User login

Anemia tied to cognitive impairment

A population-based study conducted in Germany has suggested a link between anemia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Researchers found that subjects with anemia, defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dL in men and <12 g/dL in women, performed worse on cognitive tests than their nonanemic peers.

And MCI occurred almost twice as often in subjects with anemia than in subjects with normal hemoglobin levels.

This study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

About MCI

MCI represents an intermediate and possibly modifiable stage between normal cognitive aging and dementia. Although individuals with MCI have an increased risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, they can also remain stable for many years or even revert to a cognitively normal state over time. This modifiable characteristic makes the concept of MCI a promising target in the prevention of dementia.

The following 4 criteria are used to diagnose MCI. First, subjects must report a decline in cognitive performance over the past 2 years. Second, they must show a cognitive impairment in objective cognitive tasks that is greater than one would expect taking their age and education into consideration.

Third, the impairment must not be as pronounced as in demented individuals since people with MCI can perform normal daily living activities or are only slightly impaired in carrying out complex instrumental functions. Fourth, the cognitive impairment has to be insufficient to fulfil criteria for dementia.

The concept of MCI distinguishes between amnestic MCI (aMCI) and non-amnestic MCI (naMCI). In the former, impairment in the memory domain is evident, most likely reflecting Alzheimer’s disease pathology. In the latter, impairment in non-memory domains is present, mainly reflecting vascular pathology but also frontotemporal dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies.

Study details

The Heinz Nixdorf Recall study is an observational, population-based, prospective study in which researchers examined 4814 subjects between 2000 and 2003. Subjects were 50 to 80 years of age and lived in the metropolitan Ruhr Area. Both genders were equally represented.

After 5 years, the researchers conducted a second examination with 92% of the subjects taking part. The publication includes cross-sectional results of the second examination.

First, 163 subjects with anemia and 3870 without anemia were included to compare their performance in all cognitive subtests.

The subjects took verbal memory tests, which were used to gauge immediate recall and delayed recall. They were also tested on executive functioning, which included problem-solving/speed of processing, verbal fluency, visual spatial organization, and the clock drawing test.

In the initial analysis, anemic subjects showed more pronounced cardiovascular risk profiles and lower cognitive performance in all administered cognitive subtests. After adjusting for age, anemic subjects showed a significantly lower performance in the immediate recall task (P=0.009) and the verbal fluency task (P=0.004).

Next, the researchers compared 579 subjects diagnosed with MCI—299 with aMCI and 280 with naMCI—to 1438 cognitively normal subjects to determine the association between anemia at follow-up and MCI.

The team found that MCI occurred more often in anemic than non-anemic subjects. The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) was 2.59 (P<0.001). The OR after adjustment for age, gender, and years of education was 2.15 (P=0.002).

In a third analysis, the researchers adjusted for the aforementioned variables as well as body mass index, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, glomerular filtration rate, cholesterol, serum iron, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of coronary heart disease, history of stroke, history of cancer, APOE4, smoking, severe depressive symptoms, and use of antidepressants. The OR after adjustment for these factors was 1.92 (P=0.04).

Similar results were found for aMCI and naMCI. The researchers said this suggests that having a low hemoglobin level may contribute to cognitive impairment via different pathways.

The team believes that, overall, their study results indicate that anemia is associated with an increased risk of MCI independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. They said the association between anemia and MCI has important clinical relevance because—depending on etiology—anemia can be treated effectively, and this might provide means to prevent or delay cognitive decline. ![]()

A population-based study conducted in Germany has suggested a link between anemia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Researchers found that subjects with anemia, defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dL in men and <12 g/dL in women, performed worse on cognitive tests than their nonanemic peers.

And MCI occurred almost twice as often in subjects with anemia than in subjects with normal hemoglobin levels.

This study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

About MCI

MCI represents an intermediate and possibly modifiable stage between normal cognitive aging and dementia. Although individuals with MCI have an increased risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, they can also remain stable for many years or even revert to a cognitively normal state over time. This modifiable characteristic makes the concept of MCI a promising target in the prevention of dementia.

The following 4 criteria are used to diagnose MCI. First, subjects must report a decline in cognitive performance over the past 2 years. Second, they must show a cognitive impairment in objective cognitive tasks that is greater than one would expect taking their age and education into consideration.

Third, the impairment must not be as pronounced as in demented individuals since people with MCI can perform normal daily living activities or are only slightly impaired in carrying out complex instrumental functions. Fourth, the cognitive impairment has to be insufficient to fulfil criteria for dementia.

The concept of MCI distinguishes between amnestic MCI (aMCI) and non-amnestic MCI (naMCI). In the former, impairment in the memory domain is evident, most likely reflecting Alzheimer’s disease pathology. In the latter, impairment in non-memory domains is present, mainly reflecting vascular pathology but also frontotemporal dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies.

Study details

The Heinz Nixdorf Recall study is an observational, population-based, prospective study in which researchers examined 4814 subjects between 2000 and 2003. Subjects were 50 to 80 years of age and lived in the metropolitan Ruhr Area. Both genders were equally represented.

After 5 years, the researchers conducted a second examination with 92% of the subjects taking part. The publication includes cross-sectional results of the second examination.

First, 163 subjects with anemia and 3870 without anemia were included to compare their performance in all cognitive subtests.

The subjects took verbal memory tests, which were used to gauge immediate recall and delayed recall. They were also tested on executive functioning, which included problem-solving/speed of processing, verbal fluency, visual spatial organization, and the clock drawing test.

In the initial analysis, anemic subjects showed more pronounced cardiovascular risk profiles and lower cognitive performance in all administered cognitive subtests. After adjusting for age, anemic subjects showed a significantly lower performance in the immediate recall task (P=0.009) and the verbal fluency task (P=0.004).

Next, the researchers compared 579 subjects diagnosed with MCI—299 with aMCI and 280 with naMCI—to 1438 cognitively normal subjects to determine the association between anemia at follow-up and MCI.

The team found that MCI occurred more often in anemic than non-anemic subjects. The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) was 2.59 (P<0.001). The OR after adjustment for age, gender, and years of education was 2.15 (P=0.002).

In a third analysis, the researchers adjusted for the aforementioned variables as well as body mass index, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, glomerular filtration rate, cholesterol, serum iron, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of coronary heart disease, history of stroke, history of cancer, APOE4, smoking, severe depressive symptoms, and use of antidepressants. The OR after adjustment for these factors was 1.92 (P=0.04).

Similar results were found for aMCI and naMCI. The researchers said this suggests that having a low hemoglobin level may contribute to cognitive impairment via different pathways.

The team believes that, overall, their study results indicate that anemia is associated with an increased risk of MCI independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. They said the association between anemia and MCI has important clinical relevance because—depending on etiology—anemia can be treated effectively, and this might provide means to prevent or delay cognitive decline. ![]()

A population-based study conducted in Germany has suggested a link between anemia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Researchers found that subjects with anemia, defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dL in men and <12 g/dL in women, performed worse on cognitive tests than their nonanemic peers.

And MCI occurred almost twice as often in subjects with anemia than in subjects with normal hemoglobin levels.

This study was published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

About MCI

MCI represents an intermediate and possibly modifiable stage between normal cognitive aging and dementia. Although individuals with MCI have an increased risk of developing dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, they can also remain stable for many years or even revert to a cognitively normal state over time. This modifiable characteristic makes the concept of MCI a promising target in the prevention of dementia.

The following 4 criteria are used to diagnose MCI. First, subjects must report a decline in cognitive performance over the past 2 years. Second, they must show a cognitive impairment in objective cognitive tasks that is greater than one would expect taking their age and education into consideration.

Third, the impairment must not be as pronounced as in demented individuals since people with MCI can perform normal daily living activities or are only slightly impaired in carrying out complex instrumental functions. Fourth, the cognitive impairment has to be insufficient to fulfil criteria for dementia.

The concept of MCI distinguishes between amnestic MCI (aMCI) and non-amnestic MCI (naMCI). In the former, impairment in the memory domain is evident, most likely reflecting Alzheimer’s disease pathology. In the latter, impairment in non-memory domains is present, mainly reflecting vascular pathology but also frontotemporal dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies.

Study details

The Heinz Nixdorf Recall study is an observational, population-based, prospective study in which researchers examined 4814 subjects between 2000 and 2003. Subjects were 50 to 80 years of age and lived in the metropolitan Ruhr Area. Both genders were equally represented.

After 5 years, the researchers conducted a second examination with 92% of the subjects taking part. The publication includes cross-sectional results of the second examination.

First, 163 subjects with anemia and 3870 without anemia were included to compare their performance in all cognitive subtests.

The subjects took verbal memory tests, which were used to gauge immediate recall and delayed recall. They were also tested on executive functioning, which included problem-solving/speed of processing, verbal fluency, visual spatial organization, and the clock drawing test.

In the initial analysis, anemic subjects showed more pronounced cardiovascular risk profiles and lower cognitive performance in all administered cognitive subtests. After adjusting for age, anemic subjects showed a significantly lower performance in the immediate recall task (P=0.009) and the verbal fluency task (P=0.004).

Next, the researchers compared 579 subjects diagnosed with MCI—299 with aMCI and 280 with naMCI—to 1438 cognitively normal subjects to determine the association between anemia at follow-up and MCI.

The team found that MCI occurred more often in anemic than non-anemic subjects. The unadjusted odds ratio (OR) was 2.59 (P<0.001). The OR after adjustment for age, gender, and years of education was 2.15 (P=0.002).

In a third analysis, the researchers adjusted for the aforementioned variables as well as body mass index, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, glomerular filtration rate, cholesterol, serum iron, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of coronary heart disease, history of stroke, history of cancer, APOE4, smoking, severe depressive symptoms, and use of antidepressants. The OR after adjustment for these factors was 1.92 (P=0.04).

Similar results were found for aMCI and naMCI. The researchers said this suggests that having a low hemoglobin level may contribute to cognitive impairment via different pathways.

The team believes that, overall, their study results indicate that anemia is associated with an increased risk of MCI independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. They said the association between anemia and MCI has important clinical relevance because—depending on etiology—anemia can be treated effectively, and this might provide means to prevent or delay cognitive decline. ![]()

The Social Worker’s Role in Delirium Care for Hospitalized Veterans

Delirium, or the state of mental confusion that may occur with physical or mental illness, is common, morbid, and costly; however, of the diagnosed cases, delirium is mentioned in hospital discharge summaries only 16% to 55% of the time.1-3

Social workers often coordinate care transitions for hospitalized older veterans. They serve as interdisciplinary team members who communicate with VA medical staff as well as with the patient and family. This position, in addition to their training in communication and advocacy, primes social workers for a role in delirium care and provides the needed support for veterans who experience delirium and their families.

Background

Delirium is a sudden disturbance of attention with reduced awareness of the environment. Because attention is impaired, other changes in cognition are common, including perceptual and thought disturbances. Additionally, delirium includes fluctuations in consciousness over the course of a day. The acute development of these cognitive disturbances is distinct from a preexisting chronic cognitive impairment, such as dementia. Delirium is a direct consequence of underlying medical conditions, such as infections, polypharmacy, dehydration, and surgery.4

Delirium subtypes all have inattention as a core symptom. In half of the cases, patients are hypoactive and will not awaken easily or participate in daily care plans readily.4 Hyperactive delirium occurs in a quarter of cases. In the remaining mixed delirium cases patients fluctuate between the 2 states.4

Delirium is often falsely mistaken for dementia. Although delirium and dementia can present similarly, delirium has a sudden onset, which can alert health care professionals (HCPs) to the likelihood of delirium. Another important distinction is that delirium is typically reversible. Symptom manifestations of delirium may also be confused with depression.

Related: Delirium in the Cardiac ICU

Preventing delirium is important due to its many negative health outcomes. Older adults who develop delirium are more likely to die sooner. In a Canadian study of hospitalized patients aged ≥ 65 years, 41.6% of the delirium cohort and 14.4% of the control group died within 12 months of hospital admission.5 The death rate predicted by delirium in the Canadian study was comparable to the death rate of those who experience other serious medical conditions, such as sepsis or a heart attack.6

Those who survive delirium experience other serious outcomes, such as a negative impact on function and cognition and an increase in long-term care placement.7 Even when the condition resolves quickly, lasting functional impairment may be evident without return to baseline functioning.8 Hospitalized veterans are generally older, making them susceptible to developing delirium.9

Prevalence

Delirium can result from multiple medical conditions and develops in up to 50% of patients after general surgery and up to 80% of patients in the intensive care unit.10,11 From 20% to 40% of hospitalized older adults and from 50% to 89% of patients with preexisting Alzheimer disease may develop delirium.12-15 The increasing number of aging adults who will be hospitalized may also result in an increased prevalence of delirium.1,16

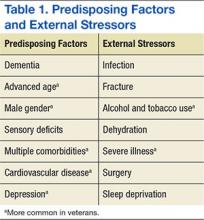

Delirium is a result of various predisposing and precipitating factors.1 Predisposing vulnerabilities are intrinsic to the individual, whereas precipitating external stressors are found in the environment. External stressors may trigger delirium in an individual who is vulnerable due to predisposing risk. The primary risk factors for delirium include dementia, advanced age, sensory impairment, fracture, infection, and dehydration (Table 1).12

Predisposing factors for delirium, such as age and sex, lifestyle choices (alcohol, tobacco), and chronic conditions (atherosclerosis, depression, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack) are more prevalent in the veteran population.9,17-20 In 2011, the median age for male veterans was 64 and the median age for male nonveterans was 41. Of male veterans, 49.9% are aged ≥ 65 years in comparison with 10.5% of the nonveteran male population.21 Veterans also have higher rates of comorbidities; a significant risk factor for delirium.20 A study by Agha and colleagues found that veterans were 14 times more likely to have 5 or more medical conditions than that of the general population.9 In a study comparing veterans aged ≥ 65 years with their age matched nonveteran peers, the health status of the veterans was poorer overall.22 Veterans are more likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder, which can increase the risk of postsurgery delirium and dementia, a primary risk factor for delirium.23-26

Delirium Intervention

Up to 40% of delirium cases can be prevented.27 But delirium may remain undetected in older veterans because its symptoms are sometimes thought to be the unavoidable consequences of aging, dementia, preexisting mental health conditions, substance abuse, a disease process, or the hospital environment.28 Therefore, to avoid the negative consequences of delirium, prevention is critical.28

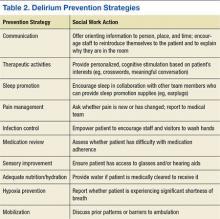

The goals of delirium treatment are to identify and reverse its underlying cause(s).29 Because delirium is typically multifactorial, an HCP must carefully consider the various sources that could have initiated a change in mental status. Delirium may be prevented if HCPs can reduce patient risk factors. The 2010 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Delirium Guideline recommended a set of prevention strategies to address delirium risk factors (Table 2).12

As a member of the health care team, social workers can help prevent delirium through attention to pain management, infection control, medication review, sensory improvement, adequate nutrition and hydration, hypoxia prevention, and mobilization.12No pharmacologic approach has been approved for the treatment of delirium.30 Drugs may manage symptoms associated with delirium, but they do not treat the disease and could be associated with toxicity in high-risk patients. However, there are a variety of nonpharmacologic preventative measures that have proven effective. Environmental interventions to prevent delirium include orientation, cognitive stimulation, and sensory aids. A 2013 meta-analysis of 19 delirium prevention programs found that most were effective in preventing delirium in patients at risk during hospitalization.31 This review found that the most successful programs included multidisciplinary teams providing staff education and therapeutic cognitive activities.31 Social workers can encourage and directly provide such services. The Delirium Toolbox is a delirium risk modification program that was piloted with frontline staff, including social workers, at the VA Boston Healthcare System in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, and has been associated with restraint reduction, shortened length of stay (LOS), and lower variable direct costs.32

Social Worker Role

Several studies, both national and international, have indicated that little has been done over the past 2 decades to increase the diagnosis of delirium, because only 12% to 35% of delirium cases are clinically detected within the emergency department and in acute care settings.33-37 Patients may hesitate to report their experience due to a sense of embarrassment or because of an inability to describe it.38

Social workers are skilled at helping individuals feel more at ease when disclosing distressing experiences. Delirium is relevant to HCPs and hospital social workers with care transition responsibilities, because delirium detection should impact discharge planning.1,39 Delirium education needs to be included in efforts to improve transitions from intensive care settings to lower levels of care and from lower levels of care to discharge.40 Hospital social workers are in a position to offer additional support because they see patients at a critical juncture in their care and can take steps to improve postdischarge outcomes.41

Prior to Onset

Social workers can play an important role prior to delirium onset.42 Patient education on delirium needs to be provided during the routine hospital intake assessment. Informing patients in advance that delirium is common, based on their risk factors, as well as what to expect if delirium is experienced has been found to provide comfort.38 Families who anticipated possible delirium-related confusion reported that they experienced less distress.38

Related: Baseball Reminiscence Therapy for Cognitively Impaired Veterans

During hospitalization, social workers can ascertain from families whether an alteration in mental status is a rapid change, possibly indicating delirium, or a gradual dementia onset. The social work skills of advocacy and education can be used to support delirium-risk identification to avoid adverse outcomes.43 When no family caregiver is present to provide a history of the individual’s cognitive function prior to hospitalization, the social worker may be the first to notice an acute change in cognitive status and can report this to the medical team.

During Delirium

Lack of patient responsiveness and difficulty following a conversation are possible signs of delirium. This situation should be reported to the medical team for further delirium assessment and diagnosis.4 The social worker can also attempt to determine whether a patient’s presentation is unusual by contacting the family. Social work training recognizes the important role of the family.44 Social workers often interact with families at the critical period between acute onset of delirium in the hospital and discharge.42 Studies have shown that delirium causes stress for the patient’s loved ones. Moreover, caregivers of patients who experience the syndrome are at a 12 times increased risk of meeting the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder.30 In one study, delirium was rated as more distressing for the caregivers who witnessed it than for the patients who experienced it.38 Education has been shown to reduce delirium-related distress.30

In cases where delirium is irreversible, such as during the active dying process, social workers can serve in a palliative role to ease family confusion and provide comfort.30 The presence of family and other familiar people are considered part of the nonpharmacologic management of delirium.28

Posthospitalization

Delirium complicates physical aspects of care for families, as their loved one may need direct care in areas where they were previously independent due to a loss of function. Logistic considerations such as increased supervision may be necessary due to delirium, and the patient’s condition may be upsetting and confusing for family members, triggering the need for emotional support. During the discharge process, social workers can provide support and education to family members or placement facilities.38

Social workers in the hospital setting are often responsible for discharge planning, including the reduction of extended LOS and unnecessary readmissions to the hospital.45 Increased LOS and hospital readmissions are 2 of the primary negative outcomes associated with delirium. Delirium can persist for months beyond hospitalization, making it a relevant issue at the time of discharge and beyond.46 Distress related to delirium has been documented up to 2 years after onset, due to manifestations of anxiety and depression.38

Distress impacts patients as well as caregivers who witness the delirium and provide care to the patient afterward.38 Long-term changes in mood in addition to loss of function as a result of delirium can lead to an increase in stress for both patients and their caregivers.30 The social work emphasis on counseling and family dynamics as well as the common role of coordinating post-discharge arrangements makes the profession uniquely suited for delirium care.

Barriers

Social workers can play a key role in delirium risk identification and coordination of care but face substantial barriers. Delirium assessments are complex and require training and education in the features of delirium and cognitive assessment.47 To date, social workers receive limited education about delirium and typically do not make deliberate efforts in prevention, support, and follow-up care.

Conclusion

Social workers will encounter delirium, and their training makes them particularly suited to address this health concern. An understanding of the larger ecologic system is a foundational aspect of social work and an essential component of delirium prevention and care.41 The multipathway nature of delirium as well as the importance of prevention suggests that multiple disciplines, including social work, should be involved.1 The American Delirium Society and the European Delirium Association both recognize the need for all HCPs to be engaged in delirium care.1,48

Related: Sharing Alzheimer Research, FasterSharing Alzheimer Research, Faster

Social workers in the hospital setting provide communication, advocacy, and education to other HCPs, as well as to patients and families (Figure). Because delirium directly impacts the emotional and logistic needs of patients and their families, it would be advantageous for social workers to take a more active role in delirium risk identification, prevention, and care. Fortunately, the nonpharmacologic approaches that social workers are skilled in providing (eg, education and emotional support) have been shown to benefit patients with delirium and their families.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Rudolph JL, Boustani M, Kamholz B, Shaughnessey M, Shay K; American Delirium Society. Delirium: a strategic plan to bring an ancient disease into the 21st century. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S237-S240.

2. Hope C, Estrada N, Weir C, Teng CC, Damal K, Sauer BC. Documentation of delirium in the VA electronic health record. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:208.

3. van Zyl LT, Davidson PR. Delirium in hospital: an underreported event at discharge. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(8):555-560.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, Primeau F, Belzile E. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):457-463.

6. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

7. McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, Belzile E, Primeau F. Delirium in older medical inpatients and subsequent cognitive and functional status: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2001;165(5):575-583.

8. Quinlan N, Rudolph JL. Postoperative delirium and functional decline after noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S301-S304.

9. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257.

10. Marcantonio ER, Simon SE, Bergmann MA, Jones RN, Murphy KM, Morris JN. Delirium symptoms in post-acute care: prevalent, persistent, and associated with poor functional recovery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):4-9.

11. McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):591-598.

12. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Delirium: Diagnosis, Prevention and Management. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103/resources/delirium-174507018181. Published July 2010.

13. Fick D, Foreman M. Consequences of not recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia in hospitalized elderly individuals. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26(1):30-40.

14. Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1723-1732.

15. Edlund A, Lundström M, Brännström B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. Delirium before and after operation for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(10):1335-1340.

16. Popejoy LL, Galambos C, Moylan K, Madsen R. Challenges to hospital discharge planning for older adults. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21(4):431-449.

17. Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134-139.

18. Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Rasmussen LS, Silverstein JH, Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER. Independent vascular and cognitive risk factors for postoperative delirium. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):807-813.

19. Rudolph JL, Babikian VL, Birjiniuk V, et al. Atherosclerosis is associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):462-466.

20. Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(2):229-236.

21. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of Veterans: 2013 Data from the American Community Survey. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2013.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2015.

22. Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al. The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1271-1276.

23. McGuire JM. The incidence of and risk factors for emergence delirium in U.S. military combat veterans. J Perianesth Nurs. 2012;27(4):236-245.

24. Lepousé C, Lautner CA, Liu L, Gomis P, Leon A. Emergence delirium in adults in the post-anaesthesia care unit. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(6):747-753.

25. Meziab O, Kirby KA, Williams B, Yaffe K, Byers AL, Barnes DE. Prisoner of war status, posttraumatic stress disorder, and dementia in older veterans. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3)(suppl):S236-S241.

26. Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bellavance F. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):204-212.

27. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

28. Conley DM. The gerontological clinical nurse specialist's role in prevention, early recognition, and management of delirium in hospitalized older adults. Urol Nurs. 2011;31(6):337-342.

29. Meagher DJ. Delirium: optimising management. BMJ. 2001;322(7279):144-149.

30. Irwin SA, Pirrello RD, Hirst JM, Buckholz GT, Ferris FD. Clarifying delirium management: practical, evidenced-based, expert recommendations for clinical practice. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(4):423-435.

31. Reston JT, Schoelles KM. In-facility delirium prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5, pt 2):375-380.

32. Rudolph JL, Archambault E, Kelly B; VA Boston Delirium Task Force. A delirium risk modification program is associated with hospital outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):957.e7-957.e11.

33. Gustafson Y, Brännström B, Norberg A, Bucht G, Winblad B. Underdiagnosis and poor documentation of acute confusional states in elderly hip fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(8):760-765.

34. Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):248-253.

35. Kales HC, Kamholz BA, Visnic SG, Blow FC. Recorded delirium in a national sample of elderly inpatients: potential implications for recognition. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(1):32-38.

36. Lemiengre J, Nelis T, Joosten E, et al. Detection of delirium by bedside nurses using the confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):685-689.

37. Milisen K, Foreman MD, Wouters B, et al. Documentation of delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002;28(11):23-29.

38. Partridge JS, Martin FC, Harari D, Dhesi JK. The delirium experience: what is the effect on patients, relatives and staff and what can be done to modify this? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(8):804-812.

39. Simons K, Connolly RP, Bonifas R, et al. Psychosocial assessment of nursing home residents via MDS 3.0: recommendations for social service training, staffing, and roles in interdisciplinary care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(2):190.e9-190.e15.

40. Alici Y. Interventions to improve recognition of delirium: a sine qua non for successful transitional care programs. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(1):80-82.

41. Judd RG, Sheffield S. Hospital social work: contemporary roles and professional activities. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49(9):856-871.

42. Duffy F, Healy JP. Social work with older people in a hospital setting. Soc Work Health Care. 2011;50(2):109-123.

43. Anderson CP, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Complications in post-acute care are associated with persistent delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1122-1127.

44. Bauer M, Fitzgerald L, Haesler E, Manfrin M. Hospital discharge planning for frail older people and their family. Are we delivering best practice? A review of the evidence. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(18):2539-2546.

45. Shepperd S, Lannin NA, Clemson LM, McCluskey A, Cameron ID, Barras SL. Discharge planning from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD000313.

46. McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, Han L, Belzile E. The course of delirium in older medical inpatients: A prospective study. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):696-704.

47. Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM Jr. Nurses' recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467-2473.

48. Teodorczuk A, Reynish E, Milisen K. Improving recognition of delirium in clinical practice: a call for action. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:55.

Delirium, or the state of mental confusion that may occur with physical or mental illness, is common, morbid, and costly; however, of the diagnosed cases, delirium is mentioned in hospital discharge summaries only 16% to 55% of the time.1-3

Social workers often coordinate care transitions for hospitalized older veterans. They serve as interdisciplinary team members who communicate with VA medical staff as well as with the patient and family. This position, in addition to their training in communication and advocacy, primes social workers for a role in delirium care and provides the needed support for veterans who experience delirium and their families.

Background

Delirium is a sudden disturbance of attention with reduced awareness of the environment. Because attention is impaired, other changes in cognition are common, including perceptual and thought disturbances. Additionally, delirium includes fluctuations in consciousness over the course of a day. The acute development of these cognitive disturbances is distinct from a preexisting chronic cognitive impairment, such as dementia. Delirium is a direct consequence of underlying medical conditions, such as infections, polypharmacy, dehydration, and surgery.4

Delirium subtypes all have inattention as a core symptom. In half of the cases, patients are hypoactive and will not awaken easily or participate in daily care plans readily.4 Hyperactive delirium occurs in a quarter of cases. In the remaining mixed delirium cases patients fluctuate between the 2 states.4

Delirium is often falsely mistaken for dementia. Although delirium and dementia can present similarly, delirium has a sudden onset, which can alert health care professionals (HCPs) to the likelihood of delirium. Another important distinction is that delirium is typically reversible. Symptom manifestations of delirium may also be confused with depression.

Related: Delirium in the Cardiac ICU

Preventing delirium is important due to its many negative health outcomes. Older adults who develop delirium are more likely to die sooner. In a Canadian study of hospitalized patients aged ≥ 65 years, 41.6% of the delirium cohort and 14.4% of the control group died within 12 months of hospital admission.5 The death rate predicted by delirium in the Canadian study was comparable to the death rate of those who experience other serious medical conditions, such as sepsis or a heart attack.6

Those who survive delirium experience other serious outcomes, such as a negative impact on function and cognition and an increase in long-term care placement.7 Even when the condition resolves quickly, lasting functional impairment may be evident without return to baseline functioning.8 Hospitalized veterans are generally older, making them susceptible to developing delirium.9

Prevalence

Delirium can result from multiple medical conditions and develops in up to 50% of patients after general surgery and up to 80% of patients in the intensive care unit.10,11 From 20% to 40% of hospitalized older adults and from 50% to 89% of patients with preexisting Alzheimer disease may develop delirium.12-15 The increasing number of aging adults who will be hospitalized may also result in an increased prevalence of delirium.1,16

Delirium is a result of various predisposing and precipitating factors.1 Predisposing vulnerabilities are intrinsic to the individual, whereas precipitating external stressors are found in the environment. External stressors may trigger delirium in an individual who is vulnerable due to predisposing risk. The primary risk factors for delirium include dementia, advanced age, sensory impairment, fracture, infection, and dehydration (Table 1).12

Predisposing factors for delirium, such as age and sex, lifestyle choices (alcohol, tobacco), and chronic conditions (atherosclerosis, depression, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack) are more prevalent in the veteran population.9,17-20 In 2011, the median age for male veterans was 64 and the median age for male nonveterans was 41. Of male veterans, 49.9% are aged ≥ 65 years in comparison with 10.5% of the nonveteran male population.21 Veterans also have higher rates of comorbidities; a significant risk factor for delirium.20 A study by Agha and colleagues found that veterans were 14 times more likely to have 5 or more medical conditions than that of the general population.9 In a study comparing veterans aged ≥ 65 years with their age matched nonveteran peers, the health status of the veterans was poorer overall.22 Veterans are more likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder, which can increase the risk of postsurgery delirium and dementia, a primary risk factor for delirium.23-26

Delirium Intervention

Up to 40% of delirium cases can be prevented.27 But delirium may remain undetected in older veterans because its symptoms are sometimes thought to be the unavoidable consequences of aging, dementia, preexisting mental health conditions, substance abuse, a disease process, or the hospital environment.28 Therefore, to avoid the negative consequences of delirium, prevention is critical.28

The goals of delirium treatment are to identify and reverse its underlying cause(s).29 Because delirium is typically multifactorial, an HCP must carefully consider the various sources that could have initiated a change in mental status. Delirium may be prevented if HCPs can reduce patient risk factors. The 2010 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Delirium Guideline recommended a set of prevention strategies to address delirium risk factors (Table 2).12

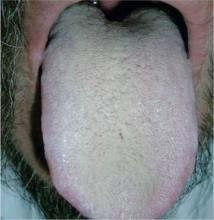

As a member of the health care team, social workers can help prevent delirium through attention to pain management, infection control, medication review, sensory improvement, adequate nutrition and hydration, hypoxia prevention, and mobilization.12No pharmacologic approach has been approved for the treatment of delirium.30 Drugs may manage symptoms associated with delirium, but they do not treat the disease and could be associated with toxicity in high-risk patients. However, there are a variety of nonpharmacologic preventative measures that have proven effective. Environmental interventions to prevent delirium include orientation, cognitive stimulation, and sensory aids. A 2013 meta-analysis of 19 delirium prevention programs found that most were effective in preventing delirium in patients at risk during hospitalization.31 This review found that the most successful programs included multidisciplinary teams providing staff education and therapeutic cognitive activities.31 Social workers can encourage and directly provide such services. The Delirium Toolbox is a delirium risk modification program that was piloted with frontline staff, including social workers, at the VA Boston Healthcare System in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, and has been associated with restraint reduction, shortened length of stay (LOS), and lower variable direct costs.32

Social Worker Role

Several studies, both national and international, have indicated that little has been done over the past 2 decades to increase the diagnosis of delirium, because only 12% to 35% of delirium cases are clinically detected within the emergency department and in acute care settings.33-37 Patients may hesitate to report their experience due to a sense of embarrassment or because of an inability to describe it.38

Social workers are skilled at helping individuals feel more at ease when disclosing distressing experiences. Delirium is relevant to HCPs and hospital social workers with care transition responsibilities, because delirium detection should impact discharge planning.1,39 Delirium education needs to be included in efforts to improve transitions from intensive care settings to lower levels of care and from lower levels of care to discharge.40 Hospital social workers are in a position to offer additional support because they see patients at a critical juncture in their care and can take steps to improve postdischarge outcomes.41

Prior to Onset

Social workers can play an important role prior to delirium onset.42 Patient education on delirium needs to be provided during the routine hospital intake assessment. Informing patients in advance that delirium is common, based on their risk factors, as well as what to expect if delirium is experienced has been found to provide comfort.38 Families who anticipated possible delirium-related confusion reported that they experienced less distress.38

Related: Baseball Reminiscence Therapy for Cognitively Impaired Veterans

During hospitalization, social workers can ascertain from families whether an alteration in mental status is a rapid change, possibly indicating delirium, or a gradual dementia onset. The social work skills of advocacy and education can be used to support delirium-risk identification to avoid adverse outcomes.43 When no family caregiver is present to provide a history of the individual’s cognitive function prior to hospitalization, the social worker may be the first to notice an acute change in cognitive status and can report this to the medical team.

During Delirium

Lack of patient responsiveness and difficulty following a conversation are possible signs of delirium. This situation should be reported to the medical team for further delirium assessment and diagnosis.4 The social worker can also attempt to determine whether a patient’s presentation is unusual by contacting the family. Social work training recognizes the important role of the family.44 Social workers often interact with families at the critical period between acute onset of delirium in the hospital and discharge.42 Studies have shown that delirium causes stress for the patient’s loved ones. Moreover, caregivers of patients who experience the syndrome are at a 12 times increased risk of meeting the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder.30 In one study, delirium was rated as more distressing for the caregivers who witnessed it than for the patients who experienced it.38 Education has been shown to reduce delirium-related distress.30

In cases where delirium is irreversible, such as during the active dying process, social workers can serve in a palliative role to ease family confusion and provide comfort.30 The presence of family and other familiar people are considered part of the nonpharmacologic management of delirium.28

Posthospitalization

Delirium complicates physical aspects of care for families, as their loved one may need direct care in areas where they were previously independent due to a loss of function. Logistic considerations such as increased supervision may be necessary due to delirium, and the patient’s condition may be upsetting and confusing for family members, triggering the need for emotional support. During the discharge process, social workers can provide support and education to family members or placement facilities.38

Social workers in the hospital setting are often responsible for discharge planning, including the reduction of extended LOS and unnecessary readmissions to the hospital.45 Increased LOS and hospital readmissions are 2 of the primary negative outcomes associated with delirium. Delirium can persist for months beyond hospitalization, making it a relevant issue at the time of discharge and beyond.46 Distress related to delirium has been documented up to 2 years after onset, due to manifestations of anxiety and depression.38

Distress impacts patients as well as caregivers who witness the delirium and provide care to the patient afterward.38 Long-term changes in mood in addition to loss of function as a result of delirium can lead to an increase in stress for both patients and their caregivers.30 The social work emphasis on counseling and family dynamics as well as the common role of coordinating post-discharge arrangements makes the profession uniquely suited for delirium care.

Barriers

Social workers can play a key role in delirium risk identification and coordination of care but face substantial barriers. Delirium assessments are complex and require training and education in the features of delirium and cognitive assessment.47 To date, social workers receive limited education about delirium and typically do not make deliberate efforts in prevention, support, and follow-up care.

Conclusion

Social workers will encounter delirium, and their training makes them particularly suited to address this health concern. An understanding of the larger ecologic system is a foundational aspect of social work and an essential component of delirium prevention and care.41 The multipathway nature of delirium as well as the importance of prevention suggests that multiple disciplines, including social work, should be involved.1 The American Delirium Society and the European Delirium Association both recognize the need for all HCPs to be engaged in delirium care.1,48

Related: Sharing Alzheimer Research, FasterSharing Alzheimer Research, Faster

Social workers in the hospital setting provide communication, advocacy, and education to other HCPs, as well as to patients and families (Figure). Because delirium directly impacts the emotional and logistic needs of patients and their families, it would be advantageous for social workers to take a more active role in delirium risk identification, prevention, and care. Fortunately, the nonpharmacologic approaches that social workers are skilled in providing (eg, education and emotional support) have been shown to benefit patients with delirium and their families.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Delirium, or the state of mental confusion that may occur with physical or mental illness, is common, morbid, and costly; however, of the diagnosed cases, delirium is mentioned in hospital discharge summaries only 16% to 55% of the time.1-3

Social workers often coordinate care transitions for hospitalized older veterans. They serve as interdisciplinary team members who communicate with VA medical staff as well as with the patient and family. This position, in addition to their training in communication and advocacy, primes social workers for a role in delirium care and provides the needed support for veterans who experience delirium and their families.

Background

Delirium is a sudden disturbance of attention with reduced awareness of the environment. Because attention is impaired, other changes in cognition are common, including perceptual and thought disturbances. Additionally, delirium includes fluctuations in consciousness over the course of a day. The acute development of these cognitive disturbances is distinct from a preexisting chronic cognitive impairment, such as dementia. Delirium is a direct consequence of underlying medical conditions, such as infections, polypharmacy, dehydration, and surgery.4

Delirium subtypes all have inattention as a core symptom. In half of the cases, patients are hypoactive and will not awaken easily or participate in daily care plans readily.4 Hyperactive delirium occurs in a quarter of cases. In the remaining mixed delirium cases patients fluctuate between the 2 states.4

Delirium is often falsely mistaken for dementia. Although delirium and dementia can present similarly, delirium has a sudden onset, which can alert health care professionals (HCPs) to the likelihood of delirium. Another important distinction is that delirium is typically reversible. Symptom manifestations of delirium may also be confused with depression.

Related: Delirium in the Cardiac ICU

Preventing delirium is important due to its many negative health outcomes. Older adults who develop delirium are more likely to die sooner. In a Canadian study of hospitalized patients aged ≥ 65 years, 41.6% of the delirium cohort and 14.4% of the control group died within 12 months of hospital admission.5 The death rate predicted by delirium in the Canadian study was comparable to the death rate of those who experience other serious medical conditions, such as sepsis or a heart attack.6

Those who survive delirium experience other serious outcomes, such as a negative impact on function and cognition and an increase in long-term care placement.7 Even when the condition resolves quickly, lasting functional impairment may be evident without return to baseline functioning.8 Hospitalized veterans are generally older, making them susceptible to developing delirium.9

Prevalence

Delirium can result from multiple medical conditions and develops in up to 50% of patients after general surgery and up to 80% of patients in the intensive care unit.10,11 From 20% to 40% of hospitalized older adults and from 50% to 89% of patients with preexisting Alzheimer disease may develop delirium.12-15 The increasing number of aging adults who will be hospitalized may also result in an increased prevalence of delirium.1,16

Delirium is a result of various predisposing and precipitating factors.1 Predisposing vulnerabilities are intrinsic to the individual, whereas precipitating external stressors are found in the environment. External stressors may trigger delirium in an individual who is vulnerable due to predisposing risk. The primary risk factors for delirium include dementia, advanced age, sensory impairment, fracture, infection, and dehydration (Table 1).12

Predisposing factors for delirium, such as age and sex, lifestyle choices (alcohol, tobacco), and chronic conditions (atherosclerosis, depression, prior stroke/transient ischemic attack) are more prevalent in the veteran population.9,17-20 In 2011, the median age for male veterans was 64 and the median age for male nonveterans was 41. Of male veterans, 49.9% are aged ≥ 65 years in comparison with 10.5% of the nonveteran male population.21 Veterans also have higher rates of comorbidities; a significant risk factor for delirium.20 A study by Agha and colleagues found that veterans were 14 times more likely to have 5 or more medical conditions than that of the general population.9 In a study comparing veterans aged ≥ 65 years with their age matched nonveteran peers, the health status of the veterans was poorer overall.22 Veterans are more likely to have posttraumatic stress disorder, which can increase the risk of postsurgery delirium and dementia, a primary risk factor for delirium.23-26

Delirium Intervention

Up to 40% of delirium cases can be prevented.27 But delirium may remain undetected in older veterans because its symptoms are sometimes thought to be the unavoidable consequences of aging, dementia, preexisting mental health conditions, substance abuse, a disease process, or the hospital environment.28 Therefore, to avoid the negative consequences of delirium, prevention is critical.28

The goals of delirium treatment are to identify and reverse its underlying cause(s).29 Because delirium is typically multifactorial, an HCP must carefully consider the various sources that could have initiated a change in mental status. Delirium may be prevented if HCPs can reduce patient risk factors. The 2010 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Delirium Guideline recommended a set of prevention strategies to address delirium risk factors (Table 2).12

As a member of the health care team, social workers can help prevent delirium through attention to pain management, infection control, medication review, sensory improvement, adequate nutrition and hydration, hypoxia prevention, and mobilization.12No pharmacologic approach has been approved for the treatment of delirium.30 Drugs may manage symptoms associated with delirium, but they do not treat the disease and could be associated with toxicity in high-risk patients. However, there are a variety of nonpharmacologic preventative measures that have proven effective. Environmental interventions to prevent delirium include orientation, cognitive stimulation, and sensory aids. A 2013 meta-analysis of 19 delirium prevention programs found that most were effective in preventing delirium in patients at risk during hospitalization.31 This review found that the most successful programs included multidisciplinary teams providing staff education and therapeutic cognitive activities.31 Social workers can encourage and directly provide such services. The Delirium Toolbox is a delirium risk modification program that was piloted with frontline staff, including social workers, at the VA Boston Healthcare System in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, and has been associated with restraint reduction, shortened length of stay (LOS), and lower variable direct costs.32

Social Worker Role

Several studies, both national and international, have indicated that little has been done over the past 2 decades to increase the diagnosis of delirium, because only 12% to 35% of delirium cases are clinically detected within the emergency department and in acute care settings.33-37 Patients may hesitate to report their experience due to a sense of embarrassment or because of an inability to describe it.38

Social workers are skilled at helping individuals feel more at ease when disclosing distressing experiences. Delirium is relevant to HCPs and hospital social workers with care transition responsibilities, because delirium detection should impact discharge planning.1,39 Delirium education needs to be included in efforts to improve transitions from intensive care settings to lower levels of care and from lower levels of care to discharge.40 Hospital social workers are in a position to offer additional support because they see patients at a critical juncture in their care and can take steps to improve postdischarge outcomes.41

Prior to Onset

Social workers can play an important role prior to delirium onset.42 Patient education on delirium needs to be provided during the routine hospital intake assessment. Informing patients in advance that delirium is common, based on their risk factors, as well as what to expect if delirium is experienced has been found to provide comfort.38 Families who anticipated possible delirium-related confusion reported that they experienced less distress.38

Related: Baseball Reminiscence Therapy for Cognitively Impaired Veterans

During hospitalization, social workers can ascertain from families whether an alteration in mental status is a rapid change, possibly indicating delirium, or a gradual dementia onset. The social work skills of advocacy and education can be used to support delirium-risk identification to avoid adverse outcomes.43 When no family caregiver is present to provide a history of the individual’s cognitive function prior to hospitalization, the social worker may be the first to notice an acute change in cognitive status and can report this to the medical team.

During Delirium

Lack of patient responsiveness and difficulty following a conversation are possible signs of delirium. This situation should be reported to the medical team for further delirium assessment and diagnosis.4 The social worker can also attempt to determine whether a patient’s presentation is unusual by contacting the family. Social work training recognizes the important role of the family.44 Social workers often interact with families at the critical period between acute onset of delirium in the hospital and discharge.42 Studies have shown that delirium causes stress for the patient’s loved ones. Moreover, caregivers of patients who experience the syndrome are at a 12 times increased risk of meeting the criteria for generalized anxiety disorder.30 In one study, delirium was rated as more distressing for the caregivers who witnessed it than for the patients who experienced it.38 Education has been shown to reduce delirium-related distress.30

In cases where delirium is irreversible, such as during the active dying process, social workers can serve in a palliative role to ease family confusion and provide comfort.30 The presence of family and other familiar people are considered part of the nonpharmacologic management of delirium.28

Posthospitalization

Delirium complicates physical aspects of care for families, as their loved one may need direct care in areas where they were previously independent due to a loss of function. Logistic considerations such as increased supervision may be necessary due to delirium, and the patient’s condition may be upsetting and confusing for family members, triggering the need for emotional support. During the discharge process, social workers can provide support and education to family members or placement facilities.38

Social workers in the hospital setting are often responsible for discharge planning, including the reduction of extended LOS and unnecessary readmissions to the hospital.45 Increased LOS and hospital readmissions are 2 of the primary negative outcomes associated with delirium. Delirium can persist for months beyond hospitalization, making it a relevant issue at the time of discharge and beyond.46 Distress related to delirium has been documented up to 2 years after onset, due to manifestations of anxiety and depression.38

Distress impacts patients as well as caregivers who witness the delirium and provide care to the patient afterward.38 Long-term changes in mood in addition to loss of function as a result of delirium can lead to an increase in stress for both patients and their caregivers.30 The social work emphasis on counseling and family dynamics as well as the common role of coordinating post-discharge arrangements makes the profession uniquely suited for delirium care.

Barriers

Social workers can play a key role in delirium risk identification and coordination of care but face substantial barriers. Delirium assessments are complex and require training and education in the features of delirium and cognitive assessment.47 To date, social workers receive limited education about delirium and typically do not make deliberate efforts in prevention, support, and follow-up care.

Conclusion

Social workers will encounter delirium, and their training makes them particularly suited to address this health concern. An understanding of the larger ecologic system is a foundational aspect of social work and an essential component of delirium prevention and care.41 The multipathway nature of delirium as well as the importance of prevention suggests that multiple disciplines, including social work, should be involved.1 The American Delirium Society and the European Delirium Association both recognize the need for all HCPs to be engaged in delirium care.1,48

Related: Sharing Alzheimer Research, FasterSharing Alzheimer Research, Faster

Social workers in the hospital setting provide communication, advocacy, and education to other HCPs, as well as to patients and families (Figure). Because delirium directly impacts the emotional and logistic needs of patients and their families, it would be advantageous for social workers to take a more active role in delirium risk identification, prevention, and care. Fortunately, the nonpharmacologic approaches that social workers are skilled in providing (eg, education and emotional support) have been shown to benefit patients with delirium and their families.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Rudolph JL, Boustani M, Kamholz B, Shaughnessey M, Shay K; American Delirium Society. Delirium: a strategic plan to bring an ancient disease into the 21st century. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S237-S240.

2. Hope C, Estrada N, Weir C, Teng CC, Damal K, Sauer BC. Documentation of delirium in the VA electronic health record. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:208.

3. van Zyl LT, Davidson PR. Delirium in hospital: an underreported event at discharge. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(8):555-560.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, Primeau F, Belzile E. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):457-463.

6. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

7. McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, Belzile E, Primeau F. Delirium in older medical inpatients and subsequent cognitive and functional status: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2001;165(5):575-583.

8. Quinlan N, Rudolph JL. Postoperative delirium and functional decline after noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S301-S304.

9. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257.

10. Marcantonio ER, Simon SE, Bergmann MA, Jones RN, Murphy KM, Morris JN. Delirium symptoms in post-acute care: prevalent, persistent, and associated with poor functional recovery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):4-9.

11. McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):591-598.

12. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Delirium: Diagnosis, Prevention and Management. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103/resources/delirium-174507018181. Published July 2010.

13. Fick D, Foreman M. Consequences of not recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia in hospitalized elderly individuals. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26(1):30-40.

14. Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1723-1732.

15. Edlund A, Lundström M, Brännström B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. Delirium before and after operation for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(10):1335-1340.

16. Popejoy LL, Galambos C, Moylan K, Madsen R. Challenges to hospital discharge planning for older adults. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21(4):431-449.

17. Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134-139.

18. Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Rasmussen LS, Silverstein JH, Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER. Independent vascular and cognitive risk factors for postoperative delirium. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):807-813.

19. Rudolph JL, Babikian VL, Birjiniuk V, et al. Atherosclerosis is associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):462-466.

20. Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(2):229-236.

21. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of Veterans: 2013 Data from the American Community Survey. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2013.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2015.

22. Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al. The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1271-1276.

23. McGuire JM. The incidence of and risk factors for emergence delirium in U.S. military combat veterans. J Perianesth Nurs. 2012;27(4):236-245.

24. Lepousé C, Lautner CA, Liu L, Gomis P, Leon A. Emergence delirium in adults in the post-anaesthesia care unit. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(6):747-753.

25. Meziab O, Kirby KA, Williams B, Yaffe K, Byers AL, Barnes DE. Prisoner of war status, posttraumatic stress disorder, and dementia in older veterans. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3)(suppl):S236-S241.

26. Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bellavance F. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):204-212.

27. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

28. Conley DM. The gerontological clinical nurse specialist's role in prevention, early recognition, and management of delirium in hospitalized older adults. Urol Nurs. 2011;31(6):337-342.

29. Meagher DJ. Delirium: optimising management. BMJ. 2001;322(7279):144-149.

30. Irwin SA, Pirrello RD, Hirst JM, Buckholz GT, Ferris FD. Clarifying delirium management: practical, evidenced-based, expert recommendations for clinical practice. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(4):423-435.

31. Reston JT, Schoelles KM. In-facility delirium prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5, pt 2):375-380.

32. Rudolph JL, Archambault E, Kelly B; VA Boston Delirium Task Force. A delirium risk modification program is associated with hospital outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):957.e7-957.e11.

33. Gustafson Y, Brännström B, Norberg A, Bucht G, Winblad B. Underdiagnosis and poor documentation of acute confusional states in elderly hip fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(8):760-765.

34. Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):248-253.

35. Kales HC, Kamholz BA, Visnic SG, Blow FC. Recorded delirium in a national sample of elderly inpatients: potential implications for recognition. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16(1):32-38.

36. Lemiengre J, Nelis T, Joosten E, et al. Detection of delirium by bedside nurses using the confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(4):685-689.

37. Milisen K, Foreman MD, Wouters B, et al. Documentation of delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture. J Gerontol Nurs. 2002;28(11):23-29.

38. Partridge JS, Martin FC, Harari D, Dhesi JK. The delirium experience: what is the effect on patients, relatives and staff and what can be done to modify this? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(8):804-812.

39. Simons K, Connolly RP, Bonifas R, et al. Psychosocial assessment of nursing home residents via MDS 3.0: recommendations for social service training, staffing, and roles in interdisciplinary care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(2):190.e9-190.e15.

40. Alici Y. Interventions to improve recognition of delirium: a sine qua non for successful transitional care programs. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(1):80-82.

41. Judd RG, Sheffield S. Hospital social work: contemporary roles and professional activities. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49(9):856-871.

42. Duffy F, Healy JP. Social work with older people in a hospital setting. Soc Work Health Care. 2011;50(2):109-123.

43. Anderson CP, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Complications in post-acute care are associated with persistent delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(6):1122-1127.

44. Bauer M, Fitzgerald L, Haesler E, Manfrin M. Hospital discharge planning for frail older people and their family. Are we delivering best practice? A review of the evidence. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(18):2539-2546.

45. Shepperd S, Lannin NA, Clemson LM, McCluskey A, Cameron ID, Barras SL. Discharge planning from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD000313.

46. McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, Han L, Belzile E. The course of delirium in older medical inpatients: A prospective study. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(9):696-704.

47. Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM Jr. Nurses' recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467-2473.

48. Teodorczuk A, Reynish E, Milisen K. Improving recognition of delirium in clinical practice: a call for action. BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:55.

1. Rudolph JL, Boustani M, Kamholz B, Shaughnessey M, Shay K; American Delirium Society. Delirium: a strategic plan to bring an ancient disease into the 21st century. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S237-S240.

2. Hope C, Estrada N, Weir C, Teng CC, Damal K, Sauer BC. Documentation of delirium in the VA electronic health record. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:208.

3. van Zyl LT, Davidson PR. Delirium in hospital: an underreported event at discharge. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48(8):555-560.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. McCusker J, Cole M, Abrahamowicz M, Primeau F, Belzile E. Delirium predicts 12-month mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(4):457-463.

6. Inouye SK. Delirium in older persons. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1157-1165.

7. McCusker J, Cole M, Dendukuri N, Belzile E, Primeau F. Delirium in older medical inpatients and subsequent cognitive and functional status: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2001;165(5):575-583.

8. Quinlan N, Rudolph JL. Postoperative delirium and functional decline after noncardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S301-S304.

9. Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(21):3252-3257.

10. Marcantonio ER, Simon SE, Bergmann MA, Jones RN, Murphy KM, Morris JN. Delirium symptoms in post-acute care: prevalent, persistent, and associated with poor functional recovery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):4-9.

11. McNicoll L, Pisani MA, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):591-598.

12. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Delirium: Diagnosis, Prevention and Management. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Website. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg103/resources/delirium-174507018181. Published July 2010.

13. Fick D, Foreman M. Consequences of not recognizing delirium superimposed on dementia in hospitalized elderly individuals. J Gerontol Nurs. 2000;26(1):30-40.

14. Fick DM, Agostini JV, Inouye SK. Delirium superimposed on dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1723-1732.

15. Edlund A, Lundström M, Brännström B, Bucht G, Gustafson Y. Delirium before and after operation for femoral neck fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(10):1335-1340.

16. Popejoy LL, Galambos C, Moylan K, Madsen R. Challenges to hospital discharge planning for older adults. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21(4):431-449.

17. Marcantonio ER, Goldman L, Mangione CM, et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134-139.

18. Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Rasmussen LS, Silverstein JH, Inouye SK, Marcantonio ER. Independent vascular and cognitive risk factors for postoperative delirium. Am J Med. 2007;120(9):807-813.

19. Rudolph JL, Babikian VL, Birjiniuk V, et al. Atherosclerosis is associated with delirium after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(3):462-466.

20. Rudolph JL, Jones RN, Levkoff SE, et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(2):229-236.

21. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Profile of Veterans: 2013 Data from the American Community Survey. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Website. http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Veterans_2013.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2015.

22. Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, et al. The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(8):1271-1276.

23. McGuire JM. The incidence of and risk factors for emergence delirium in U.S. military combat veterans. J Perianesth Nurs. 2012;27(4):236-245.

24. Lepousé C, Lautner CA, Liu L, Gomis P, Leon A. Emergence delirium in adults in the post-anaesthesia care unit. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(6):747-753.

25. Meziab O, Kirby KA, Williams B, Yaffe K, Byers AL, Barnes DE. Prisoner of war status, posttraumatic stress disorder, and dementia in older veterans. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(3)(suppl):S236-S241.

26. Elie M, Cole MG, Primeau FJ, Bellavance F. Delirium risk factors in elderly hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(3):204-212.

27. Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elderly adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(4):210-220.

28. Conley DM. The gerontological clinical nurse specialist's role in prevention, early recognition, and management of delirium in hospitalized older adults. Urol Nurs. 2011;31(6):337-342.

29. Meagher DJ. Delirium: optimising management. BMJ. 2001;322(7279):144-149.

30. Irwin SA, Pirrello RD, Hirst JM, Buckholz GT, Ferris FD. Clarifying delirium management: practical, evidenced-based, expert recommendations for clinical practice. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(4):423-435.

31. Reston JT, Schoelles KM. In-facility delirium prevention programs as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5, pt 2):375-380.

32. Rudolph JL, Archambault E, Kelly B; VA Boston Delirium Task Force. A delirium risk modification program is associated with hospital outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):957.e7-957.e11.

33. Gustafson Y, Brännström B, Norberg A, Bucht G, Winblad B. Underdiagnosis and poor documentation of acute confusional states in elderly hip fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(8):760-765.

34. Hustey FM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(3):248-253.