User login

Hand‐Carried Ultrasound Use

Ultrasound, one of the most reliable diagnostic technologies in medicine, has a unique long‐term safety profile across a wide spectrum of applications. In line with the trend toward the miniaturization of many other technologies, increasingly sophisticated hand‐held or hand‐carried ultrasound (HCU) devices have become widely available. To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 10 new‐generation portable (1.0‐4.5 kg) ultrasound devices, and a recent industry report projected that the HCU market will see revenues in excess of $1 billion by 2011.1

Although cardiovascular assessment remains its primary use, hospitalist physicians are increasingly turning to this technology for the localization of fluid and other abnormalities prior to paracentesis and thoracentesis. While there are other potential uses (eg, managing acute scrotal pain, diagnosing meniscal tears, measuring carotid intimal thickness), the higher‐quality studies of hospitalist‐physicians' use of HCU have focused on cardiovascular assessment. HCU confers a number of potential workflow‐related advantages, including coordinated point‐of‐care evaluation at short notice when formal ultrasound may be unavailable, as well as circumvention of the need to call on radiology or cardiology specialists.2 Even for experienced cardiologists, heart failure can be difficult to identify using any modality, and the clinical diagnosis of cardiovascular disease by hospital physicians has been documented as poor.3, 4 Thus, the addition of HCU to the palette of diagnostic and teaching tools available to frontline physicians potentially offers improvements over stethoscope‐assisted physical examination alone (including visual inspection, palpation, and auscultation), which has remained essentially unaltered for 150 years.57

Evidence Base for HCU Use by Hospitalists

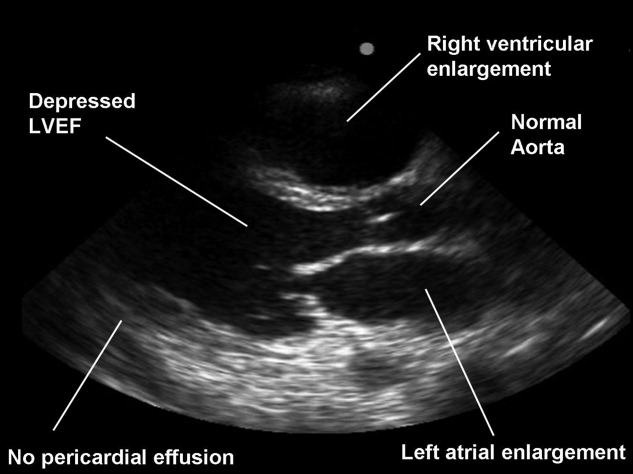

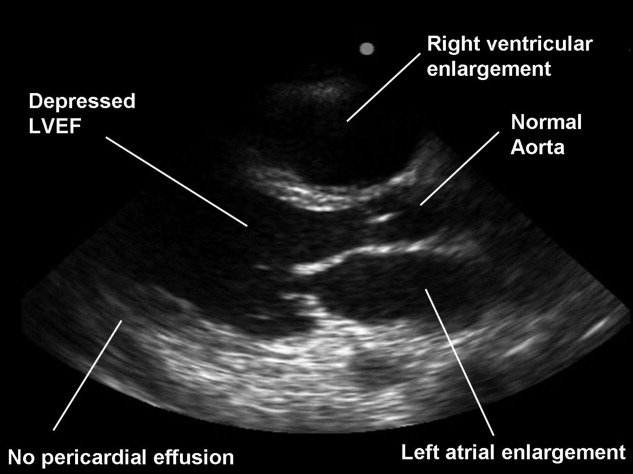

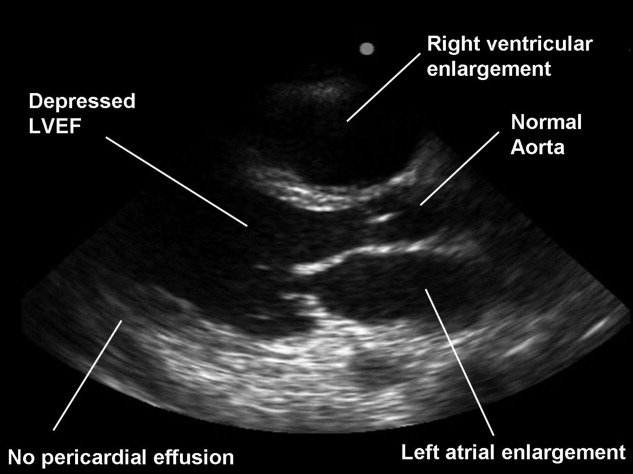

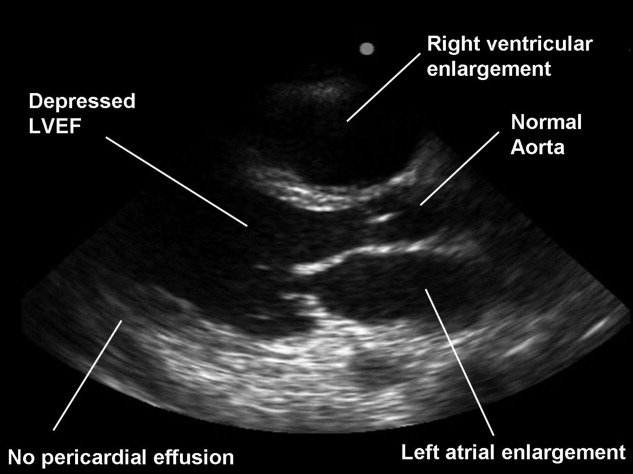

The few primary studies on HCU use by hospitalists have focused on the potential utility of this technology as a valuable adjunct to the physical exam for the detection of cardiovascular disease (eg, asymptomatic left ventricular [LV] dysfunction, cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion) in the ambulatory or acute care setting.8, 9 Operation of HCU by hospitalists is not clearly indicated for the evaluation of valvular disease (eg, aortic and mitral regurgitation), in part due to the limited Doppler capabilities of the smaller devices.911 The risk of a gradual erosion of physical exam skills accompanying expansion of HCU use by hospitalists could itself become a potential disadvantage of a premature replacement of the stethoscope, since the results obtained by hospitalists performing a standard physical exam have been shown to be better than those obtained with HCU.8, 9

The lack of large, multicenter studies of HCU use by hospitalists leaves many questions unanswered, including whether or not the relatively low initial cost of an HCU device ($9,000‐$50,000) vs. that of a full‐sized hospital ultrasound system ($250,000) will eventually translate into overall cost‐effectiveness or actual patient‐centered benefit.10 While cautious advocates have insisted that HCU provides additive information in conjunction with the physical exam, this approach is not meant to serve as a substitute for standard echocardiography in patients requiring full evaluation in inpatient settings relevant for hospitalists.1114 Referral for additional testing or specialist opinionsand the associated costs incurredcannot necessarily be circumvented by hospitalist‐operated HCU.

A major problem with the HCU literature in general is its lack of standardization betweenand withinstudies, which renders it nearly impossible to generalize findings about important clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, quality‐of‐life, symptoms, physical functioning, and morbidity and mortality. There are a preponderance of underpowered, methodologically inconsistent, single‐center case series that do not evaluate diagnostic accuracy in terms of patient outcomes. For example, although one study did find a modest (22‐29%) reduction in department workload with HCU, the authors omitted important information regarding blinding, and no power calculations were reported; thus, it was not possible to ascertain whether or not the reported results were due to the intervention or to chance.15 There clearly remains a need to convincingly demonstrate that patient care, shortening of length of stay, long‐term prognosis, or potential financial savings could occur with use of these devices by hospitalists.5 The process of device acquisition and resource allocation is, at least in part, based on accumulated evidence from studies that have ill‐defined relevant outcomes (eg, left ventricular function). However, even if such outcomes were to be more closely examined, medical decision‐making would still suffer from discrepant findings due to numerous differences in study design, including parameters involving patient population and selection, setting (eg, echocardiography laboratory vs. critical care unit), provider background, and specific device(s) used.

Training Issues

Hospitalist proficiency across HCU imaging skills (ie, acquisition, measurement, interpretation) has been found to be inconsistent.9 Endorsement and expansion of hospitalist use of HCU may to some extent reflect an overgeneralization from disparate comparative studies showing moderate success obtained with HCU (vs. physical exam) by other practitioner groups such as medical students and fellows with limited experience.16, 17 Whereas in 2005, Hellmann et al.18 concluded that medical residents with minimal training can learn to perform some of the basic functions of HCU with reasonable accuracy, Martin et al.8, 9 (in 2007 and 2009) reported conflicting results from a study of hospitalists trained at the same institution.

Concern about switching from standard to nonstandard HCU operators is raised by studies in which specialized operators (eg, echocardiography technicians) obtained better results than hospitalists using these devices.8, 9 In 2004, Borges et al.19 reported the results of 315 patients referred to specialists at a cardiology clinic for preoperative assessment prior to noncardiac surgery; the results (94.8% and 96.7% agreement with standard echocardiography on the main echocardiographic finding and detection of valve disease, respectively) were attributed to the fact that experienced cardiologists were working under ideal conditions using only the most advanced HCU devices with Doppler as well as harmonic imaging capabilities. Likewise, in 2004, Tsutsui et al.20 studied 44 consecutive hospitalized patients who underwent comprehensive echocardiography and bedside HCU. They reported that hemodynamic assessment by HCU was poor, even when performed by practitioners with relatively high levels of training.20 In 2003, DeCara et al.12 performed standard echocardiography on 300 adult inpatients referred for imaging, and concluded that standardized training, competency testing, and quality assurance guidelines need to be established before these devices can be utilized for clinical decision‐making by physicians without formal training in echocardiography. Although there have been numerous calls for training guidelines, it has not yet been determined how much training would be optimalor even necessaryfor professionals of each subspecialty to achieve levels of accuracy that are acceptable. Furthermore, it is well known that skill level declines unless a technique is regularly reinforced with practice, and therefore, recertification or procedure volume standards should be established.

The issue of potential harm needs to be raised, if hospitalists with access to HCU are indeed less accurate in their diagnoses than trained cardiologists interpreting images acquired by an established alternative such as echocardiography. False negatives can lead to delayed treatment, and false positives to unwarranted treatment. Given that the treatment effects of HCU use by hospitalists have not been closely scrutinized, the expansion of such use appears unwarranted, at least until further randomized studies with well‐defined outcomes have been conducted. Although the HCU devices themselves have a good safety profile, their potential benefits and harms (eg, possibility of increased nosocomial infection) will ultimately reflect operator skill and their impact on patient management relative to the gold‐standard diagnostic modalities for which there is abundant evidence of safety and efficacy.21

Premarketing and Postmarketing Concerns

The controversy regarding hospitalist use of HCU exposes gaps in the FDA approval process for medical devices, which are subjected to much less rigorous scrutiny during the premarketing approval process than pharmaceuticals.22 Moreover, the aggressive marketing of newly approved devices (and drugs) can drive medically unwarranted overuse, or indication creep, which justifies calls for the establishment of rigorous standards of clinical relevance and practice.23, 24 While the available literature on HCU operation by hospitalists is focused on cardiovascular indications for the technology, hospital medicine physicians are increasingly using HCU to guide paracentesis and thoracentesis. Given how commonplace the expansion of such practices has become, it is noteworthy that HCU operation by hospitalists has not yet been evaluated and endorsed in larger, controlled trials demonstrating appropriate outcomes.25

Across all fields of medicine, the transition from traditional to newer modalities remains a slippery slope in terms of demonstration of persuasive evidence of patient‐centered benefit.26 Fascination with emerging technologies (so‐called gizmo idolatry) and increased reimbursement potential threaten to distract patients and their providers from legitimate concerns about how medical device manufacturers and for‐profit corporations increasingly influence device acquisition and clinical practice.2731 While we lack strong evidence demonstrating that diagnostic tests such as HCU are beneficial when performed by hospitalists, the expanded use of these handy new devices by hospitalists is simultaneously generating increased incidental and equivocal findings, which in turn render it necessary to go back and perform secondary verification studies by specialists using older, gold‐standard modalities. This vicious cycle, coupled with the current lack of evidence, will continue to degrade confidence in the initiation of either acute or chronic treatment on the basis of HCU results obtained by hospitalist physicians.

Eventually, the increased use of HCU by hospitalists might lead to demonstrations of improved hospital workflow management, but it may just as easily represent another new coupling of technology and practitioner that prematurely becomes the standard of care in the absence of any demonstration of added value. The initially enthusiastic application of pulmonary artery catheters (PACs) serves as a cautionary tale in which the acquisition of additional clinical data did not necessarily lead to improved clinical outcomes: whereas PACs did enhance the clinical understanding of hemodynamics, they were not associated with an overall advantage in terms of mortality, length of hospital stay, or cost.3235 Ultimately, more information is not necessarily better information. Although new medical technologies can produce extremely useful diagnostic results that aid in the management of critically ill patients, poor data interpretation resulting from lack of targeted training and experience can nullify point‐of‐care advantages, and perhaps lead to excess morbidity and mortality.14 In clinical practice, it is generally best to avoid reliance on assumptions of added value in lieu of demonstrations of the same.

Conclusions

Hospital practitioners should not yet put away their stethoscopes. New technologies such as HCU need to be embraced in parallel with accumulating evidence of benefit. In the hands of hospitalists, the smaller HCU devices may very well prove handy, but at present, the literature simply does not support the use of HCU by hospitalist physicians.

- Hand‐Carried Ultrasound—Reshaping the ultrasound marketplace. Available at: http://www.sonoworld.com/NewsStories/NewsStories.aspx?ID= 450. Accessed August2009.

- ,,.A new narrative for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2009;4(4):207–208.

- .Can heart failure be diagnosed in primary care?BMJ.2000;321(7255):188–189.

- ,,.Evidence of inadequate investigation and treatment of patients with heart failure.Br Heart J.1994;71(6):584–587.

- .Utility of hand‐carried ultrasound for consultative cardiology.Echocardiography.2003;20(5):463–469.

- .Tomorrow's stethoscope: the hand‐held ultrasound device?J S C Med Assoc.2006;102(10):345.

- ,,.The hand‐carried echocardiographic device as an aid to the physical examination.Echocardiography.2003;20(5):477–485.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalist performance of cardiac hand‐carried ultrasound after focused training.Am J Med.2007;120(11):1000–1004.

- ,,, et al.Hand‐carried ultrasound performed by hospitalists: does it improve the cardiac physical examination?Am J Med.2009;122(1):35–41.

- ,,.Should a hand‐carried ultrasound machine become standard equipment for every internist?Am J Med.2009;122(1):1–3.

- ,,,.How useful is hand‐carried bedside echocardiography in critically ill patients?J Am Coll Cardiol.2001;37(8):2019–2022.

- ,,,,,.The use of small personal ultrasound devices by internists without formal training in echocardiography.Eur J Echocardiogr.2003;4(2):141–147.

- ,,.Can hand‐carried ultrasound devices be extended for use by the noncardiology medical community?Echocardiography.2003;20(5):471–476.

- .Specific skill set and goals of focused echocardiography for critical care clinicians.Crit Care Med.2007;35(5 suppl):S144–S149.

- ,,, et al.The use of hand‐carried ultrasound in the hospital setting—a cost‐effective analysis.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2005;18(6):620–625.

- ,,, et al.A comparison by medicine residents of physical examination versus hand‐carried ultrasound for estimation of right atrial pressure.Am J Cardiol.2007;99(11):1614–1616.

- ,,, et al.Radial artery pulse pressure variation correlates with brachial artery peak velocity variation in ventilated subjects when measured by internal medicine residents using hand‐carried ultrasound devices.Chest.2007;131(5):1301–1307.

- ,,,,,.The rate at which residents learn to use hand‐held echocardiography at the bedside.Am J Med.2005;118(9):1010–1018.

- ,,,,.Diagnostic accuracy of new handheld echocardiography with Doppler and harmonic imaging properties.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2004;17(3):234–238.

- ,,,,,.Hand‐carried ultrasound performed at bedside in cardiology inpatient setting ‐ a comparative study with comprehensive echocardiography.Cardiovasc Ultrasound.2004;2:24.

- ,,Sade LE. Influence of hand‐carried ultrasound on bedside patient treatment decisions for consultative cardiology.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2004;17(1):50–55.

- ,,,.Who is responsible for evaluating the safety and effectiveness of medical devices? The role of independent technology assessment.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(suppl 1):57–63.

- ,,.Newly approved does not always mean new and improved.JAMA.2008;299(13):1598–1600.

- ,.Indication creep: physician beware.CMAJ.2007;177(7):697,699.

- ,,,.Ultrasound‐guided interventional radiology in critical care.Crit Care Med.2007;35(5 suppl):S186–S197.

- ,.Pay now, benefits may follow—the case of cardiac computed tomographic angiography.N Engl J Med.2008;359(22):2309–2311.

- ,.Gizmo idolatry.JAMA.2008;299(15):1830–1832.

- .Just because you can, doesn't mean that you should: a call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):398–402.

- ,.Impugning the integrity of medical science: the adverse effects of industry influence.JAMA.2008;299(15):1833–1835.

- ,,, et al.The 2007 ABJS Marshall Urist Award: the impact of direct‐to‐consumer advertising in orthopaedics.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2007;458:202–219.

- ,.Direct to consumer advertising in healthcare: history, benefits, and concerns.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2007;457:96–104.

- Connors,,, et al.The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators.JAMA.1996;276(11):889–897.

- ,,, et al.Assessment of the clinical effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in management of patients in intensive care (PAC‐Man): a randomised controlled trial.Lancet.2005;366(9484):472–477.

- ,,, et al.Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial.JAMA.2005;294(13):1625–1633.

- ,,, et al.Early use of the pulmonary artery catheter and outcomes in patients with shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial.JAMA.2003;290(20):2713–2720.

Ultrasound, one of the most reliable diagnostic technologies in medicine, has a unique long‐term safety profile across a wide spectrum of applications. In line with the trend toward the miniaturization of many other technologies, increasingly sophisticated hand‐held or hand‐carried ultrasound (HCU) devices have become widely available. To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 10 new‐generation portable (1.0‐4.5 kg) ultrasound devices, and a recent industry report projected that the HCU market will see revenues in excess of $1 billion by 2011.1

Although cardiovascular assessment remains its primary use, hospitalist physicians are increasingly turning to this technology for the localization of fluid and other abnormalities prior to paracentesis and thoracentesis. While there are other potential uses (eg, managing acute scrotal pain, diagnosing meniscal tears, measuring carotid intimal thickness), the higher‐quality studies of hospitalist‐physicians' use of HCU have focused on cardiovascular assessment. HCU confers a number of potential workflow‐related advantages, including coordinated point‐of‐care evaluation at short notice when formal ultrasound may be unavailable, as well as circumvention of the need to call on radiology or cardiology specialists.2 Even for experienced cardiologists, heart failure can be difficult to identify using any modality, and the clinical diagnosis of cardiovascular disease by hospital physicians has been documented as poor.3, 4 Thus, the addition of HCU to the palette of diagnostic and teaching tools available to frontline physicians potentially offers improvements over stethoscope‐assisted physical examination alone (including visual inspection, palpation, and auscultation), which has remained essentially unaltered for 150 years.57

Evidence Base for HCU Use by Hospitalists

The few primary studies on HCU use by hospitalists have focused on the potential utility of this technology as a valuable adjunct to the physical exam for the detection of cardiovascular disease (eg, asymptomatic left ventricular [LV] dysfunction, cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion) in the ambulatory or acute care setting.8, 9 Operation of HCU by hospitalists is not clearly indicated for the evaluation of valvular disease (eg, aortic and mitral regurgitation), in part due to the limited Doppler capabilities of the smaller devices.911 The risk of a gradual erosion of physical exam skills accompanying expansion of HCU use by hospitalists could itself become a potential disadvantage of a premature replacement of the stethoscope, since the results obtained by hospitalists performing a standard physical exam have been shown to be better than those obtained with HCU.8, 9

The lack of large, multicenter studies of HCU use by hospitalists leaves many questions unanswered, including whether or not the relatively low initial cost of an HCU device ($9,000‐$50,000) vs. that of a full‐sized hospital ultrasound system ($250,000) will eventually translate into overall cost‐effectiveness or actual patient‐centered benefit.10 While cautious advocates have insisted that HCU provides additive information in conjunction with the physical exam, this approach is not meant to serve as a substitute for standard echocardiography in patients requiring full evaluation in inpatient settings relevant for hospitalists.1114 Referral for additional testing or specialist opinionsand the associated costs incurredcannot necessarily be circumvented by hospitalist‐operated HCU.

A major problem with the HCU literature in general is its lack of standardization betweenand withinstudies, which renders it nearly impossible to generalize findings about important clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, quality‐of‐life, symptoms, physical functioning, and morbidity and mortality. There are a preponderance of underpowered, methodologically inconsistent, single‐center case series that do not evaluate diagnostic accuracy in terms of patient outcomes. For example, although one study did find a modest (22‐29%) reduction in department workload with HCU, the authors omitted important information regarding blinding, and no power calculations were reported; thus, it was not possible to ascertain whether or not the reported results were due to the intervention or to chance.15 There clearly remains a need to convincingly demonstrate that patient care, shortening of length of stay, long‐term prognosis, or potential financial savings could occur with use of these devices by hospitalists.5 The process of device acquisition and resource allocation is, at least in part, based on accumulated evidence from studies that have ill‐defined relevant outcomes (eg, left ventricular function). However, even if such outcomes were to be more closely examined, medical decision‐making would still suffer from discrepant findings due to numerous differences in study design, including parameters involving patient population and selection, setting (eg, echocardiography laboratory vs. critical care unit), provider background, and specific device(s) used.

Training Issues

Hospitalist proficiency across HCU imaging skills (ie, acquisition, measurement, interpretation) has been found to be inconsistent.9 Endorsement and expansion of hospitalist use of HCU may to some extent reflect an overgeneralization from disparate comparative studies showing moderate success obtained with HCU (vs. physical exam) by other practitioner groups such as medical students and fellows with limited experience.16, 17 Whereas in 2005, Hellmann et al.18 concluded that medical residents with minimal training can learn to perform some of the basic functions of HCU with reasonable accuracy, Martin et al.8, 9 (in 2007 and 2009) reported conflicting results from a study of hospitalists trained at the same institution.

Concern about switching from standard to nonstandard HCU operators is raised by studies in which specialized operators (eg, echocardiography technicians) obtained better results than hospitalists using these devices.8, 9 In 2004, Borges et al.19 reported the results of 315 patients referred to specialists at a cardiology clinic for preoperative assessment prior to noncardiac surgery; the results (94.8% and 96.7% agreement with standard echocardiography on the main echocardiographic finding and detection of valve disease, respectively) were attributed to the fact that experienced cardiologists were working under ideal conditions using only the most advanced HCU devices with Doppler as well as harmonic imaging capabilities. Likewise, in 2004, Tsutsui et al.20 studied 44 consecutive hospitalized patients who underwent comprehensive echocardiography and bedside HCU. They reported that hemodynamic assessment by HCU was poor, even when performed by practitioners with relatively high levels of training.20 In 2003, DeCara et al.12 performed standard echocardiography on 300 adult inpatients referred for imaging, and concluded that standardized training, competency testing, and quality assurance guidelines need to be established before these devices can be utilized for clinical decision‐making by physicians without formal training in echocardiography. Although there have been numerous calls for training guidelines, it has not yet been determined how much training would be optimalor even necessaryfor professionals of each subspecialty to achieve levels of accuracy that are acceptable. Furthermore, it is well known that skill level declines unless a technique is regularly reinforced with practice, and therefore, recertification or procedure volume standards should be established.

The issue of potential harm needs to be raised, if hospitalists with access to HCU are indeed less accurate in their diagnoses than trained cardiologists interpreting images acquired by an established alternative such as echocardiography. False negatives can lead to delayed treatment, and false positives to unwarranted treatment. Given that the treatment effects of HCU use by hospitalists have not been closely scrutinized, the expansion of such use appears unwarranted, at least until further randomized studies with well‐defined outcomes have been conducted. Although the HCU devices themselves have a good safety profile, their potential benefits and harms (eg, possibility of increased nosocomial infection) will ultimately reflect operator skill and their impact on patient management relative to the gold‐standard diagnostic modalities for which there is abundant evidence of safety and efficacy.21

Premarketing and Postmarketing Concerns

The controversy regarding hospitalist use of HCU exposes gaps in the FDA approval process for medical devices, which are subjected to much less rigorous scrutiny during the premarketing approval process than pharmaceuticals.22 Moreover, the aggressive marketing of newly approved devices (and drugs) can drive medically unwarranted overuse, or indication creep, which justifies calls for the establishment of rigorous standards of clinical relevance and practice.23, 24 While the available literature on HCU operation by hospitalists is focused on cardiovascular indications for the technology, hospital medicine physicians are increasingly using HCU to guide paracentesis and thoracentesis. Given how commonplace the expansion of such practices has become, it is noteworthy that HCU operation by hospitalists has not yet been evaluated and endorsed in larger, controlled trials demonstrating appropriate outcomes.25

Across all fields of medicine, the transition from traditional to newer modalities remains a slippery slope in terms of demonstration of persuasive evidence of patient‐centered benefit.26 Fascination with emerging technologies (so‐called gizmo idolatry) and increased reimbursement potential threaten to distract patients and their providers from legitimate concerns about how medical device manufacturers and for‐profit corporations increasingly influence device acquisition and clinical practice.2731 While we lack strong evidence demonstrating that diagnostic tests such as HCU are beneficial when performed by hospitalists, the expanded use of these handy new devices by hospitalists is simultaneously generating increased incidental and equivocal findings, which in turn render it necessary to go back and perform secondary verification studies by specialists using older, gold‐standard modalities. This vicious cycle, coupled with the current lack of evidence, will continue to degrade confidence in the initiation of either acute or chronic treatment on the basis of HCU results obtained by hospitalist physicians.

Eventually, the increased use of HCU by hospitalists might lead to demonstrations of improved hospital workflow management, but it may just as easily represent another new coupling of technology and practitioner that prematurely becomes the standard of care in the absence of any demonstration of added value. The initially enthusiastic application of pulmonary artery catheters (PACs) serves as a cautionary tale in which the acquisition of additional clinical data did not necessarily lead to improved clinical outcomes: whereas PACs did enhance the clinical understanding of hemodynamics, they were not associated with an overall advantage in terms of mortality, length of hospital stay, or cost.3235 Ultimately, more information is not necessarily better information. Although new medical technologies can produce extremely useful diagnostic results that aid in the management of critically ill patients, poor data interpretation resulting from lack of targeted training and experience can nullify point‐of‐care advantages, and perhaps lead to excess morbidity and mortality.14 In clinical practice, it is generally best to avoid reliance on assumptions of added value in lieu of demonstrations of the same.

Conclusions

Hospital practitioners should not yet put away their stethoscopes. New technologies such as HCU need to be embraced in parallel with accumulating evidence of benefit. In the hands of hospitalists, the smaller HCU devices may very well prove handy, but at present, the literature simply does not support the use of HCU by hospitalist physicians.

Ultrasound, one of the most reliable diagnostic technologies in medicine, has a unique long‐term safety profile across a wide spectrum of applications. In line with the trend toward the miniaturization of many other technologies, increasingly sophisticated hand‐held or hand‐carried ultrasound (HCU) devices have become widely available. To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved more than 10 new‐generation portable (1.0‐4.5 kg) ultrasound devices, and a recent industry report projected that the HCU market will see revenues in excess of $1 billion by 2011.1

Although cardiovascular assessment remains its primary use, hospitalist physicians are increasingly turning to this technology for the localization of fluid and other abnormalities prior to paracentesis and thoracentesis. While there are other potential uses (eg, managing acute scrotal pain, diagnosing meniscal tears, measuring carotid intimal thickness), the higher‐quality studies of hospitalist‐physicians' use of HCU have focused on cardiovascular assessment. HCU confers a number of potential workflow‐related advantages, including coordinated point‐of‐care evaluation at short notice when formal ultrasound may be unavailable, as well as circumvention of the need to call on radiology or cardiology specialists.2 Even for experienced cardiologists, heart failure can be difficult to identify using any modality, and the clinical diagnosis of cardiovascular disease by hospital physicians has been documented as poor.3, 4 Thus, the addition of HCU to the palette of diagnostic and teaching tools available to frontline physicians potentially offers improvements over stethoscope‐assisted physical examination alone (including visual inspection, palpation, and auscultation), which has remained essentially unaltered for 150 years.57

Evidence Base for HCU Use by Hospitalists

The few primary studies on HCU use by hospitalists have focused on the potential utility of this technology as a valuable adjunct to the physical exam for the detection of cardiovascular disease (eg, asymptomatic left ventricular [LV] dysfunction, cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion) in the ambulatory or acute care setting.8, 9 Operation of HCU by hospitalists is not clearly indicated for the evaluation of valvular disease (eg, aortic and mitral regurgitation), in part due to the limited Doppler capabilities of the smaller devices.911 The risk of a gradual erosion of physical exam skills accompanying expansion of HCU use by hospitalists could itself become a potential disadvantage of a premature replacement of the stethoscope, since the results obtained by hospitalists performing a standard physical exam have been shown to be better than those obtained with HCU.8, 9

The lack of large, multicenter studies of HCU use by hospitalists leaves many questions unanswered, including whether or not the relatively low initial cost of an HCU device ($9,000‐$50,000) vs. that of a full‐sized hospital ultrasound system ($250,000) will eventually translate into overall cost‐effectiveness or actual patient‐centered benefit.10 While cautious advocates have insisted that HCU provides additive information in conjunction with the physical exam, this approach is not meant to serve as a substitute for standard echocardiography in patients requiring full evaluation in inpatient settings relevant for hospitalists.1114 Referral for additional testing or specialist opinionsand the associated costs incurredcannot necessarily be circumvented by hospitalist‐operated HCU.

A major problem with the HCU literature in general is its lack of standardization betweenand withinstudies, which renders it nearly impossible to generalize findings about important clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, quality‐of‐life, symptoms, physical functioning, and morbidity and mortality. There are a preponderance of underpowered, methodologically inconsistent, single‐center case series that do not evaluate diagnostic accuracy in terms of patient outcomes. For example, although one study did find a modest (22‐29%) reduction in department workload with HCU, the authors omitted important information regarding blinding, and no power calculations were reported; thus, it was not possible to ascertain whether or not the reported results were due to the intervention or to chance.15 There clearly remains a need to convincingly demonstrate that patient care, shortening of length of stay, long‐term prognosis, or potential financial savings could occur with use of these devices by hospitalists.5 The process of device acquisition and resource allocation is, at least in part, based on accumulated evidence from studies that have ill‐defined relevant outcomes (eg, left ventricular function). However, even if such outcomes were to be more closely examined, medical decision‐making would still suffer from discrepant findings due to numerous differences in study design, including parameters involving patient population and selection, setting (eg, echocardiography laboratory vs. critical care unit), provider background, and specific device(s) used.

Training Issues

Hospitalist proficiency across HCU imaging skills (ie, acquisition, measurement, interpretation) has been found to be inconsistent.9 Endorsement and expansion of hospitalist use of HCU may to some extent reflect an overgeneralization from disparate comparative studies showing moderate success obtained with HCU (vs. physical exam) by other practitioner groups such as medical students and fellows with limited experience.16, 17 Whereas in 2005, Hellmann et al.18 concluded that medical residents with minimal training can learn to perform some of the basic functions of HCU with reasonable accuracy, Martin et al.8, 9 (in 2007 and 2009) reported conflicting results from a study of hospitalists trained at the same institution.

Concern about switching from standard to nonstandard HCU operators is raised by studies in which specialized operators (eg, echocardiography technicians) obtained better results than hospitalists using these devices.8, 9 In 2004, Borges et al.19 reported the results of 315 patients referred to specialists at a cardiology clinic for preoperative assessment prior to noncardiac surgery; the results (94.8% and 96.7% agreement with standard echocardiography on the main echocardiographic finding and detection of valve disease, respectively) were attributed to the fact that experienced cardiologists were working under ideal conditions using only the most advanced HCU devices with Doppler as well as harmonic imaging capabilities. Likewise, in 2004, Tsutsui et al.20 studied 44 consecutive hospitalized patients who underwent comprehensive echocardiography and bedside HCU. They reported that hemodynamic assessment by HCU was poor, even when performed by practitioners with relatively high levels of training.20 In 2003, DeCara et al.12 performed standard echocardiography on 300 adult inpatients referred for imaging, and concluded that standardized training, competency testing, and quality assurance guidelines need to be established before these devices can be utilized for clinical decision‐making by physicians without formal training in echocardiography. Although there have been numerous calls for training guidelines, it has not yet been determined how much training would be optimalor even necessaryfor professionals of each subspecialty to achieve levels of accuracy that are acceptable. Furthermore, it is well known that skill level declines unless a technique is regularly reinforced with practice, and therefore, recertification or procedure volume standards should be established.

The issue of potential harm needs to be raised, if hospitalists with access to HCU are indeed less accurate in their diagnoses than trained cardiologists interpreting images acquired by an established alternative such as echocardiography. False negatives can lead to delayed treatment, and false positives to unwarranted treatment. Given that the treatment effects of HCU use by hospitalists have not been closely scrutinized, the expansion of such use appears unwarranted, at least until further randomized studies with well‐defined outcomes have been conducted. Although the HCU devices themselves have a good safety profile, their potential benefits and harms (eg, possibility of increased nosocomial infection) will ultimately reflect operator skill and their impact on patient management relative to the gold‐standard diagnostic modalities for which there is abundant evidence of safety and efficacy.21

Premarketing and Postmarketing Concerns

The controversy regarding hospitalist use of HCU exposes gaps in the FDA approval process for medical devices, which are subjected to much less rigorous scrutiny during the premarketing approval process than pharmaceuticals.22 Moreover, the aggressive marketing of newly approved devices (and drugs) can drive medically unwarranted overuse, or indication creep, which justifies calls for the establishment of rigorous standards of clinical relevance and practice.23, 24 While the available literature on HCU operation by hospitalists is focused on cardiovascular indications for the technology, hospital medicine physicians are increasingly using HCU to guide paracentesis and thoracentesis. Given how commonplace the expansion of such practices has become, it is noteworthy that HCU operation by hospitalists has not yet been evaluated and endorsed in larger, controlled trials demonstrating appropriate outcomes.25

Across all fields of medicine, the transition from traditional to newer modalities remains a slippery slope in terms of demonstration of persuasive evidence of patient‐centered benefit.26 Fascination with emerging technologies (so‐called gizmo idolatry) and increased reimbursement potential threaten to distract patients and their providers from legitimate concerns about how medical device manufacturers and for‐profit corporations increasingly influence device acquisition and clinical practice.2731 While we lack strong evidence demonstrating that diagnostic tests such as HCU are beneficial when performed by hospitalists, the expanded use of these handy new devices by hospitalists is simultaneously generating increased incidental and equivocal findings, which in turn render it necessary to go back and perform secondary verification studies by specialists using older, gold‐standard modalities. This vicious cycle, coupled with the current lack of evidence, will continue to degrade confidence in the initiation of either acute or chronic treatment on the basis of HCU results obtained by hospitalist physicians.

Eventually, the increased use of HCU by hospitalists might lead to demonstrations of improved hospital workflow management, but it may just as easily represent another new coupling of technology and practitioner that prematurely becomes the standard of care in the absence of any demonstration of added value. The initially enthusiastic application of pulmonary artery catheters (PACs) serves as a cautionary tale in which the acquisition of additional clinical data did not necessarily lead to improved clinical outcomes: whereas PACs did enhance the clinical understanding of hemodynamics, they were not associated with an overall advantage in terms of mortality, length of hospital stay, or cost.3235 Ultimately, more information is not necessarily better information. Although new medical technologies can produce extremely useful diagnostic results that aid in the management of critically ill patients, poor data interpretation resulting from lack of targeted training and experience can nullify point‐of‐care advantages, and perhaps lead to excess morbidity and mortality.14 In clinical practice, it is generally best to avoid reliance on assumptions of added value in lieu of demonstrations of the same.

Conclusions

Hospital practitioners should not yet put away their stethoscopes. New technologies such as HCU need to be embraced in parallel with accumulating evidence of benefit. In the hands of hospitalists, the smaller HCU devices may very well prove handy, but at present, the literature simply does not support the use of HCU by hospitalist physicians.

- Hand‐Carried Ultrasound—Reshaping the ultrasound marketplace. Available at: http://www.sonoworld.com/NewsStories/NewsStories.aspx?ID= 450. Accessed August2009.

- ,,.A new narrative for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2009;4(4):207–208.

- .Can heart failure be diagnosed in primary care?BMJ.2000;321(7255):188–189.

- ,,.Evidence of inadequate investigation and treatment of patients with heart failure.Br Heart J.1994;71(6):584–587.

- .Utility of hand‐carried ultrasound for consultative cardiology.Echocardiography.2003;20(5):463–469.

- .Tomorrow's stethoscope: the hand‐held ultrasound device?J S C Med Assoc.2006;102(10):345.

- ,,.The hand‐carried echocardiographic device as an aid to the physical examination.Echocardiography.2003;20(5):477–485.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalist performance of cardiac hand‐carried ultrasound after focused training.Am J Med.2007;120(11):1000–1004.

- ,,, et al.Hand‐carried ultrasound performed by hospitalists: does it improve the cardiac physical examination?Am J Med.2009;122(1):35–41.

- ,,.Should a hand‐carried ultrasound machine become standard equipment for every internist?Am J Med.2009;122(1):1–3.

- ,,,.How useful is hand‐carried bedside echocardiography in critically ill patients?J Am Coll Cardiol.2001;37(8):2019–2022.

- ,,,,,.The use of small personal ultrasound devices by internists without formal training in echocardiography.Eur J Echocardiogr.2003;4(2):141–147.

- ,,.Can hand‐carried ultrasound devices be extended for use by the noncardiology medical community?Echocardiography.2003;20(5):471–476.

- .Specific skill set and goals of focused echocardiography for critical care clinicians.Crit Care Med.2007;35(5 suppl):S144–S149.

- ,,, et al.The use of hand‐carried ultrasound in the hospital setting—a cost‐effective analysis.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2005;18(6):620–625.

- ,,, et al.A comparison by medicine residents of physical examination versus hand‐carried ultrasound for estimation of right atrial pressure.Am J Cardiol.2007;99(11):1614–1616.

- ,,, et al.Radial artery pulse pressure variation correlates with brachial artery peak velocity variation in ventilated subjects when measured by internal medicine residents using hand‐carried ultrasound devices.Chest.2007;131(5):1301–1307.

- ,,,,,.The rate at which residents learn to use hand‐held echocardiography at the bedside.Am J Med.2005;118(9):1010–1018.

- ,,,,.Diagnostic accuracy of new handheld echocardiography with Doppler and harmonic imaging properties.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2004;17(3):234–238.

- ,,,,,.Hand‐carried ultrasound performed at bedside in cardiology inpatient setting ‐ a comparative study with comprehensive echocardiography.Cardiovasc Ultrasound.2004;2:24.

- ,,Sade LE. Influence of hand‐carried ultrasound on bedside patient treatment decisions for consultative cardiology.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2004;17(1):50–55.

- ,,,.Who is responsible for evaluating the safety and effectiveness of medical devices? The role of independent technology assessment.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(suppl 1):57–63.

- ,,.Newly approved does not always mean new and improved.JAMA.2008;299(13):1598–1600.

- ,.Indication creep: physician beware.CMAJ.2007;177(7):697,699.

- ,,,.Ultrasound‐guided interventional radiology in critical care.Crit Care Med.2007;35(5 suppl):S186–S197.

- ,.Pay now, benefits may follow—the case of cardiac computed tomographic angiography.N Engl J Med.2008;359(22):2309–2311.

- ,.Gizmo idolatry.JAMA.2008;299(15):1830–1832.

- .Just because you can, doesn't mean that you should: a call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):398–402.

- ,.Impugning the integrity of medical science: the adverse effects of industry influence.JAMA.2008;299(15):1833–1835.

- ,,, et al.The 2007 ABJS Marshall Urist Award: the impact of direct‐to‐consumer advertising in orthopaedics.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2007;458:202–219.

- ,.Direct to consumer advertising in healthcare: history, benefits, and concerns.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2007;457:96–104.

- Connors,,, et al.The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators.JAMA.1996;276(11):889–897.

- ,,, et al.Assessment of the clinical effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in management of patients in intensive care (PAC‐Man): a randomised controlled trial.Lancet.2005;366(9484):472–477.

- ,,, et al.Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial.JAMA.2005;294(13):1625–1633.

- ,,, et al.Early use of the pulmonary artery catheter and outcomes in patients with shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial.JAMA.2003;290(20):2713–2720.

- Hand‐Carried Ultrasound—Reshaping the ultrasound marketplace. Available at: http://www.sonoworld.com/NewsStories/NewsStories.aspx?ID= 450. Accessed August2009.

- ,,.A new narrative for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2009;4(4):207–208.

- .Can heart failure be diagnosed in primary care?BMJ.2000;321(7255):188–189.

- ,,.Evidence of inadequate investigation and treatment of patients with heart failure.Br Heart J.1994;71(6):584–587.

- .Utility of hand‐carried ultrasound for consultative cardiology.Echocardiography.2003;20(5):463–469.

- .Tomorrow's stethoscope: the hand‐held ultrasound device?J S C Med Assoc.2006;102(10):345.

- ,,.The hand‐carried echocardiographic device as an aid to the physical examination.Echocardiography.2003;20(5):477–485.

- ,,,,,.Hospitalist performance of cardiac hand‐carried ultrasound after focused training.Am J Med.2007;120(11):1000–1004.

- ,,, et al.Hand‐carried ultrasound performed by hospitalists: does it improve the cardiac physical examination?Am J Med.2009;122(1):35–41.

- ,,.Should a hand‐carried ultrasound machine become standard equipment for every internist?Am J Med.2009;122(1):1–3.

- ,,,.How useful is hand‐carried bedside echocardiography in critically ill patients?J Am Coll Cardiol.2001;37(8):2019–2022.

- ,,,,,.The use of small personal ultrasound devices by internists without formal training in echocardiography.Eur J Echocardiogr.2003;4(2):141–147.

- ,,.Can hand‐carried ultrasound devices be extended for use by the noncardiology medical community?Echocardiography.2003;20(5):471–476.

- .Specific skill set and goals of focused echocardiography for critical care clinicians.Crit Care Med.2007;35(5 suppl):S144–S149.

- ,,, et al.The use of hand‐carried ultrasound in the hospital setting—a cost‐effective analysis.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2005;18(6):620–625.

- ,,, et al.A comparison by medicine residents of physical examination versus hand‐carried ultrasound for estimation of right atrial pressure.Am J Cardiol.2007;99(11):1614–1616.

- ,,, et al.Radial artery pulse pressure variation correlates with brachial artery peak velocity variation in ventilated subjects when measured by internal medicine residents using hand‐carried ultrasound devices.Chest.2007;131(5):1301–1307.

- ,,,,,.The rate at which residents learn to use hand‐held echocardiography at the bedside.Am J Med.2005;118(9):1010–1018.

- ,,,,.Diagnostic accuracy of new handheld echocardiography with Doppler and harmonic imaging properties.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2004;17(3):234–238.

- ,,,,,.Hand‐carried ultrasound performed at bedside in cardiology inpatient setting ‐ a comparative study with comprehensive echocardiography.Cardiovasc Ultrasound.2004;2:24.

- ,,Sade LE. Influence of hand‐carried ultrasound on bedside patient treatment decisions for consultative cardiology.J Am Soc Echocardiogr.2004;17(1):50–55.

- ,,,.Who is responsible for evaluating the safety and effectiveness of medical devices? The role of independent technology assessment.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(suppl 1):57–63.

- ,,.Newly approved does not always mean new and improved.JAMA.2008;299(13):1598–1600.

- ,.Indication creep: physician beware.CMAJ.2007;177(7):697,699.

- ,,,.Ultrasound‐guided interventional radiology in critical care.Crit Care Med.2007;35(5 suppl):S186–S197.

- ,.Pay now, benefits may follow—the case of cardiac computed tomographic angiography.N Engl J Med.2008;359(22):2309–2311.

- ,.Gizmo idolatry.JAMA.2008;299(15):1830–1832.

- .Just because you can, doesn't mean that you should: a call for the rational application of hospitalist comanagement.J Hosp Med.2008;3(5):398–402.

- ,.Impugning the integrity of medical science: the adverse effects of industry influence.JAMA.2008;299(15):1833–1835.

- ,,, et al.The 2007 ABJS Marshall Urist Award: the impact of direct‐to‐consumer advertising in orthopaedics.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2007;458:202–219.

- ,.Direct to consumer advertising in healthcare: history, benefits, and concerns.Clin Orthop Relat Res.2007;457:96–104.

- Connors,,, et al.The effectiveness of right heart catheterization in the initial care of critically ill patients. SUPPORT Investigators.JAMA.1996;276(11):889–897.

- ,,, et al.Assessment of the clinical effectiveness of pulmonary artery catheters in management of patients in intensive care (PAC‐Man): a randomised controlled trial.Lancet.2005;366(9484):472–477.

- ,,, et al.Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial.JAMA.2005;294(13):1625–1633.

- ,,, et al.Early use of the pulmonary artery catheter and outcomes in patients with shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized controlled trial.JAMA.2003;290(20):2713–2720.

Hospitalist Physician Leadership Skills

Physicians assume myriad leadership roles within medical institutions. Clinically‐oriented leadership roles can range from managing a small group of providers, to leading entire health systems, to heading up national quality improvement initiatives. While often competent in the practice of medicine, many physicians have not pursued structured management or administrative training. In a survey of Medicine Department Chairs at academic medical centers, none had advanced management degrees despite spending an average of 55% of their time on administrative duties. It is not uncommon for physicians to attend leadership development programs or management seminars, as evidenced by the increasing demand for education.1 Various methods for skill enhancement have been described24; however, the most effective approaches have yet to be determined.

Miller and Dollard5 and Bandura6, 7 have explained that behavioral contracts have evolved from social cognitive theory principles. These contracts are formal written agreements, often negotiated between 2 individuals, to facilitate behavior change. Typically, they involve a clear definition of expected behaviors with specific consequences (usually positive reinforcement).810 Their use in modifying physician behavior, particularly those related to leadership, has not been studied.

Hospitalist physicians represent the fastest growing specialty in the United States.11, 12 Among other responsibilities, they have taken on roles as leaders in hospital administration, education, quality improvement, and public health.1315 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the largest US organization committed to the practice of hospital medicine,16 has established Leadership Academies to prepare hospitalists for these duties. The goal of this study was to assess how hospitalist physicians' commitment to grow as leaders was expressed using behavioral contacts as a vehicle to clarify their intentions and whether behavioral change occurred over time.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative study design was selected to explore how current and future hospitalist leaders planned to modify their behaviors after participating in a hospitalist leadership training course. Participants were encouraged to complete a behavioral contract highlighting their personal goals.

Approximately 12 months later, follow‐up data were collected. Participants were sent copies of their behavioral contracts and surveyed about the extent to which they have realized their personal goals.

Subjects

Hospitalist leaders participating in the 4‐day level I or II leadership courses of the SHM Leadership Academy were studied.

Data Collection

In the final sessions of the 2007‐2008 Leadership Academy courses, participants completed an optional behavioral contract exercise in which they partnered with a colleague and were asked to identify 4 action plans they intended to implement upon their return home. These were written down and signed. Selected demographic information was also collected.

Follow‐up surveys were sent by mail and electronically to a subset of participants with completed behavioral contracts. A 5‐point Likert scale (strongly agree . . . strongly disagree) was used to assess the extent of adherence to the goals listed in the behavioral contracts.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using an editing organizing style, a qualitative analysis technique to find meaningful units or segments of text that both stand on their own and relate to the purpose of the study.12 With this method, the coding template emerges from the data. Two investigators independently analyzed the transcripts and created a coding template based on common themes identified among the participants. In cases of discrepant coding, the 2 investigators had discussions to reach consensus. The authors agreed on representative quotes for each theme. Triangulation was established through sharing results of the analysis with a subset of participants.

Follow‐up survey data was summarized descriptively showing proportion data.

Results

Response Rate and Participant Demographics

Out of 264 people who completed the course, 120 decided to participate in the optional behavioral contract exercise. The median age of participants was 38 years (Table 1). The majority were male (84; 70.0%), and hospitalist leaders (76; 63.3%). The median time in practice as a hospitalist was 4 years. Fewer than one‐half held an academic appointment (40; 33.3%) with most being at the rank of Assistant Professor (14; 11.7%). Most of the participants worked in a private hospital (80; 66.7%).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age in years [median (SD)] | 38 (8) |

| Male [n (%)] | 84 (70.0) |

| Years in practice as hospitalist [median (SD)] | 4 (13) |

| Leader of hospitalist program [n (%)] | 76 (63.3) |

| Academic affiliation [n (%)] | 40 (33.3) |

| Academic rank [n (%)] | |

| Instructor | 9 (7.5) |

| Assistant professor | 14 (11.7) |

| Associate professor | 13 (10.8) |

| Hospital type [n (%)] | |

| Private | 80 (66.7) |

| University | 15 (12.5) |

| Government | 2 (1.7) |

| Veterans administration | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) |

Results of Qualitative Analysis of Behavioral Contracts

From the analyses of the behavioral contracts, themes emerged related to ways in which participants hoped to develop and improve. The themes and the frequencies with which they were recorded in the behavioral contracts are shown in Table 2.

| Theme | Total Number of Times Theme Mentioned in All Behavioral Contracts | Number of Respondents Referring to Theme [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Improving communication and interpersonal skills | 132 | 70 (58.3) |

| Refinement of vision, goals, and strategic planning | 115 | 62 (51.7) |

| Improve intrapersonal development | 65 | 36 (30.0) |

| Enhance negotiation skills | 65 | 44 (36.7) |

| Commit to organizational change | 53 | 32 (26.7) |

| Understanding business drivers | 38 | 28 (23.3) |

| Setting performance and clinical metrics | 34 | 26 (21.7) |

| Strengthen interdepartmental relations | 32 | 26 (21.7) |

Improving Communication and Interpersonal Skills

A desire to improve communication and listening skills, particularly in the context of conflict resolution, was mentioned repeatedly. Heightened awareness about different personality types to allow for improved interpersonal relationships was another concept that was emphasized.

One female Instructor from an academic medical center described her intentions:

I will try to do a better job at assessing the behavioral tendencies of my partners and adjust my own style for more effective communication.

Refinement of Vision, Goals, and Strategic Planning

Physicians were committed to returning to their home institutions and embarking on initiatives to advance vision and goals of their groups within the context of strategic planning. Participants were interested in creating hospitalist‐specific mission statements, developing specific goals that take advantage of strengths and opportunities while minimizing internal weaknesses and considering external threats. They described wanting to align the interests of members of their hospitalist groups around a common goal.

A female hospitalist leader in private practice wished to:

Clearly define a group vision and commit to re‐evaluation on a regular basis to ensure we are on track . . . and conduct a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis to set future goals.

Improve Intrapersonal Development

Participants expressed desire to improve their leadership skills. Proposed goals included: (1) recognizing their weaknesses and soliciting feedback from colleagues, (2) minimizing emotional response to stress, (3) sharing their knowledge and skills for the benefit of peers, (4) delegating work more effectively to others, (5) reading suggested books on leadership, (6) serving as a positive role model and mentor, and (7) managing meetings and difficult coworkers more skillfully.

One female Assistant Professor from an academic medical center outlined:

I want to be able to: (1) manage up better and effectively negotiate with the administration on behalf of my group; (2) become better at leadership skills by using the tools offered at the Academy; and (3) effectively support my group members to develop their skills to become successful in their chosen niches. I will . . . improve the poor morale in my group.

Enhance Negotiation Skills

Many physician leaders identified negotiation principles and techniques as foundations for improvement for interactions within their own groups, as well as with the hospital administration.

A male private hospitalist leader working for 4 years as a hospitalist described plans to utilize negotiation skills within and outside the group:

Negotiate with my team of hospitalists to make them more compliant with the rules and regulations of the group, and negotiate an excellent contract with hospital administration. . . .

Commit to Organizational Change

The hospitalist respondents described their ability to influence organizational change given their unique position at the interface between patient care delivery and hospital administration. To realize organizational change, commonly cited ideas included recruitment and retention of clinically excellent practitioners, and developing standard protocols to facilitate quality improvement initiatives.

A male Instructor of Medicine listed select areas in which to become more involved:

Participation with the Chief Executive Officer of the company in quality improvement projects, calls to the primary care practitioners upon discharge, and the handoff process.

Other Themes

The final 3 themes included are: understanding business drivers; the establishment of better metrics to assess performance; and the strengthening of interdepartmental relations.

Follow‐up Data About Adherence to Plans Delineated in Behavioral Contracts

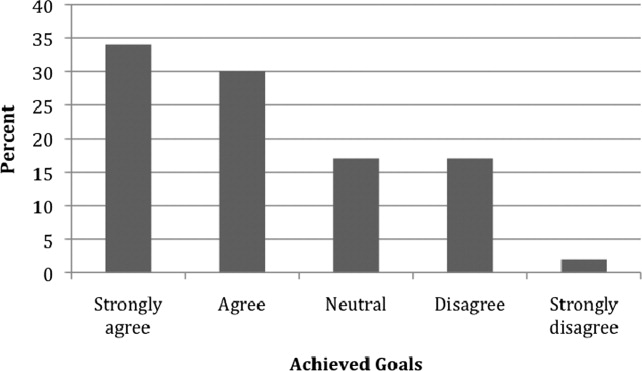

Out of 65 completed behavioral contracts from the 2007 Level I participants, 32 returned a follow‐up survey (response rate 49.3%). Figure 1 shows the extent to which respondents believed that they were compliant with their proposed plans for change or improvement. Degree of adherence was displayed as a proportion of total goals. Out of those who returned a follow‐up survey, all but 1 respondent either strongly agreed or agreed that they adhered to at least one of their goals (96.9%).

Select representative comments that illustrate the physicians' appreciation of using behavioral contracts include:

my approach to problems is a bit more analytical.

simple changes in how I approach people and interact with them has greatly improved my skills as a leader and allowed me to accomplish my goals with much less effort.

Discussion

Through the qualitative analysis of the behavioral contracts completed by participants of a Leadership Academy for hospitalists, we characterized the ways that hospitalist practitioners hoped to evolve as leaders. The major themes that emerged relate not only to their own growth and development but also their pledge to advance the success of the group or division. The level of commitment and impact of the behavioral contracts appear to be reinforced by an overwhelmingly positive response to adherence to personal goals one year after course participation. Communication and interpersonal development were most frequently cited in the behavioral contracts as areas for which the hospitalist leaders acknowledged a desire to grow. In a study of academic department of medicine chairs, communication skills were identified as being vital for effective leadership.3 The Chairs also recognized other proficiencies required for leading that were consistent with those outlined in the behavioral contracts: strategic planning, change management, team building, personnel management, and systems thinking. McDade et al.17 examined the effects of participation in an executive leadership program developed for female academic faculty in medical and dental schools in the United States and Canada. They noted increased self‐assessed leadership capabilities at 18 months after attending the program, across 10 leadership constructs taught in the classes. These leadership constructs resonate with the themes found in the plans for change described by our informants.

Hospitalists are assuming leadership roles in an increasing number and with greater scope; however, until now their perspectives on what skill sets are required to be successful have not been well documented. Significant time, effort, and money are invested into the development of hospitalists as leaders.4 The behavioral contract appears to be a tool acceptable to hospitalist physicians; perhaps it can be used as part annual reviews with hospitalists aspiring to be leaders.

Several limitations of the study shall be considered. First, not all participants attending the Leadership Academy opted to fill out the behavioral contracts. Second, this qualitative study is limited to those practitioners who are genuinely interested in growing as leaders as evidenced by their willingness to invest in going to the course. Third, follow‐up surveys relied on self‐assessment and it is not known whether actual realization of these goals occurred or the extent to which behavioral contracts were responsible. Further, follow‐up data were only completed by 49% percent of those targeted. However, hospitalists may be fairly resistant to being surveyed as evidenced by the fact that SHM's 2005‐2006 membership survey yielded a response rate of only 26%.18 Finally, many of the thematic goals were described by fewer than 50% of informants. However, it is important to note that the elements included on each person's behavioral contract emerged spontaneously. If subjects were specifically asked about each theme, the number of comments related to each would certainly be much higher. Qualitative analysis does not really allow us to know whether one theme is more important than another merely because it was mentioned more frequently.

Hospitalist leaders appear to be committed to professional growth and they have reported realization of goals delineated in their behavioral contracts. While varied methods are being used as part of physician leadership training programs, behavioral contracts may enhance promise for change.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Regina Hess for assistance in data preparation and Laurence Wellikson, MD, FHM, Russell Holman, MD and Erica Pearson (all from the SHM) for data collection.

Physicians assume myriad leadership roles within medical institutions. Clinically‐oriented leadership roles can range from managing a small group of providers, to leading entire health systems, to heading up national quality improvement initiatives. While often competent in the practice of medicine, many physicians have not pursued structured management or administrative training. In a survey of Medicine Department Chairs at academic medical centers, none had advanced management degrees despite spending an average of 55% of their time on administrative duties. It is not uncommon for physicians to attend leadership development programs or management seminars, as evidenced by the increasing demand for education.1 Various methods for skill enhancement have been described24; however, the most effective approaches have yet to be determined.

Miller and Dollard5 and Bandura6, 7 have explained that behavioral contracts have evolved from social cognitive theory principles. These contracts are formal written agreements, often negotiated between 2 individuals, to facilitate behavior change. Typically, they involve a clear definition of expected behaviors with specific consequences (usually positive reinforcement).810 Their use in modifying physician behavior, particularly those related to leadership, has not been studied.

Hospitalist physicians represent the fastest growing specialty in the United States.11, 12 Among other responsibilities, they have taken on roles as leaders in hospital administration, education, quality improvement, and public health.1315 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the largest US organization committed to the practice of hospital medicine,16 has established Leadership Academies to prepare hospitalists for these duties. The goal of this study was to assess how hospitalist physicians' commitment to grow as leaders was expressed using behavioral contacts as a vehicle to clarify their intentions and whether behavioral change occurred over time.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative study design was selected to explore how current and future hospitalist leaders planned to modify their behaviors after participating in a hospitalist leadership training course. Participants were encouraged to complete a behavioral contract highlighting their personal goals.

Approximately 12 months later, follow‐up data were collected. Participants were sent copies of their behavioral contracts and surveyed about the extent to which they have realized their personal goals.

Subjects

Hospitalist leaders participating in the 4‐day level I or II leadership courses of the SHM Leadership Academy were studied.

Data Collection

In the final sessions of the 2007‐2008 Leadership Academy courses, participants completed an optional behavioral contract exercise in which they partnered with a colleague and were asked to identify 4 action plans they intended to implement upon their return home. These were written down and signed. Selected demographic information was also collected.

Follow‐up surveys were sent by mail and electronically to a subset of participants with completed behavioral contracts. A 5‐point Likert scale (strongly agree . . . strongly disagree) was used to assess the extent of adherence to the goals listed in the behavioral contracts.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using an editing organizing style, a qualitative analysis technique to find meaningful units or segments of text that both stand on their own and relate to the purpose of the study.12 With this method, the coding template emerges from the data. Two investigators independently analyzed the transcripts and created a coding template based on common themes identified among the participants. In cases of discrepant coding, the 2 investigators had discussions to reach consensus. The authors agreed on representative quotes for each theme. Triangulation was established through sharing results of the analysis with a subset of participants.

Follow‐up survey data was summarized descriptively showing proportion data.

Results

Response Rate and Participant Demographics

Out of 264 people who completed the course, 120 decided to participate in the optional behavioral contract exercise. The median age of participants was 38 years (Table 1). The majority were male (84; 70.0%), and hospitalist leaders (76; 63.3%). The median time in practice as a hospitalist was 4 years. Fewer than one‐half held an academic appointment (40; 33.3%) with most being at the rank of Assistant Professor (14; 11.7%). Most of the participants worked in a private hospital (80; 66.7%).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age in years [median (SD)] | 38 (8) |

| Male [n (%)] | 84 (70.0) |

| Years in practice as hospitalist [median (SD)] | 4 (13) |

| Leader of hospitalist program [n (%)] | 76 (63.3) |

| Academic affiliation [n (%)] | 40 (33.3) |

| Academic rank [n (%)] | |

| Instructor | 9 (7.5) |

| Assistant professor | 14 (11.7) |

| Associate professor | 13 (10.8) |

| Hospital type [n (%)] | |

| Private | 80 (66.7) |

| University | 15 (12.5) |

| Government | 2 (1.7) |

| Veterans administration | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) |

Results of Qualitative Analysis of Behavioral Contracts

From the analyses of the behavioral contracts, themes emerged related to ways in which participants hoped to develop and improve. The themes and the frequencies with which they were recorded in the behavioral contracts are shown in Table 2.

| Theme | Total Number of Times Theme Mentioned in All Behavioral Contracts | Number of Respondents Referring to Theme [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Improving communication and interpersonal skills | 132 | 70 (58.3) |

| Refinement of vision, goals, and strategic planning | 115 | 62 (51.7) |

| Improve intrapersonal development | 65 | 36 (30.0) |

| Enhance negotiation skills | 65 | 44 (36.7) |

| Commit to organizational change | 53 | 32 (26.7) |

| Understanding business drivers | 38 | 28 (23.3) |

| Setting performance and clinical metrics | 34 | 26 (21.7) |

| Strengthen interdepartmental relations | 32 | 26 (21.7) |

Improving Communication and Interpersonal Skills

A desire to improve communication and listening skills, particularly in the context of conflict resolution, was mentioned repeatedly. Heightened awareness about different personality types to allow for improved interpersonal relationships was another concept that was emphasized.

One female Instructor from an academic medical center described her intentions:

I will try to do a better job at assessing the behavioral tendencies of my partners and adjust my own style for more effective communication.

Refinement of Vision, Goals, and Strategic Planning

Physicians were committed to returning to their home institutions and embarking on initiatives to advance vision and goals of their groups within the context of strategic planning. Participants were interested in creating hospitalist‐specific mission statements, developing specific goals that take advantage of strengths and opportunities while minimizing internal weaknesses and considering external threats. They described wanting to align the interests of members of their hospitalist groups around a common goal.

A female hospitalist leader in private practice wished to:

Clearly define a group vision and commit to re‐evaluation on a regular basis to ensure we are on track . . . and conduct a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis to set future goals.

Improve Intrapersonal Development

Participants expressed desire to improve their leadership skills. Proposed goals included: (1) recognizing their weaknesses and soliciting feedback from colleagues, (2) minimizing emotional response to stress, (3) sharing their knowledge and skills for the benefit of peers, (4) delegating work more effectively to others, (5) reading suggested books on leadership, (6) serving as a positive role model and mentor, and (7) managing meetings and difficult coworkers more skillfully.

One female Assistant Professor from an academic medical center outlined:

I want to be able to: (1) manage up better and effectively negotiate with the administration on behalf of my group; (2) become better at leadership skills by using the tools offered at the Academy; and (3) effectively support my group members to develop their skills to become successful in their chosen niches. I will . . . improve the poor morale in my group.

Enhance Negotiation Skills

Many physician leaders identified negotiation principles and techniques as foundations for improvement for interactions within their own groups, as well as with the hospital administration.

A male private hospitalist leader working for 4 years as a hospitalist described plans to utilize negotiation skills within and outside the group:

Negotiate with my team of hospitalists to make them more compliant with the rules and regulations of the group, and negotiate an excellent contract with hospital administration. . . .

Commit to Organizational Change

The hospitalist respondents described their ability to influence organizational change given their unique position at the interface between patient care delivery and hospital administration. To realize organizational change, commonly cited ideas included recruitment and retention of clinically excellent practitioners, and developing standard protocols to facilitate quality improvement initiatives.

A male Instructor of Medicine listed select areas in which to become more involved:

Participation with the Chief Executive Officer of the company in quality improvement projects, calls to the primary care practitioners upon discharge, and the handoff process.

Other Themes

The final 3 themes included are: understanding business drivers; the establishment of better metrics to assess performance; and the strengthening of interdepartmental relations.

Follow‐up Data About Adherence to Plans Delineated in Behavioral Contracts

Out of 65 completed behavioral contracts from the 2007 Level I participants, 32 returned a follow‐up survey (response rate 49.3%). Figure 1 shows the extent to which respondents believed that they were compliant with their proposed plans for change or improvement. Degree of adherence was displayed as a proportion of total goals. Out of those who returned a follow‐up survey, all but 1 respondent either strongly agreed or agreed that they adhered to at least one of their goals (96.9%).

Select representative comments that illustrate the physicians' appreciation of using behavioral contracts include:

my approach to problems is a bit more analytical.

simple changes in how I approach people and interact with them has greatly improved my skills as a leader and allowed me to accomplish my goals with much less effort.

Discussion

Through the qualitative analysis of the behavioral contracts completed by participants of a Leadership Academy for hospitalists, we characterized the ways that hospitalist practitioners hoped to evolve as leaders. The major themes that emerged relate not only to their own growth and development but also their pledge to advance the success of the group or division. The level of commitment and impact of the behavioral contracts appear to be reinforced by an overwhelmingly positive response to adherence to personal goals one year after course participation. Communication and interpersonal development were most frequently cited in the behavioral contracts as areas for which the hospitalist leaders acknowledged a desire to grow. In a study of academic department of medicine chairs, communication skills were identified as being vital for effective leadership.3 The Chairs also recognized other proficiencies required for leading that were consistent with those outlined in the behavioral contracts: strategic planning, change management, team building, personnel management, and systems thinking. McDade et al.17 examined the effects of participation in an executive leadership program developed for female academic faculty in medical and dental schools in the United States and Canada. They noted increased self‐assessed leadership capabilities at 18 months after attending the program, across 10 leadership constructs taught in the classes. These leadership constructs resonate with the themes found in the plans for change described by our informants.

Hospitalists are assuming leadership roles in an increasing number and with greater scope; however, until now their perspectives on what skill sets are required to be successful have not been well documented. Significant time, effort, and money are invested into the development of hospitalists as leaders.4 The behavioral contract appears to be a tool acceptable to hospitalist physicians; perhaps it can be used as part annual reviews with hospitalists aspiring to be leaders.