User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

A new (old) drug joins the COVID fray, and guess what? It works

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

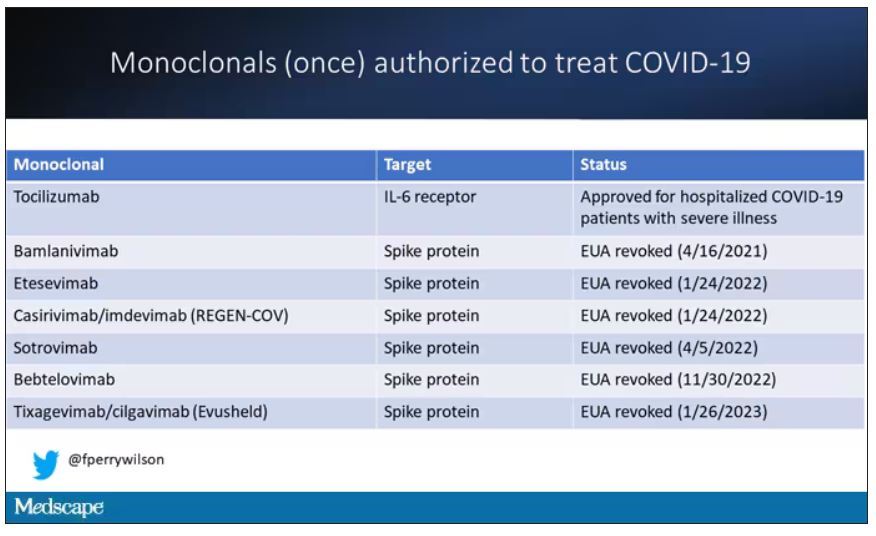

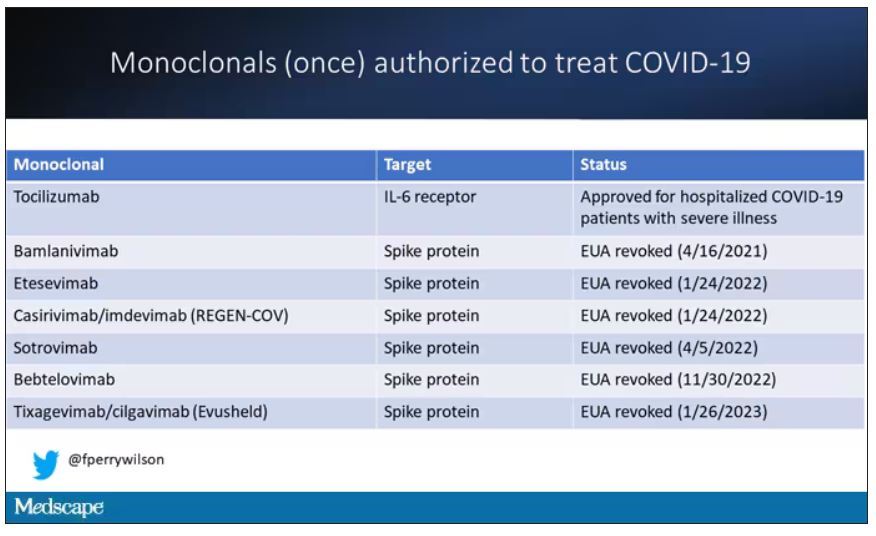

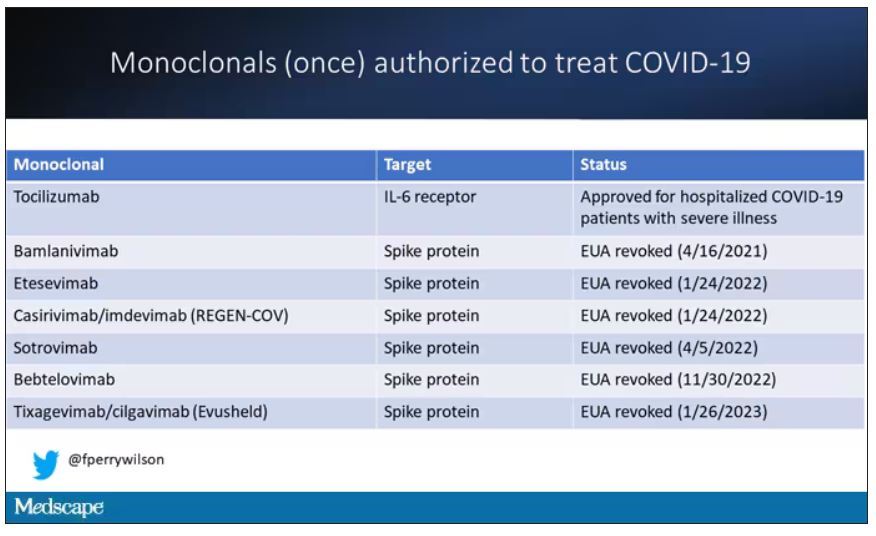

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

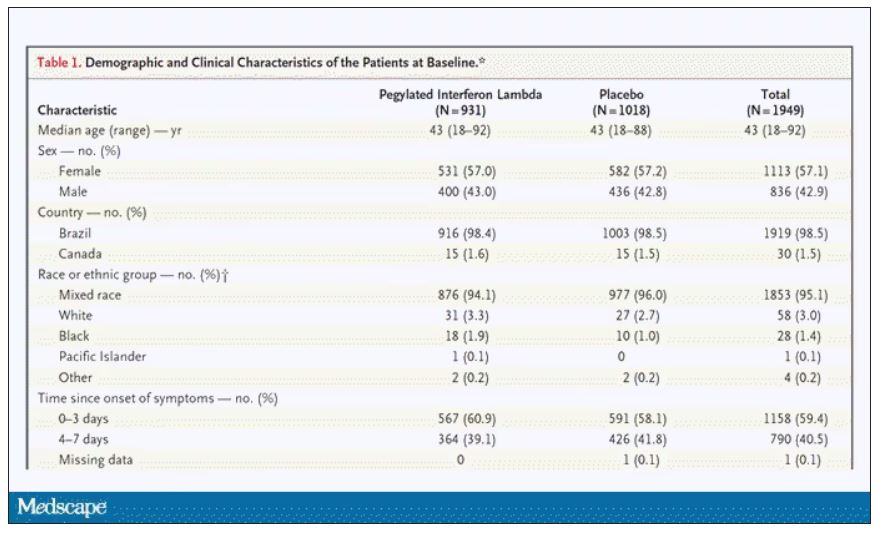

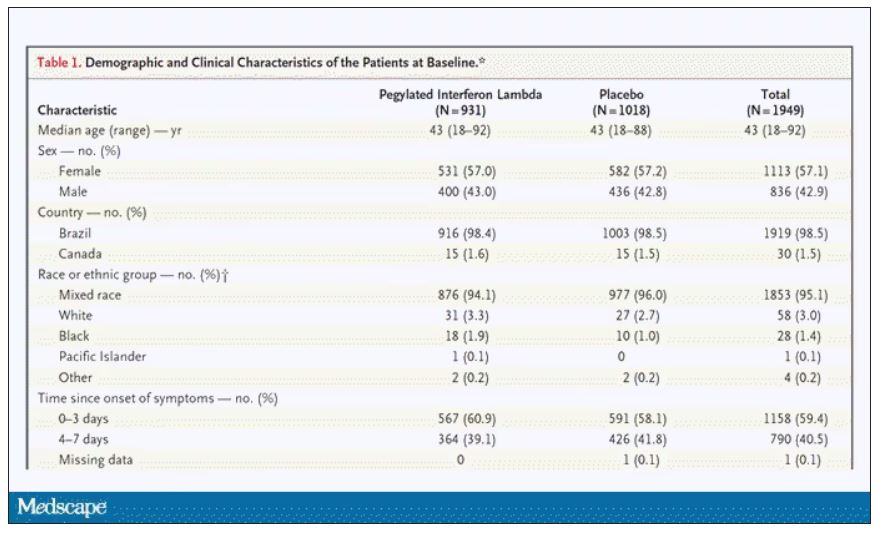

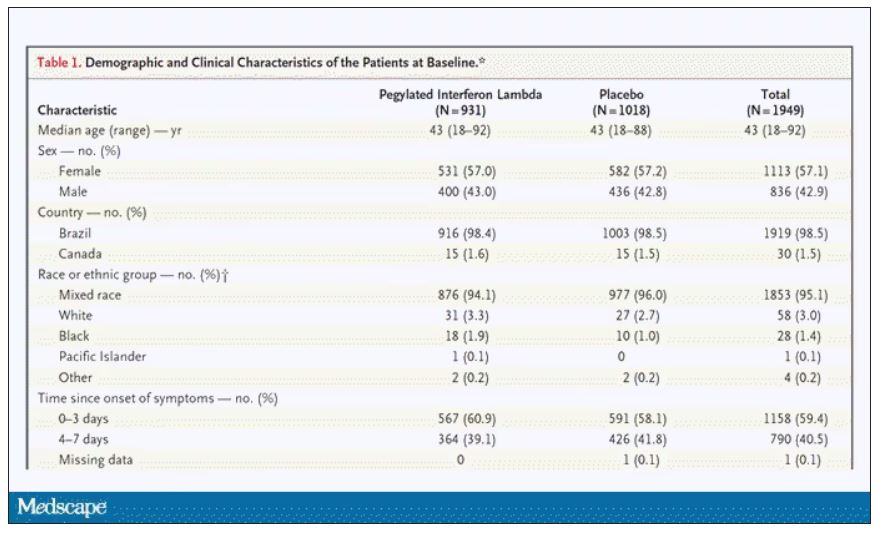

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

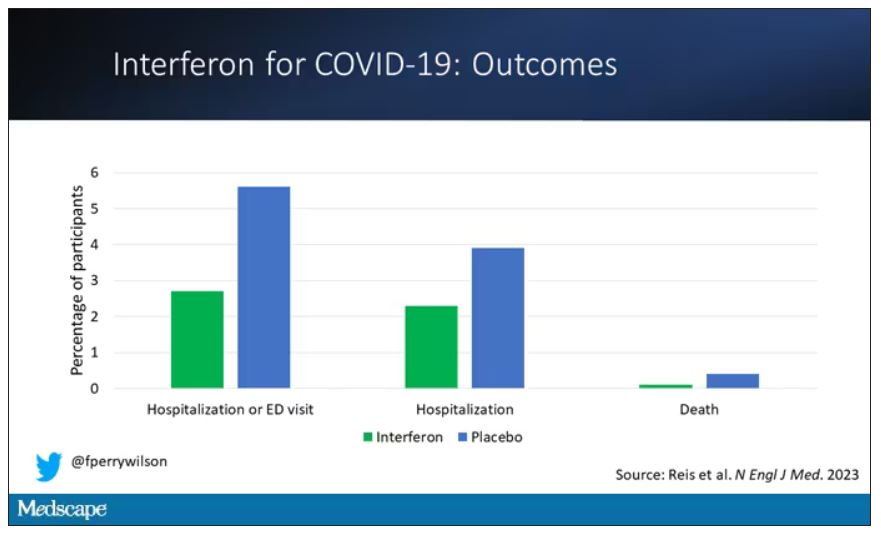

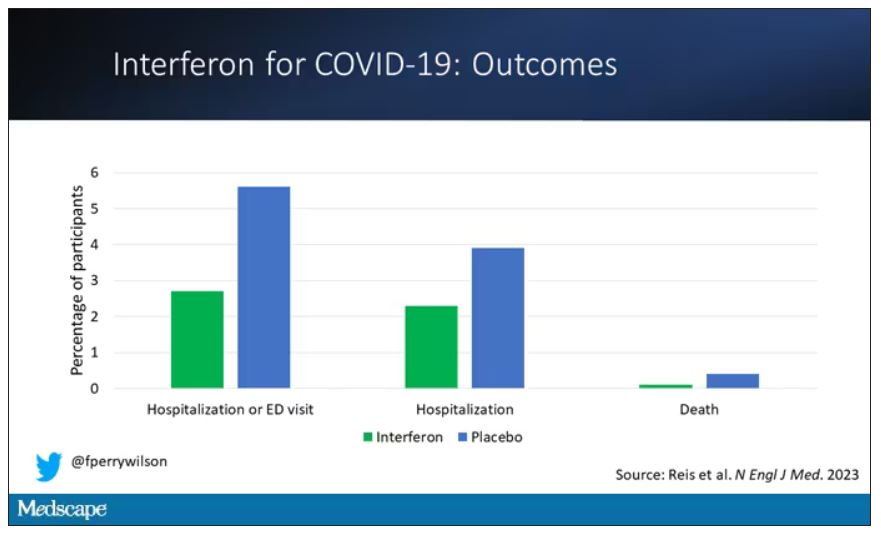

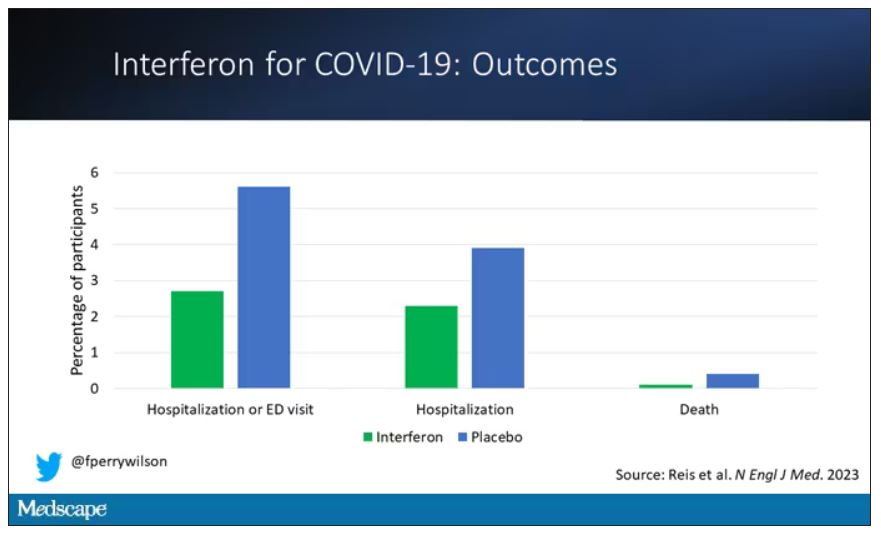

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

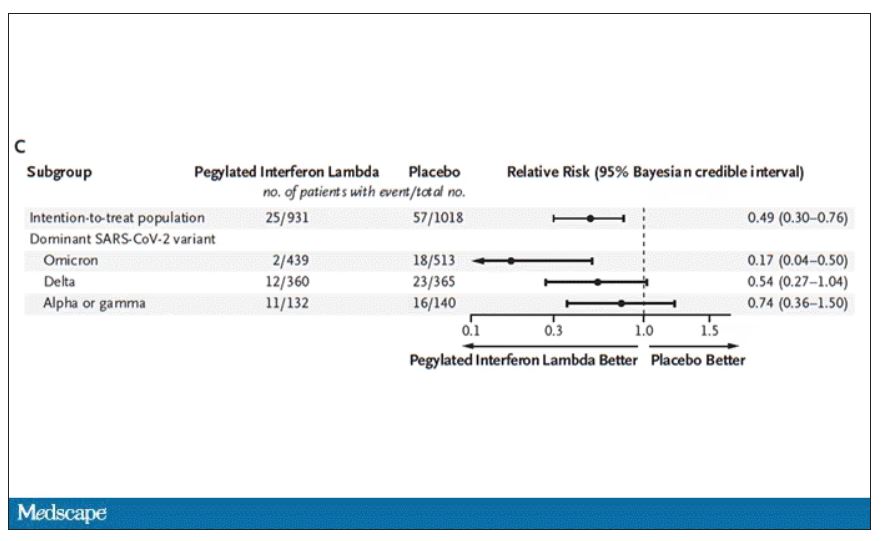

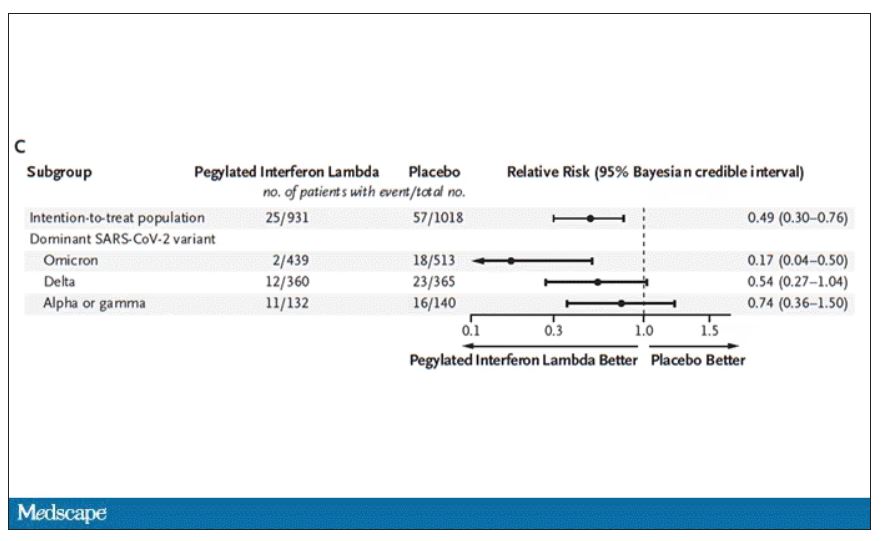

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

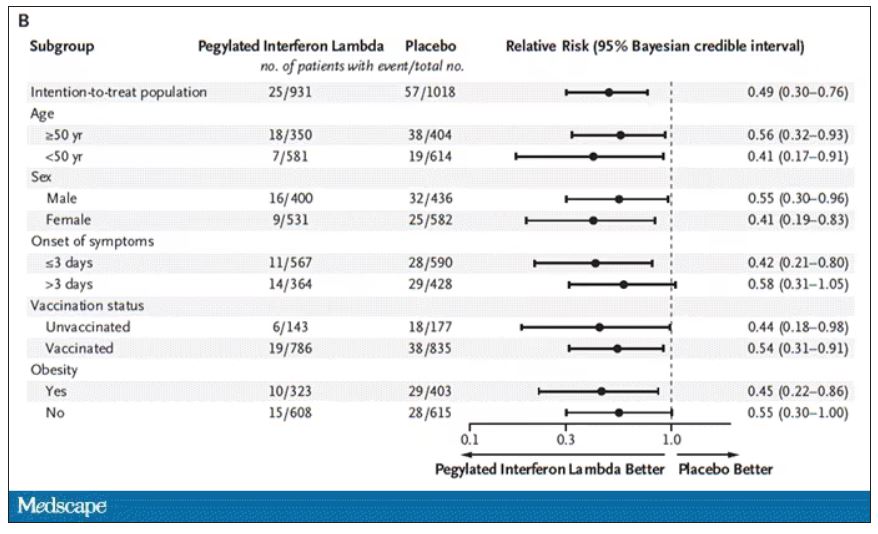

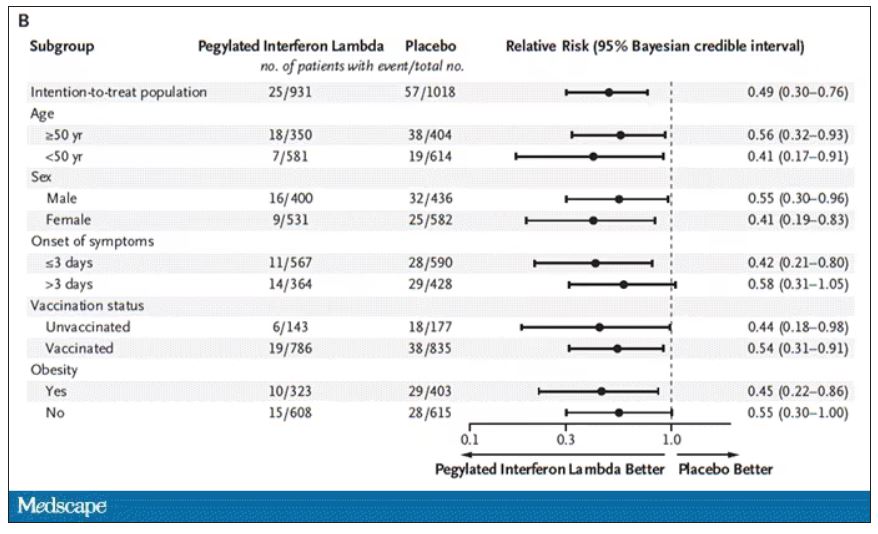

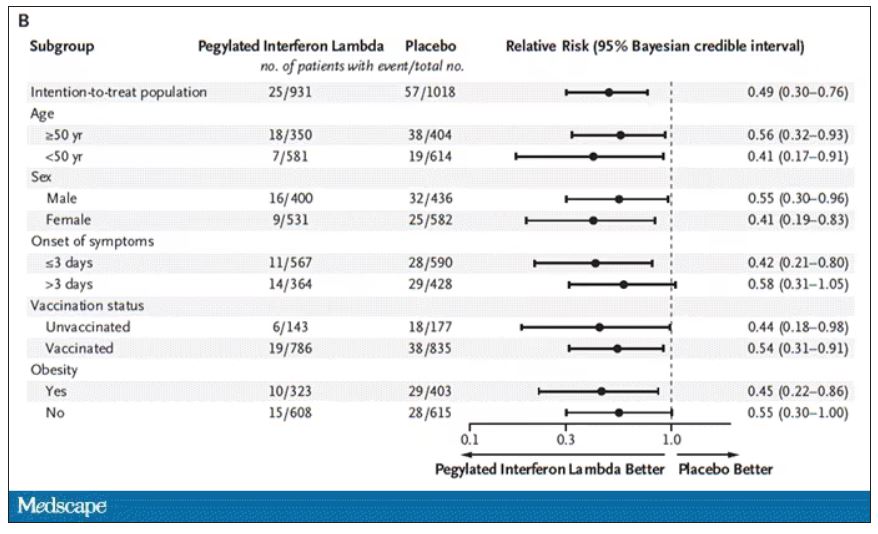

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

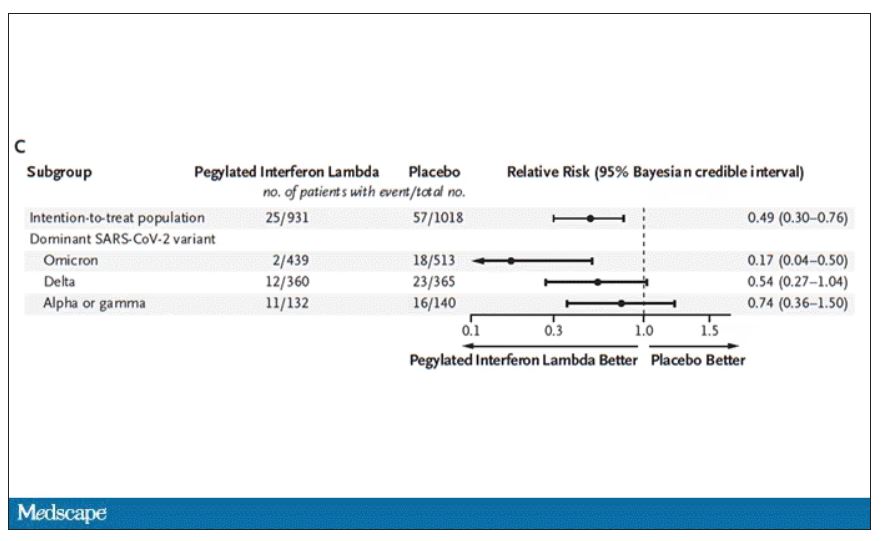

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

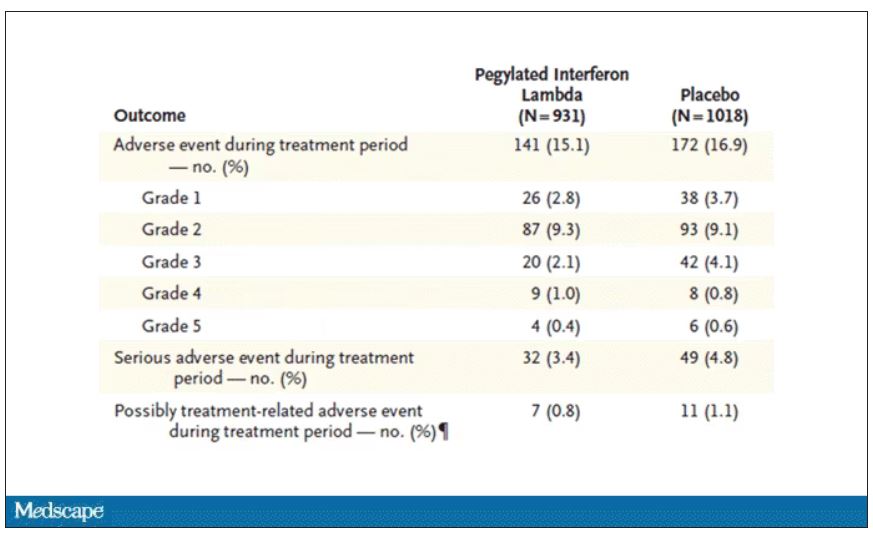

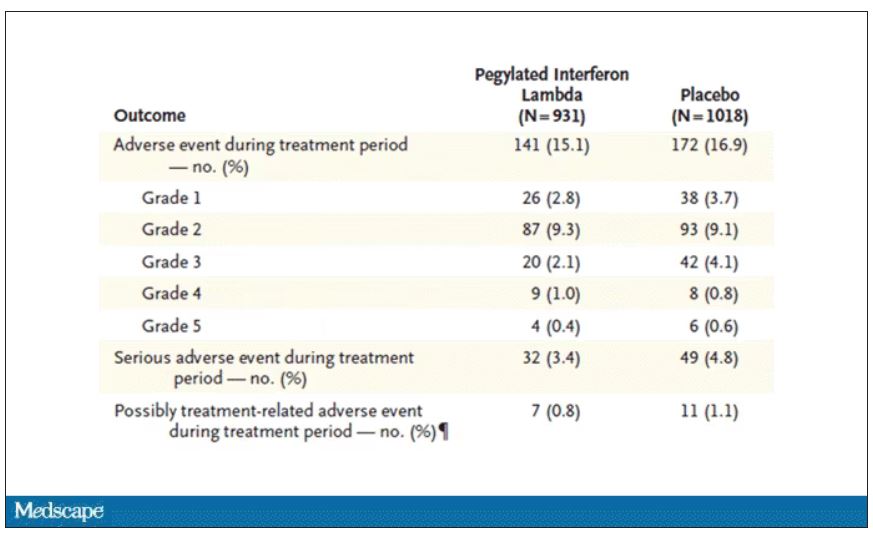

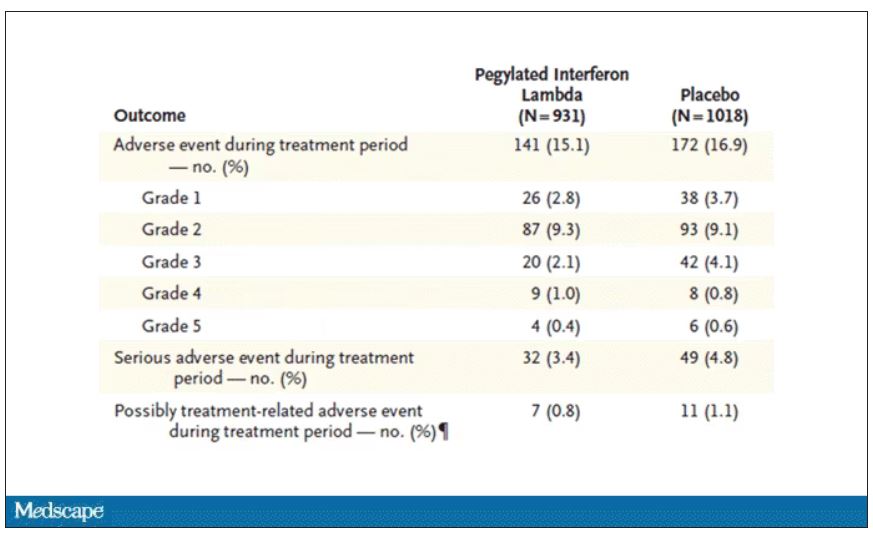

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don’t seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We’ve got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I’m sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let’s talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

In this study, 1,951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 mcg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

The primary outcome – hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID – was 50% lower in the interferon group.

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There’s a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn’t surprising; we’ve seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don’t see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I’d love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

Dr. Perry Wilson is associate professor, department of medicine, and director, Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

We should all have more Shakespeare in our lives. Yeah, yeah, Shakespeare is meant to be played, not read, and it can be a struggle to herd teenagers through the Bard’s interesting and bloody tragedies, but even a perfunctory reading of “The Merchant of Venice” would hopefully have prevented the dystopian nightmare Massachusetts has presented us with today.

The United States has a massive shortage of donor organs. This is an unfortunate truth. So, to combat this issue, a pair of Massachusetts congresspeople have proposed HD 3822, which would allow prisoners to donate organs and/or bone marrow (a pound of flesh, so to speak) in exchange for up to a year in reduced prison time. Yes, that’s right. Give up pieces of yourself and the state of Massachusetts will deign to reduce your long prison sentence.

Oh, and before you dismiss this as typical Republican antics, the bill was sponsored by two Democrats, and in a statement one of them hoped to address racial disparities in organ donation, as people of color are much less likely to receive organs. Never mind that Black people are imprisoned at a much higher rate than Whites.

Yeah, this whole thing is what people in the business like to call an ethical disaster.

Fortunately, the bill will likely never be passed and it’s probably illegal anyway. A federal law from 1984 (how’s that for a coincidence) prevents people from donating organs for use in human transplantation in exchange for “valuable consideration.” In other words, you can’t sell your organs for profit, and in this case, reducing prison time would probably count as valuable consideration in the eyes of the courts.

Oh, and in case you’ve never read Merchant of Venice, Shylock, the character looking for the pound of flesh as payment for a debt? He’s the villain. In fact, it’s pretty safe to say that anyone looking to extract payment from human dismemberment is probably the bad guy of the story. Apparently that wasn’t clear.

How do you stop a fungi? With a deadly guy

Thanks to the new HBO series “The Last of Us,” there’s been a lot of talk about the upcoming fungi-pocalypse, as the show depicts the real-life “zombie fungus” Cordyceps turning humans into, you know, zombies.

No need to worry, ladies and gentleman, because science has discovered a way to turn back the fungal horde. A heroic, and environmentally friendly, alternative to chemical pesticides “in the fight against resistant fungi [that] are now resistant to antimycotics – partly because they are used in large quantities in agricultural fields,” investigators at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology in Jena, Germany, said in a written statement.

We are, of course, talking about Keanu Reeves. Wait a second. He’s not even in “The Last of Us.” Sorry folks, we are being told that it really is Keanu Reeves. Our champion in the inevitable fungal pandemic is movie star Keanu Reeves. Sort of. It’s actually keanumycin, a substance produced by bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas.

Really? Keanumycin? “The lipopeptides kill so efficiently that we named them after Keanu Reeves because he, too, is extremely deadly in his roles,” lead author Sebastian Götze, PhD, explained.

Dr. Götze and his associates had been working with pseudomonads for quite a while before they were able to isolate the toxins responsible for their ability to kill amoebae, which resemble fungi in some characteristics. When then finally tried the keanumycin against gray mold rot on hydrangea leaves, the intensely contemplative star of “The Matrix” and “John Wick” – sorry, wrong Keanu – the bacterial derivative significantly inhibited growth of the fungus, they said.

Additional testing has shown that keanumycin is not highly toxic to human cells and is effective against fungi such as Candida albicans in very low concentrations, which makes it a good candidate for future pharmaceutical development.

To that news there can be only one response from the substance’s namesake.

High fat, bye parasites

Fat. Fat. Fat. Seems like everyone is trying to avoid it these days, but fat may be good thing when it comes to weaseling out a parasite.

The parasite in this case is the whipworm, aka Trichuris trichiura. You can find this guy in the intestines of millions of people, where it causes long-lasting infections. Yikes … Researchers have found that the plan of attack to get rid of this invasive species is to boost the immune system, but instead of vitamin C and zinc it’s fat they’re pumping in. Yes, fat.

The developing countries with poor sewage that are at the highest risk for contracting parasites such as this also are among those where people ingest cheaper diets that are generally higher in fat. The investigators were interested to see how a high-fat diet would affect immune responses to the whipworms.

And, as with almost everything else, the researchers turned to mice, which were introduced to a closely related species, Trichuris muris.

A high-fat diet, rather than obesity itself, increases a molecule on T-helper cells called ST2, and this allows an increased T-helper 2 response, effectively giving eviction notices to the parasites in the intestinal lining.

To say the least, the researchers were surprised since “high-fat diets are mostly associated with increased pathology during disease,” said senior author Richard Grencis, PhD, of the University of Manchester (England), who noted that ST2 is not normally triggered with a standard diet in mice but the high-fat diet gave it a boost and an “alternate pathway” out.

Now before you start ordering extra-large fries at the drive-through to keep the whipworms away, the researchers added that they “have previously published that weight loss can aid the expulsion of a different gut parasite worm.” Figures.

Once again, though, signs are pointing to the gut for improved health.

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

We should all have more Shakespeare in our lives. Yeah, yeah, Shakespeare is meant to be played, not read, and it can be a struggle to herd teenagers through the Bard’s interesting and bloody tragedies, but even a perfunctory reading of “The Merchant of Venice” would hopefully have prevented the dystopian nightmare Massachusetts has presented us with today.

The United States has a massive shortage of donor organs. This is an unfortunate truth. So, to combat this issue, a pair of Massachusetts congresspeople have proposed HD 3822, which would allow prisoners to donate organs and/or bone marrow (a pound of flesh, so to speak) in exchange for up to a year in reduced prison time. Yes, that’s right. Give up pieces of yourself and the state of Massachusetts will deign to reduce your long prison sentence.

Oh, and before you dismiss this as typical Republican antics, the bill was sponsored by two Democrats, and in a statement one of them hoped to address racial disparities in organ donation, as people of color are much less likely to receive organs. Never mind that Black people are imprisoned at a much higher rate than Whites.

Yeah, this whole thing is what people in the business like to call an ethical disaster.

Fortunately, the bill will likely never be passed and it’s probably illegal anyway. A federal law from 1984 (how’s that for a coincidence) prevents people from donating organs for use in human transplantation in exchange for “valuable consideration.” In other words, you can’t sell your organs for profit, and in this case, reducing prison time would probably count as valuable consideration in the eyes of the courts.

Oh, and in case you’ve never read Merchant of Venice, Shylock, the character looking for the pound of flesh as payment for a debt? He’s the villain. In fact, it’s pretty safe to say that anyone looking to extract payment from human dismemberment is probably the bad guy of the story. Apparently that wasn’t clear.

How do you stop a fungi? With a deadly guy

Thanks to the new HBO series “The Last of Us,” there’s been a lot of talk about the upcoming fungi-pocalypse, as the show depicts the real-life “zombie fungus” Cordyceps turning humans into, you know, zombies.

No need to worry, ladies and gentleman, because science has discovered a way to turn back the fungal horde. A heroic, and environmentally friendly, alternative to chemical pesticides “in the fight against resistant fungi [that] are now resistant to antimycotics – partly because they are used in large quantities in agricultural fields,” investigators at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology in Jena, Germany, said in a written statement.

We are, of course, talking about Keanu Reeves. Wait a second. He’s not even in “The Last of Us.” Sorry folks, we are being told that it really is Keanu Reeves. Our champion in the inevitable fungal pandemic is movie star Keanu Reeves. Sort of. It’s actually keanumycin, a substance produced by bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas.

Really? Keanumycin? “The lipopeptides kill so efficiently that we named them after Keanu Reeves because he, too, is extremely deadly in his roles,” lead author Sebastian Götze, PhD, explained.

Dr. Götze and his associates had been working with pseudomonads for quite a while before they were able to isolate the toxins responsible for their ability to kill amoebae, which resemble fungi in some characteristics. When then finally tried the keanumycin against gray mold rot on hydrangea leaves, the intensely contemplative star of “The Matrix” and “John Wick” – sorry, wrong Keanu – the bacterial derivative significantly inhibited growth of the fungus, they said.

Additional testing has shown that keanumycin is not highly toxic to human cells and is effective against fungi such as Candida albicans in very low concentrations, which makes it a good candidate for future pharmaceutical development.

To that news there can be only one response from the substance’s namesake.

High fat, bye parasites

Fat. Fat. Fat. Seems like everyone is trying to avoid it these days, but fat may be good thing when it comes to weaseling out a parasite.

The parasite in this case is the whipworm, aka Trichuris trichiura. You can find this guy in the intestines of millions of people, where it causes long-lasting infections. Yikes … Researchers have found that the plan of attack to get rid of this invasive species is to boost the immune system, but instead of vitamin C and zinc it’s fat they’re pumping in. Yes, fat.

The developing countries with poor sewage that are at the highest risk for contracting parasites such as this also are among those where people ingest cheaper diets that are generally higher in fat. The investigators were interested to see how a high-fat diet would affect immune responses to the whipworms.

And, as with almost everything else, the researchers turned to mice, which were introduced to a closely related species, Trichuris muris.

A high-fat diet, rather than obesity itself, increases a molecule on T-helper cells called ST2, and this allows an increased T-helper 2 response, effectively giving eviction notices to the parasites in the intestinal lining.

To say the least, the researchers were surprised since “high-fat diets are mostly associated with increased pathology during disease,” said senior author Richard Grencis, PhD, of the University of Manchester (England), who noted that ST2 is not normally triggered with a standard diet in mice but the high-fat diet gave it a boost and an “alternate pathway” out.

Now before you start ordering extra-large fries at the drive-through to keep the whipworms away, the researchers added that they “have previously published that weight loss can aid the expulsion of a different gut parasite worm.” Figures.

Once again, though, signs are pointing to the gut for improved health.

Pound of flesh buys less prison time

We should all have more Shakespeare in our lives. Yeah, yeah, Shakespeare is meant to be played, not read, and it can be a struggle to herd teenagers through the Bard’s interesting and bloody tragedies, but even a perfunctory reading of “The Merchant of Venice” would hopefully have prevented the dystopian nightmare Massachusetts has presented us with today.

The United States has a massive shortage of donor organs. This is an unfortunate truth. So, to combat this issue, a pair of Massachusetts congresspeople have proposed HD 3822, which would allow prisoners to donate organs and/or bone marrow (a pound of flesh, so to speak) in exchange for up to a year in reduced prison time. Yes, that’s right. Give up pieces of yourself and the state of Massachusetts will deign to reduce your long prison sentence.

Oh, and before you dismiss this as typical Republican antics, the bill was sponsored by two Democrats, and in a statement one of them hoped to address racial disparities in organ donation, as people of color are much less likely to receive organs. Never mind that Black people are imprisoned at a much higher rate than Whites.

Yeah, this whole thing is what people in the business like to call an ethical disaster.

Fortunately, the bill will likely never be passed and it’s probably illegal anyway. A federal law from 1984 (how’s that for a coincidence) prevents people from donating organs for use in human transplantation in exchange for “valuable consideration.” In other words, you can’t sell your organs for profit, and in this case, reducing prison time would probably count as valuable consideration in the eyes of the courts.

Oh, and in case you’ve never read Merchant of Venice, Shylock, the character looking for the pound of flesh as payment for a debt? He’s the villain. In fact, it’s pretty safe to say that anyone looking to extract payment from human dismemberment is probably the bad guy of the story. Apparently that wasn’t clear.

How do you stop a fungi? With a deadly guy

Thanks to the new HBO series “The Last of Us,” there’s been a lot of talk about the upcoming fungi-pocalypse, as the show depicts the real-life “zombie fungus” Cordyceps turning humans into, you know, zombies.

No need to worry, ladies and gentleman, because science has discovered a way to turn back the fungal horde. A heroic, and environmentally friendly, alternative to chemical pesticides “in the fight against resistant fungi [that] are now resistant to antimycotics – partly because they are used in large quantities in agricultural fields,” investigators at the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology in Jena, Germany, said in a written statement.

We are, of course, talking about Keanu Reeves. Wait a second. He’s not even in “The Last of Us.” Sorry folks, we are being told that it really is Keanu Reeves. Our champion in the inevitable fungal pandemic is movie star Keanu Reeves. Sort of. It’s actually keanumycin, a substance produced by bacteria of the genus Pseudomonas.

Really? Keanumycin? “The lipopeptides kill so efficiently that we named them after Keanu Reeves because he, too, is extremely deadly in his roles,” lead author Sebastian Götze, PhD, explained.

Dr. Götze and his associates had been working with pseudomonads for quite a while before they were able to isolate the toxins responsible for their ability to kill amoebae, which resemble fungi in some characteristics. When then finally tried the keanumycin against gray mold rot on hydrangea leaves, the intensely contemplative star of “The Matrix” and “John Wick” – sorry, wrong Keanu – the bacterial derivative significantly inhibited growth of the fungus, they said.

Additional testing has shown that keanumycin is not highly toxic to human cells and is effective against fungi such as Candida albicans in very low concentrations, which makes it a good candidate for future pharmaceutical development.

To that news there can be only one response from the substance’s namesake.

High fat, bye parasites

Fat. Fat. Fat. Seems like everyone is trying to avoid it these days, but fat may be good thing when it comes to weaseling out a parasite.

The parasite in this case is the whipworm, aka Trichuris trichiura. You can find this guy in the intestines of millions of people, where it causes long-lasting infections. Yikes … Researchers have found that the plan of attack to get rid of this invasive species is to boost the immune system, but instead of vitamin C and zinc it’s fat they’re pumping in. Yes, fat.

The developing countries with poor sewage that are at the highest risk for contracting parasites such as this also are among those where people ingest cheaper diets that are generally higher in fat. The investigators were interested to see how a high-fat diet would affect immune responses to the whipworms.

And, as with almost everything else, the researchers turned to mice, which were introduced to a closely related species, Trichuris muris.

A high-fat diet, rather than obesity itself, increases a molecule on T-helper cells called ST2, and this allows an increased T-helper 2 response, effectively giving eviction notices to the parasites in the intestinal lining.

To say the least, the researchers were surprised since “high-fat diets are mostly associated with increased pathology during disease,” said senior author Richard Grencis, PhD, of the University of Manchester (England), who noted that ST2 is not normally triggered with a standard diet in mice but the high-fat diet gave it a boost and an “alternate pathway” out.

Now before you start ordering extra-large fries at the drive-through to keep the whipworms away, the researchers added that they “have previously published that weight loss can aid the expulsion of a different gut parasite worm.” Figures.

Once again, though, signs are pointing to the gut for improved health.

Maternal COVID-19 vaccine curbs infant infection

a new study shows.

Previous research has confirmed that COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies following maternal vaccination or maternal COVID-19 infection are present in umbilical cord blood, breast milk, and infant serum specimens, wrote Sarah C.J. Jorgensen, PharmD, MPH, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues in their article published in The BMJ.

In the study, the researchers identified maternal and newborn pairs using administrative databases from Canada. The study population included 8,809 infants aged younger than 6 months who were born between May 7, 2021, and March 31, 2022, and who underwent testing for COVID-19 between May 7, 2021, and September 5, 2022.

Maternal vaccination with the primary COVID-19 mRNA monovalent vaccine series was defined as two vaccine doses administered up to 14 days before delivery, with at least one of the doses after the conception date.

Maternal vaccination with the primary series plus one booster was defined as three doses administered up to 14 days before delivery, with at least one of these doses after the conception date.

The primary outcome was the presence of delta or omicron COVID-19 infection or hospital admission of the infants.

The study population included 99 COVID-19 cases with the delta variant (with 4,365 controls) and 1,501 cases with the omicron variant (with 4,847 controls).

Overall, the vaccine effectiveness of maternal doses was 95% against delta infection and 45% against omicron.

The effectiveness against hospital admission in cases of delta and omicron variants were 97% and 53%, respectively.

The effectiveness of three doses was 73% against omicron infant infection and 80% against omicron-related infant hospitalization. Data were not available for the effectiveness of three doses against the delta variant.

The effectiveness of two doses of vaccine against infant omicron infection was highest when mothers received the second dose during the third trimester of pregnancy, compared with during the first trimester or second trimester (53% vs. 47% and 53% vs. 37%, respectively).

Vaccine effectiveness with two doses against infant infection from omicron was highest in the first 8 weeks of life (57%), then decreased to 40% among infants after 16 weeks of age.

Although the study was not designed to assess the mechanism of action of the impact of maternal vaccination on infants, the current study results were consistent with other recent studies showing a reduction in infections and hospitalizations among infants whose mothers received COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the potential unmeasured confounders not available in databases, such as whether infants were breastfed, the researchers noted. Other limitations included a lack of data on home test results and the inability to assess the waning impact of the vaccine effectiveness against the delta variant because of the small number of delta cases, they said. However, the results suggest that the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy was moderately to highly effective for protection against omicron and delta infection and infection-related hospitalization – especially during the first 8 weeks of life.

Effectiveness is encouraging, but updates are needed

The effectiveness of maternal vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection and related hospitalizations in infants is promising, especially since those younger than 6 months have no other source of vaccine protection against COVID-19 infection, wrote Dana Danino, MD, of Soroka University Medical Center, Israel, and Ilan Youngster, MD, of Shamir Medical Center, Israel, in an accompanying editorial also published in The BMJ.

They also noted that maternal vaccination during pregnancy is an established method of protecting infants from infections such as influenza and pertussis.

Data from previous studies show that most infants whose mothers were vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy retained maternal antibodies at 6 months, “but evidence for protection against neonatal COVID-19 infection has been deficient,” they said.

The current study findings support the value of vaccination during pregnancy, and the findings were strengthened by the large study population, the editorialists wrote. However, whether the same effectiveness holds for other COVID-19 strains such as BQ.1, BQ.1.1, BF.7, XBB, and XBB.1 remains unknown, they said.

Other areas in need of exploration include the optimal timing of vaccination during pregnancy, the protective effects of a bivalent mRNA vaccine (vs. the primary monovalent vaccine in the current study), and the potential benefits of additional boosters, they added.

“Although Jorgenson and colleagues’ study reinforces the value of maternal vaccination against COVID-19 during pregnancy, more studies are needed to better inform vaccination recommendations in an evolving landscape of new SARS-CoV-2 strains and novel vaccines,” the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-term Care; the study also received funding from the Canadian Immunization Research Network and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Dr. Jorgensen and the editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This article was updated on 3/2/2023.

a new study shows.

Previous research has confirmed that COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies following maternal vaccination or maternal COVID-19 infection are present in umbilical cord blood, breast milk, and infant serum specimens, wrote Sarah C.J. Jorgensen, PharmD, MPH, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues in their article published in The BMJ.

In the study, the researchers identified maternal and newborn pairs using administrative databases from Canada. The study population included 8,809 infants aged younger than 6 months who were born between May 7, 2021, and March 31, 2022, and who underwent testing for COVID-19 between May 7, 2021, and September 5, 2022.

Maternal vaccination with the primary COVID-19 mRNA monovalent vaccine series was defined as two vaccine doses administered up to 14 days before delivery, with at least one of the doses after the conception date.

Maternal vaccination with the primary series plus one booster was defined as three doses administered up to 14 days before delivery, with at least one of these doses after the conception date.

The primary outcome was the presence of delta or omicron COVID-19 infection or hospital admission of the infants.

The study population included 99 COVID-19 cases with the delta variant (with 4,365 controls) and 1,501 cases with the omicron variant (with 4,847 controls).

Overall, the vaccine effectiveness of maternal doses was 95% against delta infection and 45% against omicron.

The effectiveness against hospital admission in cases of delta and omicron variants were 97% and 53%, respectively.

The effectiveness of three doses was 73% against omicron infant infection and 80% against omicron-related infant hospitalization. Data were not available for the effectiveness of three doses against the delta variant.

The effectiveness of two doses of vaccine against infant omicron infection was highest when mothers received the second dose during the third trimester of pregnancy, compared with during the first trimester or second trimester (53% vs. 47% and 53% vs. 37%, respectively).

Vaccine effectiveness with two doses against infant infection from omicron was highest in the first 8 weeks of life (57%), then decreased to 40% among infants after 16 weeks of age.

Although the study was not designed to assess the mechanism of action of the impact of maternal vaccination on infants, the current study results were consistent with other recent studies showing a reduction in infections and hospitalizations among infants whose mothers received COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the potential unmeasured confounders not available in databases, such as whether infants were breastfed, the researchers noted. Other limitations included a lack of data on home test results and the inability to assess the waning impact of the vaccine effectiveness against the delta variant because of the small number of delta cases, they said. However, the results suggest that the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy was moderately to highly effective for protection against omicron and delta infection and infection-related hospitalization – especially during the first 8 weeks of life.

Effectiveness is encouraging, but updates are needed

The effectiveness of maternal vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection and related hospitalizations in infants is promising, especially since those younger than 6 months have no other source of vaccine protection against COVID-19 infection, wrote Dana Danino, MD, of Soroka University Medical Center, Israel, and Ilan Youngster, MD, of Shamir Medical Center, Israel, in an accompanying editorial also published in The BMJ.

They also noted that maternal vaccination during pregnancy is an established method of protecting infants from infections such as influenza and pertussis.

Data from previous studies show that most infants whose mothers were vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy retained maternal antibodies at 6 months, “but evidence for protection against neonatal COVID-19 infection has been deficient,” they said.

The current study findings support the value of vaccination during pregnancy, and the findings were strengthened by the large study population, the editorialists wrote. However, whether the same effectiveness holds for other COVID-19 strains such as BQ.1, BQ.1.1, BF.7, XBB, and XBB.1 remains unknown, they said.

Other areas in need of exploration include the optimal timing of vaccination during pregnancy, the protective effects of a bivalent mRNA vaccine (vs. the primary monovalent vaccine in the current study), and the potential benefits of additional boosters, they added.

“Although Jorgenson and colleagues’ study reinforces the value of maternal vaccination against COVID-19 during pregnancy, more studies are needed to better inform vaccination recommendations in an evolving landscape of new SARS-CoV-2 strains and novel vaccines,” the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-term Care; the study also received funding from the Canadian Immunization Research Network and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Dr. Jorgensen and the editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This article was updated on 3/2/2023.

a new study shows.

Previous research has confirmed that COVID-19 neutralizing antibodies following maternal vaccination or maternal COVID-19 infection are present in umbilical cord blood, breast milk, and infant serum specimens, wrote Sarah C.J. Jorgensen, PharmD, MPH, of the University of Toronto, and colleagues in their article published in The BMJ.

In the study, the researchers identified maternal and newborn pairs using administrative databases from Canada. The study population included 8,809 infants aged younger than 6 months who were born between May 7, 2021, and March 31, 2022, and who underwent testing for COVID-19 between May 7, 2021, and September 5, 2022.

Maternal vaccination with the primary COVID-19 mRNA monovalent vaccine series was defined as two vaccine doses administered up to 14 days before delivery, with at least one of the doses after the conception date.

Maternal vaccination with the primary series plus one booster was defined as three doses administered up to 14 days before delivery, with at least one of these doses after the conception date.

The primary outcome was the presence of delta or omicron COVID-19 infection or hospital admission of the infants.

The study population included 99 COVID-19 cases with the delta variant (with 4,365 controls) and 1,501 cases with the omicron variant (with 4,847 controls).

Overall, the vaccine effectiveness of maternal doses was 95% against delta infection and 45% against omicron.

The effectiveness against hospital admission in cases of delta and omicron variants were 97% and 53%, respectively.

The effectiveness of three doses was 73% against omicron infant infection and 80% against omicron-related infant hospitalization. Data were not available for the effectiveness of three doses against the delta variant.

The effectiveness of two doses of vaccine against infant omicron infection was highest when mothers received the second dose during the third trimester of pregnancy, compared with during the first trimester or second trimester (53% vs. 47% and 53% vs. 37%, respectively).

Vaccine effectiveness with two doses against infant infection from omicron was highest in the first 8 weeks of life (57%), then decreased to 40% among infants after 16 weeks of age.

Although the study was not designed to assess the mechanism of action of the impact of maternal vaccination on infants, the current study results were consistent with other recent studies showing a reduction in infections and hospitalizations among infants whose mothers received COVID-19 vaccines during pregnancy, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The findings were limited by several factors including the potential unmeasured confounders not available in databases, such as whether infants were breastfed, the researchers noted. Other limitations included a lack of data on home test results and the inability to assess the waning impact of the vaccine effectiveness against the delta variant because of the small number of delta cases, they said. However, the results suggest that the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy was moderately to highly effective for protection against omicron and delta infection and infection-related hospitalization – especially during the first 8 weeks of life.

Effectiveness is encouraging, but updates are needed

The effectiveness of maternal vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection and related hospitalizations in infants is promising, especially since those younger than 6 months have no other source of vaccine protection against COVID-19 infection, wrote Dana Danino, MD, of Soroka University Medical Center, Israel, and Ilan Youngster, MD, of Shamir Medical Center, Israel, in an accompanying editorial also published in The BMJ.

They also noted that maternal vaccination during pregnancy is an established method of protecting infants from infections such as influenza and pertussis.

Data from previous studies show that most infants whose mothers were vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy retained maternal antibodies at 6 months, “but evidence for protection against neonatal COVID-19 infection has been deficient,” they said.

The current study findings support the value of vaccination during pregnancy, and the findings were strengthened by the large study population, the editorialists wrote. However, whether the same effectiveness holds for other COVID-19 strains such as BQ.1, BQ.1.1, BF.7, XBB, and XBB.1 remains unknown, they said.

Other areas in need of exploration include the optimal timing of vaccination during pregnancy, the protective effects of a bivalent mRNA vaccine (vs. the primary monovalent vaccine in the current study), and the potential benefits of additional boosters, they added.

“Although Jorgenson and colleagues’ study reinforces the value of maternal vaccination against COVID-19 during pregnancy, more studies are needed to better inform vaccination recommendations in an evolving landscape of new SARS-CoV-2 strains and novel vaccines,” the editorialists concluded.

The study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-term Care; the study also received funding from the Canadian Immunization Research Network and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Dr. Jorgensen and the editorialists had no financial conflicts to disclose.

*This article was updated on 3/2/2023.

FROM THE BMJ

IVF-conceived children show strong developmental performance

In vitro fertilization has been around long enough that researchers can now compare developmental and academic achievements between these children and peers at school age.

Amber Kennedy, MBBS, and colleagues did just that. They found little difference in these milestones between a total of 11,059 IVF-conceived children and 401,654 spontaneously conceived children in a new study.

“Parents considering IVF and health care professionals can be reassured that the school age developmental and educational outcomes of IVF-conceived children are equivalent to their peers,” said Dr. Kennedy, lead author and obstetrician and gynecologist at Mercy Hospital for Women at the University of Melbourne.

The findings were published online in PLOS Medicine.

“Overall, we know that children born through IVF are doing fine in terms of health, but also emotionally and cognitively. So I wasn’t surprised. I live in this world,” said Ariadna Cymet Lanski, PsyD, chair of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Mental Health Professional Group, who was not affiliated with the study.

Some previous researchers linked conception via IVF to an increased risk of congenital abnormalities, autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and intellectual disability.

Asked why the current study did not find increased risks, Dr. Kennedy said, “Our population included a relatively recent birth cohort, which may explain some differences from previous studies as IVF practices have evolved over time.”

An estimated 8 million people worldwide have been conceived through IVF since the first birth in 1978, the researchers said. In Australia, this has grown from 2% of births in the year 2000 to now nearly 5% or 1 in 20 live births, Dr. Kennedy noted. “Consequently, it is important to understand the longer-term outcomes for this population of children.”

Along with senior author Anthea Lindquist, MBBS, Dr. Kennedy and colleagues studied 585,659 single births in Victoria, Australia, between 2005 and 2014. They did not include multiple births such as twins or triplets.

The investigators compared 4,697 children conceived via IVF and 168,503 others conceived spontaneously using a standard developmental measure, the Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC). They also assessed 8,976 children in the IVF group and 333,335 other children on a standard educational measure, the National Assessment Program–Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN).

For example, the developmental census measures developmental vulnerability. Dr. Kennedy and colleagues found a 0.3% difference in favor of IVF-conceived children, which statistically was no different than zero.

Similarly, the researchers reported that IVF conception had essentially no effect on overall the literacy score, with an adjusted average difference of 0.03.

Dr. Lanski said the results should be reassuring for people considering IVF. “I can see the value of the study.” The findings “probably brings a lot of comfort ... if you want to build a family, and medically this is what’s recommended.”

Not all IVF techniques are the same, and the researchers want to take a deeper dive to evaluate any distinctions among them. For example, Dr. Kennedy said, “We plan to investigate the same school-aged outcomes after specific IVF-associated techniques.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In vitro fertilization has been around long enough that researchers can now compare developmental and academic achievements between these children and peers at school age.

Amber Kennedy, MBBS, and colleagues did just that. They found little difference in these milestones between a total of 11,059 IVF-conceived children and 401,654 spontaneously conceived children in a new study.

“Parents considering IVF and health care professionals can be reassured that the school age developmental and educational outcomes of IVF-conceived children are equivalent to their peers,” said Dr. Kennedy, lead author and obstetrician and gynecologist at Mercy Hospital for Women at the University of Melbourne.

The findings were published online in PLOS Medicine.

“Overall, we know that children born through IVF are doing fine in terms of health, but also emotionally and cognitively. So I wasn’t surprised. I live in this world,” said Ariadna Cymet Lanski, PsyD, chair of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Mental Health Professional Group, who was not affiliated with the study.

Some previous researchers linked conception via IVF to an increased risk of congenital abnormalities, autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and intellectual disability.

Asked why the current study did not find increased risks, Dr. Kennedy said, “Our population included a relatively recent birth cohort, which may explain some differences from previous studies as IVF practices have evolved over time.”

An estimated 8 million people worldwide have been conceived through IVF since the first birth in 1978, the researchers said. In Australia, this has grown from 2% of births in the year 2000 to now nearly 5% or 1 in 20 live births, Dr. Kennedy noted. “Consequently, it is important to understand the longer-term outcomes for this population of children.”

Along with senior author Anthea Lindquist, MBBS, Dr. Kennedy and colleagues studied 585,659 single births in Victoria, Australia, between 2005 and 2014. They did not include multiple births such as twins or triplets.

The investigators compared 4,697 children conceived via IVF and 168,503 others conceived spontaneously using a standard developmental measure, the Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC). They also assessed 8,976 children in the IVF group and 333,335 other children on a standard educational measure, the National Assessment Program–Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN).

For example, the developmental census measures developmental vulnerability. Dr. Kennedy and colleagues found a 0.3% difference in favor of IVF-conceived children, which statistically was no different than zero.

Similarly, the researchers reported that IVF conception had essentially no effect on overall the literacy score, with an adjusted average difference of 0.03.

Dr. Lanski said the results should be reassuring for people considering IVF. “I can see the value of the study.” The findings “probably brings a lot of comfort ... if you want to build a family, and medically this is what’s recommended.”

Not all IVF techniques are the same, and the researchers want to take a deeper dive to evaluate any distinctions among them. For example, Dr. Kennedy said, “We plan to investigate the same school-aged outcomes after specific IVF-associated techniques.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

In vitro fertilization has been around long enough that researchers can now compare developmental and academic achievements between these children and peers at school age.

Amber Kennedy, MBBS, and colleagues did just that. They found little difference in these milestones between a total of 11,059 IVF-conceived children and 401,654 spontaneously conceived children in a new study.

“Parents considering IVF and health care professionals can be reassured that the school age developmental and educational outcomes of IVF-conceived children are equivalent to their peers,” said Dr. Kennedy, lead author and obstetrician and gynecologist at Mercy Hospital for Women at the University of Melbourne.

The findings were published online in PLOS Medicine.

“Overall, we know that children born through IVF are doing fine in terms of health, but also emotionally and cognitively. So I wasn’t surprised. I live in this world,” said Ariadna Cymet Lanski, PsyD, chair of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Mental Health Professional Group, who was not affiliated with the study.

Some previous researchers linked conception via IVF to an increased risk of congenital abnormalities, autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and intellectual disability.

Asked why the current study did not find increased risks, Dr. Kennedy said, “Our population included a relatively recent birth cohort, which may explain some differences from previous studies as IVF practices have evolved over time.”

An estimated 8 million people worldwide have been conceived through IVF since the first birth in 1978, the researchers said. In Australia, this has grown from 2% of births in the year 2000 to now nearly 5% or 1 in 20 live births, Dr. Kennedy noted. “Consequently, it is important to understand the longer-term outcomes for this population of children.”

Along with senior author Anthea Lindquist, MBBS, Dr. Kennedy and colleagues studied 585,659 single births in Victoria, Australia, between 2005 and 2014. They did not include multiple births such as twins or triplets.

The investigators compared 4,697 children conceived via IVF and 168,503 others conceived spontaneously using a standard developmental measure, the Australian Early Developmental Census (AEDC). They also assessed 8,976 children in the IVF group and 333,335 other children on a standard educational measure, the National Assessment Program–Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN).

For example, the developmental census measures developmental vulnerability. Dr. Kennedy and colleagues found a 0.3% difference in favor of IVF-conceived children, which statistically was no different than zero.

Similarly, the researchers reported that IVF conception had essentially no effect on overall the literacy score, with an adjusted average difference of 0.03.

Dr. Lanski said the results should be reassuring for people considering IVF. “I can see the value of the study.” The findings “probably brings a lot of comfort ... if you want to build a family, and medically this is what’s recommended.”

Not all IVF techniques are the same, and the researchers want to take a deeper dive to evaluate any distinctions among them. For example, Dr. Kennedy said, “We plan to investigate the same school-aged outcomes after specific IVF-associated techniques.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM PLOS MEDICINE

Study documents link between preadolescent acne and elevated BMI

The that used age- and sex-matched controls.

The investigators also identified “a potential association” with precocious puberty that they said “should be considered, especially among those presenting [with acne] under 8 or 9 years old.” The study was published in Pediatric Dermatology .

Senior author Megha M. Tollefson, MD, and coauthors used resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project to identify all residents of Olmstead County, Minn., who were diagnosed with acne between the ages of 7 and 12 years during 2010-2018. They then randomly selected two age and sex-matched community controls in order to evaluate the relationship of preadolescent acne and BMI.

They confirmed 643 acne cases, and calculated an annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate for ages 7-12 of 58 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 53.5-62.5). The incidence rate was significantly higher in females than males (89.2 vs. 28.2 per 10,000 person-years; P < .001), and it significantly increased with age (incidence rates of 4.3, 24.4, and 144.3 per 10,000 person-years among those ages 7-8, 9-10, and 11-12 years, respectively).

The median BMI percentile among children with acne was significantly higher than those without an acne diagnosis (75.0 vs. 65.0; P <.001). They also were much more likely to be obese: 16.7% of the children with acne had a BMI in at least the 95th percentile, compared with 12.2% among controls with no acne diagnosis (P = .01). (The qualifying 581 acne cases for this analysis had BMIs recorded within 8 months of the index data, in addition to not having pre-existing acne-relevant endocrine disorders.)

“High BMI is a strong risk factor for acne development and severity in adults, but until now pediatric studies have revealed mixed information ... [and have been] largely retrospective reviews without controls,” Dr. Tollefson, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues wrote.

‘Valuable’ data

Leah Lalor, MD, a pediatric dermatologist not involved with the research, said she is happy to see it. “It’s really valuable,” she said in an interview. “It’s actually the first study that gives us incidence data for preadolescent acne. We all have [had our estimates], but this study quantifies it ... and it will set the stage for further studies of preadolescents in the future.”

The study also documents that “girls are more likely to present to the clinic with acne, and to do so at younger ages, which we’ve suspected and which makes physiologic sense since girls tend to go through puberty earlier than boys,” said Dr. Lalor, assistant professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin and the Children’s Wisconsin Clinics, both in Milwaukee. “And most interestingly, it really reveals that BMI is higher among preadolescents with acne than those without.”

The important caveat, she emphasized, is that the study population in Olmstead County, Minn. has a relatively higher level of education, wealth, and employment than the rest of the United States.

The investigators also found that use of systemic acne medications increased with increasing BMI (odds ratio, 1.43 per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI; 95% CI, 1.07-1.92; P = .015). Approximately 5% of underweight or normal children were prescribed systemic acne medications, compared with 8.1% of overweight children, and 10.3% of those who were obese – data that suggest that most preadolescents with acne had mild to moderate disease and that more severe acne may be associated with increasing BMI percentiles, the authors wrote.

Approximately 4% of the 643 preadolescents with acne were diagnosed with an acne-relevant endocrine disorder prior to or at the time of acne diagnosis – most commonly precocious puberty. Of the 24 diagnoses of precocious puberty, 22 were in females, with a mean age at diagnosis of 7.3 years.

Puberty before age 8 in girls and 9 in boys is classified as precocious puberty. “Thus, a thorough review of systems and exam should be done in this population [with acne] to look for precocious puberty with a low threshold for systemic evaluation if indicated,” the authors wrote, also noting that 19 or the 482 female patients with acne were subsequently diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Dr. Lalor said she “automatically” refers children with acne who are younger than 7 for an endocrine workup, but not necessarily children ages 7, 8, or 9 because “that’s considered within the normal realm of starting to get some acne.” Acne in the context of other symptoms such as body odor, hair, or thelarche may prompt referral in these ages, however, she said.

Future research

Obesity may influence preadolescent acne development through its effect on puberty, as overweight and obese girls achieve puberty earlier than those with normal BMI. And “insulin resistance, which may be related to obesity, has been implicated with inducing or worsening acne potentially related to shifts in IGF-1 [insulin-like growth factor 1] signaling and hyperandrogenemia,” Dr. Tollefson and colleagues wrote. Nutrition is also a possible confounder in the study.

“Patients and families have long felt that certain foods or practices contribute to acne, though this has been difficult to prove,” Dr. Lalor said. “We know that excess skim milk seems to contribute ... and there’s a correlation between high glycemic load diets [and acne].”

Assessing dietary habits in conjunction with BMI, and acne incidence and severity, would be valuable. So would research to determine “if decreasing the BMI percentile [in children with acne] would improve or prevent acne, without doing any acne treatments,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Rochester Epidemiology Project. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lalor also reported no conflicts of interest.

The that used age- and sex-matched controls.

The investigators also identified “a potential association” with precocious puberty that they said “should be considered, especially among those presenting [with acne] under 8 or 9 years old.” The study was published in Pediatric Dermatology .

Senior author Megha M. Tollefson, MD, and coauthors used resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project to identify all residents of Olmstead County, Minn., who were diagnosed with acne between the ages of 7 and 12 years during 2010-2018. They then randomly selected two age and sex-matched community controls in order to evaluate the relationship of preadolescent acne and BMI.

They confirmed 643 acne cases, and calculated an annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate for ages 7-12 of 58 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 53.5-62.5). The incidence rate was significantly higher in females than males (89.2 vs. 28.2 per 10,000 person-years; P < .001), and it significantly increased with age (incidence rates of 4.3, 24.4, and 144.3 per 10,000 person-years among those ages 7-8, 9-10, and 11-12 years, respectively).

The median BMI percentile among children with acne was significantly higher than those without an acne diagnosis (75.0 vs. 65.0; P <.001). They also were much more likely to be obese: 16.7% of the children with acne had a BMI in at least the 95th percentile, compared with 12.2% among controls with no acne diagnosis (P = .01). (The qualifying 581 acne cases for this analysis had BMIs recorded within 8 months of the index data, in addition to not having pre-existing acne-relevant endocrine disorders.)

“High BMI is a strong risk factor for acne development and severity in adults, but until now pediatric studies have revealed mixed information ... [and have been] largely retrospective reviews without controls,” Dr. Tollefson, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues wrote.

‘Valuable’ data

Leah Lalor, MD, a pediatric dermatologist not involved with the research, said she is happy to see it. “It’s really valuable,” she said in an interview. “It’s actually the first study that gives us incidence data for preadolescent acne. We all have [had our estimates], but this study quantifies it ... and it will set the stage for further studies of preadolescents in the future.”

The study also documents that “girls are more likely to present to the clinic with acne, and to do so at younger ages, which we’ve suspected and which makes physiologic sense since girls tend to go through puberty earlier than boys,” said Dr. Lalor, assistant professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin and the Children’s Wisconsin Clinics, both in Milwaukee. “And most interestingly, it really reveals that BMI is higher among preadolescents with acne than those without.”

The important caveat, she emphasized, is that the study population in Olmstead County, Minn. has a relatively higher level of education, wealth, and employment than the rest of the United States.

The investigators also found that use of systemic acne medications increased with increasing BMI (odds ratio, 1.43 per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI; 95% CI, 1.07-1.92; P = .015). Approximately 5% of underweight or normal children were prescribed systemic acne medications, compared with 8.1% of overweight children, and 10.3% of those who were obese – data that suggest that most preadolescents with acne had mild to moderate disease and that more severe acne may be associated with increasing BMI percentiles, the authors wrote.

Approximately 4% of the 643 preadolescents with acne were diagnosed with an acne-relevant endocrine disorder prior to or at the time of acne diagnosis – most commonly precocious puberty. Of the 24 diagnoses of precocious puberty, 22 were in females, with a mean age at diagnosis of 7.3 years.

Puberty before age 8 in girls and 9 in boys is classified as precocious puberty. “Thus, a thorough review of systems and exam should be done in this population [with acne] to look for precocious puberty with a low threshold for systemic evaluation if indicated,” the authors wrote, also noting that 19 or the 482 female patients with acne were subsequently diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Dr. Lalor said she “automatically” refers children with acne who are younger than 7 for an endocrine workup, but not necessarily children ages 7, 8, or 9 because “that’s considered within the normal realm of starting to get some acne.” Acne in the context of other symptoms such as body odor, hair, or thelarche may prompt referral in these ages, however, she said.

Future research

Obesity may influence preadolescent acne development through its effect on puberty, as overweight and obese girls achieve puberty earlier than those with normal BMI. And “insulin resistance, which may be related to obesity, has been implicated with inducing or worsening acne potentially related to shifts in IGF-1 [insulin-like growth factor 1] signaling and hyperandrogenemia,” Dr. Tollefson and colleagues wrote. Nutrition is also a possible confounder in the study.

“Patients and families have long felt that certain foods or practices contribute to acne, though this has been difficult to prove,” Dr. Lalor said. “We know that excess skim milk seems to contribute ... and there’s a correlation between high glycemic load diets [and acne].”

Assessing dietary habits in conjunction with BMI, and acne incidence and severity, would be valuable. So would research to determine “if decreasing the BMI percentile [in children with acne] would improve or prevent acne, without doing any acne treatments,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Rochester Epidemiology Project. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lalor also reported no conflicts of interest.

The that used age- and sex-matched controls.

The investigators also identified “a potential association” with precocious puberty that they said “should be considered, especially among those presenting [with acne] under 8 or 9 years old.” The study was published in Pediatric Dermatology .

Senior author Megha M. Tollefson, MD, and coauthors used resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project to identify all residents of Olmstead County, Minn., who were diagnosed with acne between the ages of 7 and 12 years during 2010-2018. They then randomly selected two age and sex-matched community controls in order to evaluate the relationship of preadolescent acne and BMI.

They confirmed 643 acne cases, and calculated an annual age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate for ages 7-12 of 58 per 10,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 53.5-62.5). The incidence rate was significantly higher in females than males (89.2 vs. 28.2 per 10,000 person-years; P < .001), and it significantly increased with age (incidence rates of 4.3, 24.4, and 144.3 per 10,000 person-years among those ages 7-8, 9-10, and 11-12 years, respectively).

The median BMI percentile among children with acne was significantly higher than those without an acne diagnosis (75.0 vs. 65.0; P <.001). They also were much more likely to be obese: 16.7% of the children with acne had a BMI in at least the 95th percentile, compared with 12.2% among controls with no acne diagnosis (P = .01). (The qualifying 581 acne cases for this analysis had BMIs recorded within 8 months of the index data, in addition to not having pre-existing acne-relevant endocrine disorders.)

“High BMI is a strong risk factor for acne development and severity in adults, but until now pediatric studies have revealed mixed information ... [and have been] largely retrospective reviews without controls,” Dr. Tollefson, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., and colleagues wrote.

‘Valuable’ data

Leah Lalor, MD, a pediatric dermatologist not involved with the research, said she is happy to see it. “It’s really valuable,” she said in an interview. “It’s actually the first study that gives us incidence data for preadolescent acne. We all have [had our estimates], but this study quantifies it ... and it will set the stage for further studies of preadolescents in the future.”

The study also documents that “girls are more likely to present to the clinic with acne, and to do so at younger ages, which we’ve suspected and which makes physiologic sense since girls tend to go through puberty earlier than boys,” said Dr. Lalor, assistant professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the Medical College of Wisconsin and the Children’s Wisconsin Clinics, both in Milwaukee. “And most interestingly, it really reveals that BMI is higher among preadolescents with acne than those without.”

The important caveat, she emphasized, is that the study population in Olmstead County, Minn. has a relatively higher level of education, wealth, and employment than the rest of the United States.

The investigators also found that use of systemic acne medications increased with increasing BMI (odds ratio, 1.43 per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI; 95% CI, 1.07-1.92; P = .015). Approximately 5% of underweight or normal children were prescribed systemic acne medications, compared with 8.1% of overweight children, and 10.3% of those who were obese – data that suggest that most preadolescents with acne had mild to moderate disease and that more severe acne may be associated with increasing BMI percentiles, the authors wrote.

Approximately 4% of the 643 preadolescents with acne were diagnosed with an acne-relevant endocrine disorder prior to or at the time of acne diagnosis – most commonly precocious puberty. Of the 24 diagnoses of precocious puberty, 22 were in females, with a mean age at diagnosis of 7.3 years.

Puberty before age 8 in girls and 9 in boys is classified as precocious puberty. “Thus, a thorough review of systems and exam should be done in this population [with acne] to look for precocious puberty with a low threshold for systemic evaluation if indicated,” the authors wrote, also noting that 19 or the 482 female patients with acne were subsequently diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome.

Dr. Lalor said she “automatically” refers children with acne who are younger than 7 for an endocrine workup, but not necessarily children ages 7, 8, or 9 because “that’s considered within the normal realm of starting to get some acne.” Acne in the context of other symptoms such as body odor, hair, or thelarche may prompt referral in these ages, however, she said.

Future research

Obesity may influence preadolescent acne development through its effect on puberty, as overweight and obese girls achieve puberty earlier than those with normal BMI. And “insulin resistance, which may be related to obesity, has been implicated with inducing or worsening acne potentially related to shifts in IGF-1 [insulin-like growth factor 1] signaling and hyperandrogenemia,” Dr. Tollefson and colleagues wrote. Nutrition is also a possible confounder in the study.

“Patients and families have long felt that certain foods or practices contribute to acne, though this has been difficult to prove,” Dr. Lalor said. “We know that excess skim milk seems to contribute ... and there’s a correlation between high glycemic load diets [and acne].”

Assessing dietary habits in conjunction with BMI, and acne incidence and severity, would be valuable. So would research to determine “if decreasing the BMI percentile [in children with acne] would improve or prevent acne, without doing any acne treatments,” she said.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging and the Rochester Epidemiology Project. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Lalor also reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Can pediatricians’ offices be urgent care centers again?

If you live in a suburban or semirural community you have seen at least one urgent care center open up in the last decade. They now number nearly 12,000 nationwide and are growing in number at a 7% rate. Urgent care center patient volume surged during the pandemic and an industry trade group reports it has risen 60% since 2019 (Meyerson N. Why urgent care centers are popping up everywhere. CNN Business. 2023 Jan 28).

According to a report on the CNN Business website, this growth is the result of “convenience, gaps in primary care, high costs of emergency room visits, and increased investment by health systems and equity groups.” Initially, these centers were generally staffed by physicians (70% in 2009) but as of 2022 this number has fallen to 16%. While there are conflicting data to support the claim that urgent care centers are overprescribing, it is pretty clear that their presence in a community encourages fragmented care and weakens established provider-patient relationships. One study has shown that although urgent care centers can prevent a costly emergency room visit ($1,649/visit) this advantage is offset by urgent care cost of more than $6,000.

In the same CNN report, Susan Kressly MD, chair of the AAP’s Private Payer Advocacy Advisory Committee, said: “There’s a need to keep up with society’s demand for quick turnaround, on-demand services that can’t be supported by underfunded primary care.”

Her observation suggests that there is an accelerating demand for timely primary care services. From my perch here in semirural Maine, I don’t see an increasing or unreasonable demand for timeliness by patients and families. Two decades ago, the practice I was in offered evening and weekend morning office hours and call-in times when patientsor parents could speak directly to a physician. These avenues of accessibility have disappeared community wide.

Back in the 1990s “the medical home” was all the buzz. We were encouraged to be the first and primary place to go for a broad range of preventive and responsive care. One-stop shopping at its best. Now it’s “knock, knock ... is anybody home?” Not if it’s getting dark, or it’s the weekend, or you have a minor injury. “Please call the urgent care center.”

I will admit that our dedicated call-in times were unusual and probably not sustainable for most practices. But, most practices back then would see children with acute illness and minor scrapes and trauma on a same-day basis. We dressed burns, splinted joints, and closed minor lacerations. What has changed to create the void that urgent care centers see as an opportunity to make money?

One explanation is the difficulty in finding folks (both providers and support people) who are willing to work a schedule that includes evenings and weekends. One study predicts that there will be a shortfall of 55,000 primary care physicians in the next decade, regardless of their work-life balance preferences. Sometimes it is a lack of creativity and foresight in creating flexible booking schedules that include ample time for patient- and parent-friendly same-day appointments. Minor injuries and skin problems can usually be managed quickly and effectively by an experienced clinician. Unquestionably, one of the big changes has been the shift in the patient mix leaning more toward time-consuming mental health complaints, which make it more difficult to leave open same-day slots. Restoring pediatricians’ offices to their former role as urgent care centers will require training not just more primary care physicians but also mental health consultants and providers.