User login

LISTEN NOW: Highlights of the March 2015 issue of The Hospitalist

http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2015-March-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3

http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2015-March-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3

http://www.the-hospitalist.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2015-March-Hospitalist-Highlights.mp3

What Is the Best Approach to a Cavitary Lung Lesion?

Case

A 66-year-old homeless man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis due to alcoholism presents to the hospital with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count (CBC) is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion (see Figure 1). What is the best approach to this patient’s cavitary lung lesion?

Overview

Cavitary lung lesions are relatively common findings on chest imaging and often pose a diagnostic challenge to the hospitalist. Having a standard approach to the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion can facilitate an expedited workup.

A lung cavity is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule.1 Cavities usually are accompanied by thick walls, greater than 4 mm. These should be differentiated from cysts, which are not surrounded by consolidation, mass, or nodule, and are accompanied by a thinner wall.2

The differential diagnosis of a cavitary lung lesion is broad and can be delineated into categories of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Figure 2). Infectious causes include bacterial, fungal, and, rarely, parasitic agents. Noninfectious causes encompass malignant, rheumatologic, and other less common etiologies such as infarct related to pulmonary embolism.

The clinical presentation and assessment of risk factors for a particular patient are of the utmost importance in delineating next steps for evaluation and management (see Table 1). For those patients of older age with smoking history, specific occupational or environmental exposures, and weight loss, the most common etiology is neoplasm. Common infectious causes include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, as well as tuberculosis. The approach to diagnosis should be based on a composite of the clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and radiographic appearance of the cavity.

Guidelines for the approach to cavitary lung lesions are lacking, yet a thorough understanding of the initial approach is important for those practicing hospital medicine. Key components in the approach to diagnosis of a solitary cavitary lesion are outlined in this article.

Diagnosis of Infectious Causes

In the initial evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion, it is important to first determine if the cause is an infectious process. The infectious etiologies to consider include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, tuberculosis, and septic emboli. Important components in the clinical presentation include presence of cough, fever, night sweats, chills, and symptoms that have lasted less than one month, as well as comorbid conditions, drug or alcohol abuse, and history of immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, or organ transplant).

Given the public health considerations and impact of treatment, tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in its own category.

Tuberculosis. Given the fact that TB patients require airborne isolation, the disease must be considered early in the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion. Patients with TB often present with more chronic symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Immunocompromised state, travel to endemic regions, and incarceration increase the likelihood of TB. Nontuberculous mycobacterium (i.e., M. kansasii) should also be considered in endemic areas.

For those patients in whom TB is suspected, airborne isolation must be initiated promptly. The provider should obtain three sputum samples for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture when risk factors are present. Most patients with reactivation TB have abnormal chest X-rays, with approximately 20% of those patients having air-fluid levels and the majority of cases affecting the upper lobes.3 Cavities may be seen in patients with primary or reactivation TB.3

Lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia. Lung abscesses are cavities associated with necrosis caused by a microbial infection. The term necrotizing pneumonia typically is used when there are multiple smaller (smaller than 2 cm) associated lung abscesses, although both lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia represent a similar pathophysiologic process and are along the same continuum. Lung abscess is suspected with the presence of predisposing risk factors to aspiration (e.g. alcoholism) and poor dentition. History of cough, fever, putrid sputum, night sweats, and weight loss may indicate subacute or chronic development of a lung abscess. Physical examination might be significant for signs of pneumonia and gingivitis.

Organisms that cause lung abscesses include anaerobes (most common), TB, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), post-influenza illness, endemic fungi, and Nocardia, among others.4 In immunocompromised patients, more common considerations include TB, Mycobacterium avium complex, other mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Nocardia, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, endemic fungi (e.g. Coccidiodes in the Southwest and Histoplasma in the Midwest), and, less commonly, Pneumocystis jiroveci.4 The likelihood of each organism is dependent on the patient’s risk factors. Initial laboratory testing includes sputum and blood cultures, as well as serologic testing for endemic fungi, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Imaging may reveal a cavitary lesion in the dependent pulmonary segments (posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes), at times associated with a pleural effusion or infiltrate. The most common appearance of a lung abscess is an asymmetric cavity with an air-fluid level and a wall with a ragged or smooth border. CT scan is often indicated when X-rays are equivocal and when cases are of uncertain cause or are unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. Bronchoscopy is reserved for patients with an immunocompromising condition, atypical presentation, or lack of response to treatment.

For those cavitary lesions in which there is a high degree of suspicion for lung abscess, empiric treatment should include antibiotics active against anaerobes and MRSA if the patient has risk factors. Patients often receive an empiric trial of antibiotics prior to biopsy unless there are clear indications that the cavitary lung lesion is related to cancer. Lung abscesses typically drain spontaneously, and transthoracic or endobronchial drainage is not usually recommended as initial management due to risk of pneumothorax and formation of bronchopleural fistula.

Lung abscesses should be followed to resolution with serial chest imaging. If the lung abscess does not resolve, it would be appropriate to consult thoracic surgery, interventional radiology, or pulmonary, depending on the location of the abscess and the local expertise with transthoracic or endobronchial drainage and surgical resection.

Septic emboli. Septic emboli are a less common cause of cavitary lung lesions. This entity should be considered in patients with a history of IV drug use or infected indwelling devices (central venous catheters, pacemaker wires, and right-sided prosthetic heart valves). Physical examination should include an assessment for signs of endocarditis and inspection for infected indwelling devices. In patients with IV drug use, the likely pathogen is S. aureus.

Oropharyngeal infection or indwelling catheters may predispose patients to septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, also known as Lemierre’s syndrome, a rare but important cause of septic emboli.5 Laboratory testing includes culture for sputum and blood and culture of the infected device if applicable. On chest X-ray, septic emboli commonly appear as nodules located in the lung periphery. CT scan is more sensitive for detecting cavitation associated with septic emboli.

Diagnosis of Noninfectious Causes

Upon identification of a cavitary lung lesion, noninfectious etiologies must also be entertained. Noninfectious etiologies include malignancy, rheumatologic diseases, pulmonary embolism, and other causes. Important components in the clinical presentation include the presence of constitutional symptoms (fevers, weight loss, night sweats), smoking history, family history, and an otherwise complete review of systems. Physical exam should include evaluation for lymphadenopathy, cachexia, rash, clubbing, and other symptoms pertinent to the suspected etiology.

Malignancy. Perhaps most important among noninfectious causes of cavitary lung lesions is malignancy, and a high index of suspicion is warranted given that it is commonly the first diagnosis to consider overall.2 Cavities can form in primary lung cancers (e.g. bronchogenic carcinomas), lung tumors such as lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma, or in metastatic disease. Cavitation has been detected in 7%-11% of primary lung cancers by plain radiography and in 22% by computed tomography.5 Cancers of squamous cell origin are the most likely to cavitate; this holds true for both primary lung tumors and metastatic tumors.6 Additionally, cavitation portends a worse prognosis.7

Clinicians should review any available prior chest imaging studies to look for a change in the quality or size of a cavitary lung lesion. Neoplasms are typically of variable size with irregular thick walls (greater than 4 mm) on CT scan, with higher specificity for neoplasm in those with a wall thickness greater than 15 mm.2

When the diagnosis is less clear, the decision to embark on more advanced diagnostic methods, such as biopsy, should rest on the provider’s clinical suspicion for a certain disease process. When a lung cancer is suspected, consultation with pulmonary and interventional radiology should be obtained to determine the best approach for biopsy.

Rheumatologic. Less common causes of cavitary lesions include those related to rheumatologic diseases (e.g. granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis). One study demonstrated that cavitary lung nodules occur in 37% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.8

Although uncommon, cavitary nodules can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoidosis. Given that patients with rheumatologic diseases are often treated with immunosuppressive agents, infection must remain high on the differential. Suspicion of a rheumatologic cause should prompt the clinician to obtain appropriate serologic testing and consultation as needed.

Pulmonary embolism. Although often not considered in the evaluation of cavitary lung lesions, pulmonary embolism (PE) can lead to infarction and the formation of a cavitary lesion. Pulmonary infarction has been reported to occur in as many as one third of cases of PE.9 Cavitary lesions also have been described in chronic thromboembolic disease.10

Other. Uncommon causes of cavitary lesions include bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and amyloidosis, among others. The hospitalist should keep a broad differential and involve consultants if the diagnosis remains unclear after initial diagnostic evaluation.

Back to the Case

The patient’s fever and productive cough, in combination with recent travel and location of the cavitary lesion, increase his risk for tuberculosis and endemic fungi, such as Coccidioides. This patient was placed on respiratory isolation with AFBs obtained to rule out TB, with Coccidioides antibodies, Cyptococcal antigen titers, and sputum for fungus sent to evaluate for an endemic fungus. He had a chest CT, which revealed a 17-mm cavitary mass within the right upper lobe that contained an air-fluid level indicating lung abscess. Coccidioides, cryptococcal, fungal sputum, and TB studies were negative.

The patient was treated empirically with clindamycin given the high prevalence of anaerobes in lung abscess. He was followed as an outpatient and had a chest X-ray showing resolution of the lesion at six months. The purpose of the X-ray was two-fold: to monitor the effect of antibiotic treatment and to evaluate for persistence of the cavitation given the neoplastic risk factors of older age and smoking.

Bottom Line

The best approach to a patient with a cavitary lung lesion includes assessing the clinical presentation and risk factors, differentiating infectious from noninfectious causes, and then utilizing this information to further direct the diagnostic evaluation. Consultation with a subspecialist or further testing such as biopsy should be considered if the etiology remains undefined after the initial evaluation.

Drs. Rendon, Pizanis, Montanaro, and Kraai are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

References

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697-722.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(6):744-752.

- Barnes PF, Verdegem TD, Vachon LA, Leedom JM, Overturf GD. Chest roentgenogram in pulmonary tuberculosis. New data on an old test. Chest. 1988;94(2):316-320.

- Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, Browne AS, Pratter MR. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2012;21(3):217-221. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b.

- Gadkowski LB, Stout JE. Cavitary pulmonary disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):305-333.

- Chiu FT. Cavitation in lung cancers. Aust N Z J Med. 1975;5(6):523-530.

- Kolodziejski LS, Dyczek S, Duda K, Góralczyk J, Wysocki WM, Lobaziewicz W. Cavitated tumor as a clinical subentity in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Neoplasma. 2003;50(1):66-73.

- Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, Loire R, Brechot JM. Pulmonary Wegener’s granulomatosis. A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest. 1990;97(4):906-912.

- He H, Stein MW, Zalta B, Haramati LB. Pulmonary infarction: spectrum of findings on multidetector helical CT. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21(1):1-7.

- Harris H, Barraclough R, Davies C, Armstrong I, Kiely DG, van Beek E Jr. Cavitating lung lesions in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Radiol Case Rep. 2008;2(3):11-21.

- Woodring JH, Fried AM, Chuang VP. Solitary cavities of the lung: diagnostic implications of cavity wall thickness. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135(6):1269-1271.

Case

A 66-year-old homeless man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis due to alcoholism presents to the hospital with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count (CBC) is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion (see Figure 1). What is the best approach to this patient’s cavitary lung lesion?

Overview

Cavitary lung lesions are relatively common findings on chest imaging and often pose a diagnostic challenge to the hospitalist. Having a standard approach to the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion can facilitate an expedited workup.

A lung cavity is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule.1 Cavities usually are accompanied by thick walls, greater than 4 mm. These should be differentiated from cysts, which are not surrounded by consolidation, mass, or nodule, and are accompanied by a thinner wall.2

The differential diagnosis of a cavitary lung lesion is broad and can be delineated into categories of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Figure 2). Infectious causes include bacterial, fungal, and, rarely, parasitic agents. Noninfectious causes encompass malignant, rheumatologic, and other less common etiologies such as infarct related to pulmonary embolism.

The clinical presentation and assessment of risk factors for a particular patient are of the utmost importance in delineating next steps for evaluation and management (see Table 1). For those patients of older age with smoking history, specific occupational or environmental exposures, and weight loss, the most common etiology is neoplasm. Common infectious causes include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, as well as tuberculosis. The approach to diagnosis should be based on a composite of the clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and radiographic appearance of the cavity.

Guidelines for the approach to cavitary lung lesions are lacking, yet a thorough understanding of the initial approach is important for those practicing hospital medicine. Key components in the approach to diagnosis of a solitary cavitary lesion are outlined in this article.

Diagnosis of Infectious Causes

In the initial evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion, it is important to first determine if the cause is an infectious process. The infectious etiologies to consider include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, tuberculosis, and septic emboli. Important components in the clinical presentation include presence of cough, fever, night sweats, chills, and symptoms that have lasted less than one month, as well as comorbid conditions, drug or alcohol abuse, and history of immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, or organ transplant).

Given the public health considerations and impact of treatment, tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in its own category.

Tuberculosis. Given the fact that TB patients require airborne isolation, the disease must be considered early in the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion. Patients with TB often present with more chronic symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Immunocompromised state, travel to endemic regions, and incarceration increase the likelihood of TB. Nontuberculous mycobacterium (i.e., M. kansasii) should also be considered in endemic areas.

For those patients in whom TB is suspected, airborne isolation must be initiated promptly. The provider should obtain three sputum samples for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture when risk factors are present. Most patients with reactivation TB have abnormal chest X-rays, with approximately 20% of those patients having air-fluid levels and the majority of cases affecting the upper lobes.3 Cavities may be seen in patients with primary or reactivation TB.3

Lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia. Lung abscesses are cavities associated with necrosis caused by a microbial infection. The term necrotizing pneumonia typically is used when there are multiple smaller (smaller than 2 cm) associated lung abscesses, although both lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia represent a similar pathophysiologic process and are along the same continuum. Lung abscess is suspected with the presence of predisposing risk factors to aspiration (e.g. alcoholism) and poor dentition. History of cough, fever, putrid sputum, night sweats, and weight loss may indicate subacute or chronic development of a lung abscess. Physical examination might be significant for signs of pneumonia and gingivitis.

Organisms that cause lung abscesses include anaerobes (most common), TB, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), post-influenza illness, endemic fungi, and Nocardia, among others.4 In immunocompromised patients, more common considerations include TB, Mycobacterium avium complex, other mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Nocardia, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, endemic fungi (e.g. Coccidiodes in the Southwest and Histoplasma in the Midwest), and, less commonly, Pneumocystis jiroveci.4 The likelihood of each organism is dependent on the patient’s risk factors. Initial laboratory testing includes sputum and blood cultures, as well as serologic testing for endemic fungi, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Imaging may reveal a cavitary lesion in the dependent pulmonary segments (posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes), at times associated with a pleural effusion or infiltrate. The most common appearance of a lung abscess is an asymmetric cavity with an air-fluid level and a wall with a ragged or smooth border. CT scan is often indicated when X-rays are equivocal and when cases are of uncertain cause or are unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. Bronchoscopy is reserved for patients with an immunocompromising condition, atypical presentation, or lack of response to treatment.

For those cavitary lesions in which there is a high degree of suspicion for lung abscess, empiric treatment should include antibiotics active against anaerobes and MRSA if the patient has risk factors. Patients often receive an empiric trial of antibiotics prior to biopsy unless there are clear indications that the cavitary lung lesion is related to cancer. Lung abscesses typically drain spontaneously, and transthoracic or endobronchial drainage is not usually recommended as initial management due to risk of pneumothorax and formation of bronchopleural fistula.

Lung abscesses should be followed to resolution with serial chest imaging. If the lung abscess does not resolve, it would be appropriate to consult thoracic surgery, interventional radiology, or pulmonary, depending on the location of the abscess and the local expertise with transthoracic or endobronchial drainage and surgical resection.

Septic emboli. Septic emboli are a less common cause of cavitary lung lesions. This entity should be considered in patients with a history of IV drug use or infected indwelling devices (central venous catheters, pacemaker wires, and right-sided prosthetic heart valves). Physical examination should include an assessment for signs of endocarditis and inspection for infected indwelling devices. In patients with IV drug use, the likely pathogen is S. aureus.

Oropharyngeal infection or indwelling catheters may predispose patients to septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, also known as Lemierre’s syndrome, a rare but important cause of septic emboli.5 Laboratory testing includes culture for sputum and blood and culture of the infected device if applicable. On chest X-ray, septic emboli commonly appear as nodules located in the lung periphery. CT scan is more sensitive for detecting cavitation associated with septic emboli.

Diagnosis of Noninfectious Causes

Upon identification of a cavitary lung lesion, noninfectious etiologies must also be entertained. Noninfectious etiologies include malignancy, rheumatologic diseases, pulmonary embolism, and other causes. Important components in the clinical presentation include the presence of constitutional symptoms (fevers, weight loss, night sweats), smoking history, family history, and an otherwise complete review of systems. Physical exam should include evaluation for lymphadenopathy, cachexia, rash, clubbing, and other symptoms pertinent to the suspected etiology.

Malignancy. Perhaps most important among noninfectious causes of cavitary lung lesions is malignancy, and a high index of suspicion is warranted given that it is commonly the first diagnosis to consider overall.2 Cavities can form in primary lung cancers (e.g. bronchogenic carcinomas), lung tumors such as lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma, or in metastatic disease. Cavitation has been detected in 7%-11% of primary lung cancers by plain radiography and in 22% by computed tomography.5 Cancers of squamous cell origin are the most likely to cavitate; this holds true for both primary lung tumors and metastatic tumors.6 Additionally, cavitation portends a worse prognosis.7

Clinicians should review any available prior chest imaging studies to look for a change in the quality or size of a cavitary lung lesion. Neoplasms are typically of variable size with irregular thick walls (greater than 4 mm) on CT scan, with higher specificity for neoplasm in those with a wall thickness greater than 15 mm.2

When the diagnosis is less clear, the decision to embark on more advanced diagnostic methods, such as biopsy, should rest on the provider’s clinical suspicion for a certain disease process. When a lung cancer is suspected, consultation with pulmonary and interventional radiology should be obtained to determine the best approach for biopsy.

Rheumatologic. Less common causes of cavitary lesions include those related to rheumatologic diseases (e.g. granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis). One study demonstrated that cavitary lung nodules occur in 37% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.8

Although uncommon, cavitary nodules can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoidosis. Given that patients with rheumatologic diseases are often treated with immunosuppressive agents, infection must remain high on the differential. Suspicion of a rheumatologic cause should prompt the clinician to obtain appropriate serologic testing and consultation as needed.

Pulmonary embolism. Although often not considered in the evaluation of cavitary lung lesions, pulmonary embolism (PE) can lead to infarction and the formation of a cavitary lesion. Pulmonary infarction has been reported to occur in as many as one third of cases of PE.9 Cavitary lesions also have been described in chronic thromboembolic disease.10

Other. Uncommon causes of cavitary lesions include bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and amyloidosis, among others. The hospitalist should keep a broad differential and involve consultants if the diagnosis remains unclear after initial diagnostic evaluation.

Back to the Case

The patient’s fever and productive cough, in combination with recent travel and location of the cavitary lesion, increase his risk for tuberculosis and endemic fungi, such as Coccidioides. This patient was placed on respiratory isolation with AFBs obtained to rule out TB, with Coccidioides antibodies, Cyptococcal antigen titers, and sputum for fungus sent to evaluate for an endemic fungus. He had a chest CT, which revealed a 17-mm cavitary mass within the right upper lobe that contained an air-fluid level indicating lung abscess. Coccidioides, cryptococcal, fungal sputum, and TB studies were negative.

The patient was treated empirically with clindamycin given the high prevalence of anaerobes in lung abscess. He was followed as an outpatient and had a chest X-ray showing resolution of the lesion at six months. The purpose of the X-ray was two-fold: to monitor the effect of antibiotic treatment and to evaluate for persistence of the cavitation given the neoplastic risk factors of older age and smoking.

Bottom Line

The best approach to a patient with a cavitary lung lesion includes assessing the clinical presentation and risk factors, differentiating infectious from noninfectious causes, and then utilizing this information to further direct the diagnostic evaluation. Consultation with a subspecialist or further testing such as biopsy should be considered if the etiology remains undefined after the initial evaluation.

Drs. Rendon, Pizanis, Montanaro, and Kraai are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

References

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697-722.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(6):744-752.

- Barnes PF, Verdegem TD, Vachon LA, Leedom JM, Overturf GD. Chest roentgenogram in pulmonary tuberculosis. New data on an old test. Chest. 1988;94(2):316-320.

- Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, Browne AS, Pratter MR. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2012;21(3):217-221. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b.

- Gadkowski LB, Stout JE. Cavitary pulmonary disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):305-333.

- Chiu FT. Cavitation in lung cancers. Aust N Z J Med. 1975;5(6):523-530.

- Kolodziejski LS, Dyczek S, Duda K, Góralczyk J, Wysocki WM, Lobaziewicz W. Cavitated tumor as a clinical subentity in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Neoplasma. 2003;50(1):66-73.

- Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, Loire R, Brechot JM. Pulmonary Wegener’s granulomatosis. A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest. 1990;97(4):906-912.

- He H, Stein MW, Zalta B, Haramati LB. Pulmonary infarction: spectrum of findings on multidetector helical CT. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21(1):1-7.

- Harris H, Barraclough R, Davies C, Armstrong I, Kiely DG, van Beek E Jr. Cavitating lung lesions in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Radiol Case Rep. 2008;2(3):11-21.

- Woodring JH, Fried AM, Chuang VP. Solitary cavities of the lung: diagnostic implications of cavity wall thickness. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135(6):1269-1271.

Case

A 66-year-old homeless man with a history of smoking and cirrhosis due to alcoholism presents to the hospital with a productive cough and fever for one month. He has traveled around Arizona and New Mexico but has never left the country. His complete blood count (CBC) is notable for a white blood cell count of 13,000. His chest X-ray reveals a 1.7-cm right upper lobe cavitary lung lesion (see Figure 1). What is the best approach to this patient’s cavitary lung lesion?

Overview

Cavitary lung lesions are relatively common findings on chest imaging and often pose a diagnostic challenge to the hospitalist. Having a standard approach to the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion can facilitate an expedited workup.

A lung cavity is defined radiographically as a lucent area contained within a consolidation, mass, or nodule.1 Cavities usually are accompanied by thick walls, greater than 4 mm. These should be differentiated from cysts, which are not surrounded by consolidation, mass, or nodule, and are accompanied by a thinner wall.2

The differential diagnosis of a cavitary lung lesion is broad and can be delineated into categories of infectious and noninfectious etiologies (see Figure 2). Infectious causes include bacterial, fungal, and, rarely, parasitic agents. Noninfectious causes encompass malignant, rheumatologic, and other less common etiologies such as infarct related to pulmonary embolism.

The clinical presentation and assessment of risk factors for a particular patient are of the utmost importance in delineating next steps for evaluation and management (see Table 1). For those patients of older age with smoking history, specific occupational or environmental exposures, and weight loss, the most common etiology is neoplasm. Common infectious causes include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, as well as tuberculosis. The approach to diagnosis should be based on a composite of the clinical presentation, patient characteristics, and radiographic appearance of the cavity.

Guidelines for the approach to cavitary lung lesions are lacking, yet a thorough understanding of the initial approach is important for those practicing hospital medicine. Key components in the approach to diagnosis of a solitary cavitary lesion are outlined in this article.

Diagnosis of Infectious Causes

In the initial evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion, it is important to first determine if the cause is an infectious process. The infectious etiologies to consider include lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia, tuberculosis, and septic emboli. Important components in the clinical presentation include presence of cough, fever, night sweats, chills, and symptoms that have lasted less than one month, as well as comorbid conditions, drug or alcohol abuse, and history of immunocompromise (e.g. HIV, immunosuppressive therapy, or organ transplant).

Given the public health considerations and impact of treatment, tuberculosis (TB) will be discussed in its own category.

Tuberculosis. Given the fact that TB patients require airborne isolation, the disease must be considered early in the evaluation of a cavitary lung lesion. Patients with TB often present with more chronic symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and hemoptysis. Immunocompromised state, travel to endemic regions, and incarceration increase the likelihood of TB. Nontuberculous mycobacterium (i.e., M. kansasii) should also be considered in endemic areas.

For those patients in whom TB is suspected, airborne isolation must be initiated promptly. The provider should obtain three sputum samples for acid-fast bacillus (AFB) smear and culture when risk factors are present. Most patients with reactivation TB have abnormal chest X-rays, with approximately 20% of those patients having air-fluid levels and the majority of cases affecting the upper lobes.3 Cavities may be seen in patients with primary or reactivation TB.3

Lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia. Lung abscesses are cavities associated with necrosis caused by a microbial infection. The term necrotizing pneumonia typically is used when there are multiple smaller (smaller than 2 cm) associated lung abscesses, although both lung abscess and necrotizing pneumonia represent a similar pathophysiologic process and are along the same continuum. Lung abscess is suspected with the presence of predisposing risk factors to aspiration (e.g. alcoholism) and poor dentition. History of cough, fever, putrid sputum, night sweats, and weight loss may indicate subacute or chronic development of a lung abscess. Physical examination might be significant for signs of pneumonia and gingivitis.

Organisms that cause lung abscesses include anaerobes (most common), TB, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), post-influenza illness, endemic fungi, and Nocardia, among others.4 In immunocompromised patients, more common considerations include TB, Mycobacterium avium complex, other mycobacteria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Nocardia, Cryptococcus, Aspergillus, endemic fungi (e.g. Coccidiodes in the Southwest and Histoplasma in the Midwest), and, less commonly, Pneumocystis jiroveci.4 The likelihood of each organism is dependent on the patient’s risk factors. Initial laboratory testing includes sputum and blood cultures, as well as serologic testing for endemic fungi, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Imaging may reveal a cavitary lesion in the dependent pulmonary segments (posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segments of the lower lobes), at times associated with a pleural effusion or infiltrate. The most common appearance of a lung abscess is an asymmetric cavity with an air-fluid level and a wall with a ragged or smooth border. CT scan is often indicated when X-rays are equivocal and when cases are of uncertain cause or are unresponsive to antibiotic therapy. Bronchoscopy is reserved for patients with an immunocompromising condition, atypical presentation, or lack of response to treatment.

For those cavitary lesions in which there is a high degree of suspicion for lung abscess, empiric treatment should include antibiotics active against anaerobes and MRSA if the patient has risk factors. Patients often receive an empiric trial of antibiotics prior to biopsy unless there are clear indications that the cavitary lung lesion is related to cancer. Lung abscesses typically drain spontaneously, and transthoracic or endobronchial drainage is not usually recommended as initial management due to risk of pneumothorax and formation of bronchopleural fistula.

Lung abscesses should be followed to resolution with serial chest imaging. If the lung abscess does not resolve, it would be appropriate to consult thoracic surgery, interventional radiology, or pulmonary, depending on the location of the abscess and the local expertise with transthoracic or endobronchial drainage and surgical resection.

Septic emboli. Septic emboli are a less common cause of cavitary lung lesions. This entity should be considered in patients with a history of IV drug use or infected indwelling devices (central venous catheters, pacemaker wires, and right-sided prosthetic heart valves). Physical examination should include an assessment for signs of endocarditis and inspection for infected indwelling devices. In patients with IV drug use, the likely pathogen is S. aureus.

Oropharyngeal infection or indwelling catheters may predispose patients to septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, also known as Lemierre’s syndrome, a rare but important cause of septic emboli.5 Laboratory testing includes culture for sputum and blood and culture of the infected device if applicable. On chest X-ray, septic emboli commonly appear as nodules located in the lung periphery. CT scan is more sensitive for detecting cavitation associated with septic emboli.

Diagnosis of Noninfectious Causes

Upon identification of a cavitary lung lesion, noninfectious etiologies must also be entertained. Noninfectious etiologies include malignancy, rheumatologic diseases, pulmonary embolism, and other causes. Important components in the clinical presentation include the presence of constitutional symptoms (fevers, weight loss, night sweats), smoking history, family history, and an otherwise complete review of systems. Physical exam should include evaluation for lymphadenopathy, cachexia, rash, clubbing, and other symptoms pertinent to the suspected etiology.

Malignancy. Perhaps most important among noninfectious causes of cavitary lung lesions is malignancy, and a high index of suspicion is warranted given that it is commonly the first diagnosis to consider overall.2 Cavities can form in primary lung cancers (e.g. bronchogenic carcinomas), lung tumors such as lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma, or in metastatic disease. Cavitation has been detected in 7%-11% of primary lung cancers by plain radiography and in 22% by computed tomography.5 Cancers of squamous cell origin are the most likely to cavitate; this holds true for both primary lung tumors and metastatic tumors.6 Additionally, cavitation portends a worse prognosis.7

Clinicians should review any available prior chest imaging studies to look for a change in the quality or size of a cavitary lung lesion. Neoplasms are typically of variable size with irregular thick walls (greater than 4 mm) on CT scan, with higher specificity for neoplasm in those with a wall thickness greater than 15 mm.2

When the diagnosis is less clear, the decision to embark on more advanced diagnostic methods, such as biopsy, should rest on the provider’s clinical suspicion for a certain disease process. When a lung cancer is suspected, consultation with pulmonary and interventional radiology should be obtained to determine the best approach for biopsy.

Rheumatologic. Less common causes of cavitary lesions include those related to rheumatologic diseases (e.g. granulomatosis with polyangiitis, formerly known as Wegener’s granulomatosis). One study demonstrated that cavitary lung nodules occur in 37% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis.8

Although uncommon, cavitary nodules can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis and sarcoidosis. Given that patients with rheumatologic diseases are often treated with immunosuppressive agents, infection must remain high on the differential. Suspicion of a rheumatologic cause should prompt the clinician to obtain appropriate serologic testing and consultation as needed.

Pulmonary embolism. Although often not considered in the evaluation of cavitary lung lesions, pulmonary embolism (PE) can lead to infarction and the formation of a cavitary lesion. Pulmonary infarction has been reported to occur in as many as one third of cases of PE.9 Cavitary lesions also have been described in chronic thromboembolic disease.10

Other. Uncommon causes of cavitary lesions include bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and amyloidosis, among others. The hospitalist should keep a broad differential and involve consultants if the diagnosis remains unclear after initial diagnostic evaluation.

Back to the Case

The patient’s fever and productive cough, in combination with recent travel and location of the cavitary lesion, increase his risk for tuberculosis and endemic fungi, such as Coccidioides. This patient was placed on respiratory isolation with AFBs obtained to rule out TB, with Coccidioides antibodies, Cyptococcal antigen titers, and sputum for fungus sent to evaluate for an endemic fungus. He had a chest CT, which revealed a 17-mm cavitary mass within the right upper lobe that contained an air-fluid level indicating lung abscess. Coccidioides, cryptococcal, fungal sputum, and TB studies were negative.

The patient was treated empirically with clindamycin given the high prevalence of anaerobes in lung abscess. He was followed as an outpatient and had a chest X-ray showing resolution of the lesion at six months. The purpose of the X-ray was two-fold: to monitor the effect of antibiotic treatment and to evaluate for persistence of the cavitation given the neoplastic risk factors of older age and smoking.

Bottom Line

The best approach to a patient with a cavitary lung lesion includes assessing the clinical presentation and risk factors, differentiating infectious from noninfectious causes, and then utilizing this information to further direct the diagnostic evaluation. Consultation with a subspecialist or further testing such as biopsy should be considered if the etiology remains undefined after the initial evaluation.

Drs. Rendon, Pizanis, Montanaro, and Kraai are hospitalists in the department of internal medicine at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque.

References

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697-722.

- Ryu JH, Swensen SJ. Cystic and cavitary lung diseases: focal and diffuse. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(6):744-752.

- Barnes PF, Verdegem TD, Vachon LA, Leedom JM, Overturf GD. Chest roentgenogram in pulmonary tuberculosis. New data on an old test. Chest. 1988;94(2):316-320.

- Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, Browne AS, Pratter MR. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2012;21(3):217-221. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b.

- Gadkowski LB, Stout JE. Cavitary pulmonary disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):305-333.

- Chiu FT. Cavitation in lung cancers. Aust N Z J Med. 1975;5(6):523-530.

- Kolodziejski LS, Dyczek S, Duda K, Góralczyk J, Wysocki WM, Lobaziewicz W. Cavitated tumor as a clinical subentity in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Neoplasma. 2003;50(1):66-73.

- Cordier JF, Valeyre D, Guillevin L, Loire R, Brechot JM. Pulmonary Wegener’s granulomatosis. A clinical and imaging study of 77 cases. Chest. 1990;97(4):906-912.

- He H, Stein MW, Zalta B, Haramati LB. Pulmonary infarction: spectrum of findings on multidetector helical CT. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21(1):1-7.

- Harris H, Barraclough R, Davies C, Armstrong I, Kiely DG, van Beek E Jr. Cavitating lung lesions in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Radiol Case Rep. 2008;2(3):11-21.

- Woodring JH, Fried AM, Chuang VP. Solitary cavities of the lung: diagnostic implications of cavity wall thickness. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135(6):1269-1271.

Hospitalists Are Frontline Providers in Treating Venous Thromboembolism

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

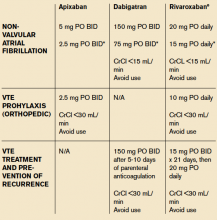

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

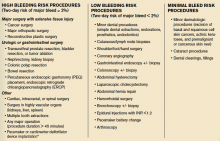

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

“While VTE may not be the No. 1 reason for hospitalization, hospitalists very frequently care for patients with VTE,” says Sowmya Kanikkannan, MD, FACP, SFHM, hospitalist medical director and assistant professor of medicine at Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Stratford, N.J. “Hospitalists usually are the frontline providers that diagnose and manage hospital-acquired VTEs in hospitalized patients.”

Dr. Kanikkannan, a member of Team Hospitalist, sees a wide range of VTE cases caused by two related conditions—deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

“Some patients present with a straightforward diagnosis of DVT, while others have extensive DVT,” she says. “In other instances, patients present with acute PE with or without hemodynamic compromise. I’ve also diagnosed and managed hospital-acquired VTEs in medical patients, as well as post-operatively in surgical co-management.”

It is estimated that between 350,000 to 900,000 Americans are affected by DVT or PE each year, with up to 100,000 dying as a result. Twenty to 50% of people who experience DVT develop long-term complications.1VTE costs the U.S. healthcare system more than $1.5 billion annually.2

As lieutenants in the war against VTE, hospitalists are finding that new treatments, continued efforts to standardize VTE prophylaxis, and increased transparency in performance reporting are the tools needed to combat these common conditions—and hospitalists are being held accountable for optimal patient care.

New Treatments Show Promise

Diagnosing and treating VTE early helps to prevent progression and hemodynamic instability. Although the accepted treatment for VTE used to be heparin, or a low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (Fragmin, Innohep and Lovenox) with a transition to warfarin, three target-specific oral anticoagulants (TSOACs)—dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban—are now being prescribed. The FDA has approved rivaroxaban and apixaban for the prevention of VTE after knee and hip surgery and for treatment of VTE, while dabigatran is FDA approved only for the treatment of VTE. All three are approved for use in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib). A fourth TSOAC, edoxaban, received FDA approval in January for VTE treatment and nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.

“The drawback of warfarin is that patients need frequent international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Discharge planning is time consuming because patients need to be educated on warfarin, and follow-up appointments need to be arranged before discharge to ensure patient safety.”

“Their [TSOACs] ease of administration and easy dosing helps hospitalists to manage patients with VTE more efficiently,” Dr. Kanikkannan says. “Patients like having lab testing less frequently but equal efficacy in treatment.”

Rivaroxaban used to have the most approved indications by the FDA; however, based on three clinical trials—ADVANCE-1, 2, and 3—apixaban has the same six FDA indications as rivaroxaban.

The majority of clinical trials suggest noninferiority or superiority of the oral agents compared to LMWH, and safety appears to be similar across treatment groups, other than an increased risk in bleeding with oral agents (see Table 1).

“The increased risk of bleeding seen in trials is something hospitalists need to consider,” says Yong Lee, PharmD, BCPS, clinical pharmacy specialist at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas. Warfarin is easily reversed; the new anticoagulants don’t have any specific reversal agent (see new table about reversal options). Consequently, the American College of Chest Physicians still recommends unfractionated heparin or a LMWH for VTE prophylaxis. “These agents will still likely remain the best available options to hospitalists for VTE prevention,” he adds.

Julianna Lindsey, MD, MBA, FACP, FHM, chief of staff and hospitalist at Victory Medical Center in McKinney, Texas, says there are instances when it would be helpful to know what the therapeutic level of a TSOAC’s anticoagulation effect is, such as in a patient with active bleeding or one who requires major emergent surgery. But there is no coagulation assay to date that is readily available to test the effect of apixaban; the anticoagulation effect for dabigatran can be roughly estimated by the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and thrombin time (TT), and the anticoagulation effect for rivaroxaban can be roughly estimated by the prothrombin time (PT).

Dr. Lee expects the new FDA approvals to expand the utilization of oral anti-Xa inhibitors in practice. “This will, hopefully, make the new oral anticoagulant market more competitive, driving down their costs,” he says, referring to one of the biggest barriers to current use of these agents. Warfarin still remains the most cost-effective option, despite the need for regular INR monitoring.

“Studies are looking not only at effectiveness but also the safety profile of these anticoagulants,” Dr. Kanikkannan says, as long-term safety data is not yet available on these oral agents.8,9

Researchers also are looking at the comparative effects of other medications. For example, a Journal of Hospital Medicine study concluded that, compared with other anticoagulants, aspirin is associated with a higher risk of DVT following hip fracture repair but similar rates of DVT risk following hip-knee arthroplasty. Bleeding rates with aspirin, however, were substantially lower.10

Improvement Efforts

In an effort to improve VTE prophylaxis in hospitalized patients, The Joint Commission developed a VTE standardized performance measure set in 2009, which has been reported on www.qualitycheck.org since then. The VTE measure set comprises six different measures evaluating the prophylaxis of VTE, treatment of VTE, warfarin discharge education, and hospital-acquired VTE. Since reporting started, most hospitals have implemented VTE risk assessment models and VTE process improvement programs; data trends have shown improvement, says Denise Krusenoski, MSN, RN, CMSRN, CHTS-CP, associate project director at The Joint Commission, which is based in Oakbrook Terrace, Ill.

“While a lot of good, evidence-based data is available, no single VTE risk assessment tool has been prospectively validated as superior,” she says. “Involving key members of medical staff to create and approve protocols based on proven data will increase the buy-in and adoption for using these tools.”

E-Measures Promote Excellence

Many hospitals are now moving from traditional chart abstracting for VTE measures to electronic measures (e-measures), which allow for more rapid and automated reporting of these quality metrics. In order for e-measures to be accurate, documentation necessary for measure computation must be present in defined standardized fields in the medical record. “With no human interpretation, data must be documented in a precise fashion,” Krusenoski says. “Providers will need to be flexible in learning new documentation skills.”

Dr. Lindsey, a member of Team Hospitalist, cautions that e-measures have the potential to increase unwanted events by overutilization of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis and associated hemorrhagic events.

“We have to continue to make sure that our practice of medicine remains based in evidence and not succumb to the pull of getting a check-box ticked,” she warns.

VTE remains a significant problem in hospitalized patients today. Hospitalists should consider the pros and cons of using newer treatment methods over traditional agents. Efforts are under way to improve VTE prophylaxis by standardizing best practice and moving from traditional chart abstracting to using e-measures for performance reporting.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public Health Grand Rounds. Preventing venous thromboembolism. January 15, 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/cdcgrandrounds/archives/2013/january2013.htm. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Dobesh PP. Economic burden of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(8):943-953.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Portman RJ. Apixaban or enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(6):594-604.

- Lassen MR, Raskob GE, Gallus A, Pineo G, Chen D, Hornick P; ADVANCE-2 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after knee replacement (ADVANCE-2): a randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9717):807-815.

- Lassen MR, Gallus A, Raskob GE, Pineo G, Chen D, Ramirez LM; ADVANCE-3 Investigators. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip replacement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2487-2498.

- Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(6):513-523.

- Goldhaber SZ, Leizorovicz A, Kakkar AK, et al. Apixaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis in medically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(23):2167-2177.

- Gonsalves WI, Pruthi RK, Patnaik MM. The new oral anticoagulants in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(5):495-511.

- Holster IL, Valkoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(1):105-112.

- Drescher FS, Sirovich BE, Lee A, Morrison DH, Chiang WH, Larson RJ. Aspirin versus anticoagulation for prevention of venous thromboembolism major lower extremity orthopedic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):579-585.

- Bullock-Palmer RP, Weiss S, Hyman C. Innovative approaches to increase deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis rate resulting in a decrease in hospital-acquired deep vein thrombosis at a tertiary-care teaching hospital. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(2):148-155.

Left Atrial Appendage Closure Noninferior to Warfain for Cardioembolic Event Prophylaxis in Nonvalvular Afibrillation

Clinical question: Is mechanical, left atrial appendage (LAA) closure as effective as warfarin therapy in preventing cardioembolic events in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Anticoagulation with warfarin has long been the standard therapy for prevention of thromboembolic complications of nonvalvular Afib; however, its use is limited by the need for monitoring and lifelong adherence, as well as its many dietary and medication interactions. Prior studies investigating the efficacy of a deployable device intended to close the LAA have shown noninferiority of the device when compared with standard warfarin anticoagulation. This study evaluated LAA closure device efficacy after a 3.8-year interval.

Study design: Randomized, unblinded controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-nine centers in the U.S. and Europe.

Synopsis: Authors randomized 707 participants 18 years or older with nonvalvular Afib and CHADS2 score ≥1 in a 2:1 fashion to the intervention and warfarin therapy groups. The primary outcome was a composite endpoint including stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death. The event rate in the device group was 2.3 per 100 patient-years, compared with 3.8 in the warfarin group. Rate ratio was 0.60, meeting noninferiority criteria. Primary safety events were not statistically different.

Although the authors concluded that LAA device closure was noninferior to warfarin therapy, it should be noted that there was a high dropout rate, especially in the warfarin group, motivated either by a desire to try a novel oral anticoagulant or the perception that warfarin therapy was not beneficial. It should also be noted that device placement involved not only a percutaneous procedure, but also 45 days of aspirin and warfarin therapy initially to promote endothelization, followed by six months of clopidogrel.

Bottom line: Percutaneous device closure of the LAA appears to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the prevention of cardioembolic events over a period of several years, and might be superior.

Clinical question: Is mechanical, left atrial appendage (LAA) closure as effective as warfarin therapy in preventing cardioembolic events in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Anticoagulation with warfarin has long been the standard therapy for prevention of thromboembolic complications of nonvalvular Afib; however, its use is limited by the need for monitoring and lifelong adherence, as well as its many dietary and medication interactions. Prior studies investigating the efficacy of a deployable device intended to close the LAA have shown noninferiority of the device when compared with standard warfarin anticoagulation. This study evaluated LAA closure device efficacy after a 3.8-year interval.

Study design: Randomized, unblinded controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-nine centers in the U.S. and Europe.

Synopsis: Authors randomized 707 participants 18 years or older with nonvalvular Afib and CHADS2 score ≥1 in a 2:1 fashion to the intervention and warfarin therapy groups. The primary outcome was a composite endpoint including stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death. The event rate in the device group was 2.3 per 100 patient-years, compared with 3.8 in the warfarin group. Rate ratio was 0.60, meeting noninferiority criteria. Primary safety events were not statistically different.

Although the authors concluded that LAA device closure was noninferior to warfarin therapy, it should be noted that there was a high dropout rate, especially in the warfarin group, motivated either by a desire to try a novel oral anticoagulant or the perception that warfarin therapy was not beneficial. It should also be noted that device placement involved not only a percutaneous procedure, but also 45 days of aspirin and warfarin therapy initially to promote endothelization, followed by six months of clopidogrel.

Bottom line: Percutaneous device closure of the LAA appears to be noninferior to warfarin therapy in the prevention of cardioembolic events over a period of several years, and might be superior.

Clinical question: Is mechanical, left atrial appendage (LAA) closure as effective as warfarin therapy in preventing cardioembolic events in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (Afib)?

Background: Anticoagulation with warfarin has long been the standard therapy for prevention of thromboembolic complications of nonvalvular Afib; however, its use is limited by the need for monitoring and lifelong adherence, as well as its many dietary and medication interactions. Prior studies investigating the efficacy of a deployable device intended to close the LAA have shown noninferiority of the device when compared with standard warfarin anticoagulation. This study evaluated LAA closure device efficacy after a 3.8-year interval.

Study design: Randomized, unblinded controlled trial.

Setting: Fifty-nine centers in the U.S. and Europe.