User login

Chronic itch on the upper back, with pain

A 47-year-old man had had a chronic itch on his back for 2 years. He had no history of trauma to the site, nor did he recall applying topical products to that area.

He was otherwise healthy. He worked as an electrician and said he occasionally experienced cervical and back pain while working.

An examination revealed two grayish-brown ovoid patches on the upper back, each 5 cm to 7 cm in diameter (Figure 1).

DIAGNOSIS: NOTALGIA PARESTHETICA

Chronic, brown-gray, itching patches on the back in an adult patient are characteristic of notalgia paresthetica.

Conditions that may be included in the differential diagnosis but that do not match the presentation in this patient include the following:

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis, which may exhibit several morphologies, but itching would be unusual

- Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus, characterized by scarring and atrophic plaques, but mainly on the face and scalp

- Contact dermatitis, an itchy eczematous condition, characterized by scaly erythematous plaques

- Lichen amyloidosis, a variant of cutaneous amyloidosis characterized by the deposition of amyloid or amyloid-like proteins in the dermis, resulting in red-brown hyperkeratotic lichenoid papules, usually on the pretibial surfaces.

CAUSES AND MANAGEMENT

Notalgia paresthetica is a neuropathic syndrome of the skin of the middle of the back characterized by localized pruritus.1–3 Although common, it often goes undiagnosed.1,3,4 It tends to be chronic, with periodic remissions and exacerbations.

Notalgia paresthetica is thought to be a sensory neuropathy and may result from compression of the posterior rami of spinal nerve segments T2 to T6. Slight degenerative changes are often but not always observed, and their clinical significance is uncertain.1,2,4 The condition affects people of all races and both sexes, usually adults ages 40 to 80.

Clinically, it presents as localized pruritus on the back, usually within the dermatomes T2 to T6.5 Examination reveals a hyperpigmented patch, sometimes with excoriations.5

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings. Laboratory tests are not useful. Imaging is not needed, but magnetic resonance imaging and evaluation by an orthopedic surgeon are appropriate when there is chronic focal pain. Skin biopsy is usually not necessary, although it may be useful in some patients to exclude other conditions. When biopsy is done, macular amyloidosis or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is seen.

Treatment is difficult. Topical steroids and oral antihistamines are usually ineffective,5 but topical capsaicin may provide temporary relief.3 The most recommended treatment in patients with notalgia paresthetica and underlying spinal disease is evaluation and conservative management of the spinal disease, including progressive exercise and rehabilitation.2 Other therapies include oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, phototherapy,6 and botulinum toxin injection.

TREATMENT OF OUR PATIENT

In our patient, an orthopedic evaluation revealed cervicothoracic scoliosis. He underwent 6 months of conservative treatment under the care of his family physician and a dermatologist. Treatment consisted of exercise and rehabilitation for his scoliosis, and daily application of topical mometasone. The pain and itch gradual improved.

- Pérez-Pérez LC. General features and treatment of notalgia paresthetica. Skinmed 2011; 9:353–358.

- Fleischer AB, Meade TJ, Fleischer AB. Notalgia paresthetica: successful treatment with exercises. Acta Derm Venereol 2011; 91:356–357.

- Wallengren J, Klinker M. Successful treatment of notalgia paresthetica with topical capsaicin: vehicle-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32:287–289.

- Savk O, Savk E. Investigation of spinal pathology in notalgia paresthetica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1085–1087.

- Raison-Peyron N, Meunier L, Acevedo M, Meynadier J. Notalgia paresthetica: clinical, physiopathological and therapeutic aspects. A study of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999; 12:215–221.

- Pérez-Pérez L, Allegue F, Fabeiro JM, Caeiro JL, Zulaica A. Notalgia paresthesica successfully treated with narrow-band UVB: report of five cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24:730–732.

A 47-year-old man had had a chronic itch on his back for 2 years. He had no history of trauma to the site, nor did he recall applying topical products to that area.

He was otherwise healthy. He worked as an electrician and said he occasionally experienced cervical and back pain while working.

An examination revealed two grayish-brown ovoid patches on the upper back, each 5 cm to 7 cm in diameter (Figure 1).

DIAGNOSIS: NOTALGIA PARESTHETICA

Chronic, brown-gray, itching patches on the back in an adult patient are characteristic of notalgia paresthetica.

Conditions that may be included in the differential diagnosis but that do not match the presentation in this patient include the following:

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis, which may exhibit several morphologies, but itching would be unusual

- Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus, characterized by scarring and atrophic plaques, but mainly on the face and scalp

- Contact dermatitis, an itchy eczematous condition, characterized by scaly erythematous plaques

- Lichen amyloidosis, a variant of cutaneous amyloidosis characterized by the deposition of amyloid or amyloid-like proteins in the dermis, resulting in red-brown hyperkeratotic lichenoid papules, usually on the pretibial surfaces.

CAUSES AND MANAGEMENT

Notalgia paresthetica is a neuropathic syndrome of the skin of the middle of the back characterized by localized pruritus.1–3 Although common, it often goes undiagnosed.1,3,4 It tends to be chronic, with periodic remissions and exacerbations.

Notalgia paresthetica is thought to be a sensory neuropathy and may result from compression of the posterior rami of spinal nerve segments T2 to T6. Slight degenerative changes are often but not always observed, and their clinical significance is uncertain.1,2,4 The condition affects people of all races and both sexes, usually adults ages 40 to 80.

Clinically, it presents as localized pruritus on the back, usually within the dermatomes T2 to T6.5 Examination reveals a hyperpigmented patch, sometimes with excoriations.5

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings. Laboratory tests are not useful. Imaging is not needed, but magnetic resonance imaging and evaluation by an orthopedic surgeon are appropriate when there is chronic focal pain. Skin biopsy is usually not necessary, although it may be useful in some patients to exclude other conditions. When biopsy is done, macular amyloidosis or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is seen.

Treatment is difficult. Topical steroids and oral antihistamines are usually ineffective,5 but topical capsaicin may provide temporary relief.3 The most recommended treatment in patients with notalgia paresthetica and underlying spinal disease is evaluation and conservative management of the spinal disease, including progressive exercise and rehabilitation.2 Other therapies include oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, phototherapy,6 and botulinum toxin injection.

TREATMENT OF OUR PATIENT

In our patient, an orthopedic evaluation revealed cervicothoracic scoliosis. He underwent 6 months of conservative treatment under the care of his family physician and a dermatologist. Treatment consisted of exercise and rehabilitation for his scoliosis, and daily application of topical mometasone. The pain and itch gradual improved.

A 47-year-old man had had a chronic itch on his back for 2 years. He had no history of trauma to the site, nor did he recall applying topical products to that area.

He was otherwise healthy. He worked as an electrician and said he occasionally experienced cervical and back pain while working.

An examination revealed two grayish-brown ovoid patches on the upper back, each 5 cm to 7 cm in diameter (Figure 1).

DIAGNOSIS: NOTALGIA PARESTHETICA

Chronic, brown-gray, itching patches on the back in an adult patient are characteristic of notalgia paresthetica.

Conditions that may be included in the differential diagnosis but that do not match the presentation in this patient include the following:

- Cutaneous sarcoidosis, which may exhibit several morphologies, but itching would be unusual

- Chronic discoid lupus erythematosus, characterized by scarring and atrophic plaques, but mainly on the face and scalp

- Contact dermatitis, an itchy eczematous condition, characterized by scaly erythematous plaques

- Lichen amyloidosis, a variant of cutaneous amyloidosis characterized by the deposition of amyloid or amyloid-like proteins in the dermis, resulting in red-brown hyperkeratotic lichenoid papules, usually on the pretibial surfaces.

CAUSES AND MANAGEMENT

Notalgia paresthetica is a neuropathic syndrome of the skin of the middle of the back characterized by localized pruritus.1–3 Although common, it often goes undiagnosed.1,3,4 It tends to be chronic, with periodic remissions and exacerbations.

Notalgia paresthetica is thought to be a sensory neuropathy and may result from compression of the posterior rami of spinal nerve segments T2 to T6. Slight degenerative changes are often but not always observed, and their clinical significance is uncertain.1,2,4 The condition affects people of all races and both sexes, usually adults ages 40 to 80.

Clinically, it presents as localized pruritus on the back, usually within the dermatomes T2 to T6.5 Examination reveals a hyperpigmented patch, sometimes with excoriations.5

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings. Laboratory tests are not useful. Imaging is not needed, but magnetic resonance imaging and evaluation by an orthopedic surgeon are appropriate when there is chronic focal pain. Skin biopsy is usually not necessary, although it may be useful in some patients to exclude other conditions. When biopsy is done, macular amyloidosis or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is seen.

Treatment is difficult. Topical steroids and oral antihistamines are usually ineffective,5 but topical capsaicin may provide temporary relief.3 The most recommended treatment in patients with notalgia paresthetica and underlying spinal disease is evaluation and conservative management of the spinal disease, including progressive exercise and rehabilitation.2 Other therapies include oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, phototherapy,6 and botulinum toxin injection.

TREATMENT OF OUR PATIENT

In our patient, an orthopedic evaluation revealed cervicothoracic scoliosis. He underwent 6 months of conservative treatment under the care of his family physician and a dermatologist. Treatment consisted of exercise and rehabilitation for his scoliosis, and daily application of topical mometasone. The pain and itch gradual improved.

- Pérez-Pérez LC. General features and treatment of notalgia paresthetica. Skinmed 2011; 9:353–358.

- Fleischer AB, Meade TJ, Fleischer AB. Notalgia paresthetica: successful treatment with exercises. Acta Derm Venereol 2011; 91:356–357.

- Wallengren J, Klinker M. Successful treatment of notalgia paresthetica with topical capsaicin: vehicle-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32:287–289.

- Savk O, Savk E. Investigation of spinal pathology in notalgia paresthetica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1085–1087.

- Raison-Peyron N, Meunier L, Acevedo M, Meynadier J. Notalgia paresthetica: clinical, physiopathological and therapeutic aspects. A study of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999; 12:215–221.

- Pérez-Pérez L, Allegue F, Fabeiro JM, Caeiro JL, Zulaica A. Notalgia paresthesica successfully treated with narrow-band UVB: report of five cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24:730–732.

- Pérez-Pérez LC. General features and treatment of notalgia paresthetica. Skinmed 2011; 9:353–358.

- Fleischer AB, Meade TJ, Fleischer AB. Notalgia paresthetica: successful treatment with exercises. Acta Derm Venereol 2011; 91:356–357.

- Wallengren J, Klinker M. Successful treatment of notalgia paresthetica with topical capsaicin: vehicle-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995; 32:287–289.

- Savk O, Savk E. Investigation of spinal pathology in notalgia paresthetica. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:1085–1087.

- Raison-Peyron N, Meunier L, Acevedo M, Meynadier J. Notalgia paresthetica: clinical, physiopathological and therapeutic aspects. A study of 12 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1999; 12:215–221.

- Pérez-Pérez L, Allegue F, Fabeiro JM, Caeiro JL, Zulaica A. Notalgia paresthesica successfully treated with narrow-band UVB: report of five cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2010; 24:730–732.

Which lower-extremity DVTs should be removed early?

Early thrombus removal for lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is at present only modestly supported by evidence and so remains controversial. It is largely aimed at preventing postthrombotic syndrome.

The decision to pursue early thrombus removal demands weighing the patient’s risk of postthrombotic syndrome against the risks and costs associated with thrombolysis and thrombectomy, such as bleeding complications. In the final analysis, this remains a subjective decision.

With these caveats in mind, the best candidate for early thrombus removal is a young patient with iliofemoral DVT with symptoms lasting fewer than 14 days.

POSTTHROMBOTIC SYNDROME IS COMMON

Anticoagulation with heparin and warfarin is the mainstay of DVT therapy. Indeed, the safety of this therapy and its effectiveness in reducing thrombus propagation and DVT recurrence are well established. Neither heparin nor warfarin, however, actively reduces the thrombus burden. Rather, both prevent the clot from propagating while it is, hopefully, gradually reabsorbed through endogenous mechanisms.

Up to 50% of DVT patients develop postthrombotic syndrome. A variety of mechanisms are involved, including persistent obstructive thrombosis and valvular injury.1 But much remains unknown about the etiology, and some patients develop the condition in the absence of abnormalities on objective testing.

Symptoms of postthrombotic syndrome can range from mild heaviness, edema, erythema, and cramping in the affected limb to debilitating pain with classic signs of venous hypertension (eg, venous ectasia and ulcers). It accounts for significant health care costs and has a detrimental effect on quality of life.1 Thus, there has been interest in early thrombus removal as initial therapy for DVT.

THROMBUS REMOVAL

Venous clots can be removed with open surgery or, more typically, with percutaneous catheter-based thrombolysis and thrombectomy devices that use high-velocity saline jets, ultrasonic energy, or wire oscillation to mechanically fragment the venous clot. All of these mechanisms help with drug delivery and pose a minimal risk of pulmonary embolism.

Evidence is weak

Patients with DVT of the iliac venous system or common femoral vein are at highest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Therefore, the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum have issued a grade 2C (ie, weak) recommendation in favor of early thrombus removal in patients with a first-time episode of iliofemoral DVT with fewer than 14 days of symptoms.2 Moreover, patients must have a low risk of bleeding complications, be ambulatory, and have reasonable life expectancy.

The recommendation is buttressed by a Cochrane meta-analysis that included 101 patients.3 It concluded that there was a significant decrement in the development of postthrombotic syndrome with thrombolysis (but without mechanical thrombectomy) compared with standard therapy: the rate was 48% (29/61) with thrombolysis, and 65% (26/40) with standard therapy.3

More recently, the Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis Versus Standard Treatment for Acute Iliofemoral Deep Vein Thrombosis (CaVenT) study, a randomized prospective trial in 189 patients, demonstrated a lower rate of postthrombotic syndrome at 24 months and increased iliofemoral patency at 6 months with catheter-directed thrombolysis with alteplase (41.1% and 65.9%) vs anticoagulation with heparin and warfarin alone (55.6% and 47.4%).4

The Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal With Adjunctive Catheter-directed Thrombolysis (ATTRACT) trial is an ongoing prospective randomized multicenter trial of the effect of thrombolysis on postthrombotic syndrome that also hopes to clarify the relative benefits of different methods of pharmacomechanical clot removal.

While CaVenT has not been criticized extensively in the literature, other studies supporting early intervention for iliofemoral venous thrombosis generally have been noted to have a number of shortcomings, including a lack of randomization, and consequent bias, and the use of surrogate end points instead of a direct assessment of postthrombotic syndrome.

Reflecting the weakness of the evidence, the American College of Chest Physicians has issued a grade 2C recommendation against catheter-directed thrombolysis and against thrombectomy in favor of anticoagulant therapy.5

A subjective, case-by-case decision

The decision on standard vs interventional therapy must be made case by case. For example, thrombus removal may be more appropriate for a physically active young patient who is more likely to be impaired by postthrombotic syndrome, whereas standard warfarin therapy may be preferable for a sedentary patient. We are also more inclined to offer thrombus removal to patients who have worse symptoms.

Complicating the issue, many patients present with a mix of variables that support and oppose intervention—eg, a moderately active elderly patient with an unclear life expectancy and a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. At present, there is no way to quantitatively evaluate the risks and rewards of thrombus removal, and the final decision is essentially subjective.

Additional facts warranting consideration include the possibility that thrombolysis may require several days of therapy with daily venography for evaluation. Monitoring in the intensive care unit is normally required during the period of thrombolysis. Patients should be apprised of these elements of therapy beforehand; obviously, those who are unwilling to comply are not candidates.

Not a substitute for anticoagulation

It is important to recognize that thrombus removal is not a substitute for standard heparin-warfarin anticoagulation, which must also be prescribed.5 Thus, patients who cannot tolerate standard post-DVT anticoagulation should not undergo thrombus removal. Furthermore, the current evidence supports the use of standard anticoagulation over early thrombus removal of DVTs that are more distal in the lower extremity, such as those in the popliteal vein.5

PHLEGMASIA CERULEA DOLENS IS A SPECIAL CASE

Phlegmasia cerulea dolens—acute venous outflow obstruction associated with edema, cyanosis, and pain that in the worst cases may lead to shock, limb loss, and death—constitutes a special case. Although we lack robust supporting evidence, phlegmasia is a commonly accepted indication for early thrombus removal as a means of limb salvage.2,6

- Kahn SR. The post thrombotic syndrome. Thromb Res 2011; 127 (suppl 3):S89–S92.

- Meissner MH, Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Venous Forum. Early thrombus removal strategies for acute deep venous thrombosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2012; 55:1449–1462.

- Watson LI, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 4:CD002783.

- Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379:31–38.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141 (suppl 2):e419S–e494S.

- Patterson BO, Hinchliffe R, Loftus IM, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Indications for catheter-directed thrombolysis in the management of acute proximal deep venous thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010; 30:669–674.

Early thrombus removal for lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is at present only modestly supported by evidence and so remains controversial. It is largely aimed at preventing postthrombotic syndrome.

The decision to pursue early thrombus removal demands weighing the patient’s risk of postthrombotic syndrome against the risks and costs associated with thrombolysis and thrombectomy, such as bleeding complications. In the final analysis, this remains a subjective decision.

With these caveats in mind, the best candidate for early thrombus removal is a young patient with iliofemoral DVT with symptoms lasting fewer than 14 days.

POSTTHROMBOTIC SYNDROME IS COMMON

Anticoagulation with heparin and warfarin is the mainstay of DVT therapy. Indeed, the safety of this therapy and its effectiveness in reducing thrombus propagation and DVT recurrence are well established. Neither heparin nor warfarin, however, actively reduces the thrombus burden. Rather, both prevent the clot from propagating while it is, hopefully, gradually reabsorbed through endogenous mechanisms.

Up to 50% of DVT patients develop postthrombotic syndrome. A variety of mechanisms are involved, including persistent obstructive thrombosis and valvular injury.1 But much remains unknown about the etiology, and some patients develop the condition in the absence of abnormalities on objective testing.

Symptoms of postthrombotic syndrome can range from mild heaviness, edema, erythema, and cramping in the affected limb to debilitating pain with classic signs of venous hypertension (eg, venous ectasia and ulcers). It accounts for significant health care costs and has a detrimental effect on quality of life.1 Thus, there has been interest in early thrombus removal as initial therapy for DVT.

THROMBUS REMOVAL

Venous clots can be removed with open surgery or, more typically, with percutaneous catheter-based thrombolysis and thrombectomy devices that use high-velocity saline jets, ultrasonic energy, or wire oscillation to mechanically fragment the venous clot. All of these mechanisms help with drug delivery and pose a minimal risk of pulmonary embolism.

Evidence is weak

Patients with DVT of the iliac venous system or common femoral vein are at highest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Therefore, the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum have issued a grade 2C (ie, weak) recommendation in favor of early thrombus removal in patients with a first-time episode of iliofemoral DVT with fewer than 14 days of symptoms.2 Moreover, patients must have a low risk of bleeding complications, be ambulatory, and have reasonable life expectancy.

The recommendation is buttressed by a Cochrane meta-analysis that included 101 patients.3 It concluded that there was a significant decrement in the development of postthrombotic syndrome with thrombolysis (but without mechanical thrombectomy) compared with standard therapy: the rate was 48% (29/61) with thrombolysis, and 65% (26/40) with standard therapy.3

More recently, the Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis Versus Standard Treatment for Acute Iliofemoral Deep Vein Thrombosis (CaVenT) study, a randomized prospective trial in 189 patients, demonstrated a lower rate of postthrombotic syndrome at 24 months and increased iliofemoral patency at 6 months with catheter-directed thrombolysis with alteplase (41.1% and 65.9%) vs anticoagulation with heparin and warfarin alone (55.6% and 47.4%).4

The Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal With Adjunctive Catheter-directed Thrombolysis (ATTRACT) trial is an ongoing prospective randomized multicenter trial of the effect of thrombolysis on postthrombotic syndrome that also hopes to clarify the relative benefits of different methods of pharmacomechanical clot removal.

While CaVenT has not been criticized extensively in the literature, other studies supporting early intervention for iliofemoral venous thrombosis generally have been noted to have a number of shortcomings, including a lack of randomization, and consequent bias, and the use of surrogate end points instead of a direct assessment of postthrombotic syndrome.

Reflecting the weakness of the evidence, the American College of Chest Physicians has issued a grade 2C recommendation against catheter-directed thrombolysis and against thrombectomy in favor of anticoagulant therapy.5

A subjective, case-by-case decision

The decision on standard vs interventional therapy must be made case by case. For example, thrombus removal may be more appropriate for a physically active young patient who is more likely to be impaired by postthrombotic syndrome, whereas standard warfarin therapy may be preferable for a sedentary patient. We are also more inclined to offer thrombus removal to patients who have worse symptoms.

Complicating the issue, many patients present with a mix of variables that support and oppose intervention—eg, a moderately active elderly patient with an unclear life expectancy and a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. At present, there is no way to quantitatively evaluate the risks and rewards of thrombus removal, and the final decision is essentially subjective.

Additional facts warranting consideration include the possibility that thrombolysis may require several days of therapy with daily venography for evaluation. Monitoring in the intensive care unit is normally required during the period of thrombolysis. Patients should be apprised of these elements of therapy beforehand; obviously, those who are unwilling to comply are not candidates.

Not a substitute for anticoagulation

It is important to recognize that thrombus removal is not a substitute for standard heparin-warfarin anticoagulation, which must also be prescribed.5 Thus, patients who cannot tolerate standard post-DVT anticoagulation should not undergo thrombus removal. Furthermore, the current evidence supports the use of standard anticoagulation over early thrombus removal of DVTs that are more distal in the lower extremity, such as those in the popliteal vein.5

PHLEGMASIA CERULEA DOLENS IS A SPECIAL CASE

Phlegmasia cerulea dolens—acute venous outflow obstruction associated with edema, cyanosis, and pain that in the worst cases may lead to shock, limb loss, and death—constitutes a special case. Although we lack robust supporting evidence, phlegmasia is a commonly accepted indication for early thrombus removal as a means of limb salvage.2,6

Early thrombus removal for lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is at present only modestly supported by evidence and so remains controversial. It is largely aimed at preventing postthrombotic syndrome.

The decision to pursue early thrombus removal demands weighing the patient’s risk of postthrombotic syndrome against the risks and costs associated with thrombolysis and thrombectomy, such as bleeding complications. In the final analysis, this remains a subjective decision.

With these caveats in mind, the best candidate for early thrombus removal is a young patient with iliofemoral DVT with symptoms lasting fewer than 14 days.

POSTTHROMBOTIC SYNDROME IS COMMON

Anticoagulation with heparin and warfarin is the mainstay of DVT therapy. Indeed, the safety of this therapy and its effectiveness in reducing thrombus propagation and DVT recurrence are well established. Neither heparin nor warfarin, however, actively reduces the thrombus burden. Rather, both prevent the clot from propagating while it is, hopefully, gradually reabsorbed through endogenous mechanisms.

Up to 50% of DVT patients develop postthrombotic syndrome. A variety of mechanisms are involved, including persistent obstructive thrombosis and valvular injury.1 But much remains unknown about the etiology, and some patients develop the condition in the absence of abnormalities on objective testing.

Symptoms of postthrombotic syndrome can range from mild heaviness, edema, erythema, and cramping in the affected limb to debilitating pain with classic signs of venous hypertension (eg, venous ectasia and ulcers). It accounts for significant health care costs and has a detrimental effect on quality of life.1 Thus, there has been interest in early thrombus removal as initial therapy for DVT.

THROMBUS REMOVAL

Venous clots can be removed with open surgery or, more typically, with percutaneous catheter-based thrombolysis and thrombectomy devices that use high-velocity saline jets, ultrasonic energy, or wire oscillation to mechanically fragment the venous clot. All of these mechanisms help with drug delivery and pose a minimal risk of pulmonary embolism.

Evidence is weak

Patients with DVT of the iliac venous system or common femoral vein are at highest risk of postthrombotic syndrome. Therefore, the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum have issued a grade 2C (ie, weak) recommendation in favor of early thrombus removal in patients with a first-time episode of iliofemoral DVT with fewer than 14 days of symptoms.2 Moreover, patients must have a low risk of bleeding complications, be ambulatory, and have reasonable life expectancy.

The recommendation is buttressed by a Cochrane meta-analysis that included 101 patients.3 It concluded that there was a significant decrement in the development of postthrombotic syndrome with thrombolysis (but without mechanical thrombectomy) compared with standard therapy: the rate was 48% (29/61) with thrombolysis, and 65% (26/40) with standard therapy.3

More recently, the Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis Versus Standard Treatment for Acute Iliofemoral Deep Vein Thrombosis (CaVenT) study, a randomized prospective trial in 189 patients, demonstrated a lower rate of postthrombotic syndrome at 24 months and increased iliofemoral patency at 6 months with catheter-directed thrombolysis with alteplase (41.1% and 65.9%) vs anticoagulation with heparin and warfarin alone (55.6% and 47.4%).4

The Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal With Adjunctive Catheter-directed Thrombolysis (ATTRACT) trial is an ongoing prospective randomized multicenter trial of the effect of thrombolysis on postthrombotic syndrome that also hopes to clarify the relative benefits of different methods of pharmacomechanical clot removal.

While CaVenT has not been criticized extensively in the literature, other studies supporting early intervention for iliofemoral venous thrombosis generally have been noted to have a number of shortcomings, including a lack of randomization, and consequent bias, and the use of surrogate end points instead of a direct assessment of postthrombotic syndrome.

Reflecting the weakness of the evidence, the American College of Chest Physicians has issued a grade 2C recommendation against catheter-directed thrombolysis and against thrombectomy in favor of anticoagulant therapy.5

A subjective, case-by-case decision

The decision on standard vs interventional therapy must be made case by case. For example, thrombus removal may be more appropriate for a physically active young patient who is more likely to be impaired by postthrombotic syndrome, whereas standard warfarin therapy may be preferable for a sedentary patient. We are also more inclined to offer thrombus removal to patients who have worse symptoms.

Complicating the issue, many patients present with a mix of variables that support and oppose intervention—eg, a moderately active elderly patient with an unclear life expectancy and a history of gastrointestinal bleeding. At present, there is no way to quantitatively evaluate the risks and rewards of thrombus removal, and the final decision is essentially subjective.

Additional facts warranting consideration include the possibility that thrombolysis may require several days of therapy with daily venography for evaluation. Monitoring in the intensive care unit is normally required during the period of thrombolysis. Patients should be apprised of these elements of therapy beforehand; obviously, those who are unwilling to comply are not candidates.

Not a substitute for anticoagulation

It is important to recognize that thrombus removal is not a substitute for standard heparin-warfarin anticoagulation, which must also be prescribed.5 Thus, patients who cannot tolerate standard post-DVT anticoagulation should not undergo thrombus removal. Furthermore, the current evidence supports the use of standard anticoagulation over early thrombus removal of DVTs that are more distal in the lower extremity, such as those in the popliteal vein.5

PHLEGMASIA CERULEA DOLENS IS A SPECIAL CASE

Phlegmasia cerulea dolens—acute venous outflow obstruction associated with edema, cyanosis, and pain that in the worst cases may lead to shock, limb loss, and death—constitutes a special case. Although we lack robust supporting evidence, phlegmasia is a commonly accepted indication for early thrombus removal as a means of limb salvage.2,6

- Kahn SR. The post thrombotic syndrome. Thromb Res 2011; 127 (suppl 3):S89–S92.

- Meissner MH, Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Venous Forum. Early thrombus removal strategies for acute deep venous thrombosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2012; 55:1449–1462.

- Watson LI, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 4:CD002783.

- Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379:31–38.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141 (suppl 2):e419S–e494S.

- Patterson BO, Hinchliffe R, Loftus IM, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Indications for catheter-directed thrombolysis in the management of acute proximal deep venous thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010; 30:669–674.

- Kahn SR. The post thrombotic syndrome. Thromb Res 2011; 127 (suppl 3):S89–S92.

- Meissner MH, Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Venous Forum. Early thrombus removal strategies for acute deep venous thrombosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2012; 55:1449–1462.

- Watson LI, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 4:CD002783.

- Enden T, Haig Y, Kløw NE, et al; CaVenT Study Group. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379:31–38.

- Kearon C, Akl EA, Comerota AJ, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012; 141 (suppl 2):e419S–e494S.

- Patterson BO, Hinchliffe R, Loftus IM, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Indications for catheter-directed thrombolysis in the management of acute proximal deep venous thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2010; 30:669–674.

Azithromycin and risk of sudden cardiac death: Guilty as charged or falsely accused?

A March 2013 warning by the US Food and Drug Administration that azithromycin (Zithromax, Zmax, Z-pak) may increase the risk of sudden cardiac death does not mean we must abandon using it. We should, however, try to determine if our patients have cardiovascular risk factors for this extreme side effect and take appropriate precautions.

AZITHROMYCIN: THE SAFEST OF THE MACROLIDES?

Azithromycin, a broad-spectrum macrolide antibiotic, is used to treat or prevent a range of common bacterial infections, including upper and lower respiratory tract infections and certain sexually transmitted diseases.

In terms of overall toxicity, azithromycin has been considered the safest of the macrolides, as it neither undergoes CYP3A4 metabolism nor inhibits CYP3A4 to any clinically meaningful degree, and therefore does not interfere with the array of commonly used medications that undergo CYP3A4 metabolism.

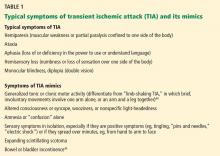

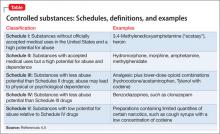

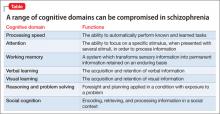

Also, in vitro, azithromycin shows only limited blockade of the potassium channel hERG. This channel is critically involved in cardiomyocyte repolarization, and if it is blocked or otherwise malfunctioning, the result can be a prolonged QT interval, ventricular arrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death.1–4 Therefore, lack of blockade, as reflected by a high inhibitory concentration (Table 1), boded well for the safety of azithromycin in terms of QT liability. However, we should be cautious in interpreting in vitro data.

With its broad antibiotic spectrum and perceived favorable safety profile, azithromycin has become one of the top 15 most prescribed drugs and the best-selling antibiotic in the United States, accounting for 55.4 million prescriptions in 2012, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

THE FDA RECEIVES 203 REPORTS OF ADVERSE EVENTS IN 8 YEARS

However, beginning with a report of azithromycin-triggered torsades de pointes in 2001,5 a growing body of evidence, derived from postmarketing surveillance, has linked azithromycin to cardiac arrhythmias such as pronounced QT interval prolongation and associated torsades de pointes (which can progress to life-threatening ventricular fibrillation). Other, closely related macrolides such as clarithromycin and erythromycin are also linked to these effects.

Furthermore, in the 8-year period from 2004 to 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) received a total of 203 reports of azithromycin-associated QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, ventricular arrhythmia, or, in 65 cases, sudden cardiac death (Table 1).6

At face value, the number of FAERS reports appears to be similar between the various macrolide antibiotics. However, it is important to remember that these drugs differ substantially in the number of prescriptions written for them, with azithromycin being prescribed more often. Also, the FAERS numbers are subject to a number of well-known limitations such as confounding variables, uneven quality and completeness of reports, duplication, and underreporting. These limitations preclude the use of such adverse reporting databases in calculating and thereby comparing the true incidence of adverse events associated with the various macrolide antibiotics.6–9

RAY ET AL FIND A HIGHER RISK OF CARDIOVASCULAR DEATH

Despite these inherent flaws, initial postmarketing surveillance reports cast enough doubt on the long-standing notion that azithromycin is the safest macrolide antibiotic to prompt Ray et al10 to assess its safety in an observational, nonrandomized study of people enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program.

They found that, over the typical 5 days of therapy, people taking azithromycin had a rate of cardiovascular death 2.88 times higher than in people taking no antibiotic, and 2.49 times higher than in people taking amoxicillin (Table 2).

However, the absolute excess risk compared with amoxicillin varied considerably according to baseline risk score for cardiovascular disease, with 1 excess cardiovascular death per 4,100 in the highest-risk decile compared with 1 excess cardiovascular death per 100,000 in the lowest-risk decile.10,11

Moreover, the increase in deaths did not persist after the 5 days of therapy. This time-limited pattern directly correlated with expected peak azithromycin plasma levels during a standard 5-day course.

Ray et al used appropriate analytic methods to attempt to correct for any confounding bias intrinsic to the observational, nonrandomized study design. Nevertheless, the patients were Medicaid beneficiaries, who have a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions and higher mortality rates than the general population. Therefore, legitimate questions were raised about whether the results of the study could be generalized to populations with substantially lower baseline risk of cardiovascular disease and if differences in the baseline characteristics of the treatment groups were adequately controlled.12,13

THE FDA REVISES AZITHROMYCIN’S WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

The striking observations by Ray et al,10 coupled with the concerns raised by postmarketing surveillance reports, compelled the FDA to review the labels of azithromycin and other macrolide antibiotics.

Ultimately, the FDA opted to revise the “warning and precautions” section of the azithromycin drug label to include a warning about the potential risk of fatal arrhythmias, specifically QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes. In a March 2013 safety announcement, it also urged health care professionals to use caution when prescribing azithromycin to patients known to have risk factors for drug-related arrhythmias, including congenital long QT syndrome, acquired QT interval prolongation, hypokalemia, hypomagnesia, bradycardia, and concurrent use of other medications known to prolong the QT interval, specifically the class IA (eg, quinidine and procainamide) and class III (eg, amiodarone, sotalol, and dofetilide) antiarrhythmics.

SVANSTRÖM ET AL FIND NO INCREASED RISK

However, just when the medical community appeared ready to accept that azithromycin may not be as safe as we thought it was, a large prospective study by Svanström et al, published in early May 2013, found no increased risk of cardiovascular death associated with azithromycin (Table 2).14

The patients were a representative population of young to middle-aged Danish adults at low baseline risk of underlying cardiovascular disease.

Interestingly, Svanström et al were careful to point out that their study was only powered to rule out a moderate-to-high (> 55%) increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular death. Furthermore, profound differences existed in the baseline risk of death and cardiovascular risk factors between their patients and the Tennessee Medicaid patients studied by Ray et al.14 Therefore, the authors suggested that their study complements rather than contradicts the study by Ray et al. They attributed the differences in the findings to treatment-effect heterogeneity, in which the risk of azithromycin-associated cardiovascular mortality is largely limited to high-risk patients, namely those with multiple preexisting cardiovascular risk factors.14

ACC/AHA RECOMMENDATION: IDENTIFY THOSE AT RISK

Collectively, the data reviewed above provide compelling evidence that azithromycin is not completely free of the QT-prolonging and torsadogenic effects that have long been associated with other macrolide antibiotics. However, the findings from both the study by Ray et al and that of Svanström et al suggest that preexisting cardiovascular risk factors play a prominent role in determining the incidence of azithromycin-associated cardiovascular death in a given population (Table 2).10,14

These findings should prompt physicians to carefully reassess the risks and benefits of azithromycin use in their clinical practices. They also reinforce a recent call by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) to better identify, early on, patients at risk of drug-induced ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death and to subsequently improve how these patients are monitored when the use of QT-prolonging and torsadogenic drugs is medically necessary.15

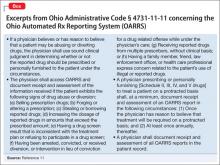

AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD FLAGS QTc ≥ 500 MS

On the heels of these AHA/ACC suggestions, our hospital has adopted an institution-wide QT alert system. Here, the electronic medical record system (Centricity EMR; GE Healthcare) uses a proprietary algorithm to detect and electronically alert ordering physicians when a patient has a prolonged QT interval, and gives information about the potential clinical significance of this electrocardiographic finding.16 Physicians also receive a warning when ordering QT-prolonging drugs in patients at risk.

This system is still in its infancy, but it has already confirmed that a prolonged QT interval (QTc ≥ 500 ms) is a powerful predictor of death from any cause and has demonstrated that mortality rates in those with prolonged QT intervals increase in a dose-dependent fashion with the patient’s number of modifiable risk factors (eg, electrolyte disturbances or QT-prolonging medications) and nonmodifiable risk factors (eg, genetic disposition, female sex, structural heart disease, diabetes mellitus).16 We have also found evidence that modifiable risk factors may have a more pronounced effect on mortality risk than non-modifiable risk factors.16

These findings suggest that information technology-based QT alert systems may one day provide physicians with an important tool to efficiently identify and possibly even modify the risk of cardiovascular death in patients at high risk, for example, by correcting electrolyte abnormalities or reducing the burden of QT-prolonging medications.

CONSIDER RISK OF QT PROLONGATION WHEN PRESCRIBING AZITHROMYCIN

For most institutions and clinical practices, such electronic QT alert systems are still years if not decades away. However, in light of the information summarized above, all physicians should begin considering risk factors for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes (summarized in Table 3) and weighing the risks and benefits of prescribing azithromycin vs alternative antibiotics with minimal QT liability. This should be relatively simple to do. Things to keep in mind:

- Although azithromycin may increase the relative risk of a cardiovascular event, for most otherwise-healthy patients, the absolute risk is miniscule.

- In a patient at risk (eg, with baseline QT prolongation or multiple risk factors for it), if azithromycin or another QT-prolonging antibiotic such as a macrolide or fluoroquinolone is medically necessary due to preferential bacterial susceptibility or patient allergies, every effort should be made to correct modifiable risk factors (eg, electrolyte abnormalities) and, if possible, to avoid polypharmacy with multiple QT-prolonging drugs.

- For patients who have multiple risk factors for QT prolongation in whom treatment with a known QT-prolonging medication is still deemed in the patient’s best interest, strong consideration should be given to inpatient administration and monitoring until the treatment has been completed.

With careful consideration of modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors as well as a little extra caution when prescribing potential QT-prolonging medications such as azithromycin, the clinical benefit of these often-advantageous medications can be maximized and the incidence of these tragic but rare drug-induced sudden cardiac deaths can be reduced.

- Hopkins S. Clinical toleration and safety of azithromycin. Am J Med 1991; 91:40S–45S.

- Milberg P, Eckardt L, Bruns HJ, et al. Divergent proarrhythmic potential of macrolide antibiotics despite similar QT prolongation: fast phase 3 repolarization prevents early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303:218–225.

- Ioannidis JP, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Chew P, Lau J. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the comparative efficacy and safety of azithromycin against other antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001; 48:677–689.

- Owens RC, Nolin TD. Antimicrobial-associated QT interval prolongation: pointes of interest. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1603–1611.

- Arellano-Rodrigo E, García A, Mont L, Roqué M. Torsade de pointes and cardiorespiratory arrest induced by azithromycin in a patient with congenital long QT syndrome. (Article in Spanish.) Med Clin (Barc) 2001; 117:118–119.

- Raschi E, Poluzzi E, Koci A, Moretti U, Sturkenboom M, De Ponti F. Macrolides and torsadogenic risk: emerging issues from the fda pharmacovigilance database. J Pharmacovigilance 2013; 1:104.

- Shaffer D, Singer S, Korvick J, Honig P. Concomitant risk factors in reports of torsades de pointes associated with macrolide use: review of the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:197–200.

- Stephenson WP, Hauben M. Data mining for signals in spontaneous reporting databases: proceed with caution. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16:359–365.

- Bate A, Evans SJ. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009; 18:427–436.

- Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1881–1890.

- Mosholder AD, Mathew J, Alexander JJ, Smith H, Nambiar S. Cardiovascular risks with azithromycin and other antibacterial drugs. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1665–1668.

- Louie R. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:774–775.

- Koga T, Imaoka H. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:774–775.

- Svanström H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1704–1712.

- Drew BJ, Ackerman MJ, Funk M, et al; American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Prevention of torsade de pointes in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2010; 121:1047–1060.

- Haugaa KH, Bos JM, Tarrell RF, Morlan BW, Caraballo PJ, Ackerman MJ. Institution-wide QT alert system identifies patients with a high risk of mortality. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88:315–325.

A March 2013 warning by the US Food and Drug Administration that azithromycin (Zithromax, Zmax, Z-pak) may increase the risk of sudden cardiac death does not mean we must abandon using it. We should, however, try to determine if our patients have cardiovascular risk factors for this extreme side effect and take appropriate precautions.

AZITHROMYCIN: THE SAFEST OF THE MACROLIDES?

Azithromycin, a broad-spectrum macrolide antibiotic, is used to treat or prevent a range of common bacterial infections, including upper and lower respiratory tract infections and certain sexually transmitted diseases.

In terms of overall toxicity, azithromycin has been considered the safest of the macrolides, as it neither undergoes CYP3A4 metabolism nor inhibits CYP3A4 to any clinically meaningful degree, and therefore does not interfere with the array of commonly used medications that undergo CYP3A4 metabolism.

Also, in vitro, azithromycin shows only limited blockade of the potassium channel hERG. This channel is critically involved in cardiomyocyte repolarization, and if it is blocked or otherwise malfunctioning, the result can be a prolonged QT interval, ventricular arrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death.1–4 Therefore, lack of blockade, as reflected by a high inhibitory concentration (Table 1), boded well for the safety of azithromycin in terms of QT liability. However, we should be cautious in interpreting in vitro data.

With its broad antibiotic spectrum and perceived favorable safety profile, azithromycin has become one of the top 15 most prescribed drugs and the best-selling antibiotic in the United States, accounting for 55.4 million prescriptions in 2012, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

THE FDA RECEIVES 203 REPORTS OF ADVERSE EVENTS IN 8 YEARS

However, beginning with a report of azithromycin-triggered torsades de pointes in 2001,5 a growing body of evidence, derived from postmarketing surveillance, has linked azithromycin to cardiac arrhythmias such as pronounced QT interval prolongation and associated torsades de pointes (which can progress to life-threatening ventricular fibrillation). Other, closely related macrolides such as clarithromycin and erythromycin are also linked to these effects.

Furthermore, in the 8-year period from 2004 to 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) received a total of 203 reports of azithromycin-associated QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, ventricular arrhythmia, or, in 65 cases, sudden cardiac death (Table 1).6

At face value, the number of FAERS reports appears to be similar between the various macrolide antibiotics. However, it is important to remember that these drugs differ substantially in the number of prescriptions written for them, with azithromycin being prescribed more often. Also, the FAERS numbers are subject to a number of well-known limitations such as confounding variables, uneven quality and completeness of reports, duplication, and underreporting. These limitations preclude the use of such adverse reporting databases in calculating and thereby comparing the true incidence of adverse events associated with the various macrolide antibiotics.6–9

RAY ET AL FIND A HIGHER RISK OF CARDIOVASCULAR DEATH

Despite these inherent flaws, initial postmarketing surveillance reports cast enough doubt on the long-standing notion that azithromycin is the safest macrolide antibiotic to prompt Ray et al10 to assess its safety in an observational, nonrandomized study of people enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program.

They found that, over the typical 5 days of therapy, people taking azithromycin had a rate of cardiovascular death 2.88 times higher than in people taking no antibiotic, and 2.49 times higher than in people taking amoxicillin (Table 2).

However, the absolute excess risk compared with amoxicillin varied considerably according to baseline risk score for cardiovascular disease, with 1 excess cardiovascular death per 4,100 in the highest-risk decile compared with 1 excess cardiovascular death per 100,000 in the lowest-risk decile.10,11

Moreover, the increase in deaths did not persist after the 5 days of therapy. This time-limited pattern directly correlated with expected peak azithromycin plasma levels during a standard 5-day course.

Ray et al used appropriate analytic methods to attempt to correct for any confounding bias intrinsic to the observational, nonrandomized study design. Nevertheless, the patients were Medicaid beneficiaries, who have a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions and higher mortality rates than the general population. Therefore, legitimate questions were raised about whether the results of the study could be generalized to populations with substantially lower baseline risk of cardiovascular disease and if differences in the baseline characteristics of the treatment groups were adequately controlled.12,13

THE FDA REVISES AZITHROMYCIN’S WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

The striking observations by Ray et al,10 coupled with the concerns raised by postmarketing surveillance reports, compelled the FDA to review the labels of azithromycin and other macrolide antibiotics.

Ultimately, the FDA opted to revise the “warning and precautions” section of the azithromycin drug label to include a warning about the potential risk of fatal arrhythmias, specifically QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes. In a March 2013 safety announcement, it also urged health care professionals to use caution when prescribing azithromycin to patients known to have risk factors for drug-related arrhythmias, including congenital long QT syndrome, acquired QT interval prolongation, hypokalemia, hypomagnesia, bradycardia, and concurrent use of other medications known to prolong the QT interval, specifically the class IA (eg, quinidine and procainamide) and class III (eg, amiodarone, sotalol, and dofetilide) antiarrhythmics.

SVANSTRÖM ET AL FIND NO INCREASED RISK

However, just when the medical community appeared ready to accept that azithromycin may not be as safe as we thought it was, a large prospective study by Svanström et al, published in early May 2013, found no increased risk of cardiovascular death associated with azithromycin (Table 2).14

The patients were a representative population of young to middle-aged Danish adults at low baseline risk of underlying cardiovascular disease.

Interestingly, Svanström et al were careful to point out that their study was only powered to rule out a moderate-to-high (> 55%) increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular death. Furthermore, profound differences existed in the baseline risk of death and cardiovascular risk factors between their patients and the Tennessee Medicaid patients studied by Ray et al.14 Therefore, the authors suggested that their study complements rather than contradicts the study by Ray et al. They attributed the differences in the findings to treatment-effect heterogeneity, in which the risk of azithromycin-associated cardiovascular mortality is largely limited to high-risk patients, namely those with multiple preexisting cardiovascular risk factors.14

ACC/AHA RECOMMENDATION: IDENTIFY THOSE AT RISK

Collectively, the data reviewed above provide compelling evidence that azithromycin is not completely free of the QT-prolonging and torsadogenic effects that have long been associated with other macrolide antibiotics. However, the findings from both the study by Ray et al and that of Svanström et al suggest that preexisting cardiovascular risk factors play a prominent role in determining the incidence of azithromycin-associated cardiovascular death in a given population (Table 2).10,14

These findings should prompt physicians to carefully reassess the risks and benefits of azithromycin use in their clinical practices. They also reinforce a recent call by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) to better identify, early on, patients at risk of drug-induced ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death and to subsequently improve how these patients are monitored when the use of QT-prolonging and torsadogenic drugs is medically necessary.15

AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD FLAGS QTc ≥ 500 MS

On the heels of these AHA/ACC suggestions, our hospital has adopted an institution-wide QT alert system. Here, the electronic medical record system (Centricity EMR; GE Healthcare) uses a proprietary algorithm to detect and electronically alert ordering physicians when a patient has a prolonged QT interval, and gives information about the potential clinical significance of this electrocardiographic finding.16 Physicians also receive a warning when ordering QT-prolonging drugs in patients at risk.

This system is still in its infancy, but it has already confirmed that a prolonged QT interval (QTc ≥ 500 ms) is a powerful predictor of death from any cause and has demonstrated that mortality rates in those with prolonged QT intervals increase in a dose-dependent fashion with the patient’s number of modifiable risk factors (eg, electrolyte disturbances or QT-prolonging medications) and nonmodifiable risk factors (eg, genetic disposition, female sex, structural heart disease, diabetes mellitus).16 We have also found evidence that modifiable risk factors may have a more pronounced effect on mortality risk than non-modifiable risk factors.16

These findings suggest that information technology-based QT alert systems may one day provide physicians with an important tool to efficiently identify and possibly even modify the risk of cardiovascular death in patients at high risk, for example, by correcting electrolyte abnormalities or reducing the burden of QT-prolonging medications.

CONSIDER RISK OF QT PROLONGATION WHEN PRESCRIBING AZITHROMYCIN

For most institutions and clinical practices, such electronic QT alert systems are still years if not decades away. However, in light of the information summarized above, all physicians should begin considering risk factors for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes (summarized in Table 3) and weighing the risks and benefits of prescribing azithromycin vs alternative antibiotics with minimal QT liability. This should be relatively simple to do. Things to keep in mind:

- Although azithromycin may increase the relative risk of a cardiovascular event, for most otherwise-healthy patients, the absolute risk is miniscule.

- In a patient at risk (eg, with baseline QT prolongation or multiple risk factors for it), if azithromycin or another QT-prolonging antibiotic such as a macrolide or fluoroquinolone is medically necessary due to preferential bacterial susceptibility or patient allergies, every effort should be made to correct modifiable risk factors (eg, electrolyte abnormalities) and, if possible, to avoid polypharmacy with multiple QT-prolonging drugs.

- For patients who have multiple risk factors for QT prolongation in whom treatment with a known QT-prolonging medication is still deemed in the patient’s best interest, strong consideration should be given to inpatient administration and monitoring until the treatment has been completed.

With careful consideration of modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors as well as a little extra caution when prescribing potential QT-prolonging medications such as azithromycin, the clinical benefit of these often-advantageous medications can be maximized and the incidence of these tragic but rare drug-induced sudden cardiac deaths can be reduced.

A March 2013 warning by the US Food and Drug Administration that azithromycin (Zithromax, Zmax, Z-pak) may increase the risk of sudden cardiac death does not mean we must abandon using it. We should, however, try to determine if our patients have cardiovascular risk factors for this extreme side effect and take appropriate precautions.

AZITHROMYCIN: THE SAFEST OF THE MACROLIDES?

Azithromycin, a broad-spectrum macrolide antibiotic, is used to treat or prevent a range of common bacterial infections, including upper and lower respiratory tract infections and certain sexually transmitted diseases.

In terms of overall toxicity, azithromycin has been considered the safest of the macrolides, as it neither undergoes CYP3A4 metabolism nor inhibits CYP3A4 to any clinically meaningful degree, and therefore does not interfere with the array of commonly used medications that undergo CYP3A4 metabolism.

Also, in vitro, azithromycin shows only limited blockade of the potassium channel hERG. This channel is critically involved in cardiomyocyte repolarization, and if it is blocked or otherwise malfunctioning, the result can be a prolonged QT interval, ventricular arrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death.1–4 Therefore, lack of blockade, as reflected by a high inhibitory concentration (Table 1), boded well for the safety of azithromycin in terms of QT liability. However, we should be cautious in interpreting in vitro data.

With its broad antibiotic spectrum and perceived favorable safety profile, azithromycin has become one of the top 15 most prescribed drugs and the best-selling antibiotic in the United States, accounting for 55.4 million prescriptions in 2012, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics.

THE FDA RECEIVES 203 REPORTS OF ADVERSE EVENTS IN 8 YEARS

However, beginning with a report of azithromycin-triggered torsades de pointes in 2001,5 a growing body of evidence, derived from postmarketing surveillance, has linked azithromycin to cardiac arrhythmias such as pronounced QT interval prolongation and associated torsades de pointes (which can progress to life-threatening ventricular fibrillation). Other, closely related macrolides such as clarithromycin and erythromycin are also linked to these effects.

Furthermore, in the 8-year period from 2004 to 2011, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) received a total of 203 reports of azithromycin-associated QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, ventricular arrhythmia, or, in 65 cases, sudden cardiac death (Table 1).6

At face value, the number of FAERS reports appears to be similar between the various macrolide antibiotics. However, it is important to remember that these drugs differ substantially in the number of prescriptions written for them, with azithromycin being prescribed more often. Also, the FAERS numbers are subject to a number of well-known limitations such as confounding variables, uneven quality and completeness of reports, duplication, and underreporting. These limitations preclude the use of such adverse reporting databases in calculating and thereby comparing the true incidence of adverse events associated with the various macrolide antibiotics.6–9

RAY ET AL FIND A HIGHER RISK OF CARDIOVASCULAR DEATH

Despite these inherent flaws, initial postmarketing surveillance reports cast enough doubt on the long-standing notion that azithromycin is the safest macrolide antibiotic to prompt Ray et al10 to assess its safety in an observational, nonrandomized study of people enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid program.

They found that, over the typical 5 days of therapy, people taking azithromycin had a rate of cardiovascular death 2.88 times higher than in people taking no antibiotic, and 2.49 times higher than in people taking amoxicillin (Table 2).

However, the absolute excess risk compared with amoxicillin varied considerably according to baseline risk score for cardiovascular disease, with 1 excess cardiovascular death per 4,100 in the highest-risk decile compared with 1 excess cardiovascular death per 100,000 in the lowest-risk decile.10,11

Moreover, the increase in deaths did not persist after the 5 days of therapy. This time-limited pattern directly correlated with expected peak azithromycin plasma levels during a standard 5-day course.

Ray et al used appropriate analytic methods to attempt to correct for any confounding bias intrinsic to the observational, nonrandomized study design. Nevertheless, the patients were Medicaid beneficiaries, who have a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions and higher mortality rates than the general population. Therefore, legitimate questions were raised about whether the results of the study could be generalized to populations with substantially lower baseline risk of cardiovascular disease and if differences in the baseline characteristics of the treatment groups were adequately controlled.12,13

THE FDA REVISES AZITHROMYCIN’S WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS

The striking observations by Ray et al,10 coupled with the concerns raised by postmarketing surveillance reports, compelled the FDA to review the labels of azithromycin and other macrolide antibiotics.

Ultimately, the FDA opted to revise the “warning and precautions” section of the azithromycin drug label to include a warning about the potential risk of fatal arrhythmias, specifically QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes. In a March 2013 safety announcement, it also urged health care professionals to use caution when prescribing azithromycin to patients known to have risk factors for drug-related arrhythmias, including congenital long QT syndrome, acquired QT interval prolongation, hypokalemia, hypomagnesia, bradycardia, and concurrent use of other medications known to prolong the QT interval, specifically the class IA (eg, quinidine and procainamide) and class III (eg, amiodarone, sotalol, and dofetilide) antiarrhythmics.

SVANSTRÖM ET AL FIND NO INCREASED RISK

However, just when the medical community appeared ready to accept that azithromycin may not be as safe as we thought it was, a large prospective study by Svanström et al, published in early May 2013, found no increased risk of cardiovascular death associated with azithromycin (Table 2).14

The patients were a representative population of young to middle-aged Danish adults at low baseline risk of underlying cardiovascular disease.

Interestingly, Svanström et al were careful to point out that their study was only powered to rule out a moderate-to-high (> 55%) increase in the relative risk of cardiovascular death. Furthermore, profound differences existed in the baseline risk of death and cardiovascular risk factors between their patients and the Tennessee Medicaid patients studied by Ray et al.14 Therefore, the authors suggested that their study complements rather than contradicts the study by Ray et al. They attributed the differences in the findings to treatment-effect heterogeneity, in which the risk of azithromycin-associated cardiovascular mortality is largely limited to high-risk patients, namely those with multiple preexisting cardiovascular risk factors.14

ACC/AHA RECOMMENDATION: IDENTIFY THOSE AT RISK

Collectively, the data reviewed above provide compelling evidence that azithromycin is not completely free of the QT-prolonging and torsadogenic effects that have long been associated with other macrolide antibiotics. However, the findings from both the study by Ray et al and that of Svanström et al suggest that preexisting cardiovascular risk factors play a prominent role in determining the incidence of azithromycin-associated cardiovascular death in a given population (Table 2).10,14

These findings should prompt physicians to carefully reassess the risks and benefits of azithromycin use in their clinical practices. They also reinforce a recent call by the American Heart Association (AHA) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) to better identify, early on, patients at risk of drug-induced ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death and to subsequently improve how these patients are monitored when the use of QT-prolonging and torsadogenic drugs is medically necessary.15

AN ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORD FLAGS QTc ≥ 500 MS

On the heels of these AHA/ACC suggestions, our hospital has adopted an institution-wide QT alert system. Here, the electronic medical record system (Centricity EMR; GE Healthcare) uses a proprietary algorithm to detect and electronically alert ordering physicians when a patient has a prolonged QT interval, and gives information about the potential clinical significance of this electrocardiographic finding.16 Physicians also receive a warning when ordering QT-prolonging drugs in patients at risk.

This system is still in its infancy, but it has already confirmed that a prolonged QT interval (QTc ≥ 500 ms) is a powerful predictor of death from any cause and has demonstrated that mortality rates in those with prolonged QT intervals increase in a dose-dependent fashion with the patient’s number of modifiable risk factors (eg, electrolyte disturbances or QT-prolonging medications) and nonmodifiable risk factors (eg, genetic disposition, female sex, structural heart disease, diabetes mellitus).16 We have also found evidence that modifiable risk factors may have a more pronounced effect on mortality risk than non-modifiable risk factors.16

These findings suggest that information technology-based QT alert systems may one day provide physicians with an important tool to efficiently identify and possibly even modify the risk of cardiovascular death in patients at high risk, for example, by correcting electrolyte abnormalities or reducing the burden of QT-prolonging medications.

CONSIDER RISK OF QT PROLONGATION WHEN PRESCRIBING AZITHROMYCIN

For most institutions and clinical practices, such electronic QT alert systems are still years if not decades away. However, in light of the information summarized above, all physicians should begin considering risk factors for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes (summarized in Table 3) and weighing the risks and benefits of prescribing azithromycin vs alternative antibiotics with minimal QT liability. This should be relatively simple to do. Things to keep in mind:

- Although azithromycin may increase the relative risk of a cardiovascular event, for most otherwise-healthy patients, the absolute risk is miniscule.

- In a patient at risk (eg, with baseline QT prolongation or multiple risk factors for it), if azithromycin or another QT-prolonging antibiotic such as a macrolide or fluoroquinolone is medically necessary due to preferential bacterial susceptibility or patient allergies, every effort should be made to correct modifiable risk factors (eg, electrolyte abnormalities) and, if possible, to avoid polypharmacy with multiple QT-prolonging drugs.

- For patients who have multiple risk factors for QT prolongation in whom treatment with a known QT-prolonging medication is still deemed in the patient’s best interest, strong consideration should be given to inpatient administration and monitoring until the treatment has been completed.

With careful consideration of modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors as well as a little extra caution when prescribing potential QT-prolonging medications such as azithromycin, the clinical benefit of these often-advantageous medications can be maximized and the incidence of these tragic but rare drug-induced sudden cardiac deaths can be reduced.

- Hopkins S. Clinical toleration and safety of azithromycin. Am J Med 1991; 91:40S–45S.

- Milberg P, Eckardt L, Bruns HJ, et al. Divergent proarrhythmic potential of macrolide antibiotics despite similar QT prolongation: fast phase 3 repolarization prevents early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303:218–225.

- Ioannidis JP, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Chew P, Lau J. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the comparative efficacy and safety of azithromycin against other antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001; 48:677–689.

- Owens RC, Nolin TD. Antimicrobial-associated QT interval prolongation: pointes of interest. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1603–1611.

- Arellano-Rodrigo E, García A, Mont L, Roqué M. Torsade de pointes and cardiorespiratory arrest induced by azithromycin in a patient with congenital long QT syndrome. (Article in Spanish.) Med Clin (Barc) 2001; 117:118–119.

- Raschi E, Poluzzi E, Koci A, Moretti U, Sturkenboom M, De Ponti F. Macrolides and torsadogenic risk: emerging issues from the fda pharmacovigilance database. J Pharmacovigilance 2013; 1:104.

- Shaffer D, Singer S, Korvick J, Honig P. Concomitant risk factors in reports of torsades de pointes associated with macrolide use: review of the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:197–200.

- Stephenson WP, Hauben M. Data mining for signals in spontaneous reporting databases: proceed with caution. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16:359–365.

- Bate A, Evans SJ. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009; 18:427–436.

- Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1881–1890.

- Mosholder AD, Mathew J, Alexander JJ, Smith H, Nambiar S. Cardiovascular risks with azithromycin and other antibacterial drugs. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1665–1668.

- Louie R. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:774–775.

- Koga T, Imaoka H. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:774–775.

- Svanström H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:1704–1712.

- Drew BJ, Ackerman MJ, Funk M, et al; American Heart Association Acute Cardiac Care Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Prevention of torsade de pointes in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2010; 121:1047–1060.

- Haugaa KH, Bos JM, Tarrell RF, Morlan BW, Caraballo PJ, Ackerman MJ. Institution-wide QT alert system identifies patients with a high risk of mortality. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88:315–325.

- Hopkins S. Clinical toleration and safety of azithromycin. Am J Med 1991; 91:40S–45S.

- Milberg P, Eckardt L, Bruns HJ, et al. Divergent proarrhythmic potential of macrolide antibiotics despite similar QT prolongation: fast phase 3 repolarization prevents early afterdepolarizations and torsade de pointes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303:218–225.

- Ioannidis JP, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG, Chew P, Lau J. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the comparative efficacy and safety of azithromycin against other antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001; 48:677–689.

- Owens RC, Nolin TD. Antimicrobial-associated QT interval prolongation: pointes of interest. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43:1603–1611.

- Arellano-Rodrigo E, García A, Mont L, Roqué M. Torsade de pointes and cardiorespiratory arrest induced by azithromycin in a patient with congenital long QT syndrome. (Article in Spanish.) Med Clin (Barc) 2001; 117:118–119.

- Raschi E, Poluzzi E, Koci A, Moretti U, Sturkenboom M, De Ponti F. Macrolides and torsadogenic risk: emerging issues from the fda pharmacovigilance database. J Pharmacovigilance 2013; 1:104.

- Shaffer D, Singer S, Korvick J, Honig P. Concomitant risk factors in reports of torsades de pointes associated with macrolide use: review of the United States Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35:197–200.

- Stephenson WP, Hauben M. Data mining for signals in spontaneous reporting databases: proceed with caution. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007; 16:359–365.

- Bate A, Evans SJ. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009; 18:427–436.

- Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1881–1890.