User login

CHMP recommends drug for hemophilia A

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended marketing authorization for lonoctocog alfa (Afstyla), a recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) single-chain therapy.

Lonoctocog alfa is intended for the treatment and prophylaxis of bleeding in hemophilia A patients of all ages.

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission, which is expected to make a decision in the next few months.

Lonoctocog alfa is designed to provide lasting protection from bleeds with 2- to 3-times weekly dosing. The product uses a covalent bond that forms one structural entity, a single polypeptide-chain, to improve the stability of FVIII and provide longer-lasting FVIII activity.

Lonoctocog alfa is being developed by CSL Behring GmbH.

Clinical trials

The CHMP’s positive opinion of lonoctocog alfa is based on results from the AFFINITY clinical development program, which includes a trial of children (n=84) and a trial of adolescents and adults (n=175).

Among patients who received lonoctocog alfa prophylactically, the median annualized bleeding rate was 1.14 in the adults and adolescents and 3.69 in children younger than 12.

In all, there were 1195 bleeding events—848 in the adults/adolescents and 347 in the children.

Ninety-four percent of bleeds in adults/adolescents and 96% of bleeds in pediatric patients were effectively controlled with no more than 2 infusions of lonoctocog alfa weekly.

Eighty-one percent of bleeds in adults/adolescents and 86% of bleeds in pediatric patients were controlled by a single infusion.

Researchers assessed safety in 258 patients from both studies. Adverse reactions occurred in 14 patients and included hypersensitivity (n=4), dizziness (n=2), paresthesia (n=1), rash (n=1), erythema (n=1), pruritus (n=1), pyrexia (n=1), injection-site pain (n=1), chills (n=1), and feeling hot (n=1).

One patient withdrew from treatment due to hypersensitivity.

None of the patients developed neutralizing antibodies to FVIII or antibodies to host cell proteins. There were no reports of anaphylaxis or thrombosis. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended marketing authorization for lonoctocog alfa (Afstyla), a recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) single-chain therapy.

Lonoctocog alfa is intended for the treatment and prophylaxis of bleeding in hemophilia A patients of all ages.

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission, which is expected to make a decision in the next few months.

Lonoctocog alfa is designed to provide lasting protection from bleeds with 2- to 3-times weekly dosing. The product uses a covalent bond that forms one structural entity, a single polypeptide-chain, to improve the stability of FVIII and provide longer-lasting FVIII activity.

Lonoctocog alfa is being developed by CSL Behring GmbH.

Clinical trials

The CHMP’s positive opinion of lonoctocog alfa is based on results from the AFFINITY clinical development program, which includes a trial of children (n=84) and a trial of adolescents and adults (n=175).

Among patients who received lonoctocog alfa prophylactically, the median annualized bleeding rate was 1.14 in the adults and adolescents and 3.69 in children younger than 12.

In all, there were 1195 bleeding events—848 in the adults/adolescents and 347 in the children.

Ninety-four percent of bleeds in adults/adolescents and 96% of bleeds in pediatric patients were effectively controlled with no more than 2 infusions of lonoctocog alfa weekly.

Eighty-one percent of bleeds in adults/adolescents and 86% of bleeds in pediatric patients were controlled by a single infusion.

Researchers assessed safety in 258 patients from both studies. Adverse reactions occurred in 14 patients and included hypersensitivity (n=4), dizziness (n=2), paresthesia (n=1), rash (n=1), erythema (n=1), pruritus (n=1), pyrexia (n=1), injection-site pain (n=1), chills (n=1), and feeling hot (n=1).

One patient withdrew from treatment due to hypersensitivity.

None of the patients developed neutralizing antibodies to FVIII or antibodies to host cell proteins. There were no reports of anaphylaxis or thrombosis. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended marketing authorization for lonoctocog alfa (Afstyla), a recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) single-chain therapy.

Lonoctocog alfa is intended for the treatment and prophylaxis of bleeding in hemophilia A patients of all ages.

The CHMP’s recommendation will be reviewed by the European Commission, which is expected to make a decision in the next few months.

Lonoctocog alfa is designed to provide lasting protection from bleeds with 2- to 3-times weekly dosing. The product uses a covalent bond that forms one structural entity, a single polypeptide-chain, to improve the stability of FVIII and provide longer-lasting FVIII activity.

Lonoctocog alfa is being developed by CSL Behring GmbH.

Clinical trials

The CHMP’s positive opinion of lonoctocog alfa is based on results from the AFFINITY clinical development program, which includes a trial of children (n=84) and a trial of adolescents and adults (n=175).

Among patients who received lonoctocog alfa prophylactically, the median annualized bleeding rate was 1.14 in the adults and adolescents and 3.69 in children younger than 12.

In all, there were 1195 bleeding events—848 in the adults/adolescents and 347 in the children.

Ninety-four percent of bleeds in adults/adolescents and 96% of bleeds in pediatric patients were effectively controlled with no more than 2 infusions of lonoctocog alfa weekly.

Eighty-one percent of bleeds in adults/adolescents and 86% of bleeds in pediatric patients were controlled by a single infusion.

Researchers assessed safety in 258 patients from both studies. Adverse reactions occurred in 14 patients and included hypersensitivity (n=4), dizziness (n=2), paresthesia (n=1), rash (n=1), erythema (n=1), pruritus (n=1), pyrexia (n=1), injection-site pain (n=1), chills (n=1), and feeling hot (n=1).

One patient withdrew from treatment due to hypersensitivity.

None of the patients developed neutralizing antibodies to FVIII or antibodies to host cell proteins. There were no reports of anaphylaxis or thrombosis. ![]()

Topical tofacitinib shows promise in atopic dermatitis

Topical tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle, results of a phase IIa trial have shown.

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that affects the interleukin (IL)–4, IL-5, and IL-31 signaling pathways, interfering with the immune response that leads to inflammation.

The study could mean “that inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway may be a new therapeutic target for AD,” wrote the study’s lead author, Robert Bissonnette, MD, president of Innovaderm Research in Montreal. The study was published in the British Journal of Dermatology (2016 Nov;175[5]:902-11).

In the multicenter, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily, the study group achieved an 81.7% mean reduction in baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, compared with 29.9% of controls over the 4-week study period (P less than .001). EASI scores in the study group were about 80% at a score of 50, 60% at a score of 75, and 40% at a score of 90.

By week 4, about three-quarters of the study group were either clear or almost clear of their skin condition, according to the physician global assessment scale, compared with 22% of controls (P less than .05).

There also was a rapid reduction in patient-reported pruritus in the tofacitinib group per the Itch Severity Item scale, compared with controls, at weeks 2 and 4 (P less than .001 for each time point).

Tolerability was similar across the study, and treatment-related adverse effects were mild, although 44% of the tofacitinib group did report experiencing some form of infection, infestation, or other complication. Two people in the study group dropped out because of the severity of their treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no reported severe or serious infections.

Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the study’s sponsor.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

With the discovery of how cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 drive inflammatory disease pathogenesis, more targeted therapies are possible for dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis.

The promise of such pathogenesis-based treatments gives hope to patients with atopic dermatitis, for whom new treatments have not been brought to market in more than 15 years.

While this is reason for excitement, the emergence of several new promising therapies calls for comparison trials, according to Brett A. King, MD, and William Damsky, MD, PhD, both of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Further studies will be needed to address long-term efficacy and safety,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky noted. The results of Dr. Bissonnette’s phase IIa trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib mean there is potentially a third targeted topical agent to emerge as a treatment for atopic dermatitis. The others include the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4 and IL-13.

“Head-to-head trials involving these agents and superpotent topical steroids would be useful in establishing their place in AD treatment algorithms,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky said.

Dr. King is an assistant professor of dermatology at Yale University. His coauthor, Dr. Damsky, is a second-year resident in dermatology at Yale University. These remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Bissonnette’s study (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:861-2). Dr. King disclosed he has industry ties with Eli Lilly and Pfizer, among others. Dr. Damsky had no relevant disclosures.

With the discovery of how cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 drive inflammatory disease pathogenesis, more targeted therapies are possible for dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis.

The promise of such pathogenesis-based treatments gives hope to patients with atopic dermatitis, for whom new treatments have not been brought to market in more than 15 years.

While this is reason for excitement, the emergence of several new promising therapies calls for comparison trials, according to Brett A. King, MD, and William Damsky, MD, PhD, both of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Further studies will be needed to address long-term efficacy and safety,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky noted. The results of Dr. Bissonnette’s phase IIa trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib mean there is potentially a third targeted topical agent to emerge as a treatment for atopic dermatitis. The others include the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4 and IL-13.

“Head-to-head trials involving these agents and superpotent topical steroids would be useful in establishing their place in AD treatment algorithms,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky said.

Dr. King is an assistant professor of dermatology at Yale University. His coauthor, Dr. Damsky, is a second-year resident in dermatology at Yale University. These remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Bissonnette’s study (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:861-2). Dr. King disclosed he has industry ties with Eli Lilly and Pfizer, among others. Dr. Damsky had no relevant disclosures.

With the discovery of how cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, and IL-31 drive inflammatory disease pathogenesis, more targeted therapies are possible for dermatologic conditions such as atopic dermatitis.

The promise of such pathogenesis-based treatments gives hope to patients with atopic dermatitis, for whom new treatments have not been brought to market in more than 15 years.

While this is reason for excitement, the emergence of several new promising therapies calls for comparison trials, according to Brett A. King, MD, and William Damsky, MD, PhD, both of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“Further studies will be needed to address long-term efficacy and safety,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky noted. The results of Dr. Bissonnette’s phase IIa trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib mean there is potentially a third targeted topical agent to emerge as a treatment for atopic dermatitis. The others include the phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor crisaborole, and dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets IL-4 and IL-13.

“Head-to-head trials involving these agents and superpotent topical steroids would be useful in establishing their place in AD treatment algorithms,” Dr. King and Dr. Damsky said.

Dr. King is an assistant professor of dermatology at Yale University. His coauthor, Dr. Damsky, is a second-year resident in dermatology at Yale University. These remarks are taken from an editorial accompanying Dr. Bissonnette’s study (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:861-2). Dr. King disclosed he has industry ties with Eli Lilly and Pfizer, among others. Dr. Damsky had no relevant disclosures.

Topical tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle, results of a phase IIa trial have shown.

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that affects the interleukin (IL)–4, IL-5, and IL-31 signaling pathways, interfering with the immune response that leads to inflammation.

The study could mean “that inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway may be a new therapeutic target for AD,” wrote the study’s lead author, Robert Bissonnette, MD, president of Innovaderm Research in Montreal. The study was published in the British Journal of Dermatology (2016 Nov;175[5]:902-11).

In the multicenter, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily, the study group achieved an 81.7% mean reduction in baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, compared with 29.9% of controls over the 4-week study period (P less than .001). EASI scores in the study group were about 80% at a score of 50, 60% at a score of 75, and 40% at a score of 90.

By week 4, about three-quarters of the study group were either clear or almost clear of their skin condition, according to the physician global assessment scale, compared with 22% of controls (P less than .05).

There also was a rapid reduction in patient-reported pruritus in the tofacitinib group per the Itch Severity Item scale, compared with controls, at weeks 2 and 4 (P less than .001 for each time point).

Tolerability was similar across the study, and treatment-related adverse effects were mild, although 44% of the tofacitinib group did report experiencing some form of infection, infestation, or other complication. Two people in the study group dropped out because of the severity of their treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no reported severe or serious infections.

Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the study’s sponsor.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Topical tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle, results of a phase IIa trial have shown.

Tofacitinib is a Janus kinase inhibitor that affects the interleukin (IL)–4, IL-5, and IL-31 signaling pathways, interfering with the immune response that leads to inflammation.

The study could mean “that inhibition of the JAK-STAT pathway may be a new therapeutic target for AD,” wrote the study’s lead author, Robert Bissonnette, MD, president of Innovaderm Research in Montreal. The study was published in the British Journal of Dermatology (2016 Nov;175[5]:902-11).

In the multicenter, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily, the study group achieved an 81.7% mean reduction in baseline Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score, compared with 29.9% of controls over the 4-week study period (P less than .001). EASI scores in the study group were about 80% at a score of 50, 60% at a score of 75, and 40% at a score of 90.

By week 4, about three-quarters of the study group were either clear or almost clear of their skin condition, according to the physician global assessment scale, compared with 22% of controls (P less than .05).

There also was a rapid reduction in patient-reported pruritus in the tofacitinib group per the Itch Severity Item scale, compared with controls, at weeks 2 and 4 (P less than .001 for each time point).

Tolerability was similar across the study, and treatment-related adverse effects were mild, although 44% of the tofacitinib group did report experiencing some form of infection, infestation, or other complication. Two people in the study group dropped out because of the severity of their treatment-emergent adverse events. There were no reported severe or serious infections.

Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the study’s sponsor.

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

FROM BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Tofacitinib showed significant improvements across all endpoints and for pruritus at week 4, compared with vehicle (P less than .001)

Data source: Multicenter, phase IIa, 4-week, double-blind, controlled study of 69 adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis randomly assigned to either 2% tofacitinib or vehicle ointment twice daily.

Disclosures: Dr. Bissonnette has numerous pharmaceutical industry relationships, including with Pfizer, the sponsor of this study.

Infectious disease physicians: Antibiotic shortages are the new norm

NEW ORLEANS – Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr. Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs.73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The top 10 antimicrobials they reported as being in short supply were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. TMP-SMX and acyclovir were in short supply at both time points.

The most common ways respondents reported learning about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the Food and Drug Administration website or another website on shortages (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed – from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr. Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another – described as a blessing in disguise – was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr. Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and Pen-G as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board ... was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal – a way of life,” Dr. Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive ... maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

The problem of antibiotic shortages “harkens back to the day when penicillin was recycled in the urine [of soldiers in World War II] to save this very scarce resource ... but that’s a very extreme measure to take,” noted Donald Graham, MD, of the Springfield (Ill.) Clinic, one of the study’s coauthors. “It seems like it’s time for the other federal arm – namely, the Food and Drug Administration – to do something about this.”

Dr. Graham said he believes the problem is in part because of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it isn’t always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

“But they really have to recognize the importance of having availability of these simple agents,” he said, pleading with any FDA representatives in the audience to “maybe think about some of these very high standards.”

Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

NEW ORLEANS – Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr. Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs.73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The top 10 antimicrobials they reported as being in short supply were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. TMP-SMX and acyclovir were in short supply at both time points.

The most common ways respondents reported learning about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the Food and Drug Administration website or another website on shortages (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed – from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr. Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another – described as a blessing in disguise – was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr. Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and Pen-G as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board ... was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal – a way of life,” Dr. Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive ... maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

The problem of antibiotic shortages “harkens back to the day when penicillin was recycled in the urine [of soldiers in World War II] to save this very scarce resource ... but that’s a very extreme measure to take,” noted Donald Graham, MD, of the Springfield (Ill.) Clinic, one of the study’s coauthors. “It seems like it’s time for the other federal arm – namely, the Food and Drug Administration – to do something about this.”

Dr. Graham said he believes the problem is in part because of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it isn’t always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

“But they really have to recognize the importance of having availability of these simple agents,” he said, pleading with any FDA representatives in the audience to “maybe think about some of these very high standards.”

Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

NEW ORLEANS – Antibiotic shortages reported by the Emerging Infections Network (EIN) in 2011 persist in 2016, according to a web-based follow-up survey of infectious disease physicians.

Of 701 network members who responded to the EIN survey in early 2016, 70% reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years. They did so by using broader-spectrum agents (75% of respondents), more costly agents (58%), less effective second-line agents (45%), and more toxic agents (37%), Adi Gundlapalli, MD, PhD, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In addition, 73% of respondents reported that the shortages affected patient care or outcomes, reported Dr. Gundlapalli of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The percentage of respondents reporting adverse patient outcomes related to shortages increased from 2011 to 2016 (51% vs.73%), he noted at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The top 10 antimicrobials they reported as being in short supply were piperacillin-tazobactam, ampicillin-sulbactam, meropenem, cefotaxime, cefepime, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), doxycycline, imipenem, acyclovir, and amikacin. TMP-SMX and acyclovir were in short supply at both time points.

The most common ways respondents reported learning about drug shortages were from hospital notification (76%), from a colleague (56%), from a pharmacy that contacted them regarding a prescription for the agent (53%), or from the Food and Drug Administration website or another website on shortages (23%). The most common ways of learning about a shortage changed – from notification after trying to prescribe a drug in 2011, to proactive hospital/system (local) notification in 2016; 71% of respondents said that communications in 2016 were sufficient.

Most respondents (83%) reported that guidelines for dealing with shortages had been developed by an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP) at their institution.

“This, I think, is one of the highlight results,” said Dr. Gundlapalli, who is also a staff physician at the VA Salt Lake City Health System. “In 2011, we had no specific question or comments received about [ASPs], and here in 2016, 83% of respondents’ institutions had developed guidelines related to drug shortages.”

Respondents also had the opportunity to submit free-text responses, and among the themes that emerged was concern regarding toxicity and adverse outcomes associated with increased use of aminoglycosides because of the shortage of piperacillin-tazobactam. Another – described as a blessing in disguise – was the shortage of meropenem, which led one ASP to “institute restrictions on its use, which have continued,” he said.

“Another theme was ‘simpler agents seem more likely to be in shortage,’ ” Dr. Gundlapalli said, noting ampicillin-sulbactam in 2016 and Pen-G as examples.

“And then, of course, the other theme across the board ... was our new asset,” he said, explaining that some respondents commented on the value of ASP pharmacists and programs to help with drug shortage issues.

The overall theme of this follow-up survey, in the context of prior surveys in 2001 and 2011, is that antibiotic shortages are the “new normal – a way of life,” Dr. Gundlapalli said.

“The concerns do persist, and we feel there is further work to be done here,” he said. He specifically noted that there is a need to inform and educate fellows and colleagues in hospitals, increase awareness generally, improve communication strategies, and conduct detailed studies on adverse effects and outcomes.

“And now, since ASPs are very pervasive ... maybe it’s time to formalize and delineate the role of ASPs in antimicrobial shortages,” he said.

The problem of antibiotic shortages “harkens back to the day when penicillin was recycled in the urine [of soldiers in World War II] to save this very scarce resource ... but that’s a very extreme measure to take,” noted Donald Graham, MD, of the Springfield (Ill.) Clinic, one of the study’s coauthors. “It seems like it’s time for the other federal arm – namely, the Food and Drug Administration – to do something about this.”

Dr. Graham said he believes the problem is in part because of economics, and in part because of “the higher standards that the FDA imposes upon these manufacturing concerns.” These drugs often are low-profit items, and it isn’t always in the financial best interest of a pharmaceutical company to upgrade their facilities.

“But they really have to recognize the importance of having availability of these simple agents,” he said, pleading with any FDA representatives in the audience to “maybe think about some of these very high standards.”

Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

AT IDWEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 70% of respondents reported needing to modify their antimicrobial choice because of a shortage in the past 2 years, and 73% said shortages affected patient care or outcomes.

Data source: A follow-up survey of 701 physicians.

Disclosures: Dr. Gundlapalli reported having no disclosures. Dr. Graham disclosed relationships with Astellas and Theravance Biopharma.

Absorb’s problems will revise coronary scaffold standards

One-year outcome results of the first bioresorbable coronary scaffold on the U.S. and world markets, Absorb, failed to show longer-term problems with the device that only became apparent with 3-year follow-up.

The failure of Absorb to show benefits after 3 years in the ABSORB II trial will probably not dampen enthusiasm for the concept of a bioresorbable coronary scaffold (BRS). The idea of treating coronary stenoses with a stent that disappears after a few years once it has done its job is a powerfully attractive idea, and reports from several early-stage clinical tests of new BRSs during TCT 2016 showed that many next-generation versions of these devices are in very active development.

The surprising ABSORB II results showed more than just a failure of the Absorb BRS to produce 3 years after placement the improved coronary artery vasomotion and reduced late lumen loss that were the two primary efficacy endpoints of the trial.

The results also showed troubling signs of harm from the BRS, including significantly worse late lumen loss, compared with a contemporary drug-eluting metallic stent. In addition, there was a shocking 1%/year rate of late stent thrombosis during both the second and third years following Absorb placement in coronary arteries, the period when the Absorb BRS was in the process of disappearing, and which did not occur in the study’s control patients who received a conventional, metallic drug-eluting stent.

Patrick W. Serruys, MD, lead investigator of ABSORB II, attributed these adverse outcomes to the “highly thrombogenic” proteoglycan material that formed as the Absorb BRS resorbed, and a “structural discontinuity” of the BRS as it resorbed in some patients, resulting in parts of the scaffold remnant sticking out from the coronary artery wall toward the center of the vessel.

These late flaws in the bioresorption process will now need closer scrutiny during future studies of next-generation BRSs, and will surely mean longer follow-up of pivotal trials and a shift from the 1-year follow-up data used by the Food and Drug Administration when it approved the Absorb BRS last July.

“The challenge for the field [of BRS development] is the late results, as we saw in ABSORB II,” commented David J. Cohen, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo. The ABSORB II results “will lead to reexamination of the trial design and endpoints for the next generation of BRSs,” Dr. Cohen predicted at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“It’s not clear that BRS reduces the duration for DAPT,” Dr. Cohen noted, at least for the Absorb device, which is not full resorbed until it’s been in patients for about 3 years.

A striking property of the next-generation BRSs reported at the meeting was their use of thinner struts and faster resorption times. “These iterations hold immense promise for improving late outcomes,” commented Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati who helped lead the large U.S. clinical trial of the Absorb BRS, ABSORB III.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

One-year outcome results of the first bioresorbable coronary scaffold on the U.S. and world markets, Absorb, failed to show longer-term problems with the device that only became apparent with 3-year follow-up.

The failure of Absorb to show benefits after 3 years in the ABSORB II trial will probably not dampen enthusiasm for the concept of a bioresorbable coronary scaffold (BRS). The idea of treating coronary stenoses with a stent that disappears after a few years once it has done its job is a powerfully attractive idea, and reports from several early-stage clinical tests of new BRSs during TCT 2016 showed that many next-generation versions of these devices are in very active development.

The surprising ABSORB II results showed more than just a failure of the Absorb BRS to produce 3 years after placement the improved coronary artery vasomotion and reduced late lumen loss that were the two primary efficacy endpoints of the trial.

The results also showed troubling signs of harm from the BRS, including significantly worse late lumen loss, compared with a contemporary drug-eluting metallic stent. In addition, there was a shocking 1%/year rate of late stent thrombosis during both the second and third years following Absorb placement in coronary arteries, the period when the Absorb BRS was in the process of disappearing, and which did not occur in the study’s control patients who received a conventional, metallic drug-eluting stent.

Patrick W. Serruys, MD, lead investigator of ABSORB II, attributed these adverse outcomes to the “highly thrombogenic” proteoglycan material that formed as the Absorb BRS resorbed, and a “structural discontinuity” of the BRS as it resorbed in some patients, resulting in parts of the scaffold remnant sticking out from the coronary artery wall toward the center of the vessel.

These late flaws in the bioresorption process will now need closer scrutiny during future studies of next-generation BRSs, and will surely mean longer follow-up of pivotal trials and a shift from the 1-year follow-up data used by the Food and Drug Administration when it approved the Absorb BRS last July.

“The challenge for the field [of BRS development] is the late results, as we saw in ABSORB II,” commented David J. Cohen, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo. The ABSORB II results “will lead to reexamination of the trial design and endpoints for the next generation of BRSs,” Dr. Cohen predicted at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“It’s not clear that BRS reduces the duration for DAPT,” Dr. Cohen noted, at least for the Absorb device, which is not full resorbed until it’s been in patients for about 3 years.

A striking property of the next-generation BRSs reported at the meeting was their use of thinner struts and faster resorption times. “These iterations hold immense promise for improving late outcomes,” commented Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati who helped lead the large U.S. clinical trial of the Absorb BRS, ABSORB III.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

One-year outcome results of the first bioresorbable coronary scaffold on the U.S. and world markets, Absorb, failed to show longer-term problems with the device that only became apparent with 3-year follow-up.

The failure of Absorb to show benefits after 3 years in the ABSORB II trial will probably not dampen enthusiasm for the concept of a bioresorbable coronary scaffold (BRS). The idea of treating coronary stenoses with a stent that disappears after a few years once it has done its job is a powerfully attractive idea, and reports from several early-stage clinical tests of new BRSs during TCT 2016 showed that many next-generation versions of these devices are in very active development.

The surprising ABSORB II results showed more than just a failure of the Absorb BRS to produce 3 years after placement the improved coronary artery vasomotion and reduced late lumen loss that were the two primary efficacy endpoints of the trial.

The results also showed troubling signs of harm from the BRS, including significantly worse late lumen loss, compared with a contemporary drug-eluting metallic stent. In addition, there was a shocking 1%/year rate of late stent thrombosis during both the second and third years following Absorb placement in coronary arteries, the period when the Absorb BRS was in the process of disappearing, and which did not occur in the study’s control patients who received a conventional, metallic drug-eluting stent.

Patrick W. Serruys, MD, lead investigator of ABSORB II, attributed these adverse outcomes to the “highly thrombogenic” proteoglycan material that formed as the Absorb BRS resorbed, and a “structural discontinuity” of the BRS as it resorbed in some patients, resulting in parts of the scaffold remnant sticking out from the coronary artery wall toward the center of the vessel.

These late flaws in the bioresorption process will now need closer scrutiny during future studies of next-generation BRSs, and will surely mean longer follow-up of pivotal trials and a shift from the 1-year follow-up data used by the Food and Drug Administration when it approved the Absorb BRS last July.

“The challenge for the field [of BRS development] is the late results, as we saw in ABSORB II,” commented David J. Cohen, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Saint Luke’s Health System in Kansas City, Mo. The ABSORB II results “will lead to reexamination of the trial design and endpoints for the next generation of BRSs,” Dr. Cohen predicted at the meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“It’s not clear that BRS reduces the duration for DAPT,” Dr. Cohen noted, at least for the Absorb device, which is not full resorbed until it’s been in patients for about 3 years.

A striking property of the next-generation BRSs reported at the meeting was their use of thinner struts and faster resorption times. “These iterations hold immense promise for improving late outcomes,” commented Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati who helped lead the large U.S. clinical trial of the Absorb BRS, ABSORB III.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

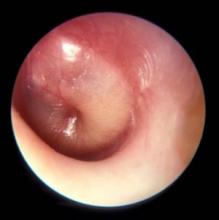

New research in otitis media means new controversies

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – As researchers have learned more about otitis media in the past decade, the guidelines have shifted accordingly for one of the most common conditions of childhood.

Yet some controversies remain, and the condition remains a challenge to properly identify, David Conrad, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Pediatricians already know it’s the most common reason young children come into their offices and the most common reason they prescribe antibiotics. But they may know less about recognizing complications and long-term effects.

Complications and treatment

Ossicular erosion or tympanic membrane perforation are two complications; the latter’s rate is 5%-29% for untreated acute otitis media. It typically closes within hours to days, however, with a 95% closure rate within 4 weeks.

“The ear drum is pretty forgiving, pretty resilient, really,” Dr. Conrad said. The perforation occurs when pressure builds up and takes the path of least resistance through the drum, but that release of pressure also typically relieves the pain.

“Mastoiditis is one of the most feared complications, obviously,” Dr. Conrad noted, and it’s a clinical diagnosis that’s important to distinguish from mastoid effusion.

“Any child who has acute otitis media, and the middle ear fills up with fluid, which is under pressure, it will then migrate up the mastoid cavity; so, if you have an ear infection, you will have mastoid fluid – but that doesn’t necessarily mean you have mastoiditis,” he explained. “Mastoiditis is a very aggressive inflammatory process that destroys bone in the mastoid cavity. It’s often due to strep, and it’s usually a pyogenic organism that’s particularly virulent.”

Pus will then leak out from the mastoid cavity and form an abscess. If there is bone destruction, that is mastoiditis, which is treated with an ear tube or sometimes a mastoidectomy, in which a drill drains all the pus and other tissue.

Speech development and other controversies

Aside from the child’s pain, parental anxiety, and the other potential complications, researchers have learned more recently about speech delay with otitis media. The average child with recurrent otitis media or with otitis media with effusion will experience decreased hearing for about 3 or 4 months, which can affect speech, educational, and cognitive outcomes.

“If that process repeats itself, they could lose out on an entire year of not hearing well. It’s like walking around with an ear plug in,” Dr. Conrad said. It’s about a 25-35 dB hearing loss, he said, which can lead to trouble with speech discrimination, particularly with background noise, and can interfere with relationships with family, peers, and other adults.

Emerging data suggest educational difficulties, such as problems with reading comprehension, could result, and research is pivoting to look at potential cognitive development concerns, Dr. Conrad said.

“It has been noted that earlier onset of otitis media has a greater impact on educational and attention outcomes,” he said. Central auditory processing drives the development of the auditory cortex, and if that is impaired during a critical window of opportunity while synapses are forming, it could also have effects on speech.

“Otitis media and speech development is an area of controversy,” Dr. Conrad explained. Otitis media has been found to impact auditory processing skills, speech discrimination, auditory pattern recognition, and auditory temporal processing, “but there’s little evidence to support long-term language impairment,” he said.

But that’s being challenged now. Research in rats and cats in particular, however, has shown changes in the auditory cortex from ear infections.

“Most of the data are from animal models, and I think that will morph into more studies into educational outcomes in children who had a lot of ear infections when they were younger,” Dr. Conrad predicted.

Other areas of controversy relate to whether the use of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), which has reduced ear infections, may have led to the rise of infections from Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, and what the duration of therapy should be for antibiotics.

If not doing watchful waiting, first-line treatment is amoxicillin or amoxicillin-clavulanate unless the child has a penicillin allergy, in which case cefdinir, cefuroxime, or cefpodoxime can be prescribed. After 48-72 hours of failed therapy, amoxicillin-clavulanate can be considered, or clindamycin or ceftriaxone, “obviously a popular option if the child has had multiple ear infections in the past month or so,” he said.

“If the child is older, we don’t treat as long,” Dr. Conrad noted. Current guidelines recommend a 10-day course if the infection resulted from strep, a 7-day or 10-day course in children aged 2-5 years, and a 5-7 day course for children older than 6 years.

Dr. Conrad reported no disclosures.

Phase II data suggest IV zanamivir safe for severe flu in kids

NEW ORLEANS – The investigational intravenous formulation of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir appears to be a safe influenza treatment for hospitalized children and adolescents at high risk of complications who can’t tolerate enteral therapy, according to findings from an open-label, multicenter, phase II study.

In 71 such patients with laboratory-confirmed flu, who presented within 7 days of illness onset and who received intravenous zanamivir (IVZ) for 5-10 days, 72% experienced adverse events (AEs), 21% experienced serious adverse events, and 5 deaths occurred, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to IVZ, Jeffrey Blumer, MD, reported at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Rather, the adverse events were “fairly diverse. ... the kinds of things normally seen in critically ill pediatric populations,” he said.

The patients, who had a mean age of 7 years, were treated with IVZ doses selected to provide exposures comparable to 600 mg in adults – a dosage shown in prior studies to be safe and well-tolerated in adults. Patients aged 6 months to under age 6 years received twice-daily doses of 14 mg/kg, and those aged 6 years to less than 18 years received twice-daily doses of 12 mg/kg, not to exceed 600 mg. Doses were adjusted for renal function.

Patients were enrolled from five countries, and most (69%) had received prior treatment with oseltamivir. More than half (56%) had chronic medical conditions.

The median time from symptom onset to IVZ treatment was 4 days, Dr. Blumer of the University of Toledo (Ohio) said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Infiltrate on chest x-ray was seen in 59% of patients, mechanical ventilation was required in 34% of patients, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was required in 6% of patients. Treatment in the intensive care unit was required in 65% of patients, and cumulative mortality was 4% at 14 days, and 7% at 28 days.

“Overall, the [IVZ] exposure and then the elimination profiles were consistent across the entire age cohort – unusual for most drugs, but it seemed to hold true, which makes zanamivir a lot easier for us to work with in pediatrics,” Dr. Blumer said.

While the numbers are small, exposure and response delineation didn’t seem to be impacted by mechanical ventilation, by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or by continuous renal replacement therapy, which is a good sign, he noted.

“So we generally had good, consistent experience here. ... Overall, 64 of the 71 patients survived, got better, left the ICU, and left the hospital,” Dr. Blumer said.

Of note, a treatment-emergent resistance substitution, E119G, was detected in a day 5 H1N1 isolate from an immunocompetent patient who improved clinically while on IVZ, he said, adding that no phenotype data were available as the sample could not be cultured.

The findings are important, because while zanamivir is currently labeled for patients older than 7 years, and the intravenous formulation currently in development has been shown to be safe for adults, there is a critical unmet need for an effective parenteral treatment for severe flu in children at high risk of complications who cannot tolerate enteral therapy.

“We need a drug that is available for the critically ill. We need a drug available for kids who are unable to take oral therapy, and for treatment of oseltamivir-resistant strains,” he said, adding that the current findings suggest that IVZ – with dose selection based on age, weight, and renal function – is a suitable treatment option for such patients.

“In conclusion, what we saw in this open-label trial was that the dose selection that we utilized gave us the kind of exposure we’d expect, and it seems it was an appropriate way to approach pediatric patients,” he said. “There wasn’t any safety signal attributable to the drug, and the overall pattern was more that of serious influenza, rather than of drug exposure.”

Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

NEW ORLEANS – The investigational intravenous formulation of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir appears to be a safe influenza treatment for hospitalized children and adolescents at high risk of complications who can’t tolerate enteral therapy, according to findings from an open-label, multicenter, phase II study.

In 71 such patients with laboratory-confirmed flu, who presented within 7 days of illness onset and who received intravenous zanamivir (IVZ) for 5-10 days, 72% experienced adverse events (AEs), 21% experienced serious adverse events, and 5 deaths occurred, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to IVZ, Jeffrey Blumer, MD, reported at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Rather, the adverse events were “fairly diverse. ... the kinds of things normally seen in critically ill pediatric populations,” he said.

The patients, who had a mean age of 7 years, were treated with IVZ doses selected to provide exposures comparable to 600 mg in adults – a dosage shown in prior studies to be safe and well-tolerated in adults. Patients aged 6 months to under age 6 years received twice-daily doses of 14 mg/kg, and those aged 6 years to less than 18 years received twice-daily doses of 12 mg/kg, not to exceed 600 mg. Doses were adjusted for renal function.

Patients were enrolled from five countries, and most (69%) had received prior treatment with oseltamivir. More than half (56%) had chronic medical conditions.

The median time from symptom onset to IVZ treatment was 4 days, Dr. Blumer of the University of Toledo (Ohio) said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Infiltrate on chest x-ray was seen in 59% of patients, mechanical ventilation was required in 34% of patients, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was required in 6% of patients. Treatment in the intensive care unit was required in 65% of patients, and cumulative mortality was 4% at 14 days, and 7% at 28 days.

“Overall, the [IVZ] exposure and then the elimination profiles were consistent across the entire age cohort – unusual for most drugs, but it seemed to hold true, which makes zanamivir a lot easier for us to work with in pediatrics,” Dr. Blumer said.

While the numbers are small, exposure and response delineation didn’t seem to be impacted by mechanical ventilation, by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or by continuous renal replacement therapy, which is a good sign, he noted.

“So we generally had good, consistent experience here. ... Overall, 64 of the 71 patients survived, got better, left the ICU, and left the hospital,” Dr. Blumer said.

Of note, a treatment-emergent resistance substitution, E119G, was detected in a day 5 H1N1 isolate from an immunocompetent patient who improved clinically while on IVZ, he said, adding that no phenotype data were available as the sample could not be cultured.

The findings are important, because while zanamivir is currently labeled for patients older than 7 years, and the intravenous formulation currently in development has been shown to be safe for adults, there is a critical unmet need for an effective parenteral treatment for severe flu in children at high risk of complications who cannot tolerate enteral therapy.

“We need a drug that is available for the critically ill. We need a drug available for kids who are unable to take oral therapy, and for treatment of oseltamivir-resistant strains,” he said, adding that the current findings suggest that IVZ – with dose selection based on age, weight, and renal function – is a suitable treatment option for such patients.

“In conclusion, what we saw in this open-label trial was that the dose selection that we utilized gave us the kind of exposure we’d expect, and it seems it was an appropriate way to approach pediatric patients,” he said. “There wasn’t any safety signal attributable to the drug, and the overall pattern was more that of serious influenza, rather than of drug exposure.”

Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

NEW ORLEANS – The investigational intravenous formulation of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir appears to be a safe influenza treatment for hospitalized children and adolescents at high risk of complications who can’t tolerate enteral therapy, according to findings from an open-label, multicenter, phase II study.

In 71 such patients with laboratory-confirmed flu, who presented within 7 days of illness onset and who received intravenous zanamivir (IVZ) for 5-10 days, 72% experienced adverse events (AEs), 21% experienced serious adverse events, and 5 deaths occurred, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to IVZ, Jeffrey Blumer, MD, reported at IDWeek, an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Rather, the adverse events were “fairly diverse. ... the kinds of things normally seen in critically ill pediatric populations,” he said.

The patients, who had a mean age of 7 years, were treated with IVZ doses selected to provide exposures comparable to 600 mg in adults – a dosage shown in prior studies to be safe and well-tolerated in adults. Patients aged 6 months to under age 6 years received twice-daily doses of 14 mg/kg, and those aged 6 years to less than 18 years received twice-daily doses of 12 mg/kg, not to exceed 600 mg. Doses were adjusted for renal function.

Patients were enrolled from five countries, and most (69%) had received prior treatment with oseltamivir. More than half (56%) had chronic medical conditions.

The median time from symptom onset to IVZ treatment was 4 days, Dr. Blumer of the University of Toledo (Ohio) said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society of Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Infiltrate on chest x-ray was seen in 59% of patients, mechanical ventilation was required in 34% of patients, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was required in 6% of patients. Treatment in the intensive care unit was required in 65% of patients, and cumulative mortality was 4% at 14 days, and 7% at 28 days.

“Overall, the [IVZ] exposure and then the elimination profiles were consistent across the entire age cohort – unusual for most drugs, but it seemed to hold true, which makes zanamivir a lot easier for us to work with in pediatrics,” Dr. Blumer said.

While the numbers are small, exposure and response delineation didn’t seem to be impacted by mechanical ventilation, by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or by continuous renal replacement therapy, which is a good sign, he noted.

“So we generally had good, consistent experience here. ... Overall, 64 of the 71 patients survived, got better, left the ICU, and left the hospital,” Dr. Blumer said.

Of note, a treatment-emergent resistance substitution, E119G, was detected in a day 5 H1N1 isolate from an immunocompetent patient who improved clinically while on IVZ, he said, adding that no phenotype data were available as the sample could not be cultured.

The findings are important, because while zanamivir is currently labeled for patients older than 7 years, and the intravenous formulation currently in development has been shown to be safe for adults, there is a critical unmet need for an effective parenteral treatment for severe flu in children at high risk of complications who cannot tolerate enteral therapy.

“We need a drug that is available for the critically ill. We need a drug available for kids who are unable to take oral therapy, and for treatment of oseltamivir-resistant strains,” he said, adding that the current findings suggest that IVZ – with dose selection based on age, weight, and renal function – is a suitable treatment option for such patients.

“In conclusion, what we saw in this open-label trial was that the dose selection that we utilized gave us the kind of exposure we’d expect, and it seems it was an appropriate way to approach pediatric patients,” he said. “There wasn’t any safety signal attributable to the drug, and the overall pattern was more that of serious influenza, rather than of drug exposure.”

Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

AT ID WEEK 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A total of 72% of patients experienced adverse events and 21% experienced serious adverse events, but none were considered by the investigators to be attributable to intravenous zanamivir.

Data source: An open-label, multicenter, phase II study of 71 children with laboratory-confirmed influenza.

Disclosures: Dr. Blumer reported receiving research support from GlaxoSmithKline, which sponsored the study.

Behavioral interventions durably reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing

NEW ORLEANS – The benefits of an 18-month behavioral intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the primary care setting were maintained 18 months after the intervention ended, according to follow-up data from a cluster randomized clinical trial.

During the 18-month intervention period, physicians at 47 adult and pediatric practices that participated in the trial, which compared three behavioral interventions and intervention combinations, significantly reduced their inappropriate prescribing.

After 18 months, the results were durable – and particularly so in the groups that received interventions that used “social motivation,” Jeffrey Linder, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

A total of 16,959 antibiotic-inappropriate visits (visits for nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, and influenza) were made to 248 clinicians during the 18-month intervention period, and 3,192 such visits were made to 224 clinicians during the postintervention period (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:562-70).

The interventions included “suggested alternatives,” which was an electronic health record-based approach that prompted the prescriber to answer whether a prescription was for an acute respiratory infection. A “yes” answer resulted in the prescriber receiving information about appropriate prescribing, along with a list of “easy nonantibiotic alternatives,” Dr. Linder explained, noting that the interventions involved “trying to make it easy to do the right thing.”

An “accountable justification” intervention used a similar process, but rather than suggesting alternative options, the program asked the prescriber to input a “tweet-length justification” of the prescription. The justification was then entered into the patient’s chart.

The third intervention involved “peer comparison.” Prescribers received monthly e-mail feedback regarding how their prescribing stacked up to that of their peers – specifically noting whether they were or were not “top performers.”

Some of the groups in the trial received combinations of these interventions, but the follow-up analysis showed that the latter two approaches, which involved “social motivation,” had the most durable effects.

For example, the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rate for those in the “accountable justification” group decreased from 23.2% to 5.2% at the end of the 18-month intervention period (absolute difference, -18.1%) and increased to 9% at the end of follow-up.

The inappropriate prescribing rate decreased from about 20% to about 4% in the “peer comparison” group at the end of the intervention period (absolute difference of -16.3%), then increased to 5% at the end of follow-up, Dr. Linder said at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

“The statistically best player here – the peer comparison group – went from 20% to 4% to 5%, so it only went back up 1% even after we turned the intervention off for 18 months,” he said.

Antibiotics often are inappropriately prescribed for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Such infections – including colds, sinusitis, strep throat, nonstrep pharyngitis, acute bronchitis, and influenza – make up only 10% of all ambulatory visits in the United States, but they account for 44% of all antibiotic prescribing, Dr. Linder said.

An estimated 50% of antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory infections are inappropriate, he added, noting that little success has been achieved with prior antibiotic stewardship efforts that focused largely on clinician education.

“So, we tried to tackle it a bit differently,” he said. “We saw a persistent significant change in antibiotic prescribing in the peer comparison intervention group. ... I would say that interventions that take advantage of social motivation appear to be effective or persistent.”

Dr. Linder reported having no relevant disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – The benefits of an 18-month behavioral intervention to reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in the primary care setting were maintained 18 months after the intervention ended, according to follow-up data from a cluster randomized clinical trial.

During the 18-month intervention period, physicians at 47 adult and pediatric practices that participated in the trial, which compared three behavioral interventions and intervention combinations, significantly reduced their inappropriate prescribing.

After 18 months, the results were durable – and particularly so in the groups that received interventions that used “social motivation,” Jeffrey Linder, MD, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

A total of 16,959 antibiotic-inappropriate visits (visits for nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, and influenza) were made to 248 clinicians during the 18-month intervention period, and 3,192 such visits were made to 224 clinicians during the postintervention period (JAMA. 2016 Feb 9;315[6]:562-70).

The interventions included “suggested alternatives,” which was an electronic health record-based approach that prompted the prescriber to answer whether a prescription was for an acute respiratory infection. A “yes” answer resulted in the prescriber receiving information about appropriate prescribing, along with a list of “easy nonantibiotic alternatives,” Dr. Linder explained, noting that the interventions involved “trying to make it easy to do the right thing.”

An “accountable justification” intervention used a similar process, but rather than suggesting alternative options, the program asked the prescriber to input a “tweet-length justification” of the prescription. The justification was then entered into the patient’s chart.

The third intervention involved “peer comparison.” Prescribers received monthly e-mail feedback regarding how their prescribing stacked up to that of their peers – specifically noting whether they were or were not “top performers.”

Some of the groups in the trial received combinations of these interventions, but the follow-up analysis showed that the latter two approaches, which involved “social motivation,” had the most durable effects.

For example, the inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rate for those in the “accountable justification” group decreased from 23.2% to 5.2% at the end of the 18-month intervention period (absolute difference, -18.1%) and increased to 9% at the end of follow-up.