User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Black women weigh emerging risks of ‘creamy crack’ hair straighteners

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

Deanna Denham Hughes was stunned when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2022. She was only 32. She had no family history of cancer, and tests found no genetic link. Ms. Hughes wondered why she, an otherwise healthy Black mother of two, would develop a malignancy known as a “silent killer.”

After emergency surgery to remove the mass, along with her ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and appendix, Ms. Hughes said, she saw an Instagram post in which a woman with uterine cancer linked her condition to chemical hair straighteners.

“I almost fell over,” she said from her home in Smyrna, Ga.

When Ms. Hughes was about 4, her mother began applying a chemical straightener, or relaxer, to her hair every 6-8 weeks. “It burned, and it smelled awful,” Ms. Hughes recalled. “But it was just part of our routine to ‘deal with my hair.’ ”

The routine continued until she went to college and met other Black women who wore their hair naturally. Soon, Ms. Hughes quit relaxers.

Social and economic pressures have long compelled Black girls and women to straighten their hair to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards. But chemical straighteners are stinky and costly and sometimes cause painful scalp burns. Mounting evidence now shows they could be a health hazard.

Relaxers can contain carcinogens, such as formaldehyde-releasing agents, phthalates, and other endocrine-disrupting compounds, according to National Institutes of Health studies. The compounds can mimic the body’s hormones and have been linked to breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers, studies show.

African American women’s often frequent and lifelong application of chemical relaxers to their hair and scalp might explain why hormone-related cancers kill disproportionately more Black than White women, say researchers and cancer doctors.

“What’s in these products is harmful,” said Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, who has studied straightening products for the past 20 years.

She believes manufacturers, policymakers, and physicians should warn consumers that relaxers might cause cancer and other health problems.

But regulators have been slow to act, physicians have been reluctant to take up the cause, and racism continues to dictate fashion standards that make it tough for women to quit relaxers, products so addictive they’re known as “creamy crack.”

Michelle Obama straightened her hair when Barack Obama served as president because she believed Americans were “not ready” to see her in braids, the former first lady said after leaving the White House. The U.S. military still prohibited popular Black hairstyles such as dreadlocks and twists while the nation’s first Black president was in office.

California in 2019 became the first of nearly two dozen states to ban race-based hair discrimination. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed similar legislation, known as the CROWN Act, for Creating a Respectful and Open World for Natural Hair. But the bill failed in the Senate.

The need for legislation underscores the challenges Black girls and women face at school and in the workplace.

“You have to pick your struggles,” said Atlanta-based surgical oncologist Ryland J. Gore, MD. She informs her breast cancer patients about the increased cancer risk from relaxers. Despite her knowledge, however, Dr. Gore continues to use chemical straighteners on her own hair, as she has since she was about 7 years old.

“Your hair tells a story,” she said.

In conversations with patients, Dr. Gore sometimes talks about how African American women once wove messages into their braids about the route to take on the Underground Railroad as they sought freedom from slavery.

“It’s just a deep discussion,” one that touches on culture, history, and research into current hairstyling practices, she said. “The data is out there. So patients should be warned, and then they can make a decision.”

The first hint of a connection between hair products and health issues surfaced in the 1990s. Doctors began seeing signs of sexual maturation in Black babies and young girls who developed breasts and pubic hair after using shampoo containing estrogen or placental extract. When the girls stopped using the shampoo, the hair and breast development receded, according to a study published in the journal Clinical Pediatrics in 1998.

Since then, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers have linked chemicals in hair products to a variety of health issues more prevalent among Black women – from early puberty to preterm birth, obesity, and diabetes.

In recent years, researchers have focused on a possible connection between ingredients in chemical relaxers and hormone-related cancers, like the one Ms. Hughes developed, which tend to be more aggressive and deadly in Black women.

A 2017 study found White women who used chemical relaxers were nearly twice as likely to develop breast cancer as those who did not use them. Because the vast majority of the Black study participants used relaxers, researchers could not effectively test the association in Black women, said lead author Adana Llanos, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, New York.

Researchers did test it in 2020.

The so-called Sister Study, a landmark National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences investigation into the causes of breast cancer and related diseases, followed 50,000 U.S. women whose sisters had been diagnosed with breast cancer and who were cancer-free when they enrolled. Regardless of race, women who reported using relaxers in the prior year were 18% more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer. Those who used relaxers at least every 5-8 weeks had a 31% higher breast cancer risk.

Nearly 75% of the Black sisters used relaxers in the prior year, compared with 3% of the non-Hispanic White sisters. Three-quarters of Black women self-reported using the straighteners as adolescents, and frequent use of chemical straighteners during adolescence raised the risk of premenopausal breast cancer, a 2021 NIH-funded study in the International Journal of Cancer found.

Another 2021 analysis of the Sister Study data showed sisters who self-reported that they frequently used relaxers or pressing products doubled their ovarian cancer risk. In 2022, another study found frequent use more than doubled uterine cancer risk.

After researchers discovered the link with uterine cancer, some called for policy changes and other measures to reduce exposure to chemical relaxers.

“It is time to intervene,” Dr. Llanos and her colleagues wrote in a Journal of the National Cancer Institute editorial accompanying the uterine cancer analysis. While acknowledging the need for more research, they issued a “call for action.”

No one can say that using permanent hair straighteners will give you cancer, Dr. Llanos said in an interview. “That’s not how cancer works,” she said, noting that some smokers never develop lung cancer, despite tobacco use being a known risk factor.

The body of research linking hair straighteners and cancer is more limited, said Dr. Llanos, who quit using chemical relaxers 15 years ago. But, she asked rhetorically, “Do we need to do the research for 50 more years to know that chemical relaxers are harmful?”

Charlotte R. Gamble, MD, a gynecological oncologist whose Washington, D.C., practice includes Black women with uterine and ovarian cancer, said she and her colleagues see the uterine cancer study findings as worthy of further exploration – but not yet worthy of discussion with patients.

“The jury’s out for me personally,” she said. “There’s so much more data that’s needed.”

Meanwhile, Dr. James-Todd and other researchers believe they have built a solid body of evidence.

“There are enough things we do know to begin taking action, developing interventions, providing useful information to clinicians and patients and the general public,” said Traci N. Bethea, PhD, assistant professor in the Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities Research at Georgetown University.

Responsibility for regulating personal-care products, including chemical hair straighteners and hair dyes – which also have been linked to hormone-related cancers – lies with the Food and Drug Administration. But the FDA does not subject personal-care products to the same approval process it uses for food and drugs. The FDA restricts only 11 categories of chemicals used in cosmetics, while concerns about health effects have prompted the European Union to restrict the use of at least 2,400 substances.

In March, Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) and Shontel Brown (D-Ohio) asked the FDA to investigate the potential health threat posed by chemical relaxers. An FDA representative said the agency would look into it.

Natural hairstyles are enjoying a resurgence among Black girls and women, but many continue to rely on the creamy crack, said Dede Teteh, DrPH, assistant professor of public health at Chapman University, Irvine, Calif.

She had her first straightening perm at 8 and has struggled to withdraw from relaxers as an adult, said Dr. Teteh, who now wears locs. Not long ago, she considered chemically straightening her hair for an academic job interview because she didn’t want her hair to “be a hindrance” when she appeared before White professors.

Dr. Teteh led “The Cost of Beauty,” a hair-health research project published in 2017. She and her team interviewed 91 Black women in Southern California. Some became “combative” at the idea of quitting relaxers and claimed “everything can cause cancer.”

Their reactions speak to the challenges Black women face in America, Dr. Teteh said.

“It’s not that people do not want to hear the information related to their health,” she said. “But they want people to share the information in a way that it’s really empathetic to the plight of being Black here in the United States.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF – the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.

FDA approves first pill for postpartum depression

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a condition that affects an estimated one in seven mothers in the United States.

The pill, zuranolone (Zurzuvae), is a neuroactive steroid that acts on GABAA receptors in the brain responsible for regulating mood, arousal, behavior, and cognition, according to Biogen, which, along with Sage Therapeutics, developed the product. The recommended dose for Zurzuvae is 50 mg taken once daily for 14 days, in the evening with a fatty meal, according to the FDA.

Postpartum depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated. Many mothers are hesitant to reveal their symptoms to family and clinicians, fearing they’ll be judged on their parenting. A 2017 study found that suicide accounted for roughly 5% of perinatal deaths among women in Canada, with most of those deaths occurring in the first 3 months in the year after giving birth.

“Postpartum depression is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition in which women experience sadness, guilt, worthlessness – even, in severe cases, thoughts of harming themselves or their child. And, because postpartum depression can disrupt the maternal-infant bond, it can also have consequences for the child’s physical and emotional development,” Tiffany R. Farchione, MD, director of the division of psychiatry at the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement about the approval. “Having access to an oral medication will be a beneficial option for many of these women coping with extreme, and sometimes life-threatening, feelings.”

The other approved therapy for postpartum depression is the intravenous agent brexanolone (Zulresso; Sage). But the product requires prolonged infusions in hospital settings and costs $34,000.

FDA approval of Zurzuvae was based in part on data reported in a 2023 study in the American Journal of Psychiatry, which showed that the drug led to significantly greater improvement in depressive symptoms at 15 days compared with the placebo group. Improvements were observed on day 3, the earliest assessment, and were sustained at all subsequent visits during the treatment and follow-up period (through day 42).

Patients with anxiety who received the active drug experienced improvement in related symptoms compared with the patients who received a placebo.

The most common adverse events reported in the trial were somnolence and headaches. Weight gain, sexual dysfunction, withdrawal symptoms, and increased suicidal ideation or behavior were not observed.

The packaging for Zurzuvae will include a boxed warning noting that the drug can affect a user’s ability to drive and perform other potentially hazardous activities, possibly without their knowledge of the impairment, the FDA said. As a result, people who use Zurzuvae should not drive or operate heavy machinery for at least 12 hours after taking the pill.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

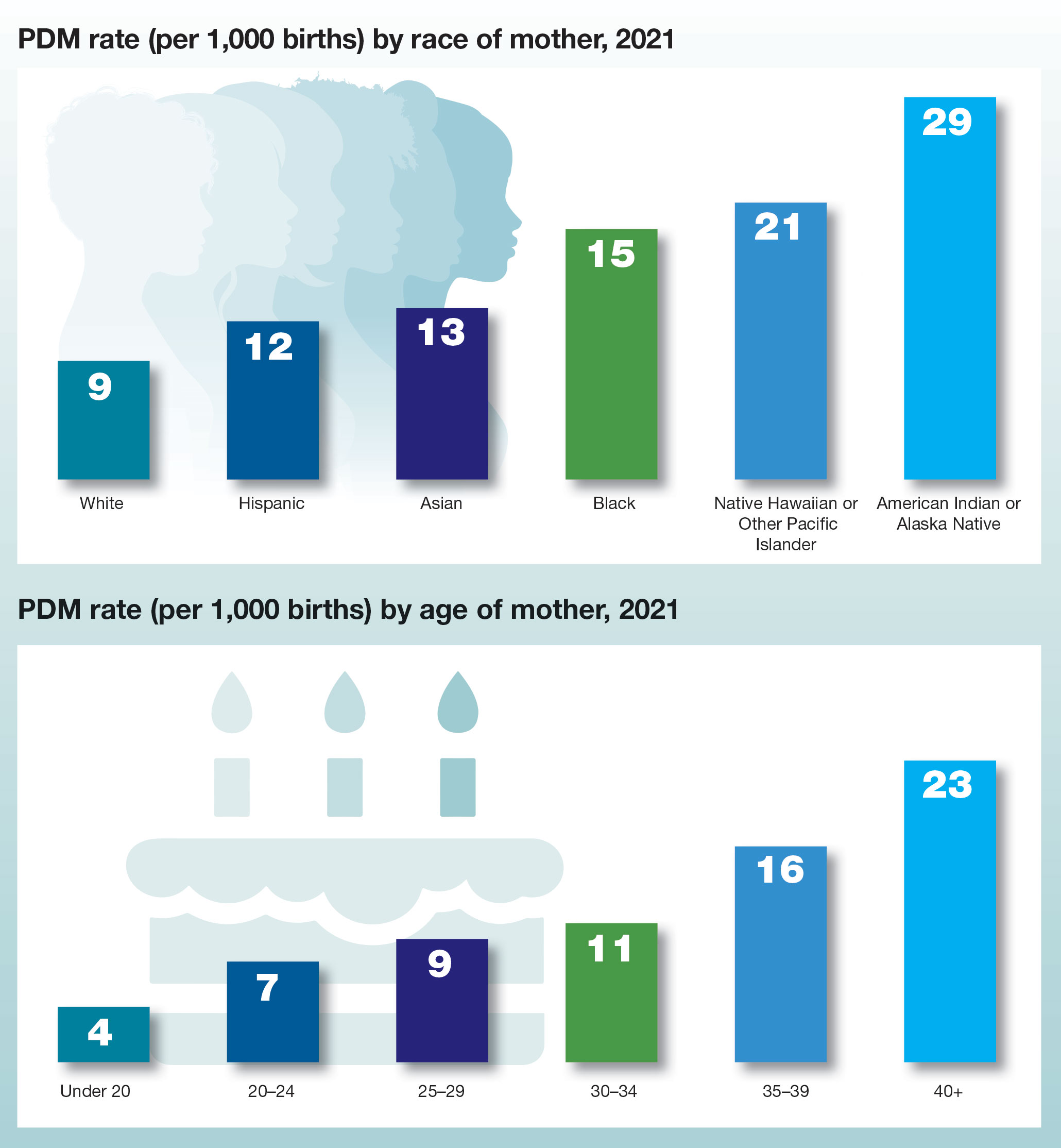

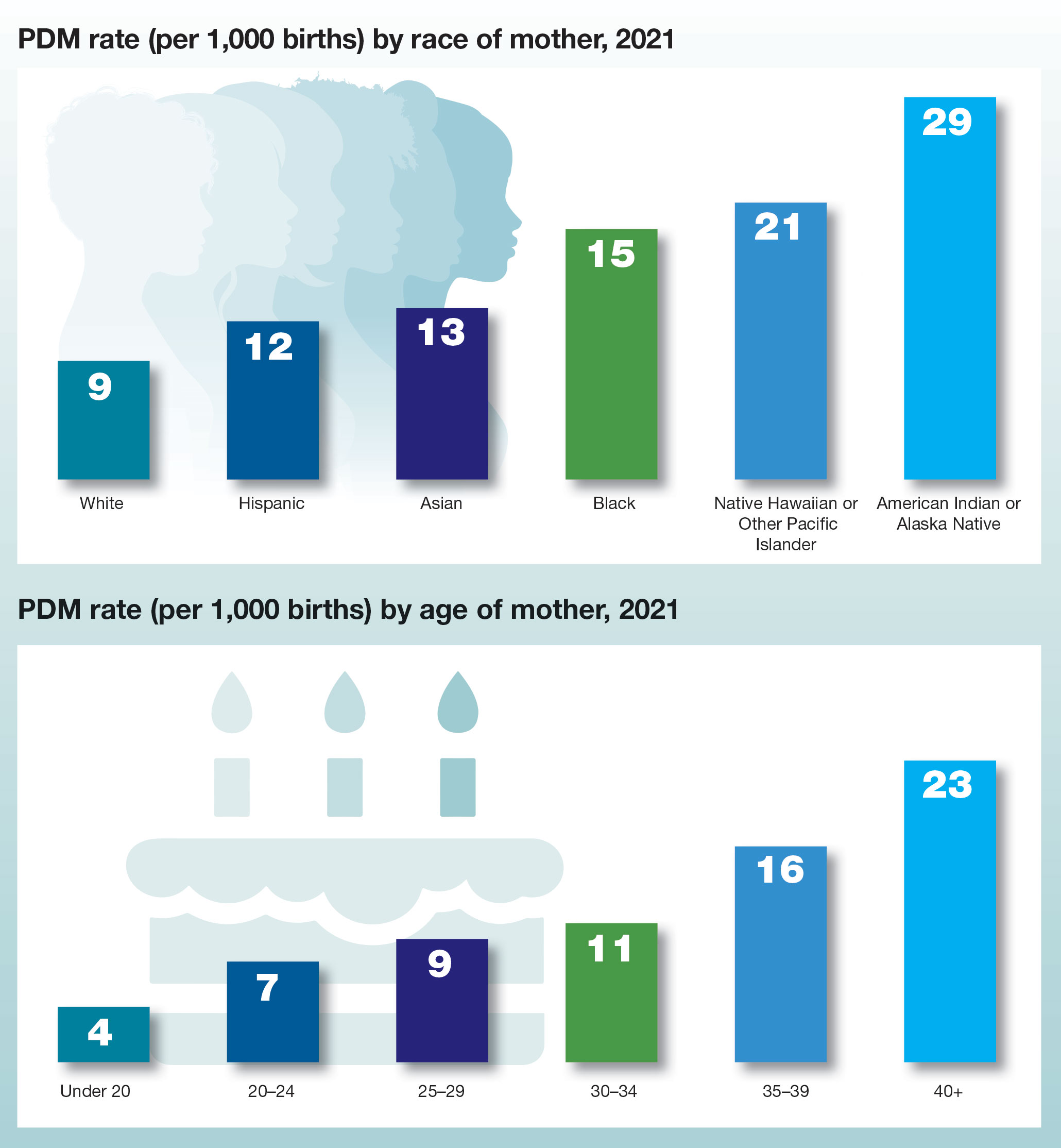

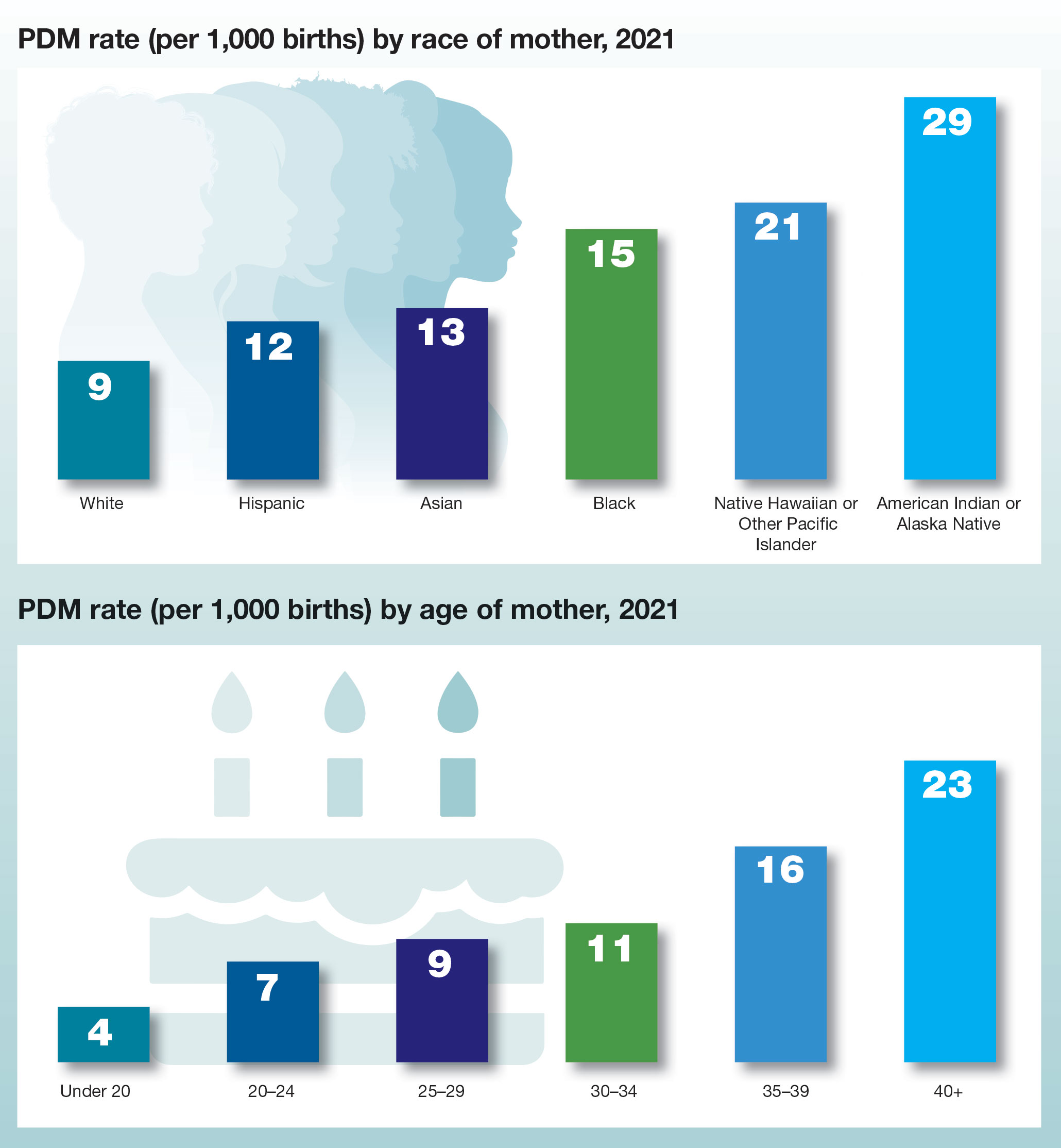

Trends in prepregnancy diabetes rates in the United States, 2016 -2021

Managing clinician burnout: Challenges and opportunities

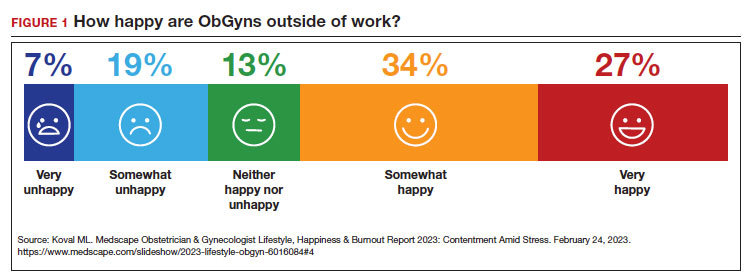

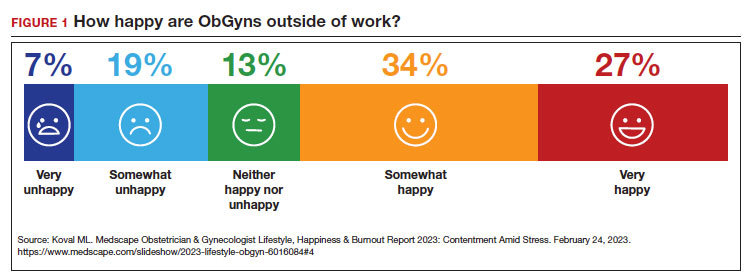

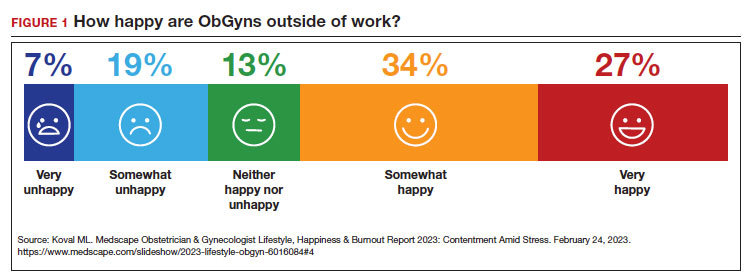

Physicians have some of the highest rates of burnout among all professions.1 Complicating matters is that clinicians (including residents)2 may avoid seeking treatment out of fear it will affect their license or privileges.3 In this article, we consider burnout in greater detail, as well as ways of successfully addressing the level of burnout in the profession (FIGURE 1), including steps individual practitioners, health care entities, and regulators should consider to reduce burnout and its harmful effects.

How burnout becomes a problem

Six general factors are commonly identified as leading to clinician career dissatisfaction and burnout:4

1. work overload

2. lack of autonomy and control

3. inadequate rewards, financial and otherwise

4. work-home schedules

5. perception of lack of fairness

6. values conflict between the clinician and employer (including a breakdown of professional community).

At the top of the list of causes of burnout is often “administrative and bureaucratic headaches.”5 More specifically, electronic health records (EHRs), including computerized order entry, is commonly cited as a major cause of burnout.6,7 According to some studies, clinicians spend as much as 49% of working time doing clerical work,8 and studies found the extension of work into home life.9

Increased measurement of performance metrics in health care services are a significant contributor to physician burnout.10 These include pressure to see more patients, perform more procedures, and respond quickly to patient requests (eg, through email).7 As we will see, medical malpractice cases, or the risk of such cases, have also played a role in burnout in some medical specialties.11 The pandemic also contributed, at least temporarily, to burnout.12,13

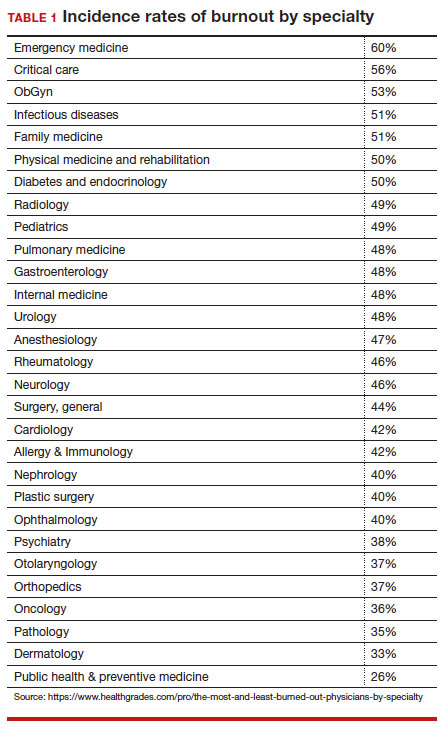

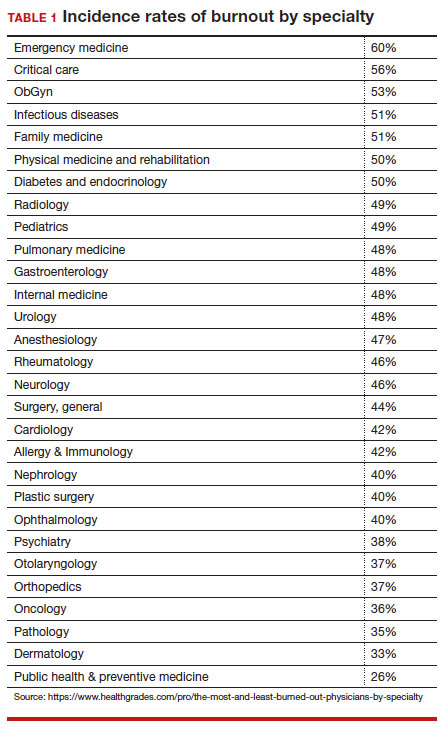

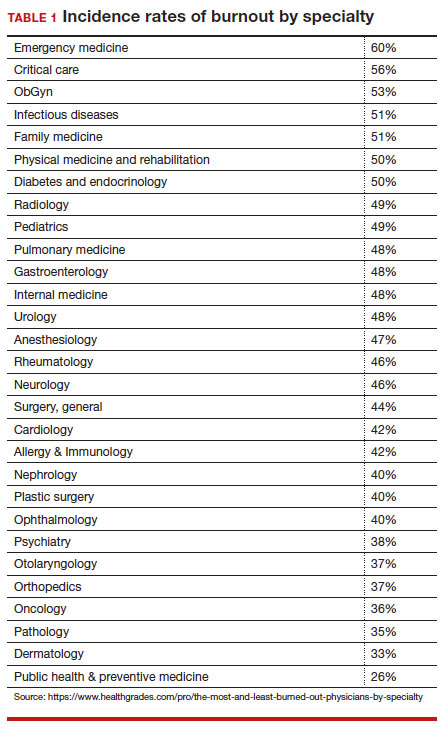

Rates of burnout among physicians are notably higher than among the general population14 or other professions.6 Although physicians have generally entered clinical practice with lower rates of burnout than the general population,15 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reports that 40% to 75% of ObGyns “experience some form of professional burnout.”16,17 Other source(s) cite that 53% of ObGyns report burnout (TABLE 1).

Code QD85

Burnout is a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterized by 3 dimensions:

- feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion

- increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job

- a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment. Burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context and should not be applied to describe experiences in other areas of life. Exclusions to burnout diagnosis include adjustment disorder, disorders specifically associated with stress, anxiety or fear-related disorders, and mood disorders.

Reference

1. International Classification of Diseases Eleventh Revision (ICD-11). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2022.

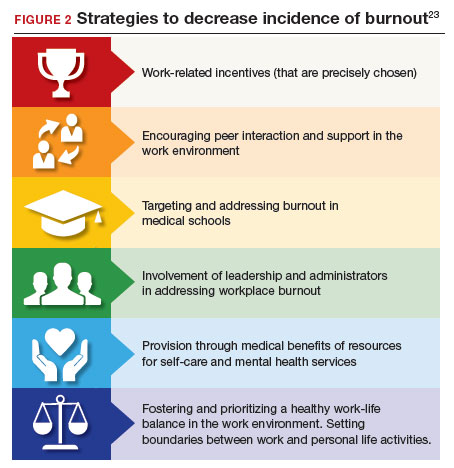

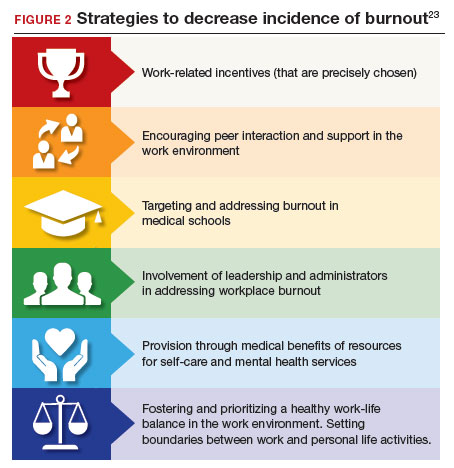

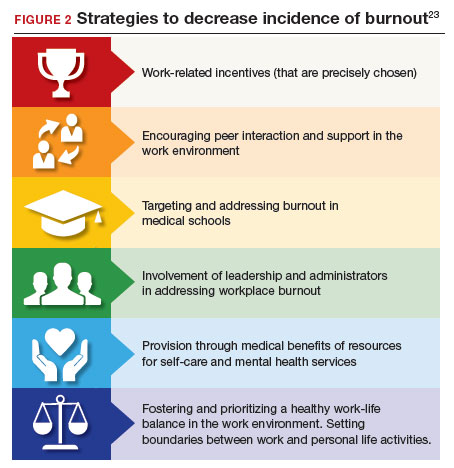

Burnout undoubtedly contributes to professionals leaving practice, leading to a significant shortage of ObGyns.18 It also raises several significant legal concerns. Despite the enormity and seriousness of the problem, there is considerable optimism and assurance that the epidemic of burnout is solvable on the individual, specialty, and profession-wide levels. ACOG and other organizations have made suggestions for physicians, the profession, and to health care institutions for reducing burnout.19 This is not to say that solutions are simple or easy for individual professionals or institutions, but they are within the reach of the profession (FIGURE 2).

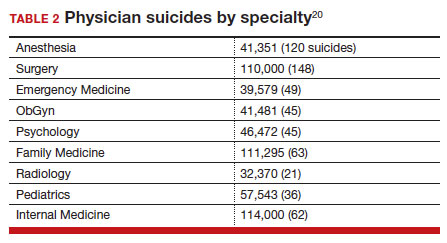

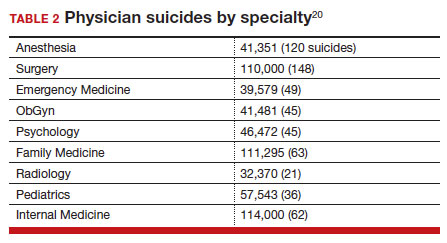

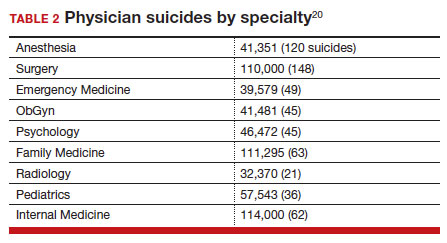

Suicide among health care professionals is one other concern (TABLE 2)20 and theoretically can stem from burnout, depression, and other psychosocial concerns.

Costs of clinician burnout

Burnout is endemic among health care providers, with numerous studies detailing the professional, emotional, and financial costs. Prior to the pandemic, one analysis of nationwide fiscal costs associated with burnout estimated an annual cost of $4.6B due to physician turnover and reduced clinical hours.21 The COVID-19 epidemic has by all accounts worsened rates of health care worker burnout, particularly for those in high patient-contact positions.22

Female clinicians appear to be differentially affected; in one recent study women reported symptoms of burnout at twice the rate of their male counterparts.23 Whether burnout rates will return to pre-pandemic levels remains an open question, but since burnout is frequently related to one’s own assessment of work-life balance, it is possible that a longer term shift in burnout rates associated with post-pandemic occupational attitudes will be observed.

Combining factors contribute to burnout

Burnout is a universal occupational hazard, but extant data suggest that physicians and other health care providers may be at higher risk. Among physicians, younger age, female gender, and front-line specialty status appear associated with higher burnout rates.24 Given that ObGyn physicians are overwhelmingly female (60% of physicians and 86% of residents),25,26 gender-related burnout factors exist alongside other specific occupational burnout risks. While gender parity has been achieved among health care providers, gender disparities persist in terms of those in leadership positions, compensation, and other factors.22

The smattering of evidence suggesting that ObGyns have higher rates of burnout than many other specialties is understandable given the unique legal challenges confronting ObGyn practice. This may be of special significance because ObGyn malpractice insurance rates are among the highest of all specialties.27 The overall shortage of ObGyns has been exacerbated by the demonstrated negative effects on training and workforce representation stemming from recent legislation that has the effect of criminalizing certain aspects of ObGyn practice;28 for instance, uncertainty regarding abortion regulations.

These negative effects are particularly heightened in states in which the law is in flux or where there are continuing efforts to substantially limit access to abortion. The efforts to increase civil and even criminal penalties related to abortion care challenge ObGyns’ professional practices, as legal rules are frequently changing. In some states, ObGyns may face additional workloads secondary to a flight of ObGyns from restrictive jurisdictions in addition to legal and professional repercussions. In a small study of 19 genetic counselors dealing with restrictive legislation in the state of Ohio,29 increased stress and burnout rates were identified as a consequence of practice uncertainties under this legislation. It is certain that other professionals working in reproductive health care are similarly affected.30

The programs provide individual resources to providers in distress, periodically survey initiatives at Stanford to assess burnout at the organizational level, and provide input designed to spur organizational change to reduce the burden of burnout. Ways that they build community and connections include:

- Live Story Rounds events (as told by Stanford Medicine physicians)

- Commensality Groups (facilitated small discussion groups built around tested evidence)

- Aim to increase sense of connection and collegiality among physicians and build comradery at work

- CME-accredited physician wellness forum, including annual doctor’s day events

Continue to: Assessment of burnout...

Assessment of burnout

Numerous scales for the assessment of burnout exist. Of these, the 22-item Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) is the best studied. The MBI is a well-investigated tool for assessing burnout. The MBI consists of 3 major subscales measuring overall burnout, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment. It exists in numerous forms. For instance, the MBI-HSS (MP), adapted for medical personnel, is available. However, the most commonly used form for assessing burnout in clinicians is the MBI-HHS (Human Services Survey); approximately 85% of all burnout studies examined in a recent meta-analysis used this survey version.31 As those authors commented, while burnout is a recognized phenomenon, a great deal of variability in study design, interpretation of subscale scores, and sample selection makes generalizations regarding burnout difficult to assess.

The MBI in various forms has been extensively used over the past 40 years to assess burnout amongst physicians and physicians in training. While not the only instrument designed to measure such factors, it is by far the most prevalent. Williamson and colleagues32 compared the MBI with several other measures of quality of life and found good correlation between the various instruments used, a finding replicated by other studies.33 Brady and colleagues compared item responses to the Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index and the Min-Z Single-item Burnout scale (a 1-item screening measure) to MBI’s Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization subscales. Basing their findings on a survey of more than 1,300 physicians, they found that all analyzed scales were significantly correlated with such adverse outcomes as depression, distress, or intent to leave the profession.

It is important to note that most surveys of clinician burnout were conducted prior to the pandemic. While the psychometric analyses of the MBI and other scales are likely still germane, observed rates of clinician burnout have likely increased. Thus, comparisons of pre- and post-pandemic studies should factor in an increase in the incidence and prevalence of burnout.

Management strategies

In general, there are several interventions for managing burnout34:

- individual-focused (including self-care and communications-skills workshops)

- mindfulness training

- yoga

- meditation

- organizational/structural (workload reduction, schedule realignment, teamwork training, and group-delivered stress management interventions)

- combination(s) of the above.

There is little evidence to suggest that any particular individual intervention (whether delivered in individual or group-based formats) is superior to any other in treating clinician burnout. A recent analysis of 24 studies employing mindfulness-based interventions demonstrated generally positive results for such interventions.35 Other studies have also found general support for mindfulness-based interventions, although mindfulness is often integrated with other stress-reduction techniques, such as meditation, yoga, and communication skills. Such interventions are nonspecific but generally effective.

An accumulation of evidence to date suggests that a combination of individual and organizational interventions is most effective in combatting clinician burnout. No individual intervention can be successful without addressing root causes, such as overscheduling, lack of organizational support, and the effect of restrictive legislation on practice.

Several large teaching hospitals have established programs to address physician and health care provider burnout. Notable among these is the Stanford University School of Medicine’s WellMD and WellPhD programs (https://wellmd.stanford.edu/about.html). These programs were described by Olson and colleagues36 as using a model focused on practice efficiency, organizational culture, and personal resilience to enhance physicians’ well-being. (See “Aspects of the WellMD and WellPhD programs from Stanford University.”)

A growing number of institutions have established burnout programs to support physicians experiencing work/life imbalances and other aspects of burnout.37 In general, these share common features of assessment, individual and/or group intervention, and organizational change. Fear of repercussion may be one factor preventing physicians from seeking individual treatment for burnout.38 Importantly, they emphasize the need for professional confidentiality when offering treatment to patients within organizational settings. Those authors also reported that a focus on organizational engagement may be an important factor in addressing burnout in female physicians, as they tend to report lower levels of organizational engagement.

Continue to: Legal considerations...

Legal considerations

Until recently, physician burnout “received little notice in the legal literature.”39 Although there have been burnout legal consequences in the past, the legal issues are now becoming more visible.40

Medical malpractice

A well-documented consequence of burnout is an increase in errors.14 Medical errors, of course, are at the heart of malpractice claims. Technically, malpractice is medical or professional negligence. It is the breach of a duty owed by the physician, or other provider, or organization (defendant) to the patient, which causes injury to the plaintiff/patient.41

“Medical error” is generally a meaningful deviation from the “standard of care” or accepted medical practice.42 Many medical errors do not cause injury to the patient; in those cases, the negligence does not result in liability. In instances in which the negligence causes harm, the clinician and health care facility may be subject to liability for that injury. Fortunately, however, for a variety of reasons, most harmful medical errors do not result in a medical malpractice claim or lawsuit. The absence of a good clinician-patient relationship is likely associated with an increased inclination of a patient to file a malpractice action.43Clinician burnout may, therefore, contribute to increased malpractice claims in two ways. First, burnout likely leads to increased medical errors, perhaps because burnout is associated with lower concentration, inattention, reduced cognitive vigilance, and fatigue.8,44 It may also lead to less time with patients, reduced patient empathy, and lower patient rapport, which may make injured patients more likely to file a claim or lawsuit.45 Because the relationshipbetween burnout and medical error is bidirectional, malpractice claims tend to increase burnout, which increases error. Given the time it takes to resolve most malpractice claims, the uncertainty of medical malpractice may be especially stressful for health care providers.46,47

Burnout is not a mitigating factor in malpractice. Our sympathies may go out to a professional suffering from burnout, but it does not excuse or reduce liability—it may, indeed, be an aggravating factor. Clinicians who can diagnose burnout and know its negative consequences but fail to deal with their own burnout may be demonstrating negligence if there has been harm to a patient related to the burnout.48

Institutional or corporate liability to patients

Health care institutions have obligations to avoid injury to patients. Just as poorly maintained medical equipment may harm patients, so may burned-out professionals. Therefore, institutions have some obligation to supervise and avoid the increased risks to patients posed by professionals suffering from burnout.

Respondeat superior and institutional negligence. Institutional liability may arise in two ways, the first through agency, or respondeat superior. That is, if the physician or other professional is an employee (or similar agent) of the health care institution, that institution is generally responsible for the physician’s negligence during the employment.49 Even if the physician is not an employee (for example, an independent contractor providing care or using the hospital facilities), the health care facility may be liable for the physician’s negligence.50 Liability may occur, for example, if the health care facility was aware that the physician was engaged in careless practice or was otherwise a risk to patients but the facility did not take steps to avoid those risks.51 The basis for liability is that the health care organization owes a duty to patients to take reasonable care to ensure that its facilities are not used to injure patients negligently.52 Just as it must take care that unqualified physicians are not granted privileges to practice, it also must take reasonable steps to protect patients when it is aware (through nurses or other agents) of a physician’s negligent practice.

In one case, for example, the court found liability where a staff member had “severe” burnout in a physician’s office and failed to read fetal monitoring strips. The physician was found negligent for relying on the staff member who was obviously making errors in interpretation of fetal distress.53

Continue to: Legal obligations of health care organizations to physicians and others...

Legal obligations of health care organizations to physicians and others

In addition to obligations to patients, health care organizations may have obligations to employees (and others) at risk for injury. For example, assume a patient is diagnosed with a highly contagious disease. The health care organization would be obligated to warn, and take reasonable steps to protect, the staff (employees and independent contractors) from being harmed from exposure to the disease. This principle may apply to coworkers of employees with significant burnout, thereby presenting a danger in the workplace. The liability issue is more difficult for employees experiencing job-related burnout themselves. Organizations generally compensate injured employees through no-fault workers’ compensation (an insurance-like system); for independent contractors, the liability is usually through a tort claim (negligence).54

In modern times, a focus has been on preventing those injuries, not just providing compensation after injuries have occurred. Notably, federal and state occupational health and safety laws (particularly the Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA]) require most organizations (including those employing health care providers) to take steps to mitigate various kinds of worker injuries.55

Although these worker protections have commonly been applied to hospitals and other health care providers, burnout has not traditionally been a significant concern in federal or state OSHA enforcement. For example, no formal federal OSHA regulations govern work-related burnout. Regulators, including OSHA, are increasingly interested in burnout that may affect many employees. OSHA has several recommendations for reducing health care work burnout.56 The Surgeon General has expressed similar concerns.57 The federal government recently allocated $103 million from the American Rescue Plan to address burnout among health care workers.58 Also, OSHA appears to be increasing its oversight of healthcare-institution-worker injuries.55

Is burnout a “disability”?

The federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and similar state laws prohibit discrimination based on disability.59 A disability is defined as a “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities” or “perceived as having such an impairment.”60 The initial issue is whether burnout is a “mental impairment.” As noted earlier, it is not officially a “medical condition.”61 To date, the United Nations has classified it as an “occupational phenomenon.”62 It may, therefore, not qualify under the ADA, even if it “interferes with a major life activity.” There is, however, some movement toward defining burnout as a mental condition. Even if defined as a disability, there would still be legal issues of how severe it must be to qualify as a disability and the proper accommodation. Apart from the legal definition of an ADA disability, as a practical matter it likely is in the best interest of health care facilities to provide accommodations that reduce burnout. A number of strategies to decrease the incidence of burnout include the role of health care systems (FIGURE 2).

In conclusion we look at several things that can be done to “treat” or reduce burnout. That effort requires the cooperation of physicians and other providers, health care facilities, training programs, licensing authorities, and professional organizations. See suggestions below.

Conclusion

There are many excellent suggestions for reducing burnout and improving patient care and practitioner satisfaction.63-65 We conclude with a summary of some of these suggestions for individual practitioners, health care organizations, the profession, and licensing. It is worth remembering, however, that it will require the efforts of each area to reduce burnout substantially.

For practitioners:

- Engage in quality coaching/therapy on mindfulness and stress management.

- Practice self-care, including exercise and relaxation techniques.

- Make work-life balance a priority.

- Take opportunities for collegial social and professional discussions.

- Prioritize (and periodically assess) your own professional satisfaction and burnout risk.

- Smile—enjoy a sense of humor (endorphins and cortisol).

For health care organizations:

- Urgently work with vendors and regulators to revise electronic health records to reduce their substantial impact on burnout.

- Reduce physicians’ time on clerical and administrative tasks (eg, by enhancing the use of quality AI, scribes, and automated notes from appointments. (This may increase the time they spend with patients.) Eliminate “pajama-time” charting.

- Provide various kinds of confidential professional counseling, therapy, and support related to burnout prevention and treatment, and avoid any penalty or stigma related to their use.

- Provide reasonable flexibility in scheduling.

- Routinely provide employees with information about burnout prevention and services.

- Appoint a wellness officer with authority to ensure the organization maximizes its prevention and treatment services.

- Constantly seek input from practitioners on how to improve the atmosphere for practice to maximize patient care and practitioner satisfaction.

- Provide ample professional and social opportunities for discussing and learning about work-life balance, resilience, intellectual stimulation, and career development.

For regulators, licensors, and professional organizations:

- Work with health care organizations and EHR vendors to substantially reduce the complexity, physician effort, and stress associated with those record systems. Streamlining should, in the future, be part of formally certifying EHR systems.

- Reduce the administrative burden on physicians by modifying complex regulations and using AI and other technology to the extent possible to obtain necessary reimbursement information.

- Eliminate unnecessary data gathering that requires practitioner time or attention.

- Licensing, educational, and certifying bodies should eliminate any questions regarding the diagnosis or treatment of mental health and focus on current (or very recent) impairments.

- Seek funding for research on burnout prevention and treatment.

Dr. H is a 58-year-old ObGyn who, after completing residency, went into solo practice. The practice grew, and Dr. H found it increasingly more challenging to cover, especially the obstetrics sector. Dr. H then merged the practice with a group of 3 other ObGyns. Their practice expanded, and began recruiting recent residency graduates. In time, the practice was bought out by the local hospital health care system. Dr. H was faced with complying with the rules and regulations of that health care system. The electronic health record (EHR) component proved challenging, as did the restrictions on staff hiring (and firing), but Dr. H did receive a paycheck each month and complied with it all. The health care system administrators had clear financial targets Dr. H was to meet each quarter, which created additional pressure. Dr. H used to love being an OB and providing excellent care for every patient, but that sense of accomplishment was being lost.

Dr. H increasingly found it difficult to focus because of mind wandering, especially in the operating room (OR). Thoughts occurred about retirement, the current challenges imposed by “the new way of practicing medicine” (more focused on financial productivity restraints and reimbursement), and EHR challenges. Then Dr. H’s attention would return to the OR case at hand. All of this resulted in considerable stress and emotional exhaustion, and sometimes a sense of being disconnected. A few times, colleagues or nurses had asked Dr. H if everything was “okay,” or if a break would help. Dr. H made more small errors than usual, but Dr. H’s self-assessment was “doing an adequate job.” Patient satisfaction scores (collected routinely by the health care system) declined over the last 9 months.

Six months ago, Dr. H finished doing a laparoscopic total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and got into the right uterine artery. The estimated blood loss was 3,500 mL. Using minimally invasive techniques, Dr. H identified the bleeder and, with monopolar current, got everything under control. The patient went to the post-anesthesia care unit, and all appeared to be in order. Her vital signs were stable, and she was discharged home the same day.

The patient presented 1 week later with lower abdominal and right flank pain. Dr. H addressed the problem in the emergency department and admitted the patient for further evaluation and urology consultation. The right ureter was damaged and obstructed; ultimately, the urologist performed a psoas bladder hitch. The patient recovered slowly, lost several weeks of work, experienced significant pain, and had other disruptions and costs. Additional medical care related to the surgery is ongoing. A health care system committee asked Dr. H to explain the problem. Over the last 6 months, Dr. H’s frustration with practice and being tired and disconnected have increased.

Dr. H has received a letter from a law firm saying that he and the health care system are being sued for malpractice focused on an iatrogenic ureter injury. The letter names two very reputable experts who are prepared to testify that the patient’s injury resulted from clear negligence. Dr. H has told the malpractice carrier absolutely not to settle this case—it is “a sham— without merit.” The health care system has asked Dr. H to take a “burnout test.”

Legal considerations

Dr. H exhibits relatively clear signs of professional burnout. The fact that there was a bad outcome while Dr. H was experiencing burnout is not proof of negligence (or, breach of duty of care to the patient). Nor is it a defense or mitigation to any malpractice that occurred.

In the malpractice case, the plaintiff will have the burden of proving that Dr. H’s treatment was negligent in that it fell below the standard of care. Even if it was a medical error, the question is whether it was negligence. If the patient/plaintiff, using expert witnesses, can prove that Dr. H fell below the standard of care that caused injury, Dr. H may be liable for the resulting extra costs, loss of income, and pain and suffering resulting from the negligent care.

The health care system likely will also be responsible for Dr. H’s negligence, either through respondeat superior (for example, if Dr. H is an employee) or for its own negligence. The case for its negligence is that the nurses and assistants had repeatedly seen him making errors and becoming disengaged (to the extent that they asked Dr. H if “everything is okay” or if a break would help). Furthermore, Dr. H’s patient satisfaction scores have been declining for several months. The plaintiff will argue that Dr. H exhibited classic burnout symptoms with the attendant risks of medical errors. However, the health care system did not take action to protect patients or to assist Dr. H. In short, one way or another, there is some likelihood that the health care system may also be liable if patient injuries are found to have been caused by negligence.

At this point, the health care system also faces the question of how to work with Dr. H in the future. The most pressing question is whether or not to allow Dr. H to continue practicing. If, as it appears, Dr. H is dealing with burnout, the pressure of the malpractice claim could well increase the probability of other medical mistakes. The institution has asked Dr. H to take a burnout test, but it is unclear where things go if the test (as likely) demonstrates significant burnout. This is a counseling and human relations question, at least as much as a legal issue, and the institution should probably proceed in that way—which is, trying to understand and support Dr. H and determining what can be done to address the burnout. At the same time, the system must reasonably assess Dr. H’s fitness to continue practicing as the matters are resolved. Almost everyone shares the goal to provide every individual and corporate opportunity for Dr. H to deal with burnout issues and return to successful practice.

Dr. H will be represented in the malpractice case by counsel provided through the insurance carrier. However, Dr. H would be well advised to retain a trusted and knowledgeable personal attorney. For example, the instruction not to consider settlement is likely misguided, but Dr. H needs to talk with an attorney that Dr. H has chosen and trusts. In addition, the attorney can help guide Dr. H through a rational process of dealing with the health care system, putting the practice in order, and considering the options for the future.

The health care system should reconsider its processes to deal with burnout to ensure the quality of care, patient satisfaction, professional retention, and economic stability. Several burnoutresponse programs have had success in achieving these goals.

What’s the Verdict?

Dr. H received good mental health, legal, and professional advice. As a result, an out of court settlement was reached following pretrial discovery. Dr. H has continued consultation regarding burnout and has returned to productive practice.

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clinic Proceed. 2019;94:1681-1694.

- Smith R, Rayburn W. Burnout in obstetrician-gynecologists. Its prevalence, identification, prevention, and reversal. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2021;48:231-245. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ogc.2021.06.003

- Patti MG, Schlottmann F, Sarr MG. The problem of burnout among surgeons. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:403-404. doi:10.1001 /jamasurg.2018.0047

- Carrau D, Janis JE. Physician burnout: solutions for individuals and organizations. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Global Open. 2021;91-97.

- Southwick R. The key to fixing physician burnout is the workplace not the worker. Contemporary Ob/Gyn. March 13, 2023.

- Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, et al. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sciences. 2018;8:98.

- Melnick ER, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky CA, et al. The association between perceived electronic health record usability and professional burnout among US physicians. Mayo Clinic Proceed. 2020;95:476-487.

- Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317:901-902. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0076

- Ommaya AK, Cipriano PF, Hoyt DB, et al. Care-centered clinical documentation in the digital environment: Solutions to alleviate burnout. National Academy of Medicine Perspectives. 2018.

- Hartzband P, Groopman J. Physician burnout, interrupted. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2485-2487. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://nam .edu/care

- Ji YD, Robertson FC, Patel NA, et al. Assessment of risk factors for suicide among US health care professionals. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:713-721. centered-clinical-documentation-digital -environment-solutions-alleviate-burnout/

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians during the first 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clinic Proceed. 2022;97:2248-2258.

- Herber-Valdez C, Kupesic-Plavsic S. Satisfaction and shortfall of OB-GYN physicians and radiologists. J. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;15:387-392.

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Burnout among health care professionals: a call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. National Academy of Medicine Perspectives. Accessed July 5, 2017. https://iuhcpe.org/file_manager/1501524077-Burnout -Among-Health-Care-Professionals-A-Call-to-Explore-and -Address-This-Underrecognized-Threat.pdf

- Olson KD. Physician burnout—a leading indicator of health system performance? Mayo Clinic Proceed. 2017;92: 1608-1611.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Why obgyns are burning out. October 28, 2019. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.acog.org/news/news-articles/2019/10/why-ob -gyns-are-burning-out#:~:text=A%202017%20report%20 by%20the,exhaustion%20or%20lack%20of%20motivation

- Peckham C. National physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape. January 17, 2018. https://nap. nationalacademies.org/catalog/25521/taking-action -against-clinician-burnout-a-systems-approach-to -professional

- Marsa L. Labor pains: The OB-GYN shortage. AAMC News. Nov. 15, 2018. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.aamc.org /news-insights/labor-pains-ob-gyn-shortage

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Coping with the stress of medical professional liability litigation. ACOG Committee Opinion. February 2005;309:453454. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.acog.org/clinical /clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2013/01 /coping-with-the-stress-of-medical-professional-liability -litigation

- Reith TP. Burnout in United States healthcare professionals: a narrative review. Cureus. 2018;10:e3681. doi: 10.7759 /cureus.3681

- Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;4:784-790.

- Sullivan D, Sullivan V, Weatherspoon D, et al. Comparison of nurse burnout, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Clin North Am. 2022;57:79-99. doi: 10.1016 /j.cnur.2021.11.006

- Chandawarkar A, Chaparro JD. Burnout in clinicians. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2021;51:101-104. https ://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2021.101104

- Brady KJS, Sheldrick RC, Ni P, et al. Examining the measurement equivalence of the Maslach Burnout Inventory across age, gender, and specialty groups in US physicians. J Patient-Reported Outcomes. 2021;5.

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Specialty Data Report—Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.aamc .org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-sex -specialty-2021

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Physician Specialty Data Report—ACGME Residents and Fellows by Sex and Specialty, 2021. Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www .aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/acgme-residents -fellows-sex-and-specialty-2021

- Painter LM, Biggans KA, Turner CT. Risk managementobstetrics and gynecology perspective. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2023;66:331-341. DOI:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000775

- Darney BG, Boniface E, Liberty A. Assessing the effect of abortion restrictions. Obstetr Gynecol. 2023;141:233-235.

- Heuerman AC, Bessett D, Antommaria AHM, et al. Experiences of reproductive genetic counselors with abortion regulations in Ohio. J Genet Counseling. 2022;31:641-652.

- Brandi K, Gill P. Abortion restrictions threaten all reproductive health care clinicians. Am J Public Health. 2023;113:384-385.

- Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320:1131-1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1277

- Williamson K, Lank PM, Cheema N, et al. Comparing the Maslach Burnout Inventory to other well-being instruments in emergency medicine residents. J Graduate Med Education. 2018;532-536. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4300 /JGME-D-18-00155.1

- Brady KJS, Sheldrick RC, Ni P, et al. Establishing crosswalks between common measures of burnout in US physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:777-784.

- Zhang X, Song Y, Jiang T, et al. Interventions to reduce burnout of physicians and nurses: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;26:e20992. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020992

- Scheepers RA, Emke H, Ronald M, et al. The impact of mindfulness-based interventions on doctors’ well-being and performance: a systematic review. Med Education. 2020;54:138-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14020

- Olson K, Marchalik D, Farley H, et al. Organizational strategies to reduce physician burnout and improve professional fulfillment. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2019;49:12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.100664

- Berry LL, Awdish RLA, Swensen SJ. 5 ways to restore depleted health care workers. Harvard Business Rev. February 11, 2022.

- Sullivan AB, Hersh CM, Rensel M, et al. Leadership inequity, burnout, and lower engagement of women in medicine. J Health Serv Psychol. 2023;49:33-39.

- Hoffman S. Healing the healers: legal remedies for physician burnout. Yale J Health Policy Law Ethics. 2018;18:56-113.

- Federation of State Medical Boards. Physician wellness and burnout: report and recommendations of the workgroup on physician wellness and burnout. (Policy adopted by FSMB). April 2018. Accessed July 21, 2023. https://www.fsmb.org /siteassets/advocacy/policies/policy-on-wellness-and -burnout.pdf

- Robinson C, Kettering C, Sanfilippo JS. Medical malpractice lawsuits. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2023;66:256-260. DOI: https ://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0000000000000777

- Gittler GJ, Goldstein EJ. The elements of medical malpractice: an overview. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1152-1155.