User login

Coming your way ... MIPS

In this column, I will return to the topic of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new payment program, currently scheduled to go into effect January 2017. The QPP has two tracks, the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Again, it is widely expected that for the first several years of the program, the vast majority of surgeons will participate in the QPP via the MIPS track.

To briefly review from the July edition of this column, MIPS consists of four components:

1) Quality.

2) Resource Use.

3) Advancing Care Information (ACI).

4) Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA).

The Quality component replaces the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Resource Use component replaces the Value-Based Modifier (VBM), the Advancing Care Information (ACI) component replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program and is proposed to simplify the program by modifying requirements. The fourth component of MIPS, the Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA), is new.

MIPS participants will be assigned a Composite Performance Score based on their performance in all four components. As proposed for 2017, 50% of the MIPS Composite Performance Score will be based on performance in the Quality component, 25% will be based on the ACI component, 15% will be based on the CPIA, and 10% will be based on Resource Use. Thus, 75% of one’s score will be determined by performance in the Quality and ACI components. With that in mind, the remainder of this month’s column will be dedicated to the ACI with next month’s column focusing on the Quality component.

The Advancing Care Component (ACI)

As discussed above, the ACI component modifies and replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. As currently proposed, (and subject to change with release of the final rule in early November 2016), the score for ACI will be derived in two parts: a base score (50 points) and a performance score.

The threshold for achieving the base score remains an “all or nothing” proposition. Achieving the threshold is based upon reporting a yes/no statement OR the appropriate numerator and denominator for each measure, as required, for the following six objectives:

1) Protect Patient Health Information.

2) Electronic Prescribing.

3) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

4) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

5) Health Information Exchange.

6) Public Health and Clinical Data Reporting.

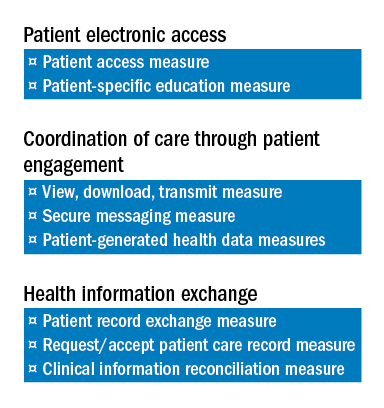

Only after meeting the requirements for the base score is one eligible to receive additional performance score credit based on the level of performance on a subset of three of the objectives required to achieve the base score. Those three are:

1) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

2) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

3) Health Information Exchange

There are a total of eight measures for these three objectives.

The two measures specific to the Patient Electronic Access objective are:

a) Patient Access Measure.

b) Patient-Specific Education Measure.

Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement is assessed based upon the following three measures:

a) View, Download, Transmit Measure.

b) Secure Messaging Measure.

c) Patient-Generated Health Data Measures.

For the Health Information Exchange objective, assessment is also based on three measures. They are:

a) Patient Record Exchange Measure.

b) Request/Accept Patient Care Record Measure.

c) Clinical Information Reconciliation Measure.

Scoring for each of these eight measures is based upon reporting both a numerator and denominator, thus facilitating the calculation of percentage score to which a point value is assigned. For example, a performance rate of 85 on one of the listed measures would earn 8.5 points toward the performance score. The sum of the points accumulated for these eight measures is added to Threshold Score to determine the final score for ACI. Again, 25% of one’s MIPS Composite Score is derived from performance in the ACI component.

It warrants repeating and re-emphasis that the above information is subject to modification pending the release of the MIPS Final Rule, expected in early November.

As mentioned above, the Quality component of MIPS replaces the PQRS. Quality assessment will comprise 50% of the MIPS Composite Score. In next month’s column, I will provide an outline of the changes CMS is proposing for the Quality assessment. As a preview, some good news can be found in the fact that the current MIPS Quality component proposal will require providers to report on a total of six measures as opposed to the previous PQRS requirement to report on nine.

Until next month …

In this column, I will return to the topic of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new payment program, currently scheduled to go into effect January 2017. The QPP has two tracks, the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Again, it is widely expected that for the first several years of the program, the vast majority of surgeons will participate in the QPP via the MIPS track.

To briefly review from the July edition of this column, MIPS consists of four components:

1) Quality.

2) Resource Use.

3) Advancing Care Information (ACI).

4) Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA).

The Quality component replaces the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Resource Use component replaces the Value-Based Modifier (VBM), the Advancing Care Information (ACI) component replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program and is proposed to simplify the program by modifying requirements. The fourth component of MIPS, the Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA), is new.

MIPS participants will be assigned a Composite Performance Score based on their performance in all four components. As proposed for 2017, 50% of the MIPS Composite Performance Score will be based on performance in the Quality component, 25% will be based on the ACI component, 15% will be based on the CPIA, and 10% will be based on Resource Use. Thus, 75% of one’s score will be determined by performance in the Quality and ACI components. With that in mind, the remainder of this month’s column will be dedicated to the ACI with next month’s column focusing on the Quality component.

The Advancing Care Component (ACI)

As discussed above, the ACI component modifies and replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. As currently proposed, (and subject to change with release of the final rule in early November 2016), the score for ACI will be derived in two parts: a base score (50 points) and a performance score.

The threshold for achieving the base score remains an “all or nothing” proposition. Achieving the threshold is based upon reporting a yes/no statement OR the appropriate numerator and denominator for each measure, as required, for the following six objectives:

1) Protect Patient Health Information.

2) Electronic Prescribing.

3) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

4) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

5) Health Information Exchange.

6) Public Health and Clinical Data Reporting.

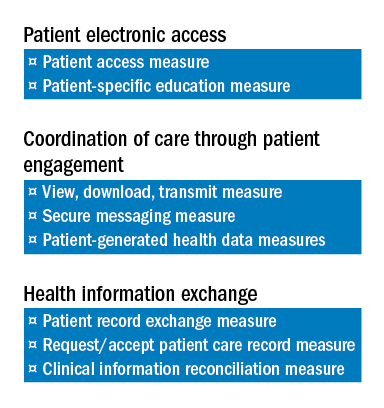

Only after meeting the requirements for the base score is one eligible to receive additional performance score credit based on the level of performance on a subset of three of the objectives required to achieve the base score. Those three are:

1) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

2) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

3) Health Information Exchange

There are a total of eight measures for these three objectives.

The two measures specific to the Patient Electronic Access objective are:

a) Patient Access Measure.

b) Patient-Specific Education Measure.

Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement is assessed based upon the following three measures:

a) View, Download, Transmit Measure.

b) Secure Messaging Measure.

c) Patient-Generated Health Data Measures.

For the Health Information Exchange objective, assessment is also based on three measures. They are:

a) Patient Record Exchange Measure.

b) Request/Accept Patient Care Record Measure.

c) Clinical Information Reconciliation Measure.

Scoring for each of these eight measures is based upon reporting both a numerator and denominator, thus facilitating the calculation of percentage score to which a point value is assigned. For example, a performance rate of 85 on one of the listed measures would earn 8.5 points toward the performance score. The sum of the points accumulated for these eight measures is added to Threshold Score to determine the final score for ACI. Again, 25% of one’s MIPS Composite Score is derived from performance in the ACI component.

It warrants repeating and re-emphasis that the above information is subject to modification pending the release of the MIPS Final Rule, expected in early November.

As mentioned above, the Quality component of MIPS replaces the PQRS. Quality assessment will comprise 50% of the MIPS Composite Score. In next month’s column, I will provide an outline of the changes CMS is proposing for the Quality assessment. As a preview, some good news can be found in the fact that the current MIPS Quality component proposal will require providers to report on a total of six measures as opposed to the previous PQRS requirement to report on nine.

Until next month …

In this column, I will return to the topic of the Quality Payment Program (QPP), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ new payment program, currently scheduled to go into effect January 2017. The QPP has two tracks, the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APMs). Again, it is widely expected that for the first several years of the program, the vast majority of surgeons will participate in the QPP via the MIPS track.

To briefly review from the July edition of this column, MIPS consists of four components:

1) Quality.

2) Resource Use.

3) Advancing Care Information (ACI).

4) Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA).

The Quality component replaces the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), the Resource Use component replaces the Value-Based Modifier (VBM), the Advancing Care Information (ACI) component replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program and is proposed to simplify the program by modifying requirements. The fourth component of MIPS, the Clinical Practice Improvement Activities (CPIA), is new.

MIPS participants will be assigned a Composite Performance Score based on their performance in all four components. As proposed for 2017, 50% of the MIPS Composite Performance Score will be based on performance in the Quality component, 25% will be based on the ACI component, 15% will be based on the CPIA, and 10% will be based on Resource Use. Thus, 75% of one’s score will be determined by performance in the Quality and ACI components. With that in mind, the remainder of this month’s column will be dedicated to the ACI with next month’s column focusing on the Quality component.

The Advancing Care Component (ACI)

As discussed above, the ACI component modifies and replaces the Electronic Health Record Meaningful Use (EHR-MU) program. As currently proposed, (and subject to change with release of the final rule in early November 2016), the score for ACI will be derived in two parts: a base score (50 points) and a performance score.

The threshold for achieving the base score remains an “all or nothing” proposition. Achieving the threshold is based upon reporting a yes/no statement OR the appropriate numerator and denominator for each measure, as required, for the following six objectives:

1) Protect Patient Health Information.

2) Electronic Prescribing.

3) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

4) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

5) Health Information Exchange.

6) Public Health and Clinical Data Reporting.

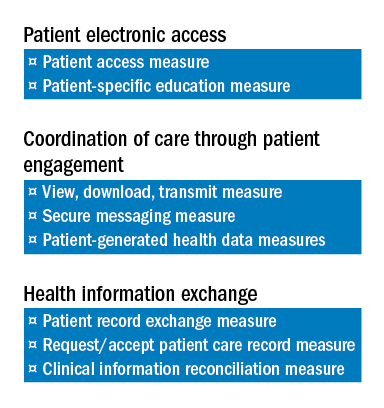

Only after meeting the requirements for the base score is one eligible to receive additional performance score credit based on the level of performance on a subset of three of the objectives required to achieve the base score. Those three are:

1) Patient Electronic Access to Health Information.

2) Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement.

3) Health Information Exchange

There are a total of eight measures for these three objectives.

The two measures specific to the Patient Electronic Access objective are:

a) Patient Access Measure.

b) Patient-Specific Education Measure.

Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement is assessed based upon the following three measures:

a) View, Download, Transmit Measure.

b) Secure Messaging Measure.

c) Patient-Generated Health Data Measures.

For the Health Information Exchange objective, assessment is also based on three measures. They are:

a) Patient Record Exchange Measure.

b) Request/Accept Patient Care Record Measure.

c) Clinical Information Reconciliation Measure.

Scoring for each of these eight measures is based upon reporting both a numerator and denominator, thus facilitating the calculation of percentage score to which a point value is assigned. For example, a performance rate of 85 on one of the listed measures would earn 8.5 points toward the performance score. The sum of the points accumulated for these eight measures is added to Threshold Score to determine the final score for ACI. Again, 25% of one’s MIPS Composite Score is derived from performance in the ACI component.

It warrants repeating and re-emphasis that the above information is subject to modification pending the release of the MIPS Final Rule, expected in early November.

As mentioned above, the Quality component of MIPS replaces the PQRS. Quality assessment will comprise 50% of the MIPS Composite Score. In next month’s column, I will provide an outline of the changes CMS is proposing for the Quality assessment. As a preview, some good news can be found in the fact that the current MIPS Quality component proposal will require providers to report on a total of six measures as opposed to the previous PQRS requirement to report on nine.

Until next month …

Accredited bariatric surgery centers have fewer postoperative complications

A recent review of published medical studies indicates that patients who have weight loss operations at nonaccredited bariatric surgery facilities in the United States are up to 1.4 times more likely to experience serious postoperative complications and more than twice as likely to die after the procedure in comparison with patients who undergo these procedures at accredited bariatric surgery centers. The study authors also report that accredited bariatric centers have lower costs than do nonaccredited centers. These results, which are posted on the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS) website in advance of print publication, represent the first comprehensive review of the best available evidence comparing bariatric surgery results in accredited U.S. centers with outcomes at nonaccredited U.S. centers.

“A preponderance of scientific evidence demonstrates that bariatric surgery becomes safer with accreditation of the surgical center,” said principal investigator John Morton, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, chief of bariatric and minimally invasive surgery at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “Accreditation makes a big difference.” The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgeons (ASMBS) merged their accreditation programs in 2012 to create the unified Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, and more than 700 centers in the country now hold this accreditation. This credential signifies that a surgical facility has met rigorous standards for high-quality surgical care.

Reducing the odds of complications

In their review article, Dr. Morton and first author Dan Azagury, MD, also a bariatric and general surgeon at Stanford, included 13 studies published between 2009 and 2014, comprising more than 1.5 million patients. Dr. Morton acknowledged that a number of patients might be duplicates because some studies used the same national database.

Eight of 11 studies that evaluated postoperative complications found that undergoing a bariatric operation in an accredited facility reduced the odds of experiencing a serious complication by 9 percent to 39 percent (odds ratios of 1.09 to 1.39), the researchers reported. The difference was reportedly even more pronounced for the risk of death occurring in the hospital or up to 90 days postoperatively. Six of eight studies that reported mortality showed that the odds of dying after a bariatric procedure, while low at an accredited center, were 2.26 to 3.57 times higher at a nonaccredited facility.

Nearly all the studies used risk adjustment, which compensates for different levels of patient risk and which experts believe makes results more accurate. Only three studies (23 percent) failed to show a significant benefit of accreditation.

Reducing costs

Drs. Morton and Azagury also analyzed studies that reported average hospital charges and found lower costs at accredited centers. “Accredited bariatric surgical centers provide not only safer care but also less expensive care,” Dr. Morton said. A systematic review was the best way to study this issue, according to Dr. Morton. He said most insurers today will not cover surgical care at nonaccredited bariatric centers, making it difficult to perform a randomized controlled clinical trial. In 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) stopped requiring Medicare beneficiaries to undergo bariatric operations at accredited bariatric centers as a condition of coverage.

Meanwhile, a growing number of patients are choosing surgical treatment for obesity – widely considered the most effective long-term weight-loss therapy. An estimated 179,000 patients underwent gastric bypass, gastric banding, and other bariatric operations in 2013 compared with 158,000 two years earlier, according to the ASMBS.

“These results provide important information that can be used to guide future policy decisions. Perhaps CMS should revisit this policy again,” Dr. Morton suggested.

Read the JACS article at www.journalacs.org/article/S1072-7515(16)30267-8/fulltext.

A recent review of published medical studies indicates that patients who have weight loss operations at nonaccredited bariatric surgery facilities in the United States are up to 1.4 times more likely to experience serious postoperative complications and more than twice as likely to die after the procedure in comparison with patients who undergo these procedures at accredited bariatric surgery centers. The study authors also report that accredited bariatric centers have lower costs than do nonaccredited centers. These results, which are posted on the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS) website in advance of print publication, represent the first comprehensive review of the best available evidence comparing bariatric surgery results in accredited U.S. centers with outcomes at nonaccredited U.S. centers.

“A preponderance of scientific evidence demonstrates that bariatric surgery becomes safer with accreditation of the surgical center,” said principal investigator John Morton, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, chief of bariatric and minimally invasive surgery at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “Accreditation makes a big difference.” The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgeons (ASMBS) merged their accreditation programs in 2012 to create the unified Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, and more than 700 centers in the country now hold this accreditation. This credential signifies that a surgical facility has met rigorous standards for high-quality surgical care.

Reducing the odds of complications

In their review article, Dr. Morton and first author Dan Azagury, MD, also a bariatric and general surgeon at Stanford, included 13 studies published between 2009 and 2014, comprising more than 1.5 million patients. Dr. Morton acknowledged that a number of patients might be duplicates because some studies used the same national database.

Eight of 11 studies that evaluated postoperative complications found that undergoing a bariatric operation in an accredited facility reduced the odds of experiencing a serious complication by 9 percent to 39 percent (odds ratios of 1.09 to 1.39), the researchers reported. The difference was reportedly even more pronounced for the risk of death occurring in the hospital or up to 90 days postoperatively. Six of eight studies that reported mortality showed that the odds of dying after a bariatric procedure, while low at an accredited center, were 2.26 to 3.57 times higher at a nonaccredited facility.

Nearly all the studies used risk adjustment, which compensates for different levels of patient risk and which experts believe makes results more accurate. Only three studies (23 percent) failed to show a significant benefit of accreditation.

Reducing costs

Drs. Morton and Azagury also analyzed studies that reported average hospital charges and found lower costs at accredited centers. “Accredited bariatric surgical centers provide not only safer care but also less expensive care,” Dr. Morton said. A systematic review was the best way to study this issue, according to Dr. Morton. He said most insurers today will not cover surgical care at nonaccredited bariatric centers, making it difficult to perform a randomized controlled clinical trial. In 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) stopped requiring Medicare beneficiaries to undergo bariatric operations at accredited bariatric centers as a condition of coverage.

Meanwhile, a growing number of patients are choosing surgical treatment for obesity – widely considered the most effective long-term weight-loss therapy. An estimated 179,000 patients underwent gastric bypass, gastric banding, and other bariatric operations in 2013 compared with 158,000 two years earlier, according to the ASMBS.

“These results provide important information that can be used to guide future policy decisions. Perhaps CMS should revisit this policy again,” Dr. Morton suggested.

Read the JACS article at www.journalacs.org/article/S1072-7515(16)30267-8/fulltext.

A recent review of published medical studies indicates that patients who have weight loss operations at nonaccredited bariatric surgery facilities in the United States are up to 1.4 times more likely to experience serious postoperative complications and more than twice as likely to die after the procedure in comparison with patients who undergo these procedures at accredited bariatric surgery centers. The study authors also report that accredited bariatric centers have lower costs than do nonaccredited centers. These results, which are posted on the Journal of the American College of Surgeons (JACS) website in advance of print publication, represent the first comprehensive review of the best available evidence comparing bariatric surgery results in accredited U.S. centers with outcomes at nonaccredited U.S. centers.

“A preponderance of scientific evidence demonstrates that bariatric surgery becomes safer with accreditation of the surgical center,” said principal investigator John Morton, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, chief of bariatric and minimally invasive surgery at Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “Accreditation makes a big difference.” The American College of Surgeons (ACS) and the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgeons (ASMBS) merged their accreditation programs in 2012 to create the unified Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program, and more than 700 centers in the country now hold this accreditation. This credential signifies that a surgical facility has met rigorous standards for high-quality surgical care.

Reducing the odds of complications

In their review article, Dr. Morton and first author Dan Azagury, MD, also a bariatric and general surgeon at Stanford, included 13 studies published between 2009 and 2014, comprising more than 1.5 million patients. Dr. Morton acknowledged that a number of patients might be duplicates because some studies used the same national database.

Eight of 11 studies that evaluated postoperative complications found that undergoing a bariatric operation in an accredited facility reduced the odds of experiencing a serious complication by 9 percent to 39 percent (odds ratios of 1.09 to 1.39), the researchers reported. The difference was reportedly even more pronounced for the risk of death occurring in the hospital or up to 90 days postoperatively. Six of eight studies that reported mortality showed that the odds of dying after a bariatric procedure, while low at an accredited center, were 2.26 to 3.57 times higher at a nonaccredited facility.

Nearly all the studies used risk adjustment, which compensates for different levels of patient risk and which experts believe makes results more accurate. Only three studies (23 percent) failed to show a significant benefit of accreditation.

Reducing costs

Drs. Morton and Azagury also analyzed studies that reported average hospital charges and found lower costs at accredited centers. “Accredited bariatric surgical centers provide not only safer care but also less expensive care,” Dr. Morton said. A systematic review was the best way to study this issue, according to Dr. Morton. He said most insurers today will not cover surgical care at nonaccredited bariatric centers, making it difficult to perform a randomized controlled clinical trial. In 2013, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) stopped requiring Medicare beneficiaries to undergo bariatric operations at accredited bariatric centers as a condition of coverage.

Meanwhile, a growing number of patients are choosing surgical treatment for obesity – widely considered the most effective long-term weight-loss therapy. An estimated 179,000 patients underwent gastric bypass, gastric banding, and other bariatric operations in 2013 compared with 158,000 two years earlier, according to the ASMBS.

“These results provide important information that can be used to guide future policy decisions. Perhaps CMS should revisit this policy again,” Dr. Morton suggested.

Read the JACS article at www.journalacs.org/article/S1072-7515(16)30267-8/fulltext.

TQIP now in all 50 states and Washington, D.C.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) is now in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. The ACS TQIP program reached this milestone on Aug. 2 with the addition of Meritus Medical Center in Hagerstown, Md., a Level III TQIP Site.

The TQIP pilot program began in 2009 with 23 centers, and the full TQIP program launched in 2010 with 65 centers. In 2014, Pediatric TQIP was added, and on July 1 of this year, Level III TQIP was launched. TQIP now has 561 enrolled sites (420 Level I and II Adult Sites, 40 Level III Sites, and 101 Pediatric Sites) and anticipates continued growth this year.

TQIP standardizes the collection and measurement of trauma data to generate quality improvement strategies and reduce disparities in trauma care nationwide. TQIP collects data from trauma centers, provides feedback about center performance, and identifies institutional improvements for better patient outcomes. TQIP provides hospitals with risk-adjusted benchmarking for accurate national comparisons. In addition, TQIP provides education and training to help trauma center staff improve the quality of their data and accurately interpret their benchmark reports. The program fosters clinical improvements with the support of Best Practice Guidelines (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/best-practice), which allow enrolled centers to network and share best practice information at the TQIP annual meeting (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/meeting) through the TQIP Google group (https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/trauma-quality-improvement-program---tqip), and in Web conferences.

For more information, visit the TQIP website (www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip).

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) is now in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. The ACS TQIP program reached this milestone on Aug. 2 with the addition of Meritus Medical Center in Hagerstown, Md., a Level III TQIP Site.

The TQIP pilot program began in 2009 with 23 centers, and the full TQIP program launched in 2010 with 65 centers. In 2014, Pediatric TQIP was added, and on July 1 of this year, Level III TQIP was launched. TQIP now has 561 enrolled sites (420 Level I and II Adult Sites, 40 Level III Sites, and 101 Pediatric Sites) and anticipates continued growth this year.

TQIP standardizes the collection and measurement of trauma data to generate quality improvement strategies and reduce disparities in trauma care nationwide. TQIP collects data from trauma centers, provides feedback about center performance, and identifies institutional improvements for better patient outcomes. TQIP provides hospitals with risk-adjusted benchmarking for accurate national comparisons. In addition, TQIP provides education and training to help trauma center staff improve the quality of their data and accurately interpret their benchmark reports. The program fosters clinical improvements with the support of Best Practice Guidelines (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/best-practice), which allow enrolled centers to network and share best practice information at the TQIP annual meeting (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/meeting) through the TQIP Google group (https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/trauma-quality-improvement-program---tqip), and in Web conferences.

For more information, visit the TQIP website (www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip).

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) is now in all 50 states and Washington, D.C. The ACS TQIP program reached this milestone on Aug. 2 with the addition of Meritus Medical Center in Hagerstown, Md., a Level III TQIP Site.

The TQIP pilot program began in 2009 with 23 centers, and the full TQIP program launched in 2010 with 65 centers. In 2014, Pediatric TQIP was added, and on July 1 of this year, Level III TQIP was launched. TQIP now has 561 enrolled sites (420 Level I and II Adult Sites, 40 Level III Sites, and 101 Pediatric Sites) and anticipates continued growth this year.

TQIP standardizes the collection and measurement of trauma data to generate quality improvement strategies and reduce disparities in trauma care nationwide. TQIP collects data from trauma centers, provides feedback about center performance, and identifies institutional improvements for better patient outcomes. TQIP provides hospitals with risk-adjusted benchmarking for accurate national comparisons. In addition, TQIP provides education and training to help trauma center staff improve the quality of their data and accurately interpret their benchmark reports. The program fosters clinical improvements with the support of Best Practice Guidelines (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/best-practice), which allow enrolled centers to network and share best practice information at the TQIP annual meeting (https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip/meeting) through the TQIP Google group (https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/trauma-quality-improvement-program---tqip), and in Web conferences.

For more information, visit the TQIP website (www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/tqip).

Join Dr. Richardson for TTP Program Meet and Greet at Clinical Congress

J. David Richardson, MD, FACS, 2015-2016 President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and Chair of the ACS Committee on Transition to Practice (TTP) Program in General Surgery, will host an informal Meet and Greet during the ACS Clinical Congress 2016, 12:00 noon – 1:00 pm, Tuesday, October 18, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. Dr. Richardson will be available to speak with Clinical Congress attendees at the Division of Education Booth in the ACS Resource Center in Hall B. Residents who are considering careers in general surgery as well as faculty and practicing surgeons may be interested in learning more about the TTP Program at https://www.facs.org/education/program/ttp. Dennis W. Ashley, MD, FACS, FCCM, TTP chief of the Mercer University School of Medicine Program, Cordele, GA, which has successfully incorporated the TTP Program, will join Dr. Richardson at the Meet and Greet. Contact [email protected] for more information or stop by the Division of Education booth at the Clinical Congress and learn more about this growing program.

J. David Richardson, MD, FACS, 2015-2016 President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and Chair of the ACS Committee on Transition to Practice (TTP) Program in General Surgery, will host an informal Meet and Greet during the ACS Clinical Congress 2016, 12:00 noon – 1:00 pm, Tuesday, October 18, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. Dr. Richardson will be available to speak with Clinical Congress attendees at the Division of Education Booth in the ACS Resource Center in Hall B. Residents who are considering careers in general surgery as well as faculty and practicing surgeons may be interested in learning more about the TTP Program at https://www.facs.org/education/program/ttp. Dennis W. Ashley, MD, FACS, FCCM, TTP chief of the Mercer University School of Medicine Program, Cordele, GA, which has successfully incorporated the TTP Program, will join Dr. Richardson at the Meet and Greet. Contact [email protected] for more information or stop by the Division of Education booth at the Clinical Congress and learn more about this growing program.

J. David Richardson, MD, FACS, 2015-2016 President of the American College of Surgeons (ACS) and Chair of the ACS Committee on Transition to Practice (TTP) Program in General Surgery, will host an informal Meet and Greet during the ACS Clinical Congress 2016, 12:00 noon – 1:00 pm, Tuesday, October 18, at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. Dr. Richardson will be available to speak with Clinical Congress attendees at the Division of Education Booth in the ACS Resource Center in Hall B. Residents who are considering careers in general surgery as well as faculty and practicing surgeons may be interested in learning more about the TTP Program at https://www.facs.org/education/program/ttp. Dennis W. Ashley, MD, FACS, FCCM, TTP chief of the Mercer University School of Medicine Program, Cordele, GA, which has successfully incorporated the TTP Program, will join Dr. Richardson at the Meet and Greet. Contact [email protected] for more information or stop by the Division of Education booth at the Clinical Congress and learn more about this growing program.

ACS Issues Statement on Operating Room Attire

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has finalized a statement on professional attire for surgeons in and out of the operating room (OR). The new ACS guideline for appropriate attire is based on principles of professionalism, common sense, decorum, and the available evidence. It includes the following provisions:

• Soiled scrubs and/or hats should be changed as soon as feasible and certainly before speaking with family members after an operation.

• Scrubs and hats worn during dirty or contaminated cases should be changed prior to subsequent cases even if not visibly soiled.

• Dangling masks should not be worn at any time.

• Operating room scrubs should not be worn in the hospital facility outside of the OR area without a clean lab coat or appropriate cover.

• OR scrubs should not be worn at any time outside of the hospital perimeter.

• OR scrubs should be changed at least daily.

• During invasive procedures, the mouth, nose, and hair (skull and face) should be covered to avoid potential wound contamination. Large sideburns and ponytails should be covered or contained. There is no evidence that leaving ears, a limited amount of hair on the nape of the neck or a modest sideburn uncovered contributes to wound infections.

• Jewelry worn on the head or neck, where the items might fall into or contaminate the sterile field, should be removed or appropriately covered during procedures.

• The ACS encourages surgeons to wear clean, appropriate professional attire (not scrubs) during all patient encounters outside of the OR.

The ACS Statement on Operating Room Attire provides detailed guidelines on wearing the skullcap in a way that ensures patient safety and facilitates enforcement of the standard on wearing scrubs only within the perimeter of the hospital by suggesting the adoption of distinctively colored scrub suits for OR personnel.

In addition, the ACS is collaborating with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission to ensure that their policies and regulatory oversight activities are aligned with the College’s recommendations.

The statement will be published in the October Bulletin.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has finalized a statement on professional attire for surgeons in and out of the operating room (OR). The new ACS guideline for appropriate attire is based on principles of professionalism, common sense, decorum, and the available evidence. It includes the following provisions:

• Soiled scrubs and/or hats should be changed as soon as feasible and certainly before speaking with family members after an operation.

• Scrubs and hats worn during dirty or contaminated cases should be changed prior to subsequent cases even if not visibly soiled.

• Dangling masks should not be worn at any time.

• Operating room scrubs should not be worn in the hospital facility outside of the OR area without a clean lab coat or appropriate cover.

• OR scrubs should not be worn at any time outside of the hospital perimeter.

• OR scrubs should be changed at least daily.

• During invasive procedures, the mouth, nose, and hair (skull and face) should be covered to avoid potential wound contamination. Large sideburns and ponytails should be covered or contained. There is no evidence that leaving ears, a limited amount of hair on the nape of the neck or a modest sideburn uncovered contributes to wound infections.

• Jewelry worn on the head or neck, where the items might fall into or contaminate the sterile field, should be removed or appropriately covered during procedures.

• The ACS encourages surgeons to wear clean, appropriate professional attire (not scrubs) during all patient encounters outside of the OR.

The ACS Statement on Operating Room Attire provides detailed guidelines on wearing the skullcap in a way that ensures patient safety and facilitates enforcement of the standard on wearing scrubs only within the perimeter of the hospital by suggesting the adoption of distinctively colored scrub suits for OR personnel.

In addition, the ACS is collaborating with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission to ensure that their policies and regulatory oversight activities are aligned with the College’s recommendations.

The statement will be published in the October Bulletin.

The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has finalized a statement on professional attire for surgeons in and out of the operating room (OR). The new ACS guideline for appropriate attire is based on principles of professionalism, common sense, decorum, and the available evidence. It includes the following provisions:

• Soiled scrubs and/or hats should be changed as soon as feasible and certainly before speaking with family members after an operation.

• Scrubs and hats worn during dirty or contaminated cases should be changed prior to subsequent cases even if not visibly soiled.

• Dangling masks should not be worn at any time.

• Operating room scrubs should not be worn in the hospital facility outside of the OR area without a clean lab coat or appropriate cover.

• OR scrubs should not be worn at any time outside of the hospital perimeter.

• OR scrubs should be changed at least daily.

• During invasive procedures, the mouth, nose, and hair (skull and face) should be covered to avoid potential wound contamination. Large sideburns and ponytails should be covered or contained. There is no evidence that leaving ears, a limited amount of hair on the nape of the neck or a modest sideburn uncovered contributes to wound infections.

• Jewelry worn on the head or neck, where the items might fall into or contaminate the sterile field, should be removed or appropriately covered during procedures.

• The ACS encourages surgeons to wear clean, appropriate professional attire (not scrubs) during all patient encounters outside of the OR.

The ACS Statement on Operating Room Attire provides detailed guidelines on wearing the skullcap in a way that ensures patient safety and facilitates enforcement of the standard on wearing scrubs only within the perimeter of the hospital by suggesting the adoption of distinctively colored scrub suits for OR personnel.

In addition, the ACS is collaborating with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission to ensure that their policies and regulatory oversight activities are aligned with the College’s recommendations.

The statement will be published in the October Bulletin.

Register for ACS TQIP Conference, November 5-7, in Orlando, FL

Register online for the seventh annual American College of Surgeons (ACS) Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) Scientific Meeting and Training, November 5-7 at the Omni Orlando Resort at ChampionsGate, FL. Register for the conference at https://www.compusystems.com/servlet/ar?evt_uid=785.

The meeting will convene trauma medical directors, program managers, coordinators, and registrars from participating and prospective TQIP hospitals. J. Wayne Meredith, MD, FACS, MCCM, Winston-Salem, NC, the 2014 recipient of the ACS Distinguished Service Award and Past-Medical Director, ACS Trauma Programs, will deliver the keynote address. The program will include sessions for new TQIP centers, new staff at existing centers, and participants in need of a TQIP refresher. Breakout sessions focused on registrar and abstractor concerns, matters that relate to the trauma medical director and trauma program manager-focused issues will enhance the learning experience and instruct participants in their role on the TQIP team.

Visit the TQIP annual meeting website at https://www.facs.org/tqipmeeting to view the conference schedule and obtain information about lodging, transportation, and a social outing to Cirque du Soleil. For more information, contact ACS TQIP staff at [email protected].

Register online for the seventh annual American College of Surgeons (ACS) Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) Scientific Meeting and Training, November 5-7 at the Omni Orlando Resort at ChampionsGate, FL. Register for the conference at https://www.compusystems.com/servlet/ar?evt_uid=785.

The meeting will convene trauma medical directors, program managers, coordinators, and registrars from participating and prospective TQIP hospitals. J. Wayne Meredith, MD, FACS, MCCM, Winston-Salem, NC, the 2014 recipient of the ACS Distinguished Service Award and Past-Medical Director, ACS Trauma Programs, will deliver the keynote address. The program will include sessions for new TQIP centers, new staff at existing centers, and participants in need of a TQIP refresher. Breakout sessions focused on registrar and abstractor concerns, matters that relate to the trauma medical director and trauma program manager-focused issues will enhance the learning experience and instruct participants in their role on the TQIP team.

Visit the TQIP annual meeting website at https://www.facs.org/tqipmeeting to view the conference schedule and obtain information about lodging, transportation, and a social outing to Cirque du Soleil. For more information, contact ACS TQIP staff at [email protected].

Register online for the seventh annual American College of Surgeons (ACS) Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP®) Scientific Meeting and Training, November 5-7 at the Omni Orlando Resort at ChampionsGate, FL. Register for the conference at https://www.compusystems.com/servlet/ar?evt_uid=785.

The meeting will convene trauma medical directors, program managers, coordinators, and registrars from participating and prospective TQIP hospitals. J. Wayne Meredith, MD, FACS, MCCM, Winston-Salem, NC, the 2014 recipient of the ACS Distinguished Service Award and Past-Medical Director, ACS Trauma Programs, will deliver the keynote address. The program will include sessions for new TQIP centers, new staff at existing centers, and participants in need of a TQIP refresher. Breakout sessions focused on registrar and abstractor concerns, matters that relate to the trauma medical director and trauma program manager-focused issues will enhance the learning experience and instruct participants in their role on the TQIP team.

Visit the TQIP annual meeting website at https://www.facs.org/tqipmeeting to view the conference schedule and obtain information about lodging, transportation, and a social outing to Cirque du Soleil. For more information, contact ACS TQIP staff at [email protected].

National Medical Association honors Patricia L. Turner, MD, FACS

Patricia L. Turner, MD, FACS, Director of the American College of Surgeons Division of Member Services, received the 2016 National Medical Association (NMA) Council on Concerns of Women Physicians (CCWP) Service Award. Dr. Turner received the award July 31 at the CCWP Annual Muriel Petioni, MD, Awards Luncheon, which took place during the NMA’s 114th Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly in Los Angeles.

This award honors women physicians who, through research, community service, and activism, strive to eliminate health care disparities, provide people of color with quality health care, and address women’s health and professional issues. The awards program, the most highly attended event of the convention, continues to grow in popularity. This year’s program featured award-winning actress and television director Regina King. Read more about the NMA and the award at http://www.afassanoco.com/nma/ccwpprogram.html.

Patricia L. Turner, MD, FACS, Director of the American College of Surgeons Division of Member Services, received the 2016 National Medical Association (NMA) Council on Concerns of Women Physicians (CCWP) Service Award. Dr. Turner received the award July 31 at the CCWP Annual Muriel Petioni, MD, Awards Luncheon, which took place during the NMA’s 114th Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly in Los Angeles.

This award honors women physicians who, through research, community service, and activism, strive to eliminate health care disparities, provide people of color with quality health care, and address women’s health and professional issues. The awards program, the most highly attended event of the convention, continues to grow in popularity. This year’s program featured award-winning actress and television director Regina King. Read more about the NMA and the award at http://www.afassanoco.com/nma/ccwpprogram.html.

Patricia L. Turner, MD, FACS, Director of the American College of Surgeons Division of Member Services, received the 2016 National Medical Association (NMA) Council on Concerns of Women Physicians (CCWP) Service Award. Dr. Turner received the award July 31 at the CCWP Annual Muriel Petioni, MD, Awards Luncheon, which took place during the NMA’s 114th Annual Convention and Scientific Assembly in Los Angeles.

This award honors women physicians who, through research, community service, and activism, strive to eliminate health care disparities, provide people of color with quality health care, and address women’s health and professional issues. The awards program, the most highly attended event of the convention, continues to grow in popularity. This year’s program featured award-winning actress and television director Regina King. Read more about the NMA and the award at http://www.afassanoco.com/nma/ccwpprogram.html.

Experts review challenges, pearls in young onset dementia

SAN FRANCISCO – The patient, a man in his early 50s, smiled as he sang about flatulence. He seemed alert, relaxed, and aware of his wife and the neurologist in the room. Only the length and subject matter of his composition signaled a problem.

Two years later, this same patient was completely nonverbal – a classic case of frontotemporal dementia, said Howard Rosen, MD, a neurologist affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco. He and other experts discussed the disease at the 18th Congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association.

Frontotemporal dementia affects about 15-22 of every 100,000 individuals, and an additional 3-4 will be diagnosed in the next year, according to past studies (Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013 Apr;25[2]:130-7). This and other forms of dementia are often preceded by nondegenerative psychiatric syndromes, such as depression or anxiety, Dr. Rosen noted. “It is often unclear whether patients actually have that psychiatric disorder or symptoms of the disorder that are actually frontotemporal dementia,” he said. “Depression is most common and likely represents a misdiagnosis.”

Frontotemporal dementia also is often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s but differs in that about three-quarters of cases begin in midlife. This heightens the need for timely diagnosis and specialized services to support patients and caregivers, who may still have children at home, Dr. Rosen said. Unfortunately, such services are often lacking, he added.

Clinicians who treat patients with frontotemporal dementia encounter several “canonical variants” of the disease, he continued. These include nonfluent and semantic variants of primary progressive aphasia and a third behavioral variant. The nonfluent variant is characterized by frequent grammatical errors (agrammatism), hesitation over individual words, and speech apraxia. In contrast, patients with the semantic variant cannot name common objects, such as a ball or a cup, and only vaguely understand their use. Finally, those with the behavioral variant show “bizarre socioemotional changes,” including disinhibition and antisocial behavior, loss of empathy, “exceedingly poor” judgment, overeating, apathy, and hoarding and other compulsive behaviors, Dr. Rosen said.

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia can be especially difficult for family members, other experts said. Jan Oyebode, MD, of the University of Bradford, England, and her colleagues prospectively interviewed seven families and five patients with this form of dementia every 6-9 months to observe how the “lived experience” of the disease changed over time. Family members described struggling to understand emergent and worsening irritability, and lack of empathy in their loved one. “We saw this during the family interviews,” Dr. Oyebode added. “For example, one day a [caregiver with cancer] came back from chemotherapy, and her husband [the patient] turned to her and said something like, ‘you’re late. I’m hungry,’ and did not ask how the chemotherapy had gone. She had tears in her eyes. We had a number of examples like that.”

Another patient with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia began “going off” on his children, something he had not done before, Dr. Oyebode said. Intellectually, he understood that frontotemporal dementia was causing his behavior, but he struggled to control his rage and could not empathize with his children’s pain, she added. “If you live with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, you may be only partially aware of changes in our empathy,” she added. “Because you don’t appreciate the way you have changed, you are puzzled by others’ reactions to you. And because you don’t understand the changes in your own abilities, you tend to attribute them to external factors and blame or avoid others.”

But over time, four of the five patients acknowledged that their families had the most insight into their changing cognition and behavior, and some clearly tried to control their behaviors, Dr. Oyebode said. Nonetheless, it is important to understand that even when patients factually accept their diagnosis, they tend not to “live it from the inside,” she emphasized. “Because you [the patient] feel the same, you may be somewhat bewildered by the changes in your life. But because you do not ‘feel’ the changes, you are able to accept them, even though they are dramatic.”

Such acceptance comes more easily when patients receive calm, direct feedback from family members, she also reported. Family members, too, valued open communication as key to their own process. “For families, there needed to be a [transition] from awareness of the dementia, to empathic understanding, to developing coping processes,” she said. For example, family members learned to help patients plan ahead, step by step, for outings and deconstruct tasks by working them out on a whiteboard, she said.

Studies like this one are important because there is little research on presenile dementia, Dr. Rosen said. “When you’re dealing with young-onset dementia, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia has to be very prominent in your mind” – particularly because it progresses faster than do the other variants and about twice as fast as does Alzheimer’s disease. It can be easier to understand the symptomatic complexities of frontotemporal dementia by mapping them to specific neuroanatomy, Dr. Rosen added. Imaging is central to diagnosis, and indeed, frontotemporal dementia is the only neurodegenerative disease for which Medicare has approved FDG-PET scans as a diagnostic measure.

“What really differentiates frontotemporal dementia [from other dementias] is involvement of the orbital and medial lobes,” Dr. Rosen emphasized. “Think of Phineas Gage – the rod went right through the part of the brain we’re talking about.”

SAN FRANCISCO – The patient, a man in his early 50s, smiled as he sang about flatulence. He seemed alert, relaxed, and aware of his wife and the neurologist in the room. Only the length and subject matter of his composition signaled a problem.

Two years later, this same patient was completely nonverbal – a classic case of frontotemporal dementia, said Howard Rosen, MD, a neurologist affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco. He and other experts discussed the disease at the 18th Congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association.

Frontotemporal dementia affects about 15-22 of every 100,000 individuals, and an additional 3-4 will be diagnosed in the next year, according to past studies (Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013 Apr;25[2]:130-7). This and other forms of dementia are often preceded by nondegenerative psychiatric syndromes, such as depression or anxiety, Dr. Rosen noted. “It is often unclear whether patients actually have that psychiatric disorder or symptoms of the disorder that are actually frontotemporal dementia,” he said. “Depression is most common and likely represents a misdiagnosis.”

Frontotemporal dementia also is often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s but differs in that about three-quarters of cases begin in midlife. This heightens the need for timely diagnosis and specialized services to support patients and caregivers, who may still have children at home, Dr. Rosen said. Unfortunately, such services are often lacking, he added.

Clinicians who treat patients with frontotemporal dementia encounter several “canonical variants” of the disease, he continued. These include nonfluent and semantic variants of primary progressive aphasia and a third behavioral variant. The nonfluent variant is characterized by frequent grammatical errors (agrammatism), hesitation over individual words, and speech apraxia. In contrast, patients with the semantic variant cannot name common objects, such as a ball or a cup, and only vaguely understand their use. Finally, those with the behavioral variant show “bizarre socioemotional changes,” including disinhibition and antisocial behavior, loss of empathy, “exceedingly poor” judgment, overeating, apathy, and hoarding and other compulsive behaviors, Dr. Rosen said.

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia can be especially difficult for family members, other experts said. Jan Oyebode, MD, of the University of Bradford, England, and her colleagues prospectively interviewed seven families and five patients with this form of dementia every 6-9 months to observe how the “lived experience” of the disease changed over time. Family members described struggling to understand emergent and worsening irritability, and lack of empathy in their loved one. “We saw this during the family interviews,” Dr. Oyebode added. “For example, one day a [caregiver with cancer] came back from chemotherapy, and her husband [the patient] turned to her and said something like, ‘you’re late. I’m hungry,’ and did not ask how the chemotherapy had gone. She had tears in her eyes. We had a number of examples like that.”

Another patient with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia began “going off” on his children, something he had not done before, Dr. Oyebode said. Intellectually, he understood that frontotemporal dementia was causing his behavior, but he struggled to control his rage and could not empathize with his children’s pain, she added. “If you live with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, you may be only partially aware of changes in our empathy,” she added. “Because you don’t appreciate the way you have changed, you are puzzled by others’ reactions to you. And because you don’t understand the changes in your own abilities, you tend to attribute them to external factors and blame or avoid others.”

But over time, four of the five patients acknowledged that their families had the most insight into their changing cognition and behavior, and some clearly tried to control their behaviors, Dr. Oyebode said. Nonetheless, it is important to understand that even when patients factually accept their diagnosis, they tend not to “live it from the inside,” she emphasized. “Because you [the patient] feel the same, you may be somewhat bewildered by the changes in your life. But because you do not ‘feel’ the changes, you are able to accept them, even though they are dramatic.”

Such acceptance comes more easily when patients receive calm, direct feedback from family members, she also reported. Family members, too, valued open communication as key to their own process. “For families, there needed to be a [transition] from awareness of the dementia, to empathic understanding, to developing coping processes,” she said. For example, family members learned to help patients plan ahead, step by step, for outings and deconstruct tasks by working them out on a whiteboard, she said.

Studies like this one are important because there is little research on presenile dementia, Dr. Rosen said. “When you’re dealing with young-onset dementia, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia has to be very prominent in your mind” – particularly because it progresses faster than do the other variants and about twice as fast as does Alzheimer’s disease. It can be easier to understand the symptomatic complexities of frontotemporal dementia by mapping them to specific neuroanatomy, Dr. Rosen added. Imaging is central to diagnosis, and indeed, frontotemporal dementia is the only neurodegenerative disease for which Medicare has approved FDG-PET scans as a diagnostic measure.

“What really differentiates frontotemporal dementia [from other dementias] is involvement of the orbital and medial lobes,” Dr. Rosen emphasized. “Think of Phineas Gage – the rod went right through the part of the brain we’re talking about.”

SAN FRANCISCO – The patient, a man in his early 50s, smiled as he sang about flatulence. He seemed alert, relaxed, and aware of his wife and the neurologist in the room. Only the length and subject matter of his composition signaled a problem.

Two years later, this same patient was completely nonverbal – a classic case of frontotemporal dementia, said Howard Rosen, MD, a neurologist affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco. He and other experts discussed the disease at the 18th Congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association.

Frontotemporal dementia affects about 15-22 of every 100,000 individuals, and an additional 3-4 will be diagnosed in the next year, according to past studies (Int Rev Psychiatry. 2013 Apr;25[2]:130-7). This and other forms of dementia are often preceded by nondegenerative psychiatric syndromes, such as depression or anxiety, Dr. Rosen noted. “It is often unclear whether patients actually have that psychiatric disorder or symptoms of the disorder that are actually frontotemporal dementia,” he said. “Depression is most common and likely represents a misdiagnosis.”

Frontotemporal dementia also is often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s but differs in that about three-quarters of cases begin in midlife. This heightens the need for timely diagnosis and specialized services to support patients and caregivers, who may still have children at home, Dr. Rosen said. Unfortunately, such services are often lacking, he added.

Clinicians who treat patients with frontotemporal dementia encounter several “canonical variants” of the disease, he continued. These include nonfluent and semantic variants of primary progressive aphasia and a third behavioral variant. The nonfluent variant is characterized by frequent grammatical errors (agrammatism), hesitation over individual words, and speech apraxia. In contrast, patients with the semantic variant cannot name common objects, such as a ball or a cup, and only vaguely understand their use. Finally, those with the behavioral variant show “bizarre socioemotional changes,” including disinhibition and antisocial behavior, loss of empathy, “exceedingly poor” judgment, overeating, apathy, and hoarding and other compulsive behaviors, Dr. Rosen said.

Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia can be especially difficult for family members, other experts said. Jan Oyebode, MD, of the University of Bradford, England, and her colleagues prospectively interviewed seven families and five patients with this form of dementia every 6-9 months to observe how the “lived experience” of the disease changed over time. Family members described struggling to understand emergent and worsening irritability, and lack of empathy in their loved one. “We saw this during the family interviews,” Dr. Oyebode added. “For example, one day a [caregiver with cancer] came back from chemotherapy, and her husband [the patient] turned to her and said something like, ‘you’re late. I’m hungry,’ and did not ask how the chemotherapy had gone. She had tears in her eyes. We had a number of examples like that.”

Another patient with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia began “going off” on his children, something he had not done before, Dr. Oyebode said. Intellectually, he understood that frontotemporal dementia was causing his behavior, but he struggled to control his rage and could not empathize with his children’s pain, she added. “If you live with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, you may be only partially aware of changes in our empathy,” she added. “Because you don’t appreciate the way you have changed, you are puzzled by others’ reactions to you. And because you don’t understand the changes in your own abilities, you tend to attribute them to external factors and blame or avoid others.”

But over time, four of the five patients acknowledged that their families had the most insight into their changing cognition and behavior, and some clearly tried to control their behaviors, Dr. Oyebode said. Nonetheless, it is important to understand that even when patients factually accept their diagnosis, they tend not to “live it from the inside,” she emphasized. “Because you [the patient] feel the same, you may be somewhat bewildered by the changes in your life. But because you do not ‘feel’ the changes, you are able to accept them, even though they are dramatic.”

Such acceptance comes more easily when patients receive calm, direct feedback from family members, she also reported. Family members, too, valued open communication as key to their own process. “For families, there needed to be a [transition] from awareness of the dementia, to empathic understanding, to developing coping processes,” she said. For example, family members learned to help patients plan ahead, step by step, for outings and deconstruct tasks by working them out on a whiteboard, she said.

Studies like this one are important because there is little research on presenile dementia, Dr. Rosen said. “When you’re dealing with young-onset dementia, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia has to be very prominent in your mind” – particularly because it progresses faster than do the other variants and about twice as fast as does Alzheimer’s disease. It can be easier to understand the symptomatic complexities of frontotemporal dementia by mapping them to specific neuroanatomy, Dr. Rosen added. Imaging is central to diagnosis, and indeed, frontotemporal dementia is the only neurodegenerative disease for which Medicare has approved FDG-PET scans as a diagnostic measure.

“What really differentiates frontotemporal dementia [from other dementias] is involvement of the orbital and medial lobes,” Dr. Rosen emphasized. “Think of Phineas Gage – the rod went right through the part of the brain we’re talking about.”

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT IPA 2016

Obstetric VTE safety recommendations stress routine risk assessment

Routine thromboembolism risk assessment and use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis is an important part of obstetrics care, according to new recommendations from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety.

Although obstetric venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a common cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, prophylaxis recommendations are varied and nonspecific across obstetric organizations. The new maternity safety bundle from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety (NPMS) aims to eliminate some of the confusion.

“Based on increasing maternal risk of obstetric venous thromboembolism in the United States, the failure of current strategies to decrease venous thromboembolism as a proportionate cause of maternal death, and observational evidence from the United Kingdom that risk factor–based prophylaxis may reduce risk, the NPMS working group has interpreted current epidemiology and clinical research evidence to support routine thromboembolism risk assessment and consideration of more extensive risk factor–based prophylaxis,” the authors wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:688-98).

In the recommendations, prophylactic management of obstetric thromboembolism is organized into four categories: readiness, recognition, response, and reporting and systems learning.

The readiness component includes a recommendation to use a standard thromboembolism risk assessment tool at the first prenatal visit, all antepartum admissions, immediately post partum during childbirth hospitalization, and on discharge from the hospital after a birth. The Caprini and Padua scoring systems, which are tools designed for nonobstetric hospitalized patients, can be modified for obstetric patients, according to the recommendations.

The recognition component of the bundle emphasizes the use of education and guidelines to help physicians identify obstetric patients at risk for thromboembolism. The response component proposes a thromboembolism risk assessment at the first prenatal visit, followed by the use of standardized recommendations for mechanical thromboprophylaxis, dosing of prophylactic and therapeutic pharmacologic anticoagulation, and appropriate timing of pharmacologic prophylaxis with neuraxial anesthesia.

The reporting and systems learning component calls for reviews of a sample of a facility’s obstetric population to determine comorbid risk factors for VTE, followed by routine auditing of records to monitor risk assessment programs and patient care.

The NPMS suggests applying the American College of Chest Physicians recommendations for hospitalized, nonsurgical patients to pregnant women and postpartum women who have had a vaginal birth. However, they recommend using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines for pregnant and postpartum women with thrombophilia.

The NPMS also recommends that women receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis plus low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia, should discontinue aspirin at 35-36 weeks of gestation.

“Given the wide diversity of birthing facilities, a single national protocol is not recommended; instead, each facility should adapt a single protocol to improve maternal safety based on its patient population and resources,” the NPMS members wrote.

The NPMS is a joint effort including leaders from a range of women’s health care organizations, hospitals, professional societies, and regulators.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Routine thromboembolism risk assessment and use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis is an important part of obstetrics care, according to new recommendations from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety.

Although obstetric venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a common cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, prophylaxis recommendations are varied and nonspecific across obstetric organizations. The new maternity safety bundle from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety (NPMS) aims to eliminate some of the confusion.

“Based on increasing maternal risk of obstetric venous thromboembolism in the United States, the failure of current strategies to decrease venous thromboembolism as a proportionate cause of maternal death, and observational evidence from the United Kingdom that risk factor–based prophylaxis may reduce risk, the NPMS working group has interpreted current epidemiology and clinical research evidence to support routine thromboembolism risk assessment and consideration of more extensive risk factor–based prophylaxis,” the authors wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:688-98).

In the recommendations, prophylactic management of obstetric thromboembolism is organized into four categories: readiness, recognition, response, and reporting and systems learning.

The readiness component includes a recommendation to use a standard thromboembolism risk assessment tool at the first prenatal visit, all antepartum admissions, immediately post partum during childbirth hospitalization, and on discharge from the hospital after a birth. The Caprini and Padua scoring systems, which are tools designed for nonobstetric hospitalized patients, can be modified for obstetric patients, according to the recommendations.

The recognition component of the bundle emphasizes the use of education and guidelines to help physicians identify obstetric patients at risk for thromboembolism. The response component proposes a thromboembolism risk assessment at the first prenatal visit, followed by the use of standardized recommendations for mechanical thromboprophylaxis, dosing of prophylactic and therapeutic pharmacologic anticoagulation, and appropriate timing of pharmacologic prophylaxis with neuraxial anesthesia.

The reporting and systems learning component calls for reviews of a sample of a facility’s obstetric population to determine comorbid risk factors for VTE, followed by routine auditing of records to monitor risk assessment programs and patient care.

The NPMS suggests applying the American College of Chest Physicians recommendations for hospitalized, nonsurgical patients to pregnant women and postpartum women who have had a vaginal birth. However, they recommend using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines for pregnant and postpartum women with thrombophilia.

The NPMS also recommends that women receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis plus low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia, should discontinue aspirin at 35-36 weeks of gestation.

“Given the wide diversity of birthing facilities, a single national protocol is not recommended; instead, each facility should adapt a single protocol to improve maternal safety based on its patient population and resources,” the NPMS members wrote.

The NPMS is a joint effort including leaders from a range of women’s health care organizations, hospitals, professional societies, and regulators.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Routine thromboembolism risk assessment and use of both pharmacologic and mechanical thromboprophylaxis is an important part of obstetrics care, according to new recommendations from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety.

Although obstetric venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a common cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, prophylaxis recommendations are varied and nonspecific across obstetric organizations. The new maternity safety bundle from the National Partnership for Maternal Safety (NPMS) aims to eliminate some of the confusion.

“Based on increasing maternal risk of obstetric venous thromboembolism in the United States, the failure of current strategies to decrease venous thromboembolism as a proportionate cause of maternal death, and observational evidence from the United Kingdom that risk factor–based prophylaxis may reduce risk, the NPMS working group has interpreted current epidemiology and clinical research evidence to support routine thromboembolism risk assessment and consideration of more extensive risk factor–based prophylaxis,” the authors wrote (Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:688-98).

In the recommendations, prophylactic management of obstetric thromboembolism is organized into four categories: readiness, recognition, response, and reporting and systems learning.

The readiness component includes a recommendation to use a standard thromboembolism risk assessment tool at the first prenatal visit, all antepartum admissions, immediately post partum during childbirth hospitalization, and on discharge from the hospital after a birth. The Caprini and Padua scoring systems, which are tools designed for nonobstetric hospitalized patients, can be modified for obstetric patients, according to the recommendations.

The recognition component of the bundle emphasizes the use of education and guidelines to help physicians identify obstetric patients at risk for thromboembolism. The response component proposes a thromboembolism risk assessment at the first prenatal visit, followed by the use of standardized recommendations for mechanical thromboprophylaxis, dosing of prophylactic and therapeutic pharmacologic anticoagulation, and appropriate timing of pharmacologic prophylaxis with neuraxial anesthesia.

The reporting and systems learning component calls for reviews of a sample of a facility’s obstetric population to determine comorbid risk factors for VTE, followed by routine auditing of records to monitor risk assessment programs and patient care.

The NPMS suggests applying the American College of Chest Physicians recommendations for hospitalized, nonsurgical patients to pregnant women and postpartum women who have had a vaginal birth. However, they recommend using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guidelines for pregnant and postpartum women with thrombophilia.

The NPMS also recommends that women receiving pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis plus low-dose aspirin for the prevention of preeclampsia, should discontinue aspirin at 35-36 weeks of gestation.

“Given the wide diversity of birthing facilities, a single national protocol is not recommended; instead, each facility should adapt a single protocol to improve maternal safety based on its patient population and resources,” the NPMS members wrote.

The NPMS is a joint effort including leaders from a range of women’s health care organizations, hospitals, professional societies, and regulators.

The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

FDA approves Duchenne muscular dystrophy treatment under ‘accelerated pathway’

The first treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy has been greenlighted by the Food and Drug Administration.

The injectable eteplirsen (Exondys 51) was approved under the accelerated approval pathway, designed to fast-track medicines thought to exceed the benefits of existing treatments for life-threatening diseases, and was also granted priority review and an orphan drug designation. Eteplirsen is specifically indicated for patients who have a confirmed mutation of the dystrophin gene predisposed to exon 51 skipping. This includes about 13% of the population with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which occurs in about 1 of every 3,600 male infants worldwide.

“In rare diseases, new drug development is especially challenging due to the small numbers of people affected by each disease and the lack of medical understanding of many disorders,” Janet Woodcock, MD, the FDA’s director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), said in a statement.

The FDA found that data submitted by Sarepta Therapeutics sufficiently demonstrated an increase in dystrophin production, raising the possibility that there may be clinical benefit in this patient cohort; however, because eteplirsen’s actual clinical benefit has not been established, the FDA is requiring Sarepta to conduct a clinical trial. The study will assess whether eteplirsen improves motor function of this patient population. If the trial fails, the FDA is likely to withdraw approval.