User login

Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcome Trends of Acute Kidney Injury in Elective Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty

Degenerative arthritis is a widespread chronic condition with an incidence of almost 43 million and annual health care costs of $60 billion in the United States alone.1 Although many cases can be managed symptomatically with medical therapy and intra-articular injections,2 many patients experience disease progression resulting in decreased ambulatory ability and work productivity. For these patients, elective hip and knee arthroplasties can drastically improve quality of life and functionality.3,4 Over the past decade, there has been a marked increase in the number of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasties performed in the United States. By 2030, the demand for primary total hip arthroplasties will grow an estimated 174%, to 572,000 procedures. Likewise, the demand for primary total knee arthroplasties is projected to grow by 673%, to 3.48 million procedures.5 However, though better surgical techniques and technology have led to improved functional outcomes, there is still substantial risk for complications in the perioperative period, especially in the geriatric population, in which substantial comorbidities are common.6-9

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common public health problem in hospitalized patients and in patients undergoing procedures. More than one-third of all AKI cases occur in surgical settings.10,11 Over the past decade, both community-acquired and in-hospital AKIs rapidly increased in incidence in all major clinical settings.12-14 Patients with AKI have high rates of adverse outcomes during hospitalization and discharge.11,15 Sequelae of AKIs include worsening chronic kidney disease (CKD) and progression to end-stage renal disease, necessitating either long-term dialysis or transplantation.12 This in turn leads to exacerbated disability, diminished quality of life, and disproportionate burden on health care resources.

Much of our knowledge about postoperative AKI has been derived from cardiovascular, thoracic, and abdominal surgery settings. However, there is a paucity of data on epidemiology and trends for either AKI or associated outcomes in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. The few studies to date either were single-center or had inadequate sample sizes for appropriately powered analysis of the risk factors and outcomes related to AKI.16

In the study reported here, we analyzed a large cohort of patients from a nationwide multicenter database to determine the incidence of and risk factors for AKI. We also examined the mortality and adverse discharges associated with AKI after major joint surgery. Lastly, we assessed temporal trends in both incidence and outcomes of AKI, including the death risk attributable to AKI.

Methods

Database

We extracted our study cohort from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the National Inpatient Sample of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) compiled by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.17 NIS, the largest inpatient care database in the United States, stores data from almost 8 million stays in about 1000 hospitals across the country each year. Its participating hospital pool consists of about 20% of US community hospitals, resulting in a sampling frame comprising about 90% of all hospital discharges in the United States. This allows for calculation of precise, weighted nationwide estimates. Data elements within NIS are drawn from hospital discharge abstracts that indicate all procedures performed. NIS also stores information on patient characteristics, length of stay (LOS), discharge disposition, postoperative morbidity, and observed in-hospital mortality. However, it stores no information on long-term follow-up or complications after discharge.

Data Analysis

For the period 2002–2012, we queried the NIS database for hip and knee arthroplasties with primary diagnosis codes for osteoarthritis and secondary codes for AKI. We excluded patients under age 18 years and patients with diagnosis codes for hip and knee fracture/necrosis, inflammatory/infectious arthritis, or bone neoplasms (Table 1). We then extracted baseline characteristics of the study population. Patient-level characteristics included age, sex, race, quartile classification of median household income according to postal (ZIP) code, and primary payer (Medicare/Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, no charge). Hospital-level characteristics included hospital location (urban, rural), hospital bed size (small, medium, large), region (Northeast, Midwest/North Central, South, West), and teaching status. We defined illness severity and likelihood of death using Deyo’s modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which draws on principal and secondary ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification) diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and patient demographics to estimate a patient’s mortality risk. This method reliably predicts mortality and readmission in the orthopedic population.18,19 We assessed the effect of AKI on 4 outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, LOS, and cost of stay. Discharge disposition was grouped by either (a) home or short-term facility or (b) adverse discharge. Home or short-term facility covered routine, short-term hospital, against medical advice, home intravenous provider, another rehabilitation facility, another institution for outpatient services, institution for outpatient services, discharged alive, and destination unknown; adverse discharge covered skilled nursing facility, intermediate care, hospice home, hospice medical facility, long-term care hospital, and certified nursing facility. This dichotomization of discharge disposition is often used in studies of NIS data.20

Statistical Analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics of hospitalized patients with and without AKI. To test for significance, we used the χ2 test for categorical variables, the Student t test for normally distributed continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the Cochran-Armitage test for trends in AKI incidence. We used survey logistic regression models to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) in order to estimate the predictors of AKI and the impact of AKI on hospital outcomes. We constructed final models after adjusting for confounders, testing for potential interactions, and ensuring no multicolinearity between covariates. Last, we computed the risk proportion of death attributable to AKI, indicating the proportion of deaths that could potentially be avoided if AKI and its complications were abrogated.21

We performed all statistical analyses with SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute) using designated weight values to produce weighted national estimates. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .01 (with ORs and 95% CIs that excluded 1).

Results

AKI Incidence, Risk Factors, and Trends

We identified 7,235,251 patients who underwent elective hip or knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis between 2002 and 2012—an estimate consistent with data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.22 Of that total, 94,367 (1.3%) had AKI. The proportion of discharges diagnosed with AKI increased rapidly over the decade, from 0.5% in 2002 to 1.8% to 1.9% in the period 2010–2012. This upward trend was highly significant (Ptrend < .001) (Figure 1). Patients with AKI (vs patients without AKI) were more likely to be older (mean age, 70 vs 66 years; P < .001), male (50.8% vs 38.4%; P < .001), and black (10.07% vs 5.15%; P<. 001). They were also found to have a significantly higher comorbidity score (mean CCI, 2.8 vs 1.5; P < .001) and higher proportions of comorbidities, including hypertension, CKD, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus (DM), congestive heart failure, chronic liver disease, and hepatitis C virus infection. In addition, AKI was associated with perioperative myocardial infarction (MI), sepsis, cardiac catheterization, and blood transfusion. Regarding socioeconomic characteristics, patients with AKI were more likely to have Medicare/Medicaid insurance (72.26% vs 58.06%; P < .001) and to belong to the extremes of income categories (Table 2).

Using multivariable logistic regression, we found that increased age (1.11 increase in adjusted OR for every year older; 95% CI, 1.09-1.14; P < .001), male sex (adjusted OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.60-1.71; P < .001), and black race (adjusted OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.45-1.69; P < .001) were significantly associated with postoperative AKI. Regarding comorbidities, baseline CKD (adjusted OR, 8.64; 95% CI, 8.14-9.18; P < .001) and congestive heart failure (adjusted OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 2.57-2.92; P< .0001) were most significantly associated with AKI. Perioperative events, including sepsis (adjusted OR, 35.64; 95% CI, 30.28-41.96; P < .0001), MI (adjusted OR, 6.14; 95% CI, 5.17-7.28; P < .0001), and blood transfusion (adjusted OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 2.15-2.42; P < .0001), were also strongly associated with postoperative AKI. Last, compared with urban hospitals and small hospital bed size, rural hospitals (adjusted OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60-0.81; P< .001) and large bed size (adjusted OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.93; P = .003) were associated with lower probability of developing AKI (Table 3).

Figure 2 elucidates the frequency of AKI based on a combination of key preoperative comorbid conditions and postoperative complications—demonstrating that the proportion of AKI cases associated with other postoperative complications is significantly higher in the CKD and concomitant DM/CKD patient populations. Patients hospitalized with CKD exhibited higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (20.9% vs 1.8%; P < .001), acute MI (48.9% vs 13.8%; P < .001), and sepsis (74.7% vs 36.3%;P< .001) relative to patients without CKD. Similarly, patients with concomitant DM/CKD exhibited higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (23% vs 1.9%; P< .001), acute MI (51.1% vs 12.1%; P< .001), and sepsis (75% vs 38.2%; P < .001) relative to patients without either condition. However, patients hospitalized with DM alone exhibited only marginally higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (4.7% vs 2%; P < .01) and acute MI (19.2% vs 16.7%; P< .01) and a lower rate in cases involving sepsis (38.2% vs 41.7%; P < .01) relative to patients without DM. These data suggest that CKD is the most significant clinically relevant risk factor for AKI and that CKD may synergize with DM to raise the risk for AKI.

Outcomes

We then analyzed the impact of AKI on hospital outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, LOS, and cost of care. Mortality was significantly higher in patients with AKI than in patients without it (2.08% vs 0.06%; P < .001). Even after adjusting for confounders (eg, demographics, comorbidity burden, perioperative sepsis, hospital-level characteristics), AKI was still associated with strikingly higher odds of in-hospital death (adjusted OR, 11.32; 95% CI, 9.34-13.74; P < .001). However, analysis of temporal trends indicated that the odds for adjusted mortality associated with AKI decreased from 18.09 to 9.45 (Ptrend = .01) over the period 2002–2012 (Figure 3). This decrease in odds of death was countered by an increase in incidence of AKI, resulting in a stable attributable risk proportion (97.9% in 2002 to 97.3% in 2012; Ptrend = .90) (Table 4). Regarding discharge disposition, patients with AKI were much less likely to be discharged home (41.35% vs 62.59%; P < .001) and more likely to be discharged to long-term care (56.37% vs 37.03%; P< .001). After adjustment for confounders, AKI was associated with significantly increased odds of adverse discharge (adjusted OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 2.12-2.36; P< .001). Analysis of temporal trends revealed no appreciable decrease in the adjusted odds of adverse discharge between 2002 (adjusted OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.37-2.55; P < .001) and 2012 (adjusted OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.76-2.11; P < .001) (Figure 4, Table 5). Last, both mean LOS (5 days vs 3 days; P < .001) and mean cost of hospitalization (US $22,269 vs $15,757; P < .001) were significantly higher in patients with AKI.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the incidence of AKI among hospitalized patients increased 4-fold between 2002 and 2012. Moreover, we identified numerous patient-specific, hospital-specific, perioperative risk factors for AKI. Most important, we found that AKI was associated with a strikingly higher risk of in-hospital death, and surviving patients were more likely to experience adverse discharge. Although the adjusted mortality rate associated with AKI decreased over that decade, the attributable risk proportion remained stable.

Few studies have addressed this significant public health concern. In one recent study in Australia, Kimmel and colleagues16 identified risk factors for AKI but lacked data on AKI outcomes. In a study of complications and mortality occurring after orthopedic surgery, Belmont and colleagues22 categorized complications as either local or systemic but did not examine renal complications. Only 2 other major studies have been conducted on renal outcomes associated with major joint surgery, and both were limited to patients with acute hip fractures. The first included acute fracture surgery patients and omitted elective joint surgery patients, and it evaluated admission renal function but not postoperative AKI.22 The second study had a sample size of only 170 patients.23 Thus, the literature leaves us with a crucial knowledge gap in renal outcomes and their postoperative impact in elective arthroplasties.

The present study filled this information gap by examining the incidence, risk factors, outcomes, and temporal trends of AKI after elective hip and knee arthroplasties. The increasing incidence of AKI in this surgical setting is similar to that of AKI in other surgical settings (cardiac and noncardiac).21 Although our analysis was limited by lack of perioperative management data, patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty can experience kidney dysfunction for several reasons, including volume depletion, postoperative sepsis, and influence of medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially in older patients with more comorbidities and a higher burden of CKD. Each of these factors can cause renal dysfunction in patients having orthopedic procedures.24 Moreover, NSAID use among elective joint arthroplasty patients is likely higher because of an emphasis on multimodal analgesia, as recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of NSAID use in controlling pain without increasing bleeding.25-27 Our results also demonstrated that the absolute incidence of AKI after orthopedic surgery is relatively low. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the definitions used were based on ICD-9-CM codes that underestimate the true incidence of AKI.

Consistent with other studies, we found that certain key preoperative comorbid conditions and postoperative events were associated with higher AKI risk. We stratified the rate of AKI associated with each postoperative event (sepsis, acute MI, cardiac catheterization, need for transfusion) by DM/CKD comorbidity. CKD was associated with significantly higher AKI risk across all postoperative complications. This information may provide clinicians with bedside information that can be used to determine which patients may be at higher or lower risk for AKI.

Our analysis of patient outcomes revealed that, though AKI was relatively uncommon, it increased the risk for death during hospitalization more than 10-fold between 2002 and 2012. Although the adjusted OR of in-hospital mortality decreased over the decade studied, the concurrent increase in AKI incidence caused the attributable risk of death associated with AKI to essentially remain the same. This observation is consistent with recent reports from cardiac surgery settings.21 These data together suggest that ameliorating occurrences of AKI would decrease mortality and increase quality of care for patients undergoing elective joint surgeries.

We also examined the effect of AKI on resource use by studying LOS, costs, and risk for adverse discharge. Much as in other surgical settings, AKI increased both LOS and overall hospitalization costs. More important, AKI was associated with increased adverse discharge (discharge to long-term care or nursing homes). Although exact reasons are unclear, we can speculate that postoperative renal dysfunction precludes early rehabilitation, impeding desired functional outcome and disposition.28,29 Given the projected increases in primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasties,5 these data predict that the impact of AKI on health outcomes will increase alarmingly in coming years.

There are limitations to our study. First, it was based on administrative data and lacked patient-level and laboratory data. As reported, the sensitivity of AKI codes remains moderate,30 so the true burden may be higher than indicated here. As the definition of AKI was based on administrative coding, we also could not estimate severity, though previous studies have found that administrative codes typically capture a more severe form of disease.31 Another limitation is that, because the data were deidentified, we could not delineate the risk for recurrent AKI in repeated surgical procedures, though this cohort unlikely was large enough to qualitatively affect our results. The third limitation is that, though we used CCI to adjust for the comorbidity burden, we were unable to account for other unmeasured confounders associated with increased AKI incidence, such as specific medication use. In addition, given the lack of patient-level data, we could not analyze the specific factors responsible for AKI in the perioperative period. Nevertheless, the strengths of a nationally representative sample, such as large sample size and generalizability, outweigh these limitations.

Conclusion

AKI is potentially an important quality indicator of elective joint surgery, and reducing its incidence is therefore essential for quality improvement. Given that hip and knee arthroplasties are projected to increase exponentially, as is the burden of comorbid conditions in this population, postoperative AKI will continue to have an incremental impact on health and health care resources. Thus, a carefully planned approach of interdisciplinary perioperative care is warranted to reduce both the risk and the consequences of this devastating condition.

1. Reginster JY. The prevalence and burden of arthritis. Rheumatology. 2002;41(supp 1):3-6.

2. Kullenberg B, Runesson R, Tuvhag R, Olsson C, Resch S. Intraarticular corticosteroid injection: pain relief in osteoarthritis of the hip? J Rheumatol. 2004;31(11):2265-2268.

3. Kawasaki M, Hasegawa Y, Sakano S, Torii Y, Warashina H. Quality of life after several treatments for osteoarthritis of the hip. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(1):32-35.

4. Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(5):963-974.

5. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

6. Matlock D, Earnest M, Epstein A. Utilization of elective hip and knee arthroplasty by age and payer. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(4):914-919.

7. Parvizi J, Holiday AD, Ereth MH, Lewallen DG. The Frank Stinchfield Award. Sudden death during primary hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(369):39-48.

8. Parvizi J, Mui A, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total joint arthroplasty: when do fatal or near-fatal complications occur? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):27-32.

9. Parvizi J, Sullivan TA, Trousdale RT, Lewallen DG. Thirty-day mortality after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1157-1161.

10. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294(7):813-818.

11. Thakar CV. Perioperative acute kidney injury. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(1):67-75.

12. Hsu CY, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Go AS. Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(5):891-898.

13. Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury—epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(4):193-207.

14. Thakar CV, Worley S, Arrigain S, Yared JP, Paganini EP. Influence of renal dysfunction on mortality after cardiac surgery: modifying effect of preoperative renal function. Kidney Int. 2005;67(3):1112-1119.

15. Zeng X, McMahon GM, Brunelli SM, Bates DW, Waikar SS. Incidence, outcomes, and comparisons across definitions of AKI in hospitalized individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):12-20.

16. Kimmel LA, Wilson S, Janardan JD, Liew SM, Walker RG. Incidence of acute kidney injury following total joint arthroplasty: a retrospective review by RIFLE criteria. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(6):546-551.

17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) databases, 2002–2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

18. Bjorgul K, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ. Evaluating comorbidities in total hip and knee arthroplasty: available instruments. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(4):203-209.

19. Voskuijl T, Hageman M, Ring D. Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores are associated with readmission after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1638-1644.

20. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365-3370.

21. Lenihan CR, Montez-Rath ME, Mora Mangano CT, Chertow GM, Winkelmayer WC. Trends in acute kidney injury, associated use of dialysis, and mortality after cardiac surgery, 1999 to 2008. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(1):20-28.

22. Belmont PJ Jr, Goodman GP, Waterman BR, Bader JO, Schoenfeld AJ. Thirty-day postoperative complications and mortality following total knee arthroplasty: incidence and risk factors among a national sample of 15,321 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):20-26.

23. Bennet SJ, Berry OM, Goddard J, Keating JF. Acute renal dysfunction following hip fracture. Injury. 2010;41(4):335-338.

24. Kateros K, Doulgerakis C, Galanakos SP, Sakellariou VI, Papadakis SA, Macheras GA. Analysis of kidney dysfunction in orthopaedic patients. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:101.

25. Huang YM, Wang CM, Wang CT, Lin WP, Horng LC, Jiang CC. Perioperative celecoxib administration for pain management after total knee arthroplasty—a randomized, controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:77.

26. Kelley TC, Adams MJ, Mulliken BD, Dalury DF. Efficacy of multimodal perioperative analgesia protocol with periarticular medication injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1274-1277.

27. Lamplot JD, Wagner ER, Manning DW. Multimodal pain management in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):329-334.

28. Munin MC, Rudy TE, Glynn NW, Crossett LS, Rubash HE. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998;279(11):847-852.

29. Pua YH, Ong PH. Association of early ambulation with length of stay and costs in total knee arthroplasty: retrospective cohort study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(11):962-970.

30. Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, et al. Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(6):1688-1694.

31. Grams ME, Waikar SS, MacMahon B, Whelton S, Ballew SH, Coresh J. Performance and limitations of administrative data in the identification of AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(4):682-689.

Degenerative arthritis is a widespread chronic condition with an incidence of almost 43 million and annual health care costs of $60 billion in the United States alone.1 Although many cases can be managed symptomatically with medical therapy and intra-articular injections,2 many patients experience disease progression resulting in decreased ambulatory ability and work productivity. For these patients, elective hip and knee arthroplasties can drastically improve quality of life and functionality.3,4 Over the past decade, there has been a marked increase in the number of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasties performed in the United States. By 2030, the demand for primary total hip arthroplasties will grow an estimated 174%, to 572,000 procedures. Likewise, the demand for primary total knee arthroplasties is projected to grow by 673%, to 3.48 million procedures.5 However, though better surgical techniques and technology have led to improved functional outcomes, there is still substantial risk for complications in the perioperative period, especially in the geriatric population, in which substantial comorbidities are common.6-9

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common public health problem in hospitalized patients and in patients undergoing procedures. More than one-third of all AKI cases occur in surgical settings.10,11 Over the past decade, both community-acquired and in-hospital AKIs rapidly increased in incidence in all major clinical settings.12-14 Patients with AKI have high rates of adverse outcomes during hospitalization and discharge.11,15 Sequelae of AKIs include worsening chronic kidney disease (CKD) and progression to end-stage renal disease, necessitating either long-term dialysis or transplantation.12 This in turn leads to exacerbated disability, diminished quality of life, and disproportionate burden on health care resources.

Much of our knowledge about postoperative AKI has been derived from cardiovascular, thoracic, and abdominal surgery settings. However, there is a paucity of data on epidemiology and trends for either AKI or associated outcomes in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. The few studies to date either were single-center or had inadequate sample sizes for appropriately powered analysis of the risk factors and outcomes related to AKI.16

In the study reported here, we analyzed a large cohort of patients from a nationwide multicenter database to determine the incidence of and risk factors for AKI. We also examined the mortality and adverse discharges associated with AKI after major joint surgery. Lastly, we assessed temporal trends in both incidence and outcomes of AKI, including the death risk attributable to AKI.

Methods

Database

We extracted our study cohort from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the National Inpatient Sample of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) compiled by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.17 NIS, the largest inpatient care database in the United States, stores data from almost 8 million stays in about 1000 hospitals across the country each year. Its participating hospital pool consists of about 20% of US community hospitals, resulting in a sampling frame comprising about 90% of all hospital discharges in the United States. This allows for calculation of precise, weighted nationwide estimates. Data elements within NIS are drawn from hospital discharge abstracts that indicate all procedures performed. NIS also stores information on patient characteristics, length of stay (LOS), discharge disposition, postoperative morbidity, and observed in-hospital mortality. However, it stores no information on long-term follow-up or complications after discharge.

Data Analysis

For the period 2002–2012, we queried the NIS database for hip and knee arthroplasties with primary diagnosis codes for osteoarthritis and secondary codes for AKI. We excluded patients under age 18 years and patients with diagnosis codes for hip and knee fracture/necrosis, inflammatory/infectious arthritis, or bone neoplasms (Table 1). We then extracted baseline characteristics of the study population. Patient-level characteristics included age, sex, race, quartile classification of median household income according to postal (ZIP) code, and primary payer (Medicare/Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, no charge). Hospital-level characteristics included hospital location (urban, rural), hospital bed size (small, medium, large), region (Northeast, Midwest/North Central, South, West), and teaching status. We defined illness severity and likelihood of death using Deyo’s modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which draws on principal and secondary ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification) diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and patient demographics to estimate a patient’s mortality risk. This method reliably predicts mortality and readmission in the orthopedic population.18,19 We assessed the effect of AKI on 4 outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, LOS, and cost of stay. Discharge disposition was grouped by either (a) home or short-term facility or (b) adverse discharge. Home or short-term facility covered routine, short-term hospital, against medical advice, home intravenous provider, another rehabilitation facility, another institution for outpatient services, institution for outpatient services, discharged alive, and destination unknown; adverse discharge covered skilled nursing facility, intermediate care, hospice home, hospice medical facility, long-term care hospital, and certified nursing facility. This dichotomization of discharge disposition is often used in studies of NIS data.20

Statistical Analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics of hospitalized patients with and without AKI. To test for significance, we used the χ2 test for categorical variables, the Student t test for normally distributed continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the Cochran-Armitage test for trends in AKI incidence. We used survey logistic regression models to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) in order to estimate the predictors of AKI and the impact of AKI on hospital outcomes. We constructed final models after adjusting for confounders, testing for potential interactions, and ensuring no multicolinearity between covariates. Last, we computed the risk proportion of death attributable to AKI, indicating the proportion of deaths that could potentially be avoided if AKI and its complications were abrogated.21

We performed all statistical analyses with SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute) using designated weight values to produce weighted national estimates. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .01 (with ORs and 95% CIs that excluded 1).

Results

AKI Incidence, Risk Factors, and Trends

We identified 7,235,251 patients who underwent elective hip or knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis between 2002 and 2012—an estimate consistent with data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.22 Of that total, 94,367 (1.3%) had AKI. The proportion of discharges diagnosed with AKI increased rapidly over the decade, from 0.5% in 2002 to 1.8% to 1.9% in the period 2010–2012. This upward trend was highly significant (Ptrend < .001) (Figure 1). Patients with AKI (vs patients without AKI) were more likely to be older (mean age, 70 vs 66 years; P < .001), male (50.8% vs 38.4%; P < .001), and black (10.07% vs 5.15%; P<. 001). They were also found to have a significantly higher comorbidity score (mean CCI, 2.8 vs 1.5; P < .001) and higher proportions of comorbidities, including hypertension, CKD, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus (DM), congestive heart failure, chronic liver disease, and hepatitis C virus infection. In addition, AKI was associated with perioperative myocardial infarction (MI), sepsis, cardiac catheterization, and blood transfusion. Regarding socioeconomic characteristics, patients with AKI were more likely to have Medicare/Medicaid insurance (72.26% vs 58.06%; P < .001) and to belong to the extremes of income categories (Table 2).

Using multivariable logistic regression, we found that increased age (1.11 increase in adjusted OR for every year older; 95% CI, 1.09-1.14; P < .001), male sex (adjusted OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.60-1.71; P < .001), and black race (adjusted OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.45-1.69; P < .001) were significantly associated with postoperative AKI. Regarding comorbidities, baseline CKD (adjusted OR, 8.64; 95% CI, 8.14-9.18; P < .001) and congestive heart failure (adjusted OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 2.57-2.92; P< .0001) were most significantly associated with AKI. Perioperative events, including sepsis (adjusted OR, 35.64; 95% CI, 30.28-41.96; P < .0001), MI (adjusted OR, 6.14; 95% CI, 5.17-7.28; P < .0001), and blood transfusion (adjusted OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 2.15-2.42; P < .0001), were also strongly associated with postoperative AKI. Last, compared with urban hospitals and small hospital bed size, rural hospitals (adjusted OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60-0.81; P< .001) and large bed size (adjusted OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.93; P = .003) were associated with lower probability of developing AKI (Table 3).

Figure 2 elucidates the frequency of AKI based on a combination of key preoperative comorbid conditions and postoperative complications—demonstrating that the proportion of AKI cases associated with other postoperative complications is significantly higher in the CKD and concomitant DM/CKD patient populations. Patients hospitalized with CKD exhibited higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (20.9% vs 1.8%; P < .001), acute MI (48.9% vs 13.8%; P < .001), and sepsis (74.7% vs 36.3%;P< .001) relative to patients without CKD. Similarly, patients with concomitant DM/CKD exhibited higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (23% vs 1.9%; P< .001), acute MI (51.1% vs 12.1%; P< .001), and sepsis (75% vs 38.2%; P < .001) relative to patients without either condition. However, patients hospitalized with DM alone exhibited only marginally higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (4.7% vs 2%; P < .01) and acute MI (19.2% vs 16.7%; P< .01) and a lower rate in cases involving sepsis (38.2% vs 41.7%; P < .01) relative to patients without DM. These data suggest that CKD is the most significant clinically relevant risk factor for AKI and that CKD may synergize with DM to raise the risk for AKI.

Outcomes

We then analyzed the impact of AKI on hospital outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, LOS, and cost of care. Mortality was significantly higher in patients with AKI than in patients without it (2.08% vs 0.06%; P < .001). Even after adjusting for confounders (eg, demographics, comorbidity burden, perioperative sepsis, hospital-level characteristics), AKI was still associated with strikingly higher odds of in-hospital death (adjusted OR, 11.32; 95% CI, 9.34-13.74; P < .001). However, analysis of temporal trends indicated that the odds for adjusted mortality associated with AKI decreased from 18.09 to 9.45 (Ptrend = .01) over the period 2002–2012 (Figure 3). This decrease in odds of death was countered by an increase in incidence of AKI, resulting in a stable attributable risk proportion (97.9% in 2002 to 97.3% in 2012; Ptrend = .90) (Table 4). Regarding discharge disposition, patients with AKI were much less likely to be discharged home (41.35% vs 62.59%; P < .001) and more likely to be discharged to long-term care (56.37% vs 37.03%; P< .001). After adjustment for confounders, AKI was associated with significantly increased odds of adverse discharge (adjusted OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 2.12-2.36; P< .001). Analysis of temporal trends revealed no appreciable decrease in the adjusted odds of adverse discharge between 2002 (adjusted OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.37-2.55; P < .001) and 2012 (adjusted OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.76-2.11; P < .001) (Figure 4, Table 5). Last, both mean LOS (5 days vs 3 days; P < .001) and mean cost of hospitalization (US $22,269 vs $15,757; P < .001) were significantly higher in patients with AKI.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the incidence of AKI among hospitalized patients increased 4-fold between 2002 and 2012. Moreover, we identified numerous patient-specific, hospital-specific, perioperative risk factors for AKI. Most important, we found that AKI was associated with a strikingly higher risk of in-hospital death, and surviving patients were more likely to experience adverse discharge. Although the adjusted mortality rate associated with AKI decreased over that decade, the attributable risk proportion remained stable.

Few studies have addressed this significant public health concern. In one recent study in Australia, Kimmel and colleagues16 identified risk factors for AKI but lacked data on AKI outcomes. In a study of complications and mortality occurring after orthopedic surgery, Belmont and colleagues22 categorized complications as either local or systemic but did not examine renal complications. Only 2 other major studies have been conducted on renal outcomes associated with major joint surgery, and both were limited to patients with acute hip fractures. The first included acute fracture surgery patients and omitted elective joint surgery patients, and it evaluated admission renal function but not postoperative AKI.22 The second study had a sample size of only 170 patients.23 Thus, the literature leaves us with a crucial knowledge gap in renal outcomes and their postoperative impact in elective arthroplasties.

The present study filled this information gap by examining the incidence, risk factors, outcomes, and temporal trends of AKI after elective hip and knee arthroplasties. The increasing incidence of AKI in this surgical setting is similar to that of AKI in other surgical settings (cardiac and noncardiac).21 Although our analysis was limited by lack of perioperative management data, patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty can experience kidney dysfunction for several reasons, including volume depletion, postoperative sepsis, and influence of medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially in older patients with more comorbidities and a higher burden of CKD. Each of these factors can cause renal dysfunction in patients having orthopedic procedures.24 Moreover, NSAID use among elective joint arthroplasty patients is likely higher because of an emphasis on multimodal analgesia, as recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of NSAID use in controlling pain without increasing bleeding.25-27 Our results also demonstrated that the absolute incidence of AKI after orthopedic surgery is relatively low. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the definitions used were based on ICD-9-CM codes that underestimate the true incidence of AKI.

Consistent with other studies, we found that certain key preoperative comorbid conditions and postoperative events were associated with higher AKI risk. We stratified the rate of AKI associated with each postoperative event (sepsis, acute MI, cardiac catheterization, need for transfusion) by DM/CKD comorbidity. CKD was associated with significantly higher AKI risk across all postoperative complications. This information may provide clinicians with bedside information that can be used to determine which patients may be at higher or lower risk for AKI.

Our analysis of patient outcomes revealed that, though AKI was relatively uncommon, it increased the risk for death during hospitalization more than 10-fold between 2002 and 2012. Although the adjusted OR of in-hospital mortality decreased over the decade studied, the concurrent increase in AKI incidence caused the attributable risk of death associated with AKI to essentially remain the same. This observation is consistent with recent reports from cardiac surgery settings.21 These data together suggest that ameliorating occurrences of AKI would decrease mortality and increase quality of care for patients undergoing elective joint surgeries.

We also examined the effect of AKI on resource use by studying LOS, costs, and risk for adverse discharge. Much as in other surgical settings, AKI increased both LOS and overall hospitalization costs. More important, AKI was associated with increased adverse discharge (discharge to long-term care or nursing homes). Although exact reasons are unclear, we can speculate that postoperative renal dysfunction precludes early rehabilitation, impeding desired functional outcome and disposition.28,29 Given the projected increases in primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasties,5 these data predict that the impact of AKI on health outcomes will increase alarmingly in coming years.

There are limitations to our study. First, it was based on administrative data and lacked patient-level and laboratory data. As reported, the sensitivity of AKI codes remains moderate,30 so the true burden may be higher than indicated here. As the definition of AKI was based on administrative coding, we also could not estimate severity, though previous studies have found that administrative codes typically capture a more severe form of disease.31 Another limitation is that, because the data were deidentified, we could not delineate the risk for recurrent AKI in repeated surgical procedures, though this cohort unlikely was large enough to qualitatively affect our results. The third limitation is that, though we used CCI to adjust for the comorbidity burden, we were unable to account for other unmeasured confounders associated with increased AKI incidence, such as specific medication use. In addition, given the lack of patient-level data, we could not analyze the specific factors responsible for AKI in the perioperative period. Nevertheless, the strengths of a nationally representative sample, such as large sample size and generalizability, outweigh these limitations.

Conclusion

AKI is potentially an important quality indicator of elective joint surgery, and reducing its incidence is therefore essential for quality improvement. Given that hip and knee arthroplasties are projected to increase exponentially, as is the burden of comorbid conditions in this population, postoperative AKI will continue to have an incremental impact on health and health care resources. Thus, a carefully planned approach of interdisciplinary perioperative care is warranted to reduce both the risk and the consequences of this devastating condition.

Degenerative arthritis is a widespread chronic condition with an incidence of almost 43 million and annual health care costs of $60 billion in the United States alone.1 Although many cases can be managed symptomatically with medical therapy and intra-articular injections,2 many patients experience disease progression resulting in decreased ambulatory ability and work productivity. For these patients, elective hip and knee arthroplasties can drastically improve quality of life and functionality.3,4 Over the past decade, there has been a marked increase in the number of primary and revision total hip and knee arthroplasties performed in the United States. By 2030, the demand for primary total hip arthroplasties will grow an estimated 174%, to 572,000 procedures. Likewise, the demand for primary total knee arthroplasties is projected to grow by 673%, to 3.48 million procedures.5 However, though better surgical techniques and technology have led to improved functional outcomes, there is still substantial risk for complications in the perioperative period, especially in the geriatric population, in which substantial comorbidities are common.6-9

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common public health problem in hospitalized patients and in patients undergoing procedures. More than one-third of all AKI cases occur in surgical settings.10,11 Over the past decade, both community-acquired and in-hospital AKIs rapidly increased in incidence in all major clinical settings.12-14 Patients with AKI have high rates of adverse outcomes during hospitalization and discharge.11,15 Sequelae of AKIs include worsening chronic kidney disease (CKD) and progression to end-stage renal disease, necessitating either long-term dialysis or transplantation.12 This in turn leads to exacerbated disability, diminished quality of life, and disproportionate burden on health care resources.

Much of our knowledge about postoperative AKI has been derived from cardiovascular, thoracic, and abdominal surgery settings. However, there is a paucity of data on epidemiology and trends for either AKI or associated outcomes in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. The few studies to date either were single-center or had inadequate sample sizes for appropriately powered analysis of the risk factors and outcomes related to AKI.16

In the study reported here, we analyzed a large cohort of patients from a nationwide multicenter database to determine the incidence of and risk factors for AKI. We also examined the mortality and adverse discharges associated with AKI after major joint surgery. Lastly, we assessed temporal trends in both incidence and outcomes of AKI, including the death risk attributable to AKI.

Methods

Database

We extracted our study cohort from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) and the National Inpatient Sample of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) compiled by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.17 NIS, the largest inpatient care database in the United States, stores data from almost 8 million stays in about 1000 hospitals across the country each year. Its participating hospital pool consists of about 20% of US community hospitals, resulting in a sampling frame comprising about 90% of all hospital discharges in the United States. This allows for calculation of precise, weighted nationwide estimates. Data elements within NIS are drawn from hospital discharge abstracts that indicate all procedures performed. NIS also stores information on patient characteristics, length of stay (LOS), discharge disposition, postoperative morbidity, and observed in-hospital mortality. However, it stores no information on long-term follow-up or complications after discharge.

Data Analysis

For the period 2002–2012, we queried the NIS database for hip and knee arthroplasties with primary diagnosis codes for osteoarthritis and secondary codes for AKI. We excluded patients under age 18 years and patients with diagnosis codes for hip and knee fracture/necrosis, inflammatory/infectious arthritis, or bone neoplasms (Table 1). We then extracted baseline characteristics of the study population. Patient-level characteristics included age, sex, race, quartile classification of median household income according to postal (ZIP) code, and primary payer (Medicare/Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, no charge). Hospital-level characteristics included hospital location (urban, rural), hospital bed size (small, medium, large), region (Northeast, Midwest/North Central, South, West), and teaching status. We defined illness severity and likelihood of death using Deyo’s modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which draws on principal and secondary ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification) diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and patient demographics to estimate a patient’s mortality risk. This method reliably predicts mortality and readmission in the orthopedic population.18,19 We assessed the effect of AKI on 4 outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, LOS, and cost of stay. Discharge disposition was grouped by either (a) home or short-term facility or (b) adverse discharge. Home or short-term facility covered routine, short-term hospital, against medical advice, home intravenous provider, another rehabilitation facility, another institution for outpatient services, institution for outpatient services, discharged alive, and destination unknown; adverse discharge covered skilled nursing facility, intermediate care, hospice home, hospice medical facility, long-term care hospital, and certified nursing facility. This dichotomization of discharge disposition is often used in studies of NIS data.20

Statistical Analyses

We compared the baseline characteristics of hospitalized patients with and without AKI. To test for significance, we used the χ2 test for categorical variables, the Student t test for normally distributed continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the Cochran-Armitage test for trends in AKI incidence. We used survey logistic regression models to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) in order to estimate the predictors of AKI and the impact of AKI on hospital outcomes. We constructed final models after adjusting for confounders, testing for potential interactions, and ensuring no multicolinearity between covariates. Last, we computed the risk proportion of death attributable to AKI, indicating the proportion of deaths that could potentially be avoided if AKI and its complications were abrogated.21

We performed all statistical analyses with SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute) using designated weight values to produce weighted national estimates. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .01 (with ORs and 95% CIs that excluded 1).

Results

AKI Incidence, Risk Factors, and Trends

We identified 7,235,251 patients who underwent elective hip or knee arthroplasty for osteoarthritis between 2002 and 2012—an estimate consistent with data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.22 Of that total, 94,367 (1.3%) had AKI. The proportion of discharges diagnosed with AKI increased rapidly over the decade, from 0.5% in 2002 to 1.8% to 1.9% in the period 2010–2012. This upward trend was highly significant (Ptrend < .001) (Figure 1). Patients with AKI (vs patients without AKI) were more likely to be older (mean age, 70 vs 66 years; P < .001), male (50.8% vs 38.4%; P < .001), and black (10.07% vs 5.15%; P<. 001). They were also found to have a significantly higher comorbidity score (mean CCI, 2.8 vs 1.5; P < .001) and higher proportions of comorbidities, including hypertension, CKD, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus (DM), congestive heart failure, chronic liver disease, and hepatitis C virus infection. In addition, AKI was associated with perioperative myocardial infarction (MI), sepsis, cardiac catheterization, and blood transfusion. Regarding socioeconomic characteristics, patients with AKI were more likely to have Medicare/Medicaid insurance (72.26% vs 58.06%; P < .001) and to belong to the extremes of income categories (Table 2).

Using multivariable logistic regression, we found that increased age (1.11 increase in adjusted OR for every year older; 95% CI, 1.09-1.14; P < .001), male sex (adjusted OR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.60-1.71; P < .001), and black race (adjusted OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.45-1.69; P < .001) were significantly associated with postoperative AKI. Regarding comorbidities, baseline CKD (adjusted OR, 8.64; 95% CI, 8.14-9.18; P < .001) and congestive heart failure (adjusted OR, 2.74; 95% CI, 2.57-2.92; P< .0001) were most significantly associated with AKI. Perioperative events, including sepsis (adjusted OR, 35.64; 95% CI, 30.28-41.96; P < .0001), MI (adjusted OR, 6.14; 95% CI, 5.17-7.28; P < .0001), and blood transfusion (adjusted OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 2.15-2.42; P < .0001), were also strongly associated with postoperative AKI. Last, compared with urban hospitals and small hospital bed size, rural hospitals (adjusted OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.60-0.81; P< .001) and large bed size (adjusted OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.93; P = .003) were associated with lower probability of developing AKI (Table 3).

Figure 2 elucidates the frequency of AKI based on a combination of key preoperative comorbid conditions and postoperative complications—demonstrating that the proportion of AKI cases associated with other postoperative complications is significantly higher in the CKD and concomitant DM/CKD patient populations. Patients hospitalized with CKD exhibited higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (20.9% vs 1.8%; P < .001), acute MI (48.9% vs 13.8%; P < .001), and sepsis (74.7% vs 36.3%;P< .001) relative to patients without CKD. Similarly, patients with concomitant DM/CKD exhibited higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (23% vs 1.9%; P< .001), acute MI (51.1% vs 12.1%; P< .001), and sepsis (75% vs 38.2%; P < .001) relative to patients without either condition. However, patients hospitalized with DM alone exhibited only marginally higher rates of AKI in cases involving blood transfusion (4.7% vs 2%; P < .01) and acute MI (19.2% vs 16.7%; P< .01) and a lower rate in cases involving sepsis (38.2% vs 41.7%; P < .01) relative to patients without DM. These data suggest that CKD is the most significant clinically relevant risk factor for AKI and that CKD may synergize with DM to raise the risk for AKI.

Outcomes

We then analyzed the impact of AKI on hospital outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, discharge disposition, LOS, and cost of care. Mortality was significantly higher in patients with AKI than in patients without it (2.08% vs 0.06%; P < .001). Even after adjusting for confounders (eg, demographics, comorbidity burden, perioperative sepsis, hospital-level characteristics), AKI was still associated with strikingly higher odds of in-hospital death (adjusted OR, 11.32; 95% CI, 9.34-13.74; P < .001). However, analysis of temporal trends indicated that the odds for adjusted mortality associated with AKI decreased from 18.09 to 9.45 (Ptrend = .01) over the period 2002–2012 (Figure 3). This decrease in odds of death was countered by an increase in incidence of AKI, resulting in a stable attributable risk proportion (97.9% in 2002 to 97.3% in 2012; Ptrend = .90) (Table 4). Regarding discharge disposition, patients with AKI were much less likely to be discharged home (41.35% vs 62.59%; P < .001) and more likely to be discharged to long-term care (56.37% vs 37.03%; P< .001). After adjustment for confounders, AKI was associated with significantly increased odds of adverse discharge (adjusted OR, 2.24; 95% CI, 2.12-2.36; P< .001). Analysis of temporal trends revealed no appreciable decrease in the adjusted odds of adverse discharge between 2002 (adjusted OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.37-2.55; P < .001) and 2012 (adjusted OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.76-2.11; P < .001) (Figure 4, Table 5). Last, both mean LOS (5 days vs 3 days; P < .001) and mean cost of hospitalization (US $22,269 vs $15,757; P < .001) were significantly higher in patients with AKI.

Discussion

In this study, we found that the incidence of AKI among hospitalized patients increased 4-fold between 2002 and 2012. Moreover, we identified numerous patient-specific, hospital-specific, perioperative risk factors for AKI. Most important, we found that AKI was associated with a strikingly higher risk of in-hospital death, and surviving patients were more likely to experience adverse discharge. Although the adjusted mortality rate associated with AKI decreased over that decade, the attributable risk proportion remained stable.

Few studies have addressed this significant public health concern. In one recent study in Australia, Kimmel and colleagues16 identified risk factors for AKI but lacked data on AKI outcomes. In a study of complications and mortality occurring after orthopedic surgery, Belmont and colleagues22 categorized complications as either local or systemic but did not examine renal complications. Only 2 other major studies have been conducted on renal outcomes associated with major joint surgery, and both were limited to patients with acute hip fractures. The first included acute fracture surgery patients and omitted elective joint surgery patients, and it evaluated admission renal function but not postoperative AKI.22 The second study had a sample size of only 170 patients.23 Thus, the literature leaves us with a crucial knowledge gap in renal outcomes and their postoperative impact in elective arthroplasties.

The present study filled this information gap by examining the incidence, risk factors, outcomes, and temporal trends of AKI after elective hip and knee arthroplasties. The increasing incidence of AKI in this surgical setting is similar to that of AKI in other surgical settings (cardiac and noncardiac).21 Although our analysis was limited by lack of perioperative management data, patients undergoing elective joint arthroplasty can experience kidney dysfunction for several reasons, including volume depletion, postoperative sepsis, and influence of medications, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), especially in older patients with more comorbidities and a higher burden of CKD. Each of these factors can cause renal dysfunction in patients having orthopedic procedures.24 Moreover, NSAID use among elective joint arthroplasty patients is likely higher because of an emphasis on multimodal analgesia, as recent randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of NSAID use in controlling pain without increasing bleeding.25-27 Our results also demonstrated that the absolute incidence of AKI after orthopedic surgery is relatively low. One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that the definitions used were based on ICD-9-CM codes that underestimate the true incidence of AKI.

Consistent with other studies, we found that certain key preoperative comorbid conditions and postoperative events were associated with higher AKI risk. We stratified the rate of AKI associated with each postoperative event (sepsis, acute MI, cardiac catheterization, need for transfusion) by DM/CKD comorbidity. CKD was associated with significantly higher AKI risk across all postoperative complications. This information may provide clinicians with bedside information that can be used to determine which patients may be at higher or lower risk for AKI.

Our analysis of patient outcomes revealed that, though AKI was relatively uncommon, it increased the risk for death during hospitalization more than 10-fold between 2002 and 2012. Although the adjusted OR of in-hospital mortality decreased over the decade studied, the concurrent increase in AKI incidence caused the attributable risk of death associated with AKI to essentially remain the same. This observation is consistent with recent reports from cardiac surgery settings.21 These data together suggest that ameliorating occurrences of AKI would decrease mortality and increase quality of care for patients undergoing elective joint surgeries.

We also examined the effect of AKI on resource use by studying LOS, costs, and risk for adverse discharge. Much as in other surgical settings, AKI increased both LOS and overall hospitalization costs. More important, AKI was associated with increased adverse discharge (discharge to long-term care or nursing homes). Although exact reasons are unclear, we can speculate that postoperative renal dysfunction precludes early rehabilitation, impeding desired functional outcome and disposition.28,29 Given the projected increases in primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasties,5 these data predict that the impact of AKI on health outcomes will increase alarmingly in coming years.

There are limitations to our study. First, it was based on administrative data and lacked patient-level and laboratory data. As reported, the sensitivity of AKI codes remains moderate,30 so the true burden may be higher than indicated here. As the definition of AKI was based on administrative coding, we also could not estimate severity, though previous studies have found that administrative codes typically capture a more severe form of disease.31 Another limitation is that, because the data were deidentified, we could not delineate the risk for recurrent AKI in repeated surgical procedures, though this cohort unlikely was large enough to qualitatively affect our results. The third limitation is that, though we used CCI to adjust for the comorbidity burden, we were unable to account for other unmeasured confounders associated with increased AKI incidence, such as specific medication use. In addition, given the lack of patient-level data, we could not analyze the specific factors responsible for AKI in the perioperative period. Nevertheless, the strengths of a nationally representative sample, such as large sample size and generalizability, outweigh these limitations.

Conclusion

AKI is potentially an important quality indicator of elective joint surgery, and reducing its incidence is therefore essential for quality improvement. Given that hip and knee arthroplasties are projected to increase exponentially, as is the burden of comorbid conditions in this population, postoperative AKI will continue to have an incremental impact on health and health care resources. Thus, a carefully planned approach of interdisciplinary perioperative care is warranted to reduce both the risk and the consequences of this devastating condition.

1. Reginster JY. The prevalence and burden of arthritis. Rheumatology. 2002;41(supp 1):3-6.

2. Kullenberg B, Runesson R, Tuvhag R, Olsson C, Resch S. Intraarticular corticosteroid injection: pain relief in osteoarthritis of the hip? J Rheumatol. 2004;31(11):2265-2268.

3. Kawasaki M, Hasegawa Y, Sakano S, Torii Y, Warashina H. Quality of life after several treatments for osteoarthritis of the hip. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(1):32-35.

4. Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(5):963-974.

5. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

6. Matlock D, Earnest M, Epstein A. Utilization of elective hip and knee arthroplasty by age and payer. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(4):914-919.

7. Parvizi J, Holiday AD, Ereth MH, Lewallen DG. The Frank Stinchfield Award. Sudden death during primary hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(369):39-48.

8. Parvizi J, Mui A, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total joint arthroplasty: when do fatal or near-fatal complications occur? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):27-32.

9. Parvizi J, Sullivan TA, Trousdale RT, Lewallen DG. Thirty-day mortality after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1157-1161.

10. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294(7):813-818.

11. Thakar CV. Perioperative acute kidney injury. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(1):67-75.

12. Hsu CY, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Go AS. Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(5):891-898.

13. Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury—epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(4):193-207.

14. Thakar CV, Worley S, Arrigain S, Yared JP, Paganini EP. Influence of renal dysfunction on mortality after cardiac surgery: modifying effect of preoperative renal function. Kidney Int. 2005;67(3):1112-1119.

15. Zeng X, McMahon GM, Brunelli SM, Bates DW, Waikar SS. Incidence, outcomes, and comparisons across definitions of AKI in hospitalized individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):12-20.

16. Kimmel LA, Wilson S, Janardan JD, Liew SM, Walker RG. Incidence of acute kidney injury following total joint arthroplasty: a retrospective review by RIFLE criteria. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(6):546-551.

17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) databases, 2002–2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

18. Bjorgul K, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ. Evaluating comorbidities in total hip and knee arthroplasty: available instruments. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(4):203-209.

19. Voskuijl T, Hageman M, Ring D. Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores are associated with readmission after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1638-1644.

20. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365-3370.

21. Lenihan CR, Montez-Rath ME, Mora Mangano CT, Chertow GM, Winkelmayer WC. Trends in acute kidney injury, associated use of dialysis, and mortality after cardiac surgery, 1999 to 2008. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(1):20-28.

22. Belmont PJ Jr, Goodman GP, Waterman BR, Bader JO, Schoenfeld AJ. Thirty-day postoperative complications and mortality following total knee arthroplasty: incidence and risk factors among a national sample of 15,321 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):20-26.

23. Bennet SJ, Berry OM, Goddard J, Keating JF. Acute renal dysfunction following hip fracture. Injury. 2010;41(4):335-338.

24. Kateros K, Doulgerakis C, Galanakos SP, Sakellariou VI, Papadakis SA, Macheras GA. Analysis of kidney dysfunction in orthopaedic patients. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:101.

25. Huang YM, Wang CM, Wang CT, Lin WP, Horng LC, Jiang CC. Perioperative celecoxib administration for pain management after total knee arthroplasty—a randomized, controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:77.

26. Kelley TC, Adams MJ, Mulliken BD, Dalury DF. Efficacy of multimodal perioperative analgesia protocol with periarticular medication injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1274-1277.

27. Lamplot JD, Wagner ER, Manning DW. Multimodal pain management in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):329-334.

28. Munin MC, Rudy TE, Glynn NW, Crossett LS, Rubash HE. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998;279(11):847-852.

29. Pua YH, Ong PH. Association of early ambulation with length of stay and costs in total knee arthroplasty: retrospective cohort study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(11):962-970.

30. Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, et al. Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(6):1688-1694.

31. Grams ME, Waikar SS, MacMahon B, Whelton S, Ballew SH, Coresh J. Performance and limitations of administrative data in the identification of AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(4):682-689.

1. Reginster JY. The prevalence and burden of arthritis. Rheumatology. 2002;41(supp 1):3-6.

2. Kullenberg B, Runesson R, Tuvhag R, Olsson C, Resch S. Intraarticular corticosteroid injection: pain relief in osteoarthritis of the hip? J Rheumatol. 2004;31(11):2265-2268.

3. Kawasaki M, Hasegawa Y, Sakano S, Torii Y, Warashina H. Quality of life after several treatments for osteoarthritis of the hip. J Orthop Sci. 2003;8(1):32-35.

4. Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86(5):963-974.

5. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785.

6. Matlock D, Earnest M, Epstein A. Utilization of elective hip and knee arthroplasty by age and payer. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(4):914-919.

7. Parvizi J, Holiday AD, Ereth MH, Lewallen DG. The Frank Stinchfield Award. Sudden death during primary hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(369):39-48.

8. Parvizi J, Mui A, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total joint arthroplasty: when do fatal or near-fatal complications occur? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):27-32.

9. Parvizi J, Sullivan TA, Trousdale RT, Lewallen DG. Thirty-day mortality after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(8):1157-1161.

10. Uchino S, Kellum JA, Bellomo R, et al; Beginning and Ending Supportive Therapy for the Kidney (BEST Kidney) Investigators. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294(7):813-818.

11. Thakar CV. Perioperative acute kidney injury. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(1):67-75.

12. Hsu CY, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Go AS. Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(5):891-898.

13. Rewa O, Bagshaw SM. Acute kidney injury—epidemiology, outcomes and economics. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(4):193-207.

14. Thakar CV, Worley S, Arrigain S, Yared JP, Paganini EP. Influence of renal dysfunction on mortality after cardiac surgery: modifying effect of preoperative renal function. Kidney Int. 2005;67(3):1112-1119.

15. Zeng X, McMahon GM, Brunelli SM, Bates DW, Waikar SS. Incidence, outcomes, and comparisons across definitions of AKI in hospitalized individuals. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):12-20.

16. Kimmel LA, Wilson S, Janardan JD, Liew SM, Walker RG. Incidence of acute kidney injury following total joint arthroplasty: a retrospective review by RIFLE criteria. Clin Kidney J. 2014;7(6):546-551.

17. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) databases, 2002–2012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

18. Bjorgul K, Novicoff WM, Saleh KJ. Evaluating comorbidities in total hip and knee arthroplasty: available instruments. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(4):203-209.

19. Voskuijl T, Hageman M, Ring D. Higher Charlson Comorbidity Index Scores are associated with readmission after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(5):1638-1644.

20. Chertow GM, Burdick E, Honour M, Bonventre JV, Bates DW. Acute kidney injury, mortality, length of stay, and costs in hospitalized patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(11):3365-3370.

21. Lenihan CR, Montez-Rath ME, Mora Mangano CT, Chertow GM, Winkelmayer WC. Trends in acute kidney injury, associated use of dialysis, and mortality after cardiac surgery, 1999 to 2008. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95(1):20-28.

22. Belmont PJ Jr, Goodman GP, Waterman BR, Bader JO, Schoenfeld AJ. Thirty-day postoperative complications and mortality following total knee arthroplasty: incidence and risk factors among a national sample of 15,321 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(1):20-26.

23. Bennet SJ, Berry OM, Goddard J, Keating JF. Acute renal dysfunction following hip fracture. Injury. 2010;41(4):335-338.

24. Kateros K, Doulgerakis C, Galanakos SP, Sakellariou VI, Papadakis SA, Macheras GA. Analysis of kidney dysfunction in orthopaedic patients. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:101.

25. Huang YM, Wang CM, Wang CT, Lin WP, Horng LC, Jiang CC. Perioperative celecoxib administration for pain management after total knee arthroplasty—a randomized, controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:77.

26. Kelley TC, Adams MJ, Mulliken BD, Dalury DF. Efficacy of multimodal perioperative analgesia protocol with periarticular medication injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1274-1277.

27. Lamplot JD, Wagner ER, Manning DW. Multimodal pain management in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(2):329-334.

28. Munin MC, Rudy TE, Glynn NW, Crossett LS, Rubash HE. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998;279(11):847-852.

29. Pua YH, Ong PH. Association of early ambulation with length of stay and costs in total knee arthroplasty: retrospective cohort study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;93(11):962-970.

30. Waikar SS, Wald R, Chertow GM, et al. Validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(6):1688-1694.

31. Grams ME, Waikar SS, MacMahon B, Whelton S, Ballew SH, Coresh J. Performance and limitations of administrative data in the identification of AKI. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(4):682-689.

Analysis of Direct Costs of Outpatient Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

Musculoskeletal disorders, the leading cause of disability in the United States,1 account for more than half of all persons reporting missing a workday because of a medical condition.2 Shoulder disorders in particular play a significant role in the burden of musculoskeletal disorders and cost of care. In 2008, 18.9 million adults (8.2% of the US adult population) reported chronic shoulder pain.1 Among shoulder disorders, rotator cuff pathology is the most common cause of shoulder-related disability found by orthopedic surgeons.3 Rotator cuff surgery (RCS) is one of the most commonly performed orthopedic surgical procedures, and surgery volume is on the rise. One study found a 141% increase in rotator cuff repairs between the years 1996 (~41 per 100,000 population) and 2006 (~98 per 100,000 population).4

US health care costs are also increasing. In 2011, $2.7 trillion was spent on health care, representing 17.9% of the national gross domestic product (GDP). According to projections, costs will rise to $4.6 trillion by 2020.5 In particular, as patients continue to live longer and remain more active into their later years, the costs of treating and managing musculoskeletal disorders become more important from a public policy standpoint. In 2006, the cost of treating musculoskeletal disorders alone was $576 billion, representing 4.5% of that year’s GDP.2

Paramount in this era of rising costs is the idea of maximizing the value of health care dollars. Health care economists Porter and Teisberg6 defined value as patient health outcomes achieved per dollar of cost expended in a care cycle (diagnosis, treatment, ongoing management) for a particular disease or disorder. For proper management of value, outcomes and costs for an entire cycle of care must be determined. From a practical standpoint, this first requires determining the true cost of a care cycle—dollars spent on personnel, equipment, materials, and other resources required to deliver a particular service—rather than the amount charged or reimbursed for providing the service in question.7

Kaplan and Anderson8,9 described the TDABC (time-driven activity-based costing) algorithm for calculating the cost of delivering a service based on 2 parameters: unit cost of a particular resource, and time required to supply it. These parameters apply to material costs and labor costs. In the medical setting, the TDABC algorithm can be applied by defining a care delivery value chain for each aspect of patient care and then multiplying incremental cost per unit time by time required to deliver that resource (Figure 1). Tabulating the overall unit cost for each resource then yields the overall cost of the care cycle. Clinical outcomes data can then be determined and used to calculate overall value for the patient care cycle.

In the study reported here, we used the TDABC algorithm to calculate the direct financial costs of surgical treatment of rotator cuff tears confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in an academic medical center.

Methods

Per our institution’s Office for the Protection of Research Subjects, institutional review board (IRB) approval is required only for projects using “human subjects” as defined by federal policy. In the present study, no private information could be identified, and all data were obtained from hospital billing records without intervention or interaction with individual patients. Accordingly, IRB approval was deemed unnecessary for our economic cost analysis.

Billing records of a single academic fellowship-trained sports surgeon were reviewed to identify patients who underwent primary repair of an MRI-confirmed rotator cuff tear between April 1, 2009, and July 31, 2012. Patients who had undergone prior shoulder surgery of any type were excluded from the study. Operative reports were reviewed, and exact surgical procedures performed were noted. The operating surgeon selected the specific repair techniques, including single- or double-row repair, with emphasis on restoring footprint coverage and avoiding overtensioning.

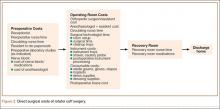

All surgeries were performed in an outpatient surgical center owned and operated by the surgeon’s home university. Surgeries were performed by the attending physician assisted by a senior orthopedic resident. The RCS care cycle was divided into 3 phases (Figure 2):

1. Preoperative. Patient’s interaction with receptionist in surgery center, time with preoperative nurse and circulating nurse in preoperative area, resident check-in time, and time placing preoperative nerve block and consumable materials used during block placement.

2. Operative. Time in operating room with surgical team for RCS, consumable materials used during surgery (eg, anchors, shavers, drapes), anesthetic medications, shoulder abduction pillow placed on completion of surgery, and cost of instrument processing.

3. Postoperative. Time in postoperative recovery area with recovery room nursing staff.

Time in each portion of the care cycle was directly observed and tabulated by hospital volunteers in the surgery center. Institutional billing data were used to identify material resources consumed, and the actual cost paid by the hospital for these resources was obtained from internal records. Mean hourly salary data and standard benefit rates were obtained for surgery center staff. Attending physician salary was extrapolated from published mean market salary data for academic physicians and mean hours worked,10,11 and resident physician costs were tabulated from publically available institutional payroll data and average resident work hours at our institution. These cost data and times were then used to tabulate total cost for the RCS care cycle using the TDABC algorithm.

Results