User login

The Numerators: Treating Noncompliant, Medically Complicated Hospital Patients

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

Reference

Interfacility Transfers to Pediatric Academic EDs Often Discharged or Admitted Briefly

Clinical question: What are the characteristics of interfacility transfers to pediatric academic EDs?

Background: The majority of pediatric ED visits (89%) and hospital admissions (69%) occur via general hospital EDs, not freestanding academic children's hospitals. Pediatric hospitalists often provide consultation services in these community hospital settings and might be the primary admitting team in either setting (community hospital or children's hospital). Questions concerning the quality of pediatric ED care in community hospitals have been raised, with acknowledged improvements in post-transfer care for critically ill patients. The characteristics of less acutely ill transfers are unknown and could provide insight into opportunities for improvement.

Study design: Cross-sectional, retrospective database review.

Setting: Twenty-nine tertiary-care pediatric hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database of the Child Health Corporation of America was reviewed; over a one-year period, 24,905 interfacility transfers were identified from 29 hospitals. Fifty-eight percent of patients were admitted for more than 24 hours with common respiratory illnesses (pneumonia, bronchiolitis, asthma) and surgical conditions representing the most common diagnostic categories. Among the remaining patients, 24.7% were discharged directly from the academic pediatric EDs; 17% were admitted for less than 24 hours. Among those discharged or briefly admitted, common nonsurgical diagnostic categories included abdominal pain, viral gastroenteritis/dehydration, and other gastrointestinal conditions.

The authors attempted to define areas for improvement in pediatric care in community hospital EDs. Limitations of their analysis include the use of a database without validated code for source of admission, as well as an inability to drill down further into the specifics of what additional expertise was provided at the pediatric EDs. However, this study provides a platform by which pediatric hospitalists can view and subsequently improve the value of their regional care systems.

Bottom line: Interfacility transfers to pediatric academic EDs might offer an opportunity for improved pediatric care in community hospital EDs.

Citation: Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130:83-92.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What are the characteristics of interfacility transfers to pediatric academic EDs?

Background: The majority of pediatric ED visits (89%) and hospital admissions (69%) occur via general hospital EDs, not freestanding academic children's hospitals. Pediatric hospitalists often provide consultation services in these community hospital settings and might be the primary admitting team in either setting (community hospital or children's hospital). Questions concerning the quality of pediatric ED care in community hospitals have been raised, with acknowledged improvements in post-transfer care for critically ill patients. The characteristics of less acutely ill transfers are unknown and could provide insight into opportunities for improvement.

Study design: Cross-sectional, retrospective database review.

Setting: Twenty-nine tertiary-care pediatric hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database of the Child Health Corporation of America was reviewed; over a one-year period, 24,905 interfacility transfers were identified from 29 hospitals. Fifty-eight percent of patients were admitted for more than 24 hours with common respiratory illnesses (pneumonia, bronchiolitis, asthma) and surgical conditions representing the most common diagnostic categories. Among the remaining patients, 24.7% were discharged directly from the academic pediatric EDs; 17% were admitted for less than 24 hours. Among those discharged or briefly admitted, common nonsurgical diagnostic categories included abdominal pain, viral gastroenteritis/dehydration, and other gastrointestinal conditions.

The authors attempted to define areas for improvement in pediatric care in community hospital EDs. Limitations of their analysis include the use of a database without validated code for source of admission, as well as an inability to drill down further into the specifics of what additional expertise was provided at the pediatric EDs. However, this study provides a platform by which pediatric hospitalists can view and subsequently improve the value of their regional care systems.

Bottom line: Interfacility transfers to pediatric academic EDs might offer an opportunity for improved pediatric care in community hospital EDs.

Citation: Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130:83-92.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: What are the characteristics of interfacility transfers to pediatric academic EDs?

Background: The majority of pediatric ED visits (89%) and hospital admissions (69%) occur via general hospital EDs, not freestanding academic children's hospitals. Pediatric hospitalists often provide consultation services in these community hospital settings and might be the primary admitting team in either setting (community hospital or children's hospital). Questions concerning the quality of pediatric ED care in community hospitals have been raised, with acknowledged improvements in post-transfer care for critically ill patients. The characteristics of less acutely ill transfers are unknown and could provide insight into opportunities for improvement.

Study design: Cross-sectional, retrospective database review.

Setting: Twenty-nine tertiary-care pediatric hospitals.

Synopsis: The Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database of the Child Health Corporation of America was reviewed; over a one-year period, 24,905 interfacility transfers were identified from 29 hospitals. Fifty-eight percent of patients were admitted for more than 24 hours with common respiratory illnesses (pneumonia, bronchiolitis, asthma) and surgical conditions representing the most common diagnostic categories. Among the remaining patients, 24.7% were discharged directly from the academic pediatric EDs; 17% were admitted for less than 24 hours. Among those discharged or briefly admitted, common nonsurgical diagnostic categories included abdominal pain, viral gastroenteritis/dehydration, and other gastrointestinal conditions.

The authors attempted to define areas for improvement in pediatric care in community hospital EDs. Limitations of their analysis include the use of a database without validated code for source of admission, as well as an inability to drill down further into the specifics of what additional expertise was provided at the pediatric EDs. However, this study provides a platform by which pediatric hospitalists can view and subsequently improve the value of their regional care systems.

Bottom line: Interfacility transfers to pediatric academic EDs might offer an opportunity for improved pediatric care in community hospital EDs.

Citation: Li J, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Interfacility transfers of noncritically ill children to academic pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2012;130:83-92.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Recommendations for Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy

Background

Each year, 1 million people are hospitalized with a diagnosis of stroke; it was the fourth-leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2009 and 2010.1 The majority of strokes (80%) are caused by focal cerebral ischemia, and the remainder are caused by hemorrhage.1 In 2008, the direct medical costs of stroke were approximately $18.8 billion, with almost half of this amount directed toward hospitalization.1 Although stroke inpatients make up only 3% of total hospitalizations, the mortality rate is more than twice that of other patients’.1

Over the past several decades, much has been learned about the pathophysiology and treatment for ischemic stroke. The mainstays of therapies include restoring perfusion in a timely manner and targeting both clot formation and hemostasis. These therapies improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of recurrence in appropriately selected populations.

Guideline Update

In February, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) published new practice guidelines for medical patients regarding antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke.2 These evidence-based guidelines are the result of new clinical trial data and a review of previous studies. They address three aspects of management decisions for stroke, including acute treatment, VTE prevention, and secondary prevention, as well as specifically address the treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

In the management of acute ischemic stroke, several recommendations were made. In terms of IV recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-tPA) administration, the guidelines were expanded and allow for a less restrictive time threshold for administration. Previous recommendations limited the usage of IV r-tPA to within three hours of symptom onset in acute ischemic stroke. A science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) from 2009 extended that window to 4.5 hours. The 2012 ACCP guidelines have followed suit to extend this time to 4.5 hours from symptom onset as well.

In addition, intrarterial r-tPA can be given in patients not eligible for IV r-tPA within six hours of presentation of acute ischemic stroke due to proximal cerebral artery occlusion.

These updated acute stroke guidelines recommend against the use of mechanical thrombectomy based mostly on lack of data rather than lack of benefit.2

The new guidelines continue to recommend early aspirin therapy at a dosage of 160 mg to 325 mg within the first 48 hours of acute ischemic stroke. Therapeutic parenteral anticoagulation with heparin or related drugs was not recommended in patients with noncardioembolic stroke due to atrial fibrillation (afib) or in patients with stroke due to large artery stenosis or arterial dissection. In this updated analysis, there was no benefit of anticoagulation compared with antiplatelet therapy, and the risk for extracranial hemorrhage was increased. No specific recommendation regarding anticoagulation was made in patients with mechanical heart valves or intracardiac thrombus.

Updates have been made for VTE prophylaxis in patients hospitalized for acute stroke. In stroke patients with restricted mobility, prophylactic unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and/or intermittent pneumatic compression devices should be initiated as early as possible. The panel is no longer recommending elastic compression stockings as VTE prevention given the risk of skin damage and no clear benefit in symptomatic VTE prevention. For patients with hemorrhagic stroke and restricted mobility, similar recommendations were made for VTE prevention, except to start pharmacologic treatment between days 2 and 4 of the hospital stay. However, if there is a bleeding concern, intermittent pneumatic compression devices are favored over pharmacologic prophylaxis. In all patients for whom pharmacologic prevention is utilized, prophylactic LMWH is preferred over UFH.

Secondary stroke prevention is addressed, with 2012 guidelines outlining a preference for clopidogrel or aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole rather than aspirin or cilostazol in patients with a history of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA. Oral anticoagulation is preferred in patients with a history of stroke or TIA with afib over aspirin alone, aspirin plus clopidogrel, or no antithrombotic therapy. Of the available anticoagulants, the panel recommended dabigatran 150 mg twice daily over adjusted-dose warfarin.2 This recommendation is based on results from the RE-LY trial, which showed dabigatran as noninferior to warfarin in patients with nonvalvular afib without severe renal failure or advanced liver disease.3

For patients who have contraindications or choose not to initiate anticoagulation, the combination of aspirin (ASA) and clopidogrel is a reasonable alternative. Timing of the initiation of oral anticoagulation should be between one and two weeks after the stroke. Patients with extensive infarction or hemorrhagic transformation should delay starting oral anticoagulation, with no exact timeline. Long-term antithrombotic therapy is contraindicated in patients with history of a symptomatic primary intracerebral hemorrhage.2 New guidelines also recommend full anticoagulation for patients with symptomatic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

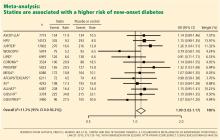

The panel did not make any recommendations regarding statin usage. In several studies, findings showed that statins reduced infarct size and had improved outcome in all stroke types.4

Analysis

Prior to the 2012 update, the last guideline for antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke was published by the ACCP in the June 2008 issue of Chest.5 Dating back to 2001, medications included r-tPA administration within three hours of stroke symptom onset, and aspirin, clopidogrel, or a com bination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole for stroke prophylaxis.

The management of stroke continues to focus on early intervention and secondary prevention. Thrombolytic therapy is an effective treatment of acute ischemic stroke if given within the narrow window from onset of stroke symptoms up to 4.5 hours, with the goal of treatment within a three-hour window. Beyond this time constraint, the risk outweighs the benefit of using r-tPA except in the case of intra-arterial r-tPA administration for proximal cerebral artery occlusion.

In 2010, a meta-analysis supported this by showing that the risk of death increased significantly in patients receiving r-tPA beyond 4.5 hours. Therefore, antiplatelet therapy is the best alternative for patients ineligible for thrombolytic therapy.6 Even so, that study offered little data for patients with mechanical heart valves or intracardiac thrombi. Thus, the choice for acute anticoagulation therapy is variable and uncertain. If the hemorrhagic risk is low, anticoagulation can be considered in this subgroup, but no specific guideline endorsement was made.

In 2011, the AHA/ASA published an updated treatment guideline for patients with stroke or TIA. This was an update to 2007 guidelines that outlined the early management of ischemic stroke and affirmed the benefit of IV r-tPA at 4.5 hours for the treatment of stroke.7 Of note, IV r-tPA is only FDA-approved for treatment of acute ischemic stroke within the previously recommended three-hour period from symptom onset.

Aspirin has been found to be effective in both early treatment of acute ischemic stroke and secondary prevention. The CAST trial showed a statistically significant rate of reduction of nonfatal strokes with the use of aspirin. Other antiplatelet agents, including clopidogrel and dipyridamole, can be used. The FASTER trial compared aspirin alone versus aspirin plus clopidogrel, with no difference in outcome measures, although the MATCH trial found a larger risk of hemorrhagic and bleeding complications in the acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)-plus-clopidogrel group.6,7

In TIA or stroke patients, clopidogrel is not superior to ASA in preventing recurrent stroke. However, patients who have peripheral artery disease (PAD), previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), or recurrent vascular events show a benefit of transitioning from ASA to clopidogrel for secondary long-term prevention. Clopidogrel or aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole is preferred over aspirin alone or cilostazol for long-term treatment in patients with a history of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA based on the PROFESS trial.2,7

HM Takeaways

The 2012 guidelines are a resource available to hospitalists for treating acute ischemic stroke either alone or with neurology consultation. These guidelines further define the timing of r-tPA and the use of both anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in the proper clinical settings.

In terms of VTE prevention, the guidelines recommend using LMWH preferentially over UH, except in patients at risk for rebleeding. The clinician should be aware of the treatment considerations for secondary prevention, noting the primary role of aspirin therapy in ischemic stroke with consideration of other agents (i.e. clopidogrel) in select populations.

Drs. Barr and Schumacher are hospitalists and assistant professors in the division of hospital medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine in Columbus.

References

Available at the-hospitalist.org.

Background

Each year, 1 million people are hospitalized with a diagnosis of stroke; it was the fourth-leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2009 and 2010.1 The majority of strokes (80%) are caused by focal cerebral ischemia, and the remainder are caused by hemorrhage.1 In 2008, the direct medical costs of stroke were approximately $18.8 billion, with almost half of this amount directed toward hospitalization.1 Although stroke inpatients make up only 3% of total hospitalizations, the mortality rate is more than twice that of other patients’.1

Over the past several decades, much has been learned about the pathophysiology and treatment for ischemic stroke. The mainstays of therapies include restoring perfusion in a timely manner and targeting both clot formation and hemostasis. These therapies improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of recurrence in appropriately selected populations.

Guideline Update

In February, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) published new practice guidelines for medical patients regarding antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke.2 These evidence-based guidelines are the result of new clinical trial data and a review of previous studies. They address three aspects of management decisions for stroke, including acute treatment, VTE prevention, and secondary prevention, as well as specifically address the treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

In the management of acute ischemic stroke, several recommendations were made. In terms of IV recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-tPA) administration, the guidelines were expanded and allow for a less restrictive time threshold for administration. Previous recommendations limited the usage of IV r-tPA to within three hours of symptom onset in acute ischemic stroke. A science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) from 2009 extended that window to 4.5 hours. The 2012 ACCP guidelines have followed suit to extend this time to 4.5 hours from symptom onset as well.

In addition, intrarterial r-tPA can be given in patients not eligible for IV r-tPA within six hours of presentation of acute ischemic stroke due to proximal cerebral artery occlusion.

These updated acute stroke guidelines recommend against the use of mechanical thrombectomy based mostly on lack of data rather than lack of benefit.2

The new guidelines continue to recommend early aspirin therapy at a dosage of 160 mg to 325 mg within the first 48 hours of acute ischemic stroke. Therapeutic parenteral anticoagulation with heparin or related drugs was not recommended in patients with noncardioembolic stroke due to atrial fibrillation (afib) or in patients with stroke due to large artery stenosis or arterial dissection. In this updated analysis, there was no benefit of anticoagulation compared with antiplatelet therapy, and the risk for extracranial hemorrhage was increased. No specific recommendation regarding anticoagulation was made in patients with mechanical heart valves or intracardiac thrombus.

Updates have been made for VTE prophylaxis in patients hospitalized for acute stroke. In stroke patients with restricted mobility, prophylactic unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and/or intermittent pneumatic compression devices should be initiated as early as possible. The panel is no longer recommending elastic compression stockings as VTE prevention given the risk of skin damage and no clear benefit in symptomatic VTE prevention. For patients with hemorrhagic stroke and restricted mobility, similar recommendations were made for VTE prevention, except to start pharmacologic treatment between days 2 and 4 of the hospital stay. However, if there is a bleeding concern, intermittent pneumatic compression devices are favored over pharmacologic prophylaxis. In all patients for whom pharmacologic prevention is utilized, prophylactic LMWH is preferred over UFH.

Secondary stroke prevention is addressed, with 2012 guidelines outlining a preference for clopidogrel or aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole rather than aspirin or cilostazol in patients with a history of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA. Oral anticoagulation is preferred in patients with a history of stroke or TIA with afib over aspirin alone, aspirin plus clopidogrel, or no antithrombotic therapy. Of the available anticoagulants, the panel recommended dabigatran 150 mg twice daily over adjusted-dose warfarin.2 This recommendation is based on results from the RE-LY trial, which showed dabigatran as noninferior to warfarin in patients with nonvalvular afib without severe renal failure or advanced liver disease.3

For patients who have contraindications or choose not to initiate anticoagulation, the combination of aspirin (ASA) and clopidogrel is a reasonable alternative. Timing of the initiation of oral anticoagulation should be between one and two weeks after the stroke. Patients with extensive infarction or hemorrhagic transformation should delay starting oral anticoagulation, with no exact timeline. Long-term antithrombotic therapy is contraindicated in patients with history of a symptomatic primary intracerebral hemorrhage.2 New guidelines also recommend full anticoagulation for patients with symptomatic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

The panel did not make any recommendations regarding statin usage. In several studies, findings showed that statins reduced infarct size and had improved outcome in all stroke types.4

Analysis

Prior to the 2012 update, the last guideline for antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke was published by the ACCP in the June 2008 issue of Chest.5 Dating back to 2001, medications included r-tPA administration within three hours of stroke symptom onset, and aspirin, clopidogrel, or a com bination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole for stroke prophylaxis.

The management of stroke continues to focus on early intervention and secondary prevention. Thrombolytic therapy is an effective treatment of acute ischemic stroke if given within the narrow window from onset of stroke symptoms up to 4.5 hours, with the goal of treatment within a three-hour window. Beyond this time constraint, the risk outweighs the benefit of using r-tPA except in the case of intra-arterial r-tPA administration for proximal cerebral artery occlusion.

In 2010, a meta-analysis supported this by showing that the risk of death increased significantly in patients receiving r-tPA beyond 4.5 hours. Therefore, antiplatelet therapy is the best alternative for patients ineligible for thrombolytic therapy.6 Even so, that study offered little data for patients with mechanical heart valves or intracardiac thrombi. Thus, the choice for acute anticoagulation therapy is variable and uncertain. If the hemorrhagic risk is low, anticoagulation can be considered in this subgroup, but no specific guideline endorsement was made.

In 2011, the AHA/ASA published an updated treatment guideline for patients with stroke or TIA. This was an update to 2007 guidelines that outlined the early management of ischemic stroke and affirmed the benefit of IV r-tPA at 4.5 hours for the treatment of stroke.7 Of note, IV r-tPA is only FDA-approved for treatment of acute ischemic stroke within the previously recommended three-hour period from symptom onset.

Aspirin has been found to be effective in both early treatment of acute ischemic stroke and secondary prevention. The CAST trial showed a statistically significant rate of reduction of nonfatal strokes with the use of aspirin. Other antiplatelet agents, including clopidogrel and dipyridamole, can be used. The FASTER trial compared aspirin alone versus aspirin plus clopidogrel, with no difference in outcome measures, although the MATCH trial found a larger risk of hemorrhagic and bleeding complications in the acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)-plus-clopidogrel group.6,7

In TIA or stroke patients, clopidogrel is not superior to ASA in preventing recurrent stroke. However, patients who have peripheral artery disease (PAD), previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), or recurrent vascular events show a benefit of transitioning from ASA to clopidogrel for secondary long-term prevention. Clopidogrel or aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole is preferred over aspirin alone or cilostazol for long-term treatment in patients with a history of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA based on the PROFESS trial.2,7

HM Takeaways

The 2012 guidelines are a resource available to hospitalists for treating acute ischemic stroke either alone or with neurology consultation. These guidelines further define the timing of r-tPA and the use of both anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in the proper clinical settings.

In terms of VTE prevention, the guidelines recommend using LMWH preferentially over UH, except in patients at risk for rebleeding. The clinician should be aware of the treatment considerations for secondary prevention, noting the primary role of aspirin therapy in ischemic stroke with consideration of other agents (i.e. clopidogrel) in select populations.

Drs. Barr and Schumacher are hospitalists and assistant professors in the division of hospital medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine in Columbus.

References

Available at the-hospitalist.org.

Background

Each year, 1 million people are hospitalized with a diagnosis of stroke; it was the fourth-leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2009 and 2010.1 The majority of strokes (80%) are caused by focal cerebral ischemia, and the remainder are caused by hemorrhage.1 In 2008, the direct medical costs of stroke were approximately $18.8 billion, with almost half of this amount directed toward hospitalization.1 Although stroke inpatients make up only 3% of total hospitalizations, the mortality rate is more than twice that of other patients’.1

Over the past several decades, much has been learned about the pathophysiology and treatment for ischemic stroke. The mainstays of therapies include restoring perfusion in a timely manner and targeting both clot formation and hemostasis. These therapies improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of recurrence in appropriately selected populations.

Guideline Update

In February, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) published new practice guidelines for medical patients regarding antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic stroke.2 These evidence-based guidelines are the result of new clinical trial data and a review of previous studies. They address three aspects of management decisions for stroke, including acute treatment, VTE prevention, and secondary prevention, as well as specifically address the treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

In the management of acute ischemic stroke, several recommendations were made. In terms of IV recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (r-tPA) administration, the guidelines were expanded and allow for a less restrictive time threshold for administration. Previous recommendations limited the usage of IV r-tPA to within three hours of symptom onset in acute ischemic stroke. A science advisory from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) from 2009 extended that window to 4.5 hours. The 2012 ACCP guidelines have followed suit to extend this time to 4.5 hours from symptom onset as well.

In addition, intrarterial r-tPA can be given in patients not eligible for IV r-tPA within six hours of presentation of acute ischemic stroke due to proximal cerebral artery occlusion.

These updated acute stroke guidelines recommend against the use of mechanical thrombectomy based mostly on lack of data rather than lack of benefit.2

The new guidelines continue to recommend early aspirin therapy at a dosage of 160 mg to 325 mg within the first 48 hours of acute ischemic stroke. Therapeutic parenteral anticoagulation with heparin or related drugs was not recommended in patients with noncardioembolic stroke due to atrial fibrillation (afib) or in patients with stroke due to large artery stenosis or arterial dissection. In this updated analysis, there was no benefit of anticoagulation compared with antiplatelet therapy, and the risk for extracranial hemorrhage was increased. No specific recommendation regarding anticoagulation was made in patients with mechanical heart valves or intracardiac thrombus.

Updates have been made for VTE prophylaxis in patients hospitalized for acute stroke. In stroke patients with restricted mobility, prophylactic unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) and/or intermittent pneumatic compression devices should be initiated as early as possible. The panel is no longer recommending elastic compression stockings as VTE prevention given the risk of skin damage and no clear benefit in symptomatic VTE prevention. For patients with hemorrhagic stroke and restricted mobility, similar recommendations were made for VTE prevention, except to start pharmacologic treatment between days 2 and 4 of the hospital stay. However, if there is a bleeding concern, intermittent pneumatic compression devices are favored over pharmacologic prophylaxis. In all patients for whom pharmacologic prevention is utilized, prophylactic LMWH is preferred over UFH.

Secondary stroke prevention is addressed, with 2012 guidelines outlining a preference for clopidogrel or aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole rather than aspirin or cilostazol in patients with a history of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA. Oral anticoagulation is preferred in patients with a history of stroke or TIA with afib over aspirin alone, aspirin plus clopidogrel, or no antithrombotic therapy. Of the available anticoagulants, the panel recommended dabigatran 150 mg twice daily over adjusted-dose warfarin.2 This recommendation is based on results from the RE-LY trial, which showed dabigatran as noninferior to warfarin in patients with nonvalvular afib without severe renal failure or advanced liver disease.3

For patients who have contraindications or choose not to initiate anticoagulation, the combination of aspirin (ASA) and clopidogrel is a reasonable alternative. Timing of the initiation of oral anticoagulation should be between one and two weeks after the stroke. Patients with extensive infarction or hemorrhagic transformation should delay starting oral anticoagulation, with no exact timeline. Long-term antithrombotic therapy is contraindicated in patients with history of a symptomatic primary intracerebral hemorrhage.2 New guidelines also recommend full anticoagulation for patients with symptomatic cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.

The panel did not make any recommendations regarding statin usage. In several studies, findings showed that statins reduced infarct size and had improved outcome in all stroke types.4

Analysis

Prior to the 2012 update, the last guideline for antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for ischemic stroke was published by the ACCP in the June 2008 issue of Chest.5 Dating back to 2001, medications included r-tPA administration within three hours of stroke symptom onset, and aspirin, clopidogrel, or a com bination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole for stroke prophylaxis.

The management of stroke continues to focus on early intervention and secondary prevention. Thrombolytic therapy is an effective treatment of acute ischemic stroke if given within the narrow window from onset of stroke symptoms up to 4.5 hours, with the goal of treatment within a three-hour window. Beyond this time constraint, the risk outweighs the benefit of using r-tPA except in the case of intra-arterial r-tPA administration for proximal cerebral artery occlusion.

In 2010, a meta-analysis supported this by showing that the risk of death increased significantly in patients receiving r-tPA beyond 4.5 hours. Therefore, antiplatelet therapy is the best alternative for patients ineligible for thrombolytic therapy.6 Even so, that study offered little data for patients with mechanical heart valves or intracardiac thrombi. Thus, the choice for acute anticoagulation therapy is variable and uncertain. If the hemorrhagic risk is low, anticoagulation can be considered in this subgroup, but no specific guideline endorsement was made.

In 2011, the AHA/ASA published an updated treatment guideline for patients with stroke or TIA. This was an update to 2007 guidelines that outlined the early management of ischemic stroke and affirmed the benefit of IV r-tPA at 4.5 hours for the treatment of stroke.7 Of note, IV r-tPA is only FDA-approved for treatment of acute ischemic stroke within the previously recommended three-hour period from symptom onset.

Aspirin has been found to be effective in both early treatment of acute ischemic stroke and secondary prevention. The CAST trial showed a statistically significant rate of reduction of nonfatal strokes with the use of aspirin. Other antiplatelet agents, including clopidogrel and dipyridamole, can be used. The FASTER trial compared aspirin alone versus aspirin plus clopidogrel, with no difference in outcome measures, although the MATCH trial found a larger risk of hemorrhagic and bleeding complications in the acetylsalicylic acid (ASA)-plus-clopidogrel group.6,7

In TIA or stroke patients, clopidogrel is not superior to ASA in preventing recurrent stroke. However, patients who have peripheral artery disease (PAD), previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), or recurrent vascular events show a benefit of transitioning from ASA to clopidogrel for secondary long-term prevention. Clopidogrel or aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole is preferred over aspirin alone or cilostazol for long-term treatment in patients with a history of noncardioembolic ischemic stroke or TIA based on the PROFESS trial.2,7

HM Takeaways

The 2012 guidelines are a resource available to hospitalists for treating acute ischemic stroke either alone or with neurology consultation. These guidelines further define the timing of r-tPA and the use of both anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy in the proper clinical settings.

In terms of VTE prevention, the guidelines recommend using LMWH preferentially over UH, except in patients at risk for rebleeding. The clinician should be aware of the treatment considerations for secondary prevention, noting the primary role of aspirin therapy in ischemic stroke with consideration of other agents (i.e. clopidogrel) in select populations.

Drs. Barr and Schumacher are hospitalists and assistant professors in the division of hospital medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine in Columbus.

References

Available at the-hospitalist.org.

John Nelson: Peformance Key to Federal Value-Based Payment Modifier Plan

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

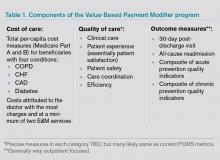

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

For years, your hospital was paid additional money by Medicare to report its performance on such things as core measures. Medicare then shared that information with the public via www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov. Even if the hospital never gave Pneumovax when indicated, it was paid more simply for reporting that fact. (Fortunately, there were lots of reasons hospitals wanted to perform well.)

The days of hospitals being paid more simply for reporting ended a long time ago. Now performance, e.g., how often Pneumovax was given when indicated, influences payment. That is, things have transitioned from pay-for-reporting to a pay-for-performance program called hospital value-based purchasing (VBP).

I hope that at least one member of your hospitalist group is keeping up with hospital VBP. It got a lot of attention in the fall because it was the first time Medicare Part A payments to hospitals were adjusted based on performance on some core measures and patient satisfaction domains, as well as readmission rates for congestive heart failure (CHF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), and pneumonia patients. The dollars at stake and performance metrics change will change every year, so plan to pay attention to hospital VBP on an ongoing basis.

Physicians’ Turn

Medicare payment to physicians is evolving along the same trajectory as hospitals. For several years, doctors have had the option to voluntarily participate in the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS). As long as a doctor reported quality performance on a sufficient portion of certain patient types, Medicare would provide a “bonus” at the end of the year. From 2012 through 2014, the “bonus” is 0.5% of that doctor’s total allowable Medicare charges. For example, if that doctor generated $150,000 of Medicare allowable charges over the calendar year, the additional payment for successful reporting PQRS would be $750 (0.5% of $150,000).

Although $750 is only a tiny fraction of collections, the right charge-capture system can make it pretty easy to achieve. And an extra payment of $750 sure is better than the 1.5% penalty for not participating; that program starts in 2015 and increases to a 2% penalty in 2016. If you are still not participating successfully in PQRS in 2015, the reimbursement for that $150,000 in charges will be reduced by $2,250 (1.5% of $150,000). So I strongly recommend that you begin reporting in 2013 so that you have time to work out the kinks well ahead of 2015. Don’t delay, but don’t panic, either, because you can still succeed in 2013 even if you don’t start capturing or reporting PQRS data until late winter or early spring.

At some point in the next year or so, data from as early as January 2013 for doctors reporting through PQRS will be made public on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid’s (CMS) physician compare website: www.medicare.gov/find-a-doctor/provider-search.aspx. For example, should you choose to report the portion of stroke patients for whom you prescribed DVT prophylaxis, the public will be able to see your data.

The Next Wave of Physician Pay for Performance

As the name implies, PQRS is a program based on reporting. Now CMS is adding the Value-Based Payment Modifier (VBPM) program, in which performance determines payments (see Table 1). It incorporates quality measures from PQRS, but is for now a separate program. It is very similar in name and structure to the hospital VBP program mentioned above, but incorporates cost of care data as well as quality performance. So it is really about value and not just quality performance (hence the name).

For providers in groups of more than 100 that bill under the same tax ID number (they don’t have to be in the same specialty), VBPM will first influence Part B Medicare reimbursement for physician services in 2015. It will expand to include all providers in 2017.

But don’t think you have until 2015 or 2017 to learn about all of this. There is a two-year lag, so payments in 2015 are based on performance in 2013 and 2017 payments presumably will be based on 2015 performance. In the fall of 2013, CMS plans to provide group-level (not individual) performance reports to all doctors in groups of 100 or more under the same tax ID number. These performance reports are known as quality resource use reports (QRURs). QRURs were trialed on physicians in a few states who received reports in 2012 based on 2011 performance, but in 2013, reports based on 2012 performance will be distributed to all doctors who practice in groups of 100 or more.

The calculation to determine whether a doctor is due additional payment for good performance (more accurately, good value) is awfully complicated. But providers have a choice to make. They can choose to:

- Not report data and accept a 1% penalty (likely to increase in successive years and in addition to the penalty for not reporting PQRS data, for a total penalty of 2.5%);

- Report data but not compete for financial upside or downside; or

- Compete for additional payments (amount to be determined) and risk a penalty of 0.5% or 1% for poor performance.

Look for more details about the VBPM program in future columns and other articles in The Hospitalist. There are a number of good online resources, including a CMS presentation titled “CMS Proposals for the Physician Value-Based Payment Modifier under the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.” Type “Value-Based Payment Modifier” and “CMS” into any search engine to locate the video.

Parting Recommendations

Just about every hospitalist group should:

- Designate someone in your group to keep up with evolving pay-for-performance programs. It doesn’t have to be an MD, but you do need someone local that can guide your group through it. Consider becoming the most expert physician at your hospital on this topic.

- Start reporting through PQRS in 2013 if you haven’t already.

- Support SHM’s efforts to provide feedback to CMS to ensure that the metrics are meaningful for the type of care we provide.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is co-founder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Author’s note: For helping to explain all this pay-for-performance stuff, I once again owe thanks to Dr. Pat Torcson, a hospitalist in Covington, La., and member of SHM’s Public Policy Committee. He does an amazing job of keeping up with the evolving pay-for-performance programs, advocating on behalf of hospitalists and the patients we serve, and graciously answers my tedious questions with thoughtful and informative replies. He is a really pleasant guy and a terrific asset to SHM and hospital medicine.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing Off-Label Drugs

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.