User login

Painful nail with longitudinal erythronychia

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

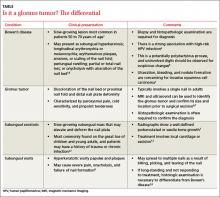

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

A 46-year-old Caucasian woman was referred to our dermatology clinic with a one year history of progressively increasing pain radiating from the proximal nail fold of her right middle finger. She denied any history of trauma and noted that the pain was worse when her finger was exposed to cold.

On examination, we noted that there was a red line that extended the length of the nail, beginning at the area of pain and ending distally, where the nail split (FIGURE).

FIGURE

Red line extends from area of pain to area of nail splitting

What is your diagnosis?

How would you treat this patient?

Diagnosis: Subungual glomus tumor

Glomus tumor is a rare vascular neoplasm derived from the cells of the glomus body, a specialized arteriovenous shunt involved in temperature regulation. Glomus bodies are most abundant in the extremities, and 75% of glomus tumors are found in the hand.1 The most common location is the subungual region, where glomus bodies are highly concentrated.

These lesions are typically benign, although a malignant variant has been reported in 1% of cases.1,2 Glomus tumors are most common in adults 30 to 50 years of age, with subungual tumors occurring more often in women.3 The majority of glomus tumors are solitary and less than 1 cm in size.2,4 Multiple tumors may be familial and tend to occur in children.2,4

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital practitioners made the correct diagnosis.Patients with subungual glomus tumors present with intense pain that they may describe as shooting or pulsating in nature.

The pain may be spontaneous or triggered by mild trauma or changes in temperature—especially warm to cold. The classic triad of symptoms includes pinpoint tenderness, paroxysmal pain, and cold hypersensitivity. 3,4 The glomus tumor may appear as a focal bluish to erythematous discoloration visible through the nail plate, and in some cases the tumor may form a palpable nodule. Nail deformities such as ridging and distal fissuring occur in approximately one-third of patients.4

Longitudinal erythronychia, as seen in our patient, results when the glomus tumor exerts pressure on the distal nail matrix. This force leads to a thinning of the nail plate and the formation of a groove on the ventral surface of the nail. Swelling of the underlying nail bed with engorgement of vessels produces the red streak that is seen through the thinned nail.5 And, because the affected portion of the nail is fragile, it tends to split distally.

Longitudinal erythronychia with nail dystrophy involving multiple nails is also seen in inflammatory diseases, such as lichen planus and Darier disease, due to multifocal loss of nail matrix function.5

Differential Dx includes subungual warts, Bowen’s disease

Clinical mimics of glomus tumors include neuromas, melanomas, Bowen’s disease, arthritis, gout, paronychia, causalgia, subungual exostosis, osteochondroma, and subungual warts. (The TABLE1,6-8 describes some of the more common mimics.)

In an analysis of 43 patients with glomus tumors, only 19% of referring practitioners and 49% of hospital-based practitioners correctly made the diagnosis.3

Suspect a glomus tumor? Perform these tests

Three clinical tests can aid in evaluating for glomus tumors.

- Love’s test involves applying pressure to the affected fingertip using the head of a pin or the end of a paperclip. The point of maximal tenderness locates the tumor.

- In Hildreth’s test, the physician applies a tourniquet to the digit and repeats the Love’s test. The test is considered suggestive of glomus tumor if the patient no longer experiences tenderness with pressure.

- The cold sensitivity test requires that the physician expose the finger to cold by, say, placing the finger in an ice bath. This exposure will elicit increased pain in a patient who has a glomus tumor.

The sensitivity and specificity of these tests, according to one study involving 18 patients, is as follows: Love’s test (100%, 78%); Hildreth’s test (77.4%, 100%); and the cold sensitivity test (100%, 100%).9 Clinical suspicion must be confirmed by histopathologic examination and the patient must be alerted to the risks of biopsy, which include permanent nail deformity.

In addition, imaging studies may aid in the diagnosis as well as determine the preoperative size and location of the tumor. Radiography may show bone erosion in certain cases, and it is useful in differentiating a glomus tumor from subungual exostosis.10 Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound imaging have also been used to identify glomus tumors and to aid in determining the method of excision.10,11

Surgical excision is the preferred approach

While there are reports of successful treatment with laser and sclerotherapy, surgical excision remains the accepted intervention to relieve pain and minimize recurrence.12,13 The optimal surgical approach, which depends on the location of the tumor,13,14 will minimize the risk of postsurgical nail deformity while allowing for complete tumor removal.

A biopsy for our patient

While the intent of our biopsy was diagnostic, it also proved to be therapeutic as our patient experienced complete resolution of her pain immediately after the procedure. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic and reported no nail deformity. We counseled her on the possibility that her symptoms might return and encouraged her to come back in for further care as needed.

Correspondence

Thomas M. Beachkofsky, MD, Wilford Hall Medical Center, Department of Dermatology, 2200 Bergquist Drive, Suite 1, Lackland AFB, TX 78236-9908; [email protected]

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

1. Baran R, Richert B. Common nail tumors. Dermatol Clin. 206;24:297-311.

2. Gombos Z, Zhang PJ. Glomus tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1448-1452.

3. Heys SD, Brittenden J, Atkinson P, et al. Glomus tumour: an analysis of 43 patients and review of the literature. Br J Surg. 1992;79:345-347.

4. McDermott EM, Weiss AP. Glomus tumors. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:1397-1400.

5. De Berker DA, Perrin C, Baran R. Localized longitudinal erythronychia: diagnostic significance and physical explanation. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1253-1257.

6. Grundmeier N, Hamm H, Weissbrich B, et al. High-risk human papillomavirus infection in Bowen’s disease of the nail unit: report of three cases and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2011;223:293-300.

7. Bach DQ, McQueen AA, Lio PA. A refractory wart? Subungual exostosis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:e3-e4.

8. Garman ME, Orengo IF, Netscher D, et al. On glomus tumors, warts, and razors. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:192-194.

9. Bhaskaranand K, Navadgi BC. Glomus tumour of the hand. J Hand Surg Br. 2002;27:229-231.

10. Takemura N, Fujii N, Tanaka T. Subungual glomus tumor diagnosis based on imaging. J Dermatol. 2006;33:389-393.

11. Matsunaga A, Ochiai T, Abe I, et al. Subungual glomus tumour: evaluation of ultrasound imaging in preoperative assessment. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:67-69.

12. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Friedman PM, Goldberg LH. Long-pulse 595-nm pulsed dye laser for the treatment of a glomus tumor. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1463-1465.

13. Netscher DT, Aburto J, Koepplinger M. Subungual glomus tumor. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:821-823.

14. Takata H, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Treatment of subungual glomus tumour. Hand Surg. 2001;6:25-27.

When war follows combat veterans home

› Ask, “Have you or a loved one ever served in the military?” as a way to uncover service-related concerns. C

› Conduct a thorough neurological evaluation with suspected mild traumatic brain injury, including vestibular, vision, postural, and neuro-cognitive assessments. C

› Use the Post-Traumatic Checklist–Military to assess individuals with possible post-traumatic stress disorder. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE A 37-year-old white woman presents for an employment physical. Your nurse reports that she also has a complaint of headaches, that she scored an 8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders identification Test-consumption (AUDiT-c), and that the result on her patient health Questionnaire (phQ-2) suggests a depressive disorder. You ask the patient whether she has served in the military and discover that, in the last 4 years, she served 2 year-long tours in Afghanistan with her Army reserve unit, returning home 6 months ago. Since her return, she has lost her job due to chronic tardiness (sleeping through her alarm, she says) and admits she has “started drinking again.” Her visit with you this day is only to undergo the physical exam required by her new employer. What are your next steps with this patient? What resources can you use to help her?

As long as human beings have engaged in combat, there have often been extraordinarily damaging psychiatric1 injuries among those who survive. Combat survivability today is 84% to 90%, the highest in the history of armed conflict,2,3 thanks to improvements in personal protective gear, vehicle armor, rapid casualty evacuation, and surgical resuscitation and stabilization that is “far forward” on the battlefield. These survivors are subsequently at high risk for a host of other medical conditions, which commonly include traumatic brain injury (TBI), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, suicide, and substance abuse.4-8

Family physicians—both civilian and uniformed—may be the first to encounter these individuals. Of the more than 2.4 million US service members who have been deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq in support of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), nearly 60% are no longer on active duty.

Among this group, only half receive care from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).9 Despite a concerted effort on the part of the Department of Defense (DoD) and the VA to develop and distribute effective, evidenced-based treatment protocols for veterans with combat-related conditions, major gaps remain in the care provided to combat veterans.10

This article seeks to help fill that gap by providing the information you need to recognize and treat common combat-related illness, as well as resources to help improve the quality of life for veterans and their families (TABLE 1).

Initial roadblocks to care

One of the biggest challenges in treating veterans with behavioral health issues is the fact that only 23% to 40% of those with mental illness seek care.11 Among the reasons veterans have offered for avoiding behavioral health care are a fear of the stigma associated with mental illness, concern that treatment will negatively affect their career, lack of comfort with mental health professionals, and the perception that mental health treatment is a “last resort.”12 Unfortunately, efforts by the DoD leadership to overcome these inherent biases have been largely unsuccessful13 and much work is still required to see that service members get the care they need.

Due to low rates of self-reporting, effective screening is essential. With this in mind, the DoD has implemented the deployment health assessment program (DHAP), which requires service members to be screened for common conditions within 60 days of deployment, within 30 days of returning, and again at 90 to 180 days after their return.

While the long-term effects of this program are yet to be determined, results to date are promising. Since the DHAP was implemented, there has been a significant decrease in occupationally impairing mental health problems and suicidal ideation requiring medical evacuation from a combat theater.14

FPs should begin with a simple question. Many of the 20+ million veterans living in the United States will not be wearing a uniform when they enter your office. Simply asking all of your patients, “Have you or a loved one ever served in the military?” may help you discover service-related questions or concerns.15,16 Underscoring the importance of such screening is the recent decision by the American Academy of Family Physicians to partner with First Lady Michelle Obama and Dr. Jill Biden in a new campaign called “Joining Forces,” which aims to support veterans and their families.16

Mild traumatic brain injury: Common—though overlooked

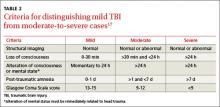

A TBI is any temporary or permanent neurologic dysfunction after a blow to the head.10,17 TBI is classified based on severity and mechanism (direct blow to the head or exposure to blast waves). Mild TBI (mTBI) is commonly referred to as a concussion and usually is not associated with loss of consciousness or altered mental status. Brain imaging results are also normal with mTBI. Severe TBI, on the other hand, is associated with prolonged loss of consciousness, altered mental status, and abnormal brain imaging results (TABLE 2).17

A unique obstacle to accurate evaluation in the field. It is important to emphasize that mTBI is a clinical diagnosis, and its detection requires honest patient communication. This can be problematic with motivated soldiers who are anxious to continue the mission and fear that any admission of symptoms might delay a return to their unit. As with a concussed athlete eager to return to the field of play, the clinical diagnosis of mTBI requires a high index of clinical suspicion and constant vigilance by the health care provider. Despite being the most common combat- related injury, mTBI is often overlooked due to the absence of obvious physical injuries.4 Recent data suggest that 28% to 60% of ser- vice members evacuated from combat have a TBI. Most of these injuries (77%) are mTBI.18-20 Improved personal protective equipment (including Kevlar helmets and body armor) and the high number of blast-related injuries are likely responsible for the high incidence of mTBI among OEF/OIF veterans.8,21,22 The prevalence of mTBI among service members not evacuated is estimated to be 20% to 30%.20

Symptoms can persist. Most patients with mTBI completely recover within 30 days of the injury. Unfortunately, 10% to 15% of mTBI patients develop chronic problems lasting months to years.4 Residual symptoms most commonly include headache, irritability, depression, sleep disturbance, impaired reasoning, memory problems, and difficulty concentrating. These symptoms are not unique to mTBI and overlap with comorbid combat diagnoses like PTSD, depression, and sleep deprivation.10 The following tools can help physicians determine whether mTBI is present.

Checking for possible mtBi. In the field, patients with possible mTBI can be screened rapidly using the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation (MACE, found at www.dvbic.org), a modification of the validated and widely used Sideline Assessment of Concussion (SAC) tool. More challenging is evaluating potential mTBI patients who present weeks or months after a traumatic event, for which there are no simple confirmatory tests. In this event, conduct a thorough neurological evaluation that includes vestibular, vision, postural, and neurocognitive assessments. For patients with persistent symptoms or possible anatomic brain abnormalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice. Patients with complications or a questionable diagnosis are best managed in consultation with a neurologist.

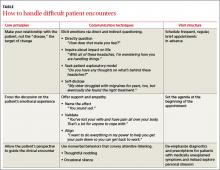

Initial treatment of mtBi is symptom-based. When practical, try nonpharmacologic interventions first (TABLE 3).10 In particular, have the patient avoid further high-risk exposures that could lead to second impact syndrome (an issue increasingly recognized in contact sports). Also critical are physical and cognitive rest and the restoration of sleep until the patient is completely asymptomatic.

If the patient exhibits irritability and depression, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are first-line treatment. Avoid narcotics and sedative-hypnotic sleep medications if treating comorbidities such as pain and sleep deprivation. The VA/DoD guideline on managing concussion and mTBI provides additional detailed, evidence-based treatment recommendations.17

Reliving the horror again and again: PTSD

PTSD is a persistent and, at times, debilitating clinical syndrome that develops after exposure to a psychologically traumatic event. It’s the second most common illness among OEF/OIF combat veterans, with an estimated prevalence of 3% to 20%, a finding consistent with prior wars.6,23-25 In the case of combat veterans, the inciting event usually involves an actual or perceived risk of death or serious injury. The individual’s response to the event involves intense fear, helplessness, or horror. The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced through intrusive and disturbing recollections or dreams that cause intense psychological distress. This, in turn, leads to a state of persistent sympathetic arousal. As symptoms are often triggered by specific cues, individuals with PTSD actively seek to avoid thoughts, situations, or stimuli associated with the event.23,26

Symptoms commonly associated with PTSD include difficulty falling or staying asleep, recurrent nightmares, hypervigilance, and an exaggerated startle response. Individuals with PTSD also have a poorer sense of well-being, a higher rate of work absenteeism, and significantly more somatic complaints than age-matched peers.27 For symptoms to be attributable to PTSD, their onset must follow a recent inciting event and must also cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of daily living. Common comorbid illnesses include mTBI, depression, and substance abuse. As with mTBI, the presence of multiple comorbidities in patients with PTSD can complicate evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment.

Diagnosis. PTSD is subdivided into acute (symptoms lasting more than one month but less than 3 months after the traumatic event) and chronic (symptoms lasting longer than 3 months after the traumatic event).28 The distinction of acute or chronic does not affect treatment, but it is useful information for the patient to have regarding prognosis and eventual outcome. Like mTBI, PTSD is a clinical diagnosis made only after a thorough, structured diagnostic interview. The use of a validated, self-administered checklist, such as the Post-Traumatic Checklist-Military (PCL-M), allows for an efficient review of a patient’s symptoms and a reliable way to track treatment progress (http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/ pages/assessments/ptsd-checklist.asp).

Treatment Options. Effective evidence-based treatments for PTSD are cognitive behavioral therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and pharmacotherapy. SSRIs and serotonin- norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have the strongest evidence for pharmacologic benefit in the treatment of PTSD.28,29 Other helpful medications are prazosin for nightmares and trazodone for sleep. Family physicians can use these medications as part of a patient-centered collaboration with the rest of the integrated care team, to offer the best chance for treatment success.10,28,30

Depression: Vets are reluctant to self-report

Combat experience is a significant risk factor for major depression. Estimates of the lifetime prevalence of depression in the general US population vary from 9% to 25% in women and 5% to 12% in men. By contrast, the prevalence of depression in OIF/OEF veterans ranges from 2% to 37%.24,31,32

Screening can yield false negatives. Many combat veterans are reluctant to self-report behavioral conditions, including depression. Screening, therefore, is important to identify potential depression and allow for intervention. Validated screening tools for depression include the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9, which are easy to use in the office setting. (See http://www.cqaimh.org/pdf/ tool_phq2.pdf [PHQ-2] and http://www. integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/ PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf [PHQ-9]). Importantly, some veterans will have a negative depression screen on return from deployment, and then test positive 6 to 12 months later.24 Explanations for the early false-negative results include the excitement of being home and patients intentionally answering questions inaccurately to avoid excessive screening at their home base.11

Treatment is most effective with a combination approach. As with most cases of depression, combining psychotherapy and psychopharmacology appears to be most effective for treating depression related to combat experience.33,34 While SSRIs and SNRIs are typical first-line pharmacologic agents, combat veterans often have comorbid mTBI, PTSD, or substance abuse issues that may influence the initial choice of therapy35 (TABLE 3).10

Suicide is on the rise in the military

Historically, the incidence of suicide has been 25% lower in military personnel than in civilian peers.36 However, between 2005 and 2009, the incidence of suicide in the Marine Corps and Army almost doubled.37 While the exact reasons remain unknown, it is likely due to prolonged and repeated deployments to a combat environment.12 While the incidence of suicide has been particularly high in the Army (22 per 100,000 active-duty and reserve personnel per year), all services have been affected. In fact, since 2009, the number of suicides among active duty service members exceeds those killed in action.37

Consider all veterans to be at risk for suicide, and screen accordingly. An effective screening tool is the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), which is able to predict those most at risk for an impending suicide attempt.34 Service members identified as high risk for suicide require unhindered access to care. The VA has worked to improve access to care and provide evidence-based point-of-care treatment strategies.38 Available resources can be found in TABLE 1.

Unfortunately, even with effective screening and treatment, not all suicides can be prevented. Studies have demonstrated that approximately 65% of service members who commit suicide had no known history of communicating their suicidal intent. Sadly, 25% of service members who committed suicide had seen a mental health provider within the previous 30 days.39

Alcohol abuse is common; opioids present a unique risk

Excessive use of alcohol and recreational and prescription drugs is common among OEF/ OIF veterans, especially those with comorbid mental health disorders. Retrospective cross-sectional studies show that 11% to 20% of OEF/OIF veterans met DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders.40-42 At highest risk are single enlisted men under the age of 24 in the Army or Marine Corps who serve in a combat-specific capacity. Interestingly, the prevalence of substance use disorders among OEF/OIF veterans closely mirrors that reported in epidemiologic studies of Vietnam veterans (11%-14%).41 This similarity, combined with the 39% lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders among Vietnam veterans, may foreshadow a similar lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders among OEF/OIF veterans.41

Most-abused substances. Alcohol is the most commonly abused substance among OEF/OIF veterans (10%-20%).40,41,43-45 Other abused substances include opioids (prescribed or illicitly obtained), synthetic marijuana (“Spice” and “K2”), and “bath salts” (synthetic stimulants) (W.M. Sauve, MD, personal communication, August 27, 2012).

OEF/OIF veterans seem to be at particular risk for developing problems related to opioid use. A 2012 retrospective cohort study showed that veterans with non–cancer- related pain diagnoses treated with opioid analgesics had an increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes compared with those not treated with opioid analgesics (9.5% vs 4.1%; relative risk [RR]=2.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.20-2.46). These outcomes included traumatic accidents, overdoses, self-inflicted injuries, and injuries related to violence. This study also demonstrated that, compared with veterans without mental illness, veterans with mental illness (particularly PTSD) and non–cancer-related pain were significantly more likely to receive opioids to treat their pain and had a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes, including overdose.46,47

Recreational use of synthetic marijuana and “bath salts” has increased in recent years. These substances are commonly labeled “not for human consumption,” which allows them to remain outside US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation and be sold legally in the United States. Efforts to prohibit the sale or possession of these drugs, including the Federal Synthetic Bath Salt Ban in 2012, have fallen short, often due to creative product ”re-engineering.”33 Synthetic marijuana and stimulants are inexpensive, readily available, and perceived by users to be safe. Health care providers are often unaware that their patients are using these products. Adverse health outcomes associated with the use of these synthetic drugs include memory loss, depression, and psychosis.

These alcohol and drug screens can help

One efficient screening tool to identify veterans at risk for alcohol abuse is the AUDIT-C, developed by the World Health Organization. This brief 3-question test identifies past-year hazardous drinking and alcohol abuse or dependence with >79% sensitivity and >56% specificity in male veterans, and >66% sensitivity and >87% specificity in female veterans. These numbers are similar to those provided by the full 10-question AUDIT.48,49 The Drug Abuse Screen Test-10 (DAST-10) provides a similar screening instrument for other substances. Condensed from the original DAST-28 instrument, the DAST-10 identifies high-risk substance abuse with 74% to 94% sensitivity and 68% to 88% specificity.3

Screen for comorbidities. When you see veterans with a diagnosis of substance abuse, also evaluate for comorbid disease. Most veterans with substance use disorders (82%-93%) have at least one other mental health diagnosis (a 45% greater risk than that of civilians with substance abuse disorders),50 most commonly PTSD, depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders.41,44,45 A number of hypotheses exist to explain the association between substance use disorders and other mental health diagnoses (“dual diagnoses”). The prevailing theory, in both veteran and civilian populations, is that substance abuse is an attempt to self-treat mental illness. Other evidence suggests that substance abuse promotes the development of mental illness, either by leading to a higher risk for traumatic experiences (increasing the chance of developing PTSD) or through a direct biochemical mechanism. Finally, con- current substance use disorder and mental illness may be due to an undefined genetic or biological vulnerability.38,44 This complicated relationship between substance abuse and behavioral health reinforces the need for screening, early diagnosis, and a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to treatment.

Treatment options. Office-based treatment options for narcotic and alcohol abuse and dependency are available to family physicians. Methadone has been used since the 1950s to treat opioid addiction and remains one of the mainstays of outpatient treatment.47,51 Originally, methadone was restricted to detoxification and maintenance treatment in narcotic addiction treatment programs approved by the FDA. In 1976, this restriction was lifted, and all physicians registered with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) were permitted to prescribe methadone for analgesia.

In 2002, the FDA approved buprenorphine monotherapy and the combination product buprenorphine/naloxone for the treatment of opioid addiction. The prescribing of buprenorphine products requires physicians to undergo extra training, declare to the DEA their intent to prescribe buprenorphine, and obtain a special DEA identification number.52,53 Physicians interested in finding out more about buprenorphine treatment and prescribing requirements can go to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Web page at http://samhsa.gov.

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor agonist that is used primarily to treat alcohol dependency, and is thought to work by reducing the craving for alcohol. Multiple studies have proven the efficacy of naltrexone in an outpatient setting when used alone or in combination with psychotherapy.54,55 If you are uncomfortable or unfamiliar with the use or prescribing of these medications, referral to a substance abuse clinic specializing in dual-diagnosis treatment (TABLE 1) may offer optimal outcomes for patients with substance abuse disorders and other mental illness.

Cognitive behavioral therapy—including coping skills training, relapse prevention, contingency management, and behavioral couples’ therapy—and 12-step treatment programs are evidence-based options for the treatment of substance abuse disorders. Behavioral counseling interventions in the primary care setting (typically lasting 5-15 minutes) result in decreases in alcohol consumption, heavy drinking episodes, drinking above recommended amounts, and the number of days spent in the hospital, but have not been demonstrated to affect mortality, alcohol-related liver problems, outpatient visits, legal problems, or quality of life.56 Resources can be found at www.niaaa.nih.gov. For patients with dual diagnoses, it is not yet known whether sequential therapy (in which substance abuse is treated first, followed by treatment of the comorbid mental illness) or concurrent therapy results in better outcomes.57

CASE Your patient’s history of recent combat service, acknowledgement of employment and behavioral difficulties, and initial screening results lead you to diagnose alcoholism and depression. Additionally, she denies any suicidal ideation, but admits to experimenting with synthetic marijuana. After some discussion, she agrees to see your clinic’s social worker, and you start her on an SSri with scheduled follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shawn Kane, MD, USASoc, Attn: Surgeon (AomD), 2929 Desert Storm Drive, Ft. Bragg, NC 28310, or PO Box 3639 Pinehurst, NC 28374; [email protected]

1. Wessely S. Risk, psychiatry and the military. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:459-466.

2. Gawande A. Casualties of war—military care for the wounded from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2471-2475.

3. Kotwal RS, Montgomery HR, Kotwal BM, et al. Eliminating pre- ventable death on the battlefield. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1350-1358.

4. Belanger HG, Uomoto JM, Vanderploeg RD. The Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA’s) Polytrauma System of Care for mild traumatic brain injury: costs, benefits, and controversies. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24:4-13.

5. Galarneau MR, Woodruff SI, Dye JL, et al. Traumatic brain in- jury during Operation Iraqi Freedom: findings from the United States Navy-Marine Corps Combat Trauma Registry. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:950-957.

6. Hermann BA, Shiner B, Friedman MJ. Epidemiology and preven- tion of combat-related post-traumatic stress in OEF/OIF/OND service members. Mil Med. 2012;177:1-6.

7. Uomoto JM. Best practices in veteran traumatic brain injury care. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2012;27:241-243.

8. Warden D. Military TBI during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:398-402.

9. Taylor BC, Hagel EM, Carlson KF, et al. Prevalence and costs of co-occurring traumatic brain injury with and without psychiatric disturbance and pain among Afghanistan and Iraq War Veteran V.A. users. Med Care. 2012;50:342-346.

10. Quinlan JD, Guaron MR, Deschere BR, et al. Care of the returning veteran. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:43-49.

11. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13-22.

12. Hoge CW, Castro CA. Preventing suicides in US service mem- bers and veterans: concerns after a decade of war. JAMA. 2012;308:671-672.

13. Jaffe G. New name for PTSD could mean less stigma. The Washington Post. May 5, 2012. Available at: http://articles. washingtonpost.com/2012-05-05/world/35454931_1_ptsd-post- traumatic-stress-psychiatrists. Accessed June 19, 2013.

14. Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Parker JR, et al. Effectiveness of mental health screening and coordination of in-theater care prior to deployment to Iraq: a cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:378-385.

15. United States Census Bureau. Sex by age by veteran sta- tus for civilian population 18 years and over. 2010 American community survey 1-year estimates. Available at: https:// d3gqux9sl0z33u.cloudfront.net/AA/AT/gambillingonjustice- com/downloads/206273/ACS_10_1YR_B21001A.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2013.

16. American Academy of Family Physicians. Joining forces. Avail- able at: http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/membership/ initiatives/joiningforces.html. Accessed June 19, 2013.

17. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Concussion/Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. April 2009. Available at: http://www. healthquality.va.gov/mtbi/concussion_mtbi_full_1_0.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2013.

18. Lew HL, Poole JH, Alvarez S, et al. Soldiers with occult traumatic brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84:393-398.

19. Marshall KR, Holland SL, Meyer KS, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Mil Med. 2012;177:67- 75.

20. Terrio H, Brenner LA, Ivins BJ, et al. Traumatic brain injury screening: preliminary findings in a US Army Brigade Combat Team. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24:14-23.

21. Mossadegh S, Tai N, Midwinter M, et al. Improvised explosive de- vice related pelvi-perineal trauma: anatomic injuries and surgical management. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:S24-S31.

22. Okie S. Traumatic brain injury in the war zone. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2043-2047.

23. Espinoza JM. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the perceived consequences of seeking therapy among US Army special forces operators exposed to combat. J Psychol Issues Organ Culture. 2010;1:6-28.

24. Grieger TA, Cozza SJ, Ursano RJ, et al. Posttraumatic stress dis- order and depression in battle-injured soldiers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1777-1783.

25. Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295:1023-1032.

26. Adler AB, Wright KM, Bliese PD, et al. A2 diagnostic criterion for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:301-308.

27. Hoge CW, Terhakopian A, Castro CA, et al. Association of post- traumatic stress disorder with somatic symptoms, health care vis- its, and absenteeism among Iraq war veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:150-153.

28. Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Clin- ical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress. October 2010. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ ptsd/cpg_PTSD-FULL-201011612.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2013.

29. Alexander W. Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disor- der in combat veterans: focus on antidepressants and atypical antipsychotic agents. P T. 2012;37:32-38.

30. Wisco BE, Marx BP, Keane TM. Screening, diagnosis, and treat- ment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 2012;177:7-13.

31. Gadermann AM, Engel CC, Naifeh JA, et al. Prevalence of DSM-IV major depression among U.S. military personnel: meta-analysis and simulation. Mil Med. 2012;177:47-59.

32. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health dis- orders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307:940-947.

33. Perrone M. Many drugs remain legal after ‘bath salts’ ban. Boston. com. July 25, 2012. Available at: http://articles.boston.com/2012- 07-25/lifestyle/32850962_1_bath-salts-mdpv-synthetic-drugs. Accessed June 19, 2013.

34. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Se- verity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency find- ings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266-1277.

35. Greenberg J, Tesfazion AA, Robinson CS. Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. Mil Med. 2012;177:60-66.

36. Eaton KM, Messer SC, Garvey Wilson AL, et al. Strengthening the validity of population-based suicide rate comparisons: an il- lustration using U.S. military and civilian data. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2006;36:182-191.

37. Miller M, Azrael D, Barber C, et al. A call to link data to answer pressing questions about suicide risk among veterans. Am J Pub Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S20-S22.

38. Department of Veterans Affairs. Report of the Blue Ribbon Work Group on suicide prevention in the veteran population. June 2008. Available at: http://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_ prevention/Blue_Ribbon_Report-FINAL_June-30-08.pdf. Accessed July 18, 2013.

39. Kinn JT, Luxton DD, Reger MA, et al. Department of Defense sui- cide event report: calendar year 2010 annual report. September 2011. Available at: http://t2health.org/sites/default/files/dodser/ DoDSER_2010_Annual_Report.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2013.

40. Fontana A, Rosenheck R. Treatment-seeking veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan: comparison with veterans of previous wars. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:513-521.

41. Seal KH, Cohen G, Waldrop A, et al. Substance use disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in VA healthcare, 2001-2010: implications for screening, diagnosis and treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:93-101.

42. Mirza RA, Eick-Cost A, Otto JL. The risk of mental health disor- ders among U.S. military personnel infected with human immu- nodeficiency virus, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000- 2011. MSMR. 2012;19:10-13.

43. Bohnert AS, Ilgen MA, Bossarte RM, et al. Veteran status and alco- hol use in men in the United States. Mil Med. 2012;177:198-203.

44. Erbes CR, Kaler ME, Schult T, et al. Mental health diagnosis and occupational functioning in National Guard/Reserve veterans re- turning from Iraq. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48:1159-1170.

45. Stecker T, Fortney J, Owen R, et al. Co-occurring medical, psychi- atric, and alcohol-related disorders among veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychosomatics. 2010;51:503-507.

46. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health dis- orders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307:940-947.

47. Praveen KT, Law F, O’Shea J, et al. Opioid dependence. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:565-566.

48. Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:821-829.

49. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789-1795.

50. Farrell M, Howes S, Taylor C, et al. Substance misuse and psychi- atric comorbidity: an overview of the OPCS National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Addict Behav. 1998;23:909-918.

51. Toombs JD, Kral LA. Methadone treatment for pain states. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1353-1358.

52. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Clinical Guidelines for the Use of Buprenorphine in the Treatment of Opioid Addiction. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) series 40. DHHS pub- lication (SMA) 04-3939. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2004. Available at: http:// buprenorphine.samhsa.gov/Bup_Guidelines.pdf. Accessed June 19, 2013.

53. U.S.DepartmentofHealthandHumanServices,SubstanceAbuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. About buprenorphine therapy. Available at: http://buprenorphine. samhsa.gov/about.html. Accessed June 19, 2013.

54. Volpicelli JR, Alterman AI, Hayashida M, et al. Naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:876-880.

55. O’Brien CP, Volpicelli LA, Volpicelli JR. Naltrexone in the treat- ment of alcoholism: a clinical review. Alcohol. 1996;13:35-39.

56. Jonas DE, Garbutt JC, Amick HR, et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:645-654.

57. van Dam D, Vedel E, Ehring T, et al. Psychological treatments for concurrent posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use dis- order: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:202-214.

› Ask, “Have you or a loved one ever served in the military?” as a way to uncover service-related concerns. C

› Conduct a thorough neurological evaluation with suspected mild traumatic brain injury, including vestibular, vision, postural, and neuro-cognitive assessments. C

› Use the Post-Traumatic Checklist–Military to assess individuals with possible post-traumatic stress disorder. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE A 37-year-old white woman presents for an employment physical. Your nurse reports that she also has a complaint of headaches, that she scored an 8 on the Alcohol Use Disorders identification Test-consumption (AUDiT-c), and that the result on her patient health Questionnaire (phQ-2) suggests a depressive disorder. You ask the patient whether she has served in the military and discover that, in the last 4 years, she served 2 year-long tours in Afghanistan with her Army reserve unit, returning home 6 months ago. Since her return, she has lost her job due to chronic tardiness (sleeping through her alarm, she says) and admits she has “started drinking again.” Her visit with you this day is only to undergo the physical exam required by her new employer. What are your next steps with this patient? What resources can you use to help her?

As long as human beings have engaged in combat, there have often been extraordinarily damaging psychiatric1 injuries among those who survive. Combat survivability today is 84% to 90%, the highest in the history of armed conflict,2,3 thanks to improvements in personal protective gear, vehicle armor, rapid casualty evacuation, and surgical resuscitation and stabilization that is “far forward” on the battlefield. These survivors are subsequently at high risk for a host of other medical conditions, which commonly include traumatic brain injury (TBI), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, suicide, and substance abuse.4-8

Family physicians—both civilian and uniformed—may be the first to encounter these individuals. Of the more than 2.4 million US service members who have been deployed to Afghanistan or Iraq in support of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), nearly 60% are no longer on active duty.

Among this group, only half receive care from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).9 Despite a concerted effort on the part of the Department of Defense (DoD) and the VA to develop and distribute effective, evidenced-based treatment protocols for veterans with combat-related conditions, major gaps remain in the care provided to combat veterans.10

This article seeks to help fill that gap by providing the information you need to recognize and treat common combat-related illness, as well as resources to help improve the quality of life for veterans and their families (TABLE 1).

Initial roadblocks to care

One of the biggest challenges in treating veterans with behavioral health issues is the fact that only 23% to 40% of those with mental illness seek care.11 Among the reasons veterans have offered for avoiding behavioral health care are a fear of the stigma associated with mental illness, concern that treatment will negatively affect their career, lack of comfort with mental health professionals, and the perception that mental health treatment is a “last resort.”12 Unfortunately, efforts by the DoD leadership to overcome these inherent biases have been largely unsuccessful13 and much work is still required to see that service members get the care they need.

Due to low rates of self-reporting, effective screening is essential. With this in mind, the DoD has implemented the deployment health assessment program (DHAP), which requires service members to be screened for common conditions within 60 days of deployment, within 30 days of returning, and again at 90 to 180 days after their return.

While the long-term effects of this program are yet to be determined, results to date are promising. Since the DHAP was implemented, there has been a significant decrease in occupationally impairing mental health problems and suicidal ideation requiring medical evacuation from a combat theater.14

FPs should begin with a simple question. Many of the 20+ million veterans living in the United States will not be wearing a uniform when they enter your office. Simply asking all of your patients, “Have you or a loved one ever served in the military?” may help you discover service-related questions or concerns.15,16 Underscoring the importance of such screening is the recent decision by the American Academy of Family Physicians to partner with First Lady Michelle Obama and Dr. Jill Biden in a new campaign called “Joining Forces,” which aims to support veterans and their families.16

Mild traumatic brain injury: Common—though overlooked

A TBI is any temporary or permanent neurologic dysfunction after a blow to the head.10,17 TBI is classified based on severity and mechanism (direct blow to the head or exposure to blast waves). Mild TBI (mTBI) is commonly referred to as a concussion and usually is not associated with loss of consciousness or altered mental status. Brain imaging results are also normal with mTBI. Severe TBI, on the other hand, is associated with prolonged loss of consciousness, altered mental status, and abnormal brain imaging results (TABLE 2).17

A unique obstacle to accurate evaluation in the field. It is important to emphasize that mTBI is a clinical diagnosis, and its detection requires honest patient communication. This can be problematic with motivated soldiers who are anxious to continue the mission and fear that any admission of symptoms might delay a return to their unit. As with a concussed athlete eager to return to the field of play, the clinical diagnosis of mTBI requires a high index of clinical suspicion and constant vigilance by the health care provider. Despite being the most common combat- related injury, mTBI is often overlooked due to the absence of obvious physical injuries.4 Recent data suggest that 28% to 60% of ser- vice members evacuated from combat have a TBI. Most of these injuries (77%) are mTBI.18-20 Improved personal protective equipment (including Kevlar helmets and body armor) and the high number of blast-related injuries are likely responsible for the high incidence of mTBI among OEF/OIF veterans.8,21,22 The prevalence of mTBI among service members not evacuated is estimated to be 20% to 30%.20

Symptoms can persist. Most patients with mTBI completely recover within 30 days of the injury. Unfortunately, 10% to 15% of mTBI patients develop chronic problems lasting months to years.4 Residual symptoms most commonly include headache, irritability, depression, sleep disturbance, impaired reasoning, memory problems, and difficulty concentrating. These symptoms are not unique to mTBI and overlap with comorbid combat diagnoses like PTSD, depression, and sleep deprivation.10 The following tools can help physicians determine whether mTBI is present.

Checking for possible mtBi. In the field, patients with possible mTBI can be screened rapidly using the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation (MACE, found at www.dvbic.org), a modification of the validated and widely used Sideline Assessment of Concussion (SAC) tool. More challenging is evaluating potential mTBI patients who present weeks or months after a traumatic event, for which there are no simple confirmatory tests. In this event, conduct a thorough neurological evaluation that includes vestibular, vision, postural, and neurocognitive assessments. For patients with persistent symptoms or possible anatomic brain abnormalities, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice. Patients with complications or a questionable diagnosis are best managed in consultation with a neurologist.

Initial treatment of mtBi is symptom-based. When practical, try nonpharmacologic interventions first (TABLE 3).10 In particular, have the patient avoid further high-risk exposures that could lead to second impact syndrome (an issue increasingly recognized in contact sports). Also critical are physical and cognitive rest and the restoration of sleep until the patient is completely asymptomatic.

If the patient exhibits irritability and depression, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are first-line treatment. Avoid narcotics and sedative-hypnotic sleep medications if treating comorbidities such as pain and sleep deprivation. The VA/DoD guideline on managing concussion and mTBI provides additional detailed, evidence-based treatment recommendations.17

Reliving the horror again and again: PTSD

PTSD is a persistent and, at times, debilitating clinical syndrome that develops after exposure to a psychologically traumatic event. It’s the second most common illness among OEF/OIF combat veterans, with an estimated prevalence of 3% to 20%, a finding consistent with prior wars.6,23-25 In the case of combat veterans, the inciting event usually involves an actual or perceived risk of death or serious injury. The individual’s response to the event involves intense fear, helplessness, or horror. The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced through intrusive and disturbing recollections or dreams that cause intense psychological distress. This, in turn, leads to a state of persistent sympathetic arousal. As symptoms are often triggered by specific cues, individuals with PTSD actively seek to avoid thoughts, situations, or stimuli associated with the event.23,26

Symptoms commonly associated with PTSD include difficulty falling or staying asleep, recurrent nightmares, hypervigilance, and an exaggerated startle response. Individuals with PTSD also have a poorer sense of well-being, a higher rate of work absenteeism, and significantly more somatic complaints than age-matched peers.27 For symptoms to be attributable to PTSD, their onset must follow a recent inciting event and must also cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of daily living. Common comorbid illnesses include mTBI, depression, and substance abuse. As with mTBI, the presence of multiple comorbidities in patients with PTSD can complicate evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment.

Diagnosis. PTSD is subdivided into acute (symptoms lasting more than one month but less than 3 months after the traumatic event) and chronic (symptoms lasting longer than 3 months after the traumatic event).28 The distinction of acute or chronic does not affect treatment, but it is useful information for the patient to have regarding prognosis and eventual outcome. Like mTBI, PTSD is a clinical diagnosis made only after a thorough, structured diagnostic interview. The use of a validated, self-administered checklist, such as the Post-Traumatic Checklist-Military (PCL-M), allows for an efficient review of a patient’s symptoms and a reliable way to track treatment progress (http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/ pages/assessments/ptsd-checklist.asp).

Treatment Options. Effective evidence-based treatments for PTSD are cognitive behavioral therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and pharmacotherapy. SSRIs and serotonin- norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) have the strongest evidence for pharmacologic benefit in the treatment of PTSD.28,29 Other helpful medications are prazosin for nightmares and trazodone for sleep. Family physicians can use these medications as part of a patient-centered collaboration with the rest of the integrated care team, to offer the best chance for treatment success.10,28,30

Depression: Vets are reluctant to self-report

Combat experience is a significant risk factor for major depression. Estimates of the lifetime prevalence of depression in the general US population vary from 9% to 25% in women and 5% to 12% in men. By contrast, the prevalence of depression in OIF/OEF veterans ranges from 2% to 37%.24,31,32

Screening can yield false negatives. Many combat veterans are reluctant to self-report behavioral conditions, including depression. Screening, therefore, is important to identify potential depression and allow for intervention. Validated screening tools for depression include the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9, which are easy to use in the office setting. (See http://www.cqaimh.org/pdf/ tool_phq2.pdf [PHQ-2] and http://www. integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/ PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf [PHQ-9]). Importantly, some veterans will have a negative depression screen on return from deployment, and then test positive 6 to 12 months later.24 Explanations for the early false-negative results include the excitement of being home and patients intentionally answering questions inaccurately to avoid excessive screening at their home base.11

Treatment is most effective with a combination approach. As with most cases of depression, combining psychotherapy and psychopharmacology appears to be most effective for treating depression related to combat experience.33,34 While SSRIs and SNRIs are typical first-line pharmacologic agents, combat veterans often have comorbid mTBI, PTSD, or substance abuse issues that may influence the initial choice of therapy35 (TABLE 3).10

Suicide is on the rise in the military

Historically, the incidence of suicide has been 25% lower in military personnel than in civilian peers.36 However, between 2005 and 2009, the incidence of suicide in the Marine Corps and Army almost doubled.37 While the exact reasons remain unknown, it is likely due to prolonged and repeated deployments to a combat environment.12 While the incidence of suicide has been particularly high in the Army (22 per 100,000 active-duty and reserve personnel per year), all services have been affected. In fact, since 2009, the number of suicides among active duty service members exceeds those killed in action.37

Consider all veterans to be at risk for suicide, and screen accordingly. An effective screening tool is the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), which is able to predict those most at risk for an impending suicide attempt.34 Service members identified as high risk for suicide require unhindered access to care. The VA has worked to improve access to care and provide evidence-based point-of-care treatment strategies.38 Available resources can be found in TABLE 1.

Unfortunately, even with effective screening and treatment, not all suicides can be prevented. Studies have demonstrated that approximately 65% of service members who commit suicide had no known history of communicating their suicidal intent. Sadly, 25% of service members who committed suicide had seen a mental health provider within the previous 30 days.39

Alcohol abuse is common; opioids present a unique risk

Excessive use of alcohol and recreational and prescription drugs is common among OEF/ OIF veterans, especially those with comorbid mental health disorders. Retrospective cross-sectional studies show that 11% to 20% of OEF/OIF veterans met DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for substance use disorders.40-42 At highest risk are single enlisted men under the age of 24 in the Army or Marine Corps who serve in a combat-specific capacity. Interestingly, the prevalence of substance use disorders among OEF/OIF veterans closely mirrors that reported in epidemiologic studies of Vietnam veterans (11%-14%).41 This similarity, combined with the 39% lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders among Vietnam veterans, may foreshadow a similar lifetime prevalence of substance use disorders among OEF/OIF veterans.41

Most-abused substances. Alcohol is the most commonly abused substance among OEF/OIF veterans (10%-20%).40,41,43-45 Other abused substances include opioids (prescribed or illicitly obtained), synthetic marijuana (“Spice” and “K2”), and “bath salts” (synthetic stimulants) (W.M. Sauve, MD, personal communication, August 27, 2012).

OEF/OIF veterans seem to be at particular risk for developing problems related to opioid use. A 2012 retrospective cohort study showed that veterans with non–cancer- related pain diagnoses treated with opioid analgesics had an increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes compared with those not treated with opioid analgesics (9.5% vs 4.1%; relative risk [RR]=2.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.20-2.46). These outcomes included traumatic accidents, overdoses, self-inflicted injuries, and injuries related to violence. This study also demonstrated that, compared with veterans without mental illness, veterans with mental illness (particularly PTSD) and non–cancer-related pain were significantly more likely to receive opioids to treat their pain and had a higher risk of adverse clinical outcomes, including overdose.46,47

Recreational use of synthetic marijuana and “bath salts” has increased in recent years. These substances are commonly labeled “not for human consumption,” which allows them to remain outside US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation and be sold legally in the United States. Efforts to prohibit the sale or possession of these drugs, including the Federal Synthetic Bath Salt Ban in 2012, have fallen short, often due to creative product ”re-engineering.”33 Synthetic marijuana and stimulants are inexpensive, readily available, and perceived by users to be safe. Health care providers are often unaware that their patients are using these products. Adverse health outcomes associated with the use of these synthetic drugs include memory loss, depression, and psychosis.

These alcohol and drug screens can help

One efficient screening tool to identify veterans at risk for alcohol abuse is the AUDIT-C, developed by the World Health Organization. This brief 3-question test identifies past-year hazardous drinking and alcohol abuse or dependence with >79% sensitivity and >56% specificity in male veterans, and >66% sensitivity and >87% specificity in female veterans. These numbers are similar to those provided by the full 10-question AUDIT.48,49 The Drug Abuse Screen Test-10 (DAST-10) provides a similar screening instrument for other substances. Condensed from the original DAST-28 instrument, the DAST-10 identifies high-risk substance abuse with 74% to 94% sensitivity and 68% to 88% specificity.3

Screen for comorbidities. When you see veterans with a diagnosis of substance abuse, also evaluate for comorbid disease. Most veterans with substance use disorders (82%-93%) have at least one other mental health diagnosis (a 45% greater risk than that of civilians with substance abuse disorders),50 most commonly PTSD, depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorders.41,44,45 A number of hypotheses exist to explain the association between substance use disorders and other mental health diagnoses (“dual diagnoses”). The prevailing theory, in both veteran and civilian populations, is that substance abuse is an attempt to self-treat mental illness. Other evidence suggests that substance abuse promotes the development of mental illness, either by leading to a higher risk for traumatic experiences (increasing the chance of developing PTSD) or through a direct biochemical mechanism. Finally, con- current substance use disorder and mental illness may be due to an undefined genetic or biological vulnerability.38,44 This complicated relationship between substance abuse and behavioral health reinforces the need for screening, early diagnosis, and a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to treatment.

Treatment options. Office-based treatment options for narcotic and alcohol abuse and dependency are available to family physicians. Methadone has been used since the 1950s to treat opioid addiction and remains one of the mainstays of outpatient treatment.47,51 Originally, methadone was restricted to detoxification and maintenance treatment in narcotic addiction treatment programs approved by the FDA. In 1976, this restriction was lifted, and all physicians registered with the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) were permitted to prescribe methadone for analgesia.

In 2002, the FDA approved buprenorphine monotherapy and the combination product buprenorphine/naloxone for the treatment of opioid addiction. The prescribing of buprenorphine products requires physicians to undergo extra training, declare to the DEA their intent to prescribe buprenorphine, and obtain a special DEA identification number.52,53 Physicians interested in finding out more about buprenorphine treatment and prescribing requirements can go to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Web page at http://samhsa.gov.

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor agonist that is used primarily to treat alcohol dependency, and is thought to work by reducing the craving for alcohol. Multiple studies have proven the efficacy of naltrexone in an outpatient setting when used alone or in combination with psychotherapy.54,55 If you are uncomfortable or unfamiliar with the use or prescribing of these medications, referral to a substance abuse clinic specializing in dual-diagnosis treatment (TABLE 1) may offer optimal outcomes for patients with substance abuse disorders and other mental illness.

Cognitive behavioral therapy—including coping skills training, relapse prevention, contingency management, and behavioral couples’ therapy—and 12-step treatment programs are evidence-based options for the treatment of substance abuse disorders. Behavioral counseling interventions in the primary care setting (typically lasting 5-15 minutes) result in decreases in alcohol consumption, heavy drinking episodes, drinking above recommended amounts, and the number of days spent in the hospital, but have not been demonstrated to affect mortality, alcohol-related liver problems, outpatient visits, legal problems, or quality of life.56 Resources can be found at www.niaaa.nih.gov. For patients with dual diagnoses, it is not yet known whether sequential therapy (in which substance abuse is treated first, followed by treatment of the comorbid mental illness) or concurrent therapy results in better outcomes.57

CASE Your patient’s history of recent combat service, acknowledgement of employment and behavioral difficulties, and initial screening results lead you to diagnose alcoholism and depression. Additionally, she denies any suicidal ideation, but admits to experimenting with synthetic marijuana. After some discussion, she agrees to see your clinic’s social worker, and you start her on an SSri with scheduled follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shawn Kane, MD, USASoc, Attn: Surgeon (AomD), 2929 Desert Storm Drive, Ft. Bragg, NC 28310, or PO Box 3639 Pinehurst, NC 28374; [email protected]

› Ask, “Have you or a loved one ever served in the military?” as a way to uncover service-related concerns. C

› Conduct a thorough neurological evaluation with suspected mild traumatic brain injury, including vestibular, vision, postural, and neuro-cognitive assessments. C