User login

Pacify the Prostate, Pop Goes the Pituitary

INTRODUCTION

Excluding skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common malignancy affecting men in the United States, accounting for ~33% of VA cancer cases. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is considered standard of care in treating advanced prostate cancer. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare and morbid adverse event associated with GnRH agonist treatment. We describe a patient with advanced prostate cancer who developed pituitary apoplexy shortly after leuprolide therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 70-year-old African-American male was diagnosed with a T2aN1M1 stage IVB prostate cancer, Gleason 4+5, PSA 19.5. Four hours after his first leuprolide injection, he developed vomiting, diaphoresis, myalgia, and a severe frontal headache. Brain MRI revealed a 2.4 × 1.3 × 1.3cm pituitary mass, suspicious for an adenoma with hemorrhage. Labs noted low TSH, prolactin, LH, growth hormone, ACTH, cortisol, and testosterone, consistent with pituitary apoplexy. He was treated with steroids. Three weeks later, testosterone levels remained very low. He started abiraterone and prednisone without further leuprolide.

DISCUSSION

Prostate cancer is ubiquitous among VA patients, and ADT with GnRH agonist is vital in their care. These medications stimulate the pituitary to release LH and FSH resulting in a negative feedback loop, ultimately decreasing the levels of testosterone. Common side effects of GnRH agonists include hot flashes, diaphoresis, and sexual dysfunction. We present a patient who started leuprolide for prostate cancer. Symptoms including a severe headache led to an evaluation confirming pituitary apoplexy. Literature review reveals ~ 21 cases of pituitary apoplexy associated with GnRH agonist treatment for prostate cancer, and apoplexy can occur immediately to months later Undiagnosed pituitary adenomas are common among these patients. Treatment includes pituitary surgery or conservative management. Further prostate cancer treatment needs investigation, but we propose that GnRH modifying treatment can be withheld while testosterone levels remain low.

CONCLUSIONS

Prostate cancer is extremely common in the VA population, and treatment with leuprolide is standard. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare, but devastating complication of this treatment, and providers should be aware of the symptoms in order to intervene quickly. Further testosterone lowering treatment may be withheld if testosterone levels remain low.

INTRODUCTION

Excluding skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common malignancy affecting men in the United States, accounting for ~33% of VA cancer cases. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is considered standard of care in treating advanced prostate cancer. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare and morbid adverse event associated with GnRH agonist treatment. We describe a patient with advanced prostate cancer who developed pituitary apoplexy shortly after leuprolide therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 70-year-old African-American male was diagnosed with a T2aN1M1 stage IVB prostate cancer, Gleason 4+5, PSA 19.5. Four hours after his first leuprolide injection, he developed vomiting, diaphoresis, myalgia, and a severe frontal headache. Brain MRI revealed a 2.4 × 1.3 × 1.3cm pituitary mass, suspicious for an adenoma with hemorrhage. Labs noted low TSH, prolactin, LH, growth hormone, ACTH, cortisol, and testosterone, consistent with pituitary apoplexy. He was treated with steroids. Three weeks later, testosterone levels remained very low. He started abiraterone and prednisone without further leuprolide.

DISCUSSION

Prostate cancer is ubiquitous among VA patients, and ADT with GnRH agonist is vital in their care. These medications stimulate the pituitary to release LH and FSH resulting in a negative feedback loop, ultimately decreasing the levels of testosterone. Common side effects of GnRH agonists include hot flashes, diaphoresis, and sexual dysfunction. We present a patient who started leuprolide for prostate cancer. Symptoms including a severe headache led to an evaluation confirming pituitary apoplexy. Literature review reveals ~ 21 cases of pituitary apoplexy associated with GnRH agonist treatment for prostate cancer, and apoplexy can occur immediately to months later Undiagnosed pituitary adenomas are common among these patients. Treatment includes pituitary surgery or conservative management. Further prostate cancer treatment needs investigation, but we propose that GnRH modifying treatment can be withheld while testosterone levels remain low.

CONCLUSIONS

Prostate cancer is extremely common in the VA population, and treatment with leuprolide is standard. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare, but devastating complication of this treatment, and providers should be aware of the symptoms in order to intervene quickly. Further testosterone lowering treatment may be withheld if testosterone levels remain low.

INTRODUCTION

Excluding skin cancer, prostate cancer is the most common malignancy affecting men in the United States, accounting for ~33% of VA cancer cases. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is considered standard of care in treating advanced prostate cancer. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare and morbid adverse event associated with GnRH agonist treatment. We describe a patient with advanced prostate cancer who developed pituitary apoplexy shortly after leuprolide therapy.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 70-year-old African-American male was diagnosed with a T2aN1M1 stage IVB prostate cancer, Gleason 4+5, PSA 19.5. Four hours after his first leuprolide injection, he developed vomiting, diaphoresis, myalgia, and a severe frontal headache. Brain MRI revealed a 2.4 × 1.3 × 1.3cm pituitary mass, suspicious for an adenoma with hemorrhage. Labs noted low TSH, prolactin, LH, growth hormone, ACTH, cortisol, and testosterone, consistent with pituitary apoplexy. He was treated with steroids. Three weeks later, testosterone levels remained very low. He started abiraterone and prednisone without further leuprolide.

DISCUSSION

Prostate cancer is ubiquitous among VA patients, and ADT with GnRH agonist is vital in their care. These medications stimulate the pituitary to release LH and FSH resulting in a negative feedback loop, ultimately decreasing the levels of testosterone. Common side effects of GnRH agonists include hot flashes, diaphoresis, and sexual dysfunction. We present a patient who started leuprolide for prostate cancer. Symptoms including a severe headache led to an evaluation confirming pituitary apoplexy. Literature review reveals ~ 21 cases of pituitary apoplexy associated with GnRH agonist treatment for prostate cancer, and apoplexy can occur immediately to months later Undiagnosed pituitary adenomas are common among these patients. Treatment includes pituitary surgery or conservative management. Further prostate cancer treatment needs investigation, but we propose that GnRH modifying treatment can be withheld while testosterone levels remain low.

CONCLUSIONS

Prostate cancer is extremely common in the VA population, and treatment with leuprolide is standard. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare, but devastating complication of this treatment, and providers should be aware of the symptoms in order to intervene quickly. Further testosterone lowering treatment may be withheld if testosterone levels remain low.

Growing public perception that cannabis is safer than tobacco

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- While aggressive campaigns have led to a dramatic reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking and created safer smoke-free environments, regulation governing cannabis – which is associated with some health benefits but also many negative health outcomes – has been less restrictive.

- The study included a nationally representative sample of 5,035 mostly White U.S. adults, mean age 53.4 years, who completed three online surveys between 2017 and 2021 on the safety of tobacco and cannabis.

- In all three waves of the survey, respondents were asked to rate the safety of smoking one marijuana joint a day to smoking one cigarette a day, and of secondhand smoke from marijuana to that from tobacco.

- Respondents also expressed views on the safety of secondhand smoke exposure (of both marijuana and tobacco) on specific populations, including children, pregnant women, and adults (ratings were from “completely unsafe” to “completely safe”).

- Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, annual income, employment status, marital status, and state of residence.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a significant shift over time toward an increasingly favorable perception of cannabis; more respondents reported cannabis was “somewhat safer” or “much safer” than tobacco in 2021 than 2017 (44.3% vs. 36.7%; P < .001), and more believed secondhand smoke was somewhat or much safer for cannabis vs. tobacco in 2021 than in 2017 (40.2% vs. 35.1%; P < .001).

- More people endorsed the greater safety of secondhand smoke from cannabis vs. tobacco for children and pregnant women, and these perceptions remained similar over the study period.

- Younger and unmarried individuals were significantly more likely to move toward viewing smoking cannabis as safer than cigarettes, but legality of cannabis in respondents’ state of residence was not associated with change over time, suggesting the increasing perception of cannabis safety may be a national trend rather than a trend seen only in states with legalized cannabis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding changing views on tobacco and cannabis risk is important given that increases in social acceptance and decreases in risk perception may be directly associated with public health and policies,” the investigators write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Julia Chambers, MD, department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The generalizability of the study may be limited by nonresponse and loss to follow-up over time. The wording of survey questions may have introduced bias in respondents. Participants were asked about safety of smoking cannabis joints vs. tobacco cigarettes and not to compare safety of other forms of smoked and vaped cannabis, tobacco, and nicotine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. Dr. Chambers has no relevant conflicts of interest; author Katherine J. Hoggatt, PhD, MPH, department of medicine, UCSF, reported receiving grants from the Veterans Health Administration during the conduct of the study and grants from the National Institutes of Health, Rubin Family Foundation, and Veterans Health Administration outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- While aggressive campaigns have led to a dramatic reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking and created safer smoke-free environments, regulation governing cannabis – which is associated with some health benefits but also many negative health outcomes – has been less restrictive.

- The study included a nationally representative sample of 5,035 mostly White U.S. adults, mean age 53.4 years, who completed three online surveys between 2017 and 2021 on the safety of tobacco and cannabis.

- In all three waves of the survey, respondents were asked to rate the safety of smoking one marijuana joint a day to smoking one cigarette a day, and of secondhand smoke from marijuana to that from tobacco.

- Respondents also expressed views on the safety of secondhand smoke exposure (of both marijuana and tobacco) on specific populations, including children, pregnant women, and adults (ratings were from “completely unsafe” to “completely safe”).

- Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, annual income, employment status, marital status, and state of residence.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a significant shift over time toward an increasingly favorable perception of cannabis; more respondents reported cannabis was “somewhat safer” or “much safer” than tobacco in 2021 than 2017 (44.3% vs. 36.7%; P < .001), and more believed secondhand smoke was somewhat or much safer for cannabis vs. tobacco in 2021 than in 2017 (40.2% vs. 35.1%; P < .001).

- More people endorsed the greater safety of secondhand smoke from cannabis vs. tobacco for children and pregnant women, and these perceptions remained similar over the study period.

- Younger and unmarried individuals were significantly more likely to move toward viewing smoking cannabis as safer than cigarettes, but legality of cannabis in respondents’ state of residence was not associated with change over time, suggesting the increasing perception of cannabis safety may be a national trend rather than a trend seen only in states with legalized cannabis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding changing views on tobacco and cannabis risk is important given that increases in social acceptance and decreases in risk perception may be directly associated with public health and policies,” the investigators write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Julia Chambers, MD, department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The generalizability of the study may be limited by nonresponse and loss to follow-up over time. The wording of survey questions may have introduced bias in respondents. Participants were asked about safety of smoking cannabis joints vs. tobacco cigarettes and not to compare safety of other forms of smoked and vaped cannabis, tobacco, and nicotine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. Dr. Chambers has no relevant conflicts of interest; author Katherine J. Hoggatt, PhD, MPH, department of medicine, UCSF, reported receiving grants from the Veterans Health Administration during the conduct of the study and grants from the National Institutes of Health, Rubin Family Foundation, and Veterans Health Administration outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- While aggressive campaigns have led to a dramatic reduction in the prevalence of cigarette smoking and created safer smoke-free environments, regulation governing cannabis – which is associated with some health benefits but also many negative health outcomes – has been less restrictive.

- The study included a nationally representative sample of 5,035 mostly White U.S. adults, mean age 53.4 years, who completed three online surveys between 2017 and 2021 on the safety of tobacco and cannabis.

- In all three waves of the survey, respondents were asked to rate the safety of smoking one marijuana joint a day to smoking one cigarette a day, and of secondhand smoke from marijuana to that from tobacco.

- Respondents also expressed views on the safety of secondhand smoke exposure (of both marijuana and tobacco) on specific populations, including children, pregnant women, and adults (ratings were from “completely unsafe” to “completely safe”).

- Independent variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, annual income, employment status, marital status, and state of residence.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a significant shift over time toward an increasingly favorable perception of cannabis; more respondents reported cannabis was “somewhat safer” or “much safer” than tobacco in 2021 than 2017 (44.3% vs. 36.7%; P < .001), and more believed secondhand smoke was somewhat or much safer for cannabis vs. tobacco in 2021 than in 2017 (40.2% vs. 35.1%; P < .001).

- More people endorsed the greater safety of secondhand smoke from cannabis vs. tobacco for children and pregnant women, and these perceptions remained similar over the study period.

- Younger and unmarried individuals were significantly more likely to move toward viewing smoking cannabis as safer than cigarettes, but legality of cannabis in respondents’ state of residence was not associated with change over time, suggesting the increasing perception of cannabis safety may be a national trend rather than a trend seen only in states with legalized cannabis.

IN PRACTICE:

“Understanding changing views on tobacco and cannabis risk is important given that increases in social acceptance and decreases in risk perception may be directly associated with public health and policies,” the investigators write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Julia Chambers, MD, department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The generalizability of the study may be limited by nonresponse and loss to follow-up over time. The wording of survey questions may have introduced bias in respondents. Participants were asked about safety of smoking cannabis joints vs. tobacco cigarettes and not to compare safety of other forms of smoked and vaped cannabis, tobacco, and nicotine.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received support from the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program. Dr. Chambers has no relevant conflicts of interest; author Katherine J. Hoggatt, PhD, MPH, department of medicine, UCSF, reported receiving grants from the Veterans Health Administration during the conduct of the study and grants from the National Institutes of Health, Rubin Family Foundation, and Veterans Health Administration outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

RSV season has started, and this year could be different

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a national alert to health officials Sept. 5, urging them to offer new medicines that can prevent severe cases of the respiratory virus in very young children and in older people. Those two groups are at the highest risk of potentially deadly complications from RSV.

Typically, the CDC considers the start of RSV season to occur when the rate of positive tests for the virus goes above 3% for 2 consecutive weeks. In Florida, the rate has been around 5% in recent weeks, and in Georgia, there has been an increase in RSV-related hospitalizations. Most of the hospitalizations in Georgia have been among infants less than a year old.

“Historically, such regional increases have predicted the beginning of RSV season nationally, with increased RSV activity spreading north and west over the following 2-3 months,” the CDC said.

Most children have been infected with RSV by the time they are 2 years old. Historically, up to 80,000 children under 5 years old are hospitalized annually because of the virus, and between 100 and 300 die from complications each year.

Those figures could be drastically different this year because new preventive treatments are available.

The CDC recommends that all children under 8 months old receive the newly approved monoclonal antibody treatment nirsevimab (Beyfortus). Children up to 19 months old at high risk of severe complications from RSV are also eligible for the single-dose shot. In clinical trials, the treatment was 80% effective at preventing RSV infections from becoming so severe that children had to be hospitalized. The protection lasted about 5 months.

Older people are also at a heightened risk of severe illness from RSV, and two new vaccines are available this season. The vaccines are called Arexvy and Abrysvo, and the single-dose shots are approved for people ages 60 years and older. They are more than 80% effective at making severe lower respiratory complications less likely.

Last year’s RSV season started during the summer and peaked in October and November, which was earlier than usual. There’s no indication yet of when RSV season may peak this year. Last year and throughout the pandemic, RSV held its historical pattern of starting in Florida.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a national alert to health officials Sept. 5, urging them to offer new medicines that can prevent severe cases of the respiratory virus in very young children and in older people. Those two groups are at the highest risk of potentially deadly complications from RSV.

Typically, the CDC considers the start of RSV season to occur when the rate of positive tests for the virus goes above 3% for 2 consecutive weeks. In Florida, the rate has been around 5% in recent weeks, and in Georgia, there has been an increase in RSV-related hospitalizations. Most of the hospitalizations in Georgia have been among infants less than a year old.

“Historically, such regional increases have predicted the beginning of RSV season nationally, with increased RSV activity spreading north and west over the following 2-3 months,” the CDC said.

Most children have been infected with RSV by the time they are 2 years old. Historically, up to 80,000 children under 5 years old are hospitalized annually because of the virus, and between 100 and 300 die from complications each year.

Those figures could be drastically different this year because new preventive treatments are available.

The CDC recommends that all children under 8 months old receive the newly approved monoclonal antibody treatment nirsevimab (Beyfortus). Children up to 19 months old at high risk of severe complications from RSV are also eligible for the single-dose shot. In clinical trials, the treatment was 80% effective at preventing RSV infections from becoming so severe that children had to be hospitalized. The protection lasted about 5 months.

Older people are also at a heightened risk of severe illness from RSV, and two new vaccines are available this season. The vaccines are called Arexvy and Abrysvo, and the single-dose shots are approved for people ages 60 years and older. They are more than 80% effective at making severe lower respiratory complications less likely.

Last year’s RSV season started during the summer and peaked in October and November, which was earlier than usual. There’s no indication yet of when RSV season may peak this year. Last year and throughout the pandemic, RSV held its historical pattern of starting in Florida.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a national alert to health officials Sept. 5, urging them to offer new medicines that can prevent severe cases of the respiratory virus in very young children and in older people. Those two groups are at the highest risk of potentially deadly complications from RSV.

Typically, the CDC considers the start of RSV season to occur when the rate of positive tests for the virus goes above 3% for 2 consecutive weeks. In Florida, the rate has been around 5% in recent weeks, and in Georgia, there has been an increase in RSV-related hospitalizations. Most of the hospitalizations in Georgia have been among infants less than a year old.

“Historically, such regional increases have predicted the beginning of RSV season nationally, with increased RSV activity spreading north and west over the following 2-3 months,” the CDC said.

Most children have been infected with RSV by the time they are 2 years old. Historically, up to 80,000 children under 5 years old are hospitalized annually because of the virus, and between 100 and 300 die from complications each year.

Those figures could be drastically different this year because new preventive treatments are available.

The CDC recommends that all children under 8 months old receive the newly approved monoclonal antibody treatment nirsevimab (Beyfortus). Children up to 19 months old at high risk of severe complications from RSV are also eligible for the single-dose shot. In clinical trials, the treatment was 80% effective at preventing RSV infections from becoming so severe that children had to be hospitalized. The protection lasted about 5 months.

Older people are also at a heightened risk of severe illness from RSV, and two new vaccines are available this season. The vaccines are called Arexvy and Abrysvo, and the single-dose shots are approved for people ages 60 years and older. They are more than 80% effective at making severe lower respiratory complications less likely.

Last year’s RSV season started during the summer and peaked in October and November, which was earlier than usual. There’s no indication yet of when RSV season may peak this year. Last year and throughout the pandemic, RSV held its historical pattern of starting in Florida.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

New Moderna vaccine to work against recent COVID variant

“The company said its shot generated an 8.7-fold increase in neutralizing antibodies in humans against BA.2.86, which is being tracked by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” Reuters reported.

“We think this is news people will want to hear as they prepare to go out and get their fall boosters,” Jacqueline Miller, Moderna head of infectious diseases, told the news agency.

The CDC said that the BA.2.86 variant might be more likely to infect people who have already had COVID or previous vaccinations. BA.2.86 is an Omicron variant. It has undergone more mutations than XBB.1.5, which has dominated most of this year and was the intended target of the updated shots.

BA.2.86 does not have a strong presence in the United States yet. However, officials are concerned about its high number of mutations, NBC News reported.

The FDA is expected to approve the new Moderna shot by early October.

Pfizer told NBC that its updated booster also generated a strong antibody response against Omicron variants, including BA.2.86.

COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations have been increasing in the U.S. because of the rise of several variants.

Experts told Reuters that BA.2.86 probably won’t cause a wave of severe disease and death because immunity has been built up around the world through previous infections and mass vaccinations.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

“The company said its shot generated an 8.7-fold increase in neutralizing antibodies in humans against BA.2.86, which is being tracked by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” Reuters reported.

“We think this is news people will want to hear as they prepare to go out and get their fall boosters,” Jacqueline Miller, Moderna head of infectious diseases, told the news agency.

The CDC said that the BA.2.86 variant might be more likely to infect people who have already had COVID or previous vaccinations. BA.2.86 is an Omicron variant. It has undergone more mutations than XBB.1.5, which has dominated most of this year and was the intended target of the updated shots.

BA.2.86 does not have a strong presence in the United States yet. However, officials are concerned about its high number of mutations, NBC News reported.

The FDA is expected to approve the new Moderna shot by early October.

Pfizer told NBC that its updated booster also generated a strong antibody response against Omicron variants, including BA.2.86.

COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations have been increasing in the U.S. because of the rise of several variants.

Experts told Reuters that BA.2.86 probably won’t cause a wave of severe disease and death because immunity has been built up around the world through previous infections and mass vaccinations.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

“The company said its shot generated an 8.7-fold increase in neutralizing antibodies in humans against BA.2.86, which is being tracked by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,” Reuters reported.

“We think this is news people will want to hear as they prepare to go out and get their fall boosters,” Jacqueline Miller, Moderna head of infectious diseases, told the news agency.

The CDC said that the BA.2.86 variant might be more likely to infect people who have already had COVID or previous vaccinations. BA.2.86 is an Omicron variant. It has undergone more mutations than XBB.1.5, which has dominated most of this year and was the intended target of the updated shots.

BA.2.86 does not have a strong presence in the United States yet. However, officials are concerned about its high number of mutations, NBC News reported.

The FDA is expected to approve the new Moderna shot by early October.

Pfizer told NBC that its updated booster also generated a strong antibody response against Omicron variants, including BA.2.86.

COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations have been increasing in the U.S. because of the rise of several variants.

Experts told Reuters that BA.2.86 probably won’t cause a wave of severe disease and death because immunity has been built up around the world through previous infections and mass vaccinations.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

How do you prescribe exercise in primary prevention?

To avoid cardiovascular disease, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends performing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity every week, 75 minutes of intense aerobic activity every week, or a combination of both, preferably spread out throughout the week. But how knowledgeable are physicians when it comes to prescribing exercise, and how should patients be assessed so that appropriate physical activity can be recommended?

In a presentation titled, “Patient Evaluation and Exercise Prescription in Primary Prevention,”

“Exercise has cardioprotective, emotional, antiarrhythmic, and antithrombotic benefits, and it reduces stress,” she explained.

She also noted that the risk regarding cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal components must be evaluated, because exercise can itself trigger coronary events, and the last thing intended when prescribing exercise is to cause complications. “We must recommend exercise progressively. We can’t suggest a high-intensity regimen to a patient if they haven’t had any preconditioning where collateral circulation could be developed and lung and cardiac capacity could be improved.”

Dr. Sánchez went on to say that, according to the AHA, patients should be classified as follows: those who exercise and those who don’t, those with a history of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, and those with symptomatic and asymptomatic diseases, in order to consider the parameters when recommending exercise.

“If the patient has symptoms and is doing light physical activity, like walking, they can keep doing this exercise and don’t need further assessments. But if they have a symptomatic disease and are not exercising, they need to be evaluated after exercise has been prescribed, and not just clinically, either. Some sort of diagnostic method should be considered. Also, for patients who are physically active and who desire to increase the intensity of their exercise, the recommendation is to perform a detailed clinical examination and, if necessary, perform additional imaging studies.”

Warning signs

- Dizziness.

- Orthopnea.

- Abnormal heart rate.

- Edema in the lower extremities.

- Chest pain, especially when occurring with exercise.

- Intermittent claudication.

- Heart murmurs.

- Dyspnea.

- Reduced output.

- Fatigue.

Calibrating exercise parameters

The parameters of frequency (number of sessions per week), intensity (perceived exertion measured by heart rate reached), time, and type (aerobic exercise vs. strength training) should be considered when forming an appropriate prescription for exercise, explained Dr. Sánchez.

“The big problem is that most physicians don’t know how to prescribe it properly. And beyond knowing how, the important thing is that, when we’re with the patient during the consultation, we ought to be doing more than just establishing a routine. We need to be motivators and we need to be identifying obstacles and the patient’s interest in exercise, because it’s clear that incorporating physical activity into our daily lives helps improve the quality and length of life,” the specialist added.

The recommendations are straightforward: for individuals aged 18-64 years, 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week, whether aerobic, strength training, or mixed, should be prescribed. “We need to encourage moving more and sitting less, and recommend comprehensive programs that include coordination, balance, and muscle strengthening. If a sedentary lifestyle is a risk factor, we need to encourage patients to start performing physical activity for 1-2 minutes every hour, because any exercise must be gradual and progressive to avoid complications,” she noted.

Evaluate, then recommend

The specialist emphasized the importance of making personalized prescriptions, exercising caution, and performing adequate assessments to know which exercise routine to recommend. “The patient should also be involved in their self-care and must have an adequate diet and hydration, and we need to remind them that they shouldn’t be exercising if they have an infection, due to the risk of myocarditis and sudden death,” she added.

Rafaelina Concepción, MD, cardiologist from the Dominican Republic and vice president of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology for Central America and the Caribbean, agreed with the importance of assessing risk and risk factors for patients who request an exercise routine. “For example, in patients with prediabetes, it has been shown that exercising can slow the progression to diabetes. The essential thing is to use stratification and know what kind of exercise to recommend, whether aerobic, strength training, or a combination of the two, to improve functional capacity without reaching the threshold heart rate while reducing the risk of other comorbidities like hypertension, obesity, and high lipids, and achieving lifestyle changes.”

Carlos Franco, MD, a cardiologist in El Salvador, emphasized that there is no such thing as zero risk when evaluating a patient. “Of course, there’s a difference between an athlete and someone who isn’t physically active, but we need to profile all patients correctly, evaluate risk factors in detail, not overlook subclinical cardiovascular disease, and check whether they need stress testing or additional imaging to assess cardiac functional capacity. Also, exercise must be prescribed gradually, and the patient’s nutritional status must be assessed.”

Dr. Franco ended by explaining that physicians must understand how to prescribe the basics of exercise and make small interventions of reasonable intensity, provide practical advice, and, to the extent possible, rely on specialists such as physiatrists, sports specialists, and physical therapists.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

To avoid cardiovascular disease, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends performing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity every week, 75 minutes of intense aerobic activity every week, or a combination of both, preferably spread out throughout the week. But how knowledgeable are physicians when it comes to prescribing exercise, and how should patients be assessed so that appropriate physical activity can be recommended?

In a presentation titled, “Patient Evaluation and Exercise Prescription in Primary Prevention,”

“Exercise has cardioprotective, emotional, antiarrhythmic, and antithrombotic benefits, and it reduces stress,” she explained.

She also noted that the risk regarding cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal components must be evaluated, because exercise can itself trigger coronary events, and the last thing intended when prescribing exercise is to cause complications. “We must recommend exercise progressively. We can’t suggest a high-intensity regimen to a patient if they haven’t had any preconditioning where collateral circulation could be developed and lung and cardiac capacity could be improved.”

Dr. Sánchez went on to say that, according to the AHA, patients should be classified as follows: those who exercise and those who don’t, those with a history of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, and those with symptomatic and asymptomatic diseases, in order to consider the parameters when recommending exercise.

“If the patient has symptoms and is doing light physical activity, like walking, they can keep doing this exercise and don’t need further assessments. But if they have a symptomatic disease and are not exercising, they need to be evaluated after exercise has been prescribed, and not just clinically, either. Some sort of diagnostic method should be considered. Also, for patients who are physically active and who desire to increase the intensity of their exercise, the recommendation is to perform a detailed clinical examination and, if necessary, perform additional imaging studies.”

Warning signs

- Dizziness.

- Orthopnea.

- Abnormal heart rate.

- Edema in the lower extremities.

- Chest pain, especially when occurring with exercise.

- Intermittent claudication.

- Heart murmurs.

- Dyspnea.

- Reduced output.

- Fatigue.

Calibrating exercise parameters

The parameters of frequency (number of sessions per week), intensity (perceived exertion measured by heart rate reached), time, and type (aerobic exercise vs. strength training) should be considered when forming an appropriate prescription for exercise, explained Dr. Sánchez.

“The big problem is that most physicians don’t know how to prescribe it properly. And beyond knowing how, the important thing is that, when we’re with the patient during the consultation, we ought to be doing more than just establishing a routine. We need to be motivators and we need to be identifying obstacles and the patient’s interest in exercise, because it’s clear that incorporating physical activity into our daily lives helps improve the quality and length of life,” the specialist added.

The recommendations are straightforward: for individuals aged 18-64 years, 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week, whether aerobic, strength training, or mixed, should be prescribed. “We need to encourage moving more and sitting less, and recommend comprehensive programs that include coordination, balance, and muscle strengthening. If a sedentary lifestyle is a risk factor, we need to encourage patients to start performing physical activity for 1-2 minutes every hour, because any exercise must be gradual and progressive to avoid complications,” she noted.

Evaluate, then recommend

The specialist emphasized the importance of making personalized prescriptions, exercising caution, and performing adequate assessments to know which exercise routine to recommend. “The patient should also be involved in their self-care and must have an adequate diet and hydration, and we need to remind them that they shouldn’t be exercising if they have an infection, due to the risk of myocarditis and sudden death,” she added.

Rafaelina Concepción, MD, cardiologist from the Dominican Republic and vice president of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology for Central America and the Caribbean, agreed with the importance of assessing risk and risk factors for patients who request an exercise routine. “For example, in patients with prediabetes, it has been shown that exercising can slow the progression to diabetes. The essential thing is to use stratification and know what kind of exercise to recommend, whether aerobic, strength training, or a combination of the two, to improve functional capacity without reaching the threshold heart rate while reducing the risk of other comorbidities like hypertension, obesity, and high lipids, and achieving lifestyle changes.”

Carlos Franco, MD, a cardiologist in El Salvador, emphasized that there is no such thing as zero risk when evaluating a patient. “Of course, there’s a difference between an athlete and someone who isn’t physically active, but we need to profile all patients correctly, evaluate risk factors in detail, not overlook subclinical cardiovascular disease, and check whether they need stress testing or additional imaging to assess cardiac functional capacity. Also, exercise must be prescribed gradually, and the patient’s nutritional status must be assessed.”

Dr. Franco ended by explaining that physicians must understand how to prescribe the basics of exercise and make small interventions of reasonable intensity, provide practical advice, and, to the extent possible, rely on specialists such as physiatrists, sports specialists, and physical therapists.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

To avoid cardiovascular disease, the American Heart Association (AHA) recommends performing at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity every week, 75 minutes of intense aerobic activity every week, or a combination of both, preferably spread out throughout the week. But how knowledgeable are physicians when it comes to prescribing exercise, and how should patients be assessed so that appropriate physical activity can be recommended?

In a presentation titled, “Patient Evaluation and Exercise Prescription in Primary Prevention,”

“Exercise has cardioprotective, emotional, antiarrhythmic, and antithrombotic benefits, and it reduces stress,” she explained.

She also noted that the risk regarding cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal components must be evaluated, because exercise can itself trigger coronary events, and the last thing intended when prescribing exercise is to cause complications. “We must recommend exercise progressively. We can’t suggest a high-intensity regimen to a patient if they haven’t had any preconditioning where collateral circulation could be developed and lung and cardiac capacity could be improved.”

Dr. Sánchez went on to say that, according to the AHA, patients should be classified as follows: those who exercise and those who don’t, those with a history of cardiovascular, metabolic, or renal disease, and those with symptomatic and asymptomatic diseases, in order to consider the parameters when recommending exercise.

“If the patient has symptoms and is doing light physical activity, like walking, they can keep doing this exercise and don’t need further assessments. But if they have a symptomatic disease and are not exercising, they need to be evaluated after exercise has been prescribed, and not just clinically, either. Some sort of diagnostic method should be considered. Also, for patients who are physically active and who desire to increase the intensity of their exercise, the recommendation is to perform a detailed clinical examination and, if necessary, perform additional imaging studies.”

Warning signs

- Dizziness.

- Orthopnea.

- Abnormal heart rate.

- Edema in the lower extremities.

- Chest pain, especially when occurring with exercise.

- Intermittent claudication.

- Heart murmurs.

- Dyspnea.

- Reduced output.

- Fatigue.

Calibrating exercise parameters

The parameters of frequency (number of sessions per week), intensity (perceived exertion measured by heart rate reached), time, and type (aerobic exercise vs. strength training) should be considered when forming an appropriate prescription for exercise, explained Dr. Sánchez.

“The big problem is that most physicians don’t know how to prescribe it properly. And beyond knowing how, the important thing is that, when we’re with the patient during the consultation, we ought to be doing more than just establishing a routine. We need to be motivators and we need to be identifying obstacles and the patient’s interest in exercise, because it’s clear that incorporating physical activity into our daily lives helps improve the quality and length of life,” the specialist added.

The recommendations are straightforward: for individuals aged 18-64 years, 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week, whether aerobic, strength training, or mixed, should be prescribed. “We need to encourage moving more and sitting less, and recommend comprehensive programs that include coordination, balance, and muscle strengthening. If a sedentary lifestyle is a risk factor, we need to encourage patients to start performing physical activity for 1-2 minutes every hour, because any exercise must be gradual and progressive to avoid complications,” she noted.

Evaluate, then recommend

The specialist emphasized the importance of making personalized prescriptions, exercising caution, and performing adequate assessments to know which exercise routine to recommend. “The patient should also be involved in their self-care and must have an adequate diet and hydration, and we need to remind them that they shouldn’t be exercising if they have an infection, due to the risk of myocarditis and sudden death,” she added.

Rafaelina Concepción, MD, cardiologist from the Dominican Republic and vice president of the Inter-American Society of Cardiology for Central America and the Caribbean, agreed with the importance of assessing risk and risk factors for patients who request an exercise routine. “For example, in patients with prediabetes, it has been shown that exercising can slow the progression to diabetes. The essential thing is to use stratification and know what kind of exercise to recommend, whether aerobic, strength training, or a combination of the two, to improve functional capacity without reaching the threshold heart rate while reducing the risk of other comorbidities like hypertension, obesity, and high lipids, and achieving lifestyle changes.”

Carlos Franco, MD, a cardiologist in El Salvador, emphasized that there is no such thing as zero risk when evaluating a patient. “Of course, there’s a difference between an athlete and someone who isn’t physically active, but we need to profile all patients correctly, evaluate risk factors in detail, not overlook subclinical cardiovascular disease, and check whether they need stress testing or additional imaging to assess cardiac functional capacity. Also, exercise must be prescribed gradually, and the patient’s nutritional status must be assessed.”

Dr. Franco ended by explaining that physicians must understand how to prescribe the basics of exercise and make small interventions of reasonable intensity, provide practical advice, and, to the extent possible, rely on specialists such as physiatrists, sports specialists, and physical therapists.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID and new migraines: What’s the link?

.

“I’ve also noticed visual disturbances, like flickering lights or blurred vision, which I later learned are called auras,” the 30-year-old medical billing specialist in Seattle told this news organization.

Mr. Solomon isn’t alone. It’s estimated that 1 out of 8 people with COVID develop long COVID. Of those persons, 44% also experience headaches. Research has found that many of those headaches are migraines – and many patients who are afflicted say they had never had a migraine before. These migraines tend to persist for at least 5 or 6 months, according to data from the American Headache Society.

What’s more, other patients may suddenly have more frequent or intense versions of headaches they’ve not noticed before.

The mechanism as to how long COVID could manifest migraines is not yet fully understood, but many doctors believe that inflammation caused by the virus plays a key role.

“To understand why some patients have migraine in long COVID, we have to go back to understand the role of inflammation in COVID-19 itself,” says Emad Estemalik, MD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and section head of headache medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

In COVID-19, inflammation occurs because of a cytokine storm. Cytokines, which are proteins essential for a strong immune system, can be overproduced in a patient with COVID, which causes too much inflammation in any organ in the body, including the brain. This can result in new daily headache for some patients.

A new study from Italian researchers found that many patients who develop migraines for the first time while ill with long COVID are middle-aged women (traditionally a late point in life for a first migraine) who have a family history of migraine. Potential causes could have to do with the immune system remaining persistently activated from inflammation during long COVID, as well as the activation of the trigeminovascular system in the brain, which contains neurons that can trigger a migraine.

What treatments can work for migraines related to long COVID?

Long COVID usually causes a constellation of other symptoms at the same time as migraine.

“It’s so important for patients to take an interdisciplinary approach,” Dr. Estemalik stresses. “Patients should make sure their doctors are addressing all of their symptoms.”

When it comes to specifically targeting migraines, standard treatments can be effective.

“In terms of treating migraine in long COVID patients, we don’t do anything different or special,” says Matthew E. Fink, MD, chair of neurology at Weill Cornell Medical College and chief of the Division of Stroke and Critical Care Neurology at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “We treat these patients with standard migraine medications.”

Mr. Solomon is following this course of action.

“My doctor prescribed triptans, which have been somewhat effective in reducing the severity and duration of the migraines,” he says. A daily supplement of magnesium and a daily dose of aspirin can also work for some patients, according to Dr. Fink.

Lifestyle modification is also a great idea.

“Patients should keep regular sleep hours, getting up and going to bed at the same time every day,” Dr. Fink continues. “Daily exercise is also recommended.”

Mr. Solomon suggests tracking migraine triggers and patterns in a journal.

“Try to identify lifestyle changes that help, like managing stress and staying hydrated,” Mr. Solomon advises. “Seeking support from health care professionals and support groups can make a significant difference.”

The best news of all: for patients that are diligent in following these strategies, they’ve been proven to work.

“We doctors are very optimistic when it comes to good outcomes for patients with long COVID and migraine,” Dr. Fink says. “I reassure my patients by telling them, ‘You will get better long-term.’ ”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

“I’ve also noticed visual disturbances, like flickering lights or blurred vision, which I later learned are called auras,” the 30-year-old medical billing specialist in Seattle told this news organization.

Mr. Solomon isn’t alone. It’s estimated that 1 out of 8 people with COVID develop long COVID. Of those persons, 44% also experience headaches. Research has found that many of those headaches are migraines – and many patients who are afflicted say they had never had a migraine before. These migraines tend to persist for at least 5 or 6 months, according to data from the American Headache Society.

What’s more, other patients may suddenly have more frequent or intense versions of headaches they’ve not noticed before.

The mechanism as to how long COVID could manifest migraines is not yet fully understood, but many doctors believe that inflammation caused by the virus plays a key role.

“To understand why some patients have migraine in long COVID, we have to go back to understand the role of inflammation in COVID-19 itself,” says Emad Estemalik, MD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and section head of headache medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

In COVID-19, inflammation occurs because of a cytokine storm. Cytokines, which are proteins essential for a strong immune system, can be overproduced in a patient with COVID, which causes too much inflammation in any organ in the body, including the brain. This can result in new daily headache for some patients.

A new study from Italian researchers found that many patients who develop migraines for the first time while ill with long COVID are middle-aged women (traditionally a late point in life for a first migraine) who have a family history of migraine. Potential causes could have to do with the immune system remaining persistently activated from inflammation during long COVID, as well as the activation of the trigeminovascular system in the brain, which contains neurons that can trigger a migraine.

What treatments can work for migraines related to long COVID?

Long COVID usually causes a constellation of other symptoms at the same time as migraine.

“It’s so important for patients to take an interdisciplinary approach,” Dr. Estemalik stresses. “Patients should make sure their doctors are addressing all of their symptoms.”

When it comes to specifically targeting migraines, standard treatments can be effective.

“In terms of treating migraine in long COVID patients, we don’t do anything different or special,” says Matthew E. Fink, MD, chair of neurology at Weill Cornell Medical College and chief of the Division of Stroke and Critical Care Neurology at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “We treat these patients with standard migraine medications.”

Mr. Solomon is following this course of action.

“My doctor prescribed triptans, which have been somewhat effective in reducing the severity and duration of the migraines,” he says. A daily supplement of magnesium and a daily dose of aspirin can also work for some patients, according to Dr. Fink.

Lifestyle modification is also a great idea.

“Patients should keep regular sleep hours, getting up and going to bed at the same time every day,” Dr. Fink continues. “Daily exercise is also recommended.”

Mr. Solomon suggests tracking migraine triggers and patterns in a journal.

“Try to identify lifestyle changes that help, like managing stress and staying hydrated,” Mr. Solomon advises. “Seeking support from health care professionals and support groups can make a significant difference.”

The best news of all: for patients that are diligent in following these strategies, they’ve been proven to work.

“We doctors are very optimistic when it comes to good outcomes for patients with long COVID and migraine,” Dr. Fink says. “I reassure my patients by telling them, ‘You will get better long-term.’ ”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

“I’ve also noticed visual disturbances, like flickering lights or blurred vision, which I later learned are called auras,” the 30-year-old medical billing specialist in Seattle told this news organization.

Mr. Solomon isn’t alone. It’s estimated that 1 out of 8 people with COVID develop long COVID. Of those persons, 44% also experience headaches. Research has found that many of those headaches are migraines – and many patients who are afflicted say they had never had a migraine before. These migraines tend to persist for at least 5 or 6 months, according to data from the American Headache Society.

What’s more, other patients may suddenly have more frequent or intense versions of headaches they’ve not noticed before.

The mechanism as to how long COVID could manifest migraines is not yet fully understood, but many doctors believe that inflammation caused by the virus plays a key role.

“To understand why some patients have migraine in long COVID, we have to go back to understand the role of inflammation in COVID-19 itself,” says Emad Estemalik, MD, clinical assistant professor of neurology at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine and section head of headache medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

In COVID-19, inflammation occurs because of a cytokine storm. Cytokines, which are proteins essential for a strong immune system, can be overproduced in a patient with COVID, which causes too much inflammation in any organ in the body, including the brain. This can result in new daily headache for some patients.

A new study from Italian researchers found that many patients who develop migraines for the first time while ill with long COVID are middle-aged women (traditionally a late point in life for a first migraine) who have a family history of migraine. Potential causes could have to do with the immune system remaining persistently activated from inflammation during long COVID, as well as the activation of the trigeminovascular system in the brain, which contains neurons that can trigger a migraine.

What treatments can work for migraines related to long COVID?

Long COVID usually causes a constellation of other symptoms at the same time as migraine.

“It’s so important for patients to take an interdisciplinary approach,” Dr. Estemalik stresses. “Patients should make sure their doctors are addressing all of their symptoms.”

When it comes to specifically targeting migraines, standard treatments can be effective.

“In terms of treating migraine in long COVID patients, we don’t do anything different or special,” says Matthew E. Fink, MD, chair of neurology at Weill Cornell Medical College and chief of the Division of Stroke and Critical Care Neurology at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. “We treat these patients with standard migraine medications.”

Mr. Solomon is following this course of action.

“My doctor prescribed triptans, which have been somewhat effective in reducing the severity and duration of the migraines,” he says. A daily supplement of magnesium and a daily dose of aspirin can also work for some patients, according to Dr. Fink.

Lifestyle modification is also a great idea.

“Patients should keep regular sleep hours, getting up and going to bed at the same time every day,” Dr. Fink continues. “Daily exercise is also recommended.”

Mr. Solomon suggests tracking migraine triggers and patterns in a journal.

“Try to identify lifestyle changes that help, like managing stress and staying hydrated,” Mr. Solomon advises. “Seeking support from health care professionals and support groups can make a significant difference.”

The best news of all: for patients that are diligent in following these strategies, they’ve been proven to work.

“We doctors are very optimistic when it comes to good outcomes for patients with long COVID and migraine,” Dr. Fink says. “I reassure my patients by telling them, ‘You will get better long-term.’ ”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Adaptive treatment aids smoking cessation

Smokers who followed an adaptive treatment regimen with drug patches had greater smoking abstinence after 12 weeks than did those who followed a standard regimen, based on data from 188 individuals.

Adaptive pharmacotherapy is a common strategy across many medical conditions, but its use in smoking cessation treatments involving skin patches has not been examined, wrote James M. Davis, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 188 adults who sought smoking cessation treatment at a university health system between February 2018 and May 2020. The researchers planned to enroll 300 adults, but enrollment was truncated because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants chose between varenicline or nicotine patches, and then were randomized to an adaptive or standard treatment regimen. All participants started their medication 4 weeks before their target quit smoking day.

A total of 127 participants chose varenicline, with 64 randomized to adaptive treatment and 63 randomized to standard treatment; 61 participants chose nicotine patches, with 31 randomized to adaptive treatment and 30 randomized to standard treatment. Overall, participants smoked a mean of 15.4 cigarettes per day at baseline. The mean age of the participants was 49.1 years; 54% were female, 52% were White, and 48% were Black. Baseline demographics were similar between the groups.

The primary outcome was 30-day continuous abstinence from smoking (biochemically verified) at 12 weeks after each participant’s target quit date.

After 2 weeks (2 weeks before the target quit smoking day), all participants were assessed for treatment response. Those in the adaptive group who were deemed responders, defined as a reduction in daily cigarettes of at least 50%, received placebo bupropion. Those in the adaptive group deemed nonresponders received 150 mg bupropion twice daily in addition to their patch regimen. The standard treatment group also received placebo bupropion.

At 12 weeks after the target quit day, 24% of the adaptive group demonstrated 30-day continuous smoking abstinence, compared with 9% of the standard group (odds ratio, 3.38; P = .004). Smoking abstinence was higher in the adaptive vs. placebo groups for those who used varenicline patches (28% vs. 8%; OR, 4.54) and for those who used nicotine patches (16% vs. 10%; OR, 1.73).

In addition, 7-day smoking abstinence measured at a 2-week postquit day visit was three times higher in the adaptive group compared with the standard treatment group (32% vs. 11%; OR, 3.30).

No incidents of death, life-threatening events, hospitalization, or persistent or significant disability or incapacity related to the study were reported; one death in the varenicline group was attributable to stage 4 cancer.

The findings were limited by several factors including the few or no participants of Alaska Native, American Indian, Hispanic, or Pacific Islander ethnicities, or those who were multiracial. The free medication and modest compensation for study visits further reduce generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the smaller-than-intended sample size and inability to assess individual components of adaptive treatment, they said.

However, the results support the value of adaptive treatment and suggest that adaptive treatment with precessation varenicline or nicotine patches followed by bupropion for nonresponders is more effective than standard treatment for smoking cessation.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the varenicline was provided by Pfizer. Dr. Davis had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Smokers who followed an adaptive treatment regimen with drug patches had greater smoking abstinence after 12 weeks than did those who followed a standard regimen, based on data from 188 individuals.

Adaptive pharmacotherapy is a common strategy across many medical conditions, but its use in smoking cessation treatments involving skin patches has not been examined, wrote James M. Davis, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 188 adults who sought smoking cessation treatment at a university health system between February 2018 and May 2020. The researchers planned to enroll 300 adults, but enrollment was truncated because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants chose between varenicline or nicotine patches, and then were randomized to an adaptive or standard treatment regimen. All participants started their medication 4 weeks before their target quit smoking day.

A total of 127 participants chose varenicline, with 64 randomized to adaptive treatment and 63 randomized to standard treatment; 61 participants chose nicotine patches, with 31 randomized to adaptive treatment and 30 randomized to standard treatment. Overall, participants smoked a mean of 15.4 cigarettes per day at baseline. The mean age of the participants was 49.1 years; 54% were female, 52% were White, and 48% were Black. Baseline demographics were similar between the groups.

The primary outcome was 30-day continuous abstinence from smoking (biochemically verified) at 12 weeks after each participant’s target quit date.

After 2 weeks (2 weeks before the target quit smoking day), all participants were assessed for treatment response. Those in the adaptive group who were deemed responders, defined as a reduction in daily cigarettes of at least 50%, received placebo bupropion. Those in the adaptive group deemed nonresponders received 150 mg bupropion twice daily in addition to their patch regimen. The standard treatment group also received placebo bupropion.

At 12 weeks after the target quit day, 24% of the adaptive group demonstrated 30-day continuous smoking abstinence, compared with 9% of the standard group (odds ratio, 3.38; P = .004). Smoking abstinence was higher in the adaptive vs. placebo groups for those who used varenicline patches (28% vs. 8%; OR, 4.54) and for those who used nicotine patches (16% vs. 10%; OR, 1.73).

In addition, 7-day smoking abstinence measured at a 2-week postquit day visit was three times higher in the adaptive group compared with the standard treatment group (32% vs. 11%; OR, 3.30).

No incidents of death, life-threatening events, hospitalization, or persistent or significant disability or incapacity related to the study were reported; one death in the varenicline group was attributable to stage 4 cancer.

The findings were limited by several factors including the few or no participants of Alaska Native, American Indian, Hispanic, or Pacific Islander ethnicities, or those who were multiracial. The free medication and modest compensation for study visits further reduce generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the smaller-than-intended sample size and inability to assess individual components of adaptive treatment, they said.

However, the results support the value of adaptive treatment and suggest that adaptive treatment with precessation varenicline or nicotine patches followed by bupropion for nonresponders is more effective than standard treatment for smoking cessation.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the varenicline was provided by Pfizer. Dr. Davis had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Smokers who followed an adaptive treatment regimen with drug patches had greater smoking abstinence after 12 weeks than did those who followed a standard regimen, based on data from 188 individuals.

Adaptive pharmacotherapy is a common strategy across many medical conditions, but its use in smoking cessation treatments involving skin patches has not been examined, wrote James M. Davis, MD, of Duke University, Durham, N.C., and colleagues.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers reviewed data from 188 adults who sought smoking cessation treatment at a university health system between February 2018 and May 2020. The researchers planned to enroll 300 adults, but enrollment was truncated because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants chose between varenicline or nicotine patches, and then were randomized to an adaptive or standard treatment regimen. All participants started their medication 4 weeks before their target quit smoking day.

A total of 127 participants chose varenicline, with 64 randomized to adaptive treatment and 63 randomized to standard treatment; 61 participants chose nicotine patches, with 31 randomized to adaptive treatment and 30 randomized to standard treatment. Overall, participants smoked a mean of 15.4 cigarettes per day at baseline. The mean age of the participants was 49.1 years; 54% were female, 52% were White, and 48% were Black. Baseline demographics were similar between the groups.

The primary outcome was 30-day continuous abstinence from smoking (biochemically verified) at 12 weeks after each participant’s target quit date.

After 2 weeks (2 weeks before the target quit smoking day), all participants were assessed for treatment response. Those in the adaptive group who were deemed responders, defined as a reduction in daily cigarettes of at least 50%, received placebo bupropion. Those in the adaptive group deemed nonresponders received 150 mg bupropion twice daily in addition to their patch regimen. The standard treatment group also received placebo bupropion.

At 12 weeks after the target quit day, 24% of the adaptive group demonstrated 30-day continuous smoking abstinence, compared with 9% of the standard group (odds ratio, 3.38; P = .004). Smoking abstinence was higher in the adaptive vs. placebo groups for those who used varenicline patches (28% vs. 8%; OR, 4.54) and for those who used nicotine patches (16% vs. 10%; OR, 1.73).

In addition, 7-day smoking abstinence measured at a 2-week postquit day visit was three times higher in the adaptive group compared with the standard treatment group (32% vs. 11%; OR, 3.30).

No incidents of death, life-threatening events, hospitalization, or persistent or significant disability or incapacity related to the study were reported; one death in the varenicline group was attributable to stage 4 cancer.

The findings were limited by several factors including the few or no participants of Alaska Native, American Indian, Hispanic, or Pacific Islander ethnicities, or those who were multiracial. The free medication and modest compensation for study visits further reduce generalizability, the researchers noted. Other limitations included the smaller-than-intended sample size and inability to assess individual components of adaptive treatment, they said.

However, the results support the value of adaptive treatment and suggest that adaptive treatment with precessation varenicline or nicotine patches followed by bupropion for nonresponders is more effective than standard treatment for smoking cessation.

The study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse; the varenicline was provided by Pfizer. Dr. Davis had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Depression Workup

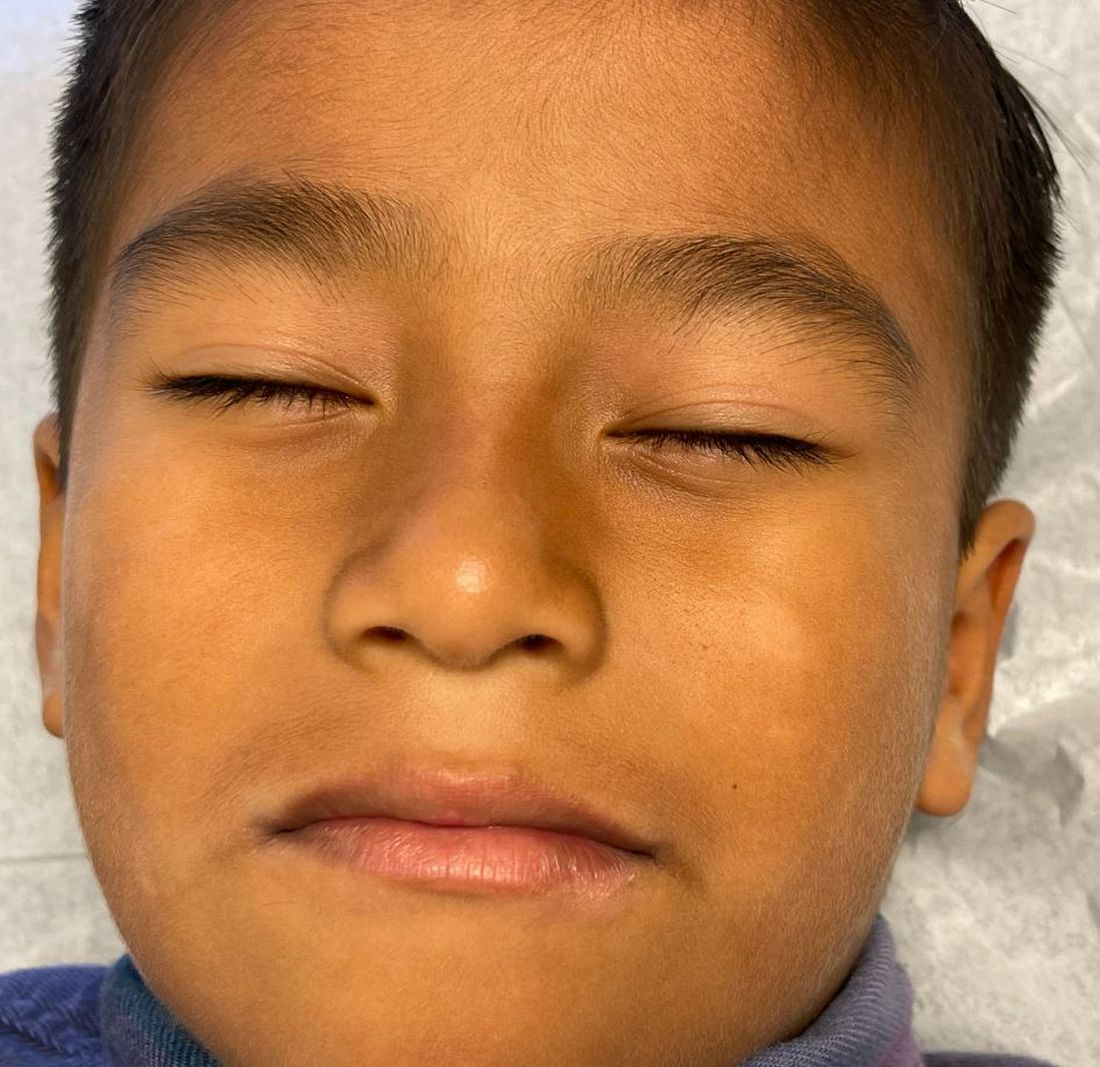

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: A

Pityriasis alba is a common benign skin disorder that presents as hypopigmented skin most noticeable in darker skin types. It presents as whitish or mildly erythematous patches, commonly on the face, though it can appear on the trunk and extremities as well. It is estimated that about 1% of the general population is affected and may be more common after months with more extended sun exposure.

While a specific cause has not been identified, it is thought to represent post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and is thought by many experts to be more common in atopic individuals; it is considered a minor clinical criterion for atopic dermatitis. The name relates to its appearance at times being scaly (pityriasis) and its whitish coloration (alba) and may represent a non-specific dermatitis.

It occurs predominantly in children and adolescents, and a slight male predominance has been noted. Even though this condition is not seasonal, the lesions become more obvious in the spring and summer because of sun exposure and darkening of the surrounding normal skin.

Physical examination reveals multiple round or oval shaped hypopigmented poorly defined macules, patches, or thin plaques. Mild scaling may be present. The number of lesions is variable. The most common presentation is asymptomatic, although some patients report mild pruritus. Two infrequent variants have been reported. Pigmented pityriasis is mostly reported in patients with darker skin in South Africa and the Middle East and presents with hyperpigmented bluish patches surrounded by a hypopigmented ring. Extensive pityriasis alba is another uncommon variant, characterized by widespread symmetrical lesions distributed predominantly on the trunk. Seborrheic dermatitis presents as a mild form of dandruff, often with asymptomatic or mildly itchy scalp with scaling, though involvement of the face can be seen around the eyebrows, glabella, and nasolabial areas.

Less common conditions in the differential diagnosis include other inflammatory conditions (contact dermatitis, psoriasis), genodermatoses (such as ash-leaf macules of tuberous sclerosis), infectious diseases (leprosy, and tinea corporis or faciei) and nevoid conditions (such as nevus anemicus). Leprosy is tremendously rare in children in the United States and can present as sharply demarcated usually elevated plaques often with diminished sensation. Hypopigmentation secondary to topical medications or skin procedures should also be considered. When encountering chronic, refractory, or extensive cases, an alarm for pityriasis lichenoides chronica and cutaneous lymphoma (hypopigmented mycosis fungoides) might be considered.

Pityriasis alba is a self-limited condition with a good prognosis and expected complete resolution, most commonly within 1 year. Patients and their parents should be educated regarding the benign and self-limited nature of pityriasis alba. Affected areas should be sun-protected to avoid worsening of the cosmetic appearance and prevent sunburn in the hypopigmented areas. The frequent use of emollients is the mainstay of treatment. Some topical treatments may reduce erythema and pruritus and accelerate repigmentation. Low-potency topical steroids, such as 1% hydrocortisone, are an alternative treatment, especially when itchiness is present. Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as 0.1% tacrolimus or 1% pimecrolimus have also been reported to be effective, as well as topical vitamin D derivatives (calcitriol and calcipotriol).

Suggested reading

1. Treat: Abdel-Wahab HM and Ragaie MH. Pityriasis alba: Toward an effective treatment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022 Jun;33(4):2285-9. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1959014. Epub 2021 Aug 1.

2. PEARLS: Givler DN et al. Pityriasis alba. 2023 Feb 19. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

3. Choi SH et al. Pityriasis alba in pediatric patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023 Apr 1;22(4):417-8. doi: 10.36849/JDD.7221.

4. Gawai SR et al. Association of pityriasis alba with atopic dermatitis: A cross-sectional study. Indian J Dermatol. 2021 Sep-Oct;66(5):567-8. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_936_20.

Dr. Guelfand is a visiting dermatology resident in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Vuong is a clinical fellow in the division of pediatric and adolescent dermatology, University of California, San Diego. Dr. Eichenfield is vice chair of the department of dermatology and distinguished professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. No author has any relevant financial disclosures.

Answer: A

Pityriasis alba is a common benign skin disorder that presents as hypopigmented skin most noticeable in darker skin types. It presents as whitish or mildly erythematous patches, commonly on the face, though it can appear on the trunk and extremities as well. It is estimated that about 1% of the general population is affected and may be more common after months with more extended sun exposure.

While a specific cause has not been identified, it is thought to represent post-inflammatory hypopigmentation, and is thought by many experts to be more common in atopic individuals; it is considered a minor clinical criterion for atopic dermatitis. The name relates to its appearance at times being scaly (pityriasis) and its whitish coloration (alba) and may represent a non-specific dermatitis.

It occurs predominantly in children and adolescents, and a slight male predominance has been noted. Even though this condition is not seasonal, the lesions become more obvious in the spring and summer because of sun exposure and darkening of the surrounding normal skin.

Physical examination reveals multiple round or oval shaped hypopigmented poorly defined macules, patches, or thin plaques. Mild scaling may be present. The number of lesions is variable. The most common presentation is asymptomatic, although some patients report mild pruritus. Two infrequent variants have been reported. Pigmented pityriasis is mostly reported in patients with darker skin in South Africa and the Middle East and presents with hyperpigmented bluish patches surrounded by a hypopigmented ring. Extensive pityriasis alba is another uncommon variant, characterized by widespread symmetrical lesions distributed predominantly on the trunk. Seborrheic dermatitis presents as a mild form of dandruff, often with asymptomatic or mildly itchy scalp with scaling, though involvement of the face can be seen around the eyebrows, glabella, and nasolabial areas.

Less common conditions in the differential diagnosis include other inflammatory conditions (contact dermatitis, psoriasis), genodermatoses (such as ash-leaf macules of tuberous sclerosis), infectious diseases (leprosy, and tinea corporis or faciei) and nevoid conditions (such as nevus anemicus). Leprosy is tremendously rare in children in the United States and can present as sharply demarcated usually elevated plaques often with diminished sensation. Hypopigmentation secondary to topical medications or skin procedures should also be considered. When encountering chronic, refractory, or extensive cases, an alarm for pityriasis lichenoides chronica and cutaneous lymphoma (hypopigmented mycosis fungoides) might be considered.

Pityriasis alba is a self-limited condition with a good prognosis and expected complete resolution, most commonly within 1 year. Patients and their parents should be educated regarding the benign and self-limited nature of pityriasis alba. Affected areas should be sun-protected to avoid worsening of the cosmetic appearance and prevent sunburn in the hypopigmented areas. The frequent use of emollients is the mainstay of treatment. Some topical treatments may reduce erythema and pruritus and accelerate repigmentation. Low-potency topical steroids, such as 1% hydrocortisone, are an alternative treatment, especially when itchiness is present. Topical calcineurin inhibitors such as 0.1% tacrolimus or 1% pimecrolimus have also been reported to be effective, as well as topical vitamin D derivatives (calcitriol and calcipotriol).

Suggested reading