User login

Fever, dyspnea, and hepatitis in an Iraq veteran

A healthy 42-year-old US Army reservist returned home to Oregon in early April after a 12-month deployment in Iraq. About 6 weeks later, he developed a mild nonproductive cough; then, over the next 2 weeks, his symptoms progressed to myalgia, mild headache, fever, chills, drenching night sweats, and dyspnea on exertion.

About 2 weeks after the onset of his symptoms, he saw his primary care provider. The results of laboratory tests at that time were normal except for the following:

- Platelet count 110 × 109/L (reference range 150–400)

- Alkaline phosphatase 354 IU/L (40–100)

- Alanine aminotransferase 99 IU/L (5–36)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 220 IU/L (7–33).

Chest radiography was negative. He was told he had a viral infection and was sent home with no treatment.

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

- Influenza

- Ehrlichiosis

- Q fever

- Visceral leishmaniasis

- Malaria

Military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have involved large numbers of US Army Reserve and National Guard personnel: by 2007, more than 500,000 Reserve and National Guard personnel had served in these combat operations.1 Although these personnel are generally healthy and receive mandatory travel screenings, prophylactic drug treatment, and vaccinations, their close, long-term exposure to local populations and environments puts them at risk of many infections.2

Often, these veterans develop symptoms after returning home, and they seek medical care from providers outside the military medical system.3,4 Civilian health care providers are thus increasingly called on to recognize clinical syndromes associated with military operations.

FEVER IN RETURNED SOLDIERS

The presentation of this 42-year-old veteran has an extensive differential diagnosis. His symptoms arose more than a month after his return from Iraq, meaning he could have acquired an infection in Iraq, on his trip home, or even after arriving home.

A number of common viral and atypical respiratory pathogens could be involved, and although circulating influenza was not common at the time of year he happened to return (spring), it remains a possibility. However, the duration of his illness, with symptoms that gradually worsened over 12 days, argues against influenza and community-acquired respiratory and other viral illnesses.

Aronson et al5 have reviewed the infectious risks in deployed military personnel.5 Infectious syndromes that have manifested in military personnel a month or more after returning from Iraq or Afghanistan include malaria, Q fever, brucellosis, typhoid fever, and leishmaniasis.5

Malaria

Malaria should be considered in all travelers from endemic areas presenting with fever, especially if they have thrombocytopenia and anemia. Plasmodium vivax is present in Iraq, but transmission is rare and isolated. Defense Medical Surveillance System data show that most of the recent malaria cases in US military personnel were acquired in Afghanistan or Korea. Many of these cases were caused by P vivax and manifested weeks to months after exposure, and diagnosis was significantly delayed because the provider did not consider malaria in the differential diagnosis.4,6,7

Testing for malaria with serial thick and thin blood smears and the BinaxNOW (Iverness Medical, Princeton, NJ) rapid test, when available, should be done in all those who have served in malaria-endemic regions and who present with unexplained fever or consistent symptoms. Testing should be done even if prophylaxis was taken or the potential exposure was weeks to months before presentation.

Brucellosis

Brucellosis, a zoonosis typically acquired by ingesting unpasteurized dairy products, has a high prevalence in Eurasia. A nonspecific, multisystem illness with fever, hepatitis, and arthritis (classically sacroiliitis) is commonly described.

Brucellosis is less likely in our patient, given that he denied consumption of local dairy products while deployed. Also, he had prominent respiratory symptoms, which would not be typical of brucellosis.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease transmitted by sand flies, manifests in one of three ways, ie, as a cutaneous, a mucosal, or a visceral disease. Most infections recently reported in US military personnel have been cutaneous and were acquired in Iraq, where Leishmania major is the primary species.8 Visceral disease mimics lymphoma (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia), but only a handful of cases have been reported from Iraq and Afghanistan.9 The incubation period of visceral leishmaniasis is prolonged, and civilian providers should consider it even if the patient’s period of deployment was relatively long ago.

Q fever in military personnel

Q fever is caused by the intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii.

Q fever has been reported in more than 150 US military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.10–12 However, it may be more common than that. In one report, 10% of patients admitted to a combat support hospital in Iraq with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes potentially consistent with Q fever tested positive for it.13 And in several cases that manifested after deployment, Q fever was not considered initially by the health care provider.11,14 In response, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a health advisory in May 2010 alerting providers about Q fever in travelers returning from Iraq and the Netherlands.15

Q fever is a zoonosis associated with a wide range of animal reservoirs, primarily agricultural livestock such as cattle, goats, and sheep, but also a variety of other animals. There are multiple routes of transmission, including direct animal contact, ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products, and, most commonly, inhalation of aerosolized particles contaminated by animal droppings or secretions.16 Tick-borne and sexual transmission have been reported in rare instances.17,18 Importantly, in many cases from Iraq and from an outbreak in the Netherlands there was no obvious exposure.19

Q fever is a potential agent of bioterrorism; therefore, a large-scale, single-point outbreak should raise concern about a possible intentional release of the organism.20

Q fever has myriad presentations

About 60% of cases of Q fever infection are asymptomatic.21 In the United States, the estimated seroprevalence is 3%. Such a high seroprevalence, despite the relatively small number of reported cases, suggests that this infection is often subclinical.22

After 2 to 3 weeks of incubation, Q fever infection can produce a wide range of presentations involving almost any organ system (Table 1).16 An influenza-like illness with fever, pneumonia, and hepatitis is classic. Often, headache is severe enough to warrant lumbar puncture. Atypical and often severe presentations include gastrointestinal or neurologic manifestations.23–25 Rates of hospitalization and in-hospital death are low in acute disease: hospitalization occurs in roughly 2% of cases, and death in about 1% of those hospitalized.26,27

The presentation may mimic that of conditions caused by common community pathogens such as Legionella, Rickettsia, cytomegalovirus, Ebola virus, influenza, Mycoplasma, and human immunodeficiency virus (primary infection). Heightened suspicion is needed to prevent delays in diagnosis and treatment.

This patient’s symptoms and his recent deployment made Q fever very likely.

CASE CONTINUED

The patient continued to feel sick and reported having three to four loose bowel movements per day and mild abdominal pain. His cough and dyspnea persisted.

He had not had contact with anyone who was ill, denied being exposed to animals or insects, and had not consumed unpasteurized dairy products; he recalled having cleaned his military-issue uniforms and equipment 2 to 3 weeks before the symptoms began. He called a military physician to get advice on what else could be causing his symptoms. This physician recommended tests based on potential exposures in Iraq. Tests for brucellosis, visceral leishmaniasis, and Q fever were ordered.

Over the next several days, he began to feel better, and at 3 to 4 weeks after the onset of his symptoms, he felt that he had returned to normal. All tests were negative.

TESTING FOR ATYPICAL PATHOGENS

2. Which of the following would be the most readily available method to confirm the diagnosis?

- Culture

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing

- Histopathologic testing

- Serologic testing

Testing for atypical pathogens was reasonable in this patient. In addition to an evaluation for parasitic causes of persistent and chronic diarrhea, an evaluation for Q fever, brucellosis, and visceral leishmaniasis via serologic testing was warranted. A variety of tests exist for all of these infections, but serologic tests are the most readily available.

Leishmaniasis testing

Visceral leishmaniasis was traditionally diagnosed by visualizing organisms in splenic or bone marrow aspirates,28 but now serologic tests are available through commercial and public health laboratories such as the CDC. Immunochromatographic tests using recombinant k39 antigen are highly sensitive and specific and have been used in military cases.29,30

Brucellosis testing

Brucella can be cultured from blood or tissue samples. The laboratory must be alerted, as special media can be used to increase the yield and precautions must be taken to prevent laboratory-acquired infection. Serologic testing is the method most commonly used for diagnosis.31

Q fever testing

Q fever can be diagnosed with serologic testing during its acute and convalescent phases.

PCR testing of blood is useful for diagnosing acute disease and is positive before serologic conversion, thus allowing rapid diagnosis and treatment.32 The Joint Biological Agent Identification and Diagnostic System (JBAIDS) PCR platform was studied in a Combat Support Hospital in Iraq for making the rapid diagnosis of Q fever and has since been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for military use.33

Culture is beyond the scope of most clinical laboratories and requires specialized cell culture or egg yolk media. In tissue, usually liver tissue obtained in an effort to evaluate hepatitis, the histologic finding of “doughnut” granulomas, or fibrin-encased granulomas, can be suggestive of C burnetii but may be nonspecific and seen with other infections.23,34

Serologic testing with an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) remains the most common method of diagnosis. It is based on the detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM responses against phase I and phase II antigens of C burnetii. After initial infection, the organism displays phase I antigens and is highly infectious. When grown in culture, the organism undergoes phase shifting to a less infectious form with predominantly phase II antigens. Paradoxically, after initial infection in humans, antibody response against phase II antigens is seen first, whereas in chronic infection, a phase I antibody response dominates.26,35 Phase II antibodies appear around week 2, and 90% of samples from infected people are positive by week 3. A fourfold rise in titer between the acute-phase and convalescent-phase samples confirms the diagnosis.35

A number of serologic assays are available worldwide, but they have different methods and cutoff values, so questions have arisen about the equivalence of the results.14,36 Serologic cutoffs have been defined in Europe, where most cases of Q fever have been reported.37

CHRONIC Q FEVER

3. Which of the following would be the most likely chronic manifestation of Q fever?

- Pneumonia

- Hepatitis

- Endocarditis

- Chronic fatigue

- Osteomyelitis

Chronic syndromes can develop years to months after untreated or inadequately treated infection and can be serious. Chronic infection can also result after a clinically silent initial infection.26,38 Culture-negative endocarditis, which occurs in fewer than 1% of patients diagnosed with acute infection, is the most common chronic manifestation (Table 1). Patients with underlying valvular disease, malignancy, or immunosuppression are at greater risk.38–40

Challenges and controversies

The diagnosis of chronic Q fever remains challenging. Traditionally, elevated phase I IgG titers were considered highly predictive of chronic disease. A cutoff of 1:800 was set, based on retrospective data from chronic cases in Europe, but its generalizability to different assays and patient populations has been unclear. 14,36,37 Recent reviews and prospective analysis with serial serologic studies in the Dutch outbreak and other sources suggest the positive predictive value (PPV) of phase I IgG titers greater than 1:800 to be lower than previously estimated, largely due to widespread testing and resultant increased seroprevalence assessments. It has been suggested the cutoff be raised to 1:1,600, which still only carries a 59% positive predictive value.41,42

Chronic fatigue due to Q fever remains a controversial topic and has only been described in Europe, Asia, and Australia. A direct link has yet to be established.43 Additional research is needed, but small studies of prolonged antibiotic treatment have not shown benefit in these cases.44

CASE CONTINUED

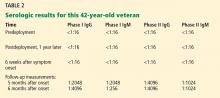

This patient did well. During a routine physical while enrolled at the Army War College in Carlisle, PA, 6 months after the original presentation, he mentioned his illness to the physician, who then repeated testing for Q fever; the test was positive (Table 2). Subsequently, serum samples from before and after his deployment were tested along with another convalescent-phase sample, and the results demonstrated Q fever seroconversion. He was well and had no physical complaints. He had no heart murmur, and a complete blood count and tests of liver enzymes and inflammatory markers were normal.

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION OF Q FEVER

4. Which of the following treatments would be appropriate, given his diagnosis of Q fever?

- Doxycycline (Vibramycin) 100 mg twice daily for 14 days

- Levofloxacin (Levaquin) 500 mg daily for 5 days

- Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 200 mg three times per day for 18 months

- No treatment

The treatment goals in Q fever are to hasten the resolution of symptoms and to prevent chronic disease. Generally, if there are no clinical findings or symptoms, treatment is not indicated. If the patient has symptoms, early treatment is preferred, but a response may be seen even when there is a delay in diagnosis.

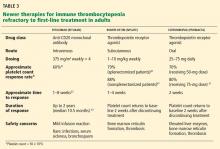

Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 14 days is the treatment of choice. In addition, quinolones have in vitro activity,45 and a recent study suggests moxifloxacin (Avelox) may be the preferred antibiotic for those who cannot tolerate doxycycline.46 In pregnant women and in children, macrolides and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) are preferred.47,48

Treatment of chronic Q fever, in particular endocarditis, warrants more intensive therapy. A retrospective review of treated cases of endocarditis suggested that monotherapy with doxycycline often failed, and combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine has been advocated based on in vivo and in vitro experience.49

PREVENTING LONG-TERM SEQUELAE OF CHRONIC Q FEVER

5. At this point, what is the next step in the management of this patient?

- No further follow-up is indicated

- Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE)

- Repeat Q fever serologic testing in 3 to 6 months

- Whole-blood PCR testing and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)

Long-term follow-up of patients with Q fever has been advocated to monitor for the development of chronic Q fever, but recent studies question the previously devised algorithms.50

The data the algorithms were based on suggested that preexisting valvular heart disease could be associated with up to a 39% risk of endocarditis, and a two-step approach was devised to prevent and identify early chronic infection.51,52 Patients with Q fever would undergo TTE at baseline, and if the findings were abnormal (including mild regurgitation), then 12 months of prophylactic treatment with hydroxychloroquine and doxycycline was recommended. If TTE was normal, serial serologic testing every 3 months was recommended. If the anti-phase I IgG titer was greater than 1:800 at any point, TEE and a whole-blood PCR assay were recommended to evaluate for endocarditis.51

These recommendations were based on data from the French National Reference Center and had not been prospectively evaluated. The 2007–2008 Dutch outbreak provided a large cohort of Q fever cases. After initial screening with TTE and serologic follow-up, 59% of patients were noted to have mild valvular abnormalities, and many had phase I IgG levels greater than 1:800 during follow-up despite being clinically free of disease. The Dutch subsequently stopped screening with TTE as part of routine follow-up and elected to follow patients clinically.

Similar findings have been noted from case follow-up in France and Taiwan, also supporting using serologic cutoffs alone in determining the need for evaluation (with TEE) or treatment of chronic disease.53,54 The usefulness of serologic testing every 3 months has also been questioned, and some have advocated extending the interval, especially since less emphasis is being placed on the results in favor of more practical clinical follow-up.39

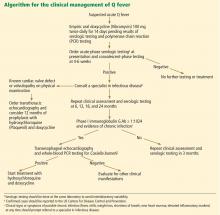

One such clinical approach at follow-up is presented in Figure 1. TTE should be reserved for patients with known valvular disease or a clear murmur. Those with underlying valvular disease and acute Q fever should be managed on an individual basis by a specialist in infectious disease, and antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered. Patients without underlying disease should have regular follow-up examinations and serologic testing every 6 months, and clinical symptoms should guide further testing (eg, with TEE and PCR testing) for chronic disease.

In this patient, phase I and II antibody titers were notably elevated (in TABLE 2, phase I titers > 1:800 and 1:1600 cutoffs). Such high titers have been common in military cases from Iraq and Afghanistan, and to date no cases of endocarditis have been diagnosed despite close follow-up. Most cases in military personnel are in relatively young patients who lack risk factors for endocarditis. Based on emerging data from large overseas outbreaks and the potential toxicity of intensive preemptive dual-antimicrobial therapy, an approach of close follow-up was taken.

PRIMARY PREVENTION OF Q FEVER

Prevention of Q fever remains a challenge, as the organism is highly persistent in the environment. An effective licensed vaccine exists in Australia under the brand name Q-Vax, but no approved vaccine is currently available in the United States.55

THE PATIENT’S COURSE

The patient returned for follow-up about 1 year after his first presentation. He noted some ongoing fatigue but attributed this to his course work, and he said he otherwise felt well. He exercises regularly, with no shortness of breath, fevers, chills, or weight loss. He continued to have elevated Q fever titers. Because he had no symptoms, no heart murmur, and normal inflammatory markers, he had no further workup and continued to be followed with serial serologic testing and examinations.

- Defense Science Board Task Force on Deployment of Members of the National Guard and Reserve in the Global War on Terrorism. Washington, DC. September 2007.

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73:713–719.

- Gleeson TD, Decker CF, Johnson MD, Hartzell JD, Mascola JR. Q fever in US military returning from Iraq. Am J Med 2007; 120:e11–e12.

- Hagan JE, Marcos LA, Steinberg TH. Fever in a soldier returned from Afghanistan. J Travel Med 2010; 17:351–352.

- Aronson NE, Sanders JW, Moran KA. In harm’s way: infections in deployed American military forces. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1045–1051.

- Klein TA, Pacha LA, Lee HC, et al. Plasmodium vivax malaria among U.S. forces Korea in the Republic of Korea, 1993–2007. Mil Med 2009; 174:412–418.

- Ciminera P, Brundage J. Malaria in U.S. military forces: a description of deployment exposures from 2003 through 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76:275–279.

- Lesho EP, Wortmann G, Neafie R, Aronson N. Nonhealing skin lesions in a sailor and a journalist returning from Iraq. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:93–96,

- Myles O, Wortmann GW, Cummings JF, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: clinical observations in 4 US army soldiers deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq, 2002–2004. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:1899–1901.

- Faix DJ, Harrison DJ, Riddle MS, et al. Outbreak of Q fever among US military in western Iraq, June–July 2005. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:e65–e68.

- Leung-Shea C, Danaher PJ. Q fever in members of the United States armed forces returning from Iraq. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:e77–e82.

- Anderson AD, Smoak B, Shuping E, Ockenhouse C, Petruccelli B. Q fever and the US military. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11:1320–1322.

- Anderson AD, Baker TR, Littrell AC, Mott RL, Niebuhr DW, Smoak BL. Seroepidemiologic survey for Coxiella burnetii among hospitalized US troops deployed to Iraq. Zoonoses Public Health 2011; 58:276–283.

- Ake JA, Massung RF, Whitman TJ, Gleeson TD. Difficulties in the diagnosis and management of a US servicemember presenting with possible chronic Q fever. J Infect 2010; 60:175–177.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Potential for Q fever infection among travelers returning from Iraq and the Netherlands http://www.bt.cdc.gov/HAN/han00313.asp. Accessed July 5, 2012.

- Parker NR, Barralet JH, Bell AM. Q fever. Lancet 2006; 367:679–688.

- Miceli MH, Veryser AK, Anderson AD, Hofinger D, Lee SA, Tancik C. A case of person-to-person transmission of Q fever from an active duty serviceman to his spouse. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2010; 10:539–541.

- Milazzo A, Hall R, Storm PA, Harris RJ, Winslow W, Marmion BP. Sexually transmitted Q fever. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:399–402.

- Hartzell JD, Peng SW, Wood-Morris RN, et al. Atypical Q fever in US soldiers. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13:1247–1249.

- Bossi P, Tegnell A, Baka A, et al; Task Force on Biological and Chemical Agent Threats, Public Health Directorate, European Commission, Luxembourg. Bichat guidelines for the clinical management of Q fever and bioterrorism-related Q fever. Euro Surveill 2004; 9:E19–E20.

- Roest HI, Tilburg JJ, van der Hoek W, et al. The Q fever epidemic in The Netherlands: history, onset, response and reflection. Epidemiol Infect 2011; 139:1–12.

- Anderson AD, Kruszon-Moran D, Loftis AD, et al. Seroprevalence of Q fever in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 81:691–694.

- Hatchette TF, Marrie TJ. Atypical manifestations of chronic Q fever. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:1347–1351.

- Bernit E, Pouget J, Janbon F, et al. Neurological involvement in acute Q fever: a report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:693–700.

- Kofteridis DP, Mazokopakis EE, Tselentis Y, Gikas A. Neurological complications of acute Q fever infection. Eur J Epidemiol 2004; 19:1051–1054.

- Raoult D, Marrie T, Mege J. Natural history and pathophysiology of Q fever. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5:219–226.

- Kampschreur LM, Wegdam-Blans MC, Thijsen SF, et al. Acute Q fever related in-hospital mortality in the Netherlands. Neth J Med 2010; 68:408–413.

- Srivastava P, Dayama A, Mehrotra S, Sundar S. Diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2011; 105:1–6.

- Chappuis F, Rijal S, Soto A, Menten J, Boelaert M. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of the direct agglutination test and rK39 dipstick for visceral leishmaniasis. BMJ 2006; 333:723.

- Hartzell JD, Aronson NE, Weina PJ, Howard RS, Yadava A, Wortmann GW. Positive rK39 serologic assay results in US servicemen with cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 79:843–846.

- Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, Tsianos E. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2325–2336.

- Schneeberger PM, Hermans MH, van Hannen EJ, Schellekens JJ, Leenders AC, Wever PC. Real-time PCR with serum samples is indispensable for early diagnosis of acute Q fever. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2010; 17:286–290.

- Hamilton LR, George DL, Scoville SL, Hospenthal DR, Griffith ME. PCR for rapid diagnosis of acute Q fever at a combat support hospital in Iraq. Mil Med 2011; 176:103–105.

- Bonilla MF, Kaul DR, Saint S, Isada CM, Brotman DJ. Clinical problem-solving. Ring around the diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1937–1942.

- Fournier PE, Marrie TJ, Raoult D. Diagnosis of Q fever. J Clin Microbiol 1998; 36:1823–1834.

- Healy B, van Woerden H, Raoult D, et al. Chronic Q fever: different serological results in three countries—results of a follow-up study 6 years after a point source outbreak. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:1013–1019.

- Dupont HT, Thirion X, Raoult D. Q fever serology: cutoff determination for microimmunofluorescence. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1994; 1:189–196.

- Karakousis PC, Trucksis M, Dumler JS. Chronic Q fever in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:2283–2287.

- van der Hoek W, Versteeg B, Meekelenkamp JC, et al. Follow-up of 686 patients with acute Q fever and detection of chronic infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:1431–1436.

- Fenollar F, Fournier PE, Carrieri MP, Habib G, Messana T, Raoult D. Risks factors and prevention of Q fever endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:312–316.

- Frankel D, Richet H, Renvoisé A, Raoult D. Q fever in France, 1985–2009. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:350–356.

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al; Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; American Heart Association; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 2005; 111:e394–e434.

- Wildman MJ, Smith EG, Groves J, Beattie JM, Caul EO, Ayres JG. Chronic fatigue following infection by Coxiella burnetii (Q fever): ten-year follow-up of the 1989 UK outbreak cohort. QJM 2002; 95:527–538.

- Iwakami E, Arashima Y, Kato K, et al. Treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome with antibiotics: pilot study assessing the involvement of Coxiella burnetii infection. Intern Med 2005; 44:1258–1263.

- Rolain JM, Maurin M, Raoult D. Bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities of moxifloxacin against Coxiella burnetii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001; 45:301–302.

- Dijkstra F, Riphagen-Dalhuisen J, Wijers N, et al. Antibiotic therapy for acute Q fever in The Netherlands in 2007 and 2008 and its relation to hospitalization. Epidemiol Infect 2011; 139:1332–1341.

- Raoult D. Use of macrolides for Q fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 47:446.

- Carcopino X, Raoult D, Bretelle F, Boubli L, Stein A. Managing Q fever during pregnancy: the benefits of long-term cotrimoxazole therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:548–555.

- Raoult D, Houpikian P, Tissot Dupont H, Riss JM, Arditi-Djiane J, Brouqui P. Treatment of Q fever endocarditis: comparison of 2 regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:167–173.

- Healy B, Llewelyn M, Westmoreland D, Lloyd G, Brown N. The value of follow-up after acute Q fever infection. J Infect 2006; 52:e109–e112.

- Landais C, Fenollar F, Thuny F, Raoult D. From acute Q fever to endocarditis: serological follow-up strategy. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:1337–1340.

- Hartzell JD, Wood-Morris RN, Martinez LJ, Trotta RF. Q fever: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83:574–579.

- Hung MN, Lin LJ, Hou MY, et al. Serologic assessment of the risk of developing chronic Q fever in cohorts of acutely infected individuals. J Infect 2011; 62:39–44.

- Sunder S, Gras G, Bastides F, De Gialluly C, Choutet P, Bernard L. Chronic Q fever: relevance of serology. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:749–750.

- Gefenaite G, Munster JM, van Houdt R, Hak E. Effectiveness of the Q fever vaccine: a meta-analysis. Vaccine 2011; 29:395–398.

A healthy 42-year-old US Army reservist returned home to Oregon in early April after a 12-month deployment in Iraq. About 6 weeks later, he developed a mild nonproductive cough; then, over the next 2 weeks, his symptoms progressed to myalgia, mild headache, fever, chills, drenching night sweats, and dyspnea on exertion.

About 2 weeks after the onset of his symptoms, he saw his primary care provider. The results of laboratory tests at that time were normal except for the following:

- Platelet count 110 × 109/L (reference range 150–400)

- Alkaline phosphatase 354 IU/L (40–100)

- Alanine aminotransferase 99 IU/L (5–36)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 220 IU/L (7–33).

Chest radiography was negative. He was told he had a viral infection and was sent home with no treatment.

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

- Influenza

- Ehrlichiosis

- Q fever

- Visceral leishmaniasis

- Malaria

Military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have involved large numbers of US Army Reserve and National Guard personnel: by 2007, more than 500,000 Reserve and National Guard personnel had served in these combat operations.1 Although these personnel are generally healthy and receive mandatory travel screenings, prophylactic drug treatment, and vaccinations, their close, long-term exposure to local populations and environments puts them at risk of many infections.2

Often, these veterans develop symptoms after returning home, and they seek medical care from providers outside the military medical system.3,4 Civilian health care providers are thus increasingly called on to recognize clinical syndromes associated with military operations.

FEVER IN RETURNED SOLDIERS

The presentation of this 42-year-old veteran has an extensive differential diagnosis. His symptoms arose more than a month after his return from Iraq, meaning he could have acquired an infection in Iraq, on his trip home, or even after arriving home.

A number of common viral and atypical respiratory pathogens could be involved, and although circulating influenza was not common at the time of year he happened to return (spring), it remains a possibility. However, the duration of his illness, with symptoms that gradually worsened over 12 days, argues against influenza and community-acquired respiratory and other viral illnesses.

Aronson et al5 have reviewed the infectious risks in deployed military personnel.5 Infectious syndromes that have manifested in military personnel a month or more after returning from Iraq or Afghanistan include malaria, Q fever, brucellosis, typhoid fever, and leishmaniasis.5

Malaria

Malaria should be considered in all travelers from endemic areas presenting with fever, especially if they have thrombocytopenia and anemia. Plasmodium vivax is present in Iraq, but transmission is rare and isolated. Defense Medical Surveillance System data show that most of the recent malaria cases in US military personnel were acquired in Afghanistan or Korea. Many of these cases were caused by P vivax and manifested weeks to months after exposure, and diagnosis was significantly delayed because the provider did not consider malaria in the differential diagnosis.4,6,7

Testing for malaria with serial thick and thin blood smears and the BinaxNOW (Iverness Medical, Princeton, NJ) rapid test, when available, should be done in all those who have served in malaria-endemic regions and who present with unexplained fever or consistent symptoms. Testing should be done even if prophylaxis was taken or the potential exposure was weeks to months before presentation.

Brucellosis

Brucellosis, a zoonosis typically acquired by ingesting unpasteurized dairy products, has a high prevalence in Eurasia. A nonspecific, multisystem illness with fever, hepatitis, and arthritis (classically sacroiliitis) is commonly described.

Brucellosis is less likely in our patient, given that he denied consumption of local dairy products while deployed. Also, he had prominent respiratory symptoms, which would not be typical of brucellosis.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease transmitted by sand flies, manifests in one of three ways, ie, as a cutaneous, a mucosal, or a visceral disease. Most infections recently reported in US military personnel have been cutaneous and were acquired in Iraq, where Leishmania major is the primary species.8 Visceral disease mimics lymphoma (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia), but only a handful of cases have been reported from Iraq and Afghanistan.9 The incubation period of visceral leishmaniasis is prolonged, and civilian providers should consider it even if the patient’s period of deployment was relatively long ago.

Q fever in military personnel

Q fever is caused by the intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii.

Q fever has been reported in more than 150 US military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.10–12 However, it may be more common than that. In one report, 10% of patients admitted to a combat support hospital in Iraq with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes potentially consistent with Q fever tested positive for it.13 And in several cases that manifested after deployment, Q fever was not considered initially by the health care provider.11,14 In response, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a health advisory in May 2010 alerting providers about Q fever in travelers returning from Iraq and the Netherlands.15

Q fever is a zoonosis associated with a wide range of animal reservoirs, primarily agricultural livestock such as cattle, goats, and sheep, but also a variety of other animals. There are multiple routes of transmission, including direct animal contact, ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products, and, most commonly, inhalation of aerosolized particles contaminated by animal droppings or secretions.16 Tick-borne and sexual transmission have been reported in rare instances.17,18 Importantly, in many cases from Iraq and from an outbreak in the Netherlands there was no obvious exposure.19

Q fever is a potential agent of bioterrorism; therefore, a large-scale, single-point outbreak should raise concern about a possible intentional release of the organism.20

Q fever has myriad presentations

About 60% of cases of Q fever infection are asymptomatic.21 In the United States, the estimated seroprevalence is 3%. Such a high seroprevalence, despite the relatively small number of reported cases, suggests that this infection is often subclinical.22

After 2 to 3 weeks of incubation, Q fever infection can produce a wide range of presentations involving almost any organ system (Table 1).16 An influenza-like illness with fever, pneumonia, and hepatitis is classic. Often, headache is severe enough to warrant lumbar puncture. Atypical and often severe presentations include gastrointestinal or neurologic manifestations.23–25 Rates of hospitalization and in-hospital death are low in acute disease: hospitalization occurs in roughly 2% of cases, and death in about 1% of those hospitalized.26,27

The presentation may mimic that of conditions caused by common community pathogens such as Legionella, Rickettsia, cytomegalovirus, Ebola virus, influenza, Mycoplasma, and human immunodeficiency virus (primary infection). Heightened suspicion is needed to prevent delays in diagnosis and treatment.

This patient’s symptoms and his recent deployment made Q fever very likely.

CASE CONTINUED

The patient continued to feel sick and reported having three to four loose bowel movements per day and mild abdominal pain. His cough and dyspnea persisted.

He had not had contact with anyone who was ill, denied being exposed to animals or insects, and had not consumed unpasteurized dairy products; he recalled having cleaned his military-issue uniforms and equipment 2 to 3 weeks before the symptoms began. He called a military physician to get advice on what else could be causing his symptoms. This physician recommended tests based on potential exposures in Iraq. Tests for brucellosis, visceral leishmaniasis, and Q fever were ordered.

Over the next several days, he began to feel better, and at 3 to 4 weeks after the onset of his symptoms, he felt that he had returned to normal. All tests were negative.

TESTING FOR ATYPICAL PATHOGENS

2. Which of the following would be the most readily available method to confirm the diagnosis?

- Culture

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing

- Histopathologic testing

- Serologic testing

Testing for atypical pathogens was reasonable in this patient. In addition to an evaluation for parasitic causes of persistent and chronic diarrhea, an evaluation for Q fever, brucellosis, and visceral leishmaniasis via serologic testing was warranted. A variety of tests exist for all of these infections, but serologic tests are the most readily available.

Leishmaniasis testing

Visceral leishmaniasis was traditionally diagnosed by visualizing organisms in splenic or bone marrow aspirates,28 but now serologic tests are available through commercial and public health laboratories such as the CDC. Immunochromatographic tests using recombinant k39 antigen are highly sensitive and specific and have been used in military cases.29,30

Brucellosis testing

Brucella can be cultured from blood or tissue samples. The laboratory must be alerted, as special media can be used to increase the yield and precautions must be taken to prevent laboratory-acquired infection. Serologic testing is the method most commonly used for diagnosis.31

Q fever testing

Q fever can be diagnosed with serologic testing during its acute and convalescent phases.

PCR testing of blood is useful for diagnosing acute disease and is positive before serologic conversion, thus allowing rapid diagnosis and treatment.32 The Joint Biological Agent Identification and Diagnostic System (JBAIDS) PCR platform was studied in a Combat Support Hospital in Iraq for making the rapid diagnosis of Q fever and has since been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for military use.33

Culture is beyond the scope of most clinical laboratories and requires specialized cell culture or egg yolk media. In tissue, usually liver tissue obtained in an effort to evaluate hepatitis, the histologic finding of “doughnut” granulomas, or fibrin-encased granulomas, can be suggestive of C burnetii but may be nonspecific and seen with other infections.23,34

Serologic testing with an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) remains the most common method of diagnosis. It is based on the detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM responses against phase I and phase II antigens of C burnetii. After initial infection, the organism displays phase I antigens and is highly infectious. When grown in culture, the organism undergoes phase shifting to a less infectious form with predominantly phase II antigens. Paradoxically, after initial infection in humans, antibody response against phase II antigens is seen first, whereas in chronic infection, a phase I antibody response dominates.26,35 Phase II antibodies appear around week 2, and 90% of samples from infected people are positive by week 3. A fourfold rise in titer between the acute-phase and convalescent-phase samples confirms the diagnosis.35

A number of serologic assays are available worldwide, but they have different methods and cutoff values, so questions have arisen about the equivalence of the results.14,36 Serologic cutoffs have been defined in Europe, where most cases of Q fever have been reported.37

CHRONIC Q FEVER

3. Which of the following would be the most likely chronic manifestation of Q fever?

- Pneumonia

- Hepatitis

- Endocarditis

- Chronic fatigue

- Osteomyelitis

Chronic syndromes can develop years to months after untreated or inadequately treated infection and can be serious. Chronic infection can also result after a clinically silent initial infection.26,38 Culture-negative endocarditis, which occurs in fewer than 1% of patients diagnosed with acute infection, is the most common chronic manifestation (Table 1). Patients with underlying valvular disease, malignancy, or immunosuppression are at greater risk.38–40

Challenges and controversies

The diagnosis of chronic Q fever remains challenging. Traditionally, elevated phase I IgG titers were considered highly predictive of chronic disease. A cutoff of 1:800 was set, based on retrospective data from chronic cases in Europe, but its generalizability to different assays and patient populations has been unclear. 14,36,37 Recent reviews and prospective analysis with serial serologic studies in the Dutch outbreak and other sources suggest the positive predictive value (PPV) of phase I IgG titers greater than 1:800 to be lower than previously estimated, largely due to widespread testing and resultant increased seroprevalence assessments. It has been suggested the cutoff be raised to 1:1,600, which still only carries a 59% positive predictive value.41,42

Chronic fatigue due to Q fever remains a controversial topic and has only been described in Europe, Asia, and Australia. A direct link has yet to be established.43 Additional research is needed, but small studies of prolonged antibiotic treatment have not shown benefit in these cases.44

CASE CONTINUED

This patient did well. During a routine physical while enrolled at the Army War College in Carlisle, PA, 6 months after the original presentation, he mentioned his illness to the physician, who then repeated testing for Q fever; the test was positive (Table 2). Subsequently, serum samples from before and after his deployment were tested along with another convalescent-phase sample, and the results demonstrated Q fever seroconversion. He was well and had no physical complaints. He had no heart murmur, and a complete blood count and tests of liver enzymes and inflammatory markers were normal.

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION OF Q FEVER

4. Which of the following treatments would be appropriate, given his diagnosis of Q fever?

- Doxycycline (Vibramycin) 100 mg twice daily for 14 days

- Levofloxacin (Levaquin) 500 mg daily for 5 days

- Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 200 mg three times per day for 18 months

- No treatment

The treatment goals in Q fever are to hasten the resolution of symptoms and to prevent chronic disease. Generally, if there are no clinical findings or symptoms, treatment is not indicated. If the patient has symptoms, early treatment is preferred, but a response may be seen even when there is a delay in diagnosis.

Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 14 days is the treatment of choice. In addition, quinolones have in vitro activity,45 and a recent study suggests moxifloxacin (Avelox) may be the preferred antibiotic for those who cannot tolerate doxycycline.46 In pregnant women and in children, macrolides and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) are preferred.47,48

Treatment of chronic Q fever, in particular endocarditis, warrants more intensive therapy. A retrospective review of treated cases of endocarditis suggested that monotherapy with doxycycline often failed, and combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine has been advocated based on in vivo and in vitro experience.49

PREVENTING LONG-TERM SEQUELAE OF CHRONIC Q FEVER

5. At this point, what is the next step in the management of this patient?

- No further follow-up is indicated

- Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE)

- Repeat Q fever serologic testing in 3 to 6 months

- Whole-blood PCR testing and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)

Long-term follow-up of patients with Q fever has been advocated to monitor for the development of chronic Q fever, but recent studies question the previously devised algorithms.50

The data the algorithms were based on suggested that preexisting valvular heart disease could be associated with up to a 39% risk of endocarditis, and a two-step approach was devised to prevent and identify early chronic infection.51,52 Patients with Q fever would undergo TTE at baseline, and if the findings were abnormal (including mild regurgitation), then 12 months of prophylactic treatment with hydroxychloroquine and doxycycline was recommended. If TTE was normal, serial serologic testing every 3 months was recommended. If the anti-phase I IgG titer was greater than 1:800 at any point, TEE and a whole-blood PCR assay were recommended to evaluate for endocarditis.51

These recommendations were based on data from the French National Reference Center and had not been prospectively evaluated. The 2007–2008 Dutch outbreak provided a large cohort of Q fever cases. After initial screening with TTE and serologic follow-up, 59% of patients were noted to have mild valvular abnormalities, and many had phase I IgG levels greater than 1:800 during follow-up despite being clinically free of disease. The Dutch subsequently stopped screening with TTE as part of routine follow-up and elected to follow patients clinically.

Similar findings have been noted from case follow-up in France and Taiwan, also supporting using serologic cutoffs alone in determining the need for evaluation (with TEE) or treatment of chronic disease.53,54 The usefulness of serologic testing every 3 months has also been questioned, and some have advocated extending the interval, especially since less emphasis is being placed on the results in favor of more practical clinical follow-up.39

One such clinical approach at follow-up is presented in Figure 1. TTE should be reserved for patients with known valvular disease or a clear murmur. Those with underlying valvular disease and acute Q fever should be managed on an individual basis by a specialist in infectious disease, and antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered. Patients without underlying disease should have regular follow-up examinations and serologic testing every 6 months, and clinical symptoms should guide further testing (eg, with TEE and PCR testing) for chronic disease.

In this patient, phase I and II antibody titers were notably elevated (in TABLE 2, phase I titers > 1:800 and 1:1600 cutoffs). Such high titers have been common in military cases from Iraq and Afghanistan, and to date no cases of endocarditis have been diagnosed despite close follow-up. Most cases in military personnel are in relatively young patients who lack risk factors for endocarditis. Based on emerging data from large overseas outbreaks and the potential toxicity of intensive preemptive dual-antimicrobial therapy, an approach of close follow-up was taken.

PRIMARY PREVENTION OF Q FEVER

Prevention of Q fever remains a challenge, as the organism is highly persistent in the environment. An effective licensed vaccine exists in Australia under the brand name Q-Vax, but no approved vaccine is currently available in the United States.55

THE PATIENT’S COURSE

The patient returned for follow-up about 1 year after his first presentation. He noted some ongoing fatigue but attributed this to his course work, and he said he otherwise felt well. He exercises regularly, with no shortness of breath, fevers, chills, or weight loss. He continued to have elevated Q fever titers. Because he had no symptoms, no heart murmur, and normal inflammatory markers, he had no further workup and continued to be followed with serial serologic testing and examinations.

A healthy 42-year-old US Army reservist returned home to Oregon in early April after a 12-month deployment in Iraq. About 6 weeks later, he developed a mild nonproductive cough; then, over the next 2 weeks, his symptoms progressed to myalgia, mild headache, fever, chills, drenching night sweats, and dyspnea on exertion.

About 2 weeks after the onset of his symptoms, he saw his primary care provider. The results of laboratory tests at that time were normal except for the following:

- Platelet count 110 × 109/L (reference range 150–400)

- Alkaline phosphatase 354 IU/L (40–100)

- Alanine aminotransferase 99 IU/L (5–36)

- Aspartate aminotransferase 220 IU/L (7–33).

Chest radiography was negative. He was told he had a viral infection and was sent home with no treatment.

1. Which of the following is the most likely diagnosis in this patient?

- Influenza

- Ehrlichiosis

- Q fever

- Visceral leishmaniasis

- Malaria

Military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have involved large numbers of US Army Reserve and National Guard personnel: by 2007, more than 500,000 Reserve and National Guard personnel had served in these combat operations.1 Although these personnel are generally healthy and receive mandatory travel screenings, prophylactic drug treatment, and vaccinations, their close, long-term exposure to local populations and environments puts them at risk of many infections.2

Often, these veterans develop symptoms after returning home, and they seek medical care from providers outside the military medical system.3,4 Civilian health care providers are thus increasingly called on to recognize clinical syndromes associated with military operations.

FEVER IN RETURNED SOLDIERS

The presentation of this 42-year-old veteran has an extensive differential diagnosis. His symptoms arose more than a month after his return from Iraq, meaning he could have acquired an infection in Iraq, on his trip home, or even after arriving home.

A number of common viral and atypical respiratory pathogens could be involved, and although circulating influenza was not common at the time of year he happened to return (spring), it remains a possibility. However, the duration of his illness, with symptoms that gradually worsened over 12 days, argues against influenza and community-acquired respiratory and other viral illnesses.

Aronson et al5 have reviewed the infectious risks in deployed military personnel.5 Infectious syndromes that have manifested in military personnel a month or more after returning from Iraq or Afghanistan include malaria, Q fever, brucellosis, typhoid fever, and leishmaniasis.5

Malaria

Malaria should be considered in all travelers from endemic areas presenting with fever, especially if they have thrombocytopenia and anemia. Plasmodium vivax is present in Iraq, but transmission is rare and isolated. Defense Medical Surveillance System data show that most of the recent malaria cases in US military personnel were acquired in Afghanistan or Korea. Many of these cases were caused by P vivax and manifested weeks to months after exposure, and diagnosis was significantly delayed because the provider did not consider malaria in the differential diagnosis.4,6,7

Testing for malaria with serial thick and thin blood smears and the BinaxNOW (Iverness Medical, Princeton, NJ) rapid test, when available, should be done in all those who have served in malaria-endemic regions and who present with unexplained fever or consistent symptoms. Testing should be done even if prophylaxis was taken or the potential exposure was weeks to months before presentation.

Brucellosis

Brucellosis, a zoonosis typically acquired by ingesting unpasteurized dairy products, has a high prevalence in Eurasia. A nonspecific, multisystem illness with fever, hepatitis, and arthritis (classically sacroiliitis) is commonly described.

Brucellosis is less likely in our patient, given that he denied consumption of local dairy products while deployed. Also, he had prominent respiratory symptoms, which would not be typical of brucellosis.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis, a parasitic disease transmitted by sand flies, manifests in one of three ways, ie, as a cutaneous, a mucosal, or a visceral disease. Most infections recently reported in US military personnel have been cutaneous and were acquired in Iraq, where Leishmania major is the primary species.8 Visceral disease mimics lymphoma (fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and cytopenia), but only a handful of cases have been reported from Iraq and Afghanistan.9 The incubation period of visceral leishmaniasis is prolonged, and civilian providers should consider it even if the patient’s period of deployment was relatively long ago.

Q fever in military personnel

Q fever is caused by the intracellular bacterium Coxiella burnetii.

Q fever has been reported in more than 150 US military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan.10–12 However, it may be more common than that. In one report, 10% of patients admitted to a combat support hospital in Iraq with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes potentially consistent with Q fever tested positive for it.13 And in several cases that manifested after deployment, Q fever was not considered initially by the health care provider.11,14 In response, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released a health advisory in May 2010 alerting providers about Q fever in travelers returning from Iraq and the Netherlands.15

Q fever is a zoonosis associated with a wide range of animal reservoirs, primarily agricultural livestock such as cattle, goats, and sheep, but also a variety of other animals. There are multiple routes of transmission, including direct animal contact, ingestion of unpasteurized dairy products, and, most commonly, inhalation of aerosolized particles contaminated by animal droppings or secretions.16 Tick-borne and sexual transmission have been reported in rare instances.17,18 Importantly, in many cases from Iraq and from an outbreak in the Netherlands there was no obvious exposure.19

Q fever is a potential agent of bioterrorism; therefore, a large-scale, single-point outbreak should raise concern about a possible intentional release of the organism.20

Q fever has myriad presentations

About 60% of cases of Q fever infection are asymptomatic.21 In the United States, the estimated seroprevalence is 3%. Such a high seroprevalence, despite the relatively small number of reported cases, suggests that this infection is often subclinical.22

After 2 to 3 weeks of incubation, Q fever infection can produce a wide range of presentations involving almost any organ system (Table 1).16 An influenza-like illness with fever, pneumonia, and hepatitis is classic. Often, headache is severe enough to warrant lumbar puncture. Atypical and often severe presentations include gastrointestinal or neurologic manifestations.23–25 Rates of hospitalization and in-hospital death are low in acute disease: hospitalization occurs in roughly 2% of cases, and death in about 1% of those hospitalized.26,27

The presentation may mimic that of conditions caused by common community pathogens such as Legionella, Rickettsia, cytomegalovirus, Ebola virus, influenza, Mycoplasma, and human immunodeficiency virus (primary infection). Heightened suspicion is needed to prevent delays in diagnosis and treatment.

This patient’s symptoms and his recent deployment made Q fever very likely.

CASE CONTINUED

The patient continued to feel sick and reported having three to four loose bowel movements per day and mild abdominal pain. His cough and dyspnea persisted.

He had not had contact with anyone who was ill, denied being exposed to animals or insects, and had not consumed unpasteurized dairy products; he recalled having cleaned his military-issue uniforms and equipment 2 to 3 weeks before the symptoms began. He called a military physician to get advice on what else could be causing his symptoms. This physician recommended tests based on potential exposures in Iraq. Tests for brucellosis, visceral leishmaniasis, and Q fever were ordered.

Over the next several days, he began to feel better, and at 3 to 4 weeks after the onset of his symptoms, he felt that he had returned to normal. All tests were negative.

TESTING FOR ATYPICAL PATHOGENS

2. Which of the following would be the most readily available method to confirm the diagnosis?

- Culture

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing

- Histopathologic testing

- Serologic testing

Testing for atypical pathogens was reasonable in this patient. In addition to an evaluation for parasitic causes of persistent and chronic diarrhea, an evaluation for Q fever, brucellosis, and visceral leishmaniasis via serologic testing was warranted. A variety of tests exist for all of these infections, but serologic tests are the most readily available.

Leishmaniasis testing

Visceral leishmaniasis was traditionally diagnosed by visualizing organisms in splenic or bone marrow aspirates,28 but now serologic tests are available through commercial and public health laboratories such as the CDC. Immunochromatographic tests using recombinant k39 antigen are highly sensitive and specific and have been used in military cases.29,30

Brucellosis testing

Brucella can be cultured from blood or tissue samples. The laboratory must be alerted, as special media can be used to increase the yield and precautions must be taken to prevent laboratory-acquired infection. Serologic testing is the method most commonly used for diagnosis.31

Q fever testing

Q fever can be diagnosed with serologic testing during its acute and convalescent phases.

PCR testing of blood is useful for diagnosing acute disease and is positive before serologic conversion, thus allowing rapid diagnosis and treatment.32 The Joint Biological Agent Identification and Diagnostic System (JBAIDS) PCR platform was studied in a Combat Support Hospital in Iraq for making the rapid diagnosis of Q fever and has since been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for military use.33

Culture is beyond the scope of most clinical laboratories and requires specialized cell culture or egg yolk media. In tissue, usually liver tissue obtained in an effort to evaluate hepatitis, the histologic finding of “doughnut” granulomas, or fibrin-encased granulomas, can be suggestive of C burnetii but may be nonspecific and seen with other infections.23,34

Serologic testing with an immunofluorescence assay (IFA) remains the most common method of diagnosis. It is based on the detection of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM responses against phase I and phase II antigens of C burnetii. After initial infection, the organism displays phase I antigens and is highly infectious. When grown in culture, the organism undergoes phase shifting to a less infectious form with predominantly phase II antigens. Paradoxically, after initial infection in humans, antibody response against phase II antigens is seen first, whereas in chronic infection, a phase I antibody response dominates.26,35 Phase II antibodies appear around week 2, and 90% of samples from infected people are positive by week 3. A fourfold rise in titer between the acute-phase and convalescent-phase samples confirms the diagnosis.35

A number of serologic assays are available worldwide, but they have different methods and cutoff values, so questions have arisen about the equivalence of the results.14,36 Serologic cutoffs have been defined in Europe, where most cases of Q fever have been reported.37

CHRONIC Q FEVER

3. Which of the following would be the most likely chronic manifestation of Q fever?

- Pneumonia

- Hepatitis

- Endocarditis

- Chronic fatigue

- Osteomyelitis

Chronic syndromes can develop years to months after untreated or inadequately treated infection and can be serious. Chronic infection can also result after a clinically silent initial infection.26,38 Culture-negative endocarditis, which occurs in fewer than 1% of patients diagnosed with acute infection, is the most common chronic manifestation (Table 1). Patients with underlying valvular disease, malignancy, or immunosuppression are at greater risk.38–40

Challenges and controversies

The diagnosis of chronic Q fever remains challenging. Traditionally, elevated phase I IgG titers were considered highly predictive of chronic disease. A cutoff of 1:800 was set, based on retrospective data from chronic cases in Europe, but its generalizability to different assays and patient populations has been unclear. 14,36,37 Recent reviews and prospective analysis with serial serologic studies in the Dutch outbreak and other sources suggest the positive predictive value (PPV) of phase I IgG titers greater than 1:800 to be lower than previously estimated, largely due to widespread testing and resultant increased seroprevalence assessments. It has been suggested the cutoff be raised to 1:1,600, which still only carries a 59% positive predictive value.41,42

Chronic fatigue due to Q fever remains a controversial topic and has only been described in Europe, Asia, and Australia. A direct link has yet to be established.43 Additional research is needed, but small studies of prolonged antibiotic treatment have not shown benefit in these cases.44

CASE CONTINUED

This patient did well. During a routine physical while enrolled at the Army War College in Carlisle, PA, 6 months after the original presentation, he mentioned his illness to the physician, who then repeated testing for Q fever; the test was positive (Table 2). Subsequently, serum samples from before and after his deployment were tested along with another convalescent-phase sample, and the results demonstrated Q fever seroconversion. He was well and had no physical complaints. He had no heart murmur, and a complete blood count and tests of liver enzymes and inflammatory markers were normal.

TREATMENT AND PREVENTION OF Q FEVER

4. Which of the following treatments would be appropriate, given his diagnosis of Q fever?

- Doxycycline (Vibramycin) 100 mg twice daily for 14 days

- Levofloxacin (Levaquin) 500 mg daily for 5 days

- Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 14 days and hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 200 mg three times per day for 18 months

- No treatment

The treatment goals in Q fever are to hasten the resolution of symptoms and to prevent chronic disease. Generally, if there are no clinical findings or symptoms, treatment is not indicated. If the patient has symptoms, early treatment is preferred, but a response may be seen even when there is a delay in diagnosis.

Doxycycline 100 mg twice a day for 14 days is the treatment of choice. In addition, quinolones have in vitro activity,45 and a recent study suggests moxifloxacin (Avelox) may be the preferred antibiotic for those who cannot tolerate doxycycline.46 In pregnant women and in children, macrolides and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) are preferred.47,48

Treatment of chronic Q fever, in particular endocarditis, warrants more intensive therapy. A retrospective review of treated cases of endocarditis suggested that monotherapy with doxycycline often failed, and combination therapy with hydroxychloroquine has been advocated based on in vivo and in vitro experience.49

PREVENTING LONG-TERM SEQUELAE OF CHRONIC Q FEVER

5. At this point, what is the next step in the management of this patient?

- No further follow-up is indicated

- Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE)

- Repeat Q fever serologic testing in 3 to 6 months

- Whole-blood PCR testing and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)

Long-term follow-up of patients with Q fever has been advocated to monitor for the development of chronic Q fever, but recent studies question the previously devised algorithms.50

The data the algorithms were based on suggested that preexisting valvular heart disease could be associated with up to a 39% risk of endocarditis, and a two-step approach was devised to prevent and identify early chronic infection.51,52 Patients with Q fever would undergo TTE at baseline, and if the findings were abnormal (including mild regurgitation), then 12 months of prophylactic treatment with hydroxychloroquine and doxycycline was recommended. If TTE was normal, serial serologic testing every 3 months was recommended. If the anti-phase I IgG titer was greater than 1:800 at any point, TEE and a whole-blood PCR assay were recommended to evaluate for endocarditis.51

These recommendations were based on data from the French National Reference Center and had not been prospectively evaluated. The 2007–2008 Dutch outbreak provided a large cohort of Q fever cases. After initial screening with TTE and serologic follow-up, 59% of patients were noted to have mild valvular abnormalities, and many had phase I IgG levels greater than 1:800 during follow-up despite being clinically free of disease. The Dutch subsequently stopped screening with TTE as part of routine follow-up and elected to follow patients clinically.

Similar findings have been noted from case follow-up in France and Taiwan, also supporting using serologic cutoffs alone in determining the need for evaluation (with TEE) or treatment of chronic disease.53,54 The usefulness of serologic testing every 3 months has also been questioned, and some have advocated extending the interval, especially since less emphasis is being placed on the results in favor of more practical clinical follow-up.39

One such clinical approach at follow-up is presented in Figure 1. TTE should be reserved for patients with known valvular disease or a clear murmur. Those with underlying valvular disease and acute Q fever should be managed on an individual basis by a specialist in infectious disease, and antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered. Patients without underlying disease should have regular follow-up examinations and serologic testing every 6 months, and clinical symptoms should guide further testing (eg, with TEE and PCR testing) for chronic disease.

In this patient, phase I and II antibody titers were notably elevated (in TABLE 2, phase I titers > 1:800 and 1:1600 cutoffs). Such high titers have been common in military cases from Iraq and Afghanistan, and to date no cases of endocarditis have been diagnosed despite close follow-up. Most cases in military personnel are in relatively young patients who lack risk factors for endocarditis. Based on emerging data from large overseas outbreaks and the potential toxicity of intensive preemptive dual-antimicrobial therapy, an approach of close follow-up was taken.

PRIMARY PREVENTION OF Q FEVER

Prevention of Q fever remains a challenge, as the organism is highly persistent in the environment. An effective licensed vaccine exists in Australia under the brand name Q-Vax, but no approved vaccine is currently available in the United States.55

THE PATIENT’S COURSE

The patient returned for follow-up about 1 year after his first presentation. He noted some ongoing fatigue but attributed this to his course work, and he said he otherwise felt well. He exercises regularly, with no shortness of breath, fevers, chills, or weight loss. He continued to have elevated Q fever titers. Because he had no symptoms, no heart murmur, and normal inflammatory markers, he had no further workup and continued to be followed with serial serologic testing and examinations.

- Defense Science Board Task Force on Deployment of Members of the National Guard and Reserve in the Global War on Terrorism. Washington, DC. September 2007.

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73:713–719.

- Gleeson TD, Decker CF, Johnson MD, Hartzell JD, Mascola JR. Q fever in US military returning from Iraq. Am J Med 2007; 120:e11–e12.

- Hagan JE, Marcos LA, Steinberg TH. Fever in a soldier returned from Afghanistan. J Travel Med 2010; 17:351–352.

- Aronson NE, Sanders JW, Moran KA. In harm’s way: infections in deployed American military forces. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1045–1051.

- Klein TA, Pacha LA, Lee HC, et al. Plasmodium vivax malaria among U.S. forces Korea in the Republic of Korea, 1993–2007. Mil Med 2009; 174:412–418.

- Ciminera P, Brundage J. Malaria in U.S. military forces: a description of deployment exposures from 2003 through 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76:275–279.

- Lesho EP, Wortmann G, Neafie R, Aronson N. Nonhealing skin lesions in a sailor and a journalist returning from Iraq. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:93–96,

- Myles O, Wortmann GW, Cummings JF, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: clinical observations in 4 US army soldiers deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq, 2002–2004. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167:1899–1901.

- Faix DJ, Harrison DJ, Riddle MS, et al. Outbreak of Q fever among US military in western Iraq, June–July 2005. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:e65–e68.

- Leung-Shea C, Danaher PJ. Q fever in members of the United States armed forces returning from Iraq. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:e77–e82.

- Anderson AD, Smoak B, Shuping E, Ockenhouse C, Petruccelli B. Q fever and the US military. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11:1320–1322.

- Anderson AD, Baker TR, Littrell AC, Mott RL, Niebuhr DW, Smoak BL. Seroepidemiologic survey for Coxiella burnetii among hospitalized US troops deployed to Iraq. Zoonoses Public Health 2011; 58:276–283.

- Ake JA, Massung RF, Whitman TJ, Gleeson TD. Difficulties in the diagnosis and management of a US servicemember presenting with possible chronic Q fever. J Infect 2010; 60:175–177.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Potential for Q fever infection among travelers returning from Iraq and the Netherlands http://www.bt.cdc.gov/HAN/han00313.asp. Accessed July 5, 2012.

- Parker NR, Barralet JH, Bell AM. Q fever. Lancet 2006; 367:679–688.

- Miceli MH, Veryser AK, Anderson AD, Hofinger D, Lee SA, Tancik C. A case of person-to-person transmission of Q fever from an active duty serviceman to his spouse. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2010; 10:539–541.

- Milazzo A, Hall R, Storm PA, Harris RJ, Winslow W, Marmion BP. Sexually transmitted Q fever. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:399–402.

- Hartzell JD, Peng SW, Wood-Morris RN, et al. Atypical Q fever in US soldiers. Emerg Infect Dis 2007; 13:1247–1249.

- Bossi P, Tegnell A, Baka A, et al; Task Force on Biological and Chemical Agent Threats, Public Health Directorate, European Commission, Luxembourg. Bichat guidelines for the clinical management of Q fever and bioterrorism-related Q fever. Euro Surveill 2004; 9:E19–E20.

- Roest HI, Tilburg JJ, van der Hoek W, et al. The Q fever epidemic in The Netherlands: history, onset, response and reflection. Epidemiol Infect 2011; 139:1–12.

- Anderson AD, Kruszon-Moran D, Loftis AD, et al. Seroprevalence of Q fever in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009; 81:691–694.

- Hatchette TF, Marrie TJ. Atypical manifestations of chronic Q fever. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:1347–1351.

- Bernit E, Pouget J, Janbon F, et al. Neurological involvement in acute Q fever: a report of 29 cases and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162:693–700.

- Kofteridis DP, Mazokopakis EE, Tselentis Y, Gikas A. Neurological complications of acute Q fever infection. Eur J Epidemiol 2004; 19:1051–1054.

- Raoult D, Marrie T, Mege J. Natural history and pathophysiology of Q fever. Lancet Infect Dis 2005; 5:219–226.

- Kampschreur LM, Wegdam-Blans MC, Thijsen SF, et al. Acute Q fever related in-hospital mortality in the Netherlands. Neth J Med 2010; 68:408–413.

- Srivastava P, Dayama A, Mehrotra S, Sundar S. Diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2011; 105:1–6.

- Chappuis F, Rijal S, Soto A, Menten J, Boelaert M. A meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of the direct agglutination test and rK39 dipstick for visceral leishmaniasis. BMJ 2006; 333:723.

- Hartzell JD, Aronson NE, Weina PJ, Howard RS, Yadava A, Wortmann GW. Positive rK39 serologic assay results in US servicemen with cutaneous leishmaniasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2008; 79:843–846.

- Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, Tsianos E. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2325–2336.

- Schneeberger PM, Hermans MH, van Hannen EJ, Schellekens JJ, Leenders AC, Wever PC. Real-time PCR with serum samples is indispensable for early diagnosis of acute Q fever. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2010; 17:286–290.

- Hamilton LR, George DL, Scoville SL, Hospenthal DR, Griffith ME. PCR for rapid diagnosis of acute Q fever at a combat support hospital in Iraq. Mil Med 2011; 176:103–105.

- Bonilla MF, Kaul DR, Saint S, Isada CM, Brotman DJ. Clinical problem-solving. Ring around the diagnosis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1937–1942.

- Fournier PE, Marrie TJ, Raoult D. Diagnosis of Q fever. J Clin Microbiol 1998; 36:1823–1834.

- Healy B, van Woerden H, Raoult D, et al. Chronic Q fever: different serological results in three countries—results of a follow-up study 6 years after a point source outbreak. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:1013–1019.

- Dupont HT, Thirion X, Raoult D. Q fever serology: cutoff determination for microimmunofluorescence. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1994; 1:189–196.

- Karakousis PC, Trucksis M, Dumler JS. Chronic Q fever in the United States. J Clin Microbiol 2006; 44:2283–2287.

- van der Hoek W, Versteeg B, Meekelenkamp JC, et al. Follow-up of 686 patients with acute Q fever and detection of chronic infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:1431–1436.

- Fenollar F, Fournier PE, Carrieri MP, Habib G, Messana T, Raoult D. Risks factors and prevention of Q fever endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 33:312–316.

- Frankel D, Richet H, Renvoisé A, Raoult D. Q fever in France, 1985–2009. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:350–356.

- Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al; Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; American Heart Association; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation 2005; 111:e394–e434.

- Wildman MJ, Smith EG, Groves J, Beattie JM, Caul EO, Ayres JG. Chronic fatigue following infection by Coxiella burnetii (Q fever): ten-year follow-up of the 1989 UK outbreak cohort. QJM 2002; 95:527–538.

- Iwakami E, Arashima Y, Kato K, et al. Treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome with antibiotics: pilot study assessing the involvement of Coxiella burnetii infection. Intern Med 2005; 44:1258–1263.

- Rolain JM, Maurin M, Raoult D. Bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities of moxifloxacin against Coxiella burnetii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001; 45:301–302.

- Dijkstra F, Riphagen-Dalhuisen J, Wijers N, et al. Antibiotic therapy for acute Q fever in The Netherlands in 2007 and 2008 and its relation to hospitalization. Epidemiol Infect 2011; 139:1332–1341.

- Raoult D. Use of macrolides for Q fever. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2003; 47:446.

- Carcopino X, Raoult D, Bretelle F, Boubli L, Stein A. Managing Q fever during pregnancy: the benefits of long-term cotrimoxazole therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:548–555.

- Raoult D, Houpikian P, Tissot Dupont H, Riss JM, Arditi-Djiane J, Brouqui P. Treatment of Q fever endocarditis: comparison of 2 regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:167–173.

- Healy B, Llewelyn M, Westmoreland D, Lloyd G, Brown N. The value of follow-up after acute Q fever infection. J Infect 2006; 52:e109–e112.

- Landais C, Fenollar F, Thuny F, Raoult D. From acute Q fever to endocarditis: serological follow-up strategy. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:1337–1340.

- Hartzell JD, Wood-Morris RN, Martinez LJ, Trotta RF. Q fever: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83:574–579.

- Hung MN, Lin LJ, Hou MY, et al. Serologic assessment of the risk of developing chronic Q fever in cohorts of acutely infected individuals. J Infect 2011; 62:39–44.

- Sunder S, Gras G, Bastides F, De Gialluly C, Choutet P, Bernard L. Chronic Q fever: relevance of serology. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:749–750.

- Gefenaite G, Munster JM, van Houdt R, Hak E. Effectiveness of the Q fever vaccine: a meta-analysis. Vaccine 2011; 29:395–398.

- Defense Science Board Task Force on Deployment of Members of the National Guard and Reserve in the Global War on Terrorism. Washington, DC. September 2007.

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005; 73:713–719.

- Gleeson TD, Decker CF, Johnson MD, Hartzell JD, Mascola JR. Q fever in US military returning from Iraq. Am J Med 2007; 120:e11–e12.

- Hagan JE, Marcos LA, Steinberg TH. Fever in a soldier returned from Afghanistan. J Travel Med 2010; 17:351–352.

- Aronson NE, Sanders JW, Moran KA. In harm’s way: infections in deployed American military forces. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1045–1051.

- Klein TA, Pacha LA, Lee HC, et al. Plasmodium vivax malaria among U.S. forces Korea in the Republic of Korea, 1993–2007. Mil Med 2009; 174:412–418.

- Ciminera P, Brundage J. Malaria in U.S. military forces: a description of deployment exposures from 2003 through 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2007; 76:275–279.

- Lesho EP, Wortmann G, Neafie R, Aronson N. Nonhealing skin lesions in a sailor and a journalist returning from Iraq. Cleve Clin J Med 2005; 72:93–96,