User login

Hospitalists Should Consider Fall Risks with Sleep Agent

An author of a new study associating the hypnotic zolpidem (Ambien) with higher rates of patient falls says hospitalists should keep the popular drug’s risks front of mind.

The retrospective cohort study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, “Zolpidem is Independently Associated with Increased Risk of Inpatient Falls,” found that the rate of falls increased nearly six times among patients taking the sleep agent. The research team at the Center for Sleep Medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, N.Y., calculated one additional fall for every 55 admitted patients who were administered the treatment.

“What this says to me is if one is going to use zolpidem, you have to be aware you’re increasing the risk of fall,” says sleep specialist Timothy Morgenthaler, MD, the Mayo Clinic’s chief patient officer. “Knowledgeable of that, one ought to consider whether there are alternatives or whether the risks outweigh the goal in that setting.”

Dr. Morgenthaler says zolpidem is the most commonly prescribed hypnotic at his hospital, and believes it to be the most common treatment in the U.S. He began studying the issue after nurses reported that it appeared patients were falling after taking the agent. In response to the study, Mayo Clinic removed zolpidem from many of its admission order sets and attempted to help improve patient sleep via other methods, including noise reduction.

“We haven’t removed it from our formulary, and I’m not saying it doesn’t have a role in some points,” he says, “but rather than encouraging it as an option in patients being admitted into the patient, we’re choosing instead now to encourage nonpharmacologic sleep enhancements.”

Visit our website for more information about HM’s approach to patient falls.

An author of a new study associating the hypnotic zolpidem (Ambien) with higher rates of patient falls says hospitalists should keep the popular drug’s risks front of mind.

The retrospective cohort study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, “Zolpidem is Independently Associated with Increased Risk of Inpatient Falls,” found that the rate of falls increased nearly six times among patients taking the sleep agent. The research team at the Center for Sleep Medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, N.Y., calculated one additional fall for every 55 admitted patients who were administered the treatment.

“What this says to me is if one is going to use zolpidem, you have to be aware you’re increasing the risk of fall,” says sleep specialist Timothy Morgenthaler, MD, the Mayo Clinic’s chief patient officer. “Knowledgeable of that, one ought to consider whether there are alternatives or whether the risks outweigh the goal in that setting.”

Dr. Morgenthaler says zolpidem is the most commonly prescribed hypnotic at his hospital, and believes it to be the most common treatment in the U.S. He began studying the issue after nurses reported that it appeared patients were falling after taking the agent. In response to the study, Mayo Clinic removed zolpidem from many of its admission order sets and attempted to help improve patient sleep via other methods, including noise reduction.

“We haven’t removed it from our formulary, and I’m not saying it doesn’t have a role in some points,” he says, “but rather than encouraging it as an option in patients being admitted into the patient, we’re choosing instead now to encourage nonpharmacologic sleep enhancements.”

Visit our website for more information about HM’s approach to patient falls.

An author of a new study associating the hypnotic zolpidem (Ambien) with higher rates of patient falls says hospitalists should keep the popular drug’s risks front of mind.

The retrospective cohort study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, “Zolpidem is Independently Associated with Increased Risk of Inpatient Falls,” found that the rate of falls increased nearly six times among patients taking the sleep agent. The research team at the Center for Sleep Medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, N.Y., calculated one additional fall for every 55 admitted patients who were administered the treatment.

“What this says to me is if one is going to use zolpidem, you have to be aware you’re increasing the risk of fall,” says sleep specialist Timothy Morgenthaler, MD, the Mayo Clinic’s chief patient officer. “Knowledgeable of that, one ought to consider whether there are alternatives or whether the risks outweigh the goal in that setting.”

Dr. Morgenthaler says zolpidem is the most commonly prescribed hypnotic at his hospital, and believes it to be the most common treatment in the U.S. He began studying the issue after nurses reported that it appeared patients were falling after taking the agent. In response to the study, Mayo Clinic removed zolpidem from many of its admission order sets and attempted to help improve patient sleep via other methods, including noise reduction.

“We haven’t removed it from our formulary, and I’m not saying it doesn’t have a role in some points,” he says, “but rather than encouraging it as an option in patients being admitted into the patient, we’re choosing instead now to encourage nonpharmacologic sleep enhancements.”

Visit our website for more information about HM’s approach to patient falls.

Performance Disconnect: Measures Don’t Improve Hospitals’ Readmissions Experience

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.

“The challenge is to find a way to connect the dots between the core measures and readmissions,” he says.

Learn more about the four "core" heart failure quality measures for hospitals by visiting the Resource Rooms on the SHM website, or check out this 80-page implementation guide, “Improving Heart Failure Care for Hospitalized Patients [PDF],” also available on SHM’s website.

Read The Hospitalist columnist Win Whitcomb’s take on readmissions penalty programs.

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.

“The challenge is to find a way to connect the dots between the core measures and readmissions,” he says.

Learn more about the four "core" heart failure quality measures for hospitals by visiting the Resource Rooms on the SHM website, or check out this 80-page implementation guide, “Improving Heart Failure Care for Hospitalized Patients [PDF],” also available on SHM’s website.

Read The Hospitalist columnist Win Whitcomb’s take on readmissions penalty programs.

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.

“The challenge is to find a way to connect the dots between the core measures and readmissions,” he says.

Learn more about the four "core" heart failure quality measures for hospitals by visiting the Resource Rooms on the SHM website, or check out this 80-page implementation guide, “Improving Heart Failure Care for Hospitalized Patients [PDF],” also available on SHM’s website.

Read The Hospitalist columnist Win Whitcomb’s take on readmissions penalty programs.

Avatrombopag reduces preprocedure platelet needs in chronic liver disease

BOSTON – Avatrombopag, an investigational thrombopoietin receptor agonist, may reduce procedure-related bleeding risk in patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia, results of a phase II trial suggest.

Patients randomized to receive avatrambopag (E5501) before invasive surgical or diagnostic procedures had significantly more platelet count responses and required significantly fewer platelet transfusions than did patients randomized to placebo, Dr. Norah Terrault said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

"It was a well-tolerated drug with no dose-limiting adverse events," Dr. Terrault said, although she noted that one patient had a nonfatal episode of portal-vein thrombosis that may have been related to the drug.

Avatrombopag has been shown to mimic the effects of thrombopoietin both in vitro and in vivo, and in a phase II study it was shown to increase platelet counts in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia.

Dr. Terrault, associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues tested the efficacy of short-course avatrombopag in 130 patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia prior to a planned invasive procedure. The patients were all adults with cirrhosis from viral hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or alcoholic liver disease.

The trial, labeled E5501-G000-202, enrolled patients into two cohorts. In cohort A, 67 patients were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or a loading dose of a first-generation formulation of avatrombopag 100 mg on day 1, followed by a maintenance dose on days 2-7 of either 20, 40, or 80 mg daily.

In cohort B, 63 patients were randomized either to placebo or to a second-generation formulation of avatrombopag at 80 mg on day 1, followed by either 10 mg daily for days 2-7 or 20 mg/day for days 2-4 and placebo on days 5, 6, and 7.

Patients in both cohorts were scheduled for procedures 1-4 days after the end of drug dosing.

The primary end point was a platelet count response – defined as a platelet count increase from baseline of at least 20 × 109/L and at least one count of greater than 50 × 109/L during days 4-8 from the start of treatment. In an intention-to-treat analysis, the proportion of patients achieving the primary end point was significantly higher in each cohort compared with controls.

In cohort A, the respective responses in the 20- and 80-mg groups were seen in 7 of 18 patients on the 20-mg dose (38.9%) and in 13 of 17 on the 80-mg dose (76.5%), compared with 1 of 16 (6.3%) controls (P less than .05 for both comparisons). There was no significant difference between patients given a placebo vs. a 40-mg dose, however.

In cohort B, 9 of 21 patients on the 10-mg dose (42.9%) had a platelet count response, as did 11 of 21 (52.4%) in the 20-mg group, compared with 2 of 21 on placebo (9.5%; P less than .05 for both comparisons).

The investigators also performed an exploratory analysis looking at platelet transfusion requirements for 58 of the patients in cohort B and found that 7 of 20 (35%) controls needed preprocedure platelets, compared with 1 of 19 (5.3%) each in the 10- and 20-mg avatrombopag groups (P less than .05).

In the combined cohorts, 78 of 93 (83.9%) patients assigned to the drug had treatment-emergent adverse events, compared with 28 of 37 (75.7%) assigned to placebo. There were 15 grade-3 or -4 adverse events among avatrombopag patients (16.1%), compared with 5 among controls (13.5%).

There were three severe treatment-related events, all in patients who received the active drug, and 16 serious treatment-related events among those taking avatrombopag, compared with four on placebo (17.2% vs. 10.8%).

One patient – a 55-year-old with a history of cardiovascular disease, Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis, and a MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score of 19 – died. The death was attributed to acute respiratory failure, cardiopulmonary arrest, and metabolic acidosis.

A 61-year-old man with Child-Pugh class C disease and a MELD score of 19 but no hepatocellular carcinoma had weight gain on study day 34, which was shown on Doppler ultrasound to be portal-vein thrombus. His peak platelet count was 199 × 109/L on day 17. He was successfully treated with embolization and anticoagulation therapy.

Investigators are currently planning phase III trials with avatrombopag, Dr. Terrault said.

The study was funded by Eisai, maker of avatrombopag. Dr. Terrault receives grant and research support from the company and serves in an advisory capacity.

BOSTON – Avatrombopag, an investigational thrombopoietin receptor agonist, may reduce procedure-related bleeding risk in patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia, results of a phase II trial suggest.

Patients randomized to receive avatrambopag (E5501) before invasive surgical or diagnostic procedures had significantly more platelet count responses and required significantly fewer platelet transfusions than did patients randomized to placebo, Dr. Norah Terrault said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

"It was a well-tolerated drug with no dose-limiting adverse events," Dr. Terrault said, although she noted that one patient had a nonfatal episode of portal-vein thrombosis that may have been related to the drug.

Avatrombopag has been shown to mimic the effects of thrombopoietin both in vitro and in vivo, and in a phase II study it was shown to increase platelet counts in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia.

Dr. Terrault, associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues tested the efficacy of short-course avatrombopag in 130 patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia prior to a planned invasive procedure. The patients were all adults with cirrhosis from viral hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or alcoholic liver disease.

The trial, labeled E5501-G000-202, enrolled patients into two cohorts. In cohort A, 67 patients were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or a loading dose of a first-generation formulation of avatrombopag 100 mg on day 1, followed by a maintenance dose on days 2-7 of either 20, 40, or 80 mg daily.

In cohort B, 63 patients were randomized either to placebo or to a second-generation formulation of avatrombopag at 80 mg on day 1, followed by either 10 mg daily for days 2-7 or 20 mg/day for days 2-4 and placebo on days 5, 6, and 7.

Patients in both cohorts were scheduled for procedures 1-4 days after the end of drug dosing.

The primary end point was a platelet count response – defined as a platelet count increase from baseline of at least 20 × 109/L and at least one count of greater than 50 × 109/L during days 4-8 from the start of treatment. In an intention-to-treat analysis, the proportion of patients achieving the primary end point was significantly higher in each cohort compared with controls.

In cohort A, the respective responses in the 20- and 80-mg groups were seen in 7 of 18 patients on the 20-mg dose (38.9%) and in 13 of 17 on the 80-mg dose (76.5%), compared with 1 of 16 (6.3%) controls (P less than .05 for both comparisons). There was no significant difference between patients given a placebo vs. a 40-mg dose, however.

In cohort B, 9 of 21 patients on the 10-mg dose (42.9%) had a platelet count response, as did 11 of 21 (52.4%) in the 20-mg group, compared with 2 of 21 on placebo (9.5%; P less than .05 for both comparisons).

The investigators also performed an exploratory analysis looking at platelet transfusion requirements for 58 of the patients in cohort B and found that 7 of 20 (35%) controls needed preprocedure platelets, compared with 1 of 19 (5.3%) each in the 10- and 20-mg avatrombopag groups (P less than .05).

In the combined cohorts, 78 of 93 (83.9%) patients assigned to the drug had treatment-emergent adverse events, compared with 28 of 37 (75.7%) assigned to placebo. There were 15 grade-3 or -4 adverse events among avatrombopag patients (16.1%), compared with 5 among controls (13.5%).

There were three severe treatment-related events, all in patients who received the active drug, and 16 serious treatment-related events among those taking avatrombopag, compared with four on placebo (17.2% vs. 10.8%).

One patient – a 55-year-old with a history of cardiovascular disease, Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis, and a MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score of 19 – died. The death was attributed to acute respiratory failure, cardiopulmonary arrest, and metabolic acidosis.

A 61-year-old man with Child-Pugh class C disease and a MELD score of 19 but no hepatocellular carcinoma had weight gain on study day 34, which was shown on Doppler ultrasound to be portal-vein thrombus. His peak platelet count was 199 × 109/L on day 17. He was successfully treated with embolization and anticoagulation therapy.

Investigators are currently planning phase III trials with avatrombopag, Dr. Terrault said.

The study was funded by Eisai, maker of avatrombopag. Dr. Terrault receives grant and research support from the company and serves in an advisory capacity.

BOSTON – Avatrombopag, an investigational thrombopoietin receptor agonist, may reduce procedure-related bleeding risk in patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia, results of a phase II trial suggest.

Patients randomized to receive avatrambopag (E5501) before invasive surgical or diagnostic procedures had significantly more platelet count responses and required significantly fewer platelet transfusions than did patients randomized to placebo, Dr. Norah Terrault said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

"It was a well-tolerated drug with no dose-limiting adverse events," Dr. Terrault said, although she noted that one patient had a nonfatal episode of portal-vein thrombosis that may have been related to the drug.

Avatrombopag has been shown to mimic the effects of thrombopoietin both in vitro and in vivo, and in a phase II study it was shown to increase platelet counts in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia.

Dr. Terrault, associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues tested the efficacy of short-course avatrombopag in 130 patients with chronic liver disease and thrombocytopenia prior to a planned invasive procedure. The patients were all adults with cirrhosis from viral hepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or alcoholic liver disease.

The trial, labeled E5501-G000-202, enrolled patients into two cohorts. In cohort A, 67 patients were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or a loading dose of a first-generation formulation of avatrombopag 100 mg on day 1, followed by a maintenance dose on days 2-7 of either 20, 40, or 80 mg daily.

In cohort B, 63 patients were randomized either to placebo or to a second-generation formulation of avatrombopag at 80 mg on day 1, followed by either 10 mg daily for days 2-7 or 20 mg/day for days 2-4 and placebo on days 5, 6, and 7.

Patients in both cohorts were scheduled for procedures 1-4 days after the end of drug dosing.

The primary end point was a platelet count response – defined as a platelet count increase from baseline of at least 20 × 109/L and at least one count of greater than 50 × 109/L during days 4-8 from the start of treatment. In an intention-to-treat analysis, the proportion of patients achieving the primary end point was significantly higher in each cohort compared with controls.

In cohort A, the respective responses in the 20- and 80-mg groups were seen in 7 of 18 patients on the 20-mg dose (38.9%) and in 13 of 17 on the 80-mg dose (76.5%), compared with 1 of 16 (6.3%) controls (P less than .05 for both comparisons). There was no significant difference between patients given a placebo vs. a 40-mg dose, however.

In cohort B, 9 of 21 patients on the 10-mg dose (42.9%) had a platelet count response, as did 11 of 21 (52.4%) in the 20-mg group, compared with 2 of 21 on placebo (9.5%; P less than .05 for both comparisons).

The investigators also performed an exploratory analysis looking at platelet transfusion requirements for 58 of the patients in cohort B and found that 7 of 20 (35%) controls needed preprocedure platelets, compared with 1 of 19 (5.3%) each in the 10- and 20-mg avatrombopag groups (P less than .05).

In the combined cohorts, 78 of 93 (83.9%) patients assigned to the drug had treatment-emergent adverse events, compared with 28 of 37 (75.7%) assigned to placebo. There were 15 grade-3 or -4 adverse events among avatrombopag patients (16.1%), compared with 5 among controls (13.5%).

There were three severe treatment-related events, all in patients who received the active drug, and 16 serious treatment-related events among those taking avatrombopag, compared with four on placebo (17.2% vs. 10.8%).

One patient – a 55-year-old with a history of cardiovascular disease, Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis, and a MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score of 19 – died. The death was attributed to acute respiratory failure, cardiopulmonary arrest, and metabolic acidosis.

A 61-year-old man with Child-Pugh class C disease and a MELD score of 19 but no hepatocellular carcinoma had weight gain on study day 34, which was shown on Doppler ultrasound to be portal-vein thrombus. His peak platelet count was 199 × 109/L on day 17. He was successfully treated with embolization and anticoagulation therapy.

Investigators are currently planning phase III trials with avatrombopag, Dr. Terrault said.

The study was funded by Eisai, maker of avatrombopag. Dr. Terrault receives grant and research support from the company and serves in an advisory capacity.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF LIVER DISEASES

Major Finding: In a study cohort with a second-generation formulation of avatrombopag, 9 of 21 patients on a 10-mg daily dose (42.9%) had a platelet count response, as did 11 of 21 (52.4%) in the 20-mg group, compared with 2 of 21 on placebo (9.5%; P less than .05 for both comparisons).

Data Source: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Eisai, maker of avatrombopag. Dr. Terrault receives grant and research support from the company and serves in an advisory capacity.

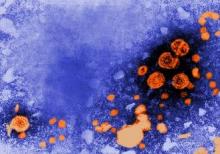

Tenofovir alone suffices against lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B

BOSTON – In patients who had chronic hepatitis B infections and documented lamivudine resistance, tenofovir with or without emtricitabine produced high rates of viral suppression with no detectable resistance over 2 years.

In a phase IIIb randomized study, 89% of lamivudine-resistant patients with HBV who were randomly assigned to receive tenofovir (Viread) alone met the primary end point of HBV DNA below 400 copies/mL, compared with 86% of those assigned to a tenofovir/emtricitabine (Emtriva) combination, in an intention-to-treat analysis, Dr. Scott Fung, assistant professor of hepatology at the University of Toronto, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

"Tenofovir monotherapy was just as safe and effective as combination therapy, suggesting that monotherapy alone was sufficient for treatment of hepatitis B," Dr. Fung said.

In addition to the high rate of viral resistance, tenofovir was associated with normalization of ALT levels in a majority of patients, and with no emergent viral resistance, he said.

The investigators enrolled 280 patients who carried virus with lamivudine-resistant mutations, were viremic (HBV DNA greater than 103/IU per mL), and were still on lamivudine until the day of randomization. Current or prior treatment with adefovir (Hepsera) was allowed as long as the patient had received less than 48 total weeks of therapy.

A total of 133 patients who were assigned to receive tenofovir 300 mg daily completed 96 weeks of treatment and were thus available for analysis, as were 125 of those assigned to emtricitabine/tenofovir in a fixed-dose combination.

As noted before, the rates of HBV DNA below 400 copies/mL were 89% for the monotherapy arm and 86% for the combination in an analysis that considered missing data as treatment failure. When missing data were excluded from an on-treatment analysis, however, the respective rates were 96% and 95%.

Using a lower cutoff point, less than 169 copies/mL, the respective rates at 96 weeks were 86% and 84%.

In all, 70% of patients in each group had normal ALT levels at 96 weeks, and among patients with abnormally high levels at baseline nearly two-thirds in each group had normalization of ALT during the study.

The HBV e-antigen loss rate was modest, at 15% of patients on tenofovir alone and 13% on the combination. HBeAg seroconversion occurred in 11% and 10%, respectively.

Among 18 patients who qualified for genotypic resistance testing at their last on-treatment visit, there were no viral isolates demonstrating tenofovir resistance, Dr. Fung said.

There were three deaths during the study: one from gastrointestinal hemorrhage in a patient in the monotherapy group and two – one from cardiac arrest and sepsis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma and one from bronchopneumonia – in the combination group. The deaths were judged to be unrelated to study treatment.

There was only one serious treatment-related adverse event, occurring in the combination group (the event was unspecified), and only three patients discontinued because of adverse events – one in the monotherapy arm and two in the combination group. Five patients on tenofovir alone and four on the combination had creatinine clearance less than 50 mL/min at study end; these patients all had low baseline creatinine clearance levels, ranging from 41 to 69 mL/min, Dr. Fung noted.

The authors also looked at bone mineral density levels at baseline and at study end in 239 patients for who dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry data were available. At baseline, 33% of patients were determined to have osteopenia and 7% to have osteoporosis on spine scans and 22% and 1.3%, respectively, on hip scans. Repeat scans at 96 weeks showed that the majority of patients had a reduction in bone mineral density of about 22%, a decline that was considered not clinically significant, he said.

The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Dr. Fung disclosed receiving grant/research support and speaking/teaching fees from the company.

BOSTON – In patients who had chronic hepatitis B infections and documented lamivudine resistance, tenofovir with or without emtricitabine produced high rates of viral suppression with no detectable resistance over 2 years.

In a phase IIIb randomized study, 89% of lamivudine-resistant patients with HBV who were randomly assigned to receive tenofovir (Viread) alone met the primary end point of HBV DNA below 400 copies/mL, compared with 86% of those assigned to a tenofovir/emtricitabine (Emtriva) combination, in an intention-to-treat analysis, Dr. Scott Fung, assistant professor of hepatology at the University of Toronto, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

"Tenofovir monotherapy was just as safe and effective as combination therapy, suggesting that monotherapy alone was sufficient for treatment of hepatitis B," Dr. Fung said.

In addition to the high rate of viral resistance, tenofovir was associated with normalization of ALT levels in a majority of patients, and with no emergent viral resistance, he said.

The investigators enrolled 280 patients who carried virus with lamivudine-resistant mutations, were viremic (HBV DNA greater than 103/IU per mL), and were still on lamivudine until the day of randomization. Current or prior treatment with adefovir (Hepsera) was allowed as long as the patient had received less than 48 total weeks of therapy.

A total of 133 patients who were assigned to receive tenofovir 300 mg daily completed 96 weeks of treatment and were thus available for analysis, as were 125 of those assigned to emtricitabine/tenofovir in a fixed-dose combination.

As noted before, the rates of HBV DNA below 400 copies/mL were 89% for the monotherapy arm and 86% for the combination in an analysis that considered missing data as treatment failure. When missing data were excluded from an on-treatment analysis, however, the respective rates were 96% and 95%.

Using a lower cutoff point, less than 169 copies/mL, the respective rates at 96 weeks were 86% and 84%.

In all, 70% of patients in each group had normal ALT levels at 96 weeks, and among patients with abnormally high levels at baseline nearly two-thirds in each group had normalization of ALT during the study.

The HBV e-antigen loss rate was modest, at 15% of patients on tenofovir alone and 13% on the combination. HBeAg seroconversion occurred in 11% and 10%, respectively.

Among 18 patients who qualified for genotypic resistance testing at their last on-treatment visit, there were no viral isolates demonstrating tenofovir resistance, Dr. Fung said.

There were three deaths during the study: one from gastrointestinal hemorrhage in a patient in the monotherapy group and two – one from cardiac arrest and sepsis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma and one from bronchopneumonia – in the combination group. The deaths were judged to be unrelated to study treatment.

There was only one serious treatment-related adverse event, occurring in the combination group (the event was unspecified), and only three patients discontinued because of adverse events – one in the monotherapy arm and two in the combination group. Five patients on tenofovir alone and four on the combination had creatinine clearance less than 50 mL/min at study end; these patients all had low baseline creatinine clearance levels, ranging from 41 to 69 mL/min, Dr. Fung noted.

The authors also looked at bone mineral density levels at baseline and at study end in 239 patients for who dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry data were available. At baseline, 33% of patients were determined to have osteopenia and 7% to have osteoporosis on spine scans and 22% and 1.3%, respectively, on hip scans. Repeat scans at 96 weeks showed that the majority of patients had a reduction in bone mineral density of about 22%, a decline that was considered not clinically significant, he said.

The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Dr. Fung disclosed receiving grant/research support and speaking/teaching fees from the company.

BOSTON – In patients who had chronic hepatitis B infections and documented lamivudine resistance, tenofovir with or without emtricitabine produced high rates of viral suppression with no detectable resistance over 2 years.

In a phase IIIb randomized study, 89% of lamivudine-resistant patients with HBV who were randomly assigned to receive tenofovir (Viread) alone met the primary end point of HBV DNA below 400 copies/mL, compared with 86% of those assigned to a tenofovir/emtricitabine (Emtriva) combination, in an intention-to-treat analysis, Dr. Scott Fung, assistant professor of hepatology at the University of Toronto, reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

"Tenofovir monotherapy was just as safe and effective as combination therapy, suggesting that monotherapy alone was sufficient for treatment of hepatitis B," Dr. Fung said.

In addition to the high rate of viral resistance, tenofovir was associated with normalization of ALT levels in a majority of patients, and with no emergent viral resistance, he said.

The investigators enrolled 280 patients who carried virus with lamivudine-resistant mutations, were viremic (HBV DNA greater than 103/IU per mL), and were still on lamivudine until the day of randomization. Current or prior treatment with adefovir (Hepsera) was allowed as long as the patient had received less than 48 total weeks of therapy.

A total of 133 patients who were assigned to receive tenofovir 300 mg daily completed 96 weeks of treatment and were thus available for analysis, as were 125 of those assigned to emtricitabine/tenofovir in a fixed-dose combination.

As noted before, the rates of HBV DNA below 400 copies/mL were 89% for the monotherapy arm and 86% for the combination in an analysis that considered missing data as treatment failure. When missing data were excluded from an on-treatment analysis, however, the respective rates were 96% and 95%.

Using a lower cutoff point, less than 169 copies/mL, the respective rates at 96 weeks were 86% and 84%.

In all, 70% of patients in each group had normal ALT levels at 96 weeks, and among patients with abnormally high levels at baseline nearly two-thirds in each group had normalization of ALT during the study.

The HBV e-antigen loss rate was modest, at 15% of patients on tenofovir alone and 13% on the combination. HBeAg seroconversion occurred in 11% and 10%, respectively.

Among 18 patients who qualified for genotypic resistance testing at their last on-treatment visit, there were no viral isolates demonstrating tenofovir resistance, Dr. Fung said.

There were three deaths during the study: one from gastrointestinal hemorrhage in a patient in the monotherapy group and two – one from cardiac arrest and sepsis in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma and one from bronchopneumonia – in the combination group. The deaths were judged to be unrelated to study treatment.

There was only one serious treatment-related adverse event, occurring in the combination group (the event was unspecified), and only three patients discontinued because of adverse events – one in the monotherapy arm and two in the combination group. Five patients on tenofovir alone and four on the combination had creatinine clearance less than 50 mL/min at study end; these patients all had low baseline creatinine clearance levels, ranging from 41 to 69 mL/min, Dr. Fung noted.

The authors also looked at bone mineral density levels at baseline and at study end in 239 patients for who dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry data were available. At baseline, 33% of patients were determined to have osteopenia and 7% to have osteoporosis on spine scans and 22% and 1.3%, respectively, on hip scans. Repeat scans at 96 weeks showed that the majority of patients had a reduction in bone mineral density of about 22%, a decline that was considered not clinically significant, he said.

The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Dr. Fung disclosed receiving grant/research support and speaking/teaching fees from the company.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF LIVER DISEASES

Major Finding: In a phase IIIb randomized study, 89% of lamivudine-resistant patients with HBV who received tenofovir alone met the primary end point of HBV DNA below 400 copies/mL, compared with 86% of those given a tenofovir/emtricitabine combination.

Data Source: A randomized, double-blind phase IIIb study

Disclosures: The study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Dr. Fung disclosed receiving grant/research support and speaking/teaching fees from the company.

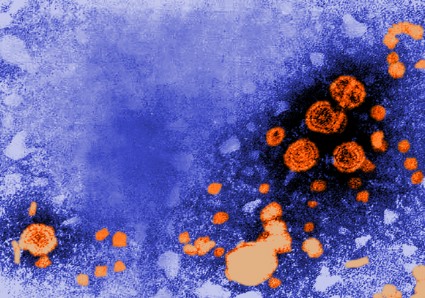

HCV coinfections can be safely treated in patients with HIV

BOSTON – Patients with HIV and hepatitis C coinfection had high levels of sustained viral response with regimens combining select antiretroviral agents with telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin, said investigators at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

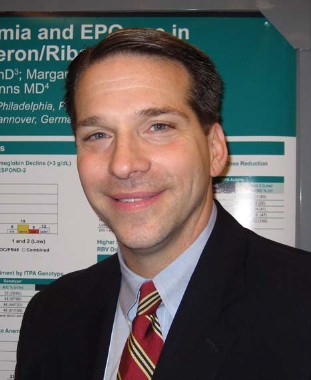

The key to avoiding adverse drug interactions between telaprevir (Incivek) and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens is careful selection of HIV therapy, said Dr. Mark Sulkowski, medical director of the viral hepatitis center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Dr. Sulkowski and his colleagues showed in a randomized phase III study that a combination of specific antiretroviral agents with telaprevir and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) was associated with a 74% SVR24 rate, compared with HAART and PEG-IFN only.

"Overall, 74% of patients treated with telaprevir in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin achieved SVR [sustained virological response], compared to 45% of those treated with placebo. Drug interactions with telaprevir and selected antiretroviral therapies, specifically atazanavir/ritonavir and efavirenz, were not clinically meaningful," Dr. Sulkowski said.

A separate study by European investigators showed that the likelihood that patients with HIV/HCV coinfection will clear HCV from serum may depend on the presence of ribavirin in a regimen, and on HCV genotype.

"Ribavirin is important in the management of acute hepatitis C in HIV-positive patients. Almost all patients with genotype 2 and 3 infections were able to clear virus with combination therapy [PEG-IFN and RBV]," said lead investigator Dr. Christoph Boesecke of the University of Bonn, Germany.

Safety Concerns

Some infectious disease specialists have expressed concern that the addition of a direct-acting antiviral agent in combination with PEG-IFN/RBV could compromise the efficacy and/or safety of a HAART regimen.

To test the HAART/direct-acting antiviral agent combination, Dr. Sulkowski and his colleagues enrolled patients with HIV/HCV coinfection in a two-part study. In part A, patients were assigned on a 1:1 ratio to receive either telaprevir or placebo, each with PEG-IFN/RBV.

In part B, patients on a HAART regimen (either a combination of efavirenz, tenofovir, and emtricitabine or ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, tenofovir, and emtricitabine or lamivudine) were assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive telaprevir or placebo plus PEG-IFN/RBV. All patients were treated for 48 weeks, with an additional 24 weeks of follow-up.

HCV RNA levels on study were measured at various time points, and the investigators looked for drug interactions, adverse events, viral breakthrough, and other clinical measures.

At 24 weeks post treatment, the HCV sustained virologic response rate (SVR24) among patients treated with telaprevir and PEG-IFN/RBV but not an antiretroviral therapy was 71%, compared with 33% among those treated with placebo and PEG-IFN/RBV.

Among patients on the HAART regimen containing efavirenz plus telaprevir and PEG-IFN/RBV, 69% had an SVR24, compared with 38% of those who received the same HAART regimen without telaprevir. Among those on the atazanavir-containing regimen, 73% had an SVR24, compared with 50% of controls who received only PEG-IFN/RBV plus HAART.

The serum concentrations of both atazanavir and efavirenz were similar whether the patients had received telaprevir or not, and there were no cases of HIV viral breakthrough, although CD4 cell counts decreased among patients taking PEG-IFN/RBV and either telaprevir or placebo. Nonetheless, investigators did not see HIV-related adverse events, Dr. Sulkowski said.

Patients on efavirenz did require a telaprevir dose increase, but the required increase was adequate for maintaining exposure to the direct-acting antiviral agent, he added.

Genotype Matters

Dr. Boesecke and his colleagues in the European AIDS Treatment Network looked at the effect of HCV genotype and ribavirin on SVR rates in the treatment of coinfected patients. They reported on 303 HIV-infected men from the Austria, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom who had been diagnosed with acute HCV infections. Of this group, 273 were treated with PEG-IFN/RBV, and 30 were treated with PEG-IFN alone. In all, 88% of the patients who received ribavirin had weight-based doses (1,000 mg for those 75 kg and under, and 1,200 mg for those over 75 kg).

A majority of the patients (69%) were infected with genotype 1; 4% had genotype 2; 11% had genotype 3; and 16% had genotype 4 infections. About one-third of patients had 24 weeks of therapy, and the remaining third had 48 weeks. Median time from HCV diagnosis to the start of treatment was about 10 weeks.

Among all patients, 52% of those received PEG-IFN alone, and 52% of those who also received ribavirin had a rapid virologic response (RVR), defined as HCV RNA negative at 4 weeks. Respective SVR24 rates were 66.7% and 69.6%.

When the investigators broke it out by genotype, however, they found that while the addition of ribavirin did not significantly change either RVR or SVR24 rates among patients with genotype 1 or 3 infections, 60% of patients with genotype 2 or 3 infections on PEG-IFN monotherapy had a 60% SVR24,, whereas those on PEG-IFN/RBV had a 94% SVR24. indicating a significant benefit to adding RBV (P = .016). The RVR rates were not significantly different in these patients, however.

There were no significant differences in either the total number or severity of adverse events among the various genotypes. In 10% of all cases a ribavirin dose reduction was required, and interferon dose reductions were required in 6% of cases.

Toxicities required stopping HCV therapy in 17 patients (6%).

"We saw high sustained virologic response rates if you treat hepatitis C early on, when it’s still acute, compared to when the disease is left to a chronic course in HIV patients," said Dr. Boesecke

Dr. Sulkowski’s study was supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He is a consultant to the company and has received grant and research support from it. Dr. Boesecke’s study was supported by the European AIDS Treatment Network. He reported no conflict of interest.

BOSTON – Patients with HIV and hepatitis C coinfection had high levels of sustained viral response with regimens combining select antiretroviral agents with telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin, said investigators at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

The key to avoiding adverse drug interactions between telaprevir (Incivek) and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens is careful selection of HIV therapy, said Dr. Mark Sulkowski, medical director of the viral hepatitis center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Dr. Sulkowski and his colleagues showed in a randomized phase III study that a combination of specific antiretroviral agents with telaprevir and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) was associated with a 74% SVR24 rate, compared with HAART and PEG-IFN only.

"Overall, 74% of patients treated with telaprevir in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin achieved SVR [sustained virological response], compared to 45% of those treated with placebo. Drug interactions with telaprevir and selected antiretroviral therapies, specifically atazanavir/ritonavir and efavirenz, were not clinically meaningful," Dr. Sulkowski said.

A separate study by European investigators showed that the likelihood that patients with HIV/HCV coinfection will clear HCV from serum may depend on the presence of ribavirin in a regimen, and on HCV genotype.

"Ribavirin is important in the management of acute hepatitis C in HIV-positive patients. Almost all patients with genotype 2 and 3 infections were able to clear virus with combination therapy [PEG-IFN and RBV]," said lead investigator Dr. Christoph Boesecke of the University of Bonn, Germany.

Safety Concerns

Some infectious disease specialists have expressed concern that the addition of a direct-acting antiviral agent in combination with PEG-IFN/RBV could compromise the efficacy and/or safety of a HAART regimen.

To test the HAART/direct-acting antiviral agent combination, Dr. Sulkowski and his colleagues enrolled patients with HIV/HCV coinfection in a two-part study. In part A, patients were assigned on a 1:1 ratio to receive either telaprevir or placebo, each with PEG-IFN/RBV.

In part B, patients on a HAART regimen (either a combination of efavirenz, tenofovir, and emtricitabine or ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, tenofovir, and emtricitabine or lamivudine) were assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive telaprevir or placebo plus PEG-IFN/RBV. All patients were treated for 48 weeks, with an additional 24 weeks of follow-up.

HCV RNA levels on study were measured at various time points, and the investigators looked for drug interactions, adverse events, viral breakthrough, and other clinical measures.

At 24 weeks post treatment, the HCV sustained virologic response rate (SVR24) among patients treated with telaprevir and PEG-IFN/RBV but not an antiretroviral therapy was 71%, compared with 33% among those treated with placebo and PEG-IFN/RBV.

Among patients on the HAART regimen containing efavirenz plus telaprevir and PEG-IFN/RBV, 69% had an SVR24, compared with 38% of those who received the same HAART regimen without telaprevir. Among those on the atazanavir-containing regimen, 73% had an SVR24, compared with 50% of controls who received only PEG-IFN/RBV plus HAART.

The serum concentrations of both atazanavir and efavirenz were similar whether the patients had received telaprevir or not, and there were no cases of HIV viral breakthrough, although CD4 cell counts decreased among patients taking PEG-IFN/RBV and either telaprevir or placebo. Nonetheless, investigators did not see HIV-related adverse events, Dr. Sulkowski said.

Patients on efavirenz did require a telaprevir dose increase, but the required increase was adequate for maintaining exposure to the direct-acting antiviral agent, he added.

Genotype Matters

Dr. Boesecke and his colleagues in the European AIDS Treatment Network looked at the effect of HCV genotype and ribavirin on SVR rates in the treatment of coinfected patients. They reported on 303 HIV-infected men from the Austria, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom who had been diagnosed with acute HCV infections. Of this group, 273 were treated with PEG-IFN/RBV, and 30 were treated with PEG-IFN alone. In all, 88% of the patients who received ribavirin had weight-based doses (1,000 mg for those 75 kg and under, and 1,200 mg for those over 75 kg).

A majority of the patients (69%) were infected with genotype 1; 4% had genotype 2; 11% had genotype 3; and 16% had genotype 4 infections. About one-third of patients had 24 weeks of therapy, and the remaining third had 48 weeks. Median time from HCV diagnosis to the start of treatment was about 10 weeks.

Among all patients, 52% of those received PEG-IFN alone, and 52% of those who also received ribavirin had a rapid virologic response (RVR), defined as HCV RNA negative at 4 weeks. Respective SVR24 rates were 66.7% and 69.6%.

When the investigators broke it out by genotype, however, they found that while the addition of ribavirin did not significantly change either RVR or SVR24 rates among patients with genotype 1 or 3 infections, 60% of patients with genotype 2 or 3 infections on PEG-IFN monotherapy had a 60% SVR24,, whereas those on PEG-IFN/RBV had a 94% SVR24. indicating a significant benefit to adding RBV (P = .016). The RVR rates were not significantly different in these patients, however.

There were no significant differences in either the total number or severity of adverse events among the various genotypes. In 10% of all cases a ribavirin dose reduction was required, and interferon dose reductions were required in 6% of cases.

Toxicities required stopping HCV therapy in 17 patients (6%).

"We saw high sustained virologic response rates if you treat hepatitis C early on, when it’s still acute, compared to when the disease is left to a chronic course in HIV patients," said Dr. Boesecke

Dr. Sulkowski’s study was supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He is a consultant to the company and has received grant and research support from it. Dr. Boesecke’s study was supported by the European AIDS Treatment Network. He reported no conflict of interest.

BOSTON – Patients with HIV and hepatitis C coinfection had high levels of sustained viral response with regimens combining select antiretroviral agents with telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin, said investigators at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

The key to avoiding adverse drug interactions between telaprevir (Incivek) and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimens is careful selection of HIV therapy, said Dr. Mark Sulkowski, medical director of the viral hepatitis center at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

Dr. Sulkowski and his colleagues showed in a randomized phase III study that a combination of specific antiretroviral agents with telaprevir and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) was associated with a 74% SVR24 rate, compared with HAART and PEG-IFN only.

"Overall, 74% of patients treated with telaprevir in combination with peg-interferon and ribavirin achieved SVR [sustained virological response], compared to 45% of those treated with placebo. Drug interactions with telaprevir and selected antiretroviral therapies, specifically atazanavir/ritonavir and efavirenz, were not clinically meaningful," Dr. Sulkowski said.

A separate study by European investigators showed that the likelihood that patients with HIV/HCV coinfection will clear HCV from serum may depend on the presence of ribavirin in a regimen, and on HCV genotype.

"Ribavirin is important in the management of acute hepatitis C in HIV-positive patients. Almost all patients with genotype 2 and 3 infections were able to clear virus with combination therapy [PEG-IFN and RBV]," said lead investigator Dr. Christoph Boesecke of the University of Bonn, Germany.

Safety Concerns

Some infectious disease specialists have expressed concern that the addition of a direct-acting antiviral agent in combination with PEG-IFN/RBV could compromise the efficacy and/or safety of a HAART regimen.

To test the HAART/direct-acting antiviral agent combination, Dr. Sulkowski and his colleagues enrolled patients with HIV/HCV coinfection in a two-part study. In part A, patients were assigned on a 1:1 ratio to receive either telaprevir or placebo, each with PEG-IFN/RBV.

In part B, patients on a HAART regimen (either a combination of efavirenz, tenofovir, and emtricitabine or ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, tenofovir, and emtricitabine or lamivudine) were assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive telaprevir or placebo plus PEG-IFN/RBV. All patients were treated for 48 weeks, with an additional 24 weeks of follow-up.

HCV RNA levels on study were measured at various time points, and the investigators looked for drug interactions, adverse events, viral breakthrough, and other clinical measures.

At 24 weeks post treatment, the HCV sustained virologic response rate (SVR24) among patients treated with telaprevir and PEG-IFN/RBV but not an antiretroviral therapy was 71%, compared with 33% among those treated with placebo and PEG-IFN/RBV.

Among patients on the HAART regimen containing efavirenz plus telaprevir and PEG-IFN/RBV, 69% had an SVR24, compared with 38% of those who received the same HAART regimen without telaprevir. Among those on the atazanavir-containing regimen, 73% had an SVR24, compared with 50% of controls who received only PEG-IFN/RBV plus HAART.

The serum concentrations of both atazanavir and efavirenz were similar whether the patients had received telaprevir or not, and there were no cases of HIV viral breakthrough, although CD4 cell counts decreased among patients taking PEG-IFN/RBV and either telaprevir or placebo. Nonetheless, investigators did not see HIV-related adverse events, Dr. Sulkowski said.

Patients on efavirenz did require a telaprevir dose increase, but the required increase was adequate for maintaining exposure to the direct-acting antiviral agent, he added.

Genotype Matters

Dr. Boesecke and his colleagues in the European AIDS Treatment Network looked at the effect of HCV genotype and ribavirin on SVR rates in the treatment of coinfected patients. They reported on 303 HIV-infected men from the Austria, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom who had been diagnosed with acute HCV infections. Of this group, 273 were treated with PEG-IFN/RBV, and 30 were treated with PEG-IFN alone. In all, 88% of the patients who received ribavirin had weight-based doses (1,000 mg for those 75 kg and under, and 1,200 mg for those over 75 kg).

A majority of the patients (69%) were infected with genotype 1; 4% had genotype 2; 11% had genotype 3; and 16% had genotype 4 infections. About one-third of patients had 24 weeks of therapy, and the remaining third had 48 weeks. Median time from HCV diagnosis to the start of treatment was about 10 weeks.

Among all patients, 52% of those received PEG-IFN alone, and 52% of those who also received ribavirin had a rapid virologic response (RVR), defined as HCV RNA negative at 4 weeks. Respective SVR24 rates were 66.7% and 69.6%.

When the investigators broke it out by genotype, however, they found that while the addition of ribavirin did not significantly change either RVR or SVR24 rates among patients with genotype 1 or 3 infections, 60% of patients with genotype 2 or 3 infections on PEG-IFN monotherapy had a 60% SVR24,, whereas those on PEG-IFN/RBV had a 94% SVR24. indicating a significant benefit to adding RBV (P = .016). The RVR rates were not significantly different in these patients, however.

There were no significant differences in either the total number or severity of adverse events among the various genotypes. In 10% of all cases a ribavirin dose reduction was required, and interferon dose reductions were required in 6% of cases.

Toxicities required stopping HCV therapy in 17 patients (6%).

"We saw high sustained virologic response rates if you treat hepatitis C early on, when it’s still acute, compared to when the disease is left to a chronic course in HIV patients," said Dr. Boesecke

Dr. Sulkowski’s study was supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He is a consultant to the company and has received grant and research support from it. Dr. Boesecke’s study was supported by the European AIDS Treatment Network. He reported no conflict of interest.

AT THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF LIVER DISEASES

Major Finding: Among patients with HIV and hepatitis C coinfection, 74% of those treated with telaprevir in combination with pegylated interferon and ribavirin achieved a sustained virologic response, compared with 45% of those treated with placebo and peg-interferon.

Data Source: Randomized placebo-controlled trial and prospective cohort study

Disclosures: Dr. Sulkowski’s study was supported by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He is a consultant to the company and has received grant and research support from it. Dr. Boesecke’s study was supported by the European AIDS Treatment Network. He reported no conflict of interest.

Triple therapy has poor safety in cirrhotic hepatitis C

BOSTON – In patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infections and compensated cirrhosis, a combination of a direct-acting antiviral agent, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin produced high on-treatment virologic response rates, but at the cost of significantly increased toxicities in an interim analysis of a French multicenter trial looking at the safety of the regimen.

Although the efficacy of direct-acting antiviral regimens involving the protease inhibitors telaprevir (Incivek) and boceprevir (Victrelis) combined with pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b in combination with ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RBV) in cirrhotic nonresponders to prior therapy was good , their safety was "poor," according to Dr. Christophe Hézode of the Hôpital Henri Mondor in Créteil, France.

Virologic response at 16 weeks in a per-protocol analysis was associated with a virologic response rate of 92% with telaprevir and 77% with boceprevir.

However, there were increased rates of serious adverse events and more difficult-to-manage anemia than in phase III trials for telaprevir and boceprevir, which included only a few patients with cirrhosis, Dr. Hézode said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

In treatment-experienced cirrhotic patients with platelet counts of 100,000/mm3 or serum albumin levels below 35 g/L, clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits of such regimens, with patients treated on a case-by-case basis because of the high risk for severe complications, Dr. Hézode said.

"However, cirrhotic experienced patients without predictors of severe complications clearly should be treated, but cautiously and carefully monitored," he added.

Dr. Hézode and his coinvestigators in the French Cohort of Therapeutic Failure and Resistances in Patients Treated With a Protease Inhibitor (telaprevir or boceprevir), Pegylated Interferon, and Ribavirin (CUPIC) trial studied two cohorts of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, and compensated cirrhosis (Child Pugh class A) who had either relapsed or had only a partial response to prior therapy, with partial response defined as at least a 2 log10 decline inV RNA but failure to clear virus by week 24.

He presented data on 497 patients who had completed 16 weeks of therapy on one of two regimens. In one cohort, 292 patients received 12 weeks of telaprevir 750 mg every 8 hours, and PEG-IFN alfa-2a (Pegasys) 180 mcg/wk with ribavirin 1,000-1,200 mg/day, followed by PEG-IFN/RBV through 48 weeks. In the second cohort, patients received a 4-week initiation phase with PEG-IFN alfa-2b (PegIntron) and ribavirin, followed by 44 weeks of boceprevir 800 mg every 8 hours, PEG-IFN 1.5 mcg/kg per wk, and ribavirin 800-1,400 mg/day.

At week 16, 45% of patients on telaprevir had had at least one serious adverse event, with 14.7% terminating therapy because of a serious side effect. In all, nearly one-fourth (22.6%) discontinued therapy, and there were five deaths: from septicemia, septic shock, pneumopathy, endocarditis, and bleeding esophageal varices. Other complications in this group included grade 3 or 4 infections in 6.5%, grade 3 or 4 hepatic decompensation in 2%, grade 3/4 asthenia in 5.5%, and renal failure in 1.7%.

Hematologic adverse events included anemia of grade 2 or greater in 30.4%, erythropoietin use in 53.8%, blood transfusion in 16.1%, and ribavirin dose reduction in 13%. In addition, 2.7% of patients had grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, and 1.7% had grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia.

In the boceprevir group, 32.7% had at least one serious adverse event, 26.3% discontinued prematurely, and 7.3% discontinued because of serious events. The cause of one death was described as pneumopathy. Grade 3/4 adverse events involved infections in 2.4%, hepatic decompensation in 2.9%, and asthenia in 5.8%. There were no cases of renal failure in this group.

Hematologic events in patients on boceprevir included grade 2 or greater anemia in 27.8%, erythropoietin use in 46.3%, blood transfusion in 6.3%, and ribavirin dose reduction in 10.7%.

Grade 3/4 neutropenia was seen in 4.4%, and grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia in 5.4%. Two patients (1%) in this cohort received thrombopoietin.

In a multivariate analysis, significant baseline predictors of severe complications (death, severe infection, and hepatic decompensation) included platelet counts of 100,000/mm3 or lower (odds ratio, 3.11; P = .0098) and a serum albumin level below 35 g/L (OR, 6.33; P less than .0001).

Baseline predictors for severe anemia (hemoglobin less than 8 g/dL) or blood transfusion included female gender (OR, 2.19; P = .023), no lead-in phase (OR, 2.25; P = .018), age 65 years or older (OR, 3.04; P = .0014), and hemoglobin 12 g/dL or lower for women and 13 g/dL or lower for men (OR, 5.30; P less than .0001),

The study was sponsored by ANRS, the French National Agency for Research in AIDS and Viral Hepatitis, with support from INSERM, the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research. Dr. Hézode said that he has no financial conflicts of interest, but disclosed serving as a speaker and adviser for Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Roche.

BOSTON – In patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infections and compensated cirrhosis, a combination of a direct-acting antiviral agent, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin produced high on-treatment virologic response rates, but at the cost of significantly increased toxicities in an interim analysis of a French multicenter trial looking at the safety of the regimen.

Although the efficacy of direct-acting antiviral regimens involving the protease inhibitors telaprevir (Incivek) and boceprevir (Victrelis) combined with pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b in combination with ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RBV) in cirrhotic nonresponders to prior therapy was good , their safety was "poor," according to Dr. Christophe Hézode of the Hôpital Henri Mondor in Créteil, France.

Virologic response at 16 weeks in a per-protocol analysis was associated with a virologic response rate of 92% with telaprevir and 77% with boceprevir.

However, there were increased rates of serious adverse events and more difficult-to-manage anemia than in phase III trials for telaprevir and boceprevir, which included only a few patients with cirrhosis, Dr. Hézode said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

In treatment-experienced cirrhotic patients with platelet counts of 100,000/mm3 or serum albumin levels below 35 g/L, clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits of such regimens, with patients treated on a case-by-case basis because of the high risk for severe complications, Dr. Hézode said.

"However, cirrhotic experienced patients without predictors of severe complications clearly should be treated, but cautiously and carefully monitored," he added.

Dr. Hézode and his coinvestigators in the French Cohort of Therapeutic Failure and Resistances in Patients Treated With a Protease Inhibitor (telaprevir or boceprevir), Pegylated Interferon, and Ribavirin (CUPIC) trial studied two cohorts of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, and compensated cirrhosis (Child Pugh class A) who had either relapsed or had only a partial response to prior therapy, with partial response defined as at least a 2 log10 decline inV RNA but failure to clear virus by week 24.

He presented data on 497 patients who had completed 16 weeks of therapy on one of two regimens. In one cohort, 292 patients received 12 weeks of telaprevir 750 mg every 8 hours, and PEG-IFN alfa-2a (Pegasys) 180 mcg/wk with ribavirin 1,000-1,200 mg/day, followed by PEG-IFN/RBV through 48 weeks. In the second cohort, patients received a 4-week initiation phase with PEG-IFN alfa-2b (PegIntron) and ribavirin, followed by 44 weeks of boceprevir 800 mg every 8 hours, PEG-IFN 1.5 mcg/kg per wk, and ribavirin 800-1,400 mg/day.

At week 16, 45% of patients on telaprevir had had at least one serious adverse event, with 14.7% terminating therapy because of a serious side effect. In all, nearly one-fourth (22.6%) discontinued therapy, and there were five deaths: from septicemia, septic shock, pneumopathy, endocarditis, and bleeding esophageal varices. Other complications in this group included grade 3 or 4 infections in 6.5%, grade 3 or 4 hepatic decompensation in 2%, grade 3/4 asthenia in 5.5%, and renal failure in 1.7%.

Hematologic adverse events included anemia of grade 2 or greater in 30.4%, erythropoietin use in 53.8%, blood transfusion in 16.1%, and ribavirin dose reduction in 13%. In addition, 2.7% of patients had grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, and 1.7% had grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia.

In the boceprevir group, 32.7% had at least one serious adverse event, 26.3% discontinued prematurely, and 7.3% discontinued because of serious events. The cause of one death was described as pneumopathy. Grade 3/4 adverse events involved infections in 2.4%, hepatic decompensation in 2.9%, and asthenia in 5.8%. There were no cases of renal failure in this group.

Hematologic events in patients on boceprevir included grade 2 or greater anemia in 27.8%, erythropoietin use in 46.3%, blood transfusion in 6.3%, and ribavirin dose reduction in 10.7%.

Grade 3/4 neutropenia was seen in 4.4%, and grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia in 5.4%. Two patients (1%) in this cohort received thrombopoietin.

In a multivariate analysis, significant baseline predictors of severe complications (death, severe infection, and hepatic decompensation) included platelet counts of 100,000/mm3 or lower (odds ratio, 3.11; P = .0098) and a serum albumin level below 35 g/L (OR, 6.33; P less than .0001).

Baseline predictors for severe anemia (hemoglobin less than 8 g/dL) or blood transfusion included female gender (OR, 2.19; P = .023), no lead-in phase (OR, 2.25; P = .018), age 65 years or older (OR, 3.04; P = .0014), and hemoglobin 12 g/dL or lower for women and 13 g/dL or lower for men (OR, 5.30; P less than .0001),

The study was sponsored by ANRS, the French National Agency for Research in AIDS and Viral Hepatitis, with support from INSERM, the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research. Dr. Hézode said that he has no financial conflicts of interest, but disclosed serving as a speaker and adviser for Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Roche.

BOSTON – In patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infections and compensated cirrhosis, a combination of a direct-acting antiviral agent, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin produced high on-treatment virologic response rates, but at the cost of significantly increased toxicities in an interim analysis of a French multicenter trial looking at the safety of the regimen.

Although the efficacy of direct-acting antiviral regimens involving the protease inhibitors telaprevir (Incivek) and boceprevir (Victrelis) combined with pegylated interferon alfa-2a or -2b in combination with ribavirin (PEG-IFN/RBV) in cirrhotic nonresponders to prior therapy was good , their safety was "poor," according to Dr. Christophe Hézode of the Hôpital Henri Mondor in Créteil, France.

Virologic response at 16 weeks in a per-protocol analysis was associated with a virologic response rate of 92% with telaprevir and 77% with boceprevir.

However, there were increased rates of serious adverse events and more difficult-to-manage anemia than in phase III trials for telaprevir and boceprevir, which included only a few patients with cirrhosis, Dr. Hézode said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

In treatment-experienced cirrhotic patients with platelet counts of 100,000/mm3 or serum albumin levels below 35 g/L, clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits of such regimens, with patients treated on a case-by-case basis because of the high risk for severe complications, Dr. Hézode said.

"However, cirrhotic experienced patients without predictors of severe complications clearly should be treated, but cautiously and carefully monitored," he added.

Dr. Hézode and his coinvestigators in the French Cohort of Therapeutic Failure and Resistances in Patients Treated With a Protease Inhibitor (telaprevir or boceprevir), Pegylated Interferon, and Ribavirin (CUPIC) trial studied two cohorts of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, and compensated cirrhosis (Child Pugh class A) who had either relapsed or had only a partial response to prior therapy, with partial response defined as at least a 2 log10 decline inV RNA but failure to clear virus by week 24.

He presented data on 497 patients who had completed 16 weeks of therapy on one of two regimens. In one cohort, 292 patients received 12 weeks of telaprevir 750 mg every 8 hours, and PEG-IFN alfa-2a (Pegasys) 180 mcg/wk with ribavirin 1,000-1,200 mg/day, followed by PEG-IFN/RBV through 48 weeks. In the second cohort, patients received a 4-week initiation phase with PEG-IFN alfa-2b (PegIntron) and ribavirin, followed by 44 weeks of boceprevir 800 mg every 8 hours, PEG-IFN 1.5 mcg/kg per wk, and ribavirin 800-1,400 mg/day.

At week 16, 45% of patients on telaprevir had had at least one serious adverse event, with 14.7% terminating therapy because of a serious side effect. In all, nearly one-fourth (22.6%) discontinued therapy, and there were five deaths: from septicemia, septic shock, pneumopathy, endocarditis, and bleeding esophageal varices. Other complications in this group included grade 3 or 4 infections in 6.5%, grade 3 or 4 hepatic decompensation in 2%, grade 3/4 asthenia in 5.5%, and renal failure in 1.7%.

Hematologic adverse events included anemia of grade 2 or greater in 30.4%, erythropoietin use in 53.8%, blood transfusion in 16.1%, and ribavirin dose reduction in 13%. In addition, 2.7% of patients had grade 3 or 4 neutropenia, and 1.7% had grade 3 or 4 thrombocytopenia.

In the boceprevir group, 32.7% had at least one serious adverse event, 26.3% discontinued prematurely, and 7.3% discontinued because of serious events. The cause of one death was described as pneumopathy. Grade 3/4 adverse events involved infections in 2.4%, hepatic decompensation in 2.9%, and asthenia in 5.8%. There were no cases of renal failure in this group.

Hematologic events in patients on boceprevir included grade 2 or greater anemia in 27.8%, erythropoietin use in 46.3%, blood transfusion in 6.3%, and ribavirin dose reduction in 10.7%.

Grade 3/4 neutropenia was seen in 4.4%, and grade 3/4 thrombocytopenia in 5.4%. Two patients (1%) in this cohort received thrombopoietin.

In a multivariate analysis, significant baseline predictors of severe complications (death, severe infection, and hepatic decompensation) included platelet counts of 100,000/mm3 or lower (odds ratio, 3.11; P = .0098) and a serum albumin level below 35 g/L (OR, 6.33; P less than .0001).

Baseline predictors for severe anemia (hemoglobin less than 8 g/dL) or blood transfusion included female gender (OR, 2.19; P = .023), no lead-in phase (OR, 2.25; P = .018), age 65 years or older (OR, 3.04; P = .0014), and hemoglobin 12 g/dL or lower for women and 13 g/dL or lower for men (OR, 5.30; P less than .0001),

The study was sponsored by ANRS, the French National Agency for Research in AIDS and Viral Hepatitis, with support from INSERM, the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research. Dr. Hézode said that he has no financial conflicts of interest, but disclosed serving as a speaker and adviser for Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Roche.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF LIVER DISEASES

Major Finding: At 16 weeks of therapy, 45% of treatment-experienced cirrhotic patients on a combination of telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin experienced a serious adverse event, as did 32.7% of patients treated with boceprevir, interferon, and ribavirin.

Data Source: Data are from an ongoing multicenter, prospective cohort study.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by ANRS, the French National Agency for Research in AIDS and Viral Hepatitis, with support from INSERM, the French National Institute for Health and Medical Research. Dr. Hézode said that he has no financial conflicts of interest, but disclosed serving as a speaker and adviser for Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, and Roche.

SurgiSIS myringoplasty shortens operative time

WASHINGTON – SurgiSIS, a material derived from porcine small intestinal mucosa, can be safely and effectively used for myringoplasty in children, based on data from a prospective, blinded study of 404 patients.

Patients’ tissue is not always available for tympanic membrane repair, and harvesting the graft may increase intraoperative time, said Dr. Riccardo D’Eredita of Vincenza (Italy) Civil Hospital. SurgiSIS (SIS) "promotes early vessel growth, provides scaffolding for remodeling tissues, and is inexpensive and ready to use." He presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

The material has been used widely in children, and data from previous studies show that SurgiSIS is gradually replaced by host cells, said Dr. D’Eredita. After 30 days, host cells invade SurgiSIS. After 1 year, SurgiSIS is no longer evident, and has been replaced by the patients’ collagen.

In this study, 404 children underwent tympanic membrane repair in 432 ears; 217 were randomized to myringoplasty with SurgiSIS and 215 were randomized to repair using the patients’ own temporalis fascia.

Overall, the group without SurgiSIS had a 97% rate of stable closures and the group with SurgiSIS had a 95% rate. Surgical time was approximately 15 minutes less for SurgiSIS-treated patients, Dr. D’Eredita said.

The researchers assessed the healing of the tympanic membranes over a 10-year period and found comparable reduction of inflammation in the two groups. There were no adverse reactions in the SIS group.

Dr. D’Eredita had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – SurgiSIS, a material derived from porcine small intestinal mucosa, can be safely and effectively used for myringoplasty in children, based on data from a prospective, blinded study of 404 patients.

Patients’ tissue is not always available for tympanic membrane repair, and harvesting the graft may increase intraoperative time, said Dr. Riccardo D’Eredita of Vincenza (Italy) Civil Hospital. SurgiSIS (SIS) "promotes early vessel growth, provides scaffolding for remodeling tissues, and is inexpensive and ready to use." He presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery Foundation.

The material has been used widely in children, and data from previous studies show that SurgiSIS is gradually replaced by host cells, said Dr. D’Eredita. After 30 days, host cells invade SurgiSIS. After 1 year, SurgiSIS is no longer evident, and has been replaced by the patients’ collagen.

In this study, 404 children underwent tympanic membrane repair in 432 ears; 217 were randomized to myringoplasty with SurgiSIS and 215 were randomized to repair using the patients’ own temporalis fascia.

Overall, the group without SurgiSIS had a 97% rate of stable closures and the group with SurgiSIS had a 95% rate. Surgical time was approximately 15 minutes less for SurgiSIS-treated patients, Dr. D’Eredita said.

The researchers assessed the healing of the tympanic membranes over a 10-year period and found comparable reduction of inflammation in the two groups. There were no adverse reactions in the SIS group.

Dr. D’Eredita had no financial conflicts to disclose.

WASHINGTON – SurgiSIS, a material derived from porcine small intestinal mucosa, can be safely and effectively used for myringoplasty in children, based on data from a prospective, blinded study of 404 patients.