User login

Hospital readmissions under attack

Readmissions after hospital discharge for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia have now become major targets for proposed Medicare savings as part of the current budget tightening in Washington. Hospitals in the past have viewed readmissions either with disdain and disinterest or as a "cash cow."

Readmissions have been good business, as long as Medicare reimbursed hospitals for individual admissions no matter how long or short or how frequent. Readmissions are estimated to cost $17 billion annually. As Medicare costs continue to increase, the control of readmissions appears to be a good target for saving some money. As a result, Medicare levied a maximum reduction of 1% on payments last year on 307 of the nation’s hospitals that were deemed to have too many readmissions (New York Times, Nov. 26, 2012).

Readmissions for AMI and heart failure are among the most frequent hospital admissions and readmissions. Readmissions in cardiology have been an important outcome measure in clinical trials for the last half century. As mortality rates decreased over the years, rehospitalization became more important as clinicians realized its importance in the composite outcome measure of cost and benefit of new therapies. Two of the potential causes of readmission have been early discharge and the lack of postdischarge medical support. The urgency for early discharge for both heart failure and AMI has been driven largely by the misplaced emphasis on shorter hospital stays.

A recent international trial examined readmission rates as an outcome measure in patients who were treated with a percutaneous coronary intervention after an ST-elevation MI. According to that study, the readmission rate in the United States is almost twice that of European centers. Much of this increase was related to a shorter hospital stay in the United States that was half that of the European centers: 8 vs. 3 days (JAMA 2012;307:66-74).

In the last few years there has actually been a speed contest in some cardiology quarters to see how quickly patients can be discharged after a STEMI. As a result, a "drive through" mentality for percutaneous coronary intervention and AMI treatment has developed. Some of this has been generated by hospital administration, but with full participation by cardiologists. There appears to be little or no benefit to the short stay other than on the hospital bottom line. It now appears that, in the future, the financial benefit of this expedited care will be challenged.

Heart failure admissions suffer from similar expedited care. The duration of a hospital stay for heart failure decreased from 8.8 to 6.3 days between 1996 and 2006. Similar international disparity exists as observed with AMI. The rate of readmission in 30 days after discharge is estimated to be roughly 20%. The occurrence of readmission within 30 days is not just an abstract statistic and an inconvenience to patients but is associated with a mortality in the same period of 6.4%, which exceeded inpatient mortality (JAMA 2010;303;2141-7).

Many patients admitted with fluid overload leave the hospital on the same medication that they were taking prior to admission and at the same weight as at admission. Some of this is the result of undertreatment with diuretics, driven by misconceptions about serum creatinine levels, but in many situations patients may not even be weighed. Heart failure patients are often elderly who have significant concomitant disease and require careful in-hospital modification of heart failure therapy. Many of these elderly patients also require the institution of medical and social support prior to discharge.

Inner-city and referral hospitals indicate that they are being unfairly penalized by the nature of the demographic and severity of their patient mix. Some of this pushback is warranted. The "one size fits all" approach by Medicare may well require some modification in view of the variation in both the medical and social complexity. Some form of staging of severity and the need for outpatient nurse support needs to be considered.

Hospitals, nevertheless, are scrambling to respond to the Medicare threat and have begun to apply resources and innovation to solve this pressing issue. Cardiologists themselves also can have an important impact on the problem. We all need to slow down and spend some time dealing with the long-term solutions to short-term problems like acute heart failure and AMI.

Dr. Goldstein writes the column, "Heart of the Matter," which appears regularly in Cardiology News, a Frontline Medical Communications publication. He is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Readmissions after hospital discharge for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia have now become major targets for proposed Medicare savings as part of the current budget tightening in Washington. Hospitals in the past have viewed readmissions either with disdain and disinterest or as a "cash cow."

Readmissions have been good business, as long as Medicare reimbursed hospitals for individual admissions no matter how long or short or how frequent. Readmissions are estimated to cost $17 billion annually. As Medicare costs continue to increase, the control of readmissions appears to be a good target for saving some money. As a result, Medicare levied a maximum reduction of 1% on payments last year on 307 of the nation’s hospitals that were deemed to have too many readmissions (New York Times, Nov. 26, 2012).

Readmissions for AMI and heart failure are among the most frequent hospital admissions and readmissions. Readmissions in cardiology have been an important outcome measure in clinical trials for the last half century. As mortality rates decreased over the years, rehospitalization became more important as clinicians realized its importance in the composite outcome measure of cost and benefit of new therapies. Two of the potential causes of readmission have been early discharge and the lack of postdischarge medical support. The urgency for early discharge for both heart failure and AMI has been driven largely by the misplaced emphasis on shorter hospital stays.

A recent international trial examined readmission rates as an outcome measure in patients who were treated with a percutaneous coronary intervention after an ST-elevation MI. According to that study, the readmission rate in the United States is almost twice that of European centers. Much of this increase was related to a shorter hospital stay in the United States that was half that of the European centers: 8 vs. 3 days (JAMA 2012;307:66-74).

In the last few years there has actually been a speed contest in some cardiology quarters to see how quickly patients can be discharged after a STEMI. As a result, a "drive through" mentality for percutaneous coronary intervention and AMI treatment has developed. Some of this has been generated by hospital administration, but with full participation by cardiologists. There appears to be little or no benefit to the short stay other than on the hospital bottom line. It now appears that, in the future, the financial benefit of this expedited care will be challenged.

Heart failure admissions suffer from similar expedited care. The duration of a hospital stay for heart failure decreased from 8.8 to 6.3 days between 1996 and 2006. Similar international disparity exists as observed with AMI. The rate of readmission in 30 days after discharge is estimated to be roughly 20%. The occurrence of readmission within 30 days is not just an abstract statistic and an inconvenience to patients but is associated with a mortality in the same period of 6.4%, which exceeded inpatient mortality (JAMA 2010;303;2141-7).

Many patients admitted with fluid overload leave the hospital on the same medication that they were taking prior to admission and at the same weight as at admission. Some of this is the result of undertreatment with diuretics, driven by misconceptions about serum creatinine levels, but in many situations patients may not even be weighed. Heart failure patients are often elderly who have significant concomitant disease and require careful in-hospital modification of heart failure therapy. Many of these elderly patients also require the institution of medical and social support prior to discharge.

Inner-city and referral hospitals indicate that they are being unfairly penalized by the nature of the demographic and severity of their patient mix. Some of this pushback is warranted. The "one size fits all" approach by Medicare may well require some modification in view of the variation in both the medical and social complexity. Some form of staging of severity and the need for outpatient nurse support needs to be considered.

Hospitals, nevertheless, are scrambling to respond to the Medicare threat and have begun to apply resources and innovation to solve this pressing issue. Cardiologists themselves also can have an important impact on the problem. We all need to slow down and spend some time dealing with the long-term solutions to short-term problems like acute heart failure and AMI.

Dr. Goldstein writes the column, "Heart of the Matter," which appears regularly in Cardiology News, a Frontline Medical Communications publication. He is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Readmissions after hospital discharge for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia have now become major targets for proposed Medicare savings as part of the current budget tightening in Washington. Hospitals in the past have viewed readmissions either with disdain and disinterest or as a "cash cow."

Readmissions have been good business, as long as Medicare reimbursed hospitals for individual admissions no matter how long or short or how frequent. Readmissions are estimated to cost $17 billion annually. As Medicare costs continue to increase, the control of readmissions appears to be a good target for saving some money. As a result, Medicare levied a maximum reduction of 1% on payments last year on 307 of the nation’s hospitals that were deemed to have too many readmissions (New York Times, Nov. 26, 2012).

Readmissions for AMI and heart failure are among the most frequent hospital admissions and readmissions. Readmissions in cardiology have been an important outcome measure in clinical trials for the last half century. As mortality rates decreased over the years, rehospitalization became more important as clinicians realized its importance in the composite outcome measure of cost and benefit of new therapies. Two of the potential causes of readmission have been early discharge and the lack of postdischarge medical support. The urgency for early discharge for both heart failure and AMI has been driven largely by the misplaced emphasis on shorter hospital stays.

A recent international trial examined readmission rates as an outcome measure in patients who were treated with a percutaneous coronary intervention after an ST-elevation MI. According to that study, the readmission rate in the United States is almost twice that of European centers. Much of this increase was related to a shorter hospital stay in the United States that was half that of the European centers: 8 vs. 3 days (JAMA 2012;307:66-74).

In the last few years there has actually been a speed contest in some cardiology quarters to see how quickly patients can be discharged after a STEMI. As a result, a "drive through" mentality for percutaneous coronary intervention and AMI treatment has developed. Some of this has been generated by hospital administration, but with full participation by cardiologists. There appears to be little or no benefit to the short stay other than on the hospital bottom line. It now appears that, in the future, the financial benefit of this expedited care will be challenged.

Heart failure admissions suffer from similar expedited care. The duration of a hospital stay for heart failure decreased from 8.8 to 6.3 days between 1996 and 2006. Similar international disparity exists as observed with AMI. The rate of readmission in 30 days after discharge is estimated to be roughly 20%. The occurrence of readmission within 30 days is not just an abstract statistic and an inconvenience to patients but is associated with a mortality in the same period of 6.4%, which exceeded inpatient mortality (JAMA 2010;303;2141-7).

Many patients admitted with fluid overload leave the hospital on the same medication that they were taking prior to admission and at the same weight as at admission. Some of this is the result of undertreatment with diuretics, driven by misconceptions about serum creatinine levels, but in many situations patients may not even be weighed. Heart failure patients are often elderly who have significant concomitant disease and require careful in-hospital modification of heart failure therapy. Many of these elderly patients also require the institution of medical and social support prior to discharge.

Inner-city and referral hospitals indicate that they are being unfairly penalized by the nature of the demographic and severity of their patient mix. Some of this pushback is warranted. The "one size fits all" approach by Medicare may well require some modification in view of the variation in both the medical and social complexity. Some form of staging of severity and the need for outpatient nurse support needs to be considered.

Hospitals, nevertheless, are scrambling to respond to the Medicare threat and have begun to apply resources and innovation to solve this pressing issue. Cardiologists themselves also can have an important impact on the problem. We all need to slow down and spend some time dealing with the long-term solutions to short-term problems like acute heart failure and AMI.

Dr. Goldstein writes the column, "Heart of the Matter," which appears regularly in Cardiology News, a Frontline Medical Communications publication. He is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

Rate of pediatric caustic ingestion injuries quite low

The prevalence of caustic ingestion injuries among children and adolescents in the United States is quite low, estimated to be only 1.08 per 100,000 population, according to a report in the December issue of Archives of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery.

This represents a substantial decrease from figures widely stated in the literature, which are based on data from the 1970s and 1980s, when public health measures were first taken to reduce children’s exposure to lye and other caustics, said Dr. Christopher M. Johnson and Dr. Matthew T. Brigger of the department of otolaryngology, Naval Medical Center, San Diego.

"The burden of caustic ingestion injuries in children appears to have decreased over time, and past public health interventions appear to have been successful," Dr. Johnson and Dr. Brigger wrote.

They examined this issue in part because of the paucity of epidemiologic data regarding caustic ingestions. To assess the current public health burden of these pediatric injuries, they analyzed information in the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID), a national resource maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which collects nationally representative samples of all pediatric hospital discharges each year.

The researchers assessed KID data for 2009, when 3,407,146 pediatric hospitalizations were sampled.

Extrapolating the data to the entire U.S. population, the investigators estimated that there were 807 hospitalizations nationwide for caustic ingestion injuries among patients aged 0-18 years in 2009, for a prevalence of 1.08 per 100,000.

Previously published estimates ranged from 5,000 to 15,000 cases each year but were based on outdated data, the investigators noted (Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012;138:1111-5).

Even though the actual prevalence of these injuries has dropped so precipitously, children with caustic ingestion injuries still accounted for more than $22 million in hospital charges and more than 3,300 inpatient days in 2009, they reported.

Approximately 60% of these ingestions occurred in children aged 4 years and younger. A second peak in prevalence occurred in the adolescent age group, presumably because of intentional ingestions in suicide attempts.

Only about half of all pediatric patients hospitalized for caustic ingestion underwent esophagoscopy in 2009. Since this procedure is recommended for all children with a "strongly suggestive" history as well as for those who are symptomatic, "a logical conclusion is that a large proportion of children are admitted to the hospital for observation, even if suspicion of significant injury is low," Dr. Johnson and Dr. Brigger said.

"We found a higher burden of injury in urban hospitals and in patients who lived in zip codes in the bottom quartile of median annual income in the United States. This finding is consistent with available pediatric poisoning data that indicate that low-income urban households are more likely to store dangerous household products improperly," they added.

No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

The prevalence of caustic ingestion injuries among children and adolescents in the United States is quite low, estimated to be only 1.08 per 100,000 population, according to a report in the December issue of Archives of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery.

This represents a substantial decrease from figures widely stated in the literature, which are based on data from the 1970s and 1980s, when public health measures were first taken to reduce children’s exposure to lye and other caustics, said Dr. Christopher M. Johnson and Dr. Matthew T. Brigger of the department of otolaryngology, Naval Medical Center, San Diego.

"The burden of caustic ingestion injuries in children appears to have decreased over time, and past public health interventions appear to have been successful," Dr. Johnson and Dr. Brigger wrote.

They examined this issue in part because of the paucity of epidemiologic data regarding caustic ingestions. To assess the current public health burden of these pediatric injuries, they analyzed information in the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID), a national resource maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which collects nationally representative samples of all pediatric hospital discharges each year.

The researchers assessed KID data for 2009, when 3,407,146 pediatric hospitalizations were sampled.

Extrapolating the data to the entire U.S. population, the investigators estimated that there were 807 hospitalizations nationwide for caustic ingestion injuries among patients aged 0-18 years in 2009, for a prevalence of 1.08 per 100,000.

Previously published estimates ranged from 5,000 to 15,000 cases each year but were based on outdated data, the investigators noted (Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012;138:1111-5).

Even though the actual prevalence of these injuries has dropped so precipitously, children with caustic ingestion injuries still accounted for more than $22 million in hospital charges and more than 3,300 inpatient days in 2009, they reported.

Approximately 60% of these ingestions occurred in children aged 4 years and younger. A second peak in prevalence occurred in the adolescent age group, presumably because of intentional ingestions in suicide attempts.

Only about half of all pediatric patients hospitalized for caustic ingestion underwent esophagoscopy in 2009. Since this procedure is recommended for all children with a "strongly suggestive" history as well as for those who are symptomatic, "a logical conclusion is that a large proportion of children are admitted to the hospital for observation, even if suspicion of significant injury is low," Dr. Johnson and Dr. Brigger said.

"We found a higher burden of injury in urban hospitals and in patients who lived in zip codes in the bottom quartile of median annual income in the United States. This finding is consistent with available pediatric poisoning data that indicate that low-income urban households are more likely to store dangerous household products improperly," they added.

No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

The prevalence of caustic ingestion injuries among children and adolescents in the United States is quite low, estimated to be only 1.08 per 100,000 population, according to a report in the December issue of Archives of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery.

This represents a substantial decrease from figures widely stated in the literature, which are based on data from the 1970s and 1980s, when public health measures were first taken to reduce children’s exposure to lye and other caustics, said Dr. Christopher M. Johnson and Dr. Matthew T. Brigger of the department of otolaryngology, Naval Medical Center, San Diego.

"The burden of caustic ingestion injuries in children appears to have decreased over time, and past public health interventions appear to have been successful," Dr. Johnson and Dr. Brigger wrote.

They examined this issue in part because of the paucity of epidemiologic data regarding caustic ingestions. To assess the current public health burden of these pediatric injuries, they analyzed information in the Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID), a national resource maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, which collects nationally representative samples of all pediatric hospital discharges each year.

The researchers assessed KID data for 2009, when 3,407,146 pediatric hospitalizations were sampled.

Extrapolating the data to the entire U.S. population, the investigators estimated that there were 807 hospitalizations nationwide for caustic ingestion injuries among patients aged 0-18 years in 2009, for a prevalence of 1.08 per 100,000.

Previously published estimates ranged from 5,000 to 15,000 cases each year but were based on outdated data, the investigators noted (Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012;138:1111-5).

Even though the actual prevalence of these injuries has dropped so precipitously, children with caustic ingestion injuries still accounted for more than $22 million in hospital charges and more than 3,300 inpatient days in 2009, they reported.

Approximately 60% of these ingestions occurred in children aged 4 years and younger. A second peak in prevalence occurred in the adolescent age group, presumably because of intentional ingestions in suicide attempts.

Only about half of all pediatric patients hospitalized for caustic ingestion underwent esophagoscopy in 2009. Since this procedure is recommended for all children with a "strongly suggestive" history as well as for those who are symptomatic, "a logical conclusion is that a large proportion of children are admitted to the hospital for observation, even if suspicion of significant injury is low," Dr. Johnson and Dr. Brigger said.

"We found a higher burden of injury in urban hospitals and in patients who lived in zip codes in the bottom quartile of median annual income in the United States. This finding is consistent with available pediatric poisoning data that indicate that low-income urban households are more likely to store dangerous household products improperly," they added.

No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM ARCHIVES OF OTOLARYNGOLOGY AND HEAD & NECK SURGERY

Major Finding: There were an estimated 807 children and adolescents hospitalized nationwide for caustic ingestion injuries in 2009, for a prevalence of 1.08 per 100,000.

Data Source: An analysis of pediatric hospitalizations for caustic ingestion injuries using data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Kids’ Inpatient Database.

Disclosures: No financial conflicts of interest were reported.

Laparoscopic diverticulitis surgery linked to fewer complications

PALM BEACH, FLA.– Using laparoscopic surgery for colectomy with primary anastomosis in patients with complicated diverticulitis linked with significantly fewer major complications compared with open surgical management in a review of more than 10,000 patients from a nationwide database.

However, the inherent biases at play when surgeons decide whether to manage a diverticulitis patient by a laparoscopic or open approach make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the findings, Dr. Edward E. Cornwell III said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"If a surgeon did an operation laparoscopically, that by itself is an indicator of how sick the patient was. The surgeon selects an open operation for sicker patients, and laparoscopy for the less sick patients," he said in an interview. "Have we accounted for that difference [in the analysis]? That’s an open question," said Dr. Cornwell, professor and chairman of surgery at Howard University in Washington.

"Patients whom the surgeon deem well enough physiologically to sustain colectomy with primary anastomosis deserve strong consideration for the laparoscopic approach because those patients had the greatest difference in complications" compared with open surgery, he said.

The data Dr. Cornwell and his associates reviewed also showed a marked skewing in how surgeons used laparoscopy. Among the 10,085 patients included in the analysis, 7,562 (75%) underwent colectomy with primary anastomosis, and in this subgroup, 5,105 patients (68%) had their surgery done laparoscopically, while the remaining 2,457 (32%) were done with open surgery. In contrast, the 2,523 other patients in the series underwent a colectomy with colostomy, and within this subgroup, 2,286 patients (91%) had open surgery, with only 237 (9%) having laparoscopic surgery.

The overwhelming use of open surgery for the colostomy patients makes sense as it is a more complex operation, Dr. Cornwell said.

He and his associates used data collected during 2005-2009 at 237 U.S. hospitals by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons on patients who underwent surgical management of complicated diverticulitis. The average age of the patients was 58 years, and overall 30-day mortality was 2%, while the overall postoperative complication rate during the 30 days following surgery was 23%.

Among the patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients, a statistically significant difference. Major complications included surgical site infections, dehiscence, transfusion, respiratory failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke, renal failure or need for rehospitalization.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographic parameters, body mass index, comorbidities, and functional status, patients who underwent laparoscopy had about half the number of total complications and major complications compared with patients who underwent open surgery – statistically significant differences. The laparoscopically-treated patients also had roughly half the rate of several individual major complications – wound infections, respiratory complications, and sepsis – compared with the open surgery patients, all statistically significant differences.

Thirty-day mortality was about 50% lower with laparoscopy compared with open surgery among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The advantage of laparoscopy over open surgery was not nearly so clear among patients who underwent colectomy with colostomy. The data showed no significant difference between laparoscopy and open surgery in the rate of all major complications, although the number of major complications with laparoscopy was about 20% lower. The only individual complications significantly reduced in the laparoscopy group were wound infections, reduced by about 40% in the adjusted analysis, and respiratory complications, cut by about 50% by laparoscopy. The two surgical subgroups showed virtually no difference in 30-day mortality among patients who underwent a colectomy.

The results suggest that because of the broad reduction of major complications with laparoscopy, this approach "should be considered when primary anastomosis is deemed appropriate," Dr. Cornwell concluded.

Dr. Cornwell said that he had no disclosures.

This work falls somewhat short of actually comparing the efficacy of the laparoscopic approach and open surgery in patients with complicated diverticulitis. Without an adequate standardized description of the disease process itself, the patients’ comorbidities, and their physiologic perturbation at the time of presentation, it is exceedingly difficult to measure outcomes and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

I’m afraid the authors have not satisfactorily controlled for or analyzed the confounding factors so that plausible conclusions can be reached. The results are striking that mortality and complications were higher for patients treated with open surgery. I have watched the evolution of laparoscopic surgery over the past 25 years, and I am convinced that patients greatly benefit from this technology.

While the laparoscopic approach for treating diverticulitis resonates with my sensibility, the data do not support a clear recommendation. I urge surgeons to focus on this emergency, general-surgery population so that we can do important comparative effectiveness research and address some of these questions.

Dr. Michael F. Rotondo is professor and chairman of surgery at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as a designated discussant of the report.

This work falls somewhat short of actually comparing the efficacy of the laparoscopic approach and open surgery in patients with complicated diverticulitis. Without an adequate standardized description of the disease process itself, the patients’ comorbidities, and their physiologic perturbation at the time of presentation, it is exceedingly difficult to measure outcomes and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

I’m afraid the authors have not satisfactorily controlled for or analyzed the confounding factors so that plausible conclusions can be reached. The results are striking that mortality and complications were higher for patients treated with open surgery. I have watched the evolution of laparoscopic surgery over the past 25 years, and I am convinced that patients greatly benefit from this technology.

While the laparoscopic approach for treating diverticulitis resonates with my sensibility, the data do not support a clear recommendation. I urge surgeons to focus on this emergency, general-surgery population so that we can do important comparative effectiveness research and address some of these questions.

Dr. Michael F. Rotondo is professor and chairman of surgery at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as a designated discussant of the report.

This work falls somewhat short of actually comparing the efficacy of the laparoscopic approach and open surgery in patients with complicated diverticulitis. Without an adequate standardized description of the disease process itself, the patients’ comorbidities, and their physiologic perturbation at the time of presentation, it is exceedingly difficult to measure outcomes and the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

I’m afraid the authors have not satisfactorily controlled for or analyzed the confounding factors so that plausible conclusions can be reached. The results are striking that mortality and complications were higher for patients treated with open surgery. I have watched the evolution of laparoscopic surgery over the past 25 years, and I am convinced that patients greatly benefit from this technology.

While the laparoscopic approach for treating diverticulitis resonates with my sensibility, the data do not support a clear recommendation. I urge surgeons to focus on this emergency, general-surgery population so that we can do important comparative effectiveness research and address some of these questions.

Dr. Michael F. Rotondo is professor and chairman of surgery at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. He had no disclosures. He made these comments as a designated discussant of the report.

PALM BEACH, FLA.– Using laparoscopic surgery for colectomy with primary anastomosis in patients with complicated diverticulitis linked with significantly fewer major complications compared with open surgical management in a review of more than 10,000 patients from a nationwide database.

However, the inherent biases at play when surgeons decide whether to manage a diverticulitis patient by a laparoscopic or open approach make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the findings, Dr. Edward E. Cornwell III said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"If a surgeon did an operation laparoscopically, that by itself is an indicator of how sick the patient was. The surgeon selects an open operation for sicker patients, and laparoscopy for the less sick patients," he said in an interview. "Have we accounted for that difference [in the analysis]? That’s an open question," said Dr. Cornwell, professor and chairman of surgery at Howard University in Washington.

"Patients whom the surgeon deem well enough physiologically to sustain colectomy with primary anastomosis deserve strong consideration for the laparoscopic approach because those patients had the greatest difference in complications" compared with open surgery, he said.

The data Dr. Cornwell and his associates reviewed also showed a marked skewing in how surgeons used laparoscopy. Among the 10,085 patients included in the analysis, 7,562 (75%) underwent colectomy with primary anastomosis, and in this subgroup, 5,105 patients (68%) had their surgery done laparoscopically, while the remaining 2,457 (32%) were done with open surgery. In contrast, the 2,523 other patients in the series underwent a colectomy with colostomy, and within this subgroup, 2,286 patients (91%) had open surgery, with only 237 (9%) having laparoscopic surgery.

The overwhelming use of open surgery for the colostomy patients makes sense as it is a more complex operation, Dr. Cornwell said.

He and his associates used data collected during 2005-2009 at 237 U.S. hospitals by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons on patients who underwent surgical management of complicated diverticulitis. The average age of the patients was 58 years, and overall 30-day mortality was 2%, while the overall postoperative complication rate during the 30 days following surgery was 23%.

Among the patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients, a statistically significant difference. Major complications included surgical site infections, dehiscence, transfusion, respiratory failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke, renal failure or need for rehospitalization.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographic parameters, body mass index, comorbidities, and functional status, patients who underwent laparoscopy had about half the number of total complications and major complications compared with patients who underwent open surgery – statistically significant differences. The laparoscopically-treated patients also had roughly half the rate of several individual major complications – wound infections, respiratory complications, and sepsis – compared with the open surgery patients, all statistically significant differences.

Thirty-day mortality was about 50% lower with laparoscopy compared with open surgery among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The advantage of laparoscopy over open surgery was not nearly so clear among patients who underwent colectomy with colostomy. The data showed no significant difference between laparoscopy and open surgery in the rate of all major complications, although the number of major complications with laparoscopy was about 20% lower. The only individual complications significantly reduced in the laparoscopy group were wound infections, reduced by about 40% in the adjusted analysis, and respiratory complications, cut by about 50% by laparoscopy. The two surgical subgroups showed virtually no difference in 30-day mortality among patients who underwent a colectomy.

The results suggest that because of the broad reduction of major complications with laparoscopy, this approach "should be considered when primary anastomosis is deemed appropriate," Dr. Cornwell concluded.

Dr. Cornwell said that he had no disclosures.

PALM BEACH, FLA.– Using laparoscopic surgery for colectomy with primary anastomosis in patients with complicated diverticulitis linked with significantly fewer major complications compared with open surgical management in a review of more than 10,000 patients from a nationwide database.

However, the inherent biases at play when surgeons decide whether to manage a diverticulitis patient by a laparoscopic or open approach make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions from the findings, Dr. Edward E. Cornwell III said at the annual meeting of the Southern Surgical Association.

"If a surgeon did an operation laparoscopically, that by itself is an indicator of how sick the patient was. The surgeon selects an open operation for sicker patients, and laparoscopy for the less sick patients," he said in an interview. "Have we accounted for that difference [in the analysis]? That’s an open question," said Dr. Cornwell, professor and chairman of surgery at Howard University in Washington.

"Patients whom the surgeon deem well enough physiologically to sustain colectomy with primary anastomosis deserve strong consideration for the laparoscopic approach because those patients had the greatest difference in complications" compared with open surgery, he said.

The data Dr. Cornwell and his associates reviewed also showed a marked skewing in how surgeons used laparoscopy. Among the 10,085 patients included in the analysis, 7,562 (75%) underwent colectomy with primary anastomosis, and in this subgroup, 5,105 patients (68%) had their surgery done laparoscopically, while the remaining 2,457 (32%) were done with open surgery. In contrast, the 2,523 other patients in the series underwent a colectomy with colostomy, and within this subgroup, 2,286 patients (91%) had open surgery, with only 237 (9%) having laparoscopic surgery.

The overwhelming use of open surgery for the colostomy patients makes sense as it is a more complex operation, Dr. Cornwell said.

He and his associates used data collected during 2005-2009 at 237 U.S. hospitals by the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program of the American College of Surgeons on patients who underwent surgical management of complicated diverticulitis. The average age of the patients was 58 years, and overall 30-day mortality was 2%, while the overall postoperative complication rate during the 30 days following surgery was 23%.

Among the patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients, a statistically significant difference. Major complications included surgical site infections, dehiscence, transfusion, respiratory failure, sepsis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, stroke, renal failure or need for rehospitalization.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for demographic parameters, body mass index, comorbidities, and functional status, patients who underwent laparoscopy had about half the number of total complications and major complications compared with patients who underwent open surgery – statistically significant differences. The laparoscopically-treated patients also had roughly half the rate of several individual major complications – wound infections, respiratory complications, and sepsis – compared with the open surgery patients, all statistically significant differences.

Thirty-day mortality was about 50% lower with laparoscopy compared with open surgery among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, but this difference fell short of statistical significance.

The advantage of laparoscopy over open surgery was not nearly so clear among patients who underwent colectomy with colostomy. The data showed no significant difference between laparoscopy and open surgery in the rate of all major complications, although the number of major complications with laparoscopy was about 20% lower. The only individual complications significantly reduced in the laparoscopy group were wound infections, reduced by about 40% in the adjusted analysis, and respiratory complications, cut by about 50% by laparoscopy. The two surgical subgroups showed virtually no difference in 30-day mortality among patients who underwent a colectomy.

The results suggest that because of the broad reduction of major complications with laparoscopy, this approach "should be considered when primary anastomosis is deemed appropriate," Dr. Cornwell concluded.

Dr. Cornwell said that he had no disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE SOUTHERN SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Major Finding: Among patients who underwent a primary anastomosis, the incidence of major complications during 30 days of follow-up was 13% in the open surgery patients and 6% in the laparoscopy patients.

Data Source: From 10,085 U.S. patients who had surgery for acute management of complicated diverticulitis during 2005-2009.

Disclosures: Dr. Cornwell said he had no disclosures.

Chronic constipation may increase colorectal cancer risk

Chronic constipation may predispose affected patients to developing colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms, according to an analysis of data from a large retrospective U.S. claims database.

The risk of developing colorectal cancer was 1.78 times higher among 28,854 adults with chronic constipation than among 86,562 controls without chronic constipation, and the risk of developing benign neoplasms was 2.7 times higher in those with chronic constipation, Dr. Nicholas Talley reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The risk of colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms among those with chronic constipation remained "consistently high" after researchers controlled for potential confounding factors, including age, gender, family history of malignancies, and other nongastrointestinal morbidities, said Dr. Talley of the University of Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales, Australia.

Patients included adults aged older than 18 years who received at least two diagnoses of chronic constipation 60-365 days apart between January 1999 and September 2011. Those with irritable bowel syndrome or diarrhea were excluded, as were those who did not remain enrolled in their health plans for at least 12 months from the date of their first eligible diagnosis of constipation.

The investigators matched control subjects, who had never been diagnosed with constipation and never had a prescription filled for a laxative during the observation period, with case patients in a 1:3 ratio based on year of birth, sex, and region of residence.

Patients and controls had a mean age of 61.9 years, and one-third were men. The mean observation period was nearly 4 years.

The prevalence of colorectal cancer in this study was 2.7% in the patients and 1.7% in the controls; the prevalence of benign neoplasms was 24.8% in the patients and 11.9% in the controls, Dr. Talley said.

Although the findings do not prove a causal link between chronic constipation and colorectal cancer or benign neoplasms, they do suggest a strong association, he said in a press statement.

"The postulated causal link is that longer transit times increase the duration of contact between the colonic mucosa and concentrated carcinogens such as bile acids in the lumen," he said.

This association deserves further investigation to more thoroughly explore and to better understand possible causal elements, he added.

This is particularly important because prospective cohort studies have failed to identify a similar association to that seen in this retrospective review, suggesting that those findings are affected by recall bias, he said.

While further study is needed, practitioners should be aware of the potential relationship between chronic constipation and development of colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms, and should monitor and treat patients accordingly, he concluded.

Dr. Talley received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, which supported the study. Coauthors were employed by Takeda or by Analysis Group Inc., which has received consulting fees from Takeda.

Chronic constipation may predispose affected patients to developing colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms, according to an analysis of data from a large retrospective U.S. claims database.

The risk of developing colorectal cancer was 1.78 times higher among 28,854 adults with chronic constipation than among 86,562 controls without chronic constipation, and the risk of developing benign neoplasms was 2.7 times higher in those with chronic constipation, Dr. Nicholas Talley reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The risk of colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms among those with chronic constipation remained "consistently high" after researchers controlled for potential confounding factors, including age, gender, family history of malignancies, and other nongastrointestinal morbidities, said Dr. Talley of the University of Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales, Australia.

Patients included adults aged older than 18 years who received at least two diagnoses of chronic constipation 60-365 days apart between January 1999 and September 2011. Those with irritable bowel syndrome or diarrhea were excluded, as were those who did not remain enrolled in their health plans for at least 12 months from the date of their first eligible diagnosis of constipation.

The investigators matched control subjects, who had never been diagnosed with constipation and never had a prescription filled for a laxative during the observation period, with case patients in a 1:3 ratio based on year of birth, sex, and region of residence.

Patients and controls had a mean age of 61.9 years, and one-third were men. The mean observation period was nearly 4 years.

The prevalence of colorectal cancer in this study was 2.7% in the patients and 1.7% in the controls; the prevalence of benign neoplasms was 24.8% in the patients and 11.9% in the controls, Dr. Talley said.

Although the findings do not prove a causal link between chronic constipation and colorectal cancer or benign neoplasms, they do suggest a strong association, he said in a press statement.

"The postulated causal link is that longer transit times increase the duration of contact between the colonic mucosa and concentrated carcinogens such as bile acids in the lumen," he said.

This association deserves further investigation to more thoroughly explore and to better understand possible causal elements, he added.

This is particularly important because prospective cohort studies have failed to identify a similar association to that seen in this retrospective review, suggesting that those findings are affected by recall bias, he said.

While further study is needed, practitioners should be aware of the potential relationship between chronic constipation and development of colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms, and should monitor and treat patients accordingly, he concluded.

Dr. Talley received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, which supported the study. Coauthors were employed by Takeda or by Analysis Group Inc., which has received consulting fees from Takeda.

Chronic constipation may predispose affected patients to developing colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms, according to an analysis of data from a large retrospective U.S. claims database.

The risk of developing colorectal cancer was 1.78 times higher among 28,854 adults with chronic constipation than among 86,562 controls without chronic constipation, and the risk of developing benign neoplasms was 2.7 times higher in those with chronic constipation, Dr. Nicholas Talley reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the American College of Gastroenterology.

The risk of colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms among those with chronic constipation remained "consistently high" after researchers controlled for potential confounding factors, including age, gender, family history of malignancies, and other nongastrointestinal morbidities, said Dr. Talley of the University of Newcastle, Callaghan, New South Wales, Australia.

Patients included adults aged older than 18 years who received at least two diagnoses of chronic constipation 60-365 days apart between January 1999 and September 2011. Those with irritable bowel syndrome or diarrhea were excluded, as were those who did not remain enrolled in their health plans for at least 12 months from the date of their first eligible diagnosis of constipation.

The investigators matched control subjects, who had never been diagnosed with constipation and never had a prescription filled for a laxative during the observation period, with case patients in a 1:3 ratio based on year of birth, sex, and region of residence.

Patients and controls had a mean age of 61.9 years, and one-third were men. The mean observation period was nearly 4 years.

The prevalence of colorectal cancer in this study was 2.7% in the patients and 1.7% in the controls; the prevalence of benign neoplasms was 24.8% in the patients and 11.9% in the controls, Dr. Talley said.

Although the findings do not prove a causal link between chronic constipation and colorectal cancer or benign neoplasms, they do suggest a strong association, he said in a press statement.

"The postulated causal link is that longer transit times increase the duration of contact between the colonic mucosa and concentrated carcinogens such as bile acids in the lumen," he said.

This association deserves further investigation to more thoroughly explore and to better understand possible causal elements, he added.

This is particularly important because prospective cohort studies have failed to identify a similar association to that seen in this retrospective review, suggesting that those findings are affected by recall bias, he said.

While further study is needed, practitioners should be aware of the potential relationship between chronic constipation and development of colorectal cancer and benign neoplasms, and should monitor and treat patients accordingly, he concluded.

Dr. Talley received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, which supported the study. Coauthors were employed by Takeda or by Analysis Group Inc., which has received consulting fees from Takeda.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Major Finding: The risk of developing colorectal cancer was 1.78 times higher in 28,854 adults with chronic constipation than in 86,562 controls without chronic constipation, and the risk of developing benign neoplasms was 2.7 times higher in those with chronic constipation.

Data Source: A large retrospective U.S. claims database.

Disclosures: Dr. Talley received research support from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, which supported the study. Coauthors were employed by Takeda or by Analysis Group Inc., which has received consulting fees from Takeda.

Study supports extended apixaban use

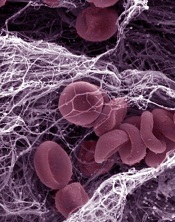

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

ATLANTA—Due to results of the AMPLIFY-EXTENSION study, researchers are recommending a new indication for apixaban: long-term use to prevent recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Study investigators compared 12 months of treatment with apixaban at 2 doses—2.5 mg and 5 mg—to placebo in patients who had previously received anticoagulant therapy for 6 to 12 months to treat a prior VTE.

The team found that both doses of apixaban effectively prevented VTE, VTE-related events, and death. And the incidence of bleeding events was low in all treatment arms.

“We believe that the study, given the results we achieved, should support the use of apixaban for the extended treatment of VTE,” said Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, of the University of Perugia in Italy.

Dr Agnelli presented these results in the late-breaking abstract session (LBA-1) of the 54th ASH Annual Meeting, which took place here December 8-11.

More detailed results of the study—which was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer, joint developers of apixaban—have been published in NEJM.

Dr Agnelli noted that apixaban has proven effective as VTE prophylaxis when given at 2.5 mg after hip or knee replacement surgery. And the drug has been administered at 5 mg as stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.

So he and his colleagues wanted to determine if apixaban might be effective as long-term VTE prophylaxis in patients with a previous thrombotic event, as well as which dose might be optimal for these patients.

To find out, the researchers enrolled 2482 patients with a prior VTE who had completed 6 to 12 months of oral anticoagulant treatment without VTE recurrence or bleeding.

The team randomized 840 patients to receive apixaban at 2.5 mg BID, 813 patients to receive the drug at 5 mg BID, and 829 patients to receive placebo.

The patients were well-matched according age, gender, weight, initial diagnosis, and VTE clinical presentation. They received treatment for 12 months, after which they were followed for 30 days.

Efficacy data

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was recurrent VTE or all-cause death. During the 12-month active study period, these events occurred in 32 patients (3.8%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 34 patients (4.2%) in the 5-mg arm, and 96 patients (11.6%) in the placebo arm. Both apixaban doses were significantly superior to placebo (P<0.001).

The researchers also calculated the incidence of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death. And these events occurred in 14 patients (1.7%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 14 patients (1.7%) in the 5-mg arm, and 73 patients (8.8%) in the placebo arm. Both apixaban doses were significantly superior to placebo (P<0.001).

A third composite endpoint consisted of recurrent VTE, VTE-related death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular-related death. This endpoint was met by 18 patients (2.1%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 19 patients (2.3%) in the 5-mg arm, and 83 patients (10.0%) in the placebo arm.

Overall, both doses of apixaban reduced the risk of fatal and non-fatal recurrent venous thromboembolism by 80%, Dr Agnelli said.

Events during follow-up

During the 30-day follow-up period, symptomatic, recurrent VTE occurred in 2 patients (0.2%) who had received placebo, 3 patients (0.4%) who had received apixaban at 2.5 mg, and 5 patients (0.6%) who had received apixaban at 5 mg.

The composite outcome of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death related to cardiovascular disease occurred in 2 patients: 1 who had received the lower dose of apixaban and 1 who received the higher dose.

Safety data

The study’s primary safety endpoint was major bleeding. In the 2.5-mg arm, 2 patients (0.2%) experienced major bleeding events, both of which were intraocular bleeds.

One patient (0.1%) in the 5-mg arm experienced a major gastrointestinal bleed. And 4 patients (0.5%) in the placebo arm experienced major bleeding events, including 1 intraocular bleed, 1 stroke, 1 urogenital bleed, and 1 gastrointestinal bleed.

A secondary endpoint was clinically relevant, non-major bleeding. This occurred in 25 patients (3.0%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 34 patients (4.2%) in the 5-mg arm, and 19 patients (2.3%) in the placebo arm.

Dr Agnelli and his colleagues also combined the major bleeding data and the clinically relevant, non-major bleeding data. So 27 patients (3.2%) in the 2.5-mg arm had a bleeding event of either kind, as did 35 patients (4.3%) in the 5-mg arm and 22 patients (2.7%) in the placebo arm.

Clinical interpretation

Finally, the researchers tried to put this data into a clinical context. They calculated the number of patients needed to treat 1 recurrent VTE in each of the apixaban arms. And they found that number was 14 patients per year with both doses of the drug.

The team also calculated the number of patients needed to inflict harm, in the form of 1 major or clinically relevant, non-major bleeding event. And they found that number was 200 patients per year in the 2.5-mg arm and 63 patients per year in the 5-mg arm.

In closing, Dr Agnelli said these results support the use of apixaban as long-term thromboprophylaxis in patients with a prior VTE.

“And, as a matter of speculation, we do believe that, given the similar efficacy and the possibility of less clinically relevant non-major bleeding, the dose of 2.5 mg of apixaban would be preferred by the clinician,” he added. ![]()

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

ATLANTA—Due to results of the AMPLIFY-EXTENSION study, researchers are recommending a new indication for apixaban: long-term use to prevent recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Study investigators compared 12 months of treatment with apixaban at 2 doses—2.5 mg and 5 mg—to placebo in patients who had previously received anticoagulant therapy for 6 to 12 months to treat a prior VTE.

The team found that both doses of apixaban effectively prevented VTE, VTE-related events, and death. And the incidence of bleeding events was low in all treatment arms.

“We believe that the study, given the results we achieved, should support the use of apixaban for the extended treatment of VTE,” said Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, of the University of Perugia in Italy.

Dr Agnelli presented these results in the late-breaking abstract session (LBA-1) of the 54th ASH Annual Meeting, which took place here December 8-11.

More detailed results of the study—which was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer, joint developers of apixaban—have been published in NEJM.

Dr Agnelli noted that apixaban has proven effective as VTE prophylaxis when given at 2.5 mg after hip or knee replacement surgery. And the drug has been administered at 5 mg as stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.

So he and his colleagues wanted to determine if apixaban might be effective as long-term VTE prophylaxis in patients with a previous thrombotic event, as well as which dose might be optimal for these patients.

To find out, the researchers enrolled 2482 patients with a prior VTE who had completed 6 to 12 months of oral anticoagulant treatment without VTE recurrence or bleeding.

The team randomized 840 patients to receive apixaban at 2.5 mg BID, 813 patients to receive the drug at 5 mg BID, and 829 patients to receive placebo.

The patients were well-matched according age, gender, weight, initial diagnosis, and VTE clinical presentation. They received treatment for 12 months, after which they were followed for 30 days.

Efficacy data

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was recurrent VTE or all-cause death. During the 12-month active study period, these events occurred in 32 patients (3.8%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 34 patients (4.2%) in the 5-mg arm, and 96 patients (11.6%) in the placebo arm. Both apixaban doses were significantly superior to placebo (P<0.001).

The researchers also calculated the incidence of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death. And these events occurred in 14 patients (1.7%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 14 patients (1.7%) in the 5-mg arm, and 73 patients (8.8%) in the placebo arm. Both apixaban doses were significantly superior to placebo (P<0.001).

A third composite endpoint consisted of recurrent VTE, VTE-related death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular-related death. This endpoint was met by 18 patients (2.1%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 19 patients (2.3%) in the 5-mg arm, and 83 patients (10.0%) in the placebo arm.

Overall, both doses of apixaban reduced the risk of fatal and non-fatal recurrent venous thromboembolism by 80%, Dr Agnelli said.

Events during follow-up

During the 30-day follow-up period, symptomatic, recurrent VTE occurred in 2 patients (0.2%) who had received placebo, 3 patients (0.4%) who had received apixaban at 2.5 mg, and 5 patients (0.6%) who had received apixaban at 5 mg.

The composite outcome of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death related to cardiovascular disease occurred in 2 patients: 1 who had received the lower dose of apixaban and 1 who received the higher dose.

Safety data

The study’s primary safety endpoint was major bleeding. In the 2.5-mg arm, 2 patients (0.2%) experienced major bleeding events, both of which were intraocular bleeds.

One patient (0.1%) in the 5-mg arm experienced a major gastrointestinal bleed. And 4 patients (0.5%) in the placebo arm experienced major bleeding events, including 1 intraocular bleed, 1 stroke, 1 urogenital bleed, and 1 gastrointestinal bleed.

A secondary endpoint was clinically relevant, non-major bleeding. This occurred in 25 patients (3.0%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 34 patients (4.2%) in the 5-mg arm, and 19 patients (2.3%) in the placebo arm.

Dr Agnelli and his colleagues also combined the major bleeding data and the clinically relevant, non-major bleeding data. So 27 patients (3.2%) in the 2.5-mg arm had a bleeding event of either kind, as did 35 patients (4.3%) in the 5-mg arm and 22 patients (2.7%) in the placebo arm.

Clinical interpretation

Finally, the researchers tried to put this data into a clinical context. They calculated the number of patients needed to treat 1 recurrent VTE in each of the apixaban arms. And they found that number was 14 patients per year with both doses of the drug.

The team also calculated the number of patients needed to inflict harm, in the form of 1 major or clinically relevant, non-major bleeding event. And they found that number was 200 patients per year in the 2.5-mg arm and 63 patients per year in the 5-mg arm.

In closing, Dr Agnelli said these results support the use of apixaban as long-term thromboprophylaxis in patients with a prior VTE.

“And, as a matter of speculation, we do believe that, given the similar efficacy and the possibility of less clinically relevant non-major bleeding, the dose of 2.5 mg of apixaban would be preferred by the clinician,” he added. ![]()

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

ATLANTA—Due to results of the AMPLIFY-EXTENSION study, researchers are recommending a new indication for apixaban: long-term use to prevent recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Study investigators compared 12 months of treatment with apixaban at 2 doses—2.5 mg and 5 mg—to placebo in patients who had previously received anticoagulant therapy for 6 to 12 months to treat a prior VTE.

The team found that both doses of apixaban effectively prevented VTE, VTE-related events, and death. And the incidence of bleeding events was low in all treatment arms.

“We believe that the study, given the results we achieved, should support the use of apixaban for the extended treatment of VTE,” said Giancarlo Agnelli, MD, of the University of Perugia in Italy.

Dr Agnelli presented these results in the late-breaking abstract session (LBA-1) of the 54th ASH Annual Meeting, which took place here December 8-11.

More detailed results of the study—which was funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer, joint developers of apixaban—have been published in NEJM.

Dr Agnelli noted that apixaban has proven effective as VTE prophylaxis when given at 2.5 mg after hip or knee replacement surgery. And the drug has been administered at 5 mg as stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation.

So he and his colleagues wanted to determine if apixaban might be effective as long-term VTE prophylaxis in patients with a previous thrombotic event, as well as which dose might be optimal for these patients.

To find out, the researchers enrolled 2482 patients with a prior VTE who had completed 6 to 12 months of oral anticoagulant treatment without VTE recurrence or bleeding.

The team randomized 840 patients to receive apixaban at 2.5 mg BID, 813 patients to receive the drug at 5 mg BID, and 829 patients to receive placebo.

The patients were well-matched according age, gender, weight, initial diagnosis, and VTE clinical presentation. They received treatment for 12 months, after which they were followed for 30 days.

Efficacy data

The study’s primary efficacy endpoint was recurrent VTE or all-cause death. During the 12-month active study period, these events occurred in 32 patients (3.8%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 34 patients (4.2%) in the 5-mg arm, and 96 patients (11.6%) in the placebo arm. Both apixaban doses were significantly superior to placebo (P<0.001).

The researchers also calculated the incidence of recurrent VTE or VTE-related death. And these events occurred in 14 patients (1.7%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 14 patients (1.7%) in the 5-mg arm, and 73 patients (8.8%) in the placebo arm. Both apixaban doses were significantly superior to placebo (P<0.001).

A third composite endpoint consisted of recurrent VTE, VTE-related death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular-related death. This endpoint was met by 18 patients (2.1%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 19 patients (2.3%) in the 5-mg arm, and 83 patients (10.0%) in the placebo arm.

Overall, both doses of apixaban reduced the risk of fatal and non-fatal recurrent venous thromboembolism by 80%, Dr Agnelli said.

Events during follow-up

During the 30-day follow-up period, symptomatic, recurrent VTE occurred in 2 patients (0.2%) who had received placebo, 3 patients (0.4%) who had received apixaban at 2.5 mg, and 5 patients (0.6%) who had received apixaban at 5 mg.

The composite outcome of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death related to cardiovascular disease occurred in 2 patients: 1 who had received the lower dose of apixaban and 1 who received the higher dose.

Safety data

The study’s primary safety endpoint was major bleeding. In the 2.5-mg arm, 2 patients (0.2%) experienced major bleeding events, both of which were intraocular bleeds.

One patient (0.1%) in the 5-mg arm experienced a major gastrointestinal bleed. And 4 patients (0.5%) in the placebo arm experienced major bleeding events, including 1 intraocular bleed, 1 stroke, 1 urogenital bleed, and 1 gastrointestinal bleed.

A secondary endpoint was clinically relevant, non-major bleeding. This occurred in 25 patients (3.0%) in the 2.5-mg arm, 34 patients (4.2%) in the 5-mg arm, and 19 patients (2.3%) in the placebo arm.

Dr Agnelli and his colleagues also combined the major bleeding data and the clinically relevant, non-major bleeding data. So 27 patients (3.2%) in the 2.5-mg arm had a bleeding event of either kind, as did 35 patients (4.3%) in the 5-mg arm and 22 patients (2.7%) in the placebo arm.

Clinical interpretation

Finally, the researchers tried to put this data into a clinical context. They calculated the number of patients needed to treat 1 recurrent VTE in each of the apixaban arms. And they found that number was 14 patients per year with both doses of the drug.

The team also calculated the number of patients needed to inflict harm, in the form of 1 major or clinically relevant, non-major bleeding event. And they found that number was 200 patients per year in the 2.5-mg arm and 63 patients per year in the 5-mg arm.

In closing, Dr Agnelli said these results support the use of apixaban as long-term thromboprophylaxis in patients with a prior VTE.

“And, as a matter of speculation, we do believe that, given the similar efficacy and the possibility of less clinically relevant non-major bleeding, the dose of 2.5 mg of apixaban would be preferred by the clinician,” he added. ![]()

Interferon plus entecavir may tame chronic HBV

BOSTON – Adding pegylated interferon alfa-2a to entecavir increased the likelihood of long-term viral suppression of chronic hepatitis B infections in a randomized trial of 160 patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infections.

Loss of the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B viral (HBV) DNA levels below 200 IU/mL after 48 weeks of therapy occurred in 18% of patients who were randomized to entecavir (Baraclude) and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys), compared with 8% of patients on entecavir monotherapy, but this difference was not significant, Dr. Milan J. Sonneveld reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

However, after adjustment for baseline HBV serum antigen levels, analysis showed that pegylated interferon alfa-2a (PEG IFN) as an add-on was independently associated with response at 48 weeks (P = .01).

"Adding peginterferon alfa-2a to a potent nucleoside analogue appears to be a possibility to increase the probability of finite treatment in e-antigen–positive chronic hepatitis B patients," said Dr. Sonneveld of the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Investigators at 15 sites in Europe and China enrolled 184 patients with HBeAg-positive infections with compensated liver disease. The patients were randomized to either entecavir alone at a dose of 0.5 mg daily for 48 weeks, or 24 weeks of entecavir monotherapy, after which 24 weeks of PEG IFN alfa-2a 180 mcg weekly were added.

All patients were assessed at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 48. Those with a response – a loss of the HBeAg with HBV DNA less than 200 IU/mL at 48 weeks – received an additional 24 weeks of consolidation therapy with entecavir and then discontinued therapy, whereas those without a response were continued on entecavir through week 72.

At week 48, there were 77 patients assigned to entecavir and PEG IFN and 83 assigned to entecavir alone.

There were no significant differences in response rates between the treatment arms, but patients who received the PEG IFN add-on had a greater decline of HBV DNA (6.33 vs. 5.91 log IU/mL; P = .05), HBeAg (1.99 vs. 1.56 log IU/mL; P = .01) and HBV serum antigen (0.84 vs. 0.32 log IU/mL; P less than .001) at week 48.

HBV serum antigen clearance was seen in only one patient at week 48; he had been assigned to the PEG IFN add-on group.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for differences in baseline serum antigen levels, the addition of PEG IFN was independently associated with response at week 48 (adjusted odds ratio, 3.78; P = .012).

There were no differences in anemia between the two groups, but patients on the entecavir plus PEG IFN combination had significantly more leukopenia (8% vs. 0%; P = .01), neutropenia (23% vs. 0%; P = .001), and thrombocytopenia (P = .01).

The study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb, which manufactures entecavir, and Roche, which manufactures pegylated interferon alfa-2a. Dr. Sonneveld reported receiving speakers fees and educational support from Roche.

BOSTON – Adding pegylated interferon alfa-2a to entecavir increased the likelihood of long-term viral suppression of chronic hepatitis B infections in a randomized trial of 160 patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infections.

Loss of the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B viral (HBV) DNA levels below 200 IU/mL after 48 weeks of therapy occurred in 18% of patients who were randomized to entecavir (Baraclude) and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys), compared with 8% of patients on entecavir monotherapy, but this difference was not significant, Dr. Milan J. Sonneveld reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

However, after adjustment for baseline HBV serum antigen levels, analysis showed that pegylated interferon alfa-2a (PEG IFN) as an add-on was independently associated with response at 48 weeks (P = .01).

"Adding peginterferon alfa-2a to a potent nucleoside analogue appears to be a possibility to increase the probability of finite treatment in e-antigen–positive chronic hepatitis B patients," said Dr. Sonneveld of the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Investigators at 15 sites in Europe and China enrolled 184 patients with HBeAg-positive infections with compensated liver disease. The patients were randomized to either entecavir alone at a dose of 0.5 mg daily for 48 weeks, or 24 weeks of entecavir monotherapy, after which 24 weeks of PEG IFN alfa-2a 180 mcg weekly were added.

All patients were assessed at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 48. Those with a response – a loss of the HBeAg with HBV DNA less than 200 IU/mL at 48 weeks – received an additional 24 weeks of consolidation therapy with entecavir and then discontinued therapy, whereas those without a response were continued on entecavir through week 72.

At week 48, there were 77 patients assigned to entecavir and PEG IFN and 83 assigned to entecavir alone.

There were no significant differences in response rates between the treatment arms, but patients who received the PEG IFN add-on had a greater decline of HBV DNA (6.33 vs. 5.91 log IU/mL; P = .05), HBeAg (1.99 vs. 1.56 log IU/mL; P = .01) and HBV serum antigen (0.84 vs. 0.32 log IU/mL; P less than .001) at week 48.

HBV serum antigen clearance was seen in only one patient at week 48; he had been assigned to the PEG IFN add-on group.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for differences in baseline serum antigen levels, the addition of PEG IFN was independently associated with response at week 48 (adjusted odds ratio, 3.78; P = .012).

There were no differences in anemia between the two groups, but patients on the entecavir plus PEG IFN combination had significantly more leukopenia (8% vs. 0%; P = .01), neutropenia (23% vs. 0%; P = .001), and thrombocytopenia (P = .01).

The study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb, which manufactures entecavir, and Roche, which manufactures pegylated interferon alfa-2a. Dr. Sonneveld reported receiving speakers fees and educational support from Roche.

BOSTON – Adding pegylated interferon alfa-2a to entecavir increased the likelihood of long-term viral suppression of chronic hepatitis B infections in a randomized trial of 160 patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infections.

Loss of the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B viral (HBV) DNA levels below 200 IU/mL after 48 weeks of therapy occurred in 18% of patients who were randomized to entecavir (Baraclude) and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys), compared with 8% of patients on entecavir monotherapy, but this difference was not significant, Dr. Milan J. Sonneveld reported at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

However, after adjustment for baseline HBV serum antigen levels, analysis showed that pegylated interferon alfa-2a (PEG IFN) as an add-on was independently associated with response at 48 weeks (P = .01).

"Adding peginterferon alfa-2a to a potent nucleoside analogue appears to be a possibility to increase the probability of finite treatment in e-antigen–positive chronic hepatitis B patients," said Dr. Sonneveld of the department of gastroenterology and hepatology at Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Investigators at 15 sites in Europe and China enrolled 184 patients with HBeAg-positive infections with compensated liver disease. The patients were randomized to either entecavir alone at a dose of 0.5 mg daily for 48 weeks, or 24 weeks of entecavir monotherapy, after which 24 weeks of PEG IFN alfa-2a 180 mcg weekly were added.

All patients were assessed at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 48. Those with a response – a loss of the HBeAg with HBV DNA less than 200 IU/mL at 48 weeks – received an additional 24 weeks of consolidation therapy with entecavir and then discontinued therapy, whereas those without a response were continued on entecavir through week 72.

At week 48, there were 77 patients assigned to entecavir and PEG IFN and 83 assigned to entecavir alone.

There were no significant differences in response rates between the treatment arms, but patients who received the PEG IFN add-on had a greater decline of HBV DNA (6.33 vs. 5.91 log IU/mL; P = .05), HBeAg (1.99 vs. 1.56 log IU/mL; P = .01) and HBV serum antigen (0.84 vs. 0.32 log IU/mL; P less than .001) at week 48.

HBV serum antigen clearance was seen in only one patient at week 48; he had been assigned to the PEG IFN add-on group.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for differences in baseline serum antigen levels, the addition of PEG IFN was independently associated with response at week 48 (adjusted odds ratio, 3.78; P = .012).

There were no differences in anemia between the two groups, but patients on the entecavir plus PEG IFN combination had significantly more leukopenia (8% vs. 0%; P = .01), neutropenia (23% vs. 0%; P = .001), and thrombocytopenia (P = .01).

The study was supported by Bristol-Myers Squibb, which manufactures entecavir, and Roche, which manufactures pegylated interferon alfa-2a. Dr. Sonneveld reported receiving speakers fees and educational support from Roche.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE STUDY OF LIVER DISEASES

Major Finding: Patients with chronic hepatitis B who were treated with entecavir and pegylated interferon alfa-2a had a greater decline in HBV DNA (6.33 vs. 5.91 log IU/mL; P = .05) and hepatitis B e antigen (1.99 vs. 1.56 log IU/mL; P = .01) at week 48 than patients on entecavir alone.