User login

Cut to the Quick

A 41‐year‐old woman with dwarfism was referred for evaluation of an isolated elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 792 U/L (normal value, 3195 U/L) and a gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT) of 729 U/L (normal value, 737 U/L), found incidentally on routine laboratory screening. She denied any fevers, chills, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

The presence of an isolated ALP elevation, presumably of hepatobiliary origin given the increase in GGT, in a relatively young woman immediately calls to mind the diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis, and I would specifically inquire about pruritus, which occurs commonly in this setting. The absence of abdominal pain argues against the diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Other processes that could result in this asymptomatic presentation include infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and other causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The absence of systemic symptoms makes disseminated infection or malignancy with hepatic involvement less likely. I would query whether underlying dwarfism can be associated with metabolic abnormalities that cause infiltrative liver disease, functional or anatomical hepatobiliary abnormalities, or malignancy.

The patient's medical history was notable for chronic constipation, allergic rhinitis, and basal‐cell carcinoma. She had reconstructive surgeries of the left hip and knee 28 years ago without complications. She underwent a right total hip replacement for hip dysplasia 6 months prior, which was complicated by a postoperative joint infection with Enterobacter cloacae. The hardware was retained, and she was treated with incision and drainage and a prolonged fluoroquinolone course. Furthermore, she had a history of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), which manifested at the age of 20 years. A bone‐marrow biopsy at that time showed no evidence of hematologic malignancy. For her ITP, she had initially received intravenous immunoglobulin (Ig) and cyclosporine without sustained benefit. She underwent a splenectomy at the age of 26 years and was treated intermittently with rituximab over 11 years prior to admission. Her medications included cetirizine. Her parents were nonconsanguineous, of European and Southeast Asian ancestry, and healthy. She was in a long‐term monogamous relationship. The patient had been employed as an educator.

The history of immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia raises the possibility that the present illness may be part of a broader autoimmune diathesis. Other causes of secondary ITP, such as drug‐induced reactions, hematologic malignancies, and viral infections, are unlikely, as her ITP has been persistent for more than 20 years. She has not evolved into a common phenotypic pattern of autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus after the appearance of ITP, nor does she endorse a history of thromboembolic complications that would suggest antiphospholipid syndrome.

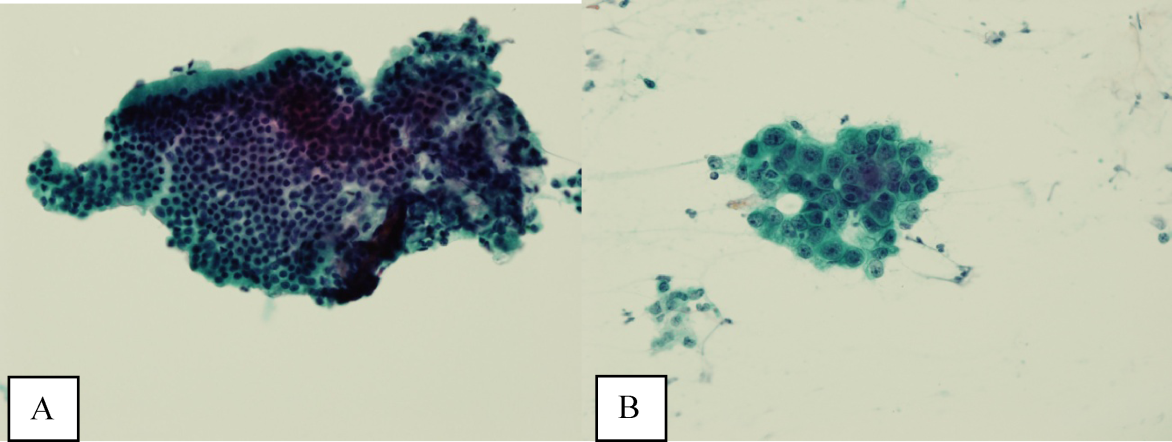

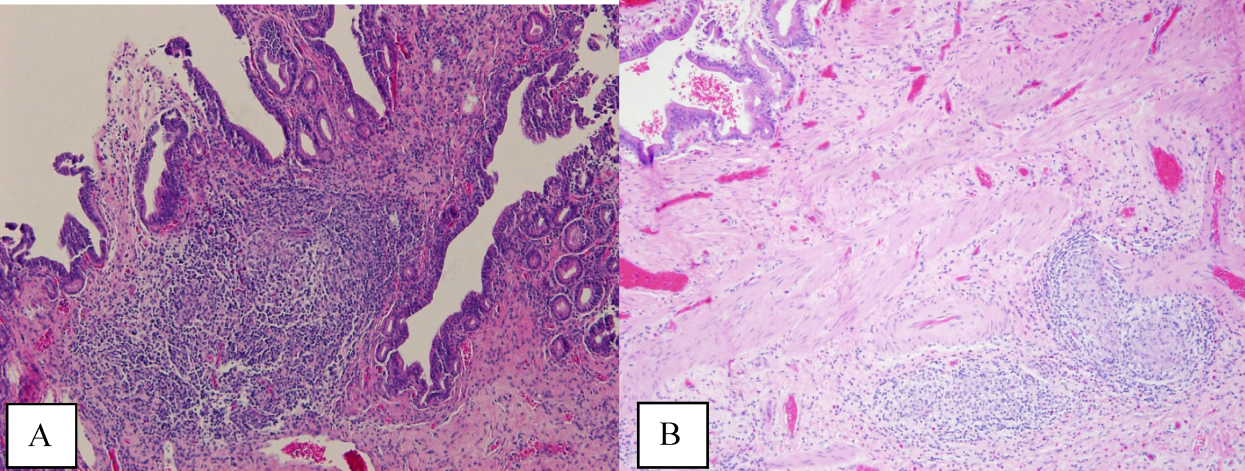

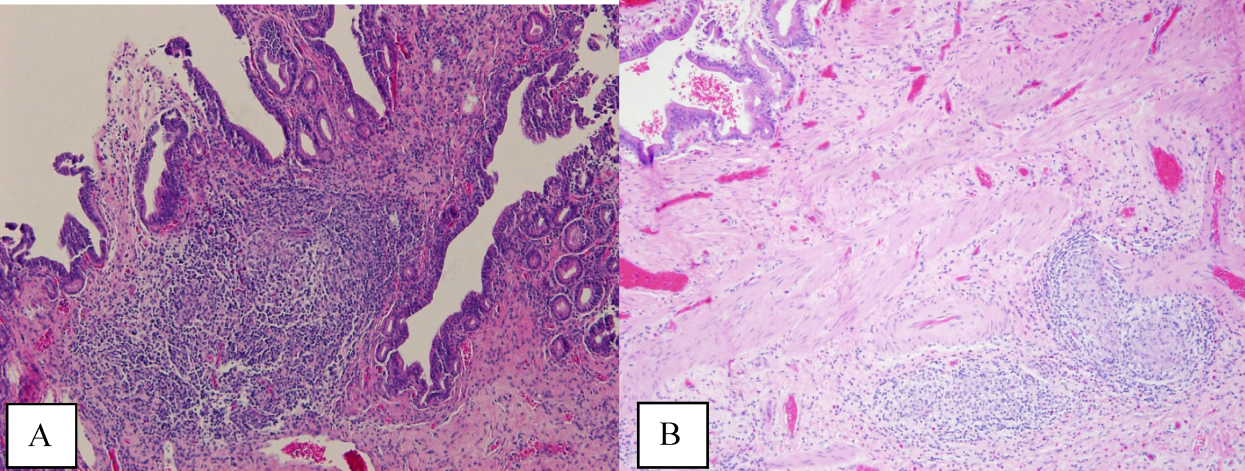

Ultrasound of the abdomen demonstrated narrowing of the extrahepatic biliary duct in the region of the pancreas without evidence of a mass lesion. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis similarly showed mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with narrowing of the extrahepatic duct in the region of the pancreas without apparent pancreatic mass. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) confirmed a stricture in the distal common bile duct and dilatation of the common bile duct. Cytology brushings obtained during ERCP showed groups of overlapping, enlarged cells with pleomorphic irregular nuclei, one or more prominent nucleoli, and focal nuclear molding, leading to a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Figure 1).

The absence of jaundice and pruritus indicates incomplete biliary obstruction. Commonbile duct strictures are most commonly seen after manipulation of the biliary tree. Neoplasms including pancreatic cancer, adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, and cholangiocarcinoma may cause compression and obstruction of the common bile duct, as well as stricture formation mediated by a desmoplastic reaction to the tumor. Occasionally, metastatic malignancy or lymphoma may involve the porta hepatis and cause extrinsic compression of the common bile duct. Other etiologies of strictures include sclerosing cholangitis and opportunistic infections such as Cryptosporidium, cytomegalovirus, and microsporidiosis, which are not supported by this patient's history.

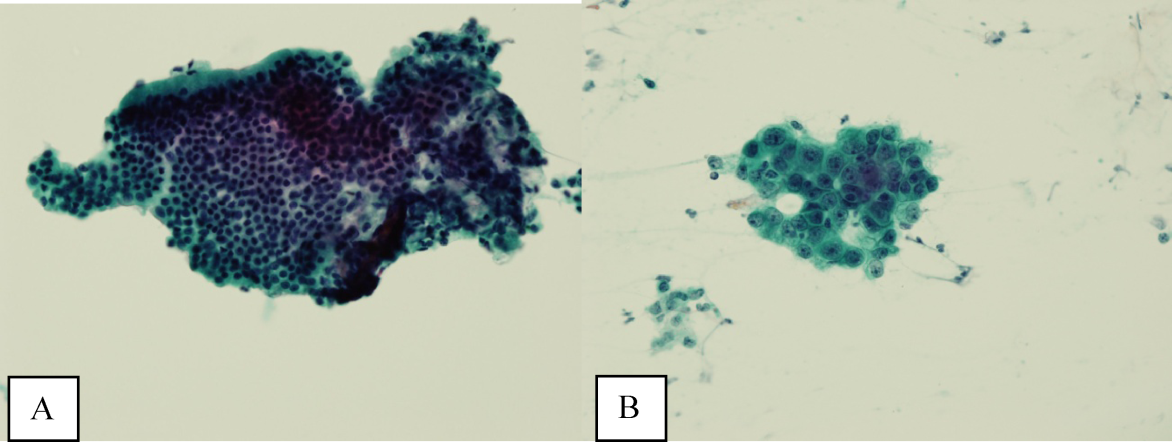

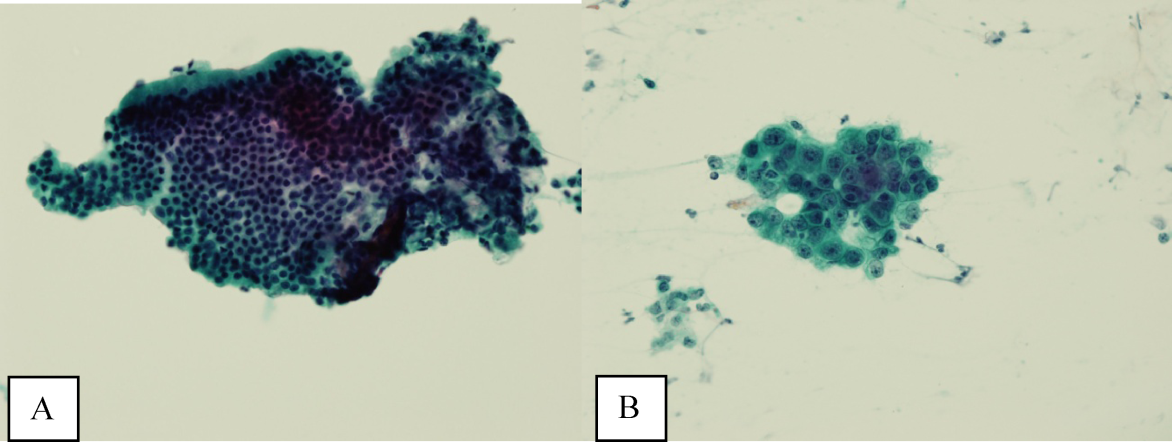

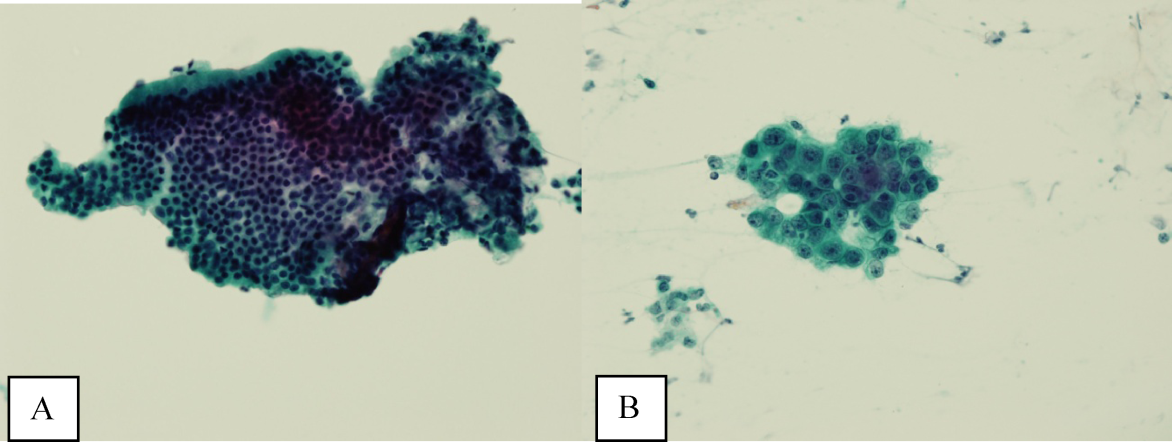

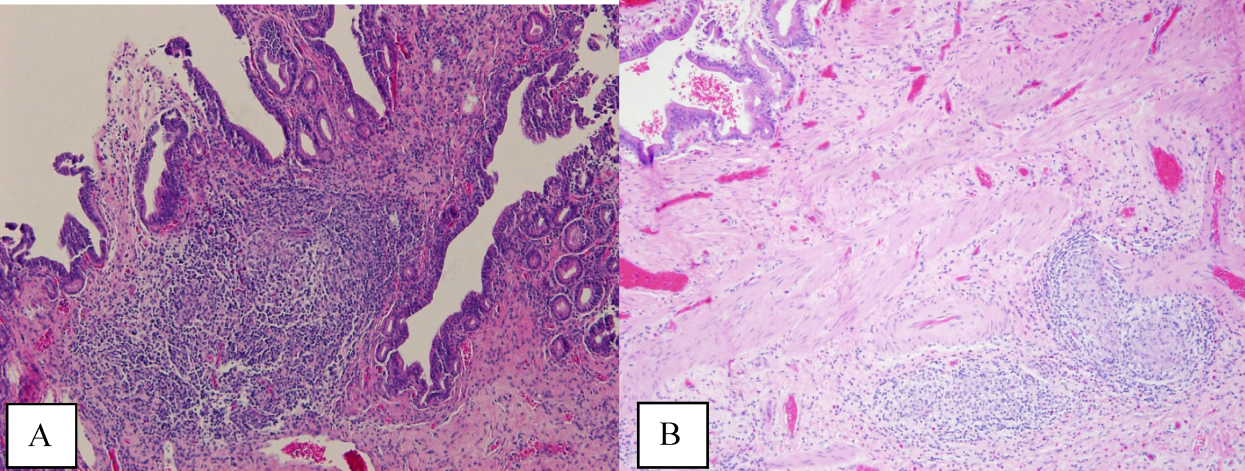

The atypical cells seen on ERCP brushings were interpreted as evidence of cholangiocarcinoma. The patient underwent a pylorus‐sparing Whipple procedure. Examination of the surgical pathology specimens revealed diffuse non‐necrotizing granulomatous inflammation involving the bile duct and gallbladder (Figure 2). There was focal atypia of the bile‐duct epithelial cells, but no evidence of malignancy. There were non‐necrotizing granulomas in numerous lymph nodes, some with significant sclerosis; stains and cultures for acid‐fast bacilli and fungi were negative, and stains for IgG4 and CD1a for Langerhans‐cell histiocytosis were negative.

Granulomatous inflammation may be caused by a variety of intracellular infections, environmental and occupational exposures, and drug hypersensitivity, or may be associated with malignancy such as lymphoma. In the absence of an alternative explanation, the presence of non‐necrotizing granulomas in multiple organs suggests the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, even if classic intrathoracic involvement is not present. Hepatic involvement with sarcoidosis is common but rarely symptomatic, whereas biliary disease is distinctly uncommon. Interestingly, there is an association between both primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosing cholangitis with sarcoidosis. The pathologic findings could indicate an autoimmune process that has led to widespread granulomas with this unusual distribution. Disseminated infections such as mycobacterial or fungal diseases seem much less plausible in this woman, who had no prior systemic complaints. The atypical cells seen on the ERCP brushings were almost certainly caused by inflammation and a fibroproliferative response rather than malignancy.

On further questioning, the patient endorsed a history of multiple childhood ear infections that required bilateral myringotomy tubes, and multiple episodes of sinusitis, but both problems improved in adulthood. She had experienced 2 episodes of dermatomal zoster in her lifetime. She also noted frequent vaginal yeast infections. She denied any history of pneumonias or thrush. In her second decade of life, she developed allergic rhinitis and eczema. She denied any chemical or environmental exposures. She had had negative tuberculin skin tests as part of her occupational screening and denied any recent travel.

The additional history of recurrent upper‐respiratory infections early in life and subsequent episodes of dermatomal zoster and candidal infections increases the likelihood that this patient has a primary immunodeficiency. A combined cellular and humoral immunodeficiency would predispose to both bacterial sinopulmonary infections, generally a result of Ig isotype or IgG subclass deficiencies, and recurrent zoster and candidal infection. Any evaluation of her Igs at this time may be confounded by her receipt of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy, which may decrease serum Ig levels.

The relatively benign course in terms of infection is consistent with the heterogeneous immunodeficiencies classified as combined immunodeficiency (CID), a less‐penetrant phenotype of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), or common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Autoimmunity is a frequent manifestation of CID and CVID, and affected patients have an increased risk of lymphoma and other malignancies. Granulomatous disease may also be a manifestation of both CID and CVID.

Postoperatively, she developed progressive abdominal distension and pain. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed colonic dilatation consistent with Ogilvie pseudo‐obstruction. On postoperative day 9, she developed fevers. On physical examination, her temperature was 38.5C, the blood pressure was 104/56 mm Hg, and the heart rate was 131 beats per minute. Her oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. Her height was 105 cm. She had diffuse alopecia without scarring. She did not have a malar rash or oral ulcerations. Both lungs were clear to auscultation. A cardiac examination showed tachycardia with a regular rhythm, normal heart sounds, and no murmurs. Her musculoskeletal exam was notable for short limbs and phalanges, without synovitis. Bilateral hip exam demonstrated internal and external range of motion without abnormalities. No rashes were present. Her abdominal exam revealed diffuse tenderness with postoperative drains in place. She had nonbloody loose stools.

Although autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis can rarely manifest with fevers, evaluation of postoperative fever in this patient should focus first on common processes that also occur in immunocompetent patients. Since she has had a splenectomy and we are now suspicious of an underlying immunodeficiency, appropriate cultures should be obtained and broad‐spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be initiated without delay. The presence of nonscarring alopecia could either represent autoimmune alopecia, if the onset was recent, or it could be part of this patient's underlying skeletal dysplasia syndrome.

Piperacillin/tazobactam and oral metronidazole were started for presumed intra‐abdominal infection. The white cell count was 20,500/mm3 with 96% neutrophils, 1.4% lymphocytes with an absolute lymphocyte count 0.33 109/L (normal value, >1.0 109/L), and 2.6% monocytes. The hematocrit was 27.8% with a mean corpuscular volume of 95 fL. The platelet count was 323,000/mm3. Serum aminotransferase and total bilirubin levels were normal, and ALP was 904 U/L. The serum albumin was 1.2 g/dL (normal value, 3.54.8 g/dL) and prealbumin was 6 mg/dL (normal value, 2037 mg/dL).

Blood cultures returned positive for E. cloacae. Clostridium difficile toxin assay was negative. Piperacillin/tazobactam was switched to meroperem, and metronidazole was discontinued. She continued to have fevers, and on postoperative day 16, repeat blood cultures and urine cultures grew Candida albicans; caspofungin was initiated.

In addition to the neutrophilic leukocytosis in response to gram‐negative bacteremia, there is marked lymphopenia. Although sepsis may cause transient declines in the total lymphocyte count, I do not believe that this entirely accounts for such severe lymphopenia. The albumin is also profoundly low. Her catabolic postsurgical state might explain part of this abnormality, but taken together with her prior gastrointestinal symptoms, these findings could be consistent with intestinal malabsorption or a protein‐losing enteropathy, which can also be associated with primary immunodeficiency.

Serum angiotensin‐converting enzyme was 32 U/L (normal value, 967 U/L). A CT of the chest was performed and did not reveal mediastinal lymphadenopathy, nodules, or consolidations. Antinuclear, antismooth muscle, and antimitochondrial antibodies were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus antibody was negative. Serum quantitative Igs, including IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE, were undetectable.

Serum lymphocyte subset analysis revealed a CD3 T‐cell count of 101 106/L (normal value, >690 106/L), CD4 T cells 46 106/L (normal value, >410 106/L), CD8 T cells 55 106/L (normal value, >190 106/L), CD19 B cells undetectable at 2 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L), CD16 CD56 NK cells 134 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L). T‐cell lymphocyte proliferation assay showed a completely absent response to candida and tetanus antigens, and a very low response to mitogens.

The immunologic evaluation is confounded by her critical illness and by the prior administration of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody. Despite these caveats, the results of these studies are profoundly abnormal and suggest a combined B‐cell and T‐cell immunodeficiency that is more severe from a laboratory standpoint than her history prior to surgery has suggested. Low T lymphocyte numbers, with or without functional abnormalities, are a hallmark of CID and can be also be seen in CVID. The extremely low Ig levels in the presence of severe infections warrant replacement with intravenous Ig.

Combined immunodeficiency and CVID may be associated with a number of mutations; elucidating the genetics and molecular mechanism of immunodeficiency may be important in identifying patients whose immunodeficiency may be cured by stem‐cell transplantation.

Intravenous Ig was administered. Her serum was sent for sequencing of the RMRP gene, mutations of which are found in patients who have cartilage‐hair hypoplasia (CHH), a rare autosomal recessive skeletal dysplasia characterized by short‐limbed dwarfism; fine, sparse hair; and variable degrees of immunodeficiency. She was found to have 2 RMRP mutations, a 126 CT transition and a 218 AC transversion.

The patient developed multiple abdominal abscesses, which were drained and grew vancomycin‐resistant enterococcus (VRE) and C. albicans. Blood cultures also turned positive for VRE. A colonoscopy was performed because of radiographic evidence suggestive of colitis. Biopsies taken from the colonoscopy were negative for cytomegalovirus or other infections, but did reveal rare non‐necrotizing granulomas. The patient developed progressive multiorgan failure requiring mechanical ventilation and continuous venovenous hemofiltration. On postoperative day 36, the patient was transitioned to comfort care, and she expired the next day. A unifying diagnosis of CHH‐related immunodeficiency and disseminated granulomatous disease, complicated by postoperative sepsis, was made. An autopsy was declined.

COMMENTARY

Evaluation of abnormal liver tests is a frequent diagnostic challenge faced by clinicians in both ambulatory and inpatient settings. Identifying the pattern of liver injuryhepatocellular, cholestatic, or infiltrativemay guide the initial workup. This patient's presentation of a normal bilirubin and transaminases with elevations in ALP was consistent with infiltrative hepatic disease. The radiographic finding of extrahepatic biliary strictures, on the other hand, raised concern for an obstructive etiology and prompted an ERCP. Brush cytology has high specificity for malignancy, but interpretation of atypical cells can rarely be inconclusive or be associated with false positives.[1]

The suspicion for infiltrative hepatitis was supported postoperatively by the discovery of diffuse hepatobiliary granulomatous disease, which can be associated with a spectrum of disease states including sarcoidosis, autoimmune disorders, intracellular infections, immunodeficiency, malignancy, environmental or occupational exposures, and drug reactions.[2, 3] During the patient's hospital course and case presentation to the discussant, the possibility of sarcoidosis was raised based on the operative findings. Additional history‐taking was essential to evaluate other etiologies of granulomatous inflammation, and this clinical correlation prevented a second erroneous pathologic diagnosis.

Multiple elements of this patient's presentation led to recognition of an underlying primary immunodeficiency. Her prior history of recurrent childhood infections, dermatomal zoster, and vaginal infections suggested a congenital immunodeficiency. The additional features of refractory autoimmune cytopenias (ie, ITP), granulomatous inflammation, undetectable serum Igs, and low T‐cell and B‐cell counts, were consistent with CID or CVID. By definition, CID involves defects in both B and T cells; CVID represents a predominantly B‐cell disorder characterized by abnormalities in Ig production, though concomitant T‐cell dysfunction may also be found.[4] It is worth noting that although this patient had previously received anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, which depletes CD20‐positive B lymphocytes, Ig levels are not typically depleted by anti‐CD20 unless there is preexisting antibody deficiency.[5]

We were able to make the unifying diagnosis of CHH to explain her constellation of physical findings, laboratory abnormalities, and histopathology. Also known as McKusick type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, CHH has a relatively high carrier frequency in the Amish (1:19) and Finnish (1:76) populations.[6, 7] Additional clinical features can include gastrointestinal disorders, poorly pigmented skin and hair, and joint disorders. Dysregulation of immunity is a particular challenge and can be manifested by malignancy, lymphoproliferative disease, cytopenias, or primary immunodeficiencies. Combined immunodeficiency and T cellmediated defects are most common, although there are case reports of CHH associated with severe humoral defects.[8, 9] Primary immunodeficiency, if severe and recognized early, can be treated with bone‐marrow transplantation.[10, 11] Granulomatous inflammation also has been described in CHH.[12]

Although tissue biopsy is often viewed as the gold standard for establishing a definitive diagnosis, this case highlights the significance of applying clinical context to pathologic interpretation and medical decision‐making. Prior to any diagnostic procedure, the patient's history of dwarfism, recurrent infections, and refractory ITP provided clues to an immunodeficiency syndrome, CHH. Knowledge of this immunodeficiency might have better informed the initial pathologic interpretation of atypical cells, which were misread as adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, awareness of the patient's profound immunodeficiency would have given pause to proceeding with invasive surgery without prior Ig and antibiotic support and may have averted a fatal outcome.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Infiltrative hepatobiliary diseases may manifest with isolated elevations in ALP.

- Granulomas and autoimmune cytopenias may be features of primary immunodeficiency states.

- A history of recurrent childhood infections should raise suspicion for congenital immunodeficiencies.

- Unique medical complications, including immunodeficiency, can be associated with dwarfism subtypes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer M. Puck, MD, from the University of California San Francisco, Departments of Immunology and Pediatrics, for her invaluable contribution to the discussion on immunodeficiencies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , . Brush cytology of ductal strictures during ERCP. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2000;63:254–259.

- , . Granulomatous lung disease: an approach to the differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134;667–690.

- James DG, Zumla A, eds. The Granulomatous Disorders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999:17–27.

- , , , et al. Unraveling the complexity of T cell abnormalities in common variable immunodeficiency. J Immunol. 2007;178:3932–3943.

- , , , et al. Does rituximab aggravate pre‐existing hypogammaglobulinaemia? J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:275–277.

- . Cartilage‐hair hypoplasia in Finland: epidemiological and genetic aspects of 107 patients. J Med Genet. 1992;29:652–655.

- , , , et al. High‐resolution genetic mapping of the cartilage‐hair hypoplasia (CHH) gene in Amish and Finnish families. Genomics. 1994;20:347–353.

- , , , et al. Combined immunodeficiency and vaccine‐related poliomyelitis in a child with cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. J Pediatr. 1975;86:868–872.

- , , . Deficiency of humoral immunity in cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. J Pediatr. 2000;137:487–492.

- , , , , . Bone marrow transplantation for cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:751–756.

- , , , et al. Clinical and immunologic outcome of patients with cartilage hair hypoplasia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [published corrections appear in Blood. 2010;116:2402 and Blood. 2011;117:2077]. Blood. 2010;116:27–35.

- , , , et al. Granulomatous inflammation in cartilage‐hair hypoplasia: risks and benefits of anti‐TNF‐α mAbs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:847–853.

A 41‐year‐old woman with dwarfism was referred for evaluation of an isolated elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 792 U/L (normal value, 3195 U/L) and a gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT) of 729 U/L (normal value, 737 U/L), found incidentally on routine laboratory screening. She denied any fevers, chills, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

The presence of an isolated ALP elevation, presumably of hepatobiliary origin given the increase in GGT, in a relatively young woman immediately calls to mind the diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis, and I would specifically inquire about pruritus, which occurs commonly in this setting. The absence of abdominal pain argues against the diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Other processes that could result in this asymptomatic presentation include infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and other causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The absence of systemic symptoms makes disseminated infection or malignancy with hepatic involvement less likely. I would query whether underlying dwarfism can be associated with metabolic abnormalities that cause infiltrative liver disease, functional or anatomical hepatobiliary abnormalities, or malignancy.

The patient's medical history was notable for chronic constipation, allergic rhinitis, and basal‐cell carcinoma. She had reconstructive surgeries of the left hip and knee 28 years ago without complications. She underwent a right total hip replacement for hip dysplasia 6 months prior, which was complicated by a postoperative joint infection with Enterobacter cloacae. The hardware was retained, and she was treated with incision and drainage and a prolonged fluoroquinolone course. Furthermore, she had a history of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), which manifested at the age of 20 years. A bone‐marrow biopsy at that time showed no evidence of hematologic malignancy. For her ITP, she had initially received intravenous immunoglobulin (Ig) and cyclosporine without sustained benefit. She underwent a splenectomy at the age of 26 years and was treated intermittently with rituximab over 11 years prior to admission. Her medications included cetirizine. Her parents were nonconsanguineous, of European and Southeast Asian ancestry, and healthy. She was in a long‐term monogamous relationship. The patient had been employed as an educator.

The history of immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia raises the possibility that the present illness may be part of a broader autoimmune diathesis. Other causes of secondary ITP, such as drug‐induced reactions, hematologic malignancies, and viral infections, are unlikely, as her ITP has been persistent for more than 20 years. She has not evolved into a common phenotypic pattern of autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus after the appearance of ITP, nor does she endorse a history of thromboembolic complications that would suggest antiphospholipid syndrome.

Ultrasound of the abdomen demonstrated narrowing of the extrahepatic biliary duct in the region of the pancreas without evidence of a mass lesion. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis similarly showed mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with narrowing of the extrahepatic duct in the region of the pancreas without apparent pancreatic mass. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) confirmed a stricture in the distal common bile duct and dilatation of the common bile duct. Cytology brushings obtained during ERCP showed groups of overlapping, enlarged cells with pleomorphic irregular nuclei, one or more prominent nucleoli, and focal nuclear molding, leading to a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Figure 1).

The absence of jaundice and pruritus indicates incomplete biliary obstruction. Commonbile duct strictures are most commonly seen after manipulation of the biliary tree. Neoplasms including pancreatic cancer, adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, and cholangiocarcinoma may cause compression and obstruction of the common bile duct, as well as stricture formation mediated by a desmoplastic reaction to the tumor. Occasionally, metastatic malignancy or lymphoma may involve the porta hepatis and cause extrinsic compression of the common bile duct. Other etiologies of strictures include sclerosing cholangitis and opportunistic infections such as Cryptosporidium, cytomegalovirus, and microsporidiosis, which are not supported by this patient's history.

The atypical cells seen on ERCP brushings were interpreted as evidence of cholangiocarcinoma. The patient underwent a pylorus‐sparing Whipple procedure. Examination of the surgical pathology specimens revealed diffuse non‐necrotizing granulomatous inflammation involving the bile duct and gallbladder (Figure 2). There was focal atypia of the bile‐duct epithelial cells, but no evidence of malignancy. There were non‐necrotizing granulomas in numerous lymph nodes, some with significant sclerosis; stains and cultures for acid‐fast bacilli and fungi were negative, and stains for IgG4 and CD1a for Langerhans‐cell histiocytosis were negative.

Granulomatous inflammation may be caused by a variety of intracellular infections, environmental and occupational exposures, and drug hypersensitivity, or may be associated with malignancy such as lymphoma. In the absence of an alternative explanation, the presence of non‐necrotizing granulomas in multiple organs suggests the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, even if classic intrathoracic involvement is not present. Hepatic involvement with sarcoidosis is common but rarely symptomatic, whereas biliary disease is distinctly uncommon. Interestingly, there is an association between both primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosing cholangitis with sarcoidosis. The pathologic findings could indicate an autoimmune process that has led to widespread granulomas with this unusual distribution. Disseminated infections such as mycobacterial or fungal diseases seem much less plausible in this woman, who had no prior systemic complaints. The atypical cells seen on the ERCP brushings were almost certainly caused by inflammation and a fibroproliferative response rather than malignancy.

On further questioning, the patient endorsed a history of multiple childhood ear infections that required bilateral myringotomy tubes, and multiple episodes of sinusitis, but both problems improved in adulthood. She had experienced 2 episodes of dermatomal zoster in her lifetime. She also noted frequent vaginal yeast infections. She denied any history of pneumonias or thrush. In her second decade of life, she developed allergic rhinitis and eczema. She denied any chemical or environmental exposures. She had had negative tuberculin skin tests as part of her occupational screening and denied any recent travel.

The additional history of recurrent upper‐respiratory infections early in life and subsequent episodes of dermatomal zoster and candidal infections increases the likelihood that this patient has a primary immunodeficiency. A combined cellular and humoral immunodeficiency would predispose to both bacterial sinopulmonary infections, generally a result of Ig isotype or IgG subclass deficiencies, and recurrent zoster and candidal infection. Any evaluation of her Igs at this time may be confounded by her receipt of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy, which may decrease serum Ig levels.

The relatively benign course in terms of infection is consistent with the heterogeneous immunodeficiencies classified as combined immunodeficiency (CID), a less‐penetrant phenotype of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), or common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Autoimmunity is a frequent manifestation of CID and CVID, and affected patients have an increased risk of lymphoma and other malignancies. Granulomatous disease may also be a manifestation of both CID and CVID.

Postoperatively, she developed progressive abdominal distension and pain. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed colonic dilatation consistent with Ogilvie pseudo‐obstruction. On postoperative day 9, she developed fevers. On physical examination, her temperature was 38.5C, the blood pressure was 104/56 mm Hg, and the heart rate was 131 beats per minute. Her oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. Her height was 105 cm. She had diffuse alopecia without scarring. She did not have a malar rash or oral ulcerations. Both lungs were clear to auscultation. A cardiac examination showed tachycardia with a regular rhythm, normal heart sounds, and no murmurs. Her musculoskeletal exam was notable for short limbs and phalanges, without synovitis. Bilateral hip exam demonstrated internal and external range of motion without abnormalities. No rashes were present. Her abdominal exam revealed diffuse tenderness with postoperative drains in place. She had nonbloody loose stools.

Although autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis can rarely manifest with fevers, evaluation of postoperative fever in this patient should focus first on common processes that also occur in immunocompetent patients. Since she has had a splenectomy and we are now suspicious of an underlying immunodeficiency, appropriate cultures should be obtained and broad‐spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be initiated without delay. The presence of nonscarring alopecia could either represent autoimmune alopecia, if the onset was recent, or it could be part of this patient's underlying skeletal dysplasia syndrome.

Piperacillin/tazobactam and oral metronidazole were started for presumed intra‐abdominal infection. The white cell count was 20,500/mm3 with 96% neutrophils, 1.4% lymphocytes with an absolute lymphocyte count 0.33 109/L (normal value, >1.0 109/L), and 2.6% monocytes. The hematocrit was 27.8% with a mean corpuscular volume of 95 fL. The platelet count was 323,000/mm3. Serum aminotransferase and total bilirubin levels were normal, and ALP was 904 U/L. The serum albumin was 1.2 g/dL (normal value, 3.54.8 g/dL) and prealbumin was 6 mg/dL (normal value, 2037 mg/dL).

Blood cultures returned positive for E. cloacae. Clostridium difficile toxin assay was negative. Piperacillin/tazobactam was switched to meroperem, and metronidazole was discontinued. She continued to have fevers, and on postoperative day 16, repeat blood cultures and urine cultures grew Candida albicans; caspofungin was initiated.

In addition to the neutrophilic leukocytosis in response to gram‐negative bacteremia, there is marked lymphopenia. Although sepsis may cause transient declines in the total lymphocyte count, I do not believe that this entirely accounts for such severe lymphopenia. The albumin is also profoundly low. Her catabolic postsurgical state might explain part of this abnormality, but taken together with her prior gastrointestinal symptoms, these findings could be consistent with intestinal malabsorption or a protein‐losing enteropathy, which can also be associated with primary immunodeficiency.

Serum angiotensin‐converting enzyme was 32 U/L (normal value, 967 U/L). A CT of the chest was performed and did not reveal mediastinal lymphadenopathy, nodules, or consolidations. Antinuclear, antismooth muscle, and antimitochondrial antibodies were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus antibody was negative. Serum quantitative Igs, including IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE, were undetectable.

Serum lymphocyte subset analysis revealed a CD3 T‐cell count of 101 106/L (normal value, >690 106/L), CD4 T cells 46 106/L (normal value, >410 106/L), CD8 T cells 55 106/L (normal value, >190 106/L), CD19 B cells undetectable at 2 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L), CD16 CD56 NK cells 134 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L). T‐cell lymphocyte proliferation assay showed a completely absent response to candida and tetanus antigens, and a very low response to mitogens.

The immunologic evaluation is confounded by her critical illness and by the prior administration of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody. Despite these caveats, the results of these studies are profoundly abnormal and suggest a combined B‐cell and T‐cell immunodeficiency that is more severe from a laboratory standpoint than her history prior to surgery has suggested. Low T lymphocyte numbers, with or without functional abnormalities, are a hallmark of CID and can be also be seen in CVID. The extremely low Ig levels in the presence of severe infections warrant replacement with intravenous Ig.

Combined immunodeficiency and CVID may be associated with a number of mutations; elucidating the genetics and molecular mechanism of immunodeficiency may be important in identifying patients whose immunodeficiency may be cured by stem‐cell transplantation.

Intravenous Ig was administered. Her serum was sent for sequencing of the RMRP gene, mutations of which are found in patients who have cartilage‐hair hypoplasia (CHH), a rare autosomal recessive skeletal dysplasia characterized by short‐limbed dwarfism; fine, sparse hair; and variable degrees of immunodeficiency. She was found to have 2 RMRP mutations, a 126 CT transition and a 218 AC transversion.

The patient developed multiple abdominal abscesses, which were drained and grew vancomycin‐resistant enterococcus (VRE) and C. albicans. Blood cultures also turned positive for VRE. A colonoscopy was performed because of radiographic evidence suggestive of colitis. Biopsies taken from the colonoscopy were negative for cytomegalovirus or other infections, but did reveal rare non‐necrotizing granulomas. The patient developed progressive multiorgan failure requiring mechanical ventilation and continuous venovenous hemofiltration. On postoperative day 36, the patient was transitioned to comfort care, and she expired the next day. A unifying diagnosis of CHH‐related immunodeficiency and disseminated granulomatous disease, complicated by postoperative sepsis, was made. An autopsy was declined.

COMMENTARY

Evaluation of abnormal liver tests is a frequent diagnostic challenge faced by clinicians in both ambulatory and inpatient settings. Identifying the pattern of liver injuryhepatocellular, cholestatic, or infiltrativemay guide the initial workup. This patient's presentation of a normal bilirubin and transaminases with elevations in ALP was consistent with infiltrative hepatic disease. The radiographic finding of extrahepatic biliary strictures, on the other hand, raised concern for an obstructive etiology and prompted an ERCP. Brush cytology has high specificity for malignancy, but interpretation of atypical cells can rarely be inconclusive or be associated with false positives.[1]

The suspicion for infiltrative hepatitis was supported postoperatively by the discovery of diffuse hepatobiliary granulomatous disease, which can be associated with a spectrum of disease states including sarcoidosis, autoimmune disorders, intracellular infections, immunodeficiency, malignancy, environmental or occupational exposures, and drug reactions.[2, 3] During the patient's hospital course and case presentation to the discussant, the possibility of sarcoidosis was raised based on the operative findings. Additional history‐taking was essential to evaluate other etiologies of granulomatous inflammation, and this clinical correlation prevented a second erroneous pathologic diagnosis.

Multiple elements of this patient's presentation led to recognition of an underlying primary immunodeficiency. Her prior history of recurrent childhood infections, dermatomal zoster, and vaginal infections suggested a congenital immunodeficiency. The additional features of refractory autoimmune cytopenias (ie, ITP), granulomatous inflammation, undetectable serum Igs, and low T‐cell and B‐cell counts, were consistent with CID or CVID. By definition, CID involves defects in both B and T cells; CVID represents a predominantly B‐cell disorder characterized by abnormalities in Ig production, though concomitant T‐cell dysfunction may also be found.[4] It is worth noting that although this patient had previously received anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, which depletes CD20‐positive B lymphocytes, Ig levels are not typically depleted by anti‐CD20 unless there is preexisting antibody deficiency.[5]

We were able to make the unifying diagnosis of CHH to explain her constellation of physical findings, laboratory abnormalities, and histopathology. Also known as McKusick type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, CHH has a relatively high carrier frequency in the Amish (1:19) and Finnish (1:76) populations.[6, 7] Additional clinical features can include gastrointestinal disorders, poorly pigmented skin and hair, and joint disorders. Dysregulation of immunity is a particular challenge and can be manifested by malignancy, lymphoproliferative disease, cytopenias, or primary immunodeficiencies. Combined immunodeficiency and T cellmediated defects are most common, although there are case reports of CHH associated with severe humoral defects.[8, 9] Primary immunodeficiency, if severe and recognized early, can be treated with bone‐marrow transplantation.[10, 11] Granulomatous inflammation also has been described in CHH.[12]

Although tissue biopsy is often viewed as the gold standard for establishing a definitive diagnosis, this case highlights the significance of applying clinical context to pathologic interpretation and medical decision‐making. Prior to any diagnostic procedure, the patient's history of dwarfism, recurrent infections, and refractory ITP provided clues to an immunodeficiency syndrome, CHH. Knowledge of this immunodeficiency might have better informed the initial pathologic interpretation of atypical cells, which were misread as adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, awareness of the patient's profound immunodeficiency would have given pause to proceeding with invasive surgery without prior Ig and antibiotic support and may have averted a fatal outcome.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Infiltrative hepatobiliary diseases may manifest with isolated elevations in ALP.

- Granulomas and autoimmune cytopenias may be features of primary immunodeficiency states.

- A history of recurrent childhood infections should raise suspicion for congenital immunodeficiencies.

- Unique medical complications, including immunodeficiency, can be associated with dwarfism subtypes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer M. Puck, MD, from the University of California San Francisco, Departments of Immunology and Pediatrics, for her invaluable contribution to the discussion on immunodeficiencies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

A 41‐year‐old woman with dwarfism was referred for evaluation of an isolated elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 792 U/L (normal value, 3195 U/L) and a gamma‐glutamyl transferase (GGT) of 729 U/L (normal value, 737 U/L), found incidentally on routine laboratory screening. She denied any fevers, chills, weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting.

The presence of an isolated ALP elevation, presumably of hepatobiliary origin given the increase in GGT, in a relatively young woman immediately calls to mind the diagnosis of primary biliary cirrhosis, and I would specifically inquire about pruritus, which occurs commonly in this setting. The absence of abdominal pain argues against the diagnosis of extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Other processes that could result in this asymptomatic presentation include infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, and other causes of granulomatous hepatitis. The absence of systemic symptoms makes disseminated infection or malignancy with hepatic involvement less likely. I would query whether underlying dwarfism can be associated with metabolic abnormalities that cause infiltrative liver disease, functional or anatomical hepatobiliary abnormalities, or malignancy.

The patient's medical history was notable for chronic constipation, allergic rhinitis, and basal‐cell carcinoma. She had reconstructive surgeries of the left hip and knee 28 years ago without complications. She underwent a right total hip replacement for hip dysplasia 6 months prior, which was complicated by a postoperative joint infection with Enterobacter cloacae. The hardware was retained, and she was treated with incision and drainage and a prolonged fluoroquinolone course. Furthermore, she had a history of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), which manifested at the age of 20 years. A bone‐marrow biopsy at that time showed no evidence of hematologic malignancy. For her ITP, she had initially received intravenous immunoglobulin (Ig) and cyclosporine without sustained benefit. She underwent a splenectomy at the age of 26 years and was treated intermittently with rituximab over 11 years prior to admission. Her medications included cetirizine. Her parents were nonconsanguineous, of European and Southeast Asian ancestry, and healthy. She was in a long‐term monogamous relationship. The patient had been employed as an educator.

The history of immune‐mediated thrombocytopenia raises the possibility that the present illness may be part of a broader autoimmune diathesis. Other causes of secondary ITP, such as drug‐induced reactions, hematologic malignancies, and viral infections, are unlikely, as her ITP has been persistent for more than 20 years. She has not evolved into a common phenotypic pattern of autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus after the appearance of ITP, nor does she endorse a history of thromboembolic complications that would suggest antiphospholipid syndrome.

Ultrasound of the abdomen demonstrated narrowing of the extrahepatic biliary duct in the region of the pancreas without evidence of a mass lesion. Computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis similarly showed mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with narrowing of the extrahepatic duct in the region of the pancreas without apparent pancreatic mass. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) confirmed a stricture in the distal common bile duct and dilatation of the common bile duct. Cytology brushings obtained during ERCP showed groups of overlapping, enlarged cells with pleomorphic irregular nuclei, one or more prominent nucleoli, and focal nuclear molding, leading to a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Figure 1).

The absence of jaundice and pruritus indicates incomplete biliary obstruction. Commonbile duct strictures are most commonly seen after manipulation of the biliary tree. Neoplasms including pancreatic cancer, adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater, and cholangiocarcinoma may cause compression and obstruction of the common bile duct, as well as stricture formation mediated by a desmoplastic reaction to the tumor. Occasionally, metastatic malignancy or lymphoma may involve the porta hepatis and cause extrinsic compression of the common bile duct. Other etiologies of strictures include sclerosing cholangitis and opportunistic infections such as Cryptosporidium, cytomegalovirus, and microsporidiosis, which are not supported by this patient's history.

The atypical cells seen on ERCP brushings were interpreted as evidence of cholangiocarcinoma. The patient underwent a pylorus‐sparing Whipple procedure. Examination of the surgical pathology specimens revealed diffuse non‐necrotizing granulomatous inflammation involving the bile duct and gallbladder (Figure 2). There was focal atypia of the bile‐duct epithelial cells, but no evidence of malignancy. There were non‐necrotizing granulomas in numerous lymph nodes, some with significant sclerosis; stains and cultures for acid‐fast bacilli and fungi were negative, and stains for IgG4 and CD1a for Langerhans‐cell histiocytosis were negative.

Granulomatous inflammation may be caused by a variety of intracellular infections, environmental and occupational exposures, and drug hypersensitivity, or may be associated with malignancy such as lymphoma. In the absence of an alternative explanation, the presence of non‐necrotizing granulomas in multiple organs suggests the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, even if classic intrathoracic involvement is not present. Hepatic involvement with sarcoidosis is common but rarely symptomatic, whereas biliary disease is distinctly uncommon. Interestingly, there is an association between both primary biliary cirrhosis and sclerosing cholangitis with sarcoidosis. The pathologic findings could indicate an autoimmune process that has led to widespread granulomas with this unusual distribution. Disseminated infections such as mycobacterial or fungal diseases seem much less plausible in this woman, who had no prior systemic complaints. The atypical cells seen on the ERCP brushings were almost certainly caused by inflammation and a fibroproliferative response rather than malignancy.

On further questioning, the patient endorsed a history of multiple childhood ear infections that required bilateral myringotomy tubes, and multiple episodes of sinusitis, but both problems improved in adulthood. She had experienced 2 episodes of dermatomal zoster in her lifetime. She also noted frequent vaginal yeast infections. She denied any history of pneumonias or thrush. In her second decade of life, she developed allergic rhinitis and eczema. She denied any chemical or environmental exposures. She had had negative tuberculin skin tests as part of her occupational screening and denied any recent travel.

The additional history of recurrent upper‐respiratory infections early in life and subsequent episodes of dermatomal zoster and candidal infections increases the likelihood that this patient has a primary immunodeficiency. A combined cellular and humoral immunodeficiency would predispose to both bacterial sinopulmonary infections, generally a result of Ig isotype or IgG subclass deficiencies, and recurrent zoster and candidal infection. Any evaluation of her Igs at this time may be confounded by her receipt of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy, which may decrease serum Ig levels.

The relatively benign course in terms of infection is consistent with the heterogeneous immunodeficiencies classified as combined immunodeficiency (CID), a less‐penetrant phenotype of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), or common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Autoimmunity is a frequent manifestation of CID and CVID, and affected patients have an increased risk of lymphoma and other malignancies. Granulomatous disease may also be a manifestation of both CID and CVID.

Postoperatively, she developed progressive abdominal distension and pain. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis showed colonic dilatation consistent with Ogilvie pseudo‐obstruction. On postoperative day 9, she developed fevers. On physical examination, her temperature was 38.5C, the blood pressure was 104/56 mm Hg, and the heart rate was 131 beats per minute. Her oxygen saturation was 95% on room air. Her height was 105 cm. She had diffuse alopecia without scarring. She did not have a malar rash or oral ulcerations. Both lungs were clear to auscultation. A cardiac examination showed tachycardia with a regular rhythm, normal heart sounds, and no murmurs. Her musculoskeletal exam was notable for short limbs and phalanges, without synovitis. Bilateral hip exam demonstrated internal and external range of motion without abnormalities. No rashes were present. Her abdominal exam revealed diffuse tenderness with postoperative drains in place. She had nonbloody loose stools.

Although autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis can rarely manifest with fevers, evaluation of postoperative fever in this patient should focus first on common processes that also occur in immunocompetent patients. Since she has had a splenectomy and we are now suspicious of an underlying immunodeficiency, appropriate cultures should be obtained and broad‐spectrum intravenous antibiotics should be initiated without delay. The presence of nonscarring alopecia could either represent autoimmune alopecia, if the onset was recent, or it could be part of this patient's underlying skeletal dysplasia syndrome.

Piperacillin/tazobactam and oral metronidazole were started for presumed intra‐abdominal infection. The white cell count was 20,500/mm3 with 96% neutrophils, 1.4% lymphocytes with an absolute lymphocyte count 0.33 109/L (normal value, >1.0 109/L), and 2.6% monocytes. The hematocrit was 27.8% with a mean corpuscular volume of 95 fL. The platelet count was 323,000/mm3. Serum aminotransferase and total bilirubin levels were normal, and ALP was 904 U/L. The serum albumin was 1.2 g/dL (normal value, 3.54.8 g/dL) and prealbumin was 6 mg/dL (normal value, 2037 mg/dL).

Blood cultures returned positive for E. cloacae. Clostridium difficile toxin assay was negative. Piperacillin/tazobactam was switched to meroperem, and metronidazole was discontinued. She continued to have fevers, and on postoperative day 16, repeat blood cultures and urine cultures grew Candida albicans; caspofungin was initiated.

In addition to the neutrophilic leukocytosis in response to gram‐negative bacteremia, there is marked lymphopenia. Although sepsis may cause transient declines in the total lymphocyte count, I do not believe that this entirely accounts for such severe lymphopenia. The albumin is also profoundly low. Her catabolic postsurgical state might explain part of this abnormality, but taken together with her prior gastrointestinal symptoms, these findings could be consistent with intestinal malabsorption or a protein‐losing enteropathy, which can also be associated with primary immunodeficiency.

Serum angiotensin‐converting enzyme was 32 U/L (normal value, 967 U/L). A CT of the chest was performed and did not reveal mediastinal lymphadenopathy, nodules, or consolidations. Antinuclear, antismooth muscle, and antimitochondrial antibodies were negative. Human immunodeficiency virus antibody was negative. Serum quantitative Igs, including IgG, IgM, IgA, and IgE, were undetectable.

Serum lymphocyte subset analysis revealed a CD3 T‐cell count of 101 106/L (normal value, >690 106/L), CD4 T cells 46 106/L (normal value, >410 106/L), CD8 T cells 55 106/L (normal value, >190 106/L), CD19 B cells undetectable at 2 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L), CD16 CD56 NK cells 134 106/L (normal value, >90 106/L). T‐cell lymphocyte proliferation assay showed a completely absent response to candida and tetanus antigens, and a very low response to mitogens.

The immunologic evaluation is confounded by her critical illness and by the prior administration of anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody. Despite these caveats, the results of these studies are profoundly abnormal and suggest a combined B‐cell and T‐cell immunodeficiency that is more severe from a laboratory standpoint than her history prior to surgery has suggested. Low T lymphocyte numbers, with or without functional abnormalities, are a hallmark of CID and can be also be seen in CVID. The extremely low Ig levels in the presence of severe infections warrant replacement with intravenous Ig.

Combined immunodeficiency and CVID may be associated with a number of mutations; elucidating the genetics and molecular mechanism of immunodeficiency may be important in identifying patients whose immunodeficiency may be cured by stem‐cell transplantation.

Intravenous Ig was administered. Her serum was sent for sequencing of the RMRP gene, mutations of which are found in patients who have cartilage‐hair hypoplasia (CHH), a rare autosomal recessive skeletal dysplasia characterized by short‐limbed dwarfism; fine, sparse hair; and variable degrees of immunodeficiency. She was found to have 2 RMRP mutations, a 126 CT transition and a 218 AC transversion.

The patient developed multiple abdominal abscesses, which were drained and grew vancomycin‐resistant enterococcus (VRE) and C. albicans. Blood cultures also turned positive for VRE. A colonoscopy was performed because of radiographic evidence suggestive of colitis. Biopsies taken from the colonoscopy were negative for cytomegalovirus or other infections, but did reveal rare non‐necrotizing granulomas. The patient developed progressive multiorgan failure requiring mechanical ventilation and continuous venovenous hemofiltration. On postoperative day 36, the patient was transitioned to comfort care, and she expired the next day. A unifying diagnosis of CHH‐related immunodeficiency and disseminated granulomatous disease, complicated by postoperative sepsis, was made. An autopsy was declined.

COMMENTARY

Evaluation of abnormal liver tests is a frequent diagnostic challenge faced by clinicians in both ambulatory and inpatient settings. Identifying the pattern of liver injuryhepatocellular, cholestatic, or infiltrativemay guide the initial workup. This patient's presentation of a normal bilirubin and transaminases with elevations in ALP was consistent with infiltrative hepatic disease. The radiographic finding of extrahepatic biliary strictures, on the other hand, raised concern for an obstructive etiology and prompted an ERCP. Brush cytology has high specificity for malignancy, but interpretation of atypical cells can rarely be inconclusive or be associated with false positives.[1]

The suspicion for infiltrative hepatitis was supported postoperatively by the discovery of diffuse hepatobiliary granulomatous disease, which can be associated with a spectrum of disease states including sarcoidosis, autoimmune disorders, intracellular infections, immunodeficiency, malignancy, environmental or occupational exposures, and drug reactions.[2, 3] During the patient's hospital course and case presentation to the discussant, the possibility of sarcoidosis was raised based on the operative findings. Additional history‐taking was essential to evaluate other etiologies of granulomatous inflammation, and this clinical correlation prevented a second erroneous pathologic diagnosis.

Multiple elements of this patient's presentation led to recognition of an underlying primary immunodeficiency. Her prior history of recurrent childhood infections, dermatomal zoster, and vaginal infections suggested a congenital immunodeficiency. The additional features of refractory autoimmune cytopenias (ie, ITP), granulomatous inflammation, undetectable serum Igs, and low T‐cell and B‐cell counts, were consistent with CID or CVID. By definition, CID involves defects in both B and T cells; CVID represents a predominantly B‐cell disorder characterized by abnormalities in Ig production, though concomitant T‐cell dysfunction may also be found.[4] It is worth noting that although this patient had previously received anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody, which depletes CD20‐positive B lymphocytes, Ig levels are not typically depleted by anti‐CD20 unless there is preexisting antibody deficiency.[5]

We were able to make the unifying diagnosis of CHH to explain her constellation of physical findings, laboratory abnormalities, and histopathology. Also known as McKusick type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia, CHH has a relatively high carrier frequency in the Amish (1:19) and Finnish (1:76) populations.[6, 7] Additional clinical features can include gastrointestinal disorders, poorly pigmented skin and hair, and joint disorders. Dysregulation of immunity is a particular challenge and can be manifested by malignancy, lymphoproliferative disease, cytopenias, or primary immunodeficiencies. Combined immunodeficiency and T cellmediated defects are most common, although there are case reports of CHH associated with severe humoral defects.[8, 9] Primary immunodeficiency, if severe and recognized early, can be treated with bone‐marrow transplantation.[10, 11] Granulomatous inflammation also has been described in CHH.[12]

Although tissue biopsy is often viewed as the gold standard for establishing a definitive diagnosis, this case highlights the significance of applying clinical context to pathologic interpretation and medical decision‐making. Prior to any diagnostic procedure, the patient's history of dwarfism, recurrent infections, and refractory ITP provided clues to an immunodeficiency syndrome, CHH. Knowledge of this immunodeficiency might have better informed the initial pathologic interpretation of atypical cells, which were misread as adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, awareness of the patient's profound immunodeficiency would have given pause to proceeding with invasive surgery without prior Ig and antibiotic support and may have averted a fatal outcome.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Infiltrative hepatobiliary diseases may manifest with isolated elevations in ALP.

- Granulomas and autoimmune cytopenias may be features of primary immunodeficiency states.

- A history of recurrent childhood infections should raise suspicion for congenital immunodeficiencies.

- Unique medical complications, including immunodeficiency, can be associated with dwarfism subtypes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer M. Puck, MD, from the University of California San Francisco, Departments of Immunology and Pediatrics, for her invaluable contribution to the discussion on immunodeficiencies.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , , . Brush cytology of ductal strictures during ERCP. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2000;63:254–259.

- , . Granulomatous lung disease: an approach to the differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134;667–690.

- James DG, Zumla A, eds. The Granulomatous Disorders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999:17–27.

- , , , et al. Unraveling the complexity of T cell abnormalities in common variable immunodeficiency. J Immunol. 2007;178:3932–3943.

- , , , et al. Does rituximab aggravate pre‐existing hypogammaglobulinaemia? J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:275–277.

- . Cartilage‐hair hypoplasia in Finland: epidemiological and genetic aspects of 107 patients. J Med Genet. 1992;29:652–655.

- , , , et al. High‐resolution genetic mapping of the cartilage‐hair hypoplasia (CHH) gene in Amish and Finnish families. Genomics. 1994;20:347–353.

- , , , et al. Combined immunodeficiency and vaccine‐related poliomyelitis in a child with cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. J Pediatr. 1975;86:868–872.

- , , . Deficiency of humoral immunity in cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. J Pediatr. 2000;137:487–492.

- , , , , . Bone marrow transplantation for cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:751–756.

- , , , et al. Clinical and immunologic outcome of patients with cartilage hair hypoplasia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [published corrections appear in Blood. 2010;116:2402 and Blood. 2011;117:2077]. Blood. 2010;116:27–35.

- , , , et al. Granulomatous inflammation in cartilage‐hair hypoplasia: risks and benefits of anti‐TNF‐α mAbs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:847–853.

- , , , . Brush cytology of ductal strictures during ERCP. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2000;63:254–259.

- , . Granulomatous lung disease: an approach to the differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134;667–690.

- James DG, Zumla A, eds. The Granulomatous Disorders. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999:17–27.

- , , , et al. Unraveling the complexity of T cell abnormalities in common variable immunodeficiency. J Immunol. 2007;178:3932–3943.

- , , , et al. Does rituximab aggravate pre‐existing hypogammaglobulinaemia? J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:275–277.

- . Cartilage‐hair hypoplasia in Finland: epidemiological and genetic aspects of 107 patients. J Med Genet. 1992;29:652–655.

- , , , et al. High‐resolution genetic mapping of the cartilage‐hair hypoplasia (CHH) gene in Amish and Finnish families. Genomics. 1994;20:347–353.

- , , , et al. Combined immunodeficiency and vaccine‐related poliomyelitis in a child with cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. J Pediatr. 1975;86:868–872.

- , , . Deficiency of humoral immunity in cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. J Pediatr. 2000;137:487–492.

- , , , , . Bone marrow transplantation for cartilage‐hair hypoplasia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:751–756.

- , , , et al. Clinical and immunologic outcome of patients with cartilage hair hypoplasia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [published corrections appear in Blood. 2010;116:2402 and Blood. 2011;117:2077]. Blood. 2010;116:27–35.

- , , , et al. Granulomatous inflammation in cartilage‐hair hypoplasia: risks and benefits of anti‐TNF‐α mAbs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:847–853.

Teamwork Key to Effective Interdisciplinary Rounds

A new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine is among the first to assess and characterize the effectiveness of teamwork in interdisciplinary rounds (IDR). The upshot: Varied performance on rounds suggests a need to improve the consistency of teamwork.

The report, "Assessment of Teamwork During Structured Interdisciplinary Rounds on Medical Units," adapted the Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery (OTAS) behavioral rating scale tool to evaluate and characterize teamwork of hospitalists. Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says the review shows that mere implementation of IDR is not enough. Physician leaders must occasionally check how the rounds operate to ensure against such roadblocks as a team member who dominates discussions, or the formation of hierarchal relationships that not everyone is comfortable participating in, he says.

"You can't just say, 'Oh, we're practicing teamwork, we have structured interdisciplinary rounds,'" says Dr. Williams, who credits the research to lead author Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, also of Feinberg. "You need to ensure that it’s occurring."

The paper fills a gap in research, the authors write, as much of the prior work on IDR has focused on patient outcomes, cost, and length of stay. But Dr. Williams says he doesn't expect community hospital medicine groups to conduct similar research because of their busy schedules. Still, he hopes group leaders and administrators consider the research an impetus to periodically check those rounds.

"Even in an institution [like Northwestern] that has strong buy-in to this [teamwork], you need to go back and check," Dr. Williams adds. "We saw variation in performance and we realized we needed to do some retraining."

Visit our website for more information about interdisciplinary rounds.

A new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine is among the first to assess and characterize the effectiveness of teamwork in interdisciplinary rounds (IDR). The upshot: Varied performance on rounds suggests a need to improve the consistency of teamwork.

The report, "Assessment of Teamwork During Structured Interdisciplinary Rounds on Medical Units," adapted the Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery (OTAS) behavioral rating scale tool to evaluate and characterize teamwork of hospitalists. Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says the review shows that mere implementation of IDR is not enough. Physician leaders must occasionally check how the rounds operate to ensure against such roadblocks as a team member who dominates discussions, or the formation of hierarchal relationships that not everyone is comfortable participating in, he says.

"You can't just say, 'Oh, we're practicing teamwork, we have structured interdisciplinary rounds,'" says Dr. Williams, who credits the research to lead author Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, also of Feinberg. "You need to ensure that it’s occurring."

The paper fills a gap in research, the authors write, as much of the prior work on IDR has focused on patient outcomes, cost, and length of stay. But Dr. Williams says he doesn't expect community hospital medicine groups to conduct similar research because of their busy schedules. Still, he hopes group leaders and administrators consider the research an impetus to periodically check those rounds.

"Even in an institution [like Northwestern] that has strong buy-in to this [teamwork], you need to go back and check," Dr. Williams adds. "We saw variation in performance and we realized we needed to do some retraining."

Visit our website for more information about interdisciplinary rounds.

A new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine is among the first to assess and characterize the effectiveness of teamwork in interdisciplinary rounds (IDR). The upshot: Varied performance on rounds suggests a need to improve the consistency of teamwork.

The report, "Assessment of Teamwork During Structured Interdisciplinary Rounds on Medical Units," adapted the Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery (OTAS) behavioral rating scale tool to evaluate and characterize teamwork of hospitalists. Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, professor and chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says the review shows that mere implementation of IDR is not enough. Physician leaders must occasionally check how the rounds operate to ensure against such roadblocks as a team member who dominates discussions, or the formation of hierarchal relationships that not everyone is comfortable participating in, he says.

"You can't just say, 'Oh, we're practicing teamwork, we have structured interdisciplinary rounds,'" says Dr. Williams, who credits the research to lead author Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, also of Feinberg. "You need to ensure that it’s occurring."

The paper fills a gap in research, the authors write, as much of the prior work on IDR has focused on patient outcomes, cost, and length of stay. But Dr. Williams says he doesn't expect community hospital medicine groups to conduct similar research because of their busy schedules. Still, he hopes group leaders and administrators consider the research an impetus to periodically check those rounds.

"Even in an institution [like Northwestern] that has strong buy-in to this [teamwork], you need to go back and check," Dr. Williams adds. "We saw variation in performance and we realized we needed to do some retraining."

Visit our website for more information about interdisciplinary rounds.

ITL: Physician Reviews of HM-Relevant Research

Clinical question: Is there a difference between aspirin and warfarin in preventing thromboembolic complications and risk of bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF)?

Background: Data are lacking on risks and benefits of aspirin and warfarin in CKD, as this group of patients largely has been excluded from anticoagulation therapy trials for NVAF. This study examined the risks and benefits of aspirin and warfarin in patients with CKD with NVAF.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Danish National Registries.

Synopsis: Of 132,372 patients with NVAF, 2.7% had CKD and 0.7% had end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Compared to patients with no CKD, there was increased risk of stroke or systemic thromboembolism in patients with ESRD (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.57-2.14) and with non-end-stage CKD (HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.38-1.59).

In patients with CKD, warfarin significantly reduced stroke risk (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.64-0.91) and significantly increased bleeding risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.16-1.53); aspirin significantly increased bleeding risk (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.02-1.34), with no reduction in stroke risk.

Bottom line: CKD was associated with an increased risk of stroke among NVAF patients. While both aspirin and warfarin were associated with increased risk of bleeding, there was a reduction in the risk of stroke with warfarin, but not with aspirin.

Citation: Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, et al. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):625-635.

Click here for more physician reviews of HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Is there a difference between aspirin and warfarin in preventing thromboembolic complications and risk of bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF)?

Background: Data are lacking on risks and benefits of aspirin and warfarin in CKD, as this group of patients largely has been excluded from anticoagulation therapy trials for NVAF. This study examined the risks and benefits of aspirin and warfarin in patients with CKD with NVAF.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Danish National Registries.

Synopsis: Of 132,372 patients with NVAF, 2.7% had CKD and 0.7% had end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Compared to patients with no CKD, there was increased risk of stroke or systemic thromboembolism in patients with ESRD (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.57-2.14) and with non-end-stage CKD (HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.38-1.59).

In patients with CKD, warfarin significantly reduced stroke risk (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.64-0.91) and significantly increased bleeding risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.16-1.53); aspirin significantly increased bleeding risk (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.02-1.34), with no reduction in stroke risk.

Bottom line: CKD was associated with an increased risk of stroke among NVAF patients. While both aspirin and warfarin were associated with increased risk of bleeding, there was a reduction in the risk of stroke with warfarin, but not with aspirin.

Citation: Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, et al. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):625-635.

Click here for more physician reviews of HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Is there a difference between aspirin and warfarin in preventing thromboembolic complications and risk of bleeding in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF)?

Background: Data are lacking on risks and benefits of aspirin and warfarin in CKD, as this group of patients largely has been excluded from anticoagulation therapy trials for NVAF. This study examined the risks and benefits of aspirin and warfarin in patients with CKD with NVAF.

Study design: Retrospective, observational cohort study.

Setting: Danish National Registries.

Synopsis: Of 132,372 patients with NVAF, 2.7% had CKD and 0.7% had end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Compared to patients with no CKD, there was increased risk of stroke or systemic thromboembolism in patients with ESRD (HR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.57-2.14) and with non-end-stage CKD (HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.38-1.59).

In patients with CKD, warfarin significantly reduced stroke risk (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.64-0.91) and significantly increased bleeding risk (HR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.16-1.53); aspirin significantly increased bleeding risk (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.02-1.34), with no reduction in stroke risk.

Bottom line: CKD was associated with an increased risk of stroke among NVAF patients. While both aspirin and warfarin were associated with increased risk of bleeding, there was a reduction in the risk of stroke with warfarin, but not with aspirin.

Citation: Olesen JB, Lip GY, Kamper AL, et al. Stroke and bleeding in atrial fibrillation with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(7):625-635.

Click here for more physician reviews of HM-relevant literature.

Quality Improvement Project Helps Hospital Patients Get Needed Prescriptions

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

12 Things Hospitalists Need to Know About Billing and Coding

Documentation, CPT codes, modifiers—it’s not glamorous, but it’s an integral part of a 21st-century physician’s job description. The Hospitalist queried more than a handful of billing and coding experts about the advice they would dispense to clinicians navigating the reimbursement maze.

“Physicians often do more than what is reflected in the documentation,” says Barb Pierce, CCS-P, ACS-EM, a national coding consultant based in West Des Moines, Iowa, and CODE-H faculty. “They can’t always bill for everything they do, but they certainly can document and code to obtain the appropriate levels of service.”

Meanwhile, hospitalists have to be careful they aren’t excessive in their billing practices. “The name of the game isn’t just to bill higher,” Pierce adds, “but to make sure that your documentation supports the service being billed, and Medicare is watching. They’re doing a lot of focused audits.”

Some hospitalists might opt for a lower level of service, suspecting they’re less likely to be audited. Other hospitalists might seek reimbursement for more of their time and efforts.

“You have both ends of the spectrum,” says Raemarie Jimenez, CPC, CPMA, CPC-I, CANPC, CRHC, director of education for AAPC, formerly known as the American Academy of Professional Coders. “There are a lot of factors that would go into why a provider would code something incorrectly.”

Here’s how to land somewhere in the middle.

1 Be thorough in documenting the initial hospital visit.