User login

Economic Impact of Enoxaparin in Stroke

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which encompasses both deep‐vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major health problem in the United States and worldwide. It represents one of the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality with an estimated 300,000 VTE‐related deaths,1 and 300,000‐600,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually.2 Hospitalization for medical illness is associated with a similar proportion of VTE cases as hospitalization for surgery.3 Several groups of medical patients have been shown to be at an increased risk of VTE, including those with cancer, severe respiratory disease, acute infectious illness, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and acute ischemic stroke.47 Ischemic stroke patients represent approximately 4.6% of medical patients at high risk of VTE in US hospitals.8 The incidence of DVT in such patients has been reported to be as high as 75%9 and PE has been reported to be responsible for up to 25% of early deaths after stroke.10

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of unfractionated heparin (UFH) or a low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) in the prevention of VTE in stroke patients, and have demonstrated that LMWHs are at least as effective as UFH.1114 The open‐label, randomized Prevention of VTE after acute ischemic stroke with LMWH and UFH (PREVAIL) trial demonstrated that in patients with acute ischemic stroke, prophylaxis for 10 days with the LMWH enoxaparin reduces the risk of VTE by 43% compared with UFH (10.2% vs 18.1%, respectively; relative risk = 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.44‐0.76; P = 0.0001) without increasing the incidence of overall bleeding events (7.9% vs 8.1%, respectively; P = 0.83), or the composite of symptomatic intracranial and major extracranial hemorrhage (1% in each group; P = 0.23). There was, however, a slight but significant increase in major extracranial hemorrhage alone with enoxaparin (1% vs 0%; P = 0.015).14 Evidence‐based guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) provide recommendations for appropriate thromboprophylaxis regimens for patients at risk of VTE.15 Thromboprophylaxis with UFH, LMWH, and, more recently, fondaparinux is recommended for medical patients admitted to hospital with congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease, or those who are confined to bed and have one or more additional risk factors, including active cancer, previous VTE, or acute neurologic disease.15 Similarly, in the Eighth ACCP Clinical Practice Guidelines, low‐dose UFH or LMWH are recommended for VTE prevention in patients with ischemic stroke who have restricted mobility.16

VTE is also associated with a substantial economic burden on the healthcare system, costing an estimated $1.5 billion annually in the United States.17 Thromboprophylaxis has been shown to be a cost‐effective strategy in hospitalized medical patients. Prophylaxis with a LMWH has been shown to be more cost‐effective than UFH in these patients.1821

However, despite the clinical and economic benefits, prophylaxis is still commonly underused in medical patients.22, 23 In surgical patients, the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) focuses on reducing surgical complications, and has endorsed 2 measures: VTE‐1, relating to the proportion of patients for whom VTE prophylaxis is ordered; and VTE‐2, relating to those who receive the recommended regimen (

The objective of the current study was to determine the economic impact, in terms of hospital costs, of enoxaparin compared with UFH for VTE prophylaxis after acute ischemic stroke. A decision‐analytic model was constructed using data from the PREVAIL study and historical inpatient data from a multi‐hospital database.

METHODS

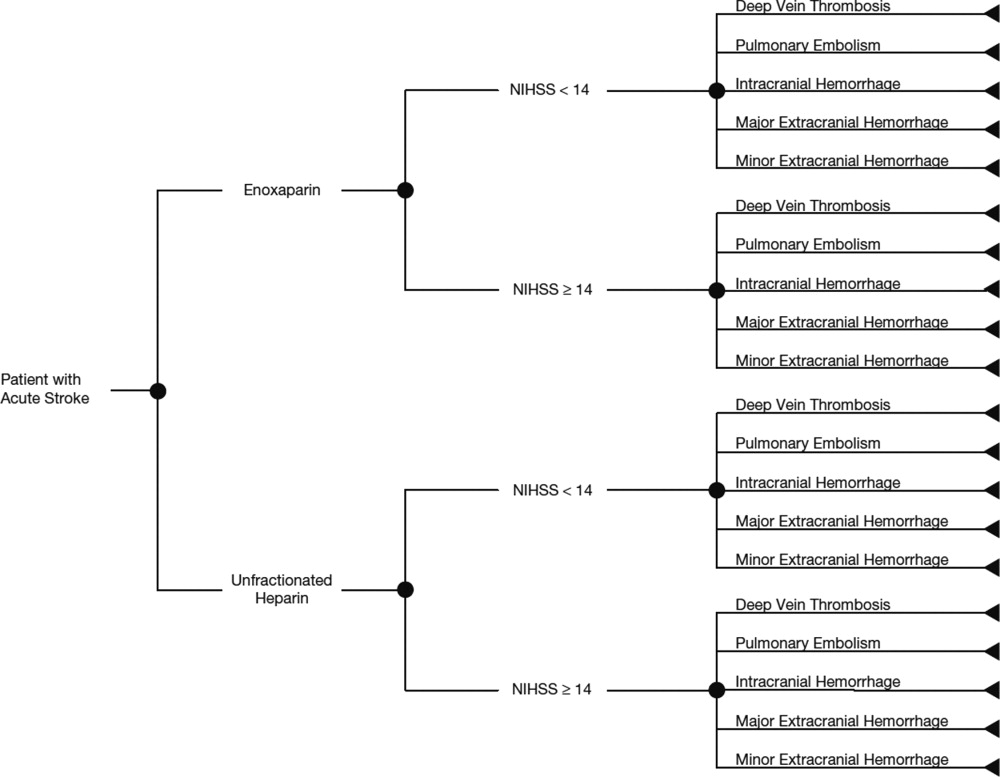

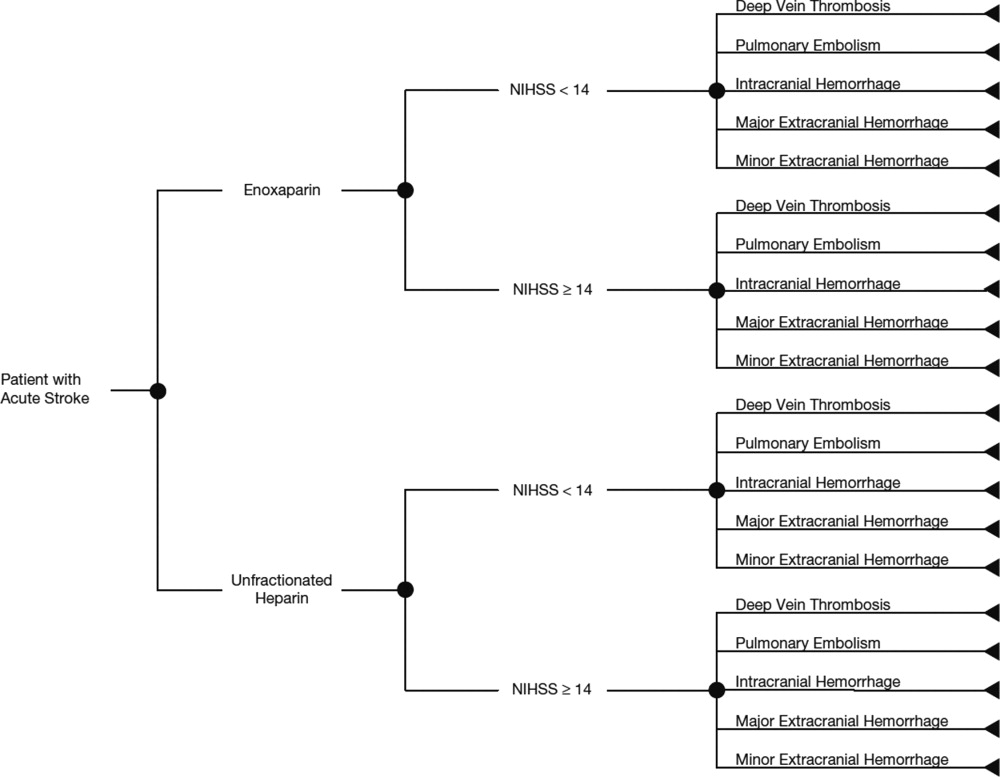

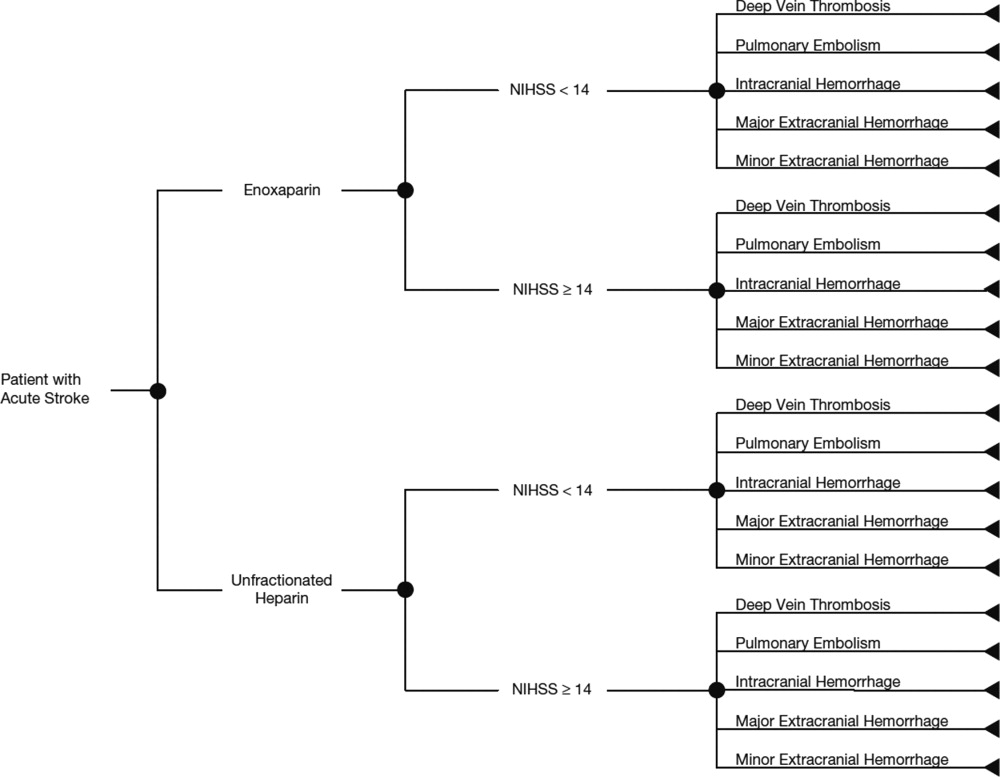

In this study, the cost implications, from the hospital perspective, of VTE prophylaxis with enoxaparin or UFH in patients with acute ischemic stroke, were determined using a decision‐analytic model in TreeAge Pro Suite (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA). The decision‐tree was based on 3 stages: (a) whether patients received enoxaparin or UFH; (b) how patients were classified according to their National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) classification scores (<14 or 14); and (c) which clinical event each patient experienced, as defined per the PREVAIL trial (DVT, PE, intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor extracranial hemorrhage) (Figure 1). The time horizon for the model was established at 90 days to mirror the length of follow‐up in the PREVAIL trial.

Total hospital costs were calculated based on clinical event rates (from the PREVAIL trial) and the costs of each clinical event, which were calculated separately according to the descriptions below, and then inserted into the decision‐analytic model. The clinical event rates were calculated from the efficacy and safety endpoints collected in the PREVAIL trial, and included VTE events (DVT and PE) and bleeding events (intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor extracranial hemorrhage). Details of the patient population, eligibility criteria, and treatment regimen have previously been published in full elsewhere.14, 27

The costs of clinical events during hospitalization were estimated using a multivariate cost‐evaluation model, based on mean hospital costs for the events in the (Premier Inc., Charlotte, NC, USA) multi‐hospital database, one of the largest US hospital clinical and economic databases. The data are received from over 600 hospitals, representing all geographical areas of the United States, a broad range of bed sizes, teaching and non‐teaching, and urban and rural facilities. This database contains detailed US inpatient care records of principal and secondary diagnoses, inpatient procedures, administered laboratory tests, dispensed drugs, and demographic information. The evaluation of hospital cost for each type of clinical event was conducted by i3 Innovus (Ingenix, Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, USA). Total hospital costs were cumulative from all events, so if patients experienced multiple clinical events, the costs of the events were additive. The cost for stroke treatment and management was not included because it is an inclusion criterion of the PREVAIL trial and, thus, all patients in the trial have such costs.

Default drug costs were taken from the 2008 US wholesalers' acquisition cost data. The default dosing schedule is based on information extracted from the PREVAIL trial: enoxaparin 40 mg (once‐daily) and UFH 5000 U (twice‐daily) for 10 days each ($25.97 and $2.97, respectively). A drug‐administration fee was added for each dose of either enoxaparin or UFH ($10 for each).19

The estimated hospital cost of clinical events, along with drug costs, were inserted into the decision‐analytic model in TreeAge Pro Suite to estimate the cost per discharge from the hospital perspective in patients with ischemic stroke receiving VTE prophylaxis with enoxaparin or UFH. An additional analysis was performed to investigate the costs and cost differences in patients with less severe stroke (NIHSS scores <14) and more severe stroke (NIHSS scores 14).

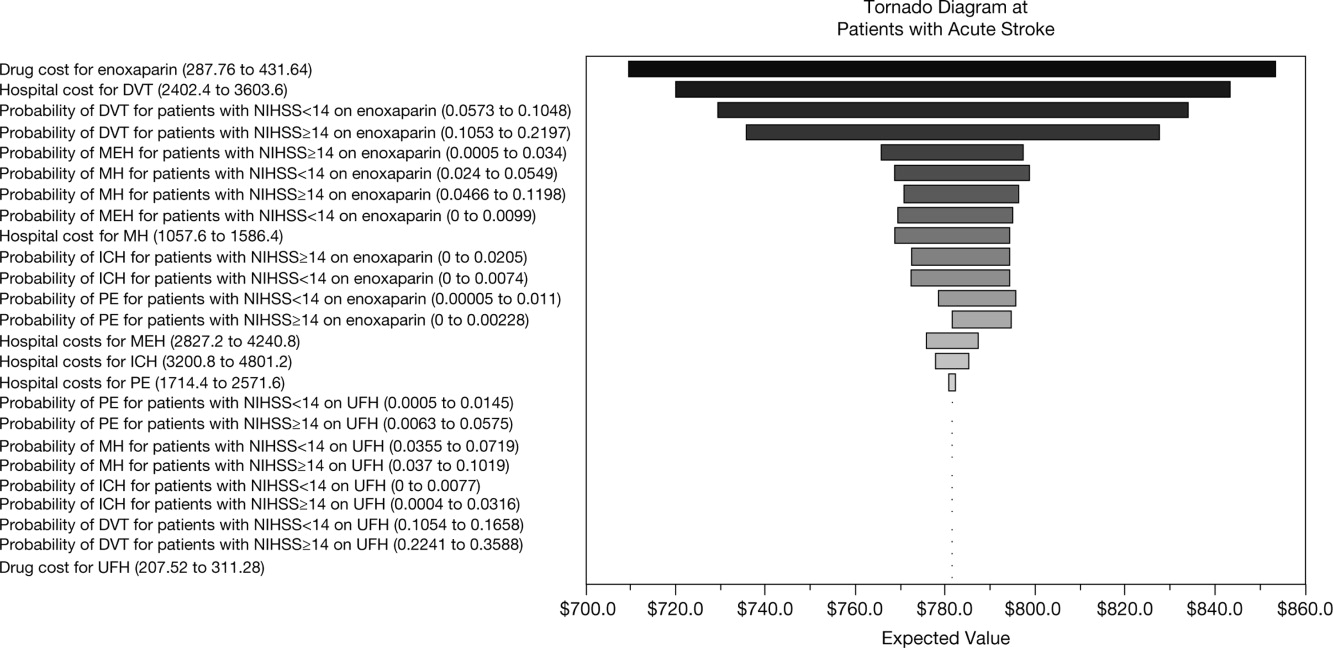

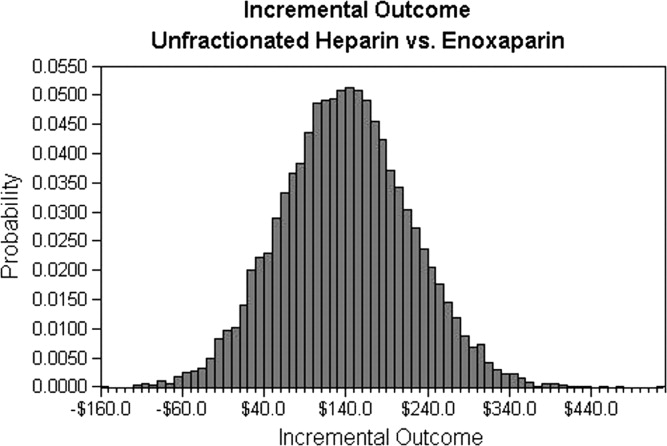

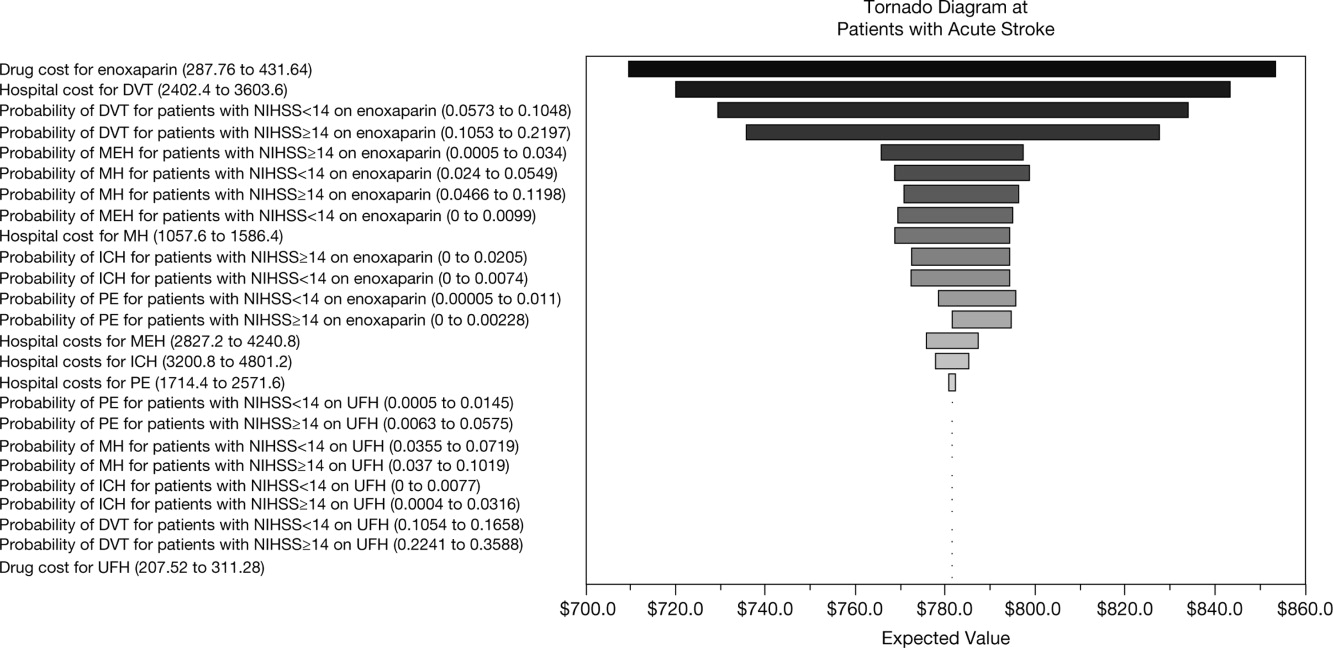

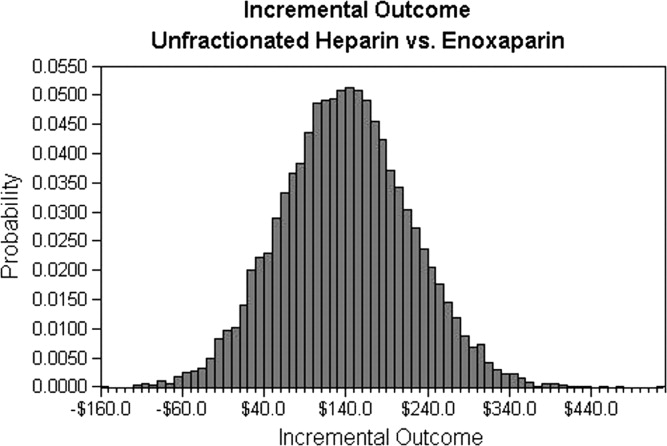

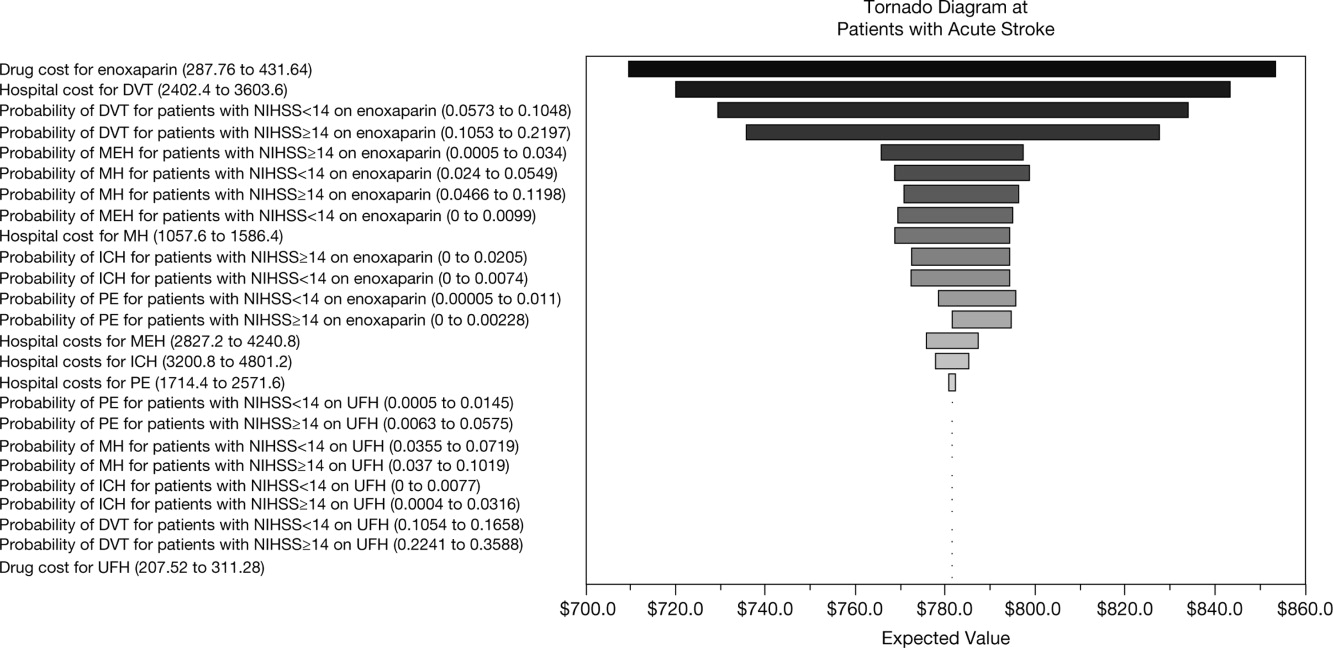

Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the impact of varying the cost inputs on the total hospital cost of each treatment arm by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, and the robustness in the difference in costs between the enoxaparin and UFH groups. Univariate (via tornado diagram in TreeAge Pro Suite) and multivariate (via Monte Carlo simulation in TreeAge Pro Suite) analyses were performed. For the univariate analysis, each clinical event cost was adjusted individually, increasing or decreasing by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30% and 40% while other parameters remained unchanged. For the Monte Carlo simulation (TreeAge Pro Suite), all the parameters were simultaneously varied in a random fashion, within a range of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40% over 10,000 trials. The simulation adopted a gamma distribution assumption for input sampling for cost parameters and a beta distribution for the event probability parameters. The confidence intervals for the probability parameters were obtained from the PREVAIL trial. The differences between the enoxaparin and UFH treatment groups were plotted in a graph against the variation in costs of each clinical event.

RESULTS

The clinical VTE and bleeding event rates as collected from the PREVAIL trial are shown in Table 1. The hospital costs per clinical event are shown in Table 2. The most costly clinical event from the hospital perspective was intracranial hemorrhage at $4001, followed by major extracranial hemorrhage at $3534. The costs of DVT and PE were $3003 and $2143, respectively.

| Event Rate | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Enoxaparin (NIHSS <14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.081 | 0.05730.1048 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.002 | 0.000050.011 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0031 | 00.0074 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0.0047 | 00.0099 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0372 | 0.0240.0549 |

| Enoxaparin (NIHSS 14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.1625 | 0.10530.2197 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 00 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0086 | 00.0205 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0.0172 | 0.04660.1198 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0776 | 0.04660.1198 |

| UFH (NIHSS <14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.1356 | 0.10540.1658 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.004 | 0.00050.0145 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0032 | 00.0077 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 00 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0514 | 0.03550.0719 |

| UFH (NIHSS 14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.2914 | 0.22410.3588 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.0229 | 0.00630.0575 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.016 | 0.00040.0316 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 00 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.064 | 0.0370.1019 |

| Event | Cost per Event ($)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Likeliest | Minimum | Maximum | |

| |||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 3,003 | 2,402 | 3,604 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2,143 | 1,714 | 2,572 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4,001 | 3,201 | 4,801 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 3,534 | 2,827 | 4,241 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 1,322 | 1,058 | 1,586 |

| Enoxaparin cost per dose | 26 | 21 | 31 |

| Unfractionated heparin cost per dose | 3 | 2 | 4 |

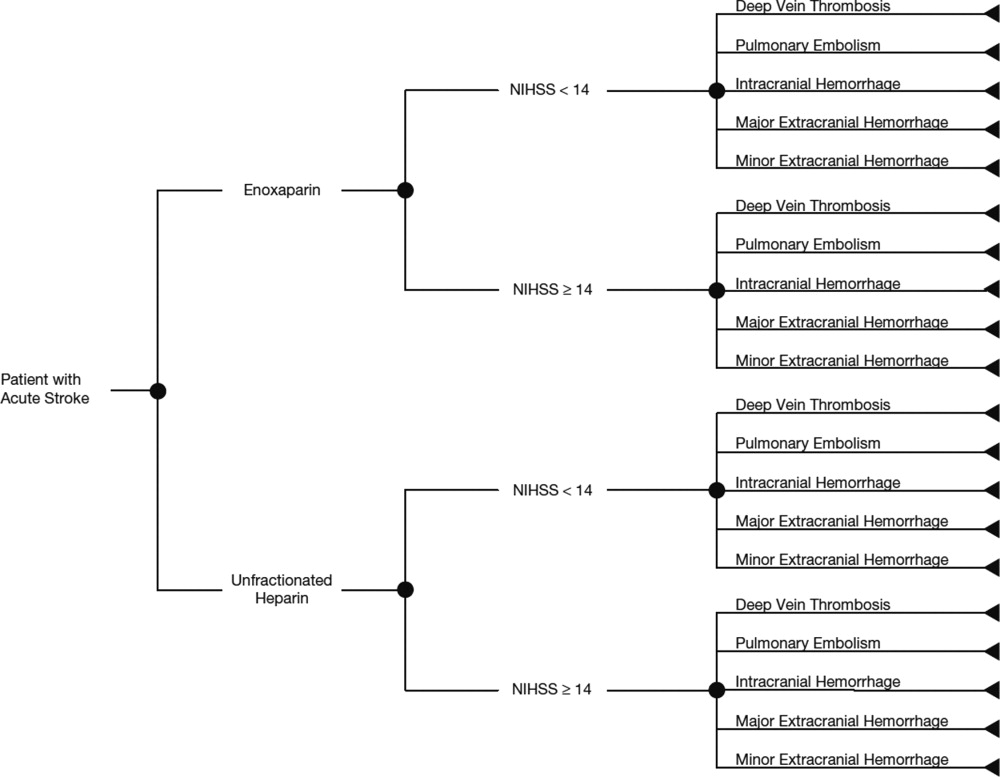

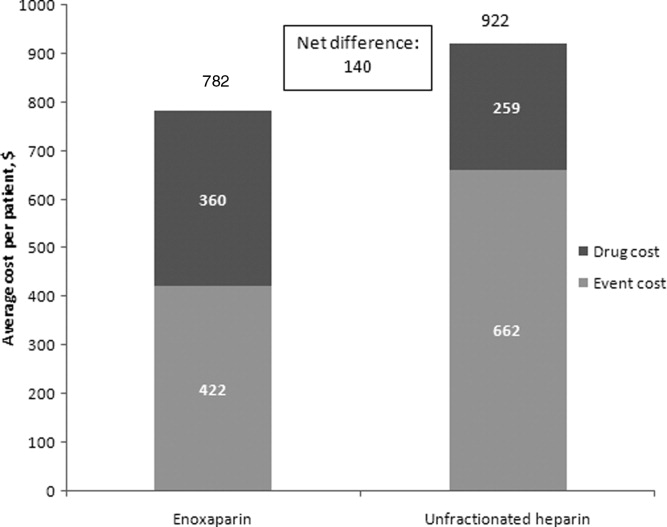

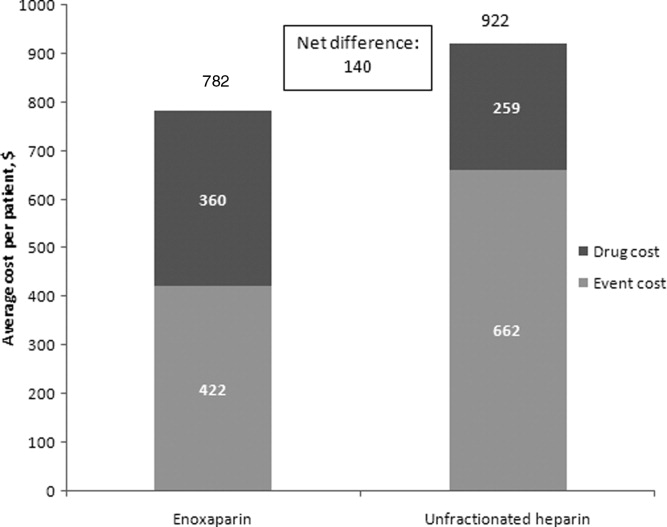

The average hospital cost with enoxaparin, when taking into account the costs of VTE and bleeding, was lower than with UFH ($422 vs $662, respectively), with a net savings of $240 per patient if enoxaparin was used. The average drug costs, including drug‐administration costs, were higher in the enoxaparin group ($360) compared with the UFH group ($259; difference $101). Nevertheless, the total hospital cost when clinical events and drug costs were considered together, was lower with enoxaparin than UFH. The total hospital costs per patient were $782 in patients receiving prophylaxis with enoxaparin and $922 in patients receiving UFH. Thus, enoxaparin was associated with a total cost‐savings of $140 per patient (Figure 2).

The cost estimates according to the stroke severity score (NIHSS scores <14 vs 14) are described in Table 3. The drug costs were consistent, regardless of stroke severity, for enoxaparin ($360) and for UFH ($259). However, in both treatment groups, the event costs were higher in patients with more severe stroke, compared with less severe stroke. For example, in the enoxaparin group, the event costs were $686 in patients with NIHSS scores 14 and $326 in patients with NIHSS scores <14. Nevertheless, the overall costs (event costs plus drug costs) were lower with enoxaparin compared with UFH, both in patients with less severe and more severe stroke. In fact, the total hospital cost‐savings were greater when enoxaparin was used instead of UFH in patients with more severe stroke (cost‐saving $287 if NIHSS score 14 vs $71 if NIHSS score <14) (Table 3).

| Enoxaparin ($) | UFH ($) | Difference ($ [UFHEnoxaparin]) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| NIHSS score <14 | |||

| Mean event costs per patient | 326 | 497 | 171 |

| Mean drug costs per patient* | 360 | 259 | 101 |

| Total costs | 685 | 756 | 71 |

| NIHSS score 14 | |||

| Mean event costs per patient | 686 | 1,073 | 387 |

| Mean drug costs per patient* | 360 | 259 | 101 |

| Total costs | 1,046 | 1,332 | 287 |

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed. In the base case univariate sensitivity analysis, individual costs were adjusted by 20% (Table 4). If the cost of DVT increased by 20% (from $3003 to $3604) the difference between the enoxaparin and UFH groups was $187. When the cost of DVT was decreased by 20% to $2402, enoxaparin was still cost‐saving, with a difference of $94. For each of the individual cost parameters that were varied (DVT, PE, intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor hemorrhage), enoxaparin was always less costly than UFH. Subsequent sensitivity analyses were performed (not shown) where cost parameters were varied by 5%, 10%, 15%, 30%, and 40%. Enoxaparin remained less costly than UFH in all cases.

| Event | Baseline Cost Input ($) | +20% Cost Input ($) | +20% Difference ($ [UFH Enoxaparin]) (% Change) | 20% Cost Input ($) | 20% Difference ($ [UFH Enoxaparin]) (% Change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 3,003 | 3,604 | 187 (33) | 2,402 | 94 (33) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2,143 | 2,572 | 144 (2.5) | 1,714 | 137 (2.5) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4,001 | 4,801 | 142 (1.3) | 3,201 | 138 (1.3) |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 3,534 | 4,241 | 134 (4.0) | 2,827 | 146 (4.0) |

| Minor hemorrhage | 1,322 | 1,586 | 142 (1.3) | 1,058 | 138 (1.3) |

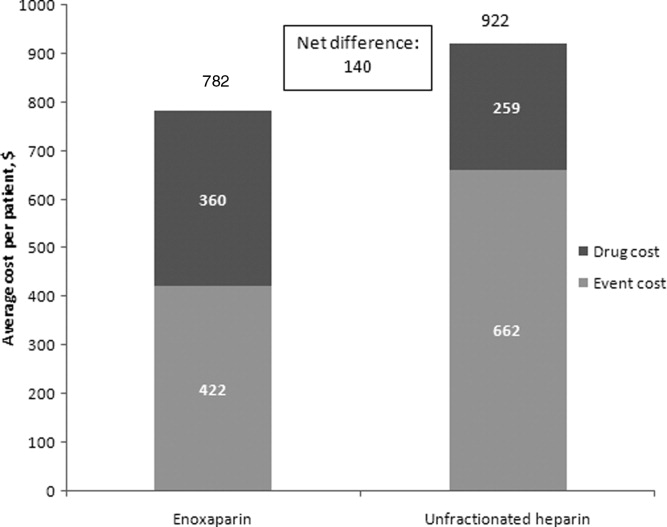

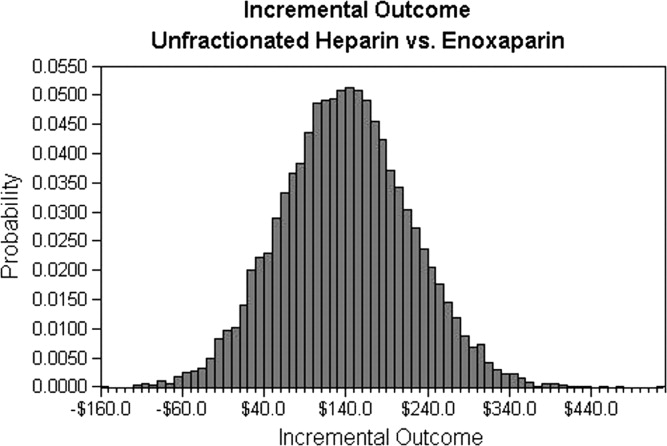

A multivariate analysis was performed using a Monte Carlo simulation in TreeAge Pro (Figure 3). When all parameters were varied simultaneously (by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40%) and the differences in costs between the enoxaparin and UFH groups were measured and plotted, the mean (standard deviation) difference between enoxaparin and UFH prophylaxis was $140 ($79) (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows a graphical presentation of the sensitivity analysis results for event probabilities and costs. Differences in enoxaparin drug costs, hospital costs for DVT, and probability of DVT for patients on enoxaparin are the factors that have the greatest effect on the overall cost.

Finally, an additional scenario was performed using a published ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE, due to the fact that not all VTE events in the real‐world present with symptoms prompting treatment. Quinlan et al. determined a ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE of 5 for total hip replacement patients and of 21 for total knee replacement patients.28 Although derived from different patient populations who received different anticoagulants, we utilized the symptomatic event rates from the pooled studies to recalculate cost differences between enoxaparin and UFH in acute ischemic stroke. Using only symptomatic event rates, based on the 21:1 ratio in patients undergoing total knee replacement, the total cost for enoxaparin was $485 compared to $386 for UFH. Similar results were found based on the 5:1 ratio in patients with total hip replacement (enoxaparin $532 vs $472 for UFH). This was the only scenario where the higher drug cost of prophylaxis with enoxaparin was not completely offset by the reduction in events compared to UFH, likely due to the smaller difference in event rates once examining only symptomatic VTE.

DISCUSSION

This analysis demonstrates that, from the hospital perspective, enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously once‐daily is associated with lower total hospital costs and is more cost‐effective than twice‐daily UFH 5000 U subcutaneously for the prevention of VTE in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Despite higher drug‐acquisition costs, enoxaparin was associated with total cost‐savings of $140 per patient. This is due to the lower event rates with enoxaparin compared with UFH.

Previous studies, using hospital or payer information, have shown that VTE prophylaxis is more cost‐effective compared with no prophylaxis. In terms of the different VTE prophylaxis regimens, enoxaparin represents a more cost‐effective option in comparison with UFH19, 21, 2932 and also when compared with fondaparinux.21, 33 When comparing the results between different trials, it should be noted that previous analyses were mainly modeled on the Prophylaxis in Medical Patients with Enoxaparin (MEDENOX) study, which was performed in general medical patients and reported a VTE rate of 5.5%.6 However, patients with acute ischemic stroke are at a higher risk of VTE, with a 10% incidence of VTE reported in the PREVAIL study.14 Furthermore, twice‐daily rather than three‐timesdaily administration of UFH was used in the PREVAIL study, based on the current practice patterns seen during the PREVAIL trial design.

A recent retrospective analysis of transactional billing records demonstrated that, despite higher mean costs of anticoagulation therapy, the mean, total, adjusted direct hospital costs were lower with LMWH thromboprophylaxis compared with UFH ($7358 vs $8680, respectively; difference $1322; P < 0.001).21 A previous study by Burleigh and colleagues based on hospital discharge information extracted from both medical and surgical patients, has a sub‐analysis in patients with stroke. In these patients also, the total costs were lower for enoxaparin compared with UFH ($8608 vs $8911, respectively; difference $303).29 In the Burleigh study, drug costs and total discharge costs (eg, room and board, laboratory, and diagnostic imaging) were derived from drug charges and total charges, and were converted to estimated costs using cost‐to‐charge methods, so the absolute figures are not directly comparable with the current analysis.

This study adds to current literature by using data from a prospective study to analyze the hospital costs of VTE prophylaxis in stroke patients. The current study also provides a valuable cost‐analysis regarding a specific subgroup of medical patients at particularly high risk of VTE, and provides an economic comparison among stroke patients with NIHSS scores of <14 versus 14. In the PREVAIL study, despite a 2‐fold higher incidence of VTE in patients with more severe stroke (16.3% vs 8.3%), a similar reduction in VTE risk was observed with enoxaparin versus UFH in patients with NIHSS scores of 14 (odds ratio = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.37‐0.84; P = 0.0036) and <14 (odds ratio = 0.46; 95% CI = 0.27‐0.78; P = 0.0043).14 Enoxaparin was shown to be cost‐saving relative to UFH in both patient groups and, in particular, in patients with more severe stroke.

Potential limitations of the current analysis include the applicability of the figures obtained from the highly selected clinical trial population to real‐world clinical practice, and the fact that it is difficult to match cost estimates to trial data definitions. For example, this analysis was conducted with a comparator of twice‐daily UFH (as opposed to three‐timesdaily) which may be used in the real‐world setting and may have resulted in the increased number of events in the UFH group seen in the PREVAIL study. Due to a variety of differences between real‐world practice patterns and the PREVAIL clinical trial, we can only speculate as to the true cost‐consequences of utilizing enoxaparin versus UFH.

Furthermore, the original model did not include a sub‐analysis regarding the rates and, therefore, costs of proximal/symptomatic VTE. In the primary study of PREVAIL, the rates of symptomatic DVT were 1 in 666 patients (<1%) for enoxaparin and 4 in 669 patients (1%) for UFH, whereas the rates of proximal DVT were 30 in 666 patients (5%) and 64 in 669 patients (10%), respectively. Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the impact of lower rates of both DVT and PE (up to 40%), and the differences between groups were found to be robust. However, it is important to note that overall costs for both groups may have been increased through the inclusion of asymptomatic costs, with a more distinct separation of these costs making for a good follow‐up study. In a similar cost‐analysis we performed based on the PREVAIL study, which assessed the cost to the payer, we included an analysis of costs according to 3 different VTE definitions: the PREVAIL VTE definition (as in the current study); a definition of major VTE (PE, symptomatic DVT, and asymptomatic proximal DVT); and primary endpoints recommended by the European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use for studies on VTE (proximal DVT, nonfatal PE, and all‐cause mortality). We found similar results irrespective of clinical event definitions.34 In an additional model scenario using a published ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE,28 the higher drug cost of prophylaxis with enoxaparin was not completely offset by the reduction in events compared to UFH. This was likely due to the smaller difference in event rates once examining only symptomatic VTE. This scenario was limited by the fact that the ratio was derived from different patient populations receiving different anticoagulants than stroke patients.

In conclusion, data from this analysis adds to the evidence that, from the hospital perspective, the higher drug cost of enoxaparin is offset by the economic consequences of the events avoided as compared with UFH for the prevention of VTE following acute ischemic stroke, particularly in patients with severe stroke.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aylin Lee from I3 Innovus for her contribution to this study. The authors also acknowledge Min Chen for her assistance in statistical analysis, and Essy Mozaffari for his contribution to this study.

- .Venous thromboembolism: disease burden, outcomes and risk factors.J Thromb Haemost.2005;3:1611–1617.

- .The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management.J Thromb Thrombolysis.2006;21:23–29.

- ,,, et al.Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based study.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1245–1248.

- ,,,,,.Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based case‐control study.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:809–815.

- ,.A safety analysis of thromboprophylaxis in acute medical illness.Thromb Haemost.2003;89:590–591.

- ,,,,.Quantification of risk factors for venous thromboembolism: a preliminary study for the development of a risk assessment tool.Haematologica.2003;88:1410–1421.

- ,.Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in acute hemorrhagic and thromboembolic stroke.Am J Phys Med Rehabil.2003;82:364–369.

- ,,,.Thromboprophylaxis rates in US medical centers: success or failure?J Thromb Haemost.2007;5:1610–1616.

- ,,,.Complications after acute stroke.Stroke.1996;27:415–420.

- ,,,.Venous thromboembolism after acute stroke.Stroke.2001;32:262–267.

- ,,,,,.Enoxaparin vs heparin for prevention of deep‐vein thrombosis in acute ischaemic stroke: a randomized, double‐blind study.Acta Neurol Scand.2002;106:84–92.

- ,,.Low‐molecular‐weight heparins or heparinoids versus standard unfractionated heparin for acute ischaemic stroke.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2008;(3):CD000119.

- ,,, et al;for the PROTECT Trial Group.Prophylaxis of thrombotic and embolic events in acute ischemic stroke with the low‐molecular‐weight heparin certoparin: results of the PROTECT Trial.Stroke.2006;37:139–144.

- ,,, et al;for the PREVAIL Investigators.The efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after acute ischaemic stroke (PREVAIL study): an open‐label randomised comparison.Lancet.2007;369:1347–1355.

- ,,, et al;for the American College of Chest Physicians.Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed).Chest.2008;133(6 suppl):381S–453S.

- ,,,,;for the American College of Chest Physicians.Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed).Chest.2008;133(6 suppl):630S–669S.

- ,,,.Management of acute proximal deep vein thrombosis: pharmacoeconomic evaluation of outpatient treatment with enoxaparin vs inpatient treatment with unfractionated heparin.Chest.2002;122:108–114.

- ,.Economic evaluation of enoxaparin as prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in seriously ill medical patients: a US perspective.Am J Manag Care.2002;8:1082–1088.

- ,,,.Cost effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis with a low‐molecular‐weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin in acutely ill medical inpatients.Am J Manag Care.2004;10:632–642.

- ,,, et al.Cost effectiveness of enoxaparin as prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic complications in acutely ill medical inpatients: modelling study from the hospital perspective in Germany.Pharmacoeconomics.2006;24:571–591.

- ,,,,.Hospital‐based costs associated with venous thromboembolism prophylaxis regimens.J Thromb Thrombolysis.2010;29:449–458.

- ,,, et al;for the ENDORSE Investigators.Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross‐sectional study.Lancet.2008;371:387–394.

- ,,, et al;for the IMPROVE Investigators.Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: findings from the International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism.Chest.2007;132:936–945.

- United States Department of Health August 2008. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/vtguide/. Accessed August 18,2010.

- ,,,.Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after acute ischemic stroke: rationale, design, and methods of an open‐label, randomized, parallel‐group multicenter trial.J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis.2005;14:95–100.

- ,,,,,.Association between asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by venography and symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing elective hip or knee surgery.J Thromb Haemost.2007;5:1438–1443.

- ,,, et al.Thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients at risk for venous thromboembolism.Am J Health Syst Pharm.2006;63(20 suppl 6):S23–S29.

- ,,,.Comparison of the two‐year outcomes and costs of prophylaxis in medical patients at risk of venous thromboembolism.Thromb Haemost.2008;100:810–820.

- ,,,,,.Cost for inpatient care of venous thrombosis: a trial of enoxaparin vs standard heparin.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3160–3165.

- ,,,.Economic evaluation of enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients.Pharm World Sci.2004;26:214–220.

- ,,,,.Total hospital‐based costs of enoxaparin or fondaparinux prophylaxis in patients at risk of venous thromboembolism [abstract]. Presented at the Chest 2008 Annual Meeting; October 25–30,2008; Philadelphia, PA.

- ,,,,.Economic impact of enoxaparin after acute ischemic stroke based on PREVAIL.Clin Appl Thromb Hemost.2011;17:150–157.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which encompasses both deep‐vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major health problem in the United States and worldwide. It represents one of the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality with an estimated 300,000 VTE‐related deaths,1 and 300,000‐600,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually.2 Hospitalization for medical illness is associated with a similar proportion of VTE cases as hospitalization for surgery.3 Several groups of medical patients have been shown to be at an increased risk of VTE, including those with cancer, severe respiratory disease, acute infectious illness, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and acute ischemic stroke.47 Ischemic stroke patients represent approximately 4.6% of medical patients at high risk of VTE in US hospitals.8 The incidence of DVT in such patients has been reported to be as high as 75%9 and PE has been reported to be responsible for up to 25% of early deaths after stroke.10

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of unfractionated heparin (UFH) or a low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) in the prevention of VTE in stroke patients, and have demonstrated that LMWHs are at least as effective as UFH.1114 The open‐label, randomized Prevention of VTE after acute ischemic stroke with LMWH and UFH (PREVAIL) trial demonstrated that in patients with acute ischemic stroke, prophylaxis for 10 days with the LMWH enoxaparin reduces the risk of VTE by 43% compared with UFH (10.2% vs 18.1%, respectively; relative risk = 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.44‐0.76; P = 0.0001) without increasing the incidence of overall bleeding events (7.9% vs 8.1%, respectively; P = 0.83), or the composite of symptomatic intracranial and major extracranial hemorrhage (1% in each group; P = 0.23). There was, however, a slight but significant increase in major extracranial hemorrhage alone with enoxaparin (1% vs 0%; P = 0.015).14 Evidence‐based guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) provide recommendations for appropriate thromboprophylaxis regimens for patients at risk of VTE.15 Thromboprophylaxis with UFH, LMWH, and, more recently, fondaparinux is recommended for medical patients admitted to hospital with congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease, or those who are confined to bed and have one or more additional risk factors, including active cancer, previous VTE, or acute neurologic disease.15 Similarly, in the Eighth ACCP Clinical Practice Guidelines, low‐dose UFH or LMWH are recommended for VTE prevention in patients with ischemic stroke who have restricted mobility.16

VTE is also associated with a substantial economic burden on the healthcare system, costing an estimated $1.5 billion annually in the United States.17 Thromboprophylaxis has been shown to be a cost‐effective strategy in hospitalized medical patients. Prophylaxis with a LMWH has been shown to be more cost‐effective than UFH in these patients.1821

However, despite the clinical and economic benefits, prophylaxis is still commonly underused in medical patients.22, 23 In surgical patients, the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) focuses on reducing surgical complications, and has endorsed 2 measures: VTE‐1, relating to the proportion of patients for whom VTE prophylaxis is ordered; and VTE‐2, relating to those who receive the recommended regimen (

The objective of the current study was to determine the economic impact, in terms of hospital costs, of enoxaparin compared with UFH for VTE prophylaxis after acute ischemic stroke. A decision‐analytic model was constructed using data from the PREVAIL study and historical inpatient data from a multi‐hospital database.

METHODS

In this study, the cost implications, from the hospital perspective, of VTE prophylaxis with enoxaparin or UFH in patients with acute ischemic stroke, were determined using a decision‐analytic model in TreeAge Pro Suite (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA). The decision‐tree was based on 3 stages: (a) whether patients received enoxaparin or UFH; (b) how patients were classified according to their National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) classification scores (<14 or 14); and (c) which clinical event each patient experienced, as defined per the PREVAIL trial (DVT, PE, intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor extracranial hemorrhage) (Figure 1). The time horizon for the model was established at 90 days to mirror the length of follow‐up in the PREVAIL trial.

Total hospital costs were calculated based on clinical event rates (from the PREVAIL trial) and the costs of each clinical event, which were calculated separately according to the descriptions below, and then inserted into the decision‐analytic model. The clinical event rates were calculated from the efficacy and safety endpoints collected in the PREVAIL trial, and included VTE events (DVT and PE) and bleeding events (intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor extracranial hemorrhage). Details of the patient population, eligibility criteria, and treatment regimen have previously been published in full elsewhere.14, 27

The costs of clinical events during hospitalization were estimated using a multivariate cost‐evaluation model, based on mean hospital costs for the events in the (Premier Inc., Charlotte, NC, USA) multi‐hospital database, one of the largest US hospital clinical and economic databases. The data are received from over 600 hospitals, representing all geographical areas of the United States, a broad range of bed sizes, teaching and non‐teaching, and urban and rural facilities. This database contains detailed US inpatient care records of principal and secondary diagnoses, inpatient procedures, administered laboratory tests, dispensed drugs, and demographic information. The evaluation of hospital cost for each type of clinical event was conducted by i3 Innovus (Ingenix, Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, USA). Total hospital costs were cumulative from all events, so if patients experienced multiple clinical events, the costs of the events were additive. The cost for stroke treatment and management was not included because it is an inclusion criterion of the PREVAIL trial and, thus, all patients in the trial have such costs.

Default drug costs were taken from the 2008 US wholesalers' acquisition cost data. The default dosing schedule is based on information extracted from the PREVAIL trial: enoxaparin 40 mg (once‐daily) and UFH 5000 U (twice‐daily) for 10 days each ($25.97 and $2.97, respectively). A drug‐administration fee was added for each dose of either enoxaparin or UFH ($10 for each).19

The estimated hospital cost of clinical events, along with drug costs, were inserted into the decision‐analytic model in TreeAge Pro Suite to estimate the cost per discharge from the hospital perspective in patients with ischemic stroke receiving VTE prophylaxis with enoxaparin or UFH. An additional analysis was performed to investigate the costs and cost differences in patients with less severe stroke (NIHSS scores <14) and more severe stroke (NIHSS scores 14).

Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the impact of varying the cost inputs on the total hospital cost of each treatment arm by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, and the robustness in the difference in costs between the enoxaparin and UFH groups. Univariate (via tornado diagram in TreeAge Pro Suite) and multivariate (via Monte Carlo simulation in TreeAge Pro Suite) analyses were performed. For the univariate analysis, each clinical event cost was adjusted individually, increasing or decreasing by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30% and 40% while other parameters remained unchanged. For the Monte Carlo simulation (TreeAge Pro Suite), all the parameters were simultaneously varied in a random fashion, within a range of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40% over 10,000 trials. The simulation adopted a gamma distribution assumption for input sampling for cost parameters and a beta distribution for the event probability parameters. The confidence intervals for the probability parameters were obtained from the PREVAIL trial. The differences between the enoxaparin and UFH treatment groups were plotted in a graph against the variation in costs of each clinical event.

RESULTS

The clinical VTE and bleeding event rates as collected from the PREVAIL trial are shown in Table 1. The hospital costs per clinical event are shown in Table 2. The most costly clinical event from the hospital perspective was intracranial hemorrhage at $4001, followed by major extracranial hemorrhage at $3534. The costs of DVT and PE were $3003 and $2143, respectively.

| Event Rate | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Enoxaparin (NIHSS <14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.081 | 0.05730.1048 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.002 | 0.000050.011 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0031 | 00.0074 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0.0047 | 00.0099 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0372 | 0.0240.0549 |

| Enoxaparin (NIHSS 14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.1625 | 0.10530.2197 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 00 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0086 | 00.0205 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0.0172 | 0.04660.1198 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0776 | 0.04660.1198 |

| UFH (NIHSS <14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.1356 | 0.10540.1658 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.004 | 0.00050.0145 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0032 | 00.0077 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 00 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0514 | 0.03550.0719 |

| UFH (NIHSS 14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.2914 | 0.22410.3588 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.0229 | 0.00630.0575 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.016 | 0.00040.0316 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 00 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.064 | 0.0370.1019 |

| Event | Cost per Event ($)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Likeliest | Minimum | Maximum | |

| |||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 3,003 | 2,402 | 3,604 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2,143 | 1,714 | 2,572 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4,001 | 3,201 | 4,801 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 3,534 | 2,827 | 4,241 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 1,322 | 1,058 | 1,586 |

| Enoxaparin cost per dose | 26 | 21 | 31 |

| Unfractionated heparin cost per dose | 3 | 2 | 4 |

The average hospital cost with enoxaparin, when taking into account the costs of VTE and bleeding, was lower than with UFH ($422 vs $662, respectively), with a net savings of $240 per patient if enoxaparin was used. The average drug costs, including drug‐administration costs, were higher in the enoxaparin group ($360) compared with the UFH group ($259; difference $101). Nevertheless, the total hospital cost when clinical events and drug costs were considered together, was lower with enoxaparin than UFH. The total hospital costs per patient were $782 in patients receiving prophylaxis with enoxaparin and $922 in patients receiving UFH. Thus, enoxaparin was associated with a total cost‐savings of $140 per patient (Figure 2).

The cost estimates according to the stroke severity score (NIHSS scores <14 vs 14) are described in Table 3. The drug costs were consistent, regardless of stroke severity, for enoxaparin ($360) and for UFH ($259). However, in both treatment groups, the event costs were higher in patients with more severe stroke, compared with less severe stroke. For example, in the enoxaparin group, the event costs were $686 in patients with NIHSS scores 14 and $326 in patients with NIHSS scores <14. Nevertheless, the overall costs (event costs plus drug costs) were lower with enoxaparin compared with UFH, both in patients with less severe and more severe stroke. In fact, the total hospital cost‐savings were greater when enoxaparin was used instead of UFH in patients with more severe stroke (cost‐saving $287 if NIHSS score 14 vs $71 if NIHSS score <14) (Table 3).

| Enoxaparin ($) | UFH ($) | Difference ($ [UFHEnoxaparin]) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| NIHSS score <14 | |||

| Mean event costs per patient | 326 | 497 | 171 |

| Mean drug costs per patient* | 360 | 259 | 101 |

| Total costs | 685 | 756 | 71 |

| NIHSS score 14 | |||

| Mean event costs per patient | 686 | 1,073 | 387 |

| Mean drug costs per patient* | 360 | 259 | 101 |

| Total costs | 1,046 | 1,332 | 287 |

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed. In the base case univariate sensitivity analysis, individual costs were adjusted by 20% (Table 4). If the cost of DVT increased by 20% (from $3003 to $3604) the difference between the enoxaparin and UFH groups was $187. When the cost of DVT was decreased by 20% to $2402, enoxaparin was still cost‐saving, with a difference of $94. For each of the individual cost parameters that were varied (DVT, PE, intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor hemorrhage), enoxaparin was always less costly than UFH. Subsequent sensitivity analyses were performed (not shown) where cost parameters were varied by 5%, 10%, 15%, 30%, and 40%. Enoxaparin remained less costly than UFH in all cases.

| Event | Baseline Cost Input ($) | +20% Cost Input ($) | +20% Difference ($ [UFH Enoxaparin]) (% Change) | 20% Cost Input ($) | 20% Difference ($ [UFH Enoxaparin]) (% Change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 3,003 | 3,604 | 187 (33) | 2,402 | 94 (33) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2,143 | 2,572 | 144 (2.5) | 1,714 | 137 (2.5) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4,001 | 4,801 | 142 (1.3) | 3,201 | 138 (1.3) |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 3,534 | 4,241 | 134 (4.0) | 2,827 | 146 (4.0) |

| Minor hemorrhage | 1,322 | 1,586 | 142 (1.3) | 1,058 | 138 (1.3) |

A multivariate analysis was performed using a Monte Carlo simulation in TreeAge Pro (Figure 3). When all parameters were varied simultaneously (by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40%) and the differences in costs between the enoxaparin and UFH groups were measured and plotted, the mean (standard deviation) difference between enoxaparin and UFH prophylaxis was $140 ($79) (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows a graphical presentation of the sensitivity analysis results for event probabilities and costs. Differences in enoxaparin drug costs, hospital costs for DVT, and probability of DVT for patients on enoxaparin are the factors that have the greatest effect on the overall cost.

Finally, an additional scenario was performed using a published ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE, due to the fact that not all VTE events in the real‐world present with symptoms prompting treatment. Quinlan et al. determined a ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE of 5 for total hip replacement patients and of 21 for total knee replacement patients.28 Although derived from different patient populations who received different anticoagulants, we utilized the symptomatic event rates from the pooled studies to recalculate cost differences between enoxaparin and UFH in acute ischemic stroke. Using only symptomatic event rates, based on the 21:1 ratio in patients undergoing total knee replacement, the total cost for enoxaparin was $485 compared to $386 for UFH. Similar results were found based on the 5:1 ratio in patients with total hip replacement (enoxaparin $532 vs $472 for UFH). This was the only scenario where the higher drug cost of prophylaxis with enoxaparin was not completely offset by the reduction in events compared to UFH, likely due to the smaller difference in event rates once examining only symptomatic VTE.

DISCUSSION

This analysis demonstrates that, from the hospital perspective, enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously once‐daily is associated with lower total hospital costs and is more cost‐effective than twice‐daily UFH 5000 U subcutaneously for the prevention of VTE in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Despite higher drug‐acquisition costs, enoxaparin was associated with total cost‐savings of $140 per patient. This is due to the lower event rates with enoxaparin compared with UFH.

Previous studies, using hospital or payer information, have shown that VTE prophylaxis is more cost‐effective compared with no prophylaxis. In terms of the different VTE prophylaxis regimens, enoxaparin represents a more cost‐effective option in comparison with UFH19, 21, 2932 and also when compared with fondaparinux.21, 33 When comparing the results between different trials, it should be noted that previous analyses were mainly modeled on the Prophylaxis in Medical Patients with Enoxaparin (MEDENOX) study, which was performed in general medical patients and reported a VTE rate of 5.5%.6 However, patients with acute ischemic stroke are at a higher risk of VTE, with a 10% incidence of VTE reported in the PREVAIL study.14 Furthermore, twice‐daily rather than three‐timesdaily administration of UFH was used in the PREVAIL study, based on the current practice patterns seen during the PREVAIL trial design.

A recent retrospective analysis of transactional billing records demonstrated that, despite higher mean costs of anticoagulation therapy, the mean, total, adjusted direct hospital costs were lower with LMWH thromboprophylaxis compared with UFH ($7358 vs $8680, respectively; difference $1322; P < 0.001).21 A previous study by Burleigh and colleagues based on hospital discharge information extracted from both medical and surgical patients, has a sub‐analysis in patients with stroke. In these patients also, the total costs were lower for enoxaparin compared with UFH ($8608 vs $8911, respectively; difference $303).29 In the Burleigh study, drug costs and total discharge costs (eg, room and board, laboratory, and diagnostic imaging) were derived from drug charges and total charges, and were converted to estimated costs using cost‐to‐charge methods, so the absolute figures are not directly comparable with the current analysis.

This study adds to current literature by using data from a prospective study to analyze the hospital costs of VTE prophylaxis in stroke patients. The current study also provides a valuable cost‐analysis regarding a specific subgroup of medical patients at particularly high risk of VTE, and provides an economic comparison among stroke patients with NIHSS scores of <14 versus 14. In the PREVAIL study, despite a 2‐fold higher incidence of VTE in patients with more severe stroke (16.3% vs 8.3%), a similar reduction in VTE risk was observed with enoxaparin versus UFH in patients with NIHSS scores of 14 (odds ratio = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.37‐0.84; P = 0.0036) and <14 (odds ratio = 0.46; 95% CI = 0.27‐0.78; P = 0.0043).14 Enoxaparin was shown to be cost‐saving relative to UFH in both patient groups and, in particular, in patients with more severe stroke.

Potential limitations of the current analysis include the applicability of the figures obtained from the highly selected clinical trial population to real‐world clinical practice, and the fact that it is difficult to match cost estimates to trial data definitions. For example, this analysis was conducted with a comparator of twice‐daily UFH (as opposed to three‐timesdaily) which may be used in the real‐world setting and may have resulted in the increased number of events in the UFH group seen in the PREVAIL study. Due to a variety of differences between real‐world practice patterns and the PREVAIL clinical trial, we can only speculate as to the true cost‐consequences of utilizing enoxaparin versus UFH.

Furthermore, the original model did not include a sub‐analysis regarding the rates and, therefore, costs of proximal/symptomatic VTE. In the primary study of PREVAIL, the rates of symptomatic DVT were 1 in 666 patients (<1%) for enoxaparin and 4 in 669 patients (1%) for UFH, whereas the rates of proximal DVT were 30 in 666 patients (5%) and 64 in 669 patients (10%), respectively. Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the impact of lower rates of both DVT and PE (up to 40%), and the differences between groups were found to be robust. However, it is important to note that overall costs for both groups may have been increased through the inclusion of asymptomatic costs, with a more distinct separation of these costs making for a good follow‐up study. In a similar cost‐analysis we performed based on the PREVAIL study, which assessed the cost to the payer, we included an analysis of costs according to 3 different VTE definitions: the PREVAIL VTE definition (as in the current study); a definition of major VTE (PE, symptomatic DVT, and asymptomatic proximal DVT); and primary endpoints recommended by the European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use for studies on VTE (proximal DVT, nonfatal PE, and all‐cause mortality). We found similar results irrespective of clinical event definitions.34 In an additional model scenario using a published ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE,28 the higher drug cost of prophylaxis with enoxaparin was not completely offset by the reduction in events compared to UFH. This was likely due to the smaller difference in event rates once examining only symptomatic VTE. This scenario was limited by the fact that the ratio was derived from different patient populations receiving different anticoagulants than stroke patients.

In conclusion, data from this analysis adds to the evidence that, from the hospital perspective, the higher drug cost of enoxaparin is offset by the economic consequences of the events avoided as compared with UFH for the prevention of VTE following acute ischemic stroke, particularly in patients with severe stroke.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aylin Lee from I3 Innovus for her contribution to this study. The authors also acknowledge Min Chen for her assistance in statistical analysis, and Essy Mozaffari for his contribution to this study.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which encompasses both deep‐vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a major health problem in the United States and worldwide. It represents one of the most significant causes of morbidity and mortality with an estimated 300,000 VTE‐related deaths,1 and 300,000‐600,000 hospitalizations in the United States annually.2 Hospitalization for medical illness is associated with a similar proportion of VTE cases as hospitalization for surgery.3 Several groups of medical patients have been shown to be at an increased risk of VTE, including those with cancer, severe respiratory disease, acute infectious illness, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and acute ischemic stroke.47 Ischemic stroke patients represent approximately 4.6% of medical patients at high risk of VTE in US hospitals.8 The incidence of DVT in such patients has been reported to be as high as 75%9 and PE has been reported to be responsible for up to 25% of early deaths after stroke.10

Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of unfractionated heparin (UFH) or a low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) in the prevention of VTE in stroke patients, and have demonstrated that LMWHs are at least as effective as UFH.1114 The open‐label, randomized Prevention of VTE after acute ischemic stroke with LMWH and UFH (PREVAIL) trial demonstrated that in patients with acute ischemic stroke, prophylaxis for 10 days with the LMWH enoxaparin reduces the risk of VTE by 43% compared with UFH (10.2% vs 18.1%, respectively; relative risk = 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.44‐0.76; P = 0.0001) without increasing the incidence of overall bleeding events (7.9% vs 8.1%, respectively; P = 0.83), or the composite of symptomatic intracranial and major extracranial hemorrhage (1% in each group; P = 0.23). There was, however, a slight but significant increase in major extracranial hemorrhage alone with enoxaparin (1% vs 0%; P = 0.015).14 Evidence‐based guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) provide recommendations for appropriate thromboprophylaxis regimens for patients at risk of VTE.15 Thromboprophylaxis with UFH, LMWH, and, more recently, fondaparinux is recommended for medical patients admitted to hospital with congestive heart failure or severe respiratory disease, or those who are confined to bed and have one or more additional risk factors, including active cancer, previous VTE, or acute neurologic disease.15 Similarly, in the Eighth ACCP Clinical Practice Guidelines, low‐dose UFH or LMWH are recommended for VTE prevention in patients with ischemic stroke who have restricted mobility.16

VTE is also associated with a substantial economic burden on the healthcare system, costing an estimated $1.5 billion annually in the United States.17 Thromboprophylaxis has been shown to be a cost‐effective strategy in hospitalized medical patients. Prophylaxis with a LMWH has been shown to be more cost‐effective than UFH in these patients.1821

However, despite the clinical and economic benefits, prophylaxis is still commonly underused in medical patients.22, 23 In surgical patients, the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) focuses on reducing surgical complications, and has endorsed 2 measures: VTE‐1, relating to the proportion of patients for whom VTE prophylaxis is ordered; and VTE‐2, relating to those who receive the recommended regimen (

The objective of the current study was to determine the economic impact, in terms of hospital costs, of enoxaparin compared with UFH for VTE prophylaxis after acute ischemic stroke. A decision‐analytic model was constructed using data from the PREVAIL study and historical inpatient data from a multi‐hospital database.

METHODS

In this study, the cost implications, from the hospital perspective, of VTE prophylaxis with enoxaparin or UFH in patients with acute ischemic stroke, were determined using a decision‐analytic model in TreeAge Pro Suite (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA, USA). The decision‐tree was based on 3 stages: (a) whether patients received enoxaparin or UFH; (b) how patients were classified according to their National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) classification scores (<14 or 14); and (c) which clinical event each patient experienced, as defined per the PREVAIL trial (DVT, PE, intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor extracranial hemorrhage) (Figure 1). The time horizon for the model was established at 90 days to mirror the length of follow‐up in the PREVAIL trial.

Total hospital costs were calculated based on clinical event rates (from the PREVAIL trial) and the costs of each clinical event, which were calculated separately according to the descriptions below, and then inserted into the decision‐analytic model. The clinical event rates were calculated from the efficacy and safety endpoints collected in the PREVAIL trial, and included VTE events (DVT and PE) and bleeding events (intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor extracranial hemorrhage). Details of the patient population, eligibility criteria, and treatment regimen have previously been published in full elsewhere.14, 27

The costs of clinical events during hospitalization were estimated using a multivariate cost‐evaluation model, based on mean hospital costs for the events in the (Premier Inc., Charlotte, NC, USA) multi‐hospital database, one of the largest US hospital clinical and economic databases. The data are received from over 600 hospitals, representing all geographical areas of the United States, a broad range of bed sizes, teaching and non‐teaching, and urban and rural facilities. This database contains detailed US inpatient care records of principal and secondary diagnoses, inpatient procedures, administered laboratory tests, dispensed drugs, and demographic information. The evaluation of hospital cost for each type of clinical event was conducted by i3 Innovus (Ingenix, Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, USA). Total hospital costs were cumulative from all events, so if patients experienced multiple clinical events, the costs of the events were additive. The cost for stroke treatment and management was not included because it is an inclusion criterion of the PREVAIL trial and, thus, all patients in the trial have such costs.

Default drug costs were taken from the 2008 US wholesalers' acquisition cost data. The default dosing schedule is based on information extracted from the PREVAIL trial: enoxaparin 40 mg (once‐daily) and UFH 5000 U (twice‐daily) for 10 days each ($25.97 and $2.97, respectively). A drug‐administration fee was added for each dose of either enoxaparin or UFH ($10 for each).19

The estimated hospital cost of clinical events, along with drug costs, were inserted into the decision‐analytic model in TreeAge Pro Suite to estimate the cost per discharge from the hospital perspective in patients with ischemic stroke receiving VTE prophylaxis with enoxaparin or UFH. An additional analysis was performed to investigate the costs and cost differences in patients with less severe stroke (NIHSS scores <14) and more severe stroke (NIHSS scores 14).

Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the impact of varying the cost inputs on the total hospital cost of each treatment arm by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, and the robustness in the difference in costs between the enoxaparin and UFH groups. Univariate (via tornado diagram in TreeAge Pro Suite) and multivariate (via Monte Carlo simulation in TreeAge Pro Suite) analyses were performed. For the univariate analysis, each clinical event cost was adjusted individually, increasing or decreasing by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30% and 40% while other parameters remained unchanged. For the Monte Carlo simulation (TreeAge Pro Suite), all the parameters were simultaneously varied in a random fashion, within a range of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40% over 10,000 trials. The simulation adopted a gamma distribution assumption for input sampling for cost parameters and a beta distribution for the event probability parameters. The confidence intervals for the probability parameters were obtained from the PREVAIL trial. The differences between the enoxaparin and UFH treatment groups were plotted in a graph against the variation in costs of each clinical event.

RESULTS

The clinical VTE and bleeding event rates as collected from the PREVAIL trial are shown in Table 1. The hospital costs per clinical event are shown in Table 2. The most costly clinical event from the hospital perspective was intracranial hemorrhage at $4001, followed by major extracranial hemorrhage at $3534. The costs of DVT and PE were $3003 and $2143, respectively.

| Event Rate | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Enoxaparin (NIHSS <14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.081 | 0.05730.1048 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.002 | 0.000050.011 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0031 | 00.0074 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0.0047 | 00.0099 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0372 | 0.0240.0549 |

| Enoxaparin (NIHSS 14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.1625 | 0.10530.2197 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 00 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0086 | 00.0205 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0.0172 | 0.04660.1198 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0776 | 0.04660.1198 |

| UFH (NIHSS <14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.1356 | 0.10540.1658 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.004 | 0.00050.0145 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.0032 | 00.0077 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 00 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.0514 | 0.03550.0719 |

| UFH (NIHSS 14) | ||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 0.2914 | 0.22410.3588 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0.0229 | 0.00630.0575 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 0.016 | 0.00040.0316 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 0 | 00 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 0.064 | 0.0370.1019 |

| Event | Cost per Event ($)* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Likeliest | Minimum | Maximum | |

| |||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 3,003 | 2,402 | 3,604 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2,143 | 1,714 | 2,572 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4,001 | 3,201 | 4,801 |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 3,534 | 2,827 | 4,241 |

| Minor hemorrhage | 1,322 | 1,058 | 1,586 |

| Enoxaparin cost per dose | 26 | 21 | 31 |

| Unfractionated heparin cost per dose | 3 | 2 | 4 |

The average hospital cost with enoxaparin, when taking into account the costs of VTE and bleeding, was lower than with UFH ($422 vs $662, respectively), with a net savings of $240 per patient if enoxaparin was used. The average drug costs, including drug‐administration costs, were higher in the enoxaparin group ($360) compared with the UFH group ($259; difference $101). Nevertheless, the total hospital cost when clinical events and drug costs were considered together, was lower with enoxaparin than UFH. The total hospital costs per patient were $782 in patients receiving prophylaxis with enoxaparin and $922 in patients receiving UFH. Thus, enoxaparin was associated with a total cost‐savings of $140 per patient (Figure 2).

The cost estimates according to the stroke severity score (NIHSS scores <14 vs 14) are described in Table 3. The drug costs were consistent, regardless of stroke severity, for enoxaparin ($360) and for UFH ($259). However, in both treatment groups, the event costs were higher in patients with more severe stroke, compared with less severe stroke. For example, in the enoxaparin group, the event costs were $686 in patients with NIHSS scores 14 and $326 in patients with NIHSS scores <14. Nevertheless, the overall costs (event costs plus drug costs) were lower with enoxaparin compared with UFH, both in patients with less severe and more severe stroke. In fact, the total hospital cost‐savings were greater when enoxaparin was used instead of UFH in patients with more severe stroke (cost‐saving $287 if NIHSS score 14 vs $71 if NIHSS score <14) (Table 3).

| Enoxaparin ($) | UFH ($) | Difference ($ [UFHEnoxaparin]) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| NIHSS score <14 | |||

| Mean event costs per patient | 326 | 497 | 171 |

| Mean drug costs per patient* | 360 | 259 | 101 |

| Total costs | 685 | 756 | 71 |

| NIHSS score 14 | |||

| Mean event costs per patient | 686 | 1,073 | 387 |

| Mean drug costs per patient* | 360 | 259 | 101 |

| Total costs | 1,046 | 1,332 | 287 |

Multiple sensitivity analyses were performed. In the base case univariate sensitivity analysis, individual costs were adjusted by 20% (Table 4). If the cost of DVT increased by 20% (from $3003 to $3604) the difference between the enoxaparin and UFH groups was $187. When the cost of DVT was decreased by 20% to $2402, enoxaparin was still cost‐saving, with a difference of $94. For each of the individual cost parameters that were varied (DVT, PE, intracranial hemorrhage, major extracranial hemorrhage, and minor hemorrhage), enoxaparin was always less costly than UFH. Subsequent sensitivity analyses were performed (not shown) where cost parameters were varied by 5%, 10%, 15%, 30%, and 40%. Enoxaparin remained less costly than UFH in all cases.

| Event | Baseline Cost Input ($) | +20% Cost Input ($) | +20% Difference ($ [UFH Enoxaparin]) (% Change) | 20% Cost Input ($) | 20% Difference ($ [UFH Enoxaparin]) (% Change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Deep‐vein thrombosis | 3,003 | 3,604 | 187 (33) | 2,402 | 94 (33) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2,143 | 2,572 | 144 (2.5) | 1,714 | 137 (2.5) |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 4,001 | 4,801 | 142 (1.3) | 3,201 | 138 (1.3) |

| Major extracranial hemorrhage | 3,534 | 4,241 | 134 (4.0) | 2,827 | 146 (4.0) |

| Minor hemorrhage | 1,322 | 1,586 | 142 (1.3) | 1,058 | 138 (1.3) |

A multivariate analysis was performed using a Monte Carlo simulation in TreeAge Pro (Figure 3). When all parameters were varied simultaneously (by 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 30%, and 40%) and the differences in costs between the enoxaparin and UFH groups were measured and plotted, the mean (standard deviation) difference between enoxaparin and UFH prophylaxis was $140 ($79) (Figure 3). Figure 4 shows a graphical presentation of the sensitivity analysis results for event probabilities and costs. Differences in enoxaparin drug costs, hospital costs for DVT, and probability of DVT for patients on enoxaparin are the factors that have the greatest effect on the overall cost.

Finally, an additional scenario was performed using a published ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE, due to the fact that not all VTE events in the real‐world present with symptoms prompting treatment. Quinlan et al. determined a ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE of 5 for total hip replacement patients and of 21 for total knee replacement patients.28 Although derived from different patient populations who received different anticoagulants, we utilized the symptomatic event rates from the pooled studies to recalculate cost differences between enoxaparin and UFH in acute ischemic stroke. Using only symptomatic event rates, based on the 21:1 ratio in patients undergoing total knee replacement, the total cost for enoxaparin was $485 compared to $386 for UFH. Similar results were found based on the 5:1 ratio in patients with total hip replacement (enoxaparin $532 vs $472 for UFH). This was the only scenario where the higher drug cost of prophylaxis with enoxaparin was not completely offset by the reduction in events compared to UFH, likely due to the smaller difference in event rates once examining only symptomatic VTE.

DISCUSSION

This analysis demonstrates that, from the hospital perspective, enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously once‐daily is associated with lower total hospital costs and is more cost‐effective than twice‐daily UFH 5000 U subcutaneously for the prevention of VTE in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Despite higher drug‐acquisition costs, enoxaparin was associated with total cost‐savings of $140 per patient. This is due to the lower event rates with enoxaparin compared with UFH.

Previous studies, using hospital or payer information, have shown that VTE prophylaxis is more cost‐effective compared with no prophylaxis. In terms of the different VTE prophylaxis regimens, enoxaparin represents a more cost‐effective option in comparison with UFH19, 21, 2932 and also when compared with fondaparinux.21, 33 When comparing the results between different trials, it should be noted that previous analyses were mainly modeled on the Prophylaxis in Medical Patients with Enoxaparin (MEDENOX) study, which was performed in general medical patients and reported a VTE rate of 5.5%.6 However, patients with acute ischemic stroke are at a higher risk of VTE, with a 10% incidence of VTE reported in the PREVAIL study.14 Furthermore, twice‐daily rather than three‐timesdaily administration of UFH was used in the PREVAIL study, based on the current practice patterns seen during the PREVAIL trial design.

A recent retrospective analysis of transactional billing records demonstrated that, despite higher mean costs of anticoagulation therapy, the mean, total, adjusted direct hospital costs were lower with LMWH thromboprophylaxis compared with UFH ($7358 vs $8680, respectively; difference $1322; P < 0.001).21 A previous study by Burleigh and colleagues based on hospital discharge information extracted from both medical and surgical patients, has a sub‐analysis in patients with stroke. In these patients also, the total costs were lower for enoxaparin compared with UFH ($8608 vs $8911, respectively; difference $303).29 In the Burleigh study, drug costs and total discharge costs (eg, room and board, laboratory, and diagnostic imaging) were derived from drug charges and total charges, and were converted to estimated costs using cost‐to‐charge methods, so the absolute figures are not directly comparable with the current analysis.

This study adds to current literature by using data from a prospective study to analyze the hospital costs of VTE prophylaxis in stroke patients. The current study also provides a valuable cost‐analysis regarding a specific subgroup of medical patients at particularly high risk of VTE, and provides an economic comparison among stroke patients with NIHSS scores of <14 versus 14. In the PREVAIL study, despite a 2‐fold higher incidence of VTE in patients with more severe stroke (16.3% vs 8.3%), a similar reduction in VTE risk was observed with enoxaparin versus UFH in patients with NIHSS scores of 14 (odds ratio = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.37‐0.84; P = 0.0036) and <14 (odds ratio = 0.46; 95% CI = 0.27‐0.78; P = 0.0043).14 Enoxaparin was shown to be cost‐saving relative to UFH in both patient groups and, in particular, in patients with more severe stroke.

Potential limitations of the current analysis include the applicability of the figures obtained from the highly selected clinical trial population to real‐world clinical practice, and the fact that it is difficult to match cost estimates to trial data definitions. For example, this analysis was conducted with a comparator of twice‐daily UFH (as opposed to three‐timesdaily) which may be used in the real‐world setting and may have resulted in the increased number of events in the UFH group seen in the PREVAIL study. Due to a variety of differences between real‐world practice patterns and the PREVAIL clinical trial, we can only speculate as to the true cost‐consequences of utilizing enoxaparin versus UFH.

Furthermore, the original model did not include a sub‐analysis regarding the rates and, therefore, costs of proximal/symptomatic VTE. In the primary study of PREVAIL, the rates of symptomatic DVT were 1 in 666 patients (<1%) for enoxaparin and 4 in 669 patients (1%) for UFH, whereas the rates of proximal DVT were 30 in 666 patients (5%) and 64 in 669 patients (10%), respectively. Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the impact of lower rates of both DVT and PE (up to 40%), and the differences between groups were found to be robust. However, it is important to note that overall costs for both groups may have been increased through the inclusion of asymptomatic costs, with a more distinct separation of these costs making for a good follow‐up study. In a similar cost‐analysis we performed based on the PREVAIL study, which assessed the cost to the payer, we included an analysis of costs according to 3 different VTE definitions: the PREVAIL VTE definition (as in the current study); a definition of major VTE (PE, symptomatic DVT, and asymptomatic proximal DVT); and primary endpoints recommended by the European Medicines Agency Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use for studies on VTE (proximal DVT, nonfatal PE, and all‐cause mortality). We found similar results irrespective of clinical event definitions.34 In an additional model scenario using a published ratio of asymptomatic DVT to symptomatic VTE,28 the higher drug cost of prophylaxis with enoxaparin was not completely offset by the reduction in events compared to UFH. This was likely due to the smaller difference in event rates once examining only symptomatic VTE. This scenario was limited by the fact that the ratio was derived from different patient populations receiving different anticoagulants than stroke patients.

In conclusion, data from this analysis adds to the evidence that, from the hospital perspective, the higher drug cost of enoxaparin is offset by the economic consequences of the events avoided as compared with UFH for the prevention of VTE following acute ischemic stroke, particularly in patients with severe stroke.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Aylin Lee from I3 Innovus for her contribution to this study. The authors also acknowledge Min Chen for her assistance in statistical analysis, and Essy Mozaffari for his contribution to this study.

- .Venous thromboembolism: disease burden, outcomes and risk factors.J Thromb Haemost.2005;3:1611–1617.

- .The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management.J Thromb Thrombolysis.2006;21:23–29.

- ,,, et al.Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based study.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1245–1248.

- ,,,,,.Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based case‐control study.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:809–815.

- ,.A safety analysis of thromboprophylaxis in acute medical illness.Thromb Haemost.2003;89:590–591.

- ,,,,.Quantification of risk factors for venous thromboembolism: a preliminary study for the development of a risk assessment tool.Haematologica.2003;88:1410–1421.

- ,.Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in acute hemorrhagic and thromboembolic stroke.Am J Phys Med Rehabil.2003;82:364–369.

- ,,,.Thromboprophylaxis rates in US medical centers: success or failure?J Thromb Haemost.2007;5:1610–1616.

- ,,,.Complications after acute stroke.Stroke.1996;27:415–420.

- ,,,.Venous thromboembolism after acute stroke.Stroke.2001;32:262–267.

- ,,,,,.Enoxaparin vs heparin for prevention of deep‐vein thrombosis in acute ischaemic stroke: a randomized, double‐blind study.Acta Neurol Scand.2002;106:84–92.

- ,,.Low‐molecular‐weight heparins or heparinoids versus standard unfractionated heparin for acute ischaemic stroke.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2008;(3):CD000119.

- ,,, et al;for the PROTECT Trial Group.Prophylaxis of thrombotic and embolic events in acute ischemic stroke with the low‐molecular‐weight heparin certoparin: results of the PROTECT Trial.Stroke.2006;37:139–144.

- ,,, et al;for the PREVAIL Investigators.The efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after acute ischaemic stroke (PREVAIL study): an open‐label randomised comparison.Lancet.2007;369:1347–1355.

- ,,, et al;for the American College of Chest Physicians.Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed).Chest.2008;133(6 suppl):381S–453S.

- ,,,,;for the American College of Chest Physicians.Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed).Chest.2008;133(6 suppl):630S–669S.

- ,,,.Management of acute proximal deep vein thrombosis: pharmacoeconomic evaluation of outpatient treatment with enoxaparin vs inpatient treatment with unfractionated heparin.Chest.2002;122:108–114.

- ,.Economic evaluation of enoxaparin as prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in seriously ill medical patients: a US perspective.Am J Manag Care.2002;8:1082–1088.

- ,,,.Cost effectiveness of thromboprophylaxis with a low‐molecular‐weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin in acutely ill medical inpatients.Am J Manag Care.2004;10:632–642.

- ,,, et al.Cost effectiveness of enoxaparin as prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic complications in acutely ill medical inpatients: modelling study from the hospital perspective in Germany.Pharmacoeconomics.2006;24:571–591.

- ,,,,.Hospital‐based costs associated with venous thromboembolism prophylaxis regimens.J Thromb Thrombolysis.2010;29:449–458.

- ,,, et al;for the ENDORSE Investigators.Venous thromboembolism risk and prophylaxis in the acute hospital care setting (ENDORSE study): a multinational cross‐sectional study.Lancet.2008;371:387–394.

- ,,, et al;for the IMPROVE Investigators.Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients: findings from the International Medical Prevention Registry on Venous Thromboembolism.Chest.2007;132:936–945.

- United States Department of Health August 2008. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/vtguide/. Accessed August 18,2010.

- ,,,.Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after acute ischemic stroke: rationale, design, and methods of an open‐label, randomized, parallel‐group multicenter trial.J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis.2005;14:95–100.

- ,,,,,.Association between asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by venography and symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing elective hip or knee surgery.J Thromb Haemost.2007;5:1438–1443.

- ,,, et al.Thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients at risk for venous thromboembolism.Am J Health Syst Pharm.2006;63(20 suppl 6):S23–S29.

- ,,,.Comparison of the two‐year outcomes and costs of prophylaxis in medical patients at risk of venous thromboembolism.Thromb Haemost.2008;100:810–820.

- ,,,,,.Cost for inpatient care of venous thrombosis: a trial of enoxaparin vs standard heparin.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3160–3165.

- ,,,.Economic evaluation of enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients.Pharm World Sci.2004;26:214–220.

- ,,,,.Total hospital‐based costs of enoxaparin or fondaparinux prophylaxis in patients at risk of venous thromboembolism [abstract]. Presented at the Chest 2008 Annual Meeting; October 25–30,2008; Philadelphia, PA.

- ,,,,.Economic impact of enoxaparin after acute ischemic stroke based on PREVAIL.Clin Appl Thromb Hemost.2011;17:150–157.

- .Venous thromboembolism: disease burden, outcomes and risk factors.J Thromb Haemost.2005;3:1611–1617.

- .The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management.J Thromb Thrombolysis.2006;21:23–29.

- ,,, et al.Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based study.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1245–1248.

- ,,,,,.Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based case‐control study.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:809–815.

- ,.A safety analysis of thromboprophylaxis in acute medical illness.Thromb Haemost.2003;89:590–591.

- ,,,,.Quantification of risk factors for venous thromboembolism: a preliminary study for the development of a risk assessment tool.Haematologica.2003;88:1410–1421.

- ,.Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in acute hemorrhagic and thromboembolic stroke.Am J Phys Med Rehabil.2003;82:364–369.

- ,,,.Thromboprophylaxis rates in US medical centers: success or failure?J Thromb Haemost.2007;5:1610–1616.

- ,,,.Complications after acute stroke.Stroke.1996;27:415–420.

- ,,,.Venous thromboembolism after acute stroke.Stroke.2001;32:262–267.

- ,,,,,.Enoxaparin vs heparin for prevention of deep‐vein thrombosis in acute ischaemic stroke: a randomized, double‐blind study.Acta Neurol Scand.2002;106:84–92.

- ,,.Low‐molecular‐weight heparins or heparinoids versus standard unfractionated heparin for acute ischaemic stroke.Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2008;(3):CD000119.

- ,,, et al;for the PROTECT Trial Group.Prophylaxis of thrombotic and embolic events in acute ischemic stroke with the low‐molecular‐weight heparin certoparin: results of the PROTECT Trial.Stroke.2006;37:139–144.

- ,,, et al;for the PREVAIL Investigators.The efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after acute ischaemic stroke (PREVAIL study): an open‐label randomised comparison.Lancet.2007;369:1347–1355.

- ,,, et al;for the American College of Chest Physicians.Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed).Chest.2008;133(6 suppl):381S–453S.

- ,,,,;for the American College of Chest Physicians.Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed).Chest.2008;133(6 suppl):630S–669S.