User login

Imposing treatment on patients with eating disorders: What are the legal risks?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the general hospital where I perform consultations, the medical service asked me to fill out psychiatric “hold” documents to keep a severely malnourished young woman with anorexia nervosa from leaving the hospital. Ms. Q, whose body mass index (BMI) was 12 (yes, 12), came to the hospital to have her “electrolytes fixed.” She was willing to stay the night for electrolyte repletion, but insisted she could gain weight on her own at home.

I’m worried that she might die without prompt inpatient treatment; she needs to stay on the medical service. Should I fill out a psychiatric hold to keep her there? What legal risks could I face if Ms. Q is detained and force-fed against her will? What are the legal risks of letting her leave the hospital before she is medically stable?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

When a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder arrives on a medical floor, treatment teams often ask psychiatric consultants to help them impose care the patient desperately needs but doesn’t want. This reaction is understandable. After all, an eating disorder is a psychiatric illness, and hospital-based psychiatrists have experience with treating involuntary patients. A psychiatric hold may seem like a sensible way to save the life of a hospitalized patient with a mental illness.

But filling out a psychiatric hold only scratches the surface of what a psychiatric consultant’s contribution should include; in Ms. Q’s case, initiating a psychiatric hold is probably the wrong thing to do.

Why would filling out a psychiatric hold be inappropriate for Ms. Q? What clinical factors and legal issues should a psychiatrist consider when helping medical colleagues provide unwanted treatment to a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder? We’ll explore these matters as we consider the case of Ms. Q (Figure) and the following questions:

- What type of care is most appropriate for her now?

- Can she refuse medical treatment?

- What are the medicolegal risks of letting her leave the hospital?

- What are the medicolegal risks of detaining and force-feeding her against her will?

- When is a psychiatric “hold” appropriate?

What care is appropriate?

Given her state of self-starvation, Ms. Q’s treatment plan could require close monitoring of her electrolytes and cardiac status, as well as watching her for signs of “refeeding syndrome”—rapid, potentially fatal fluid shifts and metabolic derangements that malnourished patients could experience when they receive artificial refeeding.1

First, the physicians who are caring for Ms. Q should determine whether she needs more intensive medical supervision than is usually available on a psychiatric unit. If she does, but she won’t agree to stay on a medical unit for care, a psychiatric hold is the wrong step, for 2 reasons:

- Once a psychiatric hold has been executed, state statutes require the patient to be placed in a psychiatric facility—a state-approved psychiatric treatment setting, such as a psychiatric unit or free-standing psychiatric hospital—within a specified period.2,3 Most nonpsychiatric medical units would not meet state’s statutory definition for such a facility.

- A psychiatric hold only permits short-term detention. It does not provide legal authority to impose unwanted medical treatment.

Does Ms. Q have capacity?

In the United States, Ms. Q has a legal right to refuse medical care—even if she needs it urgently—provided that her refusal is made competently.4 As Appelbaum and Grisso5 explained in a now-classic 1988 article:

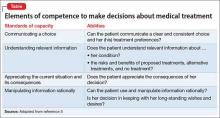

The legal standards for competence include the four related skills of communicating a choice, understanding relevant information, appreciating the current situation and its consequences, and manipulating information rationally.

The Table5 describes these abilities in more detail.

Only courts can make legal determinations of competence, so physicians refer to an evaluation of a patient’s competence-related abilities as a “capacity assessment.” The decision as to whether a patient has capacity ultimately rests with the primary treatment team; however, physicians in other specialties often enlist psychiatrists’ help with this matter because of their interviewing skills and knowledge of how mental illness can impair capacity.

No easy-to-use instrument for evaluating capacity is available. However, Appelbaum6 provides examples of questions that often prove useful in such assessments, and a review by Sessums et al7 on several capacity evaluation tools suggests that the Aid to Capacity Evaluation8 may be the best instrument for performing capacity assessments.

Patients with anorexia nervosa often differ substantially from healthy people in how they assign values to life and death,9 which can make it difficult to evaluate their capacity to refuse life-saving treatment. Malnutrition can alter patients’ ability to think clearly, a phenomenon that some patients with anorexia mention as a reason they are grateful (in retrospect) for the compulsory treatment they received.10 Yet, if an evaluation shows that the patient has the decision-making capacity to refuse care, then her (his) caregivers should carefully document this conclusion and the basis for it. Although caregivers might encourage her to accept the treatment they believe she needs, they should not provide treatment that conflicts with their patient’s wishes.

If evaluation shows that the patient lacks capacity, however, the findings that support this conclusion should be documented clearly. The team then should consult the hospital attorney to determine how to best proceed. The attorney might recommend that a physician on the primary treatment team initiate a “medical hold”—an order that the patient may not leave against medical advice (AMA)—and then seek an emergency guardianship to permit medical treatment, such as refeeding.

To treat or not to treat?

What are the legal risks of allowing Ms. Q to leave AMA before she reaches medical stability?

Powers and Cloak11 describe a case of a 26-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa who came to the hospital with dizziness, weakness, and a very low blood glucose level. She was discharged after 6 days without having received any feeding, only to return to the emergency department 2 days later. This time, she had a letter from her physician stating that she needed medical supervision to start refeeding, yet she was discharged from the emergency department within a few hours. She was re-admitted to the hospital the next day.

Powers and Cloak11 do not report this woman’s medical outcome. But what if she had suffered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia before her third presentation to the emergency department or suffered another injury attributable to her nutritional state: Could her physicians be found at fault?

On Cohen & Associates’ Web site, they essentially answer, “Yes.” They describe a case of “Miss McIntosh,” who had anorexia nervosa and was discharged home from a hospital despite “chronic metabolic problems and not eating properly.” She went into a “hypoglycemic encephalopathic coma” and “suffered irreversible brain damage.” A subsequent lawsuit against the hospital resulted in a 7-figure settlement,12 illustrating the potential for adverse medicolegal consequences if failure to treat a patient with anorexia nervosa could be linked to subsequent physical harm. On the other hand, could a patient with anorexia who is being force-fed take legal action against her providers? At least 3 recent British cases suggest that this is possible.13-15 A British medical student with anorexia, E, made an emergency application to the Court of Protection in London, claiming that being fed against her will was akin to reliving her past experience of sexual abuse. In E’s case, the judge ruled “that the balance tips slowly but unmistakably in the direction of life preserving treatment” and authorized feeding over her objection.6 In 2 other cases, however, British courts have ruled that force-feeding anorexic patients would be futile and disallowed the practice.14,15

Faced with possible legal action, no matter what course you take, how should you respond? Getting legal and ethical consultation is prudent if time allows. In many cases, hospital attorneys might prefer that physicians err on the side of preserving life(D. Vanderpool, MBA, JD, personal communication, February 3, 2016)—even if that means detaining a patient without clear legal authorization to do so—because attorneys would prefer to defend a doctor who acted to save someone’s life than to defend a doctor who knowingly allowed a patient to die.

When might persons with an eating disorder be civilly committed?

Suppose that Ms. Q does not need urgent nonpsychiatric medical care, or that her life-threatening physical problems now have been addressed. Her physicians strongly recommend that she undergo inpatient psychiatric treatment for her eating disorder, but she wants to leave. Would it now be appropriate to fill out paperwork to initiate a psychiatric hold?

All U.S. jurisdictions authorize “civil commitment” proceedings that can lead to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization of people who have a mental disorder and pose a risk to themselves or others because of the disorder.16

In general, to be subject to civil commitment, a person must have a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory. In addition, that disorder must grossly impair her (his) judgment, behavior, reality testing, or ability to meet the demands of everyday life.17

People with psychosis, a severe mood disorder, or dementia often meet these criteria. However, psychiatrists do not usually consider anorexia nervosa to be a thought disorder, mood disorder, or memory disorder. Does this mean that people with anorexia nervosa cannot meet the “substantial” mental disorder criterion?

It does not. Courts interpret the words in statutes based on their “ordinary and natural meaning.”18 If Ms. Q perceived herself as fat, despite having a BMI that was far below the healthy range, most people would regard her thinking to be disordered. If, in addition, her mental disorder impaired her “judgment, behavior, and capacity to meet the ordinary demands of sustaining existence,” then her anorexia nervosa “would qualify as a mental disorder for commitment purposes.”19

To be subject to civil commitment, a person with a substantial mental disorder also must pose a risk of harm to herself or others because of the disorder. That risk can be evidenced via an action, attempt, or threat to do direct physical harm, or it might inhere in the potential for developing grave disability through neglect of one’s basic needs, such as failing to eat adequately. In Ms. Q’s case, if the evidence shows her eating-disordered behavior has placed her at imminent risk of permanent injury or death, she has satisfied the legal criteria that justify court-ordered psychiatric hospitalization.

Bottom Line

When a severely malnourished patient with anorexia nervosa does not agree to allow recommended care, an appropriate clinical response should include judgment about the urgency of the proposed treatment, what treatment setting is best suited to the patient’s condition, and whether the patient has the mental capacity to refuse potentially life-saving care.

1. Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1495-1498.

2. Ohio Revised Code §5122.01(F).

3. Oregon Revised Statutes §426.005(c).

4. Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (N1914).

5. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

6. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

7. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

8. Community tools: Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE). University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. http://www.jcb.utoronto.ca/tools/ace_download.shtml. Updated May 8, 2008. Accessed December 21, 2015.

9. Tan J, Hope T, Stewart A. Competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26(6):697-707.

10. Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, et al. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):845-852.

11. Powers PS, Cloak NL. Failure to feed patients with anorexia nervosa and other perils and perplexities in the medical care of eating disorder patients. Eat Disord. 2013;21(1):81-89.

12. “Failure to properly treat anorexia nervosa.” Harry S. Cohen & Associates. http://medmal1.com/article/failure-to-properly-treat-anorexia-nervosa. Accessed February 1, 2016.

13. A Local Authority v E. and Others [2012] EWHC 1639 (COP).

14. A NHS Foundation Trust v Ms. X [2014] EWCOP 35.

15. NHS Trust v L [2012] EWHC 2741 (COP).

16. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

17. Castellano-Hoyt DW. Enhancing police response to persons in mental health crisis: providing strategies, communication techniques, and crisis intervention preparation in overcoming institutional challenges. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 2003.

18. FDIC v Meyer, 510 U.S. 471 (1994).

19. Appelbaum PS, Rumpf T. Civil commitment of the anorexic patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(4):225-230.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the general hospital where I perform consultations, the medical service asked me to fill out psychiatric “hold” documents to keep a severely malnourished young woman with anorexia nervosa from leaving the hospital. Ms. Q, whose body mass index (BMI) was 12 (yes, 12), came to the hospital to have her “electrolytes fixed.” She was willing to stay the night for electrolyte repletion, but insisted she could gain weight on her own at home.

I’m worried that she might die without prompt inpatient treatment; she needs to stay on the medical service. Should I fill out a psychiatric hold to keep her there? What legal risks could I face if Ms. Q is detained and force-fed against her will? What are the legal risks of letting her leave the hospital before she is medically stable?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

When a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder arrives on a medical floor, treatment teams often ask psychiatric consultants to help them impose care the patient desperately needs but doesn’t want. This reaction is understandable. After all, an eating disorder is a psychiatric illness, and hospital-based psychiatrists have experience with treating involuntary patients. A psychiatric hold may seem like a sensible way to save the life of a hospitalized patient with a mental illness.

But filling out a psychiatric hold only scratches the surface of what a psychiatric consultant’s contribution should include; in Ms. Q’s case, initiating a psychiatric hold is probably the wrong thing to do.

Why would filling out a psychiatric hold be inappropriate for Ms. Q? What clinical factors and legal issues should a psychiatrist consider when helping medical colleagues provide unwanted treatment to a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder? We’ll explore these matters as we consider the case of Ms. Q (Figure) and the following questions:

- What type of care is most appropriate for her now?

- Can she refuse medical treatment?

- What are the medicolegal risks of letting her leave the hospital?

- What are the medicolegal risks of detaining and force-feeding her against her will?

- When is a psychiatric “hold” appropriate?

What care is appropriate?

Given her state of self-starvation, Ms. Q’s treatment plan could require close monitoring of her electrolytes and cardiac status, as well as watching her for signs of “refeeding syndrome”—rapid, potentially fatal fluid shifts and metabolic derangements that malnourished patients could experience when they receive artificial refeeding.1

First, the physicians who are caring for Ms. Q should determine whether she needs more intensive medical supervision than is usually available on a psychiatric unit. If she does, but she won’t agree to stay on a medical unit for care, a psychiatric hold is the wrong step, for 2 reasons:

- Once a psychiatric hold has been executed, state statutes require the patient to be placed in a psychiatric facility—a state-approved psychiatric treatment setting, such as a psychiatric unit or free-standing psychiatric hospital—within a specified period.2,3 Most nonpsychiatric medical units would not meet state’s statutory definition for such a facility.

- A psychiatric hold only permits short-term detention. It does not provide legal authority to impose unwanted medical treatment.

Does Ms. Q have capacity?

In the United States, Ms. Q has a legal right to refuse medical care—even if she needs it urgently—provided that her refusal is made competently.4 As Appelbaum and Grisso5 explained in a now-classic 1988 article:

The legal standards for competence include the four related skills of communicating a choice, understanding relevant information, appreciating the current situation and its consequences, and manipulating information rationally.

The Table5 describes these abilities in more detail.

Only courts can make legal determinations of competence, so physicians refer to an evaluation of a patient’s competence-related abilities as a “capacity assessment.” The decision as to whether a patient has capacity ultimately rests with the primary treatment team; however, physicians in other specialties often enlist psychiatrists’ help with this matter because of their interviewing skills and knowledge of how mental illness can impair capacity.

No easy-to-use instrument for evaluating capacity is available. However, Appelbaum6 provides examples of questions that often prove useful in such assessments, and a review by Sessums et al7 on several capacity evaluation tools suggests that the Aid to Capacity Evaluation8 may be the best instrument for performing capacity assessments.

Patients with anorexia nervosa often differ substantially from healthy people in how they assign values to life and death,9 which can make it difficult to evaluate their capacity to refuse life-saving treatment. Malnutrition can alter patients’ ability to think clearly, a phenomenon that some patients with anorexia mention as a reason they are grateful (in retrospect) for the compulsory treatment they received.10 Yet, if an evaluation shows that the patient has the decision-making capacity to refuse care, then her (his) caregivers should carefully document this conclusion and the basis for it. Although caregivers might encourage her to accept the treatment they believe she needs, they should not provide treatment that conflicts with their patient’s wishes.

If evaluation shows that the patient lacks capacity, however, the findings that support this conclusion should be documented clearly. The team then should consult the hospital attorney to determine how to best proceed. The attorney might recommend that a physician on the primary treatment team initiate a “medical hold”—an order that the patient may not leave against medical advice (AMA)—and then seek an emergency guardianship to permit medical treatment, such as refeeding.

To treat or not to treat?

What are the legal risks of allowing Ms. Q to leave AMA before she reaches medical stability?

Powers and Cloak11 describe a case of a 26-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa who came to the hospital with dizziness, weakness, and a very low blood glucose level. She was discharged after 6 days without having received any feeding, only to return to the emergency department 2 days later. This time, she had a letter from her physician stating that she needed medical supervision to start refeeding, yet she was discharged from the emergency department within a few hours. She was re-admitted to the hospital the next day.

Powers and Cloak11 do not report this woman’s medical outcome. But what if she had suffered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia before her third presentation to the emergency department or suffered another injury attributable to her nutritional state: Could her physicians be found at fault?

On Cohen & Associates’ Web site, they essentially answer, “Yes.” They describe a case of “Miss McIntosh,” who had anorexia nervosa and was discharged home from a hospital despite “chronic metabolic problems and not eating properly.” She went into a “hypoglycemic encephalopathic coma” and “suffered irreversible brain damage.” A subsequent lawsuit against the hospital resulted in a 7-figure settlement,12 illustrating the potential for adverse medicolegal consequences if failure to treat a patient with anorexia nervosa could be linked to subsequent physical harm. On the other hand, could a patient with anorexia who is being force-fed take legal action against her providers? At least 3 recent British cases suggest that this is possible.13-15 A British medical student with anorexia, E, made an emergency application to the Court of Protection in London, claiming that being fed against her will was akin to reliving her past experience of sexual abuse. In E’s case, the judge ruled “that the balance tips slowly but unmistakably in the direction of life preserving treatment” and authorized feeding over her objection.6 In 2 other cases, however, British courts have ruled that force-feeding anorexic patients would be futile and disallowed the practice.14,15

Faced with possible legal action, no matter what course you take, how should you respond? Getting legal and ethical consultation is prudent if time allows. In many cases, hospital attorneys might prefer that physicians err on the side of preserving life(D. Vanderpool, MBA, JD, personal communication, February 3, 2016)—even if that means detaining a patient without clear legal authorization to do so—because attorneys would prefer to defend a doctor who acted to save someone’s life than to defend a doctor who knowingly allowed a patient to die.

When might persons with an eating disorder be civilly committed?

Suppose that Ms. Q does not need urgent nonpsychiatric medical care, or that her life-threatening physical problems now have been addressed. Her physicians strongly recommend that she undergo inpatient psychiatric treatment for her eating disorder, but she wants to leave. Would it now be appropriate to fill out paperwork to initiate a psychiatric hold?

All U.S. jurisdictions authorize “civil commitment” proceedings that can lead to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization of people who have a mental disorder and pose a risk to themselves or others because of the disorder.16

In general, to be subject to civil commitment, a person must have a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory. In addition, that disorder must grossly impair her (his) judgment, behavior, reality testing, or ability to meet the demands of everyday life.17

People with psychosis, a severe mood disorder, or dementia often meet these criteria. However, psychiatrists do not usually consider anorexia nervosa to be a thought disorder, mood disorder, or memory disorder. Does this mean that people with anorexia nervosa cannot meet the “substantial” mental disorder criterion?

It does not. Courts interpret the words in statutes based on their “ordinary and natural meaning.”18 If Ms. Q perceived herself as fat, despite having a BMI that was far below the healthy range, most people would regard her thinking to be disordered. If, in addition, her mental disorder impaired her “judgment, behavior, and capacity to meet the ordinary demands of sustaining existence,” then her anorexia nervosa “would qualify as a mental disorder for commitment purposes.”19

To be subject to civil commitment, a person with a substantial mental disorder also must pose a risk of harm to herself or others because of the disorder. That risk can be evidenced via an action, attempt, or threat to do direct physical harm, or it might inhere in the potential for developing grave disability through neglect of one’s basic needs, such as failing to eat adequately. In Ms. Q’s case, if the evidence shows her eating-disordered behavior has placed her at imminent risk of permanent injury or death, she has satisfied the legal criteria that justify court-ordered psychiatric hospitalization.

Bottom Line

When a severely malnourished patient with anorexia nervosa does not agree to allow recommended care, an appropriate clinical response should include judgment about the urgency of the proposed treatment, what treatment setting is best suited to the patient’s condition, and whether the patient has the mental capacity to refuse potentially life-saving care.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the general hospital where I perform consultations, the medical service asked me to fill out psychiatric “hold” documents to keep a severely malnourished young woman with anorexia nervosa from leaving the hospital. Ms. Q, whose body mass index (BMI) was 12 (yes, 12), came to the hospital to have her “electrolytes fixed.” She was willing to stay the night for electrolyte repletion, but insisted she could gain weight on her own at home.

I’m worried that she might die without prompt inpatient treatment; she needs to stay on the medical service. Should I fill out a psychiatric hold to keep her there? What legal risks could I face if Ms. Q is detained and force-fed against her will? What are the legal risks of letting her leave the hospital before she is medically stable?

Submitted by “Dr. F”

When a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder arrives on a medical floor, treatment teams often ask psychiatric consultants to help them impose care the patient desperately needs but doesn’t want. This reaction is understandable. After all, an eating disorder is a psychiatric illness, and hospital-based psychiatrists have experience with treating involuntary patients. A psychiatric hold may seem like a sensible way to save the life of a hospitalized patient with a mental illness.

But filling out a psychiatric hold only scratches the surface of what a psychiatric consultant’s contribution should include; in Ms. Q’s case, initiating a psychiatric hold is probably the wrong thing to do.

Why would filling out a psychiatric hold be inappropriate for Ms. Q? What clinical factors and legal issues should a psychiatrist consider when helping medical colleagues provide unwanted treatment to a severely malnourished patient with an eating disorder? We’ll explore these matters as we consider the case of Ms. Q (Figure) and the following questions:

- What type of care is most appropriate for her now?

- Can she refuse medical treatment?

- What are the medicolegal risks of letting her leave the hospital?

- What are the medicolegal risks of detaining and force-feeding her against her will?

- When is a psychiatric “hold” appropriate?

What care is appropriate?

Given her state of self-starvation, Ms. Q’s treatment plan could require close monitoring of her electrolytes and cardiac status, as well as watching her for signs of “refeeding syndrome”—rapid, potentially fatal fluid shifts and metabolic derangements that malnourished patients could experience when they receive artificial refeeding.1

First, the physicians who are caring for Ms. Q should determine whether she needs more intensive medical supervision than is usually available on a psychiatric unit. If she does, but she won’t agree to stay on a medical unit for care, a psychiatric hold is the wrong step, for 2 reasons:

- Once a psychiatric hold has been executed, state statutes require the patient to be placed in a psychiatric facility—a state-approved psychiatric treatment setting, such as a psychiatric unit or free-standing psychiatric hospital—within a specified period.2,3 Most nonpsychiatric medical units would not meet state’s statutory definition for such a facility.

- A psychiatric hold only permits short-term detention. It does not provide legal authority to impose unwanted medical treatment.

Does Ms. Q have capacity?

In the United States, Ms. Q has a legal right to refuse medical care—even if she needs it urgently—provided that her refusal is made competently.4 As Appelbaum and Grisso5 explained in a now-classic 1988 article:

The legal standards for competence include the four related skills of communicating a choice, understanding relevant information, appreciating the current situation and its consequences, and manipulating information rationally.

The Table5 describes these abilities in more detail.

Only courts can make legal determinations of competence, so physicians refer to an evaluation of a patient’s competence-related abilities as a “capacity assessment.” The decision as to whether a patient has capacity ultimately rests with the primary treatment team; however, physicians in other specialties often enlist psychiatrists’ help with this matter because of their interviewing skills and knowledge of how mental illness can impair capacity.

No easy-to-use instrument for evaluating capacity is available. However, Appelbaum6 provides examples of questions that often prove useful in such assessments, and a review by Sessums et al7 on several capacity evaluation tools suggests that the Aid to Capacity Evaluation8 may be the best instrument for performing capacity assessments.

Patients with anorexia nervosa often differ substantially from healthy people in how they assign values to life and death,9 which can make it difficult to evaluate their capacity to refuse life-saving treatment. Malnutrition can alter patients’ ability to think clearly, a phenomenon that some patients with anorexia mention as a reason they are grateful (in retrospect) for the compulsory treatment they received.10 Yet, if an evaluation shows that the patient has the decision-making capacity to refuse care, then her (his) caregivers should carefully document this conclusion and the basis for it. Although caregivers might encourage her to accept the treatment they believe she needs, they should not provide treatment that conflicts with their patient’s wishes.

If evaluation shows that the patient lacks capacity, however, the findings that support this conclusion should be documented clearly. The team then should consult the hospital attorney to determine how to best proceed. The attorney might recommend that a physician on the primary treatment team initiate a “medical hold”—an order that the patient may not leave against medical advice (AMA)—and then seek an emergency guardianship to permit medical treatment, such as refeeding.

To treat or not to treat?

What are the legal risks of allowing Ms. Q to leave AMA before she reaches medical stability?

Powers and Cloak11 describe a case of a 26-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa who came to the hospital with dizziness, weakness, and a very low blood glucose level. She was discharged after 6 days without having received any feeding, only to return to the emergency department 2 days later. This time, she had a letter from her physician stating that she needed medical supervision to start refeeding, yet she was discharged from the emergency department within a few hours. She was re-admitted to the hospital the next day.

Powers and Cloak11 do not report this woman’s medical outcome. But what if she had suffered a fatal cardiac arrhythmia before her third presentation to the emergency department or suffered another injury attributable to her nutritional state: Could her physicians be found at fault?

On Cohen & Associates’ Web site, they essentially answer, “Yes.” They describe a case of “Miss McIntosh,” who had anorexia nervosa and was discharged home from a hospital despite “chronic metabolic problems and not eating properly.” She went into a “hypoglycemic encephalopathic coma” and “suffered irreversible brain damage.” A subsequent lawsuit against the hospital resulted in a 7-figure settlement,12 illustrating the potential for adverse medicolegal consequences if failure to treat a patient with anorexia nervosa could be linked to subsequent physical harm. On the other hand, could a patient with anorexia who is being force-fed take legal action against her providers? At least 3 recent British cases suggest that this is possible.13-15 A British medical student with anorexia, E, made an emergency application to the Court of Protection in London, claiming that being fed against her will was akin to reliving her past experience of sexual abuse. In E’s case, the judge ruled “that the balance tips slowly but unmistakably in the direction of life preserving treatment” and authorized feeding over her objection.6 In 2 other cases, however, British courts have ruled that force-feeding anorexic patients would be futile and disallowed the practice.14,15

Faced with possible legal action, no matter what course you take, how should you respond? Getting legal and ethical consultation is prudent if time allows. In many cases, hospital attorneys might prefer that physicians err on the side of preserving life(D. Vanderpool, MBA, JD, personal communication, February 3, 2016)—even if that means detaining a patient without clear legal authorization to do so—because attorneys would prefer to defend a doctor who acted to save someone’s life than to defend a doctor who knowingly allowed a patient to die.

When might persons with an eating disorder be civilly committed?

Suppose that Ms. Q does not need urgent nonpsychiatric medical care, or that her life-threatening physical problems now have been addressed. Her physicians strongly recommend that she undergo inpatient psychiatric treatment for her eating disorder, but she wants to leave. Would it now be appropriate to fill out paperwork to initiate a psychiatric hold?

All U.S. jurisdictions authorize “civil commitment” proceedings that can lead to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization of people who have a mental disorder and pose a risk to themselves or others because of the disorder.16

In general, to be subject to civil commitment, a person must have a substantial disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation, or memory. In addition, that disorder must grossly impair her (his) judgment, behavior, reality testing, or ability to meet the demands of everyday life.17

People with psychosis, a severe mood disorder, or dementia often meet these criteria. However, psychiatrists do not usually consider anorexia nervosa to be a thought disorder, mood disorder, or memory disorder. Does this mean that people with anorexia nervosa cannot meet the “substantial” mental disorder criterion?

It does not. Courts interpret the words in statutes based on their “ordinary and natural meaning.”18 If Ms. Q perceived herself as fat, despite having a BMI that was far below the healthy range, most people would regard her thinking to be disordered. If, in addition, her mental disorder impaired her “judgment, behavior, and capacity to meet the ordinary demands of sustaining existence,” then her anorexia nervosa “would qualify as a mental disorder for commitment purposes.”19

To be subject to civil commitment, a person with a substantial mental disorder also must pose a risk of harm to herself or others because of the disorder. That risk can be evidenced via an action, attempt, or threat to do direct physical harm, or it might inhere in the potential for developing grave disability through neglect of one’s basic needs, such as failing to eat adequately. In Ms. Q’s case, if the evidence shows her eating-disordered behavior has placed her at imminent risk of permanent injury or death, she has satisfied the legal criteria that justify court-ordered psychiatric hospitalization.

Bottom Line

When a severely malnourished patient with anorexia nervosa does not agree to allow recommended care, an appropriate clinical response should include judgment about the urgency of the proposed treatment, what treatment setting is best suited to the patient’s condition, and whether the patient has the mental capacity to refuse potentially life-saving care.

1. Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1495-1498.

2. Ohio Revised Code §5122.01(F).

3. Oregon Revised Statutes §426.005(c).

4. Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (N1914).

5. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

6. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

7. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

8. Community tools: Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE). University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. http://www.jcb.utoronto.ca/tools/ace_download.shtml. Updated May 8, 2008. Accessed December 21, 2015.

9. Tan J, Hope T, Stewart A. Competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26(6):697-707.

10. Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, et al. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):845-852.

11. Powers PS, Cloak NL. Failure to feed patients with anorexia nervosa and other perils and perplexities in the medical care of eating disorder patients. Eat Disord. 2013;21(1):81-89.

12. “Failure to properly treat anorexia nervosa.” Harry S. Cohen & Associates. http://medmal1.com/article/failure-to-properly-treat-anorexia-nervosa. Accessed February 1, 2016.

13. A Local Authority v E. and Others [2012] EWHC 1639 (COP).

14. A NHS Foundation Trust v Ms. X [2014] EWCOP 35.

15. NHS Trust v L [2012] EWHC 2741 (COP).

16. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

17. Castellano-Hoyt DW. Enhancing police response to persons in mental health crisis: providing strategies, communication techniques, and crisis intervention preparation in overcoming institutional challenges. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 2003.

18. FDIC v Meyer, 510 U.S. 471 (1994).

19. Appelbaum PS, Rumpf T. Civil commitment of the anorexic patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(4):225-230.

1. Mehanna HM, Moledina J, Travis J. Refeeding syndrome: what it is, and how to prevent and treat it. BMJ. 2008;336(7659):1495-1498.

2. Ohio Revised Code §5122.01(F).

3. Oregon Revised Statutes §426.005(c).

4. Schloendorff v Society of New York Hospital, 211 N.Y. 125, 105 N.E. 92 (N1914).

5. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

6. Appelbaum PS. Clinical practice. Assessment of patients’ competence to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(18):1834-1840.

7. Sessums LL, Zembrzuska H, Jackson JL. Does this patient have medical decision-making capacity? JAMA. 2011;306(4):420-427.

8. Community tools: Aid to Capacity Evaluation (ACE). University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics. http://www.jcb.utoronto.ca/tools/ace_download.shtml. Updated May 8, 2008. Accessed December 21, 2015.

9. Tan J, Hope T, Stewart A. Competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2003;26(6):697-707.

10. Elzakkers IF, Danner UN, Hoek HW, et al. Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(8):845-852.

11. Powers PS, Cloak NL. Failure to feed patients with anorexia nervosa and other perils and perplexities in the medical care of eating disorder patients. Eat Disord. 2013;21(1):81-89.

12. “Failure to properly treat anorexia nervosa.” Harry S. Cohen & Associates. http://medmal1.com/article/failure-to-properly-treat-anorexia-nervosa. Accessed February 1, 2016.

13. A Local Authority v E. and Others [2012] EWHC 1639 (COP).

14. A NHS Foundation Trust v Ms. X [2014] EWCOP 35.

15. NHS Trust v L [2012] EWHC 2741 (COP).

16. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for civil commitment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011.

17. Castellano-Hoyt DW. Enhancing police response to persons in mental health crisis: providing strategies, communication techniques, and crisis intervention preparation in overcoming institutional challenges. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, Ltd; 2003.

18. FDIC v Meyer, 510 U.S. 471 (1994).

19. Appelbaum PS, Rumpf T. Civil commitment of the anorexic patient. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20(4):225-230.

VIDEO: Progressive MS trial failures provide lessons for future success

NEW ORLEANS – Findings last year from the ORATORIO trial showed for the first time that a pharmaceutical agent – ocrelizumab – was effective for slowing the rate of progression in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, but there is as much to learn from the many failed trials and treatments as from this recent success, according to experts at a meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“Insofar as we have seen failure after failure in studying progressive MS, we’ve also learned from the studies themselves how best to redesign the studies and how to target the right kind of patients to be able to see a therapeutic effect once that appropriate drug came along,” Dr. John Rinker II said in an interview at the meeting sponsored by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Dr. Rinker of the University of Alabama at Birmingham chaired a session on “the treatment pipeline” in MS, and noted in the interview that the lessons learned from failed trials could potentially be used to “re-look at some of these older drugs that had been failures in the past and, using a different trial methodology, maybe find some success in the future.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Findings last year from the ORATORIO trial showed for the first time that a pharmaceutical agent – ocrelizumab – was effective for slowing the rate of progression in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, but there is as much to learn from the many failed trials and treatments as from this recent success, according to experts at a meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“Insofar as we have seen failure after failure in studying progressive MS, we’ve also learned from the studies themselves how best to redesign the studies and how to target the right kind of patients to be able to see a therapeutic effect once that appropriate drug came along,” Dr. John Rinker II said in an interview at the meeting sponsored by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Dr. Rinker of the University of Alabama at Birmingham chaired a session on “the treatment pipeline” in MS, and noted in the interview that the lessons learned from failed trials could potentially be used to “re-look at some of these older drugs that had been failures in the past and, using a different trial methodology, maybe find some success in the future.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Findings last year from the ORATORIO trial showed for the first time that a pharmaceutical agent – ocrelizumab – was effective for slowing the rate of progression in patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis, but there is as much to learn from the many failed trials and treatments as from this recent success, according to experts at a meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

“Insofar as we have seen failure after failure in studying progressive MS, we’ve also learned from the studies themselves how best to redesign the studies and how to target the right kind of patients to be able to see a therapeutic effect once that appropriate drug came along,” Dr. John Rinker II said in an interview at the meeting sponsored by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Dr. Rinker of the University of Alabama at Birmingham chaired a session on “the treatment pipeline” in MS, and noted in the interview that the lessons learned from failed trials could potentially be used to “re-look at some of these older drugs that had been failures in the past and, using a different trial methodology, maybe find some success in the future.”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ACTRIMS Forum 2016

A tool to assess behavioral problems in neurocognitive disorder and guide treatment

Non-drug treatment options, such as behavioral techniques and environment adjustment, should be considered before initiating pharmacotherapy in older patients with behavioral deregulation caused by a neurocognitive disorder. Before considering any interventions, including medical therapy, an evaluation and development of a profile of behavioral symptoms is warranted.

The purpose of such a profile is to:

- guide a patient-specific treatment plan

- measure treatment response (whether medication-related or otherwise).

Developing a profile for a patient can lead to a more tailored treatment plan. Such a plan includes identification of mitigating factors for the patient’s behavior and use of specific interventions, with a preference for non-medication interventions.

Profile assessment can guide treatment

The disruptive-behavior profile that I created (Table) can be used as an initial screening device; the score (1 through 4) in each domain indicates the intensity of intervention required. The profile also can be used to evaluate treatment response.

For example, when caring for a person with a neurocognitive disorder with agitation and disruptive behavior, this profile can be used by the caregiver as a reporting tool for the behavioral heath professional providing consultation. Based on this report, the behavioral health professional can evaluate the predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors of the behavioral disturbance, and a treatment plan can be implemented. After interventions are applied, follow-up assessment with the tool can assess the response to the intervention.

The scale can aid in averting overuse of non-specific medication therapy and, if required, can guide pharmacotherapy. This assessment tool can be useful for clinicians providing care for patients with a neurocognitive disorder, not only in choosing treatment, but also to justify clinical rationale.

How does this scale compare with others?

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease (Behave-AD), Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, and Brief Agitation Rating Scale provide valuable information for clinical care. However:

- Use of the NPI in everyday practice is limited; time spent completing the NPI scale remains a significant impediment for the busy clinician.

- Behave-AD requires a higher level of skill for some caregivers to estimate behavioral symptoms and answer questions about severity.

- Cohen-Mansfeld and Brief Agitation Rating Scale provide a limited description of the intensity of behavioral disturbance.

Developing a treatment plan and justifying pharmacotherapy in patients with a neurocognitive disorder is a challenge for clinicians. The scale that I developed aims to (1) assist the busy clinician who must construct a targeted treatment plan and (2) avoid pharmacotherapy when it is unnecessary. If pharmacotherapy is warranted on the basis of any of the domain scores in the profile, it should be documented with a judicious rationale.

Non-drug treatment options, such as behavioral techniques and environment adjustment, should be considered before initiating pharmacotherapy in older patients with behavioral deregulation caused by a neurocognitive disorder. Before considering any interventions, including medical therapy, an evaluation and development of a profile of behavioral symptoms is warranted.

The purpose of such a profile is to:

- guide a patient-specific treatment plan

- measure treatment response (whether medication-related or otherwise).

Developing a profile for a patient can lead to a more tailored treatment plan. Such a plan includes identification of mitigating factors for the patient’s behavior and use of specific interventions, with a preference for non-medication interventions.

Profile assessment can guide treatment

The disruptive-behavior profile that I created (Table) can be used as an initial screening device; the score (1 through 4) in each domain indicates the intensity of intervention required. The profile also can be used to evaluate treatment response.

For example, when caring for a person with a neurocognitive disorder with agitation and disruptive behavior, this profile can be used by the caregiver as a reporting tool for the behavioral heath professional providing consultation. Based on this report, the behavioral health professional can evaluate the predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors of the behavioral disturbance, and a treatment plan can be implemented. After interventions are applied, follow-up assessment with the tool can assess the response to the intervention.

The scale can aid in averting overuse of non-specific medication therapy and, if required, can guide pharmacotherapy. This assessment tool can be useful for clinicians providing care for patients with a neurocognitive disorder, not only in choosing treatment, but also to justify clinical rationale.

How does this scale compare with others?

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease (Behave-AD), Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, and Brief Agitation Rating Scale provide valuable information for clinical care. However:

- Use of the NPI in everyday practice is limited; time spent completing the NPI scale remains a significant impediment for the busy clinician.

- Behave-AD requires a higher level of skill for some caregivers to estimate behavioral symptoms and answer questions about severity.

- Cohen-Mansfeld and Brief Agitation Rating Scale provide a limited description of the intensity of behavioral disturbance.

Developing a treatment plan and justifying pharmacotherapy in patients with a neurocognitive disorder is a challenge for clinicians. The scale that I developed aims to (1) assist the busy clinician who must construct a targeted treatment plan and (2) avoid pharmacotherapy when it is unnecessary. If pharmacotherapy is warranted on the basis of any of the domain scores in the profile, it should be documented with a judicious rationale.

Non-drug treatment options, such as behavioral techniques and environment adjustment, should be considered before initiating pharmacotherapy in older patients with behavioral deregulation caused by a neurocognitive disorder. Before considering any interventions, including medical therapy, an evaluation and development of a profile of behavioral symptoms is warranted.

The purpose of such a profile is to:

- guide a patient-specific treatment plan

- measure treatment response (whether medication-related or otherwise).

Developing a profile for a patient can lead to a more tailored treatment plan. Such a plan includes identification of mitigating factors for the patient’s behavior and use of specific interventions, with a preference for non-medication interventions.

Profile assessment can guide treatment

The disruptive-behavior profile that I created (Table) can be used as an initial screening device; the score (1 through 4) in each domain indicates the intensity of intervention required. The profile also can be used to evaluate treatment response.

For example, when caring for a person with a neurocognitive disorder with agitation and disruptive behavior, this profile can be used by the caregiver as a reporting tool for the behavioral heath professional providing consultation. Based on this report, the behavioral health professional can evaluate the predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors of the behavioral disturbance, and a treatment plan can be implemented. After interventions are applied, follow-up assessment with the tool can assess the response to the intervention.

The scale can aid in averting overuse of non-specific medication therapy and, if required, can guide pharmacotherapy. This assessment tool can be useful for clinicians providing care for patients with a neurocognitive disorder, not only in choosing treatment, but also to justify clinical rationale.

How does this scale compare with others?

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI), Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease (Behave-AD), Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, and Brief Agitation Rating Scale provide valuable information for clinical care. However:

- Use of the NPI in everyday practice is limited; time spent completing the NPI scale remains a significant impediment for the busy clinician.

- Behave-AD requires a higher level of skill for some caregivers to estimate behavioral symptoms and answer questions about severity.

- Cohen-Mansfeld and Brief Agitation Rating Scale provide a limited description of the intensity of behavioral disturbance.

Developing a treatment plan and justifying pharmacotherapy in patients with a neurocognitive disorder is a challenge for clinicians. The scale that I developed aims to (1) assist the busy clinician who must construct a targeted treatment plan and (2) avoid pharmacotherapy when it is unnecessary. If pharmacotherapy is warranted on the basis of any of the domain scores in the profile, it should be documented with a judicious rationale.

Brian Sandroff, PhD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

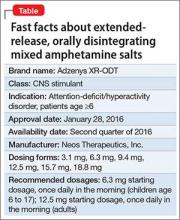

Extended-release, orally disintegrating mixed amphetamine salts for ADHD: New formulation

An amphetamine-based, extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for patients age ≥6 diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) won FDA approval on January 28, 2016 (Table).1

Adzenys XR-ODT is the first extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for ADHD, Neos Therapeutics, Inc. the drug’s manufacturer, said in a statement.2 The newly approved agent is bioequivalent to Adderall XR (the capsule form of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts), and patients taking Adderall XR can be switched to the new drug. Equivalent dosages of the 2 drugs are outlined on the prescribing information.1

“The novel features of an extended-release orally disintegrating tablet ... make Adzenys XR-ODT attractive for use in both children (6 and older) and adults,” Alice R. Mao, MD, Medical Director, Memorial Park Psychiatry, Houston, Texas, said in the statement.2

As a condition of the approval, Neos must annually report the status of 3 post-marketing studies of children diagnosed with ADHD taking Adzenys XR-ODT, according to the approval letter.2 One is a single-dose, open-label study of children ages 4 and 5; the second is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled titration study of children ages 4 and 5; and the third is a 1-year, open-label safety study of patients ages 4 and 5.

For patients age 6 to 17, the starting dosage is 6.3 mg once daily in the morning; for adults, it is 12.5 mg once daily in the morning, according to the label.1 The medication will be available in 4 other dose strengths: 3.1 mg, 9.4 mg, 15.7 mg, and 18.8 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to the drug among pediatric patients include loss of appetite, insomnia, and abdominal pain. Among adult patients, adverse reactions include dry mouth, loss of appetite, and insomnia.

1. Adzenys XR-ODT [prescription packet]. Grand Prairie, TX: Neos Therapeutics, LP; 2016.

2. Neos Therapeutics announces FDA approval of Adzenys XR-ODT (amphetamine extended-release orally disintegrating tablet) for the treatment of ADHD in patients 6 years and older [news release]. Dallas, TX: Neos Therapeutics, Inc; January 27, 2016. http://investors.neostx.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=254075&p=RssLanding&cat=news&id=2132931. Accessed February 3, 2016.

An amphetamine-based, extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for patients age ≥6 diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) won FDA approval on January 28, 2016 (Table).1

Adzenys XR-ODT is the first extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for ADHD, Neos Therapeutics, Inc. the drug’s manufacturer, said in a statement.2 The newly approved agent is bioequivalent to Adderall XR (the capsule form of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts), and patients taking Adderall XR can be switched to the new drug. Equivalent dosages of the 2 drugs are outlined on the prescribing information.1

“The novel features of an extended-release orally disintegrating tablet ... make Adzenys XR-ODT attractive for use in both children (6 and older) and adults,” Alice R. Mao, MD, Medical Director, Memorial Park Psychiatry, Houston, Texas, said in the statement.2

As a condition of the approval, Neos must annually report the status of 3 post-marketing studies of children diagnosed with ADHD taking Adzenys XR-ODT, according to the approval letter.2 One is a single-dose, open-label study of children ages 4 and 5; the second is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled titration study of children ages 4 and 5; and the third is a 1-year, open-label safety study of patients ages 4 and 5.

For patients age 6 to 17, the starting dosage is 6.3 mg once daily in the morning; for adults, it is 12.5 mg once daily in the morning, according to the label.1 The medication will be available in 4 other dose strengths: 3.1 mg, 9.4 mg, 15.7 mg, and 18.8 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to the drug among pediatric patients include loss of appetite, insomnia, and abdominal pain. Among adult patients, adverse reactions include dry mouth, loss of appetite, and insomnia.

An amphetamine-based, extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for patients age ≥6 diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) won FDA approval on January 28, 2016 (Table).1

Adzenys XR-ODT is the first extended-release, orally disintegrating tablet for ADHD, Neos Therapeutics, Inc. the drug’s manufacturer, said in a statement.2 The newly approved agent is bioequivalent to Adderall XR (the capsule form of extended-release mixed amphetamine salts), and patients taking Adderall XR can be switched to the new drug. Equivalent dosages of the 2 drugs are outlined on the prescribing information.1

“The novel features of an extended-release orally disintegrating tablet ... make Adzenys XR-ODT attractive for use in both children (6 and older) and adults,” Alice R. Mao, MD, Medical Director, Memorial Park Psychiatry, Houston, Texas, said in the statement.2

As a condition of the approval, Neos must annually report the status of 3 post-marketing studies of children diagnosed with ADHD taking Adzenys XR-ODT, according to the approval letter.2 One is a single-dose, open-label study of children ages 4 and 5; the second is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled titration study of children ages 4 and 5; and the third is a 1-year, open-label safety study of patients ages 4 and 5.

For patients age 6 to 17, the starting dosage is 6.3 mg once daily in the morning; for adults, it is 12.5 mg once daily in the morning, according to the label.1 The medication will be available in 4 other dose strengths: 3.1 mg, 9.4 mg, 15.7 mg, and 18.8 mg.

The most common adverse reactions to the drug among pediatric patients include loss of appetite, insomnia, and abdominal pain. Among adult patients, adverse reactions include dry mouth, loss of appetite, and insomnia.

1. Adzenys XR-ODT [prescription packet]. Grand Prairie, TX: Neos Therapeutics, LP; 2016.

2. Neos Therapeutics announces FDA approval of Adzenys XR-ODT (amphetamine extended-release orally disintegrating tablet) for the treatment of ADHD in patients 6 years and older [news release]. Dallas, TX: Neos Therapeutics, Inc; January 27, 2016. http://investors.neostx.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=254075&p=RssLanding&cat=news&id=2132931. Accessed February 3, 2016.

1. Adzenys XR-ODT [prescription packet]. Grand Prairie, TX: Neos Therapeutics, LP; 2016.

2. Neos Therapeutics announces FDA approval of Adzenys XR-ODT (amphetamine extended-release orally disintegrating tablet) for the treatment of ADHD in patients 6 years and older [news release]. Dallas, TX: Neos Therapeutics, Inc; January 27, 2016. http://investors.neostx.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=254075&p=RssLanding&cat=news&id=2132931. Accessed February 3, 2016.

TAMIS for rectal cancer holds its own vs. TEM

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Over the past 30 years, transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) has emerged as a technique for localized rectal cancer, but the need for expensive specialized equipment put it beyond the reach of most hospitals.

Now, early results with transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) may open the door to an option that achieves the benefits of TEM while using commonly available and less expensive equipment, according to a study presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

Dr. John Costello, general surgery resident at Georgetown University, Washington, presented a poster summarizing the findings of a systematic literature review of TEM and TAMIS studies. The experience with TAMIS is more limited since Dr. Sam Atallah of Sebring, Fla., first introduced it in 2010. The review included the only head-to-head study of the technical aspects of TAMIS and TEM to date.

“Overall the results are very similar between the two approaches,” Dr. Costello said. “In many ways there are, at least anecdotally, some benefits potentially toward the TAMIS technique aside from cost: The perioperative morbidity may be a little lower and, particularly, there seemed to be fewer early problems with continence after surgery.”

The review found similar outcomes between the two approaches: low recurrence rates for small tumors (up to 3 cm) of 4% for TAMIS and 5% for TEM, although the study found that the recurrence rate for TEM increased with larger tumors. Surgery-related deaths with TAMIS ranged from 7.4% to19% and TEM from 6% to 31% across the studies reviewed.

The challenge with the systematic review was that the population of patients who had TAMIS was fewer than 500.

Dr. Costello elucidated the reasons that rectal cancer surgery has proved so challenging to surgeons over the years. The choice of operation was either limited to transabdominal or transanal excision, but the transanal approach had limitations anatomically and was found to be oncologically inferior for early stage cancer. Even with the evolution of the TEM approach, its adoption has been slow.

Either TEM or TAMIS would be a good option for patients too frail for the radical resection that low anterior resection or abdominal perineal resection demand, and would offer an option for palliation for advanced disease, Dr. Costello said. “You could locally resect patients in a way that they go home the same day or at most stay one day in the hospital,” he said.

“The challenge with TEM is that, although the oncologic outcomes are quite good with early-stage disease, the adoption has been very poor over 3 decades mainly because it requires specialized equipment with a very large upfront cost that is limited to use in the rectum,” Dr. Costello said. He estimated the initial capital investment cost for TEM equipment at up to $60,000 on average.

The TAMIS approach, on the other hand, carries a per-procedure equipment cost of about $500 over traditional laparoscopic surgery, he said. It can utilize the single-incision laparoscopic port (SILS) for the transanal approach. TAMIS sacrifices the three-dimensional view of TEM for two-dimensional, but it does provide 360-degree visualization. The surgeon must also be facile with the laparoscopic technique. “In the past that was a big challenge, but now all trainees are very familiar with laparoscopic surgery,” Dr. Costello said.

While the paucity of data on the TAMIS approach makes it difficult to make a strong case for the procedure, the path forward is clear, Dr. Costello said.

“We feel, as do a number of authors of the most papers, that the time truly is now for an actual prospective randomized trial to compare these techniques head-to-head, because colorectal surgeons now have the skill set to be facile at both,” Dr. Costello said.

The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Over the past 30 years, transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) has emerged as a technique for localized rectal cancer, but the need for expensive specialized equipment put it beyond the reach of most hospitals.

Now, early results with transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) may open the door to an option that achieves the benefits of TEM while using commonly available and less expensive equipment, according to a study presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

Dr. John Costello, general surgery resident at Georgetown University, Washington, presented a poster summarizing the findings of a systematic literature review of TEM and TAMIS studies. The experience with TAMIS is more limited since Dr. Sam Atallah of Sebring, Fla., first introduced it in 2010. The review included the only head-to-head study of the technical aspects of TAMIS and TEM to date.

“Overall the results are very similar between the two approaches,” Dr. Costello said. “In many ways there are, at least anecdotally, some benefits potentially toward the TAMIS technique aside from cost: The perioperative morbidity may be a little lower and, particularly, there seemed to be fewer early problems with continence after surgery.”

The review found similar outcomes between the two approaches: low recurrence rates for small tumors (up to 3 cm) of 4% for TAMIS and 5% for TEM, although the study found that the recurrence rate for TEM increased with larger tumors. Surgery-related deaths with TAMIS ranged from 7.4% to19% and TEM from 6% to 31% across the studies reviewed.

The challenge with the systematic review was that the population of patients who had TAMIS was fewer than 500.

Dr. Costello elucidated the reasons that rectal cancer surgery has proved so challenging to surgeons over the years. The choice of operation was either limited to transabdominal or transanal excision, but the transanal approach had limitations anatomically and was found to be oncologically inferior for early stage cancer. Even with the evolution of the TEM approach, its adoption has been slow.

Either TEM or TAMIS would be a good option for patients too frail for the radical resection that low anterior resection or abdominal perineal resection demand, and would offer an option for palliation for advanced disease, Dr. Costello said. “You could locally resect patients in a way that they go home the same day or at most stay one day in the hospital,” he said.

“The challenge with TEM is that, although the oncologic outcomes are quite good with early-stage disease, the adoption has been very poor over 3 decades mainly because it requires specialized equipment with a very large upfront cost that is limited to use in the rectum,” Dr. Costello said. He estimated the initial capital investment cost for TEM equipment at up to $60,000 on average.

The TAMIS approach, on the other hand, carries a per-procedure equipment cost of about $500 over traditional laparoscopic surgery, he said. It can utilize the single-incision laparoscopic port (SILS) for the transanal approach. TAMIS sacrifices the three-dimensional view of TEM for two-dimensional, but it does provide 360-degree visualization. The surgeon must also be facile with the laparoscopic technique. “In the past that was a big challenge, but now all trainees are very familiar with laparoscopic surgery,” Dr. Costello said.

While the paucity of data on the TAMIS approach makes it difficult to make a strong case for the procedure, the path forward is clear, Dr. Costello said.

“We feel, as do a number of authors of the most papers, that the time truly is now for an actual prospective randomized trial to compare these techniques head-to-head, because colorectal surgeons now have the skill set to be facile at both,” Dr. Costello said.

The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Over the past 30 years, transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) has emerged as a technique for localized rectal cancer, but the need for expensive specialized equipment put it beyond the reach of most hospitals.

Now, early results with transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) may open the door to an option that achieves the benefits of TEM while using commonly available and less expensive equipment, according to a study presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

Dr. John Costello, general surgery resident at Georgetown University, Washington, presented a poster summarizing the findings of a systematic literature review of TEM and TAMIS studies. The experience with TAMIS is more limited since Dr. Sam Atallah of Sebring, Fla., first introduced it in 2010. The review included the only head-to-head study of the technical aspects of TAMIS and TEM to date.

“Overall the results are very similar between the two approaches,” Dr. Costello said. “In many ways there are, at least anecdotally, some benefits potentially toward the TAMIS technique aside from cost: The perioperative morbidity may be a little lower and, particularly, there seemed to be fewer early problems with continence after surgery.”

The review found similar outcomes between the two approaches: low recurrence rates for small tumors (up to 3 cm) of 4% for TAMIS and 5% for TEM, although the study found that the recurrence rate for TEM increased with larger tumors. Surgery-related deaths with TAMIS ranged from 7.4% to19% and TEM from 6% to 31% across the studies reviewed.

The challenge with the systematic review was that the population of patients who had TAMIS was fewer than 500.

Dr. Costello elucidated the reasons that rectal cancer surgery has proved so challenging to surgeons over the years. The choice of operation was either limited to transabdominal or transanal excision, but the transanal approach had limitations anatomically and was found to be oncologically inferior for early stage cancer. Even with the evolution of the TEM approach, its adoption has been slow.

Either TEM or TAMIS would be a good option for patients too frail for the radical resection that low anterior resection or abdominal perineal resection demand, and would offer an option for palliation for advanced disease, Dr. Costello said. “You could locally resect patients in a way that they go home the same day or at most stay one day in the hospital,” he said.

“The challenge with TEM is that, although the oncologic outcomes are quite good with early-stage disease, the adoption has been very poor over 3 decades mainly because it requires specialized equipment with a very large upfront cost that is limited to use in the rectum,” Dr. Costello said. He estimated the initial capital investment cost for TEM equipment at up to $60,000 on average.

The TAMIS approach, on the other hand, carries a per-procedure equipment cost of about $500 over traditional laparoscopic surgery, he said. It can utilize the single-incision laparoscopic port (SILS) for the transanal approach. TAMIS sacrifices the three-dimensional view of TEM for two-dimensional, but it does provide 360-degree visualization. The surgeon must also be facile with the laparoscopic technique. “In the past that was a big challenge, but now all trainees are very familiar with laparoscopic surgery,” Dr. Costello said.

While the paucity of data on the TAMIS approach makes it difficult to make a strong case for the procedure, the path forward is clear, Dr. Costello said.

“We feel, as do a number of authors of the most papers, that the time truly is now for an actual prospective randomized trial to compare these techniques head-to-head, because colorectal surgeons now have the skill set to be facile at both,” Dr. Costello said.

The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose.

AT THE ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: TAMIS for removal of rectal tumors achieved equal outcomes to TEM with measurable cost savings.

Major finding: The review found similar outcomes between the two procedures and low recurrence rates for small tumors (up to 3 cm) of 4% for TAMIS and 5% for TEM.

Data source: Systematic literature review of fewer than 500 cases of TAMIS, compared with results of TEM literature.

Disclosures: The study authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Peter Chin, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

VIDEO: Bench research provides insight into progressive MS

New Orleans – A “Lessons from the Bench” session at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis addressed the ongoing debate regarding the relative importance of neurodegeneration vs. inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis.

In an interview, session chair Dr. Benjamin Segal discussed the research presented – on topics ranging from immunological biomarkers that could also prove to be therapeutic targets, to immune- and central nervous system–related susceptibility alleles identified in genome wide association studies – and how the findings could lead to new and improved treatments.

“These types of studies give us insights into the immune pathways that are dysregulated in the different diseases and how they may be similar or different from one another. Ultimately all of these scientific studies hopefully will translate into treatments in the future,” said Dr. Segal of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

New Orleans – A “Lessons from the Bench” session at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis addressed the ongoing debate regarding the relative importance of neurodegeneration vs. inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis.

In an interview, session chair Dr. Benjamin Segal discussed the research presented – on topics ranging from immunological biomarkers that could also prove to be therapeutic targets, to immune- and central nervous system–related susceptibility alleles identified in genome wide association studies – and how the findings could lead to new and improved treatments.

“These types of studies give us insights into the immune pathways that are dysregulated in the different diseases and how they may be similar or different from one another. Ultimately all of these scientific studies hopefully will translate into treatments in the future,” said Dr. Segal of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

New Orleans – A “Lessons from the Bench” session at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis addressed the ongoing debate regarding the relative importance of neurodegeneration vs. inflammation in progressive multiple sclerosis.

In an interview, session chair Dr. Benjamin Segal discussed the research presented – on topics ranging from immunological biomarkers that could also prove to be therapeutic targets, to immune- and central nervous system–related susceptibility alleles identified in genome wide association studies – and how the findings could lead to new and improved treatments.

“These types of studies give us insights into the immune pathways that are dysregulated in the different diseases and how they may be similar or different from one another. Ultimately all of these scientific studies hopefully will translate into treatments in the future,” said Dr. Segal of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ACTRIMS FORUM 2016

Does Fatigue Worsen Spasticity in Patients With MS?

NEW ORLEANS—Contrary to researchers’ hypothesis, fatigue did not result in worsening of spasticity in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), resulting instead in a nonsignificant decrease. “Clinically, this suggests that the worsening of gait seen over time in persons with MS may be due to reasons other than spasticity,” reported Herbert Karpatkin, PT, DSc, NCS, MSCS, an Assistant Professor at Hunter College in New York, NY, and colleagues at the ACTRIMS 2016 Forum.

Herbert Karpatkin, PT, DSc, NCS, MSCS