User login

Phentermine-topiramate shows best chance of weight loss at 1 year

The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight within 1 year, according to a meta-analysis comparing outcomes and adverse events for orlistat, lorcaserin, naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, and liraglutide.

Researchers analyzed 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants and found those who took phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo, according to a paper published in the June 14 issue of JAMA.

Liraglutide showed the second-highest odds of achieving a 5% weight loss at 1 year (odds ratio, 5.54), followed by naltrexone-bupropion (OR, 3.96), lorcaserin (OR, 3.10), and orlistat (OR, 2.70).

Nearly one-quarter of individuals on placebo achieved at least a 5% weight loss by 1 year, compared with three-quarters of individuals taking phentermine-topiramate, 63% of those taking liraglutide, 55% taking naltrexone-bupropion, 49% taking lorcaserin, and 44% taking orlistat (JAMA 2016;315:2424-34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602).

Of those on placebo, only 9% achieved at least a 10% weight loss at 1 year, compared with 54% of patients taking phentermine-topiramate, 34% of patients on liraglutide, 30% of patients on naltrexone-bupropion, 25% of those taking lorcaserin, and 20% of those taking orlistat.

Phentermine-topiramate was also associated with the greatest weight loss, compared with placebo, with patients losing a mean of 8.8 kg vs. 5.2 kg with liraglutide, 5 kg with naltrexone-bupropion, 3.2 kg with lorcaserin, and 2.6 kg with orlistat.

While all active drugs were associated with a higher rate of discontinuation because of adverse events than was seen with placebo, liraglutide was associated with the greatest risk of discontinuation, compared with placebo, followed by naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, orlistat, and then lorcaserin.

Dr. Rohan Khera of the department of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and coauthors wrote that pharmacologic treatment decisions should consider coexisting medical conditions that might influence for or against a particular choice for weight loss.

“For example, liraglutide may be a more appropriate agent in people with diabetes because of its glucose-lowering effects,” they wrote. “Conversely, naltrexone-bupropion in patients with chronic opiate or alcohol dependence may be associated with neuropsychiatric complications.

“Ultimately, given the differences in safety, efficacy, and response to therapy, the ideal approach to weight loss should be highly individualized, identifying appropriate candidates for pharmacotherapy, behavioral interventions, and surgical interventions.”

Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight within 1 year, according to a meta-analysis comparing outcomes and adverse events for orlistat, lorcaserin, naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, and liraglutide.

Researchers analyzed 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants and found those who took phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo, according to a paper published in the June 14 issue of JAMA.

Liraglutide showed the second-highest odds of achieving a 5% weight loss at 1 year (odds ratio, 5.54), followed by naltrexone-bupropion (OR, 3.96), lorcaserin (OR, 3.10), and orlistat (OR, 2.70).

Nearly one-quarter of individuals on placebo achieved at least a 5% weight loss by 1 year, compared with three-quarters of individuals taking phentermine-topiramate, 63% of those taking liraglutide, 55% taking naltrexone-bupropion, 49% taking lorcaserin, and 44% taking orlistat (JAMA 2016;315:2424-34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602).

Of those on placebo, only 9% achieved at least a 10% weight loss at 1 year, compared with 54% of patients taking phentermine-topiramate, 34% of patients on liraglutide, 30% of patients on naltrexone-bupropion, 25% of those taking lorcaserin, and 20% of those taking orlistat.

Phentermine-topiramate was also associated with the greatest weight loss, compared with placebo, with patients losing a mean of 8.8 kg vs. 5.2 kg with liraglutide, 5 kg with naltrexone-bupropion, 3.2 kg with lorcaserin, and 2.6 kg with orlistat.

While all active drugs were associated with a higher rate of discontinuation because of adverse events than was seen with placebo, liraglutide was associated with the greatest risk of discontinuation, compared with placebo, followed by naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, orlistat, and then lorcaserin.

Dr. Rohan Khera of the department of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and coauthors wrote that pharmacologic treatment decisions should consider coexisting medical conditions that might influence for or against a particular choice for weight loss.

“For example, liraglutide may be a more appropriate agent in people with diabetes because of its glucose-lowering effects,” they wrote. “Conversely, naltrexone-bupropion in patients with chronic opiate or alcohol dependence may be associated with neuropsychiatric complications.

“Ultimately, given the differences in safety, efficacy, and response to therapy, the ideal approach to weight loss should be highly individualized, identifying appropriate candidates for pharmacotherapy, behavioral interventions, and surgical interventions.”

Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight within 1 year, according to a meta-analysis comparing outcomes and adverse events for orlistat, lorcaserin, naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, and liraglutide.

Researchers analyzed 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants and found those who took phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo, according to a paper published in the June 14 issue of JAMA.

Liraglutide showed the second-highest odds of achieving a 5% weight loss at 1 year (odds ratio, 5.54), followed by naltrexone-bupropion (OR, 3.96), lorcaserin (OR, 3.10), and orlistat (OR, 2.70).

Nearly one-quarter of individuals on placebo achieved at least a 5% weight loss by 1 year, compared with three-quarters of individuals taking phentermine-topiramate, 63% of those taking liraglutide, 55% taking naltrexone-bupropion, 49% taking lorcaserin, and 44% taking orlistat (JAMA 2016;315:2424-34. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7602).

Of those on placebo, only 9% achieved at least a 10% weight loss at 1 year, compared with 54% of patients taking phentermine-topiramate, 34% of patients on liraglutide, 30% of patients on naltrexone-bupropion, 25% of those taking lorcaserin, and 20% of those taking orlistat.

Phentermine-topiramate was also associated with the greatest weight loss, compared with placebo, with patients losing a mean of 8.8 kg vs. 5.2 kg with liraglutide, 5 kg with naltrexone-bupropion, 3.2 kg with lorcaserin, and 2.6 kg with orlistat.

While all active drugs were associated with a higher rate of discontinuation because of adverse events than was seen with placebo, liraglutide was associated with the greatest risk of discontinuation, compared with placebo, followed by naltrexone-bupropion, phentermine-topiramate, orlistat, and then lorcaserin.

Dr. Rohan Khera of the department of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City, and coauthors wrote that pharmacologic treatment decisions should consider coexisting medical conditions that might influence for or against a particular choice for weight loss.

“For example, liraglutide may be a more appropriate agent in people with diabetes because of its glucose-lowering effects,” they wrote. “Conversely, naltrexone-bupropion in patients with chronic opiate or alcohol dependence may be associated with neuropsychiatric complications.

“Ultimately, given the differences in safety, efficacy, and response to therapy, the ideal approach to weight loss should be highly individualized, identifying appropriate candidates for pharmacotherapy, behavioral interventions, and surgical interventions.”

Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: The combination weight-loss drug phentermine plus topiramate is associated with the highest odds of individuals being able to lose 5% of their body weight by 1 year, compared with four other weight-loss drugs.

Major finding: Patients taking phentermine-topiramate had a ninefold greater likelihood of achieving a 5% weight loss by 1 year than did those on placebo.

Data source: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 28 randomized placebo- or active-controlled clinical trials involving a total of 29,018 participants.

Disclosures: Two study authors were supported by a grant from the National Library of Medicine or the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. One author reported receiving funding, participating on advisory committees, and serving as a consultant with a range of pharmaceutical manufacturers, as well as being a cofounder of Liponexus. Another author reported research support from NovoNordisk for research on liraglutide. No other disclosures were reported.

Full resolution of psoriasis in half of ixekizumab patients

More than half of the patients treated with the interleukin-17A antagonist, ixekizumab, achieved full resolution of skin plaques after a year of 2- to 4-week dosing, according to the latest analysis of data from the three UNCOVER trials of almost 4,000 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

The results of the three randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal trials were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512711).

Ixekizumab was approved in March for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy; it is marketed as Taltz by Eli Lilly. Some of the UNCOVER data have been previously reported. The UNCOVER studies were conducted at more than 100 sites in 21 countries.

Patients in the UNCOVER trials were randomized to 80 mg of ixekizumab every 2 weeks after a starting dose of 160 mg, 80 mg every 4 weeks after the same starting dose, or subcutaneous placebo injections, for 12 weeks.

In the UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 trials, additional cohorts were also randomized to twice-weekly etanercept (50 mg). All three trials also included a long-term extension period to 60 weeks, which was randomly assigned in UNCOVER-3 (where patients received 80 mg of ixekizumab every 4 weeks), or was implemented for all patients who responded to ixekizumab in the other two trials (where patients were randomized to 80 mg every 4 or 12 weeks, or placebo).

In the UNCOVER-1 trial in 1,296 patients, 89.1% of patients in the 2-week dosing group and 82.6% of the 4-week dosing group had achieved a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75) by week 12, compared with 3.9% in the placebo group (P less than .0001 for all). Similarly, 35.3% of patients in the 2-week dosing group and 33.6% of those in the 4-week dosing group achieved a PASI score of 100 by week 12.

The high response rates seen during the induction period “were generally maintained during the long-term extension period in UNCOVER-3,” wrote Dr. Kenneth B. Gordon, professor of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, and his coauthors. In the analysis of the long-term data from UNCOVER-3, the researchers reported that by week 60, 55% of patients receiving 80 mg of ixekizumab every 2 weeks during the induction period had achieved a PASI 100, and 52% of patients receiving ixekizumab every 4 weeks during the induction period had achieved a PASI 100.

Patients randomized to 80 mg of ixekizumab every 12 weeks after the first 12 weeks of treatment also showed significant long-term responses in the UNCOVER-1 and -2 trials. Nearly half (49.1%) of those who were initiated on 2-week dosing and 44.9% of those initiated on 4-week dosing achieved a PASI score of 75 on the 12-week dosing schedule, compared with 8%-9% of those randomized to placebo from week 12 through week 60.

The authors concluded that ixekizumab “provided high levels of clinical response at week 12 and through week 60,” adding, however, that “as with any treatment, the benefits need to be weighed against the adverse events, and the safety profile of longer-term treatment with ixekizumab should be examined.”

Although low serum IL-17 levels have previously been linked with cardiovascular disease, the study found no significant differences between the treatment and placebo groups in adverse cardiovascular events. Candidal infections were more common among those treated with ixekizumab, “a finding that is consistent with the role of IL-17A in the mucocutaneous defense against fungal infections,” they wrote.

There were 11 cases of inflammatory bowel disease reported among patients during treatment with ixekizumab and another three cases in patients receiving placebo during a randomized withdrawal period, who had received ixekizumab during the induction* period. These results “suggest that further evaluation is needed to understand the relationship between IL-17A inhibitors and inflammatory bowel disease,” the investigators said.

The authors of the study include Eli Lilly employees, several of whom also have stock options; the other authors declared a range of funding, advisory board positions, and speakers fees from pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly. The UNCOVER studies were sponsored by Eli Lilly.

*A previous version of this article misstated the period during which three placebo patients received ixekizumab.

More than half of the patients treated with the interleukin-17A antagonist, ixekizumab, achieved full resolution of skin plaques after a year of 2- to 4-week dosing, according to the latest analysis of data from the three UNCOVER trials of almost 4,000 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

The results of the three randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal trials were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512711).

Ixekizumab was approved in March for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy; it is marketed as Taltz by Eli Lilly. Some of the UNCOVER data have been previously reported. The UNCOVER studies were conducted at more than 100 sites in 21 countries.

Patients in the UNCOVER trials were randomized to 80 mg of ixekizumab every 2 weeks after a starting dose of 160 mg, 80 mg every 4 weeks after the same starting dose, or subcutaneous placebo injections, for 12 weeks.

In the UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 trials, additional cohorts were also randomized to twice-weekly etanercept (50 mg). All three trials also included a long-term extension period to 60 weeks, which was randomly assigned in UNCOVER-3 (where patients received 80 mg of ixekizumab every 4 weeks), or was implemented for all patients who responded to ixekizumab in the other two trials (where patients were randomized to 80 mg every 4 or 12 weeks, or placebo).

In the UNCOVER-1 trial in 1,296 patients, 89.1% of patients in the 2-week dosing group and 82.6% of the 4-week dosing group had achieved a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75) by week 12, compared with 3.9% in the placebo group (P less than .0001 for all). Similarly, 35.3% of patients in the 2-week dosing group and 33.6% of those in the 4-week dosing group achieved a PASI score of 100 by week 12.

The high response rates seen during the induction period “were generally maintained during the long-term extension period in UNCOVER-3,” wrote Dr. Kenneth B. Gordon, professor of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, and his coauthors. In the analysis of the long-term data from UNCOVER-3, the researchers reported that by week 60, 55% of patients receiving 80 mg of ixekizumab every 2 weeks during the induction period had achieved a PASI 100, and 52% of patients receiving ixekizumab every 4 weeks during the induction period had achieved a PASI 100.

Patients randomized to 80 mg of ixekizumab every 12 weeks after the first 12 weeks of treatment also showed significant long-term responses in the UNCOVER-1 and -2 trials. Nearly half (49.1%) of those who were initiated on 2-week dosing and 44.9% of those initiated on 4-week dosing achieved a PASI score of 75 on the 12-week dosing schedule, compared with 8%-9% of those randomized to placebo from week 12 through week 60.

The authors concluded that ixekizumab “provided high levels of clinical response at week 12 and through week 60,” adding, however, that “as with any treatment, the benefits need to be weighed against the adverse events, and the safety profile of longer-term treatment with ixekizumab should be examined.”

Although low serum IL-17 levels have previously been linked with cardiovascular disease, the study found no significant differences between the treatment and placebo groups in adverse cardiovascular events. Candidal infections were more common among those treated with ixekizumab, “a finding that is consistent with the role of IL-17A in the mucocutaneous defense against fungal infections,” they wrote.

There were 11 cases of inflammatory bowel disease reported among patients during treatment with ixekizumab and another three cases in patients receiving placebo during a randomized withdrawal period, who had received ixekizumab during the induction* period. These results “suggest that further evaluation is needed to understand the relationship between IL-17A inhibitors and inflammatory bowel disease,” the investigators said.

The authors of the study include Eli Lilly employees, several of whom also have stock options; the other authors declared a range of funding, advisory board positions, and speakers fees from pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly. The UNCOVER studies were sponsored by Eli Lilly.

*A previous version of this article misstated the period during which three placebo patients received ixekizumab.

More than half of the patients treated with the interleukin-17A antagonist, ixekizumab, achieved full resolution of skin plaques after a year of 2- to 4-week dosing, according to the latest analysis of data from the three UNCOVER trials of almost 4,000 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.

The results of the three randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal trials were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1512711).

Ixekizumab was approved in March for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy; it is marketed as Taltz by Eli Lilly. Some of the UNCOVER data have been previously reported. The UNCOVER studies were conducted at more than 100 sites in 21 countries.

Patients in the UNCOVER trials were randomized to 80 mg of ixekizumab every 2 weeks after a starting dose of 160 mg, 80 mg every 4 weeks after the same starting dose, or subcutaneous placebo injections, for 12 weeks.

In the UNCOVER-2 and UNCOVER-3 trials, additional cohorts were also randomized to twice-weekly etanercept (50 mg). All three trials also included a long-term extension period to 60 weeks, which was randomly assigned in UNCOVER-3 (where patients received 80 mg of ixekizumab every 4 weeks), or was implemented for all patients who responded to ixekizumab in the other two trials (where patients were randomized to 80 mg every 4 or 12 weeks, or placebo).

In the UNCOVER-1 trial in 1,296 patients, 89.1% of patients in the 2-week dosing group and 82.6% of the 4-week dosing group had achieved a 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75) by week 12, compared with 3.9% in the placebo group (P less than .0001 for all). Similarly, 35.3% of patients in the 2-week dosing group and 33.6% of those in the 4-week dosing group achieved a PASI score of 100 by week 12.

The high response rates seen during the induction period “were generally maintained during the long-term extension period in UNCOVER-3,” wrote Dr. Kenneth B. Gordon, professor of dermatology, Northwestern University, Chicago, and his coauthors. In the analysis of the long-term data from UNCOVER-3, the researchers reported that by week 60, 55% of patients receiving 80 mg of ixekizumab every 2 weeks during the induction period had achieved a PASI 100, and 52% of patients receiving ixekizumab every 4 weeks during the induction period had achieved a PASI 100.

Patients randomized to 80 mg of ixekizumab every 12 weeks after the first 12 weeks of treatment also showed significant long-term responses in the UNCOVER-1 and -2 trials. Nearly half (49.1%) of those who were initiated on 2-week dosing and 44.9% of those initiated on 4-week dosing achieved a PASI score of 75 on the 12-week dosing schedule, compared with 8%-9% of those randomized to placebo from week 12 through week 60.

The authors concluded that ixekizumab “provided high levels of clinical response at week 12 and through week 60,” adding, however, that “as with any treatment, the benefits need to be weighed against the adverse events, and the safety profile of longer-term treatment with ixekizumab should be examined.”

Although low serum IL-17 levels have previously been linked with cardiovascular disease, the study found no significant differences between the treatment and placebo groups in adverse cardiovascular events. Candidal infections were more common among those treated with ixekizumab, “a finding that is consistent with the role of IL-17A in the mucocutaneous defense against fungal infections,” they wrote.

There were 11 cases of inflammatory bowel disease reported among patients during treatment with ixekizumab and another three cases in patients receiving placebo during a randomized withdrawal period, who had received ixekizumab during the induction* period. These results “suggest that further evaluation is needed to understand the relationship between IL-17A inhibitors and inflammatory bowel disease,” the investigators said.

The authors of the study include Eli Lilly employees, several of whom also have stock options; the other authors declared a range of funding, advisory board positions, and speakers fees from pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly. The UNCOVER studies were sponsored by Eli Lilly.

*A previous version of this article misstated the period during which three placebo patients received ixekizumab.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Half of patients treated with the IL-17A–neutralizing ixekizumab achieve full resolution of psoriasis plaques after 1 year.

Major finding: Among psoriasis patients treated with two weekly or four weekly doses of ixekizumab, 55% and 52%, respectively, achieve full resolution of plaques at 60 weeks.

Data source: Randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trials (UNCOVER-1, -2, and -3) in 3,866 patients with psoriasis.

Disclosures: The studies were supported by Eli Lilly. The authors included employees of Eli Lilly, some of whom have stock options, while the other authors all declared a range of funding, advisory board positions, and speakers fees from pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly.

Comparing Pneumococcal Vaccines

The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for immunocompromised adults at risk for invasive pneumococcal diseases. But booster doses reportedly can cause “hyporesponsiveness,” which make PPSV23 less suitable for some HIV-infected patients, according to researchers at University Division of Infectious Diseases, Siena, University of Siena, San Gerardo Hospital, University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, and Institute of Clinical Infectious Diseases, Rome, all in Italy. These researchers cite studies that have found that the humoral response to PPSV23 is weaker in HIV-infected adults and that patients with AIDS are not protected.

Protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccines (PCVs), both 7-valent and 13-valent, may prime the immune system for better, faster responses to booster doses, the researchers say, and could be an optimal primary prophylaxis strategy for HIV-infected patients. But to the best of their knowledge, they note, data regarding the effectiveness of PCV13 in HIV-positive adults are “scant,” and no studies have directly compared the immunogenicity of PCV13 with PPSV23 in those patients.

The researchers conducted 2 parallel studies of 100 HIV-infected adult outpatients who had never been vaccinated with any pneumococcal vaccine. In the first, 50 patients were given PCV13 in 2 doses 8 weeks apart; in the second, patients were given their first routine vaccination with PPSV23. A third group of 100 HIV-negative adults who received no vaccination was used for comparison.

Related: Intervals between Pneumococcal Vaccines

After immunization, IgG titers significantly increased in both study groups at each time point compared with baseline, although response to serotype 3 was blunted in the first group. Antibody titers for each antigen did not differ between the groups at week 48. Seroprotection and seroconversion to all serotypes were comparable.

Over time, the researchers observed a “marked decrease” in IgG levels with both vaccines.

Related: Hunting Down a C difficile Vaccine

Both vaccines were safe and well tolerated; no relevant adverse reactions were seen in either group. No HIV-infected patients developed Streptococcus pneumoniae infection during the follow-up.

The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for immunocompromised adults at risk for invasive pneumococcal diseases. But booster doses reportedly can cause “hyporesponsiveness,” which make PPSV23 less suitable for some HIV-infected patients, according to researchers at University Division of Infectious Diseases, Siena, University of Siena, San Gerardo Hospital, University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, and Institute of Clinical Infectious Diseases, Rome, all in Italy. These researchers cite studies that have found that the humoral response to PPSV23 is weaker in HIV-infected adults and that patients with AIDS are not protected.

Protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccines (PCVs), both 7-valent and 13-valent, may prime the immune system for better, faster responses to booster doses, the researchers say, and could be an optimal primary prophylaxis strategy for HIV-infected patients. But to the best of their knowledge, they note, data regarding the effectiveness of PCV13 in HIV-positive adults are “scant,” and no studies have directly compared the immunogenicity of PCV13 with PPSV23 in those patients.

The researchers conducted 2 parallel studies of 100 HIV-infected adult outpatients who had never been vaccinated with any pneumococcal vaccine. In the first, 50 patients were given PCV13 in 2 doses 8 weeks apart; in the second, patients were given their first routine vaccination with PPSV23. A third group of 100 HIV-negative adults who received no vaccination was used for comparison.

Related: Intervals between Pneumococcal Vaccines

After immunization, IgG titers significantly increased in both study groups at each time point compared with baseline, although response to serotype 3 was blunted in the first group. Antibody titers for each antigen did not differ between the groups at week 48. Seroprotection and seroconversion to all serotypes were comparable.

Over time, the researchers observed a “marked decrease” in IgG levels with both vaccines.

Related: Hunting Down a C difficile Vaccine

Both vaccines were safe and well tolerated; no relevant adverse reactions were seen in either group. No HIV-infected patients developed Streptococcus pneumoniae infection during the follow-up.

The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) is recommended for immunocompromised adults at risk for invasive pneumococcal diseases. But booster doses reportedly can cause “hyporesponsiveness,” which make PPSV23 less suitable for some HIV-infected patients, according to researchers at University Division of Infectious Diseases, Siena, University of Siena, San Gerardo Hospital, University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, and Institute of Clinical Infectious Diseases, Rome, all in Italy. These researchers cite studies that have found that the humoral response to PPSV23 is weaker in HIV-infected adults and that patients with AIDS are not protected.

Protein-conjugated pneumococcal vaccines (PCVs), both 7-valent and 13-valent, may prime the immune system for better, faster responses to booster doses, the researchers say, and could be an optimal primary prophylaxis strategy for HIV-infected patients. But to the best of their knowledge, they note, data regarding the effectiveness of PCV13 in HIV-positive adults are “scant,” and no studies have directly compared the immunogenicity of PCV13 with PPSV23 in those patients.

The researchers conducted 2 parallel studies of 100 HIV-infected adult outpatients who had never been vaccinated with any pneumococcal vaccine. In the first, 50 patients were given PCV13 in 2 doses 8 weeks apart; in the second, patients were given their first routine vaccination with PPSV23. A third group of 100 HIV-negative adults who received no vaccination was used for comparison.

Related: Intervals between Pneumococcal Vaccines

After immunization, IgG titers significantly increased in both study groups at each time point compared with baseline, although response to serotype 3 was blunted in the first group. Antibody titers for each antigen did not differ between the groups at week 48. Seroprotection and seroconversion to all serotypes were comparable.

Over time, the researchers observed a “marked decrease” in IgG levels with both vaccines.

Related: Hunting Down a C difficile Vaccine

Both vaccines were safe and well tolerated; no relevant adverse reactions were seen in either group. No HIV-infected patients developed Streptococcus pneumoniae infection during the follow-up.

Biotechs Accelerate Anthrax Vaccine Development

One of the nation’s Centers for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing, led by the Texas A&M University System, is beginning development and manufacturing on a second-generation anthrax vaccine. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response is supporting this research with an 18-month, $10.49 million task order.

NasoShield, a nose spray, will require only a single dose to protect against infections caused by inhaling anthrax. The spray uses technology known as the Adenovirus 5 viral vectored delivery system that modifies a non-infectious virus to include the genetic material needed to produce an immune response against anthrax. The researchers also will focus on improving the shelf life of the anthrax vaccine.

This project is the first time the HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has supported development of an anthrax vaccine using this delivery system. “Anthrax remains a material threat to our national health security,” said Dr. Richard Hatchett, acting BARDA director. “To help combat the health impacts of an anthrax attack, BARDA partnered with several biotechnology firms in accelerating development of promising next-generation treatments against anthrax infection. Engaging one of our Centers for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing represents a unique approach to this development.”

One of the nation’s Centers for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing, led by the Texas A&M University System, is beginning development and manufacturing on a second-generation anthrax vaccine. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response is supporting this research with an 18-month, $10.49 million task order.

NasoShield, a nose spray, will require only a single dose to protect against infections caused by inhaling anthrax. The spray uses technology known as the Adenovirus 5 viral vectored delivery system that modifies a non-infectious virus to include the genetic material needed to produce an immune response against anthrax. The researchers also will focus on improving the shelf life of the anthrax vaccine.

This project is the first time the HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has supported development of an anthrax vaccine using this delivery system. “Anthrax remains a material threat to our national health security,” said Dr. Richard Hatchett, acting BARDA director. “To help combat the health impacts of an anthrax attack, BARDA partnered with several biotechnology firms in accelerating development of promising next-generation treatments against anthrax infection. Engaging one of our Centers for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing represents a unique approach to this development.”

One of the nation’s Centers for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing, led by the Texas A&M University System, is beginning development and manufacturing on a second-generation anthrax vaccine. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response is supporting this research with an 18-month, $10.49 million task order.

NasoShield, a nose spray, will require only a single dose to protect against infections caused by inhaling anthrax. The spray uses technology known as the Adenovirus 5 viral vectored delivery system that modifies a non-infectious virus to include the genetic material needed to produce an immune response against anthrax. The researchers also will focus on improving the shelf life of the anthrax vaccine.

This project is the first time the HHS’s Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) has supported development of an anthrax vaccine using this delivery system. “Anthrax remains a material threat to our national health security,” said Dr. Richard Hatchett, acting BARDA director. “To help combat the health impacts of an anthrax attack, BARDA partnered with several biotechnology firms in accelerating development of promising next-generation treatments against anthrax infection. Engaging one of our Centers for Innovation in Advanced Development and Manufacturing represents a unique approach to this development.”

Midodrine cuts ICU days in septic shock patients

Septic shock patients who received midodrine needed significantly fewer intravenous vasopressors during recovery and had shorter hospital stays, based on data from a retrospective study of 275 adults at a single tertiary care center.

In many institutions, policy dictates that patients must remain in the ICU as long as they need intravenous vasopressors, wrote Dr. Micah R. Whitson of North Shore-LIJ Health System in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues. “One solution to this problem may be replacement of IV vasopressors with an oral agent.”

“Midodrine facilitated earlier patient transfer from the ICU and more efficient allocation of ICU resources,” the researchers wrote (Chest. 2016;149[6]:1380-83).

The researchers compared data on 135 patients treated with midodrine in addition to an intravenous vasopressor and 140 patients treated with an intravenous vasopressor alone.

Overall, patients given midodrine received intravenous vasopressors for 2.9 days while the other group received intravenous vasopressors for 3.8 days, a significant 24% difference. Hospital length of stay was not significantly different, averaging 22 days in the midodrine group and 24 days in the intravenous vasopressor–only group. However, ICU length of stay averaged 7.5 days in the midodrine group and 9.4 days in the vasopressor-only group, a significant 20% reduction. Further, the midodrine group was significantly less likely to reinstitute intravenous vasopressors than the intravenous vasopressor–only group (5.2% vs. 15%, respectively). ICU and hospital mortality rates were not significantly different between the two groups, Dr. Whitson and associates reported.

Patients in the midodrine group received a starting dose of 10 mg every 8 hours, which was increased incrementally until they no longer needed intravenous vasopressors. The maximum midodrine dose in the study was 18.7 mg every 8 hours, and the average duration of use was 6 days.

The patients’ average age was 65 years in the intravenous vasopressor group and 69 years in the midodrine group. Other demographic factors did not significantly differ between the two groups.

One patient discontinued midodrine before discontinuing an intravenous vasopressor because of bradycardia, which resolved without additional treatment.

The findings were limited by the observational nature of the study and the use of data from a single center, the investigators noted. The results, however, support the safety of midodrine and the study “lays the groundwork for a prospective, randomized controlled trial that will examine efficacy, starting dose, escalation, tapering and appropriate patient selection for midodrine use during recovery from septic shock,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Septic shock patients who received midodrine needed significantly fewer intravenous vasopressors during recovery and had shorter hospital stays, based on data from a retrospective study of 275 adults at a single tertiary care center.

In many institutions, policy dictates that patients must remain in the ICU as long as they need intravenous vasopressors, wrote Dr. Micah R. Whitson of North Shore-LIJ Health System in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues. “One solution to this problem may be replacement of IV vasopressors with an oral agent.”

“Midodrine facilitated earlier patient transfer from the ICU and more efficient allocation of ICU resources,” the researchers wrote (Chest. 2016;149[6]:1380-83).

The researchers compared data on 135 patients treated with midodrine in addition to an intravenous vasopressor and 140 patients treated with an intravenous vasopressor alone.

Overall, patients given midodrine received intravenous vasopressors for 2.9 days while the other group received intravenous vasopressors for 3.8 days, a significant 24% difference. Hospital length of stay was not significantly different, averaging 22 days in the midodrine group and 24 days in the intravenous vasopressor–only group. However, ICU length of stay averaged 7.5 days in the midodrine group and 9.4 days in the vasopressor-only group, a significant 20% reduction. Further, the midodrine group was significantly less likely to reinstitute intravenous vasopressors than the intravenous vasopressor–only group (5.2% vs. 15%, respectively). ICU and hospital mortality rates were not significantly different between the two groups, Dr. Whitson and associates reported.

Patients in the midodrine group received a starting dose of 10 mg every 8 hours, which was increased incrementally until they no longer needed intravenous vasopressors. The maximum midodrine dose in the study was 18.7 mg every 8 hours, and the average duration of use was 6 days.

The patients’ average age was 65 years in the intravenous vasopressor group and 69 years in the midodrine group. Other demographic factors did not significantly differ between the two groups.

One patient discontinued midodrine before discontinuing an intravenous vasopressor because of bradycardia, which resolved without additional treatment.

The findings were limited by the observational nature of the study and the use of data from a single center, the investigators noted. The results, however, support the safety of midodrine and the study “lays the groundwork for a prospective, randomized controlled trial that will examine efficacy, starting dose, escalation, tapering and appropriate patient selection for midodrine use during recovery from septic shock,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Septic shock patients who received midodrine needed significantly fewer intravenous vasopressors during recovery and had shorter hospital stays, based on data from a retrospective study of 275 adults at a single tertiary care center.

In many institutions, policy dictates that patients must remain in the ICU as long as they need intravenous vasopressors, wrote Dr. Micah R. Whitson of North Shore-LIJ Health System in New Hyde Park, N.Y., and colleagues. “One solution to this problem may be replacement of IV vasopressors with an oral agent.”

“Midodrine facilitated earlier patient transfer from the ICU and more efficient allocation of ICU resources,” the researchers wrote (Chest. 2016;149[6]:1380-83).

The researchers compared data on 135 patients treated with midodrine in addition to an intravenous vasopressor and 140 patients treated with an intravenous vasopressor alone.

Overall, patients given midodrine received intravenous vasopressors for 2.9 days while the other group received intravenous vasopressors for 3.8 days, a significant 24% difference. Hospital length of stay was not significantly different, averaging 22 days in the midodrine group and 24 days in the intravenous vasopressor–only group. However, ICU length of stay averaged 7.5 days in the midodrine group and 9.4 days in the vasopressor-only group, a significant 20% reduction. Further, the midodrine group was significantly less likely to reinstitute intravenous vasopressors than the intravenous vasopressor–only group (5.2% vs. 15%, respectively). ICU and hospital mortality rates were not significantly different between the two groups, Dr. Whitson and associates reported.

Patients in the midodrine group received a starting dose of 10 mg every 8 hours, which was increased incrementally until they no longer needed intravenous vasopressors. The maximum midodrine dose in the study was 18.7 mg every 8 hours, and the average duration of use was 6 days.

The patients’ average age was 65 years in the intravenous vasopressor group and 69 years in the midodrine group. Other demographic factors did not significantly differ between the two groups.

One patient discontinued midodrine before discontinuing an intravenous vasopressor because of bradycardia, which resolved without additional treatment.

The findings were limited by the observational nature of the study and the use of data from a single center, the investigators noted. The results, however, support the safety of midodrine and the study “lays the groundwork for a prospective, randomized controlled trial that will examine efficacy, starting dose, escalation, tapering and appropriate patient selection for midodrine use during recovery from septic shock,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: Midodrine may reduce ICU length of stay by reducing the need for intravenous vasopressors in patients recovering from septic shock.

Major finding: The mean intravenous vasopressor duration was 2.9 days for patients who received midodrine vs. 3.8 days for controls who received intravenous vasopressors alone.

Data source: A retrospective study involving 275 patients that was conducted in a single medical intensive care unit.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

HIV rapid tests miss 1 in 7 infections

Rapid HIV tests in high-income countries miss about one in seven infections and should be used in combination with fourth-generation enzyme immunoassays (EIA) or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) in clinical settings, according to a study in the journal AIDS.

“These infections are likely to be particularly transmissible due to the high HIV viral load in early infection ... in high-income countries, rapid tests should be used in combination with fourth-generation EIA or NAAT, except in special circumstances,” the Australian researchers said.

They performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 studies involving 110,122 HIV rapid test results. The primary outcome was the test’s sensitivity for detecting acute or established HIV infections. Sensitivity was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed positive rapid tests by the number of confirmed positive comparator tests. Specificity was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed negative rapid tests by the number of negative comparator tests.

Compared with EIA, the estimated sensitivity of rapid tests was 94.5% (95% confidence interval, 87.4-97.7). Compared with NAAT, the sensitivity of rapid tests was 93.7% (95% CI, 88.7-96.5). The sensitivity of rapid tests in high income countries was 85.7% (95% CI, 81.9-88.9), and in low income countries was 97.7% (95% CI, 95.2-98·9), compared with either EIA or NAAT (P less than .01 for difference between settings). Proportions of antibody negative acute infections were 13.6% (95% CI, 10.1-18.0) and 4.7% (95% CI, 2.8-7.7) in studies from high- and low-income countries respectively (P less than .01).

Rapid tests were less sensitive when used in clinical settings in high-income countries, regardless of whether they were compared with a NAAT or fourth-generation EIA. However, the researchers noted that the discrepancy between high- and low-income countries could be attributed to the higher proportion of acute HIV infections (antibody-negative NAAT positive) in populations tested in high-income countries, which might reflect higher background testing rates or a higher incidence of HIV in men who have sex with men.

Read the full study in AIDS (doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001134).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Rapid HIV tests in high-income countries miss about one in seven infections and should be used in combination with fourth-generation enzyme immunoassays (EIA) or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) in clinical settings, according to a study in the journal AIDS.

“These infections are likely to be particularly transmissible due to the high HIV viral load in early infection ... in high-income countries, rapid tests should be used in combination with fourth-generation EIA or NAAT, except in special circumstances,” the Australian researchers said.

They performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 studies involving 110,122 HIV rapid test results. The primary outcome was the test’s sensitivity for detecting acute or established HIV infections. Sensitivity was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed positive rapid tests by the number of confirmed positive comparator tests. Specificity was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed negative rapid tests by the number of negative comparator tests.

Compared with EIA, the estimated sensitivity of rapid tests was 94.5% (95% confidence interval, 87.4-97.7). Compared with NAAT, the sensitivity of rapid tests was 93.7% (95% CI, 88.7-96.5). The sensitivity of rapid tests in high income countries was 85.7% (95% CI, 81.9-88.9), and in low income countries was 97.7% (95% CI, 95.2-98·9), compared with either EIA or NAAT (P less than .01 for difference between settings). Proportions of antibody negative acute infections were 13.6% (95% CI, 10.1-18.0) and 4.7% (95% CI, 2.8-7.7) in studies from high- and low-income countries respectively (P less than .01).

Rapid tests were less sensitive when used in clinical settings in high-income countries, regardless of whether they were compared with a NAAT or fourth-generation EIA. However, the researchers noted that the discrepancy between high- and low-income countries could be attributed to the higher proportion of acute HIV infections (antibody-negative NAAT positive) in populations tested in high-income countries, which might reflect higher background testing rates or a higher incidence of HIV in men who have sex with men.

Read the full study in AIDS (doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001134).

On Twitter @richpizzi

Rapid HIV tests in high-income countries miss about one in seven infections and should be used in combination with fourth-generation enzyme immunoassays (EIA) or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) in clinical settings, according to a study in the journal AIDS.

“These infections are likely to be particularly transmissible due to the high HIV viral load in early infection ... in high-income countries, rapid tests should be used in combination with fourth-generation EIA or NAAT, except in special circumstances,” the Australian researchers said.

They performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 studies involving 110,122 HIV rapid test results. The primary outcome was the test’s sensitivity for detecting acute or established HIV infections. Sensitivity was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed positive rapid tests by the number of confirmed positive comparator tests. Specificity was calculated by dividing the number of confirmed negative rapid tests by the number of negative comparator tests.

Compared with EIA, the estimated sensitivity of rapid tests was 94.5% (95% confidence interval, 87.4-97.7). Compared with NAAT, the sensitivity of rapid tests was 93.7% (95% CI, 88.7-96.5). The sensitivity of rapid tests in high income countries was 85.7% (95% CI, 81.9-88.9), and in low income countries was 97.7% (95% CI, 95.2-98·9), compared with either EIA or NAAT (P less than .01 for difference between settings). Proportions of antibody negative acute infections were 13.6% (95% CI, 10.1-18.0) and 4.7% (95% CI, 2.8-7.7) in studies from high- and low-income countries respectively (P less than .01).

Rapid tests were less sensitive when used in clinical settings in high-income countries, regardless of whether they were compared with a NAAT or fourth-generation EIA. However, the researchers noted that the discrepancy between high- and low-income countries could be attributed to the higher proportion of acute HIV infections (antibody-negative NAAT positive) in populations tested in high-income countries, which might reflect higher background testing rates or a higher incidence of HIV in men who have sex with men.

Read the full study in AIDS (doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001134).

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM AIDS

Better, cheaper test developed to identify BPDs

Investigators from more than 50 institutions across the globe have developed a high-throughput sequencing platform—the ThromboGenomics platform—targeting 63 genes relevant for inherited bleeding, thrombotic, and platelet disorders (BPDs).

The investigators say this platform provides a “comprehensive and cost-effective strategy” to diagnose BPDs and has a high sensitivity to detect and “shortlist” the causal variants when known to be in a BPD gene.

Molecular analysis is often unavailable for patients with BPDs, with the exception of hemophilia and von Willebrand disease, and this causes delays, often inconclusive molecular diagnoses, and compromises treatment.

So to address this unmet diagnostic need, the investigators sequenced 159 and 137 samples from cases with and without previously known causal BPD variants, respectively.

The platform, along with the processing and filtering methods, has a high sensitivity—100% based on the 159 samples with known causal variants.

The investigators report that the sensitivity remains high even when the variants are unknown—greater than 90% based on 61 samples.

The platform’s variant approach also has a high specificity of greater than 99.5% because it reduces the number of candidates requiring consideration.

The ThromboGenomics platform is already being used by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom.

The platform can identify single nucleotide variants, short insertions/deletions, and large copy number variants. They are then subjected to automated filtering and prioritized for diagnosis, resulting in an average of 5.34 candidate variants per individual.

However, the platform cannot identify inversions, and approximately 45% of severe hemophilia A cases are due to inversions. So the investigators recommend that a simple polymerase chain reaction-based test be performed to exclude those cases prior to high-throughput sequencing.

The investigators indicated that during validation of the ThromboGenomics platform, 13 new BPD genes were found.

Use of the platform, they believe, will reduce the diagnostic delay in reaching a conclusive molecular diagnosis for BPD patients.

And further, they believe that “by facilitating provision of a definitive diagnosis, our platform will bring substantial benefits to the estimated 2 million BPD cases worldwide.”

They described the development of the platform in Blood. ![]()

Investigators from more than 50 institutions across the globe have developed a high-throughput sequencing platform—the ThromboGenomics platform—targeting 63 genes relevant for inherited bleeding, thrombotic, and platelet disorders (BPDs).

The investigators say this platform provides a “comprehensive and cost-effective strategy” to diagnose BPDs and has a high sensitivity to detect and “shortlist” the causal variants when known to be in a BPD gene.

Molecular analysis is often unavailable for patients with BPDs, with the exception of hemophilia and von Willebrand disease, and this causes delays, often inconclusive molecular diagnoses, and compromises treatment.

So to address this unmet diagnostic need, the investigators sequenced 159 and 137 samples from cases with and without previously known causal BPD variants, respectively.

The platform, along with the processing and filtering methods, has a high sensitivity—100% based on the 159 samples with known causal variants.

The investigators report that the sensitivity remains high even when the variants are unknown—greater than 90% based on 61 samples.

The platform’s variant approach also has a high specificity of greater than 99.5% because it reduces the number of candidates requiring consideration.

The ThromboGenomics platform is already being used by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom.

The platform can identify single nucleotide variants, short insertions/deletions, and large copy number variants. They are then subjected to automated filtering and prioritized for diagnosis, resulting in an average of 5.34 candidate variants per individual.

However, the platform cannot identify inversions, and approximately 45% of severe hemophilia A cases are due to inversions. So the investigators recommend that a simple polymerase chain reaction-based test be performed to exclude those cases prior to high-throughput sequencing.

The investigators indicated that during validation of the ThromboGenomics platform, 13 new BPD genes were found.

Use of the platform, they believe, will reduce the diagnostic delay in reaching a conclusive molecular diagnosis for BPD patients.

And further, they believe that “by facilitating provision of a definitive diagnosis, our platform will bring substantial benefits to the estimated 2 million BPD cases worldwide.”

They described the development of the platform in Blood. ![]()

Investigators from more than 50 institutions across the globe have developed a high-throughput sequencing platform—the ThromboGenomics platform—targeting 63 genes relevant for inherited bleeding, thrombotic, and platelet disorders (BPDs).

The investigators say this platform provides a “comprehensive and cost-effective strategy” to diagnose BPDs and has a high sensitivity to detect and “shortlist” the causal variants when known to be in a BPD gene.

Molecular analysis is often unavailable for patients with BPDs, with the exception of hemophilia and von Willebrand disease, and this causes delays, often inconclusive molecular diagnoses, and compromises treatment.

So to address this unmet diagnostic need, the investigators sequenced 159 and 137 samples from cases with and without previously known causal BPD variants, respectively.

The platform, along with the processing and filtering methods, has a high sensitivity—100% based on the 159 samples with known causal variants.

The investigators report that the sensitivity remains high even when the variants are unknown—greater than 90% based on 61 samples.

The platform’s variant approach also has a high specificity of greater than 99.5% because it reduces the number of candidates requiring consideration.

The ThromboGenomics platform is already being used by the National Health Service in the United Kingdom.

The platform can identify single nucleotide variants, short insertions/deletions, and large copy number variants. They are then subjected to automated filtering and prioritized for diagnosis, resulting in an average of 5.34 candidate variants per individual.

However, the platform cannot identify inversions, and approximately 45% of severe hemophilia A cases are due to inversions. So the investigators recommend that a simple polymerase chain reaction-based test be performed to exclude those cases prior to high-throughput sequencing.

The investigators indicated that during validation of the ThromboGenomics platform, 13 new BPD genes were found.

Use of the platform, they believe, will reduce the diagnostic delay in reaching a conclusive molecular diagnosis for BPD patients.

And further, they believe that “by facilitating provision of a definitive diagnosis, our platform will bring substantial benefits to the estimated 2 million BPD cases worldwide.”

They described the development of the platform in Blood. ![]()

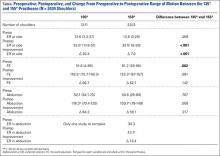

The Effect of Humeral Inclination on Range of Motion in Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review

Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) has become a reliable treatment option for many pathologic conditions of the shoulder, including rotator cuff arthropathy, proximal humerus fractures, and others.1-4 While the treatment outcomes have generally been reported as good, some concern exists over the postoperative range of motion (ROM) in patients following RTSA, including external rotation.5-7 The original RTSA design was introduced by Neer in the 1970s and has undergone many modifications since that time.1,2 The original Grammont-style prosthesis involved medialization of the glenoid, inferiorizing the center of rotation (with increased deltoid tensioning), and a neck-shaft angle of 155°.1,8 While clinical results of the 155° design were encouraging, concerns arose over the significance of the common finding of scapular notching, or contact between the scapular neck and inferior portion of the humeral polyethylene when the arm is adducted.9,10

To address this concern, a prosthesis design with a 135° neck-shaft angle was introduced.11 This new design did significantly decrease the rate of scapular notching, and although some reported a concern over implant stability with the 135° prosthesis, recent data has shown no difference in dislocation rates between the 135° and 155° prostheses.3 A different variable that has not been evaluated between these prostheses is the active ROM that is achieved postoperatively, and the change in ROM from pre- to post-RTSA.12,13 As active ROM plays a significant role in shoulder function and patient satisfaction, the question of whether a significant difference exists in postoperative ROM between the 135° and 155° prostheses must be addressed.

The purpose of this study was to perform a systematic review investigating active ROM following RTSA to determine if active postoperative ROM following RTSA differs between the 135° and 155° humeral inclination prostheses, and to determine if there is a significant difference between the change in preoperative and postoperative ROM between the 135° and 155° prostheses. The authors hypothesize that there will be no significant difference in active postoperative ROM between the 135° and 155° prostheses, and that the difference between preoperative and postoperative ROM (that is, the amount of motion gained by the surgery) will not significantly differ between the 135° and 155° prostheses.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using a PRISMA checklist.15 Systematic review registration was performed using the PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (registration date 3/9/15, registration number CRD42015017367).16 Two reviewers independently conducted the search on March 7, 2015 using the following databases: Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, SportDiscus, and CINAHL. The electronic search citation algorithm utilized was: (((((reverse[Title/Abstract]) AND shoulder[Title/Abstract]) AND arthroplasty[Title/Abstract]) NOT arthroscopic[Title/Abstract]) NOT cadaver[Title/Abstract]) NOT biomechanical[Title/Abstract]. English language Level I-IV evidence (2011 update by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine17) clinical studies that reported the type of RTSA prosthesis that was used as well as postoperative ROM with at least 12 months follow-up were eligible. All references within included studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if missed by the initial search. If duplicate subject publications were discovered, the study with the longer duration of follow-up or larger number of patients was included. Level V evidence reviews, letters to the editor, basic science, biomechanical studies, arthroscopic shoulder surgery, imaging, surgical technique, and classification studies were excluded. Studies were excluded if both a 135° and 155° prosthesis were utilized and the outcomes were not stratified by the humeral inclination. Studies that did not report ROM were excluded.

A total of 456 studies were located, and, after implementation of the exclusion criteria, 65 studies from 2005-2015 were included in the final analysis (Figure). Subjects of interest in this systematic review underwent a RTSA. Studies were not excluded based on the surgical indications (rotator cuff tear arthropathy, proximal humerus fractures, osteoarthritis) and there was no minimum follow-up or rehabilitation requirement. Study and subject demographic parameters analyzed included year of publication, journal of publication, country and continent of publication, years of subject enrollment, presence of study financial conflict of interest, number of subjects and shoulders, gender, age, the manufacturer and type of prosthesis used, and the degree of the humeral inclination (135° vs 155° humeral cup). Preoperative ROM, including forward elevation, abduction, external rotation with the arm adducted, and external rotation with the arm at 90° of abduction, were recorded. The same ROM measurements were recorded for the final follow-up visit that was reported. Internal rotation was recorded, but because of the variability with how this measurement was reported, it was not analyzed. Clinical outcome scores and complications were not assessed. Study methodological quality was evaluated using the Modified Coleman Methodology Score (MCMS).18

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated, including mean ± standard deviation for quantitative continuous data and frequencies with percentages for qualitative categorical data. ROM comparisons between 135° and 155° components (pre- vs postoperative for each and postoperative between the 2) were made using 2 proportion z-test calculator (http://in-silico.net/tools/statistics/ztest) using alpha .05 because of the difference in sample sizes between compared groups.

Results

Sixty-five studies with 3302 patients (3434 shoulders) were included in this study. There was a total of 1211 shoulders in the 135° lateralized glenosphere group and 2223 shoulders in the 155° group. The studies had an average MCMS of 40.4 ± 8.2 (poor), 48% of studies reported a conflict of interest, 32% had no conflict of interest, and 20% did not report whether a conflict of interest existed or not. The majority of studies included were level IV evidence (85%). Mean patient age was 71.1 ± 7.6 years; 29% of patients were male and 71% were female. No significant difference existed between patient age at the time of surgery; the average age of patients in the 135° lateralized glenosphere group was 71.67 ± 3.8 years, while the average patient age of patients in the 155° group was 70.97 ± 8.8 years. Mean follow-up for all patients included in this study was 37.2 ± 16.5 months. Of the 65 studies included, 3 were published from Asia, 4 were published from Australia, 24 were from North America, and 34 were from Europe. Of the individual countries whose studies were included, the United States had 23 included studies, France had 13 included studies, and Italy had 4 included studies. All other countries had <4 studies included.

Patients who received either a 135° or a 155° prosthesis showed significant improvements in external rotation with the arm at the side (P < .05), forward elevation (P < .05), and abduction (P < .05) following surgery (Table). When comparing the 135° and 155° groups, patients who received a 135° prosthesis showed significantly greater improvements in external rotation with the arm at the side (P < .001) and had significantly more overall external rotation postoperatively (P < .001) than patients who received a 155° prosthesis. The only preoperative ROM difference between groups was the 155° group started with significantly more forward elevation than the 135°group prior to surgery (P = .002).

Discussion

RTSA is indicated in patients with rotator cuff tear arthropathy, pseudoparalysis, and a functional deltoid.1,2,4 The purpose of this systematic review was to determine if active ROM following RTSA differs between the 135° and 155° humeral inclination prostheses, and to determine if there is a significant difference between the change in preoperative and postoperative ROM between the 135° and 155° prostheses. Forward elevation, abduction, and external rotation all significantly improved following surgery in both groups, with no significant difference between groups in motion or amount of motion improvement, mostly confirming the study hypotheses. However, patients in the 135° group had significantly greater postoperative external rotation and greater amount of external rotation improvement compared to the 155° group.

Two of the frequently debated issues regarding implant geometry is stability and scapular notching between the 135° and 155° humeral inclination designs. Erickson and colleagues3 recently evaluated the rate of scapular notching and dislocations between the 135° and 155° RTSA prostheses. The authors found that the 135° prosthesis had a significantly lower incidence of scapular notching vs the 155° group and that the rate of dislocations was not significantly different between groups.3 In the latter systematic review, the authors attempted to evaluate ROM between the 135° and 155° prostheses, but as the inclusion criteria of the study was reporting on scapular notching and dislocation rates, many studies reporting solely on ROM were excluded, and the influence of humeral inclination on ROM was inconclusive.3 Furthermore, there have been no studies that have directly compared ROM following RTSA between the 135° and 155° prostheses. While studies evaluating each prosthesis on an individual level have shown an improvement in ROM from pre- to postsurgery, there have been no large studies that have compared the postoperative ROM and change in pre- to postoperative ROM between the 135° and 155° prostheses.11,13,19,20

One study by Valenti and colleagues21 evaluated a group of 30 patients with an average age of 69.5 years who underwent RTSA using either a 135° or a 155° prosthesis. Although the study did not directly compare the 2 types of prostheses, it did report the separate outcomes for each prosthesis. At an average follow-up of 36.4 months, the authors found that patients who had the 135° prosthesis implanted had a mean increase in forward elevation and external rotation of 53° and 9°, while patients who had the 155° showed an increase of 56° in forward elevation and a loss of 1° of external rotation. Both prostheses showed a significant increase in forward elevation, but neither had a significant increase in external rotation. Furthermore, scapular notching was seen in 4 patients in the 155° group, while no patients in the 135° group had evidence of notching.

The results of the current study were similar in that both the 135° and 155° prosthesis showed improvements in forward elevation following surgery, and the 135° group showed a significantly greater gain in external rotation than the 155° group. A significant component of shoulder function and patient satisfaction following RTSA is active ROM. However, this variable has not explicitly been evaluated in the literature until now. The clinical significance of this finding is unclear. Patients with adequate external rotation prior to surgery likely would not see a functional difference between prostheses, while those patients who were borderline on a functional amount of external rotation would see a clinically significant benefit with the 135° prosthesis. Studies have shown that the 135° prosthesis is more anatomic than the 155°, and this could explain the difference seen in ROM outcomes between the 2 prostheses.19 Ladermann and colleagues22 recently created and evaluated a 3-dimensional computer model to evaluate possible differences between the 135° and 155° prosthesis. The authors found a significant increase in external rotation of the 135° compared to the 155°, likely related to a difference in acromiohumeral distance as well as inlay vs onlay humeral trays between the 2 prostheses. The results of this study parallel the computer model, thereby validating these experimental results.

It is important to understand what the minimum functional ROM of the shoulder is (in other words, the ROM necessary to complete activities of daily living (ADLs).23 Namdari and colleagues24 used motion analysis software to evaluate the shoulder ROM necessary to complete 10 different ADLs, including combing hair, washing the back of the opposite shoulder, and reaching a shelf above their head without bending their elbow in 20 patients with a mean age of 29.2 years. They found that patients required 121° ± 6.7° of flexion, 46° ± 5.3° of extension, 128° ± 7.9° of abduction, 116° ± 9.1° of cross-body adduction, 59° ± 10° of external rotation with the arm 90° abducted, and 102° ± 7.7° of internal rotation with the arm at the side (external rotation with the arm at the side was not well defined).24 Hence, while abduction and forward elevation seem comparable, the results from the current study do raise concerns about the amount of external rotation obtained following RTSA as it relates to a patients’ ability to perform ADLs, specifically in the 155° prosthesis, as the average postoperative external rotation in this group was 20.5°. Therefore, based on the results of this study, it appears that, while both the 135° and 155° RTSA prostheses provide similar gain in forward elevation and abduction ROM as well as overall forward elevation and abduction, the 135° prosthesis provides significantly more external rotation with the arm at the side than the 155° prosthesis.

Limitations

Although this study attempted to look at all studies that reported active ROM in patients following a RTSA, and 2 authors performed the search, there is a possibility that some studies were missed, introducing study selection bias. Furthermore, the mean follow-up was over 3 years following surgery, but the minimum follow-up requirement for studies to be included was only 12 months. Hence, this transfer bias introduces the possibility that the patient’s ROM would have changed had they been followed for a standard period of time. There are many variables that come into play in evaluating ROM, and although the study attempted to control for these, there are some that could not be controlled for due to lack of reporting by some studies. Glenosphere size and humeral retroversion were not recorded, as they were not reliably reported in all studies, so motion outcomes based on these variables was not evaluated. Complications and clinical outcomes were not assessed in this review and as such, conclusions regarding these variables cannot be drawn from this study. Finally, indications for surgery were not reliably reported in the studies included in this paper, so differences may have existed between surgical indications of the 135° and 155° groups that could have affected outcomes.

Conclusion

Patients who receive a 135° RTSA gain significantly more external rotation from pre- to postsurgery and have an overall greater amount of external rotation than patients who receive a 155° prosthesis. Both groups show improvements in forward elevation, external rotation, and abduction following surgery.

1. Flatow EL, Harrison AK. A history of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2432-2439.

2. Hyun YS, Huri G, Garbis NG, McFarland EG. Uncommon indications for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5(4):243-255.

3. Erickson BJ, Frank RM, Harris JD, Mall N, Romeo AA. The influence of humeral head inclination in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):988-993.

4. Gupta AK, Harris JD, Erickson BJ, et al. Surgical management of complex proximal humerus fractures--asystematic review of 92 studies including 4500 patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(1):54-59.

5. Feeley BT, Zhang AL, Barry JJ, et al. Decreased scapular notching with lateralization and inferior baseplate placement in reverse shoulder arthroplasty with high humeral inclination. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2014;8(3):65-71.

6. Kiet TK, Feeley BT, Naimark M, et al. Outcomes after shoulder replacement: comparison between reverse and anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(2):179-185.

7. Alentorn-Geli E, Guirro P, Santana F, Torrens C. Treatment of fracture sequelae of the proximal humerus: comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(11):1545-1550.

8. Baulot E, Sirveaux F, Boileau P. Grammont’s idea: The story of Paul Grammont’s functional surgery concept and the development of the reverse principle. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2425-2431.

9. Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. Grammont reversed prosthesis for acute complex fracture of the proximal humerus in an elderly population with 5 to 12 years follow-up. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(1):93-97.

10. Naveed MA, Kitson J, Bunker TD. The Delta III reverse shoulder replacement for cuff tear arthropathy: a single-centre study of 50 consecutive procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):57-61.

11. Levy J, Frankle M, Mighell M, Pupello D. The use of the reverse shoulder prosthesis for the treatment of failed hemiarthroplasty for proximal humeral fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(2):292-300.

12. Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2544-2556.

13. Atalar AC, Salduz A, Cil H, Sungur M, Celik D, Demirhan M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty: radiological and clinical short-term results. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48(1):25-31.

14. Raiss P, Edwards TB, da Silva MR, Bruckner T, Loew M, Walch G. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of nonunions of the surgical neck of the proximal part of the humerus (type-3 fracture sequelae). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(24):2070-2076.

15. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1-e34.

16. The University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews. Available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/. Accessed April 11, 2016.

17. The University of Oxford. Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine. Available at: http://www.cebm.net/. Accessed April 11, 2016

18. Cowan J, Lozano-Calderon S, Ring D. Quality of prospective controlled randomized trials. Analysis of trials of treatment for lateral epicondylitis as an example. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(8):1693-1699.

19. Clark JC, Ritchie J, Song FS, et al. Complication rates, dislocation, pain, and postoperative range of motion after reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with and without repair of the subscapularis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):36-41.

20. Sayana MK, Kakarala G, Bandi S, Wynn-Jones C. Medium term results of reverse total shoulder replacement in patients with rotator cuff arthropathy. Ir J Med Sci. 2009;178(2):147-150.