User login

Expert tips on retropubic vs. transobturator sling approaches

Midurethral slings – both retropubic and transobturator – have been extensively studied and have evolved to become standard therapies for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The two approaches utilize different routes for sling delivery, but in many other respects, they are similar. Improvements in technique are continually being developed. In this column, Dr. Sokol and Dr. Rardin share key parts of their technique and give their pearls of advice for midurethral sling surgery.

Dr. Sokol’s retropubic approach

I use newer retropubic midurethral slings with smaller trocars that have evolved from first-generation tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) slings. The slings I prefer are placed in a bottom-up fashion, with curved needles passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

I find it helpful to place patients in a high lithotomy position with the legs supported in candy cane stirrups rather than Allen-type stirrups; sling placement is a short procedure with minimal to no risk of neuropathy.

To precisely identify the midurethral point, I use a 16-FR Foley catheter. When the catheter balloon is filled with 10 mm of fluid and gently pulled back, the urethrovesical junction can be identified. Then, by looking at the urethral meatus relative to the bladder neck, I can mark the midpoint between the two.

The suprapubic exit points are marked at two finger-widths lateral to the midline, just above the pubic symphysis. For precise identification of these points, the Foley catheter may be pulled up exactly midline (with the collection bag detached), and the two finger-widths measured on either side. I also aim for the ipsilateral shoulder, imagining a straight line from the urethral meatus to the ipsilateral shoulder on each side. Together, these measurements and visual cues serve as a good safety check.

With two Allis clamps, the vaginal wall on either side of the midline is grasped transversely at the level of the midurethral mark. The clamps will sit a couple of centimeters apart so that the midurethral point can be visualized. This helps to stabilize and elevate the midurethra.

To safely and efficiently develop a paraurethral passage, I perform a hydrodissection and hemostatic injection at the level of the midurethra using a control top 10-cc syringe with a 22-gauge needle. I find that dilute vasopressin saline solution affords better hemostasis than does a dilute lidocaine epinephrine solution, though I use dilute lidocaine if the sling is being done under local anesthesia.

The needle is inserted into a full thickness of skin, to a point shy of the urethra, and 10 cc is rapidly injected. The vaginal epithelium will appear blanched and will balloon out, like a white marble. The process basically lifts the vaginal skin away from the urethra itself, not only creating hemostasis but also providing a zone of safety to help avoid a urethral injury.

With a second syringe identical to the first, I inject 5 cc on each side of the midurethral point, aiming precisely at the underside of the pubic bone toward the ipsilateral shoulder. This creates a hydrodissected tunnel around each side of the midurethra. With a final syringe, I then inject 5 cc on each side suprapubically at my marked exit points.

With a #15 blade scalpel, I make two very small “poke” incisions transversely at the suprapubic sites. The suburethral incision is larger – just over a centimeter – and is made through a full thickness of skin under the area of hydrodissection, but not so deep as to injure the urethra. To finish development of the paraurethral passage, I pass standard Metzenbaum scissors through each hydrodissected tunnel until I feel the underside of the pubic bone, but no further.

For sling placement (after ensuring the bladder is completely empty), I lower the table such that my arm will be at a right angle to pass the sling while standing.

With my index finger underneath the pubic bone, the trocar tip, with the attached sling, is advanced with my thumb directly toward the ipsilateral shoulder just until it pops through the retropubic space. The depth of the trocar tip can be palpated with the index finger of the same hand, which is positioned just below the pelvic bone.

After the sling “pops” into the retropubic space, I remove my hand from the vagina and place it on the abdominal wall at the ipsilateral suprapubic poke site. In one smooth pass, I hug the pubic bone and advance the sling, again aiming directly and consistently at the shoulder. The trocar handle stays steady, never deviating in any direction. Cystoscopy is performed after the sling is placed on both sides to ensure bladder and urethral integrity.

For tensioning, I raise the table back up and, after reinserting the Foley catheter and a Sims retractor, I place my finger in the middle of the sling and pull the suprapubic ends of the sling up until my finger rests right under the urethra.

I then remove the vaginal clamps and use Metzenbaum scissors as a spacer between the sling and the urethra. With the scissors parallel to and right under the Foley catheter, at the same angle as the urethra, I tighten the sling and remove the plastic sheaths.

Dr. Sokol’s transobturator (TOT) approach

I most often use an outside-in sling. I utilize the same patient positioning and identify the midurethral point in the same way as with the retropubic approach.

On the thigh, I identify the adductor longus tendon as well as a little soft spot or depression just beneath the tendon and lateral to the descending ischial pubic ramus. With my thumb on the soft spot, I can actually grasp the adductor longus tendon between my thumb and index finger. This spot, which is also approximately at the level of the clitoris, marks the entry point for sling placement. It is the thinnest point between the groin and the vagina at the level of the midurethra.

I perform a similar hydrodissection under the urethra as I do in a retropubic procedure, though instead of injecting 5 cc’s to the underside of the pubic symphysis on each side, I instead inject toward the obturator internus muscles. I then inject my final syringe of dilute vasopressin saline solution at the groin poke incision sites, directed toward the projected trocar path, as opposed to suprapubically.

After the full-thickness vaginal incision is made with the scalpel, the dissection is performed sharply with Metzenbaum scissors and is more like the dissection done for cystocele repair than for a retropubic sling. Rather than a poke, the midurethral incision is long enough – about 1.5 cm – for me to reach a finger behind the obturator internus muscle after having sharply dissected the suburethral tissue and fascia. The angle of the dissection is more lateral than for a retropubic sling, toward the underside of the descending ischiopubic ramus and obturator internus muscle.

To place the sling, I have one hand with an index finger in the midurethral tunnel under the obturator internus muscle to protect the urethra. The thumb of that same hand is used to push the helical trocar straight through the thigh poke incision with the handle starting at a 35-degree angle from vertical. The trocar tip is pushed until it can no longer go straight and is ready to be tightly turned around the descending ischiopubic ramus with the opposite hand. A distinct pop can be felt as the trocar tip advances through the obturator membrane and muscles. As the tip is advanced, the angle of the trocar is rotated from 35 degrees to vertical, almost perpendicular to the floor. At this point, the tip of the trocar should be guided out of the midurethral tunnel against the opposite index finger.

I utilize the same technique for tensioning a TOT sling as I do the retropubic sling.

Dr. Rardin’s retropubic approach

I continue to use the original TVT sling with a 5-mm stainless steel, mechanically cut trocar and reusable handle. The newer slender needles may advance with less pressure, but I worry about them bending during passage. I feel more assured and comfortable using the older trocars.

I perform retropubic hydrodissection with a spinal needle using a top-down approach. With 40 cc of a very dilute solution of bupivacaine (Marcaine) with epinephrine on each side of the urethra, I create columns of hydrodissected space. Studies are inconsistent about the benefits of hydrodissection, but theoretically, it decreases the risk of bladder injury by pushing the bladder away from the pubic bone, creates effective hemostasis, and can provide analgesia that will be on board when the patient wakes up.

I bring the spinal needle down behind the pubic bone to the location of the urethral incision site, with my finger in the vagina, so I can feel the tip of the needle next to the urethra/Foley catheter. For each side, I will inject 20 cc of the solution in this location, and the other 20 cc as I withdraw the needle upward.

For trocar passage, some surgeons are taught to advance the trocar until a pop is felt, then drop the handle and push upward. I view the maneuver as a consistent, smooth arch; for every degree that I advance the trocar, I drop the handle slightly in order to maintain contact with the back of the pubic bone throughout the pass. I continuously and simultaneously drop the handle and advance the trocar. Contact with the back of the pubic bone is maintained with a slight pulling on the back end of the trocar handle, while the forward hand pushes the trocar upward.

The target that I visualize for a retropubic pass is the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder. A cadaver study showed that if you aim as far lateral as the patient’s outstretched elbow, you can enter the iliac vasculature (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;101:933-6).

If the patient is draped such that I cannot see the ipsilateral shoulder, I ask the anesthesia team to show me. I have also identified and marked the suprapubic points about 2-3 cm from each other on either side of the midline just about the pubic symphysis, but I consider the broader anatomic picture and purposeful visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder to be an essential part of safe technique. In general, it is safer to be more medial than more lateral for the needle passage.

I continue to use a rigid catheter guide to deflect the bladder neck while passing the needles.

Cystoscopy is performed after both needles are placed but not yet pulled through. I fill the bladder until the ureteral orifices appear flattened, which confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles.

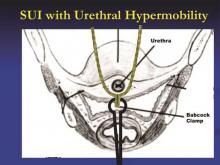

The technique I utilize for adjusting the tension of the TVT sling was taught to me by Dr. Peter L. Rosenblatt of Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Mass. At the midline of the sling, I advance the sheaths just enough so that I can grasp a 2-3 mm “knuckle” of the midportion of the sling with a Babcock clamp. I then pull the sling ends until the Babcock comes into gentle contact with the suburethral tissue. The sheaths encasing the sling are then removed and the Babcock clamp is released to assure a tension-free deployment.

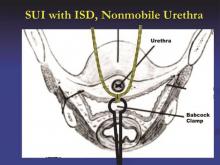

The amount of tape that is pinched with the Babcock – the size of the “knuckle” – determines the tension. For a patient with a more profound problem, such as intrinsic sphincter deficiency or a lack or urethral hypermobility, I will grasp a smaller knuckle.

These steps ensure that the midportion of the tape will not tighten or become deformed under tension. Rather than use a spacer, I like to protect the midportion of the tape and prevent it from being stretched. I find that the approach is reproducible and results in a reliable amount of space between the urethra and sling when the procedure is completed.

Dr. Rardin’s TOT approach

I employ an inside-out technique to the TOT procedure, and I utilize devices with segment of mesh that is shorter – only about 13 cm in length – than the original full-length mesh used in many TOT procedures. Once placed, the ends of the mesh penetrate the obturator membrane and obturator externus but not the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

In a study we presented last year at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting, the shortened tape reduced postoperative groin pain, compared with full-length TOT tape without any reduction in subjective benefit. It appears that with shortened tape, we are anchoring the sling in tissues that provide critical support while avoiding the muscles that relate to the inner thigh/groin pain experienced by some patients. Effectiveness was not reduced, compared with full-length TOT slings.

These shortened slings are distinct from a single-incision sling, which is basically pushed into place. We still pass the needle all the way through a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, and we pull the sling into place as we would any other TOT sling. The difference is that we’re not leaving any mesh in the groin.

I prefer an inside-out approach for two reasons: I always feel that I have more control over where a needle enters than where it exits, and precision is important with suburethral slings. Secondly, the dissection tunnel created for an inside-out pass is much smaller than the tunnel that must be dissected for an outside-in approach. In theory, less dissection means less devascularization, less denervation, and less opportunity for erosion.

Hydrodissection for TOT slings is more minimal and involves less fluid than does hydrodissection for retropubic slings, mainly because we do not want to anesthetize the obturator nerve. I pass the spinal needle from the outside in. At the start, prior to making any incisions, it is important to identify the arcus tendineus, a linear thickening of the superior fascia that is sometimes called the “white line.” This is where the sulcus is affixed to the sidewall. I will be sure to penetrate the sidewall at or above the level of the arcus.

With the TOT approach, the likelihood of bladder injury is so low that I usually drive the trocars all the way through prior to cystoscopy, as opposed to leaving the needles in place as I do with the retropubic approach.

Tensioning is achieved in the same manner, by using the Babcock clamp to avoid distortion of the critical part of the mesh while creating the space needed given the patient’s clinical scenario. It is worth remembering, at this point, that overall risks for retention appear to be lower for obturator slings, compared with retropubic slings.

I place most of my patients receiving retropubic slings in dorsal lithotomy position; but for obturator sling placement, I favor a few degrees into higher lithotomy because this pulls the obturator neurovascular bundle a little further out of the path of the needle.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies. Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. To view a video related to this article, go to SurgeryU at aagl.org/obgyn-news.

Midurethral slings – both retropubic and transobturator – have been extensively studied and have evolved to become standard therapies for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The two approaches utilize different routes for sling delivery, but in many other respects, they are similar. Improvements in technique are continually being developed. In this column, Dr. Sokol and Dr. Rardin share key parts of their technique and give their pearls of advice for midurethral sling surgery.

Dr. Sokol’s retropubic approach

I use newer retropubic midurethral slings with smaller trocars that have evolved from first-generation tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) slings. The slings I prefer are placed in a bottom-up fashion, with curved needles passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

I find it helpful to place patients in a high lithotomy position with the legs supported in candy cane stirrups rather than Allen-type stirrups; sling placement is a short procedure with minimal to no risk of neuropathy.

To precisely identify the midurethral point, I use a 16-FR Foley catheter. When the catheter balloon is filled with 10 mm of fluid and gently pulled back, the urethrovesical junction can be identified. Then, by looking at the urethral meatus relative to the bladder neck, I can mark the midpoint between the two.

The suprapubic exit points are marked at two finger-widths lateral to the midline, just above the pubic symphysis. For precise identification of these points, the Foley catheter may be pulled up exactly midline (with the collection bag detached), and the two finger-widths measured on either side. I also aim for the ipsilateral shoulder, imagining a straight line from the urethral meatus to the ipsilateral shoulder on each side. Together, these measurements and visual cues serve as a good safety check.

With two Allis clamps, the vaginal wall on either side of the midline is grasped transversely at the level of the midurethral mark. The clamps will sit a couple of centimeters apart so that the midurethral point can be visualized. This helps to stabilize and elevate the midurethra.

To safely and efficiently develop a paraurethral passage, I perform a hydrodissection and hemostatic injection at the level of the midurethra using a control top 10-cc syringe with a 22-gauge needle. I find that dilute vasopressin saline solution affords better hemostasis than does a dilute lidocaine epinephrine solution, though I use dilute lidocaine if the sling is being done under local anesthesia.

The needle is inserted into a full thickness of skin, to a point shy of the urethra, and 10 cc is rapidly injected. The vaginal epithelium will appear blanched and will balloon out, like a white marble. The process basically lifts the vaginal skin away from the urethra itself, not only creating hemostasis but also providing a zone of safety to help avoid a urethral injury.

With a second syringe identical to the first, I inject 5 cc on each side of the midurethral point, aiming precisely at the underside of the pubic bone toward the ipsilateral shoulder. This creates a hydrodissected tunnel around each side of the midurethra. With a final syringe, I then inject 5 cc on each side suprapubically at my marked exit points.

With a #15 blade scalpel, I make two very small “poke” incisions transversely at the suprapubic sites. The suburethral incision is larger – just over a centimeter – and is made through a full thickness of skin under the area of hydrodissection, but not so deep as to injure the urethra. To finish development of the paraurethral passage, I pass standard Metzenbaum scissors through each hydrodissected tunnel until I feel the underside of the pubic bone, but no further.

For sling placement (after ensuring the bladder is completely empty), I lower the table such that my arm will be at a right angle to pass the sling while standing.

With my index finger underneath the pubic bone, the trocar tip, with the attached sling, is advanced with my thumb directly toward the ipsilateral shoulder just until it pops through the retropubic space. The depth of the trocar tip can be palpated with the index finger of the same hand, which is positioned just below the pelvic bone.

After the sling “pops” into the retropubic space, I remove my hand from the vagina and place it on the abdominal wall at the ipsilateral suprapubic poke site. In one smooth pass, I hug the pubic bone and advance the sling, again aiming directly and consistently at the shoulder. The trocar handle stays steady, never deviating in any direction. Cystoscopy is performed after the sling is placed on both sides to ensure bladder and urethral integrity.

For tensioning, I raise the table back up and, after reinserting the Foley catheter and a Sims retractor, I place my finger in the middle of the sling and pull the suprapubic ends of the sling up until my finger rests right under the urethra.

I then remove the vaginal clamps and use Metzenbaum scissors as a spacer between the sling and the urethra. With the scissors parallel to and right under the Foley catheter, at the same angle as the urethra, I tighten the sling and remove the plastic sheaths.

Dr. Sokol’s transobturator (TOT) approach

I most often use an outside-in sling. I utilize the same patient positioning and identify the midurethral point in the same way as with the retropubic approach.

On the thigh, I identify the adductor longus tendon as well as a little soft spot or depression just beneath the tendon and lateral to the descending ischial pubic ramus. With my thumb on the soft spot, I can actually grasp the adductor longus tendon between my thumb and index finger. This spot, which is also approximately at the level of the clitoris, marks the entry point for sling placement. It is the thinnest point between the groin and the vagina at the level of the midurethra.

I perform a similar hydrodissection under the urethra as I do in a retropubic procedure, though instead of injecting 5 cc’s to the underside of the pubic symphysis on each side, I instead inject toward the obturator internus muscles. I then inject my final syringe of dilute vasopressin saline solution at the groin poke incision sites, directed toward the projected trocar path, as opposed to suprapubically.

After the full-thickness vaginal incision is made with the scalpel, the dissection is performed sharply with Metzenbaum scissors and is more like the dissection done for cystocele repair than for a retropubic sling. Rather than a poke, the midurethral incision is long enough – about 1.5 cm – for me to reach a finger behind the obturator internus muscle after having sharply dissected the suburethral tissue and fascia. The angle of the dissection is more lateral than for a retropubic sling, toward the underside of the descending ischiopubic ramus and obturator internus muscle.

To place the sling, I have one hand with an index finger in the midurethral tunnel under the obturator internus muscle to protect the urethra. The thumb of that same hand is used to push the helical trocar straight through the thigh poke incision with the handle starting at a 35-degree angle from vertical. The trocar tip is pushed until it can no longer go straight and is ready to be tightly turned around the descending ischiopubic ramus with the opposite hand. A distinct pop can be felt as the trocar tip advances through the obturator membrane and muscles. As the tip is advanced, the angle of the trocar is rotated from 35 degrees to vertical, almost perpendicular to the floor. At this point, the tip of the trocar should be guided out of the midurethral tunnel against the opposite index finger.

I utilize the same technique for tensioning a TOT sling as I do the retropubic sling.

Dr. Rardin’s retropubic approach

I continue to use the original TVT sling with a 5-mm stainless steel, mechanically cut trocar and reusable handle. The newer slender needles may advance with less pressure, but I worry about them bending during passage. I feel more assured and comfortable using the older trocars.

I perform retropubic hydrodissection with a spinal needle using a top-down approach. With 40 cc of a very dilute solution of bupivacaine (Marcaine) with epinephrine on each side of the urethra, I create columns of hydrodissected space. Studies are inconsistent about the benefits of hydrodissection, but theoretically, it decreases the risk of bladder injury by pushing the bladder away from the pubic bone, creates effective hemostasis, and can provide analgesia that will be on board when the patient wakes up.

I bring the spinal needle down behind the pubic bone to the location of the urethral incision site, with my finger in the vagina, so I can feel the tip of the needle next to the urethra/Foley catheter. For each side, I will inject 20 cc of the solution in this location, and the other 20 cc as I withdraw the needle upward.

For trocar passage, some surgeons are taught to advance the trocar until a pop is felt, then drop the handle and push upward. I view the maneuver as a consistent, smooth arch; for every degree that I advance the trocar, I drop the handle slightly in order to maintain contact with the back of the pubic bone throughout the pass. I continuously and simultaneously drop the handle and advance the trocar. Contact with the back of the pubic bone is maintained with a slight pulling on the back end of the trocar handle, while the forward hand pushes the trocar upward.

The target that I visualize for a retropubic pass is the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder. A cadaver study showed that if you aim as far lateral as the patient’s outstretched elbow, you can enter the iliac vasculature (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;101:933-6).

If the patient is draped such that I cannot see the ipsilateral shoulder, I ask the anesthesia team to show me. I have also identified and marked the suprapubic points about 2-3 cm from each other on either side of the midline just about the pubic symphysis, but I consider the broader anatomic picture and purposeful visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder to be an essential part of safe technique. In general, it is safer to be more medial than more lateral for the needle passage.

I continue to use a rigid catheter guide to deflect the bladder neck while passing the needles.

Cystoscopy is performed after both needles are placed but not yet pulled through. I fill the bladder until the ureteral orifices appear flattened, which confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles.

The technique I utilize for adjusting the tension of the TVT sling was taught to me by Dr. Peter L. Rosenblatt of Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Mass. At the midline of the sling, I advance the sheaths just enough so that I can grasp a 2-3 mm “knuckle” of the midportion of the sling with a Babcock clamp. I then pull the sling ends until the Babcock comes into gentle contact with the suburethral tissue. The sheaths encasing the sling are then removed and the Babcock clamp is released to assure a tension-free deployment.

The amount of tape that is pinched with the Babcock – the size of the “knuckle” – determines the tension. For a patient with a more profound problem, such as intrinsic sphincter deficiency or a lack or urethral hypermobility, I will grasp a smaller knuckle.

These steps ensure that the midportion of the tape will not tighten or become deformed under tension. Rather than use a spacer, I like to protect the midportion of the tape and prevent it from being stretched. I find that the approach is reproducible and results in a reliable amount of space between the urethra and sling when the procedure is completed.

Dr. Rardin’s TOT approach

I employ an inside-out technique to the TOT procedure, and I utilize devices with segment of mesh that is shorter – only about 13 cm in length – than the original full-length mesh used in many TOT procedures. Once placed, the ends of the mesh penetrate the obturator membrane and obturator externus but not the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

In a study we presented last year at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting, the shortened tape reduced postoperative groin pain, compared with full-length TOT tape without any reduction in subjective benefit. It appears that with shortened tape, we are anchoring the sling in tissues that provide critical support while avoiding the muscles that relate to the inner thigh/groin pain experienced by some patients. Effectiveness was not reduced, compared with full-length TOT slings.

These shortened slings are distinct from a single-incision sling, which is basically pushed into place. We still pass the needle all the way through a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, and we pull the sling into place as we would any other TOT sling. The difference is that we’re not leaving any mesh in the groin.

I prefer an inside-out approach for two reasons: I always feel that I have more control over where a needle enters than where it exits, and precision is important with suburethral slings. Secondly, the dissection tunnel created for an inside-out pass is much smaller than the tunnel that must be dissected for an outside-in approach. In theory, less dissection means less devascularization, less denervation, and less opportunity for erosion.

Hydrodissection for TOT slings is more minimal and involves less fluid than does hydrodissection for retropubic slings, mainly because we do not want to anesthetize the obturator nerve. I pass the spinal needle from the outside in. At the start, prior to making any incisions, it is important to identify the arcus tendineus, a linear thickening of the superior fascia that is sometimes called the “white line.” This is where the sulcus is affixed to the sidewall. I will be sure to penetrate the sidewall at or above the level of the arcus.

With the TOT approach, the likelihood of bladder injury is so low that I usually drive the trocars all the way through prior to cystoscopy, as opposed to leaving the needles in place as I do with the retropubic approach.

Tensioning is achieved in the same manner, by using the Babcock clamp to avoid distortion of the critical part of the mesh while creating the space needed given the patient’s clinical scenario. It is worth remembering, at this point, that overall risks for retention appear to be lower for obturator slings, compared with retropubic slings.

I place most of my patients receiving retropubic slings in dorsal lithotomy position; but for obturator sling placement, I favor a few degrees into higher lithotomy because this pulls the obturator neurovascular bundle a little further out of the path of the needle.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies. Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. To view a video related to this article, go to SurgeryU at aagl.org/obgyn-news.

Midurethral slings – both retropubic and transobturator – have been extensively studied and have evolved to become standard therapies for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The two approaches utilize different routes for sling delivery, but in many other respects, they are similar. Improvements in technique are continually being developed. In this column, Dr. Sokol and Dr. Rardin share key parts of their technique and give their pearls of advice for midurethral sling surgery.

Dr. Sokol’s retropubic approach

I use newer retropubic midurethral slings with smaller trocars that have evolved from first-generation tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) slings. The slings I prefer are placed in a bottom-up fashion, with curved needles passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

I find it helpful to place patients in a high lithotomy position with the legs supported in candy cane stirrups rather than Allen-type stirrups; sling placement is a short procedure with minimal to no risk of neuropathy.

To precisely identify the midurethral point, I use a 16-FR Foley catheter. When the catheter balloon is filled with 10 mm of fluid and gently pulled back, the urethrovesical junction can be identified. Then, by looking at the urethral meatus relative to the bladder neck, I can mark the midpoint between the two.

The suprapubic exit points are marked at two finger-widths lateral to the midline, just above the pubic symphysis. For precise identification of these points, the Foley catheter may be pulled up exactly midline (with the collection bag detached), and the two finger-widths measured on either side. I also aim for the ipsilateral shoulder, imagining a straight line from the urethral meatus to the ipsilateral shoulder on each side. Together, these measurements and visual cues serve as a good safety check.

With two Allis clamps, the vaginal wall on either side of the midline is grasped transversely at the level of the midurethral mark. The clamps will sit a couple of centimeters apart so that the midurethral point can be visualized. This helps to stabilize and elevate the midurethra.

To safely and efficiently develop a paraurethral passage, I perform a hydrodissection and hemostatic injection at the level of the midurethra using a control top 10-cc syringe with a 22-gauge needle. I find that dilute vasopressin saline solution affords better hemostasis than does a dilute lidocaine epinephrine solution, though I use dilute lidocaine if the sling is being done under local anesthesia.

The needle is inserted into a full thickness of skin, to a point shy of the urethra, and 10 cc is rapidly injected. The vaginal epithelium will appear blanched and will balloon out, like a white marble. The process basically lifts the vaginal skin away from the urethra itself, not only creating hemostasis but also providing a zone of safety to help avoid a urethral injury.

With a second syringe identical to the first, I inject 5 cc on each side of the midurethral point, aiming precisely at the underside of the pubic bone toward the ipsilateral shoulder. This creates a hydrodissected tunnel around each side of the midurethra. With a final syringe, I then inject 5 cc on each side suprapubically at my marked exit points.

With a #15 blade scalpel, I make two very small “poke” incisions transversely at the suprapubic sites. The suburethral incision is larger – just over a centimeter – and is made through a full thickness of skin under the area of hydrodissection, but not so deep as to injure the urethra. To finish development of the paraurethral passage, I pass standard Metzenbaum scissors through each hydrodissected tunnel until I feel the underside of the pubic bone, but no further.

For sling placement (after ensuring the bladder is completely empty), I lower the table such that my arm will be at a right angle to pass the sling while standing.

With my index finger underneath the pubic bone, the trocar tip, with the attached sling, is advanced with my thumb directly toward the ipsilateral shoulder just until it pops through the retropubic space. The depth of the trocar tip can be palpated with the index finger of the same hand, which is positioned just below the pelvic bone.

After the sling “pops” into the retropubic space, I remove my hand from the vagina and place it on the abdominal wall at the ipsilateral suprapubic poke site. In one smooth pass, I hug the pubic bone and advance the sling, again aiming directly and consistently at the shoulder. The trocar handle stays steady, never deviating in any direction. Cystoscopy is performed after the sling is placed on both sides to ensure bladder and urethral integrity.

For tensioning, I raise the table back up and, after reinserting the Foley catheter and a Sims retractor, I place my finger in the middle of the sling and pull the suprapubic ends of the sling up until my finger rests right under the urethra.

I then remove the vaginal clamps and use Metzenbaum scissors as a spacer between the sling and the urethra. With the scissors parallel to and right under the Foley catheter, at the same angle as the urethra, I tighten the sling and remove the plastic sheaths.

Dr. Sokol’s transobturator (TOT) approach

I most often use an outside-in sling. I utilize the same patient positioning and identify the midurethral point in the same way as with the retropubic approach.

On the thigh, I identify the adductor longus tendon as well as a little soft spot or depression just beneath the tendon and lateral to the descending ischial pubic ramus. With my thumb on the soft spot, I can actually grasp the adductor longus tendon between my thumb and index finger. This spot, which is also approximately at the level of the clitoris, marks the entry point for sling placement. It is the thinnest point between the groin and the vagina at the level of the midurethra.

I perform a similar hydrodissection under the urethra as I do in a retropubic procedure, though instead of injecting 5 cc’s to the underside of the pubic symphysis on each side, I instead inject toward the obturator internus muscles. I then inject my final syringe of dilute vasopressin saline solution at the groin poke incision sites, directed toward the projected trocar path, as opposed to suprapubically.

After the full-thickness vaginal incision is made with the scalpel, the dissection is performed sharply with Metzenbaum scissors and is more like the dissection done for cystocele repair than for a retropubic sling. Rather than a poke, the midurethral incision is long enough – about 1.5 cm – for me to reach a finger behind the obturator internus muscle after having sharply dissected the suburethral tissue and fascia. The angle of the dissection is more lateral than for a retropubic sling, toward the underside of the descending ischiopubic ramus and obturator internus muscle.

To place the sling, I have one hand with an index finger in the midurethral tunnel under the obturator internus muscle to protect the urethra. The thumb of that same hand is used to push the helical trocar straight through the thigh poke incision with the handle starting at a 35-degree angle from vertical. The trocar tip is pushed until it can no longer go straight and is ready to be tightly turned around the descending ischiopubic ramus with the opposite hand. A distinct pop can be felt as the trocar tip advances through the obturator membrane and muscles. As the tip is advanced, the angle of the trocar is rotated from 35 degrees to vertical, almost perpendicular to the floor. At this point, the tip of the trocar should be guided out of the midurethral tunnel against the opposite index finger.

I utilize the same technique for tensioning a TOT sling as I do the retropubic sling.

Dr. Rardin’s retropubic approach

I continue to use the original TVT sling with a 5-mm stainless steel, mechanically cut trocar and reusable handle. The newer slender needles may advance with less pressure, but I worry about them bending during passage. I feel more assured and comfortable using the older trocars.

I perform retropubic hydrodissection with a spinal needle using a top-down approach. With 40 cc of a very dilute solution of bupivacaine (Marcaine) with epinephrine on each side of the urethra, I create columns of hydrodissected space. Studies are inconsistent about the benefits of hydrodissection, but theoretically, it decreases the risk of bladder injury by pushing the bladder away from the pubic bone, creates effective hemostasis, and can provide analgesia that will be on board when the patient wakes up.

I bring the spinal needle down behind the pubic bone to the location of the urethral incision site, with my finger in the vagina, so I can feel the tip of the needle next to the urethra/Foley catheter. For each side, I will inject 20 cc of the solution in this location, and the other 20 cc as I withdraw the needle upward.

For trocar passage, some surgeons are taught to advance the trocar until a pop is felt, then drop the handle and push upward. I view the maneuver as a consistent, smooth arch; for every degree that I advance the trocar, I drop the handle slightly in order to maintain contact with the back of the pubic bone throughout the pass. I continuously and simultaneously drop the handle and advance the trocar. Contact with the back of the pubic bone is maintained with a slight pulling on the back end of the trocar handle, while the forward hand pushes the trocar upward.

The target that I visualize for a retropubic pass is the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder. A cadaver study showed that if you aim as far lateral as the patient’s outstretched elbow, you can enter the iliac vasculature (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;101:933-6).

If the patient is draped such that I cannot see the ipsilateral shoulder, I ask the anesthesia team to show me. I have also identified and marked the suprapubic points about 2-3 cm from each other on either side of the midline just about the pubic symphysis, but I consider the broader anatomic picture and purposeful visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder to be an essential part of safe technique. In general, it is safer to be more medial than more lateral for the needle passage.

I continue to use a rigid catheter guide to deflect the bladder neck while passing the needles.

Cystoscopy is performed after both needles are placed but not yet pulled through. I fill the bladder until the ureteral orifices appear flattened, which confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles.

The technique I utilize for adjusting the tension of the TVT sling was taught to me by Dr. Peter L. Rosenblatt of Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Mass. At the midline of the sling, I advance the sheaths just enough so that I can grasp a 2-3 mm “knuckle” of the midportion of the sling with a Babcock clamp. I then pull the sling ends until the Babcock comes into gentle contact with the suburethral tissue. The sheaths encasing the sling are then removed and the Babcock clamp is released to assure a tension-free deployment.

The amount of tape that is pinched with the Babcock – the size of the “knuckle” – determines the tension. For a patient with a more profound problem, such as intrinsic sphincter deficiency or a lack or urethral hypermobility, I will grasp a smaller knuckle.

These steps ensure that the midportion of the tape will not tighten or become deformed under tension. Rather than use a spacer, I like to protect the midportion of the tape and prevent it from being stretched. I find that the approach is reproducible and results in a reliable amount of space between the urethra and sling when the procedure is completed.

Dr. Rardin’s TOT approach

I employ an inside-out technique to the TOT procedure, and I utilize devices with segment of mesh that is shorter – only about 13 cm in length – than the original full-length mesh used in many TOT procedures. Once placed, the ends of the mesh penetrate the obturator membrane and obturator externus but not the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

In a study we presented last year at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting, the shortened tape reduced postoperative groin pain, compared with full-length TOT tape without any reduction in subjective benefit. It appears that with shortened tape, we are anchoring the sling in tissues that provide critical support while avoiding the muscles that relate to the inner thigh/groin pain experienced by some patients. Effectiveness was not reduced, compared with full-length TOT slings.

These shortened slings are distinct from a single-incision sling, which is basically pushed into place. We still pass the needle all the way through a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, and we pull the sling into place as we would any other TOT sling. The difference is that we’re not leaving any mesh in the groin.

I prefer an inside-out approach for two reasons: I always feel that I have more control over where a needle enters than where it exits, and precision is important with suburethral slings. Secondly, the dissection tunnel created for an inside-out pass is much smaller than the tunnel that must be dissected for an outside-in approach. In theory, less dissection means less devascularization, less denervation, and less opportunity for erosion.

Hydrodissection for TOT slings is more minimal and involves less fluid than does hydrodissection for retropubic slings, mainly because we do not want to anesthetize the obturator nerve. I pass the spinal needle from the outside in. At the start, prior to making any incisions, it is important to identify the arcus tendineus, a linear thickening of the superior fascia that is sometimes called the “white line.” This is where the sulcus is affixed to the sidewall. I will be sure to penetrate the sidewall at or above the level of the arcus.

With the TOT approach, the likelihood of bladder injury is so low that I usually drive the trocars all the way through prior to cystoscopy, as opposed to leaving the needles in place as I do with the retropubic approach.

Tensioning is achieved in the same manner, by using the Babcock clamp to avoid distortion of the critical part of the mesh while creating the space needed given the patient’s clinical scenario. It is worth remembering, at this point, that overall risks for retention appear to be lower for obturator slings, compared with retropubic slings.

I place most of my patients receiving retropubic slings in dorsal lithotomy position; but for obturator sling placement, I favor a few degrees into higher lithotomy because this pulls the obturator neurovascular bundle a little further out of the path of the needle.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies. Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. To view a video related to this article, go to SurgeryU at aagl.org/obgyn-news.

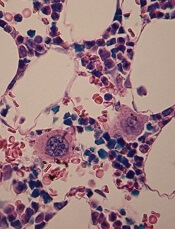

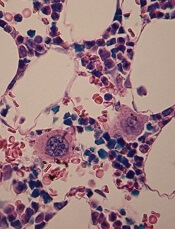

Team discovers new mechanisms of platelet formation

in the bone marrow

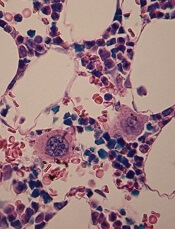

Researchers have found that megakaryocytes can produce platelets via different polyploidization mechanisms.

Experiments suggested that endomitosis is the major megakaryocyte polyploidization mechanism, but megakaryocytes can generate platelets even in the absence of endomitosis—via endocycles and re-replication.

These findings may have implications for treating cancers as well as thrombocytopenia, the researchers said.

They described their discoveries in Developmental Cell.

Marcos Malumbres, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, and his colleagues performed a genetic analysis of endomitosis, in which megakaryocytes become polyploid by entering mitosis but aborting anaphase.

The team studied mice lacking key proteins involved in mitotic entry (Cdk1 and Cdk2), mitotic progression (Aurora B), or mitotic exit (the anaphase-promoting complex [APC/C] cofactor Cdc20) during megakaryocyte maturation.

They found that Aurora B is not required for megakaryocyte maturation, but Cdc20 is. In mice lacking Cdc20, the researchers observed mitotic arrest and severe thrombocytopenia. The team said this suggests endomitosis is the major megakaryocyte polyploidization mechanism in vivo.

So they were surprised to discover that deleting Cdk1 prevents endomitosis but does not hinder platelet formation.

“Whilst the elimination of the main proteins that regulate megakaryocyte growth generates, as we thought, a reduction in the production of platelets, this didn’t happen when we removed Cdk1,” Dr Malumbres said. “[Even] when Cdk1 was absent, the megakaryocytes were able to grow in size in a similar way to normal cells.”

“[Further] analysis revealed that cells deficient in Cdk1 underwent cellular reprogramming towards a process known as endocycles, which can also be seen in other types of cells, such as certain cells in the placenta,” said Marianna Trakala, also of CNIO.

In endocycles, cells successively replicate their genomes without segregating chromosomes during mitosis.

The researchers uncovered an additional mechanism for megakaryocyte polyploidy when they studied mice lacking both Cdk1 and Cdk2. The deletion of both Cdks resulted in aberrant re-replication, in which the genome is replicated more than once per cell cycle, but platelet levels were not affected.

In fact, the team found that the loss of Cdk1 alone or Cdk1 and Cdk2 together can significantly rescue proplatelet formation and increase platelet levels in Cdc20-null mice.

“We immediately asked ourselves if, by reprogramming the cell cycle towards endocycles, we could correct the thrombocytopenia induced in other models,” Dr Malumbres said.

And when the researchers eliminated Cdk1 in Cdc20-null mice with severe thrombocytopenia, they observed an increase in platelet production. Results were similar when the team ablated Cdk1 and Cdk2 in Cdc20-null mice.

In addition to their implications for treating thrombocytopenia, these results could aid the design of cancer treatments, the researchers said. The findings reveal the different requirements that normal or tumor cells have toward cell-cycle regulators.

Specifically, the research suggests that deleting Cdk1 or other cell-cycle proteins is lethal for tumor cells but does not affect megakaryocytes. So drugs that inhibit these proteins could be used to treat malignancies such as pro-megakaryocytic leukemias. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Researchers have found that megakaryocytes can produce platelets via different polyploidization mechanisms.

Experiments suggested that endomitosis is the major megakaryocyte polyploidization mechanism, but megakaryocytes can generate platelets even in the absence of endomitosis—via endocycles and re-replication.

These findings may have implications for treating cancers as well as thrombocytopenia, the researchers said.

They described their discoveries in Developmental Cell.

Marcos Malumbres, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, and his colleagues performed a genetic analysis of endomitosis, in which megakaryocytes become polyploid by entering mitosis but aborting anaphase.

The team studied mice lacking key proteins involved in mitotic entry (Cdk1 and Cdk2), mitotic progression (Aurora B), or mitotic exit (the anaphase-promoting complex [APC/C] cofactor Cdc20) during megakaryocyte maturation.

They found that Aurora B is not required for megakaryocyte maturation, but Cdc20 is. In mice lacking Cdc20, the researchers observed mitotic arrest and severe thrombocytopenia. The team said this suggests endomitosis is the major megakaryocyte polyploidization mechanism in vivo.

So they were surprised to discover that deleting Cdk1 prevents endomitosis but does not hinder platelet formation.

“Whilst the elimination of the main proteins that regulate megakaryocyte growth generates, as we thought, a reduction in the production of platelets, this didn’t happen when we removed Cdk1,” Dr Malumbres said. “[Even] when Cdk1 was absent, the megakaryocytes were able to grow in size in a similar way to normal cells.”

“[Further] analysis revealed that cells deficient in Cdk1 underwent cellular reprogramming towards a process known as endocycles, which can also be seen in other types of cells, such as certain cells in the placenta,” said Marianna Trakala, also of CNIO.

In endocycles, cells successively replicate their genomes without segregating chromosomes during mitosis.

The researchers uncovered an additional mechanism for megakaryocyte polyploidy when they studied mice lacking both Cdk1 and Cdk2. The deletion of both Cdks resulted in aberrant re-replication, in which the genome is replicated more than once per cell cycle, but platelet levels were not affected.

In fact, the team found that the loss of Cdk1 alone or Cdk1 and Cdk2 together can significantly rescue proplatelet formation and increase platelet levels in Cdc20-null mice.

“We immediately asked ourselves if, by reprogramming the cell cycle towards endocycles, we could correct the thrombocytopenia induced in other models,” Dr Malumbres said.

And when the researchers eliminated Cdk1 in Cdc20-null mice with severe thrombocytopenia, they observed an increase in platelet production. Results were similar when the team ablated Cdk1 and Cdk2 in Cdc20-null mice.

In addition to their implications for treating thrombocytopenia, these results could aid the design of cancer treatments, the researchers said. The findings reveal the different requirements that normal or tumor cells have toward cell-cycle regulators.

Specifically, the research suggests that deleting Cdk1 or other cell-cycle proteins is lethal for tumor cells but does not affect megakaryocytes. So drugs that inhibit these proteins could be used to treat malignancies such as pro-megakaryocytic leukemias. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Researchers have found that megakaryocytes can produce platelets via different polyploidization mechanisms.

Experiments suggested that endomitosis is the major megakaryocyte polyploidization mechanism, but megakaryocytes can generate platelets even in the absence of endomitosis—via endocycles and re-replication.

These findings may have implications for treating cancers as well as thrombocytopenia, the researchers said.

They described their discoveries in Developmental Cell.

Marcos Malumbres, PhD, of Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncologicas (CNIO) in Madrid, Spain, and his colleagues performed a genetic analysis of endomitosis, in which megakaryocytes become polyploid by entering mitosis but aborting anaphase.

The team studied mice lacking key proteins involved in mitotic entry (Cdk1 and Cdk2), mitotic progression (Aurora B), or mitotic exit (the anaphase-promoting complex [APC/C] cofactor Cdc20) during megakaryocyte maturation.

They found that Aurora B is not required for megakaryocyte maturation, but Cdc20 is. In mice lacking Cdc20, the researchers observed mitotic arrest and severe thrombocytopenia. The team said this suggests endomitosis is the major megakaryocyte polyploidization mechanism in vivo.

So they were surprised to discover that deleting Cdk1 prevents endomitosis but does not hinder platelet formation.

“Whilst the elimination of the main proteins that regulate megakaryocyte growth generates, as we thought, a reduction in the production of platelets, this didn’t happen when we removed Cdk1,” Dr Malumbres said. “[Even] when Cdk1 was absent, the megakaryocytes were able to grow in size in a similar way to normal cells.”

“[Further] analysis revealed that cells deficient in Cdk1 underwent cellular reprogramming towards a process known as endocycles, which can also be seen in other types of cells, such as certain cells in the placenta,” said Marianna Trakala, also of CNIO.

In endocycles, cells successively replicate their genomes without segregating chromosomes during mitosis.

The researchers uncovered an additional mechanism for megakaryocyte polyploidy when they studied mice lacking both Cdk1 and Cdk2. The deletion of both Cdks resulted in aberrant re-replication, in which the genome is replicated more than once per cell cycle, but platelet levels were not affected.

In fact, the team found that the loss of Cdk1 alone or Cdk1 and Cdk2 together can significantly rescue proplatelet formation and increase platelet levels in Cdc20-null mice.

“We immediately asked ourselves if, by reprogramming the cell cycle towards endocycles, we could correct the thrombocytopenia induced in other models,” Dr Malumbres said.

And when the researchers eliminated Cdk1 in Cdc20-null mice with severe thrombocytopenia, they observed an increase in platelet production. Results were similar when the team ablated Cdk1 and Cdk2 in Cdc20-null mice.

In addition to their implications for treating thrombocytopenia, these results could aid the design of cancer treatments, the researchers said. The findings reveal the different requirements that normal or tumor cells have toward cell-cycle regulators.

Specifically, the research suggests that deleting Cdk1 or other cell-cycle proteins is lethal for tumor cells but does not affect megakaryocytes. So drugs that inhibit these proteins could be used to treat malignancies such as pro-megakaryocytic leukemias. ![]()

Fusion protein fights resistant ALL

In a preclinical study, a fusion protein targeted treatment-resistant leukemia, demonstrating superiority over both chemotherapy and radiation.

The protein, CD19L-sTRAIL, induced apoptosis in radiation-resistant cells from patients with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and in

mouse models of the disease.

Additionally, mice that received CD19L-sTRAIL had significantly longer event-free survival than mice that received chemotherapy.

An account of this study appears in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Study investigators knew that TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) can cause apoptosis in cancer cells by binding to TRAIL-receptor 1 and TRAIL-receptor 2.

“TRAIL is a naturally occurring part of the body’s immune system that kills cancer cells without toxicity to normal cells,” said Faith Uckun, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“However, earlier clinical trials using TRAIL as a potential anticancer medicine candidate have not been successful, largely because of its propensity to bind, not only to cancer cells, but also to ‘decoy’ receptors.”

But Dr Uckun and her colleagues had discovered CD19-ligand (CD19L), a natural ligand of human CD19 that is expressed by almost all ALL cells. And they hypothesized that fusing CD19L to the portion of TRAIL that can kill cancer cells (known as sTRAIL) would produce a powerful weapon against leukemia cells.

The resulting fusion protein, CD19L-sTRAIL, would seek out, bind, and destroy only leukemia cells carrying CD19 as the target docking site.

In experiments, the investigators showed that their engineering converted sTRAIL into a much more potent “membrane-anchored” form that is capable of triggering apoptosis, even in the most aggressive and therapy-resistant ALL cells.

“Due to its ability to anchor to the surface of cancer cells via CD19, CD19L-sTRAIL was 100,000-fold more potent than sTRAIL and consistently killed more than 99% of aggressive leukemia cells taken directly from children with ALL—not only in the test tube but also in mice,” Dr Uckun said.

At a 2.1 pM concentration, CD19L-sTRAIL caused 84.0±4.7% apoptosis in leukemia cells from patients with B-precursor ALL, whereas radiation with 2 Gy γ-rays caused 45.0±9.0% apoptosis (P<0.0001). Higher concentrations of CD19L-sTRAIL prompted an apoptosis rate of more than 90%.

In cells from mouse models of B-precursor ALL, 2.1 pM of CD19L-sTRAIL caused 91.4±5.4% apoptosis, compared to 16.0±4.6% with 2 Gy γ-rays (P<0.0001).

In addition, administering 2 or 3 doses of CD19L-sTRAIL significantly improved event-free survival in mice challenged with an otherwise fatal dose of leukemia cells.

The median event-free survival was 17 days in control mice; 20 days in mice treated with either vincristine, dexamethasone, and peg-asparaginase or vincristine, doxorubicin, and peg-asparaginase; and 58 days in mice that received 2- to 3-day treatment with CD19L-sTRAIL (P<0.0001 vs controls; P=0.0002 vs chemo).

The investigators said these results support the clinical potential of CD19L-sTRAIL as a new agent against B-precursor ALL.

“We are hopeful that the knowledge gained from this study will open a new range of effective treatment opportunities for children with recurrent leukemia,” Dr Uckun said. ![]()

In a preclinical study, a fusion protein targeted treatment-resistant leukemia, demonstrating superiority over both chemotherapy and radiation.

The protein, CD19L-sTRAIL, induced apoptosis in radiation-resistant cells from patients with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and in

mouse models of the disease.

Additionally, mice that received CD19L-sTRAIL had significantly longer event-free survival than mice that received chemotherapy.

An account of this study appears in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Study investigators knew that TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) can cause apoptosis in cancer cells by binding to TRAIL-receptor 1 and TRAIL-receptor 2.

“TRAIL is a naturally occurring part of the body’s immune system that kills cancer cells without toxicity to normal cells,” said Faith Uckun, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“However, earlier clinical trials using TRAIL as a potential anticancer medicine candidate have not been successful, largely because of its propensity to bind, not only to cancer cells, but also to ‘decoy’ receptors.”

But Dr Uckun and her colleagues had discovered CD19-ligand (CD19L), a natural ligand of human CD19 that is expressed by almost all ALL cells. And they hypothesized that fusing CD19L to the portion of TRAIL that can kill cancer cells (known as sTRAIL) would produce a powerful weapon against leukemia cells.

The resulting fusion protein, CD19L-sTRAIL, would seek out, bind, and destroy only leukemia cells carrying CD19 as the target docking site.

In experiments, the investigators showed that their engineering converted sTRAIL into a much more potent “membrane-anchored” form that is capable of triggering apoptosis, even in the most aggressive and therapy-resistant ALL cells.

“Due to its ability to anchor to the surface of cancer cells via CD19, CD19L-sTRAIL was 100,000-fold more potent than sTRAIL and consistently killed more than 99% of aggressive leukemia cells taken directly from children with ALL—not only in the test tube but also in mice,” Dr Uckun said.

At a 2.1 pM concentration, CD19L-sTRAIL caused 84.0±4.7% apoptosis in leukemia cells from patients with B-precursor ALL, whereas radiation with 2 Gy γ-rays caused 45.0±9.0% apoptosis (P<0.0001). Higher concentrations of CD19L-sTRAIL prompted an apoptosis rate of more than 90%.

In cells from mouse models of B-precursor ALL, 2.1 pM of CD19L-sTRAIL caused 91.4±5.4% apoptosis, compared to 16.0±4.6% with 2 Gy γ-rays (P<0.0001).

In addition, administering 2 or 3 doses of CD19L-sTRAIL significantly improved event-free survival in mice challenged with an otherwise fatal dose of leukemia cells.

The median event-free survival was 17 days in control mice; 20 days in mice treated with either vincristine, dexamethasone, and peg-asparaginase or vincristine, doxorubicin, and peg-asparaginase; and 58 days in mice that received 2- to 3-day treatment with CD19L-sTRAIL (P<0.0001 vs controls; P=0.0002 vs chemo).

The investigators said these results support the clinical potential of CD19L-sTRAIL as a new agent against B-precursor ALL.

“We are hopeful that the knowledge gained from this study will open a new range of effective treatment opportunities for children with recurrent leukemia,” Dr Uckun said. ![]()

In a preclinical study, a fusion protein targeted treatment-resistant leukemia, demonstrating superiority over both chemotherapy and radiation.

The protein, CD19L-sTRAIL, induced apoptosis in radiation-resistant cells from patients with B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and in

mouse models of the disease.

Additionally, mice that received CD19L-sTRAIL had significantly longer event-free survival than mice that received chemotherapy.

An account of this study appears in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Study investigators knew that TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) can cause apoptosis in cancer cells by binding to TRAIL-receptor 1 and TRAIL-receptor 2.

“TRAIL is a naturally occurring part of the body’s immune system that kills cancer cells without toxicity to normal cells,” said Faith Uckun, MD, PhD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles in California.

“However, earlier clinical trials using TRAIL as a potential anticancer medicine candidate have not been successful, largely because of its propensity to bind, not only to cancer cells, but also to ‘decoy’ receptors.”

But Dr Uckun and her colleagues had discovered CD19-ligand (CD19L), a natural ligand of human CD19 that is expressed by almost all ALL cells. And they hypothesized that fusing CD19L to the portion of TRAIL that can kill cancer cells (known as sTRAIL) would produce a powerful weapon against leukemia cells.

The resulting fusion protein, CD19L-sTRAIL, would seek out, bind, and destroy only leukemia cells carrying CD19 as the target docking site.

In experiments, the investigators showed that their engineering converted sTRAIL into a much more potent “membrane-anchored” form that is capable of triggering apoptosis, even in the most aggressive and therapy-resistant ALL cells.

“Due to its ability to anchor to the surface of cancer cells via CD19, CD19L-sTRAIL was 100,000-fold more potent than sTRAIL and consistently killed more than 99% of aggressive leukemia cells taken directly from children with ALL—not only in the test tube but also in mice,” Dr Uckun said.

At a 2.1 pM concentration, CD19L-sTRAIL caused 84.0±4.7% apoptosis in leukemia cells from patients with B-precursor ALL, whereas radiation with 2 Gy γ-rays caused 45.0±9.0% apoptosis (P<0.0001). Higher concentrations of CD19L-sTRAIL prompted an apoptosis rate of more than 90%.

In cells from mouse models of B-precursor ALL, 2.1 pM of CD19L-sTRAIL caused 91.4±5.4% apoptosis, compared to 16.0±4.6% with 2 Gy γ-rays (P<0.0001).

In addition, administering 2 or 3 doses of CD19L-sTRAIL significantly improved event-free survival in mice challenged with an otherwise fatal dose of leukemia cells.

The median event-free survival was 17 days in control mice; 20 days in mice treated with either vincristine, dexamethasone, and peg-asparaginase or vincristine, doxorubicin, and peg-asparaginase; and 58 days in mice that received 2- to 3-day treatment with CD19L-sTRAIL (P<0.0001 vs controls; P=0.0002 vs chemo).

The investigators said these results support the clinical potential of CD19L-sTRAIL as a new agent against B-precursor ALL.

“We are hopeful that the knowledge gained from this study will open a new range of effective treatment opportunities for children with recurrent leukemia,” Dr Uckun said. ![]()

Product granted orphan designation for GVHD

Credit: PLOS ONE

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has granted orphan drug status to ApoCell for the prevention of graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

ApoCell consists of matched-donor, mononuclear-enriched, early apoptotic cells. It has been shown to immunomodulate macrophages and dendritic cells, both of which are involved in GVHD pathogenesis.

ApoCell showed early promise in a phase 1/2a study, and a phase 2b/3 trial of the product is set to begin this year.

ApoCell, which is under development by Enlivex Therapeutics, received orphan drug designation in the US in 2013.

In the European Union (EU), orphan designation is granted to products intended for the treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of a life-threatening or chronically debilitating disease with a prevalence of no more than 5 in 10,000, with no satisfactory method of diagnosis, prevention, or treatment authorized by the EMA.

Orphan designation in the EU comes with a number of benefits, including protocol assistance and 10-year market exclusivity following regulatory approval.

Phase 1/2a trial of ApoCell

For this study, researchers tested an infusion of ApoCell, in addition to cyclosporine and methotrexate, as prophylaxis for acute GVHD.

The trial enrolled 13 leukemia patients who had a median age of 37 (range, 20-59). All of the patients received an HLA-matched, myeloablative, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a related donor.

All patients engrafted. The median time to neutrophil recovery was 13 days after HSCT (range, 11 to 19), and the median time to platelet recovery was 15 days (range, 11 to 59).

At 100 days post-HSCT, the cumulative incidence of acute grade 2-4 GVHD was 23.1%, and the incidence of acute grade 3-4 GVHD was 15.4%. None of the patients developed acute GVHD beyond day 100.

Among patients who received the 2 higher doses of ApoCell (n=6), the rate of acute grade 2-4 GVHD was 0%.

Ten patients experienced serious adverse events, but 7 were considered unrelated to ApoCell, and 3 were likely unrelated to the treatment.

The nonrelapse mortality rate was 7.7% at both 100 and 180 days after HSCT. The overall survival rate was 92% at 100 days and 85% at 180 days.

The researchers said these results suggest a single infusion of ApoCell is safe and may effectively prevent acute GVHD. ![]()

Credit: PLOS ONE

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has granted orphan drug status to ApoCell for the prevention of graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

ApoCell consists of matched-donor, mononuclear-enriched, early apoptotic cells. It has been shown to immunomodulate macrophages and dendritic cells, both of which are involved in GVHD pathogenesis.

ApoCell showed early promise in a phase 1/2a study, and a phase 2b/3 trial of the product is set to begin this year.

ApoCell, which is under development by Enlivex Therapeutics, received orphan drug designation in the US in 2013.

In the European Union (EU), orphan designation is granted to products intended for the treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of a life-threatening or chronically debilitating disease with a prevalence of no more than 5 in 10,000, with no satisfactory method of diagnosis, prevention, or treatment authorized by the EMA.

Orphan designation in the EU comes with a number of benefits, including protocol assistance and 10-year market exclusivity following regulatory approval.

Phase 1/2a trial of ApoCell

For this study, researchers tested an infusion of ApoCell, in addition to cyclosporine and methotrexate, as prophylaxis for acute GVHD.

The trial enrolled 13 leukemia patients who had a median age of 37 (range, 20-59). All of the patients received an HLA-matched, myeloablative, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a related donor.

All patients engrafted. The median time to neutrophil recovery was 13 days after HSCT (range, 11 to 19), and the median time to platelet recovery was 15 days (range, 11 to 59).

At 100 days post-HSCT, the cumulative incidence of acute grade 2-4 GVHD was 23.1%, and the incidence of acute grade 3-4 GVHD was 15.4%. None of the patients developed acute GVHD beyond day 100.

Among patients who received the 2 higher doses of ApoCell (n=6), the rate of acute grade 2-4 GVHD was 0%.

Ten patients experienced serious adverse events, but 7 were considered unrelated to ApoCell, and 3 were likely unrelated to the treatment.

The nonrelapse mortality rate was 7.7% at both 100 and 180 days after HSCT. The overall survival rate was 92% at 100 days and 85% at 180 days.

The researchers said these results suggest a single infusion of ApoCell is safe and may effectively prevent acute GVHD. ![]()

Credit: PLOS ONE

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has granted orphan drug status to ApoCell for the prevention of graft-vs-host disease (GVHD).

ApoCell consists of matched-donor, mononuclear-enriched, early apoptotic cells. It has been shown to immunomodulate macrophages and dendritic cells, both of which are involved in GVHD pathogenesis.

ApoCell showed early promise in a phase 1/2a study, and a phase 2b/3 trial of the product is set to begin this year.

ApoCell, which is under development by Enlivex Therapeutics, received orphan drug designation in the US in 2013.

In the European Union (EU), orphan designation is granted to products intended for the treatment, prevention, or diagnosis of a life-threatening or chronically debilitating disease with a prevalence of no more than 5 in 10,000, with no satisfactory method of diagnosis, prevention, or treatment authorized by the EMA.

Orphan designation in the EU comes with a number of benefits, including protocol assistance and 10-year market exclusivity following regulatory approval.

Phase 1/2a trial of ApoCell

For this study, researchers tested an infusion of ApoCell, in addition to cyclosporine and methotrexate, as prophylaxis for acute GVHD.

The trial enrolled 13 leukemia patients who had a median age of 37 (range, 20-59). All of the patients received an HLA-matched, myeloablative, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a related donor.

All patients engrafted. The median time to neutrophil recovery was 13 days after HSCT (range, 11 to 19), and the median time to platelet recovery was 15 days (range, 11 to 59).

At 100 days post-HSCT, the cumulative incidence of acute grade 2-4 GVHD was 23.1%, and the incidence of acute grade 3-4 GVHD was 15.4%. None of the patients developed acute GVHD beyond day 100.

Among patients who received the 2 higher doses of ApoCell (n=6), the rate of acute grade 2-4 GVHD was 0%.

Ten patients experienced serious adverse events, but 7 were considered unrelated to ApoCell, and 3 were likely unrelated to the treatment.

The nonrelapse mortality rate was 7.7% at both 100 and 180 days after HSCT. The overall survival rate was 92% at 100 days and 85% at 180 days.

The researchers said these results suggest a single infusion of ApoCell is safe and may effectively prevent acute GVHD. ![]()

NICE recommends rivaroxaban for ACS

Credit: NHS

In its final draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is recommending rivaroxaban (Xarelto) as an option for preventing adverse outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

The agency said it supports use of the factor Xa inhibitor in combination with aspirin and clopidogrel or aspirin alone to prevent atherothrombotic events in ACS patients with elevated cardiac biomarkers.

This includes patients who have had ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs) or non-ST-segment myocardial infarctions (NSTEMIs) but not unstable angina. In unstable angina, damage to the heart is not severe enough to result in the release of biomarkers into the blood, so this condition is not included in the guidance.

“Because rivaroxaban is associated with a higher risk of causing bleeding than clopidogrel in combination with aspirin or aspirin alone, the draft guidance recommends that, before starting treatment, doctors should carry out a careful assessment of a person’s bleeding risk,” said Carole Longson, NICE Health Technology Evaluation Centre Director.

“The decision to start treatment should be made after an informed discussion between the doctor and patient about the benefits and risks of rivaroxaban. Also, because there is limited experience of treatment with rivaroxaban up to 24 months, the draft guidance recommends careful consideration should be given to whether treatment is continued beyond 12 months.”

The final draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it. Once NICE issues its final guidance on a technology, it replaces local recommendations.

Cost and clinical effectiveness

An appraisal committee advising NICE concluded that rivaroxaban given at 2.5 mg twice daily in combination with aspirin plus clopidogrel or with aspirin alone was more effective than aspirin plus clopidogrel or aspirin alone for preventing further cardiovascular deaths and myocardial infarction in patients with ACS and raised cardiac biomarkers.

The committee also found rivaroxaban to be cost-effective. According to Bayer Healthcare (the company co-developing rivaroxaban with Janssen Research & Development, LLC), the base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was £6203 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. The evidence review group’s preferred base-case estimate was £5622 per QALY gained.

The committee said there is uncertainty about the validity of these results, which were based on the ATLAS-ACS 2-TIMI 51 trial, because of the risk of bias resulting from missing trial data and informative censoring.

However, the committee considered that the ICERs presented were all within the range that could be considered cost-effective, and adjusting for the various types of bias that might have occurred was unlikely to increase the ICER to the extent that it would become unacceptable.

The list price of rivaroxaban is £58.88 per 2.5 mg, 56-capsule pack (excluding value-added tax). The license dose is 2.5 mg twice daily, which equates to a price of £2.10 per day.

Assuming a treatment duration of 12 months, total acquisition costs are £766.50. Costs may vary in different settings because of negotiated procurement discounts. ![]()

Credit: NHS

In its final draft guidance, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is recommending rivaroxaban (Xarelto) as an option for preventing adverse outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS).

The agency said it supports use of the factor Xa inhibitor in combination with aspirin and clopidogrel or aspirin alone to prevent atherothrombotic events in ACS patients with elevated cardiac biomarkers.

This includes patients who have had ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs) or non-ST-segment myocardial infarctions (NSTEMIs) but not unstable angina. In unstable angina, damage to the heart is not severe enough to result in the release of biomarkers into the blood, so this condition is not included in the guidance.

“Because rivaroxaban is associated with a higher risk of causing bleeding than clopidogrel in combination with aspirin or aspirin alone, the draft guidance recommends that, before starting treatment, doctors should carry out a careful assessment of a person’s bleeding risk,” said Carole Longson, NICE Health Technology Evaluation Centre Director.

“The decision to start treatment should be made after an informed discussion between the doctor and patient about the benefits and risks of rivaroxaban. Also, because there is limited experience of treatment with rivaroxaban up to 24 months, the draft guidance recommends careful consideration should be given to whether treatment is continued beyond 12 months.”

The final draft guidance is now with consultees, who have the opportunity to appeal against it. Once NICE issues its final guidance on a technology, it replaces local recommendations.

Cost and clinical effectiveness

An appraisal committee advising NICE concluded that rivaroxaban given at 2.5 mg twice daily in combination with aspirin plus clopidogrel or with aspirin alone was more effective than aspirin plus clopidogrel or aspirin alone for preventing further cardiovascular deaths and myocardial infarction in patients with ACS and raised cardiac biomarkers.