User login

New interferon gene identified

A newly identified interferon gene known as IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus, results from a novel study demonstrated.

In an article published online Jan. 6 in Nature Genetics, the results of the study suggest that therapeutic inhibition of IFNL4 "might represent a novel biological strategy for the treatment of HCV and HBV infection and possibly other diseases, and IFNL4 genotype could be used to select patients for this therapy," wrote Ludmila Prokunina-Olsson, Ph.D., and her colleagues.

They described IFNL4 as "related to but distinct from known IFNs and other class 2 cytokines. The 179 amino acid open reading frame of the IFNL4 transcript is created by a common deletion frameshift allele of ss469415590, which is a dinucleotide variant strongly linked with rs12979860" – a genetic marker strongly associated with HCV clearance. The gene is located upstream of IFNL3 on chromosome 19q13.13.

Dr. Prokunina-Olsson, of the Laboratory of Translational Genomics in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute, and her associates performed the RNA sequencing experiment in a sample of primary human hepatocytes treated with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid, a synthetic mimic of double-stranded HCV RNA. The sample was taken from a liver donor who was heterozygous for rs12979860 and uninfected with HCV (Nature Genetics 2013 Jan. 6 [doi: 10.1038/ng.2521]).

The researchers found that compared with rs12979860, ss469415590 was more strongly associated with HCV clearance in individuals of African ancestry (P = .015), while these variants behaved similarly in individuals of European ancestry.

They also discovered that IFNL4 "induces STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation, activates ISRE-Luc reporter and ISGs, and generates antiviral response in hepatoma cells," they wrote. "The mechanisms by which IFNL4 induces these responses but nevertheless impairs HCV clearance are currently under investigation."

The study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases.

A newly identified interferon gene known as IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus, results from a novel study demonstrated.

In an article published online Jan. 6 in Nature Genetics, the results of the study suggest that therapeutic inhibition of IFNL4 "might represent a novel biological strategy for the treatment of HCV and HBV infection and possibly other diseases, and IFNL4 genotype could be used to select patients for this therapy," wrote Ludmila Prokunina-Olsson, Ph.D., and her colleagues.

They described IFNL4 as "related to but distinct from known IFNs and other class 2 cytokines. The 179 amino acid open reading frame of the IFNL4 transcript is created by a common deletion frameshift allele of ss469415590, which is a dinucleotide variant strongly linked with rs12979860" – a genetic marker strongly associated with HCV clearance. The gene is located upstream of IFNL3 on chromosome 19q13.13.

Dr. Prokunina-Olsson, of the Laboratory of Translational Genomics in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute, and her associates performed the RNA sequencing experiment in a sample of primary human hepatocytes treated with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid, a synthetic mimic of double-stranded HCV RNA. The sample was taken from a liver donor who was heterozygous for rs12979860 and uninfected with HCV (Nature Genetics 2013 Jan. 6 [doi: 10.1038/ng.2521]).

The researchers found that compared with rs12979860, ss469415590 was more strongly associated with HCV clearance in individuals of African ancestry (P = .015), while these variants behaved similarly in individuals of European ancestry.

They also discovered that IFNL4 "induces STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation, activates ISRE-Luc reporter and ISGs, and generates antiviral response in hepatoma cells," they wrote. "The mechanisms by which IFNL4 induces these responses but nevertheless impairs HCV clearance are currently under investigation."

The study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases.

A newly identified interferon gene known as IFNL4 is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus, results from a novel study demonstrated.

In an article published online Jan. 6 in Nature Genetics, the results of the study suggest that therapeutic inhibition of IFNL4 "might represent a novel biological strategy for the treatment of HCV and HBV infection and possibly other diseases, and IFNL4 genotype could be used to select patients for this therapy," wrote Ludmila Prokunina-Olsson, Ph.D., and her colleagues.

They described IFNL4 as "related to but distinct from known IFNs and other class 2 cytokines. The 179 amino acid open reading frame of the IFNL4 transcript is created by a common deletion frameshift allele of ss469415590, which is a dinucleotide variant strongly linked with rs12979860" – a genetic marker strongly associated with HCV clearance. The gene is located upstream of IFNL3 on chromosome 19q13.13.

Dr. Prokunina-Olsson, of the Laboratory of Translational Genomics in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute, and her associates performed the RNA sequencing experiment in a sample of primary human hepatocytes treated with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid, a synthetic mimic of double-stranded HCV RNA. The sample was taken from a liver donor who was heterozygous for rs12979860 and uninfected with HCV (Nature Genetics 2013 Jan. 6 [doi: 10.1038/ng.2521]).

The researchers found that compared with rs12979860, ss469415590 was more strongly associated with HCV clearance in individuals of African ancestry (P = .015), while these variants behaved similarly in individuals of European ancestry.

They also discovered that IFNL4 "induces STAT1 and STAT2 phosphorylation, activates ISRE-Luc reporter and ISGs, and generates antiviral response in hepatoma cells," they wrote. "The mechanisms by which IFNL4 induces these responses but nevertheless impairs HCV clearance are currently under investigation."

The study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases.

FROM NATURE GENETICS

Major Finding: Upstream of IFNL3 on chromosome 19q13.13, researchers located a new interferon gene, IFNL4, which is associated with impaired clearance of hepatitis C virus.

Data Source: A study of primary human hepatocytes that were activated with synthetic double-stranded RNA to mimic HCV infection.

Disclosures: The study was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases.

Cyclosporine no more effective than infliximab for ulcerative colitis

Cyclosporine was no more effective than infliximab in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids, according to an open-label, randomized controlled trial of 115 patients.

However, the authors, led by Dr. David Laharie of the hepatology and gastroenterology service at Bordeaux (France) Hospital Center, said that their findings should be interpreted with caution because of the sample size. They added that treatment choice should be guided by physician and center experience.

As many as 40% of patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis who are admitted to the hospital are resistant to intravenous corticosteroids. For these patients, two drugs, cyclosporine or infliximab, have been used as rescue drugs to avoid colectomy.

Meanwhile, there haven’t been many studies comparing the two drugs. A 2012 systematic review of studies on cyclosporine and infliximab showed that the two were comparable, but randomized trials were needed, the review authors noted (Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2012 Nov. 1 [Epub ahead of print]). The current study, according to Dr. Laharie and his colleagues, is the first randomized trial to address the issue (Lancet 2012;380:1909-15).

For the 98-day open-label study, researchers randomized 115 patients to cyclosporine (58 patients) or infliximab (57). The patients were admitted for acute severe flare of ulcerative colitis (Lichtiger score greater than 10 points) to one of the 27 European centers participating in the study between June 1, 2007, and Aug. 31, 2010. They were 18 years or older (mean, 37.5 years), and had never received cyclosporine or infliximab. Contraception during the trial and for 3 months after was mandatory for patients of childbearing age.

The primary endpoint was treatment failure at any time, including absence of clinical response on day 7, relapse between day 7 and day 98, absence of steroid-free remission at day 98, or a severe adverse event leading to interruption of treatment, colectomy, or death. The secondary endpoints included clinical response at day 7, time to clinical response, mucosal healing at day 98, colectomy-free survival, and safety.

Treatment failed in 35 patients (60%) who were receiving cyclosporine, and in 31 patients (54%) who were given infliximab (absolute risk difference of 6%, P = .52). There were no significant differences between the two groups’ suboutcomes, such as responses at day 7 and colectomy rates at day 98. Both drugs were well tolerated, and there were no serious infections or deaths during the trial period.

The authors noted several limitations of the study. Treatment assignments were open label. The use of composite criteria as a primary outcome, rather than colectomy alone, "probably restricted the effect of unmasking on therapeutic decisions," they wrote. Also, the study was powered to detect a large difference between the effect of the two drugs. In addition, they said that because of the sample size, the study’s findings needed to be interpreted with caution.

The authors listed disclosures with several companies, including Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, and Ferring, but they said that no commercial entity had any role in the study, and that the funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

Cyclosporine was no more effective than infliximab in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids, according to an open-label, randomized controlled trial of 115 patients.

However, the authors, led by Dr. David Laharie of the hepatology and gastroenterology service at Bordeaux (France) Hospital Center, said that their findings should be interpreted with caution because of the sample size. They added that treatment choice should be guided by physician and center experience.

As many as 40% of patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis who are admitted to the hospital are resistant to intravenous corticosteroids. For these patients, two drugs, cyclosporine or infliximab, have been used as rescue drugs to avoid colectomy.

Meanwhile, there haven’t been many studies comparing the two drugs. A 2012 systematic review of studies on cyclosporine and infliximab showed that the two were comparable, but randomized trials were needed, the review authors noted (Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2012 Nov. 1 [Epub ahead of print]). The current study, according to Dr. Laharie and his colleagues, is the first randomized trial to address the issue (Lancet 2012;380:1909-15).

For the 98-day open-label study, researchers randomized 115 patients to cyclosporine (58 patients) or infliximab (57). The patients were admitted for acute severe flare of ulcerative colitis (Lichtiger score greater than 10 points) to one of the 27 European centers participating in the study between June 1, 2007, and Aug. 31, 2010. They were 18 years or older (mean, 37.5 years), and had never received cyclosporine or infliximab. Contraception during the trial and for 3 months after was mandatory for patients of childbearing age.

The primary endpoint was treatment failure at any time, including absence of clinical response on day 7, relapse between day 7 and day 98, absence of steroid-free remission at day 98, or a severe adverse event leading to interruption of treatment, colectomy, or death. The secondary endpoints included clinical response at day 7, time to clinical response, mucosal healing at day 98, colectomy-free survival, and safety.

Treatment failed in 35 patients (60%) who were receiving cyclosporine, and in 31 patients (54%) who were given infliximab (absolute risk difference of 6%, P = .52). There were no significant differences between the two groups’ suboutcomes, such as responses at day 7 and colectomy rates at day 98. Both drugs were well tolerated, and there were no serious infections or deaths during the trial period.

The authors noted several limitations of the study. Treatment assignments were open label. The use of composite criteria as a primary outcome, rather than colectomy alone, "probably restricted the effect of unmasking on therapeutic decisions," they wrote. Also, the study was powered to detect a large difference between the effect of the two drugs. In addition, they said that because of the sample size, the study’s findings needed to be interpreted with caution.

The authors listed disclosures with several companies, including Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, and Ferring, but they said that no commercial entity had any role in the study, and that the funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

Cyclosporine was no more effective than infliximab in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis refractory to intravenous steroids, according to an open-label, randomized controlled trial of 115 patients.

However, the authors, led by Dr. David Laharie of the hepatology and gastroenterology service at Bordeaux (France) Hospital Center, said that their findings should be interpreted with caution because of the sample size. They added that treatment choice should be guided by physician and center experience.

As many as 40% of patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis who are admitted to the hospital are resistant to intravenous corticosteroids. For these patients, two drugs, cyclosporine or infliximab, have been used as rescue drugs to avoid colectomy.

Meanwhile, there haven’t been many studies comparing the two drugs. A 2012 systematic review of studies on cyclosporine and infliximab showed that the two were comparable, but randomized trials were needed, the review authors noted (Int. J. Colorectal. Dis. 2012 Nov. 1 [Epub ahead of print]). The current study, according to Dr. Laharie and his colleagues, is the first randomized trial to address the issue (Lancet 2012;380:1909-15).

For the 98-day open-label study, researchers randomized 115 patients to cyclosporine (58 patients) or infliximab (57). The patients were admitted for acute severe flare of ulcerative colitis (Lichtiger score greater than 10 points) to one of the 27 European centers participating in the study between June 1, 2007, and Aug. 31, 2010. They were 18 years or older (mean, 37.5 years), and had never received cyclosporine or infliximab. Contraception during the trial and for 3 months after was mandatory for patients of childbearing age.

The primary endpoint was treatment failure at any time, including absence of clinical response on day 7, relapse between day 7 and day 98, absence of steroid-free remission at day 98, or a severe adverse event leading to interruption of treatment, colectomy, or death. The secondary endpoints included clinical response at day 7, time to clinical response, mucosal healing at day 98, colectomy-free survival, and safety.

Treatment failed in 35 patients (60%) who were receiving cyclosporine, and in 31 patients (54%) who were given infliximab (absolute risk difference of 6%, P = .52). There were no significant differences between the two groups’ suboutcomes, such as responses at day 7 and colectomy rates at day 98. Both drugs were well tolerated, and there were no serious infections or deaths during the trial period.

The authors noted several limitations of the study. Treatment assignments were open label. The use of composite criteria as a primary outcome, rather than colectomy alone, "probably restricted the effect of unmasking on therapeutic decisions," they wrote. Also, the study was powered to detect a large difference between the effect of the two drugs. In addition, they said that because of the sample size, the study’s findings needed to be interpreted with caution.

The authors listed disclosures with several companies, including Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, and Ferring, but they said that no commercial entity had any role in the study, and that the funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

On Twitter @naseemsmiller

FROM THE LANCET

Major Finding: Treatment failed in 60%, or 35 patients who were receiving cyclosporine, and 54%, or 31 patients who were given infliximab (absolute risk difference of 6%, P = 0.52).

Data Source: A 98-day open-label study of 115 patients randomly assigned to cyclosporine (58 patients) or infliximab (57), admitted to one of the 27 European centers participating in the study between June 1, 2007, and Aug. 31, 2010.

Disclosures: The authors listed disclosures with several companies, including Merck Sharp & Dohme, Abbott, and Ferring, but they said that no commercial entity had any role in the study, and that the funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

Vasoactive agents lower mortality in patients with acute variceal bleeds

Clinical question

For patients with acute variceal bleeds, does the use of vasoactive agents improve outcomes?

Bottom line

The use of vasoactive agents such as vasopressin, somatostatin, and octreotide decreases the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with acute variceal bleeding. LOE = 1a-

Reference

Study Design

Meta-analysis (randomized controlled trials)

Funding Source

Self-funded or unfunded

Allocation

Uncertain

Setting

Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

Vasoactive agents such as vasopressin and somatostatin and their analogues (terlipressin, vapreotide and octreotide) are used to treat acute variceal bleeding. These investigators searched EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the EBM Reviews databases to identify randomized controlled trials that compared the intravenous use of these vasoactive agents with each other or with placebo in adults presenting with variceal bleeding. Two investigators independently selected the studies, abstracted data, and assessed study quality. The final selection included 30 studies that compared vasoactive medications with placebo (n = 3111) and 27 studies that compared different vasoactive agents with each other (n = 2293). Moderate-quality evidence showed that vasoactive agents decreased 7-day mortality risk compared with placebo or routine medical management (relative risk = 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; P = .02). There was also evidence of decreased risk of rebleeding, decreased transfusion requirements, and shorter hospital stays with the use of vasoactive agents although the quality of this evidence was low to moderate. For the studies comparing different agents with each other, there was no difference in mortality detected.

Clinical question

For patients with acute variceal bleeds, does the use of vasoactive agents improve outcomes?

Bottom line

The use of vasoactive agents such as vasopressin, somatostatin, and octreotide decreases the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with acute variceal bleeding. LOE = 1a-

Reference

Study Design

Meta-analysis (randomized controlled trials)

Funding Source

Self-funded or unfunded

Allocation

Uncertain

Setting

Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

Vasoactive agents such as vasopressin and somatostatin and their analogues (terlipressin, vapreotide and octreotide) are used to treat acute variceal bleeding. These investigators searched EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the EBM Reviews databases to identify randomized controlled trials that compared the intravenous use of these vasoactive agents with each other or with placebo in adults presenting with variceal bleeding. Two investigators independently selected the studies, abstracted data, and assessed study quality. The final selection included 30 studies that compared vasoactive medications with placebo (n = 3111) and 27 studies that compared different vasoactive agents with each other (n = 2293). Moderate-quality evidence showed that vasoactive agents decreased 7-day mortality risk compared with placebo or routine medical management (relative risk = 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; P = .02). There was also evidence of decreased risk of rebleeding, decreased transfusion requirements, and shorter hospital stays with the use of vasoactive agents although the quality of this evidence was low to moderate. For the studies comparing different agents with each other, there was no difference in mortality detected.

Clinical question

For patients with acute variceal bleeds, does the use of vasoactive agents improve outcomes?

Bottom line

The use of vasoactive agents such as vasopressin, somatostatin, and octreotide decreases the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with acute variceal bleeding. LOE = 1a-

Reference

Study Design

Meta-analysis (randomized controlled trials)

Funding Source

Self-funded or unfunded

Allocation

Uncertain

Setting

Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

Vasoactive agents such as vasopressin and somatostatin and their analogues (terlipressin, vapreotide and octreotide) are used to treat acute variceal bleeding. These investigators searched EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the EBM Reviews databases to identify randomized controlled trials that compared the intravenous use of these vasoactive agents with each other or with placebo in adults presenting with variceal bleeding. Two investigators independently selected the studies, abstracted data, and assessed study quality. The final selection included 30 studies that compared vasoactive medications with placebo (n = 3111) and 27 studies that compared different vasoactive agents with each other (n = 2293). Moderate-quality evidence showed that vasoactive agents decreased 7-day mortality risk compared with placebo or routine medical management (relative risk = 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57-0.95; P = .02). There was also evidence of decreased risk of rebleeding, decreased transfusion requirements, and shorter hospital stays with the use of vasoactive agents although the quality of this evidence was low to moderate. For the studies comparing different agents with each other, there was no difference in mortality detected.

CABG superior to PCI in diabetics with multivessel CAD (FREEDOM)

Clinical question

For patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease, which revascularization strategy provides better outcomes?

Bottom line

Revascularization using coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), as compared with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), significantly reduces long-term mortality as well as decreases the rate of myocardial infarctions in diabetic patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD). The number needed to treat is 13. Of note, patients who undergo CABG are more likely to have a stroke, but this occurs mostly during the 30-day period following the procedure. LOE = 1b-

Reference

Study Design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding Source

Industry + govt

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

Using concealed allocation, these investigators enrolled 1900 patients with diabetes and multivessel CAD to receive either PCI with drug-eluting stents or CABG surgery. Most enrolled patients were men, had a mean age of 63 years, and 83% of the total group had evidence of 3-vessel disease. The use of appropriate cardiac medications, including statins and beta-blockers, was similar in the 2 groups, although patients in the PCI group were more likely to receive thienopyridines such as clopidogrel after 5 years of follow-up. Analysis was by intention to treat. Five years after revascularization, the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was more likely in the PCI group than in the CABG group (26.6% vs 18.7%; P = .005). This was due to increased rates of death and myocardial infarction in the PCI group (for death: 16.3% vs 10.9%; P = .049; for MI: 13.9% vs 6%; P < .001). The CABG group did, however, have a higher rate of stroke at 5 years (5.2% vs 2.4%; P = .03). The majority of these strokes occurred during the first 30 days following revascularization.

Clinical question

For patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease, which revascularization strategy provides better outcomes?

Bottom line

Revascularization using coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), as compared with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), significantly reduces long-term mortality as well as decreases the rate of myocardial infarctions in diabetic patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD). The number needed to treat is 13. Of note, patients who undergo CABG are more likely to have a stroke, but this occurs mostly during the 30-day period following the procedure. LOE = 1b-

Reference

Study Design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding Source

Industry + govt

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

Using concealed allocation, these investigators enrolled 1900 patients with diabetes and multivessel CAD to receive either PCI with drug-eluting stents or CABG surgery. Most enrolled patients were men, had a mean age of 63 years, and 83% of the total group had evidence of 3-vessel disease. The use of appropriate cardiac medications, including statins and beta-blockers, was similar in the 2 groups, although patients in the PCI group were more likely to receive thienopyridines such as clopidogrel after 5 years of follow-up. Analysis was by intention to treat. Five years after revascularization, the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was more likely in the PCI group than in the CABG group (26.6% vs 18.7%; P = .005). This was due to increased rates of death and myocardial infarction in the PCI group (for death: 16.3% vs 10.9%; P = .049; for MI: 13.9% vs 6%; P < .001). The CABG group did, however, have a higher rate of stroke at 5 years (5.2% vs 2.4%; P = .03). The majority of these strokes occurred during the first 30 days following revascularization.

Clinical question

For patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease, which revascularization strategy provides better outcomes?

Bottom line

Revascularization using coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), as compared with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), significantly reduces long-term mortality as well as decreases the rate of myocardial infarctions in diabetic patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD). The number needed to treat is 13. Of note, patients who undergo CABG are more likely to have a stroke, but this occurs mostly during the 30-day period following the procedure. LOE = 1b-

Reference

Study Design

Randomized controlled trial (nonblinded)

Funding Source

Industry + govt

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location)

Synopsis

Using concealed allocation, these investigators enrolled 1900 patients with diabetes and multivessel CAD to receive either PCI with drug-eluting stents or CABG surgery. Most enrolled patients were men, had a mean age of 63 years, and 83% of the total group had evidence of 3-vessel disease. The use of appropriate cardiac medications, including statins and beta-blockers, was similar in the 2 groups, although patients in the PCI group were more likely to receive thienopyridines such as clopidogrel after 5 years of follow-up. Analysis was by intention to treat. Five years after revascularization, the primary composite outcome of all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke was more likely in the PCI group than in the CABG group (26.6% vs 18.7%; P = .005). This was due to increased rates of death and myocardial infarction in the PCI group (for death: 16.3% vs 10.9%; P = .049; for MI: 13.9% vs 6%; P < .001). The CABG group did, however, have a higher rate of stroke at 5 years (5.2% vs 2.4%; P = .03). The majority of these strokes occurred during the first 30 days following revascularization.

Futility rules defined for telaprevir-based HCV therapy

Therapy with telaprevir, peginterferon, and ribavirin should be stopped in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus infection if HCV RNA levels are greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 or 12 of treatment, according to new futility rules developed using phase II and III trial data.

The rules are important for preventing needless drug exposure and to minimize the development of drug-resistant variants in patients with little or no chance of achieving sustained virologic response, reported Dr. Nathalie Adda of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cambridge, Mass., and her colleagues.

The futility rules were initially developed during clinical trials of telaprevir combination therapy and were instituted along with standard peginterferon/ribavirin (Peg-IFN/RBV) futility rules; phase II trial data were analyzed to determine whether the telaprevir rules could differentiate patients likely to experience viral breakthrough and patients likely to achieve sustained virologic response, and it was found that the majority of viral breakthroughs occurred within the first 4 weeks of treatment. Thus, a futility rule was implemented at week 4 in studies of telaprevir combination therapy as has long been the case for studies of Peg-IFN/RBV therapy (Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012 Nov. 16 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.045]).

For treatment-naive patients, a level of 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 was used; for treatment-experienced patients, a more conservative level of 100 IU/mL at week 4 (and at weeks 6 and 8) was used.

These rules were further analyzed based on phase III studies of patients who were treated with 12 weeks of telaprevir, Peg-IFN/RBV followed by 12 or 36 weeks of Peg-IFN/RBV alone. This allowed for refinement of the optimal thresholds and time points for identifying patients unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response.

"In this analysis, we also sought to harmonize the futility rules for all patient populations (treatment-naive and -experienced)," the investigators wrote.

They found that 1.7% of 844 treatment-naive patients, 0.7% of 138 prior relapsers, and 0% of 46 prior partial responders had HCV RNA levels greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4, compared with 14% of 70 prior nonresponders. None of the 25 patients with HCV RNA levels above the 1,000 IU/mL level at week 4 achieved sustained virologic response with continued therapy. Among those who had HCV RNA levels between 100 and 1,000 IU/mL at week 4, a small subset achieved sustained virologic response with continued treatment: 25% of treatment-naive and 14% of treatment-experienced patients.

The 1,000 IU/mL threshold was retained, as it was found to maximize the likelihood of achieving sustained virologic response, they said.

"Furthermore, 13/14 (93%) treatment-naive and 10/11 (91%) treatment-experienced patients with HCV RNA levels greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 reached their HCV RNA nadir prior to week 4, typically by week 2, with subsequent increase in HCV RNA by week 4, meeting the definition of viral breakthrough," they wrote.

Additionally, the investigators reassessed previously-established Peg-IFN/RBV treatment futility rule of a 2 log10 decrease or greater in HCV RNA at week 12 in the context of a telaprevir-based regimen, and implemented a futility rule for treatment-naive patients of greater than 1,000 IU/mL HCV RNA at the end of the telaprevir dosing period to avoid unnecessary Peg-IFN/RBV exposure in those unlikely to achieve SVR.

This rule was met by 1.5% of 605 treatment naive patients who completed week 12. Similar rules were implemented at weeks 6, 8, and 12 for treatment-experienced patients, but few patients met the week 6 and 8 futility rules (5 and 2 of 266 patients, respectively), and the HCV RNA assessment at these time points was replaced by the week 12 assessment.

"In conclusion, data from phase II and III trials confirmed that a futility rule of greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 accurately and specifically identified patients unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response. Less than 2% of treatment-naive, prior relapse, and prior partial response, and 14% of prior null response patients met the above criterion, and none achieved sustained virologic response after stopping telaprevir, with continued Peg-IFN/RBV," the investigators wrote, noting that the vast majority of these patients were already experiencing viral breakthrough by week 4.

The new rules prevent unnecessary drug exposure in those unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response, and, importantly, they minimize additional HCV RNA testing, because the futility time points coincide with those used to guide total treatment duration.

"This strategy will avoid additional adverse effects of continued treatment and will help minimize the evolution, enrichment, or protracted persistence of resistant variants, which could adversely impact patient candidacy for potential treatment with subsequent antiviral regimens," they concluded.

Several authors are employees of Janssen Pharmaceuticals and stock owners of Johnson and Johnson. One author reported receiving consulting fees, lecture fees, and/or grant/research support from many companies involved in hepatitis C virus therapeutics.

Therapy with telaprevir, peginterferon, and ribavirin should be stopped in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus infection if HCV RNA levels are greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 or 12 of treatment, according to new futility rules developed using phase II and III trial data.

The rules are important for preventing needless drug exposure and to minimize the development of drug-resistant variants in patients with little or no chance of achieving sustained virologic response, reported Dr. Nathalie Adda of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cambridge, Mass., and her colleagues.

The futility rules were initially developed during clinical trials of telaprevir combination therapy and were instituted along with standard peginterferon/ribavirin (Peg-IFN/RBV) futility rules; phase II trial data were analyzed to determine whether the telaprevir rules could differentiate patients likely to experience viral breakthrough and patients likely to achieve sustained virologic response, and it was found that the majority of viral breakthroughs occurred within the first 4 weeks of treatment. Thus, a futility rule was implemented at week 4 in studies of telaprevir combination therapy as has long been the case for studies of Peg-IFN/RBV therapy (Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012 Nov. 16 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.045]).

For treatment-naive patients, a level of 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 was used; for treatment-experienced patients, a more conservative level of 100 IU/mL at week 4 (and at weeks 6 and 8) was used.

These rules were further analyzed based on phase III studies of patients who were treated with 12 weeks of telaprevir, Peg-IFN/RBV followed by 12 or 36 weeks of Peg-IFN/RBV alone. This allowed for refinement of the optimal thresholds and time points for identifying patients unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response.

"In this analysis, we also sought to harmonize the futility rules for all patient populations (treatment-naive and -experienced)," the investigators wrote.

They found that 1.7% of 844 treatment-naive patients, 0.7% of 138 prior relapsers, and 0% of 46 prior partial responders had HCV RNA levels greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4, compared with 14% of 70 prior nonresponders. None of the 25 patients with HCV RNA levels above the 1,000 IU/mL level at week 4 achieved sustained virologic response with continued therapy. Among those who had HCV RNA levels between 100 and 1,000 IU/mL at week 4, a small subset achieved sustained virologic response with continued treatment: 25% of treatment-naive and 14% of treatment-experienced patients.

The 1,000 IU/mL threshold was retained, as it was found to maximize the likelihood of achieving sustained virologic response, they said.

"Furthermore, 13/14 (93%) treatment-naive and 10/11 (91%) treatment-experienced patients with HCV RNA levels greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 reached their HCV RNA nadir prior to week 4, typically by week 2, with subsequent increase in HCV RNA by week 4, meeting the definition of viral breakthrough," they wrote.

Additionally, the investigators reassessed previously-established Peg-IFN/RBV treatment futility rule of a 2 log10 decrease or greater in HCV RNA at week 12 in the context of a telaprevir-based regimen, and implemented a futility rule for treatment-naive patients of greater than 1,000 IU/mL HCV RNA at the end of the telaprevir dosing period to avoid unnecessary Peg-IFN/RBV exposure in those unlikely to achieve SVR.

This rule was met by 1.5% of 605 treatment naive patients who completed week 12. Similar rules were implemented at weeks 6, 8, and 12 for treatment-experienced patients, but few patients met the week 6 and 8 futility rules (5 and 2 of 266 patients, respectively), and the HCV RNA assessment at these time points was replaced by the week 12 assessment.

"In conclusion, data from phase II and III trials confirmed that a futility rule of greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 accurately and specifically identified patients unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response. Less than 2% of treatment-naive, prior relapse, and prior partial response, and 14% of prior null response patients met the above criterion, and none achieved sustained virologic response after stopping telaprevir, with continued Peg-IFN/RBV," the investigators wrote, noting that the vast majority of these patients were already experiencing viral breakthrough by week 4.

The new rules prevent unnecessary drug exposure in those unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response, and, importantly, they minimize additional HCV RNA testing, because the futility time points coincide with those used to guide total treatment duration.

"This strategy will avoid additional adverse effects of continued treatment and will help minimize the evolution, enrichment, or protracted persistence of resistant variants, which could adversely impact patient candidacy for potential treatment with subsequent antiviral regimens," they concluded.

Several authors are employees of Janssen Pharmaceuticals and stock owners of Johnson and Johnson. One author reported receiving consulting fees, lecture fees, and/or grant/research support from many companies involved in hepatitis C virus therapeutics.

Therapy with telaprevir, peginterferon, and ribavirin should be stopped in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients with hepatitis C virus infection if HCV RNA levels are greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 or 12 of treatment, according to new futility rules developed using phase II and III trial data.

The rules are important for preventing needless drug exposure and to minimize the development of drug-resistant variants in patients with little or no chance of achieving sustained virologic response, reported Dr. Nathalie Adda of Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc., Cambridge, Mass., and her colleagues.

The futility rules were initially developed during clinical trials of telaprevir combination therapy and were instituted along with standard peginterferon/ribavirin (Peg-IFN/RBV) futility rules; phase II trial data were analyzed to determine whether the telaprevir rules could differentiate patients likely to experience viral breakthrough and patients likely to achieve sustained virologic response, and it was found that the majority of viral breakthroughs occurred within the first 4 weeks of treatment. Thus, a futility rule was implemented at week 4 in studies of telaprevir combination therapy as has long been the case for studies of Peg-IFN/RBV therapy (Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012 Nov. 16 [doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.045]).

For treatment-naive patients, a level of 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 was used; for treatment-experienced patients, a more conservative level of 100 IU/mL at week 4 (and at weeks 6 and 8) was used.

These rules were further analyzed based on phase III studies of patients who were treated with 12 weeks of telaprevir, Peg-IFN/RBV followed by 12 or 36 weeks of Peg-IFN/RBV alone. This allowed for refinement of the optimal thresholds and time points for identifying patients unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response.

"In this analysis, we also sought to harmonize the futility rules for all patient populations (treatment-naive and -experienced)," the investigators wrote.

They found that 1.7% of 844 treatment-naive patients, 0.7% of 138 prior relapsers, and 0% of 46 prior partial responders had HCV RNA levels greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4, compared with 14% of 70 prior nonresponders. None of the 25 patients with HCV RNA levels above the 1,000 IU/mL level at week 4 achieved sustained virologic response with continued therapy. Among those who had HCV RNA levels between 100 and 1,000 IU/mL at week 4, a small subset achieved sustained virologic response with continued treatment: 25% of treatment-naive and 14% of treatment-experienced patients.

The 1,000 IU/mL threshold was retained, as it was found to maximize the likelihood of achieving sustained virologic response, they said.

"Furthermore, 13/14 (93%) treatment-naive and 10/11 (91%) treatment-experienced patients with HCV RNA levels greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 reached their HCV RNA nadir prior to week 4, typically by week 2, with subsequent increase in HCV RNA by week 4, meeting the definition of viral breakthrough," they wrote.

Additionally, the investigators reassessed previously-established Peg-IFN/RBV treatment futility rule of a 2 log10 decrease or greater in HCV RNA at week 12 in the context of a telaprevir-based regimen, and implemented a futility rule for treatment-naive patients of greater than 1,000 IU/mL HCV RNA at the end of the telaprevir dosing period to avoid unnecessary Peg-IFN/RBV exposure in those unlikely to achieve SVR.

This rule was met by 1.5% of 605 treatment naive patients who completed week 12. Similar rules were implemented at weeks 6, 8, and 12 for treatment-experienced patients, but few patients met the week 6 and 8 futility rules (5 and 2 of 266 patients, respectively), and the HCV RNA assessment at these time points was replaced by the week 12 assessment.

"In conclusion, data from phase II and III trials confirmed that a futility rule of greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 accurately and specifically identified patients unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response. Less than 2% of treatment-naive, prior relapse, and prior partial response, and 14% of prior null response patients met the above criterion, and none achieved sustained virologic response after stopping telaprevir, with continued Peg-IFN/RBV," the investigators wrote, noting that the vast majority of these patients were already experiencing viral breakthrough by week 4.

The new rules prevent unnecessary drug exposure in those unlikely to achieve sustained virologic response, and, importantly, they minimize additional HCV RNA testing, because the futility time points coincide with those used to guide total treatment duration.

"This strategy will avoid additional adverse effects of continued treatment and will help minimize the evolution, enrichment, or protracted persistence of resistant variants, which could adversely impact patient candidacy for potential treatment with subsequent antiviral regimens," they concluded.

Several authors are employees of Janssen Pharmaceuticals and stock owners of Johnson and Johnson. One author reported receiving consulting fees, lecture fees, and/or grant/research support from many companies involved in hepatitis C virus therapeutics.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Major Finding: Telaprevir, peginterferon, and ribavirin for the treatment of hepatitis C should be stopped in both treatment-naive and treatment-experienced patients if HCV RNA levels are greater than 1,000 IU/mL at week 4 or 12 of treatment.

Data Source: A retrospective review of clinical trial data.

Disclosures: Several authors are employees of Janssen Pharmaceuticals and stock owners of Johnson and Johnson. One author reported receiving consulting fees, lecture fees, and/or grant/research support from many companies involved in hepatitis C virus therapeutics.

Practice changes warrant residency reforms

Surgical residency programs have not kept up with radical changes in the practice of surgery over the past two decades, but innovations ranging from curriculum reform to increasing the length of residency could help to improve the overall performance of recent surgical residency graduates, according to an analysis in Annals of Surgery.

"The changes that have occurred have been disruptive to residency training, and to date there has been minimal compensation for these." The changes include not only the 80-hour workweek for surgical residents, but also clinical areas, according to Dr. Lewis, executive director of the American Board of Surgery, and Dr. Klingensmith, residency program director at Washington University in St. Louis ( Ann. Surg. 2012;256:553-9).

The effect of the 80-hour workweek has been a reduction by 6 months to a year of in-hospital experience during 5 years of residency. Most of that reduced time corresponds to night and weekends, when residents would be more likely to see urgent and emergent conditions, and to have a greater degree of independent functioning, autonomy, and indirect supervision, they said.

The effects of this and various technology changes "will undoubtedly continue, and the directions in which surgery will evolve in the future are not predictable," Dr. Lewis and Dr. Klingensmith wrote. They laid out potential ways in which residency programs can address the changes:

• There should be a continuous process to define and continually update the surgical residency curriculum, which needs to keep pace with the fast-changing surgical practice landscape, and to "prune" information related to diseases that no longer are seen frequently in practice.

"The starting point for making changes in residency is to recognize that much of what is being taught is obsolete, and addresses diseases that are no longer a significant problem, or those for which surgical treatment is rarely needed," they said.

• Residency programs should improve the efficacy of resident learning by reducing clerical functions for residents, using physician extenders where appropriate, and utilizing mobile computing technology to deliver "a more defined and comprehensive curriculum to residents at an individual level."

• Educators could make better use of simulators in certain areas..

• There should be earlier specialty focus in residency training for those residents who already know the specialty they would like to pursue.

• Residency should include expanded laparoscopic surgery training.

• Residency programs could increase in length to make up for the time lost to the 80-hour workweek rule. Four-fifths of surgical residents already elect to take a postresidency fellowship in a specialty or subspecialty area,

• Training should expand to include additional skills, such as the use of ultrasound and the use of interventional catheter techniques.

The authors reported no conflicts.

Surgical residency programs have not kept up with radical changes in the practice of surgery over the past two decades, but innovations ranging from curriculum reform to increasing the length of residency could help to improve the overall performance of recent surgical residency graduates, according to an analysis in Annals of Surgery.

"The changes that have occurred have been disruptive to residency training, and to date there has been minimal compensation for these." The changes include not only the 80-hour workweek for surgical residents, but also clinical areas, according to Dr. Lewis, executive director of the American Board of Surgery, and Dr. Klingensmith, residency program director at Washington University in St. Louis ( Ann. Surg. 2012;256:553-9).

The effect of the 80-hour workweek has been a reduction by 6 months to a year of in-hospital experience during 5 years of residency. Most of that reduced time corresponds to night and weekends, when residents would be more likely to see urgent and emergent conditions, and to have a greater degree of independent functioning, autonomy, and indirect supervision, they said.

The effects of this and various technology changes "will undoubtedly continue, and the directions in which surgery will evolve in the future are not predictable," Dr. Lewis and Dr. Klingensmith wrote. They laid out potential ways in which residency programs can address the changes:

• There should be a continuous process to define and continually update the surgical residency curriculum, which needs to keep pace with the fast-changing surgical practice landscape, and to "prune" information related to diseases that no longer are seen frequently in practice.

"The starting point for making changes in residency is to recognize that much of what is being taught is obsolete, and addresses diseases that are no longer a significant problem, or those for which surgical treatment is rarely needed," they said.

• Residency programs should improve the efficacy of resident learning by reducing clerical functions for residents, using physician extenders where appropriate, and utilizing mobile computing technology to deliver "a more defined and comprehensive curriculum to residents at an individual level."

• Educators could make better use of simulators in certain areas..

• There should be earlier specialty focus in residency training for those residents who already know the specialty they would like to pursue.

• Residency should include expanded laparoscopic surgery training.

• Residency programs could increase in length to make up for the time lost to the 80-hour workweek rule. Four-fifths of surgical residents already elect to take a postresidency fellowship in a specialty or subspecialty area,

• Training should expand to include additional skills, such as the use of ultrasound and the use of interventional catheter techniques.

The authors reported no conflicts.

Surgical residency programs have not kept up with radical changes in the practice of surgery over the past two decades, but innovations ranging from curriculum reform to increasing the length of residency could help to improve the overall performance of recent surgical residency graduates, according to an analysis in Annals of Surgery.

"The changes that have occurred have been disruptive to residency training, and to date there has been minimal compensation for these." The changes include not only the 80-hour workweek for surgical residents, but also clinical areas, according to Dr. Lewis, executive director of the American Board of Surgery, and Dr. Klingensmith, residency program director at Washington University in St. Louis ( Ann. Surg. 2012;256:553-9).

The effect of the 80-hour workweek has been a reduction by 6 months to a year of in-hospital experience during 5 years of residency. Most of that reduced time corresponds to night and weekends, when residents would be more likely to see urgent and emergent conditions, and to have a greater degree of independent functioning, autonomy, and indirect supervision, they said.

The effects of this and various technology changes "will undoubtedly continue, and the directions in which surgery will evolve in the future are not predictable," Dr. Lewis and Dr. Klingensmith wrote. They laid out potential ways in which residency programs can address the changes:

• There should be a continuous process to define and continually update the surgical residency curriculum, which needs to keep pace with the fast-changing surgical practice landscape, and to "prune" information related to diseases that no longer are seen frequently in practice.

"The starting point for making changes in residency is to recognize that much of what is being taught is obsolete, and addresses diseases that are no longer a significant problem, or those for which surgical treatment is rarely needed," they said.

• Residency programs should improve the efficacy of resident learning by reducing clerical functions for residents, using physician extenders where appropriate, and utilizing mobile computing technology to deliver "a more defined and comprehensive curriculum to residents at an individual level."

• Educators could make better use of simulators in certain areas..

• There should be earlier specialty focus in residency training for those residents who already know the specialty they would like to pursue.

• Residency should include expanded laparoscopic surgery training.

• Residency programs could increase in length to make up for the time lost to the 80-hour workweek rule. Four-fifths of surgical residents already elect to take a postresidency fellowship in a specialty or subspecialty area,

• Training should expand to include additional skills, such as the use of ultrasound and the use of interventional catheter techniques.

The authors reported no conflicts.

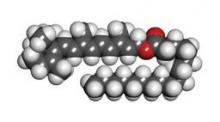

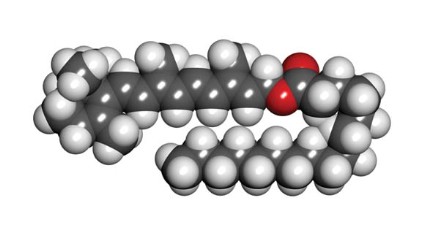

Retinyl palmitate

Retinyl palmitate, a storage and ester form of retinol (vitamin A) and the prevailing type of vitamin A found naturally in the skin (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75), has become increasingly popular during the past 2 decades. It is widely used in more than 600 skin care products, including cosmetics and sunscreens, and, with FDA approval, over-the-counter and prescription drugs (Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). It was also the subject of a controversial summer 2010 report by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in which the organization warned of possible photocarcinogenicity associated with retinyl palmitate (RP)-containing sunscreens.

Although vitamin A storage in the epidermis takes the form of retinyl esters and retinols, they act differently when exposed to UV light. The retinols display UVB-resistant and UVB-sensitive characteristics not exhibited by retinyl esters such as RP (Dermatology 1999;199:302-7). The EWG used "vitamin A" and "retinyl palmitate" interchangeably in their criticisms and follow-ups, which is misleading. The vitamin A family of drugs includes retinyl esters, retinol, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene, and oral isotretinoin (Accutane), in addition to four carotenoids, including beta-carotene, many of which have been shown to prevent or protect against cancer (Br. J. Cancer 1988;57:428-33; Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:949-56; J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981;76:178-80; Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1981;270:453-62). That does not mean that RP prevents cancer just because oral retinol, beta-carotene, or tretinoin have been shown to do so, for example. In fact, the study that the EWG refers to shows evidence that RP may lead to skin tumors in mice.

In response to the EWG report, Wang et al. acknowledged that of the eight in vitro studies published by the Food and Drug Administration from 2002 to 2009, four revealed that reactive oxygen species were produced by RP after UVA exposure (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67; Toxicol. Ind. Health 2007;23:625-31; Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163:30-43; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90; Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:129-38). However, they questioned the relevance of these results in the context of the convoluted mechanisms of the antioxidant setting in human skin. They also contended that the National Toxicology Program (NTP) study on which the EWG based its report failed to prove that the combination of RP and UV results in photocarcinogenesis and, in fact, was rife with reasons for skepticism (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). The EWG offered its own counterarguments and stood by its report. Rather than wade further into the debate that occurred in 2010 and found its way into the pages of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2010;63:903-6), let’s review what is known about RP.

What else do we know about RP?

In 1997, Duell et al. showed that unoccluded retinol is more effective at penetrating human skin in vivo than RP or retinoic acid (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;109:301-5).

In 2003, Antille et al. used an in vitro model to evaluate the photoprotective activity of RP, and then applied topical RP on the back of hairless mice before exposing them to UVB. They also applied topical RP or a sunscreen on the buttocks of human volunteers before exposing them to four minimal erythema doses of UVB. The investigators found that RP was as efficient in vitro as the commercial filter octylmethoxycinnamate in preventing UVB-induced fluorescence or photobleaching of fluorescent markers. Topical RP also significantly suppressed the formation of thymine dimers in mouse epidermis and human skin. In the volunteers, topical RP was as efficient as an SPF (sun protection factor) 20 sunscreen in preventing sunburn erythema (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1163-7).

In 2005, Yan et al. studied the phototoxicity of RP, anhydroretinol (AR), and 5,6-epoxyretinyl palmitate (5,6-epoxy-RP) in human skin Jurkat T cells with and without light irradiation. Irradiation of cells in the absence of a retinoid rendered little damage, but the presence of RP, 5,6-epoxy-RP, or AR (50, 100, 150, and 200 micromol/L) yielded DNA fragmentation, with cell death occurring at retinoid concentrations of 100 micromol/L or greater. The investigators concluded that DNA damage and cytotoxicity are engendered by RP and its photodecomposition products in association with UVA and visible light exposure. They also determined that UVA irradiation of these retinoids produces free radicals that spur DNA strand cleavage (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75).

RP accounts for most of the retinyl esters endogenously formed in skin. In 2006, Yan et al., noting that exogenous RP accumulates via topically applied cosmetic and skin care formulations, investigated the time course for buildup and disappearance of RP and retinol in the stratified layers of skin from female SKH-1 mice singly or repeatedly dosed with topical creams containing 0.5% or 2% RP. The researchers observed that within 24 hours of application, RP quickly diffused into the stratum corneum and epidermal skin layers. RP and retinol levels were lowest in the dermis, intermediate in the stratum corneum, and highest in the epidermis. In separated skin layers and intact skin, RP and retinol levels declined over time, but for 18 days, RP levels remained higher than control values. The investigators concluded that topically applied RP changed the normal physiological levels of RP and retinol in the skin of mice (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2006;22:181-91).

Having previously shown that irradiation of RP with UVA leads to the formation of photodecomposition products, synthesis of reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation induction, Xia et al. demonstrated comparable results, identifying RP as a photosensitizer following irradiation with UVB light (Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90).

Recommendations

In light of the controversy swirling around RP and the appropriate concern it has engendered, in addition to the weight of evidence as well as experience from personal observation, I advise patients to avoid daytime use of products with RP high on the ingredient list. I add that it poses real risks while offering minimal benefits. Such patients should be using retinol or tretinoin. I recommend the use of retinoids at night, to avoid the photosensitizing action induced by UVA or UVB on retinoids left on the skin.

Conclusion

Retinyl palmitate does not penetrate very well into the skin. Consequently, for over-the-counter topical formulations, I recommend retinol instead. Because of the slow penetration of RP into the skin, the RP that remains on the skin will undergo photoreaction more than a substance that is rapidly absorbed. When exposed to light, RP on the skin may undergo metabolism and/or photoreaction to generate reactive oxygen species. These reactive oxygen species or free radicals can theoretically lead to increased skin cancer. That said, sufficient evidence to establish a causal link between RP and skin cancer has not been produced. Nor, I’m afraid, are there any good reasons to recommend the use of RP. More research on this subject is needed and will likely emerge in a timely fashion.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at [email protected]. This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News.

Retinyl palmitate, a storage and ester form of retinol (vitamin A) and the prevailing type of vitamin A found naturally in the skin (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75), has become increasingly popular during the past 2 decades. It is widely used in more than 600 skin care products, including cosmetics and sunscreens, and, with FDA approval, over-the-counter and prescription drugs (Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). It was also the subject of a controversial summer 2010 report by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in which the organization warned of possible photocarcinogenicity associated with retinyl palmitate (RP)-containing sunscreens.

Although vitamin A storage in the epidermis takes the form of retinyl esters and retinols, they act differently when exposed to UV light. The retinols display UVB-resistant and UVB-sensitive characteristics not exhibited by retinyl esters such as RP (Dermatology 1999;199:302-7). The EWG used "vitamin A" and "retinyl palmitate" interchangeably in their criticisms and follow-ups, which is misleading. The vitamin A family of drugs includes retinyl esters, retinol, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene, and oral isotretinoin (Accutane), in addition to four carotenoids, including beta-carotene, many of which have been shown to prevent or protect against cancer (Br. J. Cancer 1988;57:428-33; Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:949-56; J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981;76:178-80; Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1981;270:453-62). That does not mean that RP prevents cancer just because oral retinol, beta-carotene, or tretinoin have been shown to do so, for example. In fact, the study that the EWG refers to shows evidence that RP may lead to skin tumors in mice.

In response to the EWG report, Wang et al. acknowledged that of the eight in vitro studies published by the Food and Drug Administration from 2002 to 2009, four revealed that reactive oxygen species were produced by RP after UVA exposure (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67; Toxicol. Ind. Health 2007;23:625-31; Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163:30-43; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90; Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:129-38). However, they questioned the relevance of these results in the context of the convoluted mechanisms of the antioxidant setting in human skin. They also contended that the National Toxicology Program (NTP) study on which the EWG based its report failed to prove that the combination of RP and UV results in photocarcinogenesis and, in fact, was rife with reasons for skepticism (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). The EWG offered its own counterarguments and stood by its report. Rather than wade further into the debate that occurred in 2010 and found its way into the pages of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2010;63:903-6), let’s review what is known about RP.

What else do we know about RP?

In 1997, Duell et al. showed that unoccluded retinol is more effective at penetrating human skin in vivo than RP or retinoic acid (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;109:301-5).

In 2003, Antille et al. used an in vitro model to evaluate the photoprotective activity of RP, and then applied topical RP on the back of hairless mice before exposing them to UVB. They also applied topical RP or a sunscreen on the buttocks of human volunteers before exposing them to four minimal erythema doses of UVB. The investigators found that RP was as efficient in vitro as the commercial filter octylmethoxycinnamate in preventing UVB-induced fluorescence or photobleaching of fluorescent markers. Topical RP also significantly suppressed the formation of thymine dimers in mouse epidermis and human skin. In the volunteers, topical RP was as efficient as an SPF (sun protection factor) 20 sunscreen in preventing sunburn erythema (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1163-7).

In 2005, Yan et al. studied the phototoxicity of RP, anhydroretinol (AR), and 5,6-epoxyretinyl palmitate (5,6-epoxy-RP) in human skin Jurkat T cells with and without light irradiation. Irradiation of cells in the absence of a retinoid rendered little damage, but the presence of RP, 5,6-epoxy-RP, or AR (50, 100, 150, and 200 micromol/L) yielded DNA fragmentation, with cell death occurring at retinoid concentrations of 100 micromol/L or greater. The investigators concluded that DNA damage and cytotoxicity are engendered by RP and its photodecomposition products in association with UVA and visible light exposure. They also determined that UVA irradiation of these retinoids produces free radicals that spur DNA strand cleavage (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75).

RP accounts for most of the retinyl esters endogenously formed in skin. In 2006, Yan et al., noting that exogenous RP accumulates via topically applied cosmetic and skin care formulations, investigated the time course for buildup and disappearance of RP and retinol in the stratified layers of skin from female SKH-1 mice singly or repeatedly dosed with topical creams containing 0.5% or 2% RP. The researchers observed that within 24 hours of application, RP quickly diffused into the stratum corneum and epidermal skin layers. RP and retinol levels were lowest in the dermis, intermediate in the stratum corneum, and highest in the epidermis. In separated skin layers and intact skin, RP and retinol levels declined over time, but for 18 days, RP levels remained higher than control values. The investigators concluded that topically applied RP changed the normal physiological levels of RP and retinol in the skin of mice (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2006;22:181-91).

Having previously shown that irradiation of RP with UVA leads to the formation of photodecomposition products, synthesis of reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation induction, Xia et al. demonstrated comparable results, identifying RP as a photosensitizer following irradiation with UVB light (Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90).

Recommendations

In light of the controversy swirling around RP and the appropriate concern it has engendered, in addition to the weight of evidence as well as experience from personal observation, I advise patients to avoid daytime use of products with RP high on the ingredient list. I add that it poses real risks while offering minimal benefits. Such patients should be using retinol or tretinoin. I recommend the use of retinoids at night, to avoid the photosensitizing action induced by UVA or UVB on retinoids left on the skin.

Conclusion

Retinyl palmitate does not penetrate very well into the skin. Consequently, for over-the-counter topical formulations, I recommend retinol instead. Because of the slow penetration of RP into the skin, the RP that remains on the skin will undergo photoreaction more than a substance that is rapidly absorbed. When exposed to light, RP on the skin may undergo metabolism and/or photoreaction to generate reactive oxygen species. These reactive oxygen species or free radicals can theoretically lead to increased skin cancer. That said, sufficient evidence to establish a causal link between RP and skin cancer has not been produced. Nor, I’m afraid, are there any good reasons to recommend the use of RP. More research on this subject is needed and will likely emerge in a timely fashion.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at [email protected]. This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News.

Retinyl palmitate, a storage and ester form of retinol (vitamin A) and the prevailing type of vitamin A found naturally in the skin (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75), has become increasingly popular during the past 2 decades. It is widely used in more than 600 skin care products, including cosmetics and sunscreens, and, with FDA approval, over-the-counter and prescription drugs (Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). It was also the subject of a controversial summer 2010 report by the Environmental Working Group (EWG) in which the organization warned of possible photocarcinogenicity associated with retinyl palmitate (RP)-containing sunscreens.

Although vitamin A storage in the epidermis takes the form of retinyl esters and retinols, they act differently when exposed to UV light. The retinols display UVB-resistant and UVB-sensitive characteristics not exhibited by retinyl esters such as RP (Dermatology 1999;199:302-7). The EWG used "vitamin A" and "retinyl palmitate" interchangeably in their criticisms and follow-ups, which is misleading. The vitamin A family of drugs includes retinyl esters, retinol, tretinoin, adapalene, tazarotene, and oral isotretinoin (Accutane), in addition to four carotenoids, including beta-carotene, many of which have been shown to prevent or protect against cancer (Br. J. Cancer 1988;57:428-33; Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:949-56; J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981;76:178-80; Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1981;270:453-62). That does not mean that RP prevents cancer just because oral retinol, beta-carotene, or tretinoin have been shown to do so, for example. In fact, the study that the EWG refers to shows evidence that RP may lead to skin tumors in mice.

In response to the EWG report, Wang et al. acknowledged that of the eight in vitro studies published by the Food and Drug Administration from 2002 to 2009, four revealed that reactive oxygen species were produced by RP after UVA exposure (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67; Toxicol. Ind. Health 2007;23:625-31; Toxicol. Lett. 2006;163:30-43; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90; Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005;18:129-38). However, they questioned the relevance of these results in the context of the convoluted mechanisms of the antioxidant setting in human skin. They also contended that the National Toxicology Program (NTP) study on which the EWG based its report failed to prove that the combination of RP and UV results in photocarcinogenesis and, in fact, was rife with reasons for skepticism (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010;63:903-6; Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2011;27:58-67). The EWG offered its own counterarguments and stood by its report. Rather than wade further into the debate that occurred in 2010 and found its way into the pages of the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology (2010;63:903-6), let’s review what is known about RP.

What else do we know about RP?

In 1997, Duell et al. showed that unoccluded retinol is more effective at penetrating human skin in vivo than RP or retinoic acid (J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997;109:301-5).

In 2003, Antille et al. used an in vitro model to evaluate the photoprotective activity of RP, and then applied topical RP on the back of hairless mice before exposing them to UVB. They also applied topical RP or a sunscreen on the buttocks of human volunteers before exposing them to four minimal erythema doses of UVB. The investigators found that RP was as efficient in vitro as the commercial filter octylmethoxycinnamate in preventing UVB-induced fluorescence or photobleaching of fluorescent markers. Topical RP also significantly suppressed the formation of thymine dimers in mouse epidermis and human skin. In the volunteers, topical RP was as efficient as an SPF (sun protection factor) 20 sunscreen in preventing sunburn erythema (J. Invest. Dermatol. 2003;121:1163-7).

In 2005, Yan et al. studied the phototoxicity of RP, anhydroretinol (AR), and 5,6-epoxyretinyl palmitate (5,6-epoxy-RP) in human skin Jurkat T cells with and without light irradiation. Irradiation of cells in the absence of a retinoid rendered little damage, but the presence of RP, 5,6-epoxy-RP, or AR (50, 100, 150, and 200 micromol/L) yielded DNA fragmentation, with cell death occurring at retinoid concentrations of 100 micromol/L or greater. The investigators concluded that DNA damage and cytotoxicity are engendered by RP and its photodecomposition products in association with UVA and visible light exposure. They also determined that UVA irradiation of these retinoids produces free radicals that spur DNA strand cleavage (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2005;21:167-75).

RP accounts for most of the retinyl esters endogenously formed in skin. In 2006, Yan et al., noting that exogenous RP accumulates via topically applied cosmetic and skin care formulations, investigated the time course for buildup and disappearance of RP and retinol in the stratified layers of skin from female SKH-1 mice singly or repeatedly dosed with topical creams containing 0.5% or 2% RP. The researchers observed that within 24 hours of application, RP quickly diffused into the stratum corneum and epidermal skin layers. RP and retinol levels were lowest in the dermis, intermediate in the stratum corneum, and highest in the epidermis. In separated skin layers and intact skin, RP and retinol levels declined over time, but for 18 days, RP levels remained higher than control values. The investigators concluded that topically applied RP changed the normal physiological levels of RP and retinol in the skin of mice (Toxicol. Ind. Health 2006;22:181-91).

Having previously shown that irradiation of RP with UVA leads to the formation of photodecomposition products, synthesis of reactive oxygen species, and lipid peroxidation induction, Xia et al. demonstrated comparable results, identifying RP as a photosensitizer following irradiation with UVB light (Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2006;3:185-90).

Recommendations

In light of the controversy swirling around RP and the appropriate concern it has engendered, in addition to the weight of evidence as well as experience from personal observation, I advise patients to avoid daytime use of products with RP high on the ingredient list. I add that it poses real risks while offering minimal benefits. Such patients should be using retinol or tretinoin. I recommend the use of retinoids at night, to avoid the photosensitizing action induced by UVA or UVB on retinoids left on the skin.

Conclusion

Retinyl palmitate does not penetrate very well into the skin. Consequently, for over-the-counter topical formulations, I recommend retinol instead. Because of the slow penetration of RP into the skin, the RP that remains on the skin will undergo photoreaction more than a substance that is rapidly absorbed. When exposed to light, RP on the skin may undergo metabolism and/or photoreaction to generate reactive oxygen species. These reactive oxygen species or free radicals can theoretically lead to increased skin cancer. That said, sufficient evidence to establish a causal link between RP and skin cancer has not been produced. Nor, I’m afraid, are there any good reasons to recommend the use of RP. More research on this subject is needed and will likely emerge in a timely fashion.

Dr. Baumann is in private practice in Miami Beach. She did not disclose any conflicts of interest. To respond to this column, or to suggest topics for future columns, write to her at [email protected]. This column, "Cosmeceutical Critique," appears regularly in Skin & Allergy News.

Do online doctor ratings matter?

Doctor ratings websites can be biased, clinically insignificant, and statistically unreliable. They’re also growing rapidly. In 2011, Inc. Magazine listed vitals.com, a popular doctor rating site, as No. 47 out of the top 100 fasting growing private companies; it grew an impressive 4,637% between 2008 and 2011.

Similarly, a study by Guodong Gordon Gao and colleagues, published in The Journal of Medical Internet Research in February 2012, found a 100-fold increase in the number of ratings on ratemds.com over the last 5 years (J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14:e38 [doi:10.2196/jmir.2003]). Healthgrades.com, another well known doctor rating site, has 15 million visitors every month, and continues to grow.

As physicians, we have a responsibility to educate ourselves about such rating sites and to use them to our advantage. Start by thinking of them more as directories than rating sites and using them to promote you and your practice.

Most physicians, policy leaders, and consumers believe that transparency will ultimately improve the quality of health care. However, in their current state, doctor rating sites suffer from significant drawbacks, including a limited number of reviews, which skews results either positive or negative, a dearth of reviews about physician quality, and inaccurate information about physicians and practices.

According to a May 2011 report by the Pew Research Center (pewinternet.org) only 4% of Internet users have posted a review online of a doctor. In fact, many physicians have only one patient review.