological entity. Naika. 1972;30:920-927.

- Feder Jr HM, Liu J, Rezuke WN. Kikuchi disease in Connecticut. J Pediatr. 2014;164:196-200.

- Kang HM, Kim JY, Choi EH, et al. Clinical characteristics of severe histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease) in children. J Pediatr. 2016;171:208-212.

- Hutchinson CB, Wang E. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:289-293.

- Atwater AR, Longly BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yen H-R, Lin P-Y, Chuang W-Y, et al. Skin manifestations of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: case report and review. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:210-213.

- Dumas G, Prendki V, Haroche J, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: retrospective study of 91 cases and review of literature. Medicine. 2014;93:372-382.

- Kuc ukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Yasukawa K, Matsumura T, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Kikuchi’s disease and the skin: case report and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:885-889.

- Kaur S, Thami GP, Mohan H, et al. Kikuchi disease with facial rash and erythema multiforme. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:403-405.

- Mauleón C, Valdivielso-Ramos M, Cabeza R, et al. Kikuchi disease with skin lesions mimicking lupus erythematosus. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;3:82-85.

- Obara K, Amoh Y. A case of Kikuchi’s disease (histiocytic necrotizing lymphoadenitis) with histiocytic cutaneous involvement. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1111-1113.

- Rosado FGN, Tang Y-W, Hasserjian RP, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:255-259.

- Chiu CF, Chow KC, Lin TY, et al. Virus infection in patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis in Taiwan. detection of Epstein-Barr virus, type I human T-cell lymphotropic virus, and parvovirus B19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:774-781.

- Kikuchi M. Lymphadenitis showing focal reticulum cell hyperplasia with nuclear debris and phagocytosis. Nippon Ketsueki Gakkai Zasshi. 1972;35:379-380.

- Fujimoto Y, Kojima Y, Yamaguchi K. Cervical subacute necrotizing lymphadenitis: a new clinicopathological entity. Naika. 1972;30:920-927.

- Feder Jr HM, Liu J, Rezuke WN. Kikuchi disease in Connecticut. J Pediatr. 2014;164:196-200.

- Kang HM, Kim JY, Choi EH, et al. Clinical characteristics of severe histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis (Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease) in children. J Pediatr. 2016;171:208-212.

- Hutchinson CB, Wang E. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:289-293.

- Atwater AR, Longly BJ, Aughenbaugh WD. Kikuchi’s disease: case report and systematic review of cutaneous and histopathologic presentations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:130-136.

- Yen H-R, Lin P-Y, Chuang W-Y, et al. Skin manifestations of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: case report and review. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:210-213.

- Dumas G, Prendki V, Haroche J, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: retrospective study of 91 cases and review of literature. Medicine. 2014;93:372-382.

- Kuc ukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:50-54.

- Yasukawa K, Matsumura T, Sato-Matsumura KC, et al. Kikuchi’s disease and the skin: case report and review of the literature. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:885-889.

- Kaur S, Thami GP, Mohan H, et al. Kikuchi disease with facial rash and erythema multiforme. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001;18:403-405.

- Mauleón C, Valdivielso-Ramos M, Cabeza R, et al. Kikuchi disease with skin lesions mimicking lupus erythematosus. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;3:82-85.

- Obara K, Amoh Y. A case of Kikuchi’s disease (histiocytic necrotizing lymphoadenitis) with histiocytic cutaneous involvement. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1111-1113.

- Rosado FGN, Tang Y-W, Hasserjian RP, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto lymphadenitis: role of parvovirus B-19, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6, and human herpesvirus 8. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:255-259.

- Chiu CF, Chow KC, Lin TY, et al. Virus infection in patients with histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis in Taiwan. detection of Epstein-Barr virus, type I human T-cell lymphotropic virus, and parvovirus B19. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:774-781.

Practice Points

- Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is an uncommon, self-limited condition characterized by benign lymphadenopathy and variable systemic symptoms.

- Definitive diagnosis is made by excisional lymph node biopsy.

- Treatment options include oral corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and/or antipyretics.

Botulinum Toxin for the Treatment of Intractable Raynaud Phenomenon

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is an episodic vasospasm of the digits that can lead to ulceration, gangrene, and autoamputation with prolonged ischemia. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP by paralyzing the muscles of the digital arteries. We report a case of a woman with severe RP secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections after multiple treatment modalities failed to improve her condition. We describe the dosage and injection technique used to produce clinical improvement in our patient and compare it to prior reports in the literature.

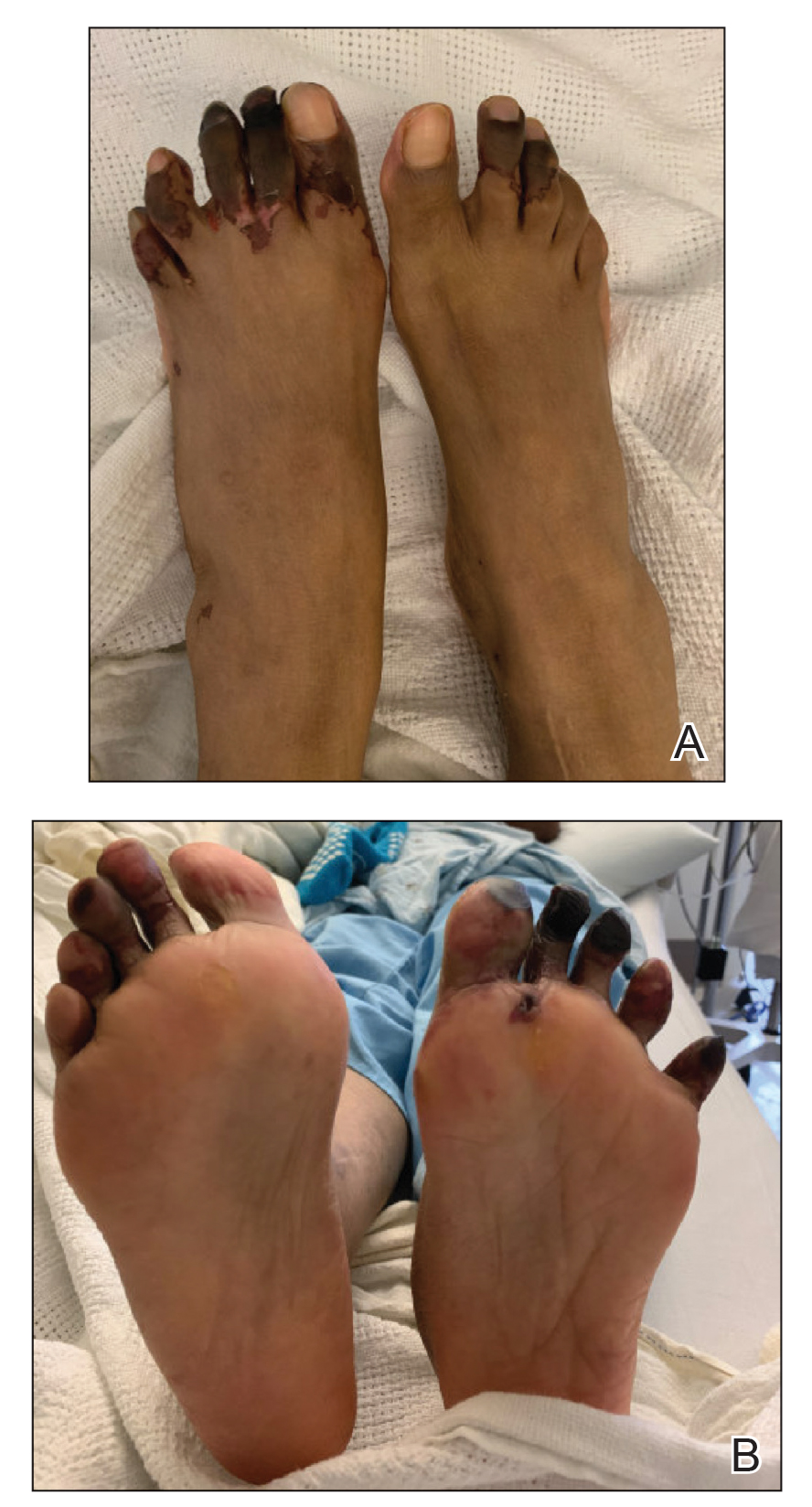

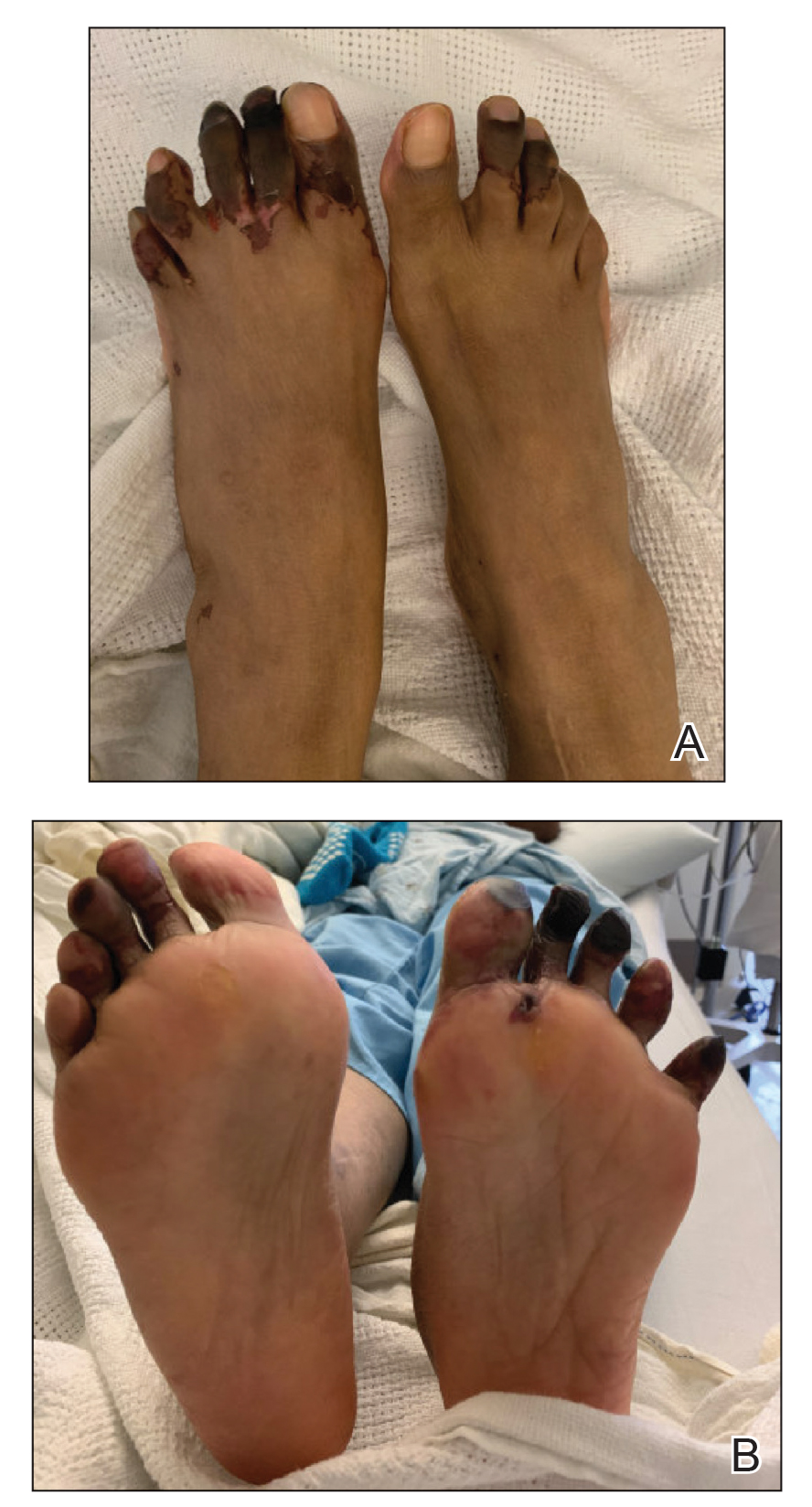

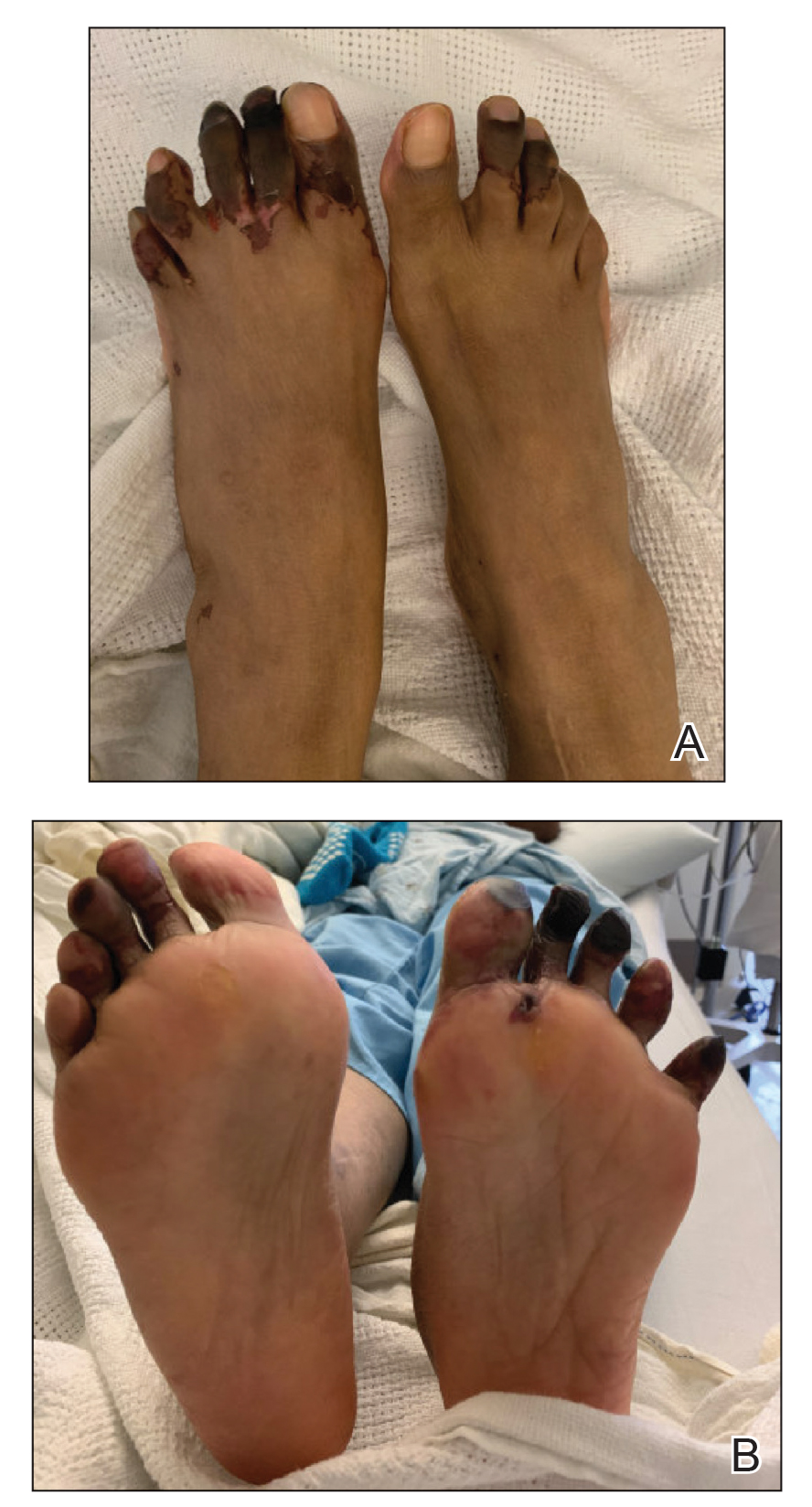

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for worsening foot pain of 5 days' duration with dusky purple color changes concerning for impending Raynaud crisis related to RP. The patient had a history of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) and SLE with overlapping symptoms of polymyositis and scleroderma. She had been hospitalized for RP multiple times prior to the current admission. She was medically managed with nifedipine, sildenafil, losartan potassium, aspirin, alprostadil, and prostaglandin infusions, and was surgically managed with a right-hand sympathectomy and right ulnar artery bypass graft that had subsequently thrombosed. At the current presentation, she had painful dusky toes on both feet though more pronounced on the left foot. She endorsed foot pain while walking and tenderness to palpation of the fingers, which were minimally improved with intravenous prostaglandins.

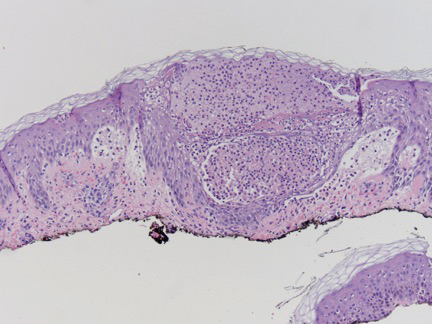

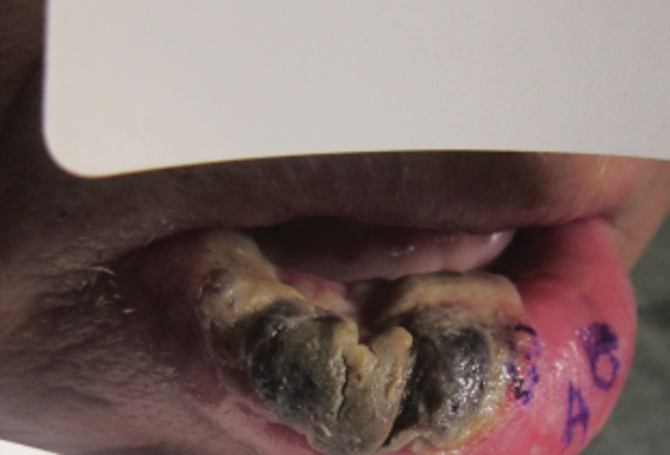

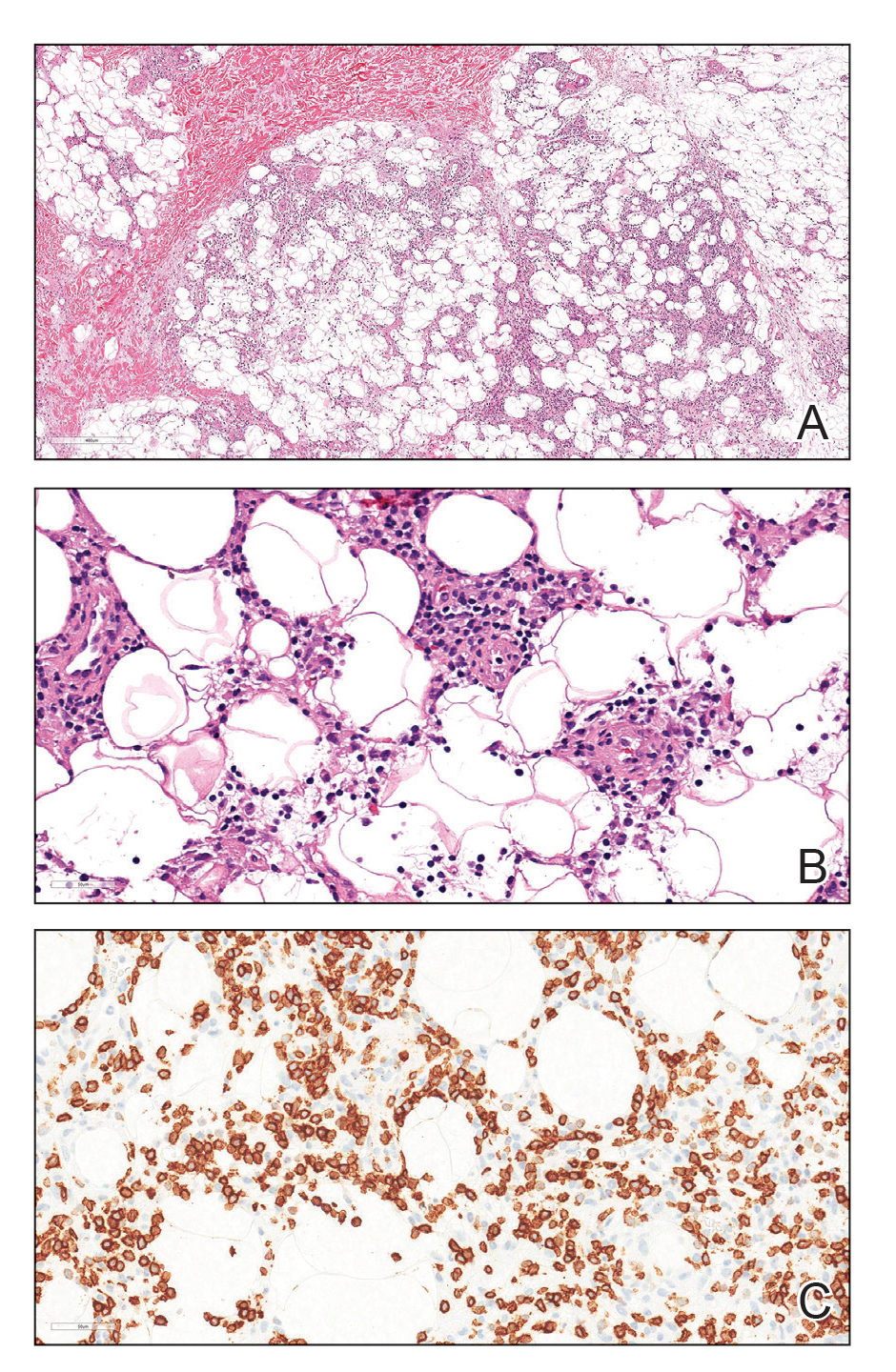

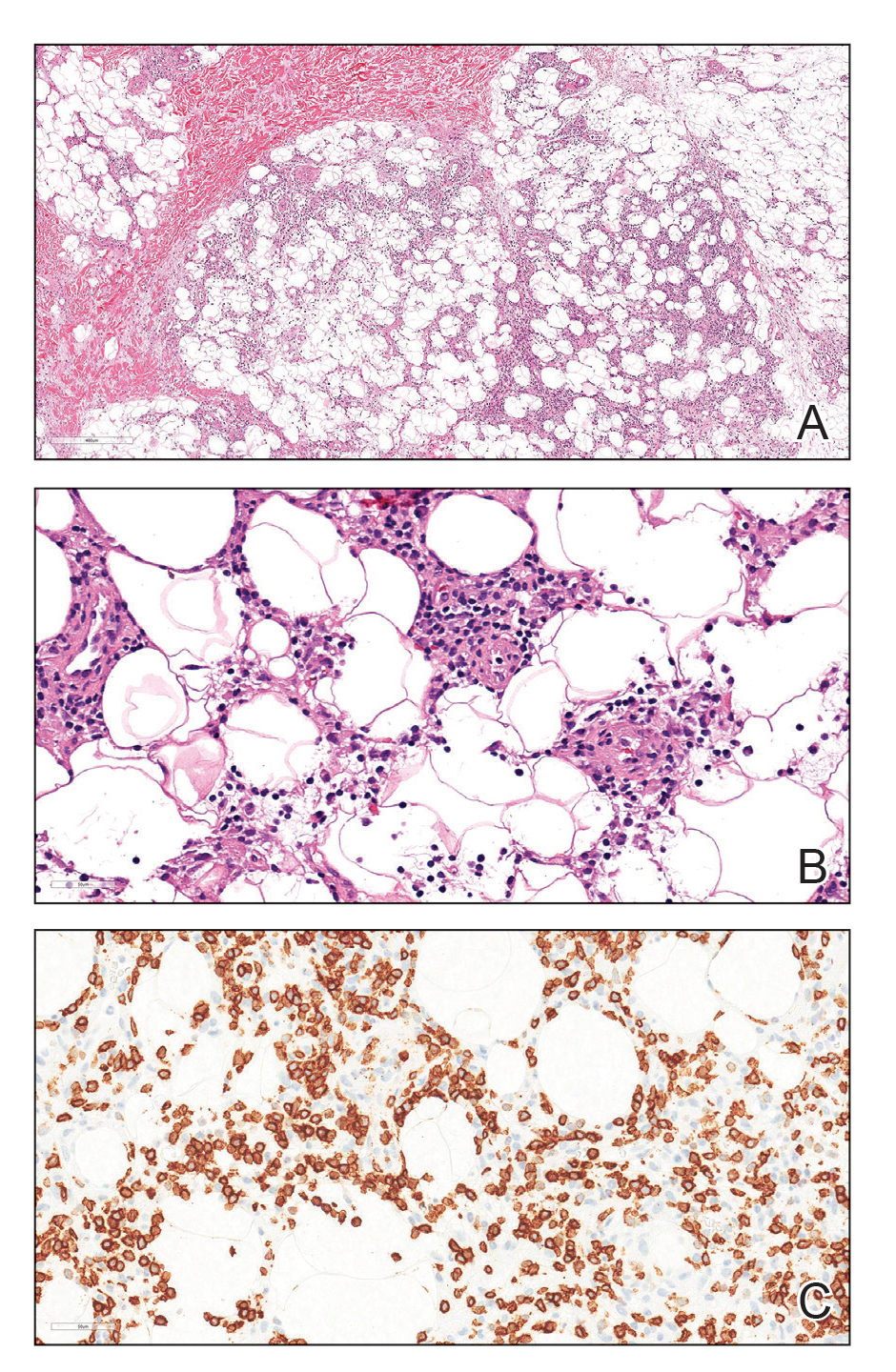

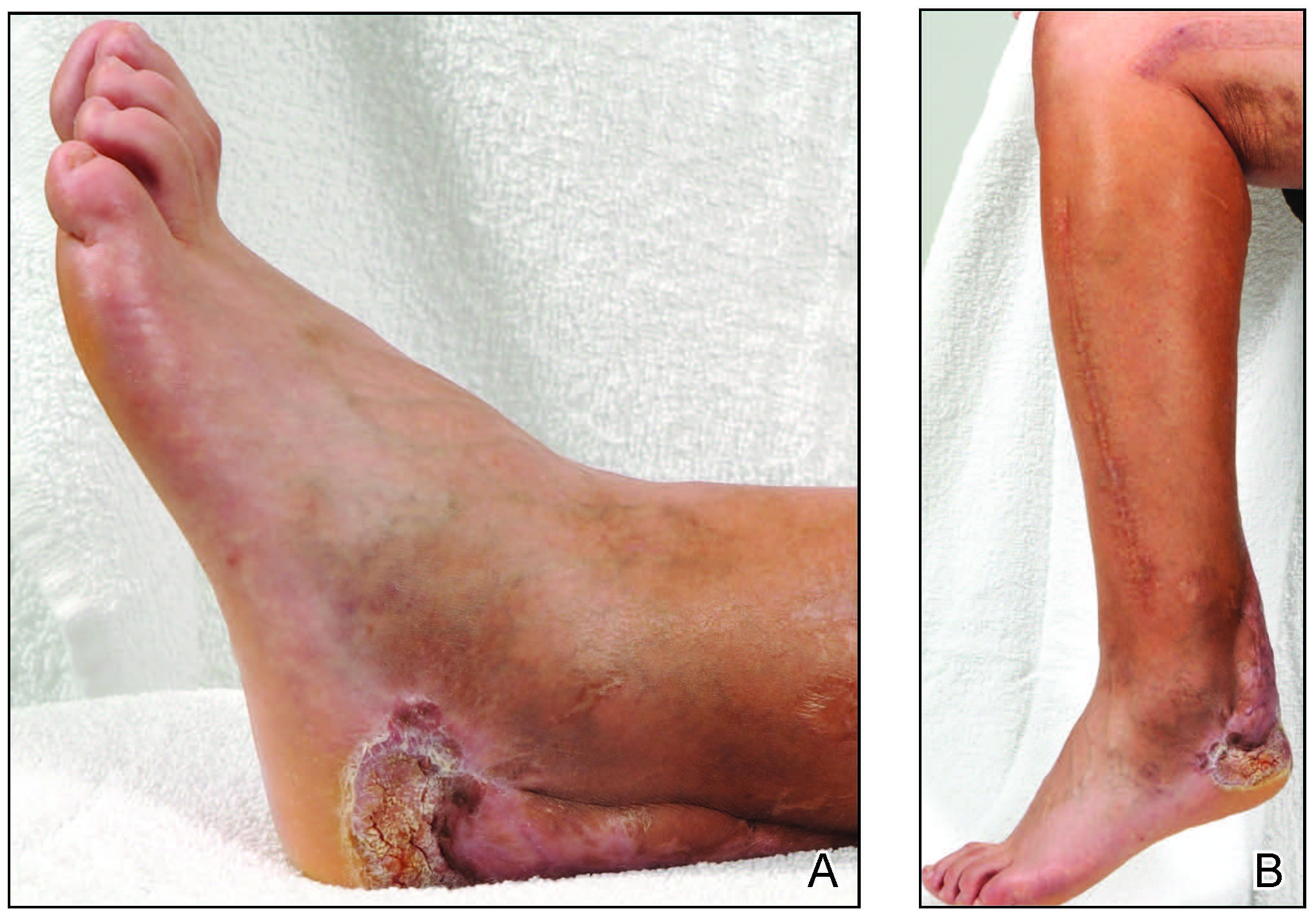

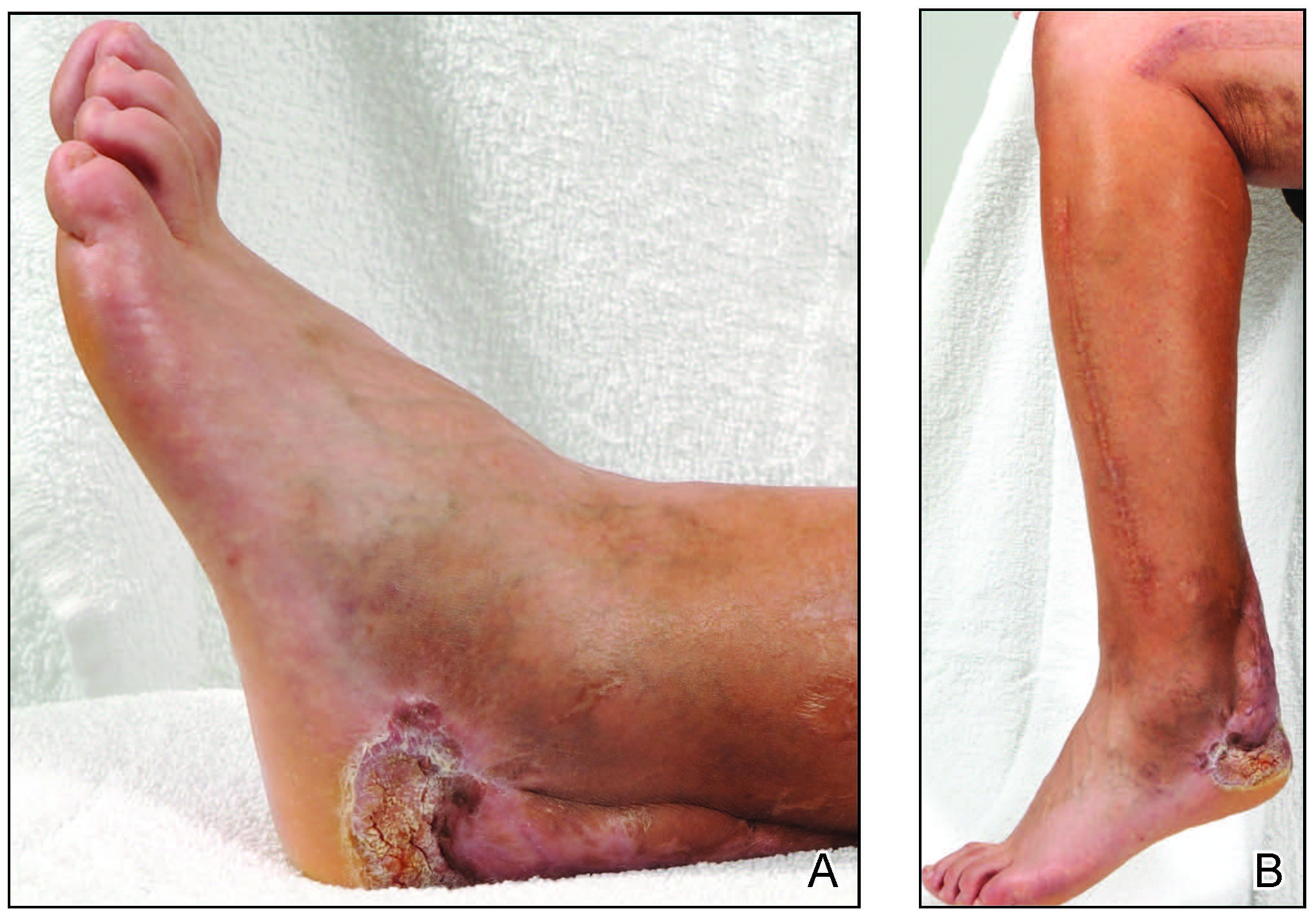

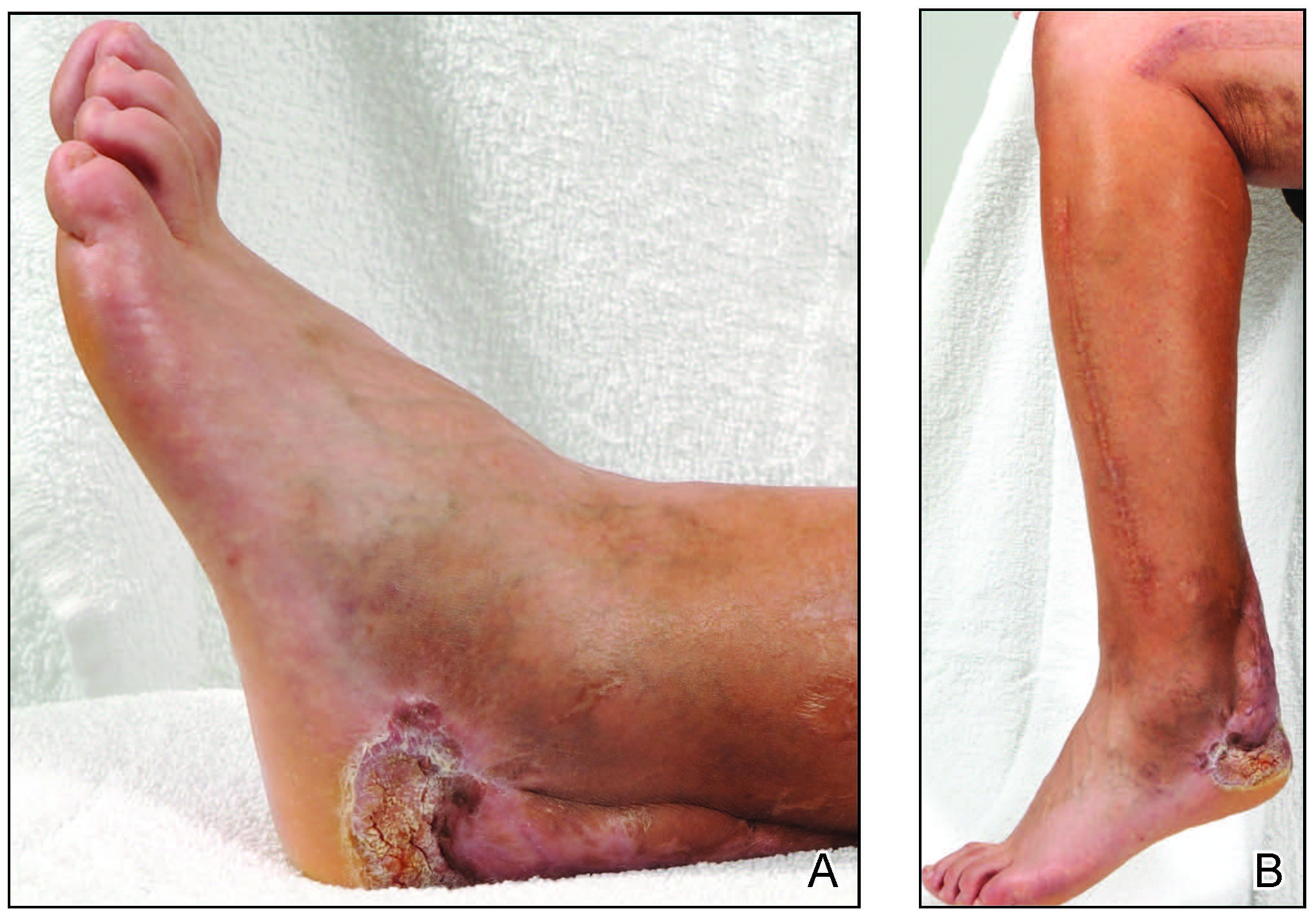

Physical examination revealed blanching of the digits in both hands with pits in the right fourth and left first digits. Dusky patches overlaid all the toes as well as the superior plantar aspects of the feet (Figure 1). Given the history of APS, a punch biopsy was performed on the left medial plantar foot and results showed no histologic evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy. Necrotic foci were present on the left and right second metatarsal bones, which were not reperfusable (Figure 2). The clinical findings and punch biopsy results favored RP as opposed to vasculopathy from APS.

Several interventions were attempted, and after 4 days with no response, the patient agreed to receive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. OnabotulinumtoxinA (5 U) was injected into the subcutaneous tissue of the medial and lateral aspects of each of the first and second toes near the proximal phalanges (40 U total). However, treatment could not be completed due to severe pain caused by the injections despite preprocedure regional nerve blocks to both lower extremities, preinjection icing, and lorazepam. Two days later, the patient tolerated onabotulinumtoxinA injections of all remaining digits of both feet (60 U total). She noted slight clinical improvement soon thereafter. One week after treatment of all 10 toes, she reported decreased pain and reduced duskiness of both feet (Figure 3).

One month later, the patient endorsed recurring pain in the hands and feet. Physical examination revealed reticular cyanosis and increased violaceous patches of the hands; the feet were overall unchanged from the prior hospitalization. At 4-month follow-up, there was gangrene on the left second, third, and fifth toe in addition to areas of induration noted on the fingers. She was repeatedly hospitalized over the next 6 months for pain management and gangrene of the toes, and finally underwent an amputation of the left and right second toe at the proximal and middle phalanx, respectively. She currently is continuing extensive medical management for pain and gangrene of the digits; she has not received additional onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Raynaud phenomenon is a vascular disorder characterized by intermittent arteriolar vasospasm of the digits, often due to cold temperature or stress. Approximately 90% of RP cases are primarily idiopathic, with the remaining cases secondary to other diseases, typically systemic sclerosis, SLE, or mixed connective tissue disease.1 Symptoms present with characteristic changing of hands from white (ischemia) to blue (hypoxia) to red (reperfusion). Episodic attacks of vasospasm and ischemia can be painful and lead to digital ulcerations and necrosis of the digits or hands. Other complications including digital tuft pits, pterygium inversum unguis, or torturous nail fold capillaries with capillary dropout also may be seen.2

Although the etiology is multifactorial, the pathophysiology primarily is due to an imbalance of vasodilation and vasoconstriction. Perturbed levels of vasodilatory mediators include nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and calcitonin gene-related peptide.3 Meanwhile, abnormal neural sympathetic control of α-adrenergic receptors located on smooth muscle vasculature and subsequent endothelial hyperproliferation may contribute to inappropriate vasoconstriction.4

The first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease refractory to conservative management includes monotherapy with dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. For severe disease, combination therapy involves addition of other classes of medications including phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, topical nitrates, angiotensin receptor blockers, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Intravenous prostacyclin, endothelin receptor blockers, and onabotulinumtoxinA injections may be added as third-line therapy. Finally, surgical management including sympathectomy with continued pharmacologic therapy may be needed for disease recalcitrant to the aforementioned options.2

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. The toxin’s mechanism of action involves inhibition of the release of presynaptic acetylcholine-containing vesicles at the neuromuscular junction through cleavage of sensory nerve action potential receptor proteins. In addition, it inhibits smooth muscle vasoconstriction and pain by blocking α2-adrenergic receptors on blood vessels and chronic pain-transmitting C fibers in nerves, respectively.3,5

Only recently has onabotulinumtoxinA been used for treatment of RP. Botulinum toxin is approved for the treatment of spastic and dystonic diseases such as blepharospasm, headaches in patients with chronic migraines, upper limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, torticollis, ocular strabismus, and hyperhidrosis.3 However, the versatility of its therapeutic effects is evident in its broad off-label clinical applications, including achalasia; carpal tunnel syndrome; and spasticity relating to stroke, paraplegia, and cerebral palsy, among many others.5

Few studies have analyzed the use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of RP.3,6 There is no consensus yet regarding dose, dilution, or injection sites. One vial of onabotulinumtoxinA contains 100 U and is reconstituted in 20 mL of normal saline to produce 5 U/mL. The simplest technique involves the injection of 5 U into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base, at the level of or just proximal to the A1 pulley, for a total of 50 U per hand.7 In the foot, injection can be made at the base of each toe near the proximal phalanges. A regimen of 50 to 100 U per hand was used by Neumeister et al5 on 19 patients, who subsequently standardized it to 10 U on each neurovascular bundle in a follow-up study,7 giving a total volume of 2 mL per injection. Associated pain or a burning sensation initially may be experienced, which may be mitigated by a lidocaine hydrochloride wrist block prior to injection.7 This technique produced immediate and lasting pain relief, increased tissue perfusion, and resolved digital ulcers in 28 of 33 patients. Most patients reported immediate relief, and a few noted gradual reduction in pain and resolution of chronic ulcers within 2 months. Of the 33 patients, 7 (21.2%) required repeat injections for recurrent pain, but the majority were pain free up to 6 years later with a single injection schedule.7

Injection into the palmar region, wrists, and/or fingers also may be performed. Effects of using different injection sites (eg, neurovascular bundle, distal palm, proximal hand) have been explored and were not notably different between these locations.8 Lastly, the frequency of injections may be attenuated according to the spectrum and severity of the patient’s symptoms. In a report of 11 patients who received a total of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA per hand, 5 required repeat injections within 3 to 8 months.9

Studies have reported onabotulinumtoxinA to be a promising option for the treatment of intractable symptoms. Likewise, our patient had a notable reduction in pain with signs of clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours after injection. The need for amputation 6 months later likely was because the patient’s toes were already necrosing prior to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. Thus, the timing of intervention may play a critical role in response to onabotulinumtoxinA injections, particularly because the severity of our patient’s presentation was comparable to other cases reported in the literature. Even in reports using a smaller dose—2 U injected into each toe as opposed to 10 U per toe, as in our case—follow-up showed favorable results.10 In other reports, response can be perceived within days to a week, with remarkable improvement of numbness, pain, digit color, and wound resolution, in addition to decreased frequency and severity of attacks. Moreover, greater vasodilation and subsequent tissue perfusion have been evidenced by objective measures including digital transcutaneous oxygen saturation and Doppler sonography.7,8 Side effects, which are minimal and temporary, include local pain triggering a vasospastic attack and intrinsic muscle weakness; more rarely, dysesthesia and thenar eminence atrophy have been reported.11

Available studies have shown onabotulinumtoxinA to produce favorable results in the treatment of vasospastic disease. We suspect that an earlier intervention for our patient—before necrosis of the toes developed—would have led to a more positive outcome, consistent with other reports. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA is an approach to consider when the standard-of-care treatments for RP have been exhausted, as timely intervention may prevent the need for surgery. The indications and appropriate dosing protocol remain to be defined, in addition to more thorough evaluation of its efficacy relative to other medical and surgical options.

- Neumeister MW. The role of botulinum toxin in vasospastic disorders of the hand. Hand Clin. 2015;31:23-37. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2014.09.003

- Bakst R, Merola JF, Franks AG, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:633-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.004

- Iorio ML, Masden DL, Higgins JP. Botulinum toxin a treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.006

- Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:556-565. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507638

- Neumeister MW, Chambers CB, Herron MS, et al. Botox therapy for ischemic digits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:191-200. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80576

- Sycha T, Graninger M, Auff E, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:312-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.029

- Neumeister MW. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:2085-2092. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.09.019

- Fregene A, Ditmars D, Siddiqui A. Botulinum toxin type A: a treatment option for digital ischemia in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:446-452. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.026

- Van Beek AL, Lim PK, Gear AJL, et al. Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:217-226. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57

- Dhaliwal K, Griffin M, Denton CP, et al. The novel use of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the toes. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:2017-2019. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219348

- Eickhoff JC, Smith JK, Landau ME, et al. Iatrogenic thenar eminence atrophy after Botox A injection for secondary Raynaud phenomenon. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22:395-396. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000450

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is an episodic vasospasm of the digits that can lead to ulceration, gangrene, and autoamputation with prolonged ischemia. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP by paralyzing the muscles of the digital arteries. We report a case of a woman with severe RP secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections after multiple treatment modalities failed to improve her condition. We describe the dosage and injection technique used to produce clinical improvement in our patient and compare it to prior reports in the literature.

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for worsening foot pain of 5 days' duration with dusky purple color changes concerning for impending Raynaud crisis related to RP. The patient had a history of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) and SLE with overlapping symptoms of polymyositis and scleroderma. She had been hospitalized for RP multiple times prior to the current admission. She was medically managed with nifedipine, sildenafil, losartan potassium, aspirin, alprostadil, and prostaglandin infusions, and was surgically managed with a right-hand sympathectomy and right ulnar artery bypass graft that had subsequently thrombosed. At the current presentation, she had painful dusky toes on both feet though more pronounced on the left foot. She endorsed foot pain while walking and tenderness to palpation of the fingers, which were minimally improved with intravenous prostaglandins.

Physical examination revealed blanching of the digits in both hands with pits in the right fourth and left first digits. Dusky patches overlaid all the toes as well as the superior plantar aspects of the feet (Figure 1). Given the history of APS, a punch biopsy was performed on the left medial plantar foot and results showed no histologic evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy. Necrotic foci were present on the left and right second metatarsal bones, which were not reperfusable (Figure 2). The clinical findings and punch biopsy results favored RP as opposed to vasculopathy from APS.

Several interventions were attempted, and after 4 days with no response, the patient agreed to receive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. OnabotulinumtoxinA (5 U) was injected into the subcutaneous tissue of the medial and lateral aspects of each of the first and second toes near the proximal phalanges (40 U total). However, treatment could not be completed due to severe pain caused by the injections despite preprocedure regional nerve blocks to both lower extremities, preinjection icing, and lorazepam. Two days later, the patient tolerated onabotulinumtoxinA injections of all remaining digits of both feet (60 U total). She noted slight clinical improvement soon thereafter. One week after treatment of all 10 toes, she reported decreased pain and reduced duskiness of both feet (Figure 3).

One month later, the patient endorsed recurring pain in the hands and feet. Physical examination revealed reticular cyanosis and increased violaceous patches of the hands; the feet were overall unchanged from the prior hospitalization. At 4-month follow-up, there was gangrene on the left second, third, and fifth toe in addition to areas of induration noted on the fingers. She was repeatedly hospitalized over the next 6 months for pain management and gangrene of the toes, and finally underwent an amputation of the left and right second toe at the proximal and middle phalanx, respectively. She currently is continuing extensive medical management for pain and gangrene of the digits; she has not received additional onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Raynaud phenomenon is a vascular disorder characterized by intermittent arteriolar vasospasm of the digits, often due to cold temperature or stress. Approximately 90% of RP cases are primarily idiopathic, with the remaining cases secondary to other diseases, typically systemic sclerosis, SLE, or mixed connective tissue disease.1 Symptoms present with characteristic changing of hands from white (ischemia) to blue (hypoxia) to red (reperfusion). Episodic attacks of vasospasm and ischemia can be painful and lead to digital ulcerations and necrosis of the digits or hands. Other complications including digital tuft pits, pterygium inversum unguis, or torturous nail fold capillaries with capillary dropout also may be seen.2

Although the etiology is multifactorial, the pathophysiology primarily is due to an imbalance of vasodilation and vasoconstriction. Perturbed levels of vasodilatory mediators include nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and calcitonin gene-related peptide.3 Meanwhile, abnormal neural sympathetic control of α-adrenergic receptors located on smooth muscle vasculature and subsequent endothelial hyperproliferation may contribute to inappropriate vasoconstriction.4

The first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease refractory to conservative management includes monotherapy with dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. For severe disease, combination therapy involves addition of other classes of medications including phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, topical nitrates, angiotensin receptor blockers, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Intravenous prostacyclin, endothelin receptor blockers, and onabotulinumtoxinA injections may be added as third-line therapy. Finally, surgical management including sympathectomy with continued pharmacologic therapy may be needed for disease recalcitrant to the aforementioned options.2

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. The toxin’s mechanism of action involves inhibition of the release of presynaptic acetylcholine-containing vesicles at the neuromuscular junction through cleavage of sensory nerve action potential receptor proteins. In addition, it inhibits smooth muscle vasoconstriction and pain by blocking α2-adrenergic receptors on blood vessels and chronic pain-transmitting C fibers in nerves, respectively.3,5

Only recently has onabotulinumtoxinA been used for treatment of RP. Botulinum toxin is approved for the treatment of spastic and dystonic diseases such as blepharospasm, headaches in patients with chronic migraines, upper limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, torticollis, ocular strabismus, and hyperhidrosis.3 However, the versatility of its therapeutic effects is evident in its broad off-label clinical applications, including achalasia; carpal tunnel syndrome; and spasticity relating to stroke, paraplegia, and cerebral palsy, among many others.5

Few studies have analyzed the use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of RP.3,6 There is no consensus yet regarding dose, dilution, or injection sites. One vial of onabotulinumtoxinA contains 100 U and is reconstituted in 20 mL of normal saline to produce 5 U/mL. The simplest technique involves the injection of 5 U into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base, at the level of or just proximal to the A1 pulley, for a total of 50 U per hand.7 In the foot, injection can be made at the base of each toe near the proximal phalanges. A regimen of 50 to 100 U per hand was used by Neumeister et al5 on 19 patients, who subsequently standardized it to 10 U on each neurovascular bundle in a follow-up study,7 giving a total volume of 2 mL per injection. Associated pain or a burning sensation initially may be experienced, which may be mitigated by a lidocaine hydrochloride wrist block prior to injection.7 This technique produced immediate and lasting pain relief, increased tissue perfusion, and resolved digital ulcers in 28 of 33 patients. Most patients reported immediate relief, and a few noted gradual reduction in pain and resolution of chronic ulcers within 2 months. Of the 33 patients, 7 (21.2%) required repeat injections for recurrent pain, but the majority were pain free up to 6 years later with a single injection schedule.7

Injection into the palmar region, wrists, and/or fingers also may be performed. Effects of using different injection sites (eg, neurovascular bundle, distal palm, proximal hand) have been explored and were not notably different between these locations.8 Lastly, the frequency of injections may be attenuated according to the spectrum and severity of the patient’s symptoms. In a report of 11 patients who received a total of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA per hand, 5 required repeat injections within 3 to 8 months.9

Studies have reported onabotulinumtoxinA to be a promising option for the treatment of intractable symptoms. Likewise, our patient had a notable reduction in pain with signs of clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours after injection. The need for amputation 6 months later likely was because the patient’s toes were already necrosing prior to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. Thus, the timing of intervention may play a critical role in response to onabotulinumtoxinA injections, particularly because the severity of our patient’s presentation was comparable to other cases reported in the literature. Even in reports using a smaller dose—2 U injected into each toe as opposed to 10 U per toe, as in our case—follow-up showed favorable results.10 In other reports, response can be perceived within days to a week, with remarkable improvement of numbness, pain, digit color, and wound resolution, in addition to decreased frequency and severity of attacks. Moreover, greater vasodilation and subsequent tissue perfusion have been evidenced by objective measures including digital transcutaneous oxygen saturation and Doppler sonography.7,8 Side effects, which are minimal and temporary, include local pain triggering a vasospastic attack and intrinsic muscle weakness; more rarely, dysesthesia and thenar eminence atrophy have been reported.11

Available studies have shown onabotulinumtoxinA to produce favorable results in the treatment of vasospastic disease. We suspect that an earlier intervention for our patient—before necrosis of the toes developed—would have led to a more positive outcome, consistent with other reports. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA is an approach to consider when the standard-of-care treatments for RP have been exhausted, as timely intervention may prevent the need for surgery. The indications and appropriate dosing protocol remain to be defined, in addition to more thorough evaluation of its efficacy relative to other medical and surgical options.

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is an episodic vasospasm of the digits that can lead to ulceration, gangrene, and autoamputation with prolonged ischemia. OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP by paralyzing the muscles of the digital arteries. We report a case of a woman with severe RP secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who was treated with onabotulinumtoxinA injections after multiple treatment modalities failed to improve her condition. We describe the dosage and injection technique used to produce clinical improvement in our patient and compare it to prior reports in the literature.

A 33-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for worsening foot pain of 5 days' duration with dusky purple color changes concerning for impending Raynaud crisis related to RP. The patient had a history of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) and SLE with overlapping symptoms of polymyositis and scleroderma. She had been hospitalized for RP multiple times prior to the current admission. She was medically managed with nifedipine, sildenafil, losartan potassium, aspirin, alprostadil, and prostaglandin infusions, and was surgically managed with a right-hand sympathectomy and right ulnar artery bypass graft that had subsequently thrombosed. At the current presentation, she had painful dusky toes on both feet though more pronounced on the left foot. She endorsed foot pain while walking and tenderness to palpation of the fingers, which were minimally improved with intravenous prostaglandins.

Physical examination revealed blanching of the digits in both hands with pits in the right fourth and left first digits. Dusky patches overlaid all the toes as well as the superior plantar aspects of the feet (Figure 1). Given the history of APS, a punch biopsy was performed on the left medial plantar foot and results showed no histologic evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy. Necrotic foci were present on the left and right second metatarsal bones, which were not reperfusable (Figure 2). The clinical findings and punch biopsy results favored RP as opposed to vasculopathy from APS.

Several interventions were attempted, and after 4 days with no response, the patient agreed to receive treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. OnabotulinumtoxinA (5 U) was injected into the subcutaneous tissue of the medial and lateral aspects of each of the first and second toes near the proximal phalanges (40 U total). However, treatment could not be completed due to severe pain caused by the injections despite preprocedure regional nerve blocks to both lower extremities, preinjection icing, and lorazepam. Two days later, the patient tolerated onabotulinumtoxinA injections of all remaining digits of both feet (60 U total). She noted slight clinical improvement soon thereafter. One week after treatment of all 10 toes, she reported decreased pain and reduced duskiness of both feet (Figure 3).

One month later, the patient endorsed recurring pain in the hands and feet. Physical examination revealed reticular cyanosis and increased violaceous patches of the hands; the feet were overall unchanged from the prior hospitalization. At 4-month follow-up, there was gangrene on the left second, third, and fifth toe in addition to areas of induration noted on the fingers. She was repeatedly hospitalized over the next 6 months for pain management and gangrene of the toes, and finally underwent an amputation of the left and right second toe at the proximal and middle phalanx, respectively. She currently is continuing extensive medical management for pain and gangrene of the digits; she has not received additional onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Raynaud phenomenon is a vascular disorder characterized by intermittent arteriolar vasospasm of the digits, often due to cold temperature or stress. Approximately 90% of RP cases are primarily idiopathic, with the remaining cases secondary to other diseases, typically systemic sclerosis, SLE, or mixed connective tissue disease.1 Symptoms present with characteristic changing of hands from white (ischemia) to blue (hypoxia) to red (reperfusion). Episodic attacks of vasospasm and ischemia can be painful and lead to digital ulcerations and necrosis of the digits or hands. Other complications including digital tuft pits, pterygium inversum unguis, or torturous nail fold capillaries with capillary dropout also may be seen.2

Although the etiology is multifactorial, the pathophysiology primarily is due to an imbalance of vasodilation and vasoconstriction. Perturbed levels of vasodilatory mediators include nitric oxide, prostacyclin, and calcitonin gene-related peptide.3 Meanwhile, abnormal neural sympathetic control of α-adrenergic receptors located on smooth muscle vasculature and subsequent endothelial hyperproliferation may contribute to inappropriate vasoconstriction.4

The first-line therapy for mild to moderate disease refractory to conservative management includes monotherapy with dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. For severe disease, combination therapy involves addition of other classes of medications including phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors, topical nitrates, angiotensin receptor blockers, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Intravenous prostacyclin, endothelin receptor blockers, and onabotulinumtoxinA injections may be added as third-line therapy. Finally, surgical management including sympathectomy with continued pharmacologic therapy may be needed for disease recalcitrant to the aforementioned options.2

OnabotulinumtoxinA is a neurotoxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. The toxin’s mechanism of action involves inhibition of the release of presynaptic acetylcholine-containing vesicles at the neuromuscular junction through cleavage of sensory nerve action potential receptor proteins. In addition, it inhibits smooth muscle vasoconstriction and pain by blocking α2-adrenergic receptors on blood vessels and chronic pain-transmitting C fibers in nerves, respectively.3,5

Only recently has onabotulinumtoxinA been used for treatment of RP. Botulinum toxin is approved for the treatment of spastic and dystonic diseases such as blepharospasm, headaches in patients with chronic migraines, upper limb spasticity, cervical dystonia, torticollis, ocular strabismus, and hyperhidrosis.3 However, the versatility of its therapeutic effects is evident in its broad off-label clinical applications, including achalasia; carpal tunnel syndrome; and spasticity relating to stroke, paraplegia, and cerebral palsy, among many others.5

Few studies have analyzed the use of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of RP.3,6 There is no consensus yet regarding dose, dilution, or injection sites. One vial of onabotulinumtoxinA contains 100 U and is reconstituted in 20 mL of normal saline to produce 5 U/mL. The simplest technique involves the injection of 5 U into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base, at the level of or just proximal to the A1 pulley, for a total of 50 U per hand.7 In the foot, injection can be made at the base of each toe near the proximal phalanges. A regimen of 50 to 100 U per hand was used by Neumeister et al5 on 19 patients, who subsequently standardized it to 10 U on each neurovascular bundle in a follow-up study,7 giving a total volume of 2 mL per injection. Associated pain or a burning sensation initially may be experienced, which may be mitigated by a lidocaine hydrochloride wrist block prior to injection.7 This technique produced immediate and lasting pain relief, increased tissue perfusion, and resolved digital ulcers in 28 of 33 patients. Most patients reported immediate relief, and a few noted gradual reduction in pain and resolution of chronic ulcers within 2 months. Of the 33 patients, 7 (21.2%) required repeat injections for recurrent pain, but the majority were pain free up to 6 years later with a single injection schedule.7

Injection into the palmar region, wrists, and/or fingers also may be performed. Effects of using different injection sites (eg, neurovascular bundle, distal palm, proximal hand) have been explored and were not notably different between these locations.8 Lastly, the frequency of injections may be attenuated according to the spectrum and severity of the patient’s symptoms. In a report of 11 patients who received a total of 100 U of onabotulinumtoxinA per hand, 5 required repeat injections within 3 to 8 months.9

Studies have reported onabotulinumtoxinA to be a promising option for the treatment of intractable symptoms. Likewise, our patient had a notable reduction in pain with signs of clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours after injection. The need for amputation 6 months later likely was because the patient’s toes were already necrosing prior to treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA. Thus, the timing of intervention may play a critical role in response to onabotulinumtoxinA injections, particularly because the severity of our patient’s presentation was comparable to other cases reported in the literature. Even in reports using a smaller dose—2 U injected into each toe as opposed to 10 U per toe, as in our case—follow-up showed favorable results.10 In other reports, response can be perceived within days to a week, with remarkable improvement of numbness, pain, digit color, and wound resolution, in addition to decreased frequency and severity of attacks. Moreover, greater vasodilation and subsequent tissue perfusion have been evidenced by objective measures including digital transcutaneous oxygen saturation and Doppler sonography.7,8 Side effects, which are minimal and temporary, include local pain triggering a vasospastic attack and intrinsic muscle weakness; more rarely, dysesthesia and thenar eminence atrophy have been reported.11

Available studies have shown onabotulinumtoxinA to produce favorable results in the treatment of vasospastic disease. We suspect that an earlier intervention for our patient—before necrosis of the toes developed—would have led to a more positive outcome, consistent with other reports. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA is an approach to consider when the standard-of-care treatments for RP have been exhausted, as timely intervention may prevent the need for surgery. The indications and appropriate dosing protocol remain to be defined, in addition to more thorough evaluation of its efficacy relative to other medical and surgical options.

- Neumeister MW. The role of botulinum toxin in vasospastic disorders of the hand. Hand Clin. 2015;31:23-37. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2014.09.003

- Bakst R, Merola JF, Franks AG, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:633-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.004

- Iorio ML, Masden DL, Higgins JP. Botulinum toxin a treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.006

- Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:556-565. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507638

- Neumeister MW, Chambers CB, Herron MS, et al. Botox therapy for ischemic digits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:191-200. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80576

- Sycha T, Graninger M, Auff E, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:312-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.029

- Neumeister MW. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:2085-2092. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.09.019

- Fregene A, Ditmars D, Siddiqui A. Botulinum toxin type A: a treatment option for digital ischemia in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:446-452. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.026

- Van Beek AL, Lim PK, Gear AJL, et al. Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:217-226. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57

- Dhaliwal K, Griffin M, Denton CP, et al. The novel use of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the toes. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:2017-2019. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219348

- Eickhoff JC, Smith JK, Landau ME, et al. Iatrogenic thenar eminence atrophy after Botox A injection for secondary Raynaud phenomenon. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22:395-396. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000450

- Neumeister MW. The role of botulinum toxin in vasospastic disorders of the hand. Hand Clin. 2015;31:23-37. doi:10.1016/j.hcl.2014.09.003

- Bakst R, Merola JF, Franks AG, et al. Raynaud’s phenomenon: pathogenesis and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:633-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.004

- Iorio ML, Masden DL, Higgins JP. Botulinum toxin a treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:599-603. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.006

- Wigley FM, Flavahan NA. Raynaud’s phenomenon. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:556-565. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1507638

- Neumeister MW, Chambers CB, Herron MS, et al. Botox therapy for ischemic digits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:191-200. doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a80576

- Sycha T, Graninger M, Auff E, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a pilot study. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:312-313. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.06.029

- Neumeister MW. Botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:2085-2092. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.09.019

- Fregene A, Ditmars D, Siddiqui A. Botulinum toxin type A: a treatment option for digital ischemia in patients with Raynaud’s phenomenon. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34:446-452. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.026

- Van Beek AL, Lim PK, Gear AJL, et al. Management of vasospastic disorders with botulinum toxin A. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:217-226. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000244860.00674.57

- Dhaliwal K, Griffin M, Denton CP, et al. The novel use of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon in the toes. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:2017-2019. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-219348

- Eickhoff JC, Smith JK, Landau ME, et al. Iatrogenic thenar eminence atrophy after Botox A injection for secondary Raynaud phenomenon. J Clin Rheumatol. 2016;22:395-396. doi:10.1097/RHU.0000000000000450

Practice Points

- Raynaud phenomenon (RP) is a vascular disorder characterized by episodic vasospasms of the digits often due to cold temperature or stress.

- OnabotulinumtoxinA has been implemented as a treatment of intractable RP after failure with traditional treatments, such as calcium channel blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers, prostaglandins, endothelin receptor blockers, and phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors.

- A standard technique of delivery of onabotulinumtoxinA involves injection of 5 U/mL into the medial and lateral aspects of each finger at its base (near the metacarpal head) for a total of 50 U per hand or foot.

Flagellate Shiitake Mushroom Reaction With Histologic Features of Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

To the Editor:

A 59-year-old man presented with a severely pruritic rash on the legs, arms, abdomen, groin, and buttocks of 3 days’ duration. He reported subjective fever and chills. Prior to the appearance of the rash, the patient and his family had eaten shiitake mushrooms daily for 3 days. He denied any new medications in the last several months or any recent upper respiratory or gastrointestinal tract illnesses. His medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetes-induced end-stage renal disease requiring home peritoneal dialysis. His long-term medications for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, benign prostatic hyperplasia, hyperlipidemia, and insomnia included amlodipine, atorvastatin, finasteride, gabapentin, insulin glargine, linagliptin, metoprolol, and mirtazapine.

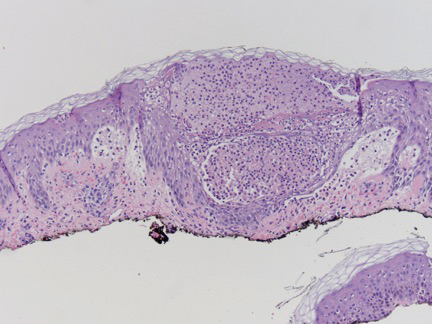

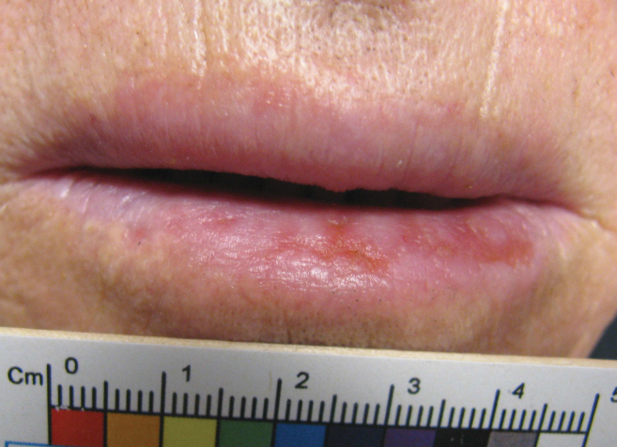

Physical examination revealed an afebrile man with medium brown skin tone and diffuse, bright red, erythematous patches on the lower legs, axillae, medial forearms, lateral trunk, lower abdomen, and groin. There were distinct flagellate, linear, red patches on the lower legs (Figure 1). In addition, small clusters of 1- to 2-mm superficial pustules were present on the right upper medial thigh and left forearm with micropapules grouped in the skin folds.

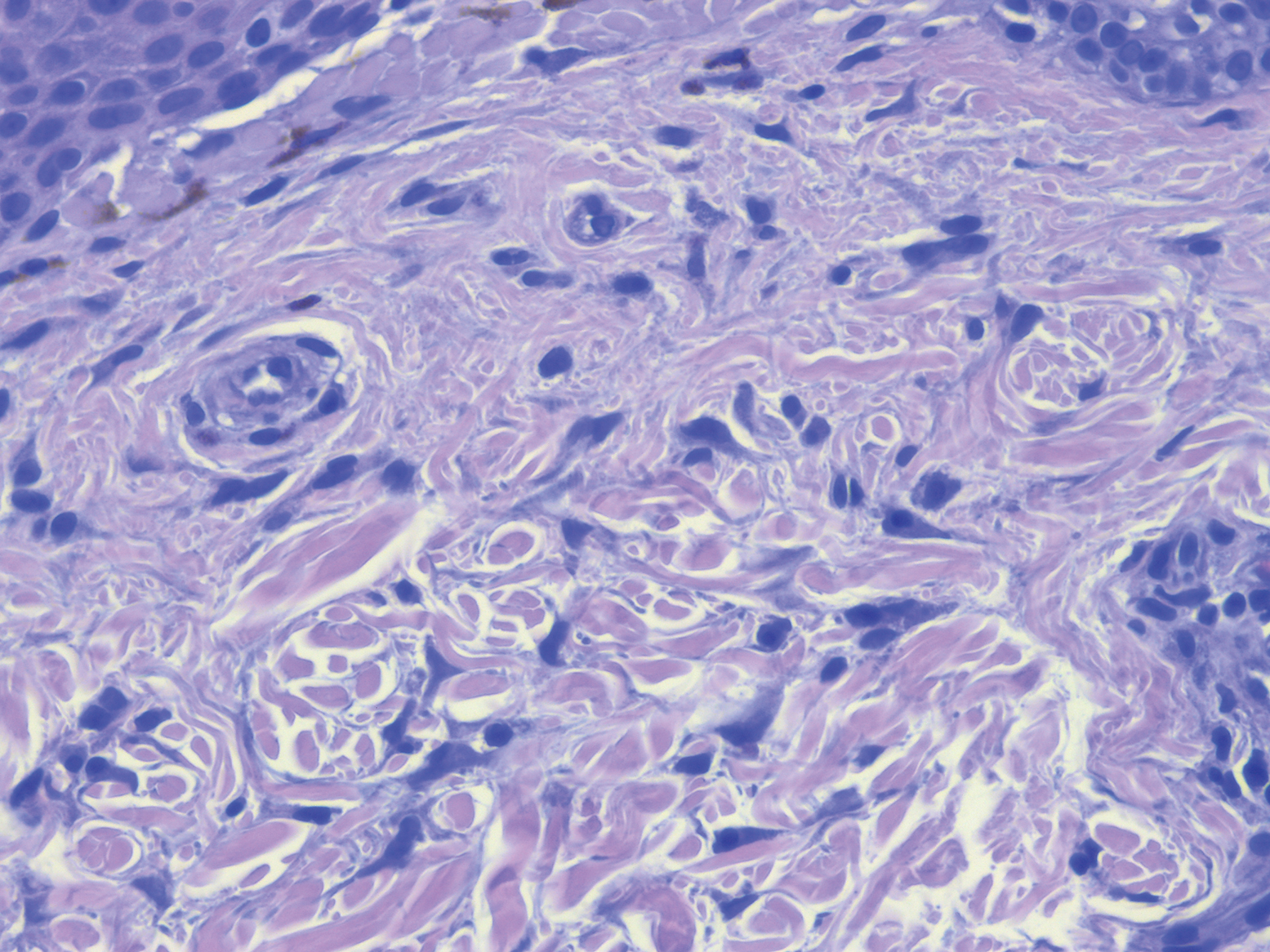

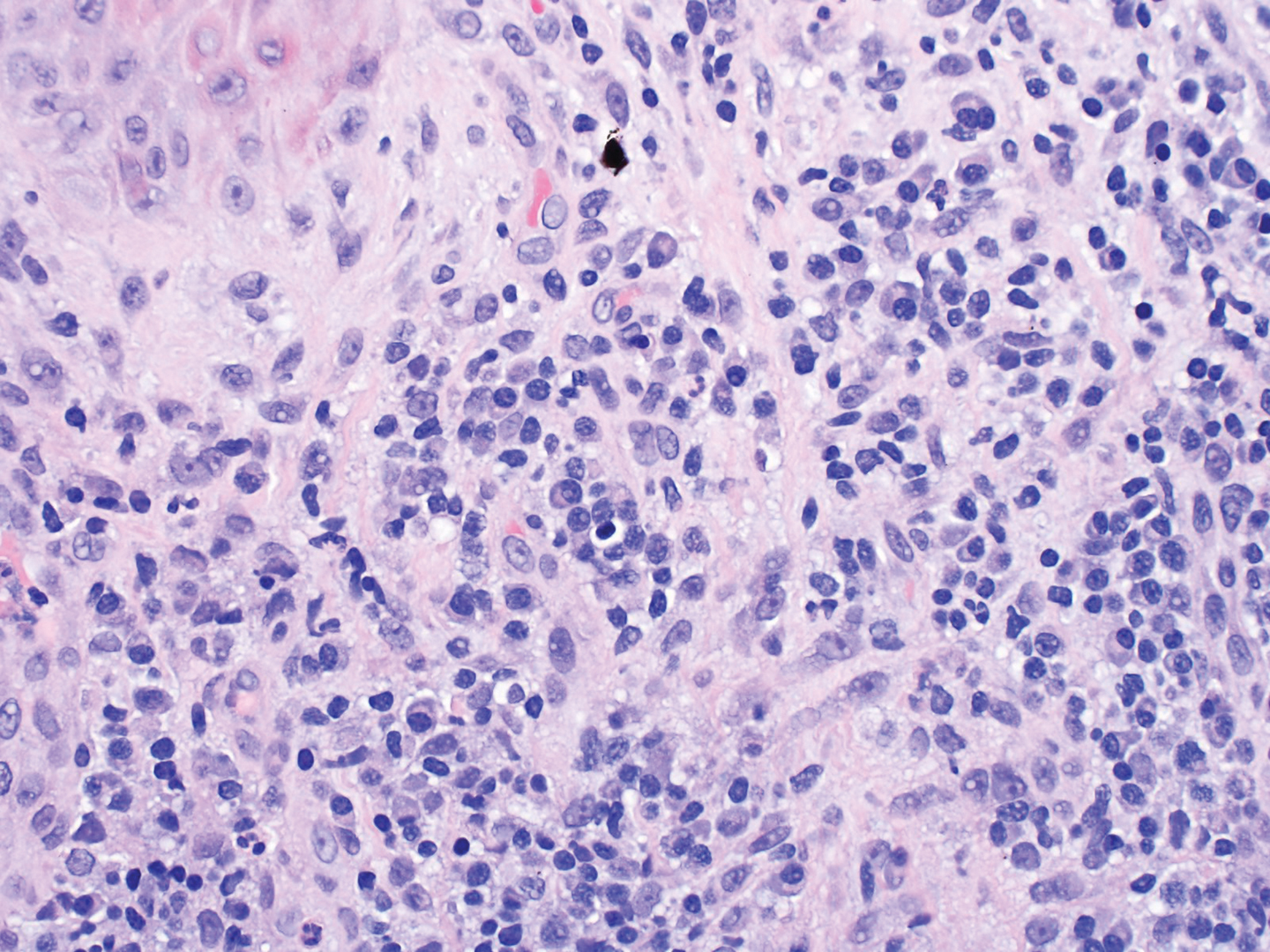

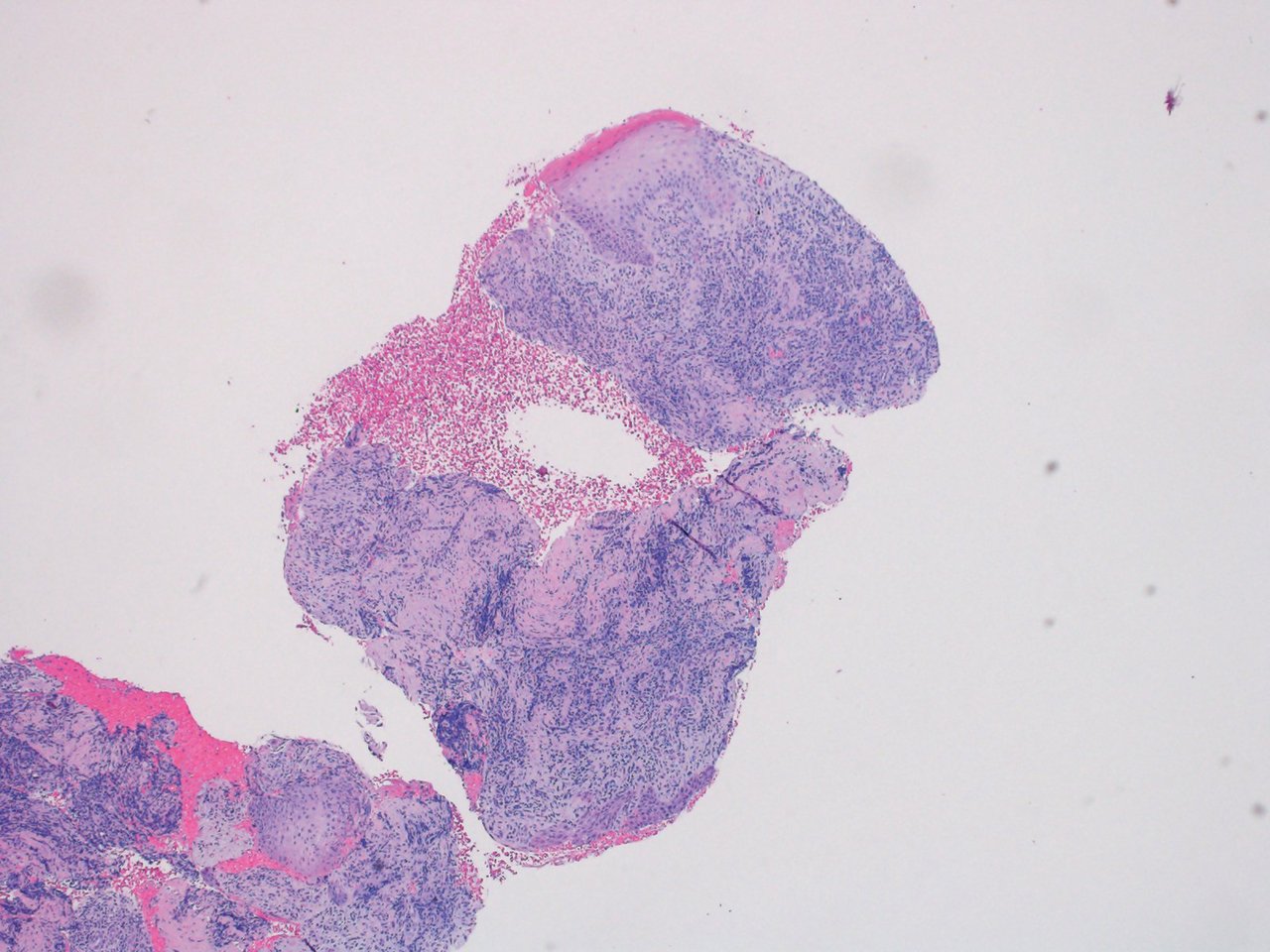

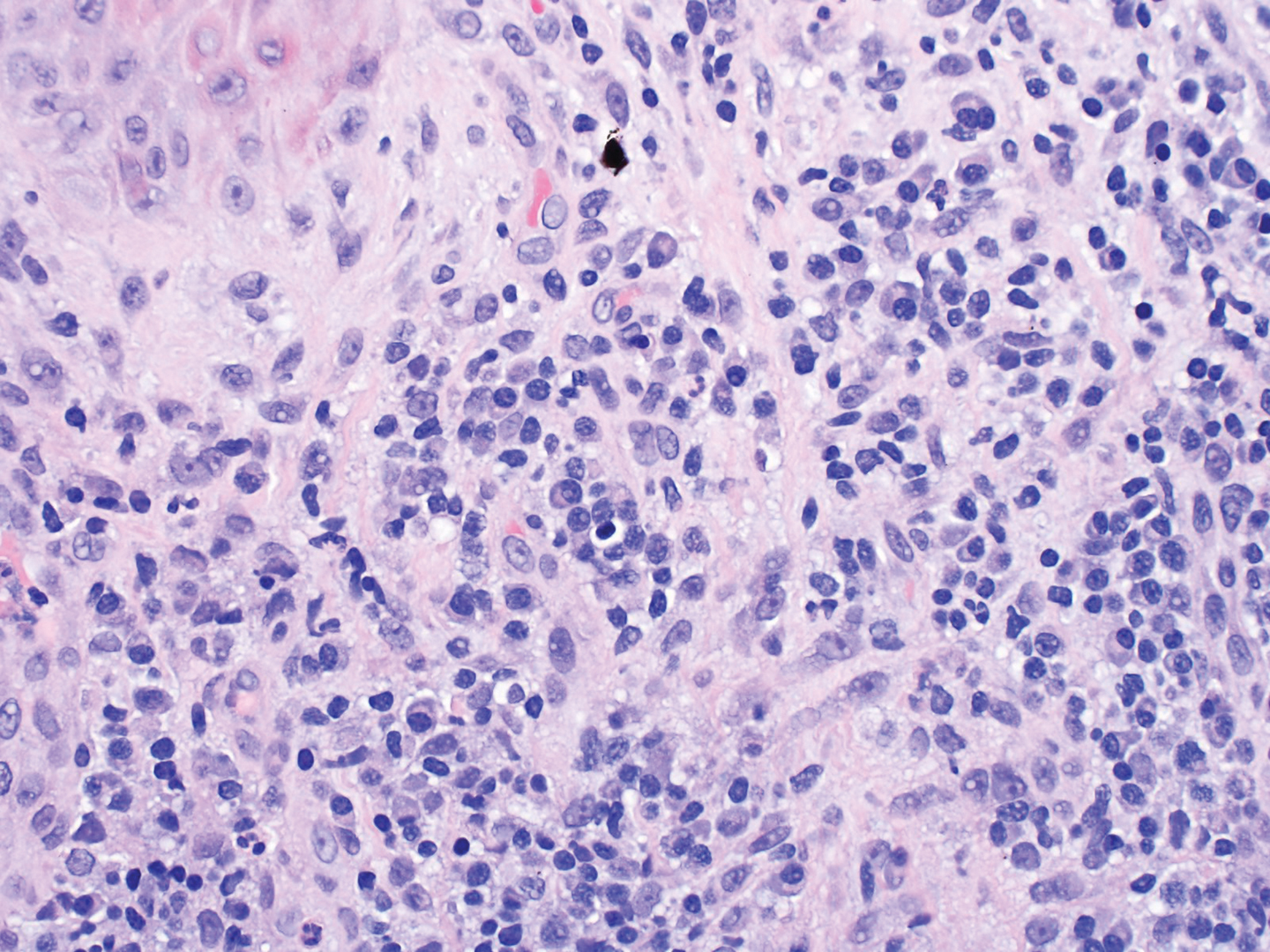

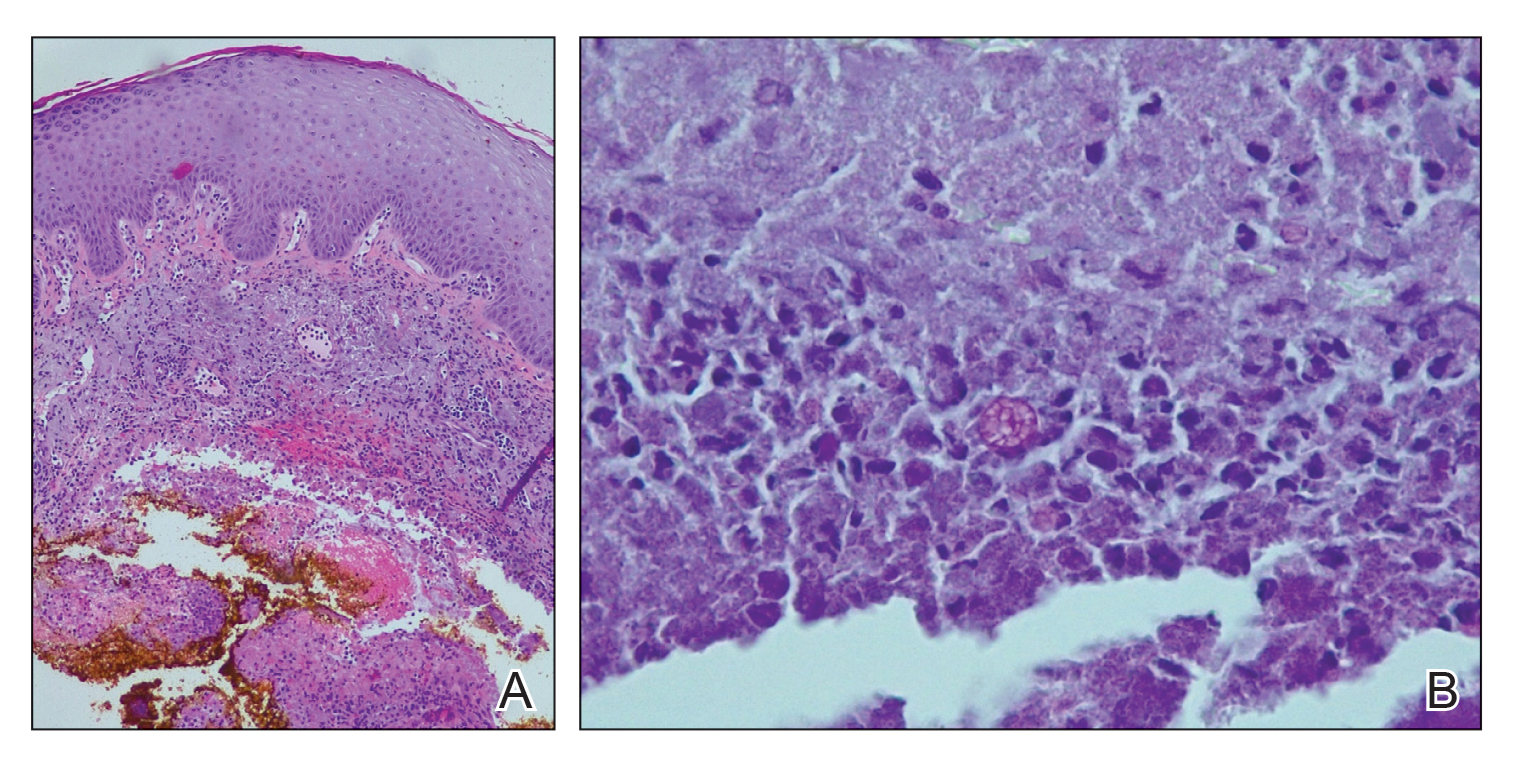

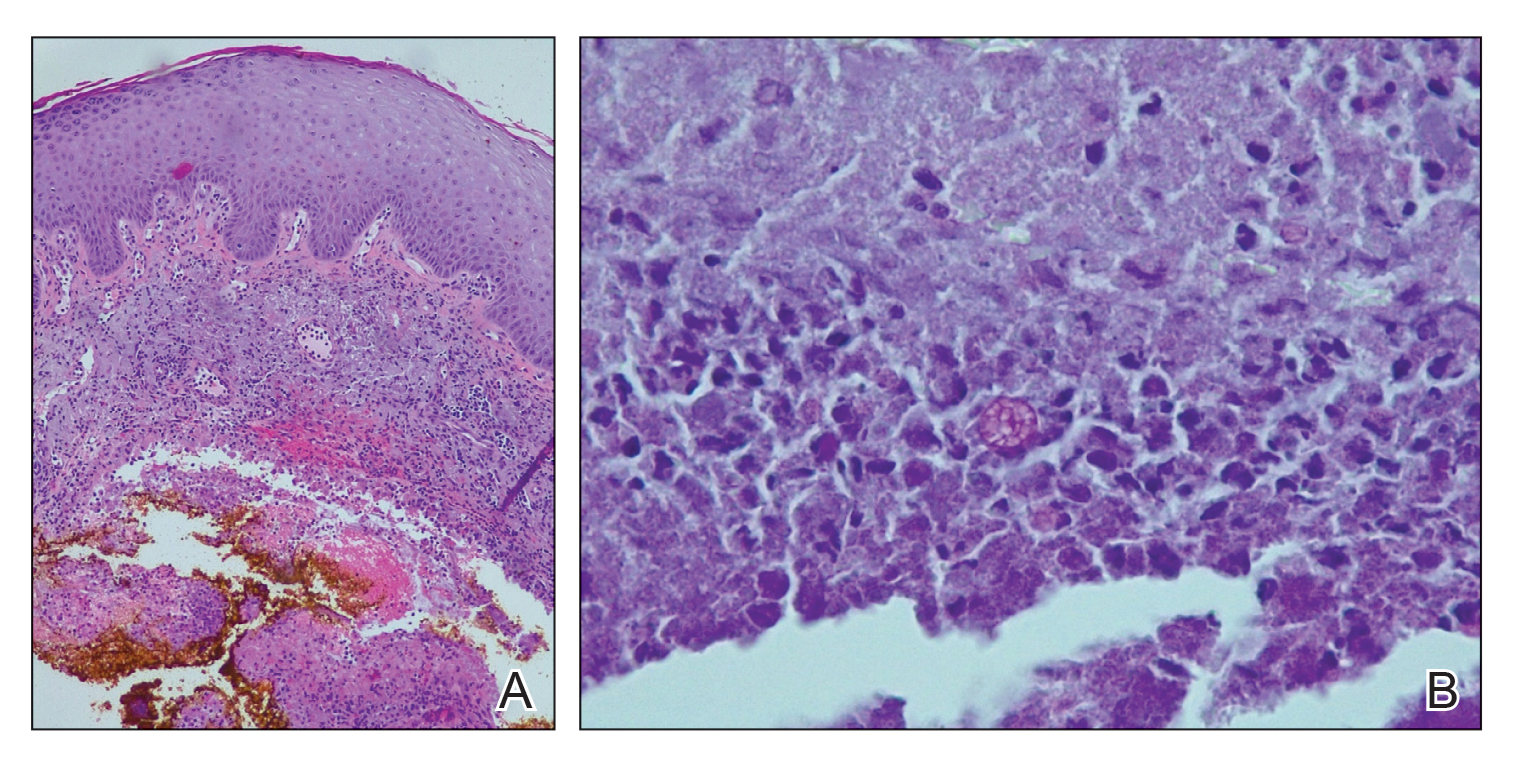

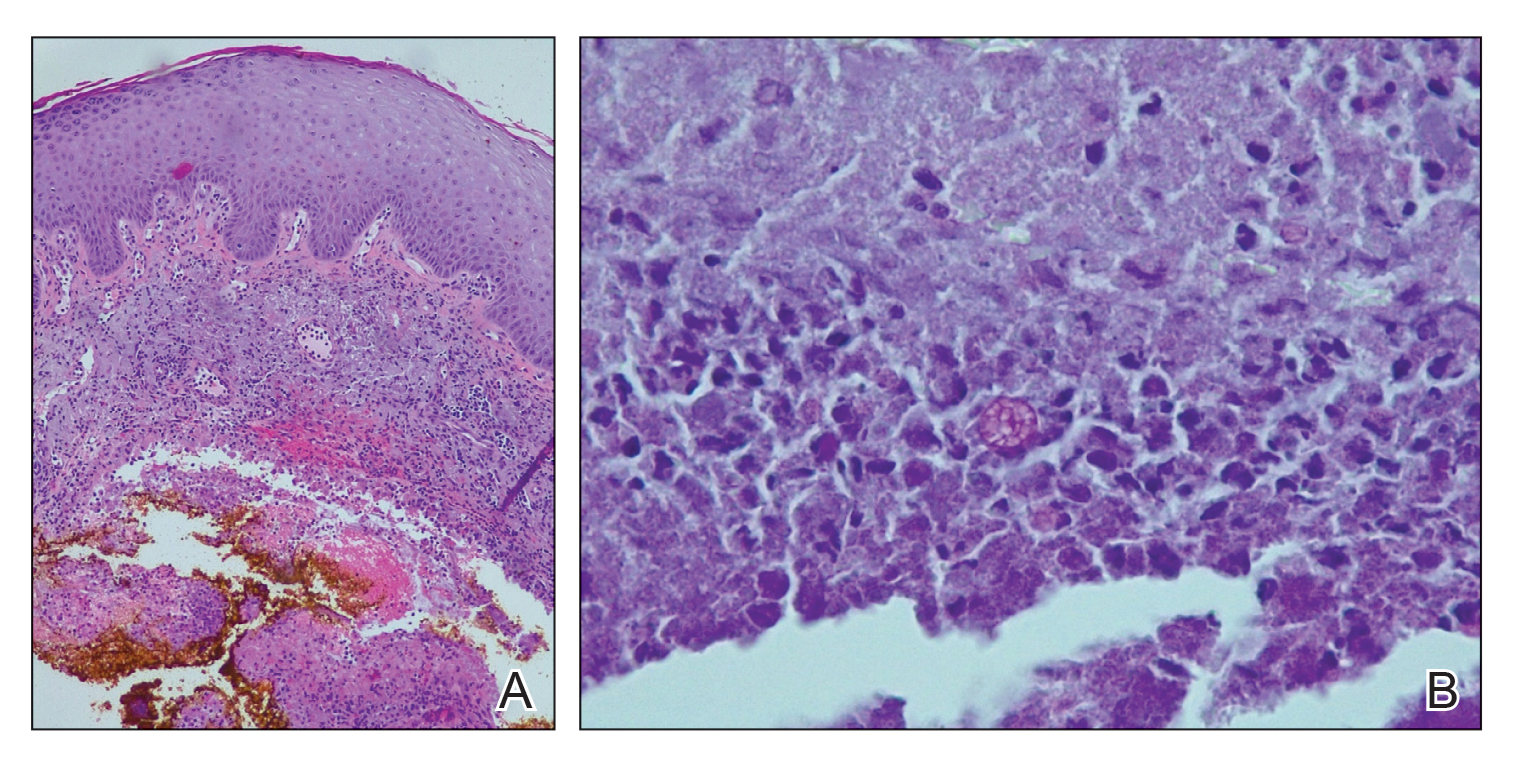

A shave biopsy specimen from a pustule on the right upper medial thigh revealed spongiotic dermatitis with neutrophilic subcorneal pustule formation and frequent eosinophils (Figure 2). The dermis contained scattered mixed inflammatory cells including neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes (Figure 3). These histologic findings were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). No biopsy was performed on the flagellate patches due to its clinically distinct presentation and well-established association with shiitake mushroom ingestion.

The patient was treated with triamcinolone ointment and systemic corticosteroids to reduce pruritus and quickly clear the lesions due to his comorbidities. He recovered completely within 1 week and had no evidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation from the flagellate dermatitis.

Flagellate dermatitis is an intensely pruritic dermatitis characterized by 1-mm, disseminated, erythematous papules in a linear grouped arrangement secondary to koebnerization due to the patient scratching. It was first described in 1977 by Nakamura.1 Although it rarely is seen outside of China and Japan, there are well-established associations of flagellate dermatitis with bleomycin and shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes) ingestion. One key clinical difference between the two causes is that postinflammatory hyperpigmentation changes usually are seen with bleomycin-induced flagellate dermatitis and typically are not present with shiitake mushroom–induced flagellate dermatitis.2 Following ingestion of shiitake mushrooms, the median time of onset of presentation typically is 24 hours but ranges from 12 hours to 5 days. Most patients completely recover by 3 weeks, with or without treatment.3 Although the pathogenesis of shiitake mushroom–induced flagellate dermatitis is not clear, the most common theory is a toxic reaction to lentinan, a polysaccharide isolated from shiitake mushrooms. However, type I and IV allergic hypersensitivities also have been supported by the time of onset, clearance, severe pruritus, benefit from steroids and antihistamines, and lack of grouped outbreaks in people exposed to shared meals containing shiitake mushrooms.3,4 Furthermore, there is a case of patch test–confirmed allergic contact dermatitis to shiitake mushrooms, demonstrating a 1+ reaction at 96 hours to the cap of a shiitake mushroom but a negative pin-prick test at 20 minutes, suggesting type IV hypersensitivity.5 An additional case revealed a positive skin-prick test with formation of a 4-mm wheal and subsequent pruritic papules and vesicles appearing 48 to 72 hours later at the prick site.6 Subsequent cases have been reported in association with consumption of raw shiitake mushrooms, but cases have been reported after consumption of fully cooked mushrooms, which does not support a toxin-mediated theory, as cooking the mushroom before consumption likely would denature or change the structure of the suspected toxin.2