User login

Method provides more accurate diagnosis of MDS, team says

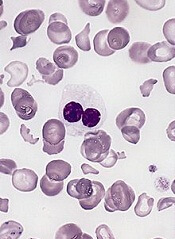

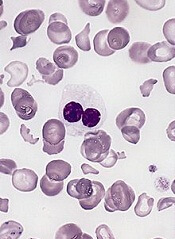

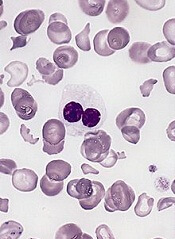

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of cell-free DNA should be the method of choice to confirm the diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), according to researchers.

The team found that using NGS to analyze samples from MDS patients yielded more accurate results than Sanger sequencing.

And sequencing cell-free DNA rather than peripheral blood cell DNA increased the likelihood of detecting mutations associated with MDS.

The team reported these findings in Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. This research was funded by NeoGenomics Laboratories.

For this study, the researchers performed NGS on a panel of 14 target genes using total nucleic acid extracted from the plasma of 16 patients with early MDS (blasts <5%). The team also performed Sanger sequencing and NGS on peripheral blood cell DNA from the same patients.

The researchers found that NGS of cell-free DNA confirmed the diagnosis of MDS in all 16 patients.

In addition, NGS of cell-free DNA revealed abnormalities in 5 patients (31%) that were not detected by Sanger sequencing of peripheral blood cell DNA.

NGS of peripheral blood cell DNA produced the same results as NGS of cell-free DNA for 4 of the 5 patients. However, NGS of peripheral blood cell DNA did not detect a mutation in the RUNX1 gene that was evident in cell-free DNA from 1 patient.

Overall, the researchers found that mutant allele frequency was significantly higher in cell-free DNA than cellular DNA (P=0.008).

The team therefore concluded that cell-free DNA is more reliable than peripheral blood cell DNA for detecting molecular abnormalities in patients with MDS, and NGS is more accurate than Sanger sequencing. ![]()

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of cell-free DNA should be the method of choice to confirm the diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), according to researchers.

The team found that using NGS to analyze samples from MDS patients yielded more accurate results than Sanger sequencing.

And sequencing cell-free DNA rather than peripheral blood cell DNA increased the likelihood of detecting mutations associated with MDS.

The team reported these findings in Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. This research was funded by NeoGenomics Laboratories.

For this study, the researchers performed NGS on a panel of 14 target genes using total nucleic acid extracted from the plasma of 16 patients with early MDS (blasts <5%). The team also performed Sanger sequencing and NGS on peripheral blood cell DNA from the same patients.

The researchers found that NGS of cell-free DNA confirmed the diagnosis of MDS in all 16 patients.

In addition, NGS of cell-free DNA revealed abnormalities in 5 patients (31%) that were not detected by Sanger sequencing of peripheral blood cell DNA.

NGS of peripheral blood cell DNA produced the same results as NGS of cell-free DNA for 4 of the 5 patients. However, NGS of peripheral blood cell DNA did not detect a mutation in the RUNX1 gene that was evident in cell-free DNA from 1 patient.

Overall, the researchers found that mutant allele frequency was significantly higher in cell-free DNA than cellular DNA (P=0.008).

The team therefore concluded that cell-free DNA is more reliable than peripheral blood cell DNA for detecting molecular abnormalities in patients with MDS, and NGS is more accurate than Sanger sequencing. ![]()

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) of cell-free DNA should be the method of choice to confirm the diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), according to researchers.

The team found that using NGS to analyze samples from MDS patients yielded more accurate results than Sanger sequencing.

And sequencing cell-free DNA rather than peripheral blood cell DNA increased the likelihood of detecting mutations associated with MDS.

The team reported these findings in Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. This research was funded by NeoGenomics Laboratories.

For this study, the researchers performed NGS on a panel of 14 target genes using total nucleic acid extracted from the plasma of 16 patients with early MDS (blasts <5%). The team also performed Sanger sequencing and NGS on peripheral blood cell DNA from the same patients.

The researchers found that NGS of cell-free DNA confirmed the diagnosis of MDS in all 16 patients.

In addition, NGS of cell-free DNA revealed abnormalities in 5 patients (31%) that were not detected by Sanger sequencing of peripheral blood cell DNA.

NGS of peripheral blood cell DNA produced the same results as NGS of cell-free DNA for 4 of the 5 patients. However, NGS of peripheral blood cell DNA did not detect a mutation in the RUNX1 gene that was evident in cell-free DNA from 1 patient.

Overall, the researchers found that mutant allele frequency was significantly higher in cell-free DNA than cellular DNA (P=0.008).

The team therefore concluded that cell-free DNA is more reliable than peripheral blood cell DNA for detecting molecular abnormalities in patients with MDS, and NGS is more accurate than Sanger sequencing. ![]()

Docs prescribe drugs despite possible interaction

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Physicians may still prescribe a controversial drug combination despite safety concerns, according to a study published in Pharmacology Research & Perspectives.

Regulatory agencies have warned against prescribing the antiplatelet agent clopidogrel with the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) omeprazole and esomeprazole.

A PPI may be prescribed with clopidogrel to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with antiplatelet therapy.

However, concomitant use of clopidogrel and esomeprazole/omeprazole is thought by some to reduce the pharmacological activity of clopidogrel.

In 2009 and 2010, regulatory agencies in Europe and the US published statements advising against concomitant use of clopidogrel and the aforementioned PPIs.

Willemien J. Kruik-Kolloffel, PharmD, of Medisch Spectrum Twente in Enschede, The Netherlands, and his colleagues wanted to determine if this recommendation was followed in The Netherlands.

The researchers studied data spanning the period from 2008 to 2011 and encompassing 39,496 patients. Forty percent of the patients did not use gastroprotective drugs at all during the study period.

Twenty-seven percent of patients were taking gastroprotective drugs before starting clopidogrel, 23% started gastroprotective drugs and clopidogrel concomitantly, and 10% started gastroprotective drugs at least 4 weeks after starting clopidogrel.

Among the patients who started a gastroprotective drug and clopidogrel concomitantly, an average of 40% started on esomeprazole/omeprazole before the first statement from a regulatory agency was released in January 2009.

This percentage decreased to around 20% after the statements were released. The percentage of patients starting on other PPIs rose from 60% to about 80%.

After the last statement was released in February 2010, there was an 11.9% decrease in dispensation of omeprazole and esomeprazole and an increase of 16.0% for other PPIs.

Results were similar among the patients who started taking a gastroprotective drug at least 4 weeks after starting clopidogrel.

These data suggest the regulatory agencies’ advice was followed, though not fully. The researchers said this may be, in part, because physicians doubt the suggested interaction between clopidogrel and esomeprazole/omeprazole.

“Regulatory agencies should base their advice on sound scientific data to convince prescribers,” Dr Kruik-Kolloffel said. “We, the authors, doubt the interaction, as do a lot of professionals all around the world.” ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Physicians may still prescribe a controversial drug combination despite safety concerns, according to a study published in Pharmacology Research & Perspectives.

Regulatory agencies have warned against prescribing the antiplatelet agent clopidogrel with the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) omeprazole and esomeprazole.

A PPI may be prescribed with clopidogrel to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with antiplatelet therapy.

However, concomitant use of clopidogrel and esomeprazole/omeprazole is thought by some to reduce the pharmacological activity of clopidogrel.

In 2009 and 2010, regulatory agencies in Europe and the US published statements advising against concomitant use of clopidogrel and the aforementioned PPIs.

Willemien J. Kruik-Kolloffel, PharmD, of Medisch Spectrum Twente in Enschede, The Netherlands, and his colleagues wanted to determine if this recommendation was followed in The Netherlands.

The researchers studied data spanning the period from 2008 to 2011 and encompassing 39,496 patients. Forty percent of the patients did not use gastroprotective drugs at all during the study period.

Twenty-seven percent of patients were taking gastroprotective drugs before starting clopidogrel, 23% started gastroprotective drugs and clopidogrel concomitantly, and 10% started gastroprotective drugs at least 4 weeks after starting clopidogrel.

Among the patients who started a gastroprotective drug and clopidogrel concomitantly, an average of 40% started on esomeprazole/omeprazole before the first statement from a regulatory agency was released in January 2009.

This percentage decreased to around 20% after the statements were released. The percentage of patients starting on other PPIs rose from 60% to about 80%.

After the last statement was released in February 2010, there was an 11.9% decrease in dispensation of omeprazole and esomeprazole and an increase of 16.0% for other PPIs.

Results were similar among the patients who started taking a gastroprotective drug at least 4 weeks after starting clopidogrel.

These data suggest the regulatory agencies’ advice was followed, though not fully. The researchers said this may be, in part, because physicians doubt the suggested interaction between clopidogrel and esomeprazole/omeprazole.

“Regulatory agencies should base their advice on sound scientific data to convince prescribers,” Dr Kruik-Kolloffel said. “We, the authors, doubt the interaction, as do a lot of professionals all around the world.” ![]()

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Physicians may still prescribe a controversial drug combination despite safety concerns, according to a study published in Pharmacology Research & Perspectives.

Regulatory agencies have warned against prescribing the antiplatelet agent clopidogrel with the proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) omeprazole and esomeprazole.

A PPI may be prescribed with clopidogrel to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding associated with antiplatelet therapy.

However, concomitant use of clopidogrel and esomeprazole/omeprazole is thought by some to reduce the pharmacological activity of clopidogrel.

In 2009 and 2010, regulatory agencies in Europe and the US published statements advising against concomitant use of clopidogrel and the aforementioned PPIs.

Willemien J. Kruik-Kolloffel, PharmD, of Medisch Spectrum Twente in Enschede, The Netherlands, and his colleagues wanted to determine if this recommendation was followed in The Netherlands.

The researchers studied data spanning the period from 2008 to 2011 and encompassing 39,496 patients. Forty percent of the patients did not use gastroprotective drugs at all during the study period.

Twenty-seven percent of patients were taking gastroprotective drugs before starting clopidogrel, 23% started gastroprotective drugs and clopidogrel concomitantly, and 10% started gastroprotective drugs at least 4 weeks after starting clopidogrel.

Among the patients who started a gastroprotective drug and clopidogrel concomitantly, an average of 40% started on esomeprazole/omeprazole before the first statement from a regulatory agency was released in January 2009.

This percentage decreased to around 20% after the statements were released. The percentage of patients starting on other PPIs rose from 60% to about 80%.

After the last statement was released in February 2010, there was an 11.9% decrease in dispensation of omeprazole and esomeprazole and an increase of 16.0% for other PPIs.

Results were similar among the patients who started taking a gastroprotective drug at least 4 weeks after starting clopidogrel.

These data suggest the regulatory agencies’ advice was followed, though not fully. The researchers said this may be, in part, because physicians doubt the suggested interaction between clopidogrel and esomeprazole/omeprazole.

“Regulatory agencies should base their advice on sound scientific data to convince prescribers,” Dr Kruik-Kolloffel said. “We, the authors, doubt the interaction, as do a lot of professionals all around the world.” ![]()

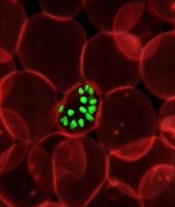

Overcoming drug resistance in malaria

infecting a red blood cell

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

New research helps explain how one of Plasmodium falciparum’s best weapons against antimalarial drugs can actually be exploited to treat malaria.

Investigators believe the findings, published in PLOS Pathogens, might be used to stop the emergence and spread of drug-resistant malaria.

The team noted that mutations in the P falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) confer resistance to

chloroquine and related antimalarial drugs by enabling the protein to transport the drugs away from their targets within the parasite’s digestive vacuole.

However, chloroquine resistance-conferring isoforms of PfCRT (PfCRTCQR) also render the parasite hypersensitive to a subset of structurally diverse drugs. And mutations in PfCRTCQR that suppress this hypersensitivity simultaneously reinstate sensitivity to chloroquine and related drugs.

With this study, the investigators uncovered 2 mechanisms by which PfCRT causes P falciparum to become hypersensitive to antimalarial drugs.

First, they found that quinine, which normally exerts its killing effect within the parasite’s digestive vacuole, can bind tightly to certain forms of PfCRT. This blocks the function of the protein, which is essential to the parasite’s survival.

Second, the team found that amantadine, which normally sequesters within the digestive vacuole as well, is leaked back into the cytosol via PfCRT.

The investigators noted that, in both of these cases, mutations that suppress hypersensitivity also revoke PfCRT’s ability to transport chloroquine, which explains why rescue from hypersensitivity restores the parasite’s sensitivity to chloroquine.

“[C]hanges that allow the protein to move chloroquine away from its antimalarial target simultaneously enable the protein to deliver other drugs to their antimalarial targets,” explained study author Rowena Martin, PhD, of Australian National University in Canberra.

“[W]hen the protein adapts itself to fend off one of these drugs, it is no longer able to deal with chloroquine and, hence, the parasite is re-sensitized to chloroquine. Essentially, the parasite can’t have its cake and eat it too. So if chloroquine or a related drug is paired with a drug that is super-active against the modified protein, no matter what the parasite tries to do, it’s ‘checkmate’ for malaria.”

Dr Martin and her colleagues believe their findings provide a foundation for understanding and exploiting the hypersensitivity of chloroquine-resistant parasites to several antimalarial drugs that are currently available.

“Health authorities could use our research to find ways to prolong the lifespan of antimalarial drugs,” said Sashika Richards, a PhD student at Australian National University.

“The current frontline antimalarial drug, artemisinin, is already failing in Asia, and we don’t have anything to replace it. It will be at least 5 years before the next new drug makes it to market. The low-hanging fruit is gone, and it’s now very costly and time-consuming to develop new treatments for malaria.” ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

New research helps explain how one of Plasmodium falciparum’s best weapons against antimalarial drugs can actually be exploited to treat malaria.

Investigators believe the findings, published in PLOS Pathogens, might be used to stop the emergence and spread of drug-resistant malaria.

The team noted that mutations in the P falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) confer resistance to

chloroquine and related antimalarial drugs by enabling the protein to transport the drugs away from their targets within the parasite’s digestive vacuole.

However, chloroquine resistance-conferring isoforms of PfCRT (PfCRTCQR) also render the parasite hypersensitive to a subset of structurally diverse drugs. And mutations in PfCRTCQR that suppress this hypersensitivity simultaneously reinstate sensitivity to chloroquine and related drugs.

With this study, the investigators uncovered 2 mechanisms by which PfCRT causes P falciparum to become hypersensitive to antimalarial drugs.

First, they found that quinine, which normally exerts its killing effect within the parasite’s digestive vacuole, can bind tightly to certain forms of PfCRT. This blocks the function of the protein, which is essential to the parasite’s survival.

Second, the team found that amantadine, which normally sequesters within the digestive vacuole as well, is leaked back into the cytosol via PfCRT.

The investigators noted that, in both of these cases, mutations that suppress hypersensitivity also revoke PfCRT’s ability to transport chloroquine, which explains why rescue from hypersensitivity restores the parasite’s sensitivity to chloroquine.

“[C]hanges that allow the protein to move chloroquine away from its antimalarial target simultaneously enable the protein to deliver other drugs to their antimalarial targets,” explained study author Rowena Martin, PhD, of Australian National University in Canberra.

“[W]hen the protein adapts itself to fend off one of these drugs, it is no longer able to deal with chloroquine and, hence, the parasite is re-sensitized to chloroquine. Essentially, the parasite can’t have its cake and eat it too. So if chloroquine or a related drug is paired with a drug that is super-active against the modified protein, no matter what the parasite tries to do, it’s ‘checkmate’ for malaria.”

Dr Martin and her colleagues believe their findings provide a foundation for understanding and exploiting the hypersensitivity of chloroquine-resistant parasites to several antimalarial drugs that are currently available.

“Health authorities could use our research to find ways to prolong the lifespan of antimalarial drugs,” said Sashika Richards, a PhD student at Australian National University.

“The current frontline antimalarial drug, artemisinin, is already failing in Asia, and we don’t have anything to replace it. It will be at least 5 years before the next new drug makes it to market. The low-hanging fruit is gone, and it’s now very costly and time-consuming to develop new treatments for malaria.” ![]()

infecting a red blood cell

Photo courtesy of St. Jude

Children’s Research Hospital

New research helps explain how one of Plasmodium falciparum’s best weapons against antimalarial drugs can actually be exploited to treat malaria.

Investigators believe the findings, published in PLOS Pathogens, might be used to stop the emergence and spread of drug-resistant malaria.

The team noted that mutations in the P falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT) confer resistance to

chloroquine and related antimalarial drugs by enabling the protein to transport the drugs away from their targets within the parasite’s digestive vacuole.

However, chloroquine resistance-conferring isoforms of PfCRT (PfCRTCQR) also render the parasite hypersensitive to a subset of structurally diverse drugs. And mutations in PfCRTCQR that suppress this hypersensitivity simultaneously reinstate sensitivity to chloroquine and related drugs.

With this study, the investigators uncovered 2 mechanisms by which PfCRT causes P falciparum to become hypersensitive to antimalarial drugs.

First, they found that quinine, which normally exerts its killing effect within the parasite’s digestive vacuole, can bind tightly to certain forms of PfCRT. This blocks the function of the protein, which is essential to the parasite’s survival.

Second, the team found that amantadine, which normally sequesters within the digestive vacuole as well, is leaked back into the cytosol via PfCRT.

The investigators noted that, in both of these cases, mutations that suppress hypersensitivity also revoke PfCRT’s ability to transport chloroquine, which explains why rescue from hypersensitivity restores the parasite’s sensitivity to chloroquine.

“[C]hanges that allow the protein to move chloroquine away from its antimalarial target simultaneously enable the protein to deliver other drugs to their antimalarial targets,” explained study author Rowena Martin, PhD, of Australian National University in Canberra.

“[W]hen the protein adapts itself to fend off one of these drugs, it is no longer able to deal with chloroquine and, hence, the parasite is re-sensitized to chloroquine. Essentially, the parasite can’t have its cake and eat it too. So if chloroquine or a related drug is paired with a drug that is super-active against the modified protein, no matter what the parasite tries to do, it’s ‘checkmate’ for malaria.”

Dr Martin and her colleagues believe their findings provide a foundation for understanding and exploiting the hypersensitivity of chloroquine-resistant parasites to several antimalarial drugs that are currently available.

“Health authorities could use our research to find ways to prolong the lifespan of antimalarial drugs,” said Sashika Richards, a PhD student at Australian National University.

“The current frontline antimalarial drug, artemisinin, is already failing in Asia, and we don’t have anything to replace it. It will be at least 5 years before the next new drug makes it to market. The low-hanging fruit is gone, and it’s now very costly and time-consuming to develop new treatments for malaria.” ![]()

Serum Vitamin D Levels, Atopy Not Significantly Linked

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Serum vitamin D level was not significantly associated with atopic dermatitis or disease severity in a single-center study of more than 600 children and adolescents.

However, “we did observe a strong correlation between average serum vitamin D levels and skin type, as well as body mass index,” said Kavita Darji, a medical student at Saint Louis (Mo.) University, who presented the findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Those findings challenge the logic of following universal definitions of vitamin D deficiency, especially given the phenotypic heterogeneity of patients in the United States, she added in an interview.

Serum vitamin D testing is one of most common laboratory assays in this country, but clinicians still debate the risks and benefits of supplementing children and adolescents who test below the Endocrine Society’s threshold for sufficiency (30.0 ng/mL).

To identify factors affecting vitamin D levels, Ms. Darji and her associates reviewed electronic medical charts for patients under age 22 years at Saint Louis University medical centers between 2009 and 2014. The cohort of 655 patients was primarily white (64%) or black (29%), and was nearly equally balanced by gender; their average age was 10 years. The researchers analyzed only the first vitamin D serum measurement for each patient, and defined deficiency as a level under 20 ng/mL, insufficiency as a level between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL, and sufficiency as a level of at least 30 ng/mL.

Serum vitamin D levels were slightly lower among atopic patients, compared with those without atopy, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (about 25 ng/mL vs. about 38 ng/mL; P greater than .05). “We also did not find an association between AD severity and vitamin D level,” Ms. Darji reported. Instead, race and body mass index were the most significant predictors of vitamin D deficiency, probably because these factors directly affect cutaneous photo-induced vitamin D synthesis and the sequestration of fat-soluble vitamins in adipose tissue, she said.

Using the standard definitions, more than 50% of black patients were vitamin D deficient, while less than 30% had sufficient vitamin D levels. In contrast, about 25% of white patients were vitamin D deficient, while nearly 40% had sufficient vitamin D levels (P less than .0001 for proportions of deficiency by race). Furthermore, only about 10% of obese children (those who exceeded the 99th percentile of BMI for age) had sufficient vitamin D levels, compared with more than 40% of underweight children and about 30% of normal-weight children (P less than .00001).

Since vitamin D deficiency was more common among black and obese patients, “maybe they could benefit from a different cut-off value than the standard 30 ng per mL that we used,” Ms. Darji said. “The question is, do they really require these supplements? It may be beneficial to look at the unique characteristics of each patient before supplementing, because the risks of supplementation are considerable in terms of bone health and cardiovascular disease.”

Vitamin D levels did not vary significantly by gender or by month or season measured, Ms. Darji noted. She reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Serum vitamin D level was not significantly associated with atopic dermatitis or disease severity in a single-center study of more than 600 children and adolescents.

However, “we did observe a strong correlation between average serum vitamin D levels and skin type, as well as body mass index,” said Kavita Darji, a medical student at Saint Louis (Mo.) University, who presented the findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Those findings challenge the logic of following universal definitions of vitamin D deficiency, especially given the phenotypic heterogeneity of patients in the United States, she added in an interview.

Serum vitamin D testing is one of most common laboratory assays in this country, but clinicians still debate the risks and benefits of supplementing children and adolescents who test below the Endocrine Society’s threshold for sufficiency (30.0 ng/mL).

To identify factors affecting vitamin D levels, Ms. Darji and her associates reviewed electronic medical charts for patients under age 22 years at Saint Louis University medical centers between 2009 and 2014. The cohort of 655 patients was primarily white (64%) or black (29%), and was nearly equally balanced by gender; their average age was 10 years. The researchers analyzed only the first vitamin D serum measurement for each patient, and defined deficiency as a level under 20 ng/mL, insufficiency as a level between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL, and sufficiency as a level of at least 30 ng/mL.

Serum vitamin D levels were slightly lower among atopic patients, compared with those without atopy, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (about 25 ng/mL vs. about 38 ng/mL; P greater than .05). “We also did not find an association between AD severity and vitamin D level,” Ms. Darji reported. Instead, race and body mass index were the most significant predictors of vitamin D deficiency, probably because these factors directly affect cutaneous photo-induced vitamin D synthesis and the sequestration of fat-soluble vitamins in adipose tissue, she said.

Using the standard definitions, more than 50% of black patients were vitamin D deficient, while less than 30% had sufficient vitamin D levels. In contrast, about 25% of white patients were vitamin D deficient, while nearly 40% had sufficient vitamin D levels (P less than .0001 for proportions of deficiency by race). Furthermore, only about 10% of obese children (those who exceeded the 99th percentile of BMI for age) had sufficient vitamin D levels, compared with more than 40% of underweight children and about 30% of normal-weight children (P less than .00001).

Since vitamin D deficiency was more common among black and obese patients, “maybe they could benefit from a different cut-off value than the standard 30 ng per mL that we used,” Ms. Darji said. “The question is, do they really require these supplements? It may be beneficial to look at the unique characteristics of each patient before supplementing, because the risks of supplementation are considerable in terms of bone health and cardiovascular disease.”

Vitamin D levels did not vary significantly by gender or by month or season measured, Ms. Darji noted. She reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Serum vitamin D level was not significantly associated with atopic dermatitis or disease severity in a single-center study of more than 600 children and adolescents.

However, “we did observe a strong correlation between average serum vitamin D levels and skin type, as well as body mass index,” said Kavita Darji, a medical student at Saint Louis (Mo.) University, who presented the findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Those findings challenge the logic of following universal definitions of vitamin D deficiency, especially given the phenotypic heterogeneity of patients in the United States, she added in an interview.

Serum vitamin D testing is one of most common laboratory assays in this country, but clinicians still debate the risks and benefits of supplementing children and adolescents who test below the Endocrine Society’s threshold for sufficiency (30.0 ng/mL).

To identify factors affecting vitamin D levels, Ms. Darji and her associates reviewed electronic medical charts for patients under age 22 years at Saint Louis University medical centers between 2009 and 2014. The cohort of 655 patients was primarily white (64%) or black (29%), and was nearly equally balanced by gender; their average age was 10 years. The researchers analyzed only the first vitamin D serum measurement for each patient, and defined deficiency as a level under 20 ng/mL, insufficiency as a level between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL, and sufficiency as a level of at least 30 ng/mL.

Serum vitamin D levels were slightly lower among atopic patients, compared with those without atopy, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (about 25 ng/mL vs. about 38 ng/mL; P greater than .05). “We also did not find an association between AD severity and vitamin D level,” Ms. Darji reported. Instead, race and body mass index were the most significant predictors of vitamin D deficiency, probably because these factors directly affect cutaneous photo-induced vitamin D synthesis and the sequestration of fat-soluble vitamins in adipose tissue, she said.

Using the standard definitions, more than 50% of black patients were vitamin D deficient, while less than 30% had sufficient vitamin D levels. In contrast, about 25% of white patients were vitamin D deficient, while nearly 40% had sufficient vitamin D levels (P less than .0001 for proportions of deficiency by race). Furthermore, only about 10% of obese children (those who exceeded the 99th percentile of BMI for age) had sufficient vitamin D levels, compared with more than 40% of underweight children and about 30% of normal-weight children (P less than .00001).

Since vitamin D deficiency was more common among black and obese patients, “maybe they could benefit from a different cut-off value than the standard 30 ng per mL that we used,” Ms. Darji said. “The question is, do they really require these supplements? It may be beneficial to look at the unique characteristics of each patient before supplementing, because the risks of supplementation are considerable in terms of bone health and cardiovascular disease.”

Vitamin D levels did not vary significantly by gender or by month or season measured, Ms. Darji noted. She reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Serum vitamin D levels, atopy not significantly linked

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Serum vitamin D level was not significantly associated with atopic dermatitis or disease severity in a single-center study of more than 600 children and adolescents.

However, “we did observe a strong correlation between average serum vitamin D levels and skin type, as well as body mass index,” said Kavita Darji, a medical student at Saint Louis (Mo.) University, who presented the findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Those findings challenge the logic of following universal definitions of vitamin D deficiency, especially given the phenotypic heterogeneity of patients in the United States, she added in an interview.

Serum vitamin D testing is one of most common laboratory assays in this country, but clinicians still debate the risks and benefits of supplementing children and adolescents who test below the Endocrine Society’s threshold for sufficiency (30.0 ng/mL).

To identify factors affecting vitamin D levels, Ms. Darji and her associates reviewed electronic medical charts for patients under age 22 years at Saint Louis University medical centers between 2009 and 2014. The cohort of 655 patients was primarily white (64%) or black (29%), and was nearly equally balanced by gender; their average age was 10 years. The researchers analyzed only the first vitamin D serum measurement for each patient, and defined deficiency as a level under 20 ng/mL, insufficiency as a level between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL, and sufficiency as a level of at least 30 ng/mL.

Serum vitamin D levels were slightly lower among atopic patients, compared with those without atopy, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (about 25 ng/mL vs. about 38 ng/mL; P greater than .05). “We also did not find an association between AD severity and vitamin D level,” Ms. Darji reported. Instead, race and body mass index were the most significant predictors of vitamin D deficiency, probably because these factors directly affect cutaneous photo-induced vitamin D synthesis and the sequestration of fat-soluble vitamins in adipose tissue, she said.

Using the standard definitions, more than 50% of black patients were vitamin D deficient, while less than 30% had sufficient vitamin D levels. In contrast, about 25% of white patients were vitamin D deficient, while nearly 40% had sufficient vitamin D levels (P less than .0001 for proportions of deficiency by race). Furthermore, only about 10% of obese children (those who exceeded the 99th percentile of BMI for age) had sufficient vitamin D levels, compared with more than 40% of underweight children and about 30% of normal-weight children (P less than .00001).

Since vitamin D deficiency was more common among black and obese patients, “maybe they could benefit from a different cut-off value than the standard 30 ng per mL that we used,” Ms. Darji said. “The question is, do they really require these supplements? It may be beneficial to look at the unique characteristics of each patient before supplementing, because the risks of supplementation are considerable in terms of bone health and cardiovascular disease.”

Vitamin D levels did not vary significantly by gender or by month or season measured, Ms. Darji noted. She reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Serum vitamin D level was not significantly associated with atopic dermatitis or disease severity in a single-center study of more than 600 children and adolescents.

However, “we did observe a strong correlation between average serum vitamin D levels and skin type, as well as body mass index,” said Kavita Darji, a medical student at Saint Louis (Mo.) University, who presented the findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Those findings challenge the logic of following universal definitions of vitamin D deficiency, especially given the phenotypic heterogeneity of patients in the United States, she added in an interview.

Serum vitamin D testing is one of most common laboratory assays in this country, but clinicians still debate the risks and benefits of supplementing children and adolescents who test below the Endocrine Society’s threshold for sufficiency (30.0 ng/mL).

To identify factors affecting vitamin D levels, Ms. Darji and her associates reviewed electronic medical charts for patients under age 22 years at Saint Louis University medical centers between 2009 and 2014. The cohort of 655 patients was primarily white (64%) or black (29%), and was nearly equally balanced by gender; their average age was 10 years. The researchers analyzed only the first vitamin D serum measurement for each patient, and defined deficiency as a level under 20 ng/mL, insufficiency as a level between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL, and sufficiency as a level of at least 30 ng/mL.

Serum vitamin D levels were slightly lower among atopic patients, compared with those without atopy, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (about 25 ng/mL vs. about 38 ng/mL; P greater than .05). “We also did not find an association between AD severity and vitamin D level,” Ms. Darji reported. Instead, race and body mass index were the most significant predictors of vitamin D deficiency, probably because these factors directly affect cutaneous photo-induced vitamin D synthesis and the sequestration of fat-soluble vitamins in adipose tissue, she said.

Using the standard definitions, more than 50% of black patients were vitamin D deficient, while less than 30% had sufficient vitamin D levels. In contrast, about 25% of white patients were vitamin D deficient, while nearly 40% had sufficient vitamin D levels (P less than .0001 for proportions of deficiency by race). Furthermore, only about 10% of obese children (those who exceeded the 99th percentile of BMI for age) had sufficient vitamin D levels, compared with more than 40% of underweight children and about 30% of normal-weight children (P less than .00001).

Since vitamin D deficiency was more common among black and obese patients, “maybe they could benefit from a different cut-off value than the standard 30 ng per mL that we used,” Ms. Darji said. “The question is, do they really require these supplements? It may be beneficial to look at the unique characteristics of each patient before supplementing, because the risks of supplementation are considerable in terms of bone health and cardiovascular disease.”

Vitamin D levels did not vary significantly by gender or by month or season measured, Ms. Darji noted. She reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Serum vitamin D level was not significantly associated with atopic dermatitis or disease severity in a single-center study of more than 600 children and adolescents.

However, “we did observe a strong correlation between average serum vitamin D levels and skin type, as well as body mass index,” said Kavita Darji, a medical student at Saint Louis (Mo.) University, who presented the findings in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Those findings challenge the logic of following universal definitions of vitamin D deficiency, especially given the phenotypic heterogeneity of patients in the United States, she added in an interview.

Serum vitamin D testing is one of most common laboratory assays in this country, but clinicians still debate the risks and benefits of supplementing children and adolescents who test below the Endocrine Society’s threshold for sufficiency (30.0 ng/mL).

To identify factors affecting vitamin D levels, Ms. Darji and her associates reviewed electronic medical charts for patients under age 22 years at Saint Louis University medical centers between 2009 and 2014. The cohort of 655 patients was primarily white (64%) or black (29%), and was nearly equally balanced by gender; their average age was 10 years. The researchers analyzed only the first vitamin D serum measurement for each patient, and defined deficiency as a level under 20 ng/mL, insufficiency as a level between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL, and sufficiency as a level of at least 30 ng/mL.

Serum vitamin D levels were slightly lower among atopic patients, compared with those without atopy, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (about 25 ng/mL vs. about 38 ng/mL; P greater than .05). “We also did not find an association between AD severity and vitamin D level,” Ms. Darji reported. Instead, race and body mass index were the most significant predictors of vitamin D deficiency, probably because these factors directly affect cutaneous photo-induced vitamin D synthesis and the sequestration of fat-soluble vitamins in adipose tissue, she said.

Using the standard definitions, more than 50% of black patients were vitamin D deficient, while less than 30% had sufficient vitamin D levels. In contrast, about 25% of white patients were vitamin D deficient, while nearly 40% had sufficient vitamin D levels (P less than .0001 for proportions of deficiency by race). Furthermore, only about 10% of obese children (those who exceeded the 99th percentile of BMI for age) had sufficient vitamin D levels, compared with more than 40% of underweight children and about 30% of normal-weight children (P less than .00001).

Since vitamin D deficiency was more common among black and obese patients, “maybe they could benefit from a different cut-off value than the standard 30 ng per mL that we used,” Ms. Darji said. “The question is, do they really require these supplements? It may be beneficial to look at the unique characteristics of each patient before supplementing, because the risks of supplementation are considerable in terms of bone health and cardiovascular disease.”

Vitamin D levels did not vary significantly by gender or by month or season measured, Ms. Darji noted. She reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

AT THE 2016 SID ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Serum vitamin D was not a significant marker for pediatric atopic dermatitis or disease severity.

Major finding: The average serum vitamin D level was lower among patients with atopic dermatitis than healthy children, but the difference did not reach statistical significance.

Data source: A single-center retrospective review of electronic medical records from 655 patients aged 21 years and younger (average age, 10 years).

Disclosures: Ms. Darji reported no funding sources and had no disclosures.

MCIs and the Orlando Nightclub Shooting

While most Americans were still reacting in horror and disbelief to news of a mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida in the early morning hours of June 12, 2016, the thoughts of most emergency physicians (EPs) were probably focused on the ongoing efforts to save as many victims as possible: What was the closest Level 1 trauma center, and how deep was the ED staffing there that night? Was there a need for additional resources, and perhaps even, could they get there in time to help? In this issue of Emergency Medicine (EM), Residency Program Director Salvatore Silvestri, MD, and his emergency medicine colleagues masterfully recount events from that night as they unfolded, both at the scene and two blocks away at the Orlando Regional Medical Center (ORMC) ED, in the minutes and hours following the first reported shootings.

Being prepared for a mass-casualty incident (MCI) is an extraordinarily expensive requirement of a hospital: It must acquire and maintain adequate resources and communication capabilities; periodically perform unannounced drills that disrupt other hospital activities; and ensure that all EPs and staff are not only able to perform their own day-to-day roles as attending physicians, residents, nurses, etc, but are also capable of taking on even greater responsibilities during an MCI—depending on the day and time it occurs. As you will read in the pages that follow, in the early morning hours of June 12, many of the practiced exercises and rehearsed procedures proved useful, even life-saving, while others had to be discarded or ignored in favor of improvised solutions to rapidly transport and treat the large number of victims with unanticipated needs, under unique conditions.

In any MCI, saving the largest number of victims invariably depends on rapidly instituting some deviations from standard operating procedures (SOPs) and standards of care (SOCs). As described by the ORMC EP authors, “...law enforcement vehicles and ambulances would make the two-block drive from the scene to ORMC carrying as many patients as they safely could, and return immediately after offload….minimal interventions were performed and unlike standard procedure, EMS could offer no prearrival report to the hospital.”

Deviations from SOPs and SOCs during an MCI are not confined to prehospital care, but often extend into the ED and beyond. Most difficult for an EP participating in an MCI is the moment of realization that the sheer number of seriously injured and dying patients arriving en masse mandates a change from “ED triage” to “battlefield triage.” As Dr Ponder recalled, “One of the first few patients I saw was pulseless, and as I went to start chest compressions, I was stopped by a trauma surgeon who said, ‘He’s gone, focus on the ones we can help.’”

In EDs, dying patients are attended to first with extensive staff and resources, while, as a result, less seriously ill patients must sometimes wait longer for care. The opposite is true on the battlefield, where near-death victims of lethal injuries are provided only with comfort care, at most, in order to save those who have a chance of surviving their extensive or serious injuries.

For hospitals and staff, the costs incurred by disaster preparedness are great and invariably exceed government funding provided for these efforts, but how much greater would be the human toll from an MCI without such efforts? All EPs should be proud of what our colleagues at ORMC accomplished on June 12. Though most EPs may never have to deal directly with an MCI, the Orlando nightclub shooting incident was only one of the latest MCIs, certainly not one of the last.

Previous editorials on MCIs may be found in EM September 2006 (9/11), June 2011 (first responders), September 2011 (9/11), November 2011 (surge capacity), and September 2012 (surge capacity/Hurricane Sandy).

While most Americans were still reacting in horror and disbelief to news of a mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida in the early morning hours of June 12, 2016, the thoughts of most emergency physicians (EPs) were probably focused on the ongoing efforts to save as many victims as possible: What was the closest Level 1 trauma center, and how deep was the ED staffing there that night? Was there a need for additional resources, and perhaps even, could they get there in time to help? In this issue of Emergency Medicine (EM), Residency Program Director Salvatore Silvestri, MD, and his emergency medicine colleagues masterfully recount events from that night as they unfolded, both at the scene and two blocks away at the Orlando Regional Medical Center (ORMC) ED, in the minutes and hours following the first reported shootings.

Being prepared for a mass-casualty incident (MCI) is an extraordinarily expensive requirement of a hospital: It must acquire and maintain adequate resources and communication capabilities; periodically perform unannounced drills that disrupt other hospital activities; and ensure that all EPs and staff are not only able to perform their own day-to-day roles as attending physicians, residents, nurses, etc, but are also capable of taking on even greater responsibilities during an MCI—depending on the day and time it occurs. As you will read in the pages that follow, in the early morning hours of June 12, many of the practiced exercises and rehearsed procedures proved useful, even life-saving, while others had to be discarded or ignored in favor of improvised solutions to rapidly transport and treat the large number of victims with unanticipated needs, under unique conditions.

In any MCI, saving the largest number of victims invariably depends on rapidly instituting some deviations from standard operating procedures (SOPs) and standards of care (SOCs). As described by the ORMC EP authors, “...law enforcement vehicles and ambulances would make the two-block drive from the scene to ORMC carrying as many patients as they safely could, and return immediately after offload….minimal interventions were performed and unlike standard procedure, EMS could offer no prearrival report to the hospital.”

Deviations from SOPs and SOCs during an MCI are not confined to prehospital care, but often extend into the ED and beyond. Most difficult for an EP participating in an MCI is the moment of realization that the sheer number of seriously injured and dying patients arriving en masse mandates a change from “ED triage” to “battlefield triage.” As Dr Ponder recalled, “One of the first few patients I saw was pulseless, and as I went to start chest compressions, I was stopped by a trauma surgeon who said, ‘He’s gone, focus on the ones we can help.’”

In EDs, dying patients are attended to first with extensive staff and resources, while, as a result, less seriously ill patients must sometimes wait longer for care. The opposite is true on the battlefield, where near-death victims of lethal injuries are provided only with comfort care, at most, in order to save those who have a chance of surviving their extensive or serious injuries.

For hospitals and staff, the costs incurred by disaster preparedness are great and invariably exceed government funding provided for these efforts, but how much greater would be the human toll from an MCI without such efforts? All EPs should be proud of what our colleagues at ORMC accomplished on June 12. Though most EPs may never have to deal directly with an MCI, the Orlando nightclub shooting incident was only one of the latest MCIs, certainly not one of the last.

Previous editorials on MCIs may be found in EM September 2006 (9/11), June 2011 (first responders), September 2011 (9/11), November 2011 (surge capacity), and September 2012 (surge capacity/Hurricane Sandy).

While most Americans were still reacting in horror and disbelief to news of a mass shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida in the early morning hours of June 12, 2016, the thoughts of most emergency physicians (EPs) were probably focused on the ongoing efforts to save as many victims as possible: What was the closest Level 1 trauma center, and how deep was the ED staffing there that night? Was there a need for additional resources, and perhaps even, could they get there in time to help? In this issue of Emergency Medicine (EM), Residency Program Director Salvatore Silvestri, MD, and his emergency medicine colleagues masterfully recount events from that night as they unfolded, both at the scene and two blocks away at the Orlando Regional Medical Center (ORMC) ED, in the minutes and hours following the first reported shootings.

Being prepared for a mass-casualty incident (MCI) is an extraordinarily expensive requirement of a hospital: It must acquire and maintain adequate resources and communication capabilities; periodically perform unannounced drills that disrupt other hospital activities; and ensure that all EPs and staff are not only able to perform their own day-to-day roles as attending physicians, residents, nurses, etc, but are also capable of taking on even greater responsibilities during an MCI—depending on the day and time it occurs. As you will read in the pages that follow, in the early morning hours of June 12, many of the practiced exercises and rehearsed procedures proved useful, even life-saving, while others had to be discarded or ignored in favor of improvised solutions to rapidly transport and treat the large number of victims with unanticipated needs, under unique conditions.

In any MCI, saving the largest number of victims invariably depends on rapidly instituting some deviations from standard operating procedures (SOPs) and standards of care (SOCs). As described by the ORMC EP authors, “...law enforcement vehicles and ambulances would make the two-block drive from the scene to ORMC carrying as many patients as they safely could, and return immediately after offload….minimal interventions were performed and unlike standard procedure, EMS could offer no prearrival report to the hospital.”

Deviations from SOPs and SOCs during an MCI are not confined to prehospital care, but often extend into the ED and beyond. Most difficult for an EP participating in an MCI is the moment of realization that the sheer number of seriously injured and dying patients arriving en masse mandates a change from “ED triage” to “battlefield triage.” As Dr Ponder recalled, “One of the first few patients I saw was pulseless, and as I went to start chest compressions, I was stopped by a trauma surgeon who said, ‘He’s gone, focus on the ones we can help.’”

In EDs, dying patients are attended to first with extensive staff and resources, while, as a result, less seriously ill patients must sometimes wait longer for care. The opposite is true on the battlefield, where near-death victims of lethal injuries are provided only with comfort care, at most, in order to save those who have a chance of surviving their extensive or serious injuries.

For hospitals and staff, the costs incurred by disaster preparedness are great and invariably exceed government funding provided for these efforts, but how much greater would be the human toll from an MCI without such efforts? All EPs should be proud of what our colleagues at ORMC accomplished on June 12. Though most EPs may never have to deal directly with an MCI, the Orlando nightclub shooting incident was only one of the latest MCIs, certainly not one of the last.

Previous editorials on MCIs may be found in EM September 2006 (9/11), June 2011 (first responders), September 2011 (9/11), November 2011 (surge capacity), and September 2012 (surge capacity/Hurricane Sandy).

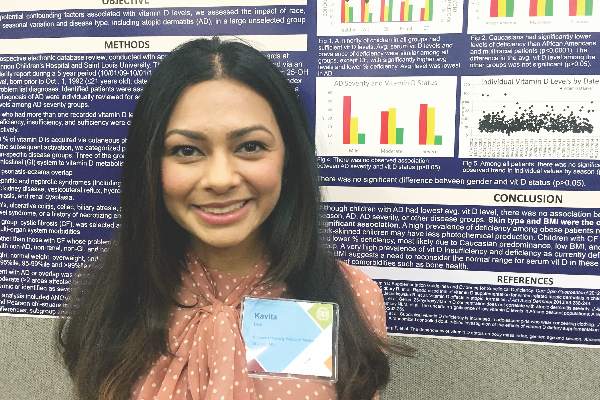

Pediatric Dermatology Consult - August 2016

Dr. Catalina Matiz and David Ginsberg describe the diagnosis and treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus in children.

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a relatively common form of chronic cutaneous lupus, although its presentation in children is rare. The typical presentation of DLE is well-circumscribed, indurated, sometimes scaly round or oval plaques with pigmentary change, often red to purple in color. DLE also is clinically associated with telangiectasia, scarring, and follicular plugging, which has a characteristic appearance of “carpet tacking” beneath the scale.

When left untreated, these lesions may result in areas of long-term hypo- or hyperpigmentation, as well as atrophy and scarring.1 These cutaneous manifestations often are exacerbated by UV light exposure. This is particularly problematic because DLE most often affects the face, although lesions also can be found on the scalp, ears, trunk, extremities, and in the mouth as well.

Currently, there are few studies looking specifically at DLE in children and, based on the studies that have been done, there appear to be several important differences between the adult and pediatric populations. DLE affects women more than twice as much as men in the adult population, but reports vary as to whether this female predominance carries over to affected children.2,3 Adults with DLE rarely have a family history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with rates reported between 1% and 4.4%. In children, however, the reported rates of family history increase tenfold to 11%-40%.2

One study showed that children with DLE progress to SLE at a rate of 23.5%-26%, which is higher than reported rates in adults of 5%-20%.2,4 For this reason, repeated laboratory studies are essential in the follow-up of children diagnosed with DLE, given the possibility of a transition to systemic disease, particularly within the first year of diagnosis. Disseminated lesions can be a red flag for future progression to SLE.2

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of infiltrated annular lesions on the face and ears should include conditions such as tinea faciae, seborrheic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, sarcoidosis, and leishmaniasis. When the lesions are present on the ear or nose, as in the case of this patient, relapsing polychonritis also may be considered.

Although histology plays a large part in diagnosing DLE, clinical presentation and recognizing the need for a biopsy are important.5 Tinea faciei, a fungal infection of the face, can present as erythematous scaly plaques.6 A thorough history and physical exam are important in differentiating tinea faciei from DLE because the former often begins as a small scaly papule that annularly expands outward to form larger plaque with scale around the outer rim, as opposed to DLE, which may have an adherent scale across the entire plaque.5 A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation of scraped scale from one of the lesions or a fungal culture can confirm the diagnosis of tinea faciei.6

Seborrheic dermatitis can be localized to the face and scalp and presents with greasy yellow scales. Early lesions of DLE can be difficult to differentiate from seborrheic dermatitis.

Infiltrated annular lesions on the face may represent granulomatous conditions such as granuloma annulare or sarcoidosis, but these lesions usually lack the presence of scale that can be seen in DLE.

Relapsing polychondritis presents as intermittent episodes of cartilage inflammation, usually affecting the cartilage of the ear, nose, and respiratory tract. Areas affected do not show changes on the surface of the skin as it occurs in DLE lesions.

As mentioned above, family history of SLE could indicate a potential for DLE in a small percentage of patients, but the clinical feature of the scaly plaques with the carpet tacking underneath the scale, caused by follicular plugging, is helpful in making the diagnosis clinically. Ultimately, the best way to differentiate anything resembling DLE is through histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histologic findings in DLE include epidermal atrophy, basal membrane cell vacuolization, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, corneal plugs, pseudoscysts, and acanthosis.3 The lupus band test is done using DIF and is a widely used tool for making the diagnosis of DLE based on the distribution of immunoglobulin deposition in the basement membrane zone.7

Treatment

Without timely diagnosis and treatment of DLE, the lesions can progress to scarring and atrophy, leading to a decreased quality of life. UV light exposure and smoking can exacerbate DLE, so sun protection and smoking cessation are both recommended in patients with DLE, although, admittedly, the latter is less relevant in the pediatric population.1 Topical, intralesional, or systemic corticosteroids, with or without antimalarials, are the first line therapy for the management of DLE.1 For refractory cases, some reports document the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors, dapsone, methotrexate, and topical or systemic retinoids.1 For severe cases, intravenous immunoglobulin, ustekinumab, and rituximab also may be used.1

References

- Dermatol Ther. 2016 Apr 12 Epub.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;25(2):163-7.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2003 Mar-Apr;20(2):103-7.

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr;72(4):628-33.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Mar-Apr;33(2):200-8.

- Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):443-55.

- Am J Dermatopathol. 2016 Feb;38(2):121-3.

Dr. Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego–University of California, San Diego, and Mr. Ginsberg is a research associate at the hospital. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Ginsberg said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Catalina Matiz and David Ginsberg describe the diagnosis and treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus in children.

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a relatively common form of chronic cutaneous lupus, although its presentation in children is rare. The typical presentation of DLE is well-circumscribed, indurated, sometimes scaly round or oval plaques with pigmentary change, often red to purple in color. DLE also is clinically associated with telangiectasia, scarring, and follicular plugging, which has a characteristic appearance of “carpet tacking” beneath the scale.

When left untreated, these lesions may result in areas of long-term hypo- or hyperpigmentation, as well as atrophy and scarring.1 These cutaneous manifestations often are exacerbated by UV light exposure. This is particularly problematic because DLE most often affects the face, although lesions also can be found on the scalp, ears, trunk, extremities, and in the mouth as well.

Currently, there are few studies looking specifically at DLE in children and, based on the studies that have been done, there appear to be several important differences between the adult and pediatric populations. DLE affects women more than twice as much as men in the adult population, but reports vary as to whether this female predominance carries over to affected children.2,3 Adults with DLE rarely have a family history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with rates reported between 1% and 4.4%. In children, however, the reported rates of family history increase tenfold to 11%-40%.2

One study showed that children with DLE progress to SLE at a rate of 23.5%-26%, which is higher than reported rates in adults of 5%-20%.2,4 For this reason, repeated laboratory studies are essential in the follow-up of children diagnosed with DLE, given the possibility of a transition to systemic disease, particularly within the first year of diagnosis. Disseminated lesions can be a red flag for future progression to SLE.2

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of infiltrated annular lesions on the face and ears should include conditions such as tinea faciae, seborrheic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, sarcoidosis, and leishmaniasis. When the lesions are present on the ear or nose, as in the case of this patient, relapsing polychonritis also may be considered.

Although histology plays a large part in diagnosing DLE, clinical presentation and recognizing the need for a biopsy are important.5 Tinea faciei, a fungal infection of the face, can present as erythematous scaly plaques.6 A thorough history and physical exam are important in differentiating tinea faciei from DLE because the former often begins as a small scaly papule that annularly expands outward to form larger plaque with scale around the outer rim, as opposed to DLE, which may have an adherent scale across the entire plaque.5 A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation of scraped scale from one of the lesions or a fungal culture can confirm the diagnosis of tinea faciei.6

Seborrheic dermatitis can be localized to the face and scalp and presents with greasy yellow scales. Early lesions of DLE can be difficult to differentiate from seborrheic dermatitis.

Infiltrated annular lesions on the face may represent granulomatous conditions such as granuloma annulare or sarcoidosis, but these lesions usually lack the presence of scale that can be seen in DLE.

Relapsing polychondritis presents as intermittent episodes of cartilage inflammation, usually affecting the cartilage of the ear, nose, and respiratory tract. Areas affected do not show changes on the surface of the skin as it occurs in DLE lesions.

As mentioned above, family history of SLE could indicate a potential for DLE in a small percentage of patients, but the clinical feature of the scaly plaques with the carpet tacking underneath the scale, caused by follicular plugging, is helpful in making the diagnosis clinically. Ultimately, the best way to differentiate anything resembling DLE is through histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histologic findings in DLE include epidermal atrophy, basal membrane cell vacuolization, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, corneal plugs, pseudoscysts, and acanthosis.3 The lupus band test is done using DIF and is a widely used tool for making the diagnosis of DLE based on the distribution of immunoglobulin deposition in the basement membrane zone.7

Treatment

Without timely diagnosis and treatment of DLE, the lesions can progress to scarring and atrophy, leading to a decreased quality of life. UV light exposure and smoking can exacerbate DLE, so sun protection and smoking cessation are both recommended in patients with DLE, although, admittedly, the latter is less relevant in the pediatric population.1 Topical, intralesional, or systemic corticosteroids, with or without antimalarials, are the first line therapy for the management of DLE.1 For refractory cases, some reports document the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors, dapsone, methotrexate, and topical or systemic retinoids.1 For severe cases, intravenous immunoglobulin, ustekinumab, and rituximab also may be used.1

References

- Dermatol Ther. 2016 Apr 12 Epub.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;25(2):163-7.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2003 Mar-Apr;20(2):103-7.

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr;72(4):628-33.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Mar-Apr;33(2):200-8.

- Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):443-55.

- Am J Dermatopathol. 2016 Feb;38(2):121-3.

Dr. Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego–University of California, San Diego, and Mr. Ginsberg is a research associate at the hospital. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Ginsberg said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Dr. Catalina Matiz and David Ginsberg describe the diagnosis and treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus in children.

Discoid lupus erythematosus

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) is a relatively common form of chronic cutaneous lupus, although its presentation in children is rare. The typical presentation of DLE is well-circumscribed, indurated, sometimes scaly round or oval plaques with pigmentary change, often red to purple in color. DLE also is clinically associated with telangiectasia, scarring, and follicular plugging, which has a characteristic appearance of “carpet tacking” beneath the scale.

When left untreated, these lesions may result in areas of long-term hypo- or hyperpigmentation, as well as atrophy and scarring.1 These cutaneous manifestations often are exacerbated by UV light exposure. This is particularly problematic because DLE most often affects the face, although lesions also can be found on the scalp, ears, trunk, extremities, and in the mouth as well.

Currently, there are few studies looking specifically at DLE in children and, based on the studies that have been done, there appear to be several important differences between the adult and pediatric populations. DLE affects women more than twice as much as men in the adult population, but reports vary as to whether this female predominance carries over to affected children.2,3 Adults with DLE rarely have a family history of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with rates reported between 1% and 4.4%. In children, however, the reported rates of family history increase tenfold to 11%-40%.2

One study showed that children with DLE progress to SLE at a rate of 23.5%-26%, which is higher than reported rates in adults of 5%-20%.2,4 For this reason, repeated laboratory studies are essential in the follow-up of children diagnosed with DLE, given the possibility of a transition to systemic disease, particularly within the first year of diagnosis. Disseminated lesions can be a red flag for future progression to SLE.2

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of infiltrated annular lesions on the face and ears should include conditions such as tinea faciae, seborrheic dermatitis, granuloma annulare, cutaneous lymphoma, sarcoidosis, and leishmaniasis. When the lesions are present on the ear or nose, as in the case of this patient, relapsing polychonritis also may be considered.

Although histology plays a large part in diagnosing DLE, clinical presentation and recognizing the need for a biopsy are important.5 Tinea faciei, a fungal infection of the face, can present as erythematous scaly plaques.6 A thorough history and physical exam are important in differentiating tinea faciei from DLE because the former often begins as a small scaly papule that annularly expands outward to form larger plaque with scale around the outer rim, as opposed to DLE, which may have an adherent scale across the entire plaque.5 A potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation of scraped scale from one of the lesions or a fungal culture can confirm the diagnosis of tinea faciei.6

Seborrheic dermatitis can be localized to the face and scalp and presents with greasy yellow scales. Early lesions of DLE can be difficult to differentiate from seborrheic dermatitis.

Infiltrated annular lesions on the face may represent granulomatous conditions such as granuloma annulare or sarcoidosis, but these lesions usually lack the presence of scale that can be seen in DLE.

Relapsing polychondritis presents as intermittent episodes of cartilage inflammation, usually affecting the cartilage of the ear, nose, and respiratory tract. Areas affected do not show changes on the surface of the skin as it occurs in DLE lesions.

As mentioned above, family history of SLE could indicate a potential for DLE in a small percentage of patients, but the clinical feature of the scaly plaques with the carpet tacking underneath the scale, caused by follicular plugging, is helpful in making the diagnosis clinically. Ultimately, the best way to differentiate anything resembling DLE is through histology and direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Histologic findings in DLE include epidermal atrophy, basal membrane cell vacuolization, hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, corneal plugs, pseudoscysts, and acanthosis.3 The lupus band test is done using DIF and is a widely used tool for making the diagnosis of DLE based on the distribution of immunoglobulin deposition in the basement membrane zone.7

Treatment

Without timely diagnosis and treatment of DLE, the lesions can progress to scarring and atrophy, leading to a decreased quality of life. UV light exposure and smoking can exacerbate DLE, so sun protection and smoking cessation are both recommended in patients with DLE, although, admittedly, the latter is less relevant in the pediatric population.1 Topical, intralesional, or systemic corticosteroids, with or without antimalarials, are the first line therapy for the management of DLE.1 For refractory cases, some reports document the use of topical calcineurin inhibitors, dapsone, methotrexate, and topical or systemic retinoids.1 For severe cases, intravenous immunoglobulin, ustekinumab, and rituximab also may be used.1

References

- Dermatol Ther. 2016 Apr 12 Epub.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2008 Mar-Apr;25(2):163-7.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2003 Mar-Apr;20(2):103-7.

- J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015 Apr;72(4):628-33.

- Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Mar-Apr;33(2):200-8.

- Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Apr;61(2):443-55.

- Am J Dermatopathol. 2016 Feb;38(2):121-3.

Dr. Matiz is assistant professor of dermatology at Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego–University of California, San Diego, and Mr. Ginsberg is a research associate at the hospital. Dr. Matiz and Mr. Ginsberg said they have no relevant financial disclosures.

The patient is a well-appearing adolescent in no acute distress, but complaining of continued mild pain of her ear. Upon inspection, she has pink and violaceous indurated annular plaques on her right nasal sidewall and cheek. There is a pink edematous plaque on her right helix and an indurated plaque on the left upper cutaneous lip. The lesions are limited to her face, with no scalp or oral mucosal involvement. Her nails and hair are unaffected.

Testosterone might counteract chemotherapy heart damage

SEATTLE – Adjunct testosterone improved short-term cardiac function in head, neck, and cervical cancer patients undergoing standard treatment in a small randomized trial from the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The finding suggests that testosterone might counteract the cardiotoxic effects of chemotherapy, reducing “the incidence of chemotherapy-induced remodeling. It might also have rehabilitation implications and make patients better surgical candidates. Further investigation is warranted,” said investigator Albert Chamberlain, MD, an endocrine research fellow at the university. Although the results were positive, follow-up was short; years-long data are needed to know if testosterone really protects the heart from chemotherapy damage.

Dr. Chamberlain’s team looked into the issue because “many current chemotherapy drug classes have cardiotoxicity that progresses subclinically for a long time” before problems emerge. “Testosterone is known to cause vasodilation in both large and resistance arteries,” which might help prevent damage. “With that in mind, we decided to” investigate testosterone’s impact on cardiac performance during chemotherapy, he said at the International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer, held by the American Head and Neck Society.

Five women and one man were randomized to weekly intramuscular 100 mg testosterone injections for 7 weeks; six men and four women were randomized to placebo injections. They were all recently diagnosed with stage IIIB, IV, or recurrent head and neck cancer, or cervical cancer, and were undergoing concomitant standard-of-care chemotherapy or chemoradiation. Cardiac function was measured blindly by transthoracic echocardiogram at baseline and the end of the study.

The testosterone group had significantly improved stroke volumes (+18.2% versus –2.6%, P = 0.01), ejection fractions (+6.2% versus –1.8%, P = 0.02), and cardiac output (+1402.2 mL/min versus –16.8mL/min, P = 0.011). Heart rate, arterial pressure, end-diastolic volume, and end-systolic volume remained unchanged in both groups, so the improved systolic function was attributed to reduced vascular resistance in the testosterone group (–26.5% versus +3.9% in the placebo group, P = 0.001).

Systolic improvements remained as cardiac index increased 27.6% in the testosterone group versus 2.8% in the placebo group. Testosterone didn’t seem to have any negative impacts on diastolic function. A placebo patient had a stroke, but there were no other adverse events in the study.

Although improved stroke volume is likely due to the reduced afterload, “increased contractility cannot be eliminated as a potential contributing factor. End diastolic volume remained unchanged in both groups, [suggesting] that preload is unlikely to be the mechanism for increased stroke volume,” Dr. Chamberlain said.

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Chamberlain reported having no relevant disclosures.

|

Dr. Benjamin Judson |

The data are promising but preliminary for a problem we see a lot, chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity that presents years after treatment. We have to be really careful before we give testosterone to anyone who is under active treatment for cancer, because I don’t think we really know if it’s safe.

Benjamin Judson, MD, is an associate professor of otolaryngologic surgery at Yale Medical School in New Haven, Conn. He moderated Dr. Chamberlain’s talk and was not involved in the study.

|

Dr. Benjamin Judson |

The data are promising but preliminary for a problem we see a lot, chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity that presents years after treatment. We have to be really careful before we give testosterone to anyone who is under active treatment for cancer, because I don’t think we really know if it’s safe.

Benjamin Judson, MD, is an associate professor of otolaryngologic surgery at Yale Medical School in New Haven, Conn. He moderated Dr. Chamberlain’s talk and was not involved in the study.

|

Dr. Benjamin Judson |

The data are promising but preliminary for a problem we see a lot, chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity that presents years after treatment. We have to be really careful before we give testosterone to anyone who is under active treatment for cancer, because I don’t think we really know if it’s safe.

Benjamin Judson, MD, is an associate professor of otolaryngologic surgery at Yale Medical School in New Haven, Conn. He moderated Dr. Chamberlain’s talk and was not involved in the study.

SEATTLE – Adjunct testosterone improved short-term cardiac function in head, neck, and cervical cancer patients undergoing standard treatment in a small randomized trial from the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

The finding suggests that testosterone might counteract the cardiotoxic effects of chemotherapy, reducing “the incidence of chemotherapy-induced remodeling. It might also have rehabilitation implications and make patients better surgical candidates. Further investigation is warranted,” said investigator Albert Chamberlain, MD, an endocrine research fellow at the university. Although the results were positive, follow-up was short; years-long data are needed to know if testosterone really protects the heart from chemotherapy damage.

Dr. Chamberlain’s team looked into the issue because “many current chemotherapy drug classes have cardiotoxicity that progresses subclinically for a long time” before problems emerge. “Testosterone is known to cause vasodilation in both large and resistance arteries,” which might help prevent damage. “With that in mind, we decided to” investigate testosterone’s impact on cardiac performance during chemotherapy, he said at the International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer, held by the American Head and Neck Society.