User login

For Most With Diabetes, Revascularization Can Wait

ORLANDO – Virtually no patients with type 2 diabetes and documented coronary artery disease and coronary ischemia benefit from immediate coronary revascularization, as long as they receive intensive medical management, based on the outcomes of more than 1,000 patients who were randomized to the deferred revascularization arm of the BARI 2D trial.

The only possible exception to this approach are the rare patients who initially present with severe or unstable angina and proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery disease, a small group accounting for just 2% of these patients, Dr. Ronald J. Krone said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. Even in this small subgroup with the worst chance of avoiding revascularization, eventual coronary bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is not an absolute. Among the 21 patients with this initial presentation at study entry (of the total 1,192 who were randomized to the deferred revascularization arm), 50% continued to avoid revascularization 6 months later, and 29% had still not undergone revascularization 5 years after the study began, said Dr. Krone, an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

"What it comes down to is that there is no group you can identify up front" that unequivocally needs immediate revascularization," Dr. Krone said in an interview. "We could not identify patients who will need revascularization at a high enough rate to warrant initial revascularization, with the possible exception" of the small proximal LAD and severe angina subgroup. "Even in the worst patients, you can intervene later. We used to be afraid that if we didn’t [revascularize these patients] they would drop dead or have a big myocardial infarction, but that didn’t happen. These results give us confidence that you don’t need to intervene on every tight lesion."

Today, a physician or surgeon can’t say "’I have to revascularize, because it’s the best I can do’" for these patients. Instead, the onus is to intensively treat these patients medically, especially patients with diabetes, Dr. Krone said. This strategy includes optimal control of hypertension, lipids, glycemia, and intensive lifestyle intervention with exercise, diet, and smoking cessation.

The analysis he presented focused on patients enrolled in the BARI 2D (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation in Type 2 Diabetes), which randomized a total of 2,368 patients with diabetes and documented coronary ischemia and stenosis suitable for an elective intervention. The researchers put all these patients on an intensive medical management regimen, and also randomized them to either immediate or deferred revascularization. The study’s primary results showed absolutely identical 5-year outcomes in the two groups, with a mortality rate of 12% in each arm of the study, and a combined rate of death, MI, or stroke of 23% in the immediate revascularization patients and 24% in those with deferred intervention (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2503-15).

Among the 1,192 patients in the deferred subgroup, 13% required PCI or bypass surgery after 6 months, and 40% needed revascularization after 5 years of follow-up. Within the group who eventually had revascularization, 47% required it for worsening angina, 23% because of an acute coronary syndrome event, 18% for worsening ischemia, 6% for progression of their coronary disease, and the remaining 6% for another reason. The current analysis aimed to determine whether "we can identify patients with such a high likelihood of needing revascularization that it need not be deferred," Dr. Krone said.

The average age of the patients in the deferred revascularization group was 62 years; 30% were women, 28% were on insulin treatment, 17% had a left ventricular ejection fraction below 50%, and 13% had proximal LAD coronary disease. Their average duration of type 2 diabetes was 11 years.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, and nationality identified five factors that were linked with a significantly increased rate of revascularization after 6 months: class III or IV stable angina, unstable angina, a systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg or less, a blood triglyceride level of 100 mg/dL or less, and proximal LAD disease. These factors were linked with anywhere from a 3.8-fold increased rate of revascularization (in patients with systolic hypotension, compared with patients with a systolic pressure greater than 100 mm Hg) to a 75% increased rate (in patients with proximal LAD disease, compared with those without LAD disease). However, none of these increased rates appeared to justify performing routine, upfront revascularization.

The 5-year multivariate analysis produced similar results. It identified nine baseline factors that each significantly linked with a significantly increased rate of revascularization during 5-year follow-up: class I or II stable angina, class III or IV stable angina, unstable angina, systolic blood pressure of 101-120 mm Hg, a systolic pressure of 100 mm HG or less, a blood triglyceride level of 100 mg/dL or greater, proximal LAD disease, having two diseased coronary regions, or having three diseased coronary regions. The increased rates associated with these features ranged from a 90% increased revascularization rate (in patients with class III or IV stable angina, compared with patients without angina), to a 28% increased revascularization rate (in patients with class I or II stable angina at baseline). Again, none of these increased rates appeared to justify uniform, upfront revascularization, Dr. Krone said.

The sole exception to this approach might possibly be the small number of patients who initially presented with both proximal LAD disease and either class III or IV stable angina or unstable angina, because eventually over 5 years 71% of these patients underwent revascularization. But these patients constituted only 2% of the total group studied, Dr. Krone noted. In general, more severe angina or stenosis was uncommon in these patients: Some 41% had no angina and 45% had class I or II angina at baseline, and 87% were free of proximal LAD disease at baseline.

Dr. Krone said that he had no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Virtually no patients with type 2 diabetes and documented coronary artery disease and coronary ischemia benefit from immediate coronary revascularization, as long as they receive intensive medical management, based on the outcomes of more than 1,000 patients who were randomized to the deferred revascularization arm of the BARI 2D trial.

The only possible exception to this approach are the rare patients who initially present with severe or unstable angina and proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery disease, a small group accounting for just 2% of these patients, Dr. Ronald J. Krone said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. Even in this small subgroup with the worst chance of avoiding revascularization, eventual coronary bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is not an absolute. Among the 21 patients with this initial presentation at study entry (of the total 1,192 who were randomized to the deferred revascularization arm), 50% continued to avoid revascularization 6 months later, and 29% had still not undergone revascularization 5 years after the study began, said Dr. Krone, an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

"What it comes down to is that there is no group you can identify up front" that unequivocally needs immediate revascularization," Dr. Krone said in an interview. "We could not identify patients who will need revascularization at a high enough rate to warrant initial revascularization, with the possible exception" of the small proximal LAD and severe angina subgroup. "Even in the worst patients, you can intervene later. We used to be afraid that if we didn’t [revascularize these patients] they would drop dead or have a big myocardial infarction, but that didn’t happen. These results give us confidence that you don’t need to intervene on every tight lesion."

Today, a physician or surgeon can’t say "’I have to revascularize, because it’s the best I can do’" for these patients. Instead, the onus is to intensively treat these patients medically, especially patients with diabetes, Dr. Krone said. This strategy includes optimal control of hypertension, lipids, glycemia, and intensive lifestyle intervention with exercise, diet, and smoking cessation.

The analysis he presented focused on patients enrolled in the BARI 2D (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation in Type 2 Diabetes), which randomized a total of 2,368 patients with diabetes and documented coronary ischemia and stenosis suitable for an elective intervention. The researchers put all these patients on an intensive medical management regimen, and also randomized them to either immediate or deferred revascularization. The study’s primary results showed absolutely identical 5-year outcomes in the two groups, with a mortality rate of 12% in each arm of the study, and a combined rate of death, MI, or stroke of 23% in the immediate revascularization patients and 24% in those with deferred intervention (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2503-15).

Among the 1,192 patients in the deferred subgroup, 13% required PCI or bypass surgery after 6 months, and 40% needed revascularization after 5 years of follow-up. Within the group who eventually had revascularization, 47% required it for worsening angina, 23% because of an acute coronary syndrome event, 18% for worsening ischemia, 6% for progression of their coronary disease, and the remaining 6% for another reason. The current analysis aimed to determine whether "we can identify patients with such a high likelihood of needing revascularization that it need not be deferred," Dr. Krone said.

The average age of the patients in the deferred revascularization group was 62 years; 30% were women, 28% were on insulin treatment, 17% had a left ventricular ejection fraction below 50%, and 13% had proximal LAD coronary disease. Their average duration of type 2 diabetes was 11 years.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, and nationality identified five factors that were linked with a significantly increased rate of revascularization after 6 months: class III or IV stable angina, unstable angina, a systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg or less, a blood triglyceride level of 100 mg/dL or less, and proximal LAD disease. These factors were linked with anywhere from a 3.8-fold increased rate of revascularization (in patients with systolic hypotension, compared with patients with a systolic pressure greater than 100 mm Hg) to a 75% increased rate (in patients with proximal LAD disease, compared with those without LAD disease). However, none of these increased rates appeared to justify performing routine, upfront revascularization.

The 5-year multivariate analysis produced similar results. It identified nine baseline factors that each significantly linked with a significantly increased rate of revascularization during 5-year follow-up: class I or II stable angina, class III or IV stable angina, unstable angina, systolic blood pressure of 101-120 mm Hg, a systolic pressure of 100 mm HG or less, a blood triglyceride level of 100 mg/dL or greater, proximal LAD disease, having two diseased coronary regions, or having three diseased coronary regions. The increased rates associated with these features ranged from a 90% increased revascularization rate (in patients with class III or IV stable angina, compared with patients without angina), to a 28% increased revascularization rate (in patients with class I or II stable angina at baseline). Again, none of these increased rates appeared to justify uniform, upfront revascularization, Dr. Krone said.

The sole exception to this approach might possibly be the small number of patients who initially presented with both proximal LAD disease and either class III or IV stable angina or unstable angina, because eventually over 5 years 71% of these patients underwent revascularization. But these patients constituted only 2% of the total group studied, Dr. Krone noted. In general, more severe angina or stenosis was uncommon in these patients: Some 41% had no angina and 45% had class I or II angina at baseline, and 87% were free of proximal LAD disease at baseline.

Dr. Krone said that he had no disclosures.

ORLANDO – Virtually no patients with type 2 diabetes and documented coronary artery disease and coronary ischemia benefit from immediate coronary revascularization, as long as they receive intensive medical management, based on the outcomes of more than 1,000 patients who were randomized to the deferred revascularization arm of the BARI 2D trial.

The only possible exception to this approach are the rare patients who initially present with severe or unstable angina and proximal left anterior descending (LAD) artery disease, a small group accounting for just 2% of these patients, Dr. Ronald J. Krone said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Heart Association. Even in this small subgroup with the worst chance of avoiding revascularization, eventual coronary bypass surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is not an absolute. Among the 21 patients with this initial presentation at study entry (of the total 1,192 who were randomized to the deferred revascularization arm), 50% continued to avoid revascularization 6 months later, and 29% had still not undergone revascularization 5 years after the study began, said Dr. Krone, an interventional cardiologist and professor of medicine at Washington University, St. Louis.

"What it comes down to is that there is no group you can identify up front" that unequivocally needs immediate revascularization," Dr. Krone said in an interview. "We could not identify patients who will need revascularization at a high enough rate to warrant initial revascularization, with the possible exception" of the small proximal LAD and severe angina subgroup. "Even in the worst patients, you can intervene later. We used to be afraid that if we didn’t [revascularize these patients] they would drop dead or have a big myocardial infarction, but that didn’t happen. These results give us confidence that you don’t need to intervene on every tight lesion."

Today, a physician or surgeon can’t say "’I have to revascularize, because it’s the best I can do’" for these patients. Instead, the onus is to intensively treat these patients medically, especially patients with diabetes, Dr. Krone said. This strategy includes optimal control of hypertension, lipids, glycemia, and intensive lifestyle intervention with exercise, diet, and smoking cessation.

The analysis he presented focused on patients enrolled in the BARI 2D (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation in Type 2 Diabetes), which randomized a total of 2,368 patients with diabetes and documented coronary ischemia and stenosis suitable for an elective intervention. The researchers put all these patients on an intensive medical management regimen, and also randomized them to either immediate or deferred revascularization. The study’s primary results showed absolutely identical 5-year outcomes in the two groups, with a mortality rate of 12% in each arm of the study, and a combined rate of death, MI, or stroke of 23% in the immediate revascularization patients and 24% in those with deferred intervention (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2503-15).

Among the 1,192 patients in the deferred subgroup, 13% required PCI or bypass surgery after 6 months, and 40% needed revascularization after 5 years of follow-up. Within the group who eventually had revascularization, 47% required it for worsening angina, 23% because of an acute coronary syndrome event, 18% for worsening ischemia, 6% for progression of their coronary disease, and the remaining 6% for another reason. The current analysis aimed to determine whether "we can identify patients with such a high likelihood of needing revascularization that it need not be deferred," Dr. Krone said.

The average age of the patients in the deferred revascularization group was 62 years; 30% were women, 28% were on insulin treatment, 17% had a left ventricular ejection fraction below 50%, and 13% had proximal LAD coronary disease. Their average duration of type 2 diabetes was 11 years.

A multivariate analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, and nationality identified five factors that were linked with a significantly increased rate of revascularization after 6 months: class III or IV stable angina, unstable angina, a systolic blood pressure of 100 mm Hg or less, a blood triglyceride level of 100 mg/dL or less, and proximal LAD disease. These factors were linked with anywhere from a 3.8-fold increased rate of revascularization (in patients with systolic hypotension, compared with patients with a systolic pressure greater than 100 mm Hg) to a 75% increased rate (in patients with proximal LAD disease, compared with those without LAD disease). However, none of these increased rates appeared to justify performing routine, upfront revascularization.

The 5-year multivariate analysis produced similar results. It identified nine baseline factors that each significantly linked with a significantly increased rate of revascularization during 5-year follow-up: class I or II stable angina, class III or IV stable angina, unstable angina, systolic blood pressure of 101-120 mm Hg, a systolic pressure of 100 mm HG or less, a blood triglyceride level of 100 mg/dL or greater, proximal LAD disease, having two diseased coronary regions, or having three diseased coronary regions. The increased rates associated with these features ranged from a 90% increased revascularization rate (in patients with class III or IV stable angina, compared with patients without angina), to a 28% increased revascularization rate (in patients with class I or II stable angina at baseline). Again, none of these increased rates appeared to justify uniform, upfront revascularization, Dr. Krone said.

The sole exception to this approach might possibly be the small number of patients who initially presented with both proximal LAD disease and either class III or IV stable angina or unstable angina, because eventually over 5 years 71% of these patients underwent revascularization. But these patients constituted only 2% of the total group studied, Dr. Krone noted. In general, more severe angina or stenosis was uncommon in these patients: Some 41% had no angina and 45% had class I or II angina at baseline, and 87% were free of proximal LAD disease at baseline.

Dr. Krone said that he had no disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Few patients with diabetes and documented ischemic coronary disease suitable for elective revascularization have features that predict a high risk for eventually requiring a procedure during the subsequent 5 years. The only possible exception is the 2% of patients with both proximal LAD coronary disease and severe or unstable angina at baseline, who had a 71% revascularization rate.

Data Source: A subgroup analysis of the BARI 2D study, which randomized 2,368 patients with type 2 diabetes and documented ischemic coronary disease suitable for elective revascularization to an immediate or deferred procedure. The new analysis focused on 1,192 patients initially randomized to the delayed revascularization arm.

Disclosures: Dr. Krone said that he had no disclosures.

JAK Inhibitor Ruxolitinib Wins First FDA Approval in Myelofibrosis

In a much-anticipated double milestone, the Food and Drug Administration has approved ruxolitinib for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis.

Ruxolitinib, an orphan drug to be marketed as Jakafi by Incyte Corp., becomes the first agent to be approved for the rare blood disease. The indication covers patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF, according to a statement from Wilmington, Del.–based Incyte.

The FDA decision also makes ruxolitinib the first approved agent in a new class of drugs called JAK (Janus-associated kinase) inhibitors. Deregulation of signaling in the JAK pathway is believed to be associated with the enlarged spleen and other symptoms of myelofibrosis. Ruxolitinib inhibits the tyrosine kinases JAK1 and JAK2, which are suspected of being up-regulated in various inflammatory disorders and malignancies.

"Jakafi represents another example of an increasing trend in oncology where a detailed scientific understanding of the mechanisms of a disease allows a drug to be directed toward specific molecular pathways," Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the agency’s announcement.

"The clinical trials leading to this approval focused on problems that patients with myelofibrosis commonly encounter, including enlarged spleens and pain," he noted.

In the pivotal phase III COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II trials, ruxolitinib produced substantial symptom relief in patients who were resistant or refractory to available myelofibrosis therapy or ineligible for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. All 528 patients in these studies had enlarged spleens (splenomegaly) and other disease-related symptoms. They were assigned to treatment with ruxolitinib, placebo, or best available therapy (usually hydroxyurea or glucocorticoids).

More patients on ruxolitinib had a greater-than-35% reduction in spleen size, compared with those given the alternatives, the FDA noted. Similarly, patients on ruxolitinib were more likely to have a more-than-50% reduction in MF-related symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, night sweats, itching, and bone or muscle pain, compared with placebo.

The Incyte announcement noted that 41.9% of patients who were treated with ruxolitinib in the COMFORT-I trial had a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume at 24 weeks, compared with 0.7% of patients taking placebo (P less than 0.0001). The median time to response was less than 4 weeks.

In the COMFORT-II trial, 28.5% of patients who were treated with ruxolitinib had a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume at 48 weeks, compared with none of the patients in the best available therapy arm, Incyte said. COMFORT-II was conducted by Novartis, which is collaborating with Incyte outside the United States.

Incyte said that the ruxolitinib dosage should be adjusted based on safety and efficacy. The recommended starting dose of ruxolitinib for most patients of 15 mg or 20 mg given orally twice daily based on the patient’s platelet count. A blood cell count must be performed before initiation of therapy, the company said, and complete blood counts should be monitored every 2-4 weeks until doses are stabilized.

Thrombocytopenia, anemia, fatigue, diarrhea, dyspnea, headache, dizziness, and nausea were the most common side effects, according to the FDA.

In a much-anticipated double milestone, the Food and Drug Administration has approved ruxolitinib for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis.

Ruxolitinib, an orphan drug to be marketed as Jakafi by Incyte Corp., becomes the first agent to be approved for the rare blood disease. The indication covers patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF, according to a statement from Wilmington, Del.–based Incyte.

The FDA decision also makes ruxolitinib the first approved agent in a new class of drugs called JAK (Janus-associated kinase) inhibitors. Deregulation of signaling in the JAK pathway is believed to be associated with the enlarged spleen and other symptoms of myelofibrosis. Ruxolitinib inhibits the tyrosine kinases JAK1 and JAK2, which are suspected of being up-regulated in various inflammatory disorders and malignancies.

"Jakafi represents another example of an increasing trend in oncology where a detailed scientific understanding of the mechanisms of a disease allows a drug to be directed toward specific molecular pathways," Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the agency’s announcement.

"The clinical trials leading to this approval focused on problems that patients with myelofibrosis commonly encounter, including enlarged spleens and pain," he noted.

In the pivotal phase III COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II trials, ruxolitinib produced substantial symptom relief in patients who were resistant or refractory to available myelofibrosis therapy or ineligible for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. All 528 patients in these studies had enlarged spleens (splenomegaly) and other disease-related symptoms. They were assigned to treatment with ruxolitinib, placebo, or best available therapy (usually hydroxyurea or glucocorticoids).

More patients on ruxolitinib had a greater-than-35% reduction in spleen size, compared with those given the alternatives, the FDA noted. Similarly, patients on ruxolitinib were more likely to have a more-than-50% reduction in MF-related symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, night sweats, itching, and bone or muscle pain, compared with placebo.

The Incyte announcement noted that 41.9% of patients who were treated with ruxolitinib in the COMFORT-I trial had a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume at 24 weeks, compared with 0.7% of patients taking placebo (P less than 0.0001). The median time to response was less than 4 weeks.

In the COMFORT-II trial, 28.5% of patients who were treated with ruxolitinib had a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume at 48 weeks, compared with none of the patients in the best available therapy arm, Incyte said. COMFORT-II was conducted by Novartis, which is collaborating with Incyte outside the United States.

Incyte said that the ruxolitinib dosage should be adjusted based on safety and efficacy. The recommended starting dose of ruxolitinib for most patients of 15 mg or 20 mg given orally twice daily based on the patient’s platelet count. A blood cell count must be performed before initiation of therapy, the company said, and complete blood counts should be monitored every 2-4 weeks until doses are stabilized.

Thrombocytopenia, anemia, fatigue, diarrhea, dyspnea, headache, dizziness, and nausea were the most common side effects, according to the FDA.

In a much-anticipated double milestone, the Food and Drug Administration has approved ruxolitinib for treatment of patients with myelofibrosis.

Ruxolitinib, an orphan drug to be marketed as Jakafi by Incyte Corp., becomes the first agent to be approved for the rare blood disease. The indication covers patients with intermediate or high-risk myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF, post-polycythemia vera MF, and post-essential thrombocythemia MF, according to a statement from Wilmington, Del.–based Incyte.

The FDA decision also makes ruxolitinib the first approved agent in a new class of drugs called JAK (Janus-associated kinase) inhibitors. Deregulation of signaling in the JAK pathway is believed to be associated with the enlarged spleen and other symptoms of myelofibrosis. Ruxolitinib inhibits the tyrosine kinases JAK1 and JAK2, which are suspected of being up-regulated in various inflammatory disorders and malignancies.

"Jakafi represents another example of an increasing trend in oncology where a detailed scientific understanding of the mechanisms of a disease allows a drug to be directed toward specific molecular pathways," Dr. Richard Pazdur, director of the Office of Hematology and Oncology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in the agency’s announcement.

"The clinical trials leading to this approval focused on problems that patients with myelofibrosis commonly encounter, including enlarged spleens and pain," he noted.

In the pivotal phase III COMFORT-I and COMFORT-II trials, ruxolitinib produced substantial symptom relief in patients who were resistant or refractory to available myelofibrosis therapy or ineligible for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. All 528 patients in these studies had enlarged spleens (splenomegaly) and other disease-related symptoms. They were assigned to treatment with ruxolitinib, placebo, or best available therapy (usually hydroxyurea or glucocorticoids).

More patients on ruxolitinib had a greater-than-35% reduction in spleen size, compared with those given the alternatives, the FDA noted. Similarly, patients on ruxolitinib were more likely to have a more-than-50% reduction in MF-related symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort, night sweats, itching, and bone or muscle pain, compared with placebo.

The Incyte announcement noted that 41.9% of patients who were treated with ruxolitinib in the COMFORT-I trial had a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume at 24 weeks, compared with 0.7% of patients taking placebo (P less than 0.0001). The median time to response was less than 4 weeks.

In the COMFORT-II trial, 28.5% of patients who were treated with ruxolitinib had a 35% or greater reduction in spleen volume at 48 weeks, compared with none of the patients in the best available therapy arm, Incyte said. COMFORT-II was conducted by Novartis, which is collaborating with Incyte outside the United States.

Incyte said that the ruxolitinib dosage should be adjusted based on safety and efficacy. The recommended starting dose of ruxolitinib for most patients of 15 mg or 20 mg given orally twice daily based on the patient’s platelet count. A blood cell count must be performed before initiation of therapy, the company said, and complete blood counts should be monitored every 2-4 weeks until doses are stabilized.

Thrombocytopenia, anemia, fatigue, diarrhea, dyspnea, headache, dizziness, and nausea were the most common side effects, according to the FDA.

MGMA, ACMPE Name Hospitalist "Physician Executive of the Year"

Modesty comes naturally to IPC The Hospitalist Co. executive Dave Bowman, MD. He shies from the spotlight and seeks to downplay his own accomplishments in favor of talking about the results of those he works with.

That tack got a bit more difficult last month when Dr. Bowman, based in Tucson, Ariz., received the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) and American College of Medical Practice Executives' (ACMPE) "Physician Executive of the Year" award for 2011. It's the second year in a row the honor went to an HM leader; last year's winner was IPC chief executive Adam Singer, MD.

Dr. Bowman was praised both for his professional skills and the heroic role he played providing medical aid in the immediate aftermath of the Jan. 8 shooting in Tucson that left six people dead and injured 13 others, including U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.)

Dr. Bowman tried to downplay the award until it was presented at a conference last month in Las Vegas. "When I step back and look at it from a non-physician-jaundiced view, that was a pretty neat thing. I was very humbled and grateful," he says.

He quickly adds, though, that the award means those he works with are doing their jobs just as exceptionally.

"You have to have a team to take care of people," he says. "If you're a lone wolf, you can do a good job for your 16 patients that day. But what happens when you leave? ... You have to be part of a team to ensure the good work you’re doing is continued."

Dr. Bowman, IPC's executive director in Tucson, has grown his group's practice to more than 75 physicians and non-physician providers. He notes that all of his providers with at least one year of seniority sit on at least one committee at their institution.

But his most sage advice for hospitalist leaders?

"Get involved, be out there," he says. "Take night call because you have two letters after your name that says you can do it. ... Be involved clinically, not just administratively."

Modesty comes naturally to IPC The Hospitalist Co. executive Dave Bowman, MD. He shies from the spotlight and seeks to downplay his own accomplishments in favor of talking about the results of those he works with.

That tack got a bit more difficult last month when Dr. Bowman, based in Tucson, Ariz., received the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) and American College of Medical Practice Executives' (ACMPE) "Physician Executive of the Year" award for 2011. It's the second year in a row the honor went to an HM leader; last year's winner was IPC chief executive Adam Singer, MD.

Dr. Bowman was praised both for his professional skills and the heroic role he played providing medical aid in the immediate aftermath of the Jan. 8 shooting in Tucson that left six people dead and injured 13 others, including U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.)

Dr. Bowman tried to downplay the award until it was presented at a conference last month in Las Vegas. "When I step back and look at it from a non-physician-jaundiced view, that was a pretty neat thing. I was very humbled and grateful," he says.

He quickly adds, though, that the award means those he works with are doing their jobs just as exceptionally.

"You have to have a team to take care of people," he says. "If you're a lone wolf, you can do a good job for your 16 patients that day. But what happens when you leave? ... You have to be part of a team to ensure the good work you’re doing is continued."

Dr. Bowman, IPC's executive director in Tucson, has grown his group's practice to more than 75 physicians and non-physician providers. He notes that all of his providers with at least one year of seniority sit on at least one committee at their institution.

But his most sage advice for hospitalist leaders?

"Get involved, be out there," he says. "Take night call because you have two letters after your name that says you can do it. ... Be involved clinically, not just administratively."

Modesty comes naturally to IPC The Hospitalist Co. executive Dave Bowman, MD. He shies from the spotlight and seeks to downplay his own accomplishments in favor of talking about the results of those he works with.

That tack got a bit more difficult last month when Dr. Bowman, based in Tucson, Ariz., received the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) and American College of Medical Practice Executives' (ACMPE) "Physician Executive of the Year" award for 2011. It's the second year in a row the honor went to an HM leader; last year's winner was IPC chief executive Adam Singer, MD.

Dr. Bowman was praised both for his professional skills and the heroic role he played providing medical aid in the immediate aftermath of the Jan. 8 shooting in Tucson that left six people dead and injured 13 others, including U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords (D-Ariz.)

Dr. Bowman tried to downplay the award until it was presented at a conference last month in Las Vegas. "When I step back and look at it from a non-physician-jaundiced view, that was a pretty neat thing. I was very humbled and grateful," he says.

He quickly adds, though, that the award means those he works with are doing their jobs just as exceptionally.

"You have to have a team to take care of people," he says. "If you're a lone wolf, you can do a good job for your 16 patients that day. But what happens when you leave? ... You have to be part of a team to ensure the good work you’re doing is continued."

Dr. Bowman, IPC's executive director in Tucson, has grown his group's practice to more than 75 physicians and non-physician providers. He notes that all of his providers with at least one year of seniority sit on at least one committee at their institution.

But his most sage advice for hospitalist leaders?

"Get involved, be out there," he says. "Take night call because you have two letters after your name that says you can do it. ... Be involved clinically, not just administratively."

Pediatric Deterioration Risk Score

Thousands of hospitals have implemented rapid response systems in recent years in attempts to reduce mortality outside the intensive care unit (ICU).1 These systems have 2 components, a response arm and an identification arm. The response arm is usually comprised of a multidisciplinary critical care team that responds to calls for urgent assistance outside the ICU; this team is often called a rapid response team or a medical emergency team. The identification arm comes in 2 forms, predictive and detective. Predictive tools estimate a patient's risk of deterioration over time based on factors that are not rapidly changing, such as elements of the patient's history. In contrast, detective tools include highly time‐varying signs of active deterioration, such as vital sign abnormalities.2 To date, most pediatric studies have focused on developing detective tools, including several early warning scores.38

In this study, we sought to identify the characteristics that increase the probability that a hospitalized child will deteriorate, and combine these characteristics into a predictive score. Tools like this may be helpful in identifying and triaging the subset of high‐risk children who should be intensively monitored for early signs of deterioration at the time of admission, as well as in identifying very low‐risk children who, in the absence of other clinical concerns, may be monitored less intensively.

METHODS

Detailed methods, including the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the matching procedures, and a full description of the statistical analysis are provided as an appendix (see Supporting Online Appendix: Supplement to Methods Section in the online version of this article). An abbreviated version follows.

Design

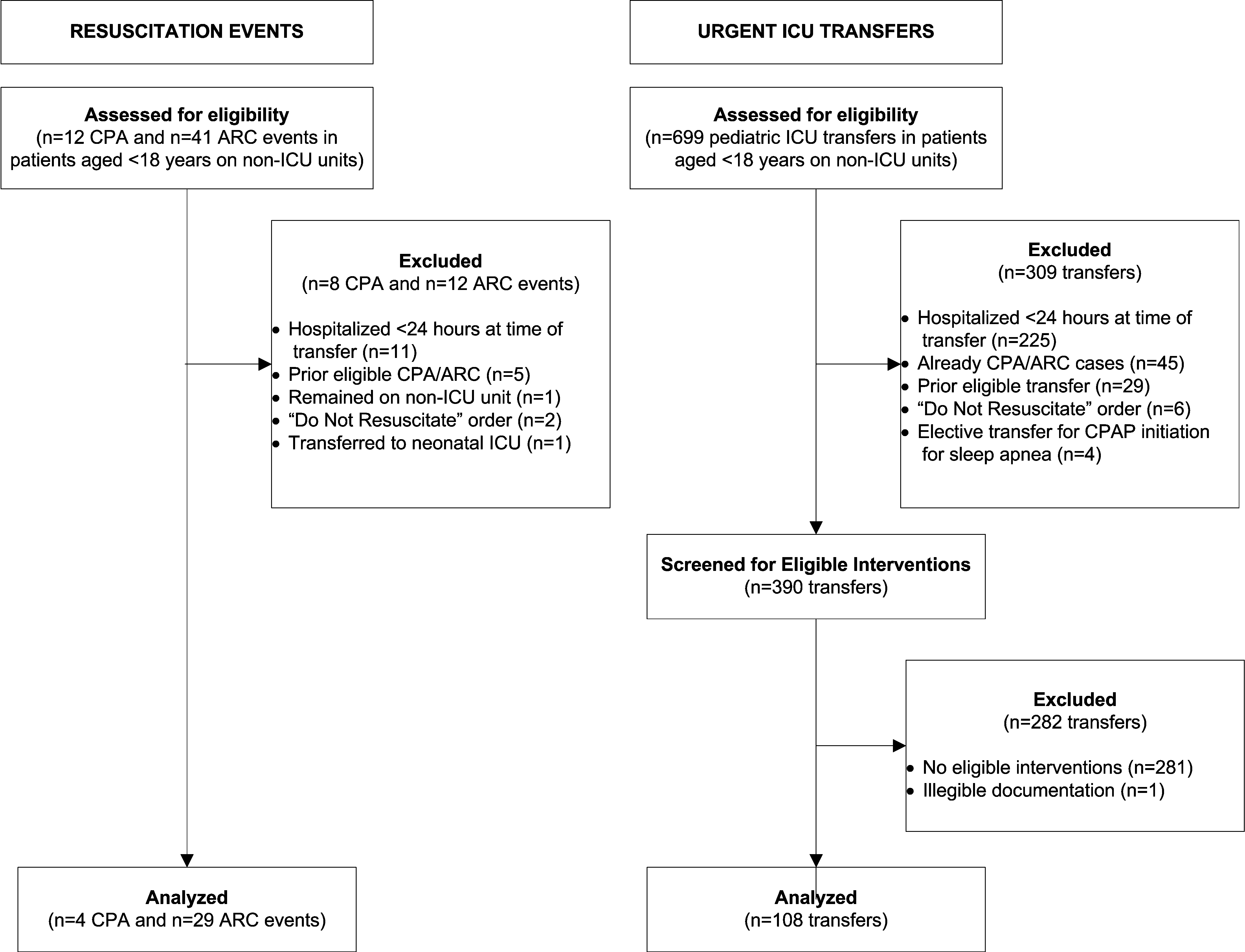

We performed a case‐control study among children, younger than 18 years old, hospitalized for >24 hours between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2008. The case group consisted of children who experienced clinical deterioration, a composite outcome defined as cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA), acute respiratory compromise (ARC), or urgent ICU transfer, while on a non‐ICU unit. ICU transfers were considered urgent if they included at least one of the following outcomes in the 12 hours after transfer: death, CPA, intubation, initiation of noninvasive ventilation, or administration of a vasoactive medication infusion used for the treatment of shock. The control group consisted of a random sample of patients matched 3:1 to cases if they met the criteria of being on a non‐ICU unit at the same time as their matched case.

Variables and Measurements

We collected data on demographics, complex chronic conditions (CCCs), other patient characteristics, and laboratory studies. CCCs were specific diagnoses divided into the following 9 categories according to an established framework: neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematologic/emmmunologic, metabolic, malignancy, and genetic/congenital defects.9 Other patient characteristics evaluated included age, weight‐for‐age, gestational age, history of transplant, time from hospital admission to event, recent ICU stays, administration of total parenteral nutrition, use of a patient‐controlled analgesia pump, and presence of medical devices including central venous lines and enteral tubes (naso‐gastric, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy).

Laboratory studies evaluated included hemoglobin value, white blood cell count, and blood culture drawn in the preceding 72 hours. We included these laboratory studies in this predictive score because we hypothesized that they represented factors that increased a child's risk of deterioration over time, as opposed to signs of acute deterioration that would be more appropriate for a detective score.

Statistical Analysis

We used conditional logistic regression for the bivariable and multivariable analyses to account for the matching. We derived the predictive score using an established method10 in which the regression coefficients for each covariate were divided by the smallest coefficient, and then rounded to the nearest integer, to establish each variable's sub‐score. We grouped the total scores into very low, low, intermediate, and high‐risk groups, calculated overall stratum‐specific likelihood ratios (SSLRs), and estimated stratum‐specific probabilities of deterioration for each group.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

We identified 12 CPAs, 41 ARCs, and 699 urgent ICU transfers during the study period. A total of 141 cases met our strict criteria for inclusion (see Figure in Supporting Online Appendix: Supplement to Methods Section in the online version of this article) among approximately 96,000 admissions during the study period, making the baseline incidence of events (pre‐test probability) approximately 0.15%. The case and control groups were similar in age, sex, and family‐reported race/ethnicity. Cases had been hospitalized longer than controls at the time of their event, were less likely to have been on a surgical service, and were less likely to survive to hospital discharge (Table 1). There was a high prevalence of CCCs among both cases and controls; 78% of cases and 52% of controls had at least 1 CCC.

| Cases (n = 141) | Controls (n = 423) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | P Value | |

| |||

| Type of event | |||

| Cardiopulmonary arrest | 4 (3) | 0 | NA |

| Acute respiratory compromise | 29 (20) | 0 | NA |

| Urgent ICU transfer | 108 (77) | 0 | NA |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 0.34 | ||

| 0‐6 mo | 17 (12) | 62 (15) | |

| 6‐12 mo | 22 (16) | 41 (10) | |

| 1‐4 yr | 34 (24) | 97 (23) | |

| 4‐10 yr | 26 (18) | 78 (18) | |

| 10‐18 yr | 42 (30) | 145 (34) | |

| Sex | 0.70 | ||

| Female | 60 (43) | 188 (44) | |

| Male | 81 (57) | 235 (56) | |

| Race | 0.40 | ||

| White | 69 (49) | 189 (45) | |

| Black/African‐American | 49 (35) | 163 (38) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | |

| Other | 23 (16) | 62 (15) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.53 | ||

| Non‐Hispanic | 127 (90) | 388 (92) | |

| Hispanic | 14 (10) | 33 (8) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Length of stay in days, median (interquartile range) | 7.8 (2.6‐18.2) | 3.9 (1.9‐11.2) | 0.001 |

| Surgical service | 4 (3) | 67 (16) | 0.001 |

| Survived to hospital discharge | 107 (76) | 421 (99.5) | 0.001 |

Unadjusted (Bivariable) Analysis

Results of bivariable analysis are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | OR* | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Complex chronic conditions categories | |||||

| Congenital/genetic | 19 (13) | 21 (5) | 3.0 | 1.6‐5.8 | 0.001 |

| Neuromuscular | 31 (22) | 48 (11) | 2.2 | 1.3‐3.7 | 0.002 |

| Respiratory | 18 (13) | 27 (6) | 2.0 | 1.1‐3.7 | 0.02 |

| Cardiovascular | 15 (10) | 24 (6) | 2.0 | 1.0‐3.9 | 0.05 |

| Metabolic | 5 (3) | 6 (1) | 2.5 | 0.8‐8.2 | 0.13 |

| Gastrointestinal | 10 (7) | 24 (6) | 1.3 | 0.6‐2.7 | 0.54 |

| Renal | 3 (2) | 8 (2) | 1.1 | 0.3‐4.2 | 0.86 |

| Hematology/emmmunodeficiency | 6 (4) | 19 (4) | 0.9 | 0.4‐2.4 | 0.91 |

| Specific conditions | |||||

| Mental retardation | 21 (15) | 25 (6) | 2.7 | 1.5‐4.9 | 0.001 |

| Malignancy | 49 (35) | 90 (21) | 1.9 | 1.3‐2.8 | 0.002 |

| Epilepsy | 22 (15) | 30 (7) | 2.4 | 1.3‐4.3 | 0.004 |

| Cardiac malformations | 14 (10) | 19 (4) | 2.2 | 1.1‐4.4 | 0.02 |

| Chronic respiratory disease arising in the perinatal period | 11 (8) | 15 (4) | 2.2 | 1.0‐4.8 | 0.05 |

| Cerebral palsy | 7 (5) | 13 (3) | 1.7 | 0.6‐4.2 | 0.30 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 (1) | 9 (2) | 0.3 | 0.1‐2.6 | 0.30 |

| Other patient characteristics | |||||

| Time from hospital admission to event 7 days | 74 (52) | 146 (35) | 2.1 | 1.4‐3.1 | 0.001 |

| History of any transplant | 27 (19) | 17 (4) | 5.7 | 2.9‐11.1 | 0.001 |

| Enteral tube | 65 (46) | 102 (24) | 2.6 | 1.8‐3.9 | 0.001 |

| Hospitalized in an intensive care unit during the same admission | 43 (31) | 77 (18) | 2.0 | 1.3‐3.1 | 0.002 |

| Administration of TPN in preceding 24 hr | 26 (18) | 36 (9) | 2.3 | 1.4‐3.9 | 0.002 |

| Administration of an opioid via a patient‐controlled analgesia pump in the preceding 24 hr | 14 (9) | 14 (3) | 3.6 | 1.6‐8.3 | 0.002 |

| Weight‐for‐age 5th percentile | 49 (35) | 94 (22) | 1.9 | 1.2‐2.9 | 0.003 |

| Central venous line | 55 (39) | 113 (27) | 1.8 | 1.2‐2.7 | 0.005 |

| Age 1 yr | 39 (28) | 103 (24) | 1.2 | 0.8‐1.9 | 0.42 |

| Gestational age 37 wk or documentation of prematurity | 21 (15) | 60 (14) | 1.1 | 0.6‐1.8 | 0.84 |

| Laboratory studies | |||||

| Hemoglobin in preceding 72 hr | |||||

| Not tested | 28 (20) | 190 (45) | 1.0 | [reference] | |

| 10 g/dL | 42 (30) | 144 (34) | 2.0 | 1.2‐3.5 | 0.01 |

| 10 g/dL | 71 (50) | 89 (21) | 5.6 | 3.3‐9.5 | 0.001 |

| White blood cell count in preceding 72 hr | |||||

| Not tested | 28 (20) | 190 (45) | 1.0 | [reference] | |

| 5000 to 15,000/l | 45 (32) | 131 (31) | 2.4 | 1.4‐4.1 | 0.001 |

| 15,000/l | 19 (13) | 25 (6) | 5.7 | 2.7‐12.0 | 0.001 |

| 5000/l | 49 (35) | 77 (18) | 4.5 | 2.6‐7.8 | 0.001 |

| Blood culture drawn in preceding 72 hr | 78 (55) | 85 (20) | 5.2 | 3.3‐8.1 | 0.001 |

Adjusted (Multivariable) Analysis

The multivariable conditional logistic regression model included 7 independent risk factors for deterioration (Table 3): age 1 year, epilepsy, congenital/genetic defects, history of transplant, enteral tubes, hemoglobin 10 g/dL, and blood culture drawn in the preceding 72 hours.

| Predictor | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value | Regression Coefficient (95% CI) | Score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age 1 yr | 1.9 (1.0‐3.4) | 0.038 | 0.6 (0.1‐1.2) | 1 |

| Epilepsy | 4.4 (1.9‐9.8) | 0.001 | 1.5 (0.7‐2.3) | 2 |

| Congenital/genetic defects | 2.1 (0.9‐4.9) | 0.075 | 0.8 (0.1‐1.6) | 1 |

| History of any transplant | 3.0 (1.3‐6.9) | 0.010 | 1.1 (0.3‐1.9) | 2 |

| Enteral tube | 2.1 (1.3‐3.6) | 0.003 | 0.8 (0.3‐1.3) | 1 |

| Hemoglobin 10 g/dL in preceding 72 hr | 3.0 (1.8‐5.1) | 0.001 | 1.1 (0.6‐1.6) | 2 |

| Blood culture drawn in preceding 72 hr | 5.8 (3.3‐10.3) | 0.001 | 1.8 (1.2‐2.3) | 3 |

Predictive Score

The range of the resulting predictive score was 0 to 12. The median score among cases was 4, and the median score among controls was 1 (P 0.001). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.78 (95% confidence interval 0.74‐0.83).

We grouped the scores by SSLRs into 4 risk strata and calculated each group's estimated post‐test probability of deterioration based on the pre‐test probability of deterioration of 0.15% (Table 4). The very low‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 0.06%, less than one‐half the pre‐test probability. The low‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 0.18%, similar to the pre‐test probability. The intermediate‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 0.39%, 2.6 times higher than the pre‐test probability. The high‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 12.60%, 84 times higher than the pre‐test probability.

| Risk stratum | Score range | Cases in stratumn (%) | Controls in stratumn (%) | SSLR (95% CI) | Probability of deterioration (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Very low | 0‐2 | 37 (26) | 288 (68) | 0.4 (0.3‐0.5) | 0.06 |

| Low | 3‐4 | 37 (26) | 94 (22) | 1.2 (0.9‐1.6) | 0.2 |

| Intermediate | 5‐6 | 35 (25) | 40 (9) | 2.6 (1.7‐4.0) | 0.4 |

| High | 7‐12 | 32 (23) | 1 (1) | 96.0 (13.2‐696.2) | 12.6 |

DISCUSSION

Despite the widespread adoption of rapid response systems, we know little about the optimal methods to identify patients whose clinical characteristics alone put them at increased risk of deterioration, and triage the care they receive based on this risk. Pediatric case series have suggested that younger children and those with chronic illnesses are more likely to require assistance from a medical emergency team,1112 but this is the first study to measure their association with this outcome in children.

Most studies with the objective of identifying patients at risk have focused on tools designed to detect symptoms of deterioration that have already begun, using single‐parameter medical emergency team calling criteria1316 or multi‐parameter early warning scores.38 Rather than create a tool to detect deterioration that has already begun, we developed a predictive score that incorporates patient characteristics independently associated with deterioration in hospitalized children, including age 1 year, epilepsy, congenital/genetic defects, history of transplant, enteral tube, hemoglobin 10 g/dL, and blood culture drawn in the preceding 72 hours. The score has the potential to help clinicians identify the children at highest risk of deterioration who might benefit most from the use of vital sign‐based methods to detect deterioration, as well as the children at lowest risk for whom monitoring may be unnecessary. For example, this score could be performed at the time of admission, and those at very low risk of deterioration and without other clinically concerning findings might be considered for a low‐intensity schedule of vital signs and monitoring (such as vital signs every 8 hours, no continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring or pulse oximetry, and early warning score calculation daily), while patients in the intermediate and high‐risk groups might be considered for a more intensive schedule of vital signs and monitoring (such as vital signs every 4 hours, continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring and pulse oximetry, and early warning score calculation every 4 hours). It should be noted, however, that 37 cases (26%) fell into the very low‐risk category, raising the importance of external validation at the point of admission from the emergency department, before the score can be implemented for the potential clinical use described above. If the score performs well in validation studies, then its use in tailoring monitoring parameters has the potential to reduce the amount of time nurses spend responding to false monitor alarms and calculating early warning scores on patients at very low risk of deterioration.

Of note, we excluded children hospitalized for fewer than 24 hours, resulting in the exclusion of 31% of the potentially eligible events. We also excluded 40% of the potentially eligible ICU transfers because they did not meet urgent criteria. These may be limitations because: (1) the first 24 hours of hospitalization may be a high‐risk period; and (2) patients who were on trajectories toward severe deterioration and received interventions that prevented further deterioration, but did not meet urgent criteria, were excluded. It may be that the children we included as cases were at increased risk of deterioration that is either more difficult to recognize early, or more difficult to treat effectively without ICU interventions. In addition, the population of patients meeting urgent criteria may vary across hospitals, limiting generalizability of this score.

In summary, we developed a predictive score and risk stratification tool that may be useful in triaging the intensity of monitoring and surveillance for deterioration that children receive when hospitalized on non‐ICU units. External validation using the setting and frequency of score measurement that would be most valuable clinically (for example, in the emergency department at the time of admission) is needed before clinical use can be recommended.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Annie Chung, BA, Emily Huang, and Susan Lipsett, MD, for their assistance with data collection.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. About IHI. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/ihi/about. Accessed July 18,2010.

- ,,, et al.“Identifying the hospitalised patient in crisis”—a consensus conference on the afferent limb of Rapid Response Systems.Resuscitation.2010;81(4):375–382.

- ,,.The Pediatric Early Warning System score: a severity of illness score to predict urgent medical need in hospitalized children.J Crit Care.2006;21(3):271–278.

- ,,.Development and initial validation of the Bedside Paediatric Early Warning System score.Crit Care.2009;13(4):R135.

- .Detecting and managing deterioration in children.Paediatr Nurs.2005;17(1):32–35.

- ,,.Promoting care for acutely ill children—development and evaluation of a Paediatric Early Warning Tool.Intensive Crit Care Nurs.2006;22(2):73–81.

- ,,,,.Prospective evaluation of a pediatric inpatient early warning scoring system.J Spec Pediatr Nurs.2009;14(2):79–85.

- ,,,.Prospective cohort study to test the predictability of the Cardiff and Vale paediatric early warning system.Arch Dis Child.2009;94(8):602–606.

- ,,,,,.Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services.Pediatrics.2001;107(6):e99.

- ,,,,.Early prediction of neurological sequelae or death after bacterial meningitis.Acta Paediatr.2002;91(4):391–398.

- ,,,,.Retrospective review of emergency response activations during a 13‐year period at a tertiary care children's hospital.J Hosp Med.2011;6(3):131–135.

- ,,,.Clinical profile of hospitalized children provided with urgent assistance from a medical emergency team.Pediatrics.2008;121(6):e1577–e1584.

- ,,, et al.Implementation of a medical emergency team in a large pediatric teaching hospital prevents respiratory and cardiopulmonary arrests outside the intensive care unit.Pediatr Crit Care Med.2007;8(3):236–246.

- ,,, et al.Effect of a rapid response team on hospital‐wide mortality and code rates outside the ICU in a children's hospital.JAMA.2007;298(19):2267–2274.

- ,,, et al.Transition from a traditional code team to a medical emergency team and categorization of cardiopulmonary arrests in a children's center.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2008;162(2):117–122.

- ,.Reduction of hospital mortality and of preventable cardiac arrest and death on introduction of a pediatric medical emergency team.Pediatr Crit Care Med.2009;10(3):306–312.

Thousands of hospitals have implemented rapid response systems in recent years in attempts to reduce mortality outside the intensive care unit (ICU).1 These systems have 2 components, a response arm and an identification arm. The response arm is usually comprised of a multidisciplinary critical care team that responds to calls for urgent assistance outside the ICU; this team is often called a rapid response team or a medical emergency team. The identification arm comes in 2 forms, predictive and detective. Predictive tools estimate a patient's risk of deterioration over time based on factors that are not rapidly changing, such as elements of the patient's history. In contrast, detective tools include highly time‐varying signs of active deterioration, such as vital sign abnormalities.2 To date, most pediatric studies have focused on developing detective tools, including several early warning scores.38

In this study, we sought to identify the characteristics that increase the probability that a hospitalized child will deteriorate, and combine these characteristics into a predictive score. Tools like this may be helpful in identifying and triaging the subset of high‐risk children who should be intensively monitored for early signs of deterioration at the time of admission, as well as in identifying very low‐risk children who, in the absence of other clinical concerns, may be monitored less intensively.

METHODS

Detailed methods, including the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the matching procedures, and a full description of the statistical analysis are provided as an appendix (see Supporting Online Appendix: Supplement to Methods Section in the online version of this article). An abbreviated version follows.

Design

We performed a case‐control study among children, younger than 18 years old, hospitalized for >24 hours between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2008. The case group consisted of children who experienced clinical deterioration, a composite outcome defined as cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA), acute respiratory compromise (ARC), or urgent ICU transfer, while on a non‐ICU unit. ICU transfers were considered urgent if they included at least one of the following outcomes in the 12 hours after transfer: death, CPA, intubation, initiation of noninvasive ventilation, or administration of a vasoactive medication infusion used for the treatment of shock. The control group consisted of a random sample of patients matched 3:1 to cases if they met the criteria of being on a non‐ICU unit at the same time as their matched case.

Variables and Measurements

We collected data on demographics, complex chronic conditions (CCCs), other patient characteristics, and laboratory studies. CCCs were specific diagnoses divided into the following 9 categories according to an established framework: neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematologic/emmmunologic, metabolic, malignancy, and genetic/congenital defects.9 Other patient characteristics evaluated included age, weight‐for‐age, gestational age, history of transplant, time from hospital admission to event, recent ICU stays, administration of total parenteral nutrition, use of a patient‐controlled analgesia pump, and presence of medical devices including central venous lines and enteral tubes (naso‐gastric, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy).

Laboratory studies evaluated included hemoglobin value, white blood cell count, and blood culture drawn in the preceding 72 hours. We included these laboratory studies in this predictive score because we hypothesized that they represented factors that increased a child's risk of deterioration over time, as opposed to signs of acute deterioration that would be more appropriate for a detective score.

Statistical Analysis

We used conditional logistic regression for the bivariable and multivariable analyses to account for the matching. We derived the predictive score using an established method10 in which the regression coefficients for each covariate were divided by the smallest coefficient, and then rounded to the nearest integer, to establish each variable's sub‐score. We grouped the total scores into very low, low, intermediate, and high‐risk groups, calculated overall stratum‐specific likelihood ratios (SSLRs), and estimated stratum‐specific probabilities of deterioration for each group.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

We identified 12 CPAs, 41 ARCs, and 699 urgent ICU transfers during the study period. A total of 141 cases met our strict criteria for inclusion (see Figure in Supporting Online Appendix: Supplement to Methods Section in the online version of this article) among approximately 96,000 admissions during the study period, making the baseline incidence of events (pre‐test probability) approximately 0.15%. The case and control groups were similar in age, sex, and family‐reported race/ethnicity. Cases had been hospitalized longer than controls at the time of their event, were less likely to have been on a surgical service, and were less likely to survive to hospital discharge (Table 1). There was a high prevalence of CCCs among both cases and controls; 78% of cases and 52% of controls had at least 1 CCC.

| Cases (n = 141) | Controls (n = 423) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | P Value | |

| |||

| Type of event | |||

| Cardiopulmonary arrest | 4 (3) | 0 | NA |

| Acute respiratory compromise | 29 (20) | 0 | NA |

| Urgent ICU transfer | 108 (77) | 0 | NA |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 0.34 | ||

| 0‐6 mo | 17 (12) | 62 (15) | |

| 6‐12 mo | 22 (16) | 41 (10) | |

| 1‐4 yr | 34 (24) | 97 (23) | |

| 4‐10 yr | 26 (18) | 78 (18) | |

| 10‐18 yr | 42 (30) | 145 (34) | |

| Sex | 0.70 | ||

| Female | 60 (43) | 188 (44) | |

| Male | 81 (57) | 235 (56) | |

| Race | 0.40 | ||

| White | 69 (49) | 189 (45) | |

| Black/African‐American | 49 (35) | 163 (38) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | |

| Other | 23 (16) | 62 (15) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.53 | ||

| Non‐Hispanic | 127 (90) | 388 (92) | |

| Hispanic | 14 (10) | 33 (8) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Length of stay in days, median (interquartile range) | 7.8 (2.6‐18.2) | 3.9 (1.9‐11.2) | 0.001 |

| Surgical service | 4 (3) | 67 (16) | 0.001 |

| Survived to hospital discharge | 107 (76) | 421 (99.5) | 0.001 |

Unadjusted (Bivariable) Analysis

Results of bivariable analysis are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | OR* | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Complex chronic conditions categories | |||||

| Congenital/genetic | 19 (13) | 21 (5) | 3.0 | 1.6‐5.8 | 0.001 |

| Neuromuscular | 31 (22) | 48 (11) | 2.2 | 1.3‐3.7 | 0.002 |

| Respiratory | 18 (13) | 27 (6) | 2.0 | 1.1‐3.7 | 0.02 |

| Cardiovascular | 15 (10) | 24 (6) | 2.0 | 1.0‐3.9 | 0.05 |

| Metabolic | 5 (3) | 6 (1) | 2.5 | 0.8‐8.2 | 0.13 |

| Gastrointestinal | 10 (7) | 24 (6) | 1.3 | 0.6‐2.7 | 0.54 |

| Renal | 3 (2) | 8 (2) | 1.1 | 0.3‐4.2 | 0.86 |

| Hematology/emmmunodeficiency | 6 (4) | 19 (4) | 0.9 | 0.4‐2.4 | 0.91 |

| Specific conditions | |||||

| Mental retardation | 21 (15) | 25 (6) | 2.7 | 1.5‐4.9 | 0.001 |

| Malignancy | 49 (35) | 90 (21) | 1.9 | 1.3‐2.8 | 0.002 |

| Epilepsy | 22 (15) | 30 (7) | 2.4 | 1.3‐4.3 | 0.004 |

| Cardiac malformations | 14 (10) | 19 (4) | 2.2 | 1.1‐4.4 | 0.02 |

| Chronic respiratory disease arising in the perinatal period | 11 (8) | 15 (4) | 2.2 | 1.0‐4.8 | 0.05 |

| Cerebral palsy | 7 (5) | 13 (3) | 1.7 | 0.6‐4.2 | 0.30 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 (1) | 9 (2) | 0.3 | 0.1‐2.6 | 0.30 |

| Other patient characteristics | |||||

| Time from hospital admission to event 7 days | 74 (52) | 146 (35) | 2.1 | 1.4‐3.1 | 0.001 |

| History of any transplant | 27 (19) | 17 (4) | 5.7 | 2.9‐11.1 | 0.001 |

| Enteral tube | 65 (46) | 102 (24) | 2.6 | 1.8‐3.9 | 0.001 |

| Hospitalized in an intensive care unit during the same admission | 43 (31) | 77 (18) | 2.0 | 1.3‐3.1 | 0.002 |

| Administration of TPN in preceding 24 hr | 26 (18) | 36 (9) | 2.3 | 1.4‐3.9 | 0.002 |

| Administration of an opioid via a patient‐controlled analgesia pump in the preceding 24 hr | 14 (9) | 14 (3) | 3.6 | 1.6‐8.3 | 0.002 |

| Weight‐for‐age 5th percentile | 49 (35) | 94 (22) | 1.9 | 1.2‐2.9 | 0.003 |

| Central venous line | 55 (39) | 113 (27) | 1.8 | 1.2‐2.7 | 0.005 |

| Age 1 yr | 39 (28) | 103 (24) | 1.2 | 0.8‐1.9 | 0.42 |

| Gestational age 37 wk or documentation of prematurity | 21 (15) | 60 (14) | 1.1 | 0.6‐1.8 | 0.84 |

| Laboratory studies | |||||

| Hemoglobin in preceding 72 hr | |||||

| Not tested | 28 (20) | 190 (45) | 1.0 | [reference] | |

| 10 g/dL | 42 (30) | 144 (34) | 2.0 | 1.2‐3.5 | 0.01 |

| 10 g/dL | 71 (50) | 89 (21) | 5.6 | 3.3‐9.5 | 0.001 |

| White blood cell count in preceding 72 hr | |||||

| Not tested | 28 (20) | 190 (45) | 1.0 | [reference] | |

| 5000 to 15,000/l | 45 (32) | 131 (31) | 2.4 | 1.4‐4.1 | 0.001 |

| 15,000/l | 19 (13) | 25 (6) | 5.7 | 2.7‐12.0 | 0.001 |

| 5000/l | 49 (35) | 77 (18) | 4.5 | 2.6‐7.8 | 0.001 |

| Blood culture drawn in preceding 72 hr | 78 (55) | 85 (20) | 5.2 | 3.3‐8.1 | 0.001 |

Adjusted (Multivariable) Analysis

The multivariable conditional logistic regression model included 7 independent risk factors for deterioration (Table 3): age 1 year, epilepsy, congenital/genetic defects, history of transplant, enteral tubes, hemoglobin 10 g/dL, and blood culture drawn in the preceding 72 hours.

| Predictor | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value | Regression Coefficient (95% CI) | Score* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age 1 yr | 1.9 (1.0‐3.4) | 0.038 | 0.6 (0.1‐1.2) | 1 |

| Epilepsy | 4.4 (1.9‐9.8) | 0.001 | 1.5 (0.7‐2.3) | 2 |

| Congenital/genetic defects | 2.1 (0.9‐4.9) | 0.075 | 0.8 (0.1‐1.6) | 1 |

| History of any transplant | 3.0 (1.3‐6.9) | 0.010 | 1.1 (0.3‐1.9) | 2 |

| Enteral tube | 2.1 (1.3‐3.6) | 0.003 | 0.8 (0.3‐1.3) | 1 |

| Hemoglobin 10 g/dL in preceding 72 hr | 3.0 (1.8‐5.1) | 0.001 | 1.1 (0.6‐1.6) | 2 |

| Blood culture drawn in preceding 72 hr | 5.8 (3.3‐10.3) | 0.001 | 1.8 (1.2‐2.3) | 3 |

Predictive Score

The range of the resulting predictive score was 0 to 12. The median score among cases was 4, and the median score among controls was 1 (P 0.001). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.78 (95% confidence interval 0.74‐0.83).

We grouped the scores by SSLRs into 4 risk strata and calculated each group's estimated post‐test probability of deterioration based on the pre‐test probability of deterioration of 0.15% (Table 4). The very low‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 0.06%, less than one‐half the pre‐test probability. The low‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 0.18%, similar to the pre‐test probability. The intermediate‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 0.39%, 2.6 times higher than the pre‐test probability. The high‐risk group had a probability of deterioration of 12.60%, 84 times higher than the pre‐test probability.

| Risk stratum | Score range | Cases in stratumn (%) | Controls in stratumn (%) | SSLR (95% CI) | Probability of deterioration (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Very low | 0‐2 | 37 (26) | 288 (68) | 0.4 (0.3‐0.5) | 0.06 |

| Low | 3‐4 | 37 (26) | 94 (22) | 1.2 (0.9‐1.6) | 0.2 |

| Intermediate | 5‐6 | 35 (25) | 40 (9) | 2.6 (1.7‐4.0) | 0.4 |

| High | 7‐12 | 32 (23) | 1 (1) | 96.0 (13.2‐696.2) | 12.6 |

DISCUSSION

Despite the widespread adoption of rapid response systems, we know little about the optimal methods to identify patients whose clinical characteristics alone put them at increased risk of deterioration, and triage the care they receive based on this risk. Pediatric case series have suggested that younger children and those with chronic illnesses are more likely to require assistance from a medical emergency team,1112 but this is the first study to measure their association with this outcome in children.

Most studies with the objective of identifying patients at risk have focused on tools designed to detect symptoms of deterioration that have already begun, using single‐parameter medical emergency team calling criteria1316 or multi‐parameter early warning scores.38 Rather than create a tool to detect deterioration that has already begun, we developed a predictive score that incorporates patient characteristics independently associated with deterioration in hospitalized children, including age 1 year, epilepsy, congenital/genetic defects, history of transplant, enteral tube, hemoglobin 10 g/dL, and blood culture drawn in the preceding 72 hours. The score has the potential to help clinicians identify the children at highest risk of deterioration who might benefit most from the use of vital sign‐based methods to detect deterioration, as well as the children at lowest risk for whom monitoring may be unnecessary. For example, this score could be performed at the time of admission, and those at very low risk of deterioration and without other clinically concerning findings might be considered for a low‐intensity schedule of vital signs and monitoring (such as vital signs every 8 hours, no continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring or pulse oximetry, and early warning score calculation daily), while patients in the intermediate and high‐risk groups might be considered for a more intensive schedule of vital signs and monitoring (such as vital signs every 4 hours, continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring and pulse oximetry, and early warning score calculation every 4 hours). It should be noted, however, that 37 cases (26%) fell into the very low‐risk category, raising the importance of external validation at the point of admission from the emergency department, before the score can be implemented for the potential clinical use described above. If the score performs well in validation studies, then its use in tailoring monitoring parameters has the potential to reduce the amount of time nurses spend responding to false monitor alarms and calculating early warning scores on patients at very low risk of deterioration.

Of note, we excluded children hospitalized for fewer than 24 hours, resulting in the exclusion of 31% of the potentially eligible events. We also excluded 40% of the potentially eligible ICU transfers because they did not meet urgent criteria. These may be limitations because: (1) the first 24 hours of hospitalization may be a high‐risk period; and (2) patients who were on trajectories toward severe deterioration and received interventions that prevented further deterioration, but did not meet urgent criteria, were excluded. It may be that the children we included as cases were at increased risk of deterioration that is either more difficult to recognize early, or more difficult to treat effectively without ICU interventions. In addition, the population of patients meeting urgent criteria may vary across hospitals, limiting generalizability of this score.

In summary, we developed a predictive score and risk stratification tool that may be useful in triaging the intensity of monitoring and surveillance for deterioration that children receive when hospitalized on non‐ICU units. External validation using the setting and frequency of score measurement that would be most valuable clinically (for example, in the emergency department at the time of admission) is needed before clinical use can be recommended.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Annie Chung, BA, Emily Huang, and Susan Lipsett, MD, for their assistance with data collection.

Thousands of hospitals have implemented rapid response systems in recent years in attempts to reduce mortality outside the intensive care unit (ICU).1 These systems have 2 components, a response arm and an identification arm. The response arm is usually comprised of a multidisciplinary critical care team that responds to calls for urgent assistance outside the ICU; this team is often called a rapid response team or a medical emergency team. The identification arm comes in 2 forms, predictive and detective. Predictive tools estimate a patient's risk of deterioration over time based on factors that are not rapidly changing, such as elements of the patient's history. In contrast, detective tools include highly time‐varying signs of active deterioration, such as vital sign abnormalities.2 To date, most pediatric studies have focused on developing detective tools, including several early warning scores.38

In this study, we sought to identify the characteristics that increase the probability that a hospitalized child will deteriorate, and combine these characteristics into a predictive score. Tools like this may be helpful in identifying and triaging the subset of high‐risk children who should be intensively monitored for early signs of deterioration at the time of admission, as well as in identifying very low‐risk children who, in the absence of other clinical concerns, may be monitored less intensively.

METHODS

Detailed methods, including the inclusion/exclusion criteria, the matching procedures, and a full description of the statistical analysis are provided as an appendix (see Supporting Online Appendix: Supplement to Methods Section in the online version of this article). An abbreviated version follows.

Design

We performed a case‐control study among children, younger than 18 years old, hospitalized for >24 hours between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2008. The case group consisted of children who experienced clinical deterioration, a composite outcome defined as cardiopulmonary arrest (CPA), acute respiratory compromise (ARC), or urgent ICU transfer, while on a non‐ICU unit. ICU transfers were considered urgent if they included at least one of the following outcomes in the 12 hours after transfer: death, CPA, intubation, initiation of noninvasive ventilation, or administration of a vasoactive medication infusion used for the treatment of shock. The control group consisted of a random sample of patients matched 3:1 to cases if they met the criteria of being on a non‐ICU unit at the same time as their matched case.

Variables and Measurements

We collected data on demographics, complex chronic conditions (CCCs), other patient characteristics, and laboratory studies. CCCs were specific diagnoses divided into the following 9 categories according to an established framework: neuromuscular, cardiovascular, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal, hematologic/emmmunologic, metabolic, malignancy, and genetic/congenital defects.9 Other patient characteristics evaluated included age, weight‐for‐age, gestational age, history of transplant, time from hospital admission to event, recent ICU stays, administration of total parenteral nutrition, use of a patient‐controlled analgesia pump, and presence of medical devices including central venous lines and enteral tubes (naso‐gastric, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy).

Laboratory studies evaluated included hemoglobin value, white blood cell count, and blood culture drawn in the preceding 72 hours. We included these laboratory studies in this predictive score because we hypothesized that they represented factors that increased a child's risk of deterioration over time, as opposed to signs of acute deterioration that would be more appropriate for a detective score.

Statistical Analysis

We used conditional logistic regression for the bivariable and multivariable analyses to account for the matching. We derived the predictive score using an established method10 in which the regression coefficients for each covariate were divided by the smallest coefficient, and then rounded to the nearest integer, to establish each variable's sub‐score. We grouped the total scores into very low, low, intermediate, and high‐risk groups, calculated overall stratum‐specific likelihood ratios (SSLRs), and estimated stratum‐specific probabilities of deterioration for each group.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

We identified 12 CPAs, 41 ARCs, and 699 urgent ICU transfers during the study period. A total of 141 cases met our strict criteria for inclusion (see Figure in Supporting Online Appendix: Supplement to Methods Section in the online version of this article) among approximately 96,000 admissions during the study period, making the baseline incidence of events (pre‐test probability) approximately 0.15%. The case and control groups were similar in age, sex, and family‐reported race/ethnicity. Cases had been hospitalized longer than controls at the time of their event, were less likely to have been on a surgical service, and were less likely to survive to hospital discharge (Table 1). There was a high prevalence of CCCs among both cases and controls; 78% of cases and 52% of controls had at least 1 CCC.

| Cases (n = 141) | Controls (n = 423) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | P Value | |

| |||

| Type of event | |||

| Cardiopulmonary arrest | 4 (3) | 0 | NA |

| Acute respiratory compromise | 29 (20) | 0 | NA |

| Urgent ICU transfer | 108 (77) | 0 | NA |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | 0.34 | ||

| 0‐6 mo | 17 (12) | 62 (15) | |

| 6‐12 mo | 22 (16) | 41 (10) | |

| 1‐4 yr | 34 (24) | 97 (23) | |

| 4‐10 yr | 26 (18) | 78 (18) | |

| 10‐18 yr | 42 (30) | 145 (34) | |

| Sex | 0.70 | ||

| Female | 60 (43) | 188 (44) | |

| Male | 81 (57) | 235 (56) | |

| Race | 0.40 | ||

| White | 69 (49) | 189 (45) | |

| Black/African‐American | 49 (35) | 163 (38) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) | 7 (2) | |

| Other | 23 (16) | 62 (15) | |

| Not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.53 | ||

| Non‐Hispanic | 127 (90) | 388 (92) | |

| Hispanic | 14 (10) | 33 (8) | |

| Unknown/not reported | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | |

| Hospitalization | |||

| Length of stay in days, median (interquartile range) | 7.8 (2.6‐18.2) | 3.9 (1.9‐11.2) | 0.001 |

| Surgical service | 4 (3) | 67 (16) | 0.001 |

| Survived to hospital discharge | 107 (76) | 421 (99.5) | 0.001 |

Unadjusted (Bivariable) Analysis

Results of bivariable analysis are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Cases n (%) | Controls n (%) | OR* | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Complex chronic conditions categories | |||||

| Congenital/genetic | 19 (13) | 21 (5) | 3.0 | 1.6‐5.8 | 0.001 |

| Neuromuscular | 31 (22) | 48 (11) | 2.2 | 1.3‐3.7 | 0.002 |

| Respiratory | 18 (13) | 27 (6) | 2.0 | 1.1‐3.7 | 0.02 |

| Cardiovascular | 15 (10) | 24 (6) | 2.0 | 1.0‐3.9 | 0.05 |

| Metabolic | 5 (3) | 6 (1) | 2.5 | 0.8‐8.2 | 0.13 |

| Gastrointestinal | 10 (7) | 24 (6) | 1.3 | 0.6‐2.7 | 0.54 |

| Renal | 3 (2) | 8 (2) | 1.1 | 0.3‐4.2 | 0.86 |

| Hematology/emmmunodeficiency | 6 (4) | 19 (4) | 0.9 | 0.4‐2.4 | 0.91 |

| Specific conditions | |||||

| Mental retardation | 21 (15) | 25 (6) | 2.7 | 1.5‐4.9 | 0.001 |

| Malignancy | 49 (35) | 90 (21) | 1.9 | 1.3‐2.8 | 0.002 |

| Epilepsy | 22 (15) | 30 (7) | 2.4 | 1.3‐4.3 | 0.004 |

| Cardiac malformations | 14 (10) | 19 (4) | 2.2 | 1.1‐4.4 | 0.02 |

| Chronic respiratory disease arising in the perinatal period | 11 (8) | 15 (4) | 2.2 | 1.0‐4.8 | 0.05 |

| Cerebral palsy | 7 (5) | 13 (3) | 1.7 | 0.6‐4.2 | 0.30 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 (1) | 9 (2) | 0.3 | 0.1‐2.6 | 0.30 |

| Other patient characteristics | |||||

| Time from hospital admission to event 7 days | 74 (52) | 146 (35) | 2.1 | 1.4‐3.1 | 0.001 |

| History of any transplant | 27 (19) | 17 (4) | 5.7 | 2.9‐11.1 | 0.001 |

| Enteral tube | 65 (46) | 102 (24) | 2.6 | 1.8‐3.9 | 0.001 |

| Hospitalized in an intensive care unit during the same admission | 43 (31) | 77 (18) | 2.0 | 1.3‐3.1 | 0.002 |