User login

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer in a socio-economically challenged population

Background Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) is associated with poor outcome, and clinical trials are imperative to address this. However, barriers to trial enrollment often exist, particularly in socio-economically challenged populations.

Objective To evaluate the outcome of socio-economically challenged patients who had LAPC, multiple comorbidities, and who were not enrolled on clinical trials, but who were treated with the best standard-of-care.

Methods We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 32 patients diagnosed as having LAPC who were referred to an urban cancer center between 2005 and 2010, analyzing the treatment and outcomes of 19 who underwent treatment at our center.

Results In all 26.3% of the analyzed patients had commercial insurance, 31.6% did not identify English as their preferred language, and 84.2% had 3 or more comorbidities. The median overall survival was 19.1 months, with estimated 1- and 2-year survivals of 60.8% and 36.5%, respectively. The median survival for patients receiving chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation was 26.6 months. Toxicities were controllable. Translation services were required by 26% and social services interventions by 84%. Survival analysis based on insurance coverage did not show a significant association with levels of reimbursement.

Limitations Retrospective study, small sample size, differences in chemotherapy types.

Conclusions These patients, representative of a diverse and socio-economically challenged community, were able to receive standard-of-care therapies with acceptable toxicity and to achieve survivals comparable with clinical trials. This was achieved with intense supportive services.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) is associated with poor outcome, and clinical trials are imperative to address this. However, barriers to trial enrollment often exist, particularly in socio-economically challenged populations.

Objective To evaluate the outcome of socio-economically challenged patients who had LAPC, multiple comorbidities, and who were not enrolled on clinical trials, but who were treated with the best standard-of-care.

Methods We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 32 patients diagnosed as having LAPC who were referred to an urban cancer center between 2005 and 2010, analyzing the treatment and outcomes of 19 who underwent treatment at our center.

Results In all 26.3% of the analyzed patients had commercial insurance, 31.6% did not identify English as their preferred language, and 84.2% had 3 or more comorbidities. The median overall survival was 19.1 months, with estimated 1- and 2-year survivals of 60.8% and 36.5%, respectively. The median survival for patients receiving chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation was 26.6 months. Toxicities were controllable. Translation services were required by 26% and social services interventions by 84%. Survival analysis based on insurance coverage did not show a significant association with levels of reimbursement.

Limitations Retrospective study, small sample size, differences in chemotherapy types.

Conclusions These patients, representative of a diverse and socio-economically challenged community, were able to receive standard-of-care therapies with acceptable toxicity and to achieve survivals comparable with clinical trials. This was achieved with intense supportive services.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background Locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) is associated with poor outcome, and clinical trials are imperative to address this. However, barriers to trial enrollment often exist, particularly in socio-economically challenged populations.

Objective To evaluate the outcome of socio-economically challenged patients who had LAPC, multiple comorbidities, and who were not enrolled on clinical trials, but who were treated with the best standard-of-care.

Methods We retrospectively reviewed the charts of 32 patients diagnosed as having LAPC who were referred to an urban cancer center between 2005 and 2010, analyzing the treatment and outcomes of 19 who underwent treatment at our center.

Results In all 26.3% of the analyzed patients had commercial insurance, 31.6% did not identify English as their preferred language, and 84.2% had 3 or more comorbidities. The median overall survival was 19.1 months, with estimated 1- and 2-year survivals of 60.8% and 36.5%, respectively. The median survival for patients receiving chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation was 26.6 months. Toxicities were controllable. Translation services were required by 26% and social services interventions by 84%. Survival analysis based on insurance coverage did not show a significant association with levels of reimbursement.

Limitations Retrospective study, small sample size, differences in chemotherapy types.

Conclusions These patients, representative of a diverse and socio-economically challenged community, were able to receive standard-of-care therapies with acceptable toxicity and to achieve survivals comparable with clinical trials. This was achieved with intense supportive services.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Plasma product now available in US

Credit: Cristina Granados

A pooled plasma product that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in January is now available for use in the US.

The product, called Octaplas, is a sterile, frozen solution of human plasma from several donors that has been treated with a solvent detergent process to minimize the risk of serious virus transmission.

The plasma is collected from US donors who have been screened and tested for diseases transmitted by blood.

Octaplas is indicated for the replacement of multiple coagulation

factors in patients with acquired deficiencies due to liver disease or

undergoing cardiac surgery or liver transplant. Octaplas can also be

used for plasma exchange in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Octaplas is contraindicated in patients with IgA deficiency, severe deficiency of protein S, a history of hypersensitivity to fresh-frozen plasma or plasma-derived products including any plasma protein, or a history of hypersensitivity reaction to Octaplas.

Transfusion reactions can occur with ABO blood group mismatches. High infusion rates can induce hypervolemia with consequent pulmonary edema or cardiac failure.

Excessive bleeding due to hyperfibrinolysis can occur due to low levels of alpha2-antiplasmin. Thrombosis can occur due to low levels of protein S, and citrate toxicity can occur with volumes exceeding 1 mL of Octaplas per kg per minute.

Because Octaplas is made from human plasma, it may carry the risk of transmitting infectious agents; for instance, the variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease agent.

Administering Octaplas

Octaplas should be matched to the recipient’s blood group to help avoid transfusion reactions. Each lot of the product is tested for composition of key clotting factors and is only released if the levels are within acceptable ranges.

The product is administered by intravenous infusion after thawing, using an infusion set with a filter. An aseptic technique must be used throughout the infusion.

The dosage depends upon the clinical situation and the underlying disorder. But 12 to 15 mL/kg of body weight is a generally accepted starting dose, and it should increase the patient’s plasma coagulation factor levels by about 25%.

It is important to monitor patient response, both clinically and with measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and/or specific coagulation factor assays.

To order Octaplas, call your local Blood Center or National Hospital Specialties at 800-344-6087. To request product information, call 201-604-1130.

For prescribing information, visit www.octaplasus.com. Octaplas is manufactured by Octapharma USA. ![]()

Credit: Cristina Granados

A pooled plasma product that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in January is now available for use in the US.

The product, called Octaplas, is a sterile, frozen solution of human plasma from several donors that has been treated with a solvent detergent process to minimize the risk of serious virus transmission.

The plasma is collected from US donors who have been screened and tested for diseases transmitted by blood.

Octaplas is indicated for the replacement of multiple coagulation

factors in patients with acquired deficiencies due to liver disease or

undergoing cardiac surgery or liver transplant. Octaplas can also be

used for plasma exchange in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Octaplas is contraindicated in patients with IgA deficiency, severe deficiency of protein S, a history of hypersensitivity to fresh-frozen plasma or plasma-derived products including any plasma protein, or a history of hypersensitivity reaction to Octaplas.

Transfusion reactions can occur with ABO blood group mismatches. High infusion rates can induce hypervolemia with consequent pulmonary edema or cardiac failure.

Excessive bleeding due to hyperfibrinolysis can occur due to low levels of alpha2-antiplasmin. Thrombosis can occur due to low levels of protein S, and citrate toxicity can occur with volumes exceeding 1 mL of Octaplas per kg per minute.

Because Octaplas is made from human plasma, it may carry the risk of transmitting infectious agents; for instance, the variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease agent.

Administering Octaplas

Octaplas should be matched to the recipient’s blood group to help avoid transfusion reactions. Each lot of the product is tested for composition of key clotting factors and is only released if the levels are within acceptable ranges.

The product is administered by intravenous infusion after thawing, using an infusion set with a filter. An aseptic technique must be used throughout the infusion.

The dosage depends upon the clinical situation and the underlying disorder. But 12 to 15 mL/kg of body weight is a generally accepted starting dose, and it should increase the patient’s plasma coagulation factor levels by about 25%.

It is important to monitor patient response, both clinically and with measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and/or specific coagulation factor assays.

To order Octaplas, call your local Blood Center or National Hospital Specialties at 800-344-6087. To request product information, call 201-604-1130.

For prescribing information, visit www.octaplasus.com. Octaplas is manufactured by Octapharma USA. ![]()

Credit: Cristina Granados

A pooled plasma product that was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in January is now available for use in the US.

The product, called Octaplas, is a sterile, frozen solution of human plasma from several donors that has been treated with a solvent detergent process to minimize the risk of serious virus transmission.

The plasma is collected from US donors who have been screened and tested for diseases transmitted by blood.

Octaplas is indicated for the replacement of multiple coagulation

factors in patients with acquired deficiencies due to liver disease or

undergoing cardiac surgery or liver transplant. Octaplas can also be

used for plasma exchange in patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Octaplas is contraindicated in patients with IgA deficiency, severe deficiency of protein S, a history of hypersensitivity to fresh-frozen plasma or plasma-derived products including any plasma protein, or a history of hypersensitivity reaction to Octaplas.

Transfusion reactions can occur with ABO blood group mismatches. High infusion rates can induce hypervolemia with consequent pulmonary edema or cardiac failure.

Excessive bleeding due to hyperfibrinolysis can occur due to low levels of alpha2-antiplasmin. Thrombosis can occur due to low levels of protein S, and citrate toxicity can occur with volumes exceeding 1 mL of Octaplas per kg per minute.

Because Octaplas is made from human plasma, it may carry the risk of transmitting infectious agents; for instance, the variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease agent.

Administering Octaplas

Octaplas should be matched to the recipient’s blood group to help avoid transfusion reactions. Each lot of the product is tested for composition of key clotting factors and is only released if the levels are within acceptable ranges.

The product is administered by intravenous infusion after thawing, using an infusion set with a filter. An aseptic technique must be used throughout the infusion.

The dosage depends upon the clinical situation and the underlying disorder. But 12 to 15 mL/kg of body weight is a generally accepted starting dose, and it should increase the patient’s plasma coagulation factor levels by about 25%.

It is important to monitor patient response, both clinically and with measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and/or specific coagulation factor assays.

To order Octaplas, call your local Blood Center or National Hospital Specialties at 800-344-6087. To request product information, call 201-604-1130.

For prescribing information, visit www.octaplasus.com. Octaplas is manufactured by Octapharma USA. ![]()

New drug stacks up well against warfarin

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

AMSTERDAM—The oral anticoagulant edoxaban compares favorably with warfarin as treatment for recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to results of the Hokusai-VTE trial.

Edoxaban given after initial low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) proved equally as effective as warfarin given after LMWH.

And patients treated with edoxaban were less likely to experience clinically relevant bleeding than patients who received warfarin.

Results of the trial also offer new insight into a previously under-represented subgroup of patients with pulmonary embolism (PE), suggesting that treatment for this group might need to be different than for other VTE patients, said lead investigator Harry R. Büller, MD, of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

Dr Büller presented these findings at the 2013 European Society of Cardiology Congress, which is taking place August 31 through September 4. The study was also published in NEJM on September 1.

“What makes this study unique is new insight that there are subgroups in which we might need to revisit what we currently think about the treatment of VTE,” Dr Büller said.

The Hokusai-VTE trial included a broad spectrum of VTE patients, including a large subgroup (30%) of patients with PE and right ventricular dysfunction, and another subgroup (20%) at high risk for bleeding due to renal impairment and low body weight.

In total, 4921 patients with deep vein thrombosis and 3319 with PE received initial subcutaneous LMWH therapy and were then randomized to receive edoxaban or warfarin daily for 3 to 12 months.

Patients at a higher risk for bleeding—ie, those with creatinine clearance of 30 to 50 mL/min or body weight below 60 kg—received 30 mg of edoxaban. The rest of the patients in the edoxaban arm received 60 mg. Warfarin patients were dosed according to standard of care.

Overall, edoxaban proved as effective as warfarin. Recurrent symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.2% and 3.5% of patients, respectively (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

However, in the subgroup of patients with PE and evidence of right ventricular dysfunction, efficacy was superior with edoxaban—3.3% and 6.2%, respectively.

Edoxaban proved superior when it came to the primary safety outcome as well. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 8.5% of edoxaban-treated patients and 10.3% of warfarin-treated patients (P=0.004 for superiority).

In the edoxaban arm, there were 2 fatal bleeds and 13 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site. With warfarin, there were 10 fatal bleeds and 25 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site.

“By halving the daily dose of edoxaban to 30 mg [among patients at high risk of bleeding], efficacy was maintained, with significantly less bleeding than observed in the warfarin group,” Dr Büller said.

In this high-risk subgroup, clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 7.9% of those treated with edoxaban, compared to 12.8% of those treated with warfarin. And recurrent symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.0% and 4.2%, respectively.

Previous trials of oral anticoagulants have not identified these specific subgroups, Dr Büller said.

“Our findings are likely to be generalizable in a global setting,” he added. “We included patients with both provoked and unprovoked venous thromboembolism, and treatment durations varied from 3 to 12 months at the discretion of the treating physician.”

This study was supported by Daiichi Sankyo, the company developing edoxaban. ![]()

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

AMSTERDAM—The oral anticoagulant edoxaban compares favorably with warfarin as treatment for recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to results of the Hokusai-VTE trial.

Edoxaban given after initial low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) proved equally as effective as warfarin given after LMWH.

And patients treated with edoxaban were less likely to experience clinically relevant bleeding than patients who received warfarin.

Results of the trial also offer new insight into a previously under-represented subgroup of patients with pulmonary embolism (PE), suggesting that treatment for this group might need to be different than for other VTE patients, said lead investigator Harry R. Büller, MD, of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

Dr Büller presented these findings at the 2013 European Society of Cardiology Congress, which is taking place August 31 through September 4. The study was also published in NEJM on September 1.

“What makes this study unique is new insight that there are subgroups in which we might need to revisit what we currently think about the treatment of VTE,” Dr Büller said.

The Hokusai-VTE trial included a broad spectrum of VTE patients, including a large subgroup (30%) of patients with PE and right ventricular dysfunction, and another subgroup (20%) at high risk for bleeding due to renal impairment and low body weight.

In total, 4921 patients with deep vein thrombosis and 3319 with PE received initial subcutaneous LMWH therapy and were then randomized to receive edoxaban or warfarin daily for 3 to 12 months.

Patients at a higher risk for bleeding—ie, those with creatinine clearance of 30 to 50 mL/min or body weight below 60 kg—received 30 mg of edoxaban. The rest of the patients in the edoxaban arm received 60 mg. Warfarin patients were dosed according to standard of care.

Overall, edoxaban proved as effective as warfarin. Recurrent symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.2% and 3.5% of patients, respectively (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

However, in the subgroup of patients with PE and evidence of right ventricular dysfunction, efficacy was superior with edoxaban—3.3% and 6.2%, respectively.

Edoxaban proved superior when it came to the primary safety outcome as well. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 8.5% of edoxaban-treated patients and 10.3% of warfarin-treated patients (P=0.004 for superiority).

In the edoxaban arm, there were 2 fatal bleeds and 13 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site. With warfarin, there were 10 fatal bleeds and 25 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site.

“By halving the daily dose of edoxaban to 30 mg [among patients at high risk of bleeding], efficacy was maintained, with significantly less bleeding than observed in the warfarin group,” Dr Büller said.

In this high-risk subgroup, clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 7.9% of those treated with edoxaban, compared to 12.8% of those treated with warfarin. And recurrent symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.0% and 4.2%, respectively.

Previous trials of oral anticoagulants have not identified these specific subgroups, Dr Büller said.

“Our findings are likely to be generalizable in a global setting,” he added. “We included patients with both provoked and unprovoked venous thromboembolism, and treatment durations varied from 3 to 12 months at the discretion of the treating physician.”

This study was supported by Daiichi Sankyo, the company developing edoxaban. ![]()

Image by Kevin MacKenzie

AMSTERDAM—The oral anticoagulant edoxaban compares favorably with warfarin as treatment for recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE), according to results of the Hokusai-VTE trial.

Edoxaban given after initial low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) proved equally as effective as warfarin given after LMWH.

And patients treated with edoxaban were less likely to experience clinically relevant bleeding than patients who received warfarin.

Results of the trial also offer new insight into a previously under-represented subgroup of patients with pulmonary embolism (PE), suggesting that treatment for this group might need to be different than for other VTE patients, said lead investigator Harry R. Büller, MD, of the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

Dr Büller presented these findings at the 2013 European Society of Cardiology Congress, which is taking place August 31 through September 4. The study was also published in NEJM on September 1.

“What makes this study unique is new insight that there are subgroups in which we might need to revisit what we currently think about the treatment of VTE,” Dr Büller said.

The Hokusai-VTE trial included a broad spectrum of VTE patients, including a large subgroup (30%) of patients with PE and right ventricular dysfunction, and another subgroup (20%) at high risk for bleeding due to renal impairment and low body weight.

In total, 4921 patients with deep vein thrombosis and 3319 with PE received initial subcutaneous LMWH therapy and were then randomized to receive edoxaban or warfarin daily for 3 to 12 months.

Patients at a higher risk for bleeding—ie, those with creatinine clearance of 30 to 50 mL/min or body weight below 60 kg—received 30 mg of edoxaban. The rest of the patients in the edoxaban arm received 60 mg. Warfarin patients were dosed according to standard of care.

Overall, edoxaban proved as effective as warfarin. Recurrent symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.2% and 3.5% of patients, respectively (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

However, in the subgroup of patients with PE and evidence of right ventricular dysfunction, efficacy was superior with edoxaban—3.3% and 6.2%, respectively.

Edoxaban proved superior when it came to the primary safety outcome as well. Clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 8.5% of edoxaban-treated patients and 10.3% of warfarin-treated patients (P=0.004 for superiority).

In the edoxaban arm, there were 2 fatal bleeds and 13 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site. With warfarin, there were 10 fatal bleeds and 25 non-fatal bleeds in a critical site.

“By halving the daily dose of edoxaban to 30 mg [among patients at high risk of bleeding], efficacy was maintained, with significantly less bleeding than observed in the warfarin group,” Dr Büller said.

In this high-risk subgroup, clinically relevant bleeding occurred in 7.9% of those treated with edoxaban, compared to 12.8% of those treated with warfarin. And recurrent symptomatic VTE occurred in 3.0% and 4.2%, respectively.

Previous trials of oral anticoagulants have not identified these specific subgroups, Dr Büller said.

“Our findings are likely to be generalizable in a global setting,” he added. “We included patients with both provoked and unprovoked venous thromboembolism, and treatment durations varied from 3 to 12 months at the discretion of the treating physician.”

This study was supported by Daiichi Sankyo, the company developing edoxaban. ![]()

Building patient-centered care through values assessment integration with advance care planning

Oncologists frequently have to make diagnoses that portend bad outcomes and difficulties in management, among them, for stage IV lung or pancreatic cancer. Many recent studies have shown the importance of appropriate implementation of palliative care and the need for discussing with the patient the goals of treatment early in diagnosis.1-3

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Oncologists frequently have to make diagnoses that portend bad outcomes and difficulties in management, among them, for stage IV lung or pancreatic cancer. Many recent studies have shown the importance of appropriate implementation of palliative care and the need for discussing with the patient the goals of treatment early in diagnosis.1-3

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Oncologists frequently have to make diagnoses that portend bad outcomes and difficulties in management, among them, for stage IV lung or pancreatic cancer. Many recent studies have shown the importance of appropriate implementation of palliative care and the need for discussing with the patient the goals of treatment early in diagnosis.1-3

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Three Factors Tied to Femoral Artery Aneurysm Outcomes

SAN FRANCISCO - Predictors of acute aneurysm - related complications were aneurysm size of 4 cm or greater, thrombus, and age younger than 60 years, in a study of patients with isolated degenerative femoral artery aneurysms.

"Acute complications have not occurred in patients with FAAs less than 3.5 cm, suggesting that this should be adopted as a new threshold for elective repair," Dr. Gustavo S. Oderich said at the Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting.

Femoral artery aneurysms (FAAs) are rare, affecting 5/100,000 individuals, said Dr. Oderich, a vascular surgeon who practices at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Current indications for repair are symptoms, size greater than 2.5 cm, growth, and thrombus.

Most reports of FAAs predate modern imaging. These studies "are limited by the small number of patients, mixed etiology, and short follow-up," Dr. Oderich said. "The purpose of the current study was to review the clinical presentation, management strategies, and outcomes of degenerative FAAs in a larger cohort of patients."

For the study, led by Dr. Peter F. Lawrence of the University of California, Los Angeles, researchers retrospectively studied patients treated for degenerative FAAs between 2002 and 2012 at eight medical centers in the United States. Iatrogenic, anastomotic, and mycotic aneurysms were excluded from the analysis. Endpoints of interest were morbidity and mortality with operative repair; acute aneurysm - related complications including rupture, thrombosis, and embolization; and patient survival.

Dr. Oderich reported on 236 FAAs that occurred in 182 patients. The mean size was 32 cm. Most (81%) were located on the common femoral artery, 14% were located on the superficial femoral artery, and 5% were located on the profunda femoris artery. The majority of patients (88%) had synchronous aneurysms in other locations. The most common locations outside of the femoral artery were the aortic (62%) artery, common iliac arteries (60%), popliteal arteries (47%), and bilateral FAAs (25%).

The mean age of patients was 73 and 94% of patients were male. At presentation 63% of patients were asymptomatic. The most common signs and symptoms were palpable mass (29%), claudication (22%), and local pain (10%).

When the researchers compared symptomatic versus asymptomatic aneurysms, symptomatic aneurysms were larger, had more intraluminal thrombus, and more often affected the profunda femoral artery .Only 12 patients (5%) had acute events, most of them rupture or thrombosis, with a size of 3.5-7 cm in range.

Independent predictors associated with acute aneurysm - related complications were a diameter of 4 cm or greater (P = less than .001), an intraluminal thrombus (P = less than .001), and age younger than 60 (P = .004). Freedom from repair among patients with asymptomatic FAAs was 21% at 5 years, "largely reflecting our practice of indicating the operation for aneurysms greater than 2.5 cm," Dr. Oderich said. The most common indications for repair were pain (34%), intramural thrombus (27%), and size of 2.5 cm or greater (23%).

He reported that 138 patients underwent open repair and 3 patients underwent endovascular treatment of 177 FAAs. The most frequent form of reconstruction was an interposition graft (80%) or bypass (20%). Among the 141 patients who had operative treatment, the 30-day mortality was 1.5%, the morbidity rate was 20%, and the mean length of stay was 7 days. During a mean follow-up of 49 months, there were 35 nonaneurysm-related deaths (27%) and 1 graft-related complication. Patient survival at 5 years was 61%.

"Repair of smaller FAAs may be indicated in patients with intramural thrombus or progressive enlargement," Dr. Oderich concluded. "Current repair of all symptomatic FAAs should remain unchanged. Operative repair was associated with low mortality, morbidity, and durable results."

Decision making when faced with a patient with a degenerative femoral artery aneurysm has always been based on small series. Especially when deciding what size asymptomatic aneurysm is too big to continue to watch, the available data are weak.

The authors pooled a large number of cases from eight institutions to assemble a dataset of 236 FAAs, 25% of which were apparently observed without repair. (Disclaimer: One of my partners contributed data to this series.) They noted that no asymptomatic aneurysm less than 3.5 cm developed an acute complication, and concluded that the threshold for repair of these lesions should rise to at least 3.5 cm in diameter.

Although this report is retrospective and almost certainly contains selection bias, this conclusion seems valid to me at a gut level. I also agree that any symptoms or the presence of significant mural thrombus should prompt repair. Until we are able to capitalize on the capacity of electronic medical records to determine the clinical outcome of patients on the basis of diagnosis rather than what surgical procedure they have had, this is probably the best data we are likely to see regarding the management of FAA.

Dr. Larry W. Kraiss is professor and chief of vascular surgery at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and is an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Decision making when faced with a patient with a degenerative femoral artery aneurysm has always been based on small series. Especially when deciding what size asymptomatic aneurysm is too big to continue to watch, the available data are weak.

The authors pooled a large number of cases from eight institutions to assemble a dataset of 236 FAAs, 25% of which were apparently observed without repair. (Disclaimer: One of my partners contributed data to this series.) They noted that no asymptomatic aneurysm less than 3.5 cm developed an acute complication, and concluded that the threshold for repair of these lesions should rise to at least 3.5 cm in diameter.

Although this report is retrospective and almost certainly contains selection bias, this conclusion seems valid to me at a gut level. I also agree that any symptoms or the presence of significant mural thrombus should prompt repair. Until we are able to capitalize on the capacity of electronic medical records to determine the clinical outcome of patients on the basis of diagnosis rather than what surgical procedure they have had, this is probably the best data we are likely to see regarding the management of FAA.

Dr. Larry W. Kraiss is professor and chief of vascular surgery at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and is an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

Decision making when faced with a patient with a degenerative femoral artery aneurysm has always been based on small series. Especially when deciding what size asymptomatic aneurysm is too big to continue to watch, the available data are weak.

The authors pooled a large number of cases from eight institutions to assemble a dataset of 236 FAAs, 25% of which were apparently observed without repair. (Disclaimer: One of my partners contributed data to this series.) They noted that no asymptomatic aneurysm less than 3.5 cm developed an acute complication, and concluded that the threshold for repair of these lesions should rise to at least 3.5 cm in diameter.

Although this report is retrospective and almost certainly contains selection bias, this conclusion seems valid to me at a gut level. I also agree that any symptoms or the presence of significant mural thrombus should prompt repair. Until we are able to capitalize on the capacity of electronic medical records to determine the clinical outcome of patients on the basis of diagnosis rather than what surgical procedure they have had, this is probably the best data we are likely to see regarding the management of FAA.

Dr. Larry W. Kraiss is professor and chief of vascular surgery at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and is an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

SAN FRANCISCO - Predictors of acute aneurysm - related complications were aneurysm size of 4 cm or greater, thrombus, and age younger than 60 years, in a study of patients with isolated degenerative femoral artery aneurysms.

"Acute complications have not occurred in patients with FAAs less than 3.5 cm, suggesting that this should be adopted as a new threshold for elective repair," Dr. Gustavo S. Oderich said at the Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting.

Femoral artery aneurysms (FAAs) are rare, affecting 5/100,000 individuals, said Dr. Oderich, a vascular surgeon who practices at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Current indications for repair are symptoms, size greater than 2.5 cm, growth, and thrombus.

Most reports of FAAs predate modern imaging. These studies "are limited by the small number of patients, mixed etiology, and short follow-up," Dr. Oderich said. "The purpose of the current study was to review the clinical presentation, management strategies, and outcomes of degenerative FAAs in a larger cohort of patients."

For the study, led by Dr. Peter F. Lawrence of the University of California, Los Angeles, researchers retrospectively studied patients treated for degenerative FAAs between 2002 and 2012 at eight medical centers in the United States. Iatrogenic, anastomotic, and mycotic aneurysms were excluded from the analysis. Endpoints of interest were morbidity and mortality with operative repair; acute aneurysm - related complications including rupture, thrombosis, and embolization; and patient survival.

Dr. Oderich reported on 236 FAAs that occurred in 182 patients. The mean size was 32 cm. Most (81%) were located on the common femoral artery, 14% were located on the superficial femoral artery, and 5% were located on the profunda femoris artery. The majority of patients (88%) had synchronous aneurysms in other locations. The most common locations outside of the femoral artery were the aortic (62%) artery, common iliac arteries (60%), popliteal arteries (47%), and bilateral FAAs (25%).

The mean age of patients was 73 and 94% of patients were male. At presentation 63% of patients were asymptomatic. The most common signs and symptoms were palpable mass (29%), claudication (22%), and local pain (10%).

When the researchers compared symptomatic versus asymptomatic aneurysms, symptomatic aneurysms were larger, had more intraluminal thrombus, and more often affected the profunda femoral artery .Only 12 patients (5%) had acute events, most of them rupture or thrombosis, with a size of 3.5-7 cm in range.

Independent predictors associated with acute aneurysm - related complications were a diameter of 4 cm or greater (P = less than .001), an intraluminal thrombus (P = less than .001), and age younger than 60 (P = .004). Freedom from repair among patients with asymptomatic FAAs was 21% at 5 years, "largely reflecting our practice of indicating the operation for aneurysms greater than 2.5 cm," Dr. Oderich said. The most common indications for repair were pain (34%), intramural thrombus (27%), and size of 2.5 cm or greater (23%).

He reported that 138 patients underwent open repair and 3 patients underwent endovascular treatment of 177 FAAs. The most frequent form of reconstruction was an interposition graft (80%) or bypass (20%). Among the 141 patients who had operative treatment, the 30-day mortality was 1.5%, the morbidity rate was 20%, and the mean length of stay was 7 days. During a mean follow-up of 49 months, there were 35 nonaneurysm-related deaths (27%) and 1 graft-related complication. Patient survival at 5 years was 61%.

"Repair of smaller FAAs may be indicated in patients with intramural thrombus or progressive enlargement," Dr. Oderich concluded. "Current repair of all symptomatic FAAs should remain unchanged. Operative repair was associated with low mortality, morbidity, and durable results."

SAN FRANCISCO - Predictors of acute aneurysm - related complications were aneurysm size of 4 cm or greater, thrombus, and age younger than 60 years, in a study of patients with isolated degenerative femoral artery aneurysms.

"Acute complications have not occurred in patients with FAAs less than 3.5 cm, suggesting that this should be adopted as a new threshold for elective repair," Dr. Gustavo S. Oderich said at the Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting.

Femoral artery aneurysms (FAAs) are rare, affecting 5/100,000 individuals, said Dr. Oderich, a vascular surgeon who practices at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Current indications for repair are symptoms, size greater than 2.5 cm, growth, and thrombus.

Most reports of FAAs predate modern imaging. These studies "are limited by the small number of patients, mixed etiology, and short follow-up," Dr. Oderich said. "The purpose of the current study was to review the clinical presentation, management strategies, and outcomes of degenerative FAAs in a larger cohort of patients."

For the study, led by Dr. Peter F. Lawrence of the University of California, Los Angeles, researchers retrospectively studied patients treated for degenerative FAAs between 2002 and 2012 at eight medical centers in the United States. Iatrogenic, anastomotic, and mycotic aneurysms were excluded from the analysis. Endpoints of interest were morbidity and mortality with operative repair; acute aneurysm - related complications including rupture, thrombosis, and embolization; and patient survival.

Dr. Oderich reported on 236 FAAs that occurred in 182 patients. The mean size was 32 cm. Most (81%) were located on the common femoral artery, 14% were located on the superficial femoral artery, and 5% were located on the profunda femoris artery. The majority of patients (88%) had synchronous aneurysms in other locations. The most common locations outside of the femoral artery were the aortic (62%) artery, common iliac arteries (60%), popliteal arteries (47%), and bilateral FAAs (25%).

The mean age of patients was 73 and 94% of patients were male. At presentation 63% of patients were asymptomatic. The most common signs and symptoms were palpable mass (29%), claudication (22%), and local pain (10%).

When the researchers compared symptomatic versus asymptomatic aneurysms, symptomatic aneurysms were larger, had more intraluminal thrombus, and more often affected the profunda femoral artery .Only 12 patients (5%) had acute events, most of them rupture or thrombosis, with a size of 3.5-7 cm in range.

Independent predictors associated with acute aneurysm - related complications were a diameter of 4 cm or greater (P = less than .001), an intraluminal thrombus (P = less than .001), and age younger than 60 (P = .004). Freedom from repair among patients with asymptomatic FAAs was 21% at 5 years, "largely reflecting our practice of indicating the operation for aneurysms greater than 2.5 cm," Dr. Oderich said. The most common indications for repair were pain (34%), intramural thrombus (27%), and size of 2.5 cm or greater (23%).

He reported that 138 patients underwent open repair and 3 patients underwent endovascular treatment of 177 FAAs. The most frequent form of reconstruction was an interposition graft (80%) or bypass (20%). Among the 141 patients who had operative treatment, the 30-day mortality was 1.5%, the morbidity rate was 20%, and the mean length of stay was 7 days. During a mean follow-up of 49 months, there were 35 nonaneurysm-related deaths (27%) and 1 graft-related complication. Patient survival at 5 years was 61%.

"Repair of smaller FAAs may be indicated in patients with intramural thrombus or progressive enlargement," Dr. Oderich concluded. "Current repair of all symptomatic FAAs should remain unchanged. Operative repair was associated with low mortality, morbidity, and durable results."

AT THE SVS ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: Among patients treated for isolated degenerative femoral artery aneurysms, independent predictors associated with acute aneurysm–related complications were a diameter of 4 cm or greater (P = less than .001), an intraluminal thrombus (P = less than .001), and age younger than 60 (P = .004).

Data source: A retrospective study of 182 patients in the United States who were treated for 236 femoral artery aneurysms that occurred between 2002 and 2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Oderich disclosed that he has served as a consultant to W.L. Gore and Cook Medical.

High-grade prostate adenocarcinoma: survival and disease control after radical prostatectomy

Background and objective The optimal primary intervention for treatment of clinically localized high-grade prostate adenocarcinoma remains to be identified. The present investigation reports disease control and survival outcomes in patients treated with primary radical prostatectomy.

Methods Eligible patients were diagnosed with Gleason score 8-10 at diagnostic biopsy and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) greater than 30 ng/mL, treated with primary radical prostatectomy, without clinical evidence of distant metastatic disease, seminal vesicle invasion, or lymph node involvement. Demographic, treatment, and outcome data were retrospectively collected and analyzed from a clinical database. Survival analysis methods were employed to assess disease control and survival rates, as well as association of patient-, tumor-, and treatment-specific factors for endpoints.

Results Fifty patients were eligible for the present analysis, with Gleason 8 and 9 in 32 (64%) and 18 (36%) patients, respectively. Surgical margin, seminal vesicle, and lymph node involvement were noted 32 (64%), 18 (36%), and 6 (12%) patients, respectively; only 4 (8%) received adjuvant radiotherapy. At a median follow-up of 44.9 months (range, 4.2-104.6), 33 patients (66%) had experienced PSA relapse, of whom 7 have been successfully salvaged. Four patients died, all with uncontrolled disease. The estimated 5-year freedom from failure was 17%. Interval from biopsy to prostatectomy, surgical margin status, and seminal vesicle involvement were associated with decreased overall survival.

Conclusions High-risk Gleason score at biopsy is associated with suboptimal PSA control at 5 years following prostatectomy alone; however, in the setting of uninvolved seminal vesicles and lymph nodes, the dominant pattern of failure appears to be local, and early postoperative radiotherapy should be considered.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background and objective The optimal primary intervention for treatment of clinically localized high-grade prostate adenocarcinoma remains to be identified. The present investigation reports disease control and survival outcomes in patients treated with primary radical prostatectomy.

Methods Eligible patients were diagnosed with Gleason score 8-10 at diagnostic biopsy and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) greater than 30 ng/mL, treated with primary radical prostatectomy, without clinical evidence of distant metastatic disease, seminal vesicle invasion, or lymph node involvement. Demographic, treatment, and outcome data were retrospectively collected and analyzed from a clinical database. Survival analysis methods were employed to assess disease control and survival rates, as well as association of patient-, tumor-, and treatment-specific factors for endpoints.

Results Fifty patients were eligible for the present analysis, with Gleason 8 and 9 in 32 (64%) and 18 (36%) patients, respectively. Surgical margin, seminal vesicle, and lymph node involvement were noted 32 (64%), 18 (36%), and 6 (12%) patients, respectively; only 4 (8%) received adjuvant radiotherapy. At a median follow-up of 44.9 months (range, 4.2-104.6), 33 patients (66%) had experienced PSA relapse, of whom 7 have been successfully salvaged. Four patients died, all with uncontrolled disease. The estimated 5-year freedom from failure was 17%. Interval from biopsy to prostatectomy, surgical margin status, and seminal vesicle involvement were associated with decreased overall survival.

Conclusions High-risk Gleason score at biopsy is associated with suboptimal PSA control at 5 years following prostatectomy alone; however, in the setting of uninvolved seminal vesicles and lymph nodes, the dominant pattern of failure appears to be local, and early postoperative radiotherapy should be considered.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Background and objective The optimal primary intervention for treatment of clinically localized high-grade prostate adenocarcinoma remains to be identified. The present investigation reports disease control and survival outcomes in patients treated with primary radical prostatectomy.

Methods Eligible patients were diagnosed with Gleason score 8-10 at diagnostic biopsy and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) greater than 30 ng/mL, treated with primary radical prostatectomy, without clinical evidence of distant metastatic disease, seminal vesicle invasion, or lymph node involvement. Demographic, treatment, and outcome data were retrospectively collected and analyzed from a clinical database. Survival analysis methods were employed to assess disease control and survival rates, as well as association of patient-, tumor-, and treatment-specific factors for endpoints.

Results Fifty patients were eligible for the present analysis, with Gleason 8 and 9 in 32 (64%) and 18 (36%) patients, respectively. Surgical margin, seminal vesicle, and lymph node involvement were noted 32 (64%), 18 (36%), and 6 (12%) patients, respectively; only 4 (8%) received adjuvant radiotherapy. At a median follow-up of 44.9 months (range, 4.2-104.6), 33 patients (66%) had experienced PSA relapse, of whom 7 have been successfully salvaged. Four patients died, all with uncontrolled disease. The estimated 5-year freedom from failure was 17%. Interval from biopsy to prostatectomy, surgical margin status, and seminal vesicle involvement were associated with decreased overall survival.

Conclusions High-risk Gleason score at biopsy is associated with suboptimal PSA control at 5 years following prostatectomy alone; however, in the setting of uninvolved seminal vesicles and lymph nodes, the dominant pattern of failure appears to be local, and early postoperative radiotherapy should be considered.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Omacetaxine for chronic or accelerated phase CML in patients with resistance or intolerance to TKIs

Omacetaxine mepesuccinate has been granted accelerated approval for the treatment of adult patients with chronic phase (CP) or accelerated phase (AP) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with resistance or intolerance to 2 or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).1,2 Approval was based on response rates observed in a combined cohort of adult CML patients from 2 clinical trials. As yet, no clinical trials have verified improved disease-related symptoms or increased survival with omacetaxine treatment.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Omacetaxine mepesuccinate has been granted accelerated approval for the treatment of adult patients with chronic phase (CP) or accelerated phase (AP) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with resistance or intolerance to 2 or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).1,2 Approval was based on response rates observed in a combined cohort of adult CML patients from 2 clinical trials. As yet, no clinical trials have verified improved disease-related symptoms or increased survival with omacetaxine treatment.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Omacetaxine mepesuccinate has been granted accelerated approval for the treatment of adult patients with chronic phase (CP) or accelerated phase (AP) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with resistance or intolerance to 2 or more tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).1,2 Approval was based on response rates observed in a combined cohort of adult CML patients from 2 clinical trials. As yet, no clinical trials have verified improved disease-related symptoms or increased survival with omacetaxine treatment.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

PODCAST: Evidence-based Medicine in Hospital Practice

This month, our issue features a discussion on evidence-based medicine and how hospitalists can incorporate EMB into their daily routine.

Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief of hospital medicine and chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Michigan shares his approach to making the best clinical evidence part of his daily practice. Dr. Dan Elliot, associate chair of research at Christina Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware discusses the “straight As,” of EMB, while Dr. Craig Umscheid, internist and epidemiologist at University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia talks about how to define a clinical question and why synthesizing evidence via systematic review is important.

Click here to listen to our evidence-based medicine podcast.

This month, our issue features a discussion on evidence-based medicine and how hospitalists can incorporate EMB into their daily routine.

Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief of hospital medicine and chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Michigan shares his approach to making the best clinical evidence part of his daily practice. Dr. Dan Elliot, associate chair of research at Christina Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware discusses the “straight As,” of EMB, while Dr. Craig Umscheid, internist and epidemiologist at University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia talks about how to define a clinical question and why synthesizing evidence via systematic review is important.

Click here to listen to our evidence-based medicine podcast.

This month, our issue features a discussion on evidence-based medicine and how hospitalists can incorporate EMB into their daily routine.

Dr. Scott Kaatz, chief of hospital medicine and chief quality officer at Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Michigan shares his approach to making the best clinical evidence part of his daily practice. Dr. Dan Elliot, associate chair of research at Christina Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware discusses the “straight As,” of EMB, while Dr. Craig Umscheid, internist and epidemiologist at University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia talks about how to define a clinical question and why synthesizing evidence via systematic review is important.

Click here to listen to our evidence-based medicine podcast.

Inside Hospitalists' Evolving Scope of Practice

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

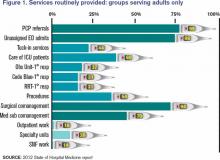

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

In the October 2012 issue of The Hospitalist, the “Survey Insights” article discussed hospitalists’ evolving scope of practice based on information published in the 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report. The report remains the most authoritative, comprehensive source of information about our rapidly developing specialty, and this important topic is worthy of continued attention.

As I begin to orient a new class of hospitalists in my own HM group (HMG), I emphasize the five S’s of HMGs: scope, salary, schedule, structure, and society. HMGs define who they are largely by these constructs. As a specialty, we will define who we are by how we develop these constructs as a community. And it may indeed be the scope that most confirms our identity.

The survey (www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey) paints a self-portrait: What do we see when we look at that image? Figure 1 (below) lists information about services routinely provided by hospitalists, and one could divide the findings into three general categories.

First and foremost, there is the core work. It is clear that virtually all HMGs attended to primary-care-physician referrals and unassigned ED hospitalizations, and they also served as at least consultants for surgical comanagement. Most HMGs are now doing medical subspecialty comanagement, and the data would indicate that we are admitting and attending many of these patients. This raises the question about whether our identity will morph to that of the “universal admitter.” Many contend that health-care change forces will continue to pressure in this direction unless, and until, medical subspecialties develop their own dedicated hospitalists. Many hospitals may not be able to resource this; hence, there will likely be persistent pressure for the HMGs to provide this scope of care.

Perhaps half of HMGs provide the second group of services, which includes primary clinical care for rapid-response teams, code blue teams, and observation units. Forty-four percent of adult hospitalist programs provide a “tuck-in” service (nighttime coverage for other providers), and about 50% of HMGs reported performing procedures. Although this graph might suggest a decline in the proportion of groups caring for ICU patients compared with the 78% that was reported in 2011, this data set includes academic practices (the 2011 data didn’t). For nonacademic adult medicine practices, the proportion doing ICU work actually rose to 83.5% in 2012 from 78% in 2011. Larger hospitals and university settings are increasingly employing intensivists for ICU coverage, but the national deficit of intensivists will likely continue the external pressure for hospitalists to provide ICU care in many settings.

The final group of services represents the “road less traveled”—work in outpatient settings in such specialty units as long-term acute care, psychiatric wings, and skilled nursing facilities. These might prove to be niche opportunities or possible distractions.

There remains, however, the core work that identifies our specialty. We all do it, people depend on us to have it done, and it largely defines who we are as individuals, as HMGs, and as the fastest-growing specialty in American medical history.

Dr. Landis is medical director of Wellspan Hospitalists in York, Pa., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Actors Help Health-Care Providers Develop Better Patient Communication Skills

Hospitalists and ED physicians at Newton Medical Center in New Jersey recently participated in an improvised, interactive learning experience with actors who portrayed problematic patients. “Developing Doctor-Patient Relations through Better Communication” is a curriculum to test and teach communication skills for doctors that was created by Anthony Orsini, MD, a neonatologist at Morristown Medical Center, Newton’s sister facility in the Atlantic Health System. Dr. Orsini founded the Breaking Bad News Foundation (www.bbnfoundation.org) more than a decade ago to help health professionals impart bad medical news to patients and families.

Physicians role-play with actors in such difficult scenarios as imparting a troubling diagnosis to a patient who does not want to hear it. This interaction is viewed remotely by instructors from the foundation and by peers, who then meet with the doctor to go over the videotaped encounter regarding its effectiveness, spoken messages, body language, and other communications.

The project to improve staff communication skills is enhancing teamwork between Newton’s hospitalists and emergency doctors, according to David Stuhlmiller, MD, the hospital’s director of emergency medicine.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

References

- Hartocollis A. With money at risk, hospitals push staff to wash hands. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/nyregion/hospitals-struggle-to-get-workers-to-wash-their-hands.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed May 28, 2013.

- Cumbler E, Castillo L, Satorie L, et al. Culture change in infection control: applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 May 10 [Epub ahead of print].

- Bernhard B. High tech hand washing comes to St. Louis hospital. St. Louis Post-Dispatch website. Available at: http://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/health/high-tech-hand-washing-comes-to-st-louis-hospital/article_9379065d-85ff-5643-bae2-899254cb22fa.html. Accessed June 27, 2013.

- Lowe TJ, Partovian C, Kroch E, Martin J, Bankowitz R. Measuring cardiac waste: the Premier cardiac waste measures. Am J Med Qual. 2013 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- Jackson Healthcare. Filling the void: 2013 physician outlook & practice trends. Jackson Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/193525/jc-2013physiciantrends-void_ebk0513.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

Hospitalists and ED physicians at Newton Medical Center in New Jersey recently participated in an improvised, interactive learning experience with actors who portrayed problematic patients. “Developing Doctor-Patient Relations through Better Communication” is a curriculum to test and teach communication skills for doctors that was created by Anthony Orsini, MD, a neonatologist at Morristown Medical Center, Newton’s sister facility in the Atlantic Health System. Dr. Orsini founded the Breaking Bad News Foundation (www.bbnfoundation.org) more than a decade ago to help health professionals impart bad medical news to patients and families.

Physicians role-play with actors in such difficult scenarios as imparting a troubling diagnosis to a patient who does not want to hear it. This interaction is viewed remotely by instructors from the foundation and by peers, who then meet with the doctor to go over the videotaped encounter regarding its effectiveness, spoken messages, body language, and other communications.

The project to improve staff communication skills is enhancing teamwork between Newton’s hospitalists and emergency doctors, according to David Stuhlmiller, MD, the hospital’s director of emergency medicine.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

References

- Hartocollis A. With money at risk, hospitals push staff to wash hands. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/nyregion/hospitals-struggle-to-get-workers-to-wash-their-hands.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed May 28, 2013.

- Cumbler E, Castillo L, Satorie L, et al. Culture change in infection control: applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 May 10 [Epub ahead of print].

- Bernhard B. High tech hand washing comes to St. Louis hospital. St. Louis Post-Dispatch website. Available at: http://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/health/high-tech-hand-washing-comes-to-st-louis-hospital/article_9379065d-85ff-5643-bae2-899254cb22fa.html. Accessed June 27, 2013.

- Lowe TJ, Partovian C, Kroch E, Martin J, Bankowitz R. Measuring cardiac waste: the Premier cardiac waste measures. Am J Med Qual. 2013 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- Jackson Healthcare. Filling the void: 2013 physician outlook & practice trends. Jackson Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/193525/jc-2013physiciantrends-void_ebk0513.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

Hospitalists and ED physicians at Newton Medical Center in New Jersey recently participated in an improvised, interactive learning experience with actors who portrayed problematic patients. “Developing Doctor-Patient Relations through Better Communication” is a curriculum to test and teach communication skills for doctors that was created by Anthony Orsini, MD, a neonatologist at Morristown Medical Center, Newton’s sister facility in the Atlantic Health System. Dr. Orsini founded the Breaking Bad News Foundation (www.bbnfoundation.org) more than a decade ago to help health professionals impart bad medical news to patients and families.

Physicians role-play with actors in such difficult scenarios as imparting a troubling diagnosis to a patient who does not want to hear it. This interaction is viewed remotely by instructors from the foundation and by peers, who then meet with the doctor to go over the videotaped encounter regarding its effectiveness, spoken messages, body language, and other communications.

The project to improve staff communication skills is enhancing teamwork between Newton’s hospitalists and emergency doctors, according to David Stuhlmiller, MD, the hospital’s director of emergency medicine.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in San Francisco.

References

- Hartocollis A. With money at risk, hospitals push staff to wash hands. The New York Times website. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/29/nyregion/hospitals-struggle-to-get-workers-to-wash-their-hands.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed May 28, 2013.

- Cumbler E, Castillo L, Satorie L, et al. Culture change in infection control: applying psychological principles to improve hand hygiene. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 May 10 [Epub ahead of print].

- Bernhard B. High tech hand washing comes to St. Louis hospital. St. Louis Post-Dispatch website. Available at: http://www.stltoday.com/lifestyles/health-med-fit/health/high-tech-hand-washing-comes-to-st-louis-hospital/article_9379065d-85ff-5643-bae2-899254cb22fa.html. Accessed June 27, 2013.

- Lowe TJ, Partovian C, Kroch E, Martin J, Bankowitz R. Measuring cardiac waste: the Premier cardiac waste measures. Am J Med Qual. 2013 May 29 [Epub ahead of print].

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Readmissions to U.S. hospitals by diagnosis, 2010. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project website. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb153.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.

- Jackson Healthcare. Filling the void: 2013 physician outlook & practice trends. Jackson Healthcare website. Available at: http://www.jacksonhealthcare.com/media/193525/jc-2013physiciantrends-void_ebk0513.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2013.