User login

Study plots long-term financial impact of diabetes

NEW ORLEANs – Between 2001 and 2013, a cohort of persons with newly diagnosed diabetes spent $3,489 more on average on medical costs in the first year after their diagnosis than they had in the year preceding it. Comparied with their diabetes-free counterparts, patients spent $6,424 more on average in the first year following diagnosis, results from a large data analysis found. In addition, during the period of 9 years before and 9 years after the diagnosis of diabetes, per capita total medical expenditures for the diabetes cohort increased annually by $382, compared with an increase of $177 for the cohort who did not have the condition.

“We know that people with diagnosed diabetes spend more on medical care than those without diagnosed diabetes because of the additional costs associated with managing diabetes and diabetes complications,” lead study author Sundar S. Shrestha, Ph.D., said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “However, little information is available on how much more those with diagnosed diabetes spend after diagnosis than before diagnosis. Also, little information is available on how much more those with diagnosed diabetes spend on medical care, compared with those without diagnosed diabetes.”

Dr. Shrestha, a health economist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his associates, analyzed the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database for the period 2001-2013 to compare the trajectory of medical expenditures (in 2013 U.S. dollars) among a diabetes cohort 9 years before and 9 years after diagnosis with a matched cohort of individuals without diabetes for U.S. adults aged 25-64 years. They defined diabetes incidence as having two or more outpatient claims 30 days apart or at least one inpatient claim with diabetes codes during the case identification period that spanned up to 2 calendar years after the first diabetes claim with at least 2 previous years without any diabetes claim.

Dr. Shrestha reported on 415,728 patient-years of data. The diabetes cohort spent an additional $51,000 on average during the 9 years before and after diagnosis, compared with their counterparts who had no diabetes diagnosis. Overall medical expenditures after diagnosis were also 2.3 times higher than before diagnosis.

“Although the additional expenditure after diagnosis was much higher for people with diagnosed diabetes, after the first year of diagnosis, it did not increase with the duration of diabetes during the study period,” Dr. Shrestha said. “However, the composition of expenditures differed, increasing for prescription drugs and decreasing for inpatient care.” He noted that the estimated excess medical expenditures described in the study indicate that “identifying those at high risk of diabetes, delaying/preventing development of diabetes through a lifestyle change program or other intervention, and managing diabetes effectively could reduce health care costs substantially.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that the data were drawn from a privately insured adult population and therefore may not be generalizable to the entire population of the United States. “Additionally, the data do not allow us to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Shrestha said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANs – Between 2001 and 2013, a cohort of persons with newly diagnosed diabetes spent $3,489 more on average on medical costs in the first year after their diagnosis than they had in the year preceding it. Comparied with their diabetes-free counterparts, patients spent $6,424 more on average in the first year following diagnosis, results from a large data analysis found. In addition, during the period of 9 years before and 9 years after the diagnosis of diabetes, per capita total medical expenditures for the diabetes cohort increased annually by $382, compared with an increase of $177 for the cohort who did not have the condition.

“We know that people with diagnosed diabetes spend more on medical care than those without diagnosed diabetes because of the additional costs associated with managing diabetes and diabetes complications,” lead study author Sundar S. Shrestha, Ph.D., said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “However, little information is available on how much more those with diagnosed diabetes spend after diagnosis than before diagnosis. Also, little information is available on how much more those with diagnosed diabetes spend on medical care, compared with those without diagnosed diabetes.”

Dr. Shrestha, a health economist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his associates, analyzed the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database for the period 2001-2013 to compare the trajectory of medical expenditures (in 2013 U.S. dollars) among a diabetes cohort 9 years before and 9 years after diagnosis with a matched cohort of individuals without diabetes for U.S. adults aged 25-64 years. They defined diabetes incidence as having two or more outpatient claims 30 days apart or at least one inpatient claim with diabetes codes during the case identification period that spanned up to 2 calendar years after the first diabetes claim with at least 2 previous years without any diabetes claim.

Dr. Shrestha reported on 415,728 patient-years of data. The diabetes cohort spent an additional $51,000 on average during the 9 years before and after diagnosis, compared with their counterparts who had no diabetes diagnosis. Overall medical expenditures after diagnosis were also 2.3 times higher than before diagnosis.

“Although the additional expenditure after diagnosis was much higher for people with diagnosed diabetes, after the first year of diagnosis, it did not increase with the duration of diabetes during the study period,” Dr. Shrestha said. “However, the composition of expenditures differed, increasing for prescription drugs and decreasing for inpatient care.” He noted that the estimated excess medical expenditures described in the study indicate that “identifying those at high risk of diabetes, delaying/preventing development of diabetes through a lifestyle change program or other intervention, and managing diabetes effectively could reduce health care costs substantially.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that the data were drawn from a privately insured adult population and therefore may not be generalizable to the entire population of the United States. “Additionally, the data do not allow us to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Shrestha said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANs – Between 2001 and 2013, a cohort of persons with newly diagnosed diabetes spent $3,489 more on average on medical costs in the first year after their diagnosis than they had in the year preceding it. Comparied with their diabetes-free counterparts, patients spent $6,424 more on average in the first year following diagnosis, results from a large data analysis found. In addition, during the period of 9 years before and 9 years after the diagnosis of diabetes, per capita total medical expenditures for the diabetes cohort increased annually by $382, compared with an increase of $177 for the cohort who did not have the condition.

“We know that people with diagnosed diabetes spend more on medical care than those without diagnosed diabetes because of the additional costs associated with managing diabetes and diabetes complications,” lead study author Sundar S. Shrestha, Ph.D., said in an interview in advance of the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. “However, little information is available on how much more those with diagnosed diabetes spend after diagnosis than before diagnosis. Also, little information is available on how much more those with diagnosed diabetes spend on medical care, compared with those without diagnosed diabetes.”

Dr. Shrestha, a health economist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his associates, analyzed the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database for the period 2001-2013 to compare the trajectory of medical expenditures (in 2013 U.S. dollars) among a diabetes cohort 9 years before and 9 years after diagnosis with a matched cohort of individuals without diabetes for U.S. adults aged 25-64 years. They defined diabetes incidence as having two or more outpatient claims 30 days apart or at least one inpatient claim with diabetes codes during the case identification period that spanned up to 2 calendar years after the first diabetes claim with at least 2 previous years without any diabetes claim.

Dr. Shrestha reported on 415,728 patient-years of data. The diabetes cohort spent an additional $51,000 on average during the 9 years before and after diagnosis, compared with their counterparts who had no diabetes diagnosis. Overall medical expenditures after diagnosis were also 2.3 times higher than before diagnosis.

“Although the additional expenditure after diagnosis was much higher for people with diagnosed diabetes, after the first year of diagnosis, it did not increase with the duration of diabetes during the study period,” Dr. Shrestha said. “However, the composition of expenditures differed, increasing for prescription drugs and decreasing for inpatient care.” He noted that the estimated excess medical expenditures described in the study indicate that “identifying those at high risk of diabetes, delaying/preventing development of diabetes through a lifestyle change program or other intervention, and managing diabetes effectively could reduce health care costs substantially.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that the data were drawn from a privately insured adult population and therefore may not be generalizable to the entire population of the United States. “Additionally, the data do not allow us to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes,” Dr. Shrestha said. He reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ADA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Between 2001 and 2013, medical expenditures were significantly greater for patients with diabetes than for those who did not have the condition.

Major finding: The diabetes cohort spent an additional $51,000 on average during the 9 years before and after diagnosis, compared with their diabetes-free counterparts.

Data source: An analysis of 415,728 patient-years of data from the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database for the period 2001-2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Shrestha reported having no financial disclosures.

K. Ravishankar, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

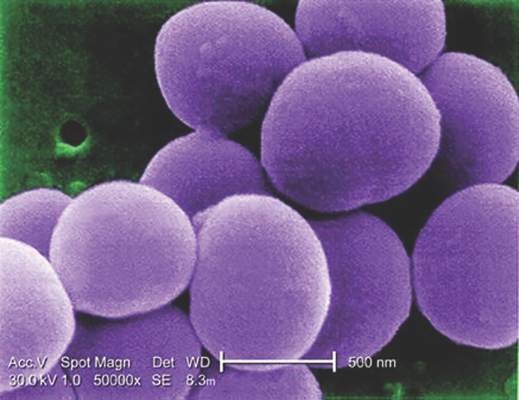

Glucocorticoids increase risk of S. aureus bacteremia

Use of systemic glucocorticoids significantly increased risk for community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB) in a dose-dependent fashion, based on data from a large Danish registry.

On average, current users of systemic glucocorticoids had an adjusted 2.5-fold increased risk of CA-SAB, compared with nonusers. The risk was most pronounced in long-term users of glucocorticoids, including patients with connective tissue disease and patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Among new users of glucocorticoids, the risk of CA-SAB was highest for patients with cancer, in the retrospective, case-control study published by Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Dr. Jesper Smit of Aalborg (Denmark) University and his colleagues, looked at all 2,638 patients admitted with first-time CA-SAB and 26,379 matched population controls in Northern Denmark medical databases between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2011.

New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Risk of CA-SAB rose in a dose-dependent fashion as 90-day cumulative doses increased. For subjects taking a cumulative dose of 150 mg or less, the adjusted OR for CA-SAB was 1.3. At a cumulative dose of 500-1000 mg, OR rose to 2.4. At a cumulative dose greater than 1000 mg, OR was 6.2.

Risk did not differ based on individuals’ sex, age group, or the severity of any comorbidity.

“This is the first study to specifically investigate whether the use of glucocorticoids is associated with increased risk of CA-SAB,” the authors concluded, adding that “these results extend the current knowledge of risk factors for CA-SAB and may serve as a reminder for clinicians to carefully weigh the elevated risk against the potential beneficial effect of glucocorticoid therapy, particularly in patients with concomitant CA-SAB risk factors.”

This study was supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Use of systemic glucocorticoids significantly increased risk for community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB) in a dose-dependent fashion, based on data from a large Danish registry.

On average, current users of systemic glucocorticoids had an adjusted 2.5-fold increased risk of CA-SAB, compared with nonusers. The risk was most pronounced in long-term users of glucocorticoids, including patients with connective tissue disease and patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Among new users of glucocorticoids, the risk of CA-SAB was highest for patients with cancer, in the retrospective, case-control study published by Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Dr. Jesper Smit of Aalborg (Denmark) University and his colleagues, looked at all 2,638 patients admitted with first-time CA-SAB and 26,379 matched population controls in Northern Denmark medical databases between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2011.

New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Risk of CA-SAB rose in a dose-dependent fashion as 90-day cumulative doses increased. For subjects taking a cumulative dose of 150 mg or less, the adjusted OR for CA-SAB was 1.3. At a cumulative dose of 500-1000 mg, OR rose to 2.4. At a cumulative dose greater than 1000 mg, OR was 6.2.

Risk did not differ based on individuals’ sex, age group, or the severity of any comorbidity.

“This is the first study to specifically investigate whether the use of glucocorticoids is associated with increased risk of CA-SAB,” the authors concluded, adding that “these results extend the current knowledge of risk factors for CA-SAB and may serve as a reminder for clinicians to carefully weigh the elevated risk against the potential beneficial effect of glucocorticoid therapy, particularly in patients with concomitant CA-SAB risk factors.”

This study was supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Use of systemic glucocorticoids significantly increased risk for community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB) in a dose-dependent fashion, based on data from a large Danish registry.

On average, current users of systemic glucocorticoids had an adjusted 2.5-fold increased risk of CA-SAB, compared with nonusers. The risk was most pronounced in long-term users of glucocorticoids, including patients with connective tissue disease and patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Among new users of glucocorticoids, the risk of CA-SAB was highest for patients with cancer, in the retrospective, case-control study published by Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Dr. Jesper Smit of Aalborg (Denmark) University and his colleagues, looked at all 2,638 patients admitted with first-time CA-SAB and 26,379 matched population controls in Northern Denmark medical databases between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2011.

New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Risk of CA-SAB rose in a dose-dependent fashion as 90-day cumulative doses increased. For subjects taking a cumulative dose of 150 mg or less, the adjusted OR for CA-SAB was 1.3. At a cumulative dose of 500-1000 mg, OR rose to 2.4. At a cumulative dose greater than 1000 mg, OR was 6.2.

Risk did not differ based on individuals’ sex, age group, or the severity of any comorbidity.

“This is the first study to specifically investigate whether the use of glucocorticoids is associated with increased risk of CA-SAB,” the authors concluded, adding that “these results extend the current knowledge of risk factors for CA-SAB and may serve as a reminder for clinicians to carefully weigh the elevated risk against the potential beneficial effect of glucocorticoid therapy, particularly in patients with concomitant CA-SAB risk factors.”

This study was supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS

Key clinical point: Taking glucocorticoids can significantly increase the risk of contracting community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB).

Major finding: New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Data source: Retrospective, case-control study of all adults with first-time CA-SAB in Northern Denmark medical registries between 2000 and 2011.

Disclosures: Study supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Low-field magnetic stimulation fails to improve refractory depression

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A small proof-of-concept study of low-field magnetic stimulation to augment medical treatment for 85 individuals with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder failed to meet its primary endpoint of significant improvement in core depression symptoms at 48 hours after treatment, though some nonsignificant improvement in mood was seen, compared with sham treatment.

The study’s design did succeed, however, in reducing the substantial placebo response that plagues many clinical trials of treatments for psychiatric illness.

During a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting, Dr. Maurizio Fava shared the results of a double-blind, proof-of-concept trial of low-field magnetic stimulation (LFMS) augmentation of antidepressant therapy for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Overall, patients receiving LFMS saw no significant improvement on an abbreviated 6-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-6), compared with those receiving sham treatment (P = .61). Since the study looked at changes in depression scores just 24 hours after treatment, Dr. Fava said, “We used the HAMD-6, because it’s a more sensitive measure for rapid changes than the HAMD-17.

“Unfortunately, the LFMS did not separate out after 48 hours,” he said.

Nonsignificant differences also were seen for two other rating scales, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The use of a visual analog scale to detect mood changes 120 minutes after treatment did not yield significant differences between those receiving LFMS and those receiving sham.

Many avenues in addition to medication are being explored to provide rapid relief for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), said Dr. Fava, the study’s lead investigator, associate dean for clinical and translational research, and Slater Family Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The six-site Rapidly-Acting Treatments for Treatment-Resistant Depression trial was sham controlled and used a prerandomized sequential parallel comparison design (SPCD). The intervention of LFMS or sham was delivered for 20 minutes daily on 2 consecutive days, and then again for 2 more days after an interim assessment.

“In the second stage of the study, only the patients who had not responded to sham are included,” Dr. Fava said. This is the aspect of an SPCD study that can help to reduce the negative effect on results that can be seen with high placebo response rates, a common phenomenon in psychiatric clinical trials.

“This was a complicated study, involving all kind of methodologic approaches,” said Dr. Fava, noting that each enrollee had the diagnosis of moderate to severe depression (MADRS score equal to or greater than 20) confirmed by two interviewers, including one remote interviewer who was not involved in the study.

Patients who were on a stable dose of antidepressant were included “if they failed to achieve a treatment response after no more than one, but not more than three, treatment courses of antidepressant therapy of at least 8 weeks’ duration,” Dr. Fava said. “We wanted to avoid ‘super-resistance,’ which can reduce the ability to detect a signal” for efficacy, he said.

Dr. Fava also made the point that this study was of very short design, compared with other SPCD trials. “People were skeptical that you would see a reduction in placebo with only 4 days of treatment in two stages,” he said. However, “The design worked,” he said, since the reduction in depression scores was the equivalent of just 1.6 points on the HAMD-17 in the second stage of the study after the placebo responders had been eliminated. “That’s a very low placebo rate,” Dr. Fava said.

Many experimental building blocks support the use of LFMS to treat depression. Investigations began after a serendipitous 2004 discovery that patients with bipolar disorder who underwent diagnostic echo-planar magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (EP-MRSI) experienced relief from depressive symptoms after the scan (Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;161[1]:93-8). Since then, LFMS has been shown to reduce helpless behavior in mice during a forced swim test.

In humans, FDG-PET imaging studies also have shown perceptible physiological changes when individuals with depression receive LFMS, consistent with those seen in reduced depression. Patients in two earlier proof-of-concept studies who had either bipolar or unipolar depression and who received LFMS experienced significantly greater symptom relief than did those receiving sham treatment.

Study design limitations included the relatively small sample size and potential recruitment biases for those seeking this form of augmentation for depression treatment. The study included only patients with unipolar depression, although “two previous positive studies included 81 bipolar patients and 22 unipolar patients,” Dr. Fava said.

Potential technical limitations included the low dosing of LFMS, with just 20 minutes of exposure two times; however, Dr. Fava said, the duration was chosen to parallel the previous studies done in patients with bipolar disorder. Also, seeing a detectable change in depression scoring at 48-72 hours after LFMS might not be an entirely realistic expectation.

The National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Fava reported having a patent for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), which is licensed by Massachusetts General Hospital to RCT Logic, LLC. He also reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

On Twitter @karioakes

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A small proof-of-concept study of low-field magnetic stimulation to augment medical treatment for 85 individuals with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder failed to meet its primary endpoint of significant improvement in core depression symptoms at 48 hours after treatment, though some nonsignificant improvement in mood was seen, compared with sham treatment.

The study’s design did succeed, however, in reducing the substantial placebo response that plagues many clinical trials of treatments for psychiatric illness.

During a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting, Dr. Maurizio Fava shared the results of a double-blind, proof-of-concept trial of low-field magnetic stimulation (LFMS) augmentation of antidepressant therapy for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Overall, patients receiving LFMS saw no significant improvement on an abbreviated 6-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-6), compared with those receiving sham treatment (P = .61). Since the study looked at changes in depression scores just 24 hours after treatment, Dr. Fava said, “We used the HAMD-6, because it’s a more sensitive measure for rapid changes than the HAMD-17.

“Unfortunately, the LFMS did not separate out after 48 hours,” he said.

Nonsignificant differences also were seen for two other rating scales, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The use of a visual analog scale to detect mood changes 120 minutes after treatment did not yield significant differences between those receiving LFMS and those receiving sham.

Many avenues in addition to medication are being explored to provide rapid relief for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), said Dr. Fava, the study’s lead investigator, associate dean for clinical and translational research, and Slater Family Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The six-site Rapidly-Acting Treatments for Treatment-Resistant Depression trial was sham controlled and used a prerandomized sequential parallel comparison design (SPCD). The intervention of LFMS or sham was delivered for 20 minutes daily on 2 consecutive days, and then again for 2 more days after an interim assessment.

“In the second stage of the study, only the patients who had not responded to sham are included,” Dr. Fava said. This is the aspect of an SPCD study that can help to reduce the negative effect on results that can be seen with high placebo response rates, a common phenomenon in psychiatric clinical trials.

“This was a complicated study, involving all kind of methodologic approaches,” said Dr. Fava, noting that each enrollee had the diagnosis of moderate to severe depression (MADRS score equal to or greater than 20) confirmed by two interviewers, including one remote interviewer who was not involved in the study.

Patients who were on a stable dose of antidepressant were included “if they failed to achieve a treatment response after no more than one, but not more than three, treatment courses of antidepressant therapy of at least 8 weeks’ duration,” Dr. Fava said. “We wanted to avoid ‘super-resistance,’ which can reduce the ability to detect a signal” for efficacy, he said.

Dr. Fava also made the point that this study was of very short design, compared with other SPCD trials. “People were skeptical that you would see a reduction in placebo with only 4 days of treatment in two stages,” he said. However, “The design worked,” he said, since the reduction in depression scores was the equivalent of just 1.6 points on the HAMD-17 in the second stage of the study after the placebo responders had been eliminated. “That’s a very low placebo rate,” Dr. Fava said.

Many experimental building blocks support the use of LFMS to treat depression. Investigations began after a serendipitous 2004 discovery that patients with bipolar disorder who underwent diagnostic echo-planar magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (EP-MRSI) experienced relief from depressive symptoms after the scan (Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;161[1]:93-8). Since then, LFMS has been shown to reduce helpless behavior in mice during a forced swim test.

In humans, FDG-PET imaging studies also have shown perceptible physiological changes when individuals with depression receive LFMS, consistent with those seen in reduced depression. Patients in two earlier proof-of-concept studies who had either bipolar or unipolar depression and who received LFMS experienced significantly greater symptom relief than did those receiving sham treatment.

Study design limitations included the relatively small sample size and potential recruitment biases for those seeking this form of augmentation for depression treatment. The study included only patients with unipolar depression, although “two previous positive studies included 81 bipolar patients and 22 unipolar patients,” Dr. Fava said.

Potential technical limitations included the low dosing of LFMS, with just 20 minutes of exposure two times; however, Dr. Fava said, the duration was chosen to parallel the previous studies done in patients with bipolar disorder. Also, seeing a detectable change in depression scoring at 48-72 hours after LFMS might not be an entirely realistic expectation.

The National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Fava reported having a patent for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), which is licensed by Massachusetts General Hospital to RCT Logic, LLC. He also reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

On Twitter @karioakes

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A small proof-of-concept study of low-field magnetic stimulation to augment medical treatment for 85 individuals with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder failed to meet its primary endpoint of significant improvement in core depression symptoms at 48 hours after treatment, though some nonsignificant improvement in mood was seen, compared with sham treatment.

The study’s design did succeed, however, in reducing the substantial placebo response that plagues many clinical trials of treatments for psychiatric illness.

During a meeting of the American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, formerly known as the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit meeting, Dr. Maurizio Fava shared the results of a double-blind, proof-of-concept trial of low-field magnetic stimulation (LFMS) augmentation of antidepressant therapy for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

Overall, patients receiving LFMS saw no significant improvement on an abbreviated 6-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-6), compared with those receiving sham treatment (P = .61). Since the study looked at changes in depression scores just 24 hours after treatment, Dr. Fava said, “We used the HAMD-6, because it’s a more sensitive measure for rapid changes than the HAMD-17.

“Unfortunately, the LFMS did not separate out after 48 hours,” he said.

Nonsignificant differences also were seen for two other rating scales, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The use of a visual analog scale to detect mood changes 120 minutes after treatment did not yield significant differences between those receiving LFMS and those receiving sham.

Many avenues in addition to medication are being explored to provide rapid relief for individuals with treatment-resistant depression (TRD), said Dr. Fava, the study’s lead investigator, associate dean for clinical and translational research, and Slater Family Professor of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The six-site Rapidly-Acting Treatments for Treatment-Resistant Depression trial was sham controlled and used a prerandomized sequential parallel comparison design (SPCD). The intervention of LFMS or sham was delivered for 20 minutes daily on 2 consecutive days, and then again for 2 more days after an interim assessment.

“In the second stage of the study, only the patients who had not responded to sham are included,” Dr. Fava said. This is the aspect of an SPCD study that can help to reduce the negative effect on results that can be seen with high placebo response rates, a common phenomenon in psychiatric clinical trials.

“This was a complicated study, involving all kind of methodologic approaches,” said Dr. Fava, noting that each enrollee had the diagnosis of moderate to severe depression (MADRS score equal to or greater than 20) confirmed by two interviewers, including one remote interviewer who was not involved in the study.

Patients who were on a stable dose of antidepressant were included “if they failed to achieve a treatment response after no more than one, but not more than three, treatment courses of antidepressant therapy of at least 8 weeks’ duration,” Dr. Fava said. “We wanted to avoid ‘super-resistance,’ which can reduce the ability to detect a signal” for efficacy, he said.

Dr. Fava also made the point that this study was of very short design, compared with other SPCD trials. “People were skeptical that you would see a reduction in placebo with only 4 days of treatment in two stages,” he said. However, “The design worked,” he said, since the reduction in depression scores was the equivalent of just 1.6 points on the HAMD-17 in the second stage of the study after the placebo responders had been eliminated. “That’s a very low placebo rate,” Dr. Fava said.

Many experimental building blocks support the use of LFMS to treat depression. Investigations began after a serendipitous 2004 discovery that patients with bipolar disorder who underwent diagnostic echo-planar magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (EP-MRSI) experienced relief from depressive symptoms after the scan (Am J Psychiatry. 2004 Jan;161[1]:93-8). Since then, LFMS has been shown to reduce helpless behavior in mice during a forced swim test.

In humans, FDG-PET imaging studies also have shown perceptible physiological changes when individuals with depression receive LFMS, consistent with those seen in reduced depression. Patients in two earlier proof-of-concept studies who had either bipolar or unipolar depression and who received LFMS experienced significantly greater symptom relief than did those receiving sham treatment.

Study design limitations included the relatively small sample size and potential recruitment biases for those seeking this form of augmentation for depression treatment. The study included only patients with unipolar depression, although “two previous positive studies included 81 bipolar patients and 22 unipolar patients,” Dr. Fava said.

Potential technical limitations included the low dosing of LFMS, with just 20 minutes of exposure two times; however, Dr. Fava said, the duration was chosen to parallel the previous studies done in patients with bipolar disorder. Also, seeing a detectable change in depression scoring at 48-72 hours after LFMS might not be an entirely realistic expectation.

The National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Fava reported having a patent for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), which is licensed by Massachusetts General Hospital to RCT Logic, LLC. He also reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE ASCP ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Low-field magnetic stimulation (LFMS) was no better than sham in improving treatment-resistant depression.

Major finding: In a pilot study of 85 individuals with treatment-resistant depression, the abbreviated Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores were no better for those receiving LFMS compared with sham (P = .61).

Data source: Randomized double-blind sham-controlled sequential parallel comparison designed study of 85 individuals with moderate to severe treatment-resistant depression.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health and the Department of Health and Human Services funded the study. Dr. Fava reported having a patent for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), which is licensed by Massachusetts General Hospital to RCT Logic, LLC. He also reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

Billing for family meetings

Family meetings are never easy.

They’re difficult, and often held to discuss the case of a demented patient. In these situations, the family doesn’t want the patient to hear their concerns or is afraid they’ll be embarrassed or angry. Sometimes getting the patient to the appointment is simply too difficult.

Of course, most discussions of this type can be done by phone ... in theory. In practice, it doesn’t work that way.

It’s the subject matter that makes the impersonal nature of the phone difficult. Families have hard questions and want real answers at these times. A face-to-face meeting, with the human interaction, is often the best way to get things across clearly and still with compassion. It avoids the problem of the phone being passed around, having to repeat yourself to each person, and wondering who just asked what. Very few families, in my experience, want to do this on the phone.

These meetings are never quick, either. Depending on family and circumstances, they can take 30-60 minutes. Getting an insurance company to pay for that time is near impossible. Most plans only want to pay for visits where the patient is actually present, when in these cases the family is trying to avoid that. While there is a Medicare payment code for “advance care planning,” it doesn’t cover treatment discussions or other neurological issues they may bring up, and many patients are on non-Medicare plans.

I bill people for these times and have found that most families are willing to pay. I’m not fond of doing so, and certainly not trying to get rich off of them. But it’s still time that I’m in my office and have to pay my rent, staff, and utilities.

Part of this job – a big part – is helping patients and their loved ones understand and deal with difficult situations. Realistically, this is the best way to do it. Families understand that as well as I do.

Why won’t insurance companies cover them? I suppose their excuse is that they cover the patient, not the questions or emotional needs of their caregivers. Of course, those things are as important to the care of the patient as any treatment, but the bean counters don’t want to pay for them.

That is unfortunate, because someone has to. Good medical care depends on good communication with all involved.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Family meetings are never easy.

They’re difficult, and often held to discuss the case of a demented patient. In these situations, the family doesn’t want the patient to hear their concerns or is afraid they’ll be embarrassed or angry. Sometimes getting the patient to the appointment is simply too difficult.

Of course, most discussions of this type can be done by phone ... in theory. In practice, it doesn’t work that way.

It’s the subject matter that makes the impersonal nature of the phone difficult. Families have hard questions and want real answers at these times. A face-to-face meeting, with the human interaction, is often the best way to get things across clearly and still with compassion. It avoids the problem of the phone being passed around, having to repeat yourself to each person, and wondering who just asked what. Very few families, in my experience, want to do this on the phone.

These meetings are never quick, either. Depending on family and circumstances, they can take 30-60 minutes. Getting an insurance company to pay for that time is near impossible. Most plans only want to pay for visits where the patient is actually present, when in these cases the family is trying to avoid that. While there is a Medicare payment code for “advance care planning,” it doesn’t cover treatment discussions or other neurological issues they may bring up, and many patients are on non-Medicare plans.

I bill people for these times and have found that most families are willing to pay. I’m not fond of doing so, and certainly not trying to get rich off of them. But it’s still time that I’m in my office and have to pay my rent, staff, and utilities.

Part of this job – a big part – is helping patients and their loved ones understand and deal with difficult situations. Realistically, this is the best way to do it. Families understand that as well as I do.

Why won’t insurance companies cover them? I suppose their excuse is that they cover the patient, not the questions or emotional needs of their caregivers. Of course, those things are as important to the care of the patient as any treatment, but the bean counters don’t want to pay for them.

That is unfortunate, because someone has to. Good medical care depends on good communication with all involved.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Family meetings are never easy.

They’re difficult, and often held to discuss the case of a demented patient. In these situations, the family doesn’t want the patient to hear their concerns or is afraid they’ll be embarrassed or angry. Sometimes getting the patient to the appointment is simply too difficult.

Of course, most discussions of this type can be done by phone ... in theory. In practice, it doesn’t work that way.

It’s the subject matter that makes the impersonal nature of the phone difficult. Families have hard questions and want real answers at these times. A face-to-face meeting, with the human interaction, is often the best way to get things across clearly and still with compassion. It avoids the problem of the phone being passed around, having to repeat yourself to each person, and wondering who just asked what. Very few families, in my experience, want to do this on the phone.

These meetings are never quick, either. Depending on family and circumstances, they can take 30-60 minutes. Getting an insurance company to pay for that time is near impossible. Most plans only want to pay for visits where the patient is actually present, when in these cases the family is trying to avoid that. While there is a Medicare payment code for “advance care planning,” it doesn’t cover treatment discussions or other neurological issues they may bring up, and many patients are on non-Medicare plans.

I bill people for these times and have found that most families are willing to pay. I’m not fond of doing so, and certainly not trying to get rich off of them. But it’s still time that I’m in my office and have to pay my rent, staff, and utilities.

Part of this job – a big part – is helping patients and their loved ones understand and deal with difficult situations. Realistically, this is the best way to do it. Families understand that as well as I do.

Why won’t insurance companies cover them? I suppose their excuse is that they cover the patient, not the questions or emotional needs of their caregivers. Of course, those things are as important to the care of the patient as any treatment, but the bean counters don’t want to pay for them.

That is unfortunate, because someone has to. Good medical care depends on good communication with all involved.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Jack Gladstein, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Tips for collaborations among GI investigators, industry, FDA

SAN DIEGO – Tensions among academic investigators, industry sponsors, and the Food and Drug Administration can hinder new drug approvals and slow or block communication of important results, experts said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Relationships between investigators and industry have become especially strained, according to Dr. M. Scott Harris, cofounder of Lyric Pharmaceuticals in San Francisco. “I can tell you as a former investigator, and someone who speaks to investigators all the time, they feel disenfranchised,” he said.

Several steps can help. Industry should focus on empowering investigators, “not study sites,” said Dr. Harris. “Have protocol development meetings, not investigator meetings. Have open dialogue so that investigators can share in the excitement of the study, the results, and the science.”

Intellectual property is a particularly hot topic, acknowledged Dr. Harris, who started out in academic gastroenterology before making the jump to working for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. “Intellectual property is the lifeblood of a company – the only thing that generates the likelihood of a return on investment,” he emphasized. “Please do not push back if some information cannot be shared with you.” But within those constraints, industry should “force itself to be as patient as possible,” he said. “A balance has to be struck between the need for IP [intellectual property] and the need to share knowledge.”

Sharing knowledge also means that industry sponsors need to commit to a clear publication strategy, said Dr. Harris. “Investigators want the results of the studies to be communicated, including reasons for failure. We have failed at this as an industry, and this is not acceptable.”

But academic investigators need to make some changes, too. Successfully joining a trial means engaging actively with the sponsor and protocol, Dr. Harris emphasized. “Don’t tell your staff you’re too busy to talk to me when I call. Focus on ethical study conduct, good clinical practice, training, data quality, and meeting timelines.”

Dr. Gary Lichtenstein agreed. A gastroenterologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, with more than 30 years of experience in clinical trials, he knows that successful academic study sites have “efficient and businesslike operations,” a proven internal audit system, and solid, reasonable budgeting for staff time, overhead, equipment, and storage. In particular, academic investigators should double-check training requirements, the qualifications of the study coordinator, and who will handle regulatory, legal, and budgeting concerns, he said.

Vetting a potential industry sponsor is just as important. Ask “if they have the staff, time, equipment, and space to do the study,” Dr. Lichtenstein stressed. “Communicate expectations in writing back and forth to avoid misunderstandings. An indemnification clause is also very important to hold the consultant harmless from and against any claim, loss, or damage whatsoever.”

The FDA, for its part, needs to respond faster to meeting requests and offer clearer guidance about appropriate study designs and outcome measures, both experts emphasized. The median time for FDA to approve a drug application is about 180 days, while approving new gastroenterology agents takes nearly twice as long, according to Dr. Lichtenstein. “There is clearly a discrepancy, and it would be nice if we moved the bar closer. As an investigator, I need to know which trials are acceptable in design, and what endpoints are clearly defined, with examples,” he said. “If I have a question, I need a point of contact to call to get an answer in rapid time, instead of having to wait for months, and I need to know which biomarkers are appropriate to use.”

Dr. Harris agreed. “There should be tension between FDA and industry – that is part of the process,” he said. “But open communication and rapid response to meeting requests are crucial.”

Timeliness and transparency are especially important as FDA transitions “from being a classic regulator to a proactive partner in drug development,” Dr. Harris said. “What industry needs and expects from FDA is greater certainty on the path. Companies may or may not like a particular FDA guidance document, but they greatly appreciate the clarity that guidance documents provide.”

Dr. Lichtenstein disclosed ties to AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Harris is employed by Lyric Pharmaceuticals and disclosed relationships with several other biopharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – Tensions among academic investigators, industry sponsors, and the Food and Drug Administration can hinder new drug approvals and slow or block communication of important results, experts said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Relationships between investigators and industry have become especially strained, according to Dr. M. Scott Harris, cofounder of Lyric Pharmaceuticals in San Francisco. “I can tell you as a former investigator, and someone who speaks to investigators all the time, they feel disenfranchised,” he said.

Several steps can help. Industry should focus on empowering investigators, “not study sites,” said Dr. Harris. “Have protocol development meetings, not investigator meetings. Have open dialogue so that investigators can share in the excitement of the study, the results, and the science.”

Intellectual property is a particularly hot topic, acknowledged Dr. Harris, who started out in academic gastroenterology before making the jump to working for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. “Intellectual property is the lifeblood of a company – the only thing that generates the likelihood of a return on investment,” he emphasized. “Please do not push back if some information cannot be shared with you.” But within those constraints, industry should “force itself to be as patient as possible,” he said. “A balance has to be struck between the need for IP [intellectual property] and the need to share knowledge.”

Sharing knowledge also means that industry sponsors need to commit to a clear publication strategy, said Dr. Harris. “Investigators want the results of the studies to be communicated, including reasons for failure. We have failed at this as an industry, and this is not acceptable.”

But academic investigators need to make some changes, too. Successfully joining a trial means engaging actively with the sponsor and protocol, Dr. Harris emphasized. “Don’t tell your staff you’re too busy to talk to me when I call. Focus on ethical study conduct, good clinical practice, training, data quality, and meeting timelines.”

Dr. Gary Lichtenstein agreed. A gastroenterologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, with more than 30 years of experience in clinical trials, he knows that successful academic study sites have “efficient and businesslike operations,” a proven internal audit system, and solid, reasonable budgeting for staff time, overhead, equipment, and storage. In particular, academic investigators should double-check training requirements, the qualifications of the study coordinator, and who will handle regulatory, legal, and budgeting concerns, he said.

Vetting a potential industry sponsor is just as important. Ask “if they have the staff, time, equipment, and space to do the study,” Dr. Lichtenstein stressed. “Communicate expectations in writing back and forth to avoid misunderstandings. An indemnification clause is also very important to hold the consultant harmless from and against any claim, loss, or damage whatsoever.”

The FDA, for its part, needs to respond faster to meeting requests and offer clearer guidance about appropriate study designs and outcome measures, both experts emphasized. The median time for FDA to approve a drug application is about 180 days, while approving new gastroenterology agents takes nearly twice as long, according to Dr. Lichtenstein. “There is clearly a discrepancy, and it would be nice if we moved the bar closer. As an investigator, I need to know which trials are acceptable in design, and what endpoints are clearly defined, with examples,” he said. “If I have a question, I need a point of contact to call to get an answer in rapid time, instead of having to wait for months, and I need to know which biomarkers are appropriate to use.”

Dr. Harris agreed. “There should be tension between FDA and industry – that is part of the process,” he said. “But open communication and rapid response to meeting requests are crucial.”

Timeliness and transparency are especially important as FDA transitions “from being a classic regulator to a proactive partner in drug development,” Dr. Harris said. “What industry needs and expects from FDA is greater certainty on the path. Companies may or may not like a particular FDA guidance document, but they greatly appreciate the clarity that guidance documents provide.”

Dr. Lichtenstein disclosed ties to AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Harris is employed by Lyric Pharmaceuticals and disclosed relationships with several other biopharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO – Tensions among academic investigators, industry sponsors, and the Food and Drug Administration can hinder new drug approvals and slow or block communication of important results, experts said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Relationships between investigators and industry have become especially strained, according to Dr. M. Scott Harris, cofounder of Lyric Pharmaceuticals in San Francisco. “I can tell you as a former investigator, and someone who speaks to investigators all the time, they feel disenfranchised,” he said.

Several steps can help. Industry should focus on empowering investigators, “not study sites,” said Dr. Harris. “Have protocol development meetings, not investigator meetings. Have open dialogue so that investigators can share in the excitement of the study, the results, and the science.”

Intellectual property is a particularly hot topic, acknowledged Dr. Harris, who started out in academic gastroenterology before making the jump to working for pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. “Intellectual property is the lifeblood of a company – the only thing that generates the likelihood of a return on investment,” he emphasized. “Please do not push back if some information cannot be shared with you.” But within those constraints, industry should “force itself to be as patient as possible,” he said. “A balance has to be struck between the need for IP [intellectual property] and the need to share knowledge.”

Sharing knowledge also means that industry sponsors need to commit to a clear publication strategy, said Dr. Harris. “Investigators want the results of the studies to be communicated, including reasons for failure. We have failed at this as an industry, and this is not acceptable.”

But academic investigators need to make some changes, too. Successfully joining a trial means engaging actively with the sponsor and protocol, Dr. Harris emphasized. “Don’t tell your staff you’re too busy to talk to me when I call. Focus on ethical study conduct, good clinical practice, training, data quality, and meeting timelines.”

Dr. Gary Lichtenstein agreed. A gastroenterologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, with more than 30 years of experience in clinical trials, he knows that successful academic study sites have “efficient and businesslike operations,” a proven internal audit system, and solid, reasonable budgeting for staff time, overhead, equipment, and storage. In particular, academic investigators should double-check training requirements, the qualifications of the study coordinator, and who will handle regulatory, legal, and budgeting concerns, he said.

Vetting a potential industry sponsor is just as important. Ask “if they have the staff, time, equipment, and space to do the study,” Dr. Lichtenstein stressed. “Communicate expectations in writing back and forth to avoid misunderstandings. An indemnification clause is also very important to hold the consultant harmless from and against any claim, loss, or damage whatsoever.”

The FDA, for its part, needs to respond faster to meeting requests and offer clearer guidance about appropriate study designs and outcome measures, both experts emphasized. The median time for FDA to approve a drug application is about 180 days, while approving new gastroenterology agents takes nearly twice as long, according to Dr. Lichtenstein. “There is clearly a discrepancy, and it would be nice if we moved the bar closer. As an investigator, I need to know which trials are acceptable in design, and what endpoints are clearly defined, with examples,” he said. “If I have a question, I need a point of contact to call to get an answer in rapid time, instead of having to wait for months, and I need to know which biomarkers are appropriate to use.”

Dr. Harris agreed. “There should be tension between FDA and industry – that is part of the process,” he said. “But open communication and rapid response to meeting requests are crucial.”

Timeliness and transparency are especially important as FDA transitions “from being a classic regulator to a proactive partner in drug development,” Dr. Harris said. “What industry needs and expects from FDA is greater certainty on the path. Companies may or may not like a particular FDA guidance document, but they greatly appreciate the clarity that guidance documents provide.”

Dr. Lichtenstein disclosed ties to AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, and numerous other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Harris is employed by Lyric Pharmaceuticals and disclosed relationships with several other biopharmaceutical companies.

AT DDW® 2016

Three U.S. infants born with birth defects linked to Zika virus

There have been three infants born with birth defects and three pregnancy losses as a result of likely maternal Zika virus infection among U.S. women, according to figures released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The figures, posted by the CDC on June 16, reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry as of June 9. This is not real-time data and reflects only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, though it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. The numbers also do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The current numbers include outcomes reported in U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The CDC will begin reporting outcomes in U.S. territories in the coming weeks.

CDC officials plan to update the pregnancy outcome data every Thursday at http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregnancy-outcomes.html.

On Twitter @maryellenny

There have been three infants born with birth defects and three pregnancy losses as a result of likely maternal Zika virus infection among U.S. women, according to figures released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The figures, posted by the CDC on June 16, reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry as of June 9. This is not real-time data and reflects only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, though it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. The numbers also do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The current numbers include outcomes reported in U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The CDC will begin reporting outcomes in U.S. territories in the coming weeks.

CDC officials plan to update the pregnancy outcome data every Thursday at http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregnancy-outcomes.html.

On Twitter @maryellenny

There have been three infants born with birth defects and three pregnancy losses as a result of likely maternal Zika virus infection among U.S. women, according to figures released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The figures, posted by the CDC on June 16, reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry as of June 9. This is not real-time data and reflects only pregnancy outcomes for women with any laboratory evidence of possible Zika virus infection, though it is not known if Zika virus was the cause of the poor outcomes. The numbers also do not reflect outcomes among ongoing pregnancies.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

The current numbers include outcomes reported in U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The CDC will begin reporting outcomes in U.S. territories in the coming weeks.

CDC officials plan to update the pregnancy outcome data every Thursday at http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/pregnancy-outcomes.html.

On Twitter @maryellenny

‘Impressive’ responses with nivolumab in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma

COPENHAGEN – Nivolumab may be an effective salvage therapy option for adults with Hodgkin lymphoma whose disease has progressed despite transplant and treatment with brentuximab vedotin, investigators reported.

In a subcohort of patients from the Checkmate 205 phase II trial, 80 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who had disease progression following autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) and brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris), nivolumab (Opdivo) therapy was associated with a 53% objective response rate according to independent reviewers, reported Dr. Anas Younes, chief of the lymphoma service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“The PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab is an important new treatment to address unmet needs in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma with progressive disease and limited treatment options, especially after autologous transplant,” he said at a briefing at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Objective response rates as determined by both investigators and independent reviewers were “impressive,” and had “encouraging durability,” he added. The median duration of response at time of data cutoff was 7.8 months, and the majority of patients had ongoing responses at the time of the analysis, Dr. Younes said.

Nivolumab was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or progressed after ASCT followed by brentuximab vedotin.

In the Checkmate 205 registrational trial, 80 patients (median age 37, range 18-72 years) were assigned to receive nivolumab 3 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks. Patients were evaluated for response by both an independent radiologic review committee (IRRC) and investigators, using 2007 International Working Group response criteria. After a median follow-up of 8.9 months, the IRRC-rated objective response rate, the primary endpoint, was 66%, including 8.8% complete remissions (CR), and 57.5% partial remissions (PR).

Dr. Younes showed a waterfall plot indicating that nearly all patients had some degree of tumor regression, and all but one patient among the responders had tumor reductions of 50% or greater from baseline.

Among 43 patients who had had no response to brentuximab vedotin, subsequent treatment with nivolumab was associated with an IRRC-rated objective response rate of 72%. As noted, the median duration of response was 7.8 months, and the median time to response was 2.1 months.

As of the last follow-up, 33 of the 53 patients with IRRC-rated responses had retained response. The IRRC-determined 6-month progression-free survival rate was 77%, and the overall survival rate was 99%.

In all, 72 patients (90%) had a treatment-related adverse event. The most common events occurring in 15% or more of patients were fatigue, infusion-related reactions, and rash. Most of the immune-mediated adverse events were of low grade and manageable, and there were no treatment-related deaths, Dr. Younes said.

Briefing moderator Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam, who was not involved in the study, asked whether nivolumab can be considered as a bridge to other therapies in this population.

Dr. Younes said that the “natural progression of a single-agent therapy that has efficacy is to combine it with other active agents, or use maybe in the adjuvant or maintenance setting in certain circumstances.”

“I don’t expect single-agent nivolumab to cure our patients,” he added.

A similarly designed clinical trial, MK-3457-087/KEYNOTE-087, is exploring the use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda). This trial is ongoing but does not have published data as yet.

Checkmate 205 is sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Younes has served as a consultant/advisor, received honoraria and/or research funding from Gilead Sciences, Curis, Incyte, Janssen, Seattle Genetics, Novartis, Celgene, Millennium, and Sanofi. Dr. Hagenbeek reported no relevant disclosures.

COPENHAGEN – Nivolumab may be an effective salvage therapy option for adults with Hodgkin lymphoma whose disease has progressed despite transplant and treatment with brentuximab vedotin, investigators reported.

In a subcohort of patients from the Checkmate 205 phase II trial, 80 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who had disease progression following autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) and brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris), nivolumab (Opdivo) therapy was associated with a 53% objective response rate according to independent reviewers, reported Dr. Anas Younes, chief of the lymphoma service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“The PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab is an important new treatment to address unmet needs in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma with progressive disease and limited treatment options, especially after autologous transplant,” he said at a briefing at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Objective response rates as determined by both investigators and independent reviewers were “impressive,” and had “encouraging durability,” he added. The median duration of response at time of data cutoff was 7.8 months, and the majority of patients had ongoing responses at the time of the analysis, Dr. Younes said.

Nivolumab was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or progressed after ASCT followed by brentuximab vedotin.

In the Checkmate 205 registrational trial, 80 patients (median age 37, range 18-72 years) were assigned to receive nivolumab 3 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks. Patients were evaluated for response by both an independent radiologic review committee (IRRC) and investigators, using 2007 International Working Group response criteria. After a median follow-up of 8.9 months, the IRRC-rated objective response rate, the primary endpoint, was 66%, including 8.8% complete remissions (CR), and 57.5% partial remissions (PR).

Dr. Younes showed a waterfall plot indicating that nearly all patients had some degree of tumor regression, and all but one patient among the responders had tumor reductions of 50% or greater from baseline.

Among 43 patients who had had no response to brentuximab vedotin, subsequent treatment with nivolumab was associated with an IRRC-rated objective response rate of 72%. As noted, the median duration of response was 7.8 months, and the median time to response was 2.1 months.

As of the last follow-up, 33 of the 53 patients with IRRC-rated responses had retained response. The IRRC-determined 6-month progression-free survival rate was 77%, and the overall survival rate was 99%.

In all, 72 patients (90%) had a treatment-related adverse event. The most common events occurring in 15% or more of patients were fatigue, infusion-related reactions, and rash. Most of the immune-mediated adverse events were of low grade and manageable, and there were no treatment-related deaths, Dr. Younes said.

Briefing moderator Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam, who was not involved in the study, asked whether nivolumab can be considered as a bridge to other therapies in this population.

Dr. Younes said that the “natural progression of a single-agent therapy that has efficacy is to combine it with other active agents, or use maybe in the adjuvant or maintenance setting in certain circumstances.”

“I don’t expect single-agent nivolumab to cure our patients,” he added.

A similarly designed clinical trial, MK-3457-087/KEYNOTE-087, is exploring the use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda). This trial is ongoing but does not have published data as yet.

Checkmate 205 is sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Younes has served as a consultant/advisor, received honoraria and/or research funding from Gilead Sciences, Curis, Incyte, Janssen, Seattle Genetics, Novartis, Celgene, Millennium, and Sanofi. Dr. Hagenbeek reported no relevant disclosures.

COPENHAGEN – Nivolumab may be an effective salvage therapy option for adults with Hodgkin lymphoma whose disease has progressed despite transplant and treatment with brentuximab vedotin, investigators reported.

In a subcohort of patients from the Checkmate 205 phase II trial, 80 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma who had disease progression following autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) and brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris), nivolumab (Opdivo) therapy was associated with a 53% objective response rate according to independent reviewers, reported Dr. Anas Younes, chief of the lymphoma service at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“The PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab is an important new treatment to address unmet needs in patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma with progressive disease and limited treatment options, especially after autologous transplant,” he said at a briefing at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

Objective response rates as determined by both investigators and independent reviewers were “impressive,” and had “encouraging durability,” he added. The median duration of response at time of data cutoff was 7.8 months, and the majority of patients had ongoing responses at the time of the analysis, Dr. Younes said.

Nivolumab was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of classical Hodgkin lymphoma that has relapsed or progressed after ASCT followed by brentuximab vedotin.

In the Checkmate 205 registrational trial, 80 patients (median age 37, range 18-72 years) were assigned to receive nivolumab 3 mg/kg intravenously every 2 weeks. Patients were evaluated for response by both an independent radiologic review committee (IRRC) and investigators, using 2007 International Working Group response criteria. After a median follow-up of 8.9 months, the IRRC-rated objective response rate, the primary endpoint, was 66%, including 8.8% complete remissions (CR), and 57.5% partial remissions (PR).

Dr. Younes showed a waterfall plot indicating that nearly all patients had some degree of tumor regression, and all but one patient among the responders had tumor reductions of 50% or greater from baseline.

Among 43 patients who had had no response to brentuximab vedotin, subsequent treatment with nivolumab was associated with an IRRC-rated objective response rate of 72%. As noted, the median duration of response was 7.8 months, and the median time to response was 2.1 months.

As of the last follow-up, 33 of the 53 patients with IRRC-rated responses had retained response. The IRRC-determined 6-month progression-free survival rate was 77%, and the overall survival rate was 99%.

In all, 72 patients (90%) had a treatment-related adverse event. The most common events occurring in 15% or more of patients were fatigue, infusion-related reactions, and rash. Most of the immune-mediated adverse events were of low grade and manageable, and there were no treatment-related deaths, Dr. Younes said.

Briefing moderator Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam, who was not involved in the study, asked whether nivolumab can be considered as a bridge to other therapies in this population.

Dr. Younes said that the “natural progression of a single-agent therapy that has efficacy is to combine it with other active agents, or use maybe in the adjuvant or maintenance setting in certain circumstances.”

“I don’t expect single-agent nivolumab to cure our patients,” he added.

A similarly designed clinical trial, MK-3457-087/KEYNOTE-087, is exploring the use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda). This trial is ongoing but does not have published data as yet.

Checkmate 205 is sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Younes has served as a consultant/advisor, received honoraria and/or research funding from Gilead Sciences, Curis, Incyte, Janssen, Seattle Genetics, Novartis, Celgene, Millennium, and Sanofi. Dr. Hagenbeek reported no relevant disclosures.

AT THE EHA CONGRESS

Key clinical point:. Nivolumab may be an effective salvage therapy option for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma that has progressed after transplant and brentuximab vedotin therapy.

Major finding: The independent radiologic review committee–rated objective response rate was 53%.

Data source: Registration trial of nivolumab in 80 patients with Hodgkin lymphoma relapsed/refractory after autologous stem cell transplant and brentuximab vedotin.

Disclosures: Checkmate 205 is sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Younes has served as a consultant/advisor, received honoraria and/or research funding from Gilead Sciences, Curis, Incyte, Janssen, Seattle Genetics, Novartis, Celgene, Millennium, and Sanofi. Dr. Hagenbeek reported no relevant disclosures.

VIDEO: Romosozumab bested teriparatide in hip BMD transitioning from bisphosphonates

LONDON – Bone mineral density (BMD) and estimated bone strength in the hip significantly increased during 1 year of treatment with the investigational monoclonal antibody romosozumab in comparison with teriparatide in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis who had previous fracture history and had been taking bisphosphonates for at least the previous 3 years in an open-label, randomized trial.

The investigators in the phase III, international, multicenter STRUCTURE trial sought to compare the monoclonal anti-sclerostin antibody romosozumab, which works dually to increase bone formation and decrease bone resorption, against the bone-forming agent teriparatide (Forteo) to see if it would increase total hip bone mineral density to a significantly greater extent by 12 months. Teriparatide is known to take longer to build bone at the hip following bisphosphonate use.

“These results in our minds suggest that romosozumab may offer a unique benefit to patients at high risk for fracture, transitioning from bisphosphonates,” first author Bente L. Langdahl, Ph.D., of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital said at the European Congress of Rheumatology. She discussed the study results in this video interview.

When Dr. Langdahl was asked after her presentation about the foreseen role of the drug in clinical practice, she noted that ongoing phase III trials looking at fracture endpoints should indicate whether it works faster at preventing fractures. Because there does not seem to be a restriction to the repeated use of romosozumab, she suggested it might be given initially for 12 months to build bone, followed by bisphosphonates to stabilize gains made, and then it could be used again if needed in a treat-to-target fashion.

The trial randomized 436 patients to receive either subcutaneous romosozumab 210 mg once monthly or subcutaneous teriparatide 20 mcg once daily for 12 months. All patients received a loading dose of 50,000-60,000 IU vitamin D3 to make sure they were vitamin D replete. The patients were postmenopausal, aged 55-90 years, and required to have taken oral bisphosphonate therapy at a dose equivalent to 70 mg weekly of alendronate for at least 3 years before enrollment (with at least 1 year of alendronate therapy prior to enrollment). They had a T score of –2.5 or less in total hip, lumbar spine, or femoral neck BMD and a history of a nonvertebral fracture after 50 years of age or a vertebral fracture at any age.

At 12 months, the primary endpoint of total hip BMD percentage change from baseline, which was calculated by averaging dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measurements at 6 and 12 months, increased significantly by 2.6% in the romosozumab group, compared with a loss of –1.6% in the teriparatide group.

“Why did we choose this rather unusual endpoint? It’s because we wanted to capture what happened throughout the first year,” Dr. Langdahl said.

The respective changes from baseline total hip BMD at month 12 were 2.9% vs. –0.5%; in the femoral neck, the 12-month change was 3.2% vs. –0.2%; and in the lumbar spine, the change was 9.8% vs. 5.4%.

The trial participants had a mean age of about 71 years, and T scores ranging from –2.87 to –2.83 in the lumbar spine, –2.27 to –2.21 in total hip, and –2.49 to –2.43 in the femoral neck.