User login

Defining a Hospitalist's Role in Medicine

Medicine’s Evolution Shouldn’t Undermine Your Expertise, Autonomy, Professionalism

I’m a career hospitalist, yet I struggle to define my role in medicine. Am I still a professional even though I do shift work?

—Randy Robison, DO, Plano, Texas

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Simple question. The short answer is “yes.” The long answer is as follows, so stay with me as we go on a bit of a tangent.

Physicians historically have been categorized as independent professionals, and that was never more true than when most physicians operated in small or solo practices. If you go back even further than that, historically, the three “learned professions” are divinity, medicine, and law. A rough definition encompasses the idea of standard training, a regulatory body (or bodies), and a code of ethics.

Without arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, let’s translate the idea of a profession into something equating autonomy. Professional autonomy can come in many forms. Decision-making at the bedside is a prime example. From a clinical perspective, the advances that we have made in evidence-based medicine are laudable. While some might view the advent of protocols as constraining, I think it allows for a clearer application of science while leaving the art of medicine in the hands of the individual. Others will counter that there’s too much Ritz-Carlton training going on for physicians now, reducing the autonomy of the individual practitioner.

On some level, I’ve been hearing about the “loss of professionalism” in medicine since the day I entered medical school. That said, as a hospitalist in the field of internal medicine, there is not a day that goes by when I don’t have a clinical question with several possible “right” answers. At the same time, there are often varying communication approaches to the patient as well, based on gender, age, education, ethnicity, values, and so on. So I don’t get the sense that autonomy is dead.

There is no doubt that we live in a time of great upheaval in healthcare. Any significant changes can be threatening, especially to a professional. It’s even harder when that independent professional depends on the government as both their greatest source of income and regulation. “Government functionary” and “independent professional” are not exactly ringing synonyms.

Yes, the payment system is in flux. Yes, there is less true autonomy than 20 years ago, and maybe that’s a good thing for our patients. Yes, there are greater expectations for behavior or customer service. Yes, more of us do shift work of some sort than we did before.

Still, there’s no reason to be a lackey, and there’s no reason not to take pride in what you do. Consider these conflicting statements: Show up on time. Question authority. Dress worthy of your calling. Be an individual. Honor the data. Know your own opinion.

At the end of the day, each patient needs you. They need your knowledge, your compassion, your time, and your commitment. It has nothing to do with when your shift starts or when it ends. It has everything to do with the pride you take in your profession. Every patient who has an encounter with a hospitalist should come away thinking, “Wow, that physician is really on the ball. They know all the recent data, they treat me with courtesy and respect, and they have a personality to boot.”

No one should think you’re there just to finish your shift.

Medicine’s Evolution Shouldn’t Undermine Your Expertise, Autonomy, Professionalism

I’m a career hospitalist, yet I struggle to define my role in medicine. Am I still a professional even though I do shift work?

—Randy Robison, DO, Plano, Texas

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Simple question. The short answer is “yes.” The long answer is as follows, so stay with me as we go on a bit of a tangent.

Physicians historically have been categorized as independent professionals, and that was never more true than when most physicians operated in small or solo practices. If you go back even further than that, historically, the three “learned professions” are divinity, medicine, and law. A rough definition encompasses the idea of standard training, a regulatory body (or bodies), and a code of ethics.

Without arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, let’s translate the idea of a profession into something equating autonomy. Professional autonomy can come in many forms. Decision-making at the bedside is a prime example. From a clinical perspective, the advances that we have made in evidence-based medicine are laudable. While some might view the advent of protocols as constraining, I think it allows for a clearer application of science while leaving the art of medicine in the hands of the individual. Others will counter that there’s too much Ritz-Carlton training going on for physicians now, reducing the autonomy of the individual practitioner.

On some level, I’ve been hearing about the “loss of professionalism” in medicine since the day I entered medical school. That said, as a hospitalist in the field of internal medicine, there is not a day that goes by when I don’t have a clinical question with several possible “right” answers. At the same time, there are often varying communication approaches to the patient as well, based on gender, age, education, ethnicity, values, and so on. So I don’t get the sense that autonomy is dead.

There is no doubt that we live in a time of great upheaval in healthcare. Any significant changes can be threatening, especially to a professional. It’s even harder when that independent professional depends on the government as both their greatest source of income and regulation. “Government functionary” and “independent professional” are not exactly ringing synonyms.

Yes, the payment system is in flux. Yes, there is less true autonomy than 20 years ago, and maybe that’s a good thing for our patients. Yes, there are greater expectations for behavior or customer service. Yes, more of us do shift work of some sort than we did before.

Still, there’s no reason to be a lackey, and there’s no reason not to take pride in what you do. Consider these conflicting statements: Show up on time. Question authority. Dress worthy of your calling. Be an individual. Honor the data. Know your own opinion.

At the end of the day, each patient needs you. They need your knowledge, your compassion, your time, and your commitment. It has nothing to do with when your shift starts or when it ends. It has everything to do with the pride you take in your profession. Every patient who has an encounter with a hospitalist should come away thinking, “Wow, that physician is really on the ball. They know all the recent data, they treat me with courtesy and respect, and they have a personality to boot.”

No one should think you’re there just to finish your shift.

Medicine’s Evolution Shouldn’t Undermine Your Expertise, Autonomy, Professionalism

I’m a career hospitalist, yet I struggle to define my role in medicine. Am I still a professional even though I do shift work?

—Randy Robison, DO, Plano, Texas

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Simple question. The short answer is “yes.” The long answer is as follows, so stay with me as we go on a bit of a tangent.

Physicians historically have been categorized as independent professionals, and that was never more true than when most physicians operated in small or solo practices. If you go back even further than that, historically, the three “learned professions” are divinity, medicine, and law. A rough definition encompasses the idea of standard training, a regulatory body (or bodies), and a code of ethics.

Without arguing about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, let’s translate the idea of a profession into something equating autonomy. Professional autonomy can come in many forms. Decision-making at the bedside is a prime example. From a clinical perspective, the advances that we have made in evidence-based medicine are laudable. While some might view the advent of protocols as constraining, I think it allows for a clearer application of science while leaving the art of medicine in the hands of the individual. Others will counter that there’s too much Ritz-Carlton training going on for physicians now, reducing the autonomy of the individual practitioner.

On some level, I’ve been hearing about the “loss of professionalism” in medicine since the day I entered medical school. That said, as a hospitalist in the field of internal medicine, there is not a day that goes by when I don’t have a clinical question with several possible “right” answers. At the same time, there are often varying communication approaches to the patient as well, based on gender, age, education, ethnicity, values, and so on. So I don’t get the sense that autonomy is dead.

There is no doubt that we live in a time of great upheaval in healthcare. Any significant changes can be threatening, especially to a professional. It’s even harder when that independent professional depends on the government as both their greatest source of income and regulation. “Government functionary” and “independent professional” are not exactly ringing synonyms.

Yes, the payment system is in flux. Yes, there is less true autonomy than 20 years ago, and maybe that’s a good thing for our patients. Yes, there are greater expectations for behavior or customer service. Yes, more of us do shift work of some sort than we did before.

Still, there’s no reason to be a lackey, and there’s no reason not to take pride in what you do. Consider these conflicting statements: Show up on time. Question authority. Dress worthy of your calling. Be an individual. Honor the data. Know your own opinion.

At the end of the day, each patient needs you. They need your knowledge, your compassion, your time, and your commitment. It has nothing to do with when your shift starts or when it ends. It has everything to do with the pride you take in your profession. Every patient who has an encounter with a hospitalist should come away thinking, “Wow, that physician is really on the ball. They know all the recent data, they treat me with courtesy and respect, and they have a personality to boot.”

No one should think you’re there just to finish your shift.

The Patient-Centered Medical Home: A Primer

The term “patient-centered medical home” has a nice ring to it, but what does it really mean? And how does it function in the real world? The model is evolving, but here are the main components of the PCMH and how they’ve been implemented in real practice, at least so far:

“PERSONAL” PHYSICIAN: This is the doctor, usually a family or general practice physician, who shepherds patients through the medical system. In practice, this means things like encouraging patient questions about their care, extra efforts to educate patients on their health, and nurses making detailed follow-up calls with patients to make sure they’ve gotten their medications and know how to take them, and communicating any other steps the patient should be taking.

“Whole-person orientation”: The personal physician is responsible for taking care of all of the patient’s medical needs, either himself or by arranging care with specialists. The care ranges from preventive to chronic to end-of-life. In practice, this often means having appointments made with another doctor, if necessary, before the patient leaves the primary-care doctor, or seeing several doctors of different specialties during the same appointment.

Coordinated or integrated care: Care in the PCMH spans all aspects of the healthcare system, from subspecialists to the hospital to the nursing home. In practice, this means the use of electronic registries and health information exchange systems to make sure every health professional has all the information they should have about the patient.

Quality and safety: In practice, it means the development of a care plan that is bolstered by close relationships between patients, doctors, and family members. Plus, a good PCMH will have a more collegial atmosphere, with regular meetings among doctors of varying specialties. Evidence-based medicine is the guide. And feedback from the patient is sought more aggressively. Practices also can undergo a voluntary recognition process by a non-government-related healthcare quality organization, such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Enhanced access: So that patients get the care when they need it, same-day scheduling is often offered. There are expanded hours, and phone and email communication is used more often.

Payment: The payment system in a PCMH encourages better primary care and prevention of illness. Still, most PCMH practices currently use a blend of fee-for-service, a monthly “care coordination” fee, and incentives for quality care.

Source: Adapted from 2007’s Joint Statement on Patient-Centered Medical Home, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

The term “patient-centered medical home” has a nice ring to it, but what does it really mean? And how does it function in the real world? The model is evolving, but here are the main components of the PCMH and how they’ve been implemented in real practice, at least so far:

“PERSONAL” PHYSICIAN: This is the doctor, usually a family or general practice physician, who shepherds patients through the medical system. In practice, this means things like encouraging patient questions about their care, extra efforts to educate patients on their health, and nurses making detailed follow-up calls with patients to make sure they’ve gotten their medications and know how to take them, and communicating any other steps the patient should be taking.

“Whole-person orientation”: The personal physician is responsible for taking care of all of the patient’s medical needs, either himself or by arranging care with specialists. The care ranges from preventive to chronic to end-of-life. In practice, this often means having appointments made with another doctor, if necessary, before the patient leaves the primary-care doctor, or seeing several doctors of different specialties during the same appointment.

Coordinated or integrated care: Care in the PCMH spans all aspects of the healthcare system, from subspecialists to the hospital to the nursing home. In practice, this means the use of electronic registries and health information exchange systems to make sure every health professional has all the information they should have about the patient.

Quality and safety: In practice, it means the development of a care plan that is bolstered by close relationships between patients, doctors, and family members. Plus, a good PCMH will have a more collegial atmosphere, with regular meetings among doctors of varying specialties. Evidence-based medicine is the guide. And feedback from the patient is sought more aggressively. Practices also can undergo a voluntary recognition process by a non-government-related healthcare quality organization, such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Enhanced access: So that patients get the care when they need it, same-day scheduling is often offered. There are expanded hours, and phone and email communication is used more often.

Payment: The payment system in a PCMH encourages better primary care and prevention of illness. Still, most PCMH practices currently use a blend of fee-for-service, a monthly “care coordination” fee, and incentives for quality care.

Source: Adapted from 2007’s Joint Statement on Patient-Centered Medical Home, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

The term “patient-centered medical home” has a nice ring to it, but what does it really mean? And how does it function in the real world? The model is evolving, but here are the main components of the PCMH and how they’ve been implemented in real practice, at least so far:

“PERSONAL” PHYSICIAN: This is the doctor, usually a family or general practice physician, who shepherds patients through the medical system. In practice, this means things like encouraging patient questions about their care, extra efforts to educate patients on their health, and nurses making detailed follow-up calls with patients to make sure they’ve gotten their medications and know how to take them, and communicating any other steps the patient should be taking.

“Whole-person orientation”: The personal physician is responsible for taking care of all of the patient’s medical needs, either himself or by arranging care with specialists. The care ranges from preventive to chronic to end-of-life. In practice, this often means having appointments made with another doctor, if necessary, before the patient leaves the primary-care doctor, or seeing several doctors of different specialties during the same appointment.

Coordinated or integrated care: Care in the PCMH spans all aspects of the healthcare system, from subspecialists to the hospital to the nursing home. In practice, this means the use of electronic registries and health information exchange systems to make sure every health professional has all the information they should have about the patient.

Quality and safety: In practice, it means the development of a care plan that is bolstered by close relationships between patients, doctors, and family members. Plus, a good PCMH will have a more collegial atmosphere, with regular meetings among doctors of varying specialties. Evidence-based medicine is the guide. And feedback from the patient is sought more aggressively. Practices also can undergo a voluntary recognition process by a non-government-related healthcare quality organization, such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Enhanced access: So that patients get the care when they need it, same-day scheduling is often offered. There are expanded hours, and phone and email communication is used more often.

Payment: The payment system in a PCMH encourages better primary care and prevention of illness. Still, most PCMH practices currently use a blend of fee-for-service, a monthly “care coordination” fee, and incentives for quality care.

Source: Adapted from 2007’s Joint Statement on Patient-Centered Medical Home, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Should Hospitalists Be Concerned about the PCHM Model?

If the “patient-centered medical home” model does what it intends to do—makes people healthier and limits preventable illness—fewer people will likely be hospitalized. Should hospitalists be worried? Will that mean less work for hospitalists?

“That clearly is one potential implication of many of the different healthcare reform models, including the development of primary-care medical homes and folks out there who are participating in accountable-care organizations [ACOs], all of which are designed to provide better access to patients on an outpatient setting,” SHM immediate past president Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, says. “The rationale is that it should ultimately lead to fewer hospitalizations.”

Most hospitalists, Dr. Li adds, will say that’s a good thing.

“You’re never going to argue against” fewer hospitalizations, he says. “I think what hospitalists will have to do is they will have to adapt.”

Ultimately, patients who are hospitalized will be sicker, and hospitalists likely will end up seeing those patients several times a day rather than just once or twice, Dr. Li says.

Dr. Meyers, of AHRQ, says inpatient care in the future could become more meaningful, because while there may be fewer patients, those who are hospitalized will need more complex care management.

“I think America’s a big enough country, though, where with an aging population—and we still have lots of chronic disease—there’s going to be no shortage of work, meaningful work, for hospitalists moving forward,” he says.

Dr. Eichhorn, who works in an already up-and-running PCMH system, says patient census shouldn’t be a concern.

“Most hospitalists would probably say that they have plenty of work,” Dr. Eichhorn says. “I think anything that we can do to prevent a hospital stay certainly promotes health and allows us to be better stewards of healthcare resources. And I think it’s a win for everyone.”

If the “patient-centered medical home” model does what it intends to do—makes people healthier and limits preventable illness—fewer people will likely be hospitalized. Should hospitalists be worried? Will that mean less work for hospitalists?

“That clearly is one potential implication of many of the different healthcare reform models, including the development of primary-care medical homes and folks out there who are participating in accountable-care organizations [ACOs], all of which are designed to provide better access to patients on an outpatient setting,” SHM immediate past president Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, says. “The rationale is that it should ultimately lead to fewer hospitalizations.”

Most hospitalists, Dr. Li adds, will say that’s a good thing.

“You’re never going to argue against” fewer hospitalizations, he says. “I think what hospitalists will have to do is they will have to adapt.”

Ultimately, patients who are hospitalized will be sicker, and hospitalists likely will end up seeing those patients several times a day rather than just once or twice, Dr. Li says.

Dr. Meyers, of AHRQ, says inpatient care in the future could become more meaningful, because while there may be fewer patients, those who are hospitalized will need more complex care management.

“I think America’s a big enough country, though, where with an aging population—and we still have lots of chronic disease—there’s going to be no shortage of work, meaningful work, for hospitalists moving forward,” he says.

Dr. Eichhorn, who works in an already up-and-running PCMH system, says patient census shouldn’t be a concern.

“Most hospitalists would probably say that they have plenty of work,” Dr. Eichhorn says. “I think anything that we can do to prevent a hospital stay certainly promotes health and allows us to be better stewards of healthcare resources. And I think it’s a win for everyone.”

If the “patient-centered medical home” model does what it intends to do—makes people healthier and limits preventable illness—fewer people will likely be hospitalized. Should hospitalists be worried? Will that mean less work for hospitalists?

“That clearly is one potential implication of many of the different healthcare reform models, including the development of primary-care medical homes and folks out there who are participating in accountable-care organizations [ACOs], all of which are designed to provide better access to patients on an outpatient setting,” SHM immediate past president Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, says. “The rationale is that it should ultimately lead to fewer hospitalizations.”

Most hospitalists, Dr. Li adds, will say that’s a good thing.

“You’re never going to argue against” fewer hospitalizations, he says. “I think what hospitalists will have to do is they will have to adapt.”

Ultimately, patients who are hospitalized will be sicker, and hospitalists likely will end up seeing those patients several times a day rather than just once or twice, Dr. Li says.

Dr. Meyers, of AHRQ, says inpatient care in the future could become more meaningful, because while there may be fewer patients, those who are hospitalized will need more complex care management.

“I think America’s a big enough country, though, where with an aging population—and we still have lots of chronic disease—there’s going to be no shortage of work, meaningful work, for hospitalists moving forward,” he says.

Dr. Eichhorn, who works in an already up-and-running PCMH system, says patient census shouldn’t be a concern.

“Most hospitalists would probably say that they have plenty of work,” Dr. Eichhorn says. “I think anything that we can do to prevent a hospital stay certainly promotes health and allows us to be better stewards of healthcare resources. And I think it’s a win for everyone.”

Rural Hospitalist Practice: First Among Equals

Louis O’Boyle, DO, FACP, FHM, says hospitalists with an entrepreneurial bent can use flexibility and creativity to design HM programs that meet the unique needs of small or rural hospitals. He owns a hospitalist practice, Advanced Inpatient Medicine, which serves 98-bed Wayne Memorial Hospital in Honesdale, Pa., population 4,874.

“In 2006, the largest group of community physicians locally said they were not going to do hospital coverage or take unassigned hospitalized patients anymore,” Dr. O’Boyle says. The hospital first brought in an out-of-town consultant to provide hospitalist services, but in 2009, Dr. O’Boyle seized the opportunity to fill the need. He formed his own company, which employs five hospitalists providing 24/7 coverage (clinicians rotate between 8 a.m.-to-4 p.m. shifts and 4 p.m.-to-8 a.m. shifts). The hospitalist on duty can often go home after the ED slows down, he says, although hiring a sixth hospitalist would make it easier to provide a 24-hour presence.

“Our hospitalists see an average of 12 patients a day, so we’re not running too hard. You can take time to do a good job, and still have supper with your kids some workdays. In a rural area, you can still get away with that,” Dr. O’Boyle says. “We have a good salary, work schedule, and caseload. We have a great team, with everyone on board with what we’re trying to do.”

Members of Dr. O’Boyle’s group sit on all of the hospital’s committees. Many have a say in changes that go on at the hospital. The group is active in quality and safety projects and research on readmission rates. The program has been so successful that he is negotiating to cover several other hospitals in the region.

“Another key to the success of this program is our fiscal responsibility, demonstrating the value we bring to the hospital,” he says. “We align our goals with the hospital’s goals. We have cut length of stay by an average of three-quarters of a day. We were very involved with the IT department in setting up EHR and CPOE to our specifications. There is a whole list of things we do to justify our worth, and our subsidy payment from the hospital is particularly low.”

Dr. O’Boyle, in addition to his practice-management responsibilities, works alongside his colleagues. “It’s not like I’m the boss—more like I’m first among equals,” he says. “We meet as a team once a month.”

Louis O’Boyle, DO, FACP, FHM, says hospitalists with an entrepreneurial bent can use flexibility and creativity to design HM programs that meet the unique needs of small or rural hospitals. He owns a hospitalist practice, Advanced Inpatient Medicine, which serves 98-bed Wayne Memorial Hospital in Honesdale, Pa., population 4,874.

“In 2006, the largest group of community physicians locally said they were not going to do hospital coverage or take unassigned hospitalized patients anymore,” Dr. O’Boyle says. The hospital first brought in an out-of-town consultant to provide hospitalist services, but in 2009, Dr. O’Boyle seized the opportunity to fill the need. He formed his own company, which employs five hospitalists providing 24/7 coverage (clinicians rotate between 8 a.m.-to-4 p.m. shifts and 4 p.m.-to-8 a.m. shifts). The hospitalist on duty can often go home after the ED slows down, he says, although hiring a sixth hospitalist would make it easier to provide a 24-hour presence.

“Our hospitalists see an average of 12 patients a day, so we’re not running too hard. You can take time to do a good job, and still have supper with your kids some workdays. In a rural area, you can still get away with that,” Dr. O’Boyle says. “We have a good salary, work schedule, and caseload. We have a great team, with everyone on board with what we’re trying to do.”

Members of Dr. O’Boyle’s group sit on all of the hospital’s committees. Many have a say in changes that go on at the hospital. The group is active in quality and safety projects and research on readmission rates. The program has been so successful that he is negotiating to cover several other hospitals in the region.

“Another key to the success of this program is our fiscal responsibility, demonstrating the value we bring to the hospital,” he says. “We align our goals with the hospital’s goals. We have cut length of stay by an average of three-quarters of a day. We were very involved with the IT department in setting up EHR and CPOE to our specifications. There is a whole list of things we do to justify our worth, and our subsidy payment from the hospital is particularly low.”

Dr. O’Boyle, in addition to his practice-management responsibilities, works alongside his colleagues. “It’s not like I’m the boss—more like I’m first among equals,” he says. “We meet as a team once a month.”

Louis O’Boyle, DO, FACP, FHM, says hospitalists with an entrepreneurial bent can use flexibility and creativity to design HM programs that meet the unique needs of small or rural hospitals. He owns a hospitalist practice, Advanced Inpatient Medicine, which serves 98-bed Wayne Memorial Hospital in Honesdale, Pa., population 4,874.

“In 2006, the largest group of community physicians locally said they were not going to do hospital coverage or take unassigned hospitalized patients anymore,” Dr. O’Boyle says. The hospital first brought in an out-of-town consultant to provide hospitalist services, but in 2009, Dr. O’Boyle seized the opportunity to fill the need. He formed his own company, which employs five hospitalists providing 24/7 coverage (clinicians rotate between 8 a.m.-to-4 p.m. shifts and 4 p.m.-to-8 a.m. shifts). The hospitalist on duty can often go home after the ED slows down, he says, although hiring a sixth hospitalist would make it easier to provide a 24-hour presence.

“Our hospitalists see an average of 12 patients a day, so we’re not running too hard. You can take time to do a good job, and still have supper with your kids some workdays. In a rural area, you can still get away with that,” Dr. O’Boyle says. “We have a good salary, work schedule, and caseload. We have a great team, with everyone on board with what we’re trying to do.”

Members of Dr. O’Boyle’s group sit on all of the hospital’s committees. Many have a say in changes that go on at the hospital. The group is active in quality and safety projects and research on readmission rates. The program has been so successful that he is negotiating to cover several other hospitals in the region.

“Another key to the success of this program is our fiscal responsibility, demonstrating the value we bring to the hospital,” he says. “We align our goals with the hospital’s goals. We have cut length of stay by an average of three-quarters of a day. We were very involved with the IT department in setting up EHR and CPOE to our specifications. There is a whole list of things we do to justify our worth, and our subsidy payment from the hospital is particularly low.”

Dr. O’Boyle, in addition to his practice-management responsibilities, works alongside his colleagues. “It’s not like I’m the boss—more like I’m first among equals,” he says. “We meet as a team once a month.”

Rural Healthcare Facts

The obstacles faced by healthcare providers and patients in rural areas are vastly different than those in urban areas. Rural Americans face a unique combination of factors that create disparities in healthcare not found in urban areas:

- Only about 10% of physicians practice in rural America despite the fact that nearly one-fourth of the population lives in these areas.

- Rural residents tend to be poorer. On the average, per capita income is $7,417 lower than in urban areas, and rural Americans are more likely to live below the poverty line. The disparity in incomes is even greater for minorities living in rural areas. Nearly 24% of rural children live in poverty.

- Hypertension is higher in rural than urban areas (101.3 per 1,000 individuals in MSAs and 128.8 per 1,000 individuals in non-MSAs).

- 20% of nonmetropolitan counties lack mental health services, compared with 5% of metropolitan counties.

- Medicare payments to rural hospitals and physicians are dramatically less than those to their urban counterparts for equivalent services. And more than 470 rural hospitals have closed in the past 25 years.

- Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who were treated in rural hospitals were less likely than those treated in urban hospitals to receive recommended treatments and had significantly higher adjusted 30-day post-AMI death rates from all causes than those in urban hospitals.

- Rural residents have greater transportation difficulties reaching healthcare providers, often traveling great distances to reach a doctor or hospital.

Source: www.ruralhealthweb.org

The obstacles faced by healthcare providers and patients in rural areas are vastly different than those in urban areas. Rural Americans face a unique combination of factors that create disparities in healthcare not found in urban areas:

- Only about 10% of physicians practice in rural America despite the fact that nearly one-fourth of the population lives in these areas.

- Rural residents tend to be poorer. On the average, per capita income is $7,417 lower than in urban areas, and rural Americans are more likely to live below the poverty line. The disparity in incomes is even greater for minorities living in rural areas. Nearly 24% of rural children live in poverty.

- Hypertension is higher in rural than urban areas (101.3 per 1,000 individuals in MSAs and 128.8 per 1,000 individuals in non-MSAs).

- 20% of nonmetropolitan counties lack mental health services, compared with 5% of metropolitan counties.

- Medicare payments to rural hospitals and physicians are dramatically less than those to their urban counterparts for equivalent services. And more than 470 rural hospitals have closed in the past 25 years.

- Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who were treated in rural hospitals were less likely than those treated in urban hospitals to receive recommended treatments and had significantly higher adjusted 30-day post-AMI death rates from all causes than those in urban hospitals.

- Rural residents have greater transportation difficulties reaching healthcare providers, often traveling great distances to reach a doctor or hospital.

Source: www.ruralhealthweb.org

The obstacles faced by healthcare providers and patients in rural areas are vastly different than those in urban areas. Rural Americans face a unique combination of factors that create disparities in healthcare not found in urban areas:

- Only about 10% of physicians practice in rural America despite the fact that nearly one-fourth of the population lives in these areas.

- Rural residents tend to be poorer. On the average, per capita income is $7,417 lower than in urban areas, and rural Americans are more likely to live below the poverty line. The disparity in incomes is even greater for minorities living in rural areas. Nearly 24% of rural children live in poverty.

- Hypertension is higher in rural than urban areas (101.3 per 1,000 individuals in MSAs and 128.8 per 1,000 individuals in non-MSAs).

- 20% of nonmetropolitan counties lack mental health services, compared with 5% of metropolitan counties.

- Medicare payments to rural hospitals and physicians are dramatically less than those to their urban counterparts for equivalent services. And more than 470 rural hospitals have closed in the past 25 years.

- Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) who were treated in rural hospitals were less likely than those treated in urban hospitals to receive recommended treatments and had significantly higher adjusted 30-day post-AMI death rates from all causes than those in urban hospitals.

- Rural residents have greater transportation difficulties reaching healthcare providers, often traveling great distances to reach a doctor or hospital.

Source: www.ruralhealthweb.org

Resources for the Rural Hospitalist

SHM immediate past president Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, practices hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, but Oklahoma is where he grew up, went to medical school, and performed rural rotations. Some parts of hospitalist practice are the same at big and small hospitals, urban and rural settings, he says.

“Recruitment of high-quality physicians is always a challenge,” Dr. Li says. “That’s where SHM can help.”

SHM’s Career Center, official publications, and the SHM annual meeting are excellent avenues for recruitment, Dr. Li says. SHM also offers online practice-management tools and a variety of collaborative resources—SQUINT, a searchable repository of innovative QI methods and systems, and an electronic QI toolkit known as eQUIPS—to help rural hospitalists.

Based in Kansas City, the National Rural Health Association (www.ruralhealthweb.org) provides additional resources for small, rural hospitals. The NRHA is working with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT and 62 Regional Extension Centers to help rural providers with EHR adoption and implementation, guiding them to meet meaningful-use standards.

“NRHA is a member organization with multiple constituencies,” says Brock Slabach, senior vice president for member services. “If anybody in hospital medicine works in a rural community and wants to connect with an organization like ours, we don’t have a lot of hospitalist members, but we would welcome them.”

SHM immediate past president Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, practices hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, but Oklahoma is where he grew up, went to medical school, and performed rural rotations. Some parts of hospitalist practice are the same at big and small hospitals, urban and rural settings, he says.

“Recruitment of high-quality physicians is always a challenge,” Dr. Li says. “That’s where SHM can help.”

SHM’s Career Center, official publications, and the SHM annual meeting are excellent avenues for recruitment, Dr. Li says. SHM also offers online practice-management tools and a variety of collaborative resources—SQUINT, a searchable repository of innovative QI methods and systems, and an electronic QI toolkit known as eQUIPS—to help rural hospitalists.

Based in Kansas City, the National Rural Health Association (www.ruralhealthweb.org) provides additional resources for small, rural hospitals. The NRHA is working with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT and 62 Regional Extension Centers to help rural providers with EHR adoption and implementation, guiding them to meet meaningful-use standards.

“NRHA is a member organization with multiple constituencies,” says Brock Slabach, senior vice president for member services. “If anybody in hospital medicine works in a rural community and wants to connect with an organization like ours, we don’t have a lot of hospitalist members, but we would welcome them.”

SHM immediate past president Joseph Ming Wah Li, MD, SFHM, practices hospital medicine at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, but Oklahoma is where he grew up, went to medical school, and performed rural rotations. Some parts of hospitalist practice are the same at big and small hospitals, urban and rural settings, he says.

“Recruitment of high-quality physicians is always a challenge,” Dr. Li says. “That’s where SHM can help.”

SHM’s Career Center, official publications, and the SHM annual meeting are excellent avenues for recruitment, Dr. Li says. SHM also offers online practice-management tools and a variety of collaborative resources—SQUINT, a searchable repository of innovative QI methods and systems, and an electronic QI toolkit known as eQUIPS—to help rural hospitalists.

Based in Kansas City, the National Rural Health Association (www.ruralhealthweb.org) provides additional resources for small, rural hospitals. The NRHA is working with the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT and 62 Regional Extension Centers to help rural providers with EHR adoption and implementation, guiding them to meet meaningful-use standards.

“NRHA is a member organization with multiple constituencies,” says Brock Slabach, senior vice president for member services. “If anybody in hospital medicine works in a rural community and wants to connect with an organization like ours, we don’t have a lot of hospitalist members, but we would welcome them.”

Evaluating a Hospitalist: A New Way of Measurement

Medicine in the past 10-20 years has seen major changes driven by changes in payment systems, lifestyle changes, and changes in training patterns. One such change is the hospitalist model of medicine. The advent of hospitalist practice has turned work-life balance on its head, as far as medicine is concerned.

All along, professionalism required that we pay unquestionable attention to the patient, the profession, and the organization—reporting early to work, staying until the work is done, taking work home, and answering the phone on the nights when we were on call. On weekends, finishing pending dictation was normal. The 20-minute mill of outpatient practice has driven primary medicine to a breaking point.

As the pressures of the primary-care job got worse, there came an exit in the form of the hospitalist model. HM provided shift work that could be adjusted to the needs of the physician.

This new kind of job, however, has its own problems. Physicians choosing the normalcy of shift work did not realize that they would give up professional independence. Hospitalists now are governed by the laws of shift work, and at the same time remain governed by the laws of their profession. It is likely when in need they will stay behind and get the work done. And it has been seen that hospitalists do visit the doctors’ lounge, have professional interests outside of direct patient care, and sometimes leave the hospital when their admits and discharges are complete.

And so the shift-work model has, at times, resulted in friction between hospital administration and hospitalists. It could be understood that, from an employer’s perspective, hospitals are paying on an hourly basis and thus expect the hospitalist group to be on site 24/7, sticking around even if there is no work. However, the argument from the hospitalist perspective is that when needed, I stay extra. It should be OK that on low-census days we should be able to leave for a cup of coffee and still be reachable, ready to come in if need arises.

So how do hospitalist-physician professionalism and shift work co-exist? It’s a big question, one that organizations around the country will be looking to solve in the next few years. How this question is answered is going to impact quality of care, recruitment, and staff satisfaction. Each answer will impact the staff and patients.

Keeping in mind outcomes that both parties are looking for, I think a proper plan can be worked out. I suggest hospital administrators adopt the following value-based measurements to evaluate hospitalist clinicians, and establish a compensation system where a minimum amount of production must be met.

Work relative value units (wRVUs). Work RVUs provide a consistent method to measure physician productivity. If one HM clinician’s numbers are below the group average, they might need a lesson in billing, along with a report of their productivity numbers and group expectations.

Patient encounters per day. The average number of patients seen per day (patients seen divided by number of shifts worked) should be measured on a quarterly basis. This metric should provide a measure of the work done by the physician; however, it needs to be offset by your group’s turnover rate (as discussed below).

Length of stay (LOS). Most HM groups are measuring LOS. It is the reason hospitalists exist. Not much more needs to be said about this measure of work performance.

Percentage of patient turnover. A good hospitalist will have a high patient turnover figure (total discharges divided by total encounters per day). This is important to know; it’s even better if accompanied by a short LOS.

New admissions per shift. Again, if there is an outlier, that metric should be detected rather easily.

Patient satisfaction. More and more, this is becoming an important measure of physician quality and is essential for competitive marketplaces. Of course, the quality of medical care will have its own parameters. And it is best left to use the existing, longstanding parameters that are used for the rest of the doctors in your system. There is no need to create an alternative system for the hospitalist.

If all of the above measures are better than the average hospitalist in the locality, then no one should worry about the hospitalist’s other activities, be it involvement in committee work, research, or browsing a newspaper or a cup of coffee in the doctors’ lounge. After all, one of the main reasons physicians opted for HM practice was to have the ability to control their workday.

This will, in my opinion, improve workforce satisfaction and improve productivity. It only makes common sense. It may be a hard pill to swallow for the administrators, but it is the right medicine for the doctor.

Rwoof Reshi, MD, hospitalist, St. Joe’s Hospital, St. Paul, Minn.

Medicine in the past 10-20 years has seen major changes driven by changes in payment systems, lifestyle changes, and changes in training patterns. One such change is the hospitalist model of medicine. The advent of hospitalist practice has turned work-life balance on its head, as far as medicine is concerned.

All along, professionalism required that we pay unquestionable attention to the patient, the profession, and the organization—reporting early to work, staying until the work is done, taking work home, and answering the phone on the nights when we were on call. On weekends, finishing pending dictation was normal. The 20-minute mill of outpatient practice has driven primary medicine to a breaking point.

As the pressures of the primary-care job got worse, there came an exit in the form of the hospitalist model. HM provided shift work that could be adjusted to the needs of the physician.

This new kind of job, however, has its own problems. Physicians choosing the normalcy of shift work did not realize that they would give up professional independence. Hospitalists now are governed by the laws of shift work, and at the same time remain governed by the laws of their profession. It is likely when in need they will stay behind and get the work done. And it has been seen that hospitalists do visit the doctors’ lounge, have professional interests outside of direct patient care, and sometimes leave the hospital when their admits and discharges are complete.

And so the shift-work model has, at times, resulted in friction between hospital administration and hospitalists. It could be understood that, from an employer’s perspective, hospitals are paying on an hourly basis and thus expect the hospitalist group to be on site 24/7, sticking around even if there is no work. However, the argument from the hospitalist perspective is that when needed, I stay extra. It should be OK that on low-census days we should be able to leave for a cup of coffee and still be reachable, ready to come in if need arises.

So how do hospitalist-physician professionalism and shift work co-exist? It’s a big question, one that organizations around the country will be looking to solve in the next few years. How this question is answered is going to impact quality of care, recruitment, and staff satisfaction. Each answer will impact the staff and patients.

Keeping in mind outcomes that both parties are looking for, I think a proper plan can be worked out. I suggest hospital administrators adopt the following value-based measurements to evaluate hospitalist clinicians, and establish a compensation system where a minimum amount of production must be met.

Work relative value units (wRVUs). Work RVUs provide a consistent method to measure physician productivity. If one HM clinician’s numbers are below the group average, they might need a lesson in billing, along with a report of their productivity numbers and group expectations.

Patient encounters per day. The average number of patients seen per day (patients seen divided by number of shifts worked) should be measured on a quarterly basis. This metric should provide a measure of the work done by the physician; however, it needs to be offset by your group’s turnover rate (as discussed below).

Length of stay (LOS). Most HM groups are measuring LOS. It is the reason hospitalists exist. Not much more needs to be said about this measure of work performance.

Percentage of patient turnover. A good hospitalist will have a high patient turnover figure (total discharges divided by total encounters per day). This is important to know; it’s even better if accompanied by a short LOS.

New admissions per shift. Again, if there is an outlier, that metric should be detected rather easily.

Patient satisfaction. More and more, this is becoming an important measure of physician quality and is essential for competitive marketplaces. Of course, the quality of medical care will have its own parameters. And it is best left to use the existing, longstanding parameters that are used for the rest of the doctors in your system. There is no need to create an alternative system for the hospitalist.

If all of the above measures are better than the average hospitalist in the locality, then no one should worry about the hospitalist’s other activities, be it involvement in committee work, research, or browsing a newspaper or a cup of coffee in the doctors’ lounge. After all, one of the main reasons physicians opted for HM practice was to have the ability to control their workday.

This will, in my opinion, improve workforce satisfaction and improve productivity. It only makes common sense. It may be a hard pill to swallow for the administrators, but it is the right medicine for the doctor.

Rwoof Reshi, MD, hospitalist, St. Joe’s Hospital, St. Paul, Minn.

Medicine in the past 10-20 years has seen major changes driven by changes in payment systems, lifestyle changes, and changes in training patterns. One such change is the hospitalist model of medicine. The advent of hospitalist practice has turned work-life balance on its head, as far as medicine is concerned.

All along, professionalism required that we pay unquestionable attention to the patient, the profession, and the organization—reporting early to work, staying until the work is done, taking work home, and answering the phone on the nights when we were on call. On weekends, finishing pending dictation was normal. The 20-minute mill of outpatient practice has driven primary medicine to a breaking point.

As the pressures of the primary-care job got worse, there came an exit in the form of the hospitalist model. HM provided shift work that could be adjusted to the needs of the physician.

This new kind of job, however, has its own problems. Physicians choosing the normalcy of shift work did not realize that they would give up professional independence. Hospitalists now are governed by the laws of shift work, and at the same time remain governed by the laws of their profession. It is likely when in need they will stay behind and get the work done. And it has been seen that hospitalists do visit the doctors’ lounge, have professional interests outside of direct patient care, and sometimes leave the hospital when their admits and discharges are complete.

And so the shift-work model has, at times, resulted in friction between hospital administration and hospitalists. It could be understood that, from an employer’s perspective, hospitals are paying on an hourly basis and thus expect the hospitalist group to be on site 24/7, sticking around even if there is no work. However, the argument from the hospitalist perspective is that when needed, I stay extra. It should be OK that on low-census days we should be able to leave for a cup of coffee and still be reachable, ready to come in if need arises.

So how do hospitalist-physician professionalism and shift work co-exist? It’s a big question, one that organizations around the country will be looking to solve in the next few years. How this question is answered is going to impact quality of care, recruitment, and staff satisfaction. Each answer will impact the staff and patients.

Keeping in mind outcomes that both parties are looking for, I think a proper plan can be worked out. I suggest hospital administrators adopt the following value-based measurements to evaluate hospitalist clinicians, and establish a compensation system where a minimum amount of production must be met.

Work relative value units (wRVUs). Work RVUs provide a consistent method to measure physician productivity. If one HM clinician’s numbers are below the group average, they might need a lesson in billing, along with a report of their productivity numbers and group expectations.

Patient encounters per day. The average number of patients seen per day (patients seen divided by number of shifts worked) should be measured on a quarterly basis. This metric should provide a measure of the work done by the physician; however, it needs to be offset by your group’s turnover rate (as discussed below).

Length of stay (LOS). Most HM groups are measuring LOS. It is the reason hospitalists exist. Not much more needs to be said about this measure of work performance.

Percentage of patient turnover. A good hospitalist will have a high patient turnover figure (total discharges divided by total encounters per day). This is important to know; it’s even better if accompanied by a short LOS.

New admissions per shift. Again, if there is an outlier, that metric should be detected rather easily.

Patient satisfaction. More and more, this is becoming an important measure of physician quality and is essential for competitive marketplaces. Of course, the quality of medical care will have its own parameters. And it is best left to use the existing, longstanding parameters that are used for the rest of the doctors in your system. There is no need to create an alternative system for the hospitalist.

If all of the above measures are better than the average hospitalist in the locality, then no one should worry about the hospitalist’s other activities, be it involvement in committee work, research, or browsing a newspaper or a cup of coffee in the doctors’ lounge. After all, one of the main reasons physicians opted for HM practice was to have the ability to control their workday.

This will, in my opinion, improve workforce satisfaction and improve productivity. It only makes common sense. It may be a hard pill to swallow for the administrators, but it is the right medicine for the doctor.

Rwoof Reshi, MD, hospitalist, St. Joe’s Hospital, St. Paul, Minn.

Despite efficacy, most patients discontinued therapy

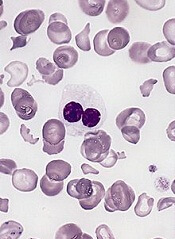

In a multicenter trial, deferasirox reduced serum ferritin and labile plasma iron (LPI) in transfusion-dependent patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). A subset of patients also experienced improvements in hematologic parameters.

In spite of these results, nearly 80% of patients discontinued therapy. But researchers said only about 40% of the discontinuations were drug-related; ie, a result of adverse events, abnormal lab values, or drug inefficacy.

Alan F. List, MD, of the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The team’s research was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, the maker of deferasirox.

The researchers analyzed the effects of the drug in 173 patients with low- or intermediate-1-risk MDS. The median patient age was 71 years (range, 21 to 90 years).

Patients had serum ferritin of at least 1000 μg/L, had received at least 20 units of red blood cells, and had ongoing transfusion requirements. The starting dose of deferasirox was 20 mg/kg per day, with dose escalation up to 40 mg/kg per day.

Patients who completed 1 year of therapy (n=91) experienced a median decrease in serum ferritin of 23%. Serum ferritin decreased by 36.7% in patients who completed 2 years of therapy (n=49) and 36.5% in patients who completed 3 years of therapy (n=33).

The investigators measured LPI quarterly during the first year of the study. Nearly 40% of patients (n=68) had elevated LPI at baseline. But, by week 13, LPI levels had normalized in all of the patients.

Twenty-eight percent of patients (n=51) experienced hematologic improvements according to International Working Group 2006 criteria. However, 7 of these patients had received growth factors or MDS therapy.

By the end of the study period, 79.8% of patients (n=138) had discontinued therapy. The reasons included adverse events in 24.8% (n=43), death in 16.1% (n=28), administrative problems in 15.4% (n=27), and abnormal lab values in 13.2% (n=23).

In addition, 6.9% of patients (n=12) chose not to enroll in the extension phase of the study, and 1.7% of patients (n=3) reported an unsatisfactory therapeutic effect. In 1.1% of cases (n=2), the patient no longer required the drug.

The most common drug-related adverse events were gastrointestinal disturbances and increased serum creatinine. Of the 28 patient deaths, none were linked to deferasirox.

“Overall, this study demonstrated improvements in iron parameters in a group of heavily transfused, lower-risk patients with MDS,” Dr List said. “A randomized trial is warranted to better ascertain the clinical impact of deferasirox therapy in lower-risk patients with MDS.” ![]()

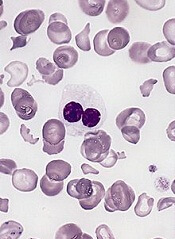

In a multicenter trial, deferasirox reduced serum ferritin and labile plasma iron (LPI) in transfusion-dependent patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). A subset of patients also experienced improvements in hematologic parameters.

In spite of these results, nearly 80% of patients discontinued therapy. But researchers said only about 40% of the discontinuations were drug-related; ie, a result of adverse events, abnormal lab values, or drug inefficacy.

Alan F. List, MD, of the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The team’s research was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, the maker of deferasirox.

The researchers analyzed the effects of the drug in 173 patients with low- or intermediate-1-risk MDS. The median patient age was 71 years (range, 21 to 90 years).

Patients had serum ferritin of at least 1000 μg/L, had received at least 20 units of red blood cells, and had ongoing transfusion requirements. The starting dose of deferasirox was 20 mg/kg per day, with dose escalation up to 40 mg/kg per day.

Patients who completed 1 year of therapy (n=91) experienced a median decrease in serum ferritin of 23%. Serum ferritin decreased by 36.7% in patients who completed 2 years of therapy (n=49) and 36.5% in patients who completed 3 years of therapy (n=33).

The investigators measured LPI quarterly during the first year of the study. Nearly 40% of patients (n=68) had elevated LPI at baseline. But, by week 13, LPI levels had normalized in all of the patients.

Twenty-eight percent of patients (n=51) experienced hematologic improvements according to International Working Group 2006 criteria. However, 7 of these patients had received growth factors or MDS therapy.

By the end of the study period, 79.8% of patients (n=138) had discontinued therapy. The reasons included adverse events in 24.8% (n=43), death in 16.1% (n=28), administrative problems in 15.4% (n=27), and abnormal lab values in 13.2% (n=23).

In addition, 6.9% of patients (n=12) chose not to enroll in the extension phase of the study, and 1.7% of patients (n=3) reported an unsatisfactory therapeutic effect. In 1.1% of cases (n=2), the patient no longer required the drug.

The most common drug-related adverse events were gastrointestinal disturbances and increased serum creatinine. Of the 28 patient deaths, none were linked to deferasirox.

“Overall, this study demonstrated improvements in iron parameters in a group of heavily transfused, lower-risk patients with MDS,” Dr List said. “A randomized trial is warranted to better ascertain the clinical impact of deferasirox therapy in lower-risk patients with MDS.” ![]()

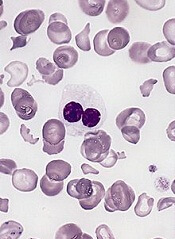

In a multicenter trial, deferasirox reduced serum ferritin and labile plasma iron (LPI) in transfusion-dependent patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). A subset of patients also experienced improvements in hematologic parameters.

In spite of these results, nearly 80% of patients discontinued therapy. But researchers said only about 40% of the discontinuations were drug-related; ie, a result of adverse events, abnormal lab values, or drug inefficacy.

Alan F. List, MD, of the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The team’s research was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals, the maker of deferasirox.

The researchers analyzed the effects of the drug in 173 patients with low- or intermediate-1-risk MDS. The median patient age was 71 years (range, 21 to 90 years).

Patients had serum ferritin of at least 1000 μg/L, had received at least 20 units of red blood cells, and had ongoing transfusion requirements. The starting dose of deferasirox was 20 mg/kg per day, with dose escalation up to 40 mg/kg per day.

Patients who completed 1 year of therapy (n=91) experienced a median decrease in serum ferritin of 23%. Serum ferritin decreased by 36.7% in patients who completed 2 years of therapy (n=49) and 36.5% in patients who completed 3 years of therapy (n=33).

The investigators measured LPI quarterly during the first year of the study. Nearly 40% of patients (n=68) had elevated LPI at baseline. But, by week 13, LPI levels had normalized in all of the patients.

Twenty-eight percent of patients (n=51) experienced hematologic improvements according to International Working Group 2006 criteria. However, 7 of these patients had received growth factors or MDS therapy.

By the end of the study period, 79.8% of patients (n=138) had discontinued therapy. The reasons included adverse events in 24.8% (n=43), death in 16.1% (n=28), administrative problems in 15.4% (n=27), and abnormal lab values in 13.2% (n=23).

In addition, 6.9% of patients (n=12) chose not to enroll in the extension phase of the study, and 1.7% of patients (n=3) reported an unsatisfactory therapeutic effect. In 1.1% of cases (n=2), the patient no longer required the drug.

The most common drug-related adverse events were gastrointestinal disturbances and increased serum creatinine. Of the 28 patient deaths, none were linked to deferasirox.

“Overall, this study demonstrated improvements in iron parameters in a group of heavily transfused, lower-risk patients with MDS,” Dr List said. “A randomized trial is warranted to better ascertain the clinical impact of deferasirox therapy in lower-risk patients with MDS.” ![]()

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: International Clinicians Can Bolster Rural HM Group Recruiting Efforts

Where do rural hospitals look if they are having trouble attracting hospitalists to their communities—and keeping them there? One target should be graduates of international medical schools. Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, director of Inpatient Physician Associates in Lincoln, Neb., estimates that he has recruited 40 physicians to HM practice at the three hospitals his group serves, and at least a dozen of them were international medical graduates (IMGs).

Dr. Bossard works closely with a specialized immigration attorney, Elahe Najfabadi of the Offices of Carl Shusterman in Los Angeles. “There are lots of barriers to address to negotiate positive outcomes,” Dr. Bossard says. “You need an attorney you can rely on thoroughly.”

—Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, director of Inpatient Physician Associates in Lincoln, Neb.

There are basically two categories of visas for IMGs: H-1B visas, which are capped nationally but allow doctors the flexibility to move around, and J-1 visas, which allow clinicians to remain in the U.S. while completing their medical studies. J-1 visas expire after two years, but physicians often are granted waivers and remain in the U.S.

According to Najfabadi, each state is allowed 30 physician J-1 visa waivers annually. Physicians must work in underserved areas, including rural communities, and those physicians must stay in the job for three years.

When it comes to the J-1 waiver program, timelines, deadlines, requirements for employers, and other regulations vary by state.

“In one state, we’ve had cases where the state wants verification of the doctor’s approved immigration status before issuing the medical license,” Najfabadi says.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service requires a valid license or a letter from the state that the physician is eligible in order to grant an H-1B permit. Najfabadi encourages potential rural employers of IMGs to learn the rules in their state, and to take advantage of such resources such as the IMG Task Force (http://www.imgtaskforce.org/).

“What I have found is that we get exceedingly high-quality physicians to provide care in rural communities,” Dr. Bossard says. “I love working with them.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Where do rural hospitals look if they are having trouble attracting hospitalists to their communities—and keeping them there? One target should be graduates of international medical schools. Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, director of Inpatient Physician Associates in Lincoln, Neb., estimates that he has recruited 40 physicians to HM practice at the three hospitals his group serves, and at least a dozen of them were international medical graduates (IMGs).

Dr. Bossard works closely with a specialized immigration attorney, Elahe Najfabadi of the Offices of Carl Shusterman in Los Angeles. “There are lots of barriers to address to negotiate positive outcomes,” Dr. Bossard says. “You need an attorney you can rely on thoroughly.”

—Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, director of Inpatient Physician Associates in Lincoln, Neb.

There are basically two categories of visas for IMGs: H-1B visas, which are capped nationally but allow doctors the flexibility to move around, and J-1 visas, which allow clinicians to remain in the U.S. while completing their medical studies. J-1 visas expire after two years, but physicians often are granted waivers and remain in the U.S.

According to Najfabadi, each state is allowed 30 physician J-1 visa waivers annually. Physicians must work in underserved areas, including rural communities, and those physicians must stay in the job for three years.

When it comes to the J-1 waiver program, timelines, deadlines, requirements for employers, and other regulations vary by state.

“In one state, we’ve had cases where the state wants verification of the doctor’s approved immigration status before issuing the medical license,” Najfabadi says.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service requires a valid license or a letter from the state that the physician is eligible in order to grant an H-1B permit. Najfabadi encourages potential rural employers of IMGs to learn the rules in their state, and to take advantage of such resources such as the IMG Task Force (http://www.imgtaskforce.org/).

“What I have found is that we get exceedingly high-quality physicians to provide care in rural communities,” Dr. Bossard says. “I love working with them.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Where do rural hospitals look if they are having trouble attracting hospitalists to their communities—and keeping them there? One target should be graduates of international medical schools. Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, director of Inpatient Physician Associates in Lincoln, Neb., estimates that he has recruited 40 physicians to HM practice at the three hospitals his group serves, and at least a dozen of them were international medical graduates (IMGs).

Dr. Bossard works closely with a specialized immigration attorney, Elahe Najfabadi of the Offices of Carl Shusterman in Los Angeles. “There are lots of barriers to address to negotiate positive outcomes,” Dr. Bossard says. “You need an attorney you can rely on thoroughly.”

—Brian Bossard, MD, FACP, FHM, director of Inpatient Physician Associates in Lincoln, Neb.

There are basically two categories of visas for IMGs: H-1B visas, which are capped nationally but allow doctors the flexibility to move around, and J-1 visas, which allow clinicians to remain in the U.S. while completing their medical studies. J-1 visas expire after two years, but physicians often are granted waivers and remain in the U.S.

According to Najfabadi, each state is allowed 30 physician J-1 visa waivers annually. Physicians must work in underserved areas, including rural communities, and those physicians must stay in the job for three years.

When it comes to the J-1 waiver program, timelines, deadlines, requirements for employers, and other regulations vary by state.

“In one state, we’ve had cases where the state wants verification of the doctor’s approved immigration status before issuing the medical license,” Najfabadi says.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service requires a valid license or a letter from the state that the physician is eligible in order to grant an H-1B permit. Najfabadi encourages potential rural employers of IMGs to learn the rules in their state, and to take advantage of such resources such as the IMG Task Force (http://www.imgtaskforce.org/).

“What I have found is that we get exceedingly high-quality physicians to provide care in rural communities,” Dr. Bossard says. “I love working with them.”

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Patient-centered Medical Home (PCMH) appears to reduce hospitalizations, but AHRQ says good evidence still lacking

An evaluation of the Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System’s ProvenHealth Navigator, a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model, found that hospitalizations have been reduced by 18% for all patients.1

The National Institutes on Aging-sponsored project Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE), which also functioned according to several PCMH principles, reduced hospitalizations by 40% and 44% in its second and third years, another evaluation showed.2,3

And in the Veterans Affairs-managed Home-Based Primary Care project, another PCMH-based effort, readmissions were reduced by 22% in the first six months, but the reduction wasn’t sustained for the rest of the year.4

Those findings are among the most definitive so far on the effects of the PCMH on hospitalization rates, according to an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report published in February.

The report concluded that among the statistically significant findings in the biggest PCMH evaluations, favorable results far outnumbered unfavorable results—on outcomes, ED use, and patient experience.

But AHRQ also found that most studies have been inconclusive due to problems with their methodologies. For instance, many studies don’t factor in “clustering,” in which patient outcomes within a practice can be expected to be similar to that of other patients at that practice. AHRQ’s report evaluated the results only from studies it determined had methodologies that were sufficiently rigorous.

The evaluation of the GRACE project was the only evaluation that found any evidence of savings, according to the report. But that study was one of only four on the topic that were deemed worth consideration.

David Meyers, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care, Prevention, and Clinical Partnerships at AHRQ, points out that the systems that have been evaluated are the very earliest adopters of PCMH principles. Researchers estimate that it could take 10 years to get reliable results.

“The good news,” Dr. Meyers says, “is that there are a lot more demonstrations happening now, so we soon will have a lot more guidance about how to make this model work.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

1. Gilfillan RJ, Tomcavage J, Rosenthal MB, et al. Value and the medical home: Effects of transformed primary care. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):607-614.

2. Bielaszka-DuVernay, et al. The “GRACE” model: in-home assessments lead to better care for dual eligibles. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):431-434.

3. Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TE, Arling GW. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1420-1426.

4. Hughes SL, Weaver FM, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care: a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2877-2885.

An evaluation of the Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System’s ProvenHealth Navigator, a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model, found that hospitalizations have been reduced by 18% for all patients.1

The National Institutes on Aging-sponsored project Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE), which also functioned according to several PCMH principles, reduced hospitalizations by 40% and 44% in its second and third years, another evaluation showed.2,3

And in the Veterans Affairs-managed Home-Based Primary Care project, another PCMH-based effort, readmissions were reduced by 22% in the first six months, but the reduction wasn’t sustained for the rest of the year.4

Those findings are among the most definitive so far on the effects of the PCMH on hospitalization rates, according to an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report published in February.

The report concluded that among the statistically significant findings in the biggest PCMH evaluations, favorable results far outnumbered unfavorable results—on outcomes, ED use, and patient experience.

But AHRQ also found that most studies have been inconclusive due to problems with their methodologies. For instance, many studies don’t factor in “clustering,” in which patient outcomes within a practice can be expected to be similar to that of other patients at that practice. AHRQ’s report evaluated the results only from studies it determined had methodologies that were sufficiently rigorous.

The evaluation of the GRACE project was the only evaluation that found any evidence of savings, according to the report. But that study was one of only four on the topic that were deemed worth consideration.

David Meyers, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care, Prevention, and Clinical Partnerships at AHRQ, points out that the systems that have been evaluated are the very earliest adopters of PCMH principles. Researchers estimate that it could take 10 years to get reliable results.

“The good news,” Dr. Meyers says, “is that there are a lot more demonstrations happening now, so we soon will have a lot more guidance about how to make this model work.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

1. Gilfillan RJ, Tomcavage J, Rosenthal MB, et al. Value and the medical home: Effects of transformed primary care. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):607-614.

2. Bielaszka-DuVernay, et al. The “GRACE” model: in-home assessments lead to better care for dual eligibles. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):431-434.

3. Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Tu W, Stump TE, Arling GW. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1420-1426.

4. Hughes SL, Weaver FM, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care: a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2877-2885.

An evaluation of the Pennsylvania-based Geisinger Health System’s ProvenHealth Navigator, a patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model, found that hospitalizations have been reduced by 18% for all patients.1

The National Institutes on Aging-sponsored project Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE), which also functioned according to several PCMH principles, reduced hospitalizations by 40% and 44% in its second and third years, another evaluation showed.2,3

And in the Veterans Affairs-managed Home-Based Primary Care project, another PCMH-based effort, readmissions were reduced by 22% in the first six months, but the reduction wasn’t sustained for the rest of the year.4

Those findings are among the most definitive so far on the effects of the PCMH on hospitalization rates, according to an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) report published in February.

The report concluded that among the statistically significant findings in the biggest PCMH evaluations, favorable results far outnumbered unfavorable results—on outcomes, ED use, and patient experience.

But AHRQ also found that most studies have been inconclusive due to problems with their methodologies. For instance, many studies don’t factor in “clustering,” in which patient outcomes within a practice can be expected to be similar to that of other patients at that practice. AHRQ’s report evaluated the results only from studies it determined had methodologies that were sufficiently rigorous.

The evaluation of the GRACE project was the only evaluation that found any evidence of savings, according to the report. But that study was one of only four on the topic that were deemed worth consideration.

David Meyers, MD, director of the Center for Primary Care, Prevention, and Clinical Partnerships at AHRQ, points out that the systems that have been evaluated are the very earliest adopters of PCMH principles. Researchers estimate that it could take 10 years to get reliable results.

“The good news,” Dr. Meyers says, “is that there are a lot more demonstrations happening now, so we soon will have a lot more guidance about how to make this model work.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

1. Gilfillan RJ, Tomcavage J, Rosenthal MB, et al. Value and the medical home: Effects of transformed primary care. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):607-614.