User login

Potential biomarkers of gray matter damage in MS identified

NEW ORLEANS – Protein profiling of cerebrospinal fluid and MRI has revealed the involvement of exacerbated gray matter demyelination and brain atrophy in the progression of multiple sclerosis.

The pattern of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, which correspond to the extent of gray matter damage, have potential value in stratifying patients in terms of disease severity from the onset of multiple sclerosis (MS), Roberta Magliozzi, Ph.D., of the University of Verona (Italy) said at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Gray matter atrophy and the accumulation of cortical lesions are central to the progressive clinical deterioration that occurs in MS. The damage involves a “compartmentalized immune response” featuring meningeal infiltration of certain immune cells, which is associated with increased cortical demyelination and meningeal inflammation. The gray matter damage and inflammation are harbingers of earlier onset and rapid progression of neurological damage in MS, and a more severe disease outcome.

“We sought to find a combination of CSF biomarkers [and] neuropathological and early neuroimaging correlates of disease progression in order to predict onset and rate of MS progression,” Dr. Magliozzi explained.

The investigators assessed gray matter damage with MRI and analyzed CSF proteins in 36 MS patients and 12 healthy controls and also acquired and analyzed meningeal and CSF samples after death from 20 individuals with secondary progressive MS (SPMS) and 10 healthy individuals to detect inflammatory mediators associated with meningeal infiltration that were released to the CSF.

MS patients with meningeal infiltration displayed more extensive gray matter demyelination and more rapid disease progression. They also demonstrated a “pronounced proinflammatory CSF profile” featuring overexpression of an array of molecules associated with chronic inflammation. Patients with less gray matter damage displayed a pattern of increased regulatory molecules. Consistent with the patient data, similar expression patterns were evident in the meninges and CSF samples of postmortem SPMS cases with a higher level of meningeal inflammation and gray matter demyelination.

“Meningeal infiltrates may represent the main source of intrathecal inflammatory activity mediating the gradient of cortical tissue injury since early disease stages and in progressive MS,” Dr. Magliozzi said.

The markedly different CSF profiles in patients with more and less extensive gray matter damage may be an exploitable characteristic to stratify patients early in the course of MS, with benefits in disease prognosis and monitoring, and treatment that is more rationally geared to the patient’s condition.

“The results indicate that we may be able to get an image-based functional profile of patients in relapse, which would be a phenomenal finding,” Dr. Jerry Wolinsky of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, commented in a press conference following the presentation.

The study was funded by Progressive MS Alliance. Dr. Magliozzi had no disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Protein profiling of cerebrospinal fluid and MRI has revealed the involvement of exacerbated gray matter demyelination and brain atrophy in the progression of multiple sclerosis.

The pattern of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, which correspond to the extent of gray matter damage, have potential value in stratifying patients in terms of disease severity from the onset of multiple sclerosis (MS), Roberta Magliozzi, Ph.D., of the University of Verona (Italy) said at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Gray matter atrophy and the accumulation of cortical lesions are central to the progressive clinical deterioration that occurs in MS. The damage involves a “compartmentalized immune response” featuring meningeal infiltration of certain immune cells, which is associated with increased cortical demyelination and meningeal inflammation. The gray matter damage and inflammation are harbingers of earlier onset and rapid progression of neurological damage in MS, and a more severe disease outcome.

“We sought to find a combination of CSF biomarkers [and] neuropathological and early neuroimaging correlates of disease progression in order to predict onset and rate of MS progression,” Dr. Magliozzi explained.

The investigators assessed gray matter damage with MRI and analyzed CSF proteins in 36 MS patients and 12 healthy controls and also acquired and analyzed meningeal and CSF samples after death from 20 individuals with secondary progressive MS (SPMS) and 10 healthy individuals to detect inflammatory mediators associated with meningeal infiltration that were released to the CSF.

MS patients with meningeal infiltration displayed more extensive gray matter demyelination and more rapid disease progression. They also demonstrated a “pronounced proinflammatory CSF profile” featuring overexpression of an array of molecules associated with chronic inflammation. Patients with less gray matter damage displayed a pattern of increased regulatory molecules. Consistent with the patient data, similar expression patterns were evident in the meninges and CSF samples of postmortem SPMS cases with a higher level of meningeal inflammation and gray matter demyelination.

“Meningeal infiltrates may represent the main source of intrathecal inflammatory activity mediating the gradient of cortical tissue injury since early disease stages and in progressive MS,” Dr. Magliozzi said.

The markedly different CSF profiles in patients with more and less extensive gray matter damage may be an exploitable characteristic to stratify patients early in the course of MS, with benefits in disease prognosis and monitoring, and treatment that is more rationally geared to the patient’s condition.

“The results indicate that we may be able to get an image-based functional profile of patients in relapse, which would be a phenomenal finding,” Dr. Jerry Wolinsky of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, commented in a press conference following the presentation.

The study was funded by Progressive MS Alliance. Dr. Magliozzi had no disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – Protein profiling of cerebrospinal fluid and MRI has revealed the involvement of exacerbated gray matter demyelination and brain atrophy in the progression of multiple sclerosis.

The pattern of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, which correspond to the extent of gray matter damage, have potential value in stratifying patients in terms of disease severity from the onset of multiple sclerosis (MS), Roberta Magliozzi, Ph.D., of the University of Verona (Italy) said at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Gray matter atrophy and the accumulation of cortical lesions are central to the progressive clinical deterioration that occurs in MS. The damage involves a “compartmentalized immune response” featuring meningeal infiltration of certain immune cells, which is associated with increased cortical demyelination and meningeal inflammation. The gray matter damage and inflammation are harbingers of earlier onset and rapid progression of neurological damage in MS, and a more severe disease outcome.

“We sought to find a combination of CSF biomarkers [and] neuropathological and early neuroimaging correlates of disease progression in order to predict onset and rate of MS progression,” Dr. Magliozzi explained.

The investigators assessed gray matter damage with MRI and analyzed CSF proteins in 36 MS patients and 12 healthy controls and also acquired and analyzed meningeal and CSF samples after death from 20 individuals with secondary progressive MS (SPMS) and 10 healthy individuals to detect inflammatory mediators associated with meningeal infiltration that were released to the CSF.

MS patients with meningeal infiltration displayed more extensive gray matter demyelination and more rapid disease progression. They also demonstrated a “pronounced proinflammatory CSF profile” featuring overexpression of an array of molecules associated with chronic inflammation. Patients with less gray matter damage displayed a pattern of increased regulatory molecules. Consistent with the patient data, similar expression patterns were evident in the meninges and CSF samples of postmortem SPMS cases with a higher level of meningeal inflammation and gray matter demyelination.

“Meningeal infiltrates may represent the main source of intrathecal inflammatory activity mediating the gradient of cortical tissue injury since early disease stages and in progressive MS,” Dr. Magliozzi said.

The markedly different CSF profiles in patients with more and less extensive gray matter damage may be an exploitable characteristic to stratify patients early in the course of MS, with benefits in disease prognosis and monitoring, and treatment that is more rationally geared to the patient’s condition.

“The results indicate that we may be able to get an image-based functional profile of patients in relapse, which would be a phenomenal finding,” Dr. Jerry Wolinsky of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, commented in a press conference following the presentation.

The study was funded by Progressive MS Alliance. Dr. Magliozzi had no disclosures.

AT ACTRIMS FORUM 2016

Key clinical point: The different CSF profiles in patients with more and less extensive gray matter damage may be useful to stratify patients early in the course of MS.

Major finding: Protein profiling of CSF and brain MRI has revealed the involvement of exacerbated gray matter demyelination and brain atrophy in the progression of multiple sclerosis.

Data source: A cohort study of 36 MS patients and 12 healthy controls and a postmortem study of 20 individuals with secondary progressive MS and 10 healthy individuals.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Progressive MS Alliance. Dr. Magliozzi had no disclosures.

Fibromyalgia doesn’t fit the disease model

You can help victims of hazing recover from psychological and physical harm

Initiation has been a part of the tradition of many sororities, fraternities, sports teams, and other organizations to screen and evaluate potential members. Initiation activities can range from humorous, such as pulling pranks on others, to more serious, such as being able to recite the organization’s rules and creed. It is used in the hopes of increasing a new member’s commitment to the group, with the goal of creating group cohesion.

Hazing is not initiation

Hazing is the use of ritualized physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the guise of initiation. Hazing activities do not help identify the qualities that a person needs for group membership, and can lead to severe physical and psychological harm. Many hazing rituals are done behind closed doors, some with a vow of secrecy.

Studies indicate that 47% of students have been hazed before college, and that 3 of every 5 college students have been subjected to hazing.1 Military and sports teams also have a high rate of hazing; 40% of athletes report that a coach or advisor knew about the hazing.2

Dangers of hazing

Victims of hazing might be brought to the emergency room with severe injury, including broken bones, burns, alcohol intoxication–related injury, chest trauma, multi-organ system failure, sexual trauma, and other medical emergencies, or could die from injuries sustained during hazing activities.

In the 44 states where hazing is illegal, hazing participants could be held be civilly and criminally liable for their actions. Hazing victims may be required to commit crimes, ranging from destruction of property to kidnapping. One-half of all hazing activities involve the use of alcohol,2 and 82% of hazing-related deaths involve alcohol.1

What is your role in treating hazing victims?

You might be called on to treat the psychological symptoms of hazing, including:

- depression

- anxiety

- acute stress syndrome

- alcohol- and drug-related delirium

- posttraumatic stress syndrome.

In addition, you might find yourself needing to:

Arrange for medical care immediately if the patient has a medical problem or an injury.

Contact a victim advocacy programif the victim has made allegations about, or there is evidence of, sexual assault, rape, other sexual injury, or physical or psychological violence.

Notify appropriate law enforcement personnel.

Notify the leadership of the organization (eg, team, school, club) within which the hazing occurred.

Perform a psychiatric assessment and provide treatment for the victim. Some symptoms seen in victims of hazing include sleep disturbance and insomnia, poor grades, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth, trust issues, and symptoms commonly seen in patients with posttraumatic stress syndrome. Symptoms sometimes appear immediately after a hazing event; other times, they develop weeks later. Supportive counseling, stabilization, and advocacy are the immediate goals.

Provide education and treatment for the perpetrator. Unlike bullying, most hazing is not instituted to harm the victim but is seen as a tradition and ritual to increase commitment and bonding. The perpetrator might feel surprise and guilt as to the harm that was done to the victim. Observers of hazing rituals might be traumatized by viewing participants humiliated or abused, and both observers and perpetrators as participants may face legal consequences. Counseling and group debriefing provide education and help them cope with these issues.

Act as a consultant to schools, teams, and other organizations to ensure that group cohesion and team building is obtained in a way that benefits the group and does not harm a member or the organization.

Psychiatrists can provide literature and information especially to adolescent and young adult patients who are at highest risk of hazing. Handouts, informational brochures and posters and be placed in the waiting areas for patient to view. These can be found online (such as www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/safety/and-hazing.pdf) or obtained from local colleges and school systems.

1. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: students at risk. http://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hazing_in_view_web1.pdf. Published March 11, 2008. Accessed May 18, 2015.

2. McBride HC. Parents beware: hazing poses significant danger to new college students. CRC Health. http://www.crchealth.com/treatment/treatment-for-teens/alcohol-addiction/hazing. Accessed May 18, 2015.

Initiation has been a part of the tradition of many sororities, fraternities, sports teams, and other organizations to screen and evaluate potential members. Initiation activities can range from humorous, such as pulling pranks on others, to more serious, such as being able to recite the organization’s rules and creed. It is used in the hopes of increasing a new member’s commitment to the group, with the goal of creating group cohesion.

Hazing is not initiation

Hazing is the use of ritualized physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the guise of initiation. Hazing activities do not help identify the qualities that a person needs for group membership, and can lead to severe physical and psychological harm. Many hazing rituals are done behind closed doors, some with a vow of secrecy.

Studies indicate that 47% of students have been hazed before college, and that 3 of every 5 college students have been subjected to hazing.1 Military and sports teams also have a high rate of hazing; 40% of athletes report that a coach or advisor knew about the hazing.2

Dangers of hazing

Victims of hazing might be brought to the emergency room with severe injury, including broken bones, burns, alcohol intoxication–related injury, chest trauma, multi-organ system failure, sexual trauma, and other medical emergencies, or could die from injuries sustained during hazing activities.

In the 44 states where hazing is illegal, hazing participants could be held be civilly and criminally liable for their actions. Hazing victims may be required to commit crimes, ranging from destruction of property to kidnapping. One-half of all hazing activities involve the use of alcohol,2 and 82% of hazing-related deaths involve alcohol.1

What is your role in treating hazing victims?

You might be called on to treat the psychological symptoms of hazing, including:

- depression

- anxiety

- acute stress syndrome

- alcohol- and drug-related delirium

- posttraumatic stress syndrome.

In addition, you might find yourself needing to:

Arrange for medical care immediately if the patient has a medical problem or an injury.

Contact a victim advocacy programif the victim has made allegations about, or there is evidence of, sexual assault, rape, other sexual injury, or physical or psychological violence.

Notify appropriate law enforcement personnel.

Notify the leadership of the organization (eg, team, school, club) within which the hazing occurred.

Perform a psychiatric assessment and provide treatment for the victim. Some symptoms seen in victims of hazing include sleep disturbance and insomnia, poor grades, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth, trust issues, and symptoms commonly seen in patients with posttraumatic stress syndrome. Symptoms sometimes appear immediately after a hazing event; other times, they develop weeks later. Supportive counseling, stabilization, and advocacy are the immediate goals.

Provide education and treatment for the perpetrator. Unlike bullying, most hazing is not instituted to harm the victim but is seen as a tradition and ritual to increase commitment and bonding. The perpetrator might feel surprise and guilt as to the harm that was done to the victim. Observers of hazing rituals might be traumatized by viewing participants humiliated or abused, and both observers and perpetrators as participants may face legal consequences. Counseling and group debriefing provide education and help them cope with these issues.

Act as a consultant to schools, teams, and other organizations to ensure that group cohesion and team building is obtained in a way that benefits the group and does not harm a member or the organization.

Psychiatrists can provide literature and information especially to adolescent and young adult patients who are at highest risk of hazing. Handouts, informational brochures and posters and be placed in the waiting areas for patient to view. These can be found online (such as www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/safety/and-hazing.pdf) or obtained from local colleges and school systems.

Initiation has been a part of the tradition of many sororities, fraternities, sports teams, and other organizations to screen and evaluate potential members. Initiation activities can range from humorous, such as pulling pranks on others, to more serious, such as being able to recite the organization’s rules and creed. It is used in the hopes of increasing a new member’s commitment to the group, with the goal of creating group cohesion.

Hazing is not initiation

Hazing is the use of ritualized physical, sexual, and psychological abuse in the guise of initiation. Hazing activities do not help identify the qualities that a person needs for group membership, and can lead to severe physical and psychological harm. Many hazing rituals are done behind closed doors, some with a vow of secrecy.

Studies indicate that 47% of students have been hazed before college, and that 3 of every 5 college students have been subjected to hazing.1 Military and sports teams also have a high rate of hazing; 40% of athletes report that a coach or advisor knew about the hazing.2

Dangers of hazing

Victims of hazing might be brought to the emergency room with severe injury, including broken bones, burns, alcohol intoxication–related injury, chest trauma, multi-organ system failure, sexual trauma, and other medical emergencies, or could die from injuries sustained during hazing activities.

In the 44 states where hazing is illegal, hazing participants could be held be civilly and criminally liable for their actions. Hazing victims may be required to commit crimes, ranging from destruction of property to kidnapping. One-half of all hazing activities involve the use of alcohol,2 and 82% of hazing-related deaths involve alcohol.1

What is your role in treating hazing victims?

You might be called on to treat the psychological symptoms of hazing, including:

- depression

- anxiety

- acute stress syndrome

- alcohol- and drug-related delirium

- posttraumatic stress syndrome.

In addition, you might find yourself needing to:

Arrange for medical care immediately if the patient has a medical problem or an injury.

Contact a victim advocacy programif the victim has made allegations about, or there is evidence of, sexual assault, rape, other sexual injury, or physical or psychological violence.

Notify appropriate law enforcement personnel.

Notify the leadership of the organization (eg, team, school, club) within which the hazing occurred.

Perform a psychiatric assessment and provide treatment for the victim. Some symptoms seen in victims of hazing include sleep disturbance and insomnia, poor grades, eating disorders, depression, anxiety, feelings of low self-esteem and self-worth, trust issues, and symptoms commonly seen in patients with posttraumatic stress syndrome. Symptoms sometimes appear immediately after a hazing event; other times, they develop weeks later. Supportive counseling, stabilization, and advocacy are the immediate goals.

Provide education and treatment for the perpetrator. Unlike bullying, most hazing is not instituted to harm the victim but is seen as a tradition and ritual to increase commitment and bonding. The perpetrator might feel surprise and guilt as to the harm that was done to the victim. Observers of hazing rituals might be traumatized by viewing participants humiliated or abused, and both observers and perpetrators as participants may face legal consequences. Counseling and group debriefing provide education and help them cope with these issues.

Act as a consultant to schools, teams, and other organizations to ensure that group cohesion and team building is obtained in a way that benefits the group and does not harm a member or the organization.

Psychiatrists can provide literature and information especially to adolescent and young adult patients who are at highest risk of hazing. Handouts, informational brochures and posters and be placed in the waiting areas for patient to view. These can be found online (such as www.doe.in.gov/sites/default/files/safety/and-hazing.pdf) or obtained from local colleges and school systems.

1. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: students at risk. http://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hazing_in_view_web1.pdf. Published March 11, 2008. Accessed May 18, 2015.

2. McBride HC. Parents beware: hazing poses significant danger to new college students. CRC Health. http://www.crchealth.com/treatment/treatment-for-teens/alcohol-addiction/hazing. Accessed May 18, 2015.

1. Allan EJ, Madden M. Hazing in view: students at risk. http://www.stophazing.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/hazing_in_view_web1.pdf. Published March 11, 2008. Accessed May 18, 2015.

2. McBride HC. Parents beware: hazing poses significant danger to new college students. CRC Health. http://www.crchealth.com/treatment/treatment-for-teens/alcohol-addiction/hazing. Accessed May 18, 2015.

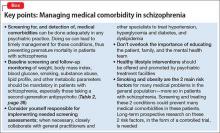

Reducing morbidity and mortality from common medical conditions in schizophrenia

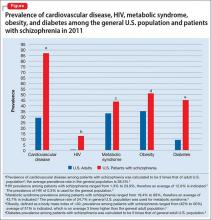

Life expectancy for both males and females has been increasing over the past several decades to an average of 76 years. However, the life expectancy among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States is 61 years—a 20% reduction.1 Patients with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk of several comorbid medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with healthy people (Figure, page 32).2-5 This risk may be heightened by several factors, including sedentary lifestyle, a high rate of cigarette use, poor self-management skills, homelessness, and poor diet.

Although substantial attention is paid to the psychiatric and behavioral management of schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of patients’ medical conditions, which have been implicated in excess unforeseen deaths. Patients with schizophrenia might experience delays in diagnosis, leading to more acute comorbidity at time of diagnosis and premature mortality

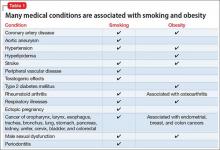

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among psychiatric patients.6 Key risk factors for cardiovascular disease include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia.7 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.8 In general, smoking and obesity are the most modifiable and preventable risk factors for many medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and many forms of cancer (Table 1).

In this article, we discuss how to manage common medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive management for all these medical conditions in this population is beyond the scope of this article; we limit ourselves to discussing (1) how common these conditions are in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population and (2) what can be done in psychiatric practice to manage these medical comorbidities (Box).

Obesity

Obesity—defined as body mass index (BMI) of >30—is common among patients with schizophrenia. The condition leads to poor self-image, decreased treatment adherence, and an increased risk of many chronic medical conditions (Table 1). Being overweight or obese can increase stigma and social discrimination, which will undermine self-esteem and, in turn, affect adherence with medications, leading to relapse.

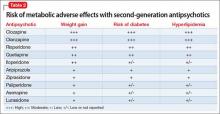

The prevalence of obesity among patients with schizophrenia is almost double that of the general population9 (Figure2-5). Several factors predispose these patients to overweight or obese, including sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, a high-fat diet, medications side effects, and genetic factors. Recent studies report the incidence of weight gain among patients treated with antipsychotics is as high as 80%10 (Table 2).

Mechanisms involved in antipsychotic-induced weight gain are not completely understood, but antagonism of serotonergic (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A), histamine (H1), dopamine (D2), muscarinic, and other receptors are involved in modulation of food intake. Decreased energy expenditure also has been blamed for antipsychotic-induced weight gain.10

Pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery can be as effective among patients with schizophrenia as they are among the general population. Maintaining a BMI of <25 kg/m2 lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6 Metformin has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing some metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia,11 and should be considered early when treating at-risk patients.

Managing obesity. Clinicians can apply several measures to manage obesity in a patient with schizophrenia:

- Educate the patient, and the family, about the risks of being overweight or obese.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Advise smoking cessation.

- When clinically appropriate, switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of weight gain—eg, from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2, page 36).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin with an antipsychotic; the drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in an overweight patient with schizophrenia.11

- Encourage the patient to engage in modest physical activity; for example, a 20-minute walk, every day, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Recommend a formal lifestyle modification program, such as behavioral group-based treatment for weight reduction.12

- Refer the patient and family to a dietitian.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

There is strong association between T2DM and schizophrenia that is related to abnormal glucose regulation independent of any adverse medication effect.13 Ryan et al14 reported that first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia had a higher level of intra-abdominal fat than age- and BMI-matched healthy controls, suggesting that schizophrenia could be associated with changes in adiposity that might increase the risk of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and dyslipidemia. Mechanisms that increase the risk of T2DM in schizophrenia include genetic and environmental factors, such as family history, lack of physical activity, and poor diet.

Diagnosis. All patients with schizophrenia should be evaluated for undiagnosed diabetes. The diagnosis of T2DM is made by documenting:

- a fasting plasma glucose reading of ≥126 mg/dL

- symptoms of T2DM, along with a random plasma glucose reading of ≥200 mg/dL

- 2-hour reading of a plasma glucose level >200 mg/dL on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Recent guidelines also suggest using a hemoglobin A1c value cutoff of ≥6.5% to diagnose T2DM.

In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, 38% of patients with schizophrenia and diabetes were not receiving any treatment for T2DM.15

Risk factors for T2DM are:

- BMI >25

- a first-degree relative with diabetes

- lack of physical activity

- being a member of a high-risk ethnic group (African American, Hispanic American, Native American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander)

- having delivered a baby >9 lb or having had gestational diabetes

- hypertension

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of ≤35 mg/dL

- triglyceride level of ≥250 mg/dL

- history of an abnormal glucose tolerance test

- history of abnormal findings on a fasting plasma glucose test

- history of vascular disease.

Early detection and management.

- Educate the patient and family about signs and symptoms of T2DM, such as polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia, fatigue, visual disturbances, and (in women) vulvitis. Also, psychiatrists should be aware of, and inquire about, symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis.

- At the start of therapy with any antipsychotic, particularly a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), ask patients about a family history of diabetes and measure the hemoglobin A1c value.

- Monitor the hemoglobin A1c level 4 months after starting an antipsychotic, then annually, in a patient with significant risk factors for diabetes.

- Monitor blood glucose every 6 months in patients with no change from initial results and more frequently in those with significant risk factors for diabetes and those who gain weight.

- Order a lipid panel and measure the serum glucose level to rule out dyslipidemia and diabetes, because a patient with high lipid levels and diabetes is at higher risk of developing cardiovascular conditions.

- Advocate for smoking cessation.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of diabetes when clinically appropriate, such as switching a patient from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (such as haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin along with antipsychotics. Metformin has been used to improve insulin sensitivity and can lead to weight loss in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. The drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia.11 Metformin is simple to use, does not lead to hypoglycemia, does not require serum glucose monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile.11

- Educate the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk every day reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer the patient to a dietitian to develop an appropriate diet plan.

- When diabetes is diagnosed, ensure appropriate follow-up and initiation or continuation of therapy with a general practitioner or an endocrinologist.

- Reinforce the need for ongoing follow-up and compliance with therapy for diabetes.

Hyperlipidemia and dyslipidemia

Elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels are associated with cardiovascular diseases, such as ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction. A 10% increase in cholesterol levels is associated with a 20% to 30% increase in the risk of coronary artery disease; lowering cholesterol by 10% decreases the risk by 20% to 30%.16 Triglyceride levels ≥250 mg/dL are associated with 2-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease.16

The incidence of dyslipidemia is not as well studied as diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. There is increased prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population because of obesity, lack of physical activity, and poor dietary habits.16

Data regarding the effects of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) on lipid levels are limited, but high-potency drugs, such as haloperidol, seem to carry a lower risk of hyperlipidemia than low-potency drugs, such as chlorpromazine and thioridazine.17 A comprehensive review on the effects of SGAs on plasma lipid levels suggested that clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine are associated with a higher risk of dyslipidemia17 (Table 2).

In the CATIE study, olanzapine and clozapine were associated with a greater increase in the serum level of cholesterol and triglycerides compared with other antipsychotics, even after adjusting for treatment duration. Furthermore, a retrospective chart review of patients who switched to aripiprazole from other SGAs showed a decrease in levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol15 (Table 2).

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to have dyslipidemia go undiagnosed, and therefore are less likely to be treated for the disorder. In the CATIE study, 88% of patients with dyslipidemia were not receiving any treatment.15

Management for dyslipidemia.

- Educate the patient and family about risks involved with dyslipidemia.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Monitor lipids to rule out dyslipidemia. Obtain a pretreatment fasting or random lipid profile for any patient receiving an antipsychotic; repeat at least every 6 months after starting the antipsychotic.

- Counsel the patient to quit smoking.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with lower risk of weight gain and dyslipidemia, such as switching from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotics (such as, haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer to a dietitian if indicated.

- Ensure follow-up and initiation of treatment with a general practitioner.

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.

Metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is cluster of cardiovascular risk factors, including central adiposity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. The National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III report defines metabolic syndrome as the presence of 3 of 5 of the following factors:

- abdominal obesity (waist circumference of >40 inches in men, or >35 inches in women)

- triglyceride level, >150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol, <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women

- blood pressure, >130/85 mm Hg

- fasting plasma glucose level, >110 mg/dL.

The presence of metabolic syndrome in the general population is a strong predictor of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.18 The adverse effects of metabolic syndrome are thought to relate to atherogenic dyslipidemia, higher blood pressure, insulin resistance with or without glucose intolerance, a proinflammatory state, and a prothrombotic state.

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia is 2- to 3-fold higher than the general population.19 In the CATIE study, approximately one-third of patients met criteria for metabolic syndrome at baseline.15 In a prospective study, De Hert et al20 reported that patients who were started on a SGA had more than twice the rate of developing metabolic syndrome compared with those treated with a FGA (Table 2). Other possible causes of metabolic syndrome are visceral adiposity and insulin resistance.16Management of the metabolic syndrome involves addressing the individual components that have been described in the preceding sections on T2DM and dyslipidemia.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is thought to be the most common blood-borne illness, with an estimated prevalence of 1% of the U.S. population. Some studies suggest that as many as 16% of people with schizophrenia have HCV infection.4 Risk factors for HCV infection include unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.

HCV treatments typically have involved regimens with interferon alfa, which is associated with significant neuropsychiatric side effects, including depression and suicide. There is a dearth of research on treatment of HCV in patients with schizophrenia; however, at least 1 study suggests that there was no increase in psychiatric symptoms in patients treated with interferon-containing regimens.21 There is even less evidence to guide the use of newer, non-interferon–based HCV treatment regimens that are better tolerated and have a higher response rate in the general population; there is reason, however, to be hopeful about their potential in patients with schizophrenia and HCV infection.

Managing HCV infection.

- Educate the patients and family about risk factors associated with contracting HCV.

- Screen for HCV infection in patients with schizophrenia because there is higher prevalence of HCV in these patients compared with the general population.

- When HCV infection is diagnosed, educate the patients and family about available treatments.

- Facilitate referral to an HCV specialist for appropriate treatment.

HIV/AIDS

HIV infection is highly prevalent among people suffering from severe mental illness such as schizophrenia. The incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia is estimated to be 4% to 23%, compared with 0.6% in the general population.22 Risk factors associated with a higher incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia are lack of knowledge about contracting HIV, unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.22

Managing HIV/AIDS.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with contracting HIV/AIDS.

- Educate patients about safe sex practices.

- All patients with schizophrenia should be screened for HIV because there is 10-fold higher HIV prevalence in schizophrenia compared with the general population.

- When HIV infection is diagnosed, facilitate referral to a HIV or infectious disease specialist for treatment.

- Educate the patient in whom HIV/AIDS has been diagnosed about the importance of (1) adherence to his (her) HIV medication regimen and (2) follow-up visits with an infectious disease practitioner and appropriate laboratory tests.

- Educate the patient’s family and significant other about the illness.

- Screen for and treat substance use.

- At each visit, inquire about the patient’s adherence to HIV medical therapy, viral load, and CD4 cell count.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to suffer from respiratory disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, compared with the general population.23 Smoking is a major risk factor for COPD. In a study by Dickerson et al,24 64% of people with schizophrenia were current smokers, compared with 19% of those without mental illness.

A high rate of smoking rate among people with schizophrenia suggests a “self-medication” hypothesis: That is, stimulation of CNS nicotinic cholinergic receptors treats the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and overcomes the dopamine blocking effects of antipsychotics.25 Among SGAs, only clozapine has a substantial body of evidence to support its association with decreased smoking behavior.

Managing COPD.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with COPD and smoking.

- Screen for tobacco use at each visit; try to increase motivation to quit smoking.

- Educate the patients and family about the value and availability of smoking cessation programs.

- Prescribe medication to help with smoking cessation when needed. Bupropion and varenicline have been shown to be effective in patients with schizophrenia; nicotine replacement therapies are safe and can be helpful.

- When treating a patient who is in the process of quitting, encourage and help him to maintain his commitment and enlist support from his family.

- Refer to an appropriate medical provider (primary care provider or pulmonologist) for a patient with an established or suspected diagnosis of COPD.

Cancer

Since 1909, when the Board of Control of the Commissioners in Lunacy for England and Wales noted the possibility of a decreased incidence in cancer among psychiatric patients, this connection has been a matter of controversy.26 Subsequent research has been equivocal; the prevalence of cancer has been reported to be either increased, similar, or decreased compared with the general population.26-28 Risk factors for cancer, including smoking, obesity, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, and hyperprolactinemia, are more common among patients with schizophrenia.

Genetic factors and a possible protective effect from antipsychotics have been cited as potential causes of decreased prevalence. Clozapine is associated with an increased risk of leukemia. No conclusion can be drawn about the overall prevalence of cancer in schizophrenia.

Managing cancer in a patient with schizophrenia, however, poses a significant challenge29; he might lack capacity to make decisions about cancer treatment. The patient—or his surrogate decision-makers—need to carefully weigh current quality of life against potential benefits of treatment and risks of side effects. Adherence to complex, often toxic, therapies can be challenging for the patient with psychosis. Successful cancer treatment often requires close collaboration between the cancer treatment team and the patient’s support system, including the treating psychiatrist and case management teams.

Bottom Line

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk of developing comorbid medical

conditions because of the illness itself, lifestyle behaviors, genetics, and adverse

effects of medications. Because mental health clinicians focus attention on the

psychiatric and behavioral aspect of treatment, often there is delay in screening,

detecting, and treating medical comorbidities. This screening can be done in any

psychiatric practice, which can lead to timely management for those conditions

and preventing premature mortality in patients with schizophrenia.

1. Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212-217.

2. De Hert M, Correl CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorder. I. Prevalence, impact of medications, and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52-77.

3. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics update-2011 update. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18-e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701.

4. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):31-37.

5. Lovre D, Mauvais-Jarvis F. Trends in prevalence of the metabolic syndrome. JAMA. 2015;314(9):950.

6. Hennekens CH, Hennekens AR, Hollar D, et al. Schizophrenia and increased risks of cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 2005;150(6):1115-1121.

7. Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical point. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):17-25.

8. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

9. Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Heo M et al. The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(4):215-220.

10. Allison DB, Mentore JL, Heo M, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a comprehensive research synthesis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(11):1686-1696.

11. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al; METS Investigators. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

12. Ganguli R. Behavioral therapy for weight loss in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(suppl 4):19-25.

13. Kohen D. Diabetes mellitus and schizophrenia: historical perspective. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;47:S64-S66.

14. Ryan MC, Flanagan S, Kinsella U, et al. The effects of atypical antipsychotics on visceral fat distribution in first episode, drug naïve patients with schizophrenia. Life Sci. 2004;74(16):1999-2008.

15. McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):19-32.

16. Barnett AH, Mackin P, Chaudhry I, et al. Minimising metabolic and cardiovascular risk in schizophrenia: diabetes, obesity and dyslipidaemia. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(4):357-373.

17. Meyer JM, Koro CE. The effects of antipsychotic therapy on serum lipids: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(1):1-17.

18. Sacks FM. Metabolic syndrome: epidemiology and consequences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 18):3-12.

19. De Hert M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, et al. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(1):15-22.

20. De Hert M, Hanssens L, Wampers M, et al. Prevalence and incidence rates of metabolic abnormalities and diabetes in a prospective study of patients treated with second-generation antipsychotics. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:560.

21. Huckans M, Mitchell A, Pavawalla S, et al. The influence of antiviral therapy on psychiatric symptoms among patients with hepatitis C and schizophrenia. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(1):111-119.

22. Davidson S, Judd F, Jolley D, et al. Risk factors for HIV/AIDS and hepatitis C among the chronic mentally ill. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35(2):203-209.

23. Copeland LA, Mortensen EM, Zeber JE, et al. Pulmonary disease among inpatient decendents: impact of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(3):720-726.

24. Dickerson F, Stallings CR, Origoni AE, et al. Cigarette smoking among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in routine clinical settings, 1999-2011. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(1):44-50.

25. Dalack GW, Healy DJ, Meador-Woodruff JH. Nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: clinical phenomena and laboratory findings. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1490-1501.

26. Hodgson R, Wildgust HJ, Bushe CJ. Cancer and schizophrenia: is there a paradox? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(suppl 4):51-60.

27. Hippisley-Cox J, Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, et al. Risk of malignancy in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: nested case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1368-1376.

28. Grinshpoon A, Barchana M, Ponizovsky A, et al. Cancer in schizophrenia: is the risk higher or lower? Schizophr Res. 2005;73(2-3):333-341.

29. Hwang M, Farasatpour M, Williams CD, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer patients with schizophrenia. Oncol Lett. 2012;3(4):845-850.

Life expectancy for both males and females has been increasing over the past several decades to an average of 76 years. However, the life expectancy among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States is 61 years—a 20% reduction.1 Patients with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk of several comorbid medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with healthy people (Figure, page 32).2-5 This risk may be heightened by several factors, including sedentary lifestyle, a high rate of cigarette use, poor self-management skills, homelessness, and poor diet.

Although substantial attention is paid to the psychiatric and behavioral management of schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of patients’ medical conditions, which have been implicated in excess unforeseen deaths. Patients with schizophrenia might experience delays in diagnosis, leading to more acute comorbidity at time of diagnosis and premature mortality

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among psychiatric patients.6 Key risk factors for cardiovascular disease include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia.7 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.8 In general, smoking and obesity are the most modifiable and preventable risk factors for many medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and many forms of cancer (Table 1).

In this article, we discuss how to manage common medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive management for all these medical conditions in this population is beyond the scope of this article; we limit ourselves to discussing (1) how common these conditions are in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population and (2) what can be done in psychiatric practice to manage these medical comorbidities (Box).

Obesity

Obesity—defined as body mass index (BMI) of >30—is common among patients with schizophrenia. The condition leads to poor self-image, decreased treatment adherence, and an increased risk of many chronic medical conditions (Table 1). Being overweight or obese can increase stigma and social discrimination, which will undermine self-esteem and, in turn, affect adherence with medications, leading to relapse.

The prevalence of obesity among patients with schizophrenia is almost double that of the general population9 (Figure2-5). Several factors predispose these patients to overweight or obese, including sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, a high-fat diet, medications side effects, and genetic factors. Recent studies report the incidence of weight gain among patients treated with antipsychotics is as high as 80%10 (Table 2).

Mechanisms involved in antipsychotic-induced weight gain are not completely understood, but antagonism of serotonergic (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A), histamine (H1), dopamine (D2), muscarinic, and other receptors are involved in modulation of food intake. Decreased energy expenditure also has been blamed for antipsychotic-induced weight gain.10

Pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery can be as effective among patients with schizophrenia as they are among the general population. Maintaining a BMI of <25 kg/m2 lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6 Metformin has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing some metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia,11 and should be considered early when treating at-risk patients.

Managing obesity. Clinicians can apply several measures to manage obesity in a patient with schizophrenia:

- Educate the patient, and the family, about the risks of being overweight or obese.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Advise smoking cessation.

- When clinically appropriate, switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of weight gain—eg, from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2, page 36).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin with an antipsychotic; the drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in an overweight patient with schizophrenia.11

- Encourage the patient to engage in modest physical activity; for example, a 20-minute walk, every day, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Recommend a formal lifestyle modification program, such as behavioral group-based treatment for weight reduction.12

- Refer the patient and family to a dietitian.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

There is strong association between T2DM and schizophrenia that is related to abnormal glucose regulation independent of any adverse medication effect.13 Ryan et al14 reported that first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia had a higher level of intra-abdominal fat than age- and BMI-matched healthy controls, suggesting that schizophrenia could be associated with changes in adiposity that might increase the risk of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and dyslipidemia. Mechanisms that increase the risk of T2DM in schizophrenia include genetic and environmental factors, such as family history, lack of physical activity, and poor diet.

Diagnosis. All patients with schizophrenia should be evaluated for undiagnosed diabetes. The diagnosis of T2DM is made by documenting:

- a fasting plasma glucose reading of ≥126 mg/dL

- symptoms of T2DM, along with a random plasma glucose reading of ≥200 mg/dL

- 2-hour reading of a plasma glucose level >200 mg/dL on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Recent guidelines also suggest using a hemoglobin A1c value cutoff of ≥6.5% to diagnose T2DM.

In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, 38% of patients with schizophrenia and diabetes were not receiving any treatment for T2DM.15

Risk factors for T2DM are:

- BMI >25

- a first-degree relative with diabetes

- lack of physical activity

- being a member of a high-risk ethnic group (African American, Hispanic American, Native American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander)

- having delivered a baby >9 lb or having had gestational diabetes

- hypertension

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of ≤35 mg/dL

- triglyceride level of ≥250 mg/dL

- history of an abnormal glucose tolerance test

- history of abnormal findings on a fasting plasma glucose test

- history of vascular disease.

Early detection and management.

- Educate the patient and family about signs and symptoms of T2DM, such as polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia, fatigue, visual disturbances, and (in women) vulvitis. Also, psychiatrists should be aware of, and inquire about, symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis.

- At the start of therapy with any antipsychotic, particularly a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), ask patients about a family history of diabetes and measure the hemoglobin A1c value.

- Monitor the hemoglobin A1c level 4 months after starting an antipsychotic, then annually, in a patient with significant risk factors for diabetes.

- Monitor blood glucose every 6 months in patients with no change from initial results and more frequently in those with significant risk factors for diabetes and those who gain weight.

- Order a lipid panel and measure the serum glucose level to rule out dyslipidemia and diabetes, because a patient with high lipid levels and diabetes is at higher risk of developing cardiovascular conditions.

- Advocate for smoking cessation.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of diabetes when clinically appropriate, such as switching a patient from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (such as haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin along with antipsychotics. Metformin has been used to improve insulin sensitivity and can lead to weight loss in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. The drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia.11 Metformin is simple to use, does not lead to hypoglycemia, does not require serum glucose monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile.11

- Educate the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk every day reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer the patient to a dietitian to develop an appropriate diet plan.

- When diabetes is diagnosed, ensure appropriate follow-up and initiation or continuation of therapy with a general practitioner or an endocrinologist.

- Reinforce the need for ongoing follow-up and compliance with therapy for diabetes.

Hyperlipidemia and dyslipidemia

Elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels are associated with cardiovascular diseases, such as ischemic heart disease and myocardial infarction. A 10% increase in cholesterol levels is associated with a 20% to 30% increase in the risk of coronary artery disease; lowering cholesterol by 10% decreases the risk by 20% to 30%.16 Triglyceride levels ≥250 mg/dL are associated with 2-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease.16

The incidence of dyslipidemia is not as well studied as diabetes in patients with schizophrenia. There is increased prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population because of obesity, lack of physical activity, and poor dietary habits.16

Data regarding the effects of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) on lipid levels are limited, but high-potency drugs, such as haloperidol, seem to carry a lower risk of hyperlipidemia than low-potency drugs, such as chlorpromazine and thioridazine.17 A comprehensive review on the effects of SGAs on plasma lipid levels suggested that clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine are associated with a higher risk of dyslipidemia17 (Table 2).

In the CATIE study, olanzapine and clozapine were associated with a greater increase in the serum level of cholesterol and triglycerides compared with other antipsychotics, even after adjusting for treatment duration. Furthermore, a retrospective chart review of patients who switched to aripiprazole from other SGAs showed a decrease in levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol15 (Table 2).

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to have dyslipidemia go undiagnosed, and therefore are less likely to be treated for the disorder. In the CATIE study, 88% of patients with dyslipidemia were not receiving any treatment.15

Management for dyslipidemia.

- Educate the patient and family about risks involved with dyslipidemia.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Monitor lipids to rule out dyslipidemia. Obtain a pretreatment fasting or random lipid profile for any patient receiving an antipsychotic; repeat at least every 6 months after starting the antipsychotic.

- Counsel the patient to quit smoking.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with lower risk of weight gain and dyslipidemia, such as switching from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotics (such as, haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer to a dietitian if indicated.

- Ensure follow-up and initiation of treatment with a general practitioner.

- Educate and encourage the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk everyday will reduce cardiovascular disease risk by 35% to 55%.

Metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is cluster of cardiovascular risk factors, including central adiposity, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. The National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III report defines metabolic syndrome as the presence of 3 of 5 of the following factors:

- abdominal obesity (waist circumference of >40 inches in men, or >35 inches in women)

- triglyceride level, >150 mg/dL

- HDL cholesterol, <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women

- blood pressure, >130/85 mm Hg

- fasting plasma glucose level, >110 mg/dL.

The presence of metabolic syndrome in the general population is a strong predictor of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.18 The adverse effects of metabolic syndrome are thought to relate to atherogenic dyslipidemia, higher blood pressure, insulin resistance with or without glucose intolerance, a proinflammatory state, and a prothrombotic state.

The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia is 2- to 3-fold higher than the general population.19 In the CATIE study, approximately one-third of patients met criteria for metabolic syndrome at baseline.15 In a prospective study, De Hert et al20 reported that patients who were started on a SGA had more than twice the rate of developing metabolic syndrome compared with those treated with a FGA (Table 2). Other possible causes of metabolic syndrome are visceral adiposity and insulin resistance.16Management of the metabolic syndrome involves addressing the individual components that have been described in the preceding sections on T2DM and dyslipidemia.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is thought to be the most common blood-borne illness, with an estimated prevalence of 1% of the U.S. population. Some studies suggest that as many as 16% of people with schizophrenia have HCV infection.4 Risk factors for HCV infection include unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.

HCV treatments typically have involved regimens with interferon alfa, which is associated with significant neuropsychiatric side effects, including depression and suicide. There is a dearth of research on treatment of HCV in patients with schizophrenia; however, at least 1 study suggests that there was no increase in psychiatric symptoms in patients treated with interferon-containing regimens.21 There is even less evidence to guide the use of newer, non-interferon–based HCV treatment regimens that are better tolerated and have a higher response rate in the general population; there is reason, however, to be hopeful about their potential in patients with schizophrenia and HCV infection.

Managing HCV infection.

- Educate the patients and family about risk factors associated with contracting HCV.

- Screen for HCV infection in patients with schizophrenia because there is higher prevalence of HCV in these patients compared with the general population.

- When HCV infection is diagnosed, educate the patients and family about available treatments.

- Facilitate referral to an HCV specialist for appropriate treatment.

HIV/AIDS

HIV infection is highly prevalent among people suffering from severe mental illness such as schizophrenia. The incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia is estimated to be 4% to 23%, compared with 0.6% in the general population.22 Risk factors associated with a higher incidence of HIV/AIDS in patients with schizophrenia are lack of knowledge about contracting HIV, unsafe sexual practices, prostitution, homosexuality, homelessness, and IV drug use.22

Managing HIV/AIDS.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with contracting HIV/AIDS.

- Educate patients about safe sex practices.

- All patients with schizophrenia should be screened for HIV because there is 10-fold higher HIV prevalence in schizophrenia compared with the general population.

- When HIV infection is diagnosed, facilitate referral to a HIV or infectious disease specialist for treatment.

- Educate the patient in whom HIV/AIDS has been diagnosed about the importance of (1) adherence to his (her) HIV medication regimen and (2) follow-up visits with an infectious disease practitioner and appropriate laboratory tests.

- Educate the patient’s family and significant other about the illness.

- Screen for and treat substance use.

- At each visit, inquire about the patient’s adherence to HIV medical therapy, viral load, and CD4 cell count.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to suffer from respiratory disease, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma, compared with the general population.23 Smoking is a major risk factor for COPD. In a study by Dickerson et al,24 64% of people with schizophrenia were current smokers, compared with 19% of those without mental illness.

A high rate of smoking rate among people with schizophrenia suggests a “self-medication” hypothesis: That is, stimulation of CNS nicotinic cholinergic receptors treats the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and overcomes the dopamine blocking effects of antipsychotics.25 Among SGAs, only clozapine has a substantial body of evidence to support its association with decreased smoking behavior.

Managing COPD.

- Educate the patient and family about risk factors associated with COPD and smoking.

- Screen for tobacco use at each visit; try to increase motivation to quit smoking.

- Educate the patients and family about the value and availability of smoking cessation programs.

- Prescribe medication to help with smoking cessation when needed. Bupropion and varenicline have been shown to be effective in patients with schizophrenia; nicotine replacement therapies are safe and can be helpful.

- When treating a patient who is in the process of quitting, encourage and help him to maintain his commitment and enlist support from his family.

- Refer to an appropriate medical provider (primary care provider or pulmonologist) for a patient with an established or suspected diagnosis of COPD.

Cancer

Since 1909, when the Board of Control of the Commissioners in Lunacy for England and Wales noted the possibility of a decreased incidence in cancer among psychiatric patients, this connection has been a matter of controversy.26 Subsequent research has been equivocal; the prevalence of cancer has been reported to be either increased, similar, or decreased compared with the general population.26-28 Risk factors for cancer, including smoking, obesity, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, and hyperprolactinemia, are more common among patients with schizophrenia.

Genetic factors and a possible protective effect from antipsychotics have been cited as potential causes of decreased prevalence. Clozapine is associated with an increased risk of leukemia. No conclusion can be drawn about the overall prevalence of cancer in schizophrenia.

Managing cancer in a patient with schizophrenia, however, poses a significant challenge29; he might lack capacity to make decisions about cancer treatment. The patient—or his surrogate decision-makers—need to carefully weigh current quality of life against potential benefits of treatment and risks of side effects. Adherence to complex, often toxic, therapies can be challenging for the patient with psychosis. Successful cancer treatment often requires close collaboration between the cancer treatment team and the patient’s support system, including the treating psychiatrist and case management teams.

Bottom Line

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk of developing comorbid medical

conditions because of the illness itself, lifestyle behaviors, genetics, and adverse

effects of medications. Because mental health clinicians focus attention on the

psychiatric and behavioral aspect of treatment, often there is delay in screening,

detecting, and treating medical comorbidities. This screening can be done in any

psychiatric practice, which can lead to timely management for those conditions

and preventing premature mortality in patients with schizophrenia.

Life expectancy for both males and females has been increasing over the past several decades to an average of 76 years. However, the life expectancy among individuals with schizophrenia in the United States is 61 years—a 20% reduction.1 Patients with schizophrenia are known to be at increased risk of several comorbid medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), coronary artery disease, and digestive and liver disorders, compared with healthy people (Figure, page 32).2-5 This risk may be heightened by several factors, including sedentary lifestyle, a high rate of cigarette use, poor self-management skills, homelessness, and poor diet.

Although substantial attention is paid to the psychiatric and behavioral management of schizophrenia, many barriers impede the detection and treatment of patients’ medical conditions, which have been implicated in excess unforeseen deaths. Patients with schizophrenia might experience delays in diagnosis, leading to more acute comorbidity at time of diagnosis and premature mortality

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among psychiatric patients.6 Key risk factors for cardiovascular disease include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and lack of physical activity, all of which are more prevalent among patients with schizophrenia.7 In addition, antipsychotics are associated with adverse metabolic effects.8 In general, smoking and obesity are the most modifiable and preventable risk factors for many medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and many forms of cancer (Table 1).

In this article, we discuss how to manage common medical comorbidities in patients with schizophrenia. Comprehensive management for all these medical conditions in this population is beyond the scope of this article; we limit ourselves to discussing (1) how common these conditions are in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population and (2) what can be done in psychiatric practice to manage these medical comorbidities (Box).

Obesity

Obesity—defined as body mass index (BMI) of >30—is common among patients with schizophrenia. The condition leads to poor self-image, decreased treatment adherence, and an increased risk of many chronic medical conditions (Table 1). Being overweight or obese can increase stigma and social discrimination, which will undermine self-esteem and, in turn, affect adherence with medications, leading to relapse.

The prevalence of obesity among patients with schizophrenia is almost double that of the general population9 (Figure2-5). Several factors predispose these patients to overweight or obese, including sedentary lifestyle, lack of exercise, a high-fat diet, medications side effects, and genetic factors. Recent studies report the incidence of weight gain among patients treated with antipsychotics is as high as 80%10 (Table 2).

Mechanisms involved in antipsychotic-induced weight gain are not completely understood, but antagonism of serotonergic (5-HT2C, 5-HT1A), histamine (H1), dopamine (D2), muscarinic, and other receptors are involved in modulation of food intake. Decreased energy expenditure also has been blamed for antipsychotic-induced weight gain.10

Pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery can be as effective among patients with schizophrenia as they are among the general population. Maintaining a BMI of <25 kg/m2 lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6 Metformin has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing some metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia,11 and should be considered early when treating at-risk patients.

Managing obesity. Clinicians can apply several measures to manage obesity in a patient with schizophrenia:

- Educate the patient, and the family, about the risks of being overweight or obese.

- Monitor weight and BMI at each visit.

- Advise smoking cessation.

- When clinically appropriate, switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of weight gain—eg, from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (eg, haloperidol, perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2, page 36).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin with an antipsychotic; the drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in an overweight patient with schizophrenia.11

- Encourage the patient to engage in modest physical activity; for example, a 20-minute walk, every day, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Recommend a formal lifestyle modification program, such as behavioral group-based treatment for weight reduction.12

- Refer the patient and family to a dietitian.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

There is strong association between T2DM and schizophrenia that is related to abnormal glucose regulation independent of any adverse medication effect.13 Ryan et al14 reported that first-episode, drug-naïve patients with schizophrenia had a higher level of intra-abdominal fat than age- and BMI-matched healthy controls, suggesting that schizophrenia could be associated with changes in adiposity that might increase the risk of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and dyslipidemia. Mechanisms that increase the risk of T2DM in schizophrenia include genetic and environmental factors, such as family history, lack of physical activity, and poor diet.

Diagnosis. All patients with schizophrenia should be evaluated for undiagnosed diabetes. The diagnosis of T2DM is made by documenting:

- a fasting plasma glucose reading of ≥126 mg/dL

- symptoms of T2DM, along with a random plasma glucose reading of ≥200 mg/dL

- 2-hour reading of a plasma glucose level >200 mg/dL on an oral glucose tolerance test.

Recent guidelines also suggest using a hemoglobin A1c value cutoff of ≥6.5% to diagnose T2DM.

In the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) study, 38% of patients with schizophrenia and diabetes were not receiving any treatment for T2DM.15

Risk factors for T2DM are:

- BMI >25

- a first-degree relative with diabetes

- lack of physical activity

- being a member of a high-risk ethnic group (African American, Hispanic American, Native American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander)

- having delivered a baby >9 lb or having had gestational diabetes

- hypertension

- high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level of ≤35 mg/dL

- triglyceride level of ≥250 mg/dL

- history of an abnormal glucose tolerance test

- history of abnormal findings on a fasting plasma glucose test

- history of vascular disease.

Early detection and management.

- Educate the patient and family about signs and symptoms of T2DM, such as polyuria, nocturia, polydipsia, fatigue, visual disturbances, and (in women) vulvitis. Also, psychiatrists should be aware of, and inquire about, symptoms of diabetic ketoacidosis.

- At the start of therapy with any antipsychotic, particularly a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), ask patients about a family history of diabetes and measure the hemoglobin A1c value.

- Monitor the hemoglobin A1c level 4 months after starting an antipsychotic, then annually, in a patient with significant risk factors for diabetes.

- Monitor blood glucose every 6 months in patients with no change from initial results and more frequently in those with significant risk factors for diabetes and those who gain weight.

- Order a lipid panel and measure the serum glucose level to rule out dyslipidemia and diabetes, because a patient with high lipid levels and diabetes is at higher risk of developing cardiovascular conditions.

- Advocate for smoking cessation.

- Switch to an antipsychotic with a lower risk of diabetes when clinically appropriate, such as switching a patient from olanzapine or high-dose quetiapine to a high- or medium-potency typical antipsychotic (such as haloperidol or perphenazine), ziprasidone, aripiprazole, iloperidone, and lurasidone (Table 2).

- Consider prophylactic use of metformin along with antipsychotics. Metformin has been used to improve insulin sensitivity and can lead to weight loss in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. The drug has modest potential for offsetting weight gain and providing better metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia.11 Metformin is simple to use, does not lead to hypoglycemia, does not require serum glucose monitoring, and has a favorable safety profile.11

- Educate the patient about modest physical activity. For example, a 20-minute walk every day reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by 35% to 55%.6

- Refer the patient to a dietitian to develop an appropriate diet plan.

- When diabetes is diagnosed, ensure appropriate follow-up and initiation or continuation of therapy with a general practitioner or an endocrinologist.

- Reinforce the need for ongoing follow-up and compliance with therapy for diabetes.

Hyperlipidemia and dyslipidemia