User login

Listen Now: Hospital Medicine Intersects with Global Patient Safety

Dr. Phuoc Le of the University of California at San Francisco and Dr. Bijay Achariya of Mass General Hospital in Boston, both practicing global hospitalists, share their perspectives on the US hospitalist movement, how it intersects with the global patient safety movement, and the opportunities presented for hospitalists with a global perspective to make a difference for patients everywhere.

Dr. Phuoc Le of the University of California at San Francisco and Dr. Bijay Achariya of Mass General Hospital in Boston, both practicing global hospitalists, share their perspectives on the US hospitalist movement, how it intersects with the global patient safety movement, and the opportunities presented for hospitalists with a global perspective to make a difference for patients everywhere.

Dr. Phuoc Le of the University of California at San Francisco and Dr. Bijay Achariya of Mass General Hospital in Boston, both practicing global hospitalists, share their perspectives on the US hospitalist movement, how it intersects with the global patient safety movement, and the opportunities presented for hospitalists with a global perspective to make a difference for patients everywhere.

Q&A with the FDA: Implementing the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule

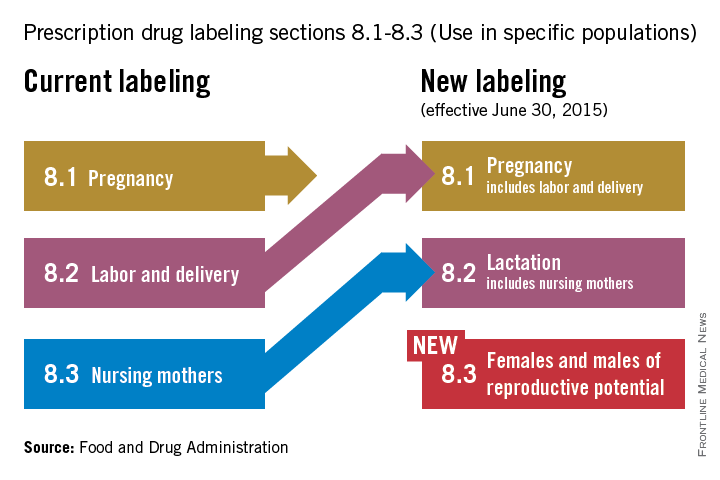

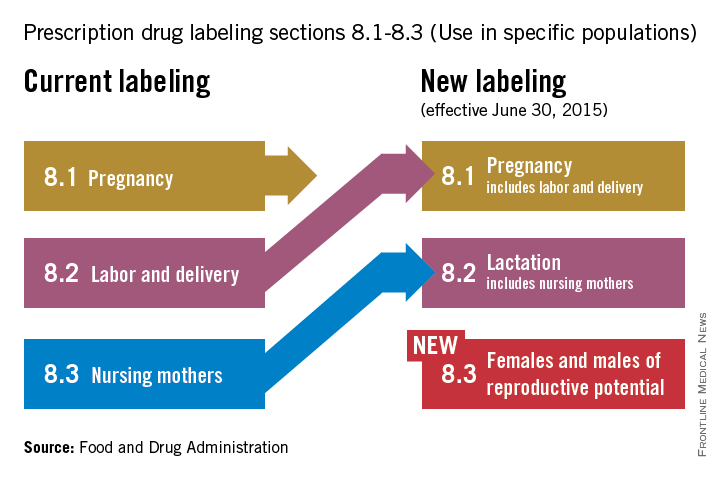

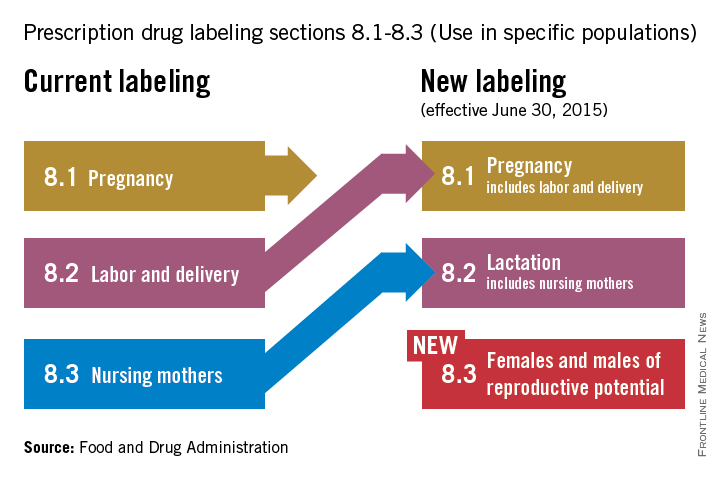

On June 30, pharmaceutical and biological manufacturers will begin implementing the Food and Drug Administration’s revised rules for pregnancy and lactation drug labeling. The Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) amends the Physician Labeling Rule (PLR, issued in 2006) and new labels aimed at providing clearer and more accurate information on drug risks will gradually roll out over the next 5 years.

The new rule – several years in the making – replaces pregnancy categories A, B, C, D, and X with short, integrated summaries that provide physicians with more information for discussing with patients the risks and benefits of a medication. The summaries will be brief and easy to read, and will contain evidence-based information that specifically addresses drug risks for women during pregnancy and lactation, as well as for men and women of reproductive potential. Under the PLLR, the pregnancy subsection of the risk summary will include for the first time information for any drug that has a pregnancy exposure registry.

Dr. John Whyte, director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagment (PASE) at the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, answers questions about the new rule from Ob.Gyn. News journalists and our Drugs, Pregnancy & Lactation columnists.

Question: Instead of the traditional letter categories, prescribers will now have to read the pregnancy and lactation subsections of the labeling. What can the agency do to ensure prescribers are reading all of the new contextual information in the drug label?

Answer: The agency has initiated outreach efforts to help prescribers become familiar with the new information in labeling. The most important information is now under a new heading called Risk Summary. This narrative summary replaces the pregnancy letter categories with a summary of information that is known about a product. The new labeling rule explains, based on available information, the potential benefits and risks for the mother, the fetus, and the breastfeeding child. The decision to replace the pregnancy letter categories with the summary paragraph was reached after extensive consultation with experts and stakeholders who were concerned that the traditional letter categories were overly simplistic.

Q: PLLR praises the value of pregnancy exposure registries and mandates that if a registry exists for an approved product, then the label must include the registry’s website address. There is no requirement, however, that industry actually fund these registries. Why did the agency stop short of requiring companies to provide ongoing support for pregnancy exposure registries?

A: FDA has the authority to require the establishment of pregnancy registries when there is a safety concern that would benefit from the collection of data in a postapproval study, or when a particular product will be used by a large number of females of reproductive age. However, FDA does not have the authority to require companies to fund existing pregnancy exposure registries.

Q: How does the FDA plan to review all of the summary statements of available data regarding reproductive safety considering the breadth of drugs in various therapeutic areas that will need to be reviewed?

A: All labeling changes, including the changes required by the PLLR, must be submitted to the FDA for review and approval. Changes to the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of labeling have been integrated into standard labeling review processes. In addition, the Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health, in the Office of New Drugs, works with the primary review divisions to help coordinate PLLR review processes.

Q: Are the manufacturers of generic drugs expected to “piggyback” the label for a branded molecule with respect to the pregnancy label?

A: Generic drug products (Abbreviated New Drug Applications) are required by regulation to have the “same” labeling as the reference drug listed. When the labeling is revised for the referenced drug, generic drug manufacturers also are required to update their labeling.

Q: In the new system, how will labeling stay up to date when important new data are published on a drug sometimes two to three times a year?

A: When new information becomes available that causes the labeling to be inaccurate, false, or misleading, drug manufacturers are required by regulation to update labeling.

Q: The rule is phased in over time. Drugs already on the market are given more time to switch to the new system. How long will physicians need to deal simultaneously with the old and the new formats?

A: There have been two labeling formats in use for some time as products approved prior to 2001 are not required to conform to either PLLR or PLR. The agency encourages manufacturers to voluntarily convert labeling of older products into PLR format. However, products approved prior to 2001 will be required to remove the pregnancy letter category by June 30, 2018, (3 years after the implementation of the PLLR).

Q: Does the FDA have any plans to address labeling for over-the-counter products in terms of their impact on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential?

A: The PLLR does not apply to over-the-counter products. However, the agency is continually reviewing the safety of products used over the counter, including impacts on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential.

Q: How does the FDA plan to assess over time the usefulness of the new labeling for prescribers and patients and make revisions?

A: The draft guidance was issued concurrently with PLLR. Based on the comments received from the public on the draft, as well as learning from the initial revisions of labeling, the guidance will be revised as needed. Guidance statements issued by FDA are regularly reviewed and revised as needed.

Dr. Whyte, a board-certified internist, is the director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagement at the FDA. Do you have other questions about the PLLR? Send them to [email protected].

On June 30, pharmaceutical and biological manufacturers will begin implementing the Food and Drug Administration’s revised rules for pregnancy and lactation drug labeling. The Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) amends the Physician Labeling Rule (PLR, issued in 2006) and new labels aimed at providing clearer and more accurate information on drug risks will gradually roll out over the next 5 years.

The new rule – several years in the making – replaces pregnancy categories A, B, C, D, and X with short, integrated summaries that provide physicians with more information for discussing with patients the risks and benefits of a medication. The summaries will be brief and easy to read, and will contain evidence-based information that specifically addresses drug risks for women during pregnancy and lactation, as well as for men and women of reproductive potential. Under the PLLR, the pregnancy subsection of the risk summary will include for the first time information for any drug that has a pregnancy exposure registry.

Dr. John Whyte, director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagment (PASE) at the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, answers questions about the new rule from Ob.Gyn. News journalists and our Drugs, Pregnancy & Lactation columnists.

Question: Instead of the traditional letter categories, prescribers will now have to read the pregnancy and lactation subsections of the labeling. What can the agency do to ensure prescribers are reading all of the new contextual information in the drug label?

Answer: The agency has initiated outreach efforts to help prescribers become familiar with the new information in labeling. The most important information is now under a new heading called Risk Summary. This narrative summary replaces the pregnancy letter categories with a summary of information that is known about a product. The new labeling rule explains, based on available information, the potential benefits and risks for the mother, the fetus, and the breastfeeding child. The decision to replace the pregnancy letter categories with the summary paragraph was reached after extensive consultation with experts and stakeholders who were concerned that the traditional letter categories were overly simplistic.

Q: PLLR praises the value of pregnancy exposure registries and mandates that if a registry exists for an approved product, then the label must include the registry’s website address. There is no requirement, however, that industry actually fund these registries. Why did the agency stop short of requiring companies to provide ongoing support for pregnancy exposure registries?

A: FDA has the authority to require the establishment of pregnancy registries when there is a safety concern that would benefit from the collection of data in a postapproval study, or when a particular product will be used by a large number of females of reproductive age. However, FDA does not have the authority to require companies to fund existing pregnancy exposure registries.

Q: How does the FDA plan to review all of the summary statements of available data regarding reproductive safety considering the breadth of drugs in various therapeutic areas that will need to be reviewed?

A: All labeling changes, including the changes required by the PLLR, must be submitted to the FDA for review and approval. Changes to the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of labeling have been integrated into standard labeling review processes. In addition, the Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health, in the Office of New Drugs, works with the primary review divisions to help coordinate PLLR review processes.

Q: Are the manufacturers of generic drugs expected to “piggyback” the label for a branded molecule with respect to the pregnancy label?

A: Generic drug products (Abbreviated New Drug Applications) are required by regulation to have the “same” labeling as the reference drug listed. When the labeling is revised for the referenced drug, generic drug manufacturers also are required to update their labeling.

Q: In the new system, how will labeling stay up to date when important new data are published on a drug sometimes two to three times a year?

A: When new information becomes available that causes the labeling to be inaccurate, false, or misleading, drug manufacturers are required by regulation to update labeling.

Q: The rule is phased in over time. Drugs already on the market are given more time to switch to the new system. How long will physicians need to deal simultaneously with the old and the new formats?

A: There have been two labeling formats in use for some time as products approved prior to 2001 are not required to conform to either PLLR or PLR. The agency encourages manufacturers to voluntarily convert labeling of older products into PLR format. However, products approved prior to 2001 will be required to remove the pregnancy letter category by June 30, 2018, (3 years after the implementation of the PLLR).

Q: Does the FDA have any plans to address labeling for over-the-counter products in terms of their impact on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential?

A: The PLLR does not apply to over-the-counter products. However, the agency is continually reviewing the safety of products used over the counter, including impacts on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential.

Q: How does the FDA plan to assess over time the usefulness of the new labeling for prescribers and patients and make revisions?

A: The draft guidance was issued concurrently with PLLR. Based on the comments received from the public on the draft, as well as learning from the initial revisions of labeling, the guidance will be revised as needed. Guidance statements issued by FDA are regularly reviewed and revised as needed.

Dr. Whyte, a board-certified internist, is the director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagement at the FDA. Do you have other questions about the PLLR? Send them to [email protected].

On June 30, pharmaceutical and biological manufacturers will begin implementing the Food and Drug Administration’s revised rules for pregnancy and lactation drug labeling. The Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR) amends the Physician Labeling Rule (PLR, issued in 2006) and new labels aimed at providing clearer and more accurate information on drug risks will gradually roll out over the next 5 years.

The new rule – several years in the making – replaces pregnancy categories A, B, C, D, and X with short, integrated summaries that provide physicians with more information for discussing with patients the risks and benefits of a medication. The summaries will be brief and easy to read, and will contain evidence-based information that specifically addresses drug risks for women during pregnancy and lactation, as well as for men and women of reproductive potential. Under the PLLR, the pregnancy subsection of the risk summary will include for the first time information for any drug that has a pregnancy exposure registry.

Dr. John Whyte, director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagment (PASE) at the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, answers questions about the new rule from Ob.Gyn. News journalists and our Drugs, Pregnancy & Lactation columnists.

Question: Instead of the traditional letter categories, prescribers will now have to read the pregnancy and lactation subsections of the labeling. What can the agency do to ensure prescribers are reading all of the new contextual information in the drug label?

Answer: The agency has initiated outreach efforts to help prescribers become familiar with the new information in labeling. The most important information is now under a new heading called Risk Summary. This narrative summary replaces the pregnancy letter categories with a summary of information that is known about a product. The new labeling rule explains, based on available information, the potential benefits and risks for the mother, the fetus, and the breastfeeding child. The decision to replace the pregnancy letter categories with the summary paragraph was reached after extensive consultation with experts and stakeholders who were concerned that the traditional letter categories were overly simplistic.

Q: PLLR praises the value of pregnancy exposure registries and mandates that if a registry exists for an approved product, then the label must include the registry’s website address. There is no requirement, however, that industry actually fund these registries. Why did the agency stop short of requiring companies to provide ongoing support for pregnancy exposure registries?

A: FDA has the authority to require the establishment of pregnancy registries when there is a safety concern that would benefit from the collection of data in a postapproval study, or when a particular product will be used by a large number of females of reproductive age. However, FDA does not have the authority to require companies to fund existing pregnancy exposure registries.

Q: How does the FDA plan to review all of the summary statements of available data regarding reproductive safety considering the breadth of drugs in various therapeutic areas that will need to be reviewed?

A: All labeling changes, including the changes required by the PLLR, must be submitted to the FDA for review and approval. Changes to the Pregnancy and Lactation subsections of labeling have been integrated into standard labeling review processes. In addition, the Division of Pediatric and Maternal Health, in the Office of New Drugs, works with the primary review divisions to help coordinate PLLR review processes.

Q: Are the manufacturers of generic drugs expected to “piggyback” the label for a branded molecule with respect to the pregnancy label?

A: Generic drug products (Abbreviated New Drug Applications) are required by regulation to have the “same” labeling as the reference drug listed. When the labeling is revised for the referenced drug, generic drug manufacturers also are required to update their labeling.

Q: In the new system, how will labeling stay up to date when important new data are published on a drug sometimes two to three times a year?

A: When new information becomes available that causes the labeling to be inaccurate, false, or misleading, drug manufacturers are required by regulation to update labeling.

Q: The rule is phased in over time. Drugs already on the market are given more time to switch to the new system. How long will physicians need to deal simultaneously with the old and the new formats?

A: There have been two labeling formats in use for some time as products approved prior to 2001 are not required to conform to either PLLR or PLR. The agency encourages manufacturers to voluntarily convert labeling of older products into PLR format. However, products approved prior to 2001 will be required to remove the pregnancy letter category by June 30, 2018, (3 years after the implementation of the PLLR).

Q: Does the FDA have any plans to address labeling for over-the-counter products in terms of their impact on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential?

A: The PLLR does not apply to over-the-counter products. However, the agency is continually reviewing the safety of products used over the counter, including impacts on pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive potential.

Q: How does the FDA plan to assess over time the usefulness of the new labeling for prescribers and patients and make revisions?

A: The draft guidance was issued concurrently with PLLR. Based on the comments received from the public on the draft, as well as learning from the initial revisions of labeling, the guidance will be revised as needed. Guidance statements issued by FDA are regularly reviewed and revised as needed.

Dr. Whyte, a board-certified internist, is the director of Professional Affairs and Stakeholder Engagement at the FDA. Do you have other questions about the PLLR? Send them to [email protected].

Addressing unmet contraception needs in patients with cancer

Approximately 740,000 women are diagnosed with cancer every year in the United States, and because of improved screening, diagnosis, and treatment, women of reproductive age have an 80%-90% 5-year survival rate. The most common cancers in reproductive age women include breast, thyroid, melanoma, colorectal, and cervical cancers. Fertility intention is a critical topic to discuss with reproductive-age cancer patients. Women with cancer often have unmet contraception needs during and following cancer treatment. Providing women with a desired, effective form of contraception that is appropriate with regard to the cancer is critical.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that pregnancy prevention is not adequately addressed in cancer patients. On the one hand, many patients believe they are no longer fertile because of a combination of the illness and the cancer treatment, and on the other hand, many providers may not be adequately trained to offer their patients the full range of contraceptive options (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;201:191.e1-4). One study demonstrated that discussions around fecundity and contraception are occurring about 50% of the time (J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. Monogr. 2005:98-100).

In response, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine has issued guidelines regarding fertility planning in cancer patients (Fertil. Steril. 2005;83:1622-8). While every patient’s circumstance is unique, recommendations are for patients to avoid pregnancy for at least 1 year beyond the completion of medical and surgical treatment of cancer. For those cancers that are hormone mediated, recommendations are to wait 2-5 years before attempting to conceive (J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2002;24:164-80; J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009; 24: S401-6).

Unless patients are educated about and offered the most effective forms of contraception, they are at risk of unintended pregnancy, which may result in severe consequences, as patients may be on teratogenic medications or dealing with comorbid conditions originating from cancer and cancer treatment (Contraception 2012;86:191-8).

Cancer treatments have variable impact on subsequent fertility (with the obvious exception of surgical removal of gynecologic organs resulting in sterilization). With all nonsurgical cancer treatments, the potential for subsequent fertility depends on the chemotherapeutic agents, the duration of treatment, or use of pelvic radiation. As in patients without cancer, age is inversely related to subsequent fertility. Reviews of the literature have shown that fecundability decreases by 10%-50% post chemotherapy.

Clinicians caring for these women may find it challenging to assess future fertility. Some chemotherapies induce amenorrhea, but spontaneous return of menstruation and ovarian function is possible in younger women. Traditional diagnostic tests to assess fertility, including serum FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) and/or AMH (anti-Müllerian hormone), may help in predicting future fertility. These tests can be used both in patients who desire to pursue pregnancy and in those desiring to avoid pregnancy as menstrual status may not accurately predict fertility.

Contraception counseling should begin by informing women of the most effective forms of contraception (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:184-96). It is important to consider the option of sterilization, especially when this desire predated the cancer diagnosis. In patients who are in a monogamous relationship with a male partner, vasectomy should be encouraged as a safe and effective alternative. When a woman is considering sterilization, she needs to be counseled as to the risk of regret, which is higher in younger women. Sterilization should not be performed if the consent or decision-making process is rushed by the cancer treatment.

As cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment continue to improve, more reproductive-age women will be living longer with a need for effective contraception. In the next edition of Gynecologic Oncology Consult, I will review the safety and efficacy of specific contraceptive methods in patients with cancer.

Dr. Zerden is a family planning fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research interests include postpartum contraception, methods of female sterilization, and family planning health services integration. He reported having no financial disclosures.

Approximately 740,000 women are diagnosed with cancer every year in the United States, and because of improved screening, diagnosis, and treatment, women of reproductive age have an 80%-90% 5-year survival rate. The most common cancers in reproductive age women include breast, thyroid, melanoma, colorectal, and cervical cancers. Fertility intention is a critical topic to discuss with reproductive-age cancer patients. Women with cancer often have unmet contraception needs during and following cancer treatment. Providing women with a desired, effective form of contraception that is appropriate with regard to the cancer is critical.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that pregnancy prevention is not adequately addressed in cancer patients. On the one hand, many patients believe they are no longer fertile because of a combination of the illness and the cancer treatment, and on the other hand, many providers may not be adequately trained to offer their patients the full range of contraceptive options (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;201:191.e1-4). One study demonstrated that discussions around fecundity and contraception are occurring about 50% of the time (J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. Monogr. 2005:98-100).

In response, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine has issued guidelines regarding fertility planning in cancer patients (Fertil. Steril. 2005;83:1622-8). While every patient’s circumstance is unique, recommendations are for patients to avoid pregnancy for at least 1 year beyond the completion of medical and surgical treatment of cancer. For those cancers that are hormone mediated, recommendations are to wait 2-5 years before attempting to conceive (J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2002;24:164-80; J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009; 24: S401-6).

Unless patients are educated about and offered the most effective forms of contraception, they are at risk of unintended pregnancy, which may result in severe consequences, as patients may be on teratogenic medications or dealing with comorbid conditions originating from cancer and cancer treatment (Contraception 2012;86:191-8).

Cancer treatments have variable impact on subsequent fertility (with the obvious exception of surgical removal of gynecologic organs resulting in sterilization). With all nonsurgical cancer treatments, the potential for subsequent fertility depends on the chemotherapeutic agents, the duration of treatment, or use of pelvic radiation. As in patients without cancer, age is inversely related to subsequent fertility. Reviews of the literature have shown that fecundability decreases by 10%-50% post chemotherapy.

Clinicians caring for these women may find it challenging to assess future fertility. Some chemotherapies induce amenorrhea, but spontaneous return of menstruation and ovarian function is possible in younger women. Traditional diagnostic tests to assess fertility, including serum FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) and/or AMH (anti-Müllerian hormone), may help in predicting future fertility. These tests can be used both in patients who desire to pursue pregnancy and in those desiring to avoid pregnancy as menstrual status may not accurately predict fertility.

Contraception counseling should begin by informing women of the most effective forms of contraception (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:184-96). It is important to consider the option of sterilization, especially when this desire predated the cancer diagnosis. In patients who are in a monogamous relationship with a male partner, vasectomy should be encouraged as a safe and effective alternative. When a woman is considering sterilization, she needs to be counseled as to the risk of regret, which is higher in younger women. Sterilization should not be performed if the consent or decision-making process is rushed by the cancer treatment.

As cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment continue to improve, more reproductive-age women will be living longer with a need for effective contraception. In the next edition of Gynecologic Oncology Consult, I will review the safety and efficacy of specific contraceptive methods in patients with cancer.

Dr. Zerden is a family planning fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research interests include postpartum contraception, methods of female sterilization, and family planning health services integration. He reported having no financial disclosures.

Approximately 740,000 women are diagnosed with cancer every year in the United States, and because of improved screening, diagnosis, and treatment, women of reproductive age have an 80%-90% 5-year survival rate. The most common cancers in reproductive age women include breast, thyroid, melanoma, colorectal, and cervical cancers. Fertility intention is a critical topic to discuss with reproductive-age cancer patients. Women with cancer often have unmet contraception needs during and following cancer treatment. Providing women with a desired, effective form of contraception that is appropriate with regard to the cancer is critical.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that pregnancy prevention is not adequately addressed in cancer patients. On the one hand, many patients believe they are no longer fertile because of a combination of the illness and the cancer treatment, and on the other hand, many providers may not be adequately trained to offer their patients the full range of contraceptive options (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;201:191.e1-4). One study demonstrated that discussions around fecundity and contraception are occurring about 50% of the time (J. Natl. Cancer. Inst. Monogr. 2005:98-100).

In response, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine has issued guidelines regarding fertility planning in cancer patients (Fertil. Steril. 2005;83:1622-8). While every patient’s circumstance is unique, recommendations are for patients to avoid pregnancy for at least 1 year beyond the completion of medical and surgical treatment of cancer. For those cancers that are hormone mediated, recommendations are to wait 2-5 years before attempting to conceive (J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2002;24:164-80; J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2009; 24: S401-6).

Unless patients are educated about and offered the most effective forms of contraception, they are at risk of unintended pregnancy, which may result in severe consequences, as patients may be on teratogenic medications or dealing with comorbid conditions originating from cancer and cancer treatment (Contraception 2012;86:191-8).

Cancer treatments have variable impact on subsequent fertility (with the obvious exception of surgical removal of gynecologic organs resulting in sterilization). With all nonsurgical cancer treatments, the potential for subsequent fertility depends on the chemotherapeutic agents, the duration of treatment, or use of pelvic radiation. As in patients without cancer, age is inversely related to subsequent fertility. Reviews of the literature have shown that fecundability decreases by 10%-50% post chemotherapy.

Clinicians caring for these women may find it challenging to assess future fertility. Some chemotherapies induce amenorrhea, but spontaneous return of menstruation and ovarian function is possible in younger women. Traditional diagnostic tests to assess fertility, including serum FSH (follicle stimulating hormone) and/or AMH (anti-Müllerian hormone), may help in predicting future fertility. These tests can be used both in patients who desire to pursue pregnancy and in those desiring to avoid pregnancy as menstrual status may not accurately predict fertility.

Contraception counseling should begin by informing women of the most effective forms of contraception (Obstet. Gynecol. 2011;118:184-96). It is important to consider the option of sterilization, especially when this desire predated the cancer diagnosis. In patients who are in a monogamous relationship with a male partner, vasectomy should be encouraged as a safe and effective alternative. When a woman is considering sterilization, she needs to be counseled as to the risk of regret, which is higher in younger women. Sterilization should not be performed if the consent or decision-making process is rushed by the cancer treatment.

As cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment continue to improve, more reproductive-age women will be living longer with a need for effective contraception. In the next edition of Gynecologic Oncology Consult, I will review the safety and efficacy of specific contraceptive methods in patients with cancer.

Dr. Zerden is a family planning fellow in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research interests include postpartum contraception, methods of female sterilization, and family planning health services integration. He reported having no financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Assessment tool rapidly screens lupus cognition

ROME – The Montreal Cognitive Assessment provides a quick and easy-to-use screening tool to identify patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with cognitive impairment, Dr. Zahi Touma reported in a poster at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In a consecutive series of 78 patients screened with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), the free, single-page test, which can be administered in about 10 minutes, showed a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 68%, compared with the current standard, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, said Dr. Touma, a rheumatologist at the University of Toronto.

Other easy-to-use and quick screening tools, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination, had substantially worse performance in the study. He and his associates found a sensitivity of 21% and specificity of 91% using the Mini-Mental State exam. For screening, higher sensitivity is desirable so that fewer patients with potential cognitive impairment are missed, he noted.

“Ease of use and time needed for assessment as well as appropriate psychometric properties make the MoCA the preferential screening test for cognitive impairment in patients with SLE,” Dr. Touma said in his poster.

Cognitive impairment is very common among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In this study, Dr Touma found a 47% prevalence using MoCA. Cognitive impairment, however, often goes unidentified in SLE patients, likely because of lack of awareness among rheumatologists as well as the absence of a quick and easily administered screening tool, he said in a video interview.

Dr. Touma said he hopes that the apparent efficacy of an easy-to-use screening tool like MoCA will help boost appreciation for the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in SLE patients. He suggested that clinicians screen for cognitive impairment as soon as SLE is diagnosed and that they perform follow-up screening during subsequent patient encounters with SLE patients who initially present without cognitive impairment.

Dr. Touma had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ROME – The Montreal Cognitive Assessment provides a quick and easy-to-use screening tool to identify patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with cognitive impairment, Dr. Zahi Touma reported in a poster at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In a consecutive series of 78 patients screened with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), the free, single-page test, which can be administered in about 10 minutes, showed a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 68%, compared with the current standard, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, said Dr. Touma, a rheumatologist at the University of Toronto.

Other easy-to-use and quick screening tools, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination, had substantially worse performance in the study. He and his associates found a sensitivity of 21% and specificity of 91% using the Mini-Mental State exam. For screening, higher sensitivity is desirable so that fewer patients with potential cognitive impairment are missed, he noted.

“Ease of use and time needed for assessment as well as appropriate psychometric properties make the MoCA the preferential screening test for cognitive impairment in patients with SLE,” Dr. Touma said in his poster.

Cognitive impairment is very common among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In this study, Dr Touma found a 47% prevalence using MoCA. Cognitive impairment, however, often goes unidentified in SLE patients, likely because of lack of awareness among rheumatologists as well as the absence of a quick and easily administered screening tool, he said in a video interview.

Dr. Touma said he hopes that the apparent efficacy of an easy-to-use screening tool like MoCA will help boost appreciation for the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in SLE patients. He suggested that clinicians screen for cognitive impairment as soon as SLE is diagnosed and that they perform follow-up screening during subsequent patient encounters with SLE patients who initially present without cognitive impairment.

Dr. Touma had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ROME – The Montreal Cognitive Assessment provides a quick and easy-to-use screening tool to identify patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with cognitive impairment, Dr. Zahi Touma reported in a poster at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

In a consecutive series of 78 patients screened with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), the free, single-page test, which can be administered in about 10 minutes, showed a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 68%, compared with the current standard, the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised, said Dr. Touma, a rheumatologist at the University of Toronto.

Other easy-to-use and quick screening tools, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination, had substantially worse performance in the study. He and his associates found a sensitivity of 21% and specificity of 91% using the Mini-Mental State exam. For screening, higher sensitivity is desirable so that fewer patients with potential cognitive impairment are missed, he noted.

“Ease of use and time needed for assessment as well as appropriate psychometric properties make the MoCA the preferential screening test for cognitive impairment in patients with SLE,” Dr. Touma said in his poster.

Cognitive impairment is very common among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In this study, Dr Touma found a 47% prevalence using MoCA. Cognitive impairment, however, often goes unidentified in SLE patients, likely because of lack of awareness among rheumatologists as well as the absence of a quick and easily administered screening tool, he said in a video interview.

Dr. Touma said he hopes that the apparent efficacy of an easy-to-use screening tool like MoCA will help boost appreciation for the high prevalence of cognitive impairment in SLE patients. He suggested that clinicians screen for cognitive impairment as soon as SLE is diagnosed and that they perform follow-up screening during subsequent patient encounters with SLE patients who initially present without cognitive impairment.

Dr. Touma had no disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE EULAR 2015 CONGRESS

Product News: 06 2015

Intensive Eye Treatment

Niadyne, Incorporated, introduces the NIA24 Intensive Eye Treatment, a dual-phase, predosed, multiaction eye mask to reduce the look of fine lines, wrinkles, and dark circles. The treatment begins with the aesthetician combining the predosed treatment base with the activating powder just prior to use. Once combined, the activated components are applied around the eye area. The Intensive Eye Treatment contains Pro-Niacin to help stimulate skin barrier repair, improve cell turnover, and energize skin. Haloxyl tripeptide complex decreases the red and blue color of dark circles under the eyes and acts as an anti-inflammatory agent. Lumispheres skin brightener diminishes the appearance of fine lines. Other ingredients firm and tighten skin, while reducing undereye bags and puffiness. The Intensive Eye Treatment is a professional treatment that is available exclusively through physicians. For more information, visit www.nia24.com/professional-treatments/.

Kybella Injection

Kythera Biopharmaceuticals announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Kybella (deoxycholic acid), also known as ATX-101, a nonsurgical treatment indicated for improvement in the appearance of moderate to severe convexity or fullness associated with submental fat in adults. Kybella is administered by injections into the fat under the chin, which causes destruction of fat cells. Once destroyed, those cells cannot store or accumulate fat. Each in-office treatment session is typically 15 to 20 minutes, and up to 6 treatments may be administered. Many patients experience visible results in 2 to 4 treatments. Once the aesthetic response is achieved, re-treatment is not expected. Kybella physician training programs will be initiated in late summer. For more information, visit www.mykybella.com.

Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte Sunscreen Lotion

Obagi Medical Products, Inc, a division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, introduces the Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte SPF 50 Sunscreen Lotion. It combines UVB absorption and UVA protection with a completely sheer application. It contains 10.5% zinc oxide and 7.5% octinoxate. The Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte Sunscreen Lotion is ideal for use on all skin types and is physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.obagi.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Intensive Eye Treatment

Niadyne, Incorporated, introduces the NIA24 Intensive Eye Treatment, a dual-phase, predosed, multiaction eye mask to reduce the look of fine lines, wrinkles, and dark circles. The treatment begins with the aesthetician combining the predosed treatment base with the activating powder just prior to use. Once combined, the activated components are applied around the eye area. The Intensive Eye Treatment contains Pro-Niacin to help stimulate skin barrier repair, improve cell turnover, and energize skin. Haloxyl tripeptide complex decreases the red and blue color of dark circles under the eyes and acts as an anti-inflammatory agent. Lumispheres skin brightener diminishes the appearance of fine lines. Other ingredients firm and tighten skin, while reducing undereye bags and puffiness. The Intensive Eye Treatment is a professional treatment that is available exclusively through physicians. For more information, visit www.nia24.com/professional-treatments/.

Kybella Injection

Kythera Biopharmaceuticals announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Kybella (deoxycholic acid), also known as ATX-101, a nonsurgical treatment indicated for improvement in the appearance of moderate to severe convexity or fullness associated with submental fat in adults. Kybella is administered by injections into the fat under the chin, which causes destruction of fat cells. Once destroyed, those cells cannot store or accumulate fat. Each in-office treatment session is typically 15 to 20 minutes, and up to 6 treatments may be administered. Many patients experience visible results in 2 to 4 treatments. Once the aesthetic response is achieved, re-treatment is not expected. Kybella physician training programs will be initiated in late summer. For more information, visit www.mykybella.com.

Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte Sunscreen Lotion

Obagi Medical Products, Inc, a division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, introduces the Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte SPF 50 Sunscreen Lotion. It combines UVB absorption and UVA protection with a completely sheer application. It contains 10.5% zinc oxide and 7.5% octinoxate. The Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte Sunscreen Lotion is ideal for use on all skin types and is physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.obagi.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Intensive Eye Treatment

Niadyne, Incorporated, introduces the NIA24 Intensive Eye Treatment, a dual-phase, predosed, multiaction eye mask to reduce the look of fine lines, wrinkles, and dark circles. The treatment begins with the aesthetician combining the predosed treatment base with the activating powder just prior to use. Once combined, the activated components are applied around the eye area. The Intensive Eye Treatment contains Pro-Niacin to help stimulate skin barrier repair, improve cell turnover, and energize skin. Haloxyl tripeptide complex decreases the red and blue color of dark circles under the eyes and acts as an anti-inflammatory agent. Lumispheres skin brightener diminishes the appearance of fine lines. Other ingredients firm and tighten skin, while reducing undereye bags and puffiness. The Intensive Eye Treatment is a professional treatment that is available exclusively through physicians. For more information, visit www.nia24.com/professional-treatments/.

Kybella Injection

Kythera Biopharmaceuticals announces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Kybella (deoxycholic acid), also known as ATX-101, a nonsurgical treatment indicated for improvement in the appearance of moderate to severe convexity or fullness associated with submental fat in adults. Kybella is administered by injections into the fat under the chin, which causes destruction of fat cells. Once destroyed, those cells cannot store or accumulate fat. Each in-office treatment session is typically 15 to 20 minutes, and up to 6 treatments may be administered. Many patients experience visible results in 2 to 4 treatments. Once the aesthetic response is achieved, re-treatment is not expected. Kybella physician training programs will be initiated in late summer. For more information, visit www.mykybella.com.

Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte Sunscreen Lotion

Obagi Medical Products, Inc, a division of Valeant Pharmaceuticals North America LLC, introduces the Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte SPF 50 Sunscreen Lotion. It combines UVB absorption and UVA protection with a completely sheer application. It contains 10.5% zinc oxide and 7.5% octinoxate. The Sun Shield Broad Spectrum Matte Sunscreen Lotion is ideal for use on all skin types and is physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.obagi.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

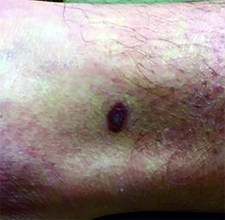

Make the Diagnosis - June 2015

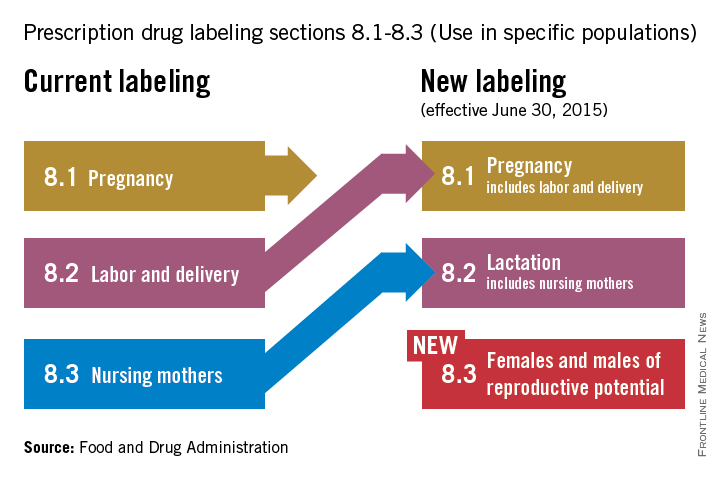

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Kaposi's sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm with four principal clinical variants: HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, classic Kaposi's sarcoma, African endemic Kaposi's sarcoma, and immunosuppression-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. The etiologic agent in all clinical variants is human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma is primarily seen in men who have sex with men.

The four variants of Kaposi's sarcoma can have different clinical presentations. In HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma, patients may present with a single lesion or with symmetric widespread lesions. Clinically, the lesions can range from faint erythematous macules, to small violaceous papules, to large plaques or ulcerated nodules. The lesions are generally asymptomatic.

Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. Common body locations include the face (especially the nose), hard palate, trunk, penis, lower legs, and soles. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics. Histologically, atypical, angular vessels with an associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells appear in the upper dermis in macular lesions. Nodules and tumors reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions stain positive for human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8).

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma has greatly decreased. HAART is the most effective treatment method, and should be the initial therapy in most patients with mild to moderate disease.

However, some patients with HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma require further treatment - those who have well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads. Other treatments include local destruction (cryotherapy), topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin, or paclitaxel.

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Kaposi's sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm with four principal clinical variants: HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, classic Kaposi's sarcoma, African endemic Kaposi's sarcoma, and immunosuppression-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. The etiologic agent in all clinical variants is human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma is primarily seen in men who have sex with men.

The four variants of Kaposi's sarcoma can have different clinical presentations. In HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma, patients may present with a single lesion or with symmetric widespread lesions. Clinically, the lesions can range from faint erythematous macules, to small violaceous papules, to large plaques or ulcerated nodules. The lesions are generally asymptomatic.

Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. Common body locations include the face (especially the nose), hard palate, trunk, penis, lower legs, and soles. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics. Histologically, atypical, angular vessels with an associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells appear in the upper dermis in macular lesions. Nodules and tumors reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions stain positive for human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8).

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma has greatly decreased. HAART is the most effective treatment method, and should be the initial therapy in most patients with mild to moderate disease.

However, some patients with HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma require further treatment - those who have well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads. Other treatments include local destruction (cryotherapy), topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin, or paclitaxel.

Diagnosis: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Kaposi's sarcoma is a vascular neoplasm with four principal clinical variants: HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, classic Kaposi's sarcoma, African endemic Kaposi's sarcoma, and immunosuppression-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. The etiologic agent in all clinical variants is human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). HIV/AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma is primarily seen in men who have sex with men.

The four variants of Kaposi's sarcoma can have different clinical presentations. In HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma, patients may present with a single lesion or with symmetric widespread lesions. Clinically, the lesions can range from faint erythematous macules, to small violaceous papules, to large plaques or ulcerated nodules. The lesions are generally asymptomatic.

Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. Common body locations include the face (especially the nose), hard palate, trunk, penis, lower legs, and soles. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics. Histologically, atypical, angular vessels with an associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells appear in the upper dermis in macular lesions. Nodules and tumors reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions stain positive for human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8).

Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma has greatly decreased. HAART is the most effective treatment method, and should be the initial therapy in most patients with mild to moderate disease.

However, some patients with HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma require further treatment - those who have well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads. Other treatments include local destruction (cryotherapy), topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin, or paclitaxel.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Ann Mazor Reed, Larkin Community Hospital, South Miami; and Dr. Donna Bilu Martin, Premier Dermatology, MD. Dr. Bilu Martin is in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD in Aventura, Fla. To submit your case for possible publication, send an e-mail to [email protected]. A 39-year-old white male presented with a 2-month history involving asymptomatic violaceous plaques on his leg and posterior neck. He had no significant past medical history. He had no oral or mucosal involvement, no lymphadenopathy, and denied any systemic symptoms.

Steroids for sciatica

The other day, I received an electronic message that my patient presented to the emergency department following his attempt at lifting a relatively immovable object. The only thing apparently moved by this activity was his intervertebral disk – outward from its usual place and onto a nerve. He was quickly diagnosed with acute sciatica and treated with a healthy dose of steroids.

I enjoyed the subsequent soliloquy of the brilliance and outstanding clinical skill of our emergency department clinicians (which is true, by the way) when I saw him for follow-up. He was markedly improved.

In a moment of introspection, I questioned why we do not tend to use this strategy more in my practice, especially because it worked so well for my patient.

Perhaps it is because we are so used to dealing with medication side effects and the downstream consequences of insulin resistance in primary care that steroids make us squeamish. Perhaps it is also because we tend to see patients later in the course of their disease and think that it is too late for steroids to be beneficial. Maybe we are uncertain of their benefits.

So, how well do they work?

Dr. Harley Goldberg and colleagues recently published data from a randomized clinical trial exploring the efficacy of oral steroids for the treatment of acute sciatica (JAMA 2015;313:1915-23). A total of 269 adults with radicular pain for 3 months or less, an Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) of at least 30, and a herniated disk confirmed on MRI were randomized to prednisone or placebo. The prednisone dose was 60 mg for 5 days, then 40 mg for 5 days, and finally 20 mg for 5 days.

The prednisone group demonstrated significant reduction in the ODI at 3 weeks and 12 months, compared with placebo. No differences in pain or in rates of surgery were observed.

Adverse events were more common with prednisone, the most common being insomnia, increased appetite, and nervousness. No serious adverse events occurred related to treatment, and no differences were observed at 1 year.

The authors point out that the observation of a reduction in disability but no reduction in pain may be related to the fact that as patients improve functionally, they increase activity and experience more pain. Although analyses did not demonstrate a relationship between time until starting the steroids and identified effects of prednisone, clinical sense may press us to want to start them earlier in the course of disease.

Steroids might be a reasonable option in this setting, and combining them with other modalities (e.g., gabapentin) might further improve patients’ functional status and pain. As always, engaging patients in the shared decision making may help manage expectations.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no disclosures about this article.

The other day, I received an electronic message that my patient presented to the emergency department following his attempt at lifting a relatively immovable object. The only thing apparently moved by this activity was his intervertebral disk – outward from its usual place and onto a nerve. He was quickly diagnosed with acute sciatica and treated with a healthy dose of steroids.

I enjoyed the subsequent soliloquy of the brilliance and outstanding clinical skill of our emergency department clinicians (which is true, by the way) when I saw him for follow-up. He was markedly improved.

In a moment of introspection, I questioned why we do not tend to use this strategy more in my practice, especially because it worked so well for my patient.

Perhaps it is because we are so used to dealing with medication side effects and the downstream consequences of insulin resistance in primary care that steroids make us squeamish. Perhaps it is also because we tend to see patients later in the course of their disease and think that it is too late for steroids to be beneficial. Maybe we are uncertain of their benefits.

So, how well do they work?

Dr. Harley Goldberg and colleagues recently published data from a randomized clinical trial exploring the efficacy of oral steroids for the treatment of acute sciatica (JAMA 2015;313:1915-23). A total of 269 adults with radicular pain for 3 months or less, an Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) of at least 30, and a herniated disk confirmed on MRI were randomized to prednisone or placebo. The prednisone dose was 60 mg for 5 days, then 40 mg for 5 days, and finally 20 mg for 5 days.

The prednisone group demonstrated significant reduction in the ODI at 3 weeks and 12 months, compared with placebo. No differences in pain or in rates of surgery were observed.

Adverse events were more common with prednisone, the most common being insomnia, increased appetite, and nervousness. No serious adverse events occurred related to treatment, and no differences were observed at 1 year.

The authors point out that the observation of a reduction in disability but no reduction in pain may be related to the fact that as patients improve functionally, they increase activity and experience more pain. Although analyses did not demonstrate a relationship between time until starting the steroids and identified effects of prednisone, clinical sense may press us to want to start them earlier in the course of disease.

Steroids might be a reasonable option in this setting, and combining them with other modalities (e.g., gabapentin) might further improve patients’ functional status and pain. As always, engaging patients in the shared decision making may help manage expectations.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no disclosures about this article.

The other day, I received an electronic message that my patient presented to the emergency department following his attempt at lifting a relatively immovable object. The only thing apparently moved by this activity was his intervertebral disk – outward from its usual place and onto a nerve. He was quickly diagnosed with acute sciatica and treated with a healthy dose of steroids.

I enjoyed the subsequent soliloquy of the brilliance and outstanding clinical skill of our emergency department clinicians (which is true, by the way) when I saw him for follow-up. He was markedly improved.

In a moment of introspection, I questioned why we do not tend to use this strategy more in my practice, especially because it worked so well for my patient.

Perhaps it is because we are so used to dealing with medication side effects and the downstream consequences of insulin resistance in primary care that steroids make us squeamish. Perhaps it is also because we tend to see patients later in the course of their disease and think that it is too late for steroids to be beneficial. Maybe we are uncertain of their benefits.

So, how well do they work?

Dr. Harley Goldberg and colleagues recently published data from a randomized clinical trial exploring the efficacy of oral steroids for the treatment of acute sciatica (JAMA 2015;313:1915-23). A total of 269 adults with radicular pain for 3 months or less, an Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) of at least 30, and a herniated disk confirmed on MRI were randomized to prednisone or placebo. The prednisone dose was 60 mg for 5 days, then 40 mg for 5 days, and finally 20 mg for 5 days.

The prednisone group demonstrated significant reduction in the ODI at 3 weeks and 12 months, compared with placebo. No differences in pain or in rates of surgery were observed.

Adverse events were more common with prednisone, the most common being insomnia, increased appetite, and nervousness. No serious adverse events occurred related to treatment, and no differences were observed at 1 year.

The authors point out that the observation of a reduction in disability but no reduction in pain may be related to the fact that as patients improve functionally, they increase activity and experience more pain. Although analyses did not demonstrate a relationship between time until starting the steroids and identified effects of prednisone, clinical sense may press us to want to start them earlier in the course of disease.

Steroids might be a reasonable option in this setting, and combining them with other modalities (e.g., gabapentin) might further improve patients’ functional status and pain. As always, engaging patients in the shared decision making may help manage expectations.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no disclosures about this article.

Molecule accelerates recovery after BMT

Photo by Chad McNeeley

A small molecule may be able to accelerate cell recovery in bone marrow transplant (BMT) recipients and patients with liver or colon disease, researchers believe.

The molecule, SW033291, inhibits 15-PGDH, a prostaglandin-degrading enzyme that regulates tissue regeneration in multiple organs.

SW033291 accelerated hematopoietic recovery in mice that received BMTs and promoted tissue regeneration in mice with liver or colon injuries.

“We propose that SW033291 will be useful in accelerating recovery of bone marrow cells following a bone marrow transplant and may also be a treatment for colitis,” said James Willson, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

He and his colleagues described their work with SW033291 in Science.

To examine the effects of inhibiting 15-PGDH on the bone marrow, the researchers conducted experiments with 15-PGDH-knockout mice and SW033291-treated mice, comparing them to control mice.

The team saw a 43% increase in neutrophil counts and a 39% increase in bone marrow Sca-1+ C-kit+ Lin– (SKL) cells in 15-PGDH knockout compared to wild-type mice. There were no significant differences in counts of other peripheral blood cells, bone marrow cellularity, or counts of bone marrow Sca-1+ C-kit+ Lin– CD48– CD150+ (SLAM) cells.

SW033291-treated mice had double the peripheral neutrophil counts of controls, a 65% increase in marrow SKL cells, and a 71% increase in marrow SLAM cells.

Results of additional experiments indicated that SW033291 works by increasing PGE2 levels in the bone marrow, and PGE2 functions through the EP2 and EP4 receptors to induce expression of CXCL12 and SCF.

The researchers also tested whether SW033291 could increase the bone marrow’s ability to attract and support new hematopoietic stem cells after BMT in mice. They found that BMT recipients treated with SW033291 had a 2- to 3-fold increase in the number of donor cells that homed to their bone marrow, compared to vehicle-treated BMT recipients.

The researchers said this SW033291-induced homing of transplanted bone marrow cells was driven, at least in part, by the induction of CXCL12 expression in CD45– nonmyeloid cells that were already resident in the bone marrow of recipient mice.

These results suggest 15-PGDH inhibition causes an increase in bone marrow PGE2, which induces the expression of bone marrow CXCL12 and SCF, and these cytokines alter the bone marrow microenvironment to better support the homing of transplanted cells.

The researchers also evaluated whether 15-PGDH inhibition promotes hematopoietic recovery after BMT. They studied lethally irradiated mice that received 200,000 strain-matched donor bone marrow cells, which were insufficient to reconstitute hematopoiesis in the mice.

When the mice were treated with SW033291, they survived for more than 30 days. All control mice, on the other hand, died between days 6 and 14.

For the last of their BMT experiments, the researchers examined the effect of SW033291 on mice transplanted with 500,000 bone marrow cells.

All SW033291-treated mice and 63% of control mice survived for 30 days, which allowed the team to compare hematopoietic recovery between the two groups. They found that SW033291 significantly accelerated the recovery of neutrophils, platelets, and red blood cells.

Experiments in mice with liver or colon injuries suggested that SW033291 can aid recovery in these models as well. ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

A small molecule may be able to accelerate cell recovery in bone marrow transplant (BMT) recipients and patients with liver or colon disease, researchers believe.

The molecule, SW033291, inhibits 15-PGDH, a prostaglandin-degrading enzyme that regulates tissue regeneration in multiple organs.

SW033291 accelerated hematopoietic recovery in mice that received BMTs and promoted tissue regeneration in mice with liver or colon injuries.

“We propose that SW033291 will be useful in accelerating recovery of bone marrow cells following a bone marrow transplant and may also be a treatment for colitis,” said James Willson, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

He and his colleagues described their work with SW033291 in Science.

To examine the effects of inhibiting 15-PGDH on the bone marrow, the researchers conducted experiments with 15-PGDH-knockout mice and SW033291-treated mice, comparing them to control mice.

The team saw a 43% increase in neutrophil counts and a 39% increase in bone marrow Sca-1+ C-kit+ Lin– (SKL) cells in 15-PGDH knockout compared to wild-type mice. There were no significant differences in counts of other peripheral blood cells, bone marrow cellularity, or counts of bone marrow Sca-1+ C-kit+ Lin– CD48– CD150+ (SLAM) cells.

SW033291-treated mice had double the peripheral neutrophil counts of controls, a 65% increase in marrow SKL cells, and a 71% increase in marrow SLAM cells.

Results of additional experiments indicated that SW033291 works by increasing PGE2 levels in the bone marrow, and PGE2 functions through the EP2 and EP4 receptors to induce expression of CXCL12 and SCF.

The researchers also tested whether SW033291 could increase the bone marrow’s ability to attract and support new hematopoietic stem cells after BMT in mice. They found that BMT recipients treated with SW033291 had a 2- to 3-fold increase in the number of donor cells that homed to their bone marrow, compared to vehicle-treated BMT recipients.

The researchers said this SW033291-induced homing of transplanted bone marrow cells was driven, at least in part, by the induction of CXCL12 expression in CD45– nonmyeloid cells that were already resident in the bone marrow of recipient mice.

These results suggest 15-PGDH inhibition causes an increase in bone marrow PGE2, which induces the expression of bone marrow CXCL12 and SCF, and these cytokines alter the bone marrow microenvironment to better support the homing of transplanted cells.

The researchers also evaluated whether 15-PGDH inhibition promotes hematopoietic recovery after BMT. They studied lethally irradiated mice that received 200,000 strain-matched donor bone marrow cells, which were insufficient to reconstitute hematopoiesis in the mice.

When the mice were treated with SW033291, they survived for more than 30 days. All control mice, on the other hand, died between days 6 and 14.

For the last of their BMT experiments, the researchers examined the effect of SW033291 on mice transplanted with 500,000 bone marrow cells.

All SW033291-treated mice and 63% of control mice survived for 30 days, which allowed the team to compare hematopoietic recovery between the two groups. They found that SW033291 significantly accelerated the recovery of neutrophils, platelets, and red blood cells.

Experiments in mice with liver or colon injuries suggested that SW033291 can aid recovery in these models as well. ![]()

Photo by Chad McNeeley

A small molecule may be able to accelerate cell recovery in bone marrow transplant (BMT) recipients and patients with liver or colon disease, researchers believe.

The molecule, SW033291, inhibits 15-PGDH, a prostaglandin-degrading enzyme that regulates tissue regeneration in multiple organs.

SW033291 accelerated hematopoietic recovery in mice that received BMTs and promoted tissue regeneration in mice with liver or colon injuries.

“We propose that SW033291 will be useful in accelerating recovery of bone marrow cells following a bone marrow transplant and may also be a treatment for colitis,” said James Willson, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

He and his colleagues described their work with SW033291 in Science.

To examine the effects of inhibiting 15-PGDH on the bone marrow, the researchers conducted experiments with 15-PGDH-knockout mice and SW033291-treated mice, comparing them to control mice.

The team saw a 43% increase in neutrophil counts and a 39% increase in bone marrow Sca-1+ C-kit+ Lin– (SKL) cells in 15-PGDH knockout compared to wild-type mice. There were no significant differences in counts of other peripheral blood cells, bone marrow cellularity, or counts of bone marrow Sca-1+ C-kit+ Lin– CD48– CD150+ (SLAM) cells.

SW033291-treated mice had double the peripheral neutrophil counts of controls, a 65% increase in marrow SKL cells, and a 71% increase in marrow SLAM cells.

Results of additional experiments indicated that SW033291 works by increasing PGE2 levels in the bone marrow, and PGE2 functions through the EP2 and EP4 receptors to induce expression of CXCL12 and SCF.

The researchers also tested whether SW033291 could increase the bone marrow’s ability to attract and support new hematopoietic stem cells after BMT in mice. They found that BMT recipients treated with SW033291 had a 2- to 3-fold increase in the number of donor cells that homed to their bone marrow, compared to vehicle-treated BMT recipients.

The researchers said this SW033291-induced homing of transplanted bone marrow cells was driven, at least in part, by the induction of CXCL12 expression in CD45– nonmyeloid cells that were already resident in the bone marrow of recipient mice.

These results suggest 15-PGDH inhibition causes an increase in bone marrow PGE2, which induces the expression of bone marrow CXCL12 and SCF, and these cytokines alter the bone marrow microenvironment to better support the homing of transplanted cells.

The researchers also evaluated whether 15-PGDH inhibition promotes hematopoietic recovery after BMT. They studied lethally irradiated mice that received 200,000 strain-matched donor bone marrow cells, which were insufficient to reconstitute hematopoiesis in the mice.

When the mice were treated with SW033291, they survived for more than 30 days. All control mice, on the other hand, died between days 6 and 14.

For the last of their BMT experiments, the researchers examined the effect of SW033291 on mice transplanted with 500,000 bone marrow cells.

All SW033291-treated mice and 63% of control mice survived for 30 days, which allowed the team to compare hematopoietic recovery between the two groups. They found that SW033291 significantly accelerated the recovery of neutrophils, platelets, and red blood cells.

Experiments in mice with liver or colon injuries suggested that SW033291 can aid recovery in these models as well. ![]()

Modern housing may reduce malaria risk

Photo by James Gathany

Living in a “modern” house may reduce a person’s risk of contracting malaria, according to research published in Malaria Journal.

As insecticide and drug resistance are on the rise, researchers wanted to determine how making changes to housing might aid the fight against malaria.

So they reviewed 90 studies conducted in Africa, Asia, and South America, comparing the incidence of malaria among people who live in “traditional” and “modern” houses.

The traditional houses consisted of mud, stone, bamboo, or wood walls; thatched, mud, or wood roofs; and earth or wood floors. The modern houses had closed eaves, ceilings, screened doors, and windows.

The researchers found that residents of modern homes were 47% less likely to be infected with malaria than those living in traditional houses. And residents of modern homes were 45% to 65% less likely to have clinical malaria (fever with infection).

“Housing improvements were traditionally an important pillar of public health, but they remain underexploited in malaria control,” said study author Lucy Tusting, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“Good housing can block mosquitoes from entering homes and prevent them from transmitting malaria to the people who live there. Our study suggests housing could be an important tool in tackling malaria. This is a welcome finding at a time when we are facing increasing resistance to our most effective insecticides and drugs.”

“We now need to pinpoint which housing features can reduce mosquito entry in different settings, to incorporate these into local housing designs, and to assess the impact on malaria in large-scale field trials.”

The researchers noted that the effectiveness of improving housing will vary depending on the location. While many mosquitoes enter homes to bite humans at night, outdoor malaria transmission is more common in some places. So interventions centered on the home will have less of an impact in these areas.

The researchers also conceded that the studies eligible for inclusion in this review were of low quality. However, they said the consistency of the findings indicate that housing is an important risk factor for malaria. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Living in a “modern” house may reduce a person’s risk of contracting malaria, according to research published in Malaria Journal.

As insecticide and drug resistance are on the rise, researchers wanted to determine how making changes to housing might aid the fight against malaria.

So they reviewed 90 studies conducted in Africa, Asia, and South America, comparing the incidence of malaria among people who live in “traditional” and “modern” houses.

The traditional houses consisted of mud, stone, bamboo, or wood walls; thatched, mud, or wood roofs; and earth or wood floors. The modern houses had closed eaves, ceilings, screened doors, and windows.

The researchers found that residents of modern homes were 47% less likely to be infected with malaria than those living in traditional houses. And residents of modern homes were 45% to 65% less likely to have clinical malaria (fever with infection).

“Housing improvements were traditionally an important pillar of public health, but they remain underexploited in malaria control,” said study author Lucy Tusting, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“Good housing can block mosquitoes from entering homes and prevent them from transmitting malaria to the people who live there. Our study suggests housing could be an important tool in tackling malaria. This is a welcome finding at a time when we are facing increasing resistance to our most effective insecticides and drugs.”

“We now need to pinpoint which housing features can reduce mosquito entry in different settings, to incorporate these into local housing designs, and to assess the impact on malaria in large-scale field trials.”

The researchers noted that the effectiveness of improving housing will vary depending on the location. While many mosquitoes enter homes to bite humans at night, outdoor malaria transmission is more common in some places. So interventions centered on the home will have less of an impact in these areas.

The researchers also conceded that the studies eligible for inclusion in this review were of low quality. However, they said the consistency of the findings indicate that housing is an important risk factor for malaria. ![]()

Photo by James Gathany

Living in a “modern” house may reduce a person’s risk of contracting malaria, according to research published in Malaria Journal.

As insecticide and drug resistance are on the rise, researchers wanted to determine how making changes to housing might aid the fight against malaria.

So they reviewed 90 studies conducted in Africa, Asia, and South America, comparing the incidence of malaria among people who live in “traditional” and “modern” houses.