User login

In reply: The negative U wave in the setting of demand ischemia

In Reply: We appreciate the comments from Drs. Suksaranjit, Cheungpasitporn, Bischof, and Marx on our recent article on the negative U wave in a patient with chronic aortic regurgitation.1 The clinical data including electrocardiography, echocardiography, and coronary angiography were presented to emphasize the importance of identifying the negative U wave in the setting of valvular heart disease. We outlined the common differential diagnosis for a negative U wave (page 506). We believe that in the appropriate clinical setting the presence of a negative U wave provides diagnostic utility.

Several published reports to date have described the occurrence of the negative U wave in the setting of obstructive coronary artery disease2–5 or coronary artery vasospasm.6 We were unable to find similar data in the setting of demand ischemia in the presence of normal coronary arteries (functional ischemia), but we fully recognize its likely occurrence, and we value the helpful insight.

- Venkatachalam S, Rimmerman CM. Electrocardiography in aortic regurgitation: it’s in the details. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:505–506.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Galli M, Temporelli P. Images in clinical medicine. Negative U waves as an indicator of stress-induced myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1791.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Kodama-Takahashi K, Ohshima K, Yamamoto K, et al. Occurrence of transient U-wave inversion during vasospastic anginal attack is not related to the direction of concurrent ST-segment shift. Chest 2002; 122:535–541.

In Reply: We appreciate the comments from Drs. Suksaranjit, Cheungpasitporn, Bischof, and Marx on our recent article on the negative U wave in a patient with chronic aortic regurgitation.1 The clinical data including electrocardiography, echocardiography, and coronary angiography were presented to emphasize the importance of identifying the negative U wave in the setting of valvular heart disease. We outlined the common differential diagnosis for a negative U wave (page 506). We believe that in the appropriate clinical setting the presence of a negative U wave provides diagnostic utility.

Several published reports to date have described the occurrence of the negative U wave in the setting of obstructive coronary artery disease2–5 or coronary artery vasospasm.6 We were unable to find similar data in the setting of demand ischemia in the presence of normal coronary arteries (functional ischemia), but we fully recognize its likely occurrence, and we value the helpful insight.

In Reply: We appreciate the comments from Drs. Suksaranjit, Cheungpasitporn, Bischof, and Marx on our recent article on the negative U wave in a patient with chronic aortic regurgitation.1 The clinical data including electrocardiography, echocardiography, and coronary angiography were presented to emphasize the importance of identifying the negative U wave in the setting of valvular heart disease. We outlined the common differential diagnosis for a negative U wave (page 506). We believe that in the appropriate clinical setting the presence of a negative U wave provides diagnostic utility.

Several published reports to date have described the occurrence of the negative U wave in the setting of obstructive coronary artery disease2–5 or coronary artery vasospasm.6 We were unable to find similar data in the setting of demand ischemia in the presence of normal coronary arteries (functional ischemia), but we fully recognize its likely occurrence, and we value the helpful insight.

- Venkatachalam S, Rimmerman CM. Electrocardiography in aortic regurgitation: it’s in the details. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:505–506.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Galli M, Temporelli P. Images in clinical medicine. Negative U waves as an indicator of stress-induced myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1791.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Kodama-Takahashi K, Ohshima K, Yamamoto K, et al. Occurrence of transient U-wave inversion during vasospastic anginal attack is not related to the direction of concurrent ST-segment shift. Chest 2002; 122:535–541.

- Venkatachalam S, Rimmerman CM. Electrocardiography in aortic regurgitation: it’s in the details. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:505–506.

- Gerson MC, Phillips JF, Morris SN, McHenry PL. Exercise-induced U-wave inversion as a marker of stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Circulation 1979; 60:1014–1020.

- Galli M, Temporelli P. Images in clinical medicine. Negative U waves as an indicator of stress-induced myocardial ischemia. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1791.

- Miwa K, Nakagawa K, Hirai T, Inoue H. Exercise-induced U-wave alterations as a marker of well-developed and well-functioning collateral vessels in patients with effort angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35:757–763.

- Rimmerman CM. A 62-year-old man with an abnormal electrocardiogram. Cleve Clin J Med 2001; 68:975–976.

- Kodama-Takahashi K, Ohshima K, Yamamoto K, et al. Occurrence of transient U-wave inversion during vasospastic anginal attack is not related to the direction of concurrent ST-segment shift. Chest 2002; 122:535–541.

Quality, frailty, and common sense

Congestive heart failure, as noted in the review by Samala et al in this issue of the Journal, is more prevalent in the elderly. Particularly in the frail elderly, managing severe congestive heart failure poses ethical, socioeconomic, and medical challenges. The presence of even subtle cognitive impairment requires detailed dialogue with family and caregivers about medications and about symptoms that warrant a trip to the emergency room. Patients on a fixed income may not be able to afford their medications and thus may use them sporadically. And the preprepared foods they often eat are laden with sodium.

The symptoms of congestive heart failure may easily go unrecognized or be attributed to other common problems. Sorting out the reasons for exertional fatigue, especially a generalized sense of fatigue, can be particularly vexing. Anemia and sarcopenia can directly cause exertional fatigue or “weakness” but may also exacerbate heart failure and cause similar symptoms. Pharmacologic and dietary causes for volume overload must be sought. Even intermittent use of over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be problematic.

Severe congestive heart failure is a lethal disease. Current quality guidelines for its treatment emphasize the use of multiple drugs and devices. Yet vasoactive drugs may not be well tolerated in frail patients, who are particularly vulnerable to orthostatic hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion. Digoxin, of marginal benefit in younger patients without tachyarrhythmias, has an even more tenuous risk-benefit ratio in the frail elderly. Beta-blockers may cause fatigue and depression, and even low-dose diuretics can exacerbate symptoms of bladder dysfunction. Previously implanted defibrillators may be inconsistent with the patient’s current end-of-life desires.

Ideal management of the genuinely frail elderly patient with severe congestive heart failure is not always a matter of ventricular assist devices, biventricular pacers, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. At some point, referral to palliative care resources, guided by informed input from the patient, family members, and caregivers, may be the most appropriate high-quality care that we can (and should) offer.

Congestive heart failure, as noted in the review by Samala et al in this issue of the Journal, is more prevalent in the elderly. Particularly in the frail elderly, managing severe congestive heart failure poses ethical, socioeconomic, and medical challenges. The presence of even subtle cognitive impairment requires detailed dialogue with family and caregivers about medications and about symptoms that warrant a trip to the emergency room. Patients on a fixed income may not be able to afford their medications and thus may use them sporadically. And the preprepared foods they often eat are laden with sodium.

The symptoms of congestive heart failure may easily go unrecognized or be attributed to other common problems. Sorting out the reasons for exertional fatigue, especially a generalized sense of fatigue, can be particularly vexing. Anemia and sarcopenia can directly cause exertional fatigue or “weakness” but may also exacerbate heart failure and cause similar symptoms. Pharmacologic and dietary causes for volume overload must be sought. Even intermittent use of over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be problematic.

Severe congestive heart failure is a lethal disease. Current quality guidelines for its treatment emphasize the use of multiple drugs and devices. Yet vasoactive drugs may not be well tolerated in frail patients, who are particularly vulnerable to orthostatic hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion. Digoxin, of marginal benefit in younger patients without tachyarrhythmias, has an even more tenuous risk-benefit ratio in the frail elderly. Beta-blockers may cause fatigue and depression, and even low-dose diuretics can exacerbate symptoms of bladder dysfunction. Previously implanted defibrillators may be inconsistent with the patient’s current end-of-life desires.

Ideal management of the genuinely frail elderly patient with severe congestive heart failure is not always a matter of ventricular assist devices, biventricular pacers, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. At some point, referral to palliative care resources, guided by informed input from the patient, family members, and caregivers, may be the most appropriate high-quality care that we can (and should) offer.

Congestive heart failure, as noted in the review by Samala et al in this issue of the Journal, is more prevalent in the elderly. Particularly in the frail elderly, managing severe congestive heart failure poses ethical, socioeconomic, and medical challenges. The presence of even subtle cognitive impairment requires detailed dialogue with family and caregivers about medications and about symptoms that warrant a trip to the emergency room. Patients on a fixed income may not be able to afford their medications and thus may use them sporadically. And the preprepared foods they often eat are laden with sodium.

The symptoms of congestive heart failure may easily go unrecognized or be attributed to other common problems. Sorting out the reasons for exertional fatigue, especially a generalized sense of fatigue, can be particularly vexing. Anemia and sarcopenia can directly cause exertional fatigue or “weakness” but may also exacerbate heart failure and cause similar symptoms. Pharmacologic and dietary causes for volume overload must be sought. Even intermittent use of over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can be problematic.

Severe congestive heart failure is a lethal disease. Current quality guidelines for its treatment emphasize the use of multiple drugs and devices. Yet vasoactive drugs may not be well tolerated in frail patients, who are particularly vulnerable to orthostatic hypotension and cerebral hypoperfusion. Digoxin, of marginal benefit in younger patients without tachyarrhythmias, has an even more tenuous risk-benefit ratio in the frail elderly. Beta-blockers may cause fatigue and depression, and even low-dose diuretics can exacerbate symptoms of bladder dysfunction. Previously implanted defibrillators may be inconsistent with the patient’s current end-of-life desires.

Ideal management of the genuinely frail elderly patient with severe congestive heart failure is not always a matter of ventricular assist devices, biventricular pacers, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. At some point, referral to palliative care resources, guided by informed input from the patient, family members, and caregivers, may be the most appropriate high-quality care that we can (and should) offer.

Heart failure in frail, older patients: We can do ‘MORE’

Mr. R. is an 85-year-old with congestive heart failure; the last time his ejection fraction was measured it was 30%. He also has hypertension, coronary artery disease (for which he underwent triple-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting), osteoarthritis, hyperlipidemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He currently takes lisinopril (Zestril), carvedilol (Coreg), aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix), digoxin, simvastatin (Zocor), furosemide (Lasix), an albuterol inhaler (Proventil), and over-the-counter naproxen (Naprosyn), the last two taken as needed.

Accompanied by his daughter, Mr. R. comes to see his primary care physician for a routine follow-up visit. He says he feels fine and has no shortness of breath or chest pain, but he feels light-headed at times, especially when he gets out of bed. He also mentions that he is bothered with having to get up three to four times at night to urinate.

On further questioning, he relates that he uses a cane to walk around the house and gets short of breath when walking from his bed to the bathroom and from one room to the next. He can feed himself, but he needs assistance with bathing and getting dressed.

Mr. R. admits that he has been feeling lonely since his wife died about a year ago. He now lives with his daughter and her family, and they all get along well. His daughter mentions that over the last 6 months he has not been eating well, that he appears to have lost interest in doing some of the things that he used to enjoy, and that he has lost weight. She adds that he has fallen twice in the last month.

On physical examination, Mr. R. is without distress but appears weak. He answers all questions appropriately, although his affect is flat and his daughter fills in some of the details.

Supine, his blood pressure is 160/90 mm Hg and his heart rate is 75; immediately after standing up he feels dizzy and his blood pressure drops to 120/60 mm Hg with a heart rate of 110. Three months ago he weighed 155 pounds (70.3 kg); today he weighs 145 pounds (65.9 kg).

His neck veins are not distended. On chest auscultation, bibasilar coarse crackles are heard, as well as a systolic murmur (grade 2 on a scale of 6), loudest in the second intercostal space at the right parasternal border. No peripheral edema is detected. His Mini-Mental State Exam score is 22 out of 30.

What changes, if any, should be made in Mr. R.’s management? What advice should the primary care physician give Mr. R. and his daughter about the course of his heart failure?

THE IMPORTANCE OF COMPLETE CARE

Mr. R. has multiple convoluted medical issues that plague many elderly patients with heart failure. To provide optimal care to patients like him, physicians need to draw on knowledge from the fields of internal medicine, geriatrics, and cardiology.

In this paper, we discuss how diagnosing and managing heart failure is different in elderly patients. We emphasize the importance of complete care of frail elderly patients, highlighting the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions that are available. Finally, we will return to Mr. R. and discuss a comprehensive plan for him.

HEART FAILURE, FRAILTY, DISABILITY ARE ALL CONNECTED

The ability to bounce back from physical insults, chiefly medical illnesses, sharply declines in old age. As various stressors accumulate, physical deterioration becomes inevitable. While some older adults can avoid going down this path of morbidity, in an increasing number of frail elderly patients, congestive heart failure inescapably assumes a complicated course.

Frailty is a state of increased vulnerability to stressors due to age-related declines in physiologic reserve.1 Two elements intimately related to frailty are comorbidity and disability.

Fried et al2 analyzed data from more than 5,000 older men and women in the Cardiovascular Health Study and concluded that comorbidity (ie, having two or more chronic diseases) is a risk factor for frailty, which in turn results in disability, falls, hospitalizations, and death.

The relationship between congestive heart failure and frailty is complex. Not only does heart failure itself result in frailty, but its multiple therapies can put additional stress on a frail patient. In addition, the heart failure and its treatments can negatively affect coexisting disorders (Figure 1).

BY THE NUMBERS

Heart failure is largely a disorder of the elderly, and as the US population ages, heart failure is rising in prevalence to epidemic numbers.3 The median age of patients admitted to the hospital because of heart failure is 75,4 and patients age 65 and older account for more than 75% of heart failure hospitalizations.5 Every year, in every 1,000 people over age 65, nearly 10 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed.6

Before age 70, men are affected more than women, but the opposite is true at age 70 and beyond. The reason for this reversal is that women live longer and have a better prognosis, as the cause of heart failure in most women is diastolic dysfunction secondary to hypertension rather than systolic dysfunction due to coronary artery disease, as in most men.7

Heart failure is costly and generally has a poor prognosis. The total cost of treating it reached a staggering $37.2 billion in 2009, and it was the leading cause of Medicare hospital admissions.6 Heart failure is the primary cause or a contributory cause of death in about 290,000 patients each year, and the rate of death at 1 year is an astonishing 1 in 5.6 The median survival time after diagnosis is 2.3 to 3.6 years in patients ages 67 to 74, and it is considerably shorter—1.1 to 1.6 years—in patients age 85 and older.8

THE BROKEN HEART

In 2005, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association defined congestive heart failure as “a complex clinical syndrome that can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood.”9 This characterization captures the intricate nature of the disease: its spectrum of symptoms, its many causes (eg, coronary artery disease, hypertension, nonischemic or idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and valvular heart disease), and the dual pathophysiologic features of systolic and diastolic impairment.

Systolic vs diastolic failure

Of the various ways of classifying heart failure, the most important is systolic vs diastolic.

The hallmark of systolic heart failure is a decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, and it is characterized by a large thin-walled ventricle that is weak and unable to eject enough blood to generate a normal cardiac output.

In contrast, the ejection fraction is normal or nearly normal in diastolic heart failure, but the end-diastolic volume is decreased because the ventricle is hypertrophied and thick-walled. The resultant chamber has become small and stiff and does not have enough volume for sufficient cardiac output.

QUIRKS IN THE HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The combination of inactivity and coexisting illnesses in a frail older adult may obscure some of the usual clinical manifestations of heart failure. While shortness of breath on mild exertion, easy fatigability, and leg swelling are common in younger heart failure patients, these symptoms may be due to normal aging in a much older patient. Let us consider some important aspects of the common signs and symptoms associated with heart failure.

Dyspnea on exertion is one of the earliest and most prominent symptoms. The usual question asked of patients to elicit whether this key manifestation is present is, “Do you get short of breath after walking a block?” However, this question may not be appropriate for a frail elderly person whose activity is restricted by comorbidities such as severe arthritis, coronary artery disease, or peripheral arterial disease. For a patient like this, ask instead if he or she gets short of breath after milder forms of exertion, such as making the bed, walking to the bathroom, or changing clothes.10 Also, keep in mind that dyspnea on exertion may be due to other conditions, such as renal failure, lung disease, depression, anemia, or deconditioning.

Orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea may not be volunteered or elicited if a patient is sleeping in a chair or a recliner.

Leg swelling is less specific in older adults than in younger patients because chronic venous insufficiency is common in older people.

Weight gain almost always accompanies symptomatic heart failure but may also be due to increased appetite secondary to depression.

A change in mental status is common in elderly people with heart failure, especially those with vascular dementia with extensive cerebrovascular atherosclerosis or those who have latent Alzheimer disease.10

Cough, a symptom of a multitude of disorders, may be an early or the only manifestation of heart failure.

Pulmonary crackles are typically detected in most heart failure patients, but they may not be as characteristic in older adults, as they may also be noted in bronchitis, pneumonia, and other chronic lung diseases.

Additional symptoms to watch for include fatigue, syncope, angina, nocturia, and oliguria.

The bottom line is to integrate individual findings with other elements of the history and physical examination in diagnosing heart failure and tracking its progression.

CLINCHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Congestive heart failure is essentially a clinical diagnosis best established even before ordering tests, especially during times and situations in which these tests are not always readily available, such as outside office hours and in a long-term care setting.

A reliable and thorough history and physical examination is the most important component of the diagnostic process.

An echocardiogram is obtained next to measure the ejection fraction, which has both prognostic and therapeutic significance. Echocardiography can also uncover potential contributory cardiac structural abnormalities.

A chest radiograph is also typically obtained to look for pulmonary congestion, but in older adults its interpretation may be skewed by chronic lung disease or spinal deformities such as scoliosis and kyphosis.

The B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level is a popular blood test. BNP is commonly elevated in patients with heart failure. However, an elevated level in older adults should always be evaluated within the context of other clinical findings, as it can also result from advancing age and diseases other than heart failure, such as coronary artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, pulmonary embolism, and renal insufficiency.11,12

PHARMACOTHERAPY PEARLS

Drug treatment for heart failure has evolved rapidly. Robust and sophisticated clinical trials have led to guidelines that call for specific medications. Unfortunately, older patients, particularly the very old and frail, have been poorly represented in these studies.9 Nonetheless, the type and choice of drugs for the young and old are similar.

Take into account age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics

Age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics must be taken into account when prescribing drugs for heart failure.13

Oral absorption of cardiovascular drugs is not significantly affected by the various changes that occur in older adults (eg, reduced gastric acid production, gastric emptying rate, gastrointestinal blood flow, and mobility). However, reductions in both lean body mass and total body water that come with aging result in lower volumes of distribution and higher plasma concentrations of hydrophilic drugs, most notably angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and digoxin. In contrast, the plasma concentrations of lipophilic drugs such as beta-blockers and central alpha-agonists tend to decrease as the proportion of body fat increases in older adults.

As the plasma albumin level diminishes with age, the free-drug concentration of salicylates and warfarin (Coumadin), which are extensively albumin-bound, may increase.

The serum concentrations of cardiovascular drugs metabolized in the liver—eg, propranolol (Inderal), lidocaine, labetalol (Trandate), verapamil (Calan), diltiazem (Cardizem), nitrates, and warfarin—may be elevated due to reduced hepatic blood flow, mass, volume, and overall metabolic capacity.

Declines in renal blood flow, glomerular filtration, and tubular function may cause accumulation of drugs that are excreted through the kidneys.

Beware of toxicities

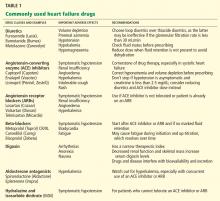

Table 1 lists some of the drugs used in treating heart failure, common adverse affects to watch for, and recommendations for their use.

WIELDING THE SCALPEL

A tenet of heart failure management is to correct the underlying cardiac structural abnormality. This often calls for invasive intervention along with optimization of drug therapy.

For example:

- Diseased coronary arteries may be amenable to revascularization, either by percutaneous coronary intervention or by the much more involved coronary artery bypass grafting, with the aim of enhancing cardiac function.

- Valves can be repaired or replaced in patients with valvular heart disease.

- A pacemaker can be implanted to remedy sick sinus syndrome, especially with concurrent use of heart-rate-lowering agents such as beta-blockers.

- Placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator has been found to be effective in preventing death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with an ejection fraction of less than 30%.9

- Cardiac resynchronization with a biventricular pacemaker may increase the ejection fraction and cardiac output by eliminating dyssynchronous contraction of the left and right ventricles.14

In frail older adults, consideration of these invasive therapies must be individualized. While procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention and pacemaker placement may not be as physically taxing as bypass grafting or valve replacement, the potential for surgical complications must be seriously considered, particularly if the patient has diminished physiologic reserve. Case-to-case consideration is also crucial in cardioverter-defibrillator insertion, as the survival benefit may be diminished in older adults, who likely have coexisting illnesses that predispose them to die of a noncardiac cause.15,16

The bottom line is to contemplate multiple factors—severity of the heart failure, comorbidities, baseline functional status, and social support—when assessing the appropriateness of an invasive intervention.

BEYOND DRUGS AND DEVICES: WE CAN DO ‘MORE’

Much of the spotlight has been on the various drugs and devices used to treat heart failure, but of equal importance for frail elderly patients are complementary approaches that can be used to ease disease progression and boost the quality of life. The acronym MORE highlights these strategies.

M: Multidisciplinary management programs

Heart failure disease-management programs are designed to provide comprehensive multidisciplinary care across different settings (ie, home, outpatient, and inpatient) to high-risk patients who often have multiple medical, social, and behavioral issues.9 Interventions usually include intensive patient education, encouraging patients to be more aggressive participants in their care, closely monitoring patients through telephone follow-up or home nursing, carefully reviewing medications to improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines, and multidisciplinary care with nurse case management directed by a physician.

Studies have shown that management programs, which were largely nurse-directed and targeted at older adults and patients with advanced disease, can improve quality of life and functional status, decrease hospitalizations for both heart failure and other causes, and decrease medical costs.17–19

O: Other diseases

R: Restrictions

Specific limitations in the intake of certain dietary elements are a valuable adjunct in heart failure management.

Sodium intake should be restricted to less than 3 g/day by not adding salt to meals and by avoiding salt-rich foods (eg, canned and processed foods).24 During times of distressing volume overload, a tighter sodium limit of 2 g/day is necessary, and diuretics may be less effective if this restriction is not implemented.

Fluid restriction depends on the patient’s clinical status.25 While it is not necessary to limit fluid intake in the absence of retention, a limit of 2 L/day is recommended if edema is detected. If volume overload is severe, the limit should be 1 L/day.

Alcohol is a myocardial depressant that reduces the left ventricular ejection fraction.26 Abstinence is a must for patients with alcohol-induced heart failure; otherwise, a limit of 1 drink (8 oz of beer, 4 oz of wine, or 1 oz of hard liquor) per day is suggested.24

Calories and fat intake are both important to watch, particularly in patients with obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, or coronary artery disease.

E: End-of-life issues

Usual causes of death in patients with heart failure include sudden cardiac death, arrhythmias, hypotension, end-organ hypoperfusion, and metabolic derangement.27,28

Given the life-limiting nature of the disease in frail older adults, it is very important for clinicians to discuss end-of-life matters with patients and their families as early as possible. Needed are effective communication skills that foster respect, empathy, and mutual understanding.

Advance directives. The primary task is to encourage patients to develop advance health directives. These are legal documents that represent patients’ preferences about interventions available toward the end of life such as do-not-resuscitate orders, appointment of surrogate decision-makers, and use of life-sustaining interventions (eg, a feeding tube, dialysis, blood transfusions). Establishing these directives early on will help ease the transition from one mode of care to another (eg, from acute care to hospice care), prevent pointless use of resources (eg, emergency room visits, hospital admissions), and ensure that the patient’s wishes are carried out.

Palliative measures that aim to alleviate suffering and promote quality of life and dignity are available for patients with severe symptoms. For varying degrees of dyspnea, diuretics, nitrates, morphine, and positive inotropic agents such as dobutamine (Dobutrex) and milrinone (Primacor) can be tried. Thoracentesis is done in patients with extensive pleural effusion. Fatigue and anorexia are due to a combination of factors, namely, decreased cardiac output, increased neurohormone levels, deconditioning, depression, decreased sleep, and anxiety.29 Opioids, caffeine, exercise, oxygen, fluid and salt restriction, and correction of anemia and depression may help ease these symptoms.

For patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, deactivation is an important matter that needs to be addressed. Deactivation can be carried out with certainty once the goal of care has shifted away from curative efforts and either the patient or a surrogate decision-maker has made the informed decision to turn the device off. Berger30 raised three points that the clinician and decision-maker can discuss in trying to achieve a resolution during times of doubt and indecision:

- The patient may no longer value continued survival

- The device may no longer offer the prospect of increased survival

- The device may impede active dying.

The idea of hospice care should be gradually and gently explored to ensure a prompt and seamless transition when the time comes. The patient and family need to know that the goal of hospice care is to ensure comfort and that they can benefit the most by enrolling early during the course of the terminal illness.

The Medicare hospice benefit is granted to patients who have been certified by two physicians to have a life expectancy of 6 months or less if their terminal illness runs its natural course. The criteria for determining that heart failure is terminal are:

- New York Heart Association class III (symptomatic with less than ordinary activities) or IV (symptomatic at rest)

- Left ventricular ejection fraction less than or equal to 20%

- Persistent symptoms despite optimal medical management

- Inability to tolerate optional management due to hypotension with or without renal failure.31

WHAT CAN WE DO FOR MR. R.?

Mr. R. has systolic heart failure stemming from coronary artery disease, and his symptoms put him in New York Heart Association class III. He is well managed with drugs of different appropriate classes: an ACE inhibitor, a beta-blocker, digoxin, an aldosterone antagonist, and a diuretic. His other drugs all have well-defined indications.

Since he does not have fluid overload, his furosemide can be stopped, and this change will likely relieve his orthostatic hypotension and nocturia. His systolic blood pressure target can be liberalized to 150 mm Hg or less, as tighter control might exacerbate orthostatic hypotension. This change, along with having him start using a walker instead of a cane, will hopefully prevent future falls. Furthermore, his naproxen should be discontinued, as it can worsen heart failure.

Mr. R. has symptoms of depression and thus needs to be started on an antidepressant and encouraged to engage in social activities as much as he can tolerate. These interventions may also help with his mild dementia, which is evidenced by a Mini-Mental State Exam score of 22. He will not benefit from sodium and fat restriction, as he has actually been losing weight.

To keep Mr. R.’s cognitive impairment and overall decline in function from compromising his compliance with his treatment, he will need a substantial amount of assistance, which his daughter alone may not be able to provide. To tackle this concern, a discussion about participating in a heart failure management program can be started with Mr. R. and his family.

More importantly, his advanced directives, including delegating a surrogate decision-maker and deciding on do-not-resuscitate status, have to be clarified. Finally, it would be prudent to introduce the concept of hospice care to the patient and his daughter while he is still coherent and able to state his preferences.

- Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferruci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: summary from the American Geriatrics Society/National Institute on Aging Research Conference on Frailty in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006; 54:991–1001.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001; 56:M146–M156.

- Schocken DD, Arrieta MI, Leaverton PE, Ross EA. Prevalence and mortality rate of congestive heart failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992; 20:301–306.

- Popovic JR, 1999 National Hospital Discharge Survey: annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2001; 13:1–206.

- DeFrances CJ, Hall MJ, Podgornik MN. 2003 National Hospital Discharge Survey. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no. 359. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics, 2005.

- American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2009 update: a report From the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 2009; 119:e21–e181.

- Levy D, Larson MG, Vasan RS, et al. The progression from hypertension to congestive heart failure. JAMA 1996; 275:1557–1562.

- Croft JB, Giles WH, Pollard RA, et al. Heart failure survival among older adults in the United States: a poor prognosis for an emerging epidemic in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:505–510.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure). Circulation 2005; 112:e154–e235.

- Ahmed A. Clinical manifestations, diagnostic assessment, and etiology of heart failure in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 2007; 23:11–30.

- Redfield MM, Rodeheffer RJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide concentration: impact of age and gender. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 40:976–982.

- Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Impact of age and sex on plasma natriuretic peptide levels in healthy adults. Am J Cardiol 2002; 90:254–258.

- Aronow WS, Frishman WH, Cheng-Lai A. Cardiovascular drug therapy in the elderly. Cardiol Rev 2007; 15:195–215.

- Bakker P, Meijburg H, de Bries J, et al. Biventricular pacing in end-stage heart failure improves functional capacity and left ventricular function. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2000; 4:395–404.

- Healey JS, Hallstrom AP, Kuck KH, et al. Role of the implantable defibrillator among elderly patients with a history of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. Eur Heart J 2007; 28:1746–1749.

- Lee DS, Tu JV, Austin PC, et al. Effect of cardiac and noncardiac conditions on survival after defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:2408–2415.

- Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, et al. A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1190–1195.

- Fonarow GC, Stevenson LW, Walden JA, et al. Impact of a comprehensive heart failure management program on hospital readmission and functional status of patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30:725–732.

- McAlister F, Stewart S, Ferrua S, McMurray JJ. Multidisciplinary strategies for the management of heart failure patients at high risk for admission: a systematic review of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:810–819.

- Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, et al. Anemia is associated with worse symptoms, greater impairment in functional capacity and a significant increase in mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:1780–1786.

- Al-Ahmad A, Rand WM, Manjunath G, et al. Reduced kidney function and anemia as risk factors for mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 38:955–962.

- Singh SN, Fisher SG, Deedwania PC, et al. Pulmonary effect of amiodarone in patients with heart failure: the Congestive Heart Failure-Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy (CHF-STAT) Investigators (Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study No. 320). J Am Coll Cardiol 1997; 30:514–517.

- Cohen MB, Mather PJ. A review of the association between congestive heart failure and cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 2007; 16:171–174.

- Dracup K, Baker DW, Dunbar SB, et al. Management of heart failure. II. Counseling, education, and lifestyle modifications. JAMA 1994; 272:1442–1446.

- Lenihan DJ, Uretsky BF. Non-pharmacologic treatment of heart failure in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 2000; 16:477–488.

- Regan TJ. Alcohol and the cardiovascular system. JAMA 1990; 264:377–381.

- Teuteberg JJ, Lewis EF, Nohria A, et al. Characteristics of patients who die with heart failure and a low ejection fraction in the new millennium. J Card Fail 2006; 12:47–53.

- Derfler MC, Jacob M, Wolf RE, et al. Mode of death from congestive heart failure: implications for clinical management. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 2004; 13:299–304.

- Evangelista LS, Moser DK, Westlake C, et al. Correlates of fatigue in patients with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs 2008; 23:12–17.

- Berger JT. The ethics of deactivating implanted cardioverter defibrillators. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142:631–634.

- Stuart B, Connor S, Kinzbrunner BM, et al. Medical guidelines for determining prognosis in selected non-cancer diseases, 2nd ed. Arlington VA, National Hospice Organization; 1996.

Mr. R. is an 85-year-old with congestive heart failure; the last time his ejection fraction was measured it was 30%. He also has hypertension, coronary artery disease (for which he underwent triple-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting), osteoarthritis, hyperlipidemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He currently takes lisinopril (Zestril), carvedilol (Coreg), aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix), digoxin, simvastatin (Zocor), furosemide (Lasix), an albuterol inhaler (Proventil), and over-the-counter naproxen (Naprosyn), the last two taken as needed.

Accompanied by his daughter, Mr. R. comes to see his primary care physician for a routine follow-up visit. He says he feels fine and has no shortness of breath or chest pain, but he feels light-headed at times, especially when he gets out of bed. He also mentions that he is bothered with having to get up three to four times at night to urinate.

On further questioning, he relates that he uses a cane to walk around the house and gets short of breath when walking from his bed to the bathroom and from one room to the next. He can feed himself, but he needs assistance with bathing and getting dressed.

Mr. R. admits that he has been feeling lonely since his wife died about a year ago. He now lives with his daughter and her family, and they all get along well. His daughter mentions that over the last 6 months he has not been eating well, that he appears to have lost interest in doing some of the things that he used to enjoy, and that he has lost weight. She adds that he has fallen twice in the last month.

On physical examination, Mr. R. is without distress but appears weak. He answers all questions appropriately, although his affect is flat and his daughter fills in some of the details.

Supine, his blood pressure is 160/90 mm Hg and his heart rate is 75; immediately after standing up he feels dizzy and his blood pressure drops to 120/60 mm Hg with a heart rate of 110. Three months ago he weighed 155 pounds (70.3 kg); today he weighs 145 pounds (65.9 kg).

His neck veins are not distended. On chest auscultation, bibasilar coarse crackles are heard, as well as a systolic murmur (grade 2 on a scale of 6), loudest in the second intercostal space at the right parasternal border. No peripheral edema is detected. His Mini-Mental State Exam score is 22 out of 30.

What changes, if any, should be made in Mr. R.’s management? What advice should the primary care physician give Mr. R. and his daughter about the course of his heart failure?

THE IMPORTANCE OF COMPLETE CARE

Mr. R. has multiple convoluted medical issues that plague many elderly patients with heart failure. To provide optimal care to patients like him, physicians need to draw on knowledge from the fields of internal medicine, geriatrics, and cardiology.

In this paper, we discuss how diagnosing and managing heart failure is different in elderly patients. We emphasize the importance of complete care of frail elderly patients, highlighting the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions that are available. Finally, we will return to Mr. R. and discuss a comprehensive plan for him.

HEART FAILURE, FRAILTY, DISABILITY ARE ALL CONNECTED

The ability to bounce back from physical insults, chiefly medical illnesses, sharply declines in old age. As various stressors accumulate, physical deterioration becomes inevitable. While some older adults can avoid going down this path of morbidity, in an increasing number of frail elderly patients, congestive heart failure inescapably assumes a complicated course.

Frailty is a state of increased vulnerability to stressors due to age-related declines in physiologic reserve.1 Two elements intimately related to frailty are comorbidity and disability.

Fried et al2 analyzed data from more than 5,000 older men and women in the Cardiovascular Health Study and concluded that comorbidity (ie, having two or more chronic diseases) is a risk factor for frailty, which in turn results in disability, falls, hospitalizations, and death.

The relationship between congestive heart failure and frailty is complex. Not only does heart failure itself result in frailty, but its multiple therapies can put additional stress on a frail patient. In addition, the heart failure and its treatments can negatively affect coexisting disorders (Figure 1).

BY THE NUMBERS

Heart failure is largely a disorder of the elderly, and as the US population ages, heart failure is rising in prevalence to epidemic numbers.3 The median age of patients admitted to the hospital because of heart failure is 75,4 and patients age 65 and older account for more than 75% of heart failure hospitalizations.5 Every year, in every 1,000 people over age 65, nearly 10 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed.6

Before age 70, men are affected more than women, but the opposite is true at age 70 and beyond. The reason for this reversal is that women live longer and have a better prognosis, as the cause of heart failure in most women is diastolic dysfunction secondary to hypertension rather than systolic dysfunction due to coronary artery disease, as in most men.7

Heart failure is costly and generally has a poor prognosis. The total cost of treating it reached a staggering $37.2 billion in 2009, and it was the leading cause of Medicare hospital admissions.6 Heart failure is the primary cause or a contributory cause of death in about 290,000 patients each year, and the rate of death at 1 year is an astonishing 1 in 5.6 The median survival time after diagnosis is 2.3 to 3.6 years in patients ages 67 to 74, and it is considerably shorter—1.1 to 1.6 years—in patients age 85 and older.8

THE BROKEN HEART

In 2005, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association defined congestive heart failure as “a complex clinical syndrome that can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood.”9 This characterization captures the intricate nature of the disease: its spectrum of symptoms, its many causes (eg, coronary artery disease, hypertension, nonischemic or idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and valvular heart disease), and the dual pathophysiologic features of systolic and diastolic impairment.

Systolic vs diastolic failure

Of the various ways of classifying heart failure, the most important is systolic vs diastolic.

The hallmark of systolic heart failure is a decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, and it is characterized by a large thin-walled ventricle that is weak and unable to eject enough blood to generate a normal cardiac output.

In contrast, the ejection fraction is normal or nearly normal in diastolic heart failure, but the end-diastolic volume is decreased because the ventricle is hypertrophied and thick-walled. The resultant chamber has become small and stiff and does not have enough volume for sufficient cardiac output.

QUIRKS IN THE HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The combination of inactivity and coexisting illnesses in a frail older adult may obscure some of the usual clinical manifestations of heart failure. While shortness of breath on mild exertion, easy fatigability, and leg swelling are common in younger heart failure patients, these symptoms may be due to normal aging in a much older patient. Let us consider some important aspects of the common signs and symptoms associated with heart failure.

Dyspnea on exertion is one of the earliest and most prominent symptoms. The usual question asked of patients to elicit whether this key manifestation is present is, “Do you get short of breath after walking a block?” However, this question may not be appropriate for a frail elderly person whose activity is restricted by comorbidities such as severe arthritis, coronary artery disease, or peripheral arterial disease. For a patient like this, ask instead if he or she gets short of breath after milder forms of exertion, such as making the bed, walking to the bathroom, or changing clothes.10 Also, keep in mind that dyspnea on exertion may be due to other conditions, such as renal failure, lung disease, depression, anemia, or deconditioning.

Orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea may not be volunteered or elicited if a patient is sleeping in a chair or a recliner.

Leg swelling is less specific in older adults than in younger patients because chronic venous insufficiency is common in older people.

Weight gain almost always accompanies symptomatic heart failure but may also be due to increased appetite secondary to depression.

A change in mental status is common in elderly people with heart failure, especially those with vascular dementia with extensive cerebrovascular atherosclerosis or those who have latent Alzheimer disease.10

Cough, a symptom of a multitude of disorders, may be an early or the only manifestation of heart failure.

Pulmonary crackles are typically detected in most heart failure patients, but they may not be as characteristic in older adults, as they may also be noted in bronchitis, pneumonia, and other chronic lung diseases.

Additional symptoms to watch for include fatigue, syncope, angina, nocturia, and oliguria.

The bottom line is to integrate individual findings with other elements of the history and physical examination in diagnosing heart failure and tracking its progression.

CLINCHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Congestive heart failure is essentially a clinical diagnosis best established even before ordering tests, especially during times and situations in which these tests are not always readily available, such as outside office hours and in a long-term care setting.

A reliable and thorough history and physical examination is the most important component of the diagnostic process.

An echocardiogram is obtained next to measure the ejection fraction, which has both prognostic and therapeutic significance. Echocardiography can also uncover potential contributory cardiac structural abnormalities.

A chest radiograph is also typically obtained to look for pulmonary congestion, but in older adults its interpretation may be skewed by chronic lung disease or spinal deformities such as scoliosis and kyphosis.

The B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level is a popular blood test. BNP is commonly elevated in patients with heart failure. However, an elevated level in older adults should always be evaluated within the context of other clinical findings, as it can also result from advancing age and diseases other than heart failure, such as coronary artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, pulmonary embolism, and renal insufficiency.11,12

PHARMACOTHERAPY PEARLS

Drug treatment for heart failure has evolved rapidly. Robust and sophisticated clinical trials have led to guidelines that call for specific medications. Unfortunately, older patients, particularly the very old and frail, have been poorly represented in these studies.9 Nonetheless, the type and choice of drugs for the young and old are similar.

Take into account age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics

Age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics must be taken into account when prescribing drugs for heart failure.13

Oral absorption of cardiovascular drugs is not significantly affected by the various changes that occur in older adults (eg, reduced gastric acid production, gastric emptying rate, gastrointestinal blood flow, and mobility). However, reductions in both lean body mass and total body water that come with aging result in lower volumes of distribution and higher plasma concentrations of hydrophilic drugs, most notably angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and digoxin. In contrast, the plasma concentrations of lipophilic drugs such as beta-blockers and central alpha-agonists tend to decrease as the proportion of body fat increases in older adults.

As the plasma albumin level diminishes with age, the free-drug concentration of salicylates and warfarin (Coumadin), which are extensively albumin-bound, may increase.

The serum concentrations of cardiovascular drugs metabolized in the liver—eg, propranolol (Inderal), lidocaine, labetalol (Trandate), verapamil (Calan), diltiazem (Cardizem), nitrates, and warfarin—may be elevated due to reduced hepatic blood flow, mass, volume, and overall metabolic capacity.

Declines in renal blood flow, glomerular filtration, and tubular function may cause accumulation of drugs that are excreted through the kidneys.

Beware of toxicities

Table 1 lists some of the drugs used in treating heart failure, common adverse affects to watch for, and recommendations for their use.

WIELDING THE SCALPEL

A tenet of heart failure management is to correct the underlying cardiac structural abnormality. This often calls for invasive intervention along with optimization of drug therapy.

For example:

- Diseased coronary arteries may be amenable to revascularization, either by percutaneous coronary intervention or by the much more involved coronary artery bypass grafting, with the aim of enhancing cardiac function.

- Valves can be repaired or replaced in patients with valvular heart disease.

- A pacemaker can be implanted to remedy sick sinus syndrome, especially with concurrent use of heart-rate-lowering agents such as beta-blockers.

- Placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator has been found to be effective in preventing death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with an ejection fraction of less than 30%.9

- Cardiac resynchronization with a biventricular pacemaker may increase the ejection fraction and cardiac output by eliminating dyssynchronous contraction of the left and right ventricles.14

In frail older adults, consideration of these invasive therapies must be individualized. While procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention and pacemaker placement may not be as physically taxing as bypass grafting or valve replacement, the potential for surgical complications must be seriously considered, particularly if the patient has diminished physiologic reserve. Case-to-case consideration is also crucial in cardioverter-defibrillator insertion, as the survival benefit may be diminished in older adults, who likely have coexisting illnesses that predispose them to die of a noncardiac cause.15,16

The bottom line is to contemplate multiple factors—severity of the heart failure, comorbidities, baseline functional status, and social support—when assessing the appropriateness of an invasive intervention.

BEYOND DRUGS AND DEVICES: WE CAN DO ‘MORE’

Much of the spotlight has been on the various drugs and devices used to treat heart failure, but of equal importance for frail elderly patients are complementary approaches that can be used to ease disease progression and boost the quality of life. The acronym MORE highlights these strategies.

M: Multidisciplinary management programs

Heart failure disease-management programs are designed to provide comprehensive multidisciplinary care across different settings (ie, home, outpatient, and inpatient) to high-risk patients who often have multiple medical, social, and behavioral issues.9 Interventions usually include intensive patient education, encouraging patients to be more aggressive participants in their care, closely monitoring patients through telephone follow-up or home nursing, carefully reviewing medications to improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines, and multidisciplinary care with nurse case management directed by a physician.

Studies have shown that management programs, which were largely nurse-directed and targeted at older adults and patients with advanced disease, can improve quality of life and functional status, decrease hospitalizations for both heart failure and other causes, and decrease medical costs.17–19

O: Other diseases

R: Restrictions

Specific limitations in the intake of certain dietary elements are a valuable adjunct in heart failure management.

Sodium intake should be restricted to less than 3 g/day by not adding salt to meals and by avoiding salt-rich foods (eg, canned and processed foods).24 During times of distressing volume overload, a tighter sodium limit of 2 g/day is necessary, and diuretics may be less effective if this restriction is not implemented.

Fluid restriction depends on the patient’s clinical status.25 While it is not necessary to limit fluid intake in the absence of retention, a limit of 2 L/day is recommended if edema is detected. If volume overload is severe, the limit should be 1 L/day.

Alcohol is a myocardial depressant that reduces the left ventricular ejection fraction.26 Abstinence is a must for patients with alcohol-induced heart failure; otherwise, a limit of 1 drink (8 oz of beer, 4 oz of wine, or 1 oz of hard liquor) per day is suggested.24

Calories and fat intake are both important to watch, particularly in patients with obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, or coronary artery disease.

E: End-of-life issues

Usual causes of death in patients with heart failure include sudden cardiac death, arrhythmias, hypotension, end-organ hypoperfusion, and metabolic derangement.27,28

Given the life-limiting nature of the disease in frail older adults, it is very important for clinicians to discuss end-of-life matters with patients and their families as early as possible. Needed are effective communication skills that foster respect, empathy, and mutual understanding.

Advance directives. The primary task is to encourage patients to develop advance health directives. These are legal documents that represent patients’ preferences about interventions available toward the end of life such as do-not-resuscitate orders, appointment of surrogate decision-makers, and use of life-sustaining interventions (eg, a feeding tube, dialysis, blood transfusions). Establishing these directives early on will help ease the transition from one mode of care to another (eg, from acute care to hospice care), prevent pointless use of resources (eg, emergency room visits, hospital admissions), and ensure that the patient’s wishes are carried out.

Palliative measures that aim to alleviate suffering and promote quality of life and dignity are available for patients with severe symptoms. For varying degrees of dyspnea, diuretics, nitrates, morphine, and positive inotropic agents such as dobutamine (Dobutrex) and milrinone (Primacor) can be tried. Thoracentesis is done in patients with extensive pleural effusion. Fatigue and anorexia are due to a combination of factors, namely, decreased cardiac output, increased neurohormone levels, deconditioning, depression, decreased sleep, and anxiety.29 Opioids, caffeine, exercise, oxygen, fluid and salt restriction, and correction of anemia and depression may help ease these symptoms.

For patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, deactivation is an important matter that needs to be addressed. Deactivation can be carried out with certainty once the goal of care has shifted away from curative efforts and either the patient or a surrogate decision-maker has made the informed decision to turn the device off. Berger30 raised three points that the clinician and decision-maker can discuss in trying to achieve a resolution during times of doubt and indecision:

- The patient may no longer value continued survival

- The device may no longer offer the prospect of increased survival

- The device may impede active dying.

The idea of hospice care should be gradually and gently explored to ensure a prompt and seamless transition when the time comes. The patient and family need to know that the goal of hospice care is to ensure comfort and that they can benefit the most by enrolling early during the course of the terminal illness.

The Medicare hospice benefit is granted to patients who have been certified by two physicians to have a life expectancy of 6 months or less if their terminal illness runs its natural course. The criteria for determining that heart failure is terminal are:

- New York Heart Association class III (symptomatic with less than ordinary activities) or IV (symptomatic at rest)

- Left ventricular ejection fraction less than or equal to 20%

- Persistent symptoms despite optimal medical management

- Inability to tolerate optional management due to hypotension with or without renal failure.31

WHAT CAN WE DO FOR MR. R.?

Mr. R. has systolic heart failure stemming from coronary artery disease, and his symptoms put him in New York Heart Association class III. He is well managed with drugs of different appropriate classes: an ACE inhibitor, a beta-blocker, digoxin, an aldosterone antagonist, and a diuretic. His other drugs all have well-defined indications.

Since he does not have fluid overload, his furosemide can be stopped, and this change will likely relieve his orthostatic hypotension and nocturia. His systolic blood pressure target can be liberalized to 150 mm Hg or less, as tighter control might exacerbate orthostatic hypotension. This change, along with having him start using a walker instead of a cane, will hopefully prevent future falls. Furthermore, his naproxen should be discontinued, as it can worsen heart failure.

Mr. R. has symptoms of depression and thus needs to be started on an antidepressant and encouraged to engage in social activities as much as he can tolerate. These interventions may also help with his mild dementia, which is evidenced by a Mini-Mental State Exam score of 22. He will not benefit from sodium and fat restriction, as he has actually been losing weight.

To keep Mr. R.’s cognitive impairment and overall decline in function from compromising his compliance with his treatment, he will need a substantial amount of assistance, which his daughter alone may not be able to provide. To tackle this concern, a discussion about participating in a heart failure management program can be started with Mr. R. and his family.

More importantly, his advanced directives, including delegating a surrogate decision-maker and deciding on do-not-resuscitate status, have to be clarified. Finally, it would be prudent to introduce the concept of hospice care to the patient and his daughter while he is still coherent and able to state his preferences.

Mr. R. is an 85-year-old with congestive heart failure; the last time his ejection fraction was measured it was 30%. He also has hypertension, coronary artery disease (for which he underwent triple-vessel coronary artery bypass grafting), osteoarthritis, hyperlipidemia, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He currently takes lisinopril (Zestril), carvedilol (Coreg), aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix), digoxin, simvastatin (Zocor), furosemide (Lasix), an albuterol inhaler (Proventil), and over-the-counter naproxen (Naprosyn), the last two taken as needed.

Accompanied by his daughter, Mr. R. comes to see his primary care physician for a routine follow-up visit. He says he feels fine and has no shortness of breath or chest pain, but he feels light-headed at times, especially when he gets out of bed. He also mentions that he is bothered with having to get up three to four times at night to urinate.

On further questioning, he relates that he uses a cane to walk around the house and gets short of breath when walking from his bed to the bathroom and from one room to the next. He can feed himself, but he needs assistance with bathing and getting dressed.

Mr. R. admits that he has been feeling lonely since his wife died about a year ago. He now lives with his daughter and her family, and they all get along well. His daughter mentions that over the last 6 months he has not been eating well, that he appears to have lost interest in doing some of the things that he used to enjoy, and that he has lost weight. She adds that he has fallen twice in the last month.

On physical examination, Mr. R. is without distress but appears weak. He answers all questions appropriately, although his affect is flat and his daughter fills in some of the details.

Supine, his blood pressure is 160/90 mm Hg and his heart rate is 75; immediately after standing up he feels dizzy and his blood pressure drops to 120/60 mm Hg with a heart rate of 110. Three months ago he weighed 155 pounds (70.3 kg); today he weighs 145 pounds (65.9 kg).

His neck veins are not distended. On chest auscultation, bibasilar coarse crackles are heard, as well as a systolic murmur (grade 2 on a scale of 6), loudest in the second intercostal space at the right parasternal border. No peripheral edema is detected. His Mini-Mental State Exam score is 22 out of 30.

What changes, if any, should be made in Mr. R.’s management? What advice should the primary care physician give Mr. R. and his daughter about the course of his heart failure?

THE IMPORTANCE OF COMPLETE CARE

Mr. R. has multiple convoluted medical issues that plague many elderly patients with heart failure. To provide optimal care to patients like him, physicians need to draw on knowledge from the fields of internal medicine, geriatrics, and cardiology.

In this paper, we discuss how diagnosing and managing heart failure is different in elderly patients. We emphasize the importance of complete care of frail elderly patients, highlighting the pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions that are available. Finally, we will return to Mr. R. and discuss a comprehensive plan for him.

HEART FAILURE, FRAILTY, DISABILITY ARE ALL CONNECTED

The ability to bounce back from physical insults, chiefly medical illnesses, sharply declines in old age. As various stressors accumulate, physical deterioration becomes inevitable. While some older adults can avoid going down this path of morbidity, in an increasing number of frail elderly patients, congestive heart failure inescapably assumes a complicated course.

Frailty is a state of increased vulnerability to stressors due to age-related declines in physiologic reserve.1 Two elements intimately related to frailty are comorbidity and disability.

Fried et al2 analyzed data from more than 5,000 older men and women in the Cardiovascular Health Study and concluded that comorbidity (ie, having two or more chronic diseases) is a risk factor for frailty, which in turn results in disability, falls, hospitalizations, and death.

The relationship between congestive heart failure and frailty is complex. Not only does heart failure itself result in frailty, but its multiple therapies can put additional stress on a frail patient. In addition, the heart failure and its treatments can negatively affect coexisting disorders (Figure 1).

BY THE NUMBERS

Heart failure is largely a disorder of the elderly, and as the US population ages, heart failure is rising in prevalence to epidemic numbers.3 The median age of patients admitted to the hospital because of heart failure is 75,4 and patients age 65 and older account for more than 75% of heart failure hospitalizations.5 Every year, in every 1,000 people over age 65, nearly 10 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed.6

Before age 70, men are affected more than women, but the opposite is true at age 70 and beyond. The reason for this reversal is that women live longer and have a better prognosis, as the cause of heart failure in most women is diastolic dysfunction secondary to hypertension rather than systolic dysfunction due to coronary artery disease, as in most men.7

Heart failure is costly and generally has a poor prognosis. The total cost of treating it reached a staggering $37.2 billion in 2009, and it was the leading cause of Medicare hospital admissions.6 Heart failure is the primary cause or a contributory cause of death in about 290,000 patients each year, and the rate of death at 1 year is an astonishing 1 in 5.6 The median survival time after diagnosis is 2.3 to 3.6 years in patients ages 67 to 74, and it is considerably shorter—1.1 to 1.6 years—in patients age 85 and older.8

THE BROKEN HEART

In 2005, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association defined congestive heart failure as “a complex clinical syndrome that can result from any structural or functional cardiac disorder that impairs the ability of the ventricle to fill with or eject blood.”9 This characterization captures the intricate nature of the disease: its spectrum of symptoms, its many causes (eg, coronary artery disease, hypertension, nonischemic or idiopathic cardiomyopathy, and valvular heart disease), and the dual pathophysiologic features of systolic and diastolic impairment.

Systolic vs diastolic failure

Of the various ways of classifying heart failure, the most important is systolic vs diastolic.

The hallmark of systolic heart failure is a decreased left ventricular ejection fraction, and it is characterized by a large thin-walled ventricle that is weak and unable to eject enough blood to generate a normal cardiac output.

In contrast, the ejection fraction is normal or nearly normal in diastolic heart failure, but the end-diastolic volume is decreased because the ventricle is hypertrophied and thick-walled. The resultant chamber has become small and stiff and does not have enough volume for sufficient cardiac output.

QUIRKS IN THE HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The combination of inactivity and coexisting illnesses in a frail older adult may obscure some of the usual clinical manifestations of heart failure. While shortness of breath on mild exertion, easy fatigability, and leg swelling are common in younger heart failure patients, these symptoms may be due to normal aging in a much older patient. Let us consider some important aspects of the common signs and symptoms associated with heart failure.

Dyspnea on exertion is one of the earliest and most prominent symptoms. The usual question asked of patients to elicit whether this key manifestation is present is, “Do you get short of breath after walking a block?” However, this question may not be appropriate for a frail elderly person whose activity is restricted by comorbidities such as severe arthritis, coronary artery disease, or peripheral arterial disease. For a patient like this, ask instead if he or she gets short of breath after milder forms of exertion, such as making the bed, walking to the bathroom, or changing clothes.10 Also, keep in mind that dyspnea on exertion may be due to other conditions, such as renal failure, lung disease, depression, anemia, or deconditioning.

Orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea may not be volunteered or elicited if a patient is sleeping in a chair or a recliner.

Leg swelling is less specific in older adults than in younger patients because chronic venous insufficiency is common in older people.

Weight gain almost always accompanies symptomatic heart failure but may also be due to increased appetite secondary to depression.

A change in mental status is common in elderly people with heart failure, especially those with vascular dementia with extensive cerebrovascular atherosclerosis or those who have latent Alzheimer disease.10

Cough, a symptom of a multitude of disorders, may be an early or the only manifestation of heart failure.

Pulmonary crackles are typically detected in most heart failure patients, but they may not be as characteristic in older adults, as they may also be noted in bronchitis, pneumonia, and other chronic lung diseases.

Additional symptoms to watch for include fatigue, syncope, angina, nocturia, and oliguria.

The bottom line is to integrate individual findings with other elements of the history and physical examination in diagnosing heart failure and tracking its progression.

CLINCHING THE DIAGNOSIS

Congestive heart failure is essentially a clinical diagnosis best established even before ordering tests, especially during times and situations in which these tests are not always readily available, such as outside office hours and in a long-term care setting.

A reliable and thorough history and physical examination is the most important component of the diagnostic process.

An echocardiogram is obtained next to measure the ejection fraction, which has both prognostic and therapeutic significance. Echocardiography can also uncover potential contributory cardiac structural abnormalities.

A chest radiograph is also typically obtained to look for pulmonary congestion, but in older adults its interpretation may be skewed by chronic lung disease or spinal deformities such as scoliosis and kyphosis.

The B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level is a popular blood test. BNP is commonly elevated in patients with heart failure. However, an elevated level in older adults should always be evaluated within the context of other clinical findings, as it can also result from advancing age and diseases other than heart failure, such as coronary artery disease, chronic pulmonary disease, pulmonary embolism, and renal insufficiency.11,12

PHARMACOTHERAPY PEARLS

Drug treatment for heart failure has evolved rapidly. Robust and sophisticated clinical trials have led to guidelines that call for specific medications. Unfortunately, older patients, particularly the very old and frail, have been poorly represented in these studies.9 Nonetheless, the type and choice of drugs for the young and old are similar.

Take into account age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics

Age-associated changes in pharmacokinetics must be taken into account when prescribing drugs for heart failure.13

Oral absorption of cardiovascular drugs is not significantly affected by the various changes that occur in older adults (eg, reduced gastric acid production, gastric emptying rate, gastrointestinal blood flow, and mobility). However, reductions in both lean body mass and total body water that come with aging result in lower volumes of distribution and higher plasma concentrations of hydrophilic drugs, most notably angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and digoxin. In contrast, the plasma concentrations of lipophilic drugs such as beta-blockers and central alpha-agonists tend to decrease as the proportion of body fat increases in older adults.

As the plasma albumin level diminishes with age, the free-drug concentration of salicylates and warfarin (Coumadin), which are extensively albumin-bound, may increase.

The serum concentrations of cardiovascular drugs metabolized in the liver—eg, propranolol (Inderal), lidocaine, labetalol (Trandate), verapamil (Calan), diltiazem (Cardizem), nitrates, and warfarin—may be elevated due to reduced hepatic blood flow, mass, volume, and overall metabolic capacity.

Declines in renal blood flow, glomerular filtration, and tubular function may cause accumulation of drugs that are excreted through the kidneys.

Beware of toxicities

Table 1 lists some of the drugs used in treating heart failure, common adverse affects to watch for, and recommendations for their use.

WIELDING THE SCALPEL

A tenet of heart failure management is to correct the underlying cardiac structural abnormality. This often calls for invasive intervention along with optimization of drug therapy.

For example:

- Diseased coronary arteries may be amenable to revascularization, either by percutaneous coronary intervention or by the much more involved coronary artery bypass grafting, with the aim of enhancing cardiac function.

- Valves can be repaired or replaced in patients with valvular heart disease.

- A pacemaker can be implanted to remedy sick sinus syndrome, especially with concurrent use of heart-rate-lowering agents such as beta-blockers.

- Placement of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator has been found to be effective in preventing death due to ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with an ejection fraction of less than 30%.9

- Cardiac resynchronization with a biventricular pacemaker may increase the ejection fraction and cardiac output by eliminating dyssynchronous contraction of the left and right ventricles.14

In frail older adults, consideration of these invasive therapies must be individualized. While procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention and pacemaker placement may not be as physically taxing as bypass grafting or valve replacement, the potential for surgical complications must be seriously considered, particularly if the patient has diminished physiologic reserve. Case-to-case consideration is also crucial in cardioverter-defibrillator insertion, as the survival benefit may be diminished in older adults, who likely have coexisting illnesses that predispose them to die of a noncardiac cause.15,16

The bottom line is to contemplate multiple factors—severity of the heart failure, comorbidities, baseline functional status, and social support—when assessing the appropriateness of an invasive intervention.

BEYOND DRUGS AND DEVICES: WE CAN DO ‘MORE’

Much of the spotlight has been on the various drugs and devices used to treat heart failure, but of equal importance for frail elderly patients are complementary approaches that can be used to ease disease progression and boost the quality of life. The acronym MORE highlights these strategies.

M: Multidisciplinary management programs