User login

HM10 PREVIEW: The Last Word

When you’re a fixture on the HM speaking circuit, it can be challenging to hold the attention of the crowd year after year—especially when your address is at lunchtime on the final day of SHM’s annual powwow, when a fair number of physicians will be checked out or looking to catch a cab to the airport.

The circumstances rarely faze Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. In fact, since helping pioneer the use of the term “hospitalist,” Dr. Wachter has become the signature closing presenter at SHM’s annual meetings. Sometimes the talk is a window into patient-safety issues; sometimes it’s an oral white paper on policy issues; and, just once, it was a message in a bottle from the future.

This year, though, Dr. Wachter, former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachters world.com), is keeping it local.

“It just strikes me that this year, more than any other in recent memory, what is happening in Washington will have a major impact on what hospitalists do for a living and what hospitalists will do for a living,” he says.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Few would disagree.

“Bob has his fingers on the pulse of how hospital medicine is evolving, where hospital medicine started,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of the annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “Bob’s really been great in terms of predicting what happens next.”

In light of the fluid realities of healthcare reform, Dr. Wachter’s exact words are likely to change several times before he speaks. Still, his themes have remained relatively constant over the years: He boasts of HM’s growth as a specialty and challenges hospitalists to act as leaders.

“I’ve always seen our field as not just reactive, but at the cutting edge of moving things forward,” he says. “This is an extremely important time because if (hospitalists) can be motivational, they can move the whole system forward.”

Hospitalists and group leaders will have to navigate the intricacies of Washington’s reform package. With that in mind, Dr. Wachter will speak about a number of hot policy topics:

- The future of bundled payments. Hospitalists are wary of how the government will reimburse the industry for delivery of care. Whether a new payment system rewards hospitals directly or physicians continue to bill for their services, HM leaders will need to keep abreast of changes.

- Continued migration toward “accountable-care organizations,” also known as ACOs, where providers partner and share responsibility for both the quality and cost of healthcare for a specific population of beneficiaries.

- Healthcare IT improvements. As the industry continues to embrace electronic health records, and industrywide metrics solidify, hospitalists can take leading roles as quality-improvement (QI) leaders.

- Dr. Watcher says hospitalists should use the changing nature of healthcare reform as an opportunity to take a leading role in the discussion.

“It’s not entirely clear how this will play out, but it is clear some piece of the legislation will push for more efficiency,” he says, “and hospitalists will be a major leader in that area.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTOS MATT FENSTERMACHER

When you’re a fixture on the HM speaking circuit, it can be challenging to hold the attention of the crowd year after year—especially when your address is at lunchtime on the final day of SHM’s annual powwow, when a fair number of physicians will be checked out or looking to catch a cab to the airport.

The circumstances rarely faze Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. In fact, since helping pioneer the use of the term “hospitalist,” Dr. Wachter has become the signature closing presenter at SHM’s annual meetings. Sometimes the talk is a window into patient-safety issues; sometimes it’s an oral white paper on policy issues; and, just once, it was a message in a bottle from the future.

This year, though, Dr. Wachter, former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachters world.com), is keeping it local.

“It just strikes me that this year, more than any other in recent memory, what is happening in Washington will have a major impact on what hospitalists do for a living and what hospitalists will do for a living,” he says.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Few would disagree.

“Bob has his fingers on the pulse of how hospital medicine is evolving, where hospital medicine started,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of the annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “Bob’s really been great in terms of predicting what happens next.”

In light of the fluid realities of healthcare reform, Dr. Wachter’s exact words are likely to change several times before he speaks. Still, his themes have remained relatively constant over the years: He boasts of HM’s growth as a specialty and challenges hospitalists to act as leaders.

“I’ve always seen our field as not just reactive, but at the cutting edge of moving things forward,” he says. “This is an extremely important time because if (hospitalists) can be motivational, they can move the whole system forward.”

Hospitalists and group leaders will have to navigate the intricacies of Washington’s reform package. With that in mind, Dr. Wachter will speak about a number of hot policy topics:

- The future of bundled payments. Hospitalists are wary of how the government will reimburse the industry for delivery of care. Whether a new payment system rewards hospitals directly or physicians continue to bill for their services, HM leaders will need to keep abreast of changes.

- Continued migration toward “accountable-care organizations,” also known as ACOs, where providers partner and share responsibility for both the quality and cost of healthcare for a specific population of beneficiaries.

- Healthcare IT improvements. As the industry continues to embrace electronic health records, and industrywide metrics solidify, hospitalists can take leading roles as quality-improvement (QI) leaders.

- Dr. Watcher says hospitalists should use the changing nature of healthcare reform as an opportunity to take a leading role in the discussion.

“It’s not entirely clear how this will play out, but it is clear some piece of the legislation will push for more efficiency,” he says, “and hospitalists will be a major leader in that area.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTOS MATT FENSTERMACHER

When you’re a fixture on the HM speaking circuit, it can be challenging to hold the attention of the crowd year after year—especially when your address is at lunchtime on the final day of SHM’s annual powwow, when a fair number of physicians will be checked out or looking to catch a cab to the airport.

The circumstances rarely faze Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, chief of the hospitalist division, professor, and associate chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California at San Francisco. In fact, since helping pioneer the use of the term “hospitalist,” Dr. Wachter has become the signature closing presenter at SHM’s annual meetings. Sometimes the talk is a window into patient-safety issues; sometimes it’s an oral white paper on policy issues; and, just once, it was a message in a bottle from the future.

This year, though, Dr. Wachter, former SHM president and author of the blog Wachter’s World (www.wachters world.com), is keeping it local.

“It just strikes me that this year, more than any other in recent memory, what is happening in Washington will have a major impact on what hospitalists do for a living and what hospitalists will do for a living,” he says.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Few would disagree.

“Bob has his fingers on the pulse of how hospital medicine is evolving, where hospital medicine started,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of the annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “Bob’s really been great in terms of predicting what happens next.”

In light of the fluid realities of healthcare reform, Dr. Wachter’s exact words are likely to change several times before he speaks. Still, his themes have remained relatively constant over the years: He boasts of HM’s growth as a specialty and challenges hospitalists to act as leaders.

“I’ve always seen our field as not just reactive, but at the cutting edge of moving things forward,” he says. “This is an extremely important time because if (hospitalists) can be motivational, they can move the whole system forward.”

Hospitalists and group leaders will have to navigate the intricacies of Washington’s reform package. With that in mind, Dr. Wachter will speak about a number of hot policy topics:

- The future of bundled payments. Hospitalists are wary of how the government will reimburse the industry for delivery of care. Whether a new payment system rewards hospitals directly or physicians continue to bill for their services, HM leaders will need to keep abreast of changes.

- Continued migration toward “accountable-care organizations,” also known as ACOs, where providers partner and share responsibility for both the quality and cost of healthcare for a specific population of beneficiaries.

- Healthcare IT improvements. As the industry continues to embrace electronic health records, and industrywide metrics solidify, hospitalists can take leading roles as quality-improvement (QI) leaders.

- Dr. Watcher says hospitalists should use the changing nature of healthcare reform as an opportunity to take a leading role in the discussion.

“It’s not entirely clear how this will play out, but it is clear some piece of the legislation will push for more efficiency,” he says, “and hospitalists will be a major leader in that area.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTOS MATT FENSTERMACHER

HM10 PREVIEW: Crystal Ball

He’s not a hospitalist. He’s not even a doctor. In fact, less than a decade ago, he was executive director of a Massachusetts water resources board and best known for his views on how to best clean up Boston Bay. But from his perch as president and CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Paul Levy is a leading voice in contemporary healthcare, quality measures, and transparency.

HM10’s keynote speaker is most well-known in both medical and management circles for launching a blog in 2006 about the daily operations of his institution, aptly found at www.runningahospital.blogspot.com. Levy, whose address is at 9 a.m. Friday, April 9, spoke to The Hospitalist about his views on the role HM practitioners can play in quality improvement (QI), the importance of communication in medicine, and what he hopes hospitalists can learn from the experiences of his hospital.

Question: What made you accept the offer to be the keynote speaker at HM10?

Answer: I have tremendous respect for the hospital medicine industry. They are positioned to be an exceptionally important part of the care delivery system. In terms of working alongside them, they’re also interesting people. I enjoy working with them.

Q: Why are you looking forward to speaking?

A: I’d like to share our experience with qualitative care improvements and process improvements. The hospitalists, because of their position within the hospital and their relationships (with specialists and with administrators in the C-suite), are on the vanguard of being able to truly improve how we deliver care.

Q: Your address is titled “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Hospital of the Future.” Can you provide an overview of the topics you plan to talk about?

A: It's a classic discussion on how you do process improvement. How do you standardize care? Once you standardize care ... how do you measure that? Hospitalists are in an excellent position to do that because they work on all of the different floors of their hospitals. They are in a position to make meaningful impacts on multiple floors.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Q: How do you encourage your HM physicians to do that?

A: I don’t have to. They do it. We have found it very valuable, and in our place, it’s led to better outcomes. That means better patient care.

Q: Can you give an example of that value to the institution?

A: We initiated a rapid-response program several years ago we call “Triggers.” When a patient displays certain symptoms—changes in heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, etc.—there is an automatic trigger that calls in a senior nurse and a senior attending physician. We have already demonstrated a reduction in fatalities and a reduction in mortality rates because of this. We have so few codes right now on our on floors that we had to move our codes to our simulators because residents were not getting enough training. It’s a good problem to have.

Q: Do you see more physicians, hospitalists particularly, embracing technology in the hopes of improving care delivery and process administration?

A: Sure. We have a group of residents who created some type of Wiki with their work. I’m not even sure how it works; it just happens. I know there are some hospitals out there preventing this from happening. I think that’s just stupid. It’s a fear that something proprietary or private will be posted for everyone to see. I don’t particularly think it’s founded. We’ve all heard stories about someone who leaves a folder full of files on the subway. Are we going to stop people from riding the subway?

Q: What do you think HM’s outlook is?

A: I think it’s bright. I’m kind of new to medicine. I’ve only been here about eight years. I kind of wonder what used to happen before hospitalists. I guess primary-care physicians came in early in the morning and late at night. That doesn’t sound like an efficient system to deliver care.

Q: What do you want conference attendees to take away from your words?

A: I just hope the stories I tell about process improvements help everyone in their institutions. It’s up to them.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTOS MATT FENSTERMACHER

He’s not a hospitalist. He’s not even a doctor. In fact, less than a decade ago, he was executive director of a Massachusetts water resources board and best known for his views on how to best clean up Boston Bay. But from his perch as president and CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Paul Levy is a leading voice in contemporary healthcare, quality measures, and transparency.

HM10’s keynote speaker is most well-known in both medical and management circles for launching a blog in 2006 about the daily operations of his institution, aptly found at www.runningahospital.blogspot.com. Levy, whose address is at 9 a.m. Friday, April 9, spoke to The Hospitalist about his views on the role HM practitioners can play in quality improvement (QI), the importance of communication in medicine, and what he hopes hospitalists can learn from the experiences of his hospital.

Question: What made you accept the offer to be the keynote speaker at HM10?

Answer: I have tremendous respect for the hospital medicine industry. They are positioned to be an exceptionally important part of the care delivery system. In terms of working alongside them, they’re also interesting people. I enjoy working with them.

Q: Why are you looking forward to speaking?

A: I’d like to share our experience with qualitative care improvements and process improvements. The hospitalists, because of their position within the hospital and their relationships (with specialists and with administrators in the C-suite), are on the vanguard of being able to truly improve how we deliver care.

Q: Your address is titled “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Hospital of the Future.” Can you provide an overview of the topics you plan to talk about?

A: It's a classic discussion on how you do process improvement. How do you standardize care? Once you standardize care ... how do you measure that? Hospitalists are in an excellent position to do that because they work on all of the different floors of their hospitals. They are in a position to make meaningful impacts on multiple floors.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Q: How do you encourage your HM physicians to do that?

A: I don’t have to. They do it. We have found it very valuable, and in our place, it’s led to better outcomes. That means better patient care.

Q: Can you give an example of that value to the institution?

A: We initiated a rapid-response program several years ago we call “Triggers.” When a patient displays certain symptoms—changes in heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, etc.—there is an automatic trigger that calls in a senior nurse and a senior attending physician. We have already demonstrated a reduction in fatalities and a reduction in mortality rates because of this. We have so few codes right now on our on floors that we had to move our codes to our simulators because residents were not getting enough training. It’s a good problem to have.

Q: Do you see more physicians, hospitalists particularly, embracing technology in the hopes of improving care delivery and process administration?

A: Sure. We have a group of residents who created some type of Wiki with their work. I’m not even sure how it works; it just happens. I know there are some hospitals out there preventing this from happening. I think that’s just stupid. It’s a fear that something proprietary or private will be posted for everyone to see. I don’t particularly think it’s founded. We’ve all heard stories about someone who leaves a folder full of files on the subway. Are we going to stop people from riding the subway?

Q: What do you think HM’s outlook is?

A: I think it’s bright. I’m kind of new to medicine. I’ve only been here about eight years. I kind of wonder what used to happen before hospitalists. I guess primary-care physicians came in early in the morning and late at night. That doesn’t sound like an efficient system to deliver care.

Q: What do you want conference attendees to take away from your words?

A: I just hope the stories I tell about process improvements help everyone in their institutions. It’s up to them.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTOS MATT FENSTERMACHER

He’s not a hospitalist. He’s not even a doctor. In fact, less than a decade ago, he was executive director of a Massachusetts water resources board and best known for his views on how to best clean up Boston Bay. But from his perch as president and CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Paul Levy is a leading voice in contemporary healthcare, quality measures, and transparency.

HM10’s keynote speaker is most well-known in both medical and management circles for launching a blog in 2006 about the daily operations of his institution, aptly found at www.runningahospital.blogspot.com. Levy, whose address is at 9 a.m. Friday, April 9, spoke to The Hospitalist about his views on the role HM practitioners can play in quality improvement (QI), the importance of communication in medicine, and what he hopes hospitalists can learn from the experiences of his hospital.

Question: What made you accept the offer to be the keynote speaker at HM10?

Answer: I have tremendous respect for the hospital medicine industry. They are positioned to be an exceptionally important part of the care delivery system. In terms of working alongside them, they’re also interesting people. I enjoy working with them.

Q: Why are you looking forward to speaking?

A: I’d like to share our experience with qualitative care improvements and process improvements. The hospitalists, because of their position within the hospital and their relationships (with specialists and with administrators in the C-suite), are on the vanguard of being able to truly improve how we deliver care.

Q: Your address is titled “The Hospitalist’s Role in the Hospital of the Future.” Can you provide an overview of the topics you plan to talk about?

A: It's a classic discussion on how you do process improvement. How do you standardize care? Once you standardize care ... how do you measure that? Hospitalists are in an excellent position to do that because they work on all of the different floors of their hospitals. They are in a position to make meaningful impacts on multiple floors.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

Q: How do you encourage your HM physicians to do that?

A: I don’t have to. They do it. We have found it very valuable, and in our place, it’s led to better outcomes. That means better patient care.

Q: Can you give an example of that value to the institution?

A: We initiated a rapid-response program several years ago we call “Triggers.” When a patient displays certain symptoms—changes in heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, etc.—there is an automatic trigger that calls in a senior nurse and a senior attending physician. We have already demonstrated a reduction in fatalities and a reduction in mortality rates because of this. We have so few codes right now on our on floors that we had to move our codes to our simulators because residents were not getting enough training. It’s a good problem to have.

Q: Do you see more physicians, hospitalists particularly, embracing technology in the hopes of improving care delivery and process administration?

A: Sure. We have a group of residents who created some type of Wiki with their work. I’m not even sure how it works; it just happens. I know there are some hospitals out there preventing this from happening. I think that’s just stupid. It’s a fear that something proprietary or private will be posted for everyone to see. I don’t particularly think it’s founded. We’ve all heard stories about someone who leaves a folder full of files on the subway. Are we going to stop people from riding the subway?

Q: What do you think HM’s outlook is?

A: I think it’s bright. I’m kind of new to medicine. I’ve only been here about eight years. I kind of wonder what used to happen before hospitalists. I guess primary-care physicians came in early in the morning and late at night. That doesn’t sound like an efficient system to deliver care.

Q: What do you want conference attendees to take away from your words?

A: I just hope the stories I tell about process improvements help everyone in their institutions. It’s up to them.

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTOS MATT FENSTERMACHER

HM10 PREVIEW: Bigger & Better

If a medical meeting of the minds is only as good as its CME options, then HM10 will be the best SHM annual meeting yet.

A pair of new pre-courses—“Essential Neurology for the Hospitalist” and “Early Career Hospitalist: Skills for Success”—will debut at HM10, which kicks off April 8 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., outside of Washington, D.C. The new learning sessions boost to 20 the number of Category 1 credits physicians can earn toward the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Physician Recognition Award. Last year, hospitalists could earn a maximum of 15 credits.

While both of the new pre-courses drew heavy interest among early registrants, the latter was particularly intriguing, says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

“It’s really going to allow our early-career hospitalists to acquire some of the skills they don’t necessarily acquire during residency, such as billing and coding and understanding of quality measures,” Dr. Jaffer boasts, “as well as how best to communicate with consultants, patients, and families. They’ll have a better understanding of how important some of these issues are. … They form the background, as well as the foundation, for one’s career as a hospitalist.”

Also new this year is the added attention being paid to the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) learning session, which led all pre-courses in early registration. The class is in its second year but is more appealing this year because of the new Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine via MOC. Working in conjunction with ABIM, the pre-course offers the opportunity for ABIM-certified physicians the chance to earn 20 points toward the Self-Evaluation of Medical Knowledge requirement of the MOC program. Two modules will be presented: Internal Medicine-Office Based and Internal Medicine-Hospital Based.

“There’s an updated module,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “(Attendees) should get really good information there.”

Also new this year is a series of interactive workshops SHM launched to provide topic-specific information from experts. Spread over three days, the 18 workshops include “Improving Care for the Hospitalized Elder,” “Ultrasound Imaging Skills for Invasive Beside Procedures,” and “Blood Management: Hospitalists in a New Role.”

The workshops, which are limited to 100 participants, are an attempt to engage a new class of HM devotees by recruiting a new class of speakers and leaders. “In previous years, we were not getting all our membership involved with the annual meeting,” Dr. Jaffer says. “We were really handpicking our speakers on experience, expertise, and how well they were known in their field and how good of speakers they were. This year, we really reached out.”

HM10 also features “special-interest forums” at 4:45 p.m. Friday, April 9. The informal sessions—on 18 topics ranging from “Information Technology” to “Women in HM”—afford hospitalists direct access to SHM board members, committee members, and staff. Barnes says the information gathered in last year’s sessions was discussed by SHM. For instance, the “Early Career Hospitalist” forum was the inspiration for one of the new pre-courses.

“We’re not real good at getting that message across, but I would say that those (forums) are extremely valuable,” Barnes says. “The same thing goes for the town hall (1 p.m. Sunday, April 11). That’s an opportunity to meet with the executive committee and board members, and ask them anything you want to.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

If a medical meeting of the minds is only as good as its CME options, then HM10 will be the best SHM annual meeting yet.

A pair of new pre-courses—“Essential Neurology for the Hospitalist” and “Early Career Hospitalist: Skills for Success”—will debut at HM10, which kicks off April 8 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., outside of Washington, D.C. The new learning sessions boost to 20 the number of Category 1 credits physicians can earn toward the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Physician Recognition Award. Last year, hospitalists could earn a maximum of 15 credits.

While both of the new pre-courses drew heavy interest among early registrants, the latter was particularly intriguing, says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

“It’s really going to allow our early-career hospitalists to acquire some of the skills they don’t necessarily acquire during residency, such as billing and coding and understanding of quality measures,” Dr. Jaffer boasts, “as well as how best to communicate with consultants, patients, and families. They’ll have a better understanding of how important some of these issues are. … They form the background, as well as the foundation, for one’s career as a hospitalist.”

Also new this year is the added attention being paid to the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) learning session, which led all pre-courses in early registration. The class is in its second year but is more appealing this year because of the new Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine via MOC. Working in conjunction with ABIM, the pre-course offers the opportunity for ABIM-certified physicians the chance to earn 20 points toward the Self-Evaluation of Medical Knowledge requirement of the MOC program. Two modules will be presented: Internal Medicine-Office Based and Internal Medicine-Hospital Based.

“There’s an updated module,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “(Attendees) should get really good information there.”

Also new this year is a series of interactive workshops SHM launched to provide topic-specific information from experts. Spread over three days, the 18 workshops include “Improving Care for the Hospitalized Elder,” “Ultrasound Imaging Skills for Invasive Beside Procedures,” and “Blood Management: Hospitalists in a New Role.”

The workshops, which are limited to 100 participants, are an attempt to engage a new class of HM devotees by recruiting a new class of speakers and leaders. “In previous years, we were not getting all our membership involved with the annual meeting,” Dr. Jaffer says. “We were really handpicking our speakers on experience, expertise, and how well they were known in their field and how good of speakers they were. This year, we really reached out.”

HM10 also features “special-interest forums” at 4:45 p.m. Friday, April 9. The informal sessions—on 18 topics ranging from “Information Technology” to “Women in HM”—afford hospitalists direct access to SHM board members, committee members, and staff. Barnes says the information gathered in last year’s sessions was discussed by SHM. For instance, the “Early Career Hospitalist” forum was the inspiration for one of the new pre-courses.

“We’re not real good at getting that message across, but I would say that those (forums) are extremely valuable,” Barnes says. “The same thing goes for the town hall (1 p.m. Sunday, April 11). That’s an opportunity to meet with the executive committee and board members, and ask them anything you want to.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

If a medical meeting of the minds is only as good as its CME options, then HM10 will be the best SHM annual meeting yet.

A pair of new pre-courses—“Essential Neurology for the Hospitalist” and “Early Career Hospitalist: Skills for Success”—will debut at HM10, which kicks off April 8 at the Gaylord National Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md., outside of Washington, D.C. The new learning sessions boost to 20 the number of Category 1 credits physicians can earn toward the American Medical Association’s (AMA) Physician Recognition Award. Last year, hospitalists could earn a maximum of 15 credits.

While both of the new pre-courses drew heavy interest among early registrants, the latter was particularly intriguing, says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida.

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

“It’s really going to allow our early-career hospitalists to acquire some of the skills they don’t necessarily acquire during residency, such as billing and coding and understanding of quality measures,” Dr. Jaffer boasts, “as well as how best to communicate with consultants, patients, and families. They’ll have a better understanding of how important some of these issues are. … They form the background, as well as the foundation, for one’s career as a hospitalist.”

Also new this year is the added attention being paid to the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Maintenance of Certification (MOC) learning session, which led all pre-courses in early registration. The class is in its second year but is more appealing this year because of the new Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine via MOC. Working in conjunction with ABIM, the pre-course offers the opportunity for ABIM-certified physicians the chance to earn 20 points toward the Self-Evaluation of Medical Knowledge requirement of the MOC program. Two modules will be presented: Internal Medicine-Office Based and Internal Medicine-Hospital Based.

“There’s an updated module,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “(Attendees) should get really good information there.”

Also new this year is a series of interactive workshops SHM launched to provide topic-specific information from experts. Spread over three days, the 18 workshops include “Improving Care for the Hospitalized Elder,” “Ultrasound Imaging Skills for Invasive Beside Procedures,” and “Blood Management: Hospitalists in a New Role.”

The workshops, which are limited to 100 participants, are an attempt to engage a new class of HM devotees by recruiting a new class of speakers and leaders. “In previous years, we were not getting all our membership involved with the annual meeting,” Dr. Jaffer says. “We were really handpicking our speakers on experience, expertise, and how well they were known in their field and how good of speakers they were. This year, we really reached out.”

HM10 also features “special-interest forums” at 4:45 p.m. Friday, April 9. The informal sessions—on 18 topics ranging from “Information Technology” to “Women in HM”—afford hospitalists direct access to SHM board members, committee members, and staff. Barnes says the information gathered in last year’s sessions was discussed by SHM. For instance, the “Early Career Hospitalist” forum was the inspiration for one of the new pre-courses.

“We’re not real good at getting that message across, but I would say that those (forums) are extremely valuable,” Barnes says. “The same thing goes for the town hall (1 p.m. Sunday, April 11). That’s an opportunity to meet with the executive committee and board members, and ask them anything you want to.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

HM10 PREVIEW: Divide & Conquer

The National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP)—now known as SHM—first held an annual meeting in the spring of 1998 in San Diego. Some 100 hospitalists attended the largest gathering of the nascent field. A little more than a decade later, 2,000-plus hospitalists crowded together in Chicago for HM09.

That exponential growth is tied to a host of factors, mostly the swelling ranks of hospitalists. But in terms of conventioneers, the year-over-year spikes in attendance mean that more and more first-timers are attending SHM’s annual gathering. In fact, SHM estimates that 30% of attendees are first-timers.

“Over the last five years, we’ve seen a significant increase in attendance over each year, with the culmination being that 2009 sold out,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “There are those who return year after year, and new members. It’s primarily new members.”

The growth in the annual meeting attendance confirms that HM is growing in numbers and influence. More and more physicians are making HM a career, and the annual meeting is the perfect place to learn more about the specialty and all it has to offer.

“Sometimes new physicians become hospitalists thinking that it might be a transition time for them. By going to these meetings, they can really cement in their minds the excitement and enthusiasm for being a hospital medicine physician,” says Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, founder of Inpatient Physicians Associations, a Lincoln, Neb.-based operator of three HM groups. “If they were thinking about transitioning out of HM into a fellowship, this might really encourage them to think twice about that.”

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

A four-day conference with more than 90 educational sessions can be intimidating to the first-time attendee. How does a rookie navigate all that “excitement and enthusiasm”? Which sessions does one attend? How does a young hospitalist get matched up with a mentor? What should a veteran hospitalist be learning that they can relay to their colleagues back home?

“First and foremost, they get to interact with colleagues from all over the country, as well as we now have hospitalists from other parts of the world actually coming to our annual meeting,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “So one is the ability to interact and talk about the fast-changing field of hospital medicine. Two is that they get to learn about both clinical topics as well as other areas in HM that are more practical, either related to operations, quality improvement, patient safety, research.

“The third thing is that you get a chance to present your work, whether you’re a researcher, a QI guru, [or] you’re an educator. You get a chance to present your work in the form of a poster or an oral presentation. Fourth, you also get a chance to see a lot of the work that our colleagues from all across the country and the world are doing in HM to actually change it.”

The key to extracting all that information is preparation, according to those who have attended the meeting in the past. That includes checking out the pre-course schedule online, prioritizing meetings that relate to one’s day-to-day responsibilities, picking the educational tracks that appeal most, and taking advantage of the exhibit hall, which runs the length of the conference.

Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, FHM, has been to five SHM annual meetings, and has attended three pre-courses in that time. As medical director of the hospitalist service at Johnston Medical Center in Smithfield, N.C., he has found the learning sessions on practice management and billing and coding to be the most helpful. He recommends both to first-timers looking to accumulate real-world tips they can apply to their HM practices.

There is “a constant battle that we face trying to justify why you’re asking for more resources,” Dr. Adewunmi says. “To be able to do that convincingly, you need to be able to demonstrate your worth. … For people who have never gone to any of the pre-courses, any of them are a great tool. The amount of knowledge you come away with is pretty phenomenal. You’re given the little nuggets you need to do whatever you need to do.”

Dr. Bossard, a member of Team Hospitalist, estimates he’s been to 10 of the 13 annual meetings. He usually travels with colleagues and makes sure to coordinate educational tracks before the conference begins so that the group avoids redundancy by splitting up sessions.

“Divide and conquer,” Dr. Bossard adds. “We always bring it back to our group in smaller, bullet-type fashion. We all get a taste of sessions we weren’t able to attend.”

Barnes agrees that planning ahead is the key to success. “Do it based on what your primary role is,” she says. “Is your primary role research? Are you an academic hospitalist? Do you have an important role leading quality initiatives? Are you a group leader? At the end of the day, you can follow a track all the way down or you can jump across tracks—whatever is appealing.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

The National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP)—now known as SHM—first held an annual meeting in the spring of 1998 in San Diego. Some 100 hospitalists attended the largest gathering of the nascent field. A little more than a decade later, 2,000-plus hospitalists crowded together in Chicago for HM09.

That exponential growth is tied to a host of factors, mostly the swelling ranks of hospitalists. But in terms of conventioneers, the year-over-year spikes in attendance mean that more and more first-timers are attending SHM’s annual gathering. In fact, SHM estimates that 30% of attendees are first-timers.

“Over the last five years, we’ve seen a significant increase in attendance over each year, with the culmination being that 2009 sold out,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “There are those who return year after year, and new members. It’s primarily new members.”

The growth in the annual meeting attendance confirms that HM is growing in numbers and influence. More and more physicians are making HM a career, and the annual meeting is the perfect place to learn more about the specialty and all it has to offer.

“Sometimes new physicians become hospitalists thinking that it might be a transition time for them. By going to these meetings, they can really cement in their minds the excitement and enthusiasm for being a hospital medicine physician,” says Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, founder of Inpatient Physicians Associations, a Lincoln, Neb.-based operator of three HM groups. “If they were thinking about transitioning out of HM into a fellowship, this might really encourage them to think twice about that.”

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

A four-day conference with more than 90 educational sessions can be intimidating to the first-time attendee. How does a rookie navigate all that “excitement and enthusiasm”? Which sessions does one attend? How does a young hospitalist get matched up with a mentor? What should a veteran hospitalist be learning that they can relay to their colleagues back home?

“First and foremost, they get to interact with colleagues from all over the country, as well as we now have hospitalists from other parts of the world actually coming to our annual meeting,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “So one is the ability to interact and talk about the fast-changing field of hospital medicine. Two is that they get to learn about both clinical topics as well as other areas in HM that are more practical, either related to operations, quality improvement, patient safety, research.

“The third thing is that you get a chance to present your work, whether you’re a researcher, a QI guru, [or] you’re an educator. You get a chance to present your work in the form of a poster or an oral presentation. Fourth, you also get a chance to see a lot of the work that our colleagues from all across the country and the world are doing in HM to actually change it.”

The key to extracting all that information is preparation, according to those who have attended the meeting in the past. That includes checking out the pre-course schedule online, prioritizing meetings that relate to one’s day-to-day responsibilities, picking the educational tracks that appeal most, and taking advantage of the exhibit hall, which runs the length of the conference.

Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, FHM, has been to five SHM annual meetings, and has attended three pre-courses in that time. As medical director of the hospitalist service at Johnston Medical Center in Smithfield, N.C., he has found the learning sessions on practice management and billing and coding to be the most helpful. He recommends both to first-timers looking to accumulate real-world tips they can apply to their HM practices.

There is “a constant battle that we face trying to justify why you’re asking for more resources,” Dr. Adewunmi says. “To be able to do that convincingly, you need to be able to demonstrate your worth. … For people who have never gone to any of the pre-courses, any of them are a great tool. The amount of knowledge you come away with is pretty phenomenal. You’re given the little nuggets you need to do whatever you need to do.”

Dr. Bossard, a member of Team Hospitalist, estimates he’s been to 10 of the 13 annual meetings. He usually travels with colleagues and makes sure to coordinate educational tracks before the conference begins so that the group avoids redundancy by splitting up sessions.

“Divide and conquer,” Dr. Bossard adds. “We always bring it back to our group in smaller, bullet-type fashion. We all get a taste of sessions we weren’t able to attend.”

Barnes agrees that planning ahead is the key to success. “Do it based on what your primary role is,” she says. “Is your primary role research? Are you an academic hospitalist? Do you have an important role leading quality initiatives? Are you a group leader? At the end of the day, you can follow a track all the way down or you can jump across tracks—whatever is appealing.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

The National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP)—now known as SHM—first held an annual meeting in the spring of 1998 in San Diego. Some 100 hospitalists attended the largest gathering of the nascent field. A little more than a decade later, 2,000-plus hospitalists crowded together in Chicago for HM09.

That exponential growth is tied to a host of factors, mostly the swelling ranks of hospitalists. But in terms of conventioneers, the year-over-year spikes in attendance mean that more and more first-timers are attending SHM’s annual gathering. In fact, SHM estimates that 30% of attendees are first-timers.

“Over the last five years, we’ve seen a significant increase in attendance over each year, with the culmination being that 2009 sold out,” says Geri Barnes, SHM senior director of education and meetings. “There are those who return year after year, and new members. It’s primarily new members.”

The growth in the annual meeting attendance confirms that HM is growing in numbers and influence. More and more physicians are making HM a career, and the annual meeting is the perfect place to learn more about the specialty and all it has to offer.

“Sometimes new physicians become hospitalists thinking that it might be a transition time for them. By going to these meetings, they can really cement in their minds the excitement and enthusiasm for being a hospital medicine physician,” says Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, founder of Inpatient Physicians Associations, a Lincoln, Neb.-based operator of three HM groups. “If they were thinking about transitioning out of HM into a fellowship, this might really encourage them to think twice about that.”

More HM10 Preview

Hospitalists will gather in the shadows of the national healthcare reform debate

Plan ahead to maximize your HM10 experience

Hospital CEO, HM10 keynote speaker sees bright future for hospitalists

Annual meetings sell out, so get your ticket now

Washington, D.C., is ripe with sights to see and cherry blossoms to admire

HM10 expands hospitalist opportunities for education and interaction

HM pioneer Bob Wachter to address Washington’s impact on hospitalists

You may also

HM10 PREVIEW SUPPLEMENT

in pdf format.

A four-day conference with more than 90 educational sessions can be intimidating to the first-time attendee. How does a rookie navigate all that “excitement and enthusiasm”? Which sessions does one attend? How does a young hospitalist get matched up with a mentor? What should a veteran hospitalist be learning that they can relay to their colleagues back home?

“First and foremost, they get to interact with colleagues from all over the country, as well as we now have hospitalists from other parts of the world actually coming to our annual meeting,” says Amir Jaffer, MD, FHM, chair of SHM’s annual meeting committee, associate professor, and division chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “So one is the ability to interact and talk about the fast-changing field of hospital medicine. Two is that they get to learn about both clinical topics as well as other areas in HM that are more practical, either related to operations, quality improvement, patient safety, research.

“The third thing is that you get a chance to present your work, whether you’re a researcher, a QI guru, [or] you’re an educator. You get a chance to present your work in the form of a poster or an oral presentation. Fourth, you also get a chance to see a lot of the work that our colleagues from all across the country and the world are doing in HM to actually change it.”

The key to extracting all that information is preparation, according to those who have attended the meeting in the past. That includes checking out the pre-course schedule online, prioritizing meetings that relate to one’s day-to-day responsibilities, picking the educational tracks that appeal most, and taking advantage of the exhibit hall, which runs the length of the conference.

Femi Adewunmi, MD, MBA, FHM, has been to five SHM annual meetings, and has attended three pre-courses in that time. As medical director of the hospitalist service at Johnston Medical Center in Smithfield, N.C., he has found the learning sessions on practice management and billing and coding to be the most helpful. He recommends both to first-timers looking to accumulate real-world tips they can apply to their HM practices.

There is “a constant battle that we face trying to justify why you’re asking for more resources,” Dr. Adewunmi says. “To be able to do that convincingly, you need to be able to demonstrate your worth. … For people who have never gone to any of the pre-courses, any of them are a great tool. The amount of knowledge you come away with is pretty phenomenal. You’re given the little nuggets you need to do whatever you need to do.”

Dr. Bossard, a member of Team Hospitalist, estimates he’s been to 10 of the 13 annual meetings. He usually travels with colleagues and makes sure to coordinate educational tracks before the conference begins so that the group avoids redundancy by splitting up sessions.

“Divide and conquer,” Dr. Bossard adds. “We always bring it back to our group in smaller, bullet-type fashion. We all get a taste of sessions we weren’t able to attend.”

Barnes agrees that planning ahead is the key to success. “Do it based on what your primary role is,” she says. “Is your primary role research? Are you an academic hospitalist? Do you have an important role leading quality initiatives? Are you a group leader? At the end of the day, you can follow a track all the way down or you can jump across tracks—whatever is appealing.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer based in New Jersey.

PHOTO MATT FENSTERMACHER

Hospital-Acquired Conditions & The Hospitalist

Hospitalist Neal Axon, MD, first became aware of an important change in his hospital’s policies last year while attending to an elderly patient the morning after admission to the community hospital where he works part time.

“This new form appeared in the chart requesting a urinalysis for my patient, who’d had a Foley catheter placed,” says Dr. Axon, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “I didn’t know why, so I asked. I was told that it was now necessary to document that there was no UTI present on admission.” He asked the charge nurse, “So what do I do now that the catheter has been in place for 12 hours and has colonization without a true infection?”

The next thing he heard: silence.

The new form Dr. Axon encountered was an outgrowth of the requirements of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which ordered Medicare to withhold additional hospital payments for hospital-acquired complications (HAC) developed during a hospital stay. One result of the new rule is that much of a hospital’s response to these initiatives has been placed in the hands of the hospitalist. From accurate documentation of complications already present on admission (POA), to confirming that guidelines for treatment are being followed, to taking the lead on review of staff practices and education, hospitalists are in a position to have a wide-ranging impact on patient care and the financial health of their institutions.

Congress Pushes Reforms

In order for Medicare to not provide a reimbursement, an HAC has to be high-cost and/or high-volume, result in the assignment of the case to a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and “could reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines,” says Barry Straube, MD, chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “CMS was to implement a process where we would not pay the hospitals additional money for these complications.”

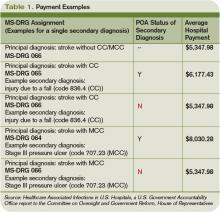

The new rules mean Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of Medicare Severity Diagnostic-Related Groups (MS-DRG), which better reflect the complexity of a patient’s illness. The biggest change was a three-tiered payment schedule: a base level for the diagnosis, a second level adding money to reflect the presence of comorbidities and complications, and a third for major complications and comorbidities (see Table 1, p. 31).

“Instituting HACs means that hospitals would no longer receive the comorbidity and complication payments if the only reason a case qualified for higher payment was the HAC,” Dr. Straube explains. “We did carve out a POA exception for those conditions that were acquired outside of the hospital. HACs only impact additional payments; the hospitals are still paid for the diagnosis that resulted in the hospital admission.”

CMS also identifies three “never events” it won’t reimburse for (see “A Brief History of Never Events,” p. 35): performing the wrong procedure, performing a procedure on the wrong body part, and performing a procedure on the wrong patient. “Neither hospitals nor physicians that are involved in such egregious situations would be paid,” Dr. Straube says.

Preventability: Subject of Controversy

The big questions surrounding HACs: Could they reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines? How preventable are HACs? Who decides if a complication is preventable, and therefore payment for services is withheld?

They’re concerns that are widespread among physicians, hospital administrators, and regulators alike.

“The legislation required the conditions to be ‘reasonably preventable’ using established clinical guidelines,” Dr. Straube says. “We did not have to show 100% prevention. In an imperfect world, they might still take place occasionally, but with good medical care, almost all of these are preventable in this day and age.”

For CMS, the preventable conditions are an either/or situation: Either they existed prior to admission and are subject to payment, or they did not exist at admission and additional payment for the complication will not be made. “HACs do not currently consider a patient’s individual risk for complications,” says Jennifer Meddings, MD, MSc, clinical lecturer and health researcher in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know the best strategies to prevent complications in ideal patients, and these are reflected in the HACs. In real life, many of our patients just don’t fit into the guidelines for many reasons—and you have to individualize care.”

Dr. Meddings points to DVT as a prime example. For a certain number of inpatients, the guidelines can be followed to perfection. In other patients (e.g., those with kidney conditions), previous reactions to a medication or an individual’s predisposition to clotting might interfere with treatment. However, CMS doesn’t allow appeals of nonpayment decisions for HACs based on individual circumstances.

Some experts think the rigidness of the payment policy forces physicians to treat patients exactly to guidelines. Even then, payment could be declined if an HAC develops.

“One of the points of most discussion is how preventable some of these are, particularly when choosing those you are no longer going to pay for,” Dr. Meddings says. “Many of the complications currently under review have patients that are at higher risk than others. How much our prevention strategies can alleviate or reduce the risk varies widely among patients.”

Impact on HM Practice

Many of the preventable conditions outlined by CMS do not directly affect hospitalist payment. However, hospitalists often find themselves responsible for properly documenting admission and care.

“The rule changes regarding payment for HACs are only related to hospital payments, and to date, most physicians, including hospitalists, are not directly at financial risk,” says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine in the divisions of Health Care Policy Research and General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. “Although hospitalists have no financial skin in the game, there are plenty of reasons they would take an interest in addressing HACs in their hospital. In particular, they are often seen as the ‘go-to’ group for quality improvement in their hospitals.”

For example, some HM groups have been active in working with teams of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers to address local policies and procedures on prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) and DVT.

“This has certainly necessitated a team approach,” says Shaun Frost, MD, FHM, an SHM board member and regional medical director for Cogent Healthcare in St. Paul, Minn. “For many of the HACs that apply to our population of patients, the hospitalist alone cannot be expected to solely execute effective quality improvements. It takes a team effort in that regard, and one that includes many different disciplines.”

The Cogent-affiliated hospitalist group at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia formed a task force to address issues with catheter-associated UTI. One initiative focused on educating all providers involved in the proper care of the catheters and similar interventions. A secondary focus of the project was an inventory of current practices and procedures.

“It was discovered that we did not have an automatic stop order for Foley catheters, so in some situations, they were likely being left in longer than needed while nursing [staff] tried to contact a physician,” Dr. Frost explains. “We created standardized order sets that include criteria for continuing the catheter. Once the criteria are no longer applicable, nursing will be able to discontinue it.”

Although CMS has only recently turned the spotlight on HACs and never events, hospitalists have been heavily involved in the patient-safety arena for years. “It is not a new phenomenon that hospitalists work for healthcare delivery and healthcare system improvement,” Dr. Meddings says.

Hospital administration at Temple University Hospital recognized the HM group’s quality-improvement (QI) work, and has “specifically charged us with spreading the work we have done in patient safety to the entire house,” Dr. Frost says. “That speaks to the administration’s opinion of the power of the HM program to assist with institution-wide QI initiatives.”

Documentation Is Key

Beyond applying proven methods to avoid HACs, hospitalists can make a difference through documentation. If the hospitalist notes all conditions when the patient first presents to the hospital, additional comorbidity and complication payments should be made.

“The part that probably has the greatest impact on the day-to-day practice of a hospitalist is the increased importance of documentation throughout the hospital episode,” Dr. Meddings says. “If complications are occurring and they are not present in the chart, the coders may not recognize that it has occurred and will not know to include it in the bill. This can have an adverse impact on the hospital and its finances.”

Documentation issues can impact hospital payment in several ways:

- Hospitals might receive additional payment by default if certain HACs are described incorrectly or without sufficient detail (e.g., receiving overpayment because the physician did not indicate a UTI was in fact a catheter-associated UTI);

- As more attention is invested in documenting all conditions POA, hospitals might be coding more comorbidities overall than previously, which also will generate additional payment for hospitals as any POA condition is eligible for increased payment; and

- Hospitals might lose payment when admitting providers fail to adequately document the condition as POA (e.g., a pre-existing decubitus ulcer not detected until the second day of the hospital stay).

The descriptions to be used in coding are very detailed. UTIs, for example, have one code to document the POA assessment, another code to show that a UTI occurred, and a third code to indicate it was catheter-associated. Each code requires appropriate documentation in the chart (see Table 1, above).

The impact hospitalists have on care and payment is not the same across the HAC spectrum. For instance, documenting the presence of pressure ulcers might be easier than distinguishing colonization from infection in those admitted with in-dwelling urinary catheters. Others, such as DVT or vascular catheter-associated infections, are rarely POA unless they are part of the admitting diagnosis.

“This new focus on hospital-acquired conditions may work to the patient’s benefit,” Dr. Meddings says. “The inclusion of pressure ulcers has led to increased attention to skin exams on admission and preventive measures during hospitalizations. In the past, skin exams upon admission may have been given a lower priority, but that has changed.”

Dr. Meddings is concerned that the new rules could force the shifting of resources to areas where the hospital could lose money. If, when, and how many changes will actually take place is still up in the air. “Resource shifting is a concern whenever there is any sort of pay-for-performance attention directed toward one particular complication,” she says. “To balance this, many of the strategies hospitals used to prevent complications are not specific to just the diagnosis that is covered by the HAC.”

Dr. Meddings also hopes the new focus on preventable conditions will have a “halo effect” in the healthcare community. For instance, CMS mandating DVT prevention following orthopedic operations will, hopefully, result in a greater awareness of the problem in other susceptible patients.

POA Indicators

Since hospitalists often perform the initial patient history, physical, and other admission work, they are in the best position to find and document POA indicators (see Table 2, p. below). Proper notes on such things as UTIs present and the state of skin integrity are an important part of making sure the hospital is paid correctly for the care it provides.

Education on the specific definition of each potential HAC is required to help physicians avoid overtreatment of certain conditions, especially UTIs. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines all UTIs as symptomatic. Therefore, the screening of all admitted patients, regardless of symptoms, is wasteful and unlikely to help the hospital’s bottom line.

“If you start screening everyone that comes through the door so you don’t miss any pre-existing UTIs, you are going to find a lot of asymptomatic colonization,” Dr. Wald says. “You are also going to spend a lot of money and time on studies and possibly treatments that may not yield many true infections. It is important that physicians know the definition of these HACs to help avoid needless interventions.”

Minimal Loss

Many hospital administrators and physicians were worried when the HAC program was first announced. Much of the stress and concern, however, seems to have dissipated. CMS estimated the HAC program would save Medicare $21 million in fiscal year 2009. Others, such as Peter McNair and colleagues writing in Health Affairs, suggest the actual impact is closer to $1.1 million.1 The CMS-projected impact of the HAC provision in fiscal-year 2009 was $21 million, out of more than $100 billion in payments.

“I think the HACs will not have a major impact because of the way payments are made,” says internist Robert Berenson, MD, a fellow at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., who has studied Medicare policy issues extensively, and for two years was in charge of Medicare payment policies at the Health Care Finance Administration, the precursor to CMS. “Patients who have HACs often have another comorbidity that would kick them into a higher payment category regardless of the presence of a hospital-acquired complication. In the end, it is probably more symbolic and unlikely to make a major dent in hospital income—at least at this point.”

Another limitation to CMS nonpayment for HACs is the issue of deciding which conditions are truly preventable. Dr. Berenson questions the ability of the current system to identify many additional complications for which this approach will be feasible.

“CMS has laid out its strategy, suggesting that we should be able to continue increasing the number of conditions for which providers would be paid differently based on quality,” he says. “Many observers question whether there will ever be measurement tools that are robust enough, and there will be a wide agreement on the preventability of enough conditions that this initiative will go very far.”

Although hospitalists might not face a direct financial risk, they still have their hospitals’ best interest—and their reputations—on the line. “Hospitalists care about preventing complications,” Dr. Wald says. “We are very engaged in working with our hospitals to improve care, maximize quality, and minimize cost.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- McNair PD, Luft HS, Bindman AB. Medicare’s policy not to pay for treating hospital-acquired conditions: the impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1485-1493.

TOP IMAGE SOURCE: KAREEM RIZKHALLA/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Hospitalist Neal Axon, MD, first became aware of an important change in his hospital’s policies last year while attending to an elderly patient the morning after admission to the community hospital where he works part time.

“This new form appeared in the chart requesting a urinalysis for my patient, who’d had a Foley catheter placed,” says Dr. Axon, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “I didn’t know why, so I asked. I was told that it was now necessary to document that there was no UTI present on admission.” He asked the charge nurse, “So what do I do now that the catheter has been in place for 12 hours and has colonization without a true infection?”

The next thing he heard: silence.

The new form Dr. Axon encountered was an outgrowth of the requirements of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which ordered Medicare to withhold additional hospital payments for hospital-acquired complications (HAC) developed during a hospital stay. One result of the new rule is that much of a hospital’s response to these initiatives has been placed in the hands of the hospitalist. From accurate documentation of complications already present on admission (POA), to confirming that guidelines for treatment are being followed, to taking the lead on review of staff practices and education, hospitalists are in a position to have a wide-ranging impact on patient care and the financial health of their institutions.

Congress Pushes Reforms

In order for Medicare to not provide a reimbursement, an HAC has to be high-cost and/or high-volume, result in the assignment of the case to a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and “could reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines,” says Barry Straube, MD, chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “CMS was to implement a process where we would not pay the hospitals additional money for these complications.”

The new rules mean Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of Medicare Severity Diagnostic-Related Groups (MS-DRG), which better reflect the complexity of a patient’s illness. The biggest change was a three-tiered payment schedule: a base level for the diagnosis, a second level adding money to reflect the presence of comorbidities and complications, and a third for major complications and comorbidities (see Table 1, p. 31).

“Instituting HACs means that hospitals would no longer receive the comorbidity and complication payments if the only reason a case qualified for higher payment was the HAC,” Dr. Straube explains. “We did carve out a POA exception for those conditions that were acquired outside of the hospital. HACs only impact additional payments; the hospitals are still paid for the diagnosis that resulted in the hospital admission.”

CMS also identifies three “never events” it won’t reimburse for (see “A Brief History of Never Events,” p. 35): performing the wrong procedure, performing a procedure on the wrong body part, and performing a procedure on the wrong patient. “Neither hospitals nor physicians that are involved in such egregious situations would be paid,” Dr. Straube says.

Preventability: Subject of Controversy

The big questions surrounding HACs: Could they reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines? How preventable are HACs? Who decides if a complication is preventable, and therefore payment for services is withheld?

They’re concerns that are widespread among physicians, hospital administrators, and regulators alike.

“The legislation required the conditions to be ‘reasonably preventable’ using established clinical guidelines,” Dr. Straube says. “We did not have to show 100% prevention. In an imperfect world, they might still take place occasionally, but with good medical care, almost all of these are preventable in this day and age.”

For CMS, the preventable conditions are an either/or situation: Either they existed prior to admission and are subject to payment, or they did not exist at admission and additional payment for the complication will not be made. “HACs do not currently consider a patient’s individual risk for complications,” says Jennifer Meddings, MD, MSc, clinical lecturer and health researcher in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know the best strategies to prevent complications in ideal patients, and these are reflected in the HACs. In real life, many of our patients just don’t fit into the guidelines for many reasons—and you have to individualize care.”

Dr. Meddings points to DVT as a prime example. For a certain number of inpatients, the guidelines can be followed to perfection. In other patients (e.g., those with kidney conditions), previous reactions to a medication or an individual’s predisposition to clotting might interfere with treatment. However, CMS doesn’t allow appeals of nonpayment decisions for HACs based on individual circumstances.

Some experts think the rigidness of the payment policy forces physicians to treat patients exactly to guidelines. Even then, payment could be declined if an HAC develops.

“One of the points of most discussion is how preventable some of these are, particularly when choosing those you are no longer going to pay for,” Dr. Meddings says. “Many of the complications currently under review have patients that are at higher risk than others. How much our prevention strategies can alleviate or reduce the risk varies widely among patients.”

Impact on HM Practice

Many of the preventable conditions outlined by CMS do not directly affect hospitalist payment. However, hospitalists often find themselves responsible for properly documenting admission and care.