User login

Ibrutinib approved as first-line therapy for all CLL patients

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) has been approved as a first-line treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), irrespective of their treatment history, according to a statement issued by the manufacturer, AbbVie.

The approval is based on data from the randomized, multicenter, open-label phase III RESONATE-2 trial, which evaluated the use of ibrutinib versus chlorambucil in 269 treatment-naive patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) aged 65 years or older. The RESONATE-2 data were presented at the 2015 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The progression-free survival data seen in these previously untreated CLL patients are strong and encouraging,” Dr. Jan Burger of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and the lead investigator of RESONATE-2, said in the AbbVie statement. “This is especially important for first-line CLL patients, when considering the safety profile. This treatment represents another option for these patients.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network also recently published an update to its clinical practice guidelines for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, granting Imbruvica a category 1 recommendation for certain CLL patients, including as a first-line treatment option for frail CLL patients with significant comorbidities, as well as for CLL patients with or without del 17p or the genetic mutation TP53 who are 70 years or older, or younger patients with significant comorbidities, the AbbVie statement noted.

Imbruvica has been jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company, and by Janssen Biotech.

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) has been approved as a first-line treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), irrespective of their treatment history, according to a statement issued by the manufacturer, AbbVie.

The approval is based on data from the randomized, multicenter, open-label phase III RESONATE-2 trial, which evaluated the use of ibrutinib versus chlorambucil in 269 treatment-naive patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) aged 65 years or older. The RESONATE-2 data were presented at the 2015 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The progression-free survival data seen in these previously untreated CLL patients are strong and encouraging,” Dr. Jan Burger of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and the lead investigator of RESONATE-2, said in the AbbVie statement. “This is especially important for first-line CLL patients, when considering the safety profile. This treatment represents another option for these patients.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network also recently published an update to its clinical practice guidelines for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, granting Imbruvica a category 1 recommendation for certain CLL patients, including as a first-line treatment option for frail CLL patients with significant comorbidities, as well as for CLL patients with or without del 17p or the genetic mutation TP53 who are 70 years or older, or younger patients with significant comorbidities, the AbbVie statement noted.

Imbruvica has been jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company, and by Janssen Biotech.

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica) has been approved as a first-line treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), irrespective of their treatment history, according to a statement issued by the manufacturer, AbbVie.

The approval is based on data from the randomized, multicenter, open-label phase III RESONATE-2 trial, which evaluated the use of ibrutinib versus chlorambucil in 269 treatment-naive patients with CLL or small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) aged 65 years or older. The RESONATE-2 data were presented at the 2015 annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

“The progression-free survival data seen in these previously untreated CLL patients are strong and encouraging,” Dr. Jan Burger of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, and the lead investigator of RESONATE-2, said in the AbbVie statement. “This is especially important for first-line CLL patients, when considering the safety profile. This treatment represents another option for these patients.”

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network also recently published an update to its clinical practice guidelines for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, granting Imbruvica a category 1 recommendation for certain CLL patients, including as a first-line treatment option for frail CLL patients with significant comorbidities, as well as for CLL patients with or without del 17p or the genetic mutation TP53 who are 70 years or older, or younger patients with significant comorbidities, the AbbVie statement noted.

Imbruvica has been jointly developed and commercialized by Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company, and by Janssen Biotech.

Primary care acne treatment reduces dermatology referrals

If primary care physicians initiated therapy in patients with mild to moderate acne, they could significantly decrease referrals to dermatologists, reduce patient waiting times, and cut health care costs, based on a study published online March 6 in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers used retrospective data to model two treatment algorithms for initiating acne therapy based on evaluations of 253 dermatology referrals by primary care physicians at a single center. Half of the acne patients had not received any topical or systemic treatment prior to their referral to a dermatologist.

Two treatment algorithms were modeled for initiating acne therapy: In the first, the primary care physicians initiated topical acne treatments; in the second, they initiated topical treatments and systemic antibiotics.

If primary care physicians initiated topical acne therapy, the first algorithm predicted a 48% reduction in initial referrals to dermatologists, a 40% overall reduction in referrals, a mean 28.6-day reduction in delay to treatment, and an associated cost savings of $20.28 per patient.

Following the second algorithm entirely eliminated referrals for 72% of patients, reduced initial referrals by 86.7%, and reduced the mean delay to treatment by 27.9 days; the cost savings was $35.68 per patient, wrote Dr. Kristina J. Liu of the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program and coauthors (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 March 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0183).

“Our findings are extracted from and applicable to patients who already have access to primary care clinicians. While patients can be efficiently treated by presenting directly to a dermatologist, in many health plans, a referral from primary care is a requisite step that precludes this possibility. Furthermore, 235 patients (93%) in our cohort were being managed by their primary care clinicians for other health conditions in addition to acne. Given these other health concerns, the patients in our study would likely access their primary care clinicians regardless of the problem of acne. Thus, the judicious use of primary care resources to manage acne as part of the holistic care of the patient can prove to be a time- and cost-saving strategy,” the authors wrote.

In addition, 32% of the referrals in the study were for acne plus another dermatologic issue, and such patients likely require dermatologic evaluation regardless of primary care clinician-driven acne management, the authors added.

One author declared employment with Walgreens Boots Alliance. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

If primary care physicians initiated therapy in patients with mild to moderate acne, they could significantly decrease referrals to dermatologists, reduce patient waiting times, and cut health care costs, based on a study published online March 6 in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers used retrospective data to model two treatment algorithms for initiating acne therapy based on evaluations of 253 dermatology referrals by primary care physicians at a single center. Half of the acne patients had not received any topical or systemic treatment prior to their referral to a dermatologist.

Two treatment algorithms were modeled for initiating acne therapy: In the first, the primary care physicians initiated topical acne treatments; in the second, they initiated topical treatments and systemic antibiotics.

If primary care physicians initiated topical acne therapy, the first algorithm predicted a 48% reduction in initial referrals to dermatologists, a 40% overall reduction in referrals, a mean 28.6-day reduction in delay to treatment, and an associated cost savings of $20.28 per patient.

Following the second algorithm entirely eliminated referrals for 72% of patients, reduced initial referrals by 86.7%, and reduced the mean delay to treatment by 27.9 days; the cost savings was $35.68 per patient, wrote Dr. Kristina J. Liu of the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program and coauthors (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 March 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0183).

“Our findings are extracted from and applicable to patients who already have access to primary care clinicians. While patients can be efficiently treated by presenting directly to a dermatologist, in many health plans, a referral from primary care is a requisite step that precludes this possibility. Furthermore, 235 patients (93%) in our cohort were being managed by their primary care clinicians for other health conditions in addition to acne. Given these other health concerns, the patients in our study would likely access their primary care clinicians regardless of the problem of acne. Thus, the judicious use of primary care resources to manage acne as part of the holistic care of the patient can prove to be a time- and cost-saving strategy,” the authors wrote.

In addition, 32% of the referrals in the study were for acne plus another dermatologic issue, and such patients likely require dermatologic evaluation regardless of primary care clinician-driven acne management, the authors added.

One author declared employment with Walgreens Boots Alliance. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

If primary care physicians initiated therapy in patients with mild to moderate acne, they could significantly decrease referrals to dermatologists, reduce patient waiting times, and cut health care costs, based on a study published online March 6 in JAMA Dermatology.

The researchers used retrospective data to model two treatment algorithms for initiating acne therapy based on evaluations of 253 dermatology referrals by primary care physicians at a single center. Half of the acne patients had not received any topical or systemic treatment prior to their referral to a dermatologist.

Two treatment algorithms were modeled for initiating acne therapy: In the first, the primary care physicians initiated topical acne treatments; in the second, they initiated topical treatments and systemic antibiotics.

If primary care physicians initiated topical acne therapy, the first algorithm predicted a 48% reduction in initial referrals to dermatologists, a 40% overall reduction in referrals, a mean 28.6-day reduction in delay to treatment, and an associated cost savings of $20.28 per patient.

Following the second algorithm entirely eliminated referrals for 72% of patients, reduced initial referrals by 86.7%, and reduced the mean delay to treatment by 27.9 days; the cost savings was $35.68 per patient, wrote Dr. Kristina J. Liu of the Harvard Combined Dermatology Residency Program and coauthors (JAMA Dermatol. 2016 March 6. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0183).

“Our findings are extracted from and applicable to patients who already have access to primary care clinicians. While patients can be efficiently treated by presenting directly to a dermatologist, in many health plans, a referral from primary care is a requisite step that precludes this possibility. Furthermore, 235 patients (93%) in our cohort were being managed by their primary care clinicians for other health conditions in addition to acne. Given these other health concerns, the patients in our study would likely access their primary care clinicians regardless of the problem of acne. Thus, the judicious use of primary care resources to manage acne as part of the holistic care of the patient can prove to be a time- and cost-saving strategy,” the authors wrote.

In addition, 32% of the referrals in the study were for acne plus another dermatologic issue, and such patients likely require dermatologic evaluation regardless of primary care clinician-driven acne management, the authors added.

One author declared employment with Walgreens Boots Alliance. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: If primary care physicians initiate treatment of mild to moderate acne, they could significantly reduce referrals to dermatologists and patient waiting times for treatment.

Major finding: Primary care treatment can reduce referrals to dermatologists for acne by up to 72%.

Data source: A retrospective study and modeling of 253 referrals.

Disclosures: One author declared employment with Walgreens Boots Alliance. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

VIDEO: Study links hair loss in black women with genetics

WASHINGTON – Almost 41% of black women surveyed described hair loss that was consistent with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), but only about 9% said they had been diagnosed with the condition, Dr. Yolanda Lenzy reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Lenzy of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, discussed the results of a hair survey she conducted with the Black Women’s Health Study at Boston University’s Slone Epidemiology Center. Nearly 6,000 women have completed the survey to date.

“For many years, it was thought to be due to hair styling practices,” but there are new data showing that genetics can be an important cause, she said, referring to research from South Africa indicating that CCCA can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.

Dr. Lenzy, who practices dermatology in Chicopee, Mass., used a central hair loss photographic scale in the study, which also can be helpful in the office to monitor hair loss and “to quantify how much hair loss a person has … in terms of: Are they getting worse? Do they go from stage 3 to stage 5 or stage 1 to stage 3?”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Almost 41% of black women surveyed described hair loss that was consistent with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), but only about 9% said they had been diagnosed with the condition, Dr. Yolanda Lenzy reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Lenzy of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, discussed the results of a hair survey she conducted with the Black Women’s Health Study at Boston University’s Slone Epidemiology Center. Nearly 6,000 women have completed the survey to date.

“For many years, it was thought to be due to hair styling practices,” but there are new data showing that genetics can be an important cause, she said, referring to research from South Africa indicating that CCCA can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.

Dr. Lenzy, who practices dermatology in Chicopee, Mass., used a central hair loss photographic scale in the study, which also can be helpful in the office to monitor hair loss and “to quantify how much hair loss a person has … in terms of: Are they getting worse? Do they go from stage 3 to stage 5 or stage 1 to stage 3?”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

WASHINGTON – Almost 41% of black women surveyed described hair loss that was consistent with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), but only about 9% said they had been diagnosed with the condition, Dr. Yolanda Lenzy reported at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

In a video interview at the meeting, Dr. Lenzy of the University of Connecticut, Farmington, discussed the results of a hair survey she conducted with the Black Women’s Health Study at Boston University’s Slone Epidemiology Center. Nearly 6,000 women have completed the survey to date.

“For many years, it was thought to be due to hair styling practices,” but there are new data showing that genetics can be an important cause, she said, referring to research from South Africa indicating that CCCA can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.

Dr. Lenzy, who practices dermatology in Chicopee, Mass., used a central hair loss photographic scale in the study, which also can be helpful in the office to monitor hair loss and “to quantify how much hair loss a person has … in terms of: Are they getting worse? Do they go from stage 3 to stage 5 or stage 1 to stage 3?”

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT AAD 16

Highlights From the SCNS Meeting

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.

Click here to download the digital edition.

Recognition and Management of Children with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

From the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY.

Abstract

- Objective: To review diagnostic challenges and management strategies in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

- Methods: Review of the literaure.

- Results: NAFLD is common in the United States and should be suspected in overweight or obese children with an elevated serum alanine aminotransferase level. The differential diagnosis for these patients is broad, however, and liver biopsy—the gold standard test—should be undertaken selectively after an appropriate workup. Patients should be counseled on lifestyle modifications, whereas vitamin E therapy can be initiated for those with biopsy-proven disease.

- Conclusion: Providers should have a high degree of suspicion for NAFLD, approaching the workup and diagnosis in an incremental, step-wise fashion. Further research is needed to standardize the diagnostic approach, identify reliable, noninvasive diagnostic measures, and develop novel treatment modalities.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease in the Western world, affecting approximately 10% of children and a third of all adults in the United States [1–3]. It is a significant public health challenge and is estimated to soon be the number one indication for liver transplantation in adults.

NAFLD is a generic term encompassing 2 distinct conditions defined by their histopathology: simple steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Simple steatosis is characterized by predominantly macrovesicular—meaning large droplet—cytoplasmic lipid inclusions found in ≥ 5% of hepatocytes. NASH is defined as hepatic steatosis plus the additional features of inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and/or fibrosis. There are some adult data [4-6] and 1 retrospective pediatric study [7] demonstrating that over time, NAFLD may progress. That is, steatosis may progress to NASH and some patients with fibrosis will ultimately develop cirrhosis. If intervention is provided early in the histologic spectrum, NAFLD can be reversed [4,8] and late complications—such as cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver transplantation—may be prevented.

It is important to highlight that the above definitions are based on histology and that a liver biopsy cannot be reasonably obtained in such a large percentage of the U.S. population. This case-based review will therefore focus primarily on the current diagnostic challenges facing health care providers as well as management strategies in children with presumed NAFLD.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

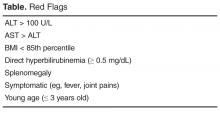

As you finish your charts at the end of a busy clinic day, you identify 3 patients who may have NAFLD:

History

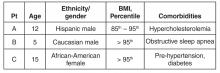

All 3 patients presented to your office for a routine annual physical before the start of the school year and are asymptomatic. None of the patients has a family history of liver disease and their previously diagnosed comorbidities are listed in the table above. No patient is taking medications other than patient C, who is on metformin.

All 3 children have a smooth, velvety rash on their necks consistent with acanthosis nigricans with an otherwise normal physical exam. The liver and spleen are difficult to palpate but are seemingly normal.

What is the typical presentation for a child with NAFLD?

Most children with NAFLD are asymptomatic, though some may present with vague right upper quadrant abdominal pain. It is unclear, however, if the pain is caused by NAFLD or is rather an unrelated symptom that brings the child to the attention of a physician. In addition, hepatomegaly can be found in over 30% to 40% of patients [9]. For children without abdominal pain or hepatomegaly, most are recognized by an elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or findings of increased liver echogenicity on ultrasonography.

Serum Alanine Aminotransferase

Serum aminotransferases are one of the more common screening tests for NAFLD. However, ALT is highly insensitive at commonly used thresholds and is also nonspecific. As documented in the SAFETY study, the upper limit of normal for ALT in healthy children should be set around 25 U/L in boys and 22 U/L in girls [10]. Yet even at these thresholds, the sensitivity of ALT to diagnose NAFLD is 80% in boys and 92% in girls, whereas specificity is 79% and 85%, respectively [10]. These findings are largely consistent with adult studies [11–14]. Furthermore, ALT does not correlate well with disease severity and children may still have NASH or significant fibrosis with normal values. In a well-characterized cohort of 91 children with biopsy-proven NAFLD, for example, early fibrosis was identified in 12% of children with a normal ALT (≤ 22 U/L for girls and ≤ 25 U/L in boys) [15]. Advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis was seen in 9% of children with an ALT up to 2 times this upper limit [15]. Thus, reliance on the serum ALT may significantly underestimate the prevalence and severity of liver injury.

Ultrasonography

Children with NAFLD typically have findings of increased hepatic echogenicity on abdominal ultrasonography. However, there are multiple limitations to sonography. First, ultrasound is insensitive for identifying mild steatosis if less than 30% of hepatocytes are affected [16,17]. Second, increased hepatic echogenicity is nonspecific and may be caused by inflammation, fibrosis, or intrahepatic accumulation of iron, copper, or glycogen. Third, there can be considerable inter- and intra-operator variability. And lastly, there is some evidence that ultrasounds do not add benefit to diagnosing children with NAFLD [18].

Which patients are at risk for developing hepatic steatosis and NASH?

Weight, Age, and Gender

There is a strong, direct correlation between body mass index (BMI) and NAFLD. The Study of Child and Adolescent Liver Epidemiology (SCALE)—a sentinel pediatric autopsy study of 742 children—found that 5% of normal weight children, 16% of overweight children, and 38% of obese children had NAFLD. The SCALE study also demonstrated an increasing prevalence with age, such that NAFLD was present in 17.3% of 15- to 19-year-olds but only in 0.2% of 2- to 4-year-olds [1]. With regards to gender, NAFLD is roughly twice as prevalent in males [18–20]. While the exact etiology of this difference is unclear, hormonal differences are a leading hypothesis.

Ethnicity

NAFLD is most common in Hispanics, followed by Asians, Caucasians, and African Americans. Research suggests that genetics may be largely responsible for these ethnic disparities. For example, the I148M allele of PNPLA3 (a single nucleotide polymorphism) is strongly associated with steatosis, NASH, and fibrosis [21] and is most common in Hispanics, with a 50% carrier frequency in some cohorts [22]. Conversely, African Americans are more likely to carry the S453I allele of PNPLA3, which is associated with decreased hepatic steatosis [22]. There is also considerable variability within ethnic groups. For example, Mexican-American children appear to be at the highest risk for steatosis or NASH among Hispanics, whereas Filipino-American children are believed to have higher disease prevalence than Cambodian or Vietnamese Americans [1].

Comorbidities

NAFLD is associated with obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, the metabolic syndrome [23], decreased quality of life [24,25], and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). These associations generally hold even after controlling for the other confounders listed. It is important to note that these data come largely from cross-sectional studies and direct causation has yet to be determined.

Insulin resistance in particular is strongly associated with NAFLD—so much so, in fact, that some consider it to be the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Additionally, children with features of the metabolic syndrome are more likely to have advanced histologic features of NAFLD [23]. There are also intriguing data from small pediatric studies to suggest that OSA may contribute to the development of hepatic fibrosis. In one study of 25 children with biopsy-proven NAFLD, for example, the presence of OSA and hypoxemia correlated with the degree of hepatic fibrosis [26]. In a slightly larger study of 65 children, OSA was also strongly associated with significant hepatic fibrosis (odds ratio, 5.91; 95% confidence interval, 3.23–7.42; P < 0.001). The duration of hypoxemia also correlated with histologic findings of inflammation and circulating biomarkers of apoptosis and fibrogenesis [27].

Other Laboratory Tests

Several studies have documented an association between elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and hepatic fibrosis [28,29], though others have been conflicting [30,31]. Pediatric studies have also demonstrated an inverse correlation between NASH and total bilirubin [32], serum potassium [33], and serum ceruloplasmin [34]. In addition, there are a number of serum biomarkers or biomarker panels commercially available for use in adults. Because similar efficacy data are unavailable in children, however, serum biomarkers should be primarily used for research purposes only.

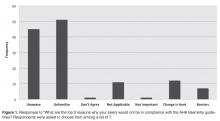

Who should be screened for NAFLD? And how?

Published professional society recommendations differ significantly with regards to screening. In 2007, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggested screening obese children over 10 years of age or overweight children with additional risk factors with biannual liver tests [35]. There were no management recommendations made for elevated aminotransferase levels other than for subspecialty referral. In 2012, the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) recommended obtaining an ultrasound and liver tests in every obese child [36]. One month later, however, the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, and the American College of Gastroenterology published joint guidelines without screening recommendations “due to a paucity of evidence” [37].

Because these statements conflict and are based heavily on expert opinion, one should consider the risks, benefits, and costs to screening large numbers of patients. Until additional research clarifies this controversy, we suggest that providers individualize their screening practices to their population and the risks of each individual patient. For example, we would consider screening children who are obese; Hispanic or Asian; have multiple features of the metabolic syndrome; and/or those who have a family history of NAFLD. Further, we recommend screening children for NAFLD with serum liver enzymes only and not with ultrasonography.

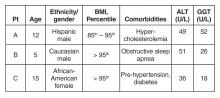

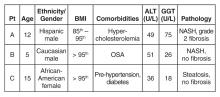

Case Continued: Laboratory Results

ALT and GGT tests are ordered and the results are as follows:

What is the differential for children with suspected NAFLD?

Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH)

AIH is a progressive necro-inflammatory disorder of the liver characterized by elevated aminotransferases, positive autoantibodies, and distinctive histologic features. AIH is believed to occur in genetically predisposed patients in response to an environmental trigger. There is a female predominance and it can present in any age or ethnic group.

AIH is divided in 2 subtypes. Type 1 disease is characterized by a positive antinuclear (ANA) antibody and anti-smooth muscle antibody. More commonly, it presents in adolescence with an indolent course—many patients are asymptomatic until they develop features of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Conversely, type 2 AIH is characterized by a positive liver kidney microsomal (LKM) antibody and tends to present acutely in young children. It is important to note that antibody titers can be falsely positive in a significant percentage of patients and, in such cases, are often mildly elevated [38]. We strongly suggest children with positive autoantibody titers be evaluated by a specialist.

Treatment should be started promptly to avoid progression to cirrhosis and should also done so in consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist or hepatologist. The prognosis of AIH with immunosuppression is favorable, with long-term remission rates of approximately 80%. Transplantation is typically required in the remaining 10% to 20% [39].

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune, inflammatory enteropathy caused by exposure to gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. Up to a third of all children presenting with celiac will have an elevated serum ALT [40]. Additional symptoms/features are both variable and nonspecific: abdominal pain, poor growth, diarrhea, or constipation, among others. Celiac is diagnosed by duodenal biopsy or a sufficiently elevated tissue transglutaminase antibody level [41]. Treatment with a strict gluten-free diet will resolve the enteropathy and normalize the serum aminotransferases.

Wilson’s Disease

Wilson’s disease is a metabolic disorder leading to copper deposition in the liver, brain, cornea, and kidneys. It is caused by an ATP7B gene mutation and inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. Patients may present with asymptomatic liver disease, chronic hepatitis, acute liver failure, or with symptoms of portal hypertension. Neuropsychiatric symptoms may also be prominent. Screening tests include a serum ceruloplasmin and 24-hour urinary copper quantification. Because diagnosing Wilson’s disease can be challenging, however, further testing should occur in consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist or hepatologist.

Viral Hepatitis

Chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B and C are still common etiologies of liver disease in the United States. However, universal vaccination and blood donor screening have reduced the risk of transmission; new antiviral agents will likely further decrease the prevalence and transmission risk over time. Acute viral hepatitis—cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis A, or hepatitis E—should also be considered in children who present with appropriate symptoms and an elevated ALT.

Drug-Induced

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) can present with elevated serum aminotransferases (hepatocellular pattern), an elevated bilirubin (cholestatic pattern), or a mixed picture. Idiosyncratic DILI in children is commonly caused by antimicrobial or central nervous system agents and usually presents with a hepatocellular injury pattern. Substance abuse, including alcohol, is common and should also be investigated as the source of underlying liver disease.

Muscle Disease

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and ALT are present in hepatocytes, myocytes, and red blood cells, among other tissues. Thus, children with congenital myopathies or myositis can have elevated aminotransferases, typically with the AST higher than the ALT. In these patients, checking a creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level may lead to the correct diagnosis and limit unnecessary testing.

Other Metabolic Disorders

Myriad metabolic disorders present with liver disease and/or elevated serum aminotransferase levels. Individually, these conditions are rare but, collectively, are relatively common. Two of the more occult conditions—lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) and alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1A) deficiency—are discussed in further detail below.

LAL-D is an autosomal recessive disease resulting in the accumulation of cholesterol esters and triglycerides in lysosomes. Patients typically present with hepatomegaly and mildly elevated aminotransferases, an elevated LDL, low HDL cholesterol, and increased hepatic echogenicity on ultrasound. If a biopsy is obtained, microvesicular steatosis is predominant as opposed to macrovesicular steatosis found in NAFLD. The diagnosis of LAL-D can be made on a commercially available dry blood spot enzymatic assay or genetic testing and treatment has recently been FDA approved.

A1A deficiency is an autosomal recessive disease diagnosable by an alpha-1-antitrypsin phenotype. The clinical presentation is characterized by neonatal cholestasis in the infantile form and by hepatitis, cirrhosis and portal hypertension in older children. Classic symptoms of emphysema and chronic lung disease present in adulthood.

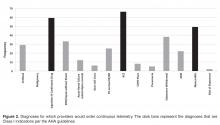

What further testing should be performed in children with suspected NAFLD?

For obese children with an elevated ALT or evidence of increased hepatic echogenicity, ESPGHAN recommends targeting the workup according to the child’s age [36]. According to their consensus statement, they recommend an upfront, thorough laboratory evaluation in children less than 10 years of age and consideration of a liver biopsy upon completion. For children over 10 years of age at low risk for NASH or fibrosis, additional laboratory evaluation is suggested 3 to 6 months after failed lifestyle interventions. In general, the recommended workup includes testing for conditions discussed in the section above such as viral hepatitis, AIH, Wilson’s disease, and others. If negative, ESPGHAN states that a liver biopsy should be “considered.”

The question of whether or not to obtain a liver biopsy is controversial, though there are several clear advantages to doing so. First, biopsy is the gold standard test for diagnosing NAFLD and there are no highly accurate, noninvasive tests currently approved for use in children. Second, biopsy is a more definitive means of ruling out competing diagnoses such as AIH. Third, biopsy may provide prognostic data. In a retrospective adult study of 136 patients, for example, those who presented with simple steatosis had a roughly 3% chance of progressing to cirrhosis within 10 years. If a patient within this cohort presented with NASH, however, the progression risk was approximately 30% within 5 years [42,43]. Fourth, due to potential side effects of medications, position papers recommend obtaining a liver biopsy prior to the initiation of pharmacotherapy [37]. Lastly, the risk for serious morbidity from a liver biopsy is low [44,45]. Alternatively, one must acknowledge the risks of liver biopsy: morbidity, sampling bias, invasiveness, cost, and sedation risks in children.

Case Continued: Biopsy Results

You refer your patients to a gastroenterologist. Tests for viral hepatitis, A1A deficiency, celiac disease, muscle disorders, Wilson’s disease, and AIH are negative. Ultimately, a liver biopsy is performed on all 3 children without complications. The results are presented below.

What is the treatment of NAFLD?

Lifestyle Modification

Lifestyle modifications are the mainstay of treatment for NAFLD. In adult studies, weight loss of more than 5% reduces hepatic steatosis whereas weight loss of more than 9% improves or eliminates NASH [47]. We recommend that children engage in age-appropriate, enjoyable, moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity for 60 minutes a day [48]. In addition, there should be a focus on reducing sedentary behavior by limiting screen time and a concerted effort to engage the family in lifestyle modifications.

Dietary interventions to treat NAFLD are less concrete but there is a growing body of literature to suggest that dietary fructose is particularly harmful. In adults, for example, fructose consumption is associated with the development of NAFLD [49] and hepatic fibrosis [50]. Recent data in adolescents has similarly documented an association between NAFLD incidence and energy-adjusted fructose intake [51]. It is worth highlighting that these clinical findings are also biologically plausible, as fructose is primarily metabolized within hepatocytes and has recently been shown to increase de novo lipogenesis [52,53]. In general, we suggest a well-balanced diet of unprocessed foods—that is, with limited added sugars—sufficient to induce gradual weight loss in older children or body weight maintenance in younger children.

Medications

Vitamin E is the only medication with proven efficacy in children, as demonstrated in the TONIC trial [20]. TONIC was a double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study with 3 treatment arms: 800 IU of vitamin E daily, 1000 mg of metformin daily, or placebo. Metformin did not reduce the serum ALT or significantly improve liver histology and should therefore not be used for these indications. However, patients treated with vitamin E had a statistically significant improvement in the NAFLD activity score (a histologic grading system comprising steatosis, inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning) and resolution of NASH when compared to placebo. For these reasons—as well as a paucity of other viable treatment options—vitamin E is routinely prescribed for children with biopsy-proven NASH. However, the long- term risks of high-dose vitamin E therapy in children are largely unknown.

Polyunsaturated fats such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [54] and probiotics such as VSL #3 [55] have showed efficacy reducing hepatic steatosis in small, randomized clinical trials. Both medications need to be further validated before they can be recommended for use in children. Conversely, ursodeoxycholic acid has not been found to be efficacious in children with NAFLD [56], whereas phase IIb data on cysteamine is expected soon. There are currently insufficient data to recommend bariatric surgery as treatment for NAFLD in adolescence.

Case Continued: Follow-up

After their biopsies, both patients with NASH (patients A and B) are started on vitamin E therapy. All 3 patients continue to report for follow-up visits without short-term complications, though they have still been unable to significantly reduce their body mass index and have a persistently elevated serum ALT.

Summary

NAFLD is a common condition in the United States with serious personal and public health ramifications. This case-based review highlights the diagnostic and management challenges in children with NAFLD and the unique role primary care providers play in caring for these patients.

Corresponding author: Bryan Rudolph, MD, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, 3415 Bainbridge Ave., Bronx, NY 10467, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Schwimmer JB, Deutsch R, Kahen T, et al. Prevalence of fatty liver in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2006;118:1388–93.

2. Welsh JA, Karpen S, Vos MB.Increasing prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among United States adolescents, 1988-1994 to 2007-2010. J Pediatr 2013;162:496–500.

3. Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:274–85.

4. McPherson S, Hardy T, Henderson E, et al. Evidence of NAFLD progression from steatosis to fibrosing-steatohepatitis using paired biopsies: implications for prognosis and clinical management. J Hepatol 2015;62:1148–55.

5. Singh S, Allen AM, Wang Z, et al. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:643–54.

6. Pais R, Charlotte F, Fedchuk L, et al. A systematic review of follow-up biopsies reveals disease progression in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver. J Hepatol 2013;59:550–6.

7. Feldstein AE, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Treeprasertsuk S, et al. The natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in children: a follow-up study for up to 20 years. Gut 2009;58:1538–44.

8. Mummadi RR, Kasturi KS, Chennareddygari S, et al. Effect of bariatric surgery on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;6:1396–402.

9. Rashid M, Roberts EA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;30:48–53.

10. Schwimmer JB, Dunn W, Norman GJ, et al. SAFETY study: alanine aminotransferase cutoff values are set too high for reliable detection of pediatric chronic liver disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:1357–64.

11. Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A, et al. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:1–10.

12. Lee JK, Shim JH, Lee HC, et al. Estimation of the healthy upper limits for serum alanine aminotransferase in Asian populations with normal liver histology. Hepatology 2010;51:1577–83.

13. Kang HS, Um SH, Seo YS, et al. Healthy range for serum ALT and the clinical significance of "unhealthy" normal ALT levels in the Korean population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26:292–9.

14. Zheng MH, Shi KQ, Fan YC, et al. Upper limits of normal for serum alanine aminotransferase levels in Chinese Han population. PLoS One 2012;7:e43736.

15. Molleston JP, Schwimmer JB, Yates KP, et al. Histological abnormalities in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and normal or mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase levels. J Pediatr 2014;164:707–13.

16. Dasarathy S, Dasarathy J, Khiyami A, et al. Validity of real time ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol 2009;51:1061–7.

17. Nobili V, M. Pinzani M. Paediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 2010;59:561–4.

18. Rudolph B, Rivas Y, Kulak S, et al. Yield of diagnostic tests in obese children with an elevated alanine aminotransferase. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:e557–63.

19. Nobili V, Manco M, Ciampalini P, et al. Metformin use in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: an open-label, 24-month, observational pilot study. Clin Ther 2008;30:1168–76.

20. Lavine JE, Schwimmer JB, Van Natta ML, et al. Effect of vitamin E or metformin for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: the TONIC randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2011;305:1659–68.

21. Krawczyk MP, Portincasa P, Lammert F. PNPLA3-associated steatohepatitis: toward a gene-based classification of fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 2013;33:369–79.

22. Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 2008;40:1461–5.

23. Patton HM, Yates K, Unalp-Arida A, et al. Association between metabolic syndrome and liver histology among children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2093–102.

24. Kistler KD, Molleston J, Unalp A, et al., Symptoms and quality of life in obese children and adolescents with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;31:396–406.

25. Kerkar N, D'Urso C, Van Nostrand K, et al. Psychosocial outcomes for children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease over time and compared with obese controls. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;56:77–82.

26. Sundaram SS, Sokol RJ, Capocelli KE, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and hypoxemia are associated with advanced liver histology in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr 2014;164:699–706.

27. Nobili V, Cutrera R, Liccardo D, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome affects liver histology and inflammatory cell activation in pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, regardless of obesity/insulin resistance. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:66–76.

28. Patton HM, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, et al., Clinical correlates of histopathology in pediatric nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1961–71.

29. Schwimmer JB, Behling C, Newbury R, et al. Histopathology of pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005;42:641–9.

30. Nobili V, Parkes J, Bottazzo G, et al. Performance of ELF serum markers in predicting fibrosis stage in pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2009;136:160–7.

31. Yang HR, Kim HR, Kim MJ, et al. Noninvasive parameters and hepatic fibrosis scores in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:1525–30.

32. Puri K, Nobili V, Melville K, et al. Serum bilirubin level is inversely associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;57:114–8.

33. Tabbaa A, Shaker M, Lopez R, et al. Low serum potassium levels associated with disease severity in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2015;18:168–74.

34. Nobili V, Siotto M, Bedogni G, et al. Levels of serum ceruloplasmin associate with pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;56:370–5.

35. Barlow SE; Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics 2007;120 Suppl 4:S164–92.

36. Vajro P, Lenta S, Socha P, et al. Diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in children and adolescents: position paper of the ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:700–13.

37. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and American College of Gastroenterology. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1592–609.

38. Vuppalanchi R, Gould RJ, Wilson LA, et al. Clinical significance of serum autoantibodies in patients with NAFLD: results from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatol Int 2012;6:379–85.

39. Floreani A, Liberal R, Vergani D, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis: contrasts and comparisons in children and adults - a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun 2013;46:7–16.

40. Vajro P, Paolella G, Maggiore G, et al. Pediatric celiac disease, cryptogenic hypertransaminasemia, and autoimmune hepatitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013;56:663–70.

41. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:136–60.

42. Matteoni CA, Younossi ZM, Gramlich T, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a spectrum of clinical and pathological severity. Gastroenterology 1999;116:1413–9.

43. McCullough AJ. The clinical features, diagnosis and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis 2004;8:521–33.

44. Ovchinsky N, Moreira RK, Lefkowitch JH, Lavine JE. Liver biopsy in modern clinical practice: a pediatric point-of-view. Adv Anat Pathol 2012;19:250–62.

45. Dezsőfi A, Baumann U, Dhawan A, et al. Liver biopsy in children: position paper of the ESPGHAN Hepatology Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015;60:408–20.

46. Fusillo S, Rudolph B. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pediatr Rev 2015;36:198–205.

47. Harrison SA, Fecht W, Brunt EM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Orlistat for overweight subjects with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A randomized, prospective trial. Hepatology 2009;49:80–6.

48. School health guidelines to promote healthy eating and physical activity. MMWR Recomm Rep 2011;60(Rr-5):1–76.

49. Ouyang X, Cirillo P, Sautin Y, et al. Fructose consumption as a risk factor for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2008;48:993–9.

50. Abdelmalek MF, Suzuki A, Guy C, et al. Increased fructose consumption is associated with fibrosis severity in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2010;51:1961–71.

51. O’Sullivan TA, Oddy WH, Bremner AP, et al. Lower fructose intake may help protect against development of nonalcoholic fatty liver in adolescents with obesity. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58:624–31.

52. Parks EJ, Skokan LE, Timlin MT, Dingfelder CS. Dietary sugars stimulate fatty acid synthesis in adults. J Nutr 2008;138:1039–46.

53. Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest 2009;119:1322–34.

54. Nobili V, Alisi A, Della Corte C, et al., Docosahexaenoic acid for the treatment of fatty liver: randomised controlled trial in children. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2013;23:1066–70.

55. Alisi A, Bedogni G, Baviera G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: The beneficial effects of VSL#3 in obese children with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:1276–85.

56. Vajro P, Franzese A, Valerio G, et al. Lack of efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of liver abnormalities in obese children. J Pediatr 2000;136:739–43.

From the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY.

Abstract

- Objective: To review diagnostic challenges and management strategies in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

- Methods: Review of the literaure.

- Results: NAFLD is common in the United States and should be suspected in overweight or obese children with an elevated serum alanine aminotransferase level. The differential diagnosis for these patients is broad, however, and liver biopsy—the gold standard test—should be undertaken selectively after an appropriate workup. Patients should be counseled on lifestyle modifications, whereas vitamin E therapy can be initiated for those with biopsy-proven disease.

- Conclusion: Providers should have a high degree of suspicion for NAFLD, approaching the workup and diagnosis in an incremental, step-wise fashion. Further research is needed to standardize the diagnostic approach, identify reliable, noninvasive diagnostic measures, and develop novel treatment modalities.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease in the Western world, affecting approximately 10% of children and a third of all adults in the United States [1–3]. It is a significant public health challenge and is estimated to soon be the number one indication for liver transplantation in adults.

NAFLD is a generic term encompassing 2 distinct conditions defined by their histopathology: simple steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Simple steatosis is characterized by predominantly macrovesicular—meaning large droplet—cytoplasmic lipid inclusions found in ≥ 5% of hepatocytes. NASH is defined as hepatic steatosis plus the additional features of inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and/or fibrosis. There are some adult data [4-6] and 1 retrospective pediatric study [7] demonstrating that over time, NAFLD may progress. That is, steatosis may progress to NASH and some patients with fibrosis will ultimately develop cirrhosis. If intervention is provided early in the histologic spectrum, NAFLD can be reversed [4,8] and late complications—such as cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver transplantation—may be prevented.

It is important to highlight that the above definitions are based on histology and that a liver biopsy cannot be reasonably obtained in such a large percentage of the U.S. population. This case-based review will therefore focus primarily on the current diagnostic challenges facing health care providers as well as management strategies in children with presumed NAFLD.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

As you finish your charts at the end of a busy clinic day, you identify 3 patients who may have NAFLD:

History

All 3 patients presented to your office for a routine annual physical before the start of the school year and are asymptomatic. None of the patients has a family history of liver disease and their previously diagnosed comorbidities are listed in the table above. No patient is taking medications other than patient C, who is on metformin.

All 3 children have a smooth, velvety rash on their necks consistent with acanthosis nigricans with an otherwise normal physical exam. The liver and spleen are difficult to palpate but are seemingly normal.

What is the typical presentation for a child with NAFLD?

Most children with NAFLD are asymptomatic, though some may present with vague right upper quadrant abdominal pain. It is unclear, however, if the pain is caused by NAFLD or is rather an unrelated symptom that brings the child to the attention of a physician. In addition, hepatomegaly can be found in over 30% to 40% of patients [9]. For children without abdominal pain or hepatomegaly, most are recognized by an elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or findings of increased liver echogenicity on ultrasonography.

Serum Alanine Aminotransferase

Serum aminotransferases are one of the more common screening tests for NAFLD. However, ALT is highly insensitive at commonly used thresholds and is also nonspecific. As documented in the SAFETY study, the upper limit of normal for ALT in healthy children should be set around 25 U/L in boys and 22 U/L in girls [10]. Yet even at these thresholds, the sensitivity of ALT to diagnose NAFLD is 80% in boys and 92% in girls, whereas specificity is 79% and 85%, respectively [10]. These findings are largely consistent with adult studies [11–14]. Furthermore, ALT does not correlate well with disease severity and children may still have NASH or significant fibrosis with normal values. In a well-characterized cohort of 91 children with biopsy-proven NAFLD, for example, early fibrosis was identified in 12% of children with a normal ALT (≤ 22 U/L for girls and ≤ 25 U/L in boys) [15]. Advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis was seen in 9% of children with an ALT up to 2 times this upper limit [15]. Thus, reliance on the serum ALT may significantly underestimate the prevalence and severity of liver injury.

Ultrasonography

Children with NAFLD typically have findings of increased hepatic echogenicity on abdominal ultrasonography. However, there are multiple limitations to sonography. First, ultrasound is insensitive for identifying mild steatosis if less than 30% of hepatocytes are affected [16,17]. Second, increased hepatic echogenicity is nonspecific and may be caused by inflammation, fibrosis, or intrahepatic accumulation of iron, copper, or glycogen. Third, there can be considerable inter- and intra-operator variability. And lastly, there is some evidence that ultrasounds do not add benefit to diagnosing children with NAFLD [18].

Which patients are at risk for developing hepatic steatosis and NASH?

Weight, Age, and Gender

There is a strong, direct correlation between body mass index (BMI) and NAFLD. The Study of Child and Adolescent Liver Epidemiology (SCALE)—a sentinel pediatric autopsy study of 742 children—found that 5% of normal weight children, 16% of overweight children, and 38% of obese children had NAFLD. The SCALE study also demonstrated an increasing prevalence with age, such that NAFLD was present in 17.3% of 15- to 19-year-olds but only in 0.2% of 2- to 4-year-olds [1]. With regards to gender, NAFLD is roughly twice as prevalent in males [18–20]. While the exact etiology of this difference is unclear, hormonal differences are a leading hypothesis.

Ethnicity

NAFLD is most common in Hispanics, followed by Asians, Caucasians, and African Americans. Research suggests that genetics may be largely responsible for these ethnic disparities. For example, the I148M allele of PNPLA3 (a single nucleotide polymorphism) is strongly associated with steatosis, NASH, and fibrosis [21] and is most common in Hispanics, with a 50% carrier frequency in some cohorts [22]. Conversely, African Americans are more likely to carry the S453I allele of PNPLA3, which is associated with decreased hepatic steatosis [22]. There is also considerable variability within ethnic groups. For example, Mexican-American children appear to be at the highest risk for steatosis or NASH among Hispanics, whereas Filipino-American children are believed to have higher disease prevalence than Cambodian or Vietnamese Americans [1].

Comorbidities

NAFLD is associated with obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, the metabolic syndrome [23], decreased quality of life [24,25], and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). These associations generally hold even after controlling for the other confounders listed. It is important to note that these data come largely from cross-sectional studies and direct causation has yet to be determined.

Insulin resistance in particular is strongly associated with NAFLD—so much so, in fact, that some consider it to be the hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Additionally, children with features of the metabolic syndrome are more likely to have advanced histologic features of NAFLD [23]. There are also intriguing data from small pediatric studies to suggest that OSA may contribute to the development of hepatic fibrosis. In one study of 25 children with biopsy-proven NAFLD, for example, the presence of OSA and hypoxemia correlated with the degree of hepatic fibrosis [26]. In a slightly larger study of 65 children, OSA was also strongly associated with significant hepatic fibrosis (odds ratio, 5.91; 95% confidence interval, 3.23–7.42; P < 0.001). The duration of hypoxemia also correlated with histologic findings of inflammation and circulating biomarkers of apoptosis and fibrogenesis [27].

Other Laboratory Tests

Several studies have documented an association between elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and hepatic fibrosis [28,29], though others have been conflicting [30,31]. Pediatric studies have also demonstrated an inverse correlation between NASH and total bilirubin [32], serum potassium [33], and serum ceruloplasmin [34]. In addition, there are a number of serum biomarkers or biomarker panels commercially available for use in adults. Because similar efficacy data are unavailable in children, however, serum biomarkers should be primarily used for research purposes only.

Who should be screened for NAFLD? And how?

Published professional society recommendations differ significantly with regards to screening. In 2007, the American Academy of Pediatrics suggested screening obese children over 10 years of age or overweight children with additional risk factors with biannual liver tests [35]. There were no management recommendations made for elevated aminotransferase levels other than for subspecialty referral. In 2012, the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) recommended obtaining an ultrasound and liver tests in every obese child [36]. One month later, however, the American Gastroenterological Association, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, and the American College of Gastroenterology published joint guidelines without screening recommendations “due to a paucity of evidence” [37].

Because these statements conflict and are based heavily on expert opinion, one should consider the risks, benefits, and costs to screening large numbers of patients. Until additional research clarifies this controversy, we suggest that providers individualize their screening practices to their population and the risks of each individual patient. For example, we would consider screening children who are obese; Hispanic or Asian; have multiple features of the metabolic syndrome; and/or those who have a family history of NAFLD. Further, we recommend screening children for NAFLD with serum liver enzymes only and not with ultrasonography.

Case Continued: Laboratory Results

ALT and GGT tests are ordered and the results are as follows:

What is the differential for children with suspected NAFLD?

Autoimmune Hepatitis (AIH)

AIH is a progressive necro-inflammatory disorder of the liver characterized by elevated aminotransferases, positive autoantibodies, and distinctive histologic features. AIH is believed to occur in genetically predisposed patients in response to an environmental trigger. There is a female predominance and it can present in any age or ethnic group.

AIH is divided in 2 subtypes. Type 1 disease is characterized by a positive antinuclear (ANA) antibody and anti-smooth muscle antibody. More commonly, it presents in adolescence with an indolent course—many patients are asymptomatic until they develop features of cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Conversely, type 2 AIH is characterized by a positive liver kidney microsomal (LKM) antibody and tends to present acutely in young children. It is important to note that antibody titers can be falsely positive in a significant percentage of patients and, in such cases, are often mildly elevated [38]. We strongly suggest children with positive autoantibody titers be evaluated by a specialist.

Treatment should be started promptly to avoid progression to cirrhosis and should also done so in consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist or hepatologist. The prognosis of AIH with immunosuppression is favorable, with long-term remission rates of approximately 80%. Transplantation is typically required in the remaining 10% to 20% [39].

Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune, inflammatory enteropathy caused by exposure to gluten in genetically susceptible individuals. Up to a third of all children presenting with celiac will have an elevated serum ALT [40]. Additional symptoms/features are both variable and nonspecific: abdominal pain, poor growth, diarrhea, or constipation, among others. Celiac is diagnosed by duodenal biopsy or a sufficiently elevated tissue transglutaminase antibody level [41]. Treatment with a strict gluten-free diet will resolve the enteropathy and normalize the serum aminotransferases.

Wilson’s Disease

Wilson’s disease is a metabolic disorder leading to copper deposition in the liver, brain, cornea, and kidneys. It is caused by an ATP7B gene mutation and inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. Patients may present with asymptomatic liver disease, chronic hepatitis, acute liver failure, or with symptoms of portal hypertension. Neuropsychiatric symptoms may also be prominent. Screening tests include a serum ceruloplasmin and 24-hour urinary copper quantification. Because diagnosing Wilson’s disease can be challenging, however, further testing should occur in consultation with a pediatric gastroenterologist or hepatologist.

Viral Hepatitis

Chronic viral infections such as hepatitis B and C are still common etiologies of liver disease in the United States. However, universal vaccination and blood donor screening have reduced the risk of transmission; new antiviral agents will likely further decrease the prevalence and transmission risk over time. Acute viral hepatitis—cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis A, or hepatitis E—should also be considered in children who present with appropriate symptoms and an elevated ALT.

Drug-Induced

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) can present with elevated serum aminotransferases (hepatocellular pattern), an elevated bilirubin (cholestatic pattern), or a mixed picture. Idiosyncratic DILI in children is commonly caused by antimicrobial or central nervous system agents and usually presents with a hepatocellular injury pattern. Substance abuse, including alcohol, is common and should also be investigated as the source of underlying liver disease.

Muscle Disease

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and ALT are present in hepatocytes, myocytes, and red blood cells, among other tissues. Thus, children with congenital myopathies or myositis can have elevated aminotransferases, typically with the AST higher than the ALT. In these patients, checking a creatine phosphokinase (CPK) level may lead to the correct diagnosis and limit unnecessary testing.

Other Metabolic Disorders

Myriad metabolic disorders present with liver disease and/or elevated serum aminotransferase levels. Individually, these conditions are rare but, collectively, are relatively common. Two of the more occult conditions—lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D) and alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1A) deficiency—are discussed in further detail below.

LAL-D is an autosomal recessive disease resulting in the accumulation of cholesterol esters and triglycerides in lysosomes. Patients typically present with hepatomegaly and mildly elevated aminotransferases, an elevated LDL, low HDL cholesterol, and increased hepatic echogenicity on ultrasound. If a biopsy is obtained, microvesicular steatosis is predominant as opposed to macrovesicular steatosis found in NAFLD. The diagnosis of LAL-D can be made on a commercially available dry blood spot enzymatic assay or genetic testing and treatment has recently been FDA approved.

A1A deficiency is an autosomal recessive disease diagnosable by an alpha-1-antitrypsin phenotype. The clinical presentation is characterized by neonatal cholestasis in the infantile form and by hepatitis, cirrhosis and portal hypertension in older children. Classic symptoms of emphysema and chronic lung disease present in adulthood.

What further testing should be performed in children with suspected NAFLD?

For obese children with an elevated ALT or evidence of increased hepatic echogenicity, ESPGHAN recommends targeting the workup according to the child’s age [36]. According to their consensus statement, they recommend an upfront, thorough laboratory evaluation in children less than 10 years of age and consideration of a liver biopsy upon completion. For children over 10 years of age at low risk for NASH or fibrosis, additional laboratory evaluation is suggested 3 to 6 months after failed lifestyle interventions. In general, the recommended workup includes testing for conditions discussed in the section above such as viral hepatitis, AIH, Wilson’s disease, and others. If negative, ESPGHAN states that a liver biopsy should be “considered.”

The question of whether or not to obtain a liver biopsy is controversial, though there are several clear advantages to doing so. First, biopsy is the gold standard test for diagnosing NAFLD and there are no highly accurate, noninvasive tests currently approved for use in children. Second, biopsy is a more definitive means of ruling out competing diagnoses such as AIH. Third, biopsy may provide prognostic data. In a retrospective adult study of 136 patients, for example, those who presented with simple steatosis had a roughly 3% chance of progressing to cirrhosis within 10 years. If a patient within this cohort presented with NASH, however, the progression risk was approximately 30% within 5 years [42,43]. Fourth, due to potential side effects of medications, position papers recommend obtaining a liver biopsy prior to the initiation of pharmacotherapy [37]. Lastly, the risk for serious morbidity from a liver biopsy is low [44,45]. Alternatively, one must acknowledge the risks of liver biopsy: morbidity, sampling bias, invasiveness, cost, and sedation risks in children.

Case Continued: Biopsy Results

You refer your patients to a gastroenterologist. Tests for viral hepatitis, A1A deficiency, celiac disease, muscle disorders, Wilson’s disease, and AIH are negative. Ultimately, a liver biopsy is performed on all 3 children without complications. The results are presented below.

What is the treatment of NAFLD?

Lifestyle Modification

Lifestyle modifications are the mainstay of treatment for NAFLD. In adult studies, weight loss of more than 5% reduces hepatic steatosis whereas weight loss of more than 9% improves or eliminates NASH [47]. We recommend that children engage in age-appropriate, enjoyable, moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic activity for 60 minutes a day [48]. In addition, there should be a focus on reducing sedentary behavior by limiting screen time and a concerted effort to engage the family in lifestyle modifications.

Dietary interventions to treat NAFLD are less concrete but there is a growing body of literature to suggest that dietary fructose is particularly harmful. In adults, for example, fructose consumption is associated with the development of NAFLD [49] and hepatic fibrosis [50]. Recent data in adolescents has similarly documented an association between NAFLD incidence and energy-adjusted fructose intake [51]. It is worth highlighting that these clinical findings are also biologically plausible, as fructose is primarily metabolized within hepatocytes and has recently been shown to increase de novo lipogenesis [52,53]. In general, we suggest a well-balanced diet of unprocessed foods—that is, with limited added sugars—sufficient to induce gradual weight loss in older children or body weight maintenance in younger children.

Medications

Vitamin E is the only medication with proven efficacy in children, as demonstrated in the TONIC trial [20]. TONIC was a double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled study with 3 treatment arms: 800 IU of vitamin E daily, 1000 mg of metformin daily, or placebo. Metformin did not reduce the serum ALT or significantly improve liver histology and should therefore not be used for these indications. However, patients treated with vitamin E had a statistically significant improvement in the NAFLD activity score (a histologic grading system comprising steatosis, inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning) and resolution of NASH when compared to placebo. For these reasons—as well as a paucity of other viable treatment options—vitamin E is routinely prescribed for children with biopsy-proven NASH. However, the long- term risks of high-dose vitamin E therapy in children are largely unknown.

Polyunsaturated fats such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [54] and probiotics such as VSL #3 [55] have showed efficacy reducing hepatic steatosis in small, randomized clinical trials. Both medications need to be further validated before they can be recommended for use in children. Conversely, ursodeoxycholic acid has not been found to be efficacious in children with NAFLD [56], whereas phase IIb data on cysteamine is expected soon. There are currently insufficient data to recommend bariatric surgery as treatment for NAFLD in adolescence.

Case Continued: Follow-up

After their biopsies, both patients with NASH (patients A and B) are started on vitamin E therapy. All 3 patients continue to report for follow-up visits without short-term complications, though they have still been unable to significantly reduce their body mass index and have a persistently elevated serum ALT.

Summary

NAFLD is a common condition in the United States with serious personal and public health ramifications. This case-based review highlights the diagnostic and management challenges in children with NAFLD and the unique role primary care providers play in caring for these patients.

Corresponding author: Bryan Rudolph, MD, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, 3415 Bainbridge Ave., Bronx, NY 10467, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, Bronx, NY.

Abstract

- Objective: To review diagnostic challenges and management strategies in children with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

- Methods: Review of the literaure.

- Results: NAFLD is common in the United States and should be suspected in overweight or obese children with an elevated serum alanine aminotransferase level. The differential diagnosis for these patients is broad, however, and liver biopsy—the gold standard test—should be undertaken selectively after an appropriate workup. Patients should be counseled on lifestyle modifications, whereas vitamin E therapy can be initiated for those with biopsy-proven disease.

- Conclusion: Providers should have a high degree of suspicion for NAFLD, approaching the workup and diagnosis in an incremental, step-wise fashion. Further research is needed to standardize the diagnostic approach, identify reliable, noninvasive diagnostic measures, and develop novel treatment modalities.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver disease in the Western world, affecting approximately 10% of children and a third of all adults in the United States [1–3]. It is a significant public health challenge and is estimated to soon be the number one indication for liver transplantation in adults.

NAFLD is a generic term encompassing 2 distinct conditions defined by their histopathology: simple steatosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Simple steatosis is characterized by predominantly macrovesicular—meaning large droplet—cytoplasmic lipid inclusions found in ≥ 5% of hepatocytes. NASH is defined as hepatic steatosis plus the additional features of inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, and/or fibrosis. There are some adult data [4-6] and 1 retrospective pediatric study [7] demonstrating that over time, NAFLD may progress. That is, steatosis may progress to NASH and some patients with fibrosis will ultimately develop cirrhosis. If intervention is provided early in the histologic spectrum, NAFLD can be reversed [4,8] and late complications—such as cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, or liver transplantation—may be prevented.

It is important to highlight that the above definitions are based on histology and that a liver biopsy cannot be reasonably obtained in such a large percentage of the U.S. population. This case-based review will therefore focus primarily on the current diagnostic challenges facing health care providers as well as management strategies in children with presumed NAFLD.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

As you finish your charts at the end of a busy clinic day, you identify 3 patients who may have NAFLD:

History

All 3 patients presented to your office for a routine annual physical before the start of the school year and are asymptomatic. None of the patients has a family history of liver disease and their previously diagnosed comorbidities are listed in the table above. No patient is taking medications other than patient C, who is on metformin.

All 3 children have a smooth, velvety rash on their necks consistent with acanthosis nigricans with an otherwise normal physical exam. The liver and spleen are difficult to palpate but are seemingly normal.

What is the typical presentation for a child with NAFLD?

Most children with NAFLD are asymptomatic, though some may present with vague right upper quadrant abdominal pain. It is unclear, however, if the pain is caused by NAFLD or is rather an unrelated symptom that brings the child to the attention of a physician. In addition, hepatomegaly can be found in over 30% to 40% of patients [9]. For children without abdominal pain or hepatomegaly, most are recognized by an elevated serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or findings of increased liver echogenicity on ultrasonography.

Serum Alanine Aminotransferase

Serum aminotransferases are one of the more common screening tests for NAFLD. However, ALT is highly insensitive at commonly used thresholds and is also nonspecific. As documented in the SAFETY study, the upper limit of normal for ALT in healthy children should be set around 25 U/L in boys and 22 U/L in girls [10]. Yet even at these thresholds, the sensitivity of ALT to diagnose NAFLD is 80% in boys and 92% in girls, whereas specificity is 79% and 85%, respectively [10]. These findings are largely consistent with adult studies [11–14]. Furthermore, ALT does not correlate well with disease severity and children may still have NASH or significant fibrosis with normal values. In a well-characterized cohort of 91 children with biopsy-proven NAFLD, for example, early fibrosis was identified in 12% of children with a normal ALT (≤ 22 U/L for girls and ≤ 25 U/L in boys) [15]. Advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis was seen in 9% of children with an ALT up to 2 times this upper limit [15]. Thus, reliance on the serum ALT may significantly underestimate the prevalence and severity of liver injury.

Ultrasonography

Children with NAFLD typically have findings of increased hepatic echogenicity on abdominal ultrasonography. However, there are multiple limitations to sonography. First, ultrasound is insensitive for identifying mild steatosis if less than 30% of hepatocytes are affected [16,17]. Second, increased hepatic echogenicity is nonspecific and may be caused by inflammation, fibrosis, or intrahepatic accumulation of iron, copper, or glycogen. Third, there can be considerable inter- and intra-operator variability. And lastly, there is some evidence that ultrasounds do not add benefit to diagnosing children with NAFLD [18].

Which patients are at risk for developing hepatic steatosis and NASH?

Weight, Age, and Gender