User login

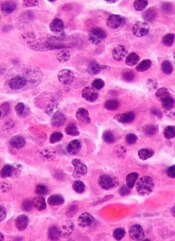

Antibody recognizes human plasma cells

Researchers say they have generated a monoclonal antibody that could have diagnostic and therapeutic applications for multiple myeloma (MM) and other plasma cell disorders.

The team generated this antibody, VLRB MM3, from immunized lampreys, a type of jawless fish.

Experiments with VLRB MM3 showed that it can identify normal plasma cells in samples from healthy donors and malignant plasma cells in samples from patients with MM.

Götz Ehrhardt, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and his colleagues described this work in JCI Insight.

The researchers noted that antibody-secreting plasma cells arise from B-cell precursors and are essential for adaptive immune responses against invading pathogens. Plasma cell dysfunction is associated with autoimmune and neoplastic disorders, including MM.

Surface markers that are specific to plasma cells have not been identified, and antibodies that only recognize these cells have been challenging to generate using conventional systems.

However, Dr Ehrhardt and his colleagues found they could generate a plasma-cell-specific antibody from immunized lampreys.

The researchers injected lamprey larvae with a bone marrow isolate from an MM patient and screened the resulting monoclonal antibodies for those that recognized both malignant and non-malignant plasma cells.

Further characterization of the antibody VLRB MM3 revealed that it is specific to plasma cells and does not recognize other B-cell populations or progenitors.

VLRB MM3 binding was shown to coincide with CD38 dimerization and correlate with and impede the NAD glycohydrolase activity of this glycoprotein.

Considering these findings together, the researchers concluded that VLRB MM3 represents a unique tool that might aid the treatment and diagnosis of plasma cell disorders. ![]()

Researchers say they have generated a monoclonal antibody that could have diagnostic and therapeutic applications for multiple myeloma (MM) and other plasma cell disorders.

The team generated this antibody, VLRB MM3, from immunized lampreys, a type of jawless fish.

Experiments with VLRB MM3 showed that it can identify normal plasma cells in samples from healthy donors and malignant plasma cells in samples from patients with MM.

Götz Ehrhardt, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and his colleagues described this work in JCI Insight.

The researchers noted that antibody-secreting plasma cells arise from B-cell precursors and are essential for adaptive immune responses against invading pathogens. Plasma cell dysfunction is associated with autoimmune and neoplastic disorders, including MM.

Surface markers that are specific to plasma cells have not been identified, and antibodies that only recognize these cells have been challenging to generate using conventional systems.

However, Dr Ehrhardt and his colleagues found they could generate a plasma-cell-specific antibody from immunized lampreys.

The researchers injected lamprey larvae with a bone marrow isolate from an MM patient and screened the resulting monoclonal antibodies for those that recognized both malignant and non-malignant plasma cells.

Further characterization of the antibody VLRB MM3 revealed that it is specific to plasma cells and does not recognize other B-cell populations or progenitors.

VLRB MM3 binding was shown to coincide with CD38 dimerization and correlate with and impede the NAD glycohydrolase activity of this glycoprotein.

Considering these findings together, the researchers concluded that VLRB MM3 represents a unique tool that might aid the treatment and diagnosis of plasma cell disorders. ![]()

Researchers say they have generated a monoclonal antibody that could have diagnostic and therapeutic applications for multiple myeloma (MM) and other plasma cell disorders.

The team generated this antibody, VLRB MM3, from immunized lampreys, a type of jawless fish.

Experiments with VLRB MM3 showed that it can identify normal plasma cells in samples from healthy donors and malignant plasma cells in samples from patients with MM.

Götz Ehrhardt, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and his colleagues described this work in JCI Insight.

The researchers noted that antibody-secreting plasma cells arise from B-cell precursors and are essential for adaptive immune responses against invading pathogens. Plasma cell dysfunction is associated with autoimmune and neoplastic disorders, including MM.

Surface markers that are specific to plasma cells have not been identified, and antibodies that only recognize these cells have been challenging to generate using conventional systems.

However, Dr Ehrhardt and his colleagues found they could generate a plasma-cell-specific antibody from immunized lampreys.

The researchers injected lamprey larvae with a bone marrow isolate from an MM patient and screened the resulting monoclonal antibodies for those that recognized both malignant and non-malignant plasma cells.

Further characterization of the antibody VLRB MM3 revealed that it is specific to plasma cells and does not recognize other B-cell populations or progenitors.

VLRB MM3 binding was shown to coincide with CD38 dimerization and correlate with and impede the NAD glycohydrolase activity of this glycoprotein.

Considering these findings together, the researchers concluded that VLRB MM3 represents a unique tool that might aid the treatment and diagnosis of plasma cell disorders. ![]()

Night of the Living Thrips: An Unusual Outbreak of Thysanoptera Dermatitis

Case Reports

A platoon of 24 US Marines participated in a 1-week outdoor training exercise (February 4–8) at the Marine Corps Training Area Bellows in Oahu, Hawaii. During the last 3 days of training, 15 (62.5%) marines presented to the same primary care provider with what appeared to be diffuse scattered lesions on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands. All 15 patients reported that they noticed the lesions upon waking up the morning after their second night at the training area. The patients were unable to recollect specific direct arthropod interactions, but they reported the presence of “bugs” in the training area and denied use of any insect repellents, insect nets, or sunscreen. Sleeping arrangements varied from covered vehicles and cots to sleeping bags on the ground, which were laundered independently by each marine and thereby were ruled out as a commonality. The patients denied working with any chemicals or cleansers while in the field. Further questioning of all 15 patients revealed a history of extended contact with live foliage as branches were broken off to build camouflaged sites.

The following week, a second platoon of 20 marines occupied a separate undisturbed portion of the same training area for a similar 1-week training evolution. Manifestation of similar symptoms among members of the second group, who had no contact with the initial 15 patients, supported the likely environmental etiology of the eruptions.

|

| Figure 1. Numerous well-circumscribed, discrete, pink-red papules diffusely scattered across the face. |

|

| Figure 2. Papules with classic anemic halos. |

Referral

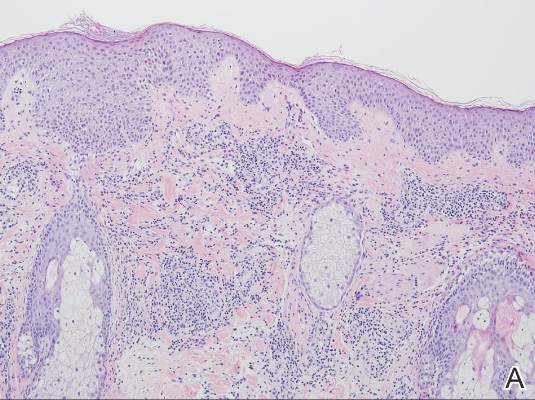

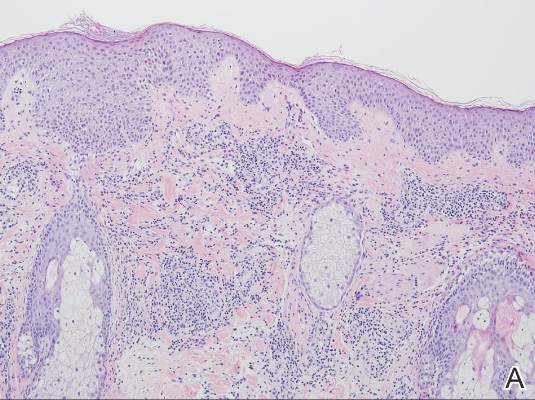

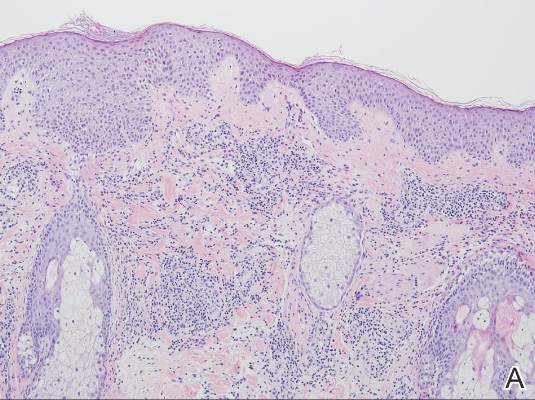

Two patients from the first group were evaluated at the dermatology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, Hawaii) on day 10 of the initial outbreak. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous discrete, pink-red, well-circumscribed, 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped papules exclusive to exposed areas on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands (Figures 1 and 2). Anemic halos surrounding the hand papules were noted (Figure 2). A punch biopsy in both patients revealed spongiotic dermatitis with superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic inflammation with eosinophils, suggestive of an arthropod bite (Figure 3). No retained arthropod parts wereidentified. Both patients were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily for 7 days with total resolution of the lesions.

Site Survey Results

Five days following the initial presentation of the first outbreak, a daytime site survey of the training area was conducted by a medical entomologist, an environmental health scientist, and a wildlife biologist. Records indicated that prior to the current utilization, the training area had not been used for 9 months. Approximately half of the training area was covered with mixed scrub vegetation and the remainder was clear pavement or sand (clear of vegetation). Feral hogs (Sus scrofa), cats (Felis domesticus), and mongooses (Herpestes javanicus) were observed at the site. Patient interviews and site survey ruled out a number of potential environmental irritants, including contact with fresh or salt water and chemical contaminants in the air or soil.

Because biting insects were suspected as the cause of the eruptions, an overnight entomological survey was conducted 3 weeks after the first outbreak under similar weather conditions and was centered in the area of an Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) forest where most of the marines had slept during training. Mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus) were observed in the area, with an estimated biting rate of 1 to 2 bites per hour. Centipedes (Scolopendra subspinipes) were commonly observed after dark. There was no sign of heavy bird roosting or nesting, which would be a possible source of biting ectoparasites. Other than the Australian pine, notable vegetation present included Christmasberry (Schinus terebinthifolius), koa haole (Leucaena leucocephala), and Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa). A survey of the vegetation uncovered no notable insects, and no damage to the leaves of the Chinese banyans, which is typical of thrip infestation, was noted.

|

|

| Figure 3. Superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) with lymphocytic predominance (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). | |

After completion of a resource-intensive investigation that included site survey, literature review, detailed patient history including thrips-associated skin manifestations, and thorough consultation with local dermatologists and entomologists, the findings seemingly pointed to thrips as the most likely etiology of the eruption seen in our patients and a diagnosis of Thysanoptera dermatitis was made.

Comment

Thrips are small winged insects in the order Thysanoptera, which comprises more than 5000 identified species ranging in size from 0.5 to 15 mm, though most are approximately 1 mm.1 The insects typically are phytophagous (feeding on plants) and are attracted to humidity and seemingly the sweat of animals and humans.2 Although largely a phytophagous organism, a few published cases of thrips exposure reported papular skin eruptions known as Thysanoptera dermatitis.3-8 Several species of thrips across the globe have been associated with incidental attacks on humans to include “Heliothrips indicus Bagnall, a cotton pest of the Sudan; Thrips imagines Bagnall, reported in Australia; Limothrips cerealium (Haliday), in Germany; Gynaitkothrips uzeli Zimmerman, in Algeria; and other species.”7 In Hawaii, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Cuban laurel thrips) is a common pest of the Chinese banyan tree (F microcarpa) tree.9

A case series reported by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in the late 1960s of military personnel stationed in Oahu described exposure to similar environmental conditions with resultant lesions that were nearly identical to those seen in our patients. The final conclusion of the investigation was that Cuban laurel thrips were the likely etiology, though mites also were considered.5 In a subsequent commentary in 1968, Waisman10 reported similar eruptions in hospitalized patients with further comment regarding the nocturnal occurrence of the bites. Additionally, the eruptions were reported to be short lasting and devoid of discomfort, similar to our patient population.10

Following suit, Aeling6 published a case series in 1974 depicting several service members who presented with symptoms that were nearly identical to the symptoms experienced by our patients as well as those of Goldstein and Skipworth.5 The investigator coined the term hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii to describe the findings and further reported that Hawaiian dermatologists were familiar with the symptoms and clinical presentation of the disease. Patients in this outbreak had observed small flying insects, similar to the reports from our patients, and postulated that the symptoms occurred secondary to insect bites.6

Since the report by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in 1968, the majority of the literature regarding Thysanoptera dermatitis has largely been in case reports. In 1987, Fishman7 reported the case of a 43-year-old woman who presented with a palm-sized area of grouped red puncta on the lateral neck with the subsequent entrapment and identification of a flower thrips from the patient’s clothing. In 2005, Leigheb et al2 reported the case of a 30-year-old man with an erythematous papular cutaneous eruption on the anterior chest. In this case, the causative etiology was unequivocally confirmed upon identification of the presence of thrips on biopsy.2 In 2006, Guarneri et al1 reported the case of a 59-year-old farmer who had tentatively been diagnosed with delusional parasitosis until persistent presentation to a dermatologist for evaluation enabled the capture and identification of grain thrips. More recently, another case of likely Thysanoptera dermatitis was published in 2012 after a man presented with a slide-mounted thrip from his skin for evaluation as to a potential cause of a recurrent rash he had been experiencing.11 In all of these cases, it was fortunate that a specific organism could be identified for 2 reasons: (1) members of the order Thysanoptera have a biological cycle of only 11 to 36 days, and (2) thrips may go virtually unnoticed by humans, as they are often difficult to see due to their small size.2,12 Perhaps the most extensive report, however, comes from Childers et al8 in a descriptive case series published in 2005. In this report, the investigators provided a thorough detailing of multiple encounters dating back to 1883 through which patients were inadvertently exposed to various species of thrips and subsequently presented with arthropod bites.

Conclusion

The rapid and clustered manner of patient presentation in this case series makes it unique and highlights the need for further consideration of Thysanoptera dermatitis as a potential etiology for an outbreak of a papular eruption. Further reporting may help to better contextualize the true epidemiology of the condition and subsequently may trigger its greater inclusion in the differential diagnosis for a pruritic papular eruption.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Amy Spizuoco, DO (New York, New York), for her assistance with the initial diagnosis; Steve Montgomery, PhD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for his assistance with further entomological discussion of potential etiologies; and John R. Gilstad, MD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for contributing his thoughts on the differential diagnosis of the presenting symptoms.

1. Guarneri F, Guarneri C, Mento G, et al. Pseudo‐delusory syndrome caused by Limothrips cerealium. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:197-199.

2. Leigheb G, Tiberio R, Filosa G, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:722-724.

3. Williams CB. A blood sucking thrips. The Entomologist. 1921;54:164.

4. Bailey SF. Thrips attacking man. Can Entomol. 1936;68:95-98.

5. Goldstein N, Skipworth GB. Papular eruption secondary to thrips bites. JAMA. 1968;203:53-55.

6. Aeling JL. Hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii. Cutis. 1974;14:541-544.

7. Fishman HC. Thrips. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:993.

8. Childers CC, Beshear RJ, Frantz G, et al. A review of thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986-1997. Florida Entomologist. 2005;88:447-451.

9. Funasaki GY. Studies on the life cycle and propagation technique of Montandoniola moraguesi (Puton)(Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Proc Hawaii Entomol Soc. 1966;XIX.2:209-211.

10. Waisman M. Thrips bites dermatitis. JAMA. 1968;204:82.

11. Martin J, Richmond A, Davis BM, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis presenting as folie à deux. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:864-865.

12. Cooper RG. Dermatitis & conjunctivitis in workers on an ostrich farm following thrips infestation. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:588-589.

Case Reports

A platoon of 24 US Marines participated in a 1-week outdoor training exercise (February 4–8) at the Marine Corps Training Area Bellows in Oahu, Hawaii. During the last 3 days of training, 15 (62.5%) marines presented to the same primary care provider with what appeared to be diffuse scattered lesions on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands. All 15 patients reported that they noticed the lesions upon waking up the morning after their second night at the training area. The patients were unable to recollect specific direct arthropod interactions, but they reported the presence of “bugs” in the training area and denied use of any insect repellents, insect nets, or sunscreen. Sleeping arrangements varied from covered vehicles and cots to sleeping bags on the ground, which were laundered independently by each marine and thereby were ruled out as a commonality. The patients denied working with any chemicals or cleansers while in the field. Further questioning of all 15 patients revealed a history of extended contact with live foliage as branches were broken off to build camouflaged sites.

The following week, a second platoon of 20 marines occupied a separate undisturbed portion of the same training area for a similar 1-week training evolution. Manifestation of similar symptoms among members of the second group, who had no contact with the initial 15 patients, supported the likely environmental etiology of the eruptions.

|

| Figure 1. Numerous well-circumscribed, discrete, pink-red papules diffusely scattered across the face. |

|

| Figure 2. Papules with classic anemic halos. |

Referral

Two patients from the first group were evaluated at the dermatology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, Hawaii) on day 10 of the initial outbreak. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous discrete, pink-red, well-circumscribed, 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped papules exclusive to exposed areas on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands (Figures 1 and 2). Anemic halos surrounding the hand papules were noted (Figure 2). A punch biopsy in both patients revealed spongiotic dermatitis with superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic inflammation with eosinophils, suggestive of an arthropod bite (Figure 3). No retained arthropod parts wereidentified. Both patients were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily for 7 days with total resolution of the lesions.

Site Survey Results

Five days following the initial presentation of the first outbreak, a daytime site survey of the training area was conducted by a medical entomologist, an environmental health scientist, and a wildlife biologist. Records indicated that prior to the current utilization, the training area had not been used for 9 months. Approximately half of the training area was covered with mixed scrub vegetation and the remainder was clear pavement or sand (clear of vegetation). Feral hogs (Sus scrofa), cats (Felis domesticus), and mongooses (Herpestes javanicus) were observed at the site. Patient interviews and site survey ruled out a number of potential environmental irritants, including contact with fresh or salt water and chemical contaminants in the air or soil.

Because biting insects were suspected as the cause of the eruptions, an overnight entomological survey was conducted 3 weeks after the first outbreak under similar weather conditions and was centered in the area of an Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) forest where most of the marines had slept during training. Mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus) were observed in the area, with an estimated biting rate of 1 to 2 bites per hour. Centipedes (Scolopendra subspinipes) were commonly observed after dark. There was no sign of heavy bird roosting or nesting, which would be a possible source of biting ectoparasites. Other than the Australian pine, notable vegetation present included Christmasberry (Schinus terebinthifolius), koa haole (Leucaena leucocephala), and Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa). A survey of the vegetation uncovered no notable insects, and no damage to the leaves of the Chinese banyans, which is typical of thrip infestation, was noted.

|

|

| Figure 3. Superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) with lymphocytic predominance (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). | |

After completion of a resource-intensive investigation that included site survey, literature review, detailed patient history including thrips-associated skin manifestations, and thorough consultation with local dermatologists and entomologists, the findings seemingly pointed to thrips as the most likely etiology of the eruption seen in our patients and a diagnosis of Thysanoptera dermatitis was made.

Comment

Thrips are small winged insects in the order Thysanoptera, which comprises more than 5000 identified species ranging in size from 0.5 to 15 mm, though most are approximately 1 mm.1 The insects typically are phytophagous (feeding on plants) and are attracted to humidity and seemingly the sweat of animals and humans.2 Although largely a phytophagous organism, a few published cases of thrips exposure reported papular skin eruptions known as Thysanoptera dermatitis.3-8 Several species of thrips across the globe have been associated with incidental attacks on humans to include “Heliothrips indicus Bagnall, a cotton pest of the Sudan; Thrips imagines Bagnall, reported in Australia; Limothrips cerealium (Haliday), in Germany; Gynaitkothrips uzeli Zimmerman, in Algeria; and other species.”7 In Hawaii, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Cuban laurel thrips) is a common pest of the Chinese banyan tree (F microcarpa) tree.9

A case series reported by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in the late 1960s of military personnel stationed in Oahu described exposure to similar environmental conditions with resultant lesions that were nearly identical to those seen in our patients. The final conclusion of the investigation was that Cuban laurel thrips were the likely etiology, though mites also were considered.5 In a subsequent commentary in 1968, Waisman10 reported similar eruptions in hospitalized patients with further comment regarding the nocturnal occurrence of the bites. Additionally, the eruptions were reported to be short lasting and devoid of discomfort, similar to our patient population.10

Following suit, Aeling6 published a case series in 1974 depicting several service members who presented with symptoms that were nearly identical to the symptoms experienced by our patients as well as those of Goldstein and Skipworth.5 The investigator coined the term hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii to describe the findings and further reported that Hawaiian dermatologists were familiar with the symptoms and clinical presentation of the disease. Patients in this outbreak had observed small flying insects, similar to the reports from our patients, and postulated that the symptoms occurred secondary to insect bites.6

Since the report by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in 1968, the majority of the literature regarding Thysanoptera dermatitis has largely been in case reports. In 1987, Fishman7 reported the case of a 43-year-old woman who presented with a palm-sized area of grouped red puncta on the lateral neck with the subsequent entrapment and identification of a flower thrips from the patient’s clothing. In 2005, Leigheb et al2 reported the case of a 30-year-old man with an erythematous papular cutaneous eruption on the anterior chest. In this case, the causative etiology was unequivocally confirmed upon identification of the presence of thrips on biopsy.2 In 2006, Guarneri et al1 reported the case of a 59-year-old farmer who had tentatively been diagnosed with delusional parasitosis until persistent presentation to a dermatologist for evaluation enabled the capture and identification of grain thrips. More recently, another case of likely Thysanoptera dermatitis was published in 2012 after a man presented with a slide-mounted thrip from his skin for evaluation as to a potential cause of a recurrent rash he had been experiencing.11 In all of these cases, it was fortunate that a specific organism could be identified for 2 reasons: (1) members of the order Thysanoptera have a biological cycle of only 11 to 36 days, and (2) thrips may go virtually unnoticed by humans, as they are often difficult to see due to their small size.2,12 Perhaps the most extensive report, however, comes from Childers et al8 in a descriptive case series published in 2005. In this report, the investigators provided a thorough detailing of multiple encounters dating back to 1883 through which patients were inadvertently exposed to various species of thrips and subsequently presented with arthropod bites.

Conclusion

The rapid and clustered manner of patient presentation in this case series makes it unique and highlights the need for further consideration of Thysanoptera dermatitis as a potential etiology for an outbreak of a papular eruption. Further reporting may help to better contextualize the true epidemiology of the condition and subsequently may trigger its greater inclusion in the differential diagnosis for a pruritic papular eruption.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Amy Spizuoco, DO (New York, New York), for her assistance with the initial diagnosis; Steve Montgomery, PhD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for his assistance with further entomological discussion of potential etiologies; and John R. Gilstad, MD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for contributing his thoughts on the differential diagnosis of the presenting symptoms.

Case Reports

A platoon of 24 US Marines participated in a 1-week outdoor training exercise (February 4–8) at the Marine Corps Training Area Bellows in Oahu, Hawaii. During the last 3 days of training, 15 (62.5%) marines presented to the same primary care provider with what appeared to be diffuse scattered lesions on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands. All 15 patients reported that they noticed the lesions upon waking up the morning after their second night at the training area. The patients were unable to recollect specific direct arthropod interactions, but they reported the presence of “bugs” in the training area and denied use of any insect repellents, insect nets, or sunscreen. Sleeping arrangements varied from covered vehicles and cots to sleeping bags on the ground, which were laundered independently by each marine and thereby were ruled out as a commonality. The patients denied working with any chemicals or cleansers while in the field. Further questioning of all 15 patients revealed a history of extended contact with live foliage as branches were broken off to build camouflaged sites.

The following week, a second platoon of 20 marines occupied a separate undisturbed portion of the same training area for a similar 1-week training evolution. Manifestation of similar symptoms among members of the second group, who had no contact with the initial 15 patients, supported the likely environmental etiology of the eruptions.

|

| Figure 1. Numerous well-circumscribed, discrete, pink-red papules diffusely scattered across the face. |

|

| Figure 2. Papules with classic anemic halos. |

Referral

Two patients from the first group were evaluated at the dermatology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center (Honolulu, Hawaii) on day 10 of the initial outbreak. Cutaneous examination revealed numerous discrete, pink-red, well-circumscribed, 2- to 4-mm, dome-shaped papules exclusive to exposed areas on the face, neck, and dorsal aspect of the hands (Figures 1 and 2). Anemic halos surrounding the hand papules were noted (Figure 2). A punch biopsy in both patients revealed spongiotic dermatitis with superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic inflammation with eosinophils, suggestive of an arthropod bite (Figure 3). No retained arthropod parts wereidentified. Both patients were treated with triamcinolone ointment twice daily for 7 days with total resolution of the lesions.

Site Survey Results

Five days following the initial presentation of the first outbreak, a daytime site survey of the training area was conducted by a medical entomologist, an environmental health scientist, and a wildlife biologist. Records indicated that prior to the current utilization, the training area had not been used for 9 months. Approximately half of the training area was covered with mixed scrub vegetation and the remainder was clear pavement or sand (clear of vegetation). Feral hogs (Sus scrofa), cats (Felis domesticus), and mongooses (Herpestes javanicus) were observed at the site. Patient interviews and site survey ruled out a number of potential environmental irritants, including contact with fresh or salt water and chemical contaminants in the air or soil.

Because biting insects were suspected as the cause of the eruptions, an overnight entomological survey was conducted 3 weeks after the first outbreak under similar weather conditions and was centered in the area of an Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) forest where most of the marines had slept during training. Mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus) were observed in the area, with an estimated biting rate of 1 to 2 bites per hour. Centipedes (Scolopendra subspinipes) were commonly observed after dark. There was no sign of heavy bird roosting or nesting, which would be a possible source of biting ectoparasites. Other than the Australian pine, notable vegetation present included Christmasberry (Schinus terebinthifolius), koa haole (Leucaena leucocephala), and Chinese banyan (Ficus microcarpa). A survey of the vegetation uncovered no notable insects, and no damage to the leaves of the Chinese banyans, which is typical of thrip infestation, was noted.

|

|

| Figure 3. Superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial dermatitis (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10) with lymphocytic predominance (B)(H&E, original magnification ×40). | |

After completion of a resource-intensive investigation that included site survey, literature review, detailed patient history including thrips-associated skin manifestations, and thorough consultation with local dermatologists and entomologists, the findings seemingly pointed to thrips as the most likely etiology of the eruption seen in our patients and a diagnosis of Thysanoptera dermatitis was made.

Comment

Thrips are small winged insects in the order Thysanoptera, which comprises more than 5000 identified species ranging in size from 0.5 to 15 mm, though most are approximately 1 mm.1 The insects typically are phytophagous (feeding on plants) and are attracted to humidity and seemingly the sweat of animals and humans.2 Although largely a phytophagous organism, a few published cases of thrips exposure reported papular skin eruptions known as Thysanoptera dermatitis.3-8 Several species of thrips across the globe have been associated with incidental attacks on humans to include “Heliothrips indicus Bagnall, a cotton pest of the Sudan; Thrips imagines Bagnall, reported in Australia; Limothrips cerealium (Haliday), in Germany; Gynaitkothrips uzeli Zimmerman, in Algeria; and other species.”7 In Hawaii, Gynaikothrips ficorum (Cuban laurel thrips) is a common pest of the Chinese banyan tree (F microcarpa) tree.9

A case series reported by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in the late 1960s of military personnel stationed in Oahu described exposure to similar environmental conditions with resultant lesions that were nearly identical to those seen in our patients. The final conclusion of the investigation was that Cuban laurel thrips were the likely etiology, though mites also were considered.5 In a subsequent commentary in 1968, Waisman10 reported similar eruptions in hospitalized patients with further comment regarding the nocturnal occurrence of the bites. Additionally, the eruptions were reported to be short lasting and devoid of discomfort, similar to our patient population.10

Following suit, Aeling6 published a case series in 1974 depicting several service members who presented with symptoms that were nearly identical to the symptoms experienced by our patients as well as those of Goldstein and Skipworth.5 The investigator coined the term hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii to describe the findings and further reported that Hawaiian dermatologists were familiar with the symptoms and clinical presentation of the disease. Patients in this outbreak had observed small flying insects, similar to the reports from our patients, and postulated that the symptoms occurred secondary to insect bites.6

Since the report by Goldstein and Skipworth5 in 1968, the majority of the literature regarding Thysanoptera dermatitis has largely been in case reports. In 1987, Fishman7 reported the case of a 43-year-old woman who presented with a palm-sized area of grouped red puncta on the lateral neck with the subsequent entrapment and identification of a flower thrips from the patient’s clothing. In 2005, Leigheb et al2 reported the case of a 30-year-old man with an erythematous papular cutaneous eruption on the anterior chest. In this case, the causative etiology was unequivocally confirmed upon identification of the presence of thrips on biopsy.2 In 2006, Guarneri et al1 reported the case of a 59-year-old farmer who had tentatively been diagnosed with delusional parasitosis until persistent presentation to a dermatologist for evaluation enabled the capture and identification of grain thrips. More recently, another case of likely Thysanoptera dermatitis was published in 2012 after a man presented with a slide-mounted thrip from his skin for evaluation as to a potential cause of a recurrent rash he had been experiencing.11 In all of these cases, it was fortunate that a specific organism could be identified for 2 reasons: (1) members of the order Thysanoptera have a biological cycle of only 11 to 36 days, and (2) thrips may go virtually unnoticed by humans, as they are often difficult to see due to their small size.2,12 Perhaps the most extensive report, however, comes from Childers et al8 in a descriptive case series published in 2005. In this report, the investigators provided a thorough detailing of multiple encounters dating back to 1883 through which patients were inadvertently exposed to various species of thrips and subsequently presented with arthropod bites.

Conclusion

The rapid and clustered manner of patient presentation in this case series makes it unique and highlights the need for further consideration of Thysanoptera dermatitis as a potential etiology for an outbreak of a papular eruption. Further reporting may help to better contextualize the true epidemiology of the condition and subsequently may trigger its greater inclusion in the differential diagnosis for a pruritic papular eruption.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our appreciation to Amy Spizuoco, DO (New York, New York), for her assistance with the initial diagnosis; Steve Montgomery, PhD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for his assistance with further entomological discussion of potential etiologies; and John R. Gilstad, MD (Honolulu, Hawaii), for contributing his thoughts on the differential diagnosis of the presenting symptoms.

1. Guarneri F, Guarneri C, Mento G, et al. Pseudo‐delusory syndrome caused by Limothrips cerealium. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:197-199.

2. Leigheb G, Tiberio R, Filosa G, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:722-724.

3. Williams CB. A blood sucking thrips. The Entomologist. 1921;54:164.

4. Bailey SF. Thrips attacking man. Can Entomol. 1936;68:95-98.

5. Goldstein N, Skipworth GB. Papular eruption secondary to thrips bites. JAMA. 1968;203:53-55.

6. Aeling JL. Hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii. Cutis. 1974;14:541-544.

7. Fishman HC. Thrips. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:993.

8. Childers CC, Beshear RJ, Frantz G, et al. A review of thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986-1997. Florida Entomologist. 2005;88:447-451.

9. Funasaki GY. Studies on the life cycle and propagation technique of Montandoniola moraguesi (Puton)(Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Proc Hawaii Entomol Soc. 1966;XIX.2:209-211.

10. Waisman M. Thrips bites dermatitis. JAMA. 1968;204:82.

11. Martin J, Richmond A, Davis BM, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis presenting as folie à deux. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:864-865.

12. Cooper RG. Dermatitis & conjunctivitis in workers on an ostrich farm following thrips infestation. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:588-589.

1. Guarneri F, Guarneri C, Mento G, et al. Pseudo‐delusory syndrome caused by Limothrips cerealium. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:197-199.

2. Leigheb G, Tiberio R, Filosa G, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:722-724.

3. Williams CB. A blood sucking thrips. The Entomologist. 1921;54:164.

4. Bailey SF. Thrips attacking man. Can Entomol. 1936;68:95-98.

5. Goldstein N, Skipworth GB. Papular eruption secondary to thrips bites. JAMA. 1968;203:53-55.

6. Aeling JL. Hypoanesthetic halos in Hawaii. Cutis. 1974;14:541-544.

7. Fishman HC. Thrips. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:993.

8. Childers CC, Beshear RJ, Frantz G, et al. A review of thrips species biting man including records in Florida and Georgia between 1986-1997. Florida Entomologist. 2005;88:447-451.

9. Funasaki GY. Studies on the life cycle and propagation technique of Montandoniola moraguesi (Puton)(Heteroptera: Anthocoridae). Proc Hawaii Entomol Soc. 1966;XIX.2:209-211.

10. Waisman M. Thrips bites dermatitis. JAMA. 1968;204:82.

11. Martin J, Richmond A, Davis BM, et al. Thysanoptera dermatitis presenting as folie à deux. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:864-865.

12. Cooper RG. Dermatitis & conjunctivitis in workers on an ostrich farm following thrips infestation. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:588-589.

Practice Points

- Thysanoptera dermatitis presents as a diffuse cutaneous eruption consisting of scattered pruritic papules to exposed skin surfaces.

- The importance of considering the environmental component of a cutaneous eruption via a thorough understanding of local flora and fauna cannot be underestimated.

- The role of a dermatologist in the rapid identification of a cutaneous eruption in the setting of an acute cluster outbreak is of utmost importance to assist with eliminating infectious and environmental public health threats from the differential diagnosis.

Trabectedin found to benefit patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma

SAN DIEGO – Among patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma who underwent prior chemotherapy, treatment with trabectedin resulted in superior disease control, with significantly longer progression-free survival, compared with dacarbazine, a phase III trial showed.

“Trabectedin is an important new treatment option for patients with advanced uterine LMS after anthracycline-containing treatment,” lead study author Dr. Martee L. Hensley said at annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

Trabectedin, which is marketed by Janssen Products and is also known as ET743, has a novel mechanism of action that “distorts DNA structure resulting in the initiation of DNA repair,” explained Dr. Hensley, a surgical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. “At the same time it binds and inhibits repair mechanisms, thereby activating apoptosis. In addition, trabectedin inhibits transcriptional activation and can modify the tumor microenvironment.”

ET743-SAR-3007 was the largest randomized, phase III study in soft tissue sarcoma. It found that trabectedin demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS), compared with dacarbazine (4.2 months vs. 1.5 months; hazard ratio = .55; P less than .001). The results led to FDA approval of trabectedin for the treatment of patients with leiomyosarcoma (LMS) or liposarcoma (LPS), after prior anthracycline therapy. In addition, a previously reported subgroup analysis demonstrated equivalent PFS benefit in patients with either LMS (HR = .56) or LPS HR = .55). However, the majority of that study population (73%) had LMS, and most of those (40%) were uterine LMS. The purpose of the current analysis was the subgroup of patients 232 with uterine LMS who were enrolled in ET743-SAR-3007, which was conducted in 90 sites on four different countries.

Dr. Hensley reported that of the 232 women, 144 were randomized to receive a 24-hour infusion of trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every three weeks and 88 to receive a 20- to-120-minute infusion of dacarbazine 1 g/m2 every three weeks. “It’s interesting to note that the vast majority of these patients are enrolling in this study for either a third or fourth-line therapy, and nearly 20% are enrolling for fifth-line therapy for metastatic sarcoma,” she said. The primary endpoint was overall survival, while secondary endpoints were progression-free survival, overall response rate, duration of response, safety, and patient-reported outcomes.

The median number of treatment cycles was four in the trabectedin arm, compared with two in the dacarbazine arm. Nearly 40% of patients in the trabectedin arm received at least six cycles of therapy, compared with 19% in the dacarbazine arm. “There is probably a lack of cumulative toxicity that allows patients that have good disease control to remain trabectedin for a prolonged period of time,” Dr. Hensley said.

The researchers found that in patients with uterine LMS, trabectedin significantly improved progression-free survival, compared with those who received dacarbazine (4.01 months vs. 1.54 months, respectively; HR: .57; P = .0012). “Because progression-free survival can be a soft endpoint, the study was designed to collect radiographic images for central review,” Dr. Hensley said. “That was achieved in 60% of the study population in order to corroborate the PFS endpoint.”

The overall survival benefit observed with trabectedin treatment did not differ from that of dacarbazine (a median of 13.4 months vs. 12.9 months, respectively; HR = .89; P = .5107). Dr. Hensley characterized the overall response rate of both agents as “modest” (11% in the trabectedin arm, vs. 9% in the dacarbazine arm; P = .816).

Median time to response was similar between both arms (about three months) as was median duration of response (about four months for the dacarbazine arm vs. six months for the trabectedin arm). However, she pointed out that those two comparisons were based on a total of 22 patients: seven in the dacarbazine arm and 15 in the trabectedin arm.

Grade 3-4 adverse events such as increased ALT and neutropenia were more common in the trabectedin arm, compared with the dacarbazine arm (69% vs. 42%). There were two treatment-related deaths within 30 days of last dose in the trabectedin arm (1.4%) and no deaths on the dacarbazine arm.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma who underwent prior chemotherapy, treatment with trabectedin resulted in superior disease control, with significantly longer progression-free survival, compared with dacarbazine, a phase III trial showed.

“Trabectedin is an important new treatment option for patients with advanced uterine LMS after anthracycline-containing treatment,” lead study author Dr. Martee L. Hensley said at annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

Trabectedin, which is marketed by Janssen Products and is also known as ET743, has a novel mechanism of action that “distorts DNA structure resulting in the initiation of DNA repair,” explained Dr. Hensley, a surgical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. “At the same time it binds and inhibits repair mechanisms, thereby activating apoptosis. In addition, trabectedin inhibits transcriptional activation and can modify the tumor microenvironment.”

ET743-SAR-3007 was the largest randomized, phase III study in soft tissue sarcoma. It found that trabectedin demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS), compared with dacarbazine (4.2 months vs. 1.5 months; hazard ratio = .55; P less than .001). The results led to FDA approval of trabectedin for the treatment of patients with leiomyosarcoma (LMS) or liposarcoma (LPS), after prior anthracycline therapy. In addition, a previously reported subgroup analysis demonstrated equivalent PFS benefit in patients with either LMS (HR = .56) or LPS HR = .55). However, the majority of that study population (73%) had LMS, and most of those (40%) were uterine LMS. The purpose of the current analysis was the subgroup of patients 232 with uterine LMS who were enrolled in ET743-SAR-3007, which was conducted in 90 sites on four different countries.

Dr. Hensley reported that of the 232 women, 144 were randomized to receive a 24-hour infusion of trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every three weeks and 88 to receive a 20- to-120-minute infusion of dacarbazine 1 g/m2 every three weeks. “It’s interesting to note that the vast majority of these patients are enrolling in this study for either a third or fourth-line therapy, and nearly 20% are enrolling for fifth-line therapy for metastatic sarcoma,” she said. The primary endpoint was overall survival, while secondary endpoints were progression-free survival, overall response rate, duration of response, safety, and patient-reported outcomes.

The median number of treatment cycles was four in the trabectedin arm, compared with two in the dacarbazine arm. Nearly 40% of patients in the trabectedin arm received at least six cycles of therapy, compared with 19% in the dacarbazine arm. “There is probably a lack of cumulative toxicity that allows patients that have good disease control to remain trabectedin for a prolonged period of time,” Dr. Hensley said.

The researchers found that in patients with uterine LMS, trabectedin significantly improved progression-free survival, compared with those who received dacarbazine (4.01 months vs. 1.54 months, respectively; HR: .57; P = .0012). “Because progression-free survival can be a soft endpoint, the study was designed to collect radiographic images for central review,” Dr. Hensley said. “That was achieved in 60% of the study population in order to corroborate the PFS endpoint.”

The overall survival benefit observed with trabectedin treatment did not differ from that of dacarbazine (a median of 13.4 months vs. 12.9 months, respectively; HR = .89; P = .5107). Dr. Hensley characterized the overall response rate of both agents as “modest” (11% in the trabectedin arm, vs. 9% in the dacarbazine arm; P = .816).

Median time to response was similar between both arms (about three months) as was median duration of response (about four months for the dacarbazine arm vs. six months for the trabectedin arm). However, she pointed out that those two comparisons were based on a total of 22 patients: seven in the dacarbazine arm and 15 in the trabectedin arm.

Grade 3-4 adverse events such as increased ALT and neutropenia were more common in the trabectedin arm, compared with the dacarbazine arm (69% vs. 42%). There were two treatment-related deaths within 30 days of last dose in the trabectedin arm (1.4%) and no deaths on the dacarbazine arm.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma who underwent prior chemotherapy, treatment with trabectedin resulted in superior disease control, with significantly longer progression-free survival, compared with dacarbazine, a phase III trial showed.

“Trabectedin is an important new treatment option for patients with advanced uterine LMS after anthracycline-containing treatment,” lead study author Dr. Martee L. Hensley said at annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology.

Trabectedin, which is marketed by Janssen Products and is also known as ET743, has a novel mechanism of action that “distorts DNA structure resulting in the initiation of DNA repair,” explained Dr. Hensley, a surgical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York. “At the same time it binds and inhibits repair mechanisms, thereby activating apoptosis. In addition, trabectedin inhibits transcriptional activation and can modify the tumor microenvironment.”

ET743-SAR-3007 was the largest randomized, phase III study in soft tissue sarcoma. It found that trabectedin demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival (PFS), compared with dacarbazine (4.2 months vs. 1.5 months; hazard ratio = .55; P less than .001). The results led to FDA approval of trabectedin for the treatment of patients with leiomyosarcoma (LMS) or liposarcoma (LPS), after prior anthracycline therapy. In addition, a previously reported subgroup analysis demonstrated equivalent PFS benefit in patients with either LMS (HR = .56) or LPS HR = .55). However, the majority of that study population (73%) had LMS, and most of those (40%) were uterine LMS. The purpose of the current analysis was the subgroup of patients 232 with uterine LMS who were enrolled in ET743-SAR-3007, which was conducted in 90 sites on four different countries.

Dr. Hensley reported that of the 232 women, 144 were randomized to receive a 24-hour infusion of trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every three weeks and 88 to receive a 20- to-120-minute infusion of dacarbazine 1 g/m2 every three weeks. “It’s interesting to note that the vast majority of these patients are enrolling in this study for either a third or fourth-line therapy, and nearly 20% are enrolling for fifth-line therapy for metastatic sarcoma,” she said. The primary endpoint was overall survival, while secondary endpoints were progression-free survival, overall response rate, duration of response, safety, and patient-reported outcomes.

The median number of treatment cycles was four in the trabectedin arm, compared with two in the dacarbazine arm. Nearly 40% of patients in the trabectedin arm received at least six cycles of therapy, compared with 19% in the dacarbazine arm. “There is probably a lack of cumulative toxicity that allows patients that have good disease control to remain trabectedin for a prolonged period of time,” Dr. Hensley said.

The researchers found that in patients with uterine LMS, trabectedin significantly improved progression-free survival, compared with those who received dacarbazine (4.01 months vs. 1.54 months, respectively; HR: .57; P = .0012). “Because progression-free survival can be a soft endpoint, the study was designed to collect radiographic images for central review,” Dr. Hensley said. “That was achieved in 60% of the study population in order to corroborate the PFS endpoint.”

The overall survival benefit observed with trabectedin treatment did not differ from that of dacarbazine (a median of 13.4 months vs. 12.9 months, respectively; HR = .89; P = .5107). Dr. Hensley characterized the overall response rate of both agents as “modest” (11% in the trabectedin arm, vs. 9% in the dacarbazine arm; P = .816).

Median time to response was similar between both arms (about three months) as was median duration of response (about four months for the dacarbazine arm vs. six months for the trabectedin arm). However, she pointed out that those two comparisons were based on a total of 22 patients: seven in the dacarbazine arm and 15 in the trabectedin arm.

Grade 3-4 adverse events such as increased ALT and neutropenia were more common in the trabectedin arm, compared with the dacarbazine arm (69% vs. 42%). There were two treatment-related deaths within 30 days of last dose in the trabectedin arm (1.4%) and no deaths on the dacarbazine arm.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING ON WOMEN’S CANCER

Key clinical point: Trabectedin is a new treatment option for patients with advanced uterine leiomyosarcoma after anthracycline-containing treatment.

Major finding: In patients with uterine LMS, trabectedin significantly improved progression-free survival, compared with those who received dacarbazine (4.01 months vs. 1.54 months, respectively; HR: .57; P = .0012).

Data source: Results from 144 women who were randomized to receive a 24-hour infusion of trabectedin 1.5 mg/m2 every three weeks, and 88 who received a 20- to-120-minute infusion of dacarbazine 1 g/m2 every three weeks.

Disclosures: Dr. Hensley reported having received consulting and research funding from Janssen Research and Development, LLC. She also disclosed that her spouse is employed by Sanofi.

New SHM Members – April 2016

K. Terrell, MD, Alabama

W. Burt, Arkansas

O. Shill, Arizona

S. Akhtar, MD, California

G. Andonian, California

E. Blecharczy, MD, FAAP, California

P. Febres, MD, California

C. Green, MD, California

C. Ha, California

R. Haile-Meskale, California

M. Hakimipour, MD, California

R. Hanemann, California

S. Khachoyan, California

M. Mahig, MD, California

R. Matson, California

K. McBride, California

M. Miles, BSN, MHA, MS, RN, California

P. Morales, California

J. Tannous, California

N. Aryee Tetteh, California

G. Thompson, California

I. Thomlinson, California

R. Valand, MPH, California

G. L. Wergowske, MD, California

S. Clyne, Colorado

J. Valentin, MD, FACP, Colorado

A. Noonan, APRN, Connecticut

J. Samuel, MD, Connecticut

D. Schillinger, Florida

N. Fobi-Nunga, Georgia

C. Troutman, RN, Georgia

I. Molano, MD, Iowa

Z. Abbas, Illinois

J. Burton, Illinois

F. Chowdhury, Illinois

S. Patel, MD, Illinois

M. Knutson, DO, Indiana

E. Wanas, MD, Indiana

B. E. Bradley, MBChB, Kentucky

T. Jetha, Louisiana

N. Melendez-Rios, MD, Massachusetts

A. Miskiv, Massachusetts

K. Nakashima, MD, Massachusetts

P. Pilegi, ACNP, Massachusetts

E. Shannon, Massachusetts

N. Singh, Massachusetts

R. Thatte, MD, Massachusetts

J. Viola, Massachusetts

J. Bie, CRNP, Maryland

C. Lafeer, Maryland

J. Mignano, Maryland

H. Jarawan, Maine

D. Stein, DO, Maine

S. Franso, MD, Michigan

T. LaBonte, MD, Michigan

D. Malaka, MD, MPH, Michigan

A. Miller, Minnesota

M. Usher, MD, PhD, Minnesota

M. Brinkmeier, MD, Missouri

S. Hassan, Missouri

R. Pitts, MD, Missouri

J. Sorg, MD, Missouri

M. Vaughan, Mississippi

C. Brown, ACMPE, North Carolina

D. Ghiassi, North Carolina

J. Hoffman, North Carolina

C. Norman, MS, PA-C, North Carolina

K. McDonald, MD, Nebraska

Y. Melnikova, MD, New Hampshire

J. Adigun, MD, New Jersey

S. Bhatt, MD, New Jersey

K. Bhavsar, New Jersey

S. Griggs, ANP, New York

G. Jabbour, New York

K. Kang, New York

P. Kayi, MD, New York

C. Lopez, MD, MPH, New York

O. Olafisoye, MD, New York

J. K. Salvani, MD, New York

M. Shinwa, New York

P. Wander, New York

S. Boyle, Ohio

S. Goates, Ohio

A. Hochhausler, MD, Ohio

V. Jayanti, Ohio

D. Kassay, CNP, Ohio

K. Welch, Ohio

J. Retson, CCFP, Ontario

V. Cheng, Pennsylvania

G. Chong, Pennsylvania

J. Hart, MD, Pennsylvania

M. M. Scoulos-Hanson, Pennsylvania

M. Shelkin, DO, Pennsylvania

S. Freeman, Rhode Island

G. Hussain, Rhode Island

R. Ulrich, PA-C, South Carolina

K. Inama, APRN-BC, South Dakota

S. Bray, Saskatchewan

D. E. Adams III, MD, Tennessee

I. Ellis, MD, Tennessee

C. Parrish, Tennessee

K. San, MC, USAR, Tennessee

A. Ahmed, MD, Texas

Z. Conrad, Texas

A. Iqbal, MD, Texas

J. Jamullamudi, MD, Texas

W. Mallot, Texas

C. Okoro, MD, Texas

C. Shy, Texas

P. Vankawala, Texas

L. Walker, Texas

D. Glodowski, MD, Utah

K. Brunson, NP, Virginia

E. Caldwell, Virginia

M. H. Chouindard, MD, Virginia

S. Edwards, MD, Virginia

S. Feldmann, Virginia

D. Kadariya, MBBS, MD, Virginia

J. Lachar, MBBS, MD, Virginia

B. Queen, MD, Virginia

A. M. Shamas, MD, Virginia

A. Wong, MD, Virginia

T. Chang, Washington

E. Gorbacheva, MD, Washington

Z. Li, PA-C, Washington

I. Murray, PA-C, Washington

M. Schaffer, MD, Washington

M. Stolzberg, Washington

K. Miller, MD, Wisconsin

C. Ranheim, MD, Wisconsin

A. Vincent, Wisconsin

J. Yi, DO, West Virginia

K. Han

S. Pannick

Y. Tan

K. Terrell, MD, Alabama

W. Burt, Arkansas

O. Shill, Arizona

S. Akhtar, MD, California

G. Andonian, California

E. Blecharczy, MD, FAAP, California

P. Febres, MD, California

C. Green, MD, California

C. Ha, California

R. Haile-Meskale, California

M. Hakimipour, MD, California

R. Hanemann, California

S. Khachoyan, California

M. Mahig, MD, California

R. Matson, California

K. McBride, California

M. Miles, BSN, MHA, MS, RN, California

P. Morales, California

J. Tannous, California

N. Aryee Tetteh, California

G. Thompson, California

I. Thomlinson, California

R. Valand, MPH, California

G. L. Wergowske, MD, California

S. Clyne, Colorado

J. Valentin, MD, FACP, Colorado

A. Noonan, APRN, Connecticut

J. Samuel, MD, Connecticut

D. Schillinger, Florida

N. Fobi-Nunga, Georgia

C. Troutman, RN, Georgia

I. Molano, MD, Iowa

Z. Abbas, Illinois

J. Burton, Illinois

F. Chowdhury, Illinois

S. Patel, MD, Illinois

M. Knutson, DO, Indiana

E. Wanas, MD, Indiana

B. E. Bradley, MBChB, Kentucky

T. Jetha, Louisiana

N. Melendez-Rios, MD, Massachusetts

A. Miskiv, Massachusetts

K. Nakashima, MD, Massachusetts

P. Pilegi, ACNP, Massachusetts

E. Shannon, Massachusetts

N. Singh, Massachusetts

R. Thatte, MD, Massachusetts

J. Viola, Massachusetts

J. Bie, CRNP, Maryland

C. Lafeer, Maryland

J. Mignano, Maryland

H. Jarawan, Maine

D. Stein, DO, Maine

S. Franso, MD, Michigan

T. LaBonte, MD, Michigan

D. Malaka, MD, MPH, Michigan

A. Miller, Minnesota

M. Usher, MD, PhD, Minnesota

M. Brinkmeier, MD, Missouri

S. Hassan, Missouri

R. Pitts, MD, Missouri

J. Sorg, MD, Missouri

M. Vaughan, Mississippi

C. Brown, ACMPE, North Carolina

D. Ghiassi, North Carolina

J. Hoffman, North Carolina

C. Norman, MS, PA-C, North Carolina

K. McDonald, MD, Nebraska

Y. Melnikova, MD, New Hampshire

J. Adigun, MD, New Jersey

S. Bhatt, MD, New Jersey

K. Bhavsar, New Jersey

S. Griggs, ANP, New York

G. Jabbour, New York

K. Kang, New York

P. Kayi, MD, New York

C. Lopez, MD, MPH, New York

O. Olafisoye, MD, New York

J. K. Salvani, MD, New York

M. Shinwa, New York

P. Wander, New York

S. Boyle, Ohio

S. Goates, Ohio

A. Hochhausler, MD, Ohio

V. Jayanti, Ohio

D. Kassay, CNP, Ohio

K. Welch, Ohio

J. Retson, CCFP, Ontario

V. Cheng, Pennsylvania

G. Chong, Pennsylvania

J. Hart, MD, Pennsylvania

M. M. Scoulos-Hanson, Pennsylvania

M. Shelkin, DO, Pennsylvania

S. Freeman, Rhode Island

G. Hussain, Rhode Island

R. Ulrich, PA-C, South Carolina

K. Inama, APRN-BC, South Dakota

S. Bray, Saskatchewan

D. E. Adams III, MD, Tennessee

I. Ellis, MD, Tennessee

C. Parrish, Tennessee

K. San, MC, USAR, Tennessee

A. Ahmed, MD, Texas

Z. Conrad, Texas

A. Iqbal, MD, Texas

J. Jamullamudi, MD, Texas

W. Mallot, Texas

C. Okoro, MD, Texas

C. Shy, Texas

P. Vankawala, Texas

L. Walker, Texas

D. Glodowski, MD, Utah

K. Brunson, NP, Virginia

E. Caldwell, Virginia

M. H. Chouindard, MD, Virginia

S. Edwards, MD, Virginia

S. Feldmann, Virginia

D. Kadariya, MBBS, MD, Virginia

J. Lachar, MBBS, MD, Virginia

B. Queen, MD, Virginia

A. M. Shamas, MD, Virginia

A. Wong, MD, Virginia

T. Chang, Washington

E. Gorbacheva, MD, Washington

Z. Li, PA-C, Washington

I. Murray, PA-C, Washington

M. Schaffer, MD, Washington

M. Stolzberg, Washington

K. Miller, MD, Wisconsin

C. Ranheim, MD, Wisconsin

A. Vincent, Wisconsin

J. Yi, DO, West Virginia

K. Han

S. Pannick

Y. Tan

K. Terrell, MD, Alabama

W. Burt, Arkansas

O. Shill, Arizona

S. Akhtar, MD, California

G. Andonian, California

E. Blecharczy, MD, FAAP, California

P. Febres, MD, California

C. Green, MD, California

C. Ha, California

R. Haile-Meskale, California

M. Hakimipour, MD, California

R. Hanemann, California

S. Khachoyan, California

M. Mahig, MD, California

R. Matson, California

K. McBride, California

M. Miles, BSN, MHA, MS, RN, California

P. Morales, California

J. Tannous, California

N. Aryee Tetteh, California

G. Thompson, California

I. Thomlinson, California

R. Valand, MPH, California

G. L. Wergowske, MD, California

S. Clyne, Colorado

J. Valentin, MD, FACP, Colorado

A. Noonan, APRN, Connecticut

J. Samuel, MD, Connecticut

D. Schillinger, Florida

N. Fobi-Nunga, Georgia

C. Troutman, RN, Georgia

I. Molano, MD, Iowa

Z. Abbas, Illinois

J. Burton, Illinois

F. Chowdhury, Illinois

S. Patel, MD, Illinois

M. Knutson, DO, Indiana

E. Wanas, MD, Indiana

B. E. Bradley, MBChB, Kentucky

T. Jetha, Louisiana

N. Melendez-Rios, MD, Massachusetts

A. Miskiv, Massachusetts

K. Nakashima, MD, Massachusetts

P. Pilegi, ACNP, Massachusetts

E. Shannon, Massachusetts

N. Singh, Massachusetts

R. Thatte, MD, Massachusetts

J. Viola, Massachusetts

J. Bie, CRNP, Maryland

C. Lafeer, Maryland

J. Mignano, Maryland

H. Jarawan, Maine

D. Stein, DO, Maine

S. Franso, MD, Michigan

T. LaBonte, MD, Michigan

D. Malaka, MD, MPH, Michigan

A. Miller, Minnesota

M. Usher, MD, PhD, Minnesota

M. Brinkmeier, MD, Missouri

S. Hassan, Missouri

R. Pitts, MD, Missouri

J. Sorg, MD, Missouri

M. Vaughan, Mississippi

C. Brown, ACMPE, North Carolina

D. Ghiassi, North Carolina

J. Hoffman, North Carolina

C. Norman, MS, PA-C, North Carolina

K. McDonald, MD, Nebraska

Y. Melnikova, MD, New Hampshire

J. Adigun, MD, New Jersey

S. Bhatt, MD, New Jersey

K. Bhavsar, New Jersey

S. Griggs, ANP, New York

G. Jabbour, New York

K. Kang, New York

P. Kayi, MD, New York

C. Lopez, MD, MPH, New York

O. Olafisoye, MD, New York

J. K. Salvani, MD, New York

M. Shinwa, New York

P. Wander, New York

S. Boyle, Ohio

S. Goates, Ohio

A. Hochhausler, MD, Ohio

V. Jayanti, Ohio

D. Kassay, CNP, Ohio

K. Welch, Ohio

J. Retson, CCFP, Ontario

V. Cheng, Pennsylvania

G. Chong, Pennsylvania

J. Hart, MD, Pennsylvania

M. M. Scoulos-Hanson, Pennsylvania

M. Shelkin, DO, Pennsylvania

S. Freeman, Rhode Island

G. Hussain, Rhode Island

R. Ulrich, PA-C, South Carolina

K. Inama, APRN-BC, South Dakota

S. Bray, Saskatchewan

D. E. Adams III, MD, Tennessee

I. Ellis, MD, Tennessee

C. Parrish, Tennessee

K. San, MC, USAR, Tennessee

A. Ahmed, MD, Texas

Z. Conrad, Texas

A. Iqbal, MD, Texas

J. Jamullamudi, MD, Texas

W. Mallot, Texas

C. Okoro, MD, Texas

C. Shy, Texas

P. Vankawala, Texas

L. Walker, Texas

D. Glodowski, MD, Utah

K. Brunson, NP, Virginia

E. Caldwell, Virginia

M. H. Chouindard, MD, Virginia

S. Edwards, MD, Virginia

S. Feldmann, Virginia

D. Kadariya, MBBS, MD, Virginia

J. Lachar, MBBS, MD, Virginia

B. Queen, MD, Virginia

A. M. Shamas, MD, Virginia

A. Wong, MD, Virginia

T. Chang, Washington

E. Gorbacheva, MD, Washington

Z. Li, PA-C, Washington

I. Murray, PA-C, Washington

M. Schaffer, MD, Washington

M. Stolzberg, Washington

K. Miller, MD, Wisconsin

C. Ranheim, MD, Wisconsin

A. Vincent, Wisconsin

J. Yi, DO, West Virginia

K. Han

S. Pannick

Y. Tan

FDA authorizes new test for Zika virus

Photo by Graham Colm

In response to a request from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay, a tool that can be used to detect Zika virus.

The assay allows doctors to tell if an individual is infected with chikungunya, dengue, or Zika virus using a single test, instead of having to perform 3 separate tests to identify the infection.

The Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay can be used to detect virus RNA in serum, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and amniotic fluid specimens.

The CDC hopes this EUA will allow the agency to more rapidly perform testing to detect acute Zika virus infection.

An EUA allows the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The CDC said it will begin distributing the Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay during the next 2 weeks to qualified laboratories in the Laboratory Response Network, an integrated network of domestic and international laboratories that respond to public health emergencies.

The test will not be available in US hospitals or other primary care settings.

Last month, the FDA issued an EUA for a different test used to detect the Zika virus, the Zika IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA).

This test was distributed to qualified laboratories in the Laboratory Response Network but was not made available in US hospitals or other primary care settings. ![]()

Photo by Graham Colm

In response to a request from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay, a tool that can be used to detect Zika virus.

The assay allows doctors to tell if an individual is infected with chikungunya, dengue, or Zika virus using a single test, instead of having to perform 3 separate tests to identify the infection.

The Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay can be used to detect virus RNA in serum, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and amniotic fluid specimens.

The CDC hopes this EUA will allow the agency to more rapidly perform testing to detect acute Zika virus infection.

An EUA allows the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The CDC said it will begin distributing the Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay during the next 2 weeks to qualified laboratories in the Laboratory Response Network, an integrated network of domestic and international laboratories that respond to public health emergencies.

The test will not be available in US hospitals or other primary care settings.

Last month, the FDA issued an EUA for a different test used to detect the Zika virus, the Zika IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA).

This test was distributed to qualified laboratories in the Laboratory Response Network but was not made available in US hospitals or other primary care settings. ![]()

Photo by Graham Colm

In response to a request from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for the Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay, a tool that can be used to detect Zika virus.

The assay allows doctors to tell if an individual is infected with chikungunya, dengue, or Zika virus using a single test, instead of having to perform 3 separate tests to identify the infection.

The Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay can be used to detect virus RNA in serum, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, and amniotic fluid specimens.

The CDC hopes this EUA will allow the agency to more rapidly perform testing to detect acute Zika virus infection.

An EUA allows the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The CDC said it will begin distributing the Trioplex Real-time RT-PCR Assay during the next 2 weeks to qualified laboratories in the Laboratory Response Network, an integrated network of domestic and international laboratories that respond to public health emergencies.

The test will not be available in US hospitals or other primary care settings.

Last month, the FDA issued an EUA for a different test used to detect the Zika virus, the Zika IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA).

This test was distributed to qualified laboratories in the Laboratory Response Network but was not made available in US hospitals or other primary care settings. ![]()

Decline in depression symptoms followed less than standard number of ketamine doses

Ketamine was 80% effective at decreasing depression symptoms, in a study of 100 depression patients who received less frequent and lower total doses of ketamine than are typically administered to treat depression.

Each study participant received no more than one ketamine intravenous infusion per week, with 4.3 having been the average total number of ketamine infusions received by a patient during the study. The frequency with which an infusion was received and the total number of infusions received by a patient were tailored to each patient’s responses to the therapy, according to the study’s author, Dr. Theodore Henderson. This study used a schedule of treatments for patients that differed from the established protocol for ketamine usage as an antidepressant, which is 3 times per week.

Prior to receiving the intravenous ketamine infusions, study participant’s Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR) score was 17.87 plus or minus 2.8 points, which corresponds to being severely depressed. The QIDS-SR score for each of the 80 study participants who responded to the therapy decreased by 10.8 plus or minus 3.5 points. The QIDS-SR of each of the 20 non-responders to the therapy changed by 0.8 plus or minus 1.8 points.

This study showed “clinical improvement with much fewer infusions for most patients. From a mechanistic standpoint, this can only be possible if ketamine is inducing increased BDNF [brain-derived neurotrophic factor] which leads to lasting changes in synapses, dendrites, and neuronal circuits,” Dr. Henderson said.

The study participants comprised 80 patients with recurrent unipolar depression and 20 patients with recurrent bipolar depression from Neuro-Luminance Ketamine Infusion Centers. Side effects experienced by the patients included elevated blood pressure, nausea, and dizziness, which was very common.

“Further controlled studies of the best clinical methods for ketamine infusion therapy are encouraged.” Dr. Henderson said.

Read the study in Neural Regeneration Research (doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.177708).

Ketamine was 80% effective at decreasing depression symptoms, in a study of 100 depression patients who received less frequent and lower total doses of ketamine than are typically administered to treat depression.

Each study participant received no more than one ketamine intravenous infusion per week, with 4.3 having been the average total number of ketamine infusions received by a patient during the study. The frequency with which an infusion was received and the total number of infusions received by a patient were tailored to each patient’s responses to the therapy, according to the study’s author, Dr. Theodore Henderson. This study used a schedule of treatments for patients that differed from the established protocol for ketamine usage as an antidepressant, which is 3 times per week.

Prior to receiving the intravenous ketamine infusions, study participant’s Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR) score was 17.87 plus or minus 2.8 points, which corresponds to being severely depressed. The QIDS-SR score for each of the 80 study participants who responded to the therapy decreased by 10.8 plus or minus 3.5 points. The QIDS-SR of each of the 20 non-responders to the therapy changed by 0.8 plus or minus 1.8 points.

This study showed “clinical improvement with much fewer infusions for most patients. From a mechanistic standpoint, this can only be possible if ketamine is inducing increased BDNF [brain-derived neurotrophic factor] which leads to lasting changes in synapses, dendrites, and neuronal circuits,” Dr. Henderson said.

The study participants comprised 80 patients with recurrent unipolar depression and 20 patients with recurrent bipolar depression from Neuro-Luminance Ketamine Infusion Centers. Side effects experienced by the patients included elevated blood pressure, nausea, and dizziness, which was very common.

“Further controlled studies of the best clinical methods for ketamine infusion therapy are encouraged.” Dr. Henderson said.

Read the study in Neural Regeneration Research (doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.177708).

Ketamine was 80% effective at decreasing depression symptoms, in a study of 100 depression patients who received less frequent and lower total doses of ketamine than are typically administered to treat depression.

Each study participant received no more than one ketamine intravenous infusion per week, with 4.3 having been the average total number of ketamine infusions received by a patient during the study. The frequency with which an infusion was received and the total number of infusions received by a patient were tailored to each patient’s responses to the therapy, according to the study’s author, Dr. Theodore Henderson. This study used a schedule of treatments for patients that differed from the established protocol for ketamine usage as an antidepressant, which is 3 times per week.

Prior to receiving the intravenous ketamine infusions, study participant’s Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Self Report (QIDS-SR) score was 17.87 plus or minus 2.8 points, which corresponds to being severely depressed. The QIDS-SR score for each of the 80 study participants who responded to the therapy decreased by 10.8 plus or minus 3.5 points. The QIDS-SR of each of the 20 non-responders to the therapy changed by 0.8 plus or minus 1.8 points.

This study showed “clinical improvement with much fewer infusions for most patients. From a mechanistic standpoint, this can only be possible if ketamine is inducing increased BDNF [brain-derived neurotrophic factor] which leads to lasting changes in synapses, dendrites, and neuronal circuits,” Dr. Henderson said.

The study participants comprised 80 patients with recurrent unipolar depression and 20 patients with recurrent bipolar depression from Neuro-Luminance Ketamine Infusion Centers. Side effects experienced by the patients included elevated blood pressure, nausea, and dizziness, which was very common.

“Further controlled studies of the best clinical methods for ketamine infusion therapy are encouraged.” Dr. Henderson said.

Read the study in Neural Regeneration Research (doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.177708).

FROM NEURAL REGENERATION RESEARCH

Getting a leg up on bone comorbidities in lupus

MAUI, HAWAII – Patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) really need to be placed on bone protection therapy as soon as they start on corticosteroids because their risks of steroid-related osteoporosis and osteonecrosis are so high, Dr. Dafna D. Gladman advised at the 2016 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

Investigators for new studies of large cohorts of SLE patients seen at the University of Toronto Lupus Clinic have examined numerous potential predictors of bone comorbidities, but only one independent risk factor emerged: a high cumulative dose of corticosteroids, said Dr. Gladman, professor of medicine and codirector of the clinic.

“The dose of steroids is certainly important. It’s relevant to patient management because we obviously want to try to minimize the amount of steroids that patients with lupus get,” the rheumatologist observed.

The Toronto experience underscores just how common and serious these bone comorbidities are.

Among 1,729 SLE patients in the clinic database, 13.6% developed symptomatic osteonecrosis as defined by clinical symptoms plus positive imaging findings. Overall, 86% were female. The mean age at diagnosis of SLE was 26.6 years, with a mean 8.2-year interval from SLE diagnosis to the first episode of osteonecrosis. The 235 patients with osteonecrosis had a collective 382 affected joints at the time of their first osteonecrosis diagnosis, with an additional 160 joints becoming osteonecrotic later.

Particularly noteworthy was the finding that fully 47% of patients had more than one site involved at the time of their first osteonecrotic event, according to Dr. Gladman.