User login

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: PEERist Program Provides Rural Nebraska Hospital 24/7 HM Coverage

Hospitalist programs take many shapes, and the organizational flowchart typically depends on the number and makeup of the physicians, the hospital, the patients, and the community. Adequately covering the needs of inpatient units can be especially frustrating in rural communities, some hospitalists say.

“There are only five physicians total in our town,” says Gary Ensz, MD, a partner in the Auburn Family Health Center in Auburn, Neb. “In addition to being family practitioners, we are our own hospitalists. Covering the emergency room, seeing patients in clinic, and following hospitalized patients is a big burden.”

To address these issues, Dr. Ensz and his partners developed the Physician Extender Emergency Room Hospitalist (PEERist) program. They utilize physician assistants (PAs) to serve many hospitalist functions under their supervision.

“We hired PAs to work in the hospital and the emergency room,” Dr. Ensz explains. “They do not work in the clinic and then take call. Their only responsibilities are to the hospital and ER.”

—Gary Ensz, MD, partner, Auburn (Neb.) Family Health Center

PEERists work under protocols addressing treatment concerns and give guidance on when physicians should be called. On-call doctors round in the morning with the PA. The physicians like this approach, Dr. Ensz says, because they see the PEERist when it is convenient for them; before, they would leave clinic patients to attend to concerns at the hospital.

Impact of ER Call

“For most of us practicing in rural situations, the demands of ER call force people to retire,” Dr. Ensz says. “Now we have someone at the hospital highly trained and, as they get more experience, actually do some work better simply because they are there all the time. At worst, you now have two sets of hands working on the patient.”

PAs work a rotating schedule of up to 72 hours with as many as nine days off in a row. PAs can be recruited from a much larger area; in fact, one commutes four hours each way. PEERists say the time off makes it easier to do things with their families or work another job.

Other Benefits

In addition to pluses associated with the practice, Dr. Ensz is seeing other benefits, such as closer working relationships with the nurses. He also stresses that his hospital now has 24/7 in-house coverage, something almost unheard of in small rural hospitals.

One of the more subtle improvements might have been in getting people to the hospital quicker. “It wasn’t unusual for someone to come to clinic with symptoms they had for a while,” Dr. Ensz says. “The PEERists being in-house all the time have done away with these concerns.”

Hospitalist programs take many shapes, and the organizational flowchart typically depends on the number and makeup of the physicians, the hospital, the patients, and the community. Adequately covering the needs of inpatient units can be especially frustrating in rural communities, some hospitalists say.

“There are only five physicians total in our town,” says Gary Ensz, MD, a partner in the Auburn Family Health Center in Auburn, Neb. “In addition to being family practitioners, we are our own hospitalists. Covering the emergency room, seeing patients in clinic, and following hospitalized patients is a big burden.”

To address these issues, Dr. Ensz and his partners developed the Physician Extender Emergency Room Hospitalist (PEERist) program. They utilize physician assistants (PAs) to serve many hospitalist functions under their supervision.

“We hired PAs to work in the hospital and the emergency room,” Dr. Ensz explains. “They do not work in the clinic and then take call. Their only responsibilities are to the hospital and ER.”

—Gary Ensz, MD, partner, Auburn (Neb.) Family Health Center

PEERists work under protocols addressing treatment concerns and give guidance on when physicians should be called. On-call doctors round in the morning with the PA. The physicians like this approach, Dr. Ensz says, because they see the PEERist when it is convenient for them; before, they would leave clinic patients to attend to concerns at the hospital.

Impact of ER Call

“For most of us practicing in rural situations, the demands of ER call force people to retire,” Dr. Ensz says. “Now we have someone at the hospital highly trained and, as they get more experience, actually do some work better simply because they are there all the time. At worst, you now have two sets of hands working on the patient.”

PAs work a rotating schedule of up to 72 hours with as many as nine days off in a row. PAs can be recruited from a much larger area; in fact, one commutes four hours each way. PEERists say the time off makes it easier to do things with their families or work another job.

Other Benefits

In addition to pluses associated with the practice, Dr. Ensz is seeing other benefits, such as closer working relationships with the nurses. He also stresses that his hospital now has 24/7 in-house coverage, something almost unheard of in small rural hospitals.

One of the more subtle improvements might have been in getting people to the hospital quicker. “It wasn’t unusual for someone to come to clinic with symptoms they had for a while,” Dr. Ensz says. “The PEERists being in-house all the time have done away with these concerns.”

Hospitalist programs take many shapes, and the organizational flowchart typically depends on the number and makeup of the physicians, the hospital, the patients, and the community. Adequately covering the needs of inpatient units can be especially frustrating in rural communities, some hospitalists say.

“There are only five physicians total in our town,” says Gary Ensz, MD, a partner in the Auburn Family Health Center in Auburn, Neb. “In addition to being family practitioners, we are our own hospitalists. Covering the emergency room, seeing patients in clinic, and following hospitalized patients is a big burden.”

To address these issues, Dr. Ensz and his partners developed the Physician Extender Emergency Room Hospitalist (PEERist) program. They utilize physician assistants (PAs) to serve many hospitalist functions under their supervision.

“We hired PAs to work in the hospital and the emergency room,” Dr. Ensz explains. “They do not work in the clinic and then take call. Their only responsibilities are to the hospital and ER.”

—Gary Ensz, MD, partner, Auburn (Neb.) Family Health Center

PEERists work under protocols addressing treatment concerns and give guidance on when physicians should be called. On-call doctors round in the morning with the PA. The physicians like this approach, Dr. Ensz says, because they see the PEERist when it is convenient for them; before, they would leave clinic patients to attend to concerns at the hospital.

Impact of ER Call

“For most of us practicing in rural situations, the demands of ER call force people to retire,” Dr. Ensz says. “Now we have someone at the hospital highly trained and, as they get more experience, actually do some work better simply because they are there all the time. At worst, you now have two sets of hands working on the patient.”

PAs work a rotating schedule of up to 72 hours with as many as nine days off in a row. PAs can be recruited from a much larger area; in fact, one commutes four hours each way. PEERists say the time off makes it easier to do things with their families or work another job.

Other Benefits

In addition to pluses associated with the practice, Dr. Ensz is seeing other benefits, such as closer working relationships with the nurses. He also stresses that his hospital now has 24/7 in-house coverage, something almost unheard of in small rural hospitals.

One of the more subtle improvements might have been in getting people to the hospital quicker. “It wasn’t unusual for someone to come to clinic with symptoms they had for a while,” Dr. Ensz says. “The PEERists being in-house all the time have done away with these concerns.”

Nurse Practitioners, Physician Assistants to the Rescue

In 2004, the hospitalist group at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor faced a manpower problem: In a refrain common to hospitalist groups around the country, changes in duty-hour regulations were making it harder for medical residents to continue to provide inpatient coverage at the same levels as before.

Addressing the issue was difficult for the HM group and hospital administrators; they were going to need a significant number of new providers, and qualified physicians were in short supply. To address these issues, the HM group chose to add nonphysician providers (NPP) to their service.

“NPPs had worked at UM for a long time in other areas,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, SFHM, associate director of hospitalist management. “We had just created a new service that was hiring new people and thought NPPs would help in providing services.”

Hiring NPPs helped solve the University of Michigan’s problem, and the tactic has helped solve manpower issues at numerous HM groups around the country. But deciding whether your HM group should hire physicians, NPPs—usually nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs)—or some combination of the two will not be easy. It is a complex decision, one that requires following state-level licensing and practice laws as well as local hospital bylaws and federal and private insurance payment rules. Such decisions also mean HM group directors need to keep in mind case mixes and the personalities of the physicians in the practice.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution,” says Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, corporate medical director for Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta. “Not all environments are well-suited to NPP practice. Even when it is, you can’t just throw an NPP into the mix on their own with the expectation they will be successful.”

Whether it’s covering admissions, streamlining discharges, or working as an integral part of a care team, NPPs can be the solution expanding HM groups are looking for.

“Our physicians depend on NPPs to help them complete patient care in a more efficient manner and work to enhance continuity of care,” says Mary Whitehead, RN, APRN-BC, FNP, of Hospital Medicine Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “We lower physician rounding time so patients are seen sooner and tests are requested sooner. In addition, the patients really appreciate the extra time we can spend with them.”

Trained, Licensed, Available

NPs must be registered nurses with clinical experience before they can enroll in an advanced degree program, which usually results in a master’s degree or doctorate. Generally, a state board of nursing, or a state board jointly with the state medical board, regulates NPs.

PAs are trained in more of a traditional medical model. They have a variable education level all the way up to a PhD, although more states are requiring at least a master’s degree. Practice and other legal parameters most often come under the authority of state medical boards.

NPPs can provide additional medical expertise to patients, says Ryan Genzink, PA, a physician assistant with Hospitalists of Western Michigan in Grand Rapids and the American Academy of Physician Assistants’ medical liaison to SHM. “One of the challenges faced by physicians is that they often have to be in two places at once,” he says. “There is a recognition that teams provide better care for complicated patients.”

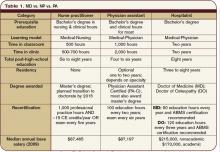

NPPs generally practice under the supervision of a physician hospitalist. Some states allow a greater degree of independence for NPs. However, most NPs and PAs are required to have a practice agreement outlining their responsibilities and the amount of oversight required (see Table 1, p. 39). There is no such thing as a “fire and forget” NPP.

“The practice needs to thoroughly understand the legal environment early in the process,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist director at Bellevue (Wash.) Medical Center, partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and SHM cofounder. “NPPs are not a ‘hospitalist lite’ that can function entirely like a hospitalist.”

Hospital bylaws, which can vary greatly by city, county, or state, are another important consideration before you hire an NPP.

“In some areas, NPPs may not be able to practice in the ICU,” Dr. Wilson says. “In others, the physician may be required to see the patient instead of consulting with the NPP. The idiosyncrasies of the individual hospital’s bylaws may impact the efficiency of the NPP/MD team.”

Physician Characteristics

Environmental variables—namely, the personality of the physicians within the practice—should be considered before you head down the NPP path. It makes little practical or financial sense to spend the time and effort of hiring an NPP if the physicians still insist on doing all the work.

“[It’s] one of the most significant factors in successfully integrating an NPP program,” Dr. Wilson says. “Will [physicians] be able to tolerate some degree of uncertainty when letting others see their patients? Are they open to adapting to different practice styles? The thing we see most often in practices that use NPPs to their advantage is the recognition that there is an important role for the nonphysician at the bedside.”

Some physicians hesitate to work with NPPs, while others welcome the extra help and unique experience NPPs offer. Experts agree that forcing NPPs on a physician is not a good idea. They also agree that, especially when beginning a new program, group directors should let physicians who are interested in working with NPPs take the lead. As NPP use in the group matures, many of those who were at first unwilling can decide that there is a place for NPPs in their practice.

Case Mix Is Key

The types and kinds of patient seen might limit the use of NPPs in hospitalist practice. “Our experience is that acuity and complexity of the care, especially as it relates to diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making, makes it difficult for NPPs to function independently,” Dr. Parekh says.

Dr. Wilson agrees. “Depending on the specific attributes of the setting, a service with both high-complexity and high-acuity patients may be a more challenging environment to realize the efficiencies of NPPs,” he says. “There is a relationship between complexity, acuity, and physician involvement.”

Even so, a continuum of NPP use in HM practice is achievable. For example, as a patient improves, an NPP might be able to take on a larger role in treatment by participating in discharge planning. In more acute patients, the NPP can save valuable physician time by coordinating with consultants, staying on top of treatments, and consolidating clinically important data for the physician.

Many Models in Use

Historically, the widespread use of alternative providers began in 2004 as a result of the changes to resident duty-hours. The restrictions created a workforce gap, which led to a large number of new positions in hospitals nationwide. Many of HM’s early adopters essentially went with what they knew.

“We work in teams where the physician, NPP, and nurse see a group of patients similar in function to an attending, resident, and RN,” Genzink says. “We see ‘our’ patients in a collaborative fashion.”

There are other models that have proven successful in the correct setting. Some HM groups use specialist NPPs to cover specific clinical areas, such as orthopedics or oncology. This not only develops a cadre of providers with excellent understanding of their patients, but it also frees up physician time for more acute and complicated patients.

“Our physicians depend on us helping them get patient care completed more efficiently, so that length of stay is acceptable, and to enhance continuity of care,” says Whitehead, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners’ liaison to SHM. “Having an NPP visit the patient daily, documenting progress, greatly enhances communications between physicians and consultants.”

Other groups have NPPs specialize by function—for example, they cover all admissions or work mainly with discharging a patient. Some groups have the physician see the patient on admission, work out a care plan, then turn over management to the NPP. Many agree that most NPPs are best utilized by having them cover specific shifts, such as overnight call or on a swing shift, to help during peak demand.

Monetary and Time Commitments

The financial impact of NPPs on a hospitalist practice depends on many factors. Groups will need to look not only at the salary and benefit costs associated with the position, but also how best to fit that person into the billing system.

Salary and benefit comparisons are fairly straightforward: The State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data, produced by SHM and the Medical Group Management Association, shows median total compensation for adult hospitalists at $215,000 per year; NPP compensation is around $87,000.1

The general cost of benefits (health insurance, retirement, etc.) is fairly typical throughout a hospitalist practice, so there should be little difference between a new FTE hospitalist or NPP. Other considerations, including office space and support staff, would be roughly the same if the group hired a physician. The cost of continuing education and malpractice insurance likely will be less with an NPP, but it is best to check before making a new hire.

After the outgo has been established, the next step is to look at the differences in reimbursement for NPPs vs. physicians. Here, again, the math gets tricky. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pay NPPs at 85% of the physician rate for a specific diagnosis. However, if there is direct physician involvement, the claim can be filed as “shared billing” and reimbursed at 100%.

For some hospitalist practices, adding NPPs is an easy decision to make. Dr. Parekh says his group already has policies in place that require a physician to see the patient every day. In that case, no extra physician time is necessary, so shared billing makes sense. Other hospitals’ bylaws might have similar requirements.

For practices in which the NPP is able to work with less oversight, it might be better to bill at 85% rather than use the physician time to meet shared-billing criteria. Even in practices with greater NPP autonomy, such variables as case mix and patient acuity might enter into the equation. If the patient is sick enough that the physician is involved for a significant amount of time, then shared billing probably is best.

Experts say group directors and hiring managers should look carefully at contracts with private insurers, too. There most likely will be considerable variation in how each plan handles NPP claims.

Managing performance expectations can have an impact on the successful use of NPPs in a hospitalist practice. Setting realistic goals and groupwide understanding of what the NPPs’ roles will be is crucial. The practice should look at the work that needs to be done and decide if that work provides a genuinely valuable role for an NPP.

Hire for Need, Not Desperation

“The mistake I see most often is hiring an NPP because a practice is desperate for help,” says Martin Buser, MPH, FACHE, a partner in Hospitalist Management Resources, LLC, in San Diego. “Smart practices are looking at NPPs, evaluating where they do the most good, and then setting out their role and expectations based on these needs and the practice environment.”

Hiring mistakes can be compounded if the NPP is not a good match to the job description or group expectations. If the practice hires an NPP fresh out of school, the group will need to establish training and have the new hire work more closely with physicians. If, on the other hand, an NP has 10 years of experience in an ICU, or a PA has worked in the ED for the past five years, a higher level of autonomy can be granted sooner. However, NPPs with established backgrounds are almost as rare as experienced hospitalists (see “Integrating NPPs Into HM Practice,” p. 38).

Inevitably, there will be changes in the interactions between patients and the hospitalists, as both physicians and NPPs become more comfortable with the other’s practice style, as well as each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

MD-to-NPP Ratio Varies

The practice structure and optimal mix of NPPs to MDs is something that will be specific to the hospitalist group. “We don’t really have good studies on this subject,” Buser says. “I usually get worried when we exceed two NPPs to one MD.”

Others disagree. Dr. Parekh, who works in an academic center, says his group has been successful having one MD work with as many as three NPPs. At the other end, Dr. Wilson says his 10 years of experience suggest 1:1 is the most efficient ratio.

However, all of them agree that having one NPP work with more than one physician is not sustainable. The NPP will be less familiar with each doctor’s practice style, what kind of information they need, and how things should be presented. If two or more hospitalists share an NPP, there can be internal friction over division of the NPP’s time, as well as extending the time before the MDs have a good feel for the NPP’s strengths and weaknesses.

In the final analysis, the HM group has to look at the amount and type of work available. In some cases, it will make financial and clinical sense to bring on an NPP. Under other circumstances, an FTE hospitalist is the best fit.

“Sustainability, quality, and efficiency are the drivers for NPP/MD teams. Increasing pressure to offset program costs is not,” Dr. Wilson says. “You do it because it helps sustain the program, helps with recruiting, and effects your efficiency.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- Medical Group Management Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine. State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. 2010. Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.

In 2004, the hospitalist group at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor faced a manpower problem: In a refrain common to hospitalist groups around the country, changes in duty-hour regulations were making it harder for medical residents to continue to provide inpatient coverage at the same levels as before.

Addressing the issue was difficult for the HM group and hospital administrators; they were going to need a significant number of new providers, and qualified physicians were in short supply. To address these issues, the HM group chose to add nonphysician providers (NPP) to their service.

“NPPs had worked at UM for a long time in other areas,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, SFHM, associate director of hospitalist management. “We had just created a new service that was hiring new people and thought NPPs would help in providing services.”

Hiring NPPs helped solve the University of Michigan’s problem, and the tactic has helped solve manpower issues at numerous HM groups around the country. But deciding whether your HM group should hire physicians, NPPs—usually nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs)—or some combination of the two will not be easy. It is a complex decision, one that requires following state-level licensing and practice laws as well as local hospital bylaws and federal and private insurance payment rules. Such decisions also mean HM group directors need to keep in mind case mixes and the personalities of the physicians in the practice.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution,” says Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, corporate medical director for Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta. “Not all environments are well-suited to NPP practice. Even when it is, you can’t just throw an NPP into the mix on their own with the expectation they will be successful.”

Whether it’s covering admissions, streamlining discharges, or working as an integral part of a care team, NPPs can be the solution expanding HM groups are looking for.

“Our physicians depend on NPPs to help them complete patient care in a more efficient manner and work to enhance continuity of care,” says Mary Whitehead, RN, APRN-BC, FNP, of Hospital Medicine Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “We lower physician rounding time so patients are seen sooner and tests are requested sooner. In addition, the patients really appreciate the extra time we can spend with them.”

Trained, Licensed, Available

NPs must be registered nurses with clinical experience before they can enroll in an advanced degree program, which usually results in a master’s degree or doctorate. Generally, a state board of nursing, or a state board jointly with the state medical board, regulates NPs.

PAs are trained in more of a traditional medical model. They have a variable education level all the way up to a PhD, although more states are requiring at least a master’s degree. Practice and other legal parameters most often come under the authority of state medical boards.

NPPs can provide additional medical expertise to patients, says Ryan Genzink, PA, a physician assistant with Hospitalists of Western Michigan in Grand Rapids and the American Academy of Physician Assistants’ medical liaison to SHM. “One of the challenges faced by physicians is that they often have to be in two places at once,” he says. “There is a recognition that teams provide better care for complicated patients.”

NPPs generally practice under the supervision of a physician hospitalist. Some states allow a greater degree of independence for NPs. However, most NPs and PAs are required to have a practice agreement outlining their responsibilities and the amount of oversight required (see Table 1, p. 39). There is no such thing as a “fire and forget” NPP.

“The practice needs to thoroughly understand the legal environment early in the process,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist director at Bellevue (Wash.) Medical Center, partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and SHM cofounder. “NPPs are not a ‘hospitalist lite’ that can function entirely like a hospitalist.”

Hospital bylaws, which can vary greatly by city, county, or state, are another important consideration before you hire an NPP.

“In some areas, NPPs may not be able to practice in the ICU,” Dr. Wilson says. “In others, the physician may be required to see the patient instead of consulting with the NPP. The idiosyncrasies of the individual hospital’s bylaws may impact the efficiency of the NPP/MD team.”

Physician Characteristics

Environmental variables—namely, the personality of the physicians within the practice—should be considered before you head down the NPP path. It makes little practical or financial sense to spend the time and effort of hiring an NPP if the physicians still insist on doing all the work.

“[It’s] one of the most significant factors in successfully integrating an NPP program,” Dr. Wilson says. “Will [physicians] be able to tolerate some degree of uncertainty when letting others see their patients? Are they open to adapting to different practice styles? The thing we see most often in practices that use NPPs to their advantage is the recognition that there is an important role for the nonphysician at the bedside.”

Some physicians hesitate to work with NPPs, while others welcome the extra help and unique experience NPPs offer. Experts agree that forcing NPPs on a physician is not a good idea. They also agree that, especially when beginning a new program, group directors should let physicians who are interested in working with NPPs take the lead. As NPP use in the group matures, many of those who were at first unwilling can decide that there is a place for NPPs in their practice.

Case Mix Is Key

The types and kinds of patient seen might limit the use of NPPs in hospitalist practice. “Our experience is that acuity and complexity of the care, especially as it relates to diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making, makes it difficult for NPPs to function independently,” Dr. Parekh says.

Dr. Wilson agrees. “Depending on the specific attributes of the setting, a service with both high-complexity and high-acuity patients may be a more challenging environment to realize the efficiencies of NPPs,” he says. “There is a relationship between complexity, acuity, and physician involvement.”

Even so, a continuum of NPP use in HM practice is achievable. For example, as a patient improves, an NPP might be able to take on a larger role in treatment by participating in discharge planning. In more acute patients, the NPP can save valuable physician time by coordinating with consultants, staying on top of treatments, and consolidating clinically important data for the physician.

Many Models in Use

Historically, the widespread use of alternative providers began in 2004 as a result of the changes to resident duty-hours. The restrictions created a workforce gap, which led to a large number of new positions in hospitals nationwide. Many of HM’s early adopters essentially went with what they knew.

“We work in teams where the physician, NPP, and nurse see a group of patients similar in function to an attending, resident, and RN,” Genzink says. “We see ‘our’ patients in a collaborative fashion.”

There are other models that have proven successful in the correct setting. Some HM groups use specialist NPPs to cover specific clinical areas, such as orthopedics or oncology. This not only develops a cadre of providers with excellent understanding of their patients, but it also frees up physician time for more acute and complicated patients.

“Our physicians depend on us helping them get patient care completed more efficiently, so that length of stay is acceptable, and to enhance continuity of care,” says Whitehead, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners’ liaison to SHM. “Having an NPP visit the patient daily, documenting progress, greatly enhances communications between physicians and consultants.”

Other groups have NPPs specialize by function—for example, they cover all admissions or work mainly with discharging a patient. Some groups have the physician see the patient on admission, work out a care plan, then turn over management to the NPP. Many agree that most NPPs are best utilized by having them cover specific shifts, such as overnight call or on a swing shift, to help during peak demand.

Monetary and Time Commitments

The financial impact of NPPs on a hospitalist practice depends on many factors. Groups will need to look not only at the salary and benefit costs associated with the position, but also how best to fit that person into the billing system.

Salary and benefit comparisons are fairly straightforward: The State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data, produced by SHM and the Medical Group Management Association, shows median total compensation for adult hospitalists at $215,000 per year; NPP compensation is around $87,000.1

The general cost of benefits (health insurance, retirement, etc.) is fairly typical throughout a hospitalist practice, so there should be little difference between a new FTE hospitalist or NPP. Other considerations, including office space and support staff, would be roughly the same if the group hired a physician. The cost of continuing education and malpractice insurance likely will be less with an NPP, but it is best to check before making a new hire.

After the outgo has been established, the next step is to look at the differences in reimbursement for NPPs vs. physicians. Here, again, the math gets tricky. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pay NPPs at 85% of the physician rate for a specific diagnosis. However, if there is direct physician involvement, the claim can be filed as “shared billing” and reimbursed at 100%.

For some hospitalist practices, adding NPPs is an easy decision to make. Dr. Parekh says his group already has policies in place that require a physician to see the patient every day. In that case, no extra physician time is necessary, so shared billing makes sense. Other hospitals’ bylaws might have similar requirements.

For practices in which the NPP is able to work with less oversight, it might be better to bill at 85% rather than use the physician time to meet shared-billing criteria. Even in practices with greater NPP autonomy, such variables as case mix and patient acuity might enter into the equation. If the patient is sick enough that the physician is involved for a significant amount of time, then shared billing probably is best.

Experts say group directors and hiring managers should look carefully at contracts with private insurers, too. There most likely will be considerable variation in how each plan handles NPP claims.

Managing performance expectations can have an impact on the successful use of NPPs in a hospitalist practice. Setting realistic goals and groupwide understanding of what the NPPs’ roles will be is crucial. The practice should look at the work that needs to be done and decide if that work provides a genuinely valuable role for an NPP.

Hire for Need, Not Desperation

“The mistake I see most often is hiring an NPP because a practice is desperate for help,” says Martin Buser, MPH, FACHE, a partner in Hospitalist Management Resources, LLC, in San Diego. “Smart practices are looking at NPPs, evaluating where they do the most good, and then setting out their role and expectations based on these needs and the practice environment.”

Hiring mistakes can be compounded if the NPP is not a good match to the job description or group expectations. If the practice hires an NPP fresh out of school, the group will need to establish training and have the new hire work more closely with physicians. If, on the other hand, an NP has 10 years of experience in an ICU, or a PA has worked in the ED for the past five years, a higher level of autonomy can be granted sooner. However, NPPs with established backgrounds are almost as rare as experienced hospitalists (see “Integrating NPPs Into HM Practice,” p. 38).

Inevitably, there will be changes in the interactions between patients and the hospitalists, as both physicians and NPPs become more comfortable with the other’s practice style, as well as each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

MD-to-NPP Ratio Varies

The practice structure and optimal mix of NPPs to MDs is something that will be specific to the hospitalist group. “We don’t really have good studies on this subject,” Buser says. “I usually get worried when we exceed two NPPs to one MD.”

Others disagree. Dr. Parekh, who works in an academic center, says his group has been successful having one MD work with as many as three NPPs. At the other end, Dr. Wilson says his 10 years of experience suggest 1:1 is the most efficient ratio.

However, all of them agree that having one NPP work with more than one physician is not sustainable. The NPP will be less familiar with each doctor’s practice style, what kind of information they need, and how things should be presented. If two or more hospitalists share an NPP, there can be internal friction over division of the NPP’s time, as well as extending the time before the MDs have a good feel for the NPP’s strengths and weaknesses.

In the final analysis, the HM group has to look at the amount and type of work available. In some cases, it will make financial and clinical sense to bring on an NPP. Under other circumstances, an FTE hospitalist is the best fit.

“Sustainability, quality, and efficiency are the drivers for NPP/MD teams. Increasing pressure to offset program costs is not,” Dr. Wilson says. “You do it because it helps sustain the program, helps with recruiting, and effects your efficiency.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- Medical Group Management Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine. State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. 2010. Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.

In 2004, the hospitalist group at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor faced a manpower problem: In a refrain common to hospitalist groups around the country, changes in duty-hour regulations were making it harder for medical residents to continue to provide inpatient coverage at the same levels as before.

Addressing the issue was difficult for the HM group and hospital administrators; they were going to need a significant number of new providers, and qualified physicians were in short supply. To address these issues, the HM group chose to add nonphysician providers (NPP) to their service.

“NPPs had worked at UM for a long time in other areas,” says Vikas Parekh, MD, SFHM, associate director of hospitalist management. “We had just created a new service that was hiring new people and thought NPPs would help in providing services.”

Hiring NPPs helped solve the University of Michigan’s problem, and the tactic has helped solve manpower issues at numerous HM groups around the country. But deciding whether your HM group should hire physicians, NPPs—usually nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs)—or some combination of the two will not be easy. It is a complex decision, one that requires following state-level licensing and practice laws as well as local hospital bylaws and federal and private insurance payment rules. Such decisions also mean HM group directors need to keep in mind case mixes and the personalities of the physicians in the practice.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution,” says Mitchell Wilson, MD, SFHM, corporate medical director for Eagle Hospital Physicians in Atlanta. “Not all environments are well-suited to NPP practice. Even when it is, you can’t just throw an NPP into the mix on their own with the expectation they will be successful.”

Whether it’s covering admissions, streamlining discharges, or working as an integral part of a care team, NPPs can be the solution expanding HM groups are looking for.

“Our physicians depend on NPPs to help them complete patient care in a more efficient manner and work to enhance continuity of care,” says Mary Whitehead, RN, APRN-BC, FNP, of Hospital Medicine Associates in Fort Worth, Texas. “We lower physician rounding time so patients are seen sooner and tests are requested sooner. In addition, the patients really appreciate the extra time we can spend with them.”

Trained, Licensed, Available

NPs must be registered nurses with clinical experience before they can enroll in an advanced degree program, which usually results in a master’s degree or doctorate. Generally, a state board of nursing, or a state board jointly with the state medical board, regulates NPs.

PAs are trained in more of a traditional medical model. They have a variable education level all the way up to a PhD, although more states are requiring at least a master’s degree. Practice and other legal parameters most often come under the authority of state medical boards.

NPPs can provide additional medical expertise to patients, says Ryan Genzink, PA, a physician assistant with Hospitalists of Western Michigan in Grand Rapids and the American Academy of Physician Assistants’ medical liaison to SHM. “One of the challenges faced by physicians is that they often have to be in two places at once,” he says. “There is a recognition that teams provide better care for complicated patients.”

NPPs generally practice under the supervision of a physician hospitalist. Some states allow a greater degree of independence for NPs. However, most NPs and PAs are required to have a practice agreement outlining their responsibilities and the amount of oversight required (see Table 1, p. 39). There is no such thing as a “fire and forget” NPP.

“The practice needs to thoroughly understand the legal environment early in the process,” says John Nelson, MD, MHM, hospitalist director at Bellevue (Wash.) Medical Center, partner in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants, and SHM cofounder. “NPPs are not a ‘hospitalist lite’ that can function entirely like a hospitalist.”

Hospital bylaws, which can vary greatly by city, county, or state, are another important consideration before you hire an NPP.

“In some areas, NPPs may not be able to practice in the ICU,” Dr. Wilson says. “In others, the physician may be required to see the patient instead of consulting with the NPP. The idiosyncrasies of the individual hospital’s bylaws may impact the efficiency of the NPP/MD team.”

Physician Characteristics

Environmental variables—namely, the personality of the physicians within the practice—should be considered before you head down the NPP path. It makes little practical or financial sense to spend the time and effort of hiring an NPP if the physicians still insist on doing all the work.

“[It’s] one of the most significant factors in successfully integrating an NPP program,” Dr. Wilson says. “Will [physicians] be able to tolerate some degree of uncertainty when letting others see their patients? Are they open to adapting to different practice styles? The thing we see most often in practices that use NPPs to their advantage is the recognition that there is an important role for the nonphysician at the bedside.”

Some physicians hesitate to work with NPPs, while others welcome the extra help and unique experience NPPs offer. Experts agree that forcing NPPs on a physician is not a good idea. They also agree that, especially when beginning a new program, group directors should let physicians who are interested in working with NPPs take the lead. As NPP use in the group matures, many of those who were at first unwilling can decide that there is a place for NPPs in their practice.

Case Mix Is Key

The types and kinds of patient seen might limit the use of NPPs in hospitalist practice. “Our experience is that acuity and complexity of the care, especially as it relates to diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making, makes it difficult for NPPs to function independently,” Dr. Parekh says.

Dr. Wilson agrees. “Depending on the specific attributes of the setting, a service with both high-complexity and high-acuity patients may be a more challenging environment to realize the efficiencies of NPPs,” he says. “There is a relationship between complexity, acuity, and physician involvement.”

Even so, a continuum of NPP use in HM practice is achievable. For example, as a patient improves, an NPP might be able to take on a larger role in treatment by participating in discharge planning. In more acute patients, the NPP can save valuable physician time by coordinating with consultants, staying on top of treatments, and consolidating clinically important data for the physician.

Many Models in Use

Historically, the widespread use of alternative providers began in 2004 as a result of the changes to resident duty-hours. The restrictions created a workforce gap, which led to a large number of new positions in hospitals nationwide. Many of HM’s early adopters essentially went with what they knew.

“We work in teams where the physician, NPP, and nurse see a group of patients similar in function to an attending, resident, and RN,” Genzink says. “We see ‘our’ patients in a collaborative fashion.”

There are other models that have proven successful in the correct setting. Some HM groups use specialist NPPs to cover specific clinical areas, such as orthopedics or oncology. This not only develops a cadre of providers with excellent understanding of their patients, but it also frees up physician time for more acute and complicated patients.

“Our physicians depend on us helping them get patient care completed more efficiently, so that length of stay is acceptable, and to enhance continuity of care,” says Whitehead, the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners’ liaison to SHM. “Having an NPP visit the patient daily, documenting progress, greatly enhances communications between physicians and consultants.”

Other groups have NPPs specialize by function—for example, they cover all admissions or work mainly with discharging a patient. Some groups have the physician see the patient on admission, work out a care plan, then turn over management to the NPP. Many agree that most NPPs are best utilized by having them cover specific shifts, such as overnight call or on a swing shift, to help during peak demand.

Monetary and Time Commitments

The financial impact of NPPs on a hospitalist practice depends on many factors. Groups will need to look not only at the salary and benefit costs associated with the position, but also how best to fit that person into the billing system.

Salary and benefit comparisons are fairly straightforward: The State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data, produced by SHM and the Medical Group Management Association, shows median total compensation for adult hospitalists at $215,000 per year; NPP compensation is around $87,000.1

The general cost of benefits (health insurance, retirement, etc.) is fairly typical throughout a hospitalist practice, so there should be little difference between a new FTE hospitalist or NPP. Other considerations, including office space and support staff, would be roughly the same if the group hired a physician. The cost of continuing education and malpractice insurance likely will be less with an NPP, but it is best to check before making a new hire.

After the outgo has been established, the next step is to look at the differences in reimbursement for NPPs vs. physicians. Here, again, the math gets tricky. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pay NPPs at 85% of the physician rate for a specific diagnosis. However, if there is direct physician involvement, the claim can be filed as “shared billing” and reimbursed at 100%.

For some hospitalist practices, adding NPPs is an easy decision to make. Dr. Parekh says his group already has policies in place that require a physician to see the patient every day. In that case, no extra physician time is necessary, so shared billing makes sense. Other hospitals’ bylaws might have similar requirements.

For practices in which the NPP is able to work with less oversight, it might be better to bill at 85% rather than use the physician time to meet shared-billing criteria. Even in practices with greater NPP autonomy, such variables as case mix and patient acuity might enter into the equation. If the patient is sick enough that the physician is involved for a significant amount of time, then shared billing probably is best.

Experts say group directors and hiring managers should look carefully at contracts with private insurers, too. There most likely will be considerable variation in how each plan handles NPP claims.

Managing performance expectations can have an impact on the successful use of NPPs in a hospitalist practice. Setting realistic goals and groupwide understanding of what the NPPs’ roles will be is crucial. The practice should look at the work that needs to be done and decide if that work provides a genuinely valuable role for an NPP.

Hire for Need, Not Desperation

“The mistake I see most often is hiring an NPP because a practice is desperate for help,” says Martin Buser, MPH, FACHE, a partner in Hospitalist Management Resources, LLC, in San Diego. “Smart practices are looking at NPPs, evaluating where they do the most good, and then setting out their role and expectations based on these needs and the practice environment.”

Hiring mistakes can be compounded if the NPP is not a good match to the job description or group expectations. If the practice hires an NPP fresh out of school, the group will need to establish training and have the new hire work more closely with physicians. If, on the other hand, an NP has 10 years of experience in an ICU, or a PA has worked in the ED for the past five years, a higher level of autonomy can be granted sooner. However, NPPs with established backgrounds are almost as rare as experienced hospitalists (see “Integrating NPPs Into HM Practice,” p. 38).

Inevitably, there will be changes in the interactions between patients and the hospitalists, as both physicians and NPPs become more comfortable with the other’s practice style, as well as each other’s strengths and weaknesses.

MD-to-NPP Ratio Varies

The practice structure and optimal mix of NPPs to MDs is something that will be specific to the hospitalist group. “We don’t really have good studies on this subject,” Buser says. “I usually get worried when we exceed two NPPs to one MD.”

Others disagree. Dr. Parekh, who works in an academic center, says his group has been successful having one MD work with as many as three NPPs. At the other end, Dr. Wilson says his 10 years of experience suggest 1:1 is the most efficient ratio.

However, all of them agree that having one NPP work with more than one physician is not sustainable. The NPP will be less familiar with each doctor’s practice style, what kind of information they need, and how things should be presented. If two or more hospitalists share an NPP, there can be internal friction over division of the NPP’s time, as well as extending the time before the MDs have a good feel for the NPP’s strengths and weaknesses.

In the final analysis, the HM group has to look at the amount and type of work available. In some cases, it will make financial and clinical sense to bring on an NPP. Under other circumstances, an FTE hospitalist is the best fit.

“Sustainability, quality, and efficiency are the drivers for NPP/MD teams. Increasing pressure to offset program costs is not,” Dr. Wilson says. “You do it because it helps sustain the program, helps with recruiting, and effects your efficiency.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- Medical Group Management Association and the Society of Hospital Medicine. State of Hospital Medicine: 2010 Report Based on 2009 Data. 2010. Philadelphia and Englewood, Colo.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions & The Hospitalist

Hospitalist Neal Axon, MD, first became aware of an important change in his hospital’s policies last year while attending to an elderly patient the morning after admission to the community hospital where he works part time.

“This new form appeared in the chart requesting a urinalysis for my patient, who’d had a Foley catheter placed,” says Dr. Axon, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “I didn’t know why, so I asked. I was told that it was now necessary to document that there was no UTI present on admission.” He asked the charge nurse, “So what do I do now that the catheter has been in place for 12 hours and has colonization without a true infection?”

The next thing he heard: silence.

The new form Dr. Axon encountered was an outgrowth of the requirements of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which ordered Medicare to withhold additional hospital payments for hospital-acquired complications (HAC) developed during a hospital stay. One result of the new rule is that much of a hospital’s response to these initiatives has been placed in the hands of the hospitalist. From accurate documentation of complications already present on admission (POA), to confirming that guidelines for treatment are being followed, to taking the lead on review of staff practices and education, hospitalists are in a position to have a wide-ranging impact on patient care and the financial health of their institutions.

Congress Pushes Reforms

In order for Medicare to not provide a reimbursement, an HAC has to be high-cost and/or high-volume, result in the assignment of the case to a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and “could reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines,” says Barry Straube, MD, chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “CMS was to implement a process where we would not pay the hospitals additional money for these complications.”

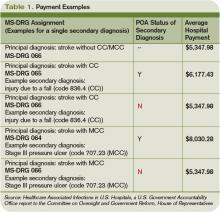

The new rules mean Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of Medicare Severity Diagnostic-Related Groups (MS-DRG), which better reflect the complexity of a patient’s illness. The biggest change was a three-tiered payment schedule: a base level for the diagnosis, a second level adding money to reflect the presence of comorbidities and complications, and a third for major complications and comorbidities (see Table 1, p. 31).

“Instituting HACs means that hospitals would no longer receive the comorbidity and complication payments if the only reason a case qualified for higher payment was the HAC,” Dr. Straube explains. “We did carve out a POA exception for those conditions that were acquired outside of the hospital. HACs only impact additional payments; the hospitals are still paid for the diagnosis that resulted in the hospital admission.”

CMS also identifies three “never events” it won’t reimburse for (see “A Brief History of Never Events,” p. 35): performing the wrong procedure, performing a procedure on the wrong body part, and performing a procedure on the wrong patient. “Neither hospitals nor physicians that are involved in such egregious situations would be paid,” Dr. Straube says.

Preventability: Subject of Controversy

The big questions surrounding HACs: Could they reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines? How preventable are HACs? Who decides if a complication is preventable, and therefore payment for services is withheld?

They’re concerns that are widespread among physicians, hospital administrators, and regulators alike.

“The legislation required the conditions to be ‘reasonably preventable’ using established clinical guidelines,” Dr. Straube says. “We did not have to show 100% prevention. In an imperfect world, they might still take place occasionally, but with good medical care, almost all of these are preventable in this day and age.”

For CMS, the preventable conditions are an either/or situation: Either they existed prior to admission and are subject to payment, or they did not exist at admission and additional payment for the complication will not be made. “HACs do not currently consider a patient’s individual risk for complications,” says Jennifer Meddings, MD, MSc, clinical lecturer and health researcher in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know the best strategies to prevent complications in ideal patients, and these are reflected in the HACs. In real life, many of our patients just don’t fit into the guidelines for many reasons—and you have to individualize care.”

Dr. Meddings points to DVT as a prime example. For a certain number of inpatients, the guidelines can be followed to perfection. In other patients (e.g., those with kidney conditions), previous reactions to a medication or an individual’s predisposition to clotting might interfere with treatment. However, CMS doesn’t allow appeals of nonpayment decisions for HACs based on individual circumstances.

Some experts think the rigidness of the payment policy forces physicians to treat patients exactly to guidelines. Even then, payment could be declined if an HAC develops.

“One of the points of most discussion is how preventable some of these are, particularly when choosing those you are no longer going to pay for,” Dr. Meddings says. “Many of the complications currently under review have patients that are at higher risk than others. How much our prevention strategies can alleviate or reduce the risk varies widely among patients.”

Impact on HM Practice

Many of the preventable conditions outlined by CMS do not directly affect hospitalist payment. However, hospitalists often find themselves responsible for properly documenting admission and care.

“The rule changes regarding payment for HACs are only related to hospital payments, and to date, most physicians, including hospitalists, are not directly at financial risk,” says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine in the divisions of Health Care Policy Research and General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. “Although hospitalists have no financial skin in the game, there are plenty of reasons they would take an interest in addressing HACs in their hospital. In particular, they are often seen as the ‘go-to’ group for quality improvement in their hospitals.”

For example, some HM groups have been active in working with teams of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers to address local policies and procedures on prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) and DVT.

“This has certainly necessitated a team approach,” says Shaun Frost, MD, FHM, an SHM board member and regional medical director for Cogent Healthcare in St. Paul, Minn. “For many of the HACs that apply to our population of patients, the hospitalist alone cannot be expected to solely execute effective quality improvements. It takes a team effort in that regard, and one that includes many different disciplines.”

The Cogent-affiliated hospitalist group at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia formed a task force to address issues with catheter-associated UTI. One initiative focused on educating all providers involved in the proper care of the catheters and similar interventions. A secondary focus of the project was an inventory of current practices and procedures.

“It was discovered that we did not have an automatic stop order for Foley catheters, so in some situations, they were likely being left in longer than needed while nursing [staff] tried to contact a physician,” Dr. Frost explains. “We created standardized order sets that include criteria for continuing the catheter. Once the criteria are no longer applicable, nursing will be able to discontinue it.”

Although CMS has only recently turned the spotlight on HACs and never events, hospitalists have been heavily involved in the patient-safety arena for years. “It is not a new phenomenon that hospitalists work for healthcare delivery and healthcare system improvement,” Dr. Meddings says.

Hospital administration at Temple University Hospital recognized the HM group’s quality-improvement (QI) work, and has “specifically charged us with spreading the work we have done in patient safety to the entire house,” Dr. Frost says. “That speaks to the administration’s opinion of the power of the HM program to assist with institution-wide QI initiatives.”

Documentation Is Key

Beyond applying proven methods to avoid HACs, hospitalists can make a difference through documentation. If the hospitalist notes all conditions when the patient first presents to the hospital, additional comorbidity and complication payments should be made.

“The part that probably has the greatest impact on the day-to-day practice of a hospitalist is the increased importance of documentation throughout the hospital episode,” Dr. Meddings says. “If complications are occurring and they are not present in the chart, the coders may not recognize that it has occurred and will not know to include it in the bill. This can have an adverse impact on the hospital and its finances.”

Documentation issues can impact hospital payment in several ways:

- Hospitals might receive additional payment by default if certain HACs are described incorrectly or without sufficient detail (e.g., receiving overpayment because the physician did not indicate a UTI was in fact a catheter-associated UTI);

- As more attention is invested in documenting all conditions POA, hospitals might be coding more comorbidities overall than previously, which also will generate additional payment for hospitals as any POA condition is eligible for increased payment; and

- Hospitals might lose payment when admitting providers fail to adequately document the condition as POA (e.g., a pre-existing decubitus ulcer not detected until the second day of the hospital stay).

The descriptions to be used in coding are very detailed. UTIs, for example, have one code to document the POA assessment, another code to show that a UTI occurred, and a third code to indicate it was catheter-associated. Each code requires appropriate documentation in the chart (see Table 1, above).

The impact hospitalists have on care and payment is not the same across the HAC spectrum. For instance, documenting the presence of pressure ulcers might be easier than distinguishing colonization from infection in those admitted with in-dwelling urinary catheters. Others, such as DVT or vascular catheter-associated infections, are rarely POA unless they are part of the admitting diagnosis.

“This new focus on hospital-acquired conditions may work to the patient’s benefit,” Dr. Meddings says. “The inclusion of pressure ulcers has led to increased attention to skin exams on admission and preventive measures during hospitalizations. In the past, skin exams upon admission may have been given a lower priority, but that has changed.”

Dr. Meddings is concerned that the new rules could force the shifting of resources to areas where the hospital could lose money. If, when, and how many changes will actually take place is still up in the air. “Resource shifting is a concern whenever there is any sort of pay-for-performance attention directed toward one particular complication,” she says. “To balance this, many of the strategies hospitals used to prevent complications are not specific to just the diagnosis that is covered by the HAC.”

Dr. Meddings also hopes the new focus on preventable conditions will have a “halo effect” in the healthcare community. For instance, CMS mandating DVT prevention following orthopedic operations will, hopefully, result in a greater awareness of the problem in other susceptible patients.

POA Indicators

Since hospitalists often perform the initial patient history, physical, and other admission work, they are in the best position to find and document POA indicators (see Table 2, p. below). Proper notes on such things as UTIs present and the state of skin integrity are an important part of making sure the hospital is paid correctly for the care it provides.

Education on the specific definition of each potential HAC is required to help physicians avoid overtreatment of certain conditions, especially UTIs. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines all UTIs as symptomatic. Therefore, the screening of all admitted patients, regardless of symptoms, is wasteful and unlikely to help the hospital’s bottom line.

“If you start screening everyone that comes through the door so you don’t miss any pre-existing UTIs, you are going to find a lot of asymptomatic colonization,” Dr. Wald says. “You are also going to spend a lot of money and time on studies and possibly treatments that may not yield many true infections. It is important that physicians know the definition of these HACs to help avoid needless interventions.”

Minimal Loss

Many hospital administrators and physicians were worried when the HAC program was first announced. Much of the stress and concern, however, seems to have dissipated. CMS estimated the HAC program would save Medicare $21 million in fiscal year 2009. Others, such as Peter McNair and colleagues writing in Health Affairs, suggest the actual impact is closer to $1.1 million.1 The CMS-projected impact of the HAC provision in fiscal-year 2009 was $21 million, out of more than $100 billion in payments.

“I think the HACs will not have a major impact because of the way payments are made,” says internist Robert Berenson, MD, a fellow at the Urban Institute in Washington, D.C., who has studied Medicare policy issues extensively, and for two years was in charge of Medicare payment policies at the Health Care Finance Administration, the precursor to CMS. “Patients who have HACs often have another comorbidity that would kick them into a higher payment category regardless of the presence of a hospital-acquired complication. In the end, it is probably more symbolic and unlikely to make a major dent in hospital income—at least at this point.”

Another limitation to CMS nonpayment for HACs is the issue of deciding which conditions are truly preventable. Dr. Berenson questions the ability of the current system to identify many additional complications for which this approach will be feasible.

“CMS has laid out its strategy, suggesting that we should be able to continue increasing the number of conditions for which providers would be paid differently based on quality,” he says. “Many observers question whether there will ever be measurement tools that are robust enough, and there will be a wide agreement on the preventability of enough conditions that this initiative will go very far.”

Although hospitalists might not face a direct financial risk, they still have their hospitals’ best interest—and their reputations—on the line. “Hospitalists care about preventing complications,” Dr. Wald says. “We are very engaged in working with our hospitals to improve care, maximize quality, and minimize cost.” TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance medical writer based in Indiana.

Reference

- McNair PD, Luft HS, Bindman AB. Medicare’s policy not to pay for treating hospital-acquired conditions: the impact. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1485-1493.

TOP IMAGE SOURCE: KAREEM RIZKHALLA/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

Hospitalist Neal Axon, MD, first became aware of an important change in his hospital’s policies last year while attending to an elderly patient the morning after admission to the community hospital where he works part time.

“This new form appeared in the chart requesting a urinalysis for my patient, who’d had a Foley catheter placed,” says Dr. Axon, an assistant professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. “I didn’t know why, so I asked. I was told that it was now necessary to document that there was no UTI present on admission.” He asked the charge nurse, “So what do I do now that the catheter has been in place for 12 hours and has colonization without a true infection?”

The next thing he heard: silence.

The new form Dr. Axon encountered was an outgrowth of the requirements of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005, which ordered Medicare to withhold additional hospital payments for hospital-acquired complications (HAC) developed during a hospital stay. One result of the new rule is that much of a hospital’s response to these initiatives has been placed in the hands of the hospitalist. From accurate documentation of complications already present on admission (POA), to confirming that guidelines for treatment are being followed, to taking the lead on review of staff practices and education, hospitalists are in a position to have a wide-ranging impact on patient care and the financial health of their institutions.

Congress Pushes Reforms

In order for Medicare to not provide a reimbursement, an HAC has to be high-cost and/or high-volume, result in the assignment of the case to a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis, and “could reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines,” says Barry Straube, MD, chief medical officer and director of the Office of Clinical Standards and Quality at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). “CMS was to implement a process where we would not pay the hospitals additional money for these complications.”

The new rules mean Medicare pays hospitals on the basis of Medicare Severity Diagnostic-Related Groups (MS-DRG), which better reflect the complexity of a patient’s illness. The biggest change was a three-tiered payment schedule: a base level for the diagnosis, a second level adding money to reflect the presence of comorbidities and complications, and a third for major complications and comorbidities (see Table 1, p. 31).

“Instituting HACs means that hospitals would no longer receive the comorbidity and complication payments if the only reason a case qualified for higher payment was the HAC,” Dr. Straube explains. “We did carve out a POA exception for those conditions that were acquired outside of the hospital. HACs only impact additional payments; the hospitals are still paid for the diagnosis that resulted in the hospital admission.”

CMS also identifies three “never events” it won’t reimburse for (see “A Brief History of Never Events,” p. 35): performing the wrong procedure, performing a procedure on the wrong body part, and performing a procedure on the wrong patient. “Neither hospitals nor physicians that are involved in such egregious situations would be paid,” Dr. Straube says.

Preventability: Subject of Controversy

The big questions surrounding HACs: Could they reasonably be prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines? How preventable are HACs? Who decides if a complication is preventable, and therefore payment for services is withheld?

They’re concerns that are widespread among physicians, hospital administrators, and regulators alike.

“The legislation required the conditions to be ‘reasonably preventable’ using established clinical guidelines,” Dr. Straube says. “We did not have to show 100% prevention. In an imperfect world, they might still take place occasionally, but with good medical care, almost all of these are preventable in this day and age.”

For CMS, the preventable conditions are an either/or situation: Either they existed prior to admission and are subject to payment, or they did not exist at admission and additional payment for the complication will not be made. “HACs do not currently consider a patient’s individual risk for complications,” says Jennifer Meddings, MD, MSc, clinical lecturer and health researcher in the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. “We know the best strategies to prevent complications in ideal patients, and these are reflected in the HACs. In real life, many of our patients just don’t fit into the guidelines for many reasons—and you have to individualize care.”

Dr. Meddings points to DVT as a prime example. For a certain number of inpatients, the guidelines can be followed to perfection. In other patients (e.g., those with kidney conditions), previous reactions to a medication or an individual’s predisposition to clotting might interfere with treatment. However, CMS doesn’t allow appeals of nonpayment decisions for HACs based on individual circumstances.

Some experts think the rigidness of the payment policy forces physicians to treat patients exactly to guidelines. Even then, payment could be declined if an HAC develops.

“One of the points of most discussion is how preventable some of these are, particularly when choosing those you are no longer going to pay for,” Dr. Meddings says. “Many of the complications currently under review have patients that are at higher risk than others. How much our prevention strategies can alleviate or reduce the risk varies widely among patients.”

Impact on HM Practice

Many of the preventable conditions outlined by CMS do not directly affect hospitalist payment. However, hospitalists often find themselves responsible for properly documenting admission and care.

“The rule changes regarding payment for HACs are only related to hospital payments, and to date, most physicians, including hospitalists, are not directly at financial risk,” says Heidi Wald, MD, MSPH, hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine in the divisions of Health Care Policy Research and General Internal Medicine at the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine. “Although hospitalists have no financial skin in the game, there are plenty of reasons they would take an interest in addressing HACs in their hospital. In particular, they are often seen as the ‘go-to’ group for quality improvement in their hospitals.”

For example, some HM groups have been active in working with teams of physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers to address local policies and procedures on prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs) and DVT.

“This has certainly necessitated a team approach,” says Shaun Frost, MD, FHM, an SHM board member and regional medical director for Cogent Healthcare in St. Paul, Minn. “For many of the HACs that apply to our population of patients, the hospitalist alone cannot be expected to solely execute effective quality improvements. It takes a team effort in that regard, and one that includes many different disciplines.”

The Cogent-affiliated hospitalist group at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia formed a task force to address issues with catheter-associated UTI. One initiative focused on educating all providers involved in the proper care of the catheters and similar interventions. A secondary focus of the project was an inventory of current practices and procedures.

“It was discovered that we did not have an automatic stop order for Foley catheters, so in some situations, they were likely being left in longer than needed while nursing [staff] tried to contact a physician,” Dr. Frost explains. “We created standardized order sets that include criteria for continuing the catheter. Once the criteria are no longer applicable, nursing will be able to discontinue it.”

Although CMS has only recently turned the spotlight on HACs and never events, hospitalists have been heavily involved in the patient-safety arena for years. “It is not a new phenomenon that hospitalists work for healthcare delivery and healthcare system improvement,” Dr. Meddings says.

Hospital administration at Temple University Hospital recognized the HM group’s quality-improvement (QI) work, and has “specifically charged us with spreading the work we have done in patient safety to the entire house,” Dr. Frost says. “That speaks to the administration’s opinion of the power of the HM program to assist with institution-wide QI initiatives.”

Documentation Is Key

Beyond applying proven methods to avoid HACs, hospitalists can make a difference through documentation. If the hospitalist notes all conditions when the patient first presents to the hospital, additional comorbidity and complication payments should be made.

“The part that probably has the greatest impact on the day-to-day practice of a hospitalist is the increased importance of documentation throughout the hospital episode,” Dr. Meddings says. “If complications are occurring and they are not present in the chart, the coders may not recognize that it has occurred and will not know to include it in the bill. This can have an adverse impact on the hospital and its finances.”

Documentation issues can impact hospital payment in several ways:

- Hospitals might receive additional payment by default if certain HACs are described incorrectly or without sufficient detail (e.g., receiving overpayment because the physician did not indicate a UTI was in fact a catheter-associated UTI);

- As more attention is invested in documenting all conditions POA, hospitals might be coding more comorbidities overall than previously, which also will generate additional payment for hospitals as any POA condition is eligible for increased payment; and

- Hospitals might lose payment when admitting providers fail to adequately document the condition as POA (e.g., a pre-existing decubitus ulcer not detected until the second day of the hospital stay).

The descriptions to be used in coding are very detailed. UTIs, for example, have one code to document the POA assessment, another code to show that a UTI occurred, and a third code to indicate it was catheter-associated. Each code requires appropriate documentation in the chart (see Table 1, above).

The impact hospitalists have on care and payment is not the same across the HAC spectrum. For instance, documenting the presence of pressure ulcers might be easier than distinguishing colonization from infection in those admitted with in-dwelling urinary catheters. Others, such as DVT or vascular catheter-associated infections, are rarely POA unless they are part of the admitting diagnosis.

“This new focus on hospital-acquired conditions may work to the patient’s benefit,” Dr. Meddings says. “The inclusion of pressure ulcers has led to increased attention to skin exams on admission and preventive measures during hospitalizations. In the past, skin exams upon admission may have been given a lower priority, but that has changed.”

Dr. Meddings is concerned that the new rules could force the shifting of resources to areas where the hospital could lose money. If, when, and how many changes will actually take place is still up in the air. “Resource shifting is a concern whenever there is any sort of pay-for-performance attention directed toward one particular complication,” she says. “To balance this, many of the strategies hospitals used to prevent complications are not specific to just the diagnosis that is covered by the HAC.”

Dr. Meddings also hopes the new focus on preventable conditions will have a “halo effect” in the healthcare community. For instance, CMS mandating DVT prevention following orthopedic operations will, hopefully, result in a greater awareness of the problem in other susceptible patients.

POA Indicators

Since hospitalists often perform the initial patient history, physical, and other admission work, they are in the best position to find and document POA indicators (see Table 2, p. below). Proper notes on such things as UTIs present and the state of skin integrity are an important part of making sure the hospital is paid correctly for the care it provides.

Education on the specific definition of each potential HAC is required to help physicians avoid overtreatment of certain conditions, especially UTIs. For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines all UTIs as symptomatic. Therefore, the screening of all admitted patients, regardless of symptoms, is wasteful and unlikely to help the hospital’s bottom line.

“If you start screening everyone that comes through the door so you don’t miss any pre-existing UTIs, you are going to find a lot of asymptomatic colonization,” Dr. Wald says. “You are also going to spend a lot of money and time on studies and possibly treatments that may not yield many true infections. It is important that physicians know the definition of these HACs to help avoid needless interventions.”

Minimal Loss