User login

Hospital Medicine Groups Must Determine Tolerance Levels for Workload, Night Work

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Our group is considering hiring another nocturnist. This may reduce the number of shifts that hospitalists will be able to work per month—we have some who work 20 or more shifts per month. While the vast majority of hospitalists would welcome a nocturnist in order to decrease the number of night shifts required, some who work a lot of shifts are concerned that their income will be affected since there won’t necessarily be any day shifts available to compensate for the decrease in night shifts.

I am wondering if there is a maximum number of shifts per month that a hospitalist should not exceed. We work 12-hour shifts. In other words, is there a tipping point when too many shifts starts to negatively impact the quality of work, increase length of stay, decrease patient satisfaction, and lead to physician burnout? Are there any studies or data to look at this question?

Your feedback is very much appreciated.

–Donna Ting, MD, MPH

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Although many jobs (i.e. air-traffic controllers, truck drivers) use hours worked as a gauge of operator fatigue, physicians traditionally have not used these criteria to judge one’s ability to be effective. That being said, we all know of occasions when we were physically and/or mentally exhausted and not performing at our best.

Multiple studies have shown that physicians tend to work an average of 60 hours a week. Of course, this does not take into consideration the typical hospitalist, who still tends to work 12-hour shifts on a seven-on/seven-off schedule, although there is a trend away from this type of block scheduling. A recent study also showed that physicians in practice less than five years were more likely to work hours in agreement with the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty-hour regulations for physicians in training. The authors speculated that this was due to this group having trained under the new ACGME guidelines and being of Generation X, whose members tend to favor more work-life balance than their predecessors.

Several studies have examined physician work hours in relationship to fatigue and patient safety. Volp et al examined two large studies and found no change in mortality among Medicare patients for the first two years after implementation of the ACGME duty-hour regulations. However, they did find that mortality decreased for four common medical conditions in a VA hospital. Fletcher et al performed a systematic review and found no conclusive evidence that the decreased resident work hours had any affect on patient safety.

This is what I would have expected: inconclusive data. Most studies of this type are surveys, which have well-known limitations. Each of us has our own individual stamina, tolerance for fatigue, and desire for work-life balance. We intuitively know that most individuals are not at their best when tired or stressed, but to capture the true effect of these variables on patient satisfaction, morbidity, mortality, and other clinical metrics will be very difficult.

There are several ways I would approach a group that is contemplating another nocturnist. Because most hospitalists don’t want to work nights, the group members who feel their moonlighting income would be affected should commit to covering a certain portion or all of the available nights. If only some of the nights are covered, then you can hire a part-time nocturnist.

This is easier than you might imagine, as my very large hospitalist group has four nocturnists and none work a full FTE. I think three to four extra shifts a month are reasonable on a routine basis. We have, however, allowed physicians who wanted to have a month off to work seven extra days the months before and after to get their desired time off. We would not allow that to occur on a regular basis.

Ultimately, your group has to decide its own tolerance for fatigue and burnout, and have some mechanism to monitor the quality of work. After all, we owe it to our patients to not place their safety in jeopardy.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Our group is considering hiring another nocturnist. This may reduce the number of shifts that hospitalists will be able to work per month—we have some who work 20 or more shifts per month. While the vast majority of hospitalists would welcome a nocturnist in order to decrease the number of night shifts required, some who work a lot of shifts are concerned that their income will be affected since there won’t necessarily be any day shifts available to compensate for the decrease in night shifts.

I am wondering if there is a maximum number of shifts per month that a hospitalist should not exceed. We work 12-hour shifts. In other words, is there a tipping point when too many shifts starts to negatively impact the quality of work, increase length of stay, decrease patient satisfaction, and lead to physician burnout? Are there any studies or data to look at this question?

Your feedback is very much appreciated.

–Donna Ting, MD, MPH

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Although many jobs (i.e. air-traffic controllers, truck drivers) use hours worked as a gauge of operator fatigue, physicians traditionally have not used these criteria to judge one’s ability to be effective. That being said, we all know of occasions when we were physically and/or mentally exhausted and not performing at our best.

Multiple studies have shown that physicians tend to work an average of 60 hours a week. Of course, this does not take into consideration the typical hospitalist, who still tends to work 12-hour shifts on a seven-on/seven-off schedule, although there is a trend away from this type of block scheduling. A recent study also showed that physicians in practice less than five years were more likely to work hours in agreement with the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty-hour regulations for physicians in training. The authors speculated that this was due to this group having trained under the new ACGME guidelines and being of Generation X, whose members tend to favor more work-life balance than their predecessors.

Several studies have examined physician work hours in relationship to fatigue and patient safety. Volp et al examined two large studies and found no change in mortality among Medicare patients for the first two years after implementation of the ACGME duty-hour regulations. However, they did find that mortality decreased for four common medical conditions in a VA hospital. Fletcher et al performed a systematic review and found no conclusive evidence that the decreased resident work hours had any affect on patient safety.

This is what I would have expected: inconclusive data. Most studies of this type are surveys, which have well-known limitations. Each of us has our own individual stamina, tolerance for fatigue, and desire for work-life balance. We intuitively know that most individuals are not at their best when tired or stressed, but to capture the true effect of these variables on patient satisfaction, morbidity, mortality, and other clinical metrics will be very difficult.

There are several ways I would approach a group that is contemplating another nocturnist. Because most hospitalists don’t want to work nights, the group members who feel their moonlighting income would be affected should commit to covering a certain portion or all of the available nights. If only some of the nights are covered, then you can hire a part-time nocturnist.

This is easier than you might imagine, as my very large hospitalist group has four nocturnists and none work a full FTE. I think three to four extra shifts a month are reasonable on a routine basis. We have, however, allowed physicians who wanted to have a month off to work seven extra days the months before and after to get their desired time off. We would not allow that to occur on a regular basis.

Ultimately, your group has to decide its own tolerance for fatigue and burnout, and have some mechanism to monitor the quality of work. After all, we owe it to our patients to not place their safety in jeopardy.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Dear Dr. Hospitalist:

Our group is considering hiring another nocturnist. This may reduce the number of shifts that hospitalists will be able to work per month—we have some who work 20 or more shifts per month. While the vast majority of hospitalists would welcome a nocturnist in order to decrease the number of night shifts required, some who work a lot of shifts are concerned that their income will be affected since there won’t necessarily be any day shifts available to compensate for the decrease in night shifts.

I am wondering if there is a maximum number of shifts per month that a hospitalist should not exceed. We work 12-hour shifts. In other words, is there a tipping point when too many shifts starts to negatively impact the quality of work, increase length of stay, decrease patient satisfaction, and lead to physician burnout? Are there any studies or data to look at this question?

Your feedback is very much appreciated.

–Donna Ting, MD, MPH

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Although many jobs (i.e. air-traffic controllers, truck drivers) use hours worked as a gauge of operator fatigue, physicians traditionally have not used these criteria to judge one’s ability to be effective. That being said, we all know of occasions when we were physically and/or mentally exhausted and not performing at our best.

Multiple studies have shown that physicians tend to work an average of 60 hours a week. Of course, this does not take into consideration the typical hospitalist, who still tends to work 12-hour shifts on a seven-on/seven-off schedule, although there is a trend away from this type of block scheduling. A recent study also showed that physicians in practice less than five years were more likely to work hours in agreement with the 2003 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) duty-hour regulations for physicians in training. The authors speculated that this was due to this group having trained under the new ACGME guidelines and being of Generation X, whose members tend to favor more work-life balance than their predecessors.

Several studies have examined physician work hours in relationship to fatigue and patient safety. Volp et al examined two large studies and found no change in mortality among Medicare patients for the first two years after implementation of the ACGME duty-hour regulations. However, they did find that mortality decreased for four common medical conditions in a VA hospital. Fletcher et al performed a systematic review and found no conclusive evidence that the decreased resident work hours had any affect on patient safety.

This is what I would have expected: inconclusive data. Most studies of this type are surveys, which have well-known limitations. Each of us has our own individual stamina, tolerance for fatigue, and desire for work-life balance. We intuitively know that most individuals are not at their best when tired or stressed, but to capture the true effect of these variables on patient satisfaction, morbidity, mortality, and other clinical metrics will be very difficult.

There are several ways I would approach a group that is contemplating another nocturnist. Because most hospitalists don’t want to work nights, the group members who feel their moonlighting income would be affected should commit to covering a certain portion or all of the available nights. If only some of the nights are covered, then you can hire a part-time nocturnist.

This is easier than you might imagine, as my very large hospitalist group has four nocturnists and none work a full FTE. I think three to four extra shifts a month are reasonable on a routine basis. We have, however, allowed physicians who wanted to have a month off to work seven extra days the months before and after to get their desired time off. We would not allow that to occur on a regular basis.

Ultimately, your group has to decide its own tolerance for fatigue and burnout, and have some mechanism to monitor the quality of work. After all, we owe it to our patients to not place their safety in jeopardy.

Do you have a problem or concern that you’d like Dr. Hospitalist to address? Email your questions to [email protected].

Letters: Are Lean Management Principles Going Astray in Health Care?

I was receiving PT for a shoulder problem. Jenna, my physical therapist, asked if I injured it working. I said no, my work involves writing and lecturing on Lean management, quality, and things related. Has Lean made it to this health center? I asked. Nodding, she replied impishly, “You said a bad word.”

After a late start in health care, Lean has cut a wide swath in the sector. Health care took its Lean lessons from industry, which had imported just-in-time (JIT) production from Japan in the 1980s, then renamed it Lean manufacturing in the 1990s. Off-the-mark tendencies for Lean as applied in manufacturing have, unfortunately, been carried over into health care. Sensible corrective measures are needed to ensure that Lean in health care does not suffer pain and an early death. Actually, the metaphor is apt in that Lean’s most beneficial outcome is reduction of wait times, and when it comes to health care, long wait times surely can and do kill people.

Since Lean’s introduction in the West three decades ago, it has been redefined, amended, and appended to the point some its lesser features have trumped what is meaningful to patients. Manufacturing has the excuse that end customers are nowhere in sight. Health care, on the other hand, is customer-facing. Lean’s customer-centered primary effects should make it doubly suitable in the health-care sector.

Although Lean manufacturing generally is viewed as a success story, my own multiyear “Leanness studies” reveal dominant patterns of good results followed by backsliding. A likely reason: Most present Lean in operational terms, so manufacturing executives delegate it down the hierarchy to the operations contingent. The same is generally the case where Lean has been applied in health care.

Corrective action calls for making it clear that Lean’s main effects are not operational so much as competitive and strategic. That is, the primary role and outcomes are delivering ever-quicker, more flexible, higher-quality, higher-value response to customer needs, demands, orders, and usage. Rather than seeing Lean this way, industry generally has adopted the view that Lean mainly is about reduction of the “seven wastes.” Falling in line, health care, too, has adopted waste elimination as Lean’s mantra.

That won’t do.

Rather than being Lean’s essence, waste reduction is akin to spaghetti diagrams, the five whys, value-stream mapping, and non-value-add analysis. All are worthy ways of framing the Lean pursuit but are not among the methodologies that act on the processes to change them from fat to lean. Over the years, some have done a better job implementing Lean, spending less time on framing and more on training employees in organization by product family or customer family, quick setup, cross-training/job rotation, trouble lights, and more, then saying, “Go do it.”

In getting it done, Lean delivers quick response as the dominant customer-sensitive effect: Nearly every change that Lean elicits reduces waiting times and waiting lines, and the sum total of those reductions through the processes can speed up customer response by an order of magnitude.

In delivering quick response in any setting, Lean relies on flexibility and quality. Given the norm—that customer demands and needs are highly variable, both in type and quantity—quick response requires flexibility so as to ensure immediate readiness for the next customer or need. Lean provides flexibility through a cross-trained or on-call workforce, plus fast-change or standby equipment. As for quality, without it, response is slowed or stopped for rework. Or abandoned entirely, with the customer seeking service elsewhere. Or the patient dies waiting.

There are reasons why waste reduction has been elevated to its high status—in some quarters, almost as the definition of Lean: operations people can readily learn to recognize and measure the wastes, and devise ways to reduce them. And it works—it does make operations quicker and more flexible, with better quality and value.

But if Lean is to maintain good health, waste reduction cannot be the driver and must be seen as a useful enabler. Lean must be defined and promoted for its strategic purpose—delivering flexibly quick, high-quality service everywhere along the value chain to patients. Seen this way, Lean can implant itself as a permanent organizational strategy.

Jenna, my physical therapist, may have been like many in health care, viewing Lean as something of a pedestrian imposition, and that training time would be better spent on patient care. At a more recent visit to PT with a different therapist, I spotted Jenna across the room. She called over to me and said, “I changed my mind. Now I like Lean!” That’s great, I thought. She’s happily chasing down wastes. Now, if only the facility’s leadership can come to understand Lean’s customer-side purpose and build it in as a fixed element of strategic management.

Richard J. Schonberger, PhD, president of Schonberger & Associates in Seattle, is the author of more than 170 articles and papers, as well as several books.

I was receiving PT for a shoulder problem. Jenna, my physical therapist, asked if I injured it working. I said no, my work involves writing and lecturing on Lean management, quality, and things related. Has Lean made it to this health center? I asked. Nodding, she replied impishly, “You said a bad word.”

After a late start in health care, Lean has cut a wide swath in the sector. Health care took its Lean lessons from industry, which had imported just-in-time (JIT) production from Japan in the 1980s, then renamed it Lean manufacturing in the 1990s. Off-the-mark tendencies for Lean as applied in manufacturing have, unfortunately, been carried over into health care. Sensible corrective measures are needed to ensure that Lean in health care does not suffer pain and an early death. Actually, the metaphor is apt in that Lean’s most beneficial outcome is reduction of wait times, and when it comes to health care, long wait times surely can and do kill people.

Since Lean’s introduction in the West three decades ago, it has been redefined, amended, and appended to the point some its lesser features have trumped what is meaningful to patients. Manufacturing has the excuse that end customers are nowhere in sight. Health care, on the other hand, is customer-facing. Lean’s customer-centered primary effects should make it doubly suitable in the health-care sector.

Although Lean manufacturing generally is viewed as a success story, my own multiyear “Leanness studies” reveal dominant patterns of good results followed by backsliding. A likely reason: Most present Lean in operational terms, so manufacturing executives delegate it down the hierarchy to the operations contingent. The same is generally the case where Lean has been applied in health care.

Corrective action calls for making it clear that Lean’s main effects are not operational so much as competitive and strategic. That is, the primary role and outcomes are delivering ever-quicker, more flexible, higher-quality, higher-value response to customer needs, demands, orders, and usage. Rather than seeing Lean this way, industry generally has adopted the view that Lean mainly is about reduction of the “seven wastes.” Falling in line, health care, too, has adopted waste elimination as Lean’s mantra.

That won’t do.

Rather than being Lean’s essence, waste reduction is akin to spaghetti diagrams, the five whys, value-stream mapping, and non-value-add analysis. All are worthy ways of framing the Lean pursuit but are not among the methodologies that act on the processes to change them from fat to lean. Over the years, some have done a better job implementing Lean, spending less time on framing and more on training employees in organization by product family or customer family, quick setup, cross-training/job rotation, trouble lights, and more, then saying, “Go do it.”

In getting it done, Lean delivers quick response as the dominant customer-sensitive effect: Nearly every change that Lean elicits reduces waiting times and waiting lines, and the sum total of those reductions through the processes can speed up customer response by an order of magnitude.

In delivering quick response in any setting, Lean relies on flexibility and quality. Given the norm—that customer demands and needs are highly variable, both in type and quantity—quick response requires flexibility so as to ensure immediate readiness for the next customer or need. Lean provides flexibility through a cross-trained or on-call workforce, plus fast-change or standby equipment. As for quality, without it, response is slowed or stopped for rework. Or abandoned entirely, with the customer seeking service elsewhere. Or the patient dies waiting.

There are reasons why waste reduction has been elevated to its high status—in some quarters, almost as the definition of Lean: operations people can readily learn to recognize and measure the wastes, and devise ways to reduce them. And it works—it does make operations quicker and more flexible, with better quality and value.

But if Lean is to maintain good health, waste reduction cannot be the driver and must be seen as a useful enabler. Lean must be defined and promoted for its strategic purpose—delivering flexibly quick, high-quality service everywhere along the value chain to patients. Seen this way, Lean can implant itself as a permanent organizational strategy.

Jenna, my physical therapist, may have been like many in health care, viewing Lean as something of a pedestrian imposition, and that training time would be better spent on patient care. At a more recent visit to PT with a different therapist, I spotted Jenna across the room. She called over to me and said, “I changed my mind. Now I like Lean!” That’s great, I thought. She’s happily chasing down wastes. Now, if only the facility’s leadership can come to understand Lean’s customer-side purpose and build it in as a fixed element of strategic management.

Richard J. Schonberger, PhD, president of Schonberger & Associates in Seattle, is the author of more than 170 articles and papers, as well as several books.

I was receiving PT for a shoulder problem. Jenna, my physical therapist, asked if I injured it working. I said no, my work involves writing and lecturing on Lean management, quality, and things related. Has Lean made it to this health center? I asked. Nodding, she replied impishly, “You said a bad word.”

After a late start in health care, Lean has cut a wide swath in the sector. Health care took its Lean lessons from industry, which had imported just-in-time (JIT) production from Japan in the 1980s, then renamed it Lean manufacturing in the 1990s. Off-the-mark tendencies for Lean as applied in manufacturing have, unfortunately, been carried over into health care. Sensible corrective measures are needed to ensure that Lean in health care does not suffer pain and an early death. Actually, the metaphor is apt in that Lean’s most beneficial outcome is reduction of wait times, and when it comes to health care, long wait times surely can and do kill people.

Since Lean’s introduction in the West three decades ago, it has been redefined, amended, and appended to the point some its lesser features have trumped what is meaningful to patients. Manufacturing has the excuse that end customers are nowhere in sight. Health care, on the other hand, is customer-facing. Lean’s customer-centered primary effects should make it doubly suitable in the health-care sector.

Although Lean manufacturing generally is viewed as a success story, my own multiyear “Leanness studies” reveal dominant patterns of good results followed by backsliding. A likely reason: Most present Lean in operational terms, so manufacturing executives delegate it down the hierarchy to the operations contingent. The same is generally the case where Lean has been applied in health care.

Corrective action calls for making it clear that Lean’s main effects are not operational so much as competitive and strategic. That is, the primary role and outcomes are delivering ever-quicker, more flexible, higher-quality, higher-value response to customer needs, demands, orders, and usage. Rather than seeing Lean this way, industry generally has adopted the view that Lean mainly is about reduction of the “seven wastes.” Falling in line, health care, too, has adopted waste elimination as Lean’s mantra.

That won’t do.

Rather than being Lean’s essence, waste reduction is akin to spaghetti diagrams, the five whys, value-stream mapping, and non-value-add analysis. All are worthy ways of framing the Lean pursuit but are not among the methodologies that act on the processes to change them from fat to lean. Over the years, some have done a better job implementing Lean, spending less time on framing and more on training employees in organization by product family or customer family, quick setup, cross-training/job rotation, trouble lights, and more, then saying, “Go do it.”

In getting it done, Lean delivers quick response as the dominant customer-sensitive effect: Nearly every change that Lean elicits reduces waiting times and waiting lines, and the sum total of those reductions through the processes can speed up customer response by an order of magnitude.

In delivering quick response in any setting, Lean relies on flexibility and quality. Given the norm—that customer demands and needs are highly variable, both in type and quantity—quick response requires flexibility so as to ensure immediate readiness for the next customer or need. Lean provides flexibility through a cross-trained or on-call workforce, plus fast-change or standby equipment. As for quality, without it, response is slowed or stopped for rework. Or abandoned entirely, with the customer seeking service elsewhere. Or the patient dies waiting.

There are reasons why waste reduction has been elevated to its high status—in some quarters, almost as the definition of Lean: operations people can readily learn to recognize and measure the wastes, and devise ways to reduce them. And it works—it does make operations quicker and more flexible, with better quality and value.

But if Lean is to maintain good health, waste reduction cannot be the driver and must be seen as a useful enabler. Lean must be defined and promoted for its strategic purpose—delivering flexibly quick, high-quality service everywhere along the value chain to patients. Seen this way, Lean can implant itself as a permanent organizational strategy.

Jenna, my physical therapist, may have been like many in health care, viewing Lean as something of a pedestrian imposition, and that training time would be better spent on patient care. At a more recent visit to PT with a different therapist, I spotted Jenna across the room. She called over to me and said, “I changed my mind. Now I like Lean!” That’s great, I thought. She’s happily chasing down wastes. Now, if only the facility’s leadership can come to understand Lean’s customer-side purpose and build it in as a fixed element of strategic management.

Richard J. Schonberger, PhD, president of Schonberger & Associates in Seattle, is the author of more than 170 articles and papers, as well as several books.

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers in dementia and hypertension

Dementia affects 34 million people globally, with the most common cause of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), affecting 5.5 million Americans.1,2 The connection between cerebrovascular disorders and AD means that antihypertensive agents may play a role in dementia prophylaxis and management.1,2

Hypertension increases the risk of intellectual dysfunction by increasing susceptibility to heart disease, ischemic brain injury, and cerebrovascular pathology.1 In addition to senile plaques, ischemic brain lesions are observed in autopsies of AD patients,1 and brain infarctions are more common among AD patients than among controls.2 Brain pathology suggestive of AD was found in 30% to 50% of postmortem examinations of patients with vascular dementia.1

It is useful to note that dihydropyridines, a subgroup of calcium channel blockers, may inhibit amyloidogenesis.3

Hypertension and cognition

Hypertension-induced hyperdense lesions in cerebral white matter reflect pathology in small vessels, inflammatory change, and disruption of the blood-brain barrier, which may precede cognitive decline.1 Even subclinical ischemic changes may increase the probability of developing dementia.2 Hypertension also reduces cerebral perfusion, especially in the hippocampus, which may promote degeneration of memory function.1 Prolonged cerebral hypoxia increases amyloid precursor protein production and β-secretase activity.1,2 Patients who died of brain ischemia show prominent β-amyloid protein and apolipoprotein E in histopathologic analysis of the hippocampus.1 Compression of vessels by â-amyloid protein further augments this degenerative process.1

Inhibition of amyloidogenesis

Long-term administration of antihypertensive medications in patients age <75 decreases the probability of dementia by 8% each year.1 Calcium channel blockers protect neurons by lowering blood pressure and reversing cellular-level calcium channel dysfunction that occurs with age, cerebral infarction, and AD.

Select dihydropyridines may inhibit amyloidogenesis in apolipoprotein E carriers:

• amlodipine and nilvadipine reduce β-secretase activity and amyloid precursor protein-β production3

• nilvadipine and nitrendipine limit β-amyloid protein synthesis in the brain and promote their clearance through the blood-brain barrier3

• nilvadipine-treated apolipoprotein E carriers experience cognitive stabilization compared with cognitive decreases seen in non-treated subjects.

Dihydropyridines can produce therapeutic effects for both AD and cerebrovascular dementia patients, indicating the potential that certain agents in this class have for treating both conditions.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Valenzuela M, Esler M, Ritchie K, et al. Antihypertensives for combating dementia? A perspective on candidate molecular mechanisms and population-based prevention. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e107.

2. Pimentel-Coelho PM, Rivest S. The early contribution of cerebrovascular factors to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(12):1917-1937.

3. Paris D, Bachmeier C, Patel N, et al. Selective antihypertensive dihydropyridines lower Aβ accumulation by targeting both the production and the clearance of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Med. 2011;17(3-4):149-162.

Dementia affects 34 million people globally, with the most common cause of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), affecting 5.5 million Americans.1,2 The connection between cerebrovascular disorders and AD means that antihypertensive agents may play a role in dementia prophylaxis and management.1,2

Hypertension increases the risk of intellectual dysfunction by increasing susceptibility to heart disease, ischemic brain injury, and cerebrovascular pathology.1 In addition to senile plaques, ischemic brain lesions are observed in autopsies of AD patients,1 and brain infarctions are more common among AD patients than among controls.2 Brain pathology suggestive of AD was found in 30% to 50% of postmortem examinations of patients with vascular dementia.1

It is useful to note that dihydropyridines, a subgroup of calcium channel blockers, may inhibit amyloidogenesis.3

Hypertension and cognition

Hypertension-induced hyperdense lesions in cerebral white matter reflect pathology in small vessels, inflammatory change, and disruption of the blood-brain barrier, which may precede cognitive decline.1 Even subclinical ischemic changes may increase the probability of developing dementia.2 Hypertension also reduces cerebral perfusion, especially in the hippocampus, which may promote degeneration of memory function.1 Prolonged cerebral hypoxia increases amyloid precursor protein production and β-secretase activity.1,2 Patients who died of brain ischemia show prominent β-amyloid protein and apolipoprotein E in histopathologic analysis of the hippocampus.1 Compression of vessels by â-amyloid protein further augments this degenerative process.1

Inhibition of amyloidogenesis

Long-term administration of antihypertensive medications in patients age <75 decreases the probability of dementia by 8% each year.1 Calcium channel blockers protect neurons by lowering blood pressure and reversing cellular-level calcium channel dysfunction that occurs with age, cerebral infarction, and AD.

Select dihydropyridines may inhibit amyloidogenesis in apolipoprotein E carriers:

• amlodipine and nilvadipine reduce β-secretase activity and amyloid precursor protein-β production3

• nilvadipine and nitrendipine limit β-amyloid protein synthesis in the brain and promote their clearance through the blood-brain barrier3

• nilvadipine-treated apolipoprotein E carriers experience cognitive stabilization compared with cognitive decreases seen in non-treated subjects.

Dihydropyridines can produce therapeutic effects for both AD and cerebrovascular dementia patients, indicating the potential that certain agents in this class have for treating both conditions.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dementia affects 34 million people globally, with the most common cause of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), affecting 5.5 million Americans.1,2 The connection between cerebrovascular disorders and AD means that antihypertensive agents may play a role in dementia prophylaxis and management.1,2

Hypertension increases the risk of intellectual dysfunction by increasing susceptibility to heart disease, ischemic brain injury, and cerebrovascular pathology.1 In addition to senile plaques, ischemic brain lesions are observed in autopsies of AD patients,1 and brain infarctions are more common among AD patients than among controls.2 Brain pathology suggestive of AD was found in 30% to 50% of postmortem examinations of patients with vascular dementia.1

It is useful to note that dihydropyridines, a subgroup of calcium channel blockers, may inhibit amyloidogenesis.3

Hypertension and cognition

Hypertension-induced hyperdense lesions in cerebral white matter reflect pathology in small vessels, inflammatory change, and disruption of the blood-brain barrier, which may precede cognitive decline.1 Even subclinical ischemic changes may increase the probability of developing dementia.2 Hypertension also reduces cerebral perfusion, especially in the hippocampus, which may promote degeneration of memory function.1 Prolonged cerebral hypoxia increases amyloid precursor protein production and β-secretase activity.1,2 Patients who died of brain ischemia show prominent β-amyloid protein and apolipoprotein E in histopathologic analysis of the hippocampus.1 Compression of vessels by â-amyloid protein further augments this degenerative process.1

Inhibition of amyloidogenesis

Long-term administration of antihypertensive medications in patients age <75 decreases the probability of dementia by 8% each year.1 Calcium channel blockers protect neurons by lowering blood pressure and reversing cellular-level calcium channel dysfunction that occurs with age, cerebral infarction, and AD.

Select dihydropyridines may inhibit amyloidogenesis in apolipoprotein E carriers:

• amlodipine and nilvadipine reduce β-secretase activity and amyloid precursor protein-β production3

• nilvadipine and nitrendipine limit β-amyloid protein synthesis in the brain and promote their clearance through the blood-brain barrier3

• nilvadipine-treated apolipoprotein E carriers experience cognitive stabilization compared with cognitive decreases seen in non-treated subjects.

Dihydropyridines can produce therapeutic effects for both AD and cerebrovascular dementia patients, indicating the potential that certain agents in this class have for treating both conditions.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Valenzuela M, Esler M, Ritchie K, et al. Antihypertensives for combating dementia? A perspective on candidate molecular mechanisms and population-based prevention. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e107.

2. Pimentel-Coelho PM, Rivest S. The early contribution of cerebrovascular factors to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(12):1917-1937.

3. Paris D, Bachmeier C, Patel N, et al. Selective antihypertensive dihydropyridines lower Aβ accumulation by targeting both the production and the clearance of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Med. 2011;17(3-4):149-162.

1. Valenzuela M, Esler M, Ritchie K, et al. Antihypertensives for combating dementia? A perspective on candidate molecular mechanisms and population-based prevention. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e107.

2. Pimentel-Coelho PM, Rivest S. The early contribution of cerebrovascular factors to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(12):1917-1937.

3. Paris D, Bachmeier C, Patel N, et al. Selective antihypertensive dihydropyridines lower Aβ accumulation by targeting both the production and the clearance of Aβ across the blood-brain barrier. Mol Med. 2011;17(3-4):149-162.

Young Man Thinks He is Having a Heart Attack

ANSWER

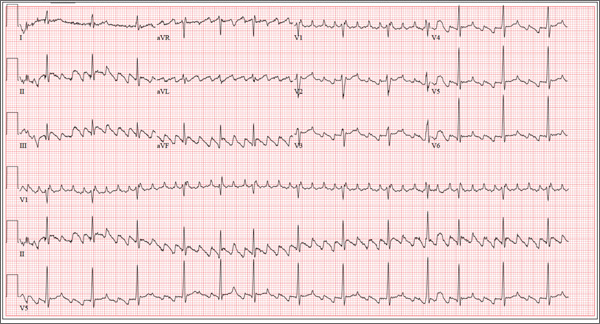

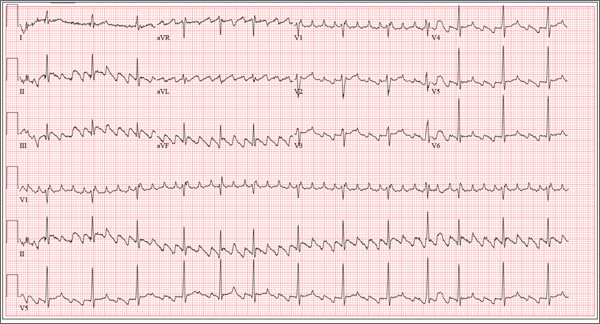

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG is atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block. Atrial flutter is a macro re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmia arising in the right atrium and usually (but not always!) identified by saw-tooth–appearing flutter waves.

The atrial rate in atrial flutter typically ranges from 200 to 350 beats/min. The QRS appearance will be narrow and similar to that of sinus rhythm, because conduction occurs normally down the atrioventricular node unless there is aberrant conduction.

The ventricular rate is dependent on the ability of the node to control rapid conduction. In this case, there appear to be three flutter waves for each QRS complex (3:1 flutter). If the ventricular rate is 80 beats/min, the rate in the atrium is approximately 240 beats/min. A regular ventricular rate of 150 beats/min should make you suspicious for atrial flutter (2:1 flutter).

The variable atrioventricular block on this ECG is evidenced by the presence of two, rather than three, flutter waves per QRS complex (seen after the fourth, fifth, and 10th QRS complexes on the rhythm strip). This case illustrates that flutter may be present with a ventricular rate of less than 100 beats/min.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG is atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block. Atrial flutter is a macro re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmia arising in the right atrium and usually (but not always!) identified by saw-tooth–appearing flutter waves.

The atrial rate in atrial flutter typically ranges from 200 to 350 beats/min. The QRS appearance will be narrow and similar to that of sinus rhythm, because conduction occurs normally down the atrioventricular node unless there is aberrant conduction.

The ventricular rate is dependent on the ability of the node to control rapid conduction. In this case, there appear to be three flutter waves for each QRS complex (3:1 flutter). If the ventricular rate is 80 beats/min, the rate in the atrium is approximately 240 beats/min. A regular ventricular rate of 150 beats/min should make you suspicious for atrial flutter (2:1 flutter).

The variable atrioventricular block on this ECG is evidenced by the presence of two, rather than three, flutter waves per QRS complex (seen after the fourth, fifth, and 10th QRS complexes on the rhythm strip). This case illustrates that flutter may be present with a ventricular rate of less than 100 beats/min.

ANSWER

The correct interpretation of this patient’s ECG is atrial flutter with variable atrioventricular block. Atrial flutter is a macro re-entrant supraventricular arrhythmia arising in the right atrium and usually (but not always!) identified by saw-tooth–appearing flutter waves.

The atrial rate in atrial flutter typically ranges from 200 to 350 beats/min. The QRS appearance will be narrow and similar to that of sinus rhythm, because conduction occurs normally down the atrioventricular node unless there is aberrant conduction.

The ventricular rate is dependent on the ability of the node to control rapid conduction. In this case, there appear to be three flutter waves for each QRS complex (3:1 flutter). If the ventricular rate is 80 beats/min, the rate in the atrium is approximately 240 beats/min. A regular ventricular rate of 150 beats/min should make you suspicious for atrial flutter (2:1 flutter).

The variable atrioventricular block on this ECG is evidenced by the presence of two, rather than three, flutter waves per QRS complex (seen after the fourth, fifth, and 10th QRS complexes on the rhythm strip). This case illustrates that flutter may be present with a ventricular rate of less than 100 beats/min.

The 24-year-old male graduate student whom you saw one month ago for palpitations (see July 2013 ECG Challenge) returns without an appointment, stating that his heart is “flip-flopping” just as it has in the past. The problem started abruptly about 45 minutes ago, and he is afraid he might be having a heart attack. A quick check of his pulse reveals a rate of 80 beats/min. At his previous visit, an ECG showed sinus rhythm with sinus arrhythmia and a blocked premature atrial contraction (PAC). A rhythm strip documented that his palpitations coincided with blocked PACs. You recall that he reported having two episodes of tachycardia in the past, while “pulling all-nighters” for finals as an undergraduate. Today, he denies shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, and symptoms of near-syncope or syncope, but says his heart is “flopping around” in his chest and he can feel his heart beat in his throat. He has no prior cardiac or pulmonary history and has not recently been ill. Medical history, medication list, allergies, family history, and review of systems are unchanged since his last visit: Medical history is remarkable only for fractures of the right ankle and the left clavicle. He takes no medications and has no drug allergies. Family history is significant for stroke (paternal grandfather), diabetes (maternal grandmother), and hypertension (father). The patient consumes alcohol socially, primarily on weekends, and does not binge drink. He smokes marijuana during snowboard season, but denies use at other times of the year. A 12-point review of systems is positive only for athlete’s foot and psoriasis on both upper extremities. The physical exam reveals an anxious but otherwise healthy, athletic-appearing male. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 140/88 mm Hg; pulse, 80 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min-1; and O2 saturation, 99% on room air. His height is 70” and his weight, 161 lb. His lungs are clear, there is no jugular venous distention, and cardiac auscultation reveals no murmurs, gallops, or rubs. The abdominal exam is normal without organomegaly, and peripheral pulses are regular and strong bilaterally. His neurologic exam yields normal results. As you examine the ECG, you note the following: a ventricular rate of 80 beats/min; PR interval, unmeasurable; QRS duration, 92 ms; QT/QTc interval, 388/444 ms; P axis, 265°; R axis, 72°; and T axis, 66°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Not Just Another Groin Rash

ANSWER

The correct answer is fungal infection (choice “a”). If this condition had been fungal, it would have responded to one or more of the medications used to treat it. In this case, treatment failure demanded consideration of alternate diagnostic possibilities.

Lichen simplex chronicus (choice “b”), also known as neurodermatitis, was a good possibility, since it is the consequence of chronic rubbing or scratching in response to the itching caused by, for example, eczema.

Psoriasis (choice “c”) usually has adherent white scale on its surface, unless it’s in an intertriginous (skin on skin) area where scale gets rubbed off by friction.

The patient’s actual diagnosis, however, turned out to be Paget’s disease (choice “d”). See the Discussion for relevant details.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy showed changes consistent with a type of skin cancer called extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD), an intradermal adenocarcinoma that tends to develop in areas where apocrine glands are found (eg, the anogenital and axillary areas).

The majority of EMPD cases represent adenocarcinoma in situ with extension from adnexal structures. Intraepidermal metastasis from noncutaneous adenocarcinomas (via local or lymphatic routes) accounts for a significant minority of cases (< 25%). Urogenital and colorectal carcinomas are the most common.

EMPD is more common in women and is rare before age 40. In addition to the usual intertriginous areas, other sites in which it may be found include eyelids and ears. The lesions typically itch but rarely hurt; they do, however, inevitably grow larger and more extensive.

The histologic changes of EMPD are identical to those seen in mammary Paget’s disease, though the latter virtually always involves the areola and nipple. It also signals the presence of an underlying intraductal breast cancer.

The main teaching point to be gleaned from this case is the concept of “cancer presenting as a rash,” of which there are several examples: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma, metastatic breast cancer, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen’s disease).

EMPD is especially prone to being overlooked, not only because groin rashes are so common but also because most skin cancers are “lesional” (ie, they take the form of a papule or nodule). Any rash that proves to be unresponsive to ordinary treatment should be either referred to dermatology or biopsied.

TREATMENT

This patient was prescribed imiquimod 5% cream, to be applied three times a week, which has a good chance of clearing the condition (but only after three to four months of application). If this fails, the patient will be referred for Mohs surgery.

Even so, recurrences are common. About 25% of EMPD patients with underlying malignancies eventually die of their disease. For these reasons, the patient was referred back to his primary care provider for workup for a possible underlying malignancy.

ANSWER

The correct answer is fungal infection (choice “a”). If this condition had been fungal, it would have responded to one or more of the medications used to treat it. In this case, treatment failure demanded consideration of alternate diagnostic possibilities.

Lichen simplex chronicus (choice “b”), also known as neurodermatitis, was a good possibility, since it is the consequence of chronic rubbing or scratching in response to the itching caused by, for example, eczema.

Psoriasis (choice “c”) usually has adherent white scale on its surface, unless it’s in an intertriginous (skin on skin) area where scale gets rubbed off by friction.

The patient’s actual diagnosis, however, turned out to be Paget’s disease (choice “d”). See the Discussion for relevant details.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy showed changes consistent with a type of skin cancer called extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD), an intradermal adenocarcinoma that tends to develop in areas where apocrine glands are found (eg, the anogenital and axillary areas).

The majority of EMPD cases represent adenocarcinoma in situ with extension from adnexal structures. Intraepidermal metastasis from noncutaneous adenocarcinomas (via local or lymphatic routes) accounts for a significant minority of cases (< 25%). Urogenital and colorectal carcinomas are the most common.

EMPD is more common in women and is rare before age 40. In addition to the usual intertriginous areas, other sites in which it may be found include eyelids and ears. The lesions typically itch but rarely hurt; they do, however, inevitably grow larger and more extensive.

The histologic changes of EMPD are identical to those seen in mammary Paget’s disease, though the latter virtually always involves the areola and nipple. It also signals the presence of an underlying intraductal breast cancer.

The main teaching point to be gleaned from this case is the concept of “cancer presenting as a rash,” of which there are several examples: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma, metastatic breast cancer, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen’s disease).

EMPD is especially prone to being overlooked, not only because groin rashes are so common but also because most skin cancers are “lesional” (ie, they take the form of a papule or nodule). Any rash that proves to be unresponsive to ordinary treatment should be either referred to dermatology or biopsied.

TREATMENT

This patient was prescribed imiquimod 5% cream, to be applied three times a week, which has a good chance of clearing the condition (but only after three to four months of application). If this fails, the patient will be referred for Mohs surgery.

Even so, recurrences are common. About 25% of EMPD patients with underlying malignancies eventually die of their disease. For these reasons, the patient was referred back to his primary care provider for workup for a possible underlying malignancy.

ANSWER

The correct answer is fungal infection (choice “a”). If this condition had been fungal, it would have responded to one or more of the medications used to treat it. In this case, treatment failure demanded consideration of alternate diagnostic possibilities.

Lichen simplex chronicus (choice “b”), also known as neurodermatitis, was a good possibility, since it is the consequence of chronic rubbing or scratching in response to the itching caused by, for example, eczema.

Psoriasis (choice “c”) usually has adherent white scale on its surface, unless it’s in an intertriginous (skin on skin) area where scale gets rubbed off by friction.

The patient’s actual diagnosis, however, turned out to be Paget’s disease (choice “d”). See the Discussion for relevant details.

DISCUSSION

Biopsy showed changes consistent with a type of skin cancer called extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD), an intradermal adenocarcinoma that tends to develop in areas where apocrine glands are found (eg, the anogenital and axillary areas).

The majority of EMPD cases represent adenocarcinoma in situ with extension from adnexal structures. Intraepidermal metastasis from noncutaneous adenocarcinomas (via local or lymphatic routes) accounts for a significant minority of cases (< 25%). Urogenital and colorectal carcinomas are the most common.

EMPD is more common in women and is rare before age 40. In addition to the usual intertriginous areas, other sites in which it may be found include eyelids and ears. The lesions typically itch but rarely hurt; they do, however, inevitably grow larger and more extensive.

The histologic changes of EMPD are identical to those seen in mammary Paget’s disease, though the latter virtually always involves the areola and nipple. It also signals the presence of an underlying intraductal breast cancer.

The main teaching point to be gleaned from this case is the concept of “cancer presenting as a rash,” of which there are several examples: cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma, metastatic breast cancer, superficial basal cell carcinoma, and intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen’s disease).

EMPD is especially prone to being overlooked, not only because groin rashes are so common but also because most skin cancers are “lesional” (ie, they take the form of a papule or nodule). Any rash that proves to be unresponsive to ordinary treatment should be either referred to dermatology or biopsied.

TREATMENT

This patient was prescribed imiquimod 5% cream, to be applied three times a week, which has a good chance of clearing the condition (but only after three to four months of application). If this fails, the patient will be referred for Mohs surgery.

Even so, recurrences are common. About 25% of EMPD patients with underlying malignancies eventually die of their disease. For these reasons, the patient was referred back to his primary care provider for workup for a possible underlying malignancy.

A 60-year-old man is referred to dermatology for evaluation of a somewhat itchy, unilateral groin rash. For several years, it has waxed and waned, never completely resolving. Recently, the rash has grown in size, and the itching has intensified, causing the patient to lose sleep. The patient has tried several OTC and prescription topical medications for this problem: creams containing clotrimazole, tolnaftate, 1% hydrocortisone, and betamethasone/clotrimazole, as well as triple-antibiotic ointment and several different moisturizing creams and lotions. He also tried a two-week course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d). Additional questioning reveals a history of atopy, eczema, and asthma as a child. There is a strong family history of similar problems. This strikingly red, blistery-appearing rash is palm-sized and confined to the right groin. It has a fairly well–defined, scaly border that is KOH-negative on microscopic examination. Within the borders of this lesion are several focal, shiny, somewhat atrophic areas in which no epidermal adnexae (pores, follicles, hair, skin lines) can be seen.

Pregnant and catatonic

CASE: Mute and unresponsive

Mrs. K, a 42-year-old Haitian who is 31 weeks pregnant, presents with a 4-week history of progressive mutism and psychomotor retardation. At inpatient admission, she is awake and alert but does not speak and resists the treatment team’s attempts to engage her. Mrs. K’s eyes are open, but she has a vacant stare and avoids eye contact. Her affect is flat and nonreactive and she appears internally preoccupied. Mrs. K exhibits motoric immobility, displays a rigid posture, and resists attempts to get her to move. Features of catatonic excitement, echo phenomena, posturing, stereotypies, and mannerisms are absent during the initial evaluation.

Mrs. K’s husband reports that they had been on vacation for 6 days before he brought her for psychiatric evaluation. He denies any recent evidence of psychosis or mood disturbance, stating that his wife was excited when she learned of the pregnancy, and attended all prenatal appointments. He reports that when this episode began, Mrs. K stopped talking to her 3-year-old daughter, did not respond to her name, and did not pay attention to those around her.

According to her husband, a similar episode occurred 2 years earlier, during which Mrs. K was selectively mute for approximately 1 month. She did not eat for 5 days and neglected the care of her daughter. There were 2 additional brief periods of prominent psychomotor retardation for which she was hospitalized in Haiti. According to the patient’s aunt, Mrs. K complained that her husband had cast a “voodoo spell” on her because he wanted sole custody of their daughter. Her husband recounted an episode, when they lived in Haiti, during which his wife became paranoid, left the house, and wandered the streets for 2 days.

The medical history is significant for a cervical polyp that was removed 2 years ago. Mrs. K has no history of substance abuse. She was born and raised in Haiti where she studied medicine. Her family reports that Mrs. K’s husband is “controlling,” which causes her distress.

a) major depressive disorder, severe with psychosis, with catatonia

b) schizophrenia, with catatonia

c) conversion disorder, with catatonia

d) bipolar I disorder, with psychosis and catatonia

The authors' observations

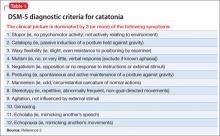

Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric syndrome that can occur in schizophrenia, mood disorders, mental retardation, neurologic disease, metabolic conditions, and drug intoxication.1 Catatonia can present in several ways, from catatonic stupor to extreme purposeless agitation; more than 60 catatonic signs and symptoms have been described.1 According to DSM-52 catatonia is characterized by 3 or more of the following symptoms:

• stupor

• catalepsy

• waxy flexibility

• mutism

• negativism

• posturing

• mannerism

• stereotypy

• agitation, not influenced by external stimuli

• grimacing

• echolalia

• echopraxia.

Mrs. K exhibited stupor, mutism, posturing, and grimacing (Table 1).2 We thought that her catatonic features were secondary to schizophrenia because she had paranoid delusions and displayed disorganized behavior while in Haiti. There was no evidence of past or current mood disorder, metabolic condition, neurologic illness, or substance abuse.

Catatonia and pregnancy

There is little available information to guide clinicians who are treating a pregnant woman who has a catatonic syndrome. Espinola-Nadurille and co-workers described a 22-year-old pregnant (21 weeks) woman from rural Mexico who was hospitalized with agitation, disorganized speech, restlessness, and hallucinations after several weeks of alternating agitation and withdrawal with mutism and refusal to eat or drink.3 This patient developed malignant catatonia with creatine phosphokinase elevation and leukocytosis and eventually responded to treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). She was given a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder. Treating her catatonic symptoms did not result in any adverse effects on the pregnancy or the fetus.

Exacerbation of schizophrenia during pregnancy can lead to neglect of pregnancy and prenatal care,4 imminent harm to the fetus because of malnutrition and dehydration, and risk of preterm delivery and low weight at birth. Prolonged catatonia can cause medical complications such as decubitus ulcers, incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infections, aspiration pneumonia, increased risk of deep venous thrombosis, malnutrition, and ocular complications because of prolonged staring and reduced blinking (Table 25-10). For these reasons, it is important to treat this condition early and aggressively to improve pregnancy outcome and infant well-being.

of Mrs. K’s symptoms?

a) Positive and Negative Symptom Scale

b) The Northoff Catatonia Rating Scale

c) The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS)

d) The Rogers Catatonia Scale

EVALUATION: Flat affect

The mental status examination on admission describes a tall, black, Haitian woman with unkempt hair and fair hygiene. Mrs. K has a prominent abdomen, consistent with a 31-week pregnancy. She exhibits a blank stare without direct eye contact; she is mute, and exhibits flat affect. We cannot evaluate her thought processes and content because Mrs. K is mute, although she does appear internally preoccupied.

Physical examination on admission is unremarkable; vital signs are stable and within normal limits. Laboratory work-up reveals a urinary tract infection, which is treated with ceftriaxone. Mrs. K also has macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 11.7 g/dL; hematocrit, 34.7%; mean corpuscular volume, 99.2 μm3). Albumin is low at 2.6 g/dL. Urine drug toxicology screen is negative. Fingerstick glucose reading is 139 mg/dL. Mrs. K is given a presumptive diagnosis of schizophrenia with catatonia.

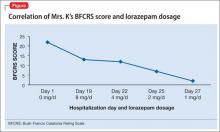

Mrs. K’s BFCRS11 score is 22 at admission. She is mute, holds postures for longer than a minute, and is resistant to repositioning. She also has extreme hypoactivity and does not interact with others. She has a fixed, blank stare, and exhibits mild grimacing.

The authors' observations

BFCRS defines each catatonic sign, rates its severity, and provides a standardized schema for clinical examination.11 The BFCRS is preferred for routine use because of its validity, reliability, and ease of administration.12 The treatment team rated Mrs. K at admission, during the course of treatment, and at discharge, showing a substantial improvement at the end of the hospitalization (Figure).

a) ECT

b) lorazepam

c) haloperidol

d) olanzapine

The authors' observations

Benzodiazepines (particularly lorazepam) and ECT are considered the treatment of choice for catatonic symptoms.11 More than 72% of patients with catatonic symptoms remit after a trial of a benzodiazepine.1 ECT is considered when patients do not respond to a benzodiazepine after 48 to 72 hours.3 Several cases of complete resolution of catatonic symptoms have been linked to ECT (Table 3).13-18

A recent retrospective review revealed that patients who do not respond to lorazepam are more likely to come from a rural setting, have a longer duration of illness, exhibit mutism, and exhibit third-person auditory hallucinations and made phenomena (the feeling that some aspect of the individual is under the external control of others).19 Case reports of treatment of catatonic patients with ECT vs lorazepam are listed in Table 3.13-18

In pregnancy, ECT can be considered early in the course of illness. A review of the literature on ECT during pregnancy reported at least partial remission in 78% of studies reporting efficacy data.20 Among these 339 patients, there were 25 fetal or neonatal complications—only 11 of these were related to ECT—and 20 maternal complications, of which 18 were related to ECT. The authors of this review concluded that 1) ECT is an effective treatment for severe mental illness during pregnancy and 2) the risks to fetus and mother are low.

A 2007 study identified 1,979 infants whose mothers reported use of benzodiazepines or hypnotic benzodiazepine-receptor agonists during early pregnancy.21 An additional 401 infants born to mothers who were prescribed these medications during late pregnancy also were included in this study. Women who took these medications were at an increased risk for preterm birth and low birth weight. The rate of congenital malformations in this study was moderately increased among infants exposed in early pregnancy (adjusted odds ratio = 1.24 [95% confidence interval, 1.00 to 1.55]).

Because catatonic symptoms can appear during the course of schizophrenia, several antipsychotics have been used to treat this condition. The efficacy and safety of antipsychotics for treating catatonia remains largely unknown, however.1

OUTCOME: Recovery, baby girl

We begin oral haloperidol, 10 mg/d, for Mrs. K, which we then increase to 20 mg/d. Because she shows little response to haloperidol, we suggest a trial of ECT, but her husband refuses to consent. She is started on IM lorazepam, 6 mg/d.

Mrs. K gradually improves and increases her intake of food and liquids. After 10 days of lorazepam treatment, her BFCRS score decreases to 13. Mrs. K begins to speak and her gaze is less fixed. Negativistic behaviors are nearly absent.

Because we are concerned about Mrs. K’s pregnancy, lab tests are repeated. A complete metabolic panel shows an elevated glucose level (122 mg/dL); urinalysis reveals glycosuria (glucose, 1,000 mg/dL), proteinuria (protein, 10 mg/dL), and ketonuria, (ketones, 20 mg/dL). She is transferred to the obstetrics service for evaluation of gestational diabetes.

Psychotropics are continued while Mrs. K is on the obstetrics service; she returns to the inpatient psychiatric unit on an insulin regimen. IM lorazepam is increased to 8 mg/d, and haloperidol is decreased from 20 mg/d, to 10 mg/d, to prevent worsening of catatonia, which can occur when catatonic patients receive a psychotropic.11 Three days later, Mrs. K’s BFCRS score is 12 and she shows only mild rigidity. Mrs. K briefly interacts with staff, particularly when she wants something.

Lorazepam is decreased to 1 mg/d in anticipation of cesarean delivery. Mrs. K becomes more adherent with her medications; often, she takes the oral dose of haloperidol, rather than the IM formulation. On mental status examination she exhibits poor eye contact, rather than a fixed gaze, and her BFCRS score decreases to 7 by day 25.

By the end of lorazepam treatment, Mrs. K has fully recovered from her catatonic state. She interacts with staff, engages with the treatment team, and is excited to go home. At discharge, she is given a diagnosis of schizophrenia with catatonia, and is taking haloperidol, 5 mg, twice a day. She gives birth to a healthy girl.

The authors' observations

Mrs. K was treated initially with haloperidol for several reasons. Haloperidol is relatively safe during pregnancy (FDA pregnancy category C) as shown by a recent multicenter, prospective, cohort study in which babies exposed in utero to haloperidol showed a congenital malformation (limb defect) rate within the expected baseline risk for the general population.22 Lorazepam is FDA category D for use in pregnancy and can cause preterm delivery,23 floppy infant syndrome, and withdrawal syndromes.24 We did not use a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) because it could have made Mrs. K’s hyperglycemia worse. SGAs can induce gestational diabetes and increase the incidence of large-for-gestational-age newborns, compared with first-generation antipsychotics.24 Last, Mrs. K’s family rejected ECT.

Because of Mrs. K’s poor response to haloperidol, the treatment team decided to start IM lorazepam, which eventually was increased to 8 mg/d. The haloperidol dose was reduced by half to avoid worsening of catatonia and reduce the risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome.1,25 When clinical response was achieved, lorazepam was tapered and Mrs. K was discharged with only haloperidol.

In the absence of well-designed prospective follow-up studies, information on the potential impact of prenatal exposure to antipsychotics and benzodiazepines on a child’s cognitive development is limited.26 This case adds to the scant literature on the treatment of catatonia during pregnancy and illustrates how the BFCRS can be utilized during serial patient evaluations to monitor clinical improvement.

Bottom Line

Psychosis and catatonia during pregnancy are associated with complications to mother and child. The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale can be used to identify and track catatonic symptoms. Lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy have been used safely and with good outcomes in mentally ill pregnant women when used appropriately.

Related Resources

- Fink M. Catatonia: a syndrome appears, disappears, and is rediscovered. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(7):437-445.

- Seethalakshmi R, Dhavale S, Suggu K, et al. Catatonic syndrome: importance of detection and treatment with lorazepam. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20(1):5-8.

- Salam S, Kilzieh N. Lorazepam treatment of psychogenic catatonia: an update. J Clin Psychiatry, 1988;49(suppl):16-21.

Drug Brand Names

Ceftriaxone • Rocephin Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Haloperidol • Haldol Short-acting Insulin • Novolin, Humulin

Lorazepam • Ativan

Disclosures

Dr. Runyan receives grant support from Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. Drs. Durant, Prudent, and Sotelo report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Weder N, Muralee S, Penland H, et al. Catatonia: a review. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20(2):97-107.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Espinola-Nadurille M, Ramirez-Bermudez J, Fricchione GL. Pregnancy and malignant catatonia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(1):69-71.

4. Solari H, Dickson KE, Miller L. Understanding and treating women with schizophrenia during pregnancy and postpartum. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;16(1):e23-e32.

5. Gross AF, Smith FA, Stern TA. Dread complications of catatonia: a case discussion and review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;10(12):

153-155.

6. Larsen HH, Ritchie JC, McNutt MD, et al. Pulmonary embolism in a patient with catatonia: an old disease, changing times. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(4):387-391.

7. Lachner C, Sandson NB. Medical complications of catatonia: a case of catatonia-induced deep venous thrombosis. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(6):512-4.

8. Morioka H, Nagatomo I, Yamada K, et al. Deep venous thrombosis of the leg due to psychiatric stupor. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 1997;51(5):323-326.

9. Nomoto H, Hatta K, Usui C, et al. Vitamin K deficiency due to prolongation of antibiotic treatment and decrease in food intake in a catatonia patient. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(5):

486-487.

10. Srivastava A, Gupta A, Murthy P, et al. Catatonia and multiple pressure ulcers: a rare complication in psychiatric setting. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(3):206-208.

11. Francis A. Catatonia: diagnosis, classification, and treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):180-185.

12. Sienaert P, Rooseleer J, De Fruyt J. Measuring catatonia: a systematic review of rating scales. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1):1-9.

13. Zisselman MH, Jaffe RL. ECT in the treatment of a patient with catatonia: consent and complications. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):127-132.

14. Rohland BM, Carroll BT, Jacoby RG. ECT in the treatment of the catatonic syndrome. J Affect Disord. 1993;29(4):255-261.

15. Raveendranathan D, Narayanaswamy JC, Reddi SV. Response rate of catatonia to electroconvulsive therapy and its clinical correlates. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(5):425-430.

16. Payee H, Chandrasekaran R, Raju GV. Catatonic syndrome: treatment response to lorazepam. Indian J Psychiatry. 1999; 41(1):49-53.

17. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides G, et al. Catatonia. II. Treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(2):137-143.

18. Huang TL. Lorazepam and diazepam rapidly relieve catatonic signs in patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(1):52-55.

19. Narayanaswamy JC, Tibrewal P, Zutshi A, et al. Clinical predictors of response to treatment in catatonia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:312-316.

20. Anderson EL, Reti IM. ECT in pregnancy: a review of the literature from 1941 to 2007. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:

235-242.

21. Wikner BN, Stiller CO, Bergman U, et al. Use of benzodiazepines and benzodiazepine receptor agonists during pregnancy: neonatal outcome and congenital malformations. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:

1203-1210.

22. Gentile S. Antipsychotic therapy during early and late pregnancy. A systematic review. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:

518-544.

23. Calderon-Margalit R, Qiu C, Ornoy A, et al. Risk of preterm delivery and other adverse perinatal outcomes in relation to maternal use of psychotropic medications during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:579e1-8.

24. Howland RH. Prescribing psychotropic medications during pregnancy and lactation: principles and guidelines. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2009;47(5):19-23.

25. White DA, Robins AH. Catatonia: harbinger of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1991; 158:419-421.

26. Gentile S. Neurodevelopmental effects of prenatal exposure to psychotropic medications. Depress Anxiety. 2010; 27(7):675-686.

CASE: Mute and unresponsive

Mrs. K, a 42-year-old Haitian who is 31 weeks pregnant, presents with a 4-week history of progressive mutism and psychomotor retardation. At inpatient admission, she is awake and alert but does not speak and resists the treatment team’s attempts to engage her. Mrs. K’s eyes are open, but she has a vacant stare and avoids eye contact. Her affect is flat and nonreactive and she appears internally preoccupied. Mrs. K exhibits motoric immobility, displays a rigid posture, and resists attempts to get her to move. Features of catatonic excitement, echo phenomena, posturing, stereotypies, and mannerisms are absent during the initial evaluation.

Mrs. K’s husband reports that they had been on vacation for 6 days before he brought her for psychiatric evaluation. He denies any recent evidence of psychosis or mood disturbance, stating that his wife was excited when she learned of the pregnancy, and attended all prenatal appointments. He reports that when this episode began, Mrs. K stopped talking to her 3-year-old daughter, did not respond to her name, and did not pay attention to those around her.

According to her husband, a similar episode occurred 2 years earlier, during which Mrs. K was selectively mute for approximately 1 month. She did not eat for 5 days and neglected the care of her daughter. There were 2 additional brief periods of prominent psychomotor retardation for which she was hospitalized in Haiti. According to the patient’s aunt, Mrs. K complained that her husband had cast a “voodoo spell” on her because he wanted sole custody of their daughter. Her husband recounted an episode, when they lived in Haiti, during which his wife became paranoid, left the house, and wandered the streets for 2 days.

The medical history is significant for a cervical polyp that was removed 2 years ago. Mrs. K has no history of substance abuse. She was born and raised in Haiti where she studied medicine. Her family reports that Mrs. K’s husband is “controlling,” which causes her distress.

a) major depressive disorder, severe with psychosis, with catatonia

b) schizophrenia, with catatonia

c) conversion disorder, with catatonia

d) bipolar I disorder, with psychosis and catatonia

The authors' observations

Catatonia is a neuropsychiatric syndrome that can occur in schizophrenia, mood disorders, mental retardation, neurologic disease, metabolic conditions, and drug intoxication.1 Catatonia can present in several ways, from catatonic stupor to extreme purposeless agitation; more than 60 catatonic signs and symptoms have been described.1 According to DSM-52 catatonia is characterized by 3 or more of the following symptoms:

• stupor

• catalepsy

• waxy flexibility

• mutism

• negativism

• posturing

• mannerism

• stereotypy

• agitation, not influenced by external stimuli

• grimacing

• echolalia

• echopraxia.

Mrs. K exhibited stupor, mutism, posturing, and grimacing (Table 1).2 We thought that her catatonic features were secondary to schizophrenia because she had paranoid delusions and displayed disorganized behavior while in Haiti. There was no evidence of past or current mood disorder, metabolic condition, neurologic illness, or substance abuse.

Catatonia and pregnancy

There is little available information to guide clinicians who are treating a pregnant woman who has a catatonic syndrome. Espinola-Nadurille and co-workers described a 22-year-old pregnant (21 weeks) woman from rural Mexico who was hospitalized with agitation, disorganized speech, restlessness, and hallucinations after several weeks of alternating agitation and withdrawal with mutism and refusal to eat or drink.3 This patient developed malignant catatonia with creatine phosphokinase elevation and leukocytosis and eventually responded to treatment with lorazepam and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). She was given a diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder. Treating her catatonic symptoms did not result in any adverse effects on the pregnancy or the fetus.

Exacerbation of schizophrenia during pregnancy can lead to neglect of pregnancy and prenatal care,4 imminent harm to the fetus because of malnutrition and dehydration, and risk of preterm delivery and low weight at birth. Prolonged catatonia can cause medical complications such as decubitus ulcers, incontinence, recurrent urinary tract infections, aspiration pneumonia, increased risk of deep venous thrombosis, malnutrition, and ocular complications because of prolonged staring and reduced blinking (Table 25-10). For these reasons, it is important to treat this condition early and aggressively to improve pregnancy outcome and infant well-being.

of Mrs. K’s symptoms?

a) Positive and Negative Symptom Scale

b) The Northoff Catatonia Rating Scale

c) The Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale (BFCRS)

d) The Rogers Catatonia Scale

EVALUATION: Flat affect

The mental status examination on admission describes a tall, black, Haitian woman with unkempt hair and fair hygiene. Mrs. K has a prominent abdomen, consistent with a 31-week pregnancy. She exhibits a blank stare without direct eye contact; she is mute, and exhibits flat affect. We cannot evaluate her thought processes and content because Mrs. K is mute, although she does appear internally preoccupied.

Physical examination on admission is unremarkable; vital signs are stable and within normal limits. Laboratory work-up reveals a urinary tract infection, which is treated with ceftriaxone. Mrs. K also has macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 11.7 g/dL; hematocrit, 34.7%; mean corpuscular volume, 99.2 μm3). Albumin is low at 2.6 g/dL. Urine drug toxicology screen is negative. Fingerstick glucose reading is 139 mg/dL. Mrs. K is given a presumptive diagnosis of schizophrenia with catatonia.

Mrs. K’s BFCRS11 score is 22 at admission. She is mute, holds postures for longer than a minute, and is resistant to repositioning. She also has extreme hypoactivity and does not interact with others. She has a fixed, blank stare, and exhibits mild grimacing.

The authors' observations