User login

Increased demand drives up psychiatrists’ starting salaries

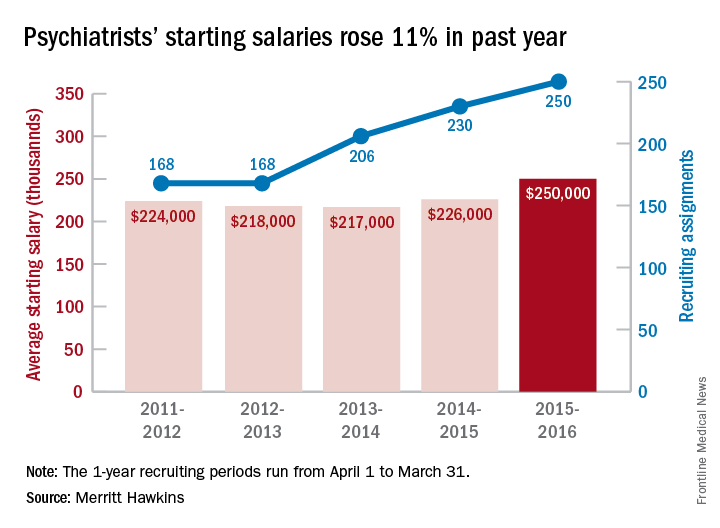

The average starting salary for psychiatrists was up 11% over the last year, with growing physician shortages leading to increased demand, according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The average starting salary was $250,000 among psychiatrists recruited by the company in the 12 months from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016, compared with $226,000 the previous year. Of the 3,342 recruiting searches conducted in that year, 250 involved psychiatry, second highest behind family medicine among the 19 medical specialties tracked in the company’s 2016 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives.

This is the first time in the 23 years of the review that psychiatry has been as high as second on the list of most requested recruiting assignments, although it was third last year and fourth the year before. “This is a clear reflection of the focus health care providers are putting on addressing mental health challenges in the United States,” the report noted.

Starting salaries were up for 18 of the 19 specialties, with only emergency medicine showing a decease. “Demand for physicians is as intense as we have seen it in our 29-year history,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a separate statement. “The expansion of health insurance coverage, population growth, population aging, expanded care sites such as urgent care centers, and other factors are driving demand for doctors through the roof, and salaries are spiking as a consequence.”

The average starting salary for psychiatrists was up 11% over the last year, with growing physician shortages leading to increased demand, according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The average starting salary was $250,000 among psychiatrists recruited by the company in the 12 months from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016, compared with $226,000 the previous year. Of the 3,342 recruiting searches conducted in that year, 250 involved psychiatry, second highest behind family medicine among the 19 medical specialties tracked in the company’s 2016 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives.

This is the first time in the 23 years of the review that psychiatry has been as high as second on the list of most requested recruiting assignments, although it was third last year and fourth the year before. “This is a clear reflection of the focus health care providers are putting on addressing mental health challenges in the United States,” the report noted.

Starting salaries were up for 18 of the 19 specialties, with only emergency medicine showing a decease. “Demand for physicians is as intense as we have seen it in our 29-year history,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a separate statement. “The expansion of health insurance coverage, population growth, population aging, expanded care sites such as urgent care centers, and other factors are driving demand for doctors through the roof, and salaries are spiking as a consequence.”

The average starting salary for psychiatrists was up 11% over the last year, with growing physician shortages leading to increased demand, according to physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

The average starting salary was $250,000 among psychiatrists recruited by the company in the 12 months from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016, compared with $226,000 the previous year. Of the 3,342 recruiting searches conducted in that year, 250 involved psychiatry, second highest behind family medicine among the 19 medical specialties tracked in the company’s 2016 Review of Physician and Advanced Practitioner Recruiting Incentives.

This is the first time in the 23 years of the review that psychiatry has been as high as second on the list of most requested recruiting assignments, although it was third last year and fourth the year before. “This is a clear reflection of the focus health care providers are putting on addressing mental health challenges in the United States,” the report noted.

Starting salaries were up for 18 of the 19 specialties, with only emergency medicine showing a decease. “Demand for physicians is as intense as we have seen it in our 29-year history,” Travis Singleton, senior vice president of Merritt Hawkins, said in a separate statement. “The expansion of health insurance coverage, population growth, population aging, expanded care sites such as urgent care centers, and other factors are driving demand for doctors through the roof, and salaries are spiking as a consequence.”

Fresh Press: ACS Surgery News digital June issue is live on the website

The June issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features coverage of a study of outcomes of common operations in critical access hospitals. The findings suggest that these smaller, rural hospitals are competitive with larger medical centers in costs and postop complications for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, colectomy, and hernia repair.

Don’t miss Dr. Tyler G. Hughes’s report on his visit with colleagues of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. He found some differences and many striking similarities when it comes to challenges faced by surgeons.

The April feature, “Operating with Pain” (2016, p. 1), provoked comments from readers on personal experiences and recommendations around the topic of pain and workplace injury. A sample of these responses can be found on p. 4.

The June issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features coverage of a study of outcomes of common operations in critical access hospitals. The findings suggest that these smaller, rural hospitals are competitive with larger medical centers in costs and postop complications for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, colectomy, and hernia repair.

Don’t miss Dr. Tyler G. Hughes’s report on his visit with colleagues of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. He found some differences and many striking similarities when it comes to challenges faced by surgeons.

The April feature, “Operating with Pain” (2016, p. 1), provoked comments from readers on personal experiences and recommendations around the topic of pain and workplace injury. A sample of these responses can be found on p. 4.

The June issue of ACS Surgery News is available online. Use the mobile app to download or view as a pdf.

This month’s issue features coverage of a study of outcomes of common operations in critical access hospitals. The findings suggest that these smaller, rural hospitals are competitive with larger medical centers in costs and postop complications for appendectomy, cholecystectomy, colectomy, and hernia repair.

Don’t miss Dr. Tyler G. Hughes’s report on his visit with colleagues of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. He found some differences and many striking similarities when it comes to challenges faced by surgeons.

The April feature, “Operating with Pain” (2016, p. 1), provoked comments from readers on personal experiences and recommendations around the topic of pain and workplace injury. A sample of these responses can be found on p. 4.

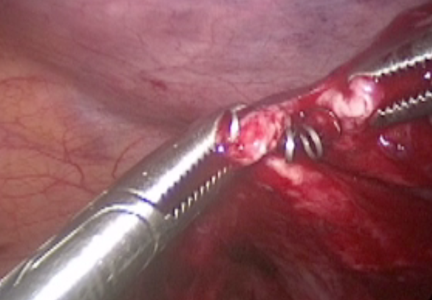

Misplaced hysteroscopic sterilization micro-insert in the peritoneal cavity: A corpus alienum

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

This video is brought to you by ![]()

Pembrolizumab paired with immunostimulator is safe and tolerable

CHICAGO – Combining an immunostimulatory agent with the PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab appeared quite safe and very tolerable, in a small phase Ib study.

There were some signs of efficacy against a variety of solid tumors, as well as biomarker trends showing immune activity.

In the phase Ib trial, researchers combined escalating doses (0.45-5.0 mg/kg) of PF-2566, an investigative immunostimulatory agent, with the anti–PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab at 2 mg/kg, with both drugs given intravenously once every 3 weeks for a maximum of 32 cycles. A primary objective of the trial was to determine a maximum tolerated dose. Secondary objectives were to assess safety and tolerability and to determine any antitumor responses.

PF-2566 (Utomilumab/PF-05082566) is a monoclonal agonist targeting 4-1BB, a “costimulatory molecule that’s induced upon T-cell receptor activation and ultimately enhances cytotoxic T-cell response and effector status,” said Dr. Anthony Tolcher of the START Center for Cancer Care, San Antonio, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Eligible patients were 18 years or older, had a performance status of 0-1, and had advanced or metastatic solid tumors that had progressed on standard therapy or for which no standard therapy was available. They could not have had any form of immunosuppressive therapy in the 2 weeks prior to registration, a monoclonal antibody in the 2 months before the first dose, or any symptomatic or progressing central nervous system primary malignancies. Prior pembrolizumab was permitted.

Twenty-three patients (14 males) were heavily pretreated with a median of three prior therapies (range 0-9) for a variety of cancers, including six non–small-cell lung, five renal cell, three head and neck, and two each pancreatic and thyroid cancers.

Good safety and tolerability profiles

The most prevalent treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were fatigue, rash, cough, nausea, and decreased appetite, affecting 7-10 patients each. All were grade 1/2 except for one grade 3/4 case of fatigue and three cases of grade 3/4 anemia among the 23 patients. Most treatment-related AE’s were grade 1/2, largely fatigue (n = 8) and rash (n = 9). There was one case each of grade 3 adrenal insufficiency and hypokalemia. No patient discontinued the trial because of a treatment-related toxicity. Dr. Tolcher noted that adrenal insufficiency has been reported previously with the use of PD-1 inhibitors. “There does not appear to be any evidence of synergistic or additive toxicity in this patient population,” he said.

Neither drug affected the pharmacokinetics of the other drug or the development of antibodies to the other drug. The maximum tolerated dose of PF-2566 was at least 5 mg/kg every 3 weeks when combined with pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg. No dose-limiting toxicity was observed across the PF-2566 dosing range. And there were no treatment-emergent AEs of clinical relevance.

Pharmacodynamics and efficacy

By day 1 of cycle 5, “there [was] a trend toward increasing numbers of activated CD8 [cytotoxic] T cells in patients who ultimately responded or had a complete response, compared to those that had stable disease or progressive disease. The same actually applies to the effector memory T cells,” Dr. Tolcher said but was careful to point out that the sample sizes were small and it was only a trend. Similarly, circulating levels of gamma-interferon, often used as a biomarker of activated T cells, were higher at 6 and 24 hours post dose in cycle 5 for those patients who ultimately had partial or complete responses, compared with those with progressive or stable disease.

Among the 23 patients, there were two confirmed complete responses and four partial responses as well as one unconfirmed partial response. If responses occurred, they often were durable past 1 year and even out close to 2 years.

The strengths of this study were that it enrolled heavily pretreated patients and there were no drug-drug interactions, no dose-limiting toxicities, and no treatment-related AE’s leading to discontinuation, “so in general a very well-tolerated immunotherapy combination,” said discussant Dr. David Spigel of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn. There were also some durable responses, and he said it was interesting to see that there were some blood biomarkers that correlated with responses.

“It was hard for me to find any weaknesses to this,” Dr. Spigel said, beside the fact that it was a small study. “So what does this change?” He said the combination of pembrolizumab and PF-2566 looks promising in light of some sustained responses in refractory tumors and its safety profile. For the future, expansion trial cohorts are still needed to confirm activity and safety, especially hepatic safety based on trial results with similar drugs, and PF-2566 is already being tested with rituximab in lymphoma and with an anti-CCR4 compound (mogamulizumab).

The study was sponsored by Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Tolcher has ties to several companies, including Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Spigel has ties to several companies, including Pfizer.

CHICAGO – Combining an immunostimulatory agent with the PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab appeared quite safe and very tolerable, in a small phase Ib study.

There were some signs of efficacy against a variety of solid tumors, as well as biomarker trends showing immune activity.

In the phase Ib trial, researchers combined escalating doses (0.45-5.0 mg/kg) of PF-2566, an investigative immunostimulatory agent, with the anti–PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab at 2 mg/kg, with both drugs given intravenously once every 3 weeks for a maximum of 32 cycles. A primary objective of the trial was to determine a maximum tolerated dose. Secondary objectives were to assess safety and tolerability and to determine any antitumor responses.

PF-2566 (Utomilumab/PF-05082566) is a monoclonal agonist targeting 4-1BB, a “costimulatory molecule that’s induced upon T-cell receptor activation and ultimately enhances cytotoxic T-cell response and effector status,” said Dr. Anthony Tolcher of the START Center for Cancer Care, San Antonio, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Eligible patients were 18 years or older, had a performance status of 0-1, and had advanced or metastatic solid tumors that had progressed on standard therapy or for which no standard therapy was available. They could not have had any form of immunosuppressive therapy in the 2 weeks prior to registration, a monoclonal antibody in the 2 months before the first dose, or any symptomatic or progressing central nervous system primary malignancies. Prior pembrolizumab was permitted.

Twenty-three patients (14 males) were heavily pretreated with a median of three prior therapies (range 0-9) for a variety of cancers, including six non–small-cell lung, five renal cell, three head and neck, and two each pancreatic and thyroid cancers.

Good safety and tolerability profiles

The most prevalent treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were fatigue, rash, cough, nausea, and decreased appetite, affecting 7-10 patients each. All were grade 1/2 except for one grade 3/4 case of fatigue and three cases of grade 3/4 anemia among the 23 patients. Most treatment-related AE’s were grade 1/2, largely fatigue (n = 8) and rash (n = 9). There was one case each of grade 3 adrenal insufficiency and hypokalemia. No patient discontinued the trial because of a treatment-related toxicity. Dr. Tolcher noted that adrenal insufficiency has been reported previously with the use of PD-1 inhibitors. “There does not appear to be any evidence of synergistic or additive toxicity in this patient population,” he said.

Neither drug affected the pharmacokinetics of the other drug or the development of antibodies to the other drug. The maximum tolerated dose of PF-2566 was at least 5 mg/kg every 3 weeks when combined with pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg. No dose-limiting toxicity was observed across the PF-2566 dosing range. And there were no treatment-emergent AEs of clinical relevance.

Pharmacodynamics and efficacy

By day 1 of cycle 5, “there [was] a trend toward increasing numbers of activated CD8 [cytotoxic] T cells in patients who ultimately responded or had a complete response, compared to those that had stable disease or progressive disease. The same actually applies to the effector memory T cells,” Dr. Tolcher said but was careful to point out that the sample sizes were small and it was only a trend. Similarly, circulating levels of gamma-interferon, often used as a biomarker of activated T cells, were higher at 6 and 24 hours post dose in cycle 5 for those patients who ultimately had partial or complete responses, compared with those with progressive or stable disease.

Among the 23 patients, there were two confirmed complete responses and four partial responses as well as one unconfirmed partial response. If responses occurred, they often were durable past 1 year and even out close to 2 years.

The strengths of this study were that it enrolled heavily pretreated patients and there were no drug-drug interactions, no dose-limiting toxicities, and no treatment-related AE’s leading to discontinuation, “so in general a very well-tolerated immunotherapy combination,” said discussant Dr. David Spigel of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn. There were also some durable responses, and he said it was interesting to see that there were some blood biomarkers that correlated with responses.

“It was hard for me to find any weaknesses to this,” Dr. Spigel said, beside the fact that it was a small study. “So what does this change?” He said the combination of pembrolizumab and PF-2566 looks promising in light of some sustained responses in refractory tumors and its safety profile. For the future, expansion trial cohorts are still needed to confirm activity and safety, especially hepatic safety based on trial results with similar drugs, and PF-2566 is already being tested with rituximab in lymphoma and with an anti-CCR4 compound (mogamulizumab).

The study was sponsored by Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Tolcher has ties to several companies, including Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Spigel has ties to several companies, including Pfizer.

CHICAGO – Combining an immunostimulatory agent with the PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab appeared quite safe and very tolerable, in a small phase Ib study.

There were some signs of efficacy against a variety of solid tumors, as well as biomarker trends showing immune activity.

In the phase Ib trial, researchers combined escalating doses (0.45-5.0 mg/kg) of PF-2566, an investigative immunostimulatory agent, with the anti–PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab at 2 mg/kg, with both drugs given intravenously once every 3 weeks for a maximum of 32 cycles. A primary objective of the trial was to determine a maximum tolerated dose. Secondary objectives were to assess safety and tolerability and to determine any antitumor responses.

PF-2566 (Utomilumab/PF-05082566) is a monoclonal agonist targeting 4-1BB, a “costimulatory molecule that’s induced upon T-cell receptor activation and ultimately enhances cytotoxic T-cell response and effector status,” said Dr. Anthony Tolcher of the START Center for Cancer Care, San Antonio, at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

Eligible patients were 18 years or older, had a performance status of 0-1, and had advanced or metastatic solid tumors that had progressed on standard therapy or for which no standard therapy was available. They could not have had any form of immunosuppressive therapy in the 2 weeks prior to registration, a monoclonal antibody in the 2 months before the first dose, or any symptomatic or progressing central nervous system primary malignancies. Prior pembrolizumab was permitted.

Twenty-three patients (14 males) were heavily pretreated with a median of three prior therapies (range 0-9) for a variety of cancers, including six non–small-cell lung, five renal cell, three head and neck, and two each pancreatic and thyroid cancers.

Good safety and tolerability profiles

The most prevalent treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were fatigue, rash, cough, nausea, and decreased appetite, affecting 7-10 patients each. All were grade 1/2 except for one grade 3/4 case of fatigue and three cases of grade 3/4 anemia among the 23 patients. Most treatment-related AE’s were grade 1/2, largely fatigue (n = 8) and rash (n = 9). There was one case each of grade 3 adrenal insufficiency and hypokalemia. No patient discontinued the trial because of a treatment-related toxicity. Dr. Tolcher noted that adrenal insufficiency has been reported previously with the use of PD-1 inhibitors. “There does not appear to be any evidence of synergistic or additive toxicity in this patient population,” he said.

Neither drug affected the pharmacokinetics of the other drug or the development of antibodies to the other drug. The maximum tolerated dose of PF-2566 was at least 5 mg/kg every 3 weeks when combined with pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg. No dose-limiting toxicity was observed across the PF-2566 dosing range. And there were no treatment-emergent AEs of clinical relevance.

Pharmacodynamics and efficacy

By day 1 of cycle 5, “there [was] a trend toward increasing numbers of activated CD8 [cytotoxic] T cells in patients who ultimately responded or had a complete response, compared to those that had stable disease or progressive disease. The same actually applies to the effector memory T cells,” Dr. Tolcher said but was careful to point out that the sample sizes were small and it was only a trend. Similarly, circulating levels of gamma-interferon, often used as a biomarker of activated T cells, were higher at 6 and 24 hours post dose in cycle 5 for those patients who ultimately had partial or complete responses, compared with those with progressive or stable disease.

Among the 23 patients, there were two confirmed complete responses and four partial responses as well as one unconfirmed partial response. If responses occurred, they often were durable past 1 year and even out close to 2 years.

The strengths of this study were that it enrolled heavily pretreated patients and there were no drug-drug interactions, no dose-limiting toxicities, and no treatment-related AE’s leading to discontinuation, “so in general a very well-tolerated immunotherapy combination,” said discussant Dr. David Spigel of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn. There were also some durable responses, and he said it was interesting to see that there were some blood biomarkers that correlated with responses.

“It was hard for me to find any weaknesses to this,” Dr. Spigel said, beside the fact that it was a small study. “So what does this change?” He said the combination of pembrolizumab and PF-2566 looks promising in light of some sustained responses in refractory tumors and its safety profile. For the future, expansion trial cohorts are still needed to confirm activity and safety, especially hepatic safety based on trial results with similar drugs, and PF-2566 is already being tested with rituximab in lymphoma and with an anti-CCR4 compound (mogamulizumab).

The study was sponsored by Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Tolcher has ties to several companies, including Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Spigel has ties to several companies, including Pfizer.

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Combining an immunostimulator with pembrolizumab had good tolerability and safety.

Major finding: Two complete and four partial responses occurred among 23 patients.

Data source: Phase Ib trial of 23 patients with a variety of solid tumors.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Tolcher has ties to several companies, including Pfizer and Merck. Dr. Spigel has ties to several companies, including Pfizer.

Ultrasound bests auscultation for ETT positioning

SAN DIEGO – Assessment of the trachea and pleura via point-of-care ultrasound is superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube, a randomized, single-center study found.

“It’s been reported that about 20% of the time the endotracheal tube is malpositioned,” study author Dr. Davinder S. Ramsingh said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. “Most of the time (the tube) is too deep, which can lead to severe complications.”

In a double-blinded, randomized study, Dr. Ramsingh and his associates assessed the accuracy of auscultation vs. point-of-care ultrasound in verifying the correct position of the endotracheal tube (ETT). They enrolled 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT and randomized them to right main bronchus, left main bronchus, or tracheal intubation, followed by fiber optically–guided visualization to place the ETT. Next, an anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used auscultation to assess the location of the ETT, while another anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used point-of-care ultrasound to assess the location of the ETT. The ultrasound exam consisted of assessing tracheal dilation via standard cuff inflation with air and evaluation of pleural lung sliding, explained Dr. Ramsingh of the department of anesthesiology and perioperative care at the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Ramsingh reported that in differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%. Chi-square comparison showed a statistically significant improvement with ultrasound (P = .0005), while inter-observer agreement of the ultrasound findings was 100%.

Limitations of the study, he said, include the fact that “we don’t know the incidence of malpositioned endotracheal tubes in the operating room and that this study was evaluating patients undergoing elective surgical procedures.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Assessment of the trachea and pleura via point-of-care ultrasound is superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube, a randomized, single-center study found.

“It’s been reported that about 20% of the time the endotracheal tube is malpositioned,” study author Dr. Davinder S. Ramsingh said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. “Most of the time (the tube) is too deep, which can lead to severe complications.”

In a double-blinded, randomized study, Dr. Ramsingh and his associates assessed the accuracy of auscultation vs. point-of-care ultrasound in verifying the correct position of the endotracheal tube (ETT). They enrolled 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT and randomized them to right main bronchus, left main bronchus, or tracheal intubation, followed by fiber optically–guided visualization to place the ETT. Next, an anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used auscultation to assess the location of the ETT, while another anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used point-of-care ultrasound to assess the location of the ETT. The ultrasound exam consisted of assessing tracheal dilation via standard cuff inflation with air and evaluation of pleural lung sliding, explained Dr. Ramsingh of the department of anesthesiology and perioperative care at the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Ramsingh reported that in differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%. Chi-square comparison showed a statistically significant improvement with ultrasound (P = .0005), while inter-observer agreement of the ultrasound findings was 100%.

Limitations of the study, he said, include the fact that “we don’t know the incidence of malpositioned endotracheal tubes in the operating room and that this study was evaluating patients undergoing elective surgical procedures.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Assessment of the trachea and pleura via point-of-care ultrasound is superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube, a randomized, single-center study found.

“It’s been reported that about 20% of the time the endotracheal tube is malpositioned,” study author Dr. Davinder S. Ramsingh said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. “Most of the time (the tube) is too deep, which can lead to severe complications.”

In a double-blinded, randomized study, Dr. Ramsingh and his associates assessed the accuracy of auscultation vs. point-of-care ultrasound in verifying the correct position of the endotracheal tube (ETT). They enrolled 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT and randomized them to right main bronchus, left main bronchus, or tracheal intubation, followed by fiber optically–guided visualization to place the ETT. Next, an anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used auscultation to assess the location of the ETT, while another anesthesiologist blinded to the ETT exact location used point-of-care ultrasound to assess the location of the ETT. The ultrasound exam consisted of assessing tracheal dilation via standard cuff inflation with air and evaluation of pleural lung sliding, explained Dr. Ramsingh of the department of anesthesiology and perioperative care at the University of California, Irvine.

Dr. Ramsingh reported that in differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%. Chi-square comparison showed a statistically significant improvement with ultrasound (P = .0005), while inter-observer agreement of the ultrasound findings was 100%.

Limitations of the study, he said, include the fact that “we don’t know the incidence of malpositioned endotracheal tubes in the operating room and that this study was evaluating patients undergoing elective surgical procedures.”

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Using point-of-care ultrasound was superior to auscultation in determining the exact location of the endotracheal tube.

Major finding: In differentiating tracheal versus bronchial intubations, auscultation demonstrated a sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 59%, while ultrasound demonstrated a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96%.

Data source: An randomized study of 42 adults who required general anesthesia with ETT.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Immune agonist, checkpoint inhibitor combo shows good tolerability

CHICAGO – Combining two immunotherapies, one inhibiting immune suppression and the other stimulating immune activation, is well tolerated and shows activity for a variety of solid tumor types, according to a phase I trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Oncology.

Investigators enrolled 51 patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors of any type after progression on standard therapy to a phase Ib dose-escalation study using atezolizumab, a monoclonal antibody checkpoint inhibitor that targets PD-L1, in combination with MOXR0916 (MOXR), an agonist IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting OX40, a costimulatory receptor. Atezolizumab received Food and Drug Administration approval in May 2016 for use in certain patients with urothelial carcinoma. There were 28 patients in a dose-escalation cohort of the study and 23 in a serial biopsy cohort. The dose of the drug combination was started at 12 mg and escalated to understand pharmacodynamic changes in the tumors.

“The pharmacokinetics of both MOXR0916 and atezolizumab were similar to their single-agent data, suggesting no interaction,” reported Dr. Jeffrey Infante of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

The drug combination was well tolerated through the entire escalation range of MOXR. There were no dose-limiting toxicities, and no maximal tolerated dose was reached. There were also no drug-related deaths or grade 4 toxicities or drug-related treatment discontinuations. One case of grade 3 pneumonitis, successfully managed with methylprednisolone and antibiotics, occurred at the MOXR 40-mg dose on cycle 4 of treatment in a patient with non–small-cell lung cancer, he said.

About half the patients (53%) experienced any form of adverse event on the drug combination, and only 8% were grade 2 or 3. There were very few adverse events of any one type, and they did not appear to cluster among patients on the higher MOXR doses. The most prevalent adverse events were nausea, fever, fatigue, and rash, and each was in the 8%-14% range and almost always grade 1.

Many patients showed efficacy of the regimens out to 6-7 cycles regardless of tumor type, and 8 of the 51 patients were still receiving the therapy past cycle 7 with partial responses.

The stimulatory molecule OX40 is not normally expressed on T cells, but it is expressed when antigen interacts with the T-cell receptor, and it can then interact with its ligand, OX40L. The result is production of inflammatory cytokines such as gamma-interferon, activation and survival of effector T cells, and production of memory T cells. At the same time, OX40 activity blocks the suppressive function of regulatory T cells.

“So a molecule that can be a cancer therapeutic such as an OX40 agonist has dual mechanisms of action,” Dr. Infante said. “It can costimulate effector T cells and at the same time inhibit regulatory T cells. Furthermore, there is a reduced risk of toxicity, potentially, as its activity is linked to antigen recognition.”

There is good rationale for using an OX40 agonist such as MOXR, either for its immune stimulatory function or to deactivate immune suppression by regulatory T cells, or both, said discussant Dr. Jedd Wolchok, chief, melanoma and immunotherapeutics service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Infante’s dose-escalation study was “very nicely designed and showed quite good safety,” Dr. Wolchok said, though one thing he would have liked to have seen was a quantification of regulatory T cells in tumor biopsies.

“This [study] is very important considering that this is an agonist antibody, and the agonist agents need to be dosed very deliberatively, as was done here, to ensure safety of patients,” Dr. Wolchok said, adding that further research needs to target “optimal combinatorial partners” and explore other mechanistic biomarkers.

MOXR was given in this trial at escalating doses on a 3+3 design (0.8-1,200 mg) on the same day as atezolizumab 1,200 mg IV once every 3 weeks with a 21-day window for assessment of MOXR dose-limiting toxicities. MOXR doses of 300 mg maintained trough concentrations sufficient to saturate OX40 receptors. An expansion regimen using 300 mg MOXR with atezolizumab 1,200 mg every 3 weeks is underway and will assess efficacy in the treatment of melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, non–small-cell lung cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and triple-negative breast cancer.

The study was sponsored by Roche. Dr. Infante reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Wolchok owns stock in Potenza Therapeutics and Vesuvius Pharmaceuticals, has received travel expenses and/or has an advisory role with several other companies, and is a coinventor on an issued patent for DNA vaccines for the treatment of cancer in companion animals.

CHICAGO – Combining two immunotherapies, one inhibiting immune suppression and the other stimulating immune activation, is well tolerated and shows activity for a variety of solid tumor types, according to a phase I trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Oncology.

Investigators enrolled 51 patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors of any type after progression on standard therapy to a phase Ib dose-escalation study using atezolizumab, a monoclonal antibody checkpoint inhibitor that targets PD-L1, in combination with MOXR0916 (MOXR), an agonist IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting OX40, a costimulatory receptor. Atezolizumab received Food and Drug Administration approval in May 2016 for use in certain patients with urothelial carcinoma. There were 28 patients in a dose-escalation cohort of the study and 23 in a serial biopsy cohort. The dose of the drug combination was started at 12 mg and escalated to understand pharmacodynamic changes in the tumors.

“The pharmacokinetics of both MOXR0916 and atezolizumab were similar to their single-agent data, suggesting no interaction,” reported Dr. Jeffrey Infante of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

The drug combination was well tolerated through the entire escalation range of MOXR. There were no dose-limiting toxicities, and no maximal tolerated dose was reached. There were also no drug-related deaths or grade 4 toxicities or drug-related treatment discontinuations. One case of grade 3 pneumonitis, successfully managed with methylprednisolone and antibiotics, occurred at the MOXR 40-mg dose on cycle 4 of treatment in a patient with non–small-cell lung cancer, he said.

About half the patients (53%) experienced any form of adverse event on the drug combination, and only 8% were grade 2 or 3. There were very few adverse events of any one type, and they did not appear to cluster among patients on the higher MOXR doses. The most prevalent adverse events were nausea, fever, fatigue, and rash, and each was in the 8%-14% range and almost always grade 1.

Many patients showed efficacy of the regimens out to 6-7 cycles regardless of tumor type, and 8 of the 51 patients were still receiving the therapy past cycle 7 with partial responses.

The stimulatory molecule OX40 is not normally expressed on T cells, but it is expressed when antigen interacts with the T-cell receptor, and it can then interact with its ligand, OX40L. The result is production of inflammatory cytokines such as gamma-interferon, activation and survival of effector T cells, and production of memory T cells. At the same time, OX40 activity blocks the suppressive function of regulatory T cells.

“So a molecule that can be a cancer therapeutic such as an OX40 agonist has dual mechanisms of action,” Dr. Infante said. “It can costimulate effector T cells and at the same time inhibit regulatory T cells. Furthermore, there is a reduced risk of toxicity, potentially, as its activity is linked to antigen recognition.”

There is good rationale for using an OX40 agonist such as MOXR, either for its immune stimulatory function or to deactivate immune suppression by regulatory T cells, or both, said discussant Dr. Jedd Wolchok, chief, melanoma and immunotherapeutics service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Infante’s dose-escalation study was “very nicely designed and showed quite good safety,” Dr. Wolchok said, though one thing he would have liked to have seen was a quantification of regulatory T cells in tumor biopsies.

“This [study] is very important considering that this is an agonist antibody, and the agonist agents need to be dosed very deliberatively, as was done here, to ensure safety of patients,” Dr. Wolchok said, adding that further research needs to target “optimal combinatorial partners” and explore other mechanistic biomarkers.

MOXR was given in this trial at escalating doses on a 3+3 design (0.8-1,200 mg) on the same day as atezolizumab 1,200 mg IV once every 3 weeks with a 21-day window for assessment of MOXR dose-limiting toxicities. MOXR doses of 300 mg maintained trough concentrations sufficient to saturate OX40 receptors. An expansion regimen using 300 mg MOXR with atezolizumab 1,200 mg every 3 weeks is underway and will assess efficacy in the treatment of melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, non–small-cell lung cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and triple-negative breast cancer.

The study was sponsored by Roche. Dr. Infante reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Wolchok owns stock in Potenza Therapeutics and Vesuvius Pharmaceuticals, has received travel expenses and/or has an advisory role with several other companies, and is a coinventor on an issued patent for DNA vaccines for the treatment of cancer in companion animals.

CHICAGO – Combining two immunotherapies, one inhibiting immune suppression and the other stimulating immune activation, is well tolerated and shows activity for a variety of solid tumor types, according to a phase I trial presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Oncology.

Investigators enrolled 51 patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors of any type after progression on standard therapy to a phase Ib dose-escalation study using atezolizumab, a monoclonal antibody checkpoint inhibitor that targets PD-L1, in combination with MOXR0916 (MOXR), an agonist IgG1 monoclonal antibody targeting OX40, a costimulatory receptor. Atezolizumab received Food and Drug Administration approval in May 2016 for use in certain patients with urothelial carcinoma. There were 28 patients in a dose-escalation cohort of the study and 23 in a serial biopsy cohort. The dose of the drug combination was started at 12 mg and escalated to understand pharmacodynamic changes in the tumors.

“The pharmacokinetics of both MOXR0916 and atezolizumab were similar to their single-agent data, suggesting no interaction,” reported Dr. Jeffrey Infante of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Nashville, Tenn.

The drug combination was well tolerated through the entire escalation range of MOXR. There were no dose-limiting toxicities, and no maximal tolerated dose was reached. There were also no drug-related deaths or grade 4 toxicities or drug-related treatment discontinuations. One case of grade 3 pneumonitis, successfully managed with methylprednisolone and antibiotics, occurred at the MOXR 40-mg dose on cycle 4 of treatment in a patient with non–small-cell lung cancer, he said.

About half the patients (53%) experienced any form of adverse event on the drug combination, and only 8% were grade 2 or 3. There were very few adverse events of any one type, and they did not appear to cluster among patients on the higher MOXR doses. The most prevalent adverse events were nausea, fever, fatigue, and rash, and each was in the 8%-14% range and almost always grade 1.

Many patients showed efficacy of the regimens out to 6-7 cycles regardless of tumor type, and 8 of the 51 patients were still receiving the therapy past cycle 7 with partial responses.

The stimulatory molecule OX40 is not normally expressed on T cells, but it is expressed when antigen interacts with the T-cell receptor, and it can then interact with its ligand, OX40L. The result is production of inflammatory cytokines such as gamma-interferon, activation and survival of effector T cells, and production of memory T cells. At the same time, OX40 activity blocks the suppressive function of regulatory T cells.

“So a molecule that can be a cancer therapeutic such as an OX40 agonist has dual mechanisms of action,” Dr. Infante said. “It can costimulate effector T cells and at the same time inhibit regulatory T cells. Furthermore, there is a reduced risk of toxicity, potentially, as its activity is linked to antigen recognition.”

There is good rationale for using an OX40 agonist such as MOXR, either for its immune stimulatory function or to deactivate immune suppression by regulatory T cells, or both, said discussant Dr. Jedd Wolchok, chief, melanoma and immunotherapeutics service, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. Dr. Infante’s dose-escalation study was “very nicely designed and showed quite good safety,” Dr. Wolchok said, though one thing he would have liked to have seen was a quantification of regulatory T cells in tumor biopsies.

“This [study] is very important considering that this is an agonist antibody, and the agonist agents need to be dosed very deliberatively, as was done here, to ensure safety of patients,” Dr. Wolchok said, adding that further research needs to target “optimal combinatorial partners” and explore other mechanistic biomarkers.

MOXR was given in this trial at escalating doses on a 3+3 design (0.8-1,200 mg) on the same day as atezolizumab 1,200 mg IV once every 3 weeks with a 21-day window for assessment of MOXR dose-limiting toxicities. MOXR doses of 300 mg maintained trough concentrations sufficient to saturate OX40 receptors. An expansion regimen using 300 mg MOXR with atezolizumab 1,200 mg every 3 weeks is underway and will assess efficacy in the treatment of melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, non–small-cell lung cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and triple-negative breast cancer.

The study was sponsored by Roche. Dr. Infante reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Wolchok owns stock in Potenza Therapeutics and Vesuvius Pharmaceuticals, has received travel expenses and/or has an advisory role with several other companies, and is a coinventor on an issued patent for DNA vaccines for the treatment of cancer in companion animals.

AT THE 2016 ASCO ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Combining an immune agonist and a checkpoint inhibitor shows good tolerability.

Major finding: Eighty-five percent of adverse effects were grade 1; the rest were grade 2/3.

Data source: A phase Ib, open-label multicenter study of 51 patients.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Roche. Dr. Infante reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Wolchok owns stock in Potenza Therapeutics and Vesuvius Pharmaceuticals, has received travel expenses and/or has an advisory role with several other companies, and is a coinventor on an issued patent for DNA vaccines for the treatment of cancer in companion animals.

Daratumumab plus len-dex stalls myeloma progression in POLLUX trial

COPENHAGEN – In a classic case of clinical sibling rivalry, results of the POLLUX trial support the benefits of adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, echoing results reported a few days earlier by investigators in the twin (and archly named) CASTOR trial

Among 569 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, the addition of the anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Darzalex) to lenalidomide (Revlimid) and dexamethasone was associated with a 63% reduction in the risk of disease progress or death, compared with len-dex alone, reported Dr. Meletios A Dimopoulos of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

With daratumumab and len-dex, “there is the highest-ever response rate seen in relapsed or refractory myeloma; 93% of the patients achieved at least a partial response, and more importantly, 43% of the patients achieved a complete response,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

“The addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone induces deep and durable responses. Data indicate that we can achieve minimal residual disease negativity status in a significant number of patients,” he added.

The trial was halted on May 20, 2016, after a preplanned interim analysis showed a significant improvement in the primary endpoint of a progression-free survival, compared with len-dex alone.

Dizygotic twins

Like their mythologic namesakes, who were twin sons from different fathers, the CASTOR and POLLUX trials differed somewhat in the patient populations treated and in trial design. The CASTOR trial is looking at the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib (Velcade) and dexamethasone, and excludes patients resistant to bortezomib. The POLLUX trial includes bortezomib-resistant patients, but excludes lenalidomide-resistant patients.

In addition, in CASTOR, patients were treated with the assigned regimen for a specified number of courses, followed by daratumumab maintenance, whereas patients in both arms in POLLUX continued on their assigned therapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

POLLUX was a multicenter, randomized, open-label phase III trial in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma following one or more prior lines of therapy. They were randomized on a 1:1 basis to either len-dex (283 patients) or len-dex plus intravenous daratumumab at a dose of 16 mg/kg once a week during treatment cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks during cycles 3-6, and once only on day 1 of subsequent cycles.

After a median follow-up of 13.5 months, the median progression-free survival for patients treated with len-dex alone was 18.4 months, but the median was not yet reached among patients treated with daratumumab. The difference translated into a hazard ratio for progression-free survival with daratumumab of 0.37 (P less than .0001).

In addition, the antibody was associated with a significantly better overall response rate (93% for daratumumab vs. 76% for len-dex only; P less than .0001), as well as better rates of complete responses (43% vs. 19%, respectively; P less than .0001), and very good partial responses or better (76% vs. 44%, P less than .0001).

The combination was generally well tolerated, with adverse events consistent with the known safety profile of len-dex. Infusion reactions with daratumumab were generally mild, and tended to occur during the first infusion, Dr. Dimopoulos said.

Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam (the Netherlands), who moderated the briefing, commented that the progression-free survival curves with daratumumab appeared to plateau, and asked whether any patients in the trial could be considered to have been “cured.”

Dr. Dimopoulos replied that “although we believe that in the relapsed setting of myeloma, it is unlikely to achieve the cure rate, we are optimistic that there will be a sizable number of patients that will remain without progression for many months. Already from single-agent daratumumab where this patient population is far more heavily pretreated, there are patients who are without progression for several years.”

Dr. Dimopoulos has previously disclosed honoraria from Janssen, maker of daratumumab. Dr. Hagenbeek disclosed serving on an advisory board for Takeda, maker of bortezomib.

COPENHAGEN – In a classic case of clinical sibling rivalry, results of the POLLUX trial support the benefits of adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, echoing results reported a few days earlier by investigators in the twin (and archly named) CASTOR trial

Among 569 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, the addition of the anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Darzalex) to lenalidomide (Revlimid) and dexamethasone was associated with a 63% reduction in the risk of disease progress or death, compared with len-dex alone, reported Dr. Meletios A Dimopoulos of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

With daratumumab and len-dex, “there is the highest-ever response rate seen in relapsed or refractory myeloma; 93% of the patients achieved at least a partial response, and more importantly, 43% of the patients achieved a complete response,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

“The addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone induces deep and durable responses. Data indicate that we can achieve minimal residual disease negativity status in a significant number of patients,” he added.

The trial was halted on May 20, 2016, after a preplanned interim analysis showed a significant improvement in the primary endpoint of a progression-free survival, compared with len-dex alone.

Dizygotic twins

Like their mythologic namesakes, who were twin sons from different fathers, the CASTOR and POLLUX trials differed somewhat in the patient populations treated and in trial design. The CASTOR trial is looking at the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib (Velcade) and dexamethasone, and excludes patients resistant to bortezomib. The POLLUX trial includes bortezomib-resistant patients, but excludes lenalidomide-resistant patients.

In addition, in CASTOR, patients were treated with the assigned regimen for a specified number of courses, followed by daratumumab maintenance, whereas patients in both arms in POLLUX continued on their assigned therapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

POLLUX was a multicenter, randomized, open-label phase III trial in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma following one or more prior lines of therapy. They were randomized on a 1:1 basis to either len-dex (283 patients) or len-dex plus intravenous daratumumab at a dose of 16 mg/kg once a week during treatment cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks during cycles 3-6, and once only on day 1 of subsequent cycles.

After a median follow-up of 13.5 months, the median progression-free survival for patients treated with len-dex alone was 18.4 months, but the median was not yet reached among patients treated with daratumumab. The difference translated into a hazard ratio for progression-free survival with daratumumab of 0.37 (P less than .0001).

In addition, the antibody was associated with a significantly better overall response rate (93% for daratumumab vs. 76% for len-dex only; P less than .0001), as well as better rates of complete responses (43% vs. 19%, respectively; P less than .0001), and very good partial responses or better (76% vs. 44%, P less than .0001).

The combination was generally well tolerated, with adverse events consistent with the known safety profile of len-dex. Infusion reactions with daratumumab were generally mild, and tended to occur during the first infusion, Dr. Dimopoulos said.

Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam (the Netherlands), who moderated the briefing, commented that the progression-free survival curves with daratumumab appeared to plateau, and asked whether any patients in the trial could be considered to have been “cured.”

Dr. Dimopoulos replied that “although we believe that in the relapsed setting of myeloma, it is unlikely to achieve the cure rate, we are optimistic that there will be a sizable number of patients that will remain without progression for many months. Already from single-agent daratumumab where this patient population is far more heavily pretreated, there are patients who are without progression for several years.”

Dr. Dimopoulos has previously disclosed honoraria from Janssen, maker of daratumumab. Dr. Hagenbeek disclosed serving on an advisory board for Takeda, maker of bortezomib.

COPENHAGEN – In a classic case of clinical sibling rivalry, results of the POLLUX trial support the benefits of adding daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, echoing results reported a few days earlier by investigators in the twin (and archly named) CASTOR trial

Among 569 patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma, the addition of the anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab (Darzalex) to lenalidomide (Revlimid) and dexamethasone was associated with a 63% reduction in the risk of disease progress or death, compared with len-dex alone, reported Dr. Meletios A Dimopoulos of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

With daratumumab and len-dex, “there is the highest-ever response rate seen in relapsed or refractory myeloma; 93% of the patients achieved at least a partial response, and more importantly, 43% of the patients achieved a complete response,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

“The addition of daratumumab to lenalidomide and dexamethasone induces deep and durable responses. Data indicate that we can achieve minimal residual disease negativity status in a significant number of patients,” he added.

The trial was halted on May 20, 2016, after a preplanned interim analysis showed a significant improvement in the primary endpoint of a progression-free survival, compared with len-dex alone.

Dizygotic twins

Like their mythologic namesakes, who were twin sons from different fathers, the CASTOR and POLLUX trials differed somewhat in the patient populations treated and in trial design. The CASTOR trial is looking at the addition of daratumumab to bortezomib (Velcade) and dexamethasone, and excludes patients resistant to bortezomib. The POLLUX trial includes bortezomib-resistant patients, but excludes lenalidomide-resistant patients.

In addition, in CASTOR, patients were treated with the assigned regimen for a specified number of courses, followed by daratumumab maintenance, whereas patients in both arms in POLLUX continued on their assigned therapy until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred.

POLLUX was a multicenter, randomized, open-label phase III trial in patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma following one or more prior lines of therapy. They were randomized on a 1:1 basis to either len-dex (283 patients) or len-dex plus intravenous daratumumab at a dose of 16 mg/kg once a week during treatment cycles 1 and 2, every 2 weeks during cycles 3-6, and once only on day 1 of subsequent cycles.

After a median follow-up of 13.5 months, the median progression-free survival for patients treated with len-dex alone was 18.4 months, but the median was not yet reached among patients treated with daratumumab. The difference translated into a hazard ratio for progression-free survival with daratumumab of 0.37 (P less than .0001).

In addition, the antibody was associated with a significantly better overall response rate (93% for daratumumab vs. 76% for len-dex only; P less than .0001), as well as better rates of complete responses (43% vs. 19%, respectively; P less than .0001), and very good partial responses or better (76% vs. 44%, P less than .0001).

The combination was generally well tolerated, with adverse events consistent with the known safety profile of len-dex. Infusion reactions with daratumumab were generally mild, and tended to occur during the first infusion, Dr. Dimopoulos said.

Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam (the Netherlands), who moderated the briefing, commented that the progression-free survival curves with daratumumab appeared to plateau, and asked whether any patients in the trial could be considered to have been “cured.”

Dr. Dimopoulos replied that “although we believe that in the relapsed setting of myeloma, it is unlikely to achieve the cure rate, we are optimistic that there will be a sizable number of patients that will remain without progression for many months. Already from single-agent daratumumab where this patient population is far more heavily pretreated, there are patients who are without progression for several years.”

Dr. Dimopoulos has previously disclosed honoraria from Janssen, maker of daratumumab. Dr. Hagenbeek disclosed serving on an advisory board for Takeda, maker of bortezomib.

AT THE EHA CONGRESS

Key clinical point: The anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody daratumumab added to lenalidomide/dexamethasone improved progression-free survival in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.

Major finding: The hazard ratio for PFS with daratumumab plus len-dex was 0.37, compared with len-dex alone (P less than .0001).

Data source: An open-label phase III trial in 569 patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma after one or more prior lines of therapy.

Disclosures: Dr. Dimopoulos has previously disclosed honoraria from Janssen, maker of daratumumab. Dr. Hagenbeek disclosed serving on an advisory board for Takeda, maker of bortezomib.

Blinatumomab doubles survival in relapsed Ph-negative ALL

Copenhagen – The monoclonal antibody blinatumomab nearly doubled overall survival compared with standard chemotherapy among patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor leukemia negative for the Philadelphia chromosome, investigators reported.

Among 405 patients enrolled in the TOWER study, a multicenter, open-label phase III trial, median overall survival for patients treated with blinatumomab (Blincyto) was 7.7 months, compared with 4.0 months for patients treated with one of four standard chemotherapy regimens (P = .012) reported Dr. Max S. Topp of Universitätsklinikum in Würzburg, Germany.

“Blinatumomab is the first immunotherapy agent to demonstrate an overall survival benefit when compared to chemotherapy in patients relapsing with adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It increases almost twofold the overall survival when compared to standard care. This was consistent in all subgroups that we were looking at, regardless of age, prior salvage therapy, or patients relapsing after an allo-transplantation,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The trial was halted early, after a preplanned interim analysis showed a clear survival benefit with blinatumomab.

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody designed to direct cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells expressing the CD19 receptor. As previously reported, it has induced high complete remission rates in patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

In May 2015, the Food and Drug Administration granted blinatumomab accelerated approval for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL).

In the TOWER trial, patients with relapsed/refractory BCP-ALL were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive either blinatumomab (271 patients) or standard chemotherapy (134), consisting of the investigator’s choice of one of four defined regimens (based on either anthracyclines, histone deacetylase inhibitors, high-dose methotrexate, or clofarabine).

The patients were further stratified by age, prior salvage therapy, and prior allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT).

Patients assigned to receive blinatumomab received it in 6-week cycles consisting of continuous infusions of 9 mcg/day in week 1 of cycle 1, then 28 mcg/day for weeks 3-4, followed by 2 weeks off. Patients were pretreated with dexamethasone for prophylaxis against the cytokine release syndrome.

Patients whose disease was in remission following two induction cycles could be continued on therapy until relapse.

As noted, the trial was halted early, after 248 patients had died; the primary analysis had been planned to occur after 330 patients had died.

In addition to the superior survival rates, blinatumomab was associated with a higher rate of complete responses (39% vs. 19%, P less than .001) and combined complete responses, complete hematologic responses, and complete responses with incomplete recovery of counts (46% vs. 28%, P = .001).

In all, 19% of patients assigned to blinatumomab and 17% assigned to chemotherapy died on study. Grade 3 or greater adverse events included neutropenia (38% of patients and 58%, respectively), infections (34% and 52%), neurologic events (9% and 8%), and the cytokine release syndrome (5% vs. 0%).

Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam, who moderated the briefing, asked Dr. Topp whether there were plans to use blinatumomab earlier in the course of disease.

Dr. Topp agreed that it might be a valuable addition to upfront therapy, noting that blinatumomab has been shown in a small percentage of patients who are positive for minimal residual disease to convert to being negative for minimal residual disease, and that this conversion was associated with improved overall survival.

Copenhagen – The monoclonal antibody blinatumomab nearly doubled overall survival compared with standard chemotherapy among patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor leukemia negative for the Philadelphia chromosome, investigators reported.

Among 405 patients enrolled in the TOWER study, a multicenter, open-label phase III trial, median overall survival for patients treated with blinatumomab (Blincyto) was 7.7 months, compared with 4.0 months for patients treated with one of four standard chemotherapy regimens (P = .012) reported Dr. Max S. Topp of Universitätsklinikum in Würzburg, Germany.

“Blinatumomab is the first immunotherapy agent to demonstrate an overall survival benefit when compared to chemotherapy in patients relapsing with adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It increases almost twofold the overall survival when compared to standard care. This was consistent in all subgroups that we were looking at, regardless of age, prior salvage therapy, or patients relapsing after an allo-transplantation,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The trial was halted early, after a preplanned interim analysis showed a clear survival benefit with blinatumomab.

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody designed to direct cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells expressing the CD19 receptor. As previously reported, it has induced high complete remission rates in patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

In May 2015, the Food and Drug Administration granted blinatumomab accelerated approval for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL).

In the TOWER trial, patients with relapsed/refractory BCP-ALL were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive either blinatumomab (271 patients) or standard chemotherapy (134), consisting of the investigator’s choice of one of four defined regimens (based on either anthracyclines, histone deacetylase inhibitors, high-dose methotrexate, or clofarabine).

The patients were further stratified by age, prior salvage therapy, and prior allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT).

Patients assigned to receive blinatumomab received it in 6-week cycles consisting of continuous infusions of 9 mcg/day in week 1 of cycle 1, then 28 mcg/day for weeks 3-4, followed by 2 weeks off. Patients were pretreated with dexamethasone for prophylaxis against the cytokine release syndrome.

Patients whose disease was in remission following two induction cycles could be continued on therapy until relapse.

As noted, the trial was halted early, after 248 patients had died; the primary analysis had been planned to occur after 330 patients had died.

In addition to the superior survival rates, blinatumomab was associated with a higher rate of complete responses (39% vs. 19%, P less than .001) and combined complete responses, complete hematologic responses, and complete responses with incomplete recovery of counts (46% vs. 28%, P = .001).

In all, 19% of patients assigned to blinatumomab and 17% assigned to chemotherapy died on study. Grade 3 or greater adverse events included neutropenia (38% of patients and 58%, respectively), infections (34% and 52%), neurologic events (9% and 8%), and the cytokine release syndrome (5% vs. 0%).

Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam, who moderated the briefing, asked Dr. Topp whether there were plans to use blinatumomab earlier in the course of disease.

Dr. Topp agreed that it might be a valuable addition to upfront therapy, noting that blinatumomab has been shown in a small percentage of patients who are positive for minimal residual disease to convert to being negative for minimal residual disease, and that this conversion was associated with improved overall survival.

Copenhagen – The monoclonal antibody blinatumomab nearly doubled overall survival compared with standard chemotherapy among patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell precursor leukemia negative for the Philadelphia chromosome, investigators reported.

Among 405 patients enrolled in the TOWER study, a multicenter, open-label phase III trial, median overall survival for patients treated with blinatumomab (Blincyto) was 7.7 months, compared with 4.0 months for patients treated with one of four standard chemotherapy regimens (P = .012) reported Dr. Max S. Topp of Universitätsklinikum in Würzburg, Germany.

“Blinatumomab is the first immunotherapy agent to demonstrate an overall survival benefit when compared to chemotherapy in patients relapsing with adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. It increases almost twofold the overall survival when compared to standard care. This was consistent in all subgroups that we were looking at, regardless of age, prior salvage therapy, or patients relapsing after an allo-transplantation,” he said at a briefing prior to his presentation of the data at the annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The trial was halted early, after a preplanned interim analysis showed a clear survival benefit with blinatumomab.

Blinatumomab is a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE) antibody designed to direct cytotoxic T cells to cancer cells expressing the CD19 receptor. As previously reported, it has induced high complete remission rates in patients with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

In May 2015, the Food and Drug Administration granted blinatumomab accelerated approval for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (BCP-ALL).

In the TOWER trial, patients with relapsed/refractory BCP-ALL were randomly assigned on a 2:1 basis to receive either blinatumomab (271 patients) or standard chemotherapy (134), consisting of the investigator’s choice of one of four defined regimens (based on either anthracyclines, histone deacetylase inhibitors, high-dose methotrexate, or clofarabine).

The patients were further stratified by age, prior salvage therapy, and prior allogeneic stem cell transplant (alloSCT).

Patients assigned to receive blinatumomab received it in 6-week cycles consisting of continuous infusions of 9 mcg/day in week 1 of cycle 1, then 28 mcg/day for weeks 3-4, followed by 2 weeks off. Patients were pretreated with dexamethasone for prophylaxis against the cytokine release syndrome.

Patients whose disease was in remission following two induction cycles could be continued on therapy until relapse.

As noted, the trial was halted early, after 248 patients had died; the primary analysis had been planned to occur after 330 patients had died.

In addition to the superior survival rates, blinatumomab was associated with a higher rate of complete responses (39% vs. 19%, P less than .001) and combined complete responses, complete hematologic responses, and complete responses with incomplete recovery of counts (46% vs. 28%, P = .001).

In all, 19% of patients assigned to blinatumomab and 17% assigned to chemotherapy died on study. Grade 3 or greater adverse events included neutropenia (38% of patients and 58%, respectively), infections (34% and 52%), neurologic events (9% and 8%), and the cytokine release syndrome (5% vs. 0%).

Dr. Anton Hagenbeek, professor of hematology at the University of Amsterdam, who moderated the briefing, asked Dr. Topp whether there were plans to use blinatumomab earlier in the course of disease.

Dr. Topp agreed that it might be a valuable addition to upfront therapy, noting that blinatumomab has been shown in a small percentage of patients who are positive for minimal residual disease to convert to being negative for minimal residual disease, and that this conversion was associated with improved overall survival.

At THE EHA CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Single-agent blinatumomab nearly doubled overall survival compared to chemotherapy in relapsed/refractory ALL.

Major finding: Median overall survival was 7.7 months for patients on blinatumomab compared with 4.0 months for those on chemotherapy.

Data source: Randomized open-label phase III trial in 405 adults with relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome–negative B-cell precursor ALL.

Disclosures: Amgen funded the study. Dr. Topp disclosed having a consultant or advisory role and receiving other remuneration from Micromet, which was acquired by Amgen. Dr. Hagenbeek reported no relevant disclosures.

Alemtuzumab beneficial for MS patients of African descent

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – A subgroup analysis of 46 patients of African descent with active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) from the CARE-MS I and CARE-MS II trials has demonstrated the efficacy of alemtuzumab over 5 years.

The long-term results implicate alemtuzumab as a valuable treatment option for RRMS patients of African descent. These patients are at higher risk of more severe disease.

“In patients of African descent, alemtuzumab had clinical and [magnetic resonance imaging] efficacy comparable with that observed in the overall CARE-MS study population. Efficacy was durable over 5 years, with the majority of patients not receiving alemtuzumab treatment after month 12,” Dr. Annette Okai of the Multiple Sclerosis Treatment Center of Dallas reported at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Patients of African descent have a heightened risk of MS that is more severe and more rapidly debilitating than that of white patients. As well, disease-modifying therapies may not be as effective in this group. To seek a better treatment option, Dr. Okai and colleagues performed a subgroup analysis involving the alemtuzumab treatment arm of the CARE I and II phase III randomized trials.

In CARE-MS I and II, a total of 811 patients received two annual intravenous injections of 12 mg alemtuzumab during the 2-year core phase of the trial and as-needed treatment during the extension phase from years 3 to 5. The trial cohort comprised 46 patients of African descent (80% from the United States, 76% female). Thirty-two of the 46 patients entered the extension phase.

Of the 32 patients, 17 (53%) did not receive retreatment beginning in year 2, and 28 (88%) did not receive another disease-modifying treatment. The efficacy of alemtuzumab in the overall CARE-MS cohort and in patients of African descent was durable over the full 5 years of the study. In those of African descent, the cumulative 0- to 5-year annualized relapse rate was 0.16. Sixty percent of the patients of African descent were relapse free in years 3-5.

Disease severity as measured by Expanded Disability Status Scale scores did not change appreciably over the 5 years (mean change, +0.52). No evidence of disease activity (NEDA) was observed in 33% of alemtuzumab patients in years 0-2, compared with 13% of those in the subcutaneous interferon beta-1a arm of CARE-MS I and II. Rates of NEDA in year 3, 4, and 5 were 45%, 42%, and 56%, respectively, and NEDA was achieved by 25% of the patients of African descent from years 3 to 5.

There were no serious infusion-associated reactions in the patients of African descent and the safety profile was similar to the overall cohort.

The efficacy and durability of alemtuzumab in the overall cohort generally, and in the patients of African descent more particularly, could reflect immunomodulation that is linked to lymphocyte repopulation, Dr. Okai suggested.

“Based on these findings, alemtuzumab may provide a unique treatment approach with durable efficacy in this high-risk population,” she concluded.

The studies were sponsored by Genzyme and Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Okai disclosed receiving consulting fees from Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, Genentech, Biogen, and EMD Serono.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. – A subgroup analysis of 46 patients of African descent with active relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) from the CARE-MS I and CARE-MS II trials has demonstrated the efficacy of alemtuzumab over 5 years.

The long-term results implicate alemtuzumab as a valuable treatment option for RRMS patients of African descent. These patients are at higher risk of more severe disease.

“In patients of African descent, alemtuzumab had clinical and [magnetic resonance imaging] efficacy comparable with that observed in the overall CARE-MS study population. Efficacy was durable over 5 years, with the majority of patients not receiving alemtuzumab treatment after month 12,” Dr. Annette Okai of the Multiple Sclerosis Treatment Center of Dallas reported at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Patients of African descent have a heightened risk of MS that is more severe and more rapidly debilitating than that of white patients. As well, disease-modifying therapies may not be as effective in this group. To seek a better treatment option, Dr. Okai and colleagues performed a subgroup analysis involving the alemtuzumab treatment arm of the CARE I and II phase III randomized trials.

In CARE-MS I and II, a total of 811 patients received two annual intravenous injections of 12 mg alemtuzumab during the 2-year core phase of the trial and as-needed treatment during the extension phase from years 3 to 5. The trial cohort comprised 46 patients of African descent (80% from the United States, 76% female). Thirty-two of the 46 patients entered the extension phase.

Of the 32 patients, 17 (53%) did not receive retreatment beginning in year 2, and 28 (88%) did not receive another disease-modifying treatment. The efficacy of alemtuzumab in the overall CARE-MS cohort and in patients of African descent was durable over the full 5 years of the study. In those of African descent, the cumulative 0- to 5-year annualized relapse rate was 0.16. Sixty percent of the patients of African descent were relapse free in years 3-5.

Disease severity as measured by Expanded Disability Status Scale scores did not change appreciably over the 5 years (mean change, +0.52). No evidence of disease activity (NEDA) was observed in 33% of alemtuzumab patients in years 0-2, compared with 13% of those in the subcutaneous interferon beta-1a arm of CARE-MS I and II. Rates of NEDA in year 3, 4, and 5 were 45%, 42%, and 56%, respectively, and NEDA was achieved by 25% of the patients of African descent from years 3 to 5.