User login

Finger injuries: 5 cases to test your skills

Some finger injuries require little more than icing; others are more serious, often emergent, conditions with outcomes that are dependent on an accurate diagnosis and rapid initiation of treatment.

The 5 cases that follow describe injuries with varying degrees of severity. Read each case and select the multiple-choice answer you think is most appropriate. Then read on to find out if you were right—and to learn more about the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment for each type of injury.

CASE 1 A 45-year-old auto body worker walks into your office at 5:30 pm, just as your staff is closing up for the day. A few hours ago, he reports, he was spray-painting a car with a paint gun when he felt a sudden pain in his right index finger. His immediate thought was that he had torn something, but the pain quickly subsided. So he continued to work—until about 45 minutes ago, when the pain became so intense that he knew he needed medical care right away.

Examination reveals redness and increased skin temperature on the radial palmar side of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint of the index finger. Two-point discrimination is decreased to 10 mm, vs 5 mm on the same finger of the opposite hand. The patient can flex his PIP and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints but complains of pain and stiffness. You obtain x-rays of the injured

finger (FIGURE 1).

WHAT'S YOUR NEXT STEP?

B. Update the patient’s tetanus immunization and start him on a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

C. Put a dorsal splint on the injured finger in the “safe hand” position and schedule a return visit in one week.

D. “Buddy tape” the index and long fingers and refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

Answer: Send the auto-body worker to the nearest ED and call ahead (A).

This patient sustained a high-pressure injection injury to the PIP joint of his right index finger. The patient’s description of how the injury occurred suggested this, and the radiograph confirmed it by showing some paint under the skin (See arrow, FIGURE 1). Such injuries occur when a high pressure (typically from a hose) forces air or a substance—eg, diesel fuel, paint, or solvent—through the skin into the finger.

Although high-pressure injection injury often has a benign presentation, it is actually a medical emergency. If aggressive surgical debridement does not occur within a 6-hour window, the patient runs a high risk for amputation of the digit.1 A hand surgeon should be contacted as soon as possible.

The severity of the injury varies, depending on the amount of pressure (amputation rates are as high as 43% when the pressure per square inch >1000), the type of material injected (diesel fuel is the most toxic), and the location.1,2

Instruct the patient to remove any jewelry, such as a wedding band or watch, on the affected hand or wrist, and to keep the hand elevated. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started right away, and a tetanus booster given, if needed. Do not apply heat or use local anesthesia, as both can increase the swelling.2

CASE 2 A 17-year-old cheerleader comes to see you on Monday afternoon, after injuring her left pinky during a Friday night game. The patient, who is right-handed, points to the left PIP joint when you ask where it hurts, and tells you that the finger is stiff. She has been icing it since the injury occurred, to make sure she is ready to cheer by next weekend.

The injury occurred when she was spotting another cheerleader during a routine, the patient reports, adding that the pinky was “dislocated.” The coach “popped” it back in place and buddy-taped the injured finger to her ring finger.

The patient is able to flex and extend the DIP joint on the pinky when the PIP joint is stabilized. She can also flex the PIP joint unassisted, but has difficulty extending it. The digit demonstrates slight flexion of the PIP joint. You note tenderness over both collateral ligaments and the dorsum of the PIP joint, but not over the volar aspect of the injured finger, and order x-rays (FIGURE 2).

WHAT'S YOUR NEXT STEP?

B. Refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

C. Apply an extension block splint so the patient can flex the finger but not extend it, and schedule a follow-up appointment in one to 2 weeks.

D. Apply an aluminum dorsal splint, allowing the DIP joint to be flexed and keeping the PIP joint in full extension for 4 weeks.

Answer: Refer the cheerleader to a hand surgeon (B).

This patient has a rupture of the central extensor tendon of the pinky finger at the PIP joint. The mechanism of injury and her inability to completely extend the injured finger at the PIP joint alert you to this type of injury. An x-ray may sometimes be normal but in this case, it shows the flexion of the PIP joint. Surgical repair of the rupture should be scheduled without delay.3

Most injuries at this joint occur from forced extension, not flexion, and result in a volar plate rupture.4 If swelling and pain make evaluation of an acute dislocation injury difficult, splinting in the “safe hand” position for 72 hours while icing the injured finger will make it possible to do a more detailed follow-up exam.3

Extended periods of splinting can make the PIP joint very stiff, however—and harder to treat than the original injury.5 If the rupture of the central extensor tendon is undetected or simply not treated, a Boutonniere deformity, in which the PIP joint is flexed and the DIP joint is hyperextended, is the likely result.3

CASE 3 A 24-year-old man “jammed” his right ring finger while trying to catch a ball that was passed to him during a pick-up basketball game. He has rested and iced the finger for a couple of days, but it’s still painful and hard to move. He has no significant medical history and has been taking only acetaminophen for the pain.

Examination reveals that the injured finger has good capillary refill, 2-point discrimination is intact at 5 mm, and the other fingers on his right hand have no deformities and a normal range of motion. On the injured finger, however, the DIP joint is swollen and tender; it cannot be fully extended (FiGURE 3).

WHAT'S YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

B. Distal tuft fracture.

C. Mallet finger.

D. Finger sprain.

E. Trigger finger.

Answer: The basketball player has mallet finger (C).

Mallet finger typically occurs on the dominant hand. The key physical finding is that the joint is “stuck” in flexion, which is evident during an exam and on x-ray. Although the DIP joint may be passively fully extended, the patient with mallet finger is unable to actively extend it.

Mallet injuries, which are common in sports and associated with minor trauma, are typically caused by sudden forced flexion of the DIP joint during active extension of the finger. This can either stretch or tear the extensor tendon or lead to avulsion of the tendon insertion from the dorsum of the distal phalanx, with or without a fragment of bone. The injury is called a “soft” mallet finger when there is no bone involvement and a “bony” mallet finger when an avulsion is present, like the one that is evident on the FIGURE 3 x-ray (see arrow).

On clinical examination, the finger may or may not have an obvious deformity; similarly, you won’t always see bruising, swelling, or tenderness over the DIP joint.6 The work-up should include posterior/anterior, oblique, and lateral x-rays, followed by an examination of the soft tissue and a range-of-motion evaluation of the metacarpophalangeal and PIP joints. In acute injuries, tenderness is elicited with palpation over the dorsal aspect of the DIP joint. Although most patients develop an extensor lag at the DIP joint immediately after injury, the deformity may be delayed by a few hours or even days.6,7

Nonsurgical management is the standard of care for most mallet injuries, including mallet fractures involving less than one-third of the articular surface with no associated DIP joint subluxation.7

If there is no displacement, round-the-clock splinting to keep the joint in extension for a minimum of 6 weeks is indicated, followed by 2 to 3 weeks of nighttime splinting. It is important that the splinting allow for complete extension of the DIP joint but flexion of the PIP joint. Keeping the PIP in extension for prolonged periods can lead to permanent stiffness of the joint, while failure to provide any immobilization may lead to permanent deformity.

Surgery is indicated for a fracture fragment involving >30% of the joint surface (as demonstrated in the radiograph), volar subluxation, or a swan neck deformity—and when conservative therapy fails.7

CASE 4 An 18-year-old high school football player presents with pain and swelling at the tip of his right ring finger from an injury that occurred a week ago. When the player he was trying to tackle broke away, the patient says, he immediately felt pain and a “pop” in the finger.

The DIP joint of his right ring finger is swollen (FIGURE 4), but appears normal otherwise. When you isolate the joint, however, the patient is unable to flex it. You can palpate a stump on the volar surface of the finger.

What’s your next step?

B. Treat with splinting, RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

C. Order an ultrasound of the finger and palm.

D. Order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hand.

Answer: Order an ultrasound of the football player’s finger and palm (C).

This patient has Jersey finger, caused by a traumatic avulsion of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) from the distal phalanx and diagnosed based on the mechanism of injury and the patient’s inability to flex the DIP joint. The injury often does not show on x-rays, and the diagnosis may be missed for several weeks.

Jersey finger usually happens in sports like football or rugby, where players tackle each other, and involves forced, passive extension of the DIP joint at a time of active flexion. Management of Jersey finger starts with splinting, with both the DIP and PIP in slight flexion. Surgical reattachment of the flexor tendon is needed, with best results when it is done within 7 to 10 days of injury.4

You may be able to palpate the tendon stump in the palm or along the digit; bony avulsions can be trapped at the flexor sheath. Soft tissue swelling can be misleading, however, and the point of maximal tenderness is not an accurate means of identifying the avulsed tendon stump.8

Ultrasound is effective in differentiating between a partial and full thickness rupture and in localizing the distal tendon stump.8 MRI is usually reserved for precise evaluation of the tendon edges, to aid in operative planning. If the tendon is retracted to the palm, scarring may be irreversible because of the lack of blood supply.

Athletes typically return to play 12 weeks after injury, starting with protected activity and progressing to full gripping/grasping. Physical therapy and/or occupational therapy will be needed after the surgical wound has healed.

CASE 5 A 40-year-old construction worker who smashed his left index finger with a hammer one day ago presents with severe pain in his fingertip, which he is unable to move. On examination, you find that the distal finger is swollen and there is extensive ecchymosis and swelling underneath the nail. The finger has normal sensation, but you are unable to see capillary refill due to a large hematoma.

X-rays (FIGURE 5) reveal a distal tuft fracture. The patient’s main concern is the pain, and he asks what you can do to relieve it.

What’s your next step?

B. Perform fenestration of the nail.

C. Refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

D. Order computed tomography of the hand.

Answer: Perform fenestration of the construction worker’s nail (B).

This patient has a closed fracture of the distal phalanx, called a tuft fracture, and a sub-ungual hematoma, evident from the x-ray and the physical presentation.

Subungual hematoma requires fenestration with a needle to create small holes in the nail. If the nail bed is lacerated, the nail is removed and the injured nail bed repaired with sutures.

Tuft fractures sometimes require reduction. More often, they are stable and minimally displaced and can be managed conservatively, with splinting with a padded aluminum splint or a fingertip guard (Stax splint) for 3 to 4 weeks. Antibiotics are not indicated unless there is suspicion of an overlying or secondary infection. Referral to a hand surgeon is required for severe crush injuries, avulsion of the nail matrix, and open fractures of the distal phalanx.5,6

1. Hogan CJ, Ruland RT. High-pressure injection injuries to the upper extremity: a review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:503-511.

2. Gonzalez R, Kasdan ML. High pressure injection injuries of the hand. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2006;5:407-411.

3. Freiberg A. Management of proximal interphalangeal joint injuries. Can J Plast Surg. 2007;15:199-203.

4. Perron AD, Brady WJ, Keats TE, et al. Orthopedic pitfalls in the emergency department: closed tendon injuries of the hand. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:76-80.

5. Oetgen ME, Dodds SD. Non-operative treatment of common finger injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskel Med. 2008;1:97-102.

6. Anderson D. Mallet finger. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:91-92.

7. Smit JM, Beets MR. Treatment options for mallet finger: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1624-1629.

8. Goodson A, Morgan M. Current management of Jersey finger in rugby players: cases series and literature review. Hand Surg. 2010;15:103-107.

Some finger injuries require little more than icing; others are more serious, often emergent, conditions with outcomes that are dependent on an accurate diagnosis and rapid initiation of treatment.

The 5 cases that follow describe injuries with varying degrees of severity. Read each case and select the multiple-choice answer you think is most appropriate. Then read on to find out if you were right—and to learn more about the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment for each type of injury.

CASE 1 A 45-year-old auto body worker walks into your office at 5:30 pm, just as your staff is closing up for the day. A few hours ago, he reports, he was spray-painting a car with a paint gun when he felt a sudden pain in his right index finger. His immediate thought was that he had torn something, but the pain quickly subsided. So he continued to work—until about 45 minutes ago, when the pain became so intense that he knew he needed medical care right away.

Examination reveals redness and increased skin temperature on the radial palmar side of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint of the index finger. Two-point discrimination is decreased to 10 mm, vs 5 mm on the same finger of the opposite hand. The patient can flex his PIP and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints but complains of pain and stiffness. You obtain x-rays of the injured

finger (FIGURE 1).

WHAT'S YOUR NEXT STEP?

B. Update the patient’s tetanus immunization and start him on a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

C. Put a dorsal splint on the injured finger in the “safe hand” position and schedule a return visit in one week.

D. “Buddy tape” the index and long fingers and refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

Answer: Send the auto-body worker to the nearest ED and call ahead (A).

This patient sustained a high-pressure injection injury to the PIP joint of his right index finger. The patient’s description of how the injury occurred suggested this, and the radiograph confirmed it by showing some paint under the skin (See arrow, FIGURE 1). Such injuries occur when a high pressure (typically from a hose) forces air or a substance—eg, diesel fuel, paint, or solvent—through the skin into the finger.

Although high-pressure injection injury often has a benign presentation, it is actually a medical emergency. If aggressive surgical debridement does not occur within a 6-hour window, the patient runs a high risk for amputation of the digit.1 A hand surgeon should be contacted as soon as possible.

The severity of the injury varies, depending on the amount of pressure (amputation rates are as high as 43% when the pressure per square inch >1000), the type of material injected (diesel fuel is the most toxic), and the location.1,2

Instruct the patient to remove any jewelry, such as a wedding band or watch, on the affected hand or wrist, and to keep the hand elevated. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started right away, and a tetanus booster given, if needed. Do not apply heat or use local anesthesia, as both can increase the swelling.2

CASE 2 A 17-year-old cheerleader comes to see you on Monday afternoon, after injuring her left pinky during a Friday night game. The patient, who is right-handed, points to the left PIP joint when you ask where it hurts, and tells you that the finger is stiff. She has been icing it since the injury occurred, to make sure she is ready to cheer by next weekend.

The injury occurred when she was spotting another cheerleader during a routine, the patient reports, adding that the pinky was “dislocated.” The coach “popped” it back in place and buddy-taped the injured finger to her ring finger.

The patient is able to flex and extend the DIP joint on the pinky when the PIP joint is stabilized. She can also flex the PIP joint unassisted, but has difficulty extending it. The digit demonstrates slight flexion of the PIP joint. You note tenderness over both collateral ligaments and the dorsum of the PIP joint, but not over the volar aspect of the injured finger, and order x-rays (FIGURE 2).

WHAT'S YOUR NEXT STEP?

B. Refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

C. Apply an extension block splint so the patient can flex the finger but not extend it, and schedule a follow-up appointment in one to 2 weeks.

D. Apply an aluminum dorsal splint, allowing the DIP joint to be flexed and keeping the PIP joint in full extension for 4 weeks.

Answer: Refer the cheerleader to a hand surgeon (B).

This patient has a rupture of the central extensor tendon of the pinky finger at the PIP joint. The mechanism of injury and her inability to completely extend the injured finger at the PIP joint alert you to this type of injury. An x-ray may sometimes be normal but in this case, it shows the flexion of the PIP joint. Surgical repair of the rupture should be scheduled without delay.3

Most injuries at this joint occur from forced extension, not flexion, and result in a volar plate rupture.4 If swelling and pain make evaluation of an acute dislocation injury difficult, splinting in the “safe hand” position for 72 hours while icing the injured finger will make it possible to do a more detailed follow-up exam.3

Extended periods of splinting can make the PIP joint very stiff, however—and harder to treat than the original injury.5 If the rupture of the central extensor tendon is undetected or simply not treated, a Boutonniere deformity, in which the PIP joint is flexed and the DIP joint is hyperextended, is the likely result.3

CASE 3 A 24-year-old man “jammed” his right ring finger while trying to catch a ball that was passed to him during a pick-up basketball game. He has rested and iced the finger for a couple of days, but it’s still painful and hard to move. He has no significant medical history and has been taking only acetaminophen for the pain.

Examination reveals that the injured finger has good capillary refill, 2-point discrimination is intact at 5 mm, and the other fingers on his right hand have no deformities and a normal range of motion. On the injured finger, however, the DIP joint is swollen and tender; it cannot be fully extended (FiGURE 3).

WHAT'S YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

B. Distal tuft fracture.

C. Mallet finger.

D. Finger sprain.

E. Trigger finger.

Answer: The basketball player has mallet finger (C).

Mallet finger typically occurs on the dominant hand. The key physical finding is that the joint is “stuck” in flexion, which is evident during an exam and on x-ray. Although the DIP joint may be passively fully extended, the patient with mallet finger is unable to actively extend it.

Mallet injuries, which are common in sports and associated with minor trauma, are typically caused by sudden forced flexion of the DIP joint during active extension of the finger. This can either stretch or tear the extensor tendon or lead to avulsion of the tendon insertion from the dorsum of the distal phalanx, with or without a fragment of bone. The injury is called a “soft” mallet finger when there is no bone involvement and a “bony” mallet finger when an avulsion is present, like the one that is evident on the FIGURE 3 x-ray (see arrow).

On clinical examination, the finger may or may not have an obvious deformity; similarly, you won’t always see bruising, swelling, or tenderness over the DIP joint.6 The work-up should include posterior/anterior, oblique, and lateral x-rays, followed by an examination of the soft tissue and a range-of-motion evaluation of the metacarpophalangeal and PIP joints. In acute injuries, tenderness is elicited with palpation over the dorsal aspect of the DIP joint. Although most patients develop an extensor lag at the DIP joint immediately after injury, the deformity may be delayed by a few hours or even days.6,7

Nonsurgical management is the standard of care for most mallet injuries, including mallet fractures involving less than one-third of the articular surface with no associated DIP joint subluxation.7

If there is no displacement, round-the-clock splinting to keep the joint in extension for a minimum of 6 weeks is indicated, followed by 2 to 3 weeks of nighttime splinting. It is important that the splinting allow for complete extension of the DIP joint but flexion of the PIP joint. Keeping the PIP in extension for prolonged periods can lead to permanent stiffness of the joint, while failure to provide any immobilization may lead to permanent deformity.

Surgery is indicated for a fracture fragment involving >30% of the joint surface (as demonstrated in the radiograph), volar subluxation, or a swan neck deformity—and when conservative therapy fails.7

CASE 4 An 18-year-old high school football player presents with pain and swelling at the tip of his right ring finger from an injury that occurred a week ago. When the player he was trying to tackle broke away, the patient says, he immediately felt pain and a “pop” in the finger.

The DIP joint of his right ring finger is swollen (FIGURE 4), but appears normal otherwise. When you isolate the joint, however, the patient is unable to flex it. You can palpate a stump on the volar surface of the finger.

What’s your next step?

B. Treat with splinting, RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

C. Order an ultrasound of the finger and palm.

D. Order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hand.

Answer: Order an ultrasound of the football player’s finger and palm (C).

This patient has Jersey finger, caused by a traumatic avulsion of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) from the distal phalanx and diagnosed based on the mechanism of injury and the patient’s inability to flex the DIP joint. The injury often does not show on x-rays, and the diagnosis may be missed for several weeks.

Jersey finger usually happens in sports like football or rugby, where players tackle each other, and involves forced, passive extension of the DIP joint at a time of active flexion. Management of Jersey finger starts with splinting, with both the DIP and PIP in slight flexion. Surgical reattachment of the flexor tendon is needed, with best results when it is done within 7 to 10 days of injury.4

You may be able to palpate the tendon stump in the palm or along the digit; bony avulsions can be trapped at the flexor sheath. Soft tissue swelling can be misleading, however, and the point of maximal tenderness is not an accurate means of identifying the avulsed tendon stump.8

Ultrasound is effective in differentiating between a partial and full thickness rupture and in localizing the distal tendon stump.8 MRI is usually reserved for precise evaluation of the tendon edges, to aid in operative planning. If the tendon is retracted to the palm, scarring may be irreversible because of the lack of blood supply.

Athletes typically return to play 12 weeks after injury, starting with protected activity and progressing to full gripping/grasping. Physical therapy and/or occupational therapy will be needed after the surgical wound has healed.

CASE 5 A 40-year-old construction worker who smashed his left index finger with a hammer one day ago presents with severe pain in his fingertip, which he is unable to move. On examination, you find that the distal finger is swollen and there is extensive ecchymosis and swelling underneath the nail. The finger has normal sensation, but you are unable to see capillary refill due to a large hematoma.

X-rays (FIGURE 5) reveal a distal tuft fracture. The patient’s main concern is the pain, and he asks what you can do to relieve it.

What’s your next step?

B. Perform fenestration of the nail.

C. Refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

D. Order computed tomography of the hand.

Answer: Perform fenestration of the construction worker’s nail (B).

This patient has a closed fracture of the distal phalanx, called a tuft fracture, and a sub-ungual hematoma, evident from the x-ray and the physical presentation.

Subungual hematoma requires fenestration with a needle to create small holes in the nail. If the nail bed is lacerated, the nail is removed and the injured nail bed repaired with sutures.

Tuft fractures sometimes require reduction. More often, they are stable and minimally displaced and can be managed conservatively, with splinting with a padded aluminum splint or a fingertip guard (Stax splint) for 3 to 4 weeks. Antibiotics are not indicated unless there is suspicion of an overlying or secondary infection. Referral to a hand surgeon is required for severe crush injuries, avulsion of the nail matrix, and open fractures of the distal phalanx.5,6

Some finger injuries require little more than icing; others are more serious, often emergent, conditions with outcomes that are dependent on an accurate diagnosis and rapid initiation of treatment.

The 5 cases that follow describe injuries with varying degrees of severity. Read each case and select the multiple-choice answer you think is most appropriate. Then read on to find out if you were right—and to learn more about the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment for each type of injury.

CASE 1 A 45-year-old auto body worker walks into your office at 5:30 pm, just as your staff is closing up for the day. A few hours ago, he reports, he was spray-painting a car with a paint gun when he felt a sudden pain in his right index finger. His immediate thought was that he had torn something, but the pain quickly subsided. So he continued to work—until about 45 minutes ago, when the pain became so intense that he knew he needed medical care right away.

Examination reveals redness and increased skin temperature on the radial palmar side of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint of the index finger. Two-point discrimination is decreased to 10 mm, vs 5 mm on the same finger of the opposite hand. The patient can flex his PIP and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints but complains of pain and stiffness. You obtain x-rays of the injured

finger (FIGURE 1).

WHAT'S YOUR NEXT STEP?

B. Update the patient’s tetanus immunization and start him on a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

C. Put a dorsal splint on the injured finger in the “safe hand” position and schedule a return visit in one week.

D. “Buddy tape” the index and long fingers and refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

Answer: Send the auto-body worker to the nearest ED and call ahead (A).

This patient sustained a high-pressure injection injury to the PIP joint of his right index finger. The patient’s description of how the injury occurred suggested this, and the radiograph confirmed it by showing some paint under the skin (See arrow, FIGURE 1). Such injuries occur when a high pressure (typically from a hose) forces air or a substance—eg, diesel fuel, paint, or solvent—through the skin into the finger.

Although high-pressure injection injury often has a benign presentation, it is actually a medical emergency. If aggressive surgical debridement does not occur within a 6-hour window, the patient runs a high risk for amputation of the digit.1 A hand surgeon should be contacted as soon as possible.

The severity of the injury varies, depending on the amount of pressure (amputation rates are as high as 43% when the pressure per square inch >1000), the type of material injected (diesel fuel is the most toxic), and the location.1,2

Instruct the patient to remove any jewelry, such as a wedding band or watch, on the affected hand or wrist, and to keep the hand elevated. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started right away, and a tetanus booster given, if needed. Do not apply heat or use local anesthesia, as both can increase the swelling.2

CASE 2 A 17-year-old cheerleader comes to see you on Monday afternoon, after injuring her left pinky during a Friday night game. The patient, who is right-handed, points to the left PIP joint when you ask where it hurts, and tells you that the finger is stiff. She has been icing it since the injury occurred, to make sure she is ready to cheer by next weekend.

The injury occurred when she was spotting another cheerleader during a routine, the patient reports, adding that the pinky was “dislocated.” The coach “popped” it back in place and buddy-taped the injured finger to her ring finger.

The patient is able to flex and extend the DIP joint on the pinky when the PIP joint is stabilized. She can also flex the PIP joint unassisted, but has difficulty extending it. The digit demonstrates slight flexion of the PIP joint. You note tenderness over both collateral ligaments and the dorsum of the PIP joint, but not over the volar aspect of the injured finger, and order x-rays (FIGURE 2).

WHAT'S YOUR NEXT STEP?

B. Refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

C. Apply an extension block splint so the patient can flex the finger but not extend it, and schedule a follow-up appointment in one to 2 weeks.

D. Apply an aluminum dorsal splint, allowing the DIP joint to be flexed and keeping the PIP joint in full extension for 4 weeks.

Answer: Refer the cheerleader to a hand surgeon (B).

This patient has a rupture of the central extensor tendon of the pinky finger at the PIP joint. The mechanism of injury and her inability to completely extend the injured finger at the PIP joint alert you to this type of injury. An x-ray may sometimes be normal but in this case, it shows the flexion of the PIP joint. Surgical repair of the rupture should be scheduled without delay.3

Most injuries at this joint occur from forced extension, not flexion, and result in a volar plate rupture.4 If swelling and pain make evaluation of an acute dislocation injury difficult, splinting in the “safe hand” position for 72 hours while icing the injured finger will make it possible to do a more detailed follow-up exam.3

Extended periods of splinting can make the PIP joint very stiff, however—and harder to treat than the original injury.5 If the rupture of the central extensor tendon is undetected or simply not treated, a Boutonniere deformity, in which the PIP joint is flexed and the DIP joint is hyperextended, is the likely result.3

CASE 3 A 24-year-old man “jammed” his right ring finger while trying to catch a ball that was passed to him during a pick-up basketball game. He has rested and iced the finger for a couple of days, but it’s still painful and hard to move. He has no significant medical history and has been taking only acetaminophen for the pain.

Examination reveals that the injured finger has good capillary refill, 2-point discrimination is intact at 5 mm, and the other fingers on his right hand have no deformities and a normal range of motion. On the injured finger, however, the DIP joint is swollen and tender; it cannot be fully extended (FiGURE 3).

WHAT'S YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

B. Distal tuft fracture.

C. Mallet finger.

D. Finger sprain.

E. Trigger finger.

Answer: The basketball player has mallet finger (C).

Mallet finger typically occurs on the dominant hand. The key physical finding is that the joint is “stuck” in flexion, which is evident during an exam and on x-ray. Although the DIP joint may be passively fully extended, the patient with mallet finger is unable to actively extend it.

Mallet injuries, which are common in sports and associated with minor trauma, are typically caused by sudden forced flexion of the DIP joint during active extension of the finger. This can either stretch or tear the extensor tendon or lead to avulsion of the tendon insertion from the dorsum of the distal phalanx, with or without a fragment of bone. The injury is called a “soft” mallet finger when there is no bone involvement and a “bony” mallet finger when an avulsion is present, like the one that is evident on the FIGURE 3 x-ray (see arrow).

On clinical examination, the finger may or may not have an obvious deformity; similarly, you won’t always see bruising, swelling, or tenderness over the DIP joint.6 The work-up should include posterior/anterior, oblique, and lateral x-rays, followed by an examination of the soft tissue and a range-of-motion evaluation of the metacarpophalangeal and PIP joints. In acute injuries, tenderness is elicited with palpation over the dorsal aspect of the DIP joint. Although most patients develop an extensor lag at the DIP joint immediately after injury, the deformity may be delayed by a few hours or even days.6,7

Nonsurgical management is the standard of care for most mallet injuries, including mallet fractures involving less than one-third of the articular surface with no associated DIP joint subluxation.7

If there is no displacement, round-the-clock splinting to keep the joint in extension for a minimum of 6 weeks is indicated, followed by 2 to 3 weeks of nighttime splinting. It is important that the splinting allow for complete extension of the DIP joint but flexion of the PIP joint. Keeping the PIP in extension for prolonged periods can lead to permanent stiffness of the joint, while failure to provide any immobilization may lead to permanent deformity.

Surgery is indicated for a fracture fragment involving >30% of the joint surface (as demonstrated in the radiograph), volar subluxation, or a swan neck deformity—and when conservative therapy fails.7

CASE 4 An 18-year-old high school football player presents with pain and swelling at the tip of his right ring finger from an injury that occurred a week ago. When the player he was trying to tackle broke away, the patient says, he immediately felt pain and a “pop” in the finger.

The DIP joint of his right ring finger is swollen (FIGURE 4), but appears normal otherwise. When you isolate the joint, however, the patient is unable to flex it. You can palpate a stump on the volar surface of the finger.

What’s your next step?

B. Treat with splinting, RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

C. Order an ultrasound of the finger and palm.

D. Order magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hand.

Answer: Order an ultrasound of the football player’s finger and palm (C).

This patient has Jersey finger, caused by a traumatic avulsion of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) from the distal phalanx and diagnosed based on the mechanism of injury and the patient’s inability to flex the DIP joint. The injury often does not show on x-rays, and the diagnosis may be missed for several weeks.

Jersey finger usually happens in sports like football or rugby, where players tackle each other, and involves forced, passive extension of the DIP joint at a time of active flexion. Management of Jersey finger starts with splinting, with both the DIP and PIP in slight flexion. Surgical reattachment of the flexor tendon is needed, with best results when it is done within 7 to 10 days of injury.4

You may be able to palpate the tendon stump in the palm or along the digit; bony avulsions can be trapped at the flexor sheath. Soft tissue swelling can be misleading, however, and the point of maximal tenderness is not an accurate means of identifying the avulsed tendon stump.8

Ultrasound is effective in differentiating between a partial and full thickness rupture and in localizing the distal tendon stump.8 MRI is usually reserved for precise evaluation of the tendon edges, to aid in operative planning. If the tendon is retracted to the palm, scarring may be irreversible because of the lack of blood supply.

Athletes typically return to play 12 weeks after injury, starting with protected activity and progressing to full gripping/grasping. Physical therapy and/or occupational therapy will be needed after the surgical wound has healed.

CASE 5 A 40-year-old construction worker who smashed his left index finger with a hammer one day ago presents with severe pain in his fingertip, which he is unable to move. On examination, you find that the distal finger is swollen and there is extensive ecchymosis and swelling underneath the nail. The finger has normal sensation, but you are unable to see capillary refill due to a large hematoma.

X-rays (FIGURE 5) reveal a distal tuft fracture. The patient’s main concern is the pain, and he asks what you can do to relieve it.

What’s your next step?

B. Perform fenestration of the nail.

C. Refer the patient to a hand surgeon.

D. Order computed tomography of the hand.

Answer: Perform fenestration of the construction worker’s nail (B).

This patient has a closed fracture of the distal phalanx, called a tuft fracture, and a sub-ungual hematoma, evident from the x-ray and the physical presentation.

Subungual hematoma requires fenestration with a needle to create small holes in the nail. If the nail bed is lacerated, the nail is removed and the injured nail bed repaired with sutures.

Tuft fractures sometimes require reduction. More often, they are stable and minimally displaced and can be managed conservatively, with splinting with a padded aluminum splint or a fingertip guard (Stax splint) for 3 to 4 weeks. Antibiotics are not indicated unless there is suspicion of an overlying or secondary infection. Referral to a hand surgeon is required for severe crush injuries, avulsion of the nail matrix, and open fractures of the distal phalanx.5,6

1. Hogan CJ, Ruland RT. High-pressure injection injuries to the upper extremity: a review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:503-511.

2. Gonzalez R, Kasdan ML. High pressure injection injuries of the hand. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2006;5:407-411.

3. Freiberg A. Management of proximal interphalangeal joint injuries. Can J Plast Surg. 2007;15:199-203.

4. Perron AD, Brady WJ, Keats TE, et al. Orthopedic pitfalls in the emergency department: closed tendon injuries of the hand. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:76-80.

5. Oetgen ME, Dodds SD. Non-operative treatment of common finger injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskel Med. 2008;1:97-102.

6. Anderson D. Mallet finger. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:91-92.

7. Smit JM, Beets MR. Treatment options for mallet finger: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1624-1629.

8. Goodson A, Morgan M. Current management of Jersey finger in rugby players: cases series and literature review. Hand Surg. 2010;15:103-107.

1. Hogan CJ, Ruland RT. High-pressure injection injuries to the upper extremity: a review of the literature. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:503-511.

2. Gonzalez R, Kasdan ML. High pressure injection injuries of the hand. Clin Occup Environ Med. 2006;5:407-411.

3. Freiberg A. Management of proximal interphalangeal joint injuries. Can J Plast Surg. 2007;15:199-203.

4. Perron AD, Brady WJ, Keats TE, et al. Orthopedic pitfalls in the emergency department: closed tendon injuries of the hand. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:76-80.

5. Oetgen ME, Dodds SD. Non-operative treatment of common finger injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskel Med. 2008;1:97-102.

6. Anderson D. Mallet finger. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:91-92.

7. Smit JM, Beets MR. Treatment options for mallet finger: a review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1624-1629.

8. Goodson A, Morgan M. Current management of Jersey finger in rugby players: cases series and literature review. Hand Surg. 2010;15:103-107.

Cartilage Defect of Lunate Facet of Distal Radius After Fracture Treated With Osteochondral Autograft From Knee

Irreducible Longitudinal Distraction-Dislocation of the Hallux Interphalangeal Joint

Disk Degeneration in Lumbar Spine Precedes Osteoarthritic Changes in Hip

Pituitary tumor size not definitive for Cushing's

SAN FRANCISCO – The size of a pituitary tumor on magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome can’t differentiate between etiologies, but combining that information with biochemical test results could help avoid costly and difficult inferior petrosal sinus sampling in some patients, a study of 131 cases suggests.

If MRI shows a pituitary tumor larger than 6 mm in size, the finding is 40% sensitive and 96% specific for a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease as the cause of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, and additional information from biochemical testing may help further differentiate this from ectopic ACTH secretion, Dr. Divya Yogi-Morren and her associates reported at the Endocrine Society’s Annual Meeting.

Pituitary tumors were seen on MRI in 6 of 26 patients with ectopic ACTH secretion (23%) and 73 of 105 patients with Cushing’s disease (69%), with mean measurements of 4.5 mm in the ectopic ACTH secretion group and 8 mm in the Cushing’s disease group. All but one tumor in the ectopic ACTH secretion group were 6 mm or smaller in diameter, but one was 14 mm.

Because pituitary "incidentalomas" as large as 14 mm can be seen in patients with ectopic ACTH secretion, the presence of a pituitary tumor can’t definitively discriminate between ectopic ACTH secretion and Cushing’s disease, said Dr. Yogi-Morren, a fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

That finding contradicts part of a 2003 consensus statement that said the presence of a focal pituitary lesion larger than 6 mm on MRI could provide a definitive diagnosis of Cushing’s disease, with no further evaluation needed in patients who have a classic clinical presentation and dynamic biochemical testing results that are compatible with a pituitary etiology (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:5593-602). The 6-mm cutoff, said Dr. Yogi-Morren, came from an earlier study reporting that 10% of 100 normal, healthy adults had focal pituitary abnormalities on MRI ranging from 3 to 6 mm in diameter that were consistent with a diagnosis of asymptomatic pituitary adenomas (Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;120:817-20).

A traditional workup of a patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome might include a clinical history, biochemical testing, neuroimaging, and an inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS). Biochemical testing typically includes tests for hypokalemia, measurement of cortisol and ACTH levels, a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, and a corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation test. Although IPSS is the gold standard for differentiating between the two etiologies, it is expensive and technically difficult, especially in institutions that don’t regularly do the procedure, so it would be desirable to avoid IPSS if it’s not needed in a subset of patients, Dr. Yogi-Morren said.

The investigators reviewed charts from two centers (the Cleveland Clinic and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston) for patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome seen during 2000-2012.

ACTH levels were significantly different between groups, averaging 162 pg/mL (range, 58-671 pg/mL) in patients with ectopic ACTH secretion, compared with a mean 71 pg/mL in patients with Cushing’s disease (range, 16-209 pg/mL), she reported. Although there was some overlap between groups in the range of ACTH levels, all patients with an ACTH level higher than 210 pg/mL had ectopic ACTH secretion.

Median serum potassium levels at baseline were 2.9 mmol/L in the ectopic ACTH secretion group and 3.8 mmol/L in the Cushing’s disease group, a significant difference. Again, there was some overlap between groups in the range of potassium levels, but all patients with a baseline potassium level lower than 2.7 mmol/L had ectopic ACTH secretion, she said.

Among patients who underwent a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, cortisol levels decreased by less than 50% in 88% of patients with ectopic ACTH secretion and in 26% of patients with Cushing’s disease.

Most patients did not undergo a standardized, formal CRH stimulation test, so investigators extracted the ACTH response to CRH in peripheral plasma during the IPSS test. As expected, they found a significantly higher percent increase in ACTH in response to CRH during IPSS in the Cushing’s disease group, ranging up to more than a 1,000% increase. In the ectopic ACTH secretion group, 40% of patients did have an ACTH increase greater than 50%, ranging as high as a 200%-300% increase in ACTH in a couple of patients.

"Although there was some overlap in the biochemical testing, it is possible that it provides some additional proof to differentiate between ectopic ACTH secretion and Cushing’s disease," Dr. Yogi-Morren said.

In the ectopic ACTH secretion group, the source of the secretion remained occult in seven patients. The most common identifiable cause was a bronchial carcinoid tumor, in six patients. Three patients each had small cell lung cancer, a thymic carcinoid tumor, or a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. One patient each had a bladder neuroendocrine tumor, ovarian endometrioid cancer, medullary thyroid cancer, or a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor from an unknown primary cancer.

The ectopic ACTH secretion group had a median age of 41 years and was 63% female. The Cushing’s disease group had a median age of 46 years and was 76% female.

Dr. Yogi-Morren reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – The size of a pituitary tumor on magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome can’t differentiate between etiologies, but combining that information with biochemical test results could help avoid costly and difficult inferior petrosal sinus sampling in some patients, a study of 131 cases suggests.

If MRI shows a pituitary tumor larger than 6 mm in size, the finding is 40% sensitive and 96% specific for a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease as the cause of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, and additional information from biochemical testing may help further differentiate this from ectopic ACTH secretion, Dr. Divya Yogi-Morren and her associates reported at the Endocrine Society’s Annual Meeting.

Pituitary tumors were seen on MRI in 6 of 26 patients with ectopic ACTH secretion (23%) and 73 of 105 patients with Cushing’s disease (69%), with mean measurements of 4.5 mm in the ectopic ACTH secretion group and 8 mm in the Cushing’s disease group. All but one tumor in the ectopic ACTH secretion group were 6 mm or smaller in diameter, but one was 14 mm.

Because pituitary "incidentalomas" as large as 14 mm can be seen in patients with ectopic ACTH secretion, the presence of a pituitary tumor can’t definitively discriminate between ectopic ACTH secretion and Cushing’s disease, said Dr. Yogi-Morren, a fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

That finding contradicts part of a 2003 consensus statement that said the presence of a focal pituitary lesion larger than 6 mm on MRI could provide a definitive diagnosis of Cushing’s disease, with no further evaluation needed in patients who have a classic clinical presentation and dynamic biochemical testing results that are compatible with a pituitary etiology (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:5593-602). The 6-mm cutoff, said Dr. Yogi-Morren, came from an earlier study reporting that 10% of 100 normal, healthy adults had focal pituitary abnormalities on MRI ranging from 3 to 6 mm in diameter that were consistent with a diagnosis of asymptomatic pituitary adenomas (Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;120:817-20).

A traditional workup of a patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome might include a clinical history, biochemical testing, neuroimaging, and an inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS). Biochemical testing typically includes tests for hypokalemia, measurement of cortisol and ACTH levels, a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, and a corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation test. Although IPSS is the gold standard for differentiating between the two etiologies, it is expensive and technically difficult, especially in institutions that don’t regularly do the procedure, so it would be desirable to avoid IPSS if it’s not needed in a subset of patients, Dr. Yogi-Morren said.

The investigators reviewed charts from two centers (the Cleveland Clinic and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston) for patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome seen during 2000-2012.

ACTH levels were significantly different between groups, averaging 162 pg/mL (range, 58-671 pg/mL) in patients with ectopic ACTH secretion, compared with a mean 71 pg/mL in patients with Cushing’s disease (range, 16-209 pg/mL), she reported. Although there was some overlap between groups in the range of ACTH levels, all patients with an ACTH level higher than 210 pg/mL had ectopic ACTH secretion.

Median serum potassium levels at baseline were 2.9 mmol/L in the ectopic ACTH secretion group and 3.8 mmol/L in the Cushing’s disease group, a significant difference. Again, there was some overlap between groups in the range of potassium levels, but all patients with a baseline potassium level lower than 2.7 mmol/L had ectopic ACTH secretion, she said.

Among patients who underwent a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, cortisol levels decreased by less than 50% in 88% of patients with ectopic ACTH secretion and in 26% of patients with Cushing’s disease.

Most patients did not undergo a standardized, formal CRH stimulation test, so investigators extracted the ACTH response to CRH in peripheral plasma during the IPSS test. As expected, they found a significantly higher percent increase in ACTH in response to CRH during IPSS in the Cushing’s disease group, ranging up to more than a 1,000% increase. In the ectopic ACTH secretion group, 40% of patients did have an ACTH increase greater than 50%, ranging as high as a 200%-300% increase in ACTH in a couple of patients.

"Although there was some overlap in the biochemical testing, it is possible that it provides some additional proof to differentiate between ectopic ACTH secretion and Cushing’s disease," Dr. Yogi-Morren said.

In the ectopic ACTH secretion group, the source of the secretion remained occult in seven patients. The most common identifiable cause was a bronchial carcinoid tumor, in six patients. Three patients each had small cell lung cancer, a thymic carcinoid tumor, or a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. One patient each had a bladder neuroendocrine tumor, ovarian endometrioid cancer, medullary thyroid cancer, or a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor from an unknown primary cancer.

The ectopic ACTH secretion group had a median age of 41 years and was 63% female. The Cushing’s disease group had a median age of 46 years and was 76% female.

Dr. Yogi-Morren reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

SAN FRANCISCO – The size of a pituitary tumor on magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome can’t differentiate between etiologies, but combining that information with biochemical test results could help avoid costly and difficult inferior petrosal sinus sampling in some patients, a study of 131 cases suggests.

If MRI shows a pituitary tumor larger than 6 mm in size, the finding is 40% sensitive and 96% specific for a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease as the cause of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, and additional information from biochemical testing may help further differentiate this from ectopic ACTH secretion, Dr. Divya Yogi-Morren and her associates reported at the Endocrine Society’s Annual Meeting.

Pituitary tumors were seen on MRI in 6 of 26 patients with ectopic ACTH secretion (23%) and 73 of 105 patients with Cushing’s disease (69%), with mean measurements of 4.5 mm in the ectopic ACTH secretion group and 8 mm in the Cushing’s disease group. All but one tumor in the ectopic ACTH secretion group were 6 mm or smaller in diameter, but one was 14 mm.

Because pituitary "incidentalomas" as large as 14 mm can be seen in patients with ectopic ACTH secretion, the presence of a pituitary tumor can’t definitively discriminate between ectopic ACTH secretion and Cushing’s disease, said Dr. Yogi-Morren, a fellow at the Cleveland Clinic.

That finding contradicts part of a 2003 consensus statement that said the presence of a focal pituitary lesion larger than 6 mm on MRI could provide a definitive diagnosis of Cushing’s disease, with no further evaluation needed in patients who have a classic clinical presentation and dynamic biochemical testing results that are compatible with a pituitary etiology (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;88:5593-602). The 6-mm cutoff, said Dr. Yogi-Morren, came from an earlier study reporting that 10% of 100 normal, healthy adults had focal pituitary abnormalities on MRI ranging from 3 to 6 mm in diameter that were consistent with a diagnosis of asymptomatic pituitary adenomas (Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;120:817-20).

A traditional workup of a patient with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome might include a clinical history, biochemical testing, neuroimaging, and an inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS). Biochemical testing typically includes tests for hypokalemia, measurement of cortisol and ACTH levels, a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, and a corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation test. Although IPSS is the gold standard for differentiating between the two etiologies, it is expensive and technically difficult, especially in institutions that don’t regularly do the procedure, so it would be desirable to avoid IPSS if it’s not needed in a subset of patients, Dr. Yogi-Morren said.

The investigators reviewed charts from two centers (the Cleveland Clinic and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston) for patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome seen during 2000-2012.

ACTH levels were significantly different between groups, averaging 162 pg/mL (range, 58-671 pg/mL) in patients with ectopic ACTH secretion, compared with a mean 71 pg/mL in patients with Cushing’s disease (range, 16-209 pg/mL), she reported. Although there was some overlap between groups in the range of ACTH levels, all patients with an ACTH level higher than 210 pg/mL had ectopic ACTH secretion.

Median serum potassium levels at baseline were 2.9 mmol/L in the ectopic ACTH secretion group and 3.8 mmol/L in the Cushing’s disease group, a significant difference. Again, there was some overlap between groups in the range of potassium levels, but all patients with a baseline potassium level lower than 2.7 mmol/L had ectopic ACTH secretion, she said.

Among patients who underwent a high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, cortisol levels decreased by less than 50% in 88% of patients with ectopic ACTH secretion and in 26% of patients with Cushing’s disease.

Most patients did not undergo a standardized, formal CRH stimulation test, so investigators extracted the ACTH response to CRH in peripheral plasma during the IPSS test. As expected, they found a significantly higher percent increase in ACTH in response to CRH during IPSS in the Cushing’s disease group, ranging up to more than a 1,000% increase. In the ectopic ACTH secretion group, 40% of patients did have an ACTH increase greater than 50%, ranging as high as a 200%-300% increase in ACTH in a couple of patients.

"Although there was some overlap in the biochemical testing, it is possible that it provides some additional proof to differentiate between ectopic ACTH secretion and Cushing’s disease," Dr. Yogi-Morren said.

In the ectopic ACTH secretion group, the source of the secretion remained occult in seven patients. The most common identifiable cause was a bronchial carcinoid tumor, in six patients. Three patients each had small cell lung cancer, a thymic carcinoid tumor, or a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. One patient each had a bladder neuroendocrine tumor, ovarian endometrioid cancer, medullary thyroid cancer, or a metastatic neuroendocrine tumor from an unknown primary cancer.

The ectopic ACTH secretion group had a median age of 41 years and was 63% female. The Cushing’s disease group had a median age of 46 years and was 76% female.

Dr. Yogi-Morren reported having no financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @sherryboschert

AT ENDO 2013

Major finding: A pituitary tumor larger than 6 mm on MRI was 40% sensitive and 96% specific for a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease as the cause of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome.

Data source: Retrospective study of 131 patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, 26 from ectopic ACTH secretion and 105 from Cushing’s disease.

Disclosures: Dr. Yogi-Morren reported having no financial disclosures.

Isolated Sciatic Nerve Entrapment by Ectopic Bone After Femoral Head Fracture-Dislocation

Nonfatal Air Embolism During Shoulder Arthroscopy

Deep Vein Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism After Spine Surgery: Incidence and Patient Risk Factors

Vitamin D: When it helps, when it harms

Vitamin D is the new wonder cure and preventive for all kinds of ailments and chronic diseases. Or so it would seem from the popular press and Internet.1

But what do we actually know about the health benefits of vitamin D? Should we be screening patients for vitamin D deficiency? How much vitamin D should our patients consume daily? This Practice Alert answers these questions.

Vitamin D basics

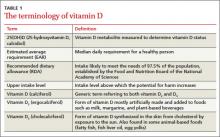

Vitamin D is synthesized in the skin from cholesterol through sun exposure (vitamin D3) and consumed in food fortified with vitamin D2, such as milk, yogurt, and orange juice, or food that contains vitamin D3 (fatty fish and eggs). Both forms of vitamin D are inactive until metabolized in the liver to 25(OH)D (TABLE 1), which is further metabolized in the kidney to the biologically active calcitriol. The 25(OH)D circulates in the blood with a vitamin D–binding protein and is the basis of measurement of serum vitamin D levels.

The terminology of vitamin D

The metabolic actions of calcitriol include regulation of calcium and phosphate levels and maintenance of bone health. It also has a role in regulating cell proliferation and immune system functions. These last 2 activities are not well understood; still, they have led to the hypothesis that vitamin D may help prevent cancer, autoimmune conditions, and cardiovascular disease. Promotion of calcitriol for these purposes has yet to be supported by well-controlled clinical trials.

One more source…Vitamin D can also be found in multivitamin preparations at various dosages and is sold as a single vitamin supplement—sometimes in megadoses of up to 50,000 international units (IU).

How much vitamin D is enough?

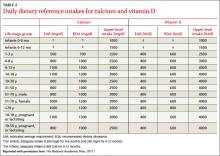

There is universal agreement that vitamin D and calcium are important for bone health. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently revised the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of vitamin D, by age (TABLE 2).2 The IOM calculated the newer RDAs under the assumption that, in the United States and Canada, little or no vitamin D is obtained from sun exposure, particularly given anticancer campaigns that stress sun avoidance. The IOM committee also expressed concern, however, about high levels of vitamin D intake that have not been linked to any proven benefits but have been linked to harms.2 Excess vitamin D from oral intake (not from sun exposure, which is subject to autoregulatory mechanisms) can cause vitamin D intoxication, hypercalcemia, and kidney stones.

Daily dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D

Recent systematic reviews and recommendations

The IOM reviewed the medical literature on the effects of vitamin D to prevent or treat cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, falls, and preeclampsia; and to boost immune response, neuropsychological function, physical performance, and reproductive outcomes. The panel found that the evidence for all of these effects is mixed and inconclusive, even though the media often report a beneficial effect.2

Several Cochrane systematic reviews have yielded similar results. One looked at overall mortality in adults and found that vitamin D3 seems to decrease mortality, but mostly in elderly women in institutions and dependent-care settings. Vitamin D2 had no effect on mortality. Vitamin D3 and calcium significantly increased the incidence of kidney stones.3Another review examined the effect of vitamin D on chronic pain and concluded that there were only low-quality observational studies insufficient for drawing conclusions.4

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released 2 recommendations related to vitamin D supplementation.5,6 It first recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation (800 IU daily) to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥65 years at increased risk for falls (described in a previous Practice Alert7). The second recommendation pertains to primary prevention of fractures and advises against daily supplementation with vitamin D and calcium at doses ≤400 IU and 1000 mg, respectively, for noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women. At these doses, supplementation with vitamin D and calcium does not prevent fractures but does cause kidney stones, with a number needed to harm of 273 over 7 years.6 The USPSTF concluded that the evidence is insufficient to assess the value of either vitamin D or calcium in men and premenopausal women at any dose, or daily supplementation with >400 IU of vitamin D3 and >1000 mg of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women.

What about screening for vitamin D deficiency?

The Endocrine Society recommends screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals at risk FAST TRACK. The USPSTF recommends vitamin D supplementation at 800 IU/d to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults >65 years at increased risk for falls. for deficiency—ie, those who have darkly pigmented skin, live in northern latitudes, or receive little exposure to sun. It does not recommend population screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals not at risk. It defines vitamin D deficiency as a 25(OH)D level <20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) and vitamin D insufficiency as a 25(OH)D level of 21 to 29 ng/mL (52.5-72.5 nmol/L).8

The IOM expresses concern about testing for vitamin D levels because there is no validated cutoff, and some labs report cutoffs above what the IOM considers a deficient level, leading to inflated numbers of those labeled as deficient.2 The USPSTF is about to weigh in on this issue. It has posted a draft research plan that will guide its evidence report and recommendation considerations.9

Take-home message

Information on the health benefits of vitamin D is difficult to sort out. Evidence for anything other than bone health and fall prevention is problematic. Consider vitamin D supplements along with calcium for the frail elderly at risk for falls10and for those who have osteoporosis. Screening for vitamin D deficiency is of questionable value and the USPSTF will be producing an evidence-based report on this topic, which should be available in about a year. The IOM RDA tables are available to guide dietary advice.

1. Vitamin D Council. Available at: http://www.vitamindcouncil.org/health-conditions. Accessed May 7, 2013.

2. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13050. Accessed June 3, 2013.

3. Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Whitfield K, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD007470.

4. Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, et al. Vitamin D for the treatment of chronic painful conditions in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD007771.

5. USPSTF. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/

uspstf/uspsfalls.htm. Accessed May 7, 2013.

6. USPSTF. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation to prevent fractures in adults. Available at: http://www.uspreventive

servicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsvitd.htm. Accessed May 7, 2013.

7. Campos-Outcalt D. The latest recommendations from the

USPSTF. J Fam Pract. 2013;62:249-252.

8. Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911-1930.

9. USPSTF. Draft research plan. Screening for vitamin D deficiency. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/

uspstf13/vitddefic/vitddeficdraftresplan.htm. Accessed May 7, 2013.

10. Avenell A, Gillespie WJ, Gillespie LD, et al. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures associated with involutional and post-menopausal osteoporosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD000227.

Vitamin D is the new wonder cure and preventive for all kinds of ailments and chronic diseases. Or so it would seem from the popular press and Internet.1

But what do we actually know about the health benefits of vitamin D? Should we be screening patients for vitamin D deficiency? How much vitamin D should our patients consume daily? This Practice Alert answers these questions.

Vitamin D basics

Vitamin D is synthesized in the skin from cholesterol through sun exposure (vitamin D3) and consumed in food fortified with vitamin D2, such as milk, yogurt, and orange juice, or food that contains vitamin D3 (fatty fish and eggs). Both forms of vitamin D are inactive until metabolized in the liver to 25(OH)D (TABLE 1), which is further metabolized in the kidney to the biologically active calcitriol. The 25(OH)D circulates in the blood with a vitamin D–binding protein and is the basis of measurement of serum vitamin D levels.

The terminology of vitamin D

The metabolic actions of calcitriol include regulation of calcium and phosphate levels and maintenance of bone health. It also has a role in regulating cell proliferation and immune system functions. These last 2 activities are not well understood; still, they have led to the hypothesis that vitamin D may help prevent cancer, autoimmune conditions, and cardiovascular disease. Promotion of calcitriol for these purposes has yet to be supported by well-controlled clinical trials.

One more source…Vitamin D can also be found in multivitamin preparations at various dosages and is sold as a single vitamin supplement—sometimes in megadoses of up to 50,000 international units (IU).

How much vitamin D is enough?

There is universal agreement that vitamin D and calcium are important for bone health. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently revised the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of vitamin D, by age (TABLE 2).2 The IOM calculated the newer RDAs under the assumption that, in the United States and Canada, little or no vitamin D is obtained from sun exposure, particularly given anticancer campaigns that stress sun avoidance. The IOM committee also expressed concern, however, about high levels of vitamin D intake that have not been linked to any proven benefits but have been linked to harms.2 Excess vitamin D from oral intake (not from sun exposure, which is subject to autoregulatory mechanisms) can cause vitamin D intoxication, hypercalcemia, and kidney stones.

Daily dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D

Recent systematic reviews and recommendations

The IOM reviewed the medical literature on the effects of vitamin D to prevent or treat cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, falls, and preeclampsia; and to boost immune response, neuropsychological function, physical performance, and reproductive outcomes. The panel found that the evidence for all of these effects is mixed and inconclusive, even though the media often report a beneficial effect.2

Several Cochrane systematic reviews have yielded similar results. One looked at overall mortality in adults and found that vitamin D3 seems to decrease mortality, but mostly in elderly women in institutions and dependent-care settings. Vitamin D2 had no effect on mortality. Vitamin D3 and calcium significantly increased the incidence of kidney stones.3Another review examined the effect of vitamin D on chronic pain and concluded that there were only low-quality observational studies insufficient for drawing conclusions.4

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released 2 recommendations related to vitamin D supplementation.5,6 It first recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation (800 IU daily) to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥65 years at increased risk for falls (described in a previous Practice Alert7). The second recommendation pertains to primary prevention of fractures and advises against daily supplementation with vitamin D and calcium at doses ≤400 IU and 1000 mg, respectively, for noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women. At these doses, supplementation with vitamin D and calcium does not prevent fractures but does cause kidney stones, with a number needed to harm of 273 over 7 years.6 The USPSTF concluded that the evidence is insufficient to assess the value of either vitamin D or calcium in men and premenopausal women at any dose, or daily supplementation with >400 IU of vitamin D3 and >1000 mg of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women.

What about screening for vitamin D deficiency?

The Endocrine Society recommends screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals at risk FAST TRACK. The USPSTF recommends vitamin D supplementation at 800 IU/d to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults >65 years at increased risk for falls. for deficiency—ie, those who have darkly pigmented skin, live in northern latitudes, or receive little exposure to sun. It does not recommend population screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals not at risk. It defines vitamin D deficiency as a 25(OH)D level <20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) and vitamin D insufficiency as a 25(OH)D level of 21 to 29 ng/mL (52.5-72.5 nmol/L).8

The IOM expresses concern about testing for vitamin D levels because there is no validated cutoff, and some labs report cutoffs above what the IOM considers a deficient level, leading to inflated numbers of those labeled as deficient.2 The USPSTF is about to weigh in on this issue. It has posted a draft research plan that will guide its evidence report and recommendation considerations.9

Take-home message

Information on the health benefits of vitamin D is difficult to sort out. Evidence for anything other than bone health and fall prevention is problematic. Consider vitamin D supplements along with calcium for the frail elderly at risk for falls10and for those who have osteoporosis. Screening for vitamin D deficiency is of questionable value and the USPSTF will be producing an evidence-based report on this topic, which should be available in about a year. The IOM RDA tables are available to guide dietary advice.

Vitamin D is the new wonder cure and preventive for all kinds of ailments and chronic diseases. Or so it would seem from the popular press and Internet.1

But what do we actually know about the health benefits of vitamin D? Should we be screening patients for vitamin D deficiency? How much vitamin D should our patients consume daily? This Practice Alert answers these questions.

Vitamin D basics

Vitamin D is synthesized in the skin from cholesterol through sun exposure (vitamin D3) and consumed in food fortified with vitamin D2, such as milk, yogurt, and orange juice, or food that contains vitamin D3 (fatty fish and eggs). Both forms of vitamin D are inactive until metabolized in the liver to 25(OH)D (TABLE 1), which is further metabolized in the kidney to the biologically active calcitriol. The 25(OH)D circulates in the blood with a vitamin D–binding protein and is the basis of measurement of serum vitamin D levels.

The terminology of vitamin D

The metabolic actions of calcitriol include regulation of calcium and phosphate levels and maintenance of bone health. It also has a role in regulating cell proliferation and immune system functions. These last 2 activities are not well understood; still, they have led to the hypothesis that vitamin D may help prevent cancer, autoimmune conditions, and cardiovascular disease. Promotion of calcitriol for these purposes has yet to be supported by well-controlled clinical trials.

One more source…Vitamin D can also be found in multivitamin preparations at various dosages and is sold as a single vitamin supplement—sometimes in megadoses of up to 50,000 international units (IU).

How much vitamin D is enough?

There is universal agreement that vitamin D and calcium are important for bone health. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recently revised the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) of vitamin D, by age (TABLE 2).2 The IOM calculated the newer RDAs under the assumption that, in the United States and Canada, little or no vitamin D is obtained from sun exposure, particularly given anticancer campaigns that stress sun avoidance. The IOM committee also expressed concern, however, about high levels of vitamin D intake that have not been linked to any proven benefits but have been linked to harms.2 Excess vitamin D from oral intake (not from sun exposure, which is subject to autoregulatory mechanisms) can cause vitamin D intoxication, hypercalcemia, and kidney stones.

Daily dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D

Recent systematic reviews and recommendations

The IOM reviewed the medical literature on the effects of vitamin D to prevent or treat cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, falls, and preeclampsia; and to boost immune response, neuropsychological function, physical performance, and reproductive outcomes. The panel found that the evidence for all of these effects is mixed and inconclusive, even though the media often report a beneficial effect.2

Several Cochrane systematic reviews have yielded similar results. One looked at overall mortality in adults and found that vitamin D3 seems to decrease mortality, but mostly in elderly women in institutions and dependent-care settings. Vitamin D2 had no effect on mortality. Vitamin D3 and calcium significantly increased the incidence of kidney stones.3Another review examined the effect of vitamin D on chronic pain and concluded that there were only low-quality observational studies insufficient for drawing conclusions.4

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released 2 recommendations related to vitamin D supplementation.5,6 It first recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation (800 IU daily) to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults ≥65 years at increased risk for falls (described in a previous Practice Alert7). The second recommendation pertains to primary prevention of fractures and advises against daily supplementation with vitamin D and calcium at doses ≤400 IU and 1000 mg, respectively, for noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women. At these doses, supplementation with vitamin D and calcium does not prevent fractures but does cause kidney stones, with a number needed to harm of 273 over 7 years.6 The USPSTF concluded that the evidence is insufficient to assess the value of either vitamin D or calcium in men and premenopausal women at any dose, or daily supplementation with >400 IU of vitamin D3 and >1000 mg of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women.

What about screening for vitamin D deficiency?

The Endocrine Society recommends screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals at risk FAST TRACK. The USPSTF recommends vitamin D supplementation at 800 IU/d to prevent falls in community-dwelling adults >65 years at increased risk for falls. for deficiency—ie, those who have darkly pigmented skin, live in northern latitudes, or receive little exposure to sun. It does not recommend population screening for vitamin D deficiency in individuals not at risk. It defines vitamin D deficiency as a 25(OH)D level <20 ng/mL (50 nmol/L) and vitamin D insufficiency as a 25(OH)D level of 21 to 29 ng/mL (52.5-72.5 nmol/L).8

The IOM expresses concern about testing for vitamin D levels because there is no validated cutoff, and some labs report cutoffs above what the IOM considers a deficient level, leading to inflated numbers of those labeled as deficient.2 The USPSTF is about to weigh in on this issue. It has posted a draft research plan that will guide its evidence report and recommendation considerations.9

Take-home message

Information on the health benefits of vitamin D is difficult to sort out. Evidence for anything other than bone health and fall prevention is problematic. Consider vitamin D supplements along with calcium for the frail elderly at risk for falls10and for those who have osteoporosis. Screening for vitamin D deficiency is of questionable value and the USPSTF will be producing an evidence-based report on this topic, which should be available in about a year. The IOM RDA tables are available to guide dietary advice.

1. Vitamin D Council. Available at: http://www.vitamindcouncil.org/health-conditions. Accessed May 7, 2013.