User login

As flu season descends on North America, hospitalists from Boston to the San Francisco Bay are concerned about what might happen when normal seasonal influenza hospital admissions are added to new cases of the novel influenza A (H1N1) virus.

Perhaps the most basic, still-unanswered question is how the addition of novel H1N1 virus affects the severity of the upcoming flu season. From April 15 to July 24 of this year, states reported 43,771 confirmed and probable cases of novel H1N1 infection. Of the cases reported, 5,011 people were hospitalized and 302 died. After July 24, the CDC stopped counting novel H1N1 as separate flu cases.

“We are expecting increased illness during the regular flu season, because we think both the novel H1N1 and seasonal flu strains will cause illness in the population,” says Artealia Gilliard, a spokesperson for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta. “The biggest problem we are having is that there is no set number we can give for planning purposes. We can’t say go out and prepare for X percent more illness, because there is no scientifically sound way to arrive at a number.”

Another concern is that little guidance is available on how severe the novel virus will be. Gilliard notes that the World Health Organization (WHO) gave novel H1N1 the pandemic designation because of its ease of transmission, not the severity of the disease. Although the CDC expects more illness, it is not yet clear how many people will be made sick enough to be cared for by a hospitalist.

“The epidemiology of this illness and prevention issues related to this newly emerging virus are still being studied, making it very difficult to anticipate the staffing needs for the upcoming flu season,” says Irina Schiopescu, MD, a hospitalist and infectious-disease specialist at Roane Medical Center in Harriman, Tenn. “Hospitalists will be among the many front-line healthcare workers who provide direct, bedside clinical care to patients with suspected or confirmed H1N1 influenza.”

Most of the nation’s hospitals spent the summer preparing for another pandemic. Hospitalists have assessed their needs, too, and HM programs are focusing on a diverse set of concerns: prevention education for hospital-based employees, patient management updates, and expected personnel shortages.

“We have been planning for the worst but hoping for the best,” says Julia Wright, MD, FHM, head of the section of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals in Madison and a member of Team Hospitalist. “Our task group for the upcoming flu season includes all critical-care services, nursing, supply-chain management, and human resources, as well as other appropriate specialties, such as infection control.”

Another Wild Card

How well the vaccination campaign works will have an impact on the incidence of novel H1N1 influenza. Some have expressed concerns about compliance issues in the community, as individuals will need an extra flu shot in addition to the yearly vaccination for seasonal flu strains. The concerns could double if current ongoing clinical trials suggest that two vaccine administrations are required for full protection from the H1N1 virus.

There also is concern about the availability of vaccines, especially in the early stages. As of early September, Robin Robinson, PhD, director of the Biological Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), announced that manufacturing problems would mean only 45 million doses would be available by Oct. 15, compared with the 120 million doses originally projected. However, HHS says the 195 million doses the U.S. government ordered should be available by the December deadline for final delivery.1

Nevertheless, physicians should expect large-scale vaccination initiatives at their hospitals this fall. Additionally, hospitals are expected to require that healthcare workers, including hospitalists, receive their shots during the first wave of inoculations. “At our facility, we have the potential to give 100,000 or more vaccinations over a very short period of time,” says Patty Skoglund, RN, administrative director for disaster preparedness at Scripps Health in San Diego. “This is in addition to supporting vaccination efforts in the community.”

Southern Hemisphere

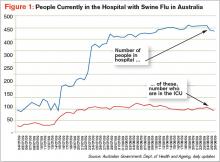

The Southern Hemisphere is wrapping up its flu season, and often, experiences south of the equator are a harbinger of what might come in the Northern Hemisphere. So far, the WHO says the Southern Hemisphere’s flu season has been characterized by normal respiratory disease numbers. The impact and severity is still being

evaluated, but it appeared only slightly worse than normal in most places. Hospitals did see increased admissions (see Figure 1, p. 5) requiring respiratory critical care.2 Yet the lack of firm guidance has made planning difficult for HM groups and the U.S. hospitals they work in.

It will be important for hospitalists to stay up to date with a potentially developing situation, especially in the early stages of the flu season. Many current CDC guidelines for treatment, prevention, and control are in interim stages, with more guidance to come as the science firms up. (see “Vaccination Priorities,” right)

“As we get closer to the flu season, we should be able to make specific suggestions and get a better idea of the probable incidence,” says Gilliard. “Novel H1N1 has caused significant illness outside of the regular season. When the temperature changes, will the incidence increase or decrease? We have to get more experience before we will know.”

Information Hotline

Hospitals are working to ensure that there are open lines of communication with key personnel, an important first step in infectious-disease control. It will be necessary to facilitate the timely dispersal of new information on guidelines and treatment considerations to multiple audiences throughout the hospital as they are released. In addition, flu incidence and severity updates will be vital.

“It is imperative that physicians know what is going on in their community and beyond,” says Dr. Schiopescu. “The CDC and the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) are resources for treatment guidelines and information on the spread and severity of both the novel H1N1 and seasonal virus strains. Closer to home, both state and local health boards can help with a more focused view of what is happening in the community.”

Patient placement will be another concern for hospitalists in the event of a widespread outbreak. The current CDC patient care guidelines say that all patients with confirmed or suspected H1N1 infection must be isolated. Although they can be scattered in rooms throughout the hospital, it is strongly suggested that they be placed together as a cohort, if possible.

“Our hospital is looking into designating special areas of the hospital to accept influenza patients,” Dr. Wright says. “We can then give the staff special training on treatment and prevention, give better access to materials and supplies in a single location, and also minimize the time lost to physicians going from one patient to another.”

Staffing Concerns

One of the biggest concerns to HM groups is keeping their own areas of the hospital properly staffed. In addition to the possibility of higher acuity and admissions affecting coverage needs, most experts are suggesting employee absentee rates upward of 40%. To further complicate the picture, interim CDC guidelines say healthcare workers should be off work 24 hours after a fever subsides or seven days, whichever is longer. This guidance, however, could change as the CDC obtains and reviews more information.

“We are a small group of only four physicians,” says Dr. Schiopescu, whose HM group works a six-day on, six-day off schedule for about 85 encounters per week at her 50-bed hospital. “We may need to work additional shifts and be available to be called in early, should the need arise. We have also done some cross-training so that community physicians can help if needed. At worst, we can pull resources from our sister hospitals in the system.”

—Irina Schiopescu, MD, infectious-disease specialist, Roane Medical Center, Harriman, Tenn.

Some hospitals have been able to flex up and increase staffing levels before the season begins. “In addition to adding three full-time equivalent staff, we have actively looked for other specialties, such as internal medicine or family practice, that have the proper skill sets should the need arise,” says Dr. Wright, whose program covers 75% of the 471 medical beds at UW Hospital. “We have also developed a set of protocols to streamline treatment of these patients, no matter who may be taking care of them.”

Scripps is surveying its employees to identify family and other outside obligations that could lead to call-outs and staffing shortages. Hospital administrators expect that the information will identify physicians who might not be able to come to work. The hospital also implemented systems that will allow them to bring in extra people—and get them deployed quickly—from such state and federal support resources as the Public Health Service and the National Disaster Medical System staffs.

“Balancing the needs of the various areas will be tricky at times,” Dr. Wright says. “We have to move people around while making sure we are not leaving one area dangerously understaffed.”

Education Imperative

Educating health workers is of the utmost importance before and during the flu season. A wide range of staff training will be required: reinforcing cough etiquette and hand-washing requirements through completely new procedures. This will be important for patient treatment and patient safety, two areas that intersect in hospitalists every day. In addition, this flu season will require a heightened level of personal responsibility from health workers. “Teaching needs are adding to the burden,” says Skoglund, the administrative director at Scripps. “Unfortunately, it is not as simple as sending out a memo to the staff and affiliated physicians.”

Training is a moving target, at least initially. Clinical employees will need to be trained on treatment and prevention guidelines as they are released, with special emphasis on keeping up with changes as the season progresses and lessons are learned.

“In the past, the CDC suggested using a N-95 respirator for all patients with novel H1N1,” Dr. Schiopescu says. “Currently, that has changed to approved use of a regular surgical mask, unless performing intubation or bronchoscopy.”

Despite the best efforts of the CDC, WHO, and other health organizations, there is no real clear idea of what to expect during the next flu season.

“What is known is that the hospitalist will be on the front lines, involved in the treatment of the sickest patients,” Dr. Wright says. TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance writer based in Indiana.

Image Source: MAMMAMAART/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

References

- Officials lower expectations for size of first novel flu vaccine deliveries. Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy Web site. Available at: www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/swineflu/news/aug1409vaccine.html. Accessed Aug. 20, 2009.

- Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: update 61. WHO Web site. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/2009_08_12/en/index.html. Accessed Aug. 24, 2009.

As flu season descends on North America, hospitalists from Boston to the San Francisco Bay are concerned about what might happen when normal seasonal influenza hospital admissions are added to new cases of the novel influenza A (H1N1) virus.

Perhaps the most basic, still-unanswered question is how the addition of novel H1N1 virus affects the severity of the upcoming flu season. From April 15 to July 24 of this year, states reported 43,771 confirmed and probable cases of novel H1N1 infection. Of the cases reported, 5,011 people were hospitalized and 302 died. After July 24, the CDC stopped counting novel H1N1 as separate flu cases.

“We are expecting increased illness during the regular flu season, because we think both the novel H1N1 and seasonal flu strains will cause illness in the population,” says Artealia Gilliard, a spokesperson for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta. “The biggest problem we are having is that there is no set number we can give for planning purposes. We can’t say go out and prepare for X percent more illness, because there is no scientifically sound way to arrive at a number.”

Another concern is that little guidance is available on how severe the novel virus will be. Gilliard notes that the World Health Organization (WHO) gave novel H1N1 the pandemic designation because of its ease of transmission, not the severity of the disease. Although the CDC expects more illness, it is not yet clear how many people will be made sick enough to be cared for by a hospitalist.

“The epidemiology of this illness and prevention issues related to this newly emerging virus are still being studied, making it very difficult to anticipate the staffing needs for the upcoming flu season,” says Irina Schiopescu, MD, a hospitalist and infectious-disease specialist at Roane Medical Center in Harriman, Tenn. “Hospitalists will be among the many front-line healthcare workers who provide direct, bedside clinical care to patients with suspected or confirmed H1N1 influenza.”

Most of the nation’s hospitals spent the summer preparing for another pandemic. Hospitalists have assessed their needs, too, and HM programs are focusing on a diverse set of concerns: prevention education for hospital-based employees, patient management updates, and expected personnel shortages.

“We have been planning for the worst but hoping for the best,” says Julia Wright, MD, FHM, head of the section of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals in Madison and a member of Team Hospitalist. “Our task group for the upcoming flu season includes all critical-care services, nursing, supply-chain management, and human resources, as well as other appropriate specialties, such as infection control.”

Another Wild Card

How well the vaccination campaign works will have an impact on the incidence of novel H1N1 influenza. Some have expressed concerns about compliance issues in the community, as individuals will need an extra flu shot in addition to the yearly vaccination for seasonal flu strains. The concerns could double if current ongoing clinical trials suggest that two vaccine administrations are required for full protection from the H1N1 virus.

There also is concern about the availability of vaccines, especially in the early stages. As of early September, Robin Robinson, PhD, director of the Biological Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), announced that manufacturing problems would mean only 45 million doses would be available by Oct. 15, compared with the 120 million doses originally projected. However, HHS says the 195 million doses the U.S. government ordered should be available by the December deadline for final delivery.1

Nevertheless, physicians should expect large-scale vaccination initiatives at their hospitals this fall. Additionally, hospitals are expected to require that healthcare workers, including hospitalists, receive their shots during the first wave of inoculations. “At our facility, we have the potential to give 100,000 or more vaccinations over a very short period of time,” says Patty Skoglund, RN, administrative director for disaster preparedness at Scripps Health in San Diego. “This is in addition to supporting vaccination efforts in the community.”

Southern Hemisphere

The Southern Hemisphere is wrapping up its flu season, and often, experiences south of the equator are a harbinger of what might come in the Northern Hemisphere. So far, the WHO says the Southern Hemisphere’s flu season has been characterized by normal respiratory disease numbers. The impact and severity is still being

evaluated, but it appeared only slightly worse than normal in most places. Hospitals did see increased admissions (see Figure 1, p. 5) requiring respiratory critical care.2 Yet the lack of firm guidance has made planning difficult for HM groups and the U.S. hospitals they work in.

It will be important for hospitalists to stay up to date with a potentially developing situation, especially in the early stages of the flu season. Many current CDC guidelines for treatment, prevention, and control are in interim stages, with more guidance to come as the science firms up. (see “Vaccination Priorities,” right)

“As we get closer to the flu season, we should be able to make specific suggestions and get a better idea of the probable incidence,” says Gilliard. “Novel H1N1 has caused significant illness outside of the regular season. When the temperature changes, will the incidence increase or decrease? We have to get more experience before we will know.”

Information Hotline

Hospitals are working to ensure that there are open lines of communication with key personnel, an important first step in infectious-disease control. It will be necessary to facilitate the timely dispersal of new information on guidelines and treatment considerations to multiple audiences throughout the hospital as they are released. In addition, flu incidence and severity updates will be vital.

“It is imperative that physicians know what is going on in their community and beyond,” says Dr. Schiopescu. “The CDC and the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) are resources for treatment guidelines and information on the spread and severity of both the novel H1N1 and seasonal virus strains. Closer to home, both state and local health boards can help with a more focused view of what is happening in the community.”

Patient placement will be another concern for hospitalists in the event of a widespread outbreak. The current CDC patient care guidelines say that all patients with confirmed or suspected H1N1 infection must be isolated. Although they can be scattered in rooms throughout the hospital, it is strongly suggested that they be placed together as a cohort, if possible.

“Our hospital is looking into designating special areas of the hospital to accept influenza patients,” Dr. Wright says. “We can then give the staff special training on treatment and prevention, give better access to materials and supplies in a single location, and also minimize the time lost to physicians going from one patient to another.”

Staffing Concerns

One of the biggest concerns to HM groups is keeping their own areas of the hospital properly staffed. In addition to the possibility of higher acuity and admissions affecting coverage needs, most experts are suggesting employee absentee rates upward of 40%. To further complicate the picture, interim CDC guidelines say healthcare workers should be off work 24 hours after a fever subsides or seven days, whichever is longer. This guidance, however, could change as the CDC obtains and reviews more information.

“We are a small group of only four physicians,” says Dr. Schiopescu, whose HM group works a six-day on, six-day off schedule for about 85 encounters per week at her 50-bed hospital. “We may need to work additional shifts and be available to be called in early, should the need arise. We have also done some cross-training so that community physicians can help if needed. At worst, we can pull resources from our sister hospitals in the system.”

—Irina Schiopescu, MD, infectious-disease specialist, Roane Medical Center, Harriman, Tenn.

Some hospitals have been able to flex up and increase staffing levels before the season begins. “In addition to adding three full-time equivalent staff, we have actively looked for other specialties, such as internal medicine or family practice, that have the proper skill sets should the need arise,” says Dr. Wright, whose program covers 75% of the 471 medical beds at UW Hospital. “We have also developed a set of protocols to streamline treatment of these patients, no matter who may be taking care of them.”

Scripps is surveying its employees to identify family and other outside obligations that could lead to call-outs and staffing shortages. Hospital administrators expect that the information will identify physicians who might not be able to come to work. The hospital also implemented systems that will allow them to bring in extra people—and get them deployed quickly—from such state and federal support resources as the Public Health Service and the National Disaster Medical System staffs.

“Balancing the needs of the various areas will be tricky at times,” Dr. Wright says. “We have to move people around while making sure we are not leaving one area dangerously understaffed.”

Education Imperative

Educating health workers is of the utmost importance before and during the flu season. A wide range of staff training will be required: reinforcing cough etiquette and hand-washing requirements through completely new procedures. This will be important for patient treatment and patient safety, two areas that intersect in hospitalists every day. In addition, this flu season will require a heightened level of personal responsibility from health workers. “Teaching needs are adding to the burden,” says Skoglund, the administrative director at Scripps. “Unfortunately, it is not as simple as sending out a memo to the staff and affiliated physicians.”

Training is a moving target, at least initially. Clinical employees will need to be trained on treatment and prevention guidelines as they are released, with special emphasis on keeping up with changes as the season progresses and lessons are learned.

“In the past, the CDC suggested using a N-95 respirator for all patients with novel H1N1,” Dr. Schiopescu says. “Currently, that has changed to approved use of a regular surgical mask, unless performing intubation or bronchoscopy.”

Despite the best efforts of the CDC, WHO, and other health organizations, there is no real clear idea of what to expect during the next flu season.

“What is known is that the hospitalist will be on the front lines, involved in the treatment of the sickest patients,” Dr. Wright says. TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance writer based in Indiana.

Image Source: MAMMAMAART/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

References

- Officials lower expectations for size of first novel flu vaccine deliveries. Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy Web site. Available at: www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/swineflu/news/aug1409vaccine.html. Accessed Aug. 20, 2009.

- Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: update 61. WHO Web site. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/2009_08_12/en/index.html. Accessed Aug. 24, 2009.

As flu season descends on North America, hospitalists from Boston to the San Francisco Bay are concerned about what might happen when normal seasonal influenza hospital admissions are added to new cases of the novel influenza A (H1N1) virus.

Perhaps the most basic, still-unanswered question is how the addition of novel H1N1 virus affects the severity of the upcoming flu season. From April 15 to July 24 of this year, states reported 43,771 confirmed and probable cases of novel H1N1 infection. Of the cases reported, 5,011 people were hospitalized and 302 died. After July 24, the CDC stopped counting novel H1N1 as separate flu cases.

“We are expecting increased illness during the regular flu season, because we think both the novel H1N1 and seasonal flu strains will cause illness in the population,” says Artealia Gilliard, a spokesperson for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta. “The biggest problem we are having is that there is no set number we can give for planning purposes. We can’t say go out and prepare for X percent more illness, because there is no scientifically sound way to arrive at a number.”

Another concern is that little guidance is available on how severe the novel virus will be. Gilliard notes that the World Health Organization (WHO) gave novel H1N1 the pandemic designation because of its ease of transmission, not the severity of the disease. Although the CDC expects more illness, it is not yet clear how many people will be made sick enough to be cared for by a hospitalist.

“The epidemiology of this illness and prevention issues related to this newly emerging virus are still being studied, making it very difficult to anticipate the staffing needs for the upcoming flu season,” says Irina Schiopescu, MD, a hospitalist and infectious-disease specialist at Roane Medical Center in Harriman, Tenn. “Hospitalists will be among the many front-line healthcare workers who provide direct, bedside clinical care to patients with suspected or confirmed H1N1 influenza.”

Most of the nation’s hospitals spent the summer preparing for another pandemic. Hospitalists have assessed their needs, too, and HM programs are focusing on a diverse set of concerns: prevention education for hospital-based employees, patient management updates, and expected personnel shortages.

“We have been planning for the worst but hoping for the best,” says Julia Wright, MD, FHM, head of the section of hospital medicine at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals in Madison and a member of Team Hospitalist. “Our task group for the upcoming flu season includes all critical-care services, nursing, supply-chain management, and human resources, as well as other appropriate specialties, such as infection control.”

Another Wild Card

How well the vaccination campaign works will have an impact on the incidence of novel H1N1 influenza. Some have expressed concerns about compliance issues in the community, as individuals will need an extra flu shot in addition to the yearly vaccination for seasonal flu strains. The concerns could double if current ongoing clinical trials suggest that two vaccine administrations are required for full protection from the H1N1 virus.

There also is concern about the availability of vaccines, especially in the early stages. As of early September, Robin Robinson, PhD, director of the Biological Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), announced that manufacturing problems would mean only 45 million doses would be available by Oct. 15, compared with the 120 million doses originally projected. However, HHS says the 195 million doses the U.S. government ordered should be available by the December deadline for final delivery.1

Nevertheless, physicians should expect large-scale vaccination initiatives at their hospitals this fall. Additionally, hospitals are expected to require that healthcare workers, including hospitalists, receive their shots during the first wave of inoculations. “At our facility, we have the potential to give 100,000 or more vaccinations over a very short period of time,” says Patty Skoglund, RN, administrative director for disaster preparedness at Scripps Health in San Diego. “This is in addition to supporting vaccination efforts in the community.”

Southern Hemisphere

The Southern Hemisphere is wrapping up its flu season, and often, experiences south of the equator are a harbinger of what might come in the Northern Hemisphere. So far, the WHO says the Southern Hemisphere’s flu season has been characterized by normal respiratory disease numbers. The impact and severity is still being

evaluated, but it appeared only slightly worse than normal in most places. Hospitals did see increased admissions (see Figure 1, p. 5) requiring respiratory critical care.2 Yet the lack of firm guidance has made planning difficult for HM groups and the U.S. hospitals they work in.

It will be important for hospitalists to stay up to date with a potentially developing situation, especially in the early stages of the flu season. Many current CDC guidelines for treatment, prevention, and control are in interim stages, with more guidance to come as the science firms up. (see “Vaccination Priorities,” right)

“As we get closer to the flu season, we should be able to make specific suggestions and get a better idea of the probable incidence,” says Gilliard. “Novel H1N1 has caused significant illness outside of the regular season. When the temperature changes, will the incidence increase or decrease? We have to get more experience before we will know.”

Information Hotline

Hospitals are working to ensure that there are open lines of communication with key personnel, an important first step in infectious-disease control. It will be necessary to facilitate the timely dispersal of new information on guidelines and treatment considerations to multiple audiences throughout the hospital as they are released. In addition, flu incidence and severity updates will be vital.

“It is imperative that physicians know what is going on in their community and beyond,” says Dr. Schiopescu. “The CDC and the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) are resources for treatment guidelines and information on the spread and severity of both the novel H1N1 and seasonal virus strains. Closer to home, both state and local health boards can help with a more focused view of what is happening in the community.”

Patient placement will be another concern for hospitalists in the event of a widespread outbreak. The current CDC patient care guidelines say that all patients with confirmed or suspected H1N1 infection must be isolated. Although they can be scattered in rooms throughout the hospital, it is strongly suggested that they be placed together as a cohort, if possible.

“Our hospital is looking into designating special areas of the hospital to accept influenza patients,” Dr. Wright says. “We can then give the staff special training on treatment and prevention, give better access to materials and supplies in a single location, and also minimize the time lost to physicians going from one patient to another.”

Staffing Concerns

One of the biggest concerns to HM groups is keeping their own areas of the hospital properly staffed. In addition to the possibility of higher acuity and admissions affecting coverage needs, most experts are suggesting employee absentee rates upward of 40%. To further complicate the picture, interim CDC guidelines say healthcare workers should be off work 24 hours after a fever subsides or seven days, whichever is longer. This guidance, however, could change as the CDC obtains and reviews more information.

“We are a small group of only four physicians,” says Dr. Schiopescu, whose HM group works a six-day on, six-day off schedule for about 85 encounters per week at her 50-bed hospital. “We may need to work additional shifts and be available to be called in early, should the need arise. We have also done some cross-training so that community physicians can help if needed. At worst, we can pull resources from our sister hospitals in the system.”

—Irina Schiopescu, MD, infectious-disease specialist, Roane Medical Center, Harriman, Tenn.

Some hospitals have been able to flex up and increase staffing levels before the season begins. “In addition to adding three full-time equivalent staff, we have actively looked for other specialties, such as internal medicine or family practice, that have the proper skill sets should the need arise,” says Dr. Wright, whose program covers 75% of the 471 medical beds at UW Hospital. “We have also developed a set of protocols to streamline treatment of these patients, no matter who may be taking care of them.”

Scripps is surveying its employees to identify family and other outside obligations that could lead to call-outs and staffing shortages. Hospital administrators expect that the information will identify physicians who might not be able to come to work. The hospital also implemented systems that will allow them to bring in extra people—and get them deployed quickly—from such state and federal support resources as the Public Health Service and the National Disaster Medical System staffs.

“Balancing the needs of the various areas will be tricky at times,” Dr. Wright says. “We have to move people around while making sure we are not leaving one area dangerously understaffed.”

Education Imperative

Educating health workers is of the utmost importance before and during the flu season. A wide range of staff training will be required: reinforcing cough etiquette and hand-washing requirements through completely new procedures. This will be important for patient treatment and patient safety, two areas that intersect in hospitalists every day. In addition, this flu season will require a heightened level of personal responsibility from health workers. “Teaching needs are adding to the burden,” says Skoglund, the administrative director at Scripps. “Unfortunately, it is not as simple as sending out a memo to the staff and affiliated physicians.”

Training is a moving target, at least initially. Clinical employees will need to be trained on treatment and prevention guidelines as they are released, with special emphasis on keeping up with changes as the season progresses and lessons are learned.

“In the past, the CDC suggested using a N-95 respirator for all patients with novel H1N1,” Dr. Schiopescu says. “Currently, that has changed to approved use of a regular surgical mask, unless performing intubation or bronchoscopy.”

Despite the best efforts of the CDC, WHO, and other health organizations, there is no real clear idea of what to expect during the next flu season.

“What is known is that the hospitalist will be on the front lines, involved in the treatment of the sickest patients,” Dr. Wright says. TH

Kurt Ullman is a freelance writer based in Indiana.

Image Source: MAMMAMAART/ISTOCKPHOTO.COM

References

- Officials lower expectations for size of first novel flu vaccine deliveries. Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy Web site. Available at: www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/swineflu/news/aug1409vaccine.html. Accessed Aug. 20, 2009.

- Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: update 61. WHO Web site. Available at: www.who.int/csr/don/2009_08_12/en/index.html. Accessed Aug. 24, 2009.