User login

Sarcoidosis Presenting as Telangiectatic Macules

To the Editor:

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, noncaseating, granulomatous disorder thought to occur from a combination of immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors.1 Often referred to as the “great imitator,” the cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis encompass many morphologies, including papules, plaques, nodules, and scars.1 We report an unusual case of sarcoidosis presenting as telangiectatic macules on the lower extremities.

A woman in her early 30s presented with a burning, pruritic, erythematous, telangiectatic eruption on the lower extremities with concurrent ankle swelling of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied any fevers, chills, recent infections, or new medications. Evaluation by her primary care physician during the time of the eruption included unremarkable antinuclear antibodies, thyroid stimulating hormone level, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, chest radiography, and lower-extremity Doppler ultrasonography.

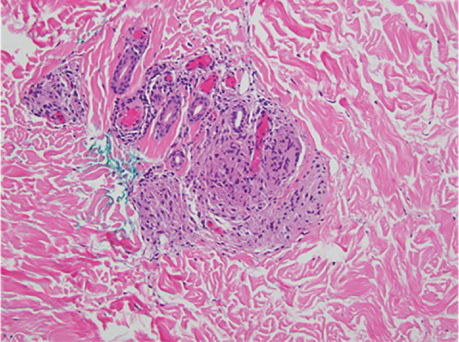

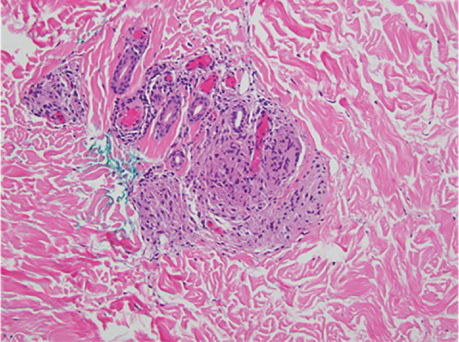

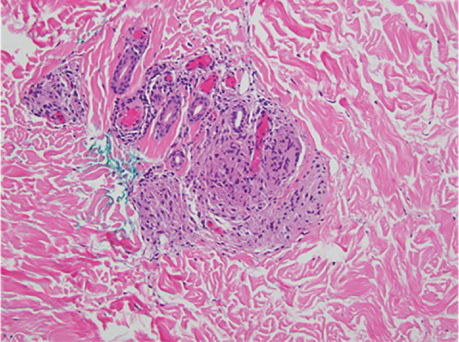

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed numerous scattered, faint, erythematous, blanchable macules on the lower extremities along with mild pitting edema (Figure 1). The patient’s current medications included cetirizine, which she had been taking for years, as well as an intrauterine device. A punch biopsy from the right lower leg revealed small, well-demarcated sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation surrounding vascular structures and skin appendages (Figure 2). No foreign bodies were observed with polarized light microscopy. Microscopic findings suggestive of an infection, including caseation necrosis and suppurative inflammation, also were absent. Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal. Myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 IgG antibody levels were evaluated due to potential vascular involvement but were negative. An infectious cause of the sarcoidal granulomas was unlikely given histopathologic findings and negative tuberculosis skin testing, which the patient underwent annually for her job, so a tissue culture was not performed. The patient was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for the itching and burning at the initial visit and was continued on this treatment after the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made. At 2-month follow-up, the patient’s eruption had nearly resolved with topical therapy.

Cutaneous manifestation occurs in 20% to 35% of sarcoidosis cases and may develop in the presence or absence of systemic disease. Approximately 60% of individuals with cutaneous sarcoidosis are found to have systemic involvement; therefore, careful monitoring and diagnostic workup are important in the management of these patients.2 While most cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis are papular, it is important for clinicians to maintain a level of suspicion for sarcoidosis in any uncertain dermatologic presentation.1,2 Evidence of telangiectasias has been shown in rarer forms of sarcoidosis (eg, angiolupoid), but the lesions usually are confined to the face, ears, or neck.3 Granulomatous vasculitis has been reported in a small number of individuals with ulcerative sarcoidosis.4 In our case, no ulcerations were present, possibly indicating an early lesion or an entirely novel process. Lastly, although reticular dermal granulomas are found in drug-induced interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, these lesions often are dispersed interstitially amongst collagen bundles and are associated with necrobiosis of collagen and eosinophilic/neutrophilic infiltrates.5 The lack of these characteristic pathologic findings in our patient along with no known reported cases of cetirizine-induced granulomatous dermatitis led us to rule out reticular dermal granulomas as a diagnosis. We present our case as a reminder of the diversity of cutaneous sarcoidosis manifestations and the importance of early diagnosis of these lesions.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.E1-E18.

- Yanardag H, Tetikkurt C, Bilir M, et al. Diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis; clinical and the prognostic significance of skin lesions. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8:26.

- Arias-Santiago S, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Aneiros- Fernández J, et al. Recurrent telangiectasias on the cheek: angiolupoid sarcoidosis. Am J Med. 2010;123:E7-E8.

- Wei C-H, Huang Y-H, Shih Y-C, et al. Sarcoidosis with cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:198-201.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

To the Editor:

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, noncaseating, granulomatous disorder thought to occur from a combination of immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors.1 Often referred to as the “great imitator,” the cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis encompass many morphologies, including papules, plaques, nodules, and scars.1 We report an unusual case of sarcoidosis presenting as telangiectatic macules on the lower extremities.

A woman in her early 30s presented with a burning, pruritic, erythematous, telangiectatic eruption on the lower extremities with concurrent ankle swelling of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied any fevers, chills, recent infections, or new medications. Evaluation by her primary care physician during the time of the eruption included unremarkable antinuclear antibodies, thyroid stimulating hormone level, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, chest radiography, and lower-extremity Doppler ultrasonography.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed numerous scattered, faint, erythematous, blanchable macules on the lower extremities along with mild pitting edema (Figure 1). The patient’s current medications included cetirizine, which she had been taking for years, as well as an intrauterine device. A punch biopsy from the right lower leg revealed small, well-demarcated sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation surrounding vascular structures and skin appendages (Figure 2). No foreign bodies were observed with polarized light microscopy. Microscopic findings suggestive of an infection, including caseation necrosis and suppurative inflammation, also were absent. Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal. Myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 IgG antibody levels were evaluated due to potential vascular involvement but were negative. An infectious cause of the sarcoidal granulomas was unlikely given histopathologic findings and negative tuberculosis skin testing, which the patient underwent annually for her job, so a tissue culture was not performed. The patient was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for the itching and burning at the initial visit and was continued on this treatment after the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made. At 2-month follow-up, the patient’s eruption had nearly resolved with topical therapy.

Cutaneous manifestation occurs in 20% to 35% of sarcoidosis cases and may develop in the presence or absence of systemic disease. Approximately 60% of individuals with cutaneous sarcoidosis are found to have systemic involvement; therefore, careful monitoring and diagnostic workup are important in the management of these patients.2 While most cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis are papular, it is important for clinicians to maintain a level of suspicion for sarcoidosis in any uncertain dermatologic presentation.1,2 Evidence of telangiectasias has been shown in rarer forms of sarcoidosis (eg, angiolupoid), but the lesions usually are confined to the face, ears, or neck.3 Granulomatous vasculitis has been reported in a small number of individuals with ulcerative sarcoidosis.4 In our case, no ulcerations were present, possibly indicating an early lesion or an entirely novel process. Lastly, although reticular dermal granulomas are found in drug-induced interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, these lesions often are dispersed interstitially amongst collagen bundles and are associated with necrobiosis of collagen and eosinophilic/neutrophilic infiltrates.5 The lack of these characteristic pathologic findings in our patient along with no known reported cases of cetirizine-induced granulomatous dermatitis led us to rule out reticular dermal granulomas as a diagnosis. We present our case as a reminder of the diversity of cutaneous sarcoidosis manifestations and the importance of early diagnosis of these lesions.

To the Editor:

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem, noncaseating, granulomatous disorder thought to occur from a combination of immunologic, genetic, and environmental factors.1 Often referred to as the “great imitator,” the cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis encompass many morphologies, including papules, plaques, nodules, and scars.1 We report an unusual case of sarcoidosis presenting as telangiectatic macules on the lower extremities.

A woman in her early 30s presented with a burning, pruritic, erythematous, telangiectatic eruption on the lower extremities with concurrent ankle swelling of 4 weeks’ duration. The patient denied any fevers, chills, recent infections, or new medications. Evaluation by her primary care physician during the time of the eruption included unremarkable antinuclear antibodies, thyroid stimulating hormone level, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, urinalysis, chest radiography, and lower-extremity Doppler ultrasonography.

Physical examination at the current presentation revealed numerous scattered, faint, erythematous, blanchable macules on the lower extremities along with mild pitting edema (Figure 1). The patient’s current medications included cetirizine, which she had been taking for years, as well as an intrauterine device. A punch biopsy from the right lower leg revealed small, well-demarcated sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation surrounding vascular structures and skin appendages (Figure 2). No foreign bodies were observed with polarized light microscopy. Microscopic findings suggestive of an infection, including caseation necrosis and suppurative inflammation, also were absent. Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal. Myeloperoxidase and proteinase 3 IgG antibody levels were evaluated due to potential vascular involvement but were negative. An infectious cause of the sarcoidal granulomas was unlikely given histopathologic findings and negative tuberculosis skin testing, which the patient underwent annually for her job, so a tissue culture was not performed. The patient was prescribed triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1% for the itching and burning at the initial visit and was continued on this treatment after the diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made. At 2-month follow-up, the patient’s eruption had nearly resolved with topical therapy.

Cutaneous manifestation occurs in 20% to 35% of sarcoidosis cases and may develop in the presence or absence of systemic disease. Approximately 60% of individuals with cutaneous sarcoidosis are found to have systemic involvement; therefore, careful monitoring and diagnostic workup are important in the management of these patients.2 While most cases of cutaneous sarcoidosis are papular, it is important for clinicians to maintain a level of suspicion for sarcoidosis in any uncertain dermatologic presentation.1,2 Evidence of telangiectasias has been shown in rarer forms of sarcoidosis (eg, angiolupoid), but the lesions usually are confined to the face, ears, or neck.3 Granulomatous vasculitis has been reported in a small number of individuals with ulcerative sarcoidosis.4 In our case, no ulcerations were present, possibly indicating an early lesion or an entirely novel process. Lastly, although reticular dermal granulomas are found in drug-induced interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, these lesions often are dispersed interstitially amongst collagen bundles and are associated with necrobiosis of collagen and eosinophilic/neutrophilic infiltrates.5 The lack of these characteristic pathologic findings in our patient along with no known reported cases of cetirizine-induced granulomatous dermatitis led us to rule out reticular dermal granulomas as a diagnosis. We present our case as a reminder of the diversity of cutaneous sarcoidosis manifestations and the importance of early diagnosis of these lesions.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.E1-E18.

- Yanardag H, Tetikkurt C, Bilir M, et al. Diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis; clinical and the prognostic significance of skin lesions. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8:26.

- Arias-Santiago S, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Aneiros- Fernández J, et al. Recurrent telangiectasias on the cheek: angiolupoid sarcoidosis. Am J Med. 2010;123:E7-E8.

- Wei C-H, Huang Y-H, Shih Y-C, et al. Sarcoidosis with cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:198-201.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

- Haimovic A, Sanchez M, Judson MA, et al. Sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review and update for the dermatologist: part I. cutaneous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:699.E1-E18.

- Yanardag H, Tetikkurt C, Bilir M, et al. Diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis; clinical and the prognostic significance of skin lesions. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8:26.

- Arias-Santiago S, Fernández-Pugnaire MA, Aneiros- Fernández J, et al. Recurrent telangiectasias on the cheek: angiolupoid sarcoidosis. Am J Med. 2010;123:E7-E8.

- Wei C-H, Huang Y-H, Shih Y-C, et al. Sarcoidosis with cutaneous granulomatous vasculitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:198-201.

- Peroni A, Colato C, Schena D, et al. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis: a distinct entity with characteristic histological and clinical pattern. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:775-783.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous manifestations of sarcoidosis can encompass numerous morphologies. A high degree of suspicion should be maintained for any uncertain dermatologic presentation.

- Although papular eruptions are the most common cutaneous findings in sarcoidosis, this case report illustrates a less common vascular-appearing presentation.

- A systemic workup is indicated in any presentation of sarcoidosis.

Tylosis in a Patient With Howel-Evans Syndrome: Management With Acitretin

To the Editor:

Tylosis with esophageal cancer was first described by Howel-Evans et al1 in 1958 in a family from Liverpool, England. The disease is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with a mutation in the tylosis with esophageal cancer gene, TOC.2 The keratoderma associated with this syndrome has been reported to be focal in nature, painful, and primarily involving the plantar surfaces.3 Palmar involvement has been reported to manifest as calluses in patients who use their hands for manual labor.4 Oral leukoplakia also has been described in this syndrome5; however, long-term follow-up in one family demonstrated a benign course.6 Herein, we describe a case of painful tylosis in a patient with Howel-Evans syndrome who was successfully treated with acitretin.

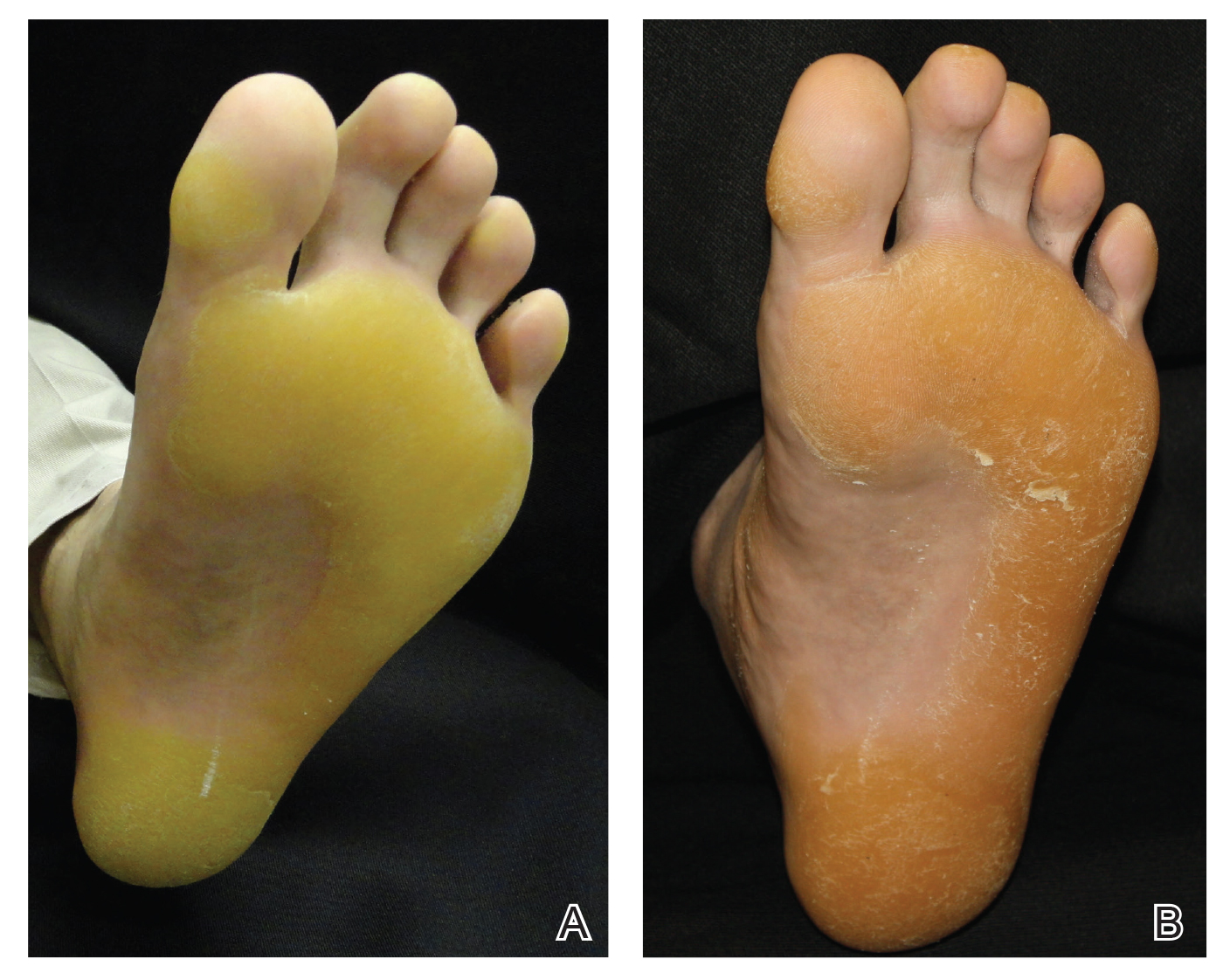

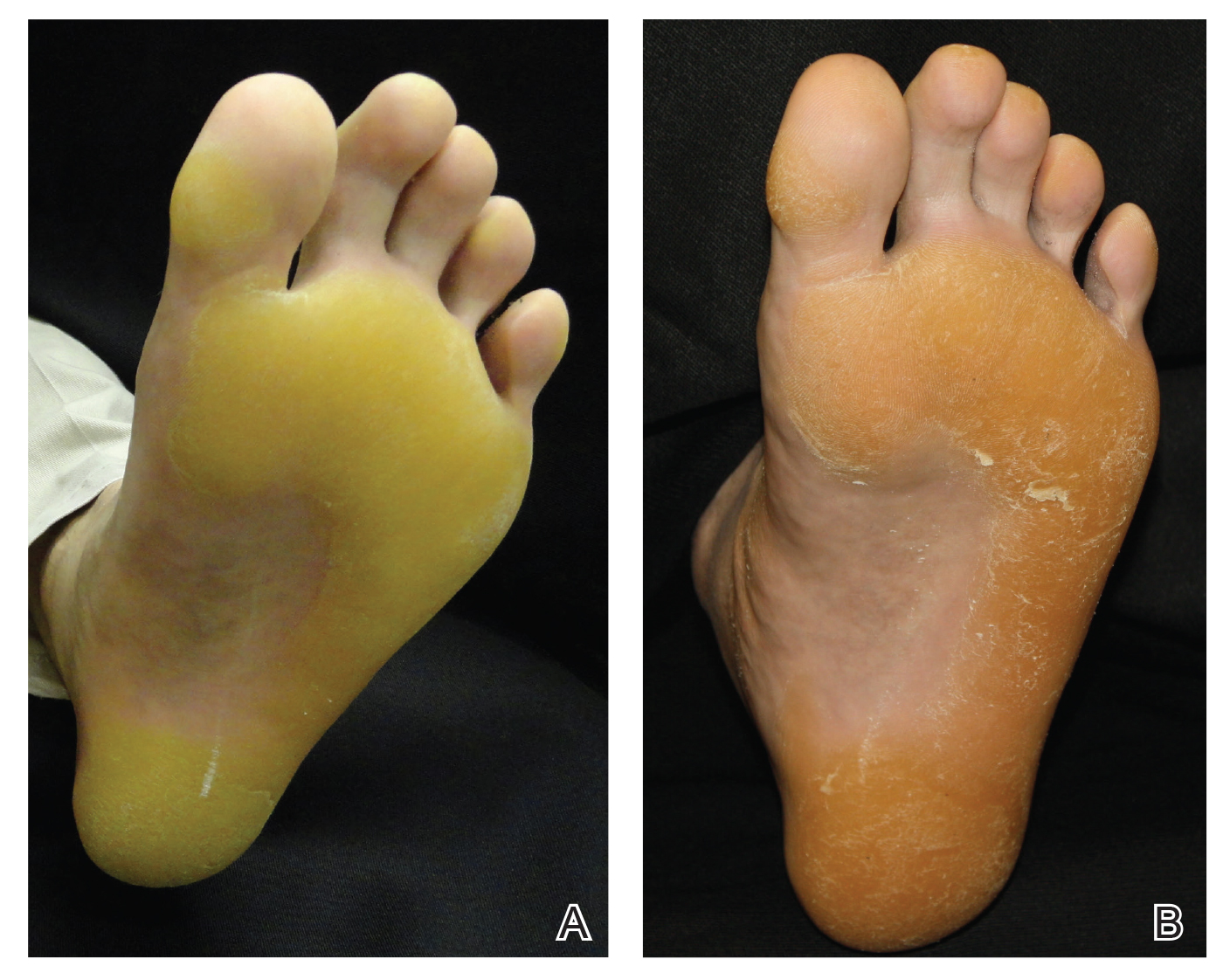

A 50-year-old man presented to clinic for evaluation of hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles that began when he was a teenager. He reported the soles of the feet often were painful, especially without shoes (Figure, A). He used many over-the-counter emollients and tried both prescription and nonprescription keratolytics. At presentation, he was mechanically paring down some of the thickness of the calluses to decrease the pain.

There was no relevant medical history, he had no history of smoking, he consumed more than 1 alcoholic drink per day, and he denied illicit drug use. The patient was not on any other medications. His family history revealed that his father also had the same hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles and died from esophageal carcinoma at an early age. It was determined that his father had tylosis with esophageal carcinoma (Howel-Evans syndrome). (The patient’s pedigree previously was published.3,4) Physical examination at presentation revealed plantar hyperkeratosis limited mainly to areas of pressure. His hands had mild hyperkeratosis on the distal fingers. No mucosa leukoplakia was identified.

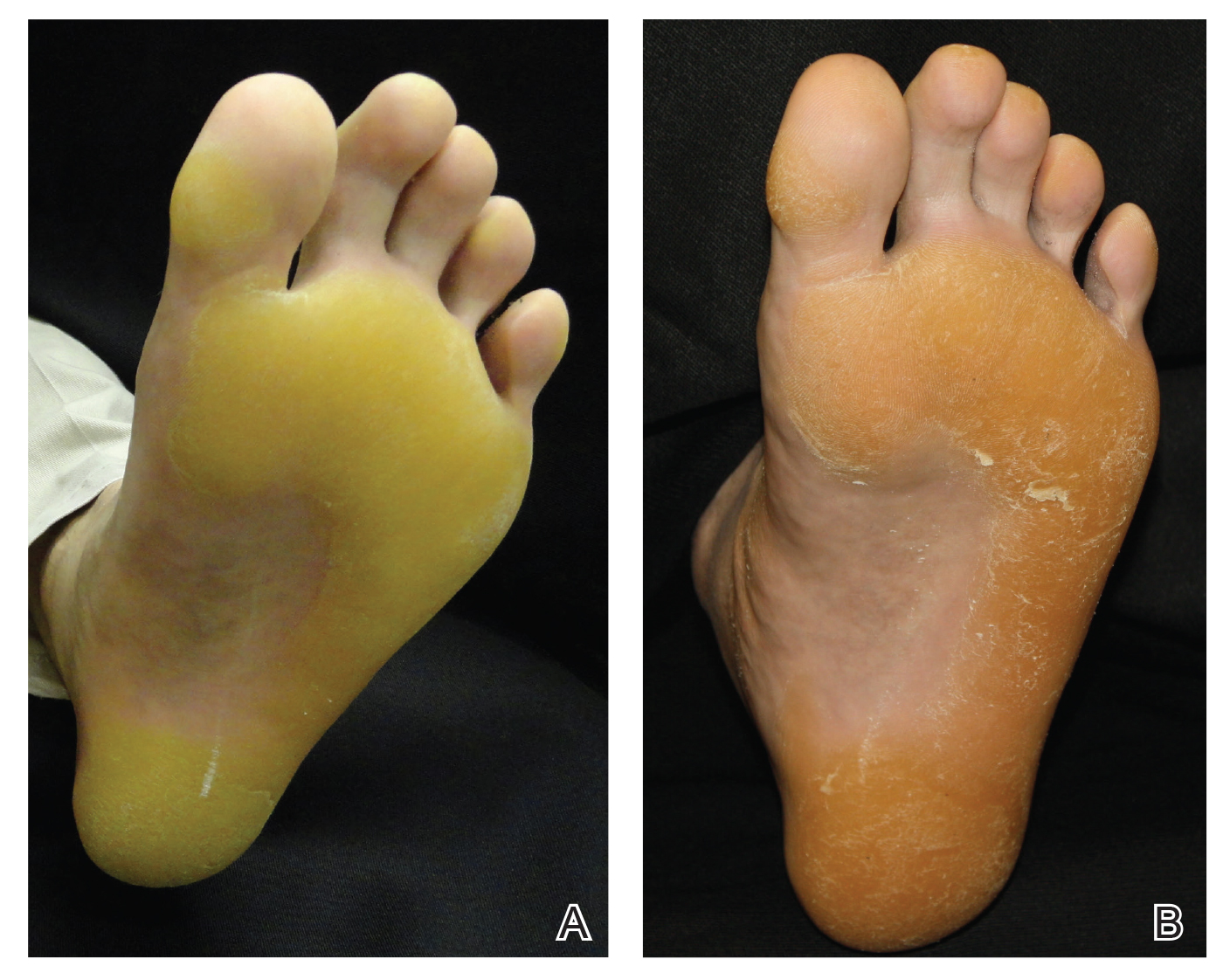

Treatment options were discussed, and because the pain associated with the plantar keratoderma was interfering with his quality of life (QOL), acitretin was started. The initial dosage was 10 mg daily for 2 weeks and subsequently was increased to 25 mg daily. He has been maintained on this dosage for more than a year. An attempt was made to increase acitretin to 50 mg daily; however, he could not tolerate the dryness and peeling of the hands caused by the higher dosage. A fasting lipid panel and hepatic function panel performed every 3 months was within reference range. He had a remarkable decrease in the hyperkeratosis 2 months after starting therapy (Figure, B) and most importantly a decrease in pain associated with it. His QOL notably improved, enabling him to participate in sporting events with his children without severe pain. This patient was referred to gastroenterology where an esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed and no concerning lesions were found. He was continued on this dose for 2 years. He moved to a new town, and our most recent update from him was that he was taking acitretin intermittently before big sporting events with his children.

The use of systemic retinoids has long been known to be effective in the treatment of disorders of keratinization. Recommended monitoring guidelines include a baseline complete blood cell count, renal function, hepatic function, and fasting lipid panel, which should be repeated every 3 months focusing on the hepatic function and lipid panel, as retinoids rarely cause hematologic or renal abnormalities.7 Our patient’s baseline laboratory test results were within reference range, and we repeated a fasting lipid and hepatic function panel every 3 months without any abnormalities.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), the ossification of ligaments and entheses often of the spine, is a potential complication of long-term use of oral retinoids. There are no consensus guidelines on screening for this complication, but baseline and annual radiographs seem reasonable. A 1996 study concluded that if DISH occurs, it is likely to be sporadic in a predisposed patient, as their data did not find any statistically significant relationship between the treatment or the cumulative dose and the prevalence and severity of DISH, degenerative changes, and osteoporosis.8 When annual screening is declined, imaging could be performed if a new skeletal concern were to arise in patients on long-term therapy.7 We discussed the skeletal concerns with our patient and he declined baseline or annual radiographs, but we will follow him with a rheumatologic review of systems. We feel this approach is reasonable, as our patient is a healthy adult in his 50s with no prior retinoid exposure and is on a low to moderate dose.

We report a case of Howel-Evans keratoderma successfully managed with acitretin. In patients with painful keratoderma that is interfering with QOL, low-dose acitretin can be used to diminish these symptoms.

- Howel-Evans W, McConnell RB, Clarke CA, et al. Carcinoma of the oesophagus with keratosis palmaris et plantaris (tylosis): a study of two families. Q J Med. 1958;27:413-429.

- Rogaev EI, Rogaeva EA, Ginter EK, et al. Identification of the genetic locus for keratosis palmaris et plantaris on chromosome 17 near the RARA and keratin type I genes. Nat Genet. 1993;5:158-162.

- Stevens HP, Kelsell DP, Bryant SP, et al. Linkage of an American pedigree with palmoplantar keratoderma and malignancy (palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasia type III) to 17q24. literature survey and proposed updated classification of the keratodermas. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:640-651.

- Marger RS, Marger D. Carcinoma of the esophagus and tylosis. a lethal genetic combination. Cancer. 1993;72:17-19.

- Tyldesley WR. Oral leukoplakia associated with tylosis and esophageal carcinoma. J Oral Pathol. 1974;3:62-70.

- Ellis A, Field JK, Field EA, et al. Tylosis associated with carcinoma of the oesophagus and oral leukoplakia in a large Liverpool family—a review of six generations. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1994;30B:102-112.

- Wu J, Wolverton S. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton S, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2020:245-262.

- Van Dooren-Greebe RJ, Lemmens JA, De Boo T, et al. Prolonged treatment with oral retinoids in adults: no influence on the frequency and severity of spinal abnormalities. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:71-76.

To the Editor:

Tylosis with esophageal cancer was first described by Howel-Evans et al1 in 1958 in a family from Liverpool, England. The disease is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with a mutation in the tylosis with esophageal cancer gene, TOC.2 The keratoderma associated with this syndrome has been reported to be focal in nature, painful, and primarily involving the plantar surfaces.3 Palmar involvement has been reported to manifest as calluses in patients who use their hands for manual labor.4 Oral leukoplakia also has been described in this syndrome5; however, long-term follow-up in one family demonstrated a benign course.6 Herein, we describe a case of painful tylosis in a patient with Howel-Evans syndrome who was successfully treated with acitretin.

A 50-year-old man presented to clinic for evaluation of hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles that began when he was a teenager. He reported the soles of the feet often were painful, especially without shoes (Figure, A). He used many over-the-counter emollients and tried both prescription and nonprescription keratolytics. At presentation, he was mechanically paring down some of the thickness of the calluses to decrease the pain.

There was no relevant medical history, he had no history of smoking, he consumed more than 1 alcoholic drink per day, and he denied illicit drug use. The patient was not on any other medications. His family history revealed that his father also had the same hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles and died from esophageal carcinoma at an early age. It was determined that his father had tylosis with esophageal carcinoma (Howel-Evans syndrome). (The patient’s pedigree previously was published.3,4) Physical examination at presentation revealed plantar hyperkeratosis limited mainly to areas of pressure. His hands had mild hyperkeratosis on the distal fingers. No mucosa leukoplakia was identified.

Treatment options were discussed, and because the pain associated with the plantar keratoderma was interfering with his quality of life (QOL), acitretin was started. The initial dosage was 10 mg daily for 2 weeks and subsequently was increased to 25 mg daily. He has been maintained on this dosage for more than a year. An attempt was made to increase acitretin to 50 mg daily; however, he could not tolerate the dryness and peeling of the hands caused by the higher dosage. A fasting lipid panel and hepatic function panel performed every 3 months was within reference range. He had a remarkable decrease in the hyperkeratosis 2 months after starting therapy (Figure, B) and most importantly a decrease in pain associated with it. His QOL notably improved, enabling him to participate in sporting events with his children without severe pain. This patient was referred to gastroenterology where an esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed and no concerning lesions were found. He was continued on this dose for 2 years. He moved to a new town, and our most recent update from him was that he was taking acitretin intermittently before big sporting events with his children.

The use of systemic retinoids has long been known to be effective in the treatment of disorders of keratinization. Recommended monitoring guidelines include a baseline complete blood cell count, renal function, hepatic function, and fasting lipid panel, which should be repeated every 3 months focusing on the hepatic function and lipid panel, as retinoids rarely cause hematologic or renal abnormalities.7 Our patient’s baseline laboratory test results were within reference range, and we repeated a fasting lipid and hepatic function panel every 3 months without any abnormalities.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), the ossification of ligaments and entheses often of the spine, is a potential complication of long-term use of oral retinoids. There are no consensus guidelines on screening for this complication, but baseline and annual radiographs seem reasonable. A 1996 study concluded that if DISH occurs, it is likely to be sporadic in a predisposed patient, as their data did not find any statistically significant relationship between the treatment or the cumulative dose and the prevalence and severity of DISH, degenerative changes, and osteoporosis.8 When annual screening is declined, imaging could be performed if a new skeletal concern were to arise in patients on long-term therapy.7 We discussed the skeletal concerns with our patient and he declined baseline or annual radiographs, but we will follow him with a rheumatologic review of systems. We feel this approach is reasonable, as our patient is a healthy adult in his 50s with no prior retinoid exposure and is on a low to moderate dose.

We report a case of Howel-Evans keratoderma successfully managed with acitretin. In patients with painful keratoderma that is interfering with QOL, low-dose acitretin can be used to diminish these symptoms.

To the Editor:

Tylosis with esophageal cancer was first described by Howel-Evans et al1 in 1958 in a family from Liverpool, England. The disease is inherited in an autosomal-dominant fashion with a mutation in the tylosis with esophageal cancer gene, TOC.2 The keratoderma associated with this syndrome has been reported to be focal in nature, painful, and primarily involving the plantar surfaces.3 Palmar involvement has been reported to manifest as calluses in patients who use their hands for manual labor.4 Oral leukoplakia also has been described in this syndrome5; however, long-term follow-up in one family demonstrated a benign course.6 Herein, we describe a case of painful tylosis in a patient with Howel-Evans syndrome who was successfully treated with acitretin.

A 50-year-old man presented to clinic for evaluation of hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles that began when he was a teenager. He reported the soles of the feet often were painful, especially without shoes (Figure, A). He used many over-the-counter emollients and tried both prescription and nonprescription keratolytics. At presentation, he was mechanically paring down some of the thickness of the calluses to decrease the pain.

There was no relevant medical history, he had no history of smoking, he consumed more than 1 alcoholic drink per day, and he denied illicit drug use. The patient was not on any other medications. His family history revealed that his father also had the same hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles and died from esophageal carcinoma at an early age. It was determined that his father had tylosis with esophageal carcinoma (Howel-Evans syndrome). (The patient’s pedigree previously was published.3,4) Physical examination at presentation revealed plantar hyperkeratosis limited mainly to areas of pressure. His hands had mild hyperkeratosis on the distal fingers. No mucosa leukoplakia was identified.

Treatment options were discussed, and because the pain associated with the plantar keratoderma was interfering with his quality of life (QOL), acitretin was started. The initial dosage was 10 mg daily for 2 weeks and subsequently was increased to 25 mg daily. He has been maintained on this dosage for more than a year. An attempt was made to increase acitretin to 50 mg daily; however, he could not tolerate the dryness and peeling of the hands caused by the higher dosage. A fasting lipid panel and hepatic function panel performed every 3 months was within reference range. He had a remarkable decrease in the hyperkeratosis 2 months after starting therapy (Figure, B) and most importantly a decrease in pain associated with it. His QOL notably improved, enabling him to participate in sporting events with his children without severe pain. This patient was referred to gastroenterology where an esophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed and no concerning lesions were found. He was continued on this dose for 2 years. He moved to a new town, and our most recent update from him was that he was taking acitretin intermittently before big sporting events with his children.

The use of systemic retinoids has long been known to be effective in the treatment of disorders of keratinization. Recommended monitoring guidelines include a baseline complete blood cell count, renal function, hepatic function, and fasting lipid panel, which should be repeated every 3 months focusing on the hepatic function and lipid panel, as retinoids rarely cause hematologic or renal abnormalities.7 Our patient’s baseline laboratory test results were within reference range, and we repeated a fasting lipid and hepatic function panel every 3 months without any abnormalities.

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), the ossification of ligaments and entheses often of the spine, is a potential complication of long-term use of oral retinoids. There are no consensus guidelines on screening for this complication, but baseline and annual radiographs seem reasonable. A 1996 study concluded that if DISH occurs, it is likely to be sporadic in a predisposed patient, as their data did not find any statistically significant relationship between the treatment or the cumulative dose and the prevalence and severity of DISH, degenerative changes, and osteoporosis.8 When annual screening is declined, imaging could be performed if a new skeletal concern were to arise in patients on long-term therapy.7 We discussed the skeletal concerns with our patient and he declined baseline or annual radiographs, but we will follow him with a rheumatologic review of systems. We feel this approach is reasonable, as our patient is a healthy adult in his 50s with no prior retinoid exposure and is on a low to moderate dose.

We report a case of Howel-Evans keratoderma successfully managed with acitretin. In patients with painful keratoderma that is interfering with QOL, low-dose acitretin can be used to diminish these symptoms.

- Howel-Evans W, McConnell RB, Clarke CA, et al. Carcinoma of the oesophagus with keratosis palmaris et plantaris (tylosis): a study of two families. Q J Med. 1958;27:413-429.

- Rogaev EI, Rogaeva EA, Ginter EK, et al. Identification of the genetic locus for keratosis palmaris et plantaris on chromosome 17 near the RARA and keratin type I genes. Nat Genet. 1993;5:158-162.

- Stevens HP, Kelsell DP, Bryant SP, et al. Linkage of an American pedigree with palmoplantar keratoderma and malignancy (palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasia type III) to 17q24. literature survey and proposed updated classification of the keratodermas. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:640-651.

- Marger RS, Marger D. Carcinoma of the esophagus and tylosis. a lethal genetic combination. Cancer. 1993;72:17-19.

- Tyldesley WR. Oral leukoplakia associated with tylosis and esophageal carcinoma. J Oral Pathol. 1974;3:62-70.

- Ellis A, Field JK, Field EA, et al. Tylosis associated with carcinoma of the oesophagus and oral leukoplakia in a large Liverpool family—a review of six generations. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1994;30B:102-112.

- Wu J, Wolverton S. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton S, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2020:245-262.

- Van Dooren-Greebe RJ, Lemmens JA, De Boo T, et al. Prolonged treatment with oral retinoids in adults: no influence on the frequency and severity of spinal abnormalities. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:71-76.

- Howel-Evans W, McConnell RB, Clarke CA, et al. Carcinoma of the oesophagus with keratosis palmaris et plantaris (tylosis): a study of two families. Q J Med. 1958;27:413-429.

- Rogaev EI, Rogaeva EA, Ginter EK, et al. Identification of the genetic locus for keratosis palmaris et plantaris on chromosome 17 near the RARA and keratin type I genes. Nat Genet. 1993;5:158-162.

- Stevens HP, Kelsell DP, Bryant SP, et al. Linkage of an American pedigree with palmoplantar keratoderma and malignancy (palmoplantar ectodermal dysplasia type III) to 17q24. literature survey and proposed updated classification of the keratodermas. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:640-651.

- Marger RS, Marger D. Carcinoma of the esophagus and tylosis. a lethal genetic combination. Cancer. 1993;72:17-19.

- Tyldesley WR. Oral leukoplakia associated with tylosis and esophageal carcinoma. J Oral Pathol. 1974;3:62-70.

- Ellis A, Field JK, Field EA, et al. Tylosis associated with carcinoma of the oesophagus and oral leukoplakia in a large Liverpool family—a review of six generations. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1994;30B:102-112.

- Wu J, Wolverton S. Systemic retinoids. In: Wolverton S, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2020:245-262.

- Van Dooren-Greebe RJ, Lemmens JA, De Boo T, et al. Prolonged treatment with oral retinoids in adults: no influence on the frequency and severity of spinal abnormalities. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134:71-76.

Practice Points

- Keratoderma can be especially painful for patients and can have a great impact on their quality of life. For these patients, acitretin should be considered when topical therapies have failed.

- Howel-Evans syndrome is an autosomal-dominant condition that predominantly presents with plantar keratoderma and has a high risk for esophageal cancer.