User login

Evaluation of VTE Prophylaxis in CLD

Chronic liver disease (CLD) or cirrhosis results in greater than 400,000 hospital admissions every year and accounted for approximately 29,000 deaths in 2007.1,2 CLD patients often have an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) due to disease‐associated coagulopathy resulting from a decrease in the production of most procoagulant factors. Due to INR elevations in CLD, clinicians are given a false sense of security surrounding the risk of developing a venous thromboembolism (VTE). The hypothesis that CLD patients are autoanticoagulated and therefore protected against VTE has not been proven.

In the United States, the total incidence of VTE is greater than 200,000 events per year accompanied by a significant number of events occurring in high‐risk hospitalized patients.[3] It has been suggested that patients with liver disease may have a reduced risk for VTE.[4] However, more recent studies report an increased risk with the incidence of VTE in CLD patients occurring in 0.5% to 6.3% of the population.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] The parallel reduction of anticoagulant factors, such as antithrombin and protein C, along with the reduction in procoagulant factors rebalances the coagulation system, possibly explaining why CLD patients are not protected from VTE.[11, 12] Other mechanistic possibilities include low serum albumin,[8, 9] an elevation of endogenous estrogen levels, immobility associated with the disease,[5] greater morbidity as reflected by high Child‐Pugh scores, and a chronic inflammatory state that results in poor flow and vasculopathy.[7]

Current guidelines for the prevention of VTE do not provide recommendations on the use of prophylaxis in the cirrhotic population,[13] although recent literature reviews suggest that strong consideration for pharmacologic prophylaxis be given when the benefit outweighs the risk.[14, 15] Limited studies have evaluated the use of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients, whether pharmacologic or mechanical.[6, 7, 8, 16] These studies report that the utilization of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients is suboptimal, with at least 75% of CLD patients receiving no prophylaxis.[6, 7, 8] The purpose of our study was to examine the use of prophylactic agents and the incidence of VTE and bleeding events in CLD patients.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with CLD or cirrhosis at Methodist University Hospital between August 1, 2009 and July 31, 2011 was conducted. These patients were identified through the corporate patient financial services database using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification code 571.xx for CLD/cirrhosis. Patients were included if they were 18 years or older, admitted for or with a history of CLD, and had an INR of 1.4 on admission. An elevated INR was chosen as inclusion criteria as this is often when the controversy of prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis emerges. CLD was defined based on previous histories or clinical presentations of past variceal bleed, presence of varices based on endoscopy report, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, ascites, liver biopsy proven cirrhosis, or imaging consistent with cirrhotic liver changes. CLD was classified as alcoholic, viral hepatitis (hepatitis B and C), and other, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and autoimmune. Patients admitted with maintenance anticoagulation, suspected bleed or VTE, palliative care diagnosis, or history of/anticipated liver transplant were excluded. If a patient met inclusion criteria for an admission and was subsequently readmitted within 30 days, only the initial admission was included. Once patients were included they were assigned to 1 of 4 groups based on the type of prophylaxis received: pharmacologic, mechanical, combined pharmacologic and mechanical, and no prophylaxis. Patients who received pharmacologic or mechanical prophylaxis for at least 50% of their hospital stay were assigned to their corresponding groups accordingly. Patients who received pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis for at least 50% of their hospital stay were assigned to the combination group. Patients receiving either form of VTE prophylaxis for <50% of their hospital stay were considered to be without prophylaxis. Pharmacologic prophylaxis was defined by the use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) 5000 units subcutaneously (sq) 3 times daily or twice daily (bid), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) 30 mg sq bid or 40 mg every day (qd), or fondaparinux 2.5 mg qd. Mechanical prophylaxis was defined by the use of a sequential compression device (SCD). The study was approved by the University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board.

Patient demographics including age, sex, race, height, and weight were documented with a body mass index (BMI) calculated for each patient. Obesity was defined as BMI 30 kg/m2. Risk factors for VTE including obesity, surgery, infection, trauma, malignancy, and history of VTE as well as the etiology of cirrhosis were collected and recorded whenever available based on documentation in the medical chart. Clinical data including lowest serum albumin, highest total bilirubin, highest INR, and platelets on admission were recorded. Severity of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy were documented. Child‐Pugh score and stage as well as Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score were calculated. In‐hospital VTE, bleeding events, length of stay, in‐hospital mortality, and the use, type, and number of days of VTE prophylaxis were documented. VTE was defined as deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism diagnosed by venous Doppler ultrasonography, spiral computed tomography (CT) of the chest, or ventilation/perfusion scan. Bleeding was defined by documentation in the medical record plus the administration of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, recombinant factor VIIa, or vitamin K. For patients who experienced a bleed, risk factors for in‐hospital bleeding as defined by American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines 2012 guidelines (CHEST) were documented.[13]

The primary outcome was to describe the use of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients. Secondary outcomes were to determine the overall incidence of VTE in CLD patients, examine the incidence of VTE based on the utilization of prophylaxis, compare the occurrence of bleeding events in CLD patients based on type of prophylaxis, evaluate the use of mechanical versus pharmacologic prophylaxis based on INR, evaluate length of stay (LOS) and in‐hospital mortality for CLD patients with and without prophylaxis, and evaluate 30‐day readmission rate for VTE.

Patients were arbitrarily divided into 2 groups according to the highest INR (1.42.0 or >2.0). Baseline characteristics were compared between the 2 groups. Variables were expressed as mean or median with standard deviation or interquartile range. Categorical values were expressed as percentages and compared using the [2] test or Fisher exact test. Continuous data were compared using Mann‐Whitney U test for nonparametric data or Student t test for parametric data. Significance was defined as P<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 20.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

We identified 410 patients who met inclusion criteria during the study period. Baseline demographics were similar between the 2 groups with the exception of age, which was statistically higher in the INR 1.4 to 2.0 group. The most common etiology of CLD was hepatitis B or C, followed by alcohol, then other causes. Alcoholic CLD was associated with higher INR values (>2.0). Patients with INR >2.0 were found to exhibit lower serum albumin levels and platelets on admission as well as higher total bilirubin and INR values. There was also a significant difference in Child‐Pugh stages B and C, with the INR >2.0 group only having stage C. In addition, the higher INR group had a significantly higher average MELD score (Table 1).

| Characteristic | INR1.42.0, n=251 | INR>2.0, n=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, yearsSD | 55.710.4 | 53.310.1 | 0.017 |

| Male sex | 137 (54.6) | 99 (62.3) | 0.125 |

| BMISD | 29.17.3 | 30.37.7 | 0.103 |

| Race | |||

| African American | 99 (39.4) | 53 (33.3) | 0.212 |

| White | 139 (55.4) | 99 (62.3) | 0.169 |

| Other | 13 (5.2) | 7 (4.4) | 0.722 |

| Etiology of CLD | |||

| Hepatitis B or C | 127 (50.6) | 70 (44) | 0.194 |

| Alcohol | 59 (23.5) | 57 (35.9) | 0.007 |

| Other | 65 (25.9) | 32 (20.1) | 0.18 |

| VTE risk factors | |||

| Obesity, BMI 30 | 107 (42.6) | 71 (44.6) | 0.687 |

| Surgery | 21 (8.4) | 7 (4.1) | 0.121 |

| Infection | 81 (32.3) | 63 (39.6) | 0.129 |

| Trauma | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 1.00 |

| Malignancy | 35 (13.9) | 24 (15.1) | 0.746 |

| History of VTE | 6 (2.4) | 4 (2.5) | 1.00 |

| Median number VTE risk factors (range) | 1 (03) | 1 (04) | 0.697 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| AlbuminSD | 2.20.58 | 2.00.53 | <0.001 |

| Tbili, median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.95.0) | 8.1 (5.013.3) | <0.001 |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.51.8) | 2.4 (2.22.9) | <0.001 |

| Admission platelets, median (IQR) | 92 (61141) | 79 (58121) | 0.008 |

| Child Pugh stage | |||

| Class A | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.286 |

| Class B | 91 (36.3) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Class C | 157 (62.5) | 159 (100) | <0.001 |

| MELD scoreSD | 18.55.1 | 28.36.3 | <0.001 |

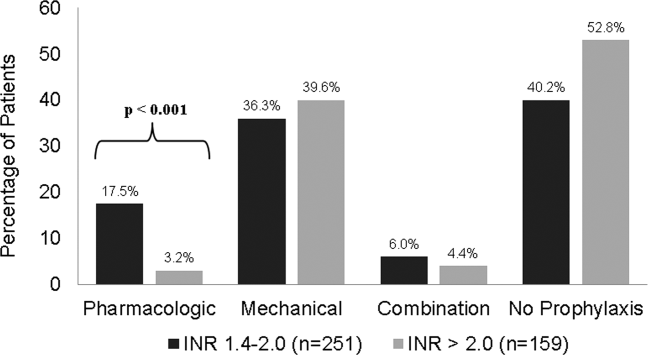

Of the 410 patients included, 225 (55%) patients received thromboprophylaxis. The majority of patients received mechanical prophylaxis (n=154), followed by pharmacologic (n=49), and then a combination of mechanical plus pharmacologic (n=22). For patients receiving pharmacologic either alone or in combination with SCDs, 30 received UFH, 33 received LMWH, 1 patient received fondaparinux, and the remaining 7 received a combination of the agents to total 50% of their hospital stay. For patients with INR >2.0, a significant decrease in overall thromboprophylaxis use was seen compared to those with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (47% vs 60%; P=0.013). Patients with INR >2.0 also received significantly less pharmacologic prophylaxis compared to those with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (3.2% vs 17.5%; P<0.001). No differences in the use of mechanical or combination prophylaxis was seen between the groups (Figure 1).

As shown in Table 2, in‐hospital VTE occurred in 3 patients (0.7%). All 3 patients had a DVT. Of the patients with documented VTE, 1 was Child‐Pugh stage B and 2 were stage C. Fifteen bleeding events occurred (3.7%), 9 on mechanical prophylaxis, 1 on pharmacologic, 3 on combination, and 2 with no prophylaxis. The majority of patients experiencing a bleeding event had an INR >2.0 (P=0.001). Eleven patients out of the 15 were considered to be at high risk of bleeding as defined per CHEST 2012 guidelines,[13] whereas 100% had Child‐Pugh stage C with an average MELD score of 31.77.5. It should be noted that 1 patient experienced a bleeding event after receiving pharmacologic treatment doses for VTE and was subsequently placed on a prophylactic dose without any bleeding complications.

| Characteristic | INR1.42.0, n=251 | INR>2.0, n=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| In‐hospital VTE | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.563 |

| Mechanical | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Pharmacologic | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Combination | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| No prophylaxis | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Bleeding event | 3 (1.2) | 12 (7.5) | 0.001 |

| Mechanical | 2 (0.8) | 7 (4.4) | 0.033 |

| Pharmacologic* | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Combination | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.563 |

| No prophylaxis | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 0.152 |

| LOS, median (IQR) | 5 (2.98) | 7.2 (413.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital mortality | 6 (2.4) | 30 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| 30‐day readmission rate for VTE | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.524 |

Longer LOS and higher mortality rates were seen in patients who received prophylaxis compared to those who received no prophylaxis (P<0.001 and P=0.001, respectively). Of the 36 patients who died, 22 received mechanical prophylaxis, 2 received pharmacologic, 5 received a combination, and 7 received no prophylaxis. Longer LOS and higher mortality rates were also seen in patients with INR >2 compared to patients with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (P<0.001 for both) (Table 2). Higher mortality rates were associated with greater severity of disease as defined by Child‐Pugh C classification in all 36 patients (P=0.001) and an average MELD score of 31.87.6. No differences in 30‐day readmission rates for VTE were seen between prophylaxis groups.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

The use of thromboprophylaxis in our study was 55%, which is consistent with the reported rate of 30% to 70% in general hospitalized patients.[17] To our knowledge this is the first study to focus primarily on the use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients. Previous studies have focused on the incidence and risks of VTE in CLD patients,[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] with only 3 of those studies evaluating the use of pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis as a secondary outcome.[6, 7, 8] The reported use of thromboprophylaxis in these studies ranges from 21% to 25%. Pharmacologic prophylaxis rates were 7% in Northup et al.,[8] 12% in Aldawood et al.,[7] and 9% in Dabbagh et al.,[6] compared to 17% in our study (pharmacologic alone plus combination). Mechanical prophylaxis rates were 14%, 12%, and 16%, respectively, compared to our 38%. None of the previous studies gave a definition for prophylaxis. This is important to note because discrepancies in prophylaxis reporting could lead to significant differences in rates of prophylaxis when comparing these studies to our study.

Despite the higher rates of thromboprophylaxis, the incidence of VTE was 0.7%. Our VTE incidence falls within the reported incidence rate of 0.5% to 6.3%.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Similar to Aldawood et al. and Dabbagh et al., we found no significant differences in the incidence of VTE and prophylaxis use.[6, 7] Dabbagh et al. suggest that the incidence of VTE increases as disease severity increases.[6] However, with only 25% of their patients receiving thromboprophylaxis, it is hard to determine if the higher incidence of VTE was due to greater disease severity or the low use of thromboprophylaxis. It is expected that patients with more severe disease are less likely to receive VTE prophylaxis secondary to increases in INR and/or thrombocytopenia. As evidenced in our study, there was a significant decrease in the use of thromboprophylaxis in patients with INR >2.0, driven largely by the significant decrease in the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis. Due to the low incidence of VTE observed, our study lacks adequate power to truly determine the relationship between use of thromboprophylaxis or severity of disease and incidence of VTE.

Nonetheless, we did find a significant correlation between disease severity and bleeding in CLD patients. Although not a new finding in the literature, this result substantiates the claim that the delicate balance and unpredictability of coagulopathy in CLD leads to bleeding events as well as VTE. In our study we had an overall bleeding rate of 3.7%. Patients who experienced a bleeding event had greater disease severity, significantly higher INR, and 73% were considered to be at high risk for an event as defined by CHEST guidelines.[13] The majority of events happened while on mechanical or no prophylaxis. Four patients who received pharmacologic prophylaxis had a bleeding event; however, 1 of those patients bled on VTE pharmacologic treatment dose for VTE found on day 2 of hospital admission. In a recent study by Bechmann et al. looking at the use of LMWH in 84 cirrhotic patients, they report a bleeding rate of 8.3%, a rate that is similar to rates of bleeding in nonanticoagulated cirrhotic patients.[18] In comparison with our study, we had 71 patients receive pharmacologic prophylaxis either alone or in combination and 4 bleeding events, giving an event rate of 5.6%. This rate decreases to 4.2% when considering only prophylactic pharmacologic doses, suggesting that pharmacologic prophylaxis in CLD patients poses a low risk of bleeding. Interestingly enough, an association was found between alcoholic CLD and higher INR (>2.0) in our study. Given that patients with higher INR had increased bleeding events, this introduces a question of whether or not the specific cause of CLD (ie, alcoholic hepatitis) may represent a special risk for bleeding in this population. However, additional studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

To our knowledge, this study is also the first to look at the relationship of thromboprophylaxis use on LOS and mortality in CLD patients. At first glance, the fact that patients who received prophylaxis had both significantly longer LOS and higher mortality rates in our study is concerning. However, it is likely that the increased LOS and mortality in our study is attributed to greater disease severity, as evidenced by higher INRs and Child‐Pugh scores regardless of prophylaxis use or not. Also, a known risk factor for VTE is reduced mobility. Although no standard definition for reduced mobility exists, Barbar et al. define it as anticipated bed rest with bathroom privileges (either because of patient's limitations or on physician's order) for at least 3 days.[19] Due to this known increased risk for VTE, it is expected that patient's with a LOS of 3 days are more likely to receive thromboprophylaxis.

Our study has several limitations. Like other retrospective studies, this study was conducted in 1 medical center and relies on the accuracy of documentation. We relied on patient history and clinical presentation to diagnose CLD without the requirement of histologic diagnosis. However, all patients included in the study had an unquestionable diagnosis by a physician. We used an arbitrary definition and assignment of patients into groups based on the method of VTE prophylaxis utilized due to lack of a definition in the medical literature. There was a possible selection bias for pharmacologic prophylaxis based on patient risk factors for bleeding, such as presence of varices and thrombocytopenia. Also, the inability to ensure that patients with an order for SCDs were actively wearing the device throughout their hospital stay is yet another limitation. Not all patients underwent testing for VTE; therefore, the actual incidence of VTE may be higher than what we found. Only those patients who experienced a bleeding event were assessed for risk factors that predisposed them to bleed, making it hard to correlate those risk factors with the risk of bleeding in all CLD patients.

Despite these limitations, our study has great strengths. This is the first study to focus primarily on the use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients. Therefore, it has the potential to influence and raise awareness on the decisions made involving the management of CLD patients in regard to VTE prophylaxis and will hopefully serve as an impetus for future prospective studies. When comparing this study to other studies looking at the incidence of VTE in CLD patients and the use of prophylaxis, our study sample size is relatively large. Also, by including only those patients with INR of at least 1.4 on admission, our study patients had greater severity of disease, making this study distinctly relevant in the clinical debate of whether or not CLD patients should receive thromboprophylaxis.

In conclusion, the use of thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients is higher in our study than previous reports but remains suboptimal. Although bleeding is an inherent risk factor in CLD independent of VTE prophylaxis, the use of VTE pharmacologic prophylaxis does not appear to increase bleeding in CLD patients with INR 2.0. Further studies focusing on baseline bleeding risks (ie, thrombocytopenia, presence of varices) and the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis are needed to provide additional safety data on the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in this patient population.

Disclosures: All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. Submission is not under review by any other publication. All authors have not received notification of redundant or duplicate publication. All authors have no financial conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study or article.

- , , . National hospital discharge survey: 2002 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat 13. 2005;158:1–199.

- , , , . Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(19):1–135.

- , , , et al. The diagnostic approach to acute venous thromboembolism: clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(3):1043–1066.

- , , , , , . Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based case‐control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815.

- , , , , , . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: a nationwide population‐based case‐control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(1):96–101.

- , , , , . Coagulopathy does not protect against venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Chest. 2010;137(5):1145–1149.

- , , , et al. The incidence of venous thromboembolism and practice of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. Thromb J. 2011;9(1):1.

- , , , et al. Coagulopathy does not fully protect hospitalized cirrhosis patients from peripheral venous thromboembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1524–1528.

- , , , , . Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhosis patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(11):3012–3017.

- , , , , , . Venous thromboembolism and liver cirrhosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100(5):259–262.

- , , . Should we give thromboprophylaxis to patients with liver cirrhosis and coagulopathy? HPB. 2009;11(6):459–464.

- , . The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):147–156.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e195S–e226S.

- , . Pharmacologic prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and associated coagulopathies. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(8):658–63.

- , , . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(6):873–878.

- , , , et al. A systematic review of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis strategies in patients with renal insufficiency, obesity, or on antiplatelet agents. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):394–401.

- , , , , , . Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the hospitalized medical patient. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(suppl 3):S7–S16.

- , , , , , . Low‐molecular‐weight heparin in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2011;31(1):75–82.

- , , , et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2450–2457.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) or cirrhosis results in greater than 400,000 hospital admissions every year and accounted for approximately 29,000 deaths in 2007.1,2 CLD patients often have an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) due to disease‐associated coagulopathy resulting from a decrease in the production of most procoagulant factors. Due to INR elevations in CLD, clinicians are given a false sense of security surrounding the risk of developing a venous thromboembolism (VTE). The hypothesis that CLD patients are autoanticoagulated and therefore protected against VTE has not been proven.

In the United States, the total incidence of VTE is greater than 200,000 events per year accompanied by a significant number of events occurring in high‐risk hospitalized patients.[3] It has been suggested that patients with liver disease may have a reduced risk for VTE.[4] However, more recent studies report an increased risk with the incidence of VTE in CLD patients occurring in 0.5% to 6.3% of the population.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] The parallel reduction of anticoagulant factors, such as antithrombin and protein C, along with the reduction in procoagulant factors rebalances the coagulation system, possibly explaining why CLD patients are not protected from VTE.[11, 12] Other mechanistic possibilities include low serum albumin,[8, 9] an elevation of endogenous estrogen levels, immobility associated with the disease,[5] greater morbidity as reflected by high Child‐Pugh scores, and a chronic inflammatory state that results in poor flow and vasculopathy.[7]

Current guidelines for the prevention of VTE do not provide recommendations on the use of prophylaxis in the cirrhotic population,[13] although recent literature reviews suggest that strong consideration for pharmacologic prophylaxis be given when the benefit outweighs the risk.[14, 15] Limited studies have evaluated the use of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients, whether pharmacologic or mechanical.[6, 7, 8, 16] These studies report that the utilization of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients is suboptimal, with at least 75% of CLD patients receiving no prophylaxis.[6, 7, 8] The purpose of our study was to examine the use of prophylactic agents and the incidence of VTE and bleeding events in CLD patients.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with CLD or cirrhosis at Methodist University Hospital between August 1, 2009 and July 31, 2011 was conducted. These patients were identified through the corporate patient financial services database using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification code 571.xx for CLD/cirrhosis. Patients were included if they were 18 years or older, admitted for or with a history of CLD, and had an INR of 1.4 on admission. An elevated INR was chosen as inclusion criteria as this is often when the controversy of prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis emerges. CLD was defined based on previous histories or clinical presentations of past variceal bleed, presence of varices based on endoscopy report, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, ascites, liver biopsy proven cirrhosis, or imaging consistent with cirrhotic liver changes. CLD was classified as alcoholic, viral hepatitis (hepatitis B and C), and other, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and autoimmune. Patients admitted with maintenance anticoagulation, suspected bleed or VTE, palliative care diagnosis, or history of/anticipated liver transplant were excluded. If a patient met inclusion criteria for an admission and was subsequently readmitted within 30 days, only the initial admission was included. Once patients were included they were assigned to 1 of 4 groups based on the type of prophylaxis received: pharmacologic, mechanical, combined pharmacologic and mechanical, and no prophylaxis. Patients who received pharmacologic or mechanical prophylaxis for at least 50% of their hospital stay were assigned to their corresponding groups accordingly. Patients who received pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis for at least 50% of their hospital stay were assigned to the combination group. Patients receiving either form of VTE prophylaxis for <50% of their hospital stay were considered to be without prophylaxis. Pharmacologic prophylaxis was defined by the use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) 5000 units subcutaneously (sq) 3 times daily or twice daily (bid), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) 30 mg sq bid or 40 mg every day (qd), or fondaparinux 2.5 mg qd. Mechanical prophylaxis was defined by the use of a sequential compression device (SCD). The study was approved by the University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board.

Patient demographics including age, sex, race, height, and weight were documented with a body mass index (BMI) calculated for each patient. Obesity was defined as BMI 30 kg/m2. Risk factors for VTE including obesity, surgery, infection, trauma, malignancy, and history of VTE as well as the etiology of cirrhosis were collected and recorded whenever available based on documentation in the medical chart. Clinical data including lowest serum albumin, highest total bilirubin, highest INR, and platelets on admission were recorded. Severity of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy were documented. Child‐Pugh score and stage as well as Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score were calculated. In‐hospital VTE, bleeding events, length of stay, in‐hospital mortality, and the use, type, and number of days of VTE prophylaxis were documented. VTE was defined as deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism diagnosed by venous Doppler ultrasonography, spiral computed tomography (CT) of the chest, or ventilation/perfusion scan. Bleeding was defined by documentation in the medical record plus the administration of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, recombinant factor VIIa, or vitamin K. For patients who experienced a bleed, risk factors for in‐hospital bleeding as defined by American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines 2012 guidelines (CHEST) were documented.[13]

The primary outcome was to describe the use of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients. Secondary outcomes were to determine the overall incidence of VTE in CLD patients, examine the incidence of VTE based on the utilization of prophylaxis, compare the occurrence of bleeding events in CLD patients based on type of prophylaxis, evaluate the use of mechanical versus pharmacologic prophylaxis based on INR, evaluate length of stay (LOS) and in‐hospital mortality for CLD patients with and without prophylaxis, and evaluate 30‐day readmission rate for VTE.

Patients were arbitrarily divided into 2 groups according to the highest INR (1.42.0 or >2.0). Baseline characteristics were compared between the 2 groups. Variables were expressed as mean or median with standard deviation or interquartile range. Categorical values were expressed as percentages and compared using the [2] test or Fisher exact test. Continuous data were compared using Mann‐Whitney U test for nonparametric data or Student t test for parametric data. Significance was defined as P<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 20.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

We identified 410 patients who met inclusion criteria during the study period. Baseline demographics were similar between the 2 groups with the exception of age, which was statistically higher in the INR 1.4 to 2.0 group. The most common etiology of CLD was hepatitis B or C, followed by alcohol, then other causes. Alcoholic CLD was associated with higher INR values (>2.0). Patients with INR >2.0 were found to exhibit lower serum albumin levels and platelets on admission as well as higher total bilirubin and INR values. There was also a significant difference in Child‐Pugh stages B and C, with the INR >2.0 group only having stage C. In addition, the higher INR group had a significantly higher average MELD score (Table 1).

| Characteristic | INR1.42.0, n=251 | INR>2.0, n=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, yearsSD | 55.710.4 | 53.310.1 | 0.017 |

| Male sex | 137 (54.6) | 99 (62.3) | 0.125 |

| BMISD | 29.17.3 | 30.37.7 | 0.103 |

| Race | |||

| African American | 99 (39.4) | 53 (33.3) | 0.212 |

| White | 139 (55.4) | 99 (62.3) | 0.169 |

| Other | 13 (5.2) | 7 (4.4) | 0.722 |

| Etiology of CLD | |||

| Hepatitis B or C | 127 (50.6) | 70 (44) | 0.194 |

| Alcohol | 59 (23.5) | 57 (35.9) | 0.007 |

| Other | 65 (25.9) | 32 (20.1) | 0.18 |

| VTE risk factors | |||

| Obesity, BMI 30 | 107 (42.6) | 71 (44.6) | 0.687 |

| Surgery | 21 (8.4) | 7 (4.1) | 0.121 |

| Infection | 81 (32.3) | 63 (39.6) | 0.129 |

| Trauma | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 1.00 |

| Malignancy | 35 (13.9) | 24 (15.1) | 0.746 |

| History of VTE | 6 (2.4) | 4 (2.5) | 1.00 |

| Median number VTE risk factors (range) | 1 (03) | 1 (04) | 0.697 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| AlbuminSD | 2.20.58 | 2.00.53 | <0.001 |

| Tbili, median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.95.0) | 8.1 (5.013.3) | <0.001 |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.51.8) | 2.4 (2.22.9) | <0.001 |

| Admission platelets, median (IQR) | 92 (61141) | 79 (58121) | 0.008 |

| Child Pugh stage | |||

| Class A | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.286 |

| Class B | 91 (36.3) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Class C | 157 (62.5) | 159 (100) | <0.001 |

| MELD scoreSD | 18.55.1 | 28.36.3 | <0.001 |

Of the 410 patients included, 225 (55%) patients received thromboprophylaxis. The majority of patients received mechanical prophylaxis (n=154), followed by pharmacologic (n=49), and then a combination of mechanical plus pharmacologic (n=22). For patients receiving pharmacologic either alone or in combination with SCDs, 30 received UFH, 33 received LMWH, 1 patient received fondaparinux, and the remaining 7 received a combination of the agents to total 50% of their hospital stay. For patients with INR >2.0, a significant decrease in overall thromboprophylaxis use was seen compared to those with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (47% vs 60%; P=0.013). Patients with INR >2.0 also received significantly less pharmacologic prophylaxis compared to those with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (3.2% vs 17.5%; P<0.001). No differences in the use of mechanical or combination prophylaxis was seen between the groups (Figure 1).

As shown in Table 2, in‐hospital VTE occurred in 3 patients (0.7%). All 3 patients had a DVT. Of the patients with documented VTE, 1 was Child‐Pugh stage B and 2 were stage C. Fifteen bleeding events occurred (3.7%), 9 on mechanical prophylaxis, 1 on pharmacologic, 3 on combination, and 2 with no prophylaxis. The majority of patients experiencing a bleeding event had an INR >2.0 (P=0.001). Eleven patients out of the 15 were considered to be at high risk of bleeding as defined per CHEST 2012 guidelines,[13] whereas 100% had Child‐Pugh stage C with an average MELD score of 31.77.5. It should be noted that 1 patient experienced a bleeding event after receiving pharmacologic treatment doses for VTE and was subsequently placed on a prophylactic dose without any bleeding complications.

| Characteristic | INR1.42.0, n=251 | INR>2.0, n=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| In‐hospital VTE | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.563 |

| Mechanical | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Pharmacologic | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Combination | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| No prophylaxis | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Bleeding event | 3 (1.2) | 12 (7.5) | 0.001 |

| Mechanical | 2 (0.8) | 7 (4.4) | 0.033 |

| Pharmacologic* | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Combination | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.563 |

| No prophylaxis | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 0.152 |

| LOS, median (IQR) | 5 (2.98) | 7.2 (413.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital mortality | 6 (2.4) | 30 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| 30‐day readmission rate for VTE | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.524 |

Longer LOS and higher mortality rates were seen in patients who received prophylaxis compared to those who received no prophylaxis (P<0.001 and P=0.001, respectively). Of the 36 patients who died, 22 received mechanical prophylaxis, 2 received pharmacologic, 5 received a combination, and 7 received no prophylaxis. Longer LOS and higher mortality rates were also seen in patients with INR >2 compared to patients with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (P<0.001 for both) (Table 2). Higher mortality rates were associated with greater severity of disease as defined by Child‐Pugh C classification in all 36 patients (P=0.001) and an average MELD score of 31.87.6. No differences in 30‐day readmission rates for VTE were seen between prophylaxis groups.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

The use of thromboprophylaxis in our study was 55%, which is consistent with the reported rate of 30% to 70% in general hospitalized patients.[17] To our knowledge this is the first study to focus primarily on the use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients. Previous studies have focused on the incidence and risks of VTE in CLD patients,[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] with only 3 of those studies evaluating the use of pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis as a secondary outcome.[6, 7, 8] The reported use of thromboprophylaxis in these studies ranges from 21% to 25%. Pharmacologic prophylaxis rates were 7% in Northup et al.,[8] 12% in Aldawood et al.,[7] and 9% in Dabbagh et al.,[6] compared to 17% in our study (pharmacologic alone plus combination). Mechanical prophylaxis rates were 14%, 12%, and 16%, respectively, compared to our 38%. None of the previous studies gave a definition for prophylaxis. This is important to note because discrepancies in prophylaxis reporting could lead to significant differences in rates of prophylaxis when comparing these studies to our study.

Despite the higher rates of thromboprophylaxis, the incidence of VTE was 0.7%. Our VTE incidence falls within the reported incidence rate of 0.5% to 6.3%.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Similar to Aldawood et al. and Dabbagh et al., we found no significant differences in the incidence of VTE and prophylaxis use.[6, 7] Dabbagh et al. suggest that the incidence of VTE increases as disease severity increases.[6] However, with only 25% of their patients receiving thromboprophylaxis, it is hard to determine if the higher incidence of VTE was due to greater disease severity or the low use of thromboprophylaxis. It is expected that patients with more severe disease are less likely to receive VTE prophylaxis secondary to increases in INR and/or thrombocytopenia. As evidenced in our study, there was a significant decrease in the use of thromboprophylaxis in patients with INR >2.0, driven largely by the significant decrease in the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis. Due to the low incidence of VTE observed, our study lacks adequate power to truly determine the relationship between use of thromboprophylaxis or severity of disease and incidence of VTE.

Nonetheless, we did find a significant correlation between disease severity and bleeding in CLD patients. Although not a new finding in the literature, this result substantiates the claim that the delicate balance and unpredictability of coagulopathy in CLD leads to bleeding events as well as VTE. In our study we had an overall bleeding rate of 3.7%. Patients who experienced a bleeding event had greater disease severity, significantly higher INR, and 73% were considered to be at high risk for an event as defined by CHEST guidelines.[13] The majority of events happened while on mechanical or no prophylaxis. Four patients who received pharmacologic prophylaxis had a bleeding event; however, 1 of those patients bled on VTE pharmacologic treatment dose for VTE found on day 2 of hospital admission. In a recent study by Bechmann et al. looking at the use of LMWH in 84 cirrhotic patients, they report a bleeding rate of 8.3%, a rate that is similar to rates of bleeding in nonanticoagulated cirrhotic patients.[18] In comparison with our study, we had 71 patients receive pharmacologic prophylaxis either alone or in combination and 4 bleeding events, giving an event rate of 5.6%. This rate decreases to 4.2% when considering only prophylactic pharmacologic doses, suggesting that pharmacologic prophylaxis in CLD patients poses a low risk of bleeding. Interestingly enough, an association was found between alcoholic CLD and higher INR (>2.0) in our study. Given that patients with higher INR had increased bleeding events, this introduces a question of whether or not the specific cause of CLD (ie, alcoholic hepatitis) may represent a special risk for bleeding in this population. However, additional studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

To our knowledge, this study is also the first to look at the relationship of thromboprophylaxis use on LOS and mortality in CLD patients. At first glance, the fact that patients who received prophylaxis had both significantly longer LOS and higher mortality rates in our study is concerning. However, it is likely that the increased LOS and mortality in our study is attributed to greater disease severity, as evidenced by higher INRs and Child‐Pugh scores regardless of prophylaxis use or not. Also, a known risk factor for VTE is reduced mobility. Although no standard definition for reduced mobility exists, Barbar et al. define it as anticipated bed rest with bathroom privileges (either because of patient's limitations or on physician's order) for at least 3 days.[19] Due to this known increased risk for VTE, it is expected that patient's with a LOS of 3 days are more likely to receive thromboprophylaxis.

Our study has several limitations. Like other retrospective studies, this study was conducted in 1 medical center and relies on the accuracy of documentation. We relied on patient history and clinical presentation to diagnose CLD without the requirement of histologic diagnosis. However, all patients included in the study had an unquestionable diagnosis by a physician. We used an arbitrary definition and assignment of patients into groups based on the method of VTE prophylaxis utilized due to lack of a definition in the medical literature. There was a possible selection bias for pharmacologic prophylaxis based on patient risk factors for bleeding, such as presence of varices and thrombocytopenia. Also, the inability to ensure that patients with an order for SCDs were actively wearing the device throughout their hospital stay is yet another limitation. Not all patients underwent testing for VTE; therefore, the actual incidence of VTE may be higher than what we found. Only those patients who experienced a bleeding event were assessed for risk factors that predisposed them to bleed, making it hard to correlate those risk factors with the risk of bleeding in all CLD patients.

Despite these limitations, our study has great strengths. This is the first study to focus primarily on the use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients. Therefore, it has the potential to influence and raise awareness on the decisions made involving the management of CLD patients in regard to VTE prophylaxis and will hopefully serve as an impetus for future prospective studies. When comparing this study to other studies looking at the incidence of VTE in CLD patients and the use of prophylaxis, our study sample size is relatively large. Also, by including only those patients with INR of at least 1.4 on admission, our study patients had greater severity of disease, making this study distinctly relevant in the clinical debate of whether or not CLD patients should receive thromboprophylaxis.

In conclusion, the use of thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients is higher in our study than previous reports but remains suboptimal. Although bleeding is an inherent risk factor in CLD independent of VTE prophylaxis, the use of VTE pharmacologic prophylaxis does not appear to increase bleeding in CLD patients with INR 2.0. Further studies focusing on baseline bleeding risks (ie, thrombocytopenia, presence of varices) and the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis are needed to provide additional safety data on the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in this patient population.

Disclosures: All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. Submission is not under review by any other publication. All authors have not received notification of redundant or duplicate publication. All authors have no financial conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study or article.

Chronic liver disease (CLD) or cirrhosis results in greater than 400,000 hospital admissions every year and accounted for approximately 29,000 deaths in 2007.1,2 CLD patients often have an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) due to disease‐associated coagulopathy resulting from a decrease in the production of most procoagulant factors. Due to INR elevations in CLD, clinicians are given a false sense of security surrounding the risk of developing a venous thromboembolism (VTE). The hypothesis that CLD patients are autoanticoagulated and therefore protected against VTE has not been proven.

In the United States, the total incidence of VTE is greater than 200,000 events per year accompanied by a significant number of events occurring in high‐risk hospitalized patients.[3] It has been suggested that patients with liver disease may have a reduced risk for VTE.[4] However, more recent studies report an increased risk with the incidence of VTE in CLD patients occurring in 0.5% to 6.3% of the population.[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] The parallel reduction of anticoagulant factors, such as antithrombin and protein C, along with the reduction in procoagulant factors rebalances the coagulation system, possibly explaining why CLD patients are not protected from VTE.[11, 12] Other mechanistic possibilities include low serum albumin,[8, 9] an elevation of endogenous estrogen levels, immobility associated with the disease,[5] greater morbidity as reflected by high Child‐Pugh scores, and a chronic inflammatory state that results in poor flow and vasculopathy.[7]

Current guidelines for the prevention of VTE do not provide recommendations on the use of prophylaxis in the cirrhotic population,[13] although recent literature reviews suggest that strong consideration for pharmacologic prophylaxis be given when the benefit outweighs the risk.[14, 15] Limited studies have evaluated the use of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients, whether pharmacologic or mechanical.[6, 7, 8, 16] These studies report that the utilization of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients is suboptimal, with at least 75% of CLD patients receiving no prophylaxis.[6, 7, 8] The purpose of our study was to examine the use of prophylactic agents and the incidence of VTE and bleeding events in CLD patients.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review of patients diagnosed with CLD or cirrhosis at Methodist University Hospital between August 1, 2009 and July 31, 2011 was conducted. These patients were identified through the corporate patient financial services database using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification code 571.xx for CLD/cirrhosis. Patients were included if they were 18 years or older, admitted for or with a history of CLD, and had an INR of 1.4 on admission. An elevated INR was chosen as inclusion criteria as this is often when the controversy of prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis emerges. CLD was defined based on previous histories or clinical presentations of past variceal bleed, presence of varices based on endoscopy report, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, ascites, liver biopsy proven cirrhosis, or imaging consistent with cirrhotic liver changes. CLD was classified as alcoholic, viral hepatitis (hepatitis B and C), and other, such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and autoimmune. Patients admitted with maintenance anticoagulation, suspected bleed or VTE, palliative care diagnosis, or history of/anticipated liver transplant were excluded. If a patient met inclusion criteria for an admission and was subsequently readmitted within 30 days, only the initial admission was included. Once patients were included they were assigned to 1 of 4 groups based on the type of prophylaxis received: pharmacologic, mechanical, combined pharmacologic and mechanical, and no prophylaxis. Patients who received pharmacologic or mechanical prophylaxis for at least 50% of their hospital stay were assigned to their corresponding groups accordingly. Patients who received pharmacologic and mechanical prophylaxis for at least 50% of their hospital stay were assigned to the combination group. Patients receiving either form of VTE prophylaxis for <50% of their hospital stay were considered to be without prophylaxis. Pharmacologic prophylaxis was defined by the use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) 5000 units subcutaneously (sq) 3 times daily or twice daily (bid), low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) 30 mg sq bid or 40 mg every day (qd), or fondaparinux 2.5 mg qd. Mechanical prophylaxis was defined by the use of a sequential compression device (SCD). The study was approved by the University of Tennessee Institutional Review Board.

Patient demographics including age, sex, race, height, and weight were documented with a body mass index (BMI) calculated for each patient. Obesity was defined as BMI 30 kg/m2. Risk factors for VTE including obesity, surgery, infection, trauma, malignancy, and history of VTE as well as the etiology of cirrhosis were collected and recorded whenever available based on documentation in the medical chart. Clinical data including lowest serum albumin, highest total bilirubin, highest INR, and platelets on admission were recorded. Severity of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy were documented. Child‐Pugh score and stage as well as Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score were calculated. In‐hospital VTE, bleeding events, length of stay, in‐hospital mortality, and the use, type, and number of days of VTE prophylaxis were documented. VTE was defined as deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism diagnosed by venous Doppler ultrasonography, spiral computed tomography (CT) of the chest, or ventilation/perfusion scan. Bleeding was defined by documentation in the medical record plus the administration of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, recombinant factor VIIa, or vitamin K. For patients who experienced a bleed, risk factors for in‐hospital bleeding as defined by American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines 2012 guidelines (CHEST) were documented.[13]

The primary outcome was to describe the use of VTE prophylaxis in CLD patients. Secondary outcomes were to determine the overall incidence of VTE in CLD patients, examine the incidence of VTE based on the utilization of prophylaxis, compare the occurrence of bleeding events in CLD patients based on type of prophylaxis, evaluate the use of mechanical versus pharmacologic prophylaxis based on INR, evaluate length of stay (LOS) and in‐hospital mortality for CLD patients with and without prophylaxis, and evaluate 30‐day readmission rate for VTE.

Patients were arbitrarily divided into 2 groups according to the highest INR (1.42.0 or >2.0). Baseline characteristics were compared between the 2 groups. Variables were expressed as mean or median with standard deviation or interquartile range. Categorical values were expressed as percentages and compared using the [2] test or Fisher exact test. Continuous data were compared using Mann‐Whitney U test for nonparametric data or Student t test for parametric data. Significance was defined as P<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 20.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

We identified 410 patients who met inclusion criteria during the study period. Baseline demographics were similar between the 2 groups with the exception of age, which was statistically higher in the INR 1.4 to 2.0 group. The most common etiology of CLD was hepatitis B or C, followed by alcohol, then other causes. Alcoholic CLD was associated with higher INR values (>2.0). Patients with INR >2.0 were found to exhibit lower serum albumin levels and platelets on admission as well as higher total bilirubin and INR values. There was also a significant difference in Child‐Pugh stages B and C, with the INR >2.0 group only having stage C. In addition, the higher INR group had a significantly higher average MELD score (Table 1).

| Characteristic | INR1.42.0, n=251 | INR>2.0, n=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, yearsSD | 55.710.4 | 53.310.1 | 0.017 |

| Male sex | 137 (54.6) | 99 (62.3) | 0.125 |

| BMISD | 29.17.3 | 30.37.7 | 0.103 |

| Race | |||

| African American | 99 (39.4) | 53 (33.3) | 0.212 |

| White | 139 (55.4) | 99 (62.3) | 0.169 |

| Other | 13 (5.2) | 7 (4.4) | 0.722 |

| Etiology of CLD | |||

| Hepatitis B or C | 127 (50.6) | 70 (44) | 0.194 |

| Alcohol | 59 (23.5) | 57 (35.9) | 0.007 |

| Other | 65 (25.9) | 32 (20.1) | 0.18 |

| VTE risk factors | |||

| Obesity, BMI 30 | 107 (42.6) | 71 (44.6) | 0.687 |

| Surgery | 21 (8.4) | 7 (4.1) | 0.121 |

| Infection | 81 (32.3) | 63 (39.6) | 0.129 |

| Trauma | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.6) | 1.00 |

| Malignancy | 35 (13.9) | 24 (15.1) | 0.746 |

| History of VTE | 6 (2.4) | 4 (2.5) | 1.00 |

| Median number VTE risk factors (range) | 1 (03) | 1 (04) | 0.697 |

| Laboratory values | |||

| AlbuminSD | 2.20.58 | 2.00.53 | <0.001 |

| Tbili, median (IQR) | 2.8 (1.95.0) | 8.1 (5.013.3) | <0.001 |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.51.8) | 2.4 (2.22.9) | <0.001 |

| Admission platelets, median (IQR) | 92 (61141) | 79 (58121) | 0.008 |

| Child Pugh stage | |||

| Class A | 3 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 0.286 |

| Class B | 91 (36.3) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Class C | 157 (62.5) | 159 (100) | <0.001 |

| MELD scoreSD | 18.55.1 | 28.36.3 | <0.001 |

Of the 410 patients included, 225 (55%) patients received thromboprophylaxis. The majority of patients received mechanical prophylaxis (n=154), followed by pharmacologic (n=49), and then a combination of mechanical plus pharmacologic (n=22). For patients receiving pharmacologic either alone or in combination with SCDs, 30 received UFH, 33 received LMWH, 1 patient received fondaparinux, and the remaining 7 received a combination of the agents to total 50% of their hospital stay. For patients with INR >2.0, a significant decrease in overall thromboprophylaxis use was seen compared to those with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (47% vs 60%; P=0.013). Patients with INR >2.0 also received significantly less pharmacologic prophylaxis compared to those with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (3.2% vs 17.5%; P<0.001). No differences in the use of mechanical or combination prophylaxis was seen between the groups (Figure 1).

As shown in Table 2, in‐hospital VTE occurred in 3 patients (0.7%). All 3 patients had a DVT. Of the patients with documented VTE, 1 was Child‐Pugh stage B and 2 were stage C. Fifteen bleeding events occurred (3.7%), 9 on mechanical prophylaxis, 1 on pharmacologic, 3 on combination, and 2 with no prophylaxis. The majority of patients experiencing a bleeding event had an INR >2.0 (P=0.001). Eleven patients out of the 15 were considered to be at high risk of bleeding as defined per CHEST 2012 guidelines,[13] whereas 100% had Child‐Pugh stage C with an average MELD score of 31.77.5. It should be noted that 1 patient experienced a bleeding event after receiving pharmacologic treatment doses for VTE and was subsequently placed on a prophylactic dose without any bleeding complications.

| Characteristic | INR1.42.0, n=251 | INR>2.0, n=159 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| In‐hospital VTE | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.563 |

| Mechanical | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Pharmacologic | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Combination | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| No prophylaxis | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| Bleeding event | 3 (1.2) | 12 (7.5) | 0.001 |

| Mechanical | 2 (0.8) | 7 (4.4) | 0.033 |

| Pharmacologic* | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 0.389 |

| Combination | 1 (0.4) | 2 (1.3) | 0.563 |

| No prophylaxis | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | 0.152 |

| LOS, median (IQR) | 5 (2.98) | 7.2 (413.1) | <0.001 |

| Hospital mortality | 6 (2.4) | 30 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| 30‐day readmission rate for VTE | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.524 |

Longer LOS and higher mortality rates were seen in patients who received prophylaxis compared to those who received no prophylaxis (P<0.001 and P=0.001, respectively). Of the 36 patients who died, 22 received mechanical prophylaxis, 2 received pharmacologic, 5 received a combination, and 7 received no prophylaxis. Longer LOS and higher mortality rates were also seen in patients with INR >2 compared to patients with INR 1.4 to 2.0 (P<0.001 for both) (Table 2). Higher mortality rates were associated with greater severity of disease as defined by Child‐Pugh C classification in all 36 patients (P=0.001) and an average MELD score of 31.87.6. No differences in 30‐day readmission rates for VTE were seen between prophylaxis groups.

DISCUSSION/CONCLUSION

The use of thromboprophylaxis in our study was 55%, which is consistent with the reported rate of 30% to 70% in general hospitalized patients.[17] To our knowledge this is the first study to focus primarily on the use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients. Previous studies have focused on the incidence and risks of VTE in CLD patients,[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10] with only 3 of those studies evaluating the use of pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis as a secondary outcome.[6, 7, 8] The reported use of thromboprophylaxis in these studies ranges from 21% to 25%. Pharmacologic prophylaxis rates were 7% in Northup et al.,[8] 12% in Aldawood et al.,[7] and 9% in Dabbagh et al.,[6] compared to 17% in our study (pharmacologic alone plus combination). Mechanical prophylaxis rates were 14%, 12%, and 16%, respectively, compared to our 38%. None of the previous studies gave a definition for prophylaxis. This is important to note because discrepancies in prophylaxis reporting could lead to significant differences in rates of prophylaxis when comparing these studies to our study.

Despite the higher rates of thromboprophylaxis, the incidence of VTE was 0.7%. Our VTE incidence falls within the reported incidence rate of 0.5% to 6.3%.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10] Similar to Aldawood et al. and Dabbagh et al., we found no significant differences in the incidence of VTE and prophylaxis use.[6, 7] Dabbagh et al. suggest that the incidence of VTE increases as disease severity increases.[6] However, with only 25% of their patients receiving thromboprophylaxis, it is hard to determine if the higher incidence of VTE was due to greater disease severity or the low use of thromboprophylaxis. It is expected that patients with more severe disease are less likely to receive VTE prophylaxis secondary to increases in INR and/or thrombocytopenia. As evidenced in our study, there was a significant decrease in the use of thromboprophylaxis in patients with INR >2.0, driven largely by the significant decrease in the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis. Due to the low incidence of VTE observed, our study lacks adequate power to truly determine the relationship between use of thromboprophylaxis or severity of disease and incidence of VTE.

Nonetheless, we did find a significant correlation between disease severity and bleeding in CLD patients. Although not a new finding in the literature, this result substantiates the claim that the delicate balance and unpredictability of coagulopathy in CLD leads to bleeding events as well as VTE. In our study we had an overall bleeding rate of 3.7%. Patients who experienced a bleeding event had greater disease severity, significantly higher INR, and 73% were considered to be at high risk for an event as defined by CHEST guidelines.[13] The majority of events happened while on mechanical or no prophylaxis. Four patients who received pharmacologic prophylaxis had a bleeding event; however, 1 of those patients bled on VTE pharmacologic treatment dose for VTE found on day 2 of hospital admission. In a recent study by Bechmann et al. looking at the use of LMWH in 84 cirrhotic patients, they report a bleeding rate of 8.3%, a rate that is similar to rates of bleeding in nonanticoagulated cirrhotic patients.[18] In comparison with our study, we had 71 patients receive pharmacologic prophylaxis either alone or in combination and 4 bleeding events, giving an event rate of 5.6%. This rate decreases to 4.2% when considering only prophylactic pharmacologic doses, suggesting that pharmacologic prophylaxis in CLD patients poses a low risk of bleeding. Interestingly enough, an association was found between alcoholic CLD and higher INR (>2.0) in our study. Given that patients with higher INR had increased bleeding events, this introduces a question of whether or not the specific cause of CLD (ie, alcoholic hepatitis) may represent a special risk for bleeding in this population. However, additional studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

To our knowledge, this study is also the first to look at the relationship of thromboprophylaxis use on LOS and mortality in CLD patients. At first glance, the fact that patients who received prophylaxis had both significantly longer LOS and higher mortality rates in our study is concerning. However, it is likely that the increased LOS and mortality in our study is attributed to greater disease severity, as evidenced by higher INRs and Child‐Pugh scores regardless of prophylaxis use or not. Also, a known risk factor for VTE is reduced mobility. Although no standard definition for reduced mobility exists, Barbar et al. define it as anticipated bed rest with bathroom privileges (either because of patient's limitations or on physician's order) for at least 3 days.[19] Due to this known increased risk for VTE, it is expected that patient's with a LOS of 3 days are more likely to receive thromboprophylaxis.

Our study has several limitations. Like other retrospective studies, this study was conducted in 1 medical center and relies on the accuracy of documentation. We relied on patient history and clinical presentation to diagnose CLD without the requirement of histologic diagnosis. However, all patients included in the study had an unquestionable diagnosis by a physician. We used an arbitrary definition and assignment of patients into groups based on the method of VTE prophylaxis utilized due to lack of a definition in the medical literature. There was a possible selection bias for pharmacologic prophylaxis based on patient risk factors for bleeding, such as presence of varices and thrombocytopenia. Also, the inability to ensure that patients with an order for SCDs were actively wearing the device throughout their hospital stay is yet another limitation. Not all patients underwent testing for VTE; therefore, the actual incidence of VTE may be higher than what we found. Only those patients who experienced a bleeding event were assessed for risk factors that predisposed them to bleed, making it hard to correlate those risk factors with the risk of bleeding in all CLD patients.

Despite these limitations, our study has great strengths. This is the first study to focus primarily on the use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients. Therefore, it has the potential to influence and raise awareness on the decisions made involving the management of CLD patients in regard to VTE prophylaxis and will hopefully serve as an impetus for future prospective studies. When comparing this study to other studies looking at the incidence of VTE in CLD patients and the use of prophylaxis, our study sample size is relatively large. Also, by including only those patients with INR of at least 1.4 on admission, our study patients had greater severity of disease, making this study distinctly relevant in the clinical debate of whether or not CLD patients should receive thromboprophylaxis.

In conclusion, the use of thromboprophylaxis in CLD patients is higher in our study than previous reports but remains suboptimal. Although bleeding is an inherent risk factor in CLD independent of VTE prophylaxis, the use of VTE pharmacologic prophylaxis does not appear to increase bleeding in CLD patients with INR 2.0. Further studies focusing on baseline bleeding risks (ie, thrombocytopenia, presence of varices) and the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis are needed to provide additional safety data on the use of pharmacologic prophylaxis in this patient population.

Disclosures: All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. Submission is not under review by any other publication. All authors have not received notification of redundant or duplicate publication. All authors have no financial conflicts of interest. No funding was received for this study or article.

- , , . National hospital discharge survey: 2002 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat 13. 2005;158:1–199.

- , , , . Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(19):1–135.

- , , , et al. The diagnostic approach to acute venous thromboembolism: clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(3):1043–1066.

- , , , , , . Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based case‐control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815.

- , , , , , . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: a nationwide population‐based case‐control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(1):96–101.

- , , , , . Coagulopathy does not protect against venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Chest. 2010;137(5):1145–1149.

- , , , et al. The incidence of venous thromboembolism and practice of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. Thromb J. 2011;9(1):1.

- , , , et al. Coagulopathy does not fully protect hospitalized cirrhosis patients from peripheral venous thromboembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1524–1528.

- , , , , . Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhosis patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(11):3012–3017.

- , , , , , . Venous thromboembolism and liver cirrhosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100(5):259–262.

- , , . Should we give thromboprophylaxis to patients with liver cirrhosis and coagulopathy? HPB. 2009;11(6):459–464.

- , . The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):147–156.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e195S–e226S.

- , . Pharmacologic prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and associated coagulopathies. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(8):658–63.

- , , . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(6):873–878.

- , , , et al. A systematic review of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis strategies in patients with renal insufficiency, obesity, or on antiplatelet agents. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):394–401.

- , , , , , . Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the hospitalized medical patient. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(suppl 3):S7–S16.

- , , , , , . Low‐molecular‐weight heparin in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2011;31(1):75–82.

- , , , et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2450–2457.

- , , . National hospital discharge survey: 2002 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat 13. 2005;158:1–199.

- , , , . Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(19):1–135.

- , , , et al. The diagnostic approach to acute venous thromboembolism: clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(3):1043–1066.

- , , , , , . Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population‐based case‐control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):809–815.

- , , , , , . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with liver disease: a nationwide population‐based case‐control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(1):96–101.

- , , , , . Coagulopathy does not protect against venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with chronic liver disease. Chest. 2010;137(5):1145–1149.

- , , , et al. The incidence of venous thromboembolism and practice of deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis in hospitalized cirrhotic patients. Thromb J. 2011;9(1):1.

- , , , et al. Coagulopathy does not fully protect hospitalized cirrhosis patients from peripheral venous thromboembolism. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1524–1528.

- , , , , . Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in cirrhosis patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(11):3012–3017.

- , , , , , . Venous thromboembolism and liver cirrhosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100(5):259–262.

- , , . Should we give thromboprophylaxis to patients with liver cirrhosis and coagulopathy? HPB. 2009;11(6):459–464.

- , . The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):147–156.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e195S–e226S.

- , . Pharmacologic prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis and associated coagulopathies. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012;69(8):658–63.

- , , . Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with chronic liver disease and the utility of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(6):873–878.

- , , , et al. A systematic review of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis strategies in patients with renal insufficiency, obesity, or on antiplatelet agents. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):394–401.

- , , , , , . Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the hospitalized medical patient. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(suppl 3):S7–S16.

- , , , , , . Low‐molecular‐weight heparin in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2011;31(1):75–82.

- , , , et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(11):2450–2457.

© 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine

Stress Testing Effect on ED Visits

More than 9 million people visit the emergency department (ED) annually for evaluation of acute chest pain.[1, 2] Most of these patients are placed on observation status while being assessed for an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Traditionally, serial cardiac enzymes and absence of changes suggestive of ischemia on electrocardiogram rule out ACS. Patients are then stratified based on their presentation and risk factors. However, healthcare providers are not comfortable discharging even low‐risk patients without further testing.[3] Routine treadmill stress testing is usually performed, often complimented by an imaging modality. A negative stress test before discharge reassures both the physician and the patient that the chest pain is not caused by an obstructive coronary lesion.

Patients with chest pain who have been discharged from the ED after ruling out an ACS are frequently readmitted for chest pain within 1 year.[4] It is unclear whether stress testing can prevent these readmissions by preventing return to the ED or by influencing the decision of ED physicians to admit patients for observation.[5, 6, 7] Even if stress testing can reduce ED visits or readmissions, it is not known whether the savings from preventing these visits can offset the initial cost of stress testing. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of stress testing on readmission for chest pain, and to determine whether stress testing can reduce overall costs.

METHODS

Study Population

The hospital's billing database was used to obtain the data. Inclusion criteria included age 18 years or older with index hospitalization between January 2007and July 2009 with International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision admitting diagnoses of chest pain (786.5), chest pain NOSnot otherwise specified (786.50), chest pain NECnot elsewhere classified (786.59) or angina pectoris (413.9). All eligible patients were admitted under observation status. Although observation patients are technically outpatients, they are cared for by inpatient physicians on inpatient units and are otherwise indistinguishable from inpatients. Patients with a discharge diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction at index admission were excluded. Also, patients who had a chest pain admission or an outpatient stress test within the previous 12 months of index admission were excluded.

Data Collection and Outcomes

All data were extracted electronically from the hospital's billing database. For each patient we noted age, sex, race, insurance status, and cardiovascular comorbidities (current smoker, congestive heart failure, valvular disease, pulmonary/circulatory disorders, peripheral vascular disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension). For each admission we ascertained whether or not any type of stress test was performed. We obtained ED and hospitalization costs for chest pain visits within 12 months of index admission from the hospital's cost accounting system. We also obtained corresponding physician charges as well as collection rate from the health system's clinical decision support system.

The primary outcome was the rate of ED visits and readmissions for chest pain within 1 year of the index visit. Secondary outcomes included total annual hospitalization and ED costs. Total annual costs were calculated by summing index costs and follow‐up costs for subsequent ED visits and readmissions.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher exact (categorical) and unpaired t tests/Wilcoxon rank sum (continuous) tests were used to compare the baseline characteristics of patients who received a stress test at index admission to those who did not. To address possible confounding by indication (allocation bias), the association between stress testing and various outcomes was quantified using multivariable logistic (ED visits and readmissions) or linear regression (costs).[8, 9] In addition, we developed a propensity model using conditional logistic regression and matched patients on propensity score using 1:1 greedy matching algorithm with a caliper tolerance of 0.05.[10, 11] For cost analyses, the annual collection rate was applied to all physician charges, and these were added to hospital or ED costs to obtain the total cost of each visit. The average cost of ED visits or readmissions for each group was calculated by dividing the total ED or readmission cost by the number of ED visits and readmissions, respectively. Physician charges were unavailable for approximately one‐third (1487/5163 or 29%) of all hospitalizations; missing charges were estimated using mean imputation, and sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure consistency of inferences between full (imputed) and restricted models.[12, 13, 14] Stata/MP 12.1 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

A total of 3315 patients admitted with chest pain during the study period met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 2376 (71.7%) had a stress test on index admission. Table 1 describes the baseline characteristics of the study population. Receipt of a stress test during index admission was positively associated with white race, private insurance, and number of cardiac comorbidities. The propensity model included these covariates as well as study year, age (80+ vs younger), sex, and smoking status. The C statistic, which quantifies the model's ability to discriminate subjects who received a stress test from those who did not, was 0.63 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.61 to 0.65). Of patients who returned to the ED, we were able to find propensity matches for 69% to create a matched sample of 1776 patients. Of patients who were readmitted, we were able to find matches for 83% to create a matched sample of 186 patients.

| Total, N=3315 | Stress Test Original Admission, N=2376 | No Stress Test, N=939 | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Age, y, mean/SD | 57.5/13.9 | 57.2/12.8 | 58.2/16.2 | 0.10 |

| Male, n (%) | 1505 (45.4) | 1080 (45.5) | 425 (45.3) | 0.94 |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| White | 2082 (62.8) | 1552 (65.3) | 530 (56.4) | |

| Black | 345 (10.4) | 239 (10.1) | 106 (11.3) | |

| Hispanic | 585 (17.7) | 381 (16.0) | 204 (21.7) | |

| Other | 303 (9.1) | 204 (8.6) | 99 (10.5) | |

| Private insurance, n (%) | 1469 (44.3) | 1176 (49.5) | 293 (31.2) | <0.001 |

| No. of cardiovascular comorbidities, mean/SDb | 0.68/0.78 | 0.70/0.78 | 0.64/0.77 | 0.04 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 335 (10.1) | 249 (10.5) | 86 (9.2) | 0.28 |

| Return for chest pain, n (%) | 256 (7.7) | 148 (6.2) | 108 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| All cause return, n (%) | 1279 (38.6) | 819 (34.5) | 460 (49.0) | <0.001 |

| Median time to next chest pain visit, d (25th, 75th percentile) | 69 (6, 180) | 67 (5, 190) | 71 (9, 172) | 0.86 |

| Median time to all cause return, d (25th, 75th percentile) | 92 (27, 198) | 108 (33, 207) | 67 (20, 175) | <0.001 |

| Admitted upon first return for chest pain, n (%) | 112 (43.8) | 62 (41.9) | 50 (46.3) | 0.53 |

Subsequent ED Visits for Chest Pain

Within 1 year, 1279 (38.6%) of all patients returned to the ED, and 256 (7.7%) returned at least once for chest pain. Patients who had a stress test at index admission were less likely to return to ED for chest pain, compared to those who did not get a stress test at admission (6.2% vs 11.5%; P<0.001). The median time to the first subsequent ED visit for any complaint was greater among patients who had a stress test at index admission (108 days vs 67 days, P<0.001), but no effect was noted on time to return for chest complaint (67 days vs 71 days, P=0.86).

In a multivariable model, return to the ED for chest pain was positively associated with self‐reported nonwhite race, insurance with Medicare or Medicaid, and earlier year of index admission (Table 2). Return ED visit was negatively associated with stress testing at index admission (adjusted odds ratio [OR]: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.4 to 0.7; propensity‐matched analysis OR: 0.6, 95% CI: 0.5 to 0.9).

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Stress test | 0.5 | 0.4 0.7 |

| Age >80 years | 1.0 | 0.6 1.6 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1.0 | |

| Male | 1.0 | 0.8 1.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 1.0 | |

| Hispanic | 1.6 | 1.2 2.3 |

| Black | 1.6 | 1.1 2.4 |

| Other | 2.3 | 1.6 3.5 |

| 1 Cardiac comorbiditya | 1.1 | 0.8 1.4 |

| Medicare/Medicaid | 1.5 | 1.1 2.0 |

| Year of index admission | ||

| 2007 | 1.0 | |

| 2008 | 0.8 | 0.6 1.1 |

| 2009 | 0.5 | 0.4 0.7 |

| Smoking | 1.4 | 0.9 2.1 |

Subsequent Readmissions for Chest Pain