User login

News and Views that Matter to Pediatricians

The leading independent newspaper covering news and commentary in pediatrics.

Teen girls report record levels of sadness, sexual violence: CDC

Teenage girls are experiencing record high levels of sexual violence, and nearly three in five girls report feeling persistently sad or hopeless, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nearly 70% of teens who identified as lesbian, bisexual, gay, or questioning (LGBQ+) report experiencing feelings of persistent sadness and hopeless, and nearly one in four (22%) LGBQ+ had attempted suicide in 2021, according to the report.

“High school should be a time for trailblazing, not trauma. These data show our kids need far more support to cope, hope, and thrive,” said Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, in a press release about the findings.

The new analysis looked at data from 2011 to 2021 from the CDC’s Youth Risk and Behavior Survey (YRBS), a semiannual analysis of the health behaviors of students in grades 9-12. The 2021 survey is the first YRBS conducted since the COVID-19 pandemic began and included 17,232 respondents.

Although the researchers saw signs of improvement in risky sexual behaviors and substance abuse, as well as fewer experiences of bullying, the analysis found youth mental health worsened over the past 10 years. This trend was particularly troubling for teenage girls: 57% said they felt persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, a 60% increase from a decade ago. By comparison, 29% of teenage boys reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless, compared with 21% in 2011.

Nearly one-third of girls (30%) reported seriously considering suicide, up from 19% in 2011. In teenage boys, serious thoughts of suicide increased from 13% to 14% from 2011 to 2021. The percentage of teenage girls who had attempted suicide in 2021 was 13%, nearly twice that of teenage boys (7%).

More than half of students with a same-sex partner (58%) reported seriously considering suicide, and 45% of LGBQ+ teens reported the same thoughts. One third of students with a same-sex partner reported attempting suicide in the past year.

The report did not have trend data on LGBQ+ students because of changes in survey methods. The 2021 survey did not have a question accessing gender identity, but this will be incorporated into future surveys, according to the researchers.

Hispanic and multiracial students were more likely to experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, compared with their peers, with 46% and 49%, respectively, reporting these feelings. From 2011-2021, the percentage of students reporting feelings of hopelessness increased in each racial and ethnic group. The percentage of Black, Hispanic, and White teens who seriously considered suicide also increased over the decade. (A different report released by the CDC on Feb. 10 found that the rate of suicide among Blacks in the United States aged 10-24 jumped 36.6% between 2018 and 2021, the largest increase for any racial or ethnic group.)

The survey also found an alarming spike in sexual violence toward teenage girls. Nearly one in five females (18%) experienced sexual violence in the past year, a 20% increase from 2017. More than 1 in 10 teen girls (14%) said they had been forced to have sex, according to the researchers.

Rates of sexual violence was even higher in LGBQ+ teens. Nearly two in five teens with a partner of the same sex (39%) experienced sexual violence, and 37% reported being sexually assaulted. More than one in five LGBQ+ teens (22%) had experienced sexual violence, and 20% said they had been forced to have sex, the report found.

Among racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaskan Native and multiracial students were more likely to experience sexual violence. The percentage of White students reporting sexual violence increased from 2017 to 2021, but that trend was not observed in other racial and ethnic groups.

Delaney Ruston, MD, an internal medicine specialist in Seattle and creator of “Screenagers,” a 2016 documentary about how technology affects youth, said excessive exposure to social media can compound feelings of depression in teens – particularly, but not only, girls. “They can scroll and consume media for hours, and rather than do activities and have interactions that would help heal from depression symptoms, they stay stuck,” Ruston said in an interview. “As a primary care physician working with teens, this is an extremely common problem I see in my clinic.”

One approach that can help, Dr. Ruston added, is behavioral activation. “This is a strategy where you get them, usually with the support of other people, to do small activities that help to reset brain reward pathways so they start to experience doses of well-being and hope that eventually reverses the depression. Being stuck on screens prevents these healing actions from happening.”

The report also emphasized the importance of school-based services to support students and combat these troubling trends in worsening mental health. “Schools are the gateway to needed services for many young people,” the report stated. “Schools can provide health, behavioral, and mental health services directly or establish referral systems to connect to community sources of care.”

“Young people are experiencing a level of distress that calls on us to act with urgency and compassion,” Kathleen Ethier, PhD, director of the CDC’s division of adolescent and school health, added in a statement. “With the right programs and services in place, schools have the unique ability to help our youth flourish.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Teenage girls are experiencing record high levels of sexual violence, and nearly three in five girls report feeling persistently sad or hopeless, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nearly 70% of teens who identified as lesbian, bisexual, gay, or questioning (LGBQ+) report experiencing feelings of persistent sadness and hopeless, and nearly one in four (22%) LGBQ+ had attempted suicide in 2021, according to the report.

“High school should be a time for trailblazing, not trauma. These data show our kids need far more support to cope, hope, and thrive,” said Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, in a press release about the findings.

The new analysis looked at data from 2011 to 2021 from the CDC’s Youth Risk and Behavior Survey (YRBS), a semiannual analysis of the health behaviors of students in grades 9-12. The 2021 survey is the first YRBS conducted since the COVID-19 pandemic began and included 17,232 respondents.

Although the researchers saw signs of improvement in risky sexual behaviors and substance abuse, as well as fewer experiences of bullying, the analysis found youth mental health worsened over the past 10 years. This trend was particularly troubling for teenage girls: 57% said they felt persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, a 60% increase from a decade ago. By comparison, 29% of teenage boys reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless, compared with 21% in 2011.

Nearly one-third of girls (30%) reported seriously considering suicide, up from 19% in 2011. In teenage boys, serious thoughts of suicide increased from 13% to 14% from 2011 to 2021. The percentage of teenage girls who had attempted suicide in 2021 was 13%, nearly twice that of teenage boys (7%).

More than half of students with a same-sex partner (58%) reported seriously considering suicide, and 45% of LGBQ+ teens reported the same thoughts. One third of students with a same-sex partner reported attempting suicide in the past year.

The report did not have trend data on LGBQ+ students because of changes in survey methods. The 2021 survey did not have a question accessing gender identity, but this will be incorporated into future surveys, according to the researchers.

Hispanic and multiracial students were more likely to experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, compared with their peers, with 46% and 49%, respectively, reporting these feelings. From 2011-2021, the percentage of students reporting feelings of hopelessness increased in each racial and ethnic group. The percentage of Black, Hispanic, and White teens who seriously considered suicide also increased over the decade. (A different report released by the CDC on Feb. 10 found that the rate of suicide among Blacks in the United States aged 10-24 jumped 36.6% between 2018 and 2021, the largest increase for any racial or ethnic group.)

The survey also found an alarming spike in sexual violence toward teenage girls. Nearly one in five females (18%) experienced sexual violence in the past year, a 20% increase from 2017. More than 1 in 10 teen girls (14%) said they had been forced to have sex, according to the researchers.

Rates of sexual violence was even higher in LGBQ+ teens. Nearly two in five teens with a partner of the same sex (39%) experienced sexual violence, and 37% reported being sexually assaulted. More than one in five LGBQ+ teens (22%) had experienced sexual violence, and 20% said they had been forced to have sex, the report found.

Among racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaskan Native and multiracial students were more likely to experience sexual violence. The percentage of White students reporting sexual violence increased from 2017 to 2021, but that trend was not observed in other racial and ethnic groups.

Delaney Ruston, MD, an internal medicine specialist in Seattle and creator of “Screenagers,” a 2016 documentary about how technology affects youth, said excessive exposure to social media can compound feelings of depression in teens – particularly, but not only, girls. “They can scroll and consume media for hours, and rather than do activities and have interactions that would help heal from depression symptoms, they stay stuck,” Ruston said in an interview. “As a primary care physician working with teens, this is an extremely common problem I see in my clinic.”

One approach that can help, Dr. Ruston added, is behavioral activation. “This is a strategy where you get them, usually with the support of other people, to do small activities that help to reset brain reward pathways so they start to experience doses of well-being and hope that eventually reverses the depression. Being stuck on screens prevents these healing actions from happening.”

The report also emphasized the importance of school-based services to support students and combat these troubling trends in worsening mental health. “Schools are the gateway to needed services for many young people,” the report stated. “Schools can provide health, behavioral, and mental health services directly or establish referral systems to connect to community sources of care.”

“Young people are experiencing a level of distress that calls on us to act with urgency and compassion,” Kathleen Ethier, PhD, director of the CDC’s division of adolescent and school health, added in a statement. “With the right programs and services in place, schools have the unique ability to help our youth flourish.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Teenage girls are experiencing record high levels of sexual violence, and nearly three in five girls report feeling persistently sad or hopeless, according to a new report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nearly 70% of teens who identified as lesbian, bisexual, gay, or questioning (LGBQ+) report experiencing feelings of persistent sadness and hopeless, and nearly one in four (22%) LGBQ+ had attempted suicide in 2021, according to the report.

“High school should be a time for trailblazing, not trauma. These data show our kids need far more support to cope, hope, and thrive,” said Debra Houry, MD, MPH, the CDC’s acting principal deputy director, in a press release about the findings.

The new analysis looked at data from 2011 to 2021 from the CDC’s Youth Risk and Behavior Survey (YRBS), a semiannual analysis of the health behaviors of students in grades 9-12. The 2021 survey is the first YRBS conducted since the COVID-19 pandemic began and included 17,232 respondents.

Although the researchers saw signs of improvement in risky sexual behaviors and substance abuse, as well as fewer experiences of bullying, the analysis found youth mental health worsened over the past 10 years. This trend was particularly troubling for teenage girls: 57% said they felt persistently sad or hopeless in 2021, a 60% increase from a decade ago. By comparison, 29% of teenage boys reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless, compared with 21% in 2011.

Nearly one-third of girls (30%) reported seriously considering suicide, up from 19% in 2011. In teenage boys, serious thoughts of suicide increased from 13% to 14% from 2011 to 2021. The percentage of teenage girls who had attempted suicide in 2021 was 13%, nearly twice that of teenage boys (7%).

More than half of students with a same-sex partner (58%) reported seriously considering suicide, and 45% of LGBQ+ teens reported the same thoughts. One third of students with a same-sex partner reported attempting suicide in the past year.

The report did not have trend data on LGBQ+ students because of changes in survey methods. The 2021 survey did not have a question accessing gender identity, but this will be incorporated into future surveys, according to the researchers.

Hispanic and multiracial students were more likely to experience persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, compared with their peers, with 46% and 49%, respectively, reporting these feelings. From 2011-2021, the percentage of students reporting feelings of hopelessness increased in each racial and ethnic group. The percentage of Black, Hispanic, and White teens who seriously considered suicide also increased over the decade. (A different report released by the CDC on Feb. 10 found that the rate of suicide among Blacks in the United States aged 10-24 jumped 36.6% between 2018 and 2021, the largest increase for any racial or ethnic group.)

The survey also found an alarming spike in sexual violence toward teenage girls. Nearly one in five females (18%) experienced sexual violence in the past year, a 20% increase from 2017. More than 1 in 10 teen girls (14%) said they had been forced to have sex, according to the researchers.

Rates of sexual violence was even higher in LGBQ+ teens. Nearly two in five teens with a partner of the same sex (39%) experienced sexual violence, and 37% reported being sexually assaulted. More than one in five LGBQ+ teens (22%) had experienced sexual violence, and 20% said they had been forced to have sex, the report found.

Among racial and ethnic groups, American Indian and Alaskan Native and multiracial students were more likely to experience sexual violence. The percentage of White students reporting sexual violence increased from 2017 to 2021, but that trend was not observed in other racial and ethnic groups.

Delaney Ruston, MD, an internal medicine specialist in Seattle and creator of “Screenagers,” a 2016 documentary about how technology affects youth, said excessive exposure to social media can compound feelings of depression in teens – particularly, but not only, girls. “They can scroll and consume media for hours, and rather than do activities and have interactions that would help heal from depression symptoms, they stay stuck,” Ruston said in an interview. “As a primary care physician working with teens, this is an extremely common problem I see in my clinic.”

One approach that can help, Dr. Ruston added, is behavioral activation. “This is a strategy where you get them, usually with the support of other people, to do small activities that help to reset brain reward pathways so they start to experience doses of well-being and hope that eventually reverses the depression. Being stuck on screens prevents these healing actions from happening.”

The report also emphasized the importance of school-based services to support students and combat these troubling trends in worsening mental health. “Schools are the gateway to needed services for many young people,” the report stated. “Schools can provide health, behavioral, and mental health services directly or establish referral systems to connect to community sources of care.”

“Young people are experiencing a level of distress that calls on us to act with urgency and compassion,” Kathleen Ethier, PhD, director of the CDC’s division of adolescent and school health, added in a statement. “With the right programs and services in place, schools have the unique ability to help our youth flourish.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Money can buy health but it may not be affordable

It is said that “Money cannot buy happiness.” But ask anyone who does not have it and you will find that money can buy security and freedom from many fears and aggravations. There are no guarantees, but the odds are better with resources than without them. Nations with higher per capita gross domestic product have longer life expectancies, have more freedom, and offer more opportunities for the favored subsets of their populations. The adage is that a rising tide lifts all boats.

It is also said that “Money cannot buy health.” That is also a half lie. Again, there is no guarantee that money can cure what ails you. But over the past 4 decades, modern medical care has added on average 3 years to the average American’s life expectancy. These gains in life expectancy came at a steep cost. The United States has been paying a luxurious, premium price for health care compared with similarly developed nations. When I started my career studying health economics 40 years ago, U.S. health care had increased from 6% of the gross domestic product, was passing 9%, and per my professors, appeared headed for 12% – at which point the predictions were that the sky would start falling. Costs continued to rise and for the past decade about 17% of the U.S. GDP has been going to health care before the pandemic blip.

U.S. life expectancy in the past 150 years nearly doubled. This was primarily due to public health measures rather than the small contributions of medical care for individuals. Life expectancy has mostly risen by reducing infant mortality and childhood mortality. The civil engineers who figured out how to get clean running water into cities and sewage out without the two intermingling have saved far more lives than all the doctors graduating from the medical schools. Better nutrition, better sanitation, vaccines, and, to a smaller extent, antibiotics, have all contributed worthy but lesser effects.

When it comes to individual behavior rather than public health measures, the biggest effect comes from advice physicians have been doling out for decades: Stop smoking, exercise, wear your seatbelt, and do not drink and drive. Over the past generation, medical technology added an incremental improvement to the life span (life expectancy once you attain age 60). This has occurred in cardiovascular health by treating high blood pressure, reducing stroke risk, and lowering hemoglobin A1c. Those measures added about 3 years to life span before the obesity epidemic, the opioid epidemic, and the COVID pandemic wiped out the gains. In round numbers, the price for those 3 extra years of life was about the earnings of working an extra 1-2 years in a lifetime. To share those benefits with everyone, the working stiff has to postpone retirement and work an extra 3 years.

Most recently, modern medicine has produced some very expensive therapies that can add months or years to the lives of people with certain diseases. These therapies may involve over $100,000 worth of marginally beneficial medication that statistically adds a few months to the lives of people with certain varieties of prostate, lung, and breast cancers. Similarly, treatments for chronic disease such as AIDS and cystic fibrosis may involve ongoing medication costs of $10,000 or $20,000 or more per year every year for a lifetime. There are even more extreme examples on the horizon. CAR T-cells and Aduhelm [aducanumab] have the potential to break the Medicare bank. Kaftrio [ivacaftor/tezacaftor/elexacaftor], for cystic fibrosis, is being offered only to wealthier countries.

Medical expenses are hard to analyze because the cited “cost” of many of these medications is like a manufacturer’s suggested retail price that few are actually paying. I am a highly educated consumer, and a physician, but various policies at insurance companies and at national chain pharmacies make it impossible for me to comparison shop for lower prices on my personal medicines. It is not just medications. Over the past 15 years, I have noticed that the “cost” charged for routine lab tests I get have also increased to be 300%-900% higher than what the lab ultimately gets paid by my insurance. It is a farce, and I am chagrined to have been a part of the medical system (managed care organizations, pharmacies, hospitals, and government) that concocted this Frankenstein’s monster of health care payments.

Communicating these issues to a polarized public will require leadership. It will also require better speech writing than the distorted story President Biden used to discuss insulin prices during the State of the Union address. The expensive insulin analogues in common use for diabetes are not the same insulin that was discovered a century ago. The newer medications do provide extra benefits. Assigning a fair value to those benefits is the real issue.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

It is said that “Money cannot buy happiness.” But ask anyone who does not have it and you will find that money can buy security and freedom from many fears and aggravations. There are no guarantees, but the odds are better with resources than without them. Nations with higher per capita gross domestic product have longer life expectancies, have more freedom, and offer more opportunities for the favored subsets of their populations. The adage is that a rising tide lifts all boats.

It is also said that “Money cannot buy health.” That is also a half lie. Again, there is no guarantee that money can cure what ails you. But over the past 4 decades, modern medical care has added on average 3 years to the average American’s life expectancy. These gains in life expectancy came at a steep cost. The United States has been paying a luxurious, premium price for health care compared with similarly developed nations. When I started my career studying health economics 40 years ago, U.S. health care had increased from 6% of the gross domestic product, was passing 9%, and per my professors, appeared headed for 12% – at which point the predictions were that the sky would start falling. Costs continued to rise and for the past decade about 17% of the U.S. GDP has been going to health care before the pandemic blip.

U.S. life expectancy in the past 150 years nearly doubled. This was primarily due to public health measures rather than the small contributions of medical care for individuals. Life expectancy has mostly risen by reducing infant mortality and childhood mortality. The civil engineers who figured out how to get clean running water into cities and sewage out without the two intermingling have saved far more lives than all the doctors graduating from the medical schools. Better nutrition, better sanitation, vaccines, and, to a smaller extent, antibiotics, have all contributed worthy but lesser effects.

When it comes to individual behavior rather than public health measures, the biggest effect comes from advice physicians have been doling out for decades: Stop smoking, exercise, wear your seatbelt, and do not drink and drive. Over the past generation, medical technology added an incremental improvement to the life span (life expectancy once you attain age 60). This has occurred in cardiovascular health by treating high blood pressure, reducing stroke risk, and lowering hemoglobin A1c. Those measures added about 3 years to life span before the obesity epidemic, the opioid epidemic, and the COVID pandemic wiped out the gains. In round numbers, the price for those 3 extra years of life was about the earnings of working an extra 1-2 years in a lifetime. To share those benefits with everyone, the working stiff has to postpone retirement and work an extra 3 years.

Most recently, modern medicine has produced some very expensive therapies that can add months or years to the lives of people with certain diseases. These therapies may involve over $100,000 worth of marginally beneficial medication that statistically adds a few months to the lives of people with certain varieties of prostate, lung, and breast cancers. Similarly, treatments for chronic disease such as AIDS and cystic fibrosis may involve ongoing medication costs of $10,000 or $20,000 or more per year every year for a lifetime. There are even more extreme examples on the horizon. CAR T-cells and Aduhelm [aducanumab] have the potential to break the Medicare bank. Kaftrio [ivacaftor/tezacaftor/elexacaftor], for cystic fibrosis, is being offered only to wealthier countries.

Medical expenses are hard to analyze because the cited “cost” of many of these medications is like a manufacturer’s suggested retail price that few are actually paying. I am a highly educated consumer, and a physician, but various policies at insurance companies and at national chain pharmacies make it impossible for me to comparison shop for lower prices on my personal medicines. It is not just medications. Over the past 15 years, I have noticed that the “cost” charged for routine lab tests I get have also increased to be 300%-900% higher than what the lab ultimately gets paid by my insurance. It is a farce, and I am chagrined to have been a part of the medical system (managed care organizations, pharmacies, hospitals, and government) that concocted this Frankenstein’s monster of health care payments.

Communicating these issues to a polarized public will require leadership. It will also require better speech writing than the distorted story President Biden used to discuss insulin prices during the State of the Union address. The expensive insulin analogues in common use for diabetes are not the same insulin that was discovered a century ago. The newer medications do provide extra benefits. Assigning a fair value to those benefits is the real issue.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

It is said that “Money cannot buy happiness.” But ask anyone who does not have it and you will find that money can buy security and freedom from many fears and aggravations. There are no guarantees, but the odds are better with resources than without them. Nations with higher per capita gross domestic product have longer life expectancies, have more freedom, and offer more opportunities for the favored subsets of their populations. The adage is that a rising tide lifts all boats.

It is also said that “Money cannot buy health.” That is also a half lie. Again, there is no guarantee that money can cure what ails you. But over the past 4 decades, modern medical care has added on average 3 years to the average American’s life expectancy. These gains in life expectancy came at a steep cost. The United States has been paying a luxurious, premium price for health care compared with similarly developed nations. When I started my career studying health economics 40 years ago, U.S. health care had increased from 6% of the gross domestic product, was passing 9%, and per my professors, appeared headed for 12% – at which point the predictions were that the sky would start falling. Costs continued to rise and for the past decade about 17% of the U.S. GDP has been going to health care before the pandemic blip.

U.S. life expectancy in the past 150 years nearly doubled. This was primarily due to public health measures rather than the small contributions of medical care for individuals. Life expectancy has mostly risen by reducing infant mortality and childhood mortality. The civil engineers who figured out how to get clean running water into cities and sewage out without the two intermingling have saved far more lives than all the doctors graduating from the medical schools. Better nutrition, better sanitation, vaccines, and, to a smaller extent, antibiotics, have all contributed worthy but lesser effects.

When it comes to individual behavior rather than public health measures, the biggest effect comes from advice physicians have been doling out for decades: Stop smoking, exercise, wear your seatbelt, and do not drink and drive. Over the past generation, medical technology added an incremental improvement to the life span (life expectancy once you attain age 60). This has occurred in cardiovascular health by treating high blood pressure, reducing stroke risk, and lowering hemoglobin A1c. Those measures added about 3 years to life span before the obesity epidemic, the opioid epidemic, and the COVID pandemic wiped out the gains. In round numbers, the price for those 3 extra years of life was about the earnings of working an extra 1-2 years in a lifetime. To share those benefits with everyone, the working stiff has to postpone retirement and work an extra 3 years.

Most recently, modern medicine has produced some very expensive therapies that can add months or years to the lives of people with certain diseases. These therapies may involve over $100,000 worth of marginally beneficial medication that statistically adds a few months to the lives of people with certain varieties of prostate, lung, and breast cancers. Similarly, treatments for chronic disease such as AIDS and cystic fibrosis may involve ongoing medication costs of $10,000 or $20,000 or more per year every year for a lifetime. There are even more extreme examples on the horizon. CAR T-cells and Aduhelm [aducanumab] have the potential to break the Medicare bank. Kaftrio [ivacaftor/tezacaftor/elexacaftor], for cystic fibrosis, is being offered only to wealthier countries.

Medical expenses are hard to analyze because the cited “cost” of many of these medications is like a manufacturer’s suggested retail price that few are actually paying. I am a highly educated consumer, and a physician, but various policies at insurance companies and at national chain pharmacies make it impossible for me to comparison shop for lower prices on my personal medicines. It is not just medications. Over the past 15 years, I have noticed that the “cost” charged for routine lab tests I get have also increased to be 300%-900% higher than what the lab ultimately gets paid by my insurance. It is a farce, and I am chagrined to have been a part of the medical system (managed care organizations, pharmacies, hospitals, and government) that concocted this Frankenstein’s monster of health care payments.

Communicating these issues to a polarized public will require leadership. It will also require better speech writing than the distorted story President Biden used to discuss insulin prices during the State of the Union address. The expensive insulin analogues in common use for diabetes are not the same insulin that was discovered a century ago. The newer medications do provide extra benefits. Assigning a fair value to those benefits is the real issue.

Dr. Powell is a retired pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

Expelled from high school, Alister Martin became a Harvard doc

It’s not often that a high school brawl with gang members sets you down a path to becoming a Harvard-trained doctor. But that’s exactly how Alister Martin’s life unfolded.

In retrospect, he should have seen the whole thing coming. That night at the party, his best friend was attacked by a gang member from a nearby high school. Martin was not in a gang but he jumped into the fray to defend his friend.

“I wanted to save the day, but that’s not what happened,” he says. “There were just too many of them.”

When his mother rushed to the hospital, he was so bruised and bloody that she couldn’t recognize him at first. Ever since he was a baby, she had done her best to shield him from the neighborhood where gang violence was a regular disruption. But it hadn’t worked.

“My high school had a zero-tolerance policy for gang violence,” Martin says, “so even though I wasn’t in a gang, I was kicked out.”

Now expelled from high school, his mother wanted him out of town, fearing gang retaliation, or that Martin might seek vengeance on the boy who had brutally beaten him. So, the biology teacher and single mom who worked numerous jobs to keep them afloat, came up with a plan to get him far away from any temptations.

Martin had loved tennis since middle school, when his 8th-grade math teacher, Billie Weise, also a tennis pro, got him a job as a court sweeper at an upscale tennis club nearby. He knew nothing then about tennis but would come to fall in love with the sport. To get her son out of town, Martin’s mother took out loans for $30,000 and sent him to a Florida tennis training camp.

After 6 months of training, Martin, who earned a GED degree while attending the camp, was offered a scholarship to play tennis at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. The transition to college was tough, however. He was nervous and felt out of place. “I could have died that first day. It became so obvious how poorly my high school education had prepared me for this.”

But the unease he felt was also motivating in a way. Worried about failure, “he locked himself in a room with another student and they studied day and night,” recalls Kamal Khan, director of the office for diversity and academic success at Rutgers. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

And Martin displayed other attributes that would draw others to him – and later prove important in his career as a doctor. His ability to display empathy and interact with students and teachers separated him from his peers, Mr. Khan says. “There’re a lot of really smart students out there,” he says, “but not many who understand people like Martin.”

After graduating, he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He’d wanted to be a doctor since he was 10 years old after his mom was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. He remembers overhearing a conversation she was having with a family friend about where he would go if she died.

“That’s when I knew it was serious,” he says.

Doctors saved her life, and it’s something he’ll never forget. But it wasn’t until his time at Rutgers that he finally had the confidence to think he could succeed in medical school.

Martin went on to attend Harvard Medical School and Harvard Kennedy School of Government as well as serving as chief resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He was also a fellow at the White House in the Office of the Vice President and today, he’s an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston..

He is most at home in the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he works as an emergency medical specialist. For him, the ER is the first line of defense for meeting the community’s health needs. Growing up in Neptune, the ER “was where poor folks got their care,” he says. His mom worked two jobs and when she got off work at 8 p.m. there was no pediatrician open. “When I was sick as a kid we always went to the emergency room,” he says.

While at Harvard, he also pursued a degree from the Kennedy School of Government, because of the huge role he feels that politics play in our health care system and especially in bringing care to impoverished communities. And since then he’s taken numerous steps to bridge the gap.

Addiction, for example, became an important issue for Martin, ever since a patient he encountered in his first week as an internist. She was a mom of two who had recently gotten surgery because she broke her ankle falling down the stairs at her child’s daycare, he says. Prescribed oxycodone, she feared she was becoming addicted and needed help. But at the time, there was nothing the ER could do.

“I remember that look in her eyes when we had to turn her away,” he says.

Martin has worked to change protocol at his hospital and others throughout the nation so they can be better set up to treat opioid addiction. He’s the founder of GetWaivered, an organization that trains doctors throughout the country to use evidence-based medicine to manage opioid addiction. In the U.S. doctors need what’s called a DEA X waiver to be able to prescribe buprenorphine to opioid-addicted patients. That means that currently only about 1% of all emergency room doctors nationwide have the waiver and without it, it’s impossible to help patients when they need it the most.

Shuhan He, MD, an internist with Martin at Massachusetts General Hospital who also works on the GetWaivered program, says Martin has a particular trait that helps him be successful.

“He’s a doer and when he sees a problem, he’s gonna try and fix it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not often that a high school brawl with gang members sets you down a path to becoming a Harvard-trained doctor. But that’s exactly how Alister Martin’s life unfolded.

In retrospect, he should have seen the whole thing coming. That night at the party, his best friend was attacked by a gang member from a nearby high school. Martin was not in a gang but he jumped into the fray to defend his friend.

“I wanted to save the day, but that’s not what happened,” he says. “There were just too many of them.”

When his mother rushed to the hospital, he was so bruised and bloody that she couldn’t recognize him at first. Ever since he was a baby, she had done her best to shield him from the neighborhood where gang violence was a regular disruption. But it hadn’t worked.

“My high school had a zero-tolerance policy for gang violence,” Martin says, “so even though I wasn’t in a gang, I was kicked out.”

Now expelled from high school, his mother wanted him out of town, fearing gang retaliation, or that Martin might seek vengeance on the boy who had brutally beaten him. So, the biology teacher and single mom who worked numerous jobs to keep them afloat, came up with a plan to get him far away from any temptations.

Martin had loved tennis since middle school, when his 8th-grade math teacher, Billie Weise, also a tennis pro, got him a job as a court sweeper at an upscale tennis club nearby. He knew nothing then about tennis but would come to fall in love with the sport. To get her son out of town, Martin’s mother took out loans for $30,000 and sent him to a Florida tennis training camp.

After 6 months of training, Martin, who earned a GED degree while attending the camp, was offered a scholarship to play tennis at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. The transition to college was tough, however. He was nervous and felt out of place. “I could have died that first day. It became so obvious how poorly my high school education had prepared me for this.”

But the unease he felt was also motivating in a way. Worried about failure, “he locked himself in a room with another student and they studied day and night,” recalls Kamal Khan, director of the office for diversity and academic success at Rutgers. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

And Martin displayed other attributes that would draw others to him – and later prove important in his career as a doctor. His ability to display empathy and interact with students and teachers separated him from his peers, Mr. Khan says. “There’re a lot of really smart students out there,” he says, “but not many who understand people like Martin.”

After graduating, he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He’d wanted to be a doctor since he was 10 years old after his mom was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. He remembers overhearing a conversation she was having with a family friend about where he would go if she died.

“That’s when I knew it was serious,” he says.

Doctors saved her life, and it’s something he’ll never forget. But it wasn’t until his time at Rutgers that he finally had the confidence to think he could succeed in medical school.

Martin went on to attend Harvard Medical School and Harvard Kennedy School of Government as well as serving as chief resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He was also a fellow at the White House in the Office of the Vice President and today, he’s an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston..

He is most at home in the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he works as an emergency medical specialist. For him, the ER is the first line of defense for meeting the community’s health needs. Growing up in Neptune, the ER “was where poor folks got their care,” he says. His mom worked two jobs and when she got off work at 8 p.m. there was no pediatrician open. “When I was sick as a kid we always went to the emergency room,” he says.

While at Harvard, he also pursued a degree from the Kennedy School of Government, because of the huge role he feels that politics play in our health care system and especially in bringing care to impoverished communities. And since then he’s taken numerous steps to bridge the gap.

Addiction, for example, became an important issue for Martin, ever since a patient he encountered in his first week as an internist. She was a mom of two who had recently gotten surgery because she broke her ankle falling down the stairs at her child’s daycare, he says. Prescribed oxycodone, she feared she was becoming addicted and needed help. But at the time, there was nothing the ER could do.

“I remember that look in her eyes when we had to turn her away,” he says.

Martin has worked to change protocol at his hospital and others throughout the nation so they can be better set up to treat opioid addiction. He’s the founder of GetWaivered, an organization that trains doctors throughout the country to use evidence-based medicine to manage opioid addiction. In the U.S. doctors need what’s called a DEA X waiver to be able to prescribe buprenorphine to opioid-addicted patients. That means that currently only about 1% of all emergency room doctors nationwide have the waiver and without it, it’s impossible to help patients when they need it the most.

Shuhan He, MD, an internist with Martin at Massachusetts General Hospital who also works on the GetWaivered program, says Martin has a particular trait that helps him be successful.

“He’s a doer and when he sees a problem, he’s gonna try and fix it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s not often that a high school brawl with gang members sets you down a path to becoming a Harvard-trained doctor. But that’s exactly how Alister Martin’s life unfolded.

In retrospect, he should have seen the whole thing coming. That night at the party, his best friend was attacked by a gang member from a nearby high school. Martin was not in a gang but he jumped into the fray to defend his friend.

“I wanted to save the day, but that’s not what happened,” he says. “There were just too many of them.”

When his mother rushed to the hospital, he was so bruised and bloody that she couldn’t recognize him at first. Ever since he was a baby, she had done her best to shield him from the neighborhood where gang violence was a regular disruption. But it hadn’t worked.

“My high school had a zero-tolerance policy for gang violence,” Martin says, “so even though I wasn’t in a gang, I was kicked out.”

Now expelled from high school, his mother wanted him out of town, fearing gang retaliation, or that Martin might seek vengeance on the boy who had brutally beaten him. So, the biology teacher and single mom who worked numerous jobs to keep them afloat, came up with a plan to get him far away from any temptations.

Martin had loved tennis since middle school, when his 8th-grade math teacher, Billie Weise, also a tennis pro, got him a job as a court sweeper at an upscale tennis club nearby. He knew nothing then about tennis but would come to fall in love with the sport. To get her son out of town, Martin’s mother took out loans for $30,000 and sent him to a Florida tennis training camp.

After 6 months of training, Martin, who earned a GED degree while attending the camp, was offered a scholarship to play tennis at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J. The transition to college was tough, however. He was nervous and felt out of place. “I could have died that first day. It became so obvious how poorly my high school education had prepared me for this.”

But the unease he felt was also motivating in a way. Worried about failure, “he locked himself in a room with another student and they studied day and night,” recalls Kamal Khan, director of the office for diversity and academic success at Rutgers. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

And Martin displayed other attributes that would draw others to him – and later prove important in his career as a doctor. His ability to display empathy and interact with students and teachers separated him from his peers, Mr. Khan says. “There’re a lot of really smart students out there,” he says, “but not many who understand people like Martin.”

After graduating, he decided to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor. He’d wanted to be a doctor since he was 10 years old after his mom was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. He remembers overhearing a conversation she was having with a family friend about where he would go if she died.

“That’s when I knew it was serious,” he says.

Doctors saved her life, and it’s something he’ll never forget. But it wasn’t until his time at Rutgers that he finally had the confidence to think he could succeed in medical school.

Martin went on to attend Harvard Medical School and Harvard Kennedy School of Government as well as serving as chief resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. He was also a fellow at the White House in the Office of the Vice President and today, he’s an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston..

He is most at home in the emergency room at Massachusetts General Hospital, where he works as an emergency medical specialist. For him, the ER is the first line of defense for meeting the community’s health needs. Growing up in Neptune, the ER “was where poor folks got their care,” he says. His mom worked two jobs and when she got off work at 8 p.m. there was no pediatrician open. “When I was sick as a kid we always went to the emergency room,” he says.

While at Harvard, he also pursued a degree from the Kennedy School of Government, because of the huge role he feels that politics play in our health care system and especially in bringing care to impoverished communities. And since then he’s taken numerous steps to bridge the gap.

Addiction, for example, became an important issue for Martin, ever since a patient he encountered in his first week as an internist. She was a mom of two who had recently gotten surgery because she broke her ankle falling down the stairs at her child’s daycare, he says. Prescribed oxycodone, she feared she was becoming addicted and needed help. But at the time, there was nothing the ER could do.

“I remember that look in her eyes when we had to turn her away,” he says.

Martin has worked to change protocol at his hospital and others throughout the nation so they can be better set up to treat opioid addiction. He’s the founder of GetWaivered, an organization that trains doctors throughout the country to use evidence-based medicine to manage opioid addiction. In the U.S. doctors need what’s called a DEA X waiver to be able to prescribe buprenorphine to opioid-addicted patients. That means that currently only about 1% of all emergency room doctors nationwide have the waiver and without it, it’s impossible to help patients when they need it the most.

Shuhan He, MD, an internist with Martin at Massachusetts General Hospital who also works on the GetWaivered program, says Martin has a particular trait that helps him be successful.

“He’s a doer and when he sees a problem, he’s gonna try and fix it.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Joint effort: CBD not just innocent bystander in weed

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

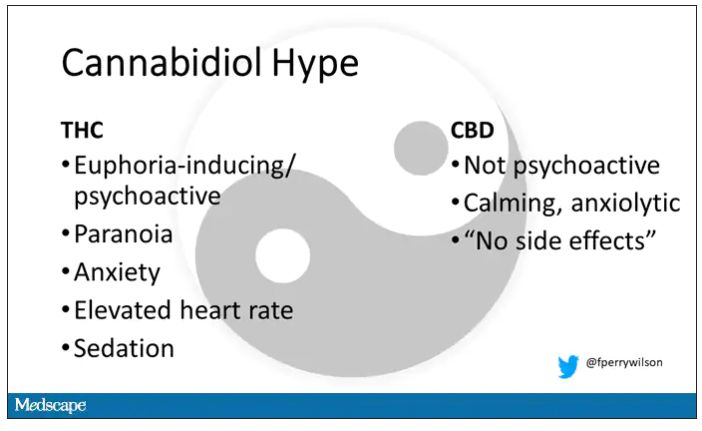

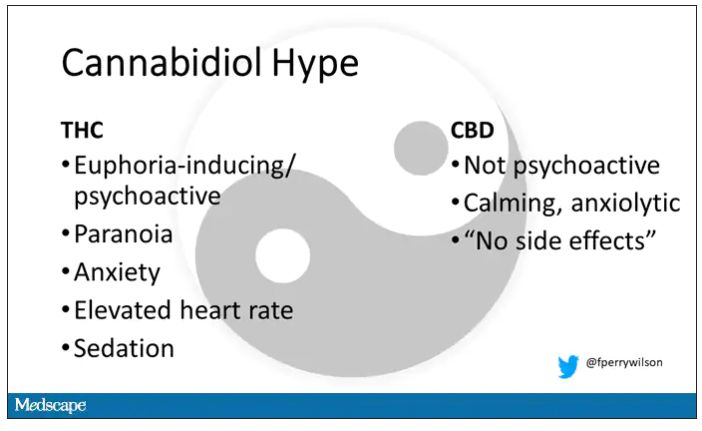

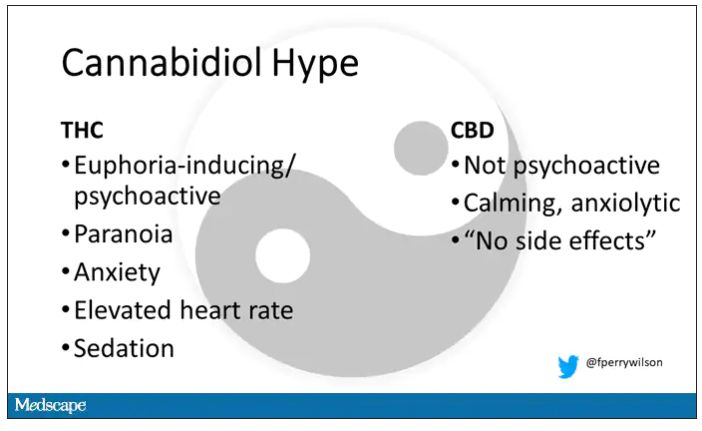

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

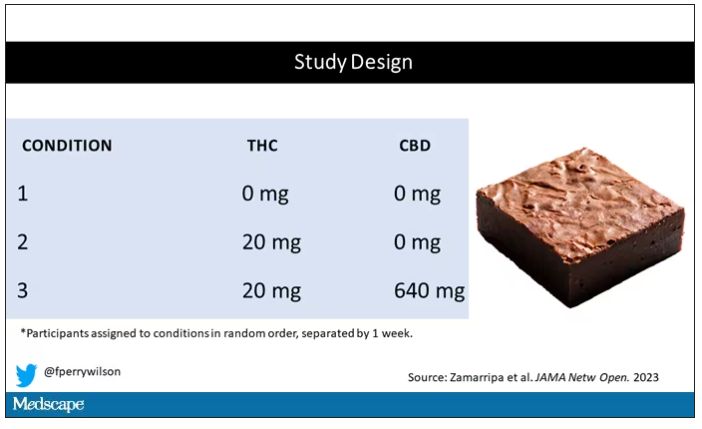

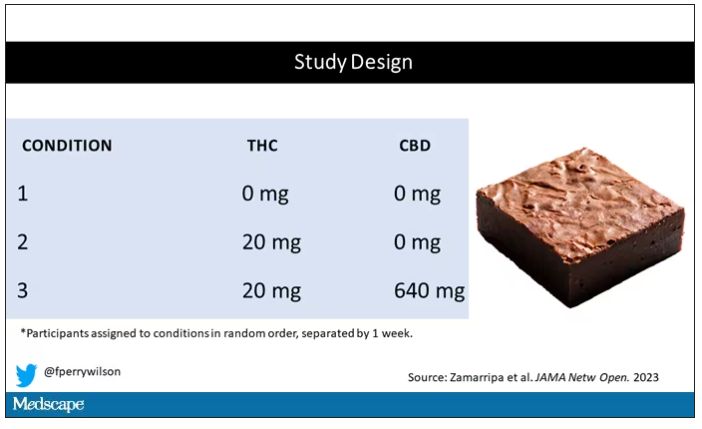

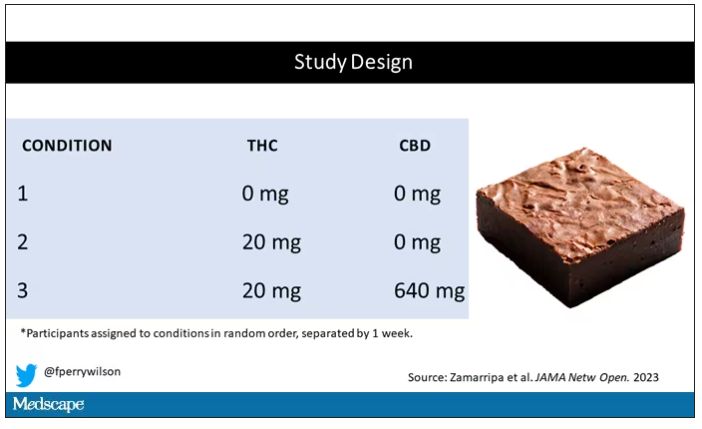

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

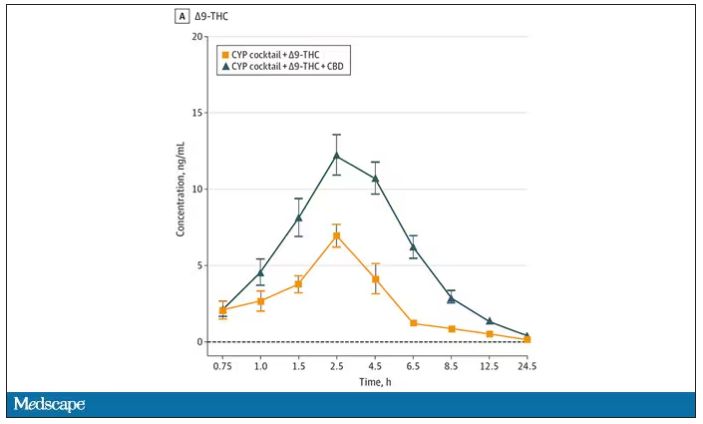

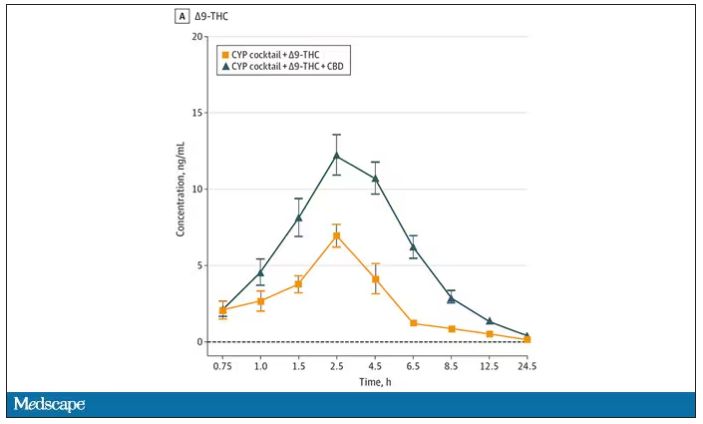

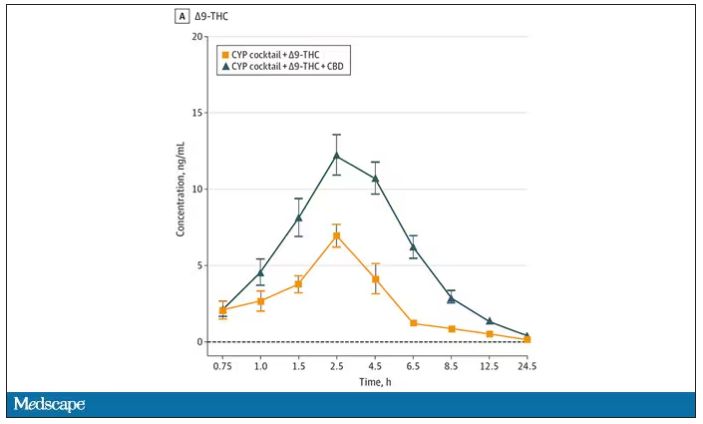

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

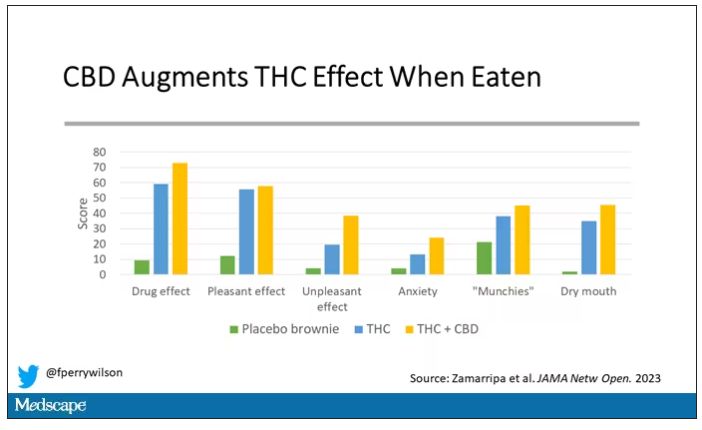

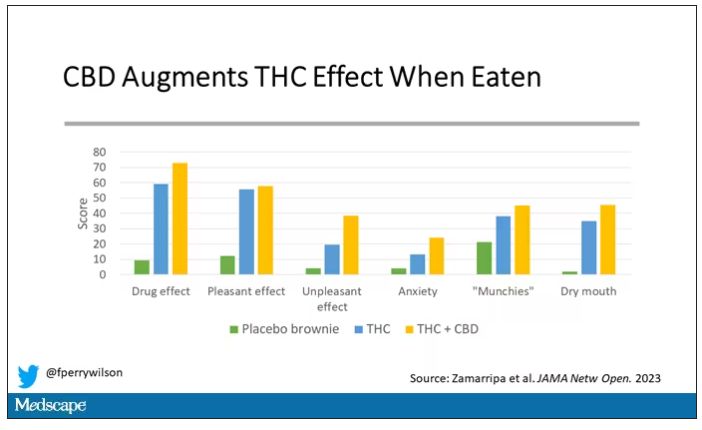

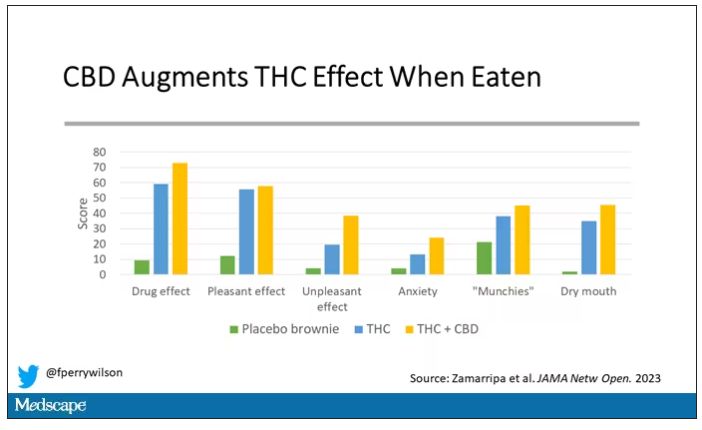

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

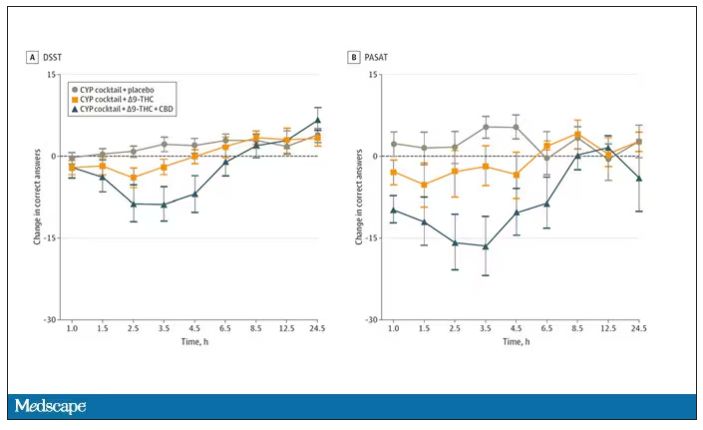

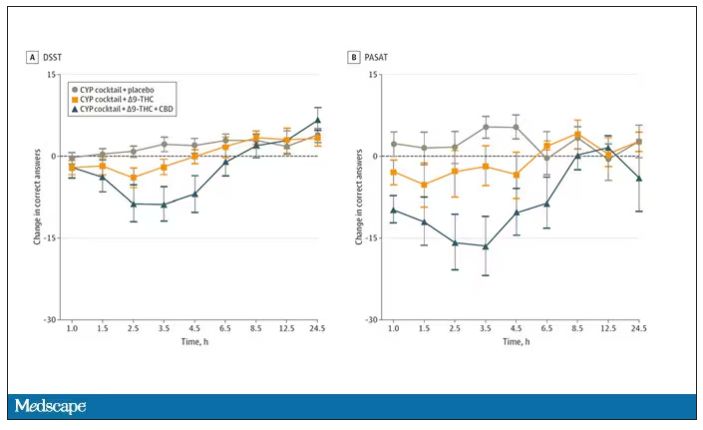

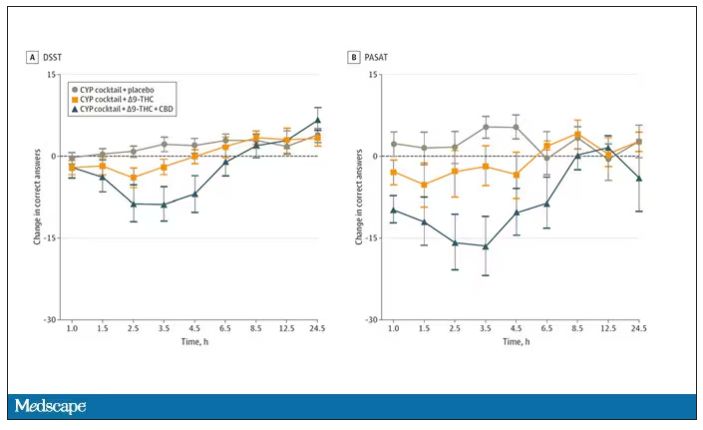

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

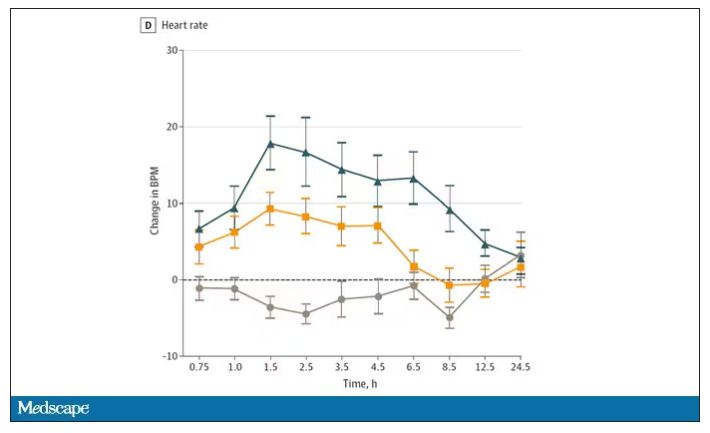

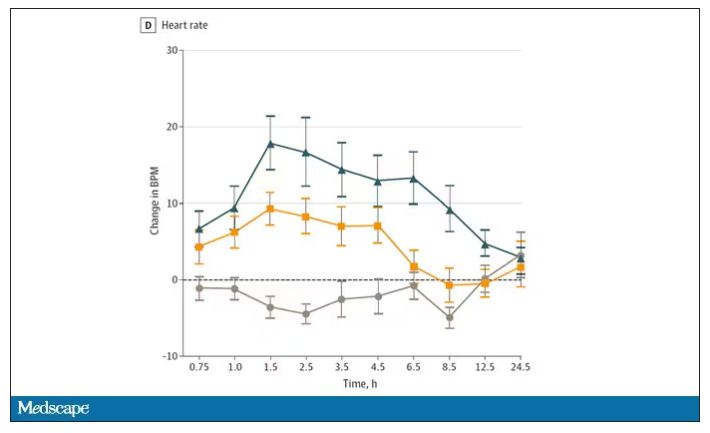

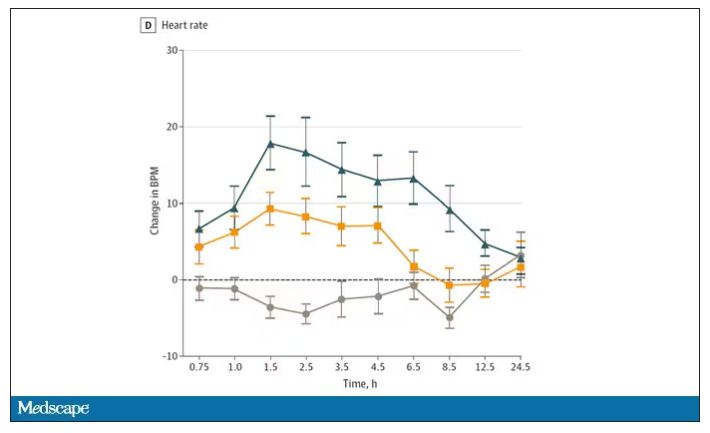

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

I visited a legal cannabis dispensary in Massachusetts a few years ago, mostly to see what the hype was about. There I was, knowing basically nothing about pot, as the gentle stoner behind the counter explained to me the differences between the various strains. Acapulco Gold is buoyant and energizing; Purple Kush is sleepy, relaxed, dissociative. Here’s a strain that makes you feel nostalgic; here’s one that helps you focus. It was as complicated and as oddly specific as a fancy wine tasting – and, I had a feeling, about as reliable.

It’s a plant, after all, and though delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is the chemical responsible for its euphoric effects, it is far from the only substance in there.

The second most important compound in cannabis is cannabidiol, and most people will tell you that CBD is the gentle yin to THC’s paranoiac yang. Hence your local ganja barista reminding you that, if you don›t want all those anxiety-inducing side effects of THC, grab a strain with a nice CBD balance.

But is it true? A new study appearing in JAMA Network Open suggests, in fact, that it’s quite the opposite. This study is from Austin Zamarripa and colleagues, who clearly sit at the researcher cool kids table.

Eighteen adults who had abstained from marijuana use for at least a month participated in this trial (which is way more fun than anything we do in my lab at Yale). In random order, separated by at least a week, they ate some special brownies.

Condition one was a control brownie, condition two was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC, and condition three was a brownie containing 20 mg of THC and 640 mg of CBD. Participants were assigned each condition in random order, separated by at least a week.

A side note on doses for those of you who, like me, are not totally weed literate. A dose of 20 mg of THC is about a third of what you might find in a typical joint these days (though it’s about double the THC content of a joint in the ‘70s – I believe the technical term is “doobie”). And 640 mg of CBD is a decent dose, as 5 mg per kilogram is what some folks start with to achieve therapeutic effects.

Both THC and CBD interact with the cytochrome p450 system in the liver. This matters when you’re ingesting them instead of smoking them because you have first-pass metabolism to contend with. And, because of that p450 inhibition, it’s possible that CBD might actually increase the amount of THC that gets into your bloodstream from the brownie, or gummy, or pizza sauce, or whatever.

Let’s get to the results, starting with blood THC concentration. It’s not subtle. With CBD on board the THC concentration rises higher faster, with roughly double the area under the curve.

And, unsurprisingly, the subjective experience correlated with those higher levels. Individuals rated the “drug effect” higher with the combo. But, interestingly, the “pleasant” drug effect didn’t change much, while the unpleasant effects were substantially higher. No mitigation of THC anxiety here – quite the opposite. CBD made the anxiety worse.

Cognitive effects were equally profound. Scores on a digit symbol substitution test and a paced serial addition task were all substantially worse when CBD was mixed with THC.

And for those of you who want some more objective measures, check out the heart rate. Despite the purported “calming” nature of CBD, heart rates were way higher when individuals were exposed to both chemicals.

The picture here is quite clear, though the mechanism is not. At least when talking edibles, CBD enhances the effects of THC, and not necessarily for the better. It may be that CBD is competing with some of the proteins that metabolize THC, thus prolonging its effects. CBD may also directly inhibit those enzymes. But whatever the case, I think we can safely say the myth that CBD makes the effects of THC more mild or more tolerable is busted.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale University’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator in New Haven, Conn.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New challenge for docs: End of COVID federal public health emergency

The Biden administration intends to end by May 11 certain COVID-19 emergency measures used to aid in the response to the pandemic, while many others will remain in place.

A separate declaration covers the Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for COVID medicines and tests. That would not be affected by the May 11 deadline, the FDA said. In addition, Congress and state lawmakers have extended some COVID response measures.

The result is a patchwork of emergency COVID-19 measures with different end dates.

The American Medical Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) are assessing how best to advise their members about the end of the public health emergency.

Several waivers regarding copays and coverage and policies regarding controlled substances will expire, Claire Ernst, director of government affairs at the Medical Group Management Association, told this news organization.

The impact of the unwinding “will vary based on some factors, such as what state the practice resides in,” Ms. Ernst said. “Fortunately, Congress provided some predictability for practices by extending many of the telehealth waivers through the end of 2024.”

The AAFP told this news organization that it has joined several other groups in calling for the release of proposed Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) regulations meant to permanently allow prescriptions of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder via telehealth. The AAFP and other groups want to review these proposals and, if needed, urge the DEA to modify or finalize before there are any disruptions in access to medications for opioid use disorder.

Patients’ questions

Clinicians can expect to field patients’ questions about their insurance coverage and what they need to pay, said Nancy Foster, vice president for quality and patient safety policy at the American Hospital Association (AHA).

“Your doctor’s office, that clinic you typically get care at, that is the face of medicine to you,” Ms. Foster told this news organization. “Many doctors and their staff will be asked, ‘What’s happening with Medicaid?’ ‘What about my Medicare coverage?’ ‘Can I still access care in the same way that I did before?’ ”

Physicians will need to be ready to answers those question, or point patients to where they can get answers, Ms. Foster said.

For example, Medicaid will no longer cover postpartum care for some enrollees after giving birth, said Taylor Platt, health policy manager for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The federal response to the pandemic created “a de facto postpartum coverage extension for Medicaid enrollees,” which will be lost in some states, Ms. Platt told this news organization. However, 28 states and the District of Columbia have taken separate measures to extend postpartum coverage to 1 year.

“This coverage has been critical for postpartum individuals to address health needs like substance use and mental health treatment and chronic conditions,” Ms. Platt said.

States significantly changed Medicaid policy to expand access to care during the pandemic.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia, for example, expanded coverage or access to telehealth services in Medicaid during the pandemic, according to a Jan. 31 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). These expansions expire under various deadlines, although most states have made or are planning to make some Medicaid telehealth flexibilities permanent, KFF said.

The KFF report notes that all states and the District of Columbia temporarily waived some aspects of state licensure requirements, so that clinicians with equivalent licenses in other states could practice via telehealth.

In some states, these waivers are still active and are tied to the end of the federal emergency declaration. In others, they expired, with some states allowing for long-term or permanent interstate telemedicine, KFF said. (The Federation of State Medical Boards has a detailed summary of these modifications.)

The end of free COVID vaccines, testing for some patients

The AAFP has also raised concerns about continued access to COVID-19 vaccines, particularly for uninsured adults. Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a tweet that this transition, however, wouldn’t happen until a few months after the public health emergency ends.

After those few months, there will be a transition from U.S. government–distributed vaccines and treatments to ones purchased through the regular health care system, the “way we do for every other vaccine and treatment,” Dr. Jha added.

But that raises the same kind of difficult questions that permeate U.S. health care, with a potential to keep COVID active, said Patricia Jackson, RN, president of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

People who don’t have insurance may lose access to COVID testing and vaccines.

“Will that lead to increases in transmission? Who knows,” Ms. Jackson told this news organization. “We will have to see. There are some health equity issues that potentially arise.”

Future FDA actions

Biden’s May 11 deadline applies to emergency provisions made under a Section 319 declaration, which allow the Department of Health and Human Services to respond to crises.

But a separate flexibility, known as a Section 564 declaration, covers the FDA’s EUAs, which can remain in effect even as the other declarations end.

The best-known EUAs for the pandemic were used to bring COVID vaccines and treatments to market. Many of these have since been converted to normal approvals as companies presented more evidence to support the initial emergency approvals. In other cases, EUAs have been withdrawn owing to disappointing research results, changing virus strains, and evolving medical treatments.

The FDA also used many EUAs to cover new uses of ventilators and other hospital equipment and expand these supplies in response to the pandemic, said Mark Howell, AHA’s director of policy and patient safety.

The FDA should examine the EUAs issued during the pandemic to see what greater flexibilities might be used to deal with future serious shortages of critical supplies. International incidents such as the war in Ukraine show how fragile the supply chain can be. The FDA should consider its recent experience with EUAs to address this, Mr. Howell said.

“What do we do coming out of the pandemic? And how do we think about being more proactive in this space to ensure that our supply doesn’t bottleneck, that we continue to make sure that providers have access to supply that’s not only safe and effective, but that they can use?” Mr. Howell told this news organization.

Such planning might also help prepare the country for the next pandemic, which is a near certainty, APIC’s Ms. Jackson said. The nation needs a nimbler response to the next major outbreak of an infectious disease, she said.

“There is going to be a next time,” Ms. Jackson said. “We are going to have another pandemic.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Biden administration intends to end by May 11 certain COVID-19 emergency measures used to aid in the response to the pandemic, while many others will remain in place.

A separate declaration covers the Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for COVID medicines and tests. That would not be affected by the May 11 deadline, the FDA said. In addition, Congress and state lawmakers have extended some COVID response measures.

The result is a patchwork of emergency COVID-19 measures with different end dates.

The American Medical Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) are assessing how best to advise their members about the end of the public health emergency.

Several waivers regarding copays and coverage and policies regarding controlled substances will expire, Claire Ernst, director of government affairs at the Medical Group Management Association, told this news organization.

The impact of the unwinding “will vary based on some factors, such as what state the practice resides in,” Ms. Ernst said. “Fortunately, Congress provided some predictability for practices by extending many of the telehealth waivers through the end of 2024.”

The AAFP told this news organization that it has joined several other groups in calling for the release of proposed Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) regulations meant to permanently allow prescriptions of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder via telehealth. The AAFP and other groups want to review these proposals and, if needed, urge the DEA to modify or finalize before there are any disruptions in access to medications for opioid use disorder.

Patients’ questions

Clinicians can expect to field patients’ questions about their insurance coverage and what they need to pay, said Nancy Foster, vice president for quality and patient safety policy at the American Hospital Association (AHA).

“Your doctor’s office, that clinic you typically get care at, that is the face of medicine to you,” Ms. Foster told this news organization. “Many doctors and their staff will be asked, ‘What’s happening with Medicaid?’ ‘What about my Medicare coverage?’ ‘Can I still access care in the same way that I did before?’ ”

Physicians will need to be ready to answers those question, or point patients to where they can get answers, Ms. Foster said.

For example, Medicaid will no longer cover postpartum care for some enrollees after giving birth, said Taylor Platt, health policy manager for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The federal response to the pandemic created “a de facto postpartum coverage extension for Medicaid enrollees,” which will be lost in some states, Ms. Platt told this news organization. However, 28 states and the District of Columbia have taken separate measures to extend postpartum coverage to 1 year.

“This coverage has been critical for postpartum individuals to address health needs like substance use and mental health treatment and chronic conditions,” Ms. Platt said.

States significantly changed Medicaid policy to expand access to care during the pandemic.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia, for example, expanded coverage or access to telehealth services in Medicaid during the pandemic, according to a Jan. 31 report from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). These expansions expire under various deadlines, although most states have made or are planning to make some Medicaid telehealth flexibilities permanent, KFF said.

The KFF report notes that all states and the District of Columbia temporarily waived some aspects of state licensure requirements, so that clinicians with equivalent licenses in other states could practice via telehealth.

In some states, these waivers are still active and are tied to the end of the federal emergency declaration. In others, they expired, with some states allowing for long-term or permanent interstate telemedicine, KFF said. (The Federation of State Medical Boards has a detailed summary of these modifications.)

The end of free COVID vaccines, testing for some patients

The AAFP has also raised concerns about continued access to COVID-19 vaccines, particularly for uninsured adults. Ashish Jha, MD, MPH, the White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator, said in a tweet that this transition, however, wouldn’t happen until a few months after the public health emergency ends.

After those few months, there will be a transition from U.S. government–distributed vaccines and treatments to ones purchased through the regular health care system, the “way we do for every other vaccine and treatment,” Dr. Jha added.

But that raises the same kind of difficult questions that permeate U.S. health care, with a potential to keep COVID active, said Patricia Jackson, RN, president of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology (APIC).

People who don’t have insurance may lose access to COVID testing and vaccines.

“Will that lead to increases in transmission? Who knows,” Ms. Jackson told this news organization. “We will have to see. There are some health equity issues that potentially arise.”

Future FDA actions

Biden’s May 11 deadline applies to emergency provisions made under a Section 319 declaration, which allow the Department of Health and Human Services to respond to crises.

But a separate flexibility, known as a Section 564 declaration, covers the FDA’s EUAs, which can remain in effect even as the other declarations end.

The best-known EUAs for the pandemic were used to bring COVID vaccines and treatments to market. Many of these have since been converted to normal approvals as companies presented more evidence to support the initial emergency approvals. In other cases, EUAs have been withdrawn owing to disappointing research results, changing virus strains, and evolving medical treatments.

The FDA also used many EUAs to cover new uses of ventilators and other hospital equipment and expand these supplies in response to the pandemic, said Mark Howell, AHA’s director of policy and patient safety.

The FDA should examine the EUAs issued during the pandemic to see what greater flexibilities might be used to deal with future serious shortages of critical supplies. International incidents such as the war in Ukraine show how fragile the supply chain can be. The FDA should consider its recent experience with EUAs to address this, Mr. Howell said.

“What do we do coming out of the pandemic? And how do we think about being more proactive in this space to ensure that our supply doesn’t bottleneck, that we continue to make sure that providers have access to supply that’s not only safe and effective, but that they can use?” Mr. Howell told this news organization.

Such planning might also help prepare the country for the next pandemic, which is a near certainty, APIC’s Ms. Jackson said. The nation needs a nimbler response to the next major outbreak of an infectious disease, she said.

“There is going to be a next time,” Ms. Jackson said. “We are going to have another pandemic.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Biden administration intends to end by May 11 certain COVID-19 emergency measures used to aid in the response to the pandemic, while many others will remain in place.

A separate declaration covers the Food and Drug Administration’s emergency use authorizations (EUAs) for COVID medicines and tests. That would not be affected by the May 11 deadline, the FDA said. In addition, Congress and state lawmakers have extended some COVID response measures.

The result is a patchwork of emergency COVID-19 measures with different end dates.

The American Medical Association and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) are assessing how best to advise their members about the end of the public health emergency.

Several waivers regarding copays and coverage and policies regarding controlled substances will expire, Claire Ernst, director of government affairs at the Medical Group Management Association, told this news organization.

The impact of the unwinding “will vary based on some factors, such as what state the practice resides in,” Ms. Ernst said. “Fortunately, Congress provided some predictability for practices by extending many of the telehealth waivers through the end of 2024.”

The AAFP told this news organization that it has joined several other groups in calling for the release of proposed Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) regulations meant to permanently allow prescriptions of buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder via telehealth. The AAFP and other groups want to review these proposals and, if needed, urge the DEA to modify or finalize before there are any disruptions in access to medications for opioid use disorder.

Patients’ questions

Clinicians can expect to field patients’ questions about their insurance coverage and what they need to pay, said Nancy Foster, vice president for quality and patient safety policy at the American Hospital Association (AHA).

“Your doctor’s office, that clinic you typically get care at, that is the face of medicine to you,” Ms. Foster told this news organization. “Many doctors and their staff will be asked, ‘What’s happening with Medicaid?’ ‘What about my Medicare coverage?’ ‘Can I still access care in the same way that I did before?’ ”

Physicians will need to be ready to answers those question, or point patients to where they can get answers, Ms. Foster said.

For example, Medicaid will no longer cover postpartum care for some enrollees after giving birth, said Taylor Platt, health policy manager for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.