User login

How is Graves' Disease Diagnosed and Evaluated?

Case

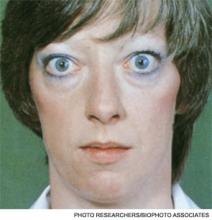

A 25-year-old, previously healthy woman presents with one month of anxiety, palpitations, intermittent loose non-dysenteriform stools, fine tremors, and hair loss. She has had a 20-pound weight loss in the previous four months, even though she reports an increased appetite. Her heart rate ranges from 115 to 130 beats per minute, and her temperature is 37.5oC. An exam is notable for mild bilateral proptosis, thin hair, and moist skin. A goiter is visible; it has increased consistency on palpation with an audible bruit over it. She has hyperreflexia and fine tremors. An EKG reveals sinus tachycardia. How should this patient be evaluated? What treatment should be initiated?

Overview

Graves’ disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is caused by autoimmune stimulation of the thyrotropin (TSH) receptor. It generally presents with a variety of signs and symptoms found with hyperthyroidism, but it can also carry unique clinical features unrelated to thyrotoxicosis, such as ophthalmopathy and dermopathy.

Graves’ disease diagnosis mainly is clinical, but also is supported by elevated free levels of thyroid hormones (mainly triiodothyronine [T3]) and suppressed TSH levels. Anti-thyrotropin receptor antibodies generally are present. Imaging in Graves’ disease is characterized by increased radioiodine uptake, as well as increased perfusion by Doppler ultrasonography.

Treatment can be pharmacologic, using anti-thyroid drugs, or ablative, with either radioiodine or thyroidectomy. Adjunctive therapy includes symptom control with beta-blocker agents, as well as steroid supplementation, especially in patients with orbitopathy undergoing radioablative treatment.

The Data

Epidemiology. Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, with a prevalence of ~0.5% of the population. Women are most commonly affected, with a prevalence five to 10 times higher than in male peers. The most common age of presentation is between the fifth and sixth decades of life.1-3

The fact that Graves’ disease occurs with higher incidence in patients with a family history of thyroid disease—and that concordance rates of up to 35% are seen with monozygotic twins—suggests that both genetic and environmental factors influence disease susceptibility.2,4

Pathophysiology. Graves’ disease occurs as a result of direct activation of the G-protein-coupled adenylate cyclase in the thyrotropin receptor by circulating IgG antibodies.2,3 Follicular hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and increased vascularity, cause goiter formation and an increased production of T3 and thyroxine (T4). The increase in T3 and T4 subsequently suppress TSH production.

Graves’ disease also is associated with unique clinical manifestations unrelated to the circulating levels of thyroid hormones, such as Graves’ ophthalmopathy and infiltrative dermopathy (localized or pretibial myxedema). Both of these occur as a result of local tissue infiltration by inflammatory cells and deposition of glycosaminglycanes.5

Clinical manifestations. Graves’ disease is characterized by a constellation of clinical findings and patient symptoms (see Table 1).1-3 The clinical presentation could differ in elderly patients, who present more commonly with weight loss or depression (also known as apathetic hyperthyroidism) and less commonly with tachycardia and tremor.2,3

Although clinically apparent, exophtalmos is detected in 30% to 50% of patients; when using orbital imaging, it is identified in ≥80% of patients.5 Ophthalmopathy has a clinical course typically independent of the thyroid activity; its manifestations include proptosis, periorbital edema and inflammation, exposure keratitis, photophobia, extraocular muscle infiltration, and eyelid lag.5-8

Thyroid dermopathy (localized dermal myxedema) can occur in 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with Graves’ disease; it occurs most commonly among patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy, in whom it occurs in up to 13% of cases. About 20% of patients with dermal myxedema have associated thyroid acropachy.3,9

Hospitalists should be aware of thyroid storm. Although rare, occurring in only 1% to 2% of patients with hyperthyroidism, it can be a medical emergency. It is generally manifested by fever (due to severe thermogenesis), atrial tachyarrhythmias (due to hyperadrenergic response), mental status changes, and liver dysfunction.

In addition, patients with thyroid storm might present with hyperglycemia, hypercalcemia, hypocortisolism, and hypokalemia.10 Thyroid storm requires prompt treatment of both the clinical manifestations and the underlying condition.

Differential Diagnosis from Other Causes of Thyroiditis

Laboratory. The classic presentation of Graves’ disease is a suppressed TSH and elevated serum T3 and T4 levels.1-3 Generally, T3 is higher than T4, which also occurs in toxic multinodular goiter, solitary hyperfunctioning nodule, and iodine-induced hyperthyroidism.2,6 The free T3 and T4 levels should be obtained, as these are useful for monitoring response to therapy.1-3

Most patients with Graves’ disease also have anti-thyroid antibodies (see Table 2), although these are not required for the diagnosis.1-3,11

Following initiation of treatment, TSH levels remain suppressed for approximately two to three months, even after free T3 and T4 levels return to normal or below normal. After this period of suppression is over, TSH levels can be used to adjust therapy.1-3

Imaging. A thyroid radioiodine-uptake study provides a measure of iodine uptake, as well as an image of functioning thyroid tissue; the imaging is done 24 hours after the intake of iodine-123 or iodine-131. Generalized increased uptake is characteristic of Graves’ disease.1-3,12 In comparison, patients with thyroiditis have decreased radioiodine uptake as well as low blood flow in Doppler ultrasonography.13

In patients with large goiters, when there are signs or symptoms of upper airway or thoracic outlet obstruction, imaging with a neck and upper-chest CT scan is recommended.2 In patients with unilateral proptosis, asymmetric ophthalmopathy, or visual loss, orbital imaging is advised (CT scan or MRI).2,5 In patients with tachyarrhythmias, an electrocardiogram should evaluate for the presence of atrial fibrillation.2 Table 2 illustrates how Graves’ disease can be distinguished from other causes of thyroiditis.1-3

Initial Treatment

Treatment of Graves’ disease has two main tenets: treating the underlying thyroid disorder and quickly controlling symptoms. The underlying thyroid disorder can be treated with such anti-thyroid drugs as thionamides (methimazole or propylthiouracil), ablative radioiodine, or surgical excision of the thyroid. Adjunct symptom therapy can include beta-blockers, organic iodide, and glucocorticoids.11,14 Thionamides are preferred in young patients, pregnant women, and cases with orbital involvement.14

In pregnancy, treatment with propylthiouracil is preferred, especially during the first two trimesters due to the risk of teratogenicity with methimazole (there have been associated case reports of choanal atresia, aplasia cutis, and facial malformations).15

Steroid prophylaxis is used in patients with prominent ocular symptoms who undergo radioiodine ablation to minimize risk of worsening of ophthalmopathy.16

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted; free T3 and T4 levels were elevated, TSH was suppressed, and anti-thyroid antibodies (anti-TPO, anti-TG, and anti-TRAb) were positive. An I-123 radioiodine uptake scan showed diffuse thyroid gland uptake. Beta-blockers were initiated for heart-rate control (atenolol 25 mg) with adequate response.

Given the patient’s young age, it was decided to initiate thionamides. A pregnancy test was negative, so methimazole was initiated at a dose of 10 mg orally once daily.

Dr. Auron is a hospitalist in the Department of Hospital Medicine and the Center for Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Hamilton is a hospitalist in the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Baskin HJ, Cobin RH, Duick DS, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. (2006 Amended version). Endocr Pract. 2002;8:457-469.

- Brent GA. Clinical practice. Graves’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2594-2605.

- Nayak B, Hodak SP. Hyperthyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:617-656.

- Manji N, Carr-Smith JD, Boelaert K, et al. Influences of age, gender, smoking, and family history on autoimmune thyroid disease phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4873-4880.

- Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726-738.

- Woeber KA. Triiodothyronine production in Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Thyroid. 2006;16:687-690.

- Osman F, Franklyn JA, Holder RL, Sheppard MC, Gammage MD. Cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism before and after antithyroid therapy: a matched case-control study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:71-81.

- Wiersinga WM, Bartalena L. Epidemiology and prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2002;12:855-860.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Chong HW, See KC, Phua J. Thyroid storm with multiorgan failure. Thyroid. 2010;20:333-336.

- De Groot L. Diagnosis and treatment of Graves’ disease. Thyroid Disease Manager website. Available at: http://www.thyroidmanager.org/chapter/diagnosis-and-treatment-of-graves-disease/. Accessed Jan. 20, 2012.

- Cappelli C, Pirola I, De Martino E, et al. The role of imaging in Graves’ disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:99-103.

- Ota H, Amino N, Morita S, et al. Quantitative measurement of thyroid blood flow for differentiation of painless thyroiditis from Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;67:41-45.

- Fumarola A, Di Fiore A, Dainelli M, Grani G, Calvanese A. Medical treatment of hyperthyroidism: state of the art. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:678-684.

- Fitzpatrick DL, Russell MA. Diagnosis and management of thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37:173-193.

- Bartalena L. The dilemma of how to manage Graves’ hyperthyroidism in patients with associated orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:592-599.

Case

A 25-year-old, previously healthy woman presents with one month of anxiety, palpitations, intermittent loose non-dysenteriform stools, fine tremors, and hair loss. She has had a 20-pound weight loss in the previous four months, even though she reports an increased appetite. Her heart rate ranges from 115 to 130 beats per minute, and her temperature is 37.5oC. An exam is notable for mild bilateral proptosis, thin hair, and moist skin. A goiter is visible; it has increased consistency on palpation with an audible bruit over it. She has hyperreflexia and fine tremors. An EKG reveals sinus tachycardia. How should this patient be evaluated? What treatment should be initiated?

Overview

Graves’ disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is caused by autoimmune stimulation of the thyrotropin (TSH) receptor. It generally presents with a variety of signs and symptoms found with hyperthyroidism, but it can also carry unique clinical features unrelated to thyrotoxicosis, such as ophthalmopathy and dermopathy.

Graves’ disease diagnosis mainly is clinical, but also is supported by elevated free levels of thyroid hormones (mainly triiodothyronine [T3]) and suppressed TSH levels. Anti-thyrotropin receptor antibodies generally are present. Imaging in Graves’ disease is characterized by increased radioiodine uptake, as well as increased perfusion by Doppler ultrasonography.

Treatment can be pharmacologic, using anti-thyroid drugs, or ablative, with either radioiodine or thyroidectomy. Adjunctive therapy includes symptom control with beta-blocker agents, as well as steroid supplementation, especially in patients with orbitopathy undergoing radioablative treatment.

The Data

Epidemiology. Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, with a prevalence of ~0.5% of the population. Women are most commonly affected, with a prevalence five to 10 times higher than in male peers. The most common age of presentation is between the fifth and sixth decades of life.1-3

The fact that Graves’ disease occurs with higher incidence in patients with a family history of thyroid disease—and that concordance rates of up to 35% are seen with monozygotic twins—suggests that both genetic and environmental factors influence disease susceptibility.2,4

Pathophysiology. Graves’ disease occurs as a result of direct activation of the G-protein-coupled adenylate cyclase in the thyrotropin receptor by circulating IgG antibodies.2,3 Follicular hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and increased vascularity, cause goiter formation and an increased production of T3 and thyroxine (T4). The increase in T3 and T4 subsequently suppress TSH production.

Graves’ disease also is associated with unique clinical manifestations unrelated to the circulating levels of thyroid hormones, such as Graves’ ophthalmopathy and infiltrative dermopathy (localized or pretibial myxedema). Both of these occur as a result of local tissue infiltration by inflammatory cells and deposition of glycosaminglycanes.5

Clinical manifestations. Graves’ disease is characterized by a constellation of clinical findings and patient symptoms (see Table 1).1-3 The clinical presentation could differ in elderly patients, who present more commonly with weight loss or depression (also known as apathetic hyperthyroidism) and less commonly with tachycardia and tremor.2,3

Although clinically apparent, exophtalmos is detected in 30% to 50% of patients; when using orbital imaging, it is identified in ≥80% of patients.5 Ophthalmopathy has a clinical course typically independent of the thyroid activity; its manifestations include proptosis, periorbital edema and inflammation, exposure keratitis, photophobia, extraocular muscle infiltration, and eyelid lag.5-8

Thyroid dermopathy (localized dermal myxedema) can occur in 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with Graves’ disease; it occurs most commonly among patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy, in whom it occurs in up to 13% of cases. About 20% of patients with dermal myxedema have associated thyroid acropachy.3,9

Hospitalists should be aware of thyroid storm. Although rare, occurring in only 1% to 2% of patients with hyperthyroidism, it can be a medical emergency. It is generally manifested by fever (due to severe thermogenesis), atrial tachyarrhythmias (due to hyperadrenergic response), mental status changes, and liver dysfunction.

In addition, patients with thyroid storm might present with hyperglycemia, hypercalcemia, hypocortisolism, and hypokalemia.10 Thyroid storm requires prompt treatment of both the clinical manifestations and the underlying condition.

Differential Diagnosis from Other Causes of Thyroiditis

Laboratory. The classic presentation of Graves’ disease is a suppressed TSH and elevated serum T3 and T4 levels.1-3 Generally, T3 is higher than T4, which also occurs in toxic multinodular goiter, solitary hyperfunctioning nodule, and iodine-induced hyperthyroidism.2,6 The free T3 and T4 levels should be obtained, as these are useful for monitoring response to therapy.1-3

Most patients with Graves’ disease also have anti-thyroid antibodies (see Table 2), although these are not required for the diagnosis.1-3,11

Following initiation of treatment, TSH levels remain suppressed for approximately two to three months, even after free T3 and T4 levels return to normal or below normal. After this period of suppression is over, TSH levels can be used to adjust therapy.1-3

Imaging. A thyroid radioiodine-uptake study provides a measure of iodine uptake, as well as an image of functioning thyroid tissue; the imaging is done 24 hours after the intake of iodine-123 or iodine-131. Generalized increased uptake is characteristic of Graves’ disease.1-3,12 In comparison, patients with thyroiditis have decreased radioiodine uptake as well as low blood flow in Doppler ultrasonography.13

In patients with large goiters, when there are signs or symptoms of upper airway or thoracic outlet obstruction, imaging with a neck and upper-chest CT scan is recommended.2 In patients with unilateral proptosis, asymmetric ophthalmopathy, or visual loss, orbital imaging is advised (CT scan or MRI).2,5 In patients with tachyarrhythmias, an electrocardiogram should evaluate for the presence of atrial fibrillation.2 Table 2 illustrates how Graves’ disease can be distinguished from other causes of thyroiditis.1-3

Initial Treatment

Treatment of Graves’ disease has two main tenets: treating the underlying thyroid disorder and quickly controlling symptoms. The underlying thyroid disorder can be treated with such anti-thyroid drugs as thionamides (methimazole or propylthiouracil), ablative radioiodine, or surgical excision of the thyroid. Adjunct symptom therapy can include beta-blockers, organic iodide, and glucocorticoids.11,14 Thionamides are preferred in young patients, pregnant women, and cases with orbital involvement.14

In pregnancy, treatment with propylthiouracil is preferred, especially during the first two trimesters due to the risk of teratogenicity with methimazole (there have been associated case reports of choanal atresia, aplasia cutis, and facial malformations).15

Steroid prophylaxis is used in patients with prominent ocular symptoms who undergo radioiodine ablation to minimize risk of worsening of ophthalmopathy.16

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted; free T3 and T4 levels were elevated, TSH was suppressed, and anti-thyroid antibodies (anti-TPO, anti-TG, and anti-TRAb) were positive. An I-123 radioiodine uptake scan showed diffuse thyroid gland uptake. Beta-blockers were initiated for heart-rate control (atenolol 25 mg) with adequate response.

Given the patient’s young age, it was decided to initiate thionamides. A pregnancy test was negative, so methimazole was initiated at a dose of 10 mg orally once daily.

Dr. Auron is a hospitalist in the Department of Hospital Medicine and the Center for Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Hamilton is a hospitalist in the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Baskin HJ, Cobin RH, Duick DS, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. (2006 Amended version). Endocr Pract. 2002;8:457-469.

- Brent GA. Clinical practice. Graves’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2594-2605.

- Nayak B, Hodak SP. Hyperthyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:617-656.

- Manji N, Carr-Smith JD, Boelaert K, et al. Influences of age, gender, smoking, and family history on autoimmune thyroid disease phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4873-4880.

- Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726-738.

- Woeber KA. Triiodothyronine production in Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Thyroid. 2006;16:687-690.

- Osman F, Franklyn JA, Holder RL, Sheppard MC, Gammage MD. Cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism before and after antithyroid therapy: a matched case-control study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:71-81.

- Wiersinga WM, Bartalena L. Epidemiology and prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2002;12:855-860.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Chong HW, See KC, Phua J. Thyroid storm with multiorgan failure. Thyroid. 2010;20:333-336.

- De Groot L. Diagnosis and treatment of Graves’ disease. Thyroid Disease Manager website. Available at: http://www.thyroidmanager.org/chapter/diagnosis-and-treatment-of-graves-disease/. Accessed Jan. 20, 2012.

- Cappelli C, Pirola I, De Martino E, et al. The role of imaging in Graves’ disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:99-103.

- Ota H, Amino N, Morita S, et al. Quantitative measurement of thyroid blood flow for differentiation of painless thyroiditis from Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;67:41-45.

- Fumarola A, Di Fiore A, Dainelli M, Grani G, Calvanese A. Medical treatment of hyperthyroidism: state of the art. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:678-684.

- Fitzpatrick DL, Russell MA. Diagnosis and management of thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37:173-193.

- Bartalena L. The dilemma of how to manage Graves’ hyperthyroidism in patients with associated orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:592-599.

Case

A 25-year-old, previously healthy woman presents with one month of anxiety, palpitations, intermittent loose non-dysenteriform stools, fine tremors, and hair loss. She has had a 20-pound weight loss in the previous four months, even though she reports an increased appetite. Her heart rate ranges from 115 to 130 beats per minute, and her temperature is 37.5oC. An exam is notable for mild bilateral proptosis, thin hair, and moist skin. A goiter is visible; it has increased consistency on palpation with an audible bruit over it. She has hyperreflexia and fine tremors. An EKG reveals sinus tachycardia. How should this patient be evaluated? What treatment should be initiated?

Overview

Graves’ disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, is caused by autoimmune stimulation of the thyrotropin (TSH) receptor. It generally presents with a variety of signs and symptoms found with hyperthyroidism, but it can also carry unique clinical features unrelated to thyrotoxicosis, such as ophthalmopathy and dermopathy.

Graves’ disease diagnosis mainly is clinical, but also is supported by elevated free levels of thyroid hormones (mainly triiodothyronine [T3]) and suppressed TSH levels. Anti-thyrotropin receptor antibodies generally are present. Imaging in Graves’ disease is characterized by increased radioiodine uptake, as well as increased perfusion by Doppler ultrasonography.

Treatment can be pharmacologic, using anti-thyroid drugs, or ablative, with either radioiodine or thyroidectomy. Adjunctive therapy includes symptom control with beta-blocker agents, as well as steroid supplementation, especially in patients with orbitopathy undergoing radioablative treatment.

The Data

Epidemiology. Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, with a prevalence of ~0.5% of the population. Women are most commonly affected, with a prevalence five to 10 times higher than in male peers. The most common age of presentation is between the fifth and sixth decades of life.1-3

The fact that Graves’ disease occurs with higher incidence in patients with a family history of thyroid disease—and that concordance rates of up to 35% are seen with monozygotic twins—suggests that both genetic and environmental factors influence disease susceptibility.2,4

Pathophysiology. Graves’ disease occurs as a result of direct activation of the G-protein-coupled adenylate cyclase in the thyrotropin receptor by circulating IgG antibodies.2,3 Follicular hypertrophy and hyperplasia, and increased vascularity, cause goiter formation and an increased production of T3 and thyroxine (T4). The increase in T3 and T4 subsequently suppress TSH production.

Graves’ disease also is associated with unique clinical manifestations unrelated to the circulating levels of thyroid hormones, such as Graves’ ophthalmopathy and infiltrative dermopathy (localized or pretibial myxedema). Both of these occur as a result of local tissue infiltration by inflammatory cells and deposition of glycosaminglycanes.5

Clinical manifestations. Graves’ disease is characterized by a constellation of clinical findings and patient symptoms (see Table 1).1-3 The clinical presentation could differ in elderly patients, who present more commonly with weight loss or depression (also known as apathetic hyperthyroidism) and less commonly with tachycardia and tremor.2,3

Although clinically apparent, exophtalmos is detected in 30% to 50% of patients; when using orbital imaging, it is identified in ≥80% of patients.5 Ophthalmopathy has a clinical course typically independent of the thyroid activity; its manifestations include proptosis, periorbital edema and inflammation, exposure keratitis, photophobia, extraocular muscle infiltration, and eyelid lag.5-8

Thyroid dermopathy (localized dermal myxedema) can occur in 0.5% to 4.3% of patients with Graves’ disease; it occurs most commonly among patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy, in whom it occurs in up to 13% of cases. About 20% of patients with dermal myxedema have associated thyroid acropachy.3,9

Hospitalists should be aware of thyroid storm. Although rare, occurring in only 1% to 2% of patients with hyperthyroidism, it can be a medical emergency. It is generally manifested by fever (due to severe thermogenesis), atrial tachyarrhythmias (due to hyperadrenergic response), mental status changes, and liver dysfunction.

In addition, patients with thyroid storm might present with hyperglycemia, hypercalcemia, hypocortisolism, and hypokalemia.10 Thyroid storm requires prompt treatment of both the clinical manifestations and the underlying condition.

Differential Diagnosis from Other Causes of Thyroiditis

Laboratory. The classic presentation of Graves’ disease is a suppressed TSH and elevated serum T3 and T4 levels.1-3 Generally, T3 is higher than T4, which also occurs in toxic multinodular goiter, solitary hyperfunctioning nodule, and iodine-induced hyperthyroidism.2,6 The free T3 and T4 levels should be obtained, as these are useful for monitoring response to therapy.1-3

Most patients with Graves’ disease also have anti-thyroid antibodies (see Table 2), although these are not required for the diagnosis.1-3,11

Following initiation of treatment, TSH levels remain suppressed for approximately two to three months, even after free T3 and T4 levels return to normal or below normal. After this period of suppression is over, TSH levels can be used to adjust therapy.1-3

Imaging. A thyroid radioiodine-uptake study provides a measure of iodine uptake, as well as an image of functioning thyroid tissue; the imaging is done 24 hours after the intake of iodine-123 or iodine-131. Generalized increased uptake is characteristic of Graves’ disease.1-3,12 In comparison, patients with thyroiditis have decreased radioiodine uptake as well as low blood flow in Doppler ultrasonography.13

In patients with large goiters, when there are signs or symptoms of upper airway or thoracic outlet obstruction, imaging with a neck and upper-chest CT scan is recommended.2 In patients with unilateral proptosis, asymmetric ophthalmopathy, or visual loss, orbital imaging is advised (CT scan or MRI).2,5 In patients with tachyarrhythmias, an electrocardiogram should evaluate for the presence of atrial fibrillation.2 Table 2 illustrates how Graves’ disease can be distinguished from other causes of thyroiditis.1-3

Initial Treatment

Treatment of Graves’ disease has two main tenets: treating the underlying thyroid disorder and quickly controlling symptoms. The underlying thyroid disorder can be treated with such anti-thyroid drugs as thionamides (methimazole or propylthiouracil), ablative radioiodine, or surgical excision of the thyroid. Adjunct symptom therapy can include beta-blockers, organic iodide, and glucocorticoids.11,14 Thionamides are preferred in young patients, pregnant women, and cases with orbital involvement.14

In pregnancy, treatment with propylthiouracil is preferred, especially during the first two trimesters due to the risk of teratogenicity with methimazole (there have been associated case reports of choanal atresia, aplasia cutis, and facial malformations).15

Steroid prophylaxis is used in patients with prominent ocular symptoms who undergo radioiodine ablation to minimize risk of worsening of ophthalmopathy.16

Back to the Case

The patient was admitted; free T3 and T4 levels were elevated, TSH was suppressed, and anti-thyroid antibodies (anti-TPO, anti-TG, and anti-TRAb) were positive. An I-123 radioiodine uptake scan showed diffuse thyroid gland uptake. Beta-blockers were initiated for heart-rate control (atenolol 25 mg) with adequate response.

Given the patient’s young age, it was decided to initiate thionamides. A pregnancy test was negative, so methimazole was initiated at a dose of 10 mg orally once daily.

Dr. Auron is a hospitalist in the Department of Hospital Medicine and the Center for Pediatric Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic. Dr. Hamilton is a hospitalist in the Department of Hospital Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

References

- Baskin HJ, Cobin RH, Duick DS, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. (2006 Amended version). Endocr Pract. 2002;8:457-469.

- Brent GA. Clinical practice. Graves’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2594-2605.

- Nayak B, Hodak SP. Hyperthyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:617-656.

- Manji N, Carr-Smith JD, Boelaert K, et al. Influences of age, gender, smoking, and family history on autoimmune thyroid disease phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4873-4880.

- Bahn RS. Graves’ ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726-738.

- Woeber KA. Triiodothyronine production in Graves’ hyperthyroidism. Thyroid. 2006;16:687-690.

- Osman F, Franklyn JA, Holder RL, Sheppard MC, Gammage MD. Cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism before and after antithyroid therapy: a matched case-control study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:71-81.

- Wiersinga WM, Bartalena L. Epidemiology and prevention of Graves’ ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2002;12:855-860.

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309.

- Chong HW, See KC, Phua J. Thyroid storm with multiorgan failure. Thyroid. 2010;20:333-336.

- De Groot L. Diagnosis and treatment of Graves’ disease. Thyroid Disease Manager website. Available at: http://www.thyroidmanager.org/chapter/diagnosis-and-treatment-of-graves-disease/. Accessed Jan. 20, 2012.

- Cappelli C, Pirola I, De Martino E, et al. The role of imaging in Graves’ disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:99-103.

- Ota H, Amino N, Morita S, et al. Quantitative measurement of thyroid blood flow for differentiation of painless thyroiditis from Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;67:41-45.

- Fumarola A, Di Fiore A, Dainelli M, Grani G, Calvanese A. Medical treatment of hyperthyroidism: state of the art. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:678-684.

- Fitzpatrick DL, Russell MA. Diagnosis and management of thyroid disease in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2010;37:173-193.

- Bartalena L. The dilemma of how to manage Graves’ hyperthyroidism in patients with associated orbitopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:592-599.

Hospitalists On the Move

Hospitalist Martha Buckley, MD, was named the 2011 Gordon B. Snider, MD, Physician Teammate of the Year among her peers at Fairfield Medical Center (FMC) in Lancaster, Ohio. Dr. Buckley has been a hospitalist at FMC for two years as part of Colonnade Medical Group, also based in Lancaster.

Hospitalist Scott Stuart, MD, has assumed the role of medical director for the PCU and care management at Evergreen Hospital in Kirkland, Wash. Dr. Stuart has worked for Evergreen as an internal-medicine hospitalist since 2005, and previously served as the managing physician and medical director of the hospitalist group from 2007 to 2010. He began his new roles earlier this month and continues as a hospitalist at Evergreen on a part-time basis.

Hospitalist Brian Clonts, MD, was honored with the Medical Innovator Award at the inaugural Champions of Health Care awards ceremony by the Branson/Lakes Area Chamber of Commerce. Dr. Clonts has worked at Skaggs Regional Medical Center in Branson, Mo., since 2008. He is the medical director for the Skaggs Hospitalist Department and the Skaggs Stroke Program, serves on several committees, and serves as a physician in the U.S. Air Force Reserves.

Marc B. Westle, DO, FACP, FHM, has been appointed senior vice president of innovation at Mission Health in Asheville, N.C. A board-certified internist, Dr. Westle is charged with exploring “new options to improve delivery of healthcare” and moving Mission Health to an “outcome- accountable, risk-bearing capable organization” to serve western North Carolina, according to a release.

Hospitalist Rashid Ehsan, MD, has been named the 2011 Physician of the Year at Culpeper Regional Hospital in Culpeper, Va. Dr. Ehsan is chair of the Department of Medicine and a member of the hospital’s Medical Executive and CME committees. According to a release, he was honored for his professionalism, compassion, and popularity with patients, nurses, and support staff.

Marvin Trotter, MD, an ED doctor and hospitalist at Ukiah Valley (Calif.) Medical Center, has been named chief medical officer. Dr. Trotter will be a member of the executive team and will represent the medical staff in areas of vision, quality, and growth. He will continue to serve as a hospitalist for inpatient care. A graduate of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dr. Trotter is board-certified in internal medicine and has been a member of the Ukiah Valley team since 1986.

Hospitalist Martha Buckley, MD, was named the 2011 Gordon B. Snider, MD, Physician Teammate of the Year among her peers at Fairfield Medical Center (FMC) in Lancaster, Ohio. Dr. Buckley has been a hospitalist at FMC for two years as part of Colonnade Medical Group, also based in Lancaster.

Hospitalist Scott Stuart, MD, has assumed the role of medical director for the PCU and care management at Evergreen Hospital in Kirkland, Wash. Dr. Stuart has worked for Evergreen as an internal-medicine hospitalist since 2005, and previously served as the managing physician and medical director of the hospitalist group from 2007 to 2010. He began his new roles earlier this month and continues as a hospitalist at Evergreen on a part-time basis.

Hospitalist Brian Clonts, MD, was honored with the Medical Innovator Award at the inaugural Champions of Health Care awards ceremony by the Branson/Lakes Area Chamber of Commerce. Dr. Clonts has worked at Skaggs Regional Medical Center in Branson, Mo., since 2008. He is the medical director for the Skaggs Hospitalist Department and the Skaggs Stroke Program, serves on several committees, and serves as a physician in the U.S. Air Force Reserves.

Marc B. Westle, DO, FACP, FHM, has been appointed senior vice president of innovation at Mission Health in Asheville, N.C. A board-certified internist, Dr. Westle is charged with exploring “new options to improve delivery of healthcare” and moving Mission Health to an “outcome- accountable, risk-bearing capable organization” to serve western North Carolina, according to a release.

Hospitalist Rashid Ehsan, MD, has been named the 2011 Physician of the Year at Culpeper Regional Hospital in Culpeper, Va. Dr. Ehsan is chair of the Department of Medicine and a member of the hospital’s Medical Executive and CME committees. According to a release, he was honored for his professionalism, compassion, and popularity with patients, nurses, and support staff.

Marvin Trotter, MD, an ED doctor and hospitalist at Ukiah Valley (Calif.) Medical Center, has been named chief medical officer. Dr. Trotter will be a member of the executive team and will represent the medical staff in areas of vision, quality, and growth. He will continue to serve as a hospitalist for inpatient care. A graduate of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dr. Trotter is board-certified in internal medicine and has been a member of the Ukiah Valley team since 1986.

Hospitalist Martha Buckley, MD, was named the 2011 Gordon B. Snider, MD, Physician Teammate of the Year among her peers at Fairfield Medical Center (FMC) in Lancaster, Ohio. Dr. Buckley has been a hospitalist at FMC for two years as part of Colonnade Medical Group, also based in Lancaster.

Hospitalist Scott Stuart, MD, has assumed the role of medical director for the PCU and care management at Evergreen Hospital in Kirkland, Wash. Dr. Stuart has worked for Evergreen as an internal-medicine hospitalist since 2005, and previously served as the managing physician and medical director of the hospitalist group from 2007 to 2010. He began his new roles earlier this month and continues as a hospitalist at Evergreen on a part-time basis.

Hospitalist Brian Clonts, MD, was honored with the Medical Innovator Award at the inaugural Champions of Health Care awards ceremony by the Branson/Lakes Area Chamber of Commerce. Dr. Clonts has worked at Skaggs Regional Medical Center in Branson, Mo., since 2008. He is the medical director for the Skaggs Hospitalist Department and the Skaggs Stroke Program, serves on several committees, and serves as a physician in the U.S. Air Force Reserves.

Marc B. Westle, DO, FACP, FHM, has been appointed senior vice president of innovation at Mission Health in Asheville, N.C. A board-certified internist, Dr. Westle is charged with exploring “new options to improve delivery of healthcare” and moving Mission Health to an “outcome- accountable, risk-bearing capable organization” to serve western North Carolina, according to a release.

Hospitalist Rashid Ehsan, MD, has been named the 2011 Physician of the Year at Culpeper Regional Hospital in Culpeper, Va. Dr. Ehsan is chair of the Department of Medicine and a member of the hospital’s Medical Executive and CME committees. According to a release, he was honored for his professionalism, compassion, and popularity with patients, nurses, and support staff.

Marvin Trotter, MD, an ED doctor and hospitalist at Ukiah Valley (Calif.) Medical Center, has been named chief medical officer. Dr. Trotter will be a member of the executive team and will represent the medical staff in areas of vision, quality, and growth. He will continue to serve as a hospitalist for inpatient care. A graduate of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, Dr. Trotter is board-certified in internal medicine and has been a member of the Ukiah Valley team since 1986.

SHM's Leadership Academy: Everything They Don't Teach in Medical School

Hospital medicine groups continue to grow and thrive across the country. And as they do, HM groups need experienced leaders to drive them toward continued success.

After all, the skills needed to lead hospitalist groups rarely are taught in medical school. And before employers—or potential employers—elevate hospitalists to senior positions, they need to be assured that their up-and-coming leaders can meet the challenge.

SHM’s specialty-leading Leadership Academy gives employers the confidence they want and new leaders the skill sets they need. The academy’s three courses comprise the only leadership-training program specifically designed for the challenges hospitalists face.

In the past, SHM has presented the Leadership Academy twice a year—once in the spring and once in fall. Now, SHM offers Leadership Academy once a year in the fall.

This year, hospitalists attending the Leadership Academy can take advantage of the majestic setting of the Hyatt Regency Scottsdale Resort and Spa at Gainey Ranch in Arizona, a 27-acre hotel-resort near the scenic McDowell Mountains.

The 2012 Leadership Academy will feature the entry-level course “Foundations of Leadership,” which helps hospitalists begin their leadership journey, and “Advanced Leadership: Strategies and Tools for Personal Leadership Excellence,” which enables hospitalists who have taken “Foundations of Leadership” to use their own personal leadership styles to drive culture change in their organizations.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Hospital medicine groups continue to grow and thrive across the country. And as they do, HM groups need experienced leaders to drive them toward continued success.

After all, the skills needed to lead hospitalist groups rarely are taught in medical school. And before employers—or potential employers—elevate hospitalists to senior positions, they need to be assured that their up-and-coming leaders can meet the challenge.

SHM’s specialty-leading Leadership Academy gives employers the confidence they want and new leaders the skill sets they need. The academy’s three courses comprise the only leadership-training program specifically designed for the challenges hospitalists face.

In the past, SHM has presented the Leadership Academy twice a year—once in the spring and once in fall. Now, SHM offers Leadership Academy once a year in the fall.

This year, hospitalists attending the Leadership Academy can take advantage of the majestic setting of the Hyatt Regency Scottsdale Resort and Spa at Gainey Ranch in Arizona, a 27-acre hotel-resort near the scenic McDowell Mountains.

The 2012 Leadership Academy will feature the entry-level course “Foundations of Leadership,” which helps hospitalists begin their leadership journey, and “Advanced Leadership: Strategies and Tools for Personal Leadership Excellence,” which enables hospitalists who have taken “Foundations of Leadership” to use their own personal leadership styles to drive culture change in their organizations.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Hospital medicine groups continue to grow and thrive across the country. And as they do, HM groups need experienced leaders to drive them toward continued success.

After all, the skills needed to lead hospitalist groups rarely are taught in medical school. And before employers—or potential employers—elevate hospitalists to senior positions, they need to be assured that their up-and-coming leaders can meet the challenge.

SHM’s specialty-leading Leadership Academy gives employers the confidence they want and new leaders the skill sets they need. The academy’s three courses comprise the only leadership-training program specifically designed for the challenges hospitalists face.

In the past, SHM has presented the Leadership Academy twice a year—once in the spring and once in fall. Now, SHM offers Leadership Academy once a year in the fall.

This year, hospitalists attending the Leadership Academy can take advantage of the majestic setting of the Hyatt Regency Scottsdale Resort and Spa at Gainey Ranch in Arizona, a 27-acre hotel-resort near the scenic McDowell Mountains.

The 2012 Leadership Academy will feature the entry-level course “Foundations of Leadership,” which helps hospitalists begin their leadership journey, and “Advanced Leadership: Strategies and Tools for Personal Leadership Excellence,” which enables hospitalists who have taken “Foundations of Leadership” to use their own personal leadership styles to drive culture change in their organizations.

Brendon Shank is SHM’s associate vice president of communications.

Welcome, New Residents

Every summer, a crop of fresh-faced residents greets the medical world. Freed from the travails of medical school, these new physicians embark on a journey of learning by doing, experiencing firsthand the successes and pitfalls of our medical system. Undoubtedly, the vast majority of residents enter the profession with a desire to do good, to heal.

What might not be of immediate concern to the newly minted, patient-focused doctor, however, is the need to heal the medical system.

For residents, policy might seem slightly tangential to the practice of medicine. Indeed, it is possible to practice medicine without becoming involved in policymaking; however, changes in policies and regulations affect the practice of medicine every day.

Whether at the organizational, local, or national level, policy is a vital consideration for practicing physicians. As a new resident, policy helps shape your day-to-day life, from how you interact with patients to the number of hours you are working.

In New York, for example, the 1989 Libby Zion law restricts the number of hours a resident may work to 80 hours per week, a limit formally endorsed in 2003 by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for all accredited residency programs nationwide. These standards, which safeguard against the negative effects of sleep deprivation and chronic sleep loss, encourage better physical and mental care for residents and, ideally, promote better patient care. On the other hand, this rule changes the structure of residency programs and increases the number of patient handoffs to conform to hour restrictions. The challenge inherent in policy work is weighing competing interests and positions to find balance, or to justify imbalance.

When you sit down at a computer to input information about a patient, you will be using an electronic health record (EHR). This program is governed by regulations for health information technology (HIT). In fact, SHM commented on a recent proposed rule for the Stage 2 EHR Meaningful Use incentive program and whether hospitalists qualify for a hospital-based provider exemption from the program. By providing feedback to federal agencies, SHM actively influences the development of regulations, changing the impact of policies for hospitalists nationwide.

Your paycheck, too, is directly influenced by health policy, with much of the funds for residency programs coming from the federal Department of Health and Human Services and the rest coming from hospital sources. Recently, SHM supported U.S. Reps. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.) and Joe Heck (R-Nev.) in their introduction of H.R. 5707, the Medicare Physician Payment Innovation Act, which would repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) that threatens deep cuts to Medicare reimbursements originally intended to control spending. SHM actively advocates for rewarding high-value not simply high quantities of care, reflecting the orientation of hospitalists’ desire to improve the healthcare system.

Try as you might to avoid it, policy is all around you.

Even if such macro-level policy issues as value-based purchasing, payment bundling, or quality reporting initiatives seem beyond your scope of influence, it is important to stay involved and informed. SHM provides a conduit for hospitalists to become involved on large-scale policy issues. Ultimately, the strength of our organizational policy positions and influence grows with increased physician engagement.

More robust participation and more voices represented at the discussion increase the likelihood that meaningful and productive changes will occur.

As the next generation of hospitalists, today’s residents will be agents of change in their hospitals, improving patient care and advancing quality initiatives. By sharing these experiences, hospitalists can expand the policy conversation to reflect their work on the front lines—and help shape the reality for residents to come.

Every summer, a crop of fresh-faced residents greets the medical world. Freed from the travails of medical school, these new physicians embark on a journey of learning by doing, experiencing firsthand the successes and pitfalls of our medical system. Undoubtedly, the vast majority of residents enter the profession with a desire to do good, to heal.

What might not be of immediate concern to the newly minted, patient-focused doctor, however, is the need to heal the medical system.

For residents, policy might seem slightly tangential to the practice of medicine. Indeed, it is possible to practice medicine without becoming involved in policymaking; however, changes in policies and regulations affect the practice of medicine every day.

Whether at the organizational, local, or national level, policy is a vital consideration for practicing physicians. As a new resident, policy helps shape your day-to-day life, from how you interact with patients to the number of hours you are working.

In New York, for example, the 1989 Libby Zion law restricts the number of hours a resident may work to 80 hours per week, a limit formally endorsed in 2003 by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for all accredited residency programs nationwide. These standards, which safeguard against the negative effects of sleep deprivation and chronic sleep loss, encourage better physical and mental care for residents and, ideally, promote better patient care. On the other hand, this rule changes the structure of residency programs and increases the number of patient handoffs to conform to hour restrictions. The challenge inherent in policy work is weighing competing interests and positions to find balance, or to justify imbalance.

When you sit down at a computer to input information about a patient, you will be using an electronic health record (EHR). This program is governed by regulations for health information technology (HIT). In fact, SHM commented on a recent proposed rule for the Stage 2 EHR Meaningful Use incentive program and whether hospitalists qualify for a hospital-based provider exemption from the program. By providing feedback to federal agencies, SHM actively influences the development of regulations, changing the impact of policies for hospitalists nationwide.

Your paycheck, too, is directly influenced by health policy, with much of the funds for residency programs coming from the federal Department of Health and Human Services and the rest coming from hospital sources. Recently, SHM supported U.S. Reps. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.) and Joe Heck (R-Nev.) in their introduction of H.R. 5707, the Medicare Physician Payment Innovation Act, which would repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) that threatens deep cuts to Medicare reimbursements originally intended to control spending. SHM actively advocates for rewarding high-value not simply high quantities of care, reflecting the orientation of hospitalists’ desire to improve the healthcare system.

Try as you might to avoid it, policy is all around you.

Even if such macro-level policy issues as value-based purchasing, payment bundling, or quality reporting initiatives seem beyond your scope of influence, it is important to stay involved and informed. SHM provides a conduit for hospitalists to become involved on large-scale policy issues. Ultimately, the strength of our organizational policy positions and influence grows with increased physician engagement.

More robust participation and more voices represented at the discussion increase the likelihood that meaningful and productive changes will occur.

As the next generation of hospitalists, today’s residents will be agents of change in their hospitals, improving patient care and advancing quality initiatives. By sharing these experiences, hospitalists can expand the policy conversation to reflect their work on the front lines—and help shape the reality for residents to come.

Every summer, a crop of fresh-faced residents greets the medical world. Freed from the travails of medical school, these new physicians embark on a journey of learning by doing, experiencing firsthand the successes and pitfalls of our medical system. Undoubtedly, the vast majority of residents enter the profession with a desire to do good, to heal.

What might not be of immediate concern to the newly minted, patient-focused doctor, however, is the need to heal the medical system.

For residents, policy might seem slightly tangential to the practice of medicine. Indeed, it is possible to practice medicine without becoming involved in policymaking; however, changes in policies and regulations affect the practice of medicine every day.

Whether at the organizational, local, or national level, policy is a vital consideration for practicing physicians. As a new resident, policy helps shape your day-to-day life, from how you interact with patients to the number of hours you are working.

In New York, for example, the 1989 Libby Zion law restricts the number of hours a resident may work to 80 hours per week, a limit formally endorsed in 2003 by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for all accredited residency programs nationwide. These standards, which safeguard against the negative effects of sleep deprivation and chronic sleep loss, encourage better physical and mental care for residents and, ideally, promote better patient care. On the other hand, this rule changes the structure of residency programs and increases the number of patient handoffs to conform to hour restrictions. The challenge inherent in policy work is weighing competing interests and positions to find balance, or to justify imbalance.

When you sit down at a computer to input information about a patient, you will be using an electronic health record (EHR). This program is governed by regulations for health information technology (HIT). In fact, SHM commented on a recent proposed rule for the Stage 2 EHR Meaningful Use incentive program and whether hospitalists qualify for a hospital-based provider exemption from the program. By providing feedback to federal agencies, SHM actively influences the development of regulations, changing the impact of policies for hospitalists nationwide.

Your paycheck, too, is directly influenced by health policy, with much of the funds for residency programs coming from the federal Department of Health and Human Services and the rest coming from hospital sources. Recently, SHM supported U.S. Reps. Allyson Schwartz (D-Pa.) and Joe Heck (R-Nev.) in their introduction of H.R. 5707, the Medicare Physician Payment Innovation Act, which would repeal the sustainable growth rate (SGR) that threatens deep cuts to Medicare reimbursements originally intended to control spending. SHM actively advocates for rewarding high-value not simply high quantities of care, reflecting the orientation of hospitalists’ desire to improve the healthcare system.

Try as you might to avoid it, policy is all around you.

Even if such macro-level policy issues as value-based purchasing, payment bundling, or quality reporting initiatives seem beyond your scope of influence, it is important to stay involved and informed. SHM provides a conduit for hospitalists to become involved on large-scale policy issues. Ultimately, the strength of our organizational policy positions and influence grows with increased physician engagement.

More robust participation and more voices represented at the discussion increase the likelihood that meaningful and productive changes will occur.

As the next generation of hospitalists, today’s residents will be agents of change in their hospitals, improving patient care and advancing quality initiatives. By sharing these experiences, hospitalists can expand the policy conversation to reflect their work on the front lines—and help shape the reality for residents to come.

Project BOOST: Application deadline is Sep. 1

Almost every hospitalist knows what it’s like to see a familiar face that of a patient back in the hospital. Hundreds of hospitals across the country are learning that readmissions not only are a drain on hospitals and hospitalists, but they’re also preventable.

Now, thanks to the next cohort of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), which starts in October, even more hospitals can participate in this nationally recognized program to help reduce readmissions.

Sept. 1 is the deadline for Project BOOST applications, but now is the time to begin assembling applications. The Project BOOST application requires letters of support from hospital leadership and other elements that make last-minute applications difficult, if not impossible.

Project BOOST is a mentored-implementation, quality-improvement (QI) project. Here is what the program offers:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best-available evidence;

- Step-by-step instructions and project management tools, such as the Teachback Training Curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign workflow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention;

- Longitudinal technical assistance that provides face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a “train the trainer” DVD and a curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the Teachback process, and webinars targeting the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses, and others;

- The ability for sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST listserv, BOOST community site, and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars; and

- The BOOST Data Center, an online resource center that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generate reports.

Almost every hospitalist knows what it’s like to see a familiar face that of a patient back in the hospital. Hundreds of hospitals across the country are learning that readmissions not only are a drain on hospitals and hospitalists, but they’re also preventable.

Now, thanks to the next cohort of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), which starts in October, even more hospitals can participate in this nationally recognized program to help reduce readmissions.

Sept. 1 is the deadline for Project BOOST applications, but now is the time to begin assembling applications. The Project BOOST application requires letters of support from hospital leadership and other elements that make last-minute applications difficult, if not impossible.

Project BOOST is a mentored-implementation, quality-improvement (QI) project. Here is what the program offers:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best-available evidence;

- Step-by-step instructions and project management tools, such as the Teachback Training Curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign workflow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention;

- Longitudinal technical assistance that provides face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a “train the trainer” DVD and a curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the Teachback process, and webinars targeting the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses, and others;

- The ability for sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST listserv, BOOST community site, and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars; and

- The BOOST Data Center, an online resource center that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generate reports.

Almost every hospitalist knows what it’s like to see a familiar face that of a patient back in the hospital. Hundreds of hospitals across the country are learning that readmissions not only are a drain on hospitals and hospitalists, but they’re also preventable.

Now, thanks to the next cohort of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), which starts in October, even more hospitals can participate in this nationally recognized program to help reduce readmissions.

Sept. 1 is the deadline for Project BOOST applications, but now is the time to begin assembling applications. The Project BOOST application requires letters of support from hospital leadership and other elements that make last-minute applications difficult, if not impossible.

Project BOOST is a mentored-implementation, quality-improvement (QI) project. Here is what the program offers:

- A comprehensive intervention developed by a panel of nationally recognized experts based on the best-available evidence;

- Step-by-step instructions and project management tools, such as the Teachback Training Curriculum, to help interdisciplinary teams redesign workflow and plan, implement, and evaluate the intervention;

- Longitudinal technical assistance that provides face-to-face training and a year of expert mentoring and coaching to implement BOOST interventions that build a culture that supports safe and complete transitions. The mentoring program provides a “train the trainer” DVD and a curriculum for nurses and case managers on using the Teachback process, and webinars targeting the educational needs of other team members, including administrators, data analysts, physicians, nurses, and others;

- The ability for sites to communicate with and learn from each other via the BOOST listserv, BOOST community site, and quarterly all-site teleconferences and webinars; and

- The BOOST Data Center, an online resource center that allows sites to store and benchmark data against control units and other sites and generate reports.

Ready for Recognition?

For hospitalists ready to take the national stage at HM13 next spring in Washington, D.C., it's not too early to be thinking about submissions for SHM's Annual Awards of Excellence and SHM's Research, Innovation, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition. In fact, many winners have gone on to become SHM committee chairs, board members, and board presidents.

SHM will begin accepting submissions for both the Awards of Excellence and the RIV poster contest this month. Submissions will be accepted through October.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org.

For hospitalists ready to take the national stage at HM13 next spring in Washington, D.C., it's not too early to be thinking about submissions for SHM's Annual Awards of Excellence and SHM's Research, Innovation, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition. In fact, many winners have gone on to become SHM committee chairs, board members, and board presidents.

SHM will begin accepting submissions for both the Awards of Excellence and the RIV poster contest this month. Submissions will be accepted through October.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org.

For hospitalists ready to take the national stage at HM13 next spring in Washington, D.C., it's not too early to be thinking about submissions for SHM's Annual Awards of Excellence and SHM's Research, Innovation, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) poster competition. In fact, many winners have gone on to become SHM committee chairs, board members, and board presidents.

SHM will begin accepting submissions for both the Awards of Excellence and the RIV poster contest this month. Submissions will be accepted through October.

For more information, visit www.hospitalmedicine.org.

Guidelines for Pneumonia Call for Decreased Use of Broad-Spectrum Antibiotics

Clinical question: What is the impact of a clinical practice guideline for hospitalized children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) on antibiotic selection?

Background: CAP is one of the most common reasons for hospitalizations in children. Broad-spectrum antibiotics frequently are prescribed for presumed bacterial pneumonia in children. Recent guidelines for CAP in children have emphasized that ampicillin is an appropriate empiric inpatient treatment option.

Study design: Retrospective review.

Setting: Tertiary referral children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Patients older than two months old with acute, uncomplicated CAP and without significant secondary illness were identified in the 12-month periods preceding and following the implementation of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) that recommended empiric treatment with ampicillin upon admission, and amoxicillin upon discharge.

A total of 1,033 patients were identified, 530 pre-CPG and 503 post-CPG, and the groups were similar. After the CPG, there was a significant increase in empiric ampicillin use (13% to 63%) and concomitant decrease in ceftriaxone use (72% to 21%). Rates of outpatient narrow-spectrum antibiotic prescribing increased as well, and the rate of treatment failure was similar between the groups.

Complex regression analysis was used to analyze the impact of a concomitant antibiotic stewardship program (ASP), implemented three months prior to the initiation of the CPG and demonstrating a separate and additive effect of both initiatives. Thus, changes in antibiotic prescribing were multifactorial over this time period.

The outcomes remain impressive in the context of two increasingly popular QI efforts—CPGs and ASPs. This study represents a meaningful contribution toward demonstration of outcomes-based quality improvement (QI).

Bottom line: In the context of a CPG, antibiotic spectrum may be safely narrowed in pediatric CAP.

Citation: Newman RE, Hedican EB, Herigon JC, Williams DD, Williams AR, Newland JG. Impact of a guideline on management of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e597-604.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the impact of a clinical practice guideline for hospitalized children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) on antibiotic selection?

Background: CAP is one of the most common reasons for hospitalizations in children. Broad-spectrum antibiotics frequently are prescribed for presumed bacterial pneumonia in children. Recent guidelines for CAP in children have emphasized that ampicillin is an appropriate empiric inpatient treatment option.

Study design: Retrospective review.

Setting: Tertiary referral children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Patients older than two months old with acute, uncomplicated CAP and without significant secondary illness were identified in the 12-month periods preceding and following the implementation of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) that recommended empiric treatment with ampicillin upon admission, and amoxicillin upon discharge.

A total of 1,033 patients were identified, 530 pre-CPG and 503 post-CPG, and the groups were similar. After the CPG, there was a significant increase in empiric ampicillin use (13% to 63%) and concomitant decrease in ceftriaxone use (72% to 21%). Rates of outpatient narrow-spectrum antibiotic prescribing increased as well, and the rate of treatment failure was similar between the groups.

Complex regression analysis was used to analyze the impact of a concomitant antibiotic stewardship program (ASP), implemented three months prior to the initiation of the CPG and demonstrating a separate and additive effect of both initiatives. Thus, changes in antibiotic prescribing were multifactorial over this time period.

The outcomes remain impressive in the context of two increasingly popular QI efforts—CPGs and ASPs. This study represents a meaningful contribution toward demonstration of outcomes-based quality improvement (QI).

Bottom line: In the context of a CPG, antibiotic spectrum may be safely narrowed in pediatric CAP.

Citation: Newman RE, Hedican EB, Herigon JC, Williams DD, Williams AR, Newland JG. Impact of a guideline on management of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e597-604.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What is the impact of a clinical practice guideline for hospitalized children with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) on antibiotic selection?

Background: CAP is one of the most common reasons for hospitalizations in children. Broad-spectrum antibiotics frequently are prescribed for presumed bacterial pneumonia in children. Recent guidelines for CAP in children have emphasized that ampicillin is an appropriate empiric inpatient treatment option.

Study design: Retrospective review.

Setting: Tertiary referral children’s hospital.

Synopsis: Patients older than two months old with acute, uncomplicated CAP and without significant secondary illness were identified in the 12-month periods preceding and following the implementation of a clinical practice guideline (CPG) that recommended empiric treatment with ampicillin upon admission, and amoxicillin upon discharge.

A total of 1,033 patients were identified, 530 pre-CPG and 503 post-CPG, and the groups were similar. After the CPG, there was a significant increase in empiric ampicillin use (13% to 63%) and concomitant decrease in ceftriaxone use (72% to 21%). Rates of outpatient narrow-spectrum antibiotic prescribing increased as well, and the rate of treatment failure was similar between the groups.

Complex regression analysis was used to analyze the impact of a concomitant antibiotic stewardship program (ASP), implemented three months prior to the initiation of the CPG and demonstrating a separate and additive effect of both initiatives. Thus, changes in antibiotic prescribing were multifactorial over this time period.

The outcomes remain impressive in the context of two increasingly popular QI efforts—CPGs and ASPs. This study represents a meaningful contribution toward demonstration of outcomes-based quality improvement (QI).

Bottom line: In the context of a CPG, antibiotic spectrum may be safely narrowed in pediatric CAP.

Citation: Newman RE, Hedican EB, Herigon JC, Williams DD, Williams AR, Newland JG. Impact of a guideline on management of children hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e597-604.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, FHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children’s Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Guidelines for Management of Atrial Fibrillation

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common condition, affecting more than 2 million Americans.1 Hospital admissions due to AF have increased 66% in the past two decades. Hospitalization accounts for 52% of the cost of AF management, and the mortality rate of patients with this arrhythmia is twice that of patients in sinus rhythm.1

AF management decisions include choices for rate control, rhythm control, and prevention of thromboembolism. The benefits of a rhythm-control versus a rate-control strategy continue to be evaluated, along with consideration regarding an appropriate heart-rate goal. The modifiable risk factor of stroke in atrial fibrillation also continues to be a target for intervention as atrial fibrillation accounts for one-sixth of all strokes.

Guideline Update

The American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA), in conjunction with the European Society of Cardiology, released practice guidelines on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation in 2006. The ACCF/AHA, writing with the Heart Rhythm Society, released focused updates in early 2011 to be incorporated into the previous guidelines, given new data from major clinical trials and the FDA approval of new medications with indications for AF treatment.2,3

The new recommendations address components of all three major management decisions for AF: rate control, rhythm control, and prevention of thromboembolism.

When managing AF with a rate-control strategy, new guidelines no longer recommend the goal of a resting heart rate of <80 bpm or <115 bpm with activity. This is based on data from the RACE II trial that show no difference in meaningful outcomes with a more aggressive heart-rate goal. Achieving a resting heart rate of 110 bpm was deemed a reasonable approach, as long as the patient has stable ventricular function and acceptable symptoms.

The new drug dronedarone has been introduced in the algorithm for maintenance of sinus rhythm strategy, based on the DIONYSOS, ATHENA, and ANDROMEDA studies. The new algorithm excluded the use of dronedarone in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy, decompensated heart failure, or Class IV heart failure because it was shown to increase mortality in these groups. The guidelines also recommend that it should also be used with caution in patients with bradycardia, prolonged QT interval, increased creatinine, and in patients on agents that moderate CYP3A4 function.

The risks of interventions to decrease thromboembolism against bleeding risk continue to be evaluated in specified patient populations. Although dabigatran did not have FDA approval prior to submission of the 2011 updated guidelines, the 2011 “focused update” incorporated the results of the RE-LY trial. Publication of RE-LY resulted in a Class 1 recommendation for dabigatran as a useful alternative to warfarin in patients with nonvalvular AF without severe renal failure or advanced liver disease.3 However, there is no specific antidote, and dabigatran use is associated with higher rates of dyspepsia and a nonsignificant increase in rates of myocardial infarction. In patients for whom oral anticoagulation with warfarin is considered unsuitable, aspirin with clopidogrel may be considered, although warfarin therapy continues to be a superior therapy to this dual antiplatelet regimen based on the ACTIVE-W and ACTIVE-A studies.2

Established Guideline Analysis

Apart from the listed updates, the management of AF has not changed considerably in the past decade. Rate control continues to be the recommended strategy for older patients along with appropriate symptom control, particularly if they have hypertension or heart disease. Rhythm control is a frequent strategy in AF management, but several studies have not found any difference in quality of life, development or progression of heart failure, or stroke rates in patients for whom a rhythm-control strategy was chosen.

Additionally, these patients still require anticoagulation, and the side effects of anti-arrhythmic drugs might offset the benefits of sinus rhythm. Therefore, rate control is an appropriate strategy. The stroke rate and side-effect risks with anti-arrhythmics are considerably lower in younger patients or those with paroxysmal lone AF, and so a rhythm-control strategy in these groups is reasonable.

Stroke rate in AF increases with known high-risk factors (prior thromboembolism or rheumatic mitral stenosis) and moderate-risk factors (heart failure, hypertension, age over 75, and diabetes). Less validated risk factors include female gender, age 65-74, thyrotoxicosis, and the presence of coronary artery disease.

There are well-defined recommendations for how to anticoagulate specific subgroups that pose clinical challenges not directly addressed in studies, but the guidelines do assist with:

- Patients who have a stroke with a therapeutic INR: Rather than adding antiplatelet agents, INR goal can be raised to 3-3.5;

- Patients >75 years old who are at a high risk for bleeding: A target INR of 2.0 (target range 1.6-2.5) seems reasonable;1 and

- Patients with stable coronary artery disease and AF: Warfarin anticoagulation alone should provide satisfactory antithrombotic prophylaxis against cerebrovascular and coronary atheroembolic events.1

Decisions involving perioperative management of anticoagulation in patients with AF frequently arise. Per the guidelines, in patients with nonvalvular AF, anticoagulation can be stopped for up to one week without bridging for surgical or diagnostic procedures, but bridging should be considered in high-risk patients.

HM Takeaways

Hospitalists are likely to manage AF, whether alone or in conjunction with cardiology consultation. These new comprehensive guidelines deal with rate control, rhythm control, and prevention of thromboembolism. Hospitalists should take particular interest in the guidelines regarding lenient rate control, dronedarone for rhythm control, and dabigatran as a new alternative for anticoagulation in appropriate populations.

Drs. Farrell and Carbo are hospitalists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

References

- Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):e101-98.

- Wann LS, Curtis AB, January CT, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (Updating the 2006 Guideline): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8(1):157-76.

- Wann LS, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (update on dabigatran): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):1330-7.

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common condition, affecting more than 2 million Americans.1 Hospital admissions due to AF have increased 66% in the past two decades. Hospitalization accounts for 52% of the cost of AF management, and the mortality rate of patients with this arrhythmia is twice that of patients in sinus rhythm.1

AF management decisions include choices for rate control, rhythm control, and prevention of thromboembolism. The benefits of a rhythm-control versus a rate-control strategy continue to be evaluated, along with consideration regarding an appropriate heart-rate goal. The modifiable risk factor of stroke in atrial fibrillation also continues to be a target for intervention as atrial fibrillation accounts for one-sixth of all strokes.

Guideline Update