User login

Medicaid restrictions loosening on access to HCV therapies

BOSTON – State Medicaid programs have begun to loosen restrictions and improve transparency around access to direct-acting antiviral agents to treat hepatitis C virus infection, but inconsistencies are still the norm nationwide.

“Far too many states continue to restrict access in defiance to their obligations under the law,” said Robert Greenwald, clinical professor of law at Harvard University Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI), Boston.

Since 2014, the number of states that do not publish their access criteria for direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) has dropped from 17 to 7, according to a report from CHLPI and the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (NVHR). Also during that period, 16 states relaxed or dropped fibrosis levels to qualify for access, and 7 decreased sobriety restrictions. The number of states that publish prescriber limitations has increased from 28 to 35. Because cost restrictions vary across insurance plans, some patients who need access get it, and others don’t, even if they have coverage, said Mr. Greenwald and Ryan Clary, NVHR executive director, who presented the report at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

NVHR is a coalition of advocacy groups and local governmental agencies with interests in HCV, HIV, and infectious diseases. Its sponsors include AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, OraSure Technologies, Quest Diagnostics, and Walgreens. CHLPI is supported in part by Gilead, BMS, Johnson & Johnson, and ViiV Health Care.

In November 2015, the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services issued guidance to states, noting that while the cost of DAAs is prohibitive, states should use “sound clinical judgment” when determining access, and to “not unreasonably restrict coverage.” Varied interpretation of the guidance by state Medicaid directors means there is still a great deal of inconsistency in coverage.

Robert W. Zavoski, MD, Connecticut medical director of social services, noted that his state is making gains on balancing patient and taxpayer interests by emphasizing prevention, curbing reinfection rates, and using predictive modeling to determine the cost of HCV comorbidities.

Aligning incentives between institutions and payers that are based on long-term patient outcomes would mean not just lowered costs, but actual savings said Doug Dieterich, MD, professor of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“It’s incredibly effective to treat hepatitis C virtually independent of the price of the drug. If patients remain in the same [health insurance] plan for 3-5 years after treatment, then the cost of treatment is very effective because the cost of health care drops precipitously – about 300% per patient – as soon as you cure hepatitis C,” Dr. Dieterich said.

Reducing the cost of treatments does not automatically result in better access, according John McHutchison, MD, executive vice president of clinical research at Gilead Sciences. Gilead’s DAAs (sofosbuvir and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir) were priced to the standard of care; however, miscalculations of demand drove up costs and “blew up” budgets, he said at the meeting.

Rebates to payers, discounts to patients, and the influx of new treatments to market are helping to drive down costs, Dr. McHutchison said, but while industry “wants to develop curative therapies, our system promotes chronic therapies from the financial perspective.”

The situation is compounded by the fact that state Medicaid programs negotiate individually with pharmaceutical companies and do not make their dealings public, said Brian Edlin, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. He called for more transparency regarding actual thresholds for profit and cure so that all restrictions could be dropped, and everyone could benefit. “How can much can we expect people to pay, what can we afford? All of that is out of the public domain,” he said.

Further dismantling of the barriers to care caused by high cost could be in the works if a recent proposal by FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, gains traction. In an editorial published in JAMA, Dr. Califf called for collaboration between federal agencies to hasten and clarify public notification of the necessary criteria for a drug’s approval, coverage, and payment.

In the meantime, Mr. Greenwald said he and other advocates “are putting Medicaid directors on notice.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – State Medicaid programs have begun to loosen restrictions and improve transparency around access to direct-acting antiviral agents to treat hepatitis C virus infection, but inconsistencies are still the norm nationwide.

“Far too many states continue to restrict access in defiance to their obligations under the law,” said Robert Greenwald, clinical professor of law at Harvard University Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI), Boston.

Since 2014, the number of states that do not publish their access criteria for direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) has dropped from 17 to 7, according to a report from CHLPI and the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (NVHR). Also during that period, 16 states relaxed or dropped fibrosis levels to qualify for access, and 7 decreased sobriety restrictions. The number of states that publish prescriber limitations has increased from 28 to 35. Because cost restrictions vary across insurance plans, some patients who need access get it, and others don’t, even if they have coverage, said Mr. Greenwald and Ryan Clary, NVHR executive director, who presented the report at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

NVHR is a coalition of advocacy groups and local governmental agencies with interests in HCV, HIV, and infectious diseases. Its sponsors include AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, OraSure Technologies, Quest Diagnostics, and Walgreens. CHLPI is supported in part by Gilead, BMS, Johnson & Johnson, and ViiV Health Care.

In November 2015, the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services issued guidance to states, noting that while the cost of DAAs is prohibitive, states should use “sound clinical judgment” when determining access, and to “not unreasonably restrict coverage.” Varied interpretation of the guidance by state Medicaid directors means there is still a great deal of inconsistency in coverage.

Robert W. Zavoski, MD, Connecticut medical director of social services, noted that his state is making gains on balancing patient and taxpayer interests by emphasizing prevention, curbing reinfection rates, and using predictive modeling to determine the cost of HCV comorbidities.

Aligning incentives between institutions and payers that are based on long-term patient outcomes would mean not just lowered costs, but actual savings said Doug Dieterich, MD, professor of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“It’s incredibly effective to treat hepatitis C virtually independent of the price of the drug. If patients remain in the same [health insurance] plan for 3-5 years after treatment, then the cost of treatment is very effective because the cost of health care drops precipitously – about 300% per patient – as soon as you cure hepatitis C,” Dr. Dieterich said.

Reducing the cost of treatments does not automatically result in better access, according John McHutchison, MD, executive vice president of clinical research at Gilead Sciences. Gilead’s DAAs (sofosbuvir and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir) were priced to the standard of care; however, miscalculations of demand drove up costs and “blew up” budgets, he said at the meeting.

Rebates to payers, discounts to patients, and the influx of new treatments to market are helping to drive down costs, Dr. McHutchison said, but while industry “wants to develop curative therapies, our system promotes chronic therapies from the financial perspective.”

The situation is compounded by the fact that state Medicaid programs negotiate individually with pharmaceutical companies and do not make their dealings public, said Brian Edlin, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. He called for more transparency regarding actual thresholds for profit and cure so that all restrictions could be dropped, and everyone could benefit. “How can much can we expect people to pay, what can we afford? All of that is out of the public domain,” he said.

Further dismantling of the barriers to care caused by high cost could be in the works if a recent proposal by FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, gains traction. In an editorial published in JAMA, Dr. Califf called for collaboration between federal agencies to hasten and clarify public notification of the necessary criteria for a drug’s approval, coverage, and payment.

In the meantime, Mr. Greenwald said he and other advocates “are putting Medicaid directors on notice.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – State Medicaid programs have begun to loosen restrictions and improve transparency around access to direct-acting antiviral agents to treat hepatitis C virus infection, but inconsistencies are still the norm nationwide.

“Far too many states continue to restrict access in defiance to their obligations under the law,” said Robert Greenwald, clinical professor of law at Harvard University Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation (CHLPI), Boston.

Since 2014, the number of states that do not publish their access criteria for direct-acting antiviral agents (DAA) has dropped from 17 to 7, according to a report from CHLPI and the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (NVHR). Also during that period, 16 states relaxed or dropped fibrosis levels to qualify for access, and 7 decreased sobriety restrictions. The number of states that publish prescriber limitations has increased from 28 to 35. Because cost restrictions vary across insurance plans, some patients who need access get it, and others don’t, even if they have coverage, said Mr. Greenwald and Ryan Clary, NVHR executive director, who presented the report at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

NVHR is a coalition of advocacy groups and local governmental agencies with interests in HCV, HIV, and infectious diseases. Its sponsors include AbbVie, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, OraSure Technologies, Quest Diagnostics, and Walgreens. CHLPI is supported in part by Gilead, BMS, Johnson & Johnson, and ViiV Health Care.

In November 2015, the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services issued guidance to states, noting that while the cost of DAAs is prohibitive, states should use “sound clinical judgment” when determining access, and to “not unreasonably restrict coverage.” Varied interpretation of the guidance by state Medicaid directors means there is still a great deal of inconsistency in coverage.

Robert W. Zavoski, MD, Connecticut medical director of social services, noted that his state is making gains on balancing patient and taxpayer interests by emphasizing prevention, curbing reinfection rates, and using predictive modeling to determine the cost of HCV comorbidities.

Aligning incentives between institutions and payers that are based on long-term patient outcomes would mean not just lowered costs, but actual savings said Doug Dieterich, MD, professor of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York.

“It’s incredibly effective to treat hepatitis C virtually independent of the price of the drug. If patients remain in the same [health insurance] plan for 3-5 years after treatment, then the cost of treatment is very effective because the cost of health care drops precipitously – about 300% per patient – as soon as you cure hepatitis C,” Dr. Dieterich said.

Reducing the cost of treatments does not automatically result in better access, according John McHutchison, MD, executive vice president of clinical research at Gilead Sciences. Gilead’s DAAs (sofosbuvir and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir) were priced to the standard of care; however, miscalculations of demand drove up costs and “blew up” budgets, he said at the meeting.

Rebates to payers, discounts to patients, and the influx of new treatments to market are helping to drive down costs, Dr. McHutchison said, but while industry “wants to develop curative therapies, our system promotes chronic therapies from the financial perspective.”

The situation is compounded by the fact that state Medicaid programs negotiate individually with pharmaceutical companies and do not make their dealings public, said Brian Edlin, MD, chief medical officer for the CDC National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. He called for more transparency regarding actual thresholds for profit and cure so that all restrictions could be dropped, and everyone could benefit. “How can much can we expect people to pay, what can we afford? All of that is out of the public domain,” he said.

Further dismantling of the barriers to care caused by high cost could be in the works if a recent proposal by FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, gains traction. In an editorial published in JAMA, Dr. Califf called for collaboration between federal agencies to hasten and clarify public notification of the necessary criteria for a drug’s approval, coverage, and payment.

In the meantime, Mr. Greenwald said he and other advocates “are putting Medicaid directors on notice.”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Debunking Psoriasis Myths: Do Psoriasis Therapies Cause Depression?

Myth: Psoriasis treatments may cause depression

It has been well documented that patients with inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis have an increased risk for depression. One population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom reported the risk of depression was greater in patients with severe psoriasis versus mild psoriasis. Younger psoriasis patients also had a higher risk compared to older patients. A US population-based study also reported that psoriasis was associated with major depression, but the severity of psoriasis and patient's age were unrelated. Therefore, all psoriasis patients may be at risk.

But are some therapies associated with an increased risk of depression? Increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α have been associated with depression apart from psoriasis. Administering immunomodulating agents has been shown to increase the risk of depression.

Depression has been cited as an adverse effect of apremilast in the drug's package insert, which states, "Before using [apremilast] in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal thoughts or behavior prescribers should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of treatment." In clinical trials, 1.3% (12/920) of participants treated with apremilast reported depression compared to 0.4% (2/506) treated with placebo. Dermatologists should remain vigilant about monitoring for symptoms of depression in patients treated with apremilast.

However, depression in the context of autoimmune disorders or any disorder with increased inflammation has responded to treatment with tumor necrosis factor α antagonists. The relationship between depression and inflammation suggests that there is an inflammatory subtype of depression and use of anti-inflammatory agents may treat both inflammation and depression.

Disease control has been shown to improve symptoms of depression in psoriasis patients. A study of 618 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who were treated with etanercept or placebo for 12 weeks revealed that more patients receiving etanercept experienced 50% improvement in 2 rating scales of depression compared to placebo.

Excessive worrying, a form of psychological distress, can impact treatment outcomes in patients with psoriasis. A 2003 study found that patients with psoriasis who are classified as high-level worriers may benefit from adjunctive psychological intervention before and during treatment. In this cohort of psoriasis patients receiving psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy, high-level worry was the only significant predictor of time taken for PUVA to clear psoriasis (P=.01). Patients in the high-level worry group cleared with PUVA treatment at a rate of 1.8 times slower than the low-level worry group.

In conclusion, psoriasis patients should follow the treatment plan outlined by dermatologists, as improving psoriasis symptoms may help alleviate depression or prevent it from occurring. Patients with a history of depression should be monitored carefully by dermatologists or referred to another health care professional, and patients as well as family and friends should be encouraged to report any depression symptoms.

Expert Commentary

The prescribing information for apremilast lists a warning (but not a black-box warning) for depression. Long-term registries will determine if there is truly an increased risk of depression when taking apremilast. When I counsel patients before prescribing apremilast, I mention this potential increased risk of depression as noted in the prescribing information, but I tell them that the risk is very low and that a true risk has not yet been determined in long-term registries. I mention to patients that if they really do feel depressed after starting apremilast, they should stop taking apremilast and contact me.

Long-term registries for etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab do not indicate an increased risk for depression. Intuitively, if a patient with severe psoriasis has depression worsened by their psoriasis, it stands to reason that improving their skin will likely improve their mood, which clinical trials have shown using patient-related outcomes.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Almond M. Depression and inflammation: examining the link. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:24-32.

Cohen BE, Martires KJ, Ho RS. Psoriasis and the risk of depression in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:73-79.

Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, et al. Psychological distress impairs clearance of psoriasis in patients treated with photochemotherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:752-756.

Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, et al. The risk of depression, anxiety and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:891-895.

Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2015.Research links psoriasis, depression [press release]. New York, NY: American Academy of Dermatology; August 20, 2015. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/research-links-psoriasis-depression. Accessed November 16, 2016.

Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29-35

Myth: Psoriasis treatments may cause depression

It has been well documented that patients with inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis have an increased risk for depression. One population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom reported the risk of depression was greater in patients with severe psoriasis versus mild psoriasis. Younger psoriasis patients also had a higher risk compared to older patients. A US population-based study also reported that psoriasis was associated with major depression, but the severity of psoriasis and patient's age were unrelated. Therefore, all psoriasis patients may be at risk.

But are some therapies associated with an increased risk of depression? Increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α have been associated with depression apart from psoriasis. Administering immunomodulating agents has been shown to increase the risk of depression.

Depression has been cited as an adverse effect of apremilast in the drug's package insert, which states, "Before using [apremilast] in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal thoughts or behavior prescribers should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of treatment." In clinical trials, 1.3% (12/920) of participants treated with apremilast reported depression compared to 0.4% (2/506) treated with placebo. Dermatologists should remain vigilant about monitoring for symptoms of depression in patients treated with apremilast.

However, depression in the context of autoimmune disorders or any disorder with increased inflammation has responded to treatment with tumor necrosis factor α antagonists. The relationship between depression and inflammation suggests that there is an inflammatory subtype of depression and use of anti-inflammatory agents may treat both inflammation and depression.

Disease control has been shown to improve symptoms of depression in psoriasis patients. A study of 618 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who were treated with etanercept or placebo for 12 weeks revealed that more patients receiving etanercept experienced 50% improvement in 2 rating scales of depression compared to placebo.

Excessive worrying, a form of psychological distress, can impact treatment outcomes in patients with psoriasis. A 2003 study found that patients with psoriasis who are classified as high-level worriers may benefit from adjunctive psychological intervention before and during treatment. In this cohort of psoriasis patients receiving psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy, high-level worry was the only significant predictor of time taken for PUVA to clear psoriasis (P=.01). Patients in the high-level worry group cleared with PUVA treatment at a rate of 1.8 times slower than the low-level worry group.

In conclusion, psoriasis patients should follow the treatment plan outlined by dermatologists, as improving psoriasis symptoms may help alleviate depression or prevent it from occurring. Patients with a history of depression should be monitored carefully by dermatologists or referred to another health care professional, and patients as well as family and friends should be encouraged to report any depression symptoms.

Expert Commentary

The prescribing information for apremilast lists a warning (but not a black-box warning) for depression. Long-term registries will determine if there is truly an increased risk of depression when taking apremilast. When I counsel patients before prescribing apremilast, I mention this potential increased risk of depression as noted in the prescribing information, but I tell them that the risk is very low and that a true risk has not yet been determined in long-term registries. I mention to patients that if they really do feel depressed after starting apremilast, they should stop taking apremilast and contact me.

Long-term registries for etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab do not indicate an increased risk for depression. Intuitively, if a patient with severe psoriasis has depression worsened by their psoriasis, it stands to reason that improving their skin will likely improve their mood, which clinical trials have shown using patient-related outcomes.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Myth: Psoriasis treatments may cause depression

It has been well documented that patients with inflammatory diseases such as psoriasis have an increased risk for depression. One population-based cohort study in the United Kingdom reported the risk of depression was greater in patients with severe psoriasis versus mild psoriasis. Younger psoriasis patients also had a higher risk compared to older patients. A US population-based study also reported that psoriasis was associated with major depression, but the severity of psoriasis and patient's age were unrelated. Therefore, all psoriasis patients may be at risk.

But are some therapies associated with an increased risk of depression? Increased concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α have been associated with depression apart from psoriasis. Administering immunomodulating agents has been shown to increase the risk of depression.

Depression has been cited as an adverse effect of apremilast in the drug's package insert, which states, "Before using [apremilast] in patients with a history of depression and/or suicidal thoughts or behavior prescribers should carefully weigh the risks and benefits of treatment." In clinical trials, 1.3% (12/920) of participants treated with apremilast reported depression compared to 0.4% (2/506) treated with placebo. Dermatologists should remain vigilant about monitoring for symptoms of depression in patients treated with apremilast.

However, depression in the context of autoimmune disorders or any disorder with increased inflammation has responded to treatment with tumor necrosis factor α antagonists. The relationship between depression and inflammation suggests that there is an inflammatory subtype of depression and use of anti-inflammatory agents may treat both inflammation and depression.

Disease control has been shown to improve symptoms of depression in psoriasis patients. A study of 618 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who were treated with etanercept or placebo for 12 weeks revealed that more patients receiving etanercept experienced 50% improvement in 2 rating scales of depression compared to placebo.

Excessive worrying, a form of psychological distress, can impact treatment outcomes in patients with psoriasis. A 2003 study found that patients with psoriasis who are classified as high-level worriers may benefit from adjunctive psychological intervention before and during treatment. In this cohort of psoriasis patients receiving psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy, high-level worry was the only significant predictor of time taken for PUVA to clear psoriasis (P=.01). Patients in the high-level worry group cleared with PUVA treatment at a rate of 1.8 times slower than the low-level worry group.

In conclusion, psoriasis patients should follow the treatment plan outlined by dermatologists, as improving psoriasis symptoms may help alleviate depression or prevent it from occurring. Patients with a history of depression should be monitored carefully by dermatologists or referred to another health care professional, and patients as well as family and friends should be encouraged to report any depression symptoms.

Expert Commentary

The prescribing information for apremilast lists a warning (but not a black-box warning) for depression. Long-term registries will determine if there is truly an increased risk of depression when taking apremilast. When I counsel patients before prescribing apremilast, I mention this potential increased risk of depression as noted in the prescribing information, but I tell them that the risk is very low and that a true risk has not yet been determined in long-term registries. I mention to patients that if they really do feel depressed after starting apremilast, they should stop taking apremilast and contact me.

Long-term registries for etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab do not indicate an increased risk for depression. Intuitively, if a patient with severe psoriasis has depression worsened by their psoriasis, it stands to reason that improving their skin will likely improve their mood, which clinical trials have shown using patient-related outcomes.

—Jashin J. Wu, MD (Los Angeles, California)

Almond M. Depression and inflammation: examining the link. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:24-32.

Cohen BE, Martires KJ, Ho RS. Psoriasis and the risk of depression in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:73-79.

Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, et al. Psychological distress impairs clearance of psoriasis in patients treated with photochemotherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:752-756.

Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, et al. The risk of depression, anxiety and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:891-895.

Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2015.Research links psoriasis, depression [press release]. New York, NY: American Academy of Dermatology; August 20, 2015. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/research-links-psoriasis-depression. Accessed November 16, 2016.

Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29-35

Almond M. Depression and inflammation: examining the link. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:24-32.

Cohen BE, Martires KJ, Ho RS. Psoriasis and the risk of depression in the US population: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2012. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:73-79.

Fortune DG, Richards HL, Kirby B, et al. Psychological distress impairs clearance of psoriasis in patients treated with photochemotherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:752-756.

Kurd SK, Troxel AB, Crits-Christoph P, et al. The risk of depression, anxiety and suicidality in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:891-895.

Otezla [package insert]. Summit, NJ: Celgene Corporation; 2015.Research links psoriasis, depression [press release]. New York, NY: American Academy of Dermatology; August 20, 2015. https://www.aad.org/media/news-releases/research-links-psoriasis-depression. Accessed November 16, 2016.

Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29-35

Higher sRAGE found in nonfocal ARDS

A biomarker may show whether acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is focal or nonfocal, a study showed.

This is an important distinction because some research suggests nonfocal ARDS, characterized by diffuse lung aeration loss, may have a worse prognosis and the two subtypes may respond differently to interventions such as positive end-expiratory pressure and recruitment maneuvers.

At present, the only way to identify focal versus nonfocal ARDS is a computed tomography scan, but that is often impractical because of the risks of moving the patient.

The current research, published in the November issue of CHEST (2016;150:998-1007), revealed that patients with nonfocal ARDS have higher plasma levels of the soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end product (sRAGE). At a cutoff of 1,188 pg/ml, the blood test differentiated between focal and nonfocal ARDS with a 94% sensitivity and an 84% specificity.

“Elevated baseline plasma sRAGE is a strong marker of nonfocal CT-based lung-imaging pattern in patients with early ARDS,” reported Jean-Michel Constantin of University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand (France) and colleagues in the Azurea network.

The researchers recruited 119 consecutive ARDS patients from 10 intensive care units in France. They measured plasma levels of sRAGE, plasminogen activator inhibitor–1 (PAI-1), soluble intercellular adhesion molecule–1, and surfactant protein–D within 24 hours of ARDS onset. Each patient underwent a lung CT scan within 48 hours to assess focal versus nonfocal lung morphology.

Twenty-seven percent of patients had focal ARDS, while 73% were categorized as nonfocal. Mean plasma levels of sRAGE were much higher in nonfocal patients (3,074 pg/ml vs. 877 pg/ml, P less than .001). A cutoff value of 1,188 ng/ml distinguished focal and nonfocal ARDS with a sensitivity of 93% (95% confidence interval, 85%-97%) and a specificity of 84% (95% CI, 66%-95%). The test’s positive predictive value was 94% (95% CI, 87%-98%), and its negative predictive value was 81% (95% CI, 64%-93%).

The research is still in its early stage, but has a couple possible applications, according to Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, of Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. “We might conceive of using this as a marker for nonfocal ARDS, and potentially use it to identify patients with worse outcomes. The other thing is, it may be a clue to help us learn about the underlying physiology of the disease,” he said in an interview.

If physicians can confidently categorize a patient, it could inform treatment. “We know that patients who have diffuse disease may be more likely to be treated successfully with advanced ventilator techniques. These techniques would be more useful and likely to lead to recovery in patients that don’t have focal disease,” said Dr. Ouellette.

However, he added that more research is needed. “These results are exciting, but they are very preliminary,” Dr Ouellette said.

The study was funded by the Auvergne Regional Council, the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche, and the Direction Generale de l’Offre de Soins, and the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand. The authors reported receiving funds from various pharmaceutical companies.

“Mechanical stress is concentrated at the border zones between well-[aerated] and poorly aerated lung units, which is thought to predispose to mechanical lung injury in these regions during tidal ventilation. … The results of the current study support this possibility that mechanical lung injury persists in regions of stress concentration during low tidal volume ventilation, contributing to higher mortality in nonfocal ARDS.

“The current study also provides additional evidence that a plasma biomarker, such as sRAGE, could improve our ability to endotype patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome], forecast prognosis, and identify subgroups for targeting of specific therapies early in the course of [acute respiratory distress syndrome].”

Michael A. Matthay , MD, is a professor of medicine and anesthesia at the University of California, San Francisco, and is with the Cardiovascular Research Institute. Jeremy R. Beitler, MD, is with the department of medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matthay consults for Cerus Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Boerhinger-Ingleheim, Bayer, Biogen, Quark Pharmaceuticals, and Incardia. Dr. Beitler has received research support from Amgen and GlaxoSmithKline.

“Mechanical stress is concentrated at the border zones between well-[aerated] and poorly aerated lung units, which is thought to predispose to mechanical lung injury in these regions during tidal ventilation. … The results of the current study support this possibility that mechanical lung injury persists in regions of stress concentration during low tidal volume ventilation, contributing to higher mortality in nonfocal ARDS.

“The current study also provides additional evidence that a plasma biomarker, such as sRAGE, could improve our ability to endotype patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome], forecast prognosis, and identify subgroups for targeting of specific therapies early in the course of [acute respiratory distress syndrome].”

Michael A. Matthay , MD, is a professor of medicine and anesthesia at the University of California, San Francisco, and is with the Cardiovascular Research Institute. Jeremy R. Beitler, MD, is with the department of medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matthay consults for Cerus Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Boerhinger-Ingleheim, Bayer, Biogen, Quark Pharmaceuticals, and Incardia. Dr. Beitler has received research support from Amgen and GlaxoSmithKline.

“Mechanical stress is concentrated at the border zones between well-[aerated] and poorly aerated lung units, which is thought to predispose to mechanical lung injury in these regions during tidal ventilation. … The results of the current study support this possibility that mechanical lung injury persists in regions of stress concentration during low tidal volume ventilation, contributing to higher mortality in nonfocal ARDS.

“The current study also provides additional evidence that a plasma biomarker, such as sRAGE, could improve our ability to endotype patients with [acute respiratory distress syndrome], forecast prognosis, and identify subgroups for targeting of specific therapies early in the course of [acute respiratory distress syndrome].”

Michael A. Matthay , MD, is a professor of medicine and anesthesia at the University of California, San Francisco, and is with the Cardiovascular Research Institute. Jeremy R. Beitler, MD, is with the department of medicine at the University of California, San Diego. Dr. Matthay consults for Cerus Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, Boerhinger-Ingleheim, Bayer, Biogen, Quark Pharmaceuticals, and Incardia. Dr. Beitler has received research support from Amgen and GlaxoSmithKline.

A biomarker may show whether acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is focal or nonfocal, a study showed.

This is an important distinction because some research suggests nonfocal ARDS, characterized by diffuse lung aeration loss, may have a worse prognosis and the two subtypes may respond differently to interventions such as positive end-expiratory pressure and recruitment maneuvers.

At present, the only way to identify focal versus nonfocal ARDS is a computed tomography scan, but that is often impractical because of the risks of moving the patient.

The current research, published in the November issue of CHEST (2016;150:998-1007), revealed that patients with nonfocal ARDS have higher plasma levels of the soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end product (sRAGE). At a cutoff of 1,188 pg/ml, the blood test differentiated between focal and nonfocal ARDS with a 94% sensitivity and an 84% specificity.

“Elevated baseline plasma sRAGE is a strong marker of nonfocal CT-based lung-imaging pattern in patients with early ARDS,” reported Jean-Michel Constantin of University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand (France) and colleagues in the Azurea network.

The researchers recruited 119 consecutive ARDS patients from 10 intensive care units in France. They measured plasma levels of sRAGE, plasminogen activator inhibitor–1 (PAI-1), soluble intercellular adhesion molecule–1, and surfactant protein–D within 24 hours of ARDS onset. Each patient underwent a lung CT scan within 48 hours to assess focal versus nonfocal lung morphology.

Twenty-seven percent of patients had focal ARDS, while 73% were categorized as nonfocal. Mean plasma levels of sRAGE were much higher in nonfocal patients (3,074 pg/ml vs. 877 pg/ml, P less than .001). A cutoff value of 1,188 ng/ml distinguished focal and nonfocal ARDS with a sensitivity of 93% (95% confidence interval, 85%-97%) and a specificity of 84% (95% CI, 66%-95%). The test’s positive predictive value was 94% (95% CI, 87%-98%), and its negative predictive value was 81% (95% CI, 64%-93%).

The research is still in its early stage, but has a couple possible applications, according to Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, of Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. “We might conceive of using this as a marker for nonfocal ARDS, and potentially use it to identify patients with worse outcomes. The other thing is, it may be a clue to help us learn about the underlying physiology of the disease,” he said in an interview.

If physicians can confidently categorize a patient, it could inform treatment. “We know that patients who have diffuse disease may be more likely to be treated successfully with advanced ventilator techniques. These techniques would be more useful and likely to lead to recovery in patients that don’t have focal disease,” said Dr. Ouellette.

However, he added that more research is needed. “These results are exciting, but they are very preliminary,” Dr Ouellette said.

The study was funded by the Auvergne Regional Council, the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche, and the Direction Generale de l’Offre de Soins, and the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand. The authors reported receiving funds from various pharmaceutical companies.

A biomarker may show whether acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is focal or nonfocal, a study showed.

This is an important distinction because some research suggests nonfocal ARDS, characterized by diffuse lung aeration loss, may have a worse prognosis and the two subtypes may respond differently to interventions such as positive end-expiratory pressure and recruitment maneuvers.

At present, the only way to identify focal versus nonfocal ARDS is a computed tomography scan, but that is often impractical because of the risks of moving the patient.

The current research, published in the November issue of CHEST (2016;150:998-1007), revealed that patients with nonfocal ARDS have higher plasma levels of the soluble form of the receptor for advanced glycation end product (sRAGE). At a cutoff of 1,188 pg/ml, the blood test differentiated between focal and nonfocal ARDS with a 94% sensitivity and an 84% specificity.

“Elevated baseline plasma sRAGE is a strong marker of nonfocal CT-based lung-imaging pattern in patients with early ARDS,” reported Jean-Michel Constantin of University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand (France) and colleagues in the Azurea network.

The researchers recruited 119 consecutive ARDS patients from 10 intensive care units in France. They measured plasma levels of sRAGE, plasminogen activator inhibitor–1 (PAI-1), soluble intercellular adhesion molecule–1, and surfactant protein–D within 24 hours of ARDS onset. Each patient underwent a lung CT scan within 48 hours to assess focal versus nonfocal lung morphology.

Twenty-seven percent of patients had focal ARDS, while 73% were categorized as nonfocal. Mean plasma levels of sRAGE were much higher in nonfocal patients (3,074 pg/ml vs. 877 pg/ml, P less than .001). A cutoff value of 1,188 ng/ml distinguished focal and nonfocal ARDS with a sensitivity of 93% (95% confidence interval, 85%-97%) and a specificity of 84% (95% CI, 66%-95%). The test’s positive predictive value was 94% (95% CI, 87%-98%), and its negative predictive value was 81% (95% CI, 64%-93%).

The research is still in its early stage, but has a couple possible applications, according to Daniel R. Ouellette, MD, of Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit. “We might conceive of using this as a marker for nonfocal ARDS, and potentially use it to identify patients with worse outcomes. The other thing is, it may be a clue to help us learn about the underlying physiology of the disease,” he said in an interview.

If physicians can confidently categorize a patient, it could inform treatment. “We know that patients who have diffuse disease may be more likely to be treated successfully with advanced ventilator techniques. These techniques would be more useful and likely to lead to recovery in patients that don’t have focal disease,” said Dr. Ouellette.

However, he added that more research is needed. “These results are exciting, but they are very preliminary,” Dr Ouellette said.

The study was funded by the Auvergne Regional Council, the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche, and the Direction Generale de l’Offre de Soins, and the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand. The authors reported receiving funds from various pharmaceutical companies.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At a cutoff of 1,188 pg/ml, the sRAGE blood test differentiated between focal and nonfocal ARDS with a 94% sensitivity and an 84% specificity.

Data source: A prospective multicenter cohort study.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Auvergne Regional Council, the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche, and the Direction Generale de l’Offre de Soins, and the University Hospital of Clermont-Ferrand. The authors reported receiving funds from various pharmaceutical companies.

Arthroscopic Transosseous and Transosseous-Equivalent Rotator Cuff Repair: An Analysis of Cost, Operative Time, and Clinical Outcomes

The rate of medical visits for rotator cuff pathology and the US incidence of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) have increased over the past 10 years.1 The increased use of RCR has been justified with improved patient outcomes.2,3 Advances in surgical techniques and instrumentation have contributed to better outcomes for patients with rotator cuff pathology.3-5 Several studies have validated RCR with functional outcome measures, cost–benefit analysis, and health-related quality-of-life measurements.6-9

Healthcare reimbursement models are being changed to include capitated care, pay for performance, and penalties.10 Given the changing healthcare climate and the increasing incidence of RCR, it is becoming increasingly important for orthopedic surgeons to critically evaluate and modify their practice and procedures to decrease costs without compromising outcomes.11 RCR outcome studies have focused on comparing open/mini-open with arthroscopic techniques, and single-row with double-row techniques, among others.4,12-18 Furthermore, several studies on the cost-effectiveness of these surgical techniques have been conducted.19-21Arthroscopic anchorless (transosseous [TO]) RCR, which is increasingly popular,22 combines the minimal invasiveness of arthroscopic procedures with the biomechanical strength of open TO repair. In addition, this technique avoids the potential complications and costs associated with suture anchors, such as anchor pullout and greater tuberosity osteolysis.22,23 Several studies have documented the effectiveness of this technique.24-26 Biomechanical and clinical outcome data supporting arthroscopic TO-RCR have been published, but there are no reports of studies that have analyzed the cost savings associated with this technique.

In this study, we compared implant costs associated with arthroscopic TO-RCR and arthroscopic TO-equivalent (TOE) RCR. We also evaluated these techniques’ operative time and outcomes. Our hypothesis was that arthroscopic TO-RCR can be performed at lower cost and without increasing operative time or compromising outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Our Institutional Review Board approved this study. Between February 2013 and January 2014, participating surgeons performed 43 arthroscopic TO-RCRs that met the study’s inclusion criteria. Twenty-one of the 43 patients enrolled and became the study group. The control group of 21 patients, who underwent arthroscopic TOE-RCR the preceding year (between January 2012 and January 2013), was matched to the study group on tear size and concomitant procedures, including biceps treatment, labral treatment, acromioplasty, and distal clavicle excision (Table 1).

The primary outcome measure was implant cost (amount paid by institution). Cost was determined and reported by an independent third party using Cerner Surginet as the operating room documentation system and McKessen Pathways Materials Management System for item pricing.

All arthroscopic RCRs were performed by 1 of 3 orthopedic surgeons fellowship-trained in either sports medicine or shoulder and elbow surgery. Using the Cofield classification,27 the treating surgeon recorded the size of the rotator cuff tear: small (<1 cm), medium (1-3 cm), large (3-5 cm), massive (>5 cm). The surgeon also recorded the number of suture anchors used, repair technique, biceps treatment, execution of subacromial decompression, execution of distal clavicle excision, and intraoperative complications. TO repair surgical technique is described in the next section. TOE repair was double-row repair with suture anchors. The number of suture anchors varied by tear size: small (3 anchors), medium (2-5 anchors), large (4-6 anchors), massive (4-5 anchors).

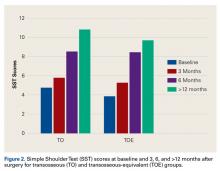

Secondary outcome measures were operative time (time from cut to close) and scores on pain VAS (visual analog scale), SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation), and SST (Simple Shoulder Test). Demographic information was also obtained: age, sex, body mass index, smoking status (Table 1). All patients were asked to fill out questionnaires before surgery and 3, 6, and >12 months after surgery. Outcome surveys were scored by a single research coordinator, who recorded each patient’s outcome scores at the preoperative and postoperative intervals. Follow-up of >12 months was reached by 17 (81%) of the 21 TO patients and 14 (67%) of the 21 TOE patients. For >12 months, the overall rate of follow-up was 74%.

All patients followed the same postoperative rehabilitation protocol: sling immobilization with pendulums for 6 weeks starting at 2 weeks, passive range of motion starting at 6 weeks, and active range of motion starting at 8 weeks. At 3 months, they were allowed progressive resistant exercises with a 10-pound limit, and at 4.5 months they progressed to a 20-pound limit. At 6 months, they were cleared for discharge.

Surgical Technique: Arthroscopic Transosseous Repair

Surgery was performed with the patient in either the beach-chair position or the lateral decubitus position, based on surgeon preference. Our technique is similar to what has been described in the past.22,28 The glenohumeral joint is accessed through a standard posterior portal, followed by an anterior accessory portal through the rotator interval. Standard diagnostic arthroscopy is performed and intra-articular pathology addressed. Next, the scope is placed in the subacromial space through the posterior portal. A lateral subacromial portal is established and cannulated, and a bursectomy performed. The scope is then placed in a posterolateral portal for better visualization of the rotator cuff tear. The greater tuberosity is débrided with a curette to prepare the bed for repair. An ArthroTunneler (Tornier) is used to pass sutures through the greater tuberosity. For standard 2-tunnel repair, 3 sutures are placed through each tunnel. All 6 sutures are next passed (using a suture passer) through the rotator cuff. The second and fifth suture ends that are passed through the cuff are brought out through the cannula and tied together. They are then brought into the shoulder by pulling on the opposite ends and tied alongside the greater tuberosity to create a box stitch. The box stitch acts as a medial row fixation and as a rip stitch that strengthens the vertical mattress sutures against pullout. The other 4 sutures are tied in vertical mattress configuration.

Statistical Analysis

After obtaining the TO and TOE implant costs, we compared them using a generalized linear model with negative binomial distribution and an identity link function so returned parameters were in additive dollars. This comparison included evaluation of tear size and concomitant procedures. Operative times for TO and TOE were obtained and evaluated, and then compared using time-to-event analysis and the log-rank test. Outcome scores were obtained from patients at baseline and 3, 6, and >12 months after surgery and were compared using a linear mixed model that identified change in outcome scores over time, and difference in outcome scores between the TO and TOE groups.

Results

Table 1 lists patient demographics, including age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, and concomitant procedures. The TO and TOE groups had identical tear-size distributions. In addition, they had similar numbers of concomitant procedures, though our study was underpowered to confirm equivalence. Treatment techniques differed: more biceps tenodesis cases in the TO group (n = 12) than in the TOE group (n = 2) and more biceps tenotomy cases in the TOE group (n = 8) than in the TO group (n = 1).

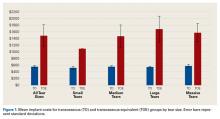

TO implant cost was significantly lower than TOE implant cost for all tear sizes and independent of concomitant procedures (Figure 1).

Operative time was not significantly different between the TO and TOE groups. Mean (SD) operative time was 82.38 (24.09) minutes for the TO group and 81.71 (17.27) minutes for the TOE group. With all other factors controlled, mean operative time was 5.96 minutes shorter for the TOE group, but the difference was not significant (P = .549).

There was no significant difference in preoperative pain VAS (P = .93), SANE (P = .35), or SST (P = .36) scores between the TO and TOE groups.

Discussion

RCR is one of the most common orthopedic surgical procedures, and its use has increased over the past decade.9,21 This increase coincides with the emergence of new repair techniques and implants. These advancements come at a cost. Given the increasingly cost-conscious healthcare environment and its changing reimbursement models, now surgeons must evaluate the economics of their surgical procedures in an attempt to decrease costs without compromising outcomes. We hypothesized that arthroscopic TO-RCR can be performed at lower cost relative to arthroscopic TOE-RCR and without increasing operative time or compromising short-term outcomes.

Studies on the cost-effectiveness of different RCR techniques have been conducted.19-21 Adla and colleagues19 found that open RCR was more cost-effective than arthroscopic RCR, with most of the difference attributable to disposables and suture anchors. Genuario and colleagues21 found that double-row RCR was not as cost-effective as single-row RCR in treating tears of any size. They attributed the difference to 2 more anchors and about 15 more minutes in the operating room.

The increased interest in healthcare costs and the understanding that a substantial part of the cost of arthroscopic RCR is attributable to implants (suture anchors, specifically) led to recent efforts to eliminate the need for anchors. Newly available instrumentation was designed to assist in arthroscopic anchorless repair constructs using the concepts of traditional TO repair.22 Although still considered to be the RCR gold standard, TO fixation has been used less often in recent years, owing to the shift from open to arthroscopic surgery.24 Arthroscopic TO-RCR allows for all the benefits of arthroscopic surgery, plus the biological and mechanical benefits of traditional open or mini-open TO repair. In addition, this technique eliminates the cost of anchors. Kummer and colleagues25 confirmed with biomechanical testing that arthroscopic TO repair and double-row TOE repair are similar in strength, with a trend of less tendon displacement in the TO group.

Our study results support the hypothesis that arthroscopic TO repair provides significant cost savings over tear size–matched arthroscopic TOE repair. Implant cost was substantially higher for TOE repair than for TO repair. Mean (SD) total savings of $946.91 ($100.70) (P < .0001) can be realized performing TO rather than TOE repair. In the United States, where about 250,000 RCRs are performed each year, the use of TO repair would result in an annual savings of almost $250 million.6Operative time was analyzed as well. Running an operating room in the United States costs an estimated $62 per minute (range, $22-$133 per minute).29 Much of this cost is indirect, unrelated to the surgery (eg, capital investment, personnel, insurance), and is being paid even when the operating room is not in use. Therefore, for the hospital’s bottom line, operative time savings are less important than direct cost savings (supplies, implants). However, operative time has more of an effect on the surgeon’s bottom line, and longer procedures reduce the number of surgeries that can be performed and billed. We found no significant difference in operative time between TO and TOE repairs. Critical evaluation revealed that operative time was 5.96 minutes shorter for TOE repairs, but this difference was not significant (P = .677).

Our study results showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes between TO and TOE repair patients. Both groups’ outcome scores improved. At all follow-ups, both groups’ VAS, SANE, and SST scores were significantly improved. Overall, this is the first study to validate the proposed cost benefit of arthroscopic TO repair and confirm no compromise in patient outcomes.

This study had limitations. First, it enrolled relatively few patients, particularly those with small tears. In addition, despite the fact that patients were matched on tear size and concomitant procedures, the groups differed in their biceps pathology treatments. Of the 13 TO patients who had biceps treatment, 12 underwent tenodesis (1 had tenotomy); in contrast, of the 10 TOE patients who had biceps treatment, only 2 underwent tenodesis (8 had tenotomy). The difference is explained by the consecutive course of this study and the increasing popularity of tenodesis over tenotomy. The TOE group underwent surgery before the TO group did, at a time when the involved surgeons were routinely performing tenotomy more than tenodesis. We did not include the costs of implants related to biceps treatment in our analysis, as our focus was on the implant cost of RCR. As for operative time, biceps tenodesis would be expected to extend surgery and potentially affect the comparison of operative times between the TO and TOE groups. However, despite the fact that 12 of the 13 TO patients underwent biceps tenodesis, there was no significant difference in overall operative time. Last, regarding the effect of biceps treatment on clinical outcomes, there are no data showing improved outcomes with tenodesis over tenotomy in the setting of RCR.

A final limitation is lack of data from longer term (>12 months) follow-up for all patients. Our analysis included cost and operative time data for all 42 enrolled patients, but our clinical outcome data represent only 74% of the patients enrolled. Eleven of the 42 patients were lost to follow-up at >12 months, and outcome scores could not be obtained, despite multiple attempts at contact (phone, mail, email). The study design and primary outcome variable focused on cost analysis rather than clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, our data support our hypothesis that there is no difference in clinical outcomes between TO and TOE repairs.

Conclusion

Arthroscopic TO-RCR provides significant cost savings over arthroscopic TOE-RCR without increasing operative time or compromising outcomes. Arthroscopic TO-RCR may have an important role in the evolving healthcare environment and its changing reimbursement models.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E415-E420. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, Moskowitz A, Flatow EL. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(3):227-233.

2. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):163-167.

3. Wolf BR, Dunn WR, Wright RW. Indications for repair of full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(6):1007-1016.

4. Yamaguchi K, Ball CM, Galatz LM. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: transition from mini-open to all-arthroscopic. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;(390):83-94.

5. Yamaguchi K, Levine WN, Marra G, Galatz LM, Klepps S, Flatow EL. Transitioning to arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: the pros and cons. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:81-92.

6. Mather RC 3rd, Koenig L, Acevedo D, et al. The societal and economic value of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):1993-2000.

7. Milne JC, Gartsman GM. Cost of shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3(5):295-298.

8. Savoie FH 3rd, Field LD, Jenkins RN. Costs analysis of successful rotator cuff repair surgery: an outcome study. Comparison of gatekeeper system in surgical patients. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(6):672-676.

9. Vitale MA, Vitale MG, Zivin JG, Braman JP, Bigliani LU, Flatow EL. Rotator cuff repair: an analysis of utility scores and cost-effectiveness. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(2):181-187.

10. Ihejirika RC, Sathiyakumar V, Thakore RV, et al. Healthcare reimbursement models and orthopaedic trauma: will there be change in patient management? A survey of orthopaedic surgeons. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(2):e79-e84.

11. Black EM, Higgins LD, Warner JJ. Value-based shoulder surgery: practicing outcomes-driven, cost-conscious care. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):1000-1009.

12. Barber FA, Hapa O, Bynum JA. Comparative testing by cyclic loading of rotator cuff suture anchors containing multiple high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 suppl):S134-S141.

13. Barros RM, Matos MA, Ferreira Neto AA, et al. Biomechanical evaluation on tendon reinsertion by comparing trans-osseous suture and suture anchor at different stages of healing: experimental study on rabbits. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(6):878-883.

14. Cole BJ, ElAttrache NS, Anbari A. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: an anatomic and biomechanical rationale for different suture-anchor repair configurations. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(6):662-669.

15. Ghodadra NS, Provencher MT, Verma NN, Wilk KE, Romeo AA. Open, mini-open, and all-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair surgery: indications and implications for rehabilitation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2009;39(2):81-89.

16. Pietschmann MF, Fröhlich V, Ficklscherer A, et al. Pullout strength of suture anchors in comparison with transosseous sutures for rotator cuff repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16(5):504-510.

17. van der Zwaal P, Thomassen BJ, Nieuwenhuijse MJ, Lindenburg R, Swen JW, van Arkel ER. Clinical outcome in all-arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair in small to medium-sized tears: a randomized controlled trial in 100 patients with 1-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(2):266-273.

18. Wang VM, Wang FC, McNickle AG, et al. Medial versus lateral supraspinatus tendon properties: implications for double-row rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(12):2456-2463.

19. Adla DN, Rowsell M, Pandey R. Cost-effectiveness of open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):258-261.

20. Churchill RS, Ghorai JK. Total cost and operating room time comparison of rotator cuff repair techniques at low, intermediate, and high volume centers: mini-open versus all-arthroscopic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(5):716-721.

21. Genuario JW, Donegan RP, Hamman D, et al. The cost-effectiveness of single-row compared with double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(15):1369-1377.

22. Garofalo R, Castagna A, Borroni M, Krishnan SG. Arthroscopic transosseous (anchorless) rotator cuff repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(6):1031-1035.

23. Benson EC, MacDermid JC, Drosdowech DS, Athwal GS. The incidence of early metallic suture anchor pullout after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(3):310-315.

24. Baudi P, Rasia Dani E, Campochiaro G, Rebuzzi M, Serafini F, Catani F. The rotator cuff tear repair with a new arthroscopic transosseous system: the Sharc-FT®. Musculoskelet Surg. 2013;97(suppl 1):57-61.

25. Kummer FJ, Hahn M, Day M, Meislin RJ, Jazrawi LM. A laboratory comparison of a new arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair to a double row transosseous equivalent rotator cuff repair using suture anchors. Bull Hosp Joint Dis. 2013;71(2):128-131.

26. Kuroda S, Ishige N, Mikasa M. Advantages of arthroscopic transosseous suture repair of the rotator cuff without the use of anchors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(11):3514-3522.

27. Cofield RH. Subscapular muscle transposition for repair of chronic rotator cuff tears. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;154(5):667-672.

28. Paxton ES, Lazarus MD. Arthroscopic transosseous rotator cuff repair. Orthop Knowledge Online J. 2014;12(2). http://orthoportal.aaos.org/oko/article.aspx?article=OKO_SHO052#article. Accessed October 4, 2016.

29. Macario A. What does one minute of operating room time cost? J Clin Anesth. 2010;22(4):233-236.

The rate of medical visits for rotator cuff pathology and the US incidence of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) have increased over the past 10 years.1 The increased use of RCR has been justified with improved patient outcomes.2,3 Advances in surgical techniques and instrumentation have contributed to better outcomes for patients with rotator cuff pathology.3-5 Several studies have validated RCR with functional outcome measures, cost–benefit analysis, and health-related quality-of-life measurements.6-9

Healthcare reimbursement models are being changed to include capitated care, pay for performance, and penalties.10 Given the changing healthcare climate and the increasing incidence of RCR, it is becoming increasingly important for orthopedic surgeons to critically evaluate and modify their practice and procedures to decrease costs without compromising outcomes.11 RCR outcome studies have focused on comparing open/mini-open with arthroscopic techniques, and single-row with double-row techniques, among others.4,12-18 Furthermore, several studies on the cost-effectiveness of these surgical techniques have been conducted.19-21Arthroscopic anchorless (transosseous [TO]) RCR, which is increasingly popular,22 combines the minimal invasiveness of arthroscopic procedures with the biomechanical strength of open TO repair. In addition, this technique avoids the potential complications and costs associated with suture anchors, such as anchor pullout and greater tuberosity osteolysis.22,23 Several studies have documented the effectiveness of this technique.24-26 Biomechanical and clinical outcome data supporting arthroscopic TO-RCR have been published, but there are no reports of studies that have analyzed the cost savings associated with this technique.

In this study, we compared implant costs associated with arthroscopic TO-RCR and arthroscopic TO-equivalent (TOE) RCR. We also evaluated these techniques’ operative time and outcomes. Our hypothesis was that arthroscopic TO-RCR can be performed at lower cost and without increasing operative time or compromising outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Our Institutional Review Board approved this study. Between February 2013 and January 2014, participating surgeons performed 43 arthroscopic TO-RCRs that met the study’s inclusion criteria. Twenty-one of the 43 patients enrolled and became the study group. The control group of 21 patients, who underwent arthroscopic TOE-RCR the preceding year (between January 2012 and January 2013), was matched to the study group on tear size and concomitant procedures, including biceps treatment, labral treatment, acromioplasty, and distal clavicle excision (Table 1).

The primary outcome measure was implant cost (amount paid by institution). Cost was determined and reported by an independent third party using Cerner Surginet as the operating room documentation system and McKessen Pathways Materials Management System for item pricing.

All arthroscopic RCRs were performed by 1 of 3 orthopedic surgeons fellowship-trained in either sports medicine or shoulder and elbow surgery. Using the Cofield classification,27 the treating surgeon recorded the size of the rotator cuff tear: small (<1 cm), medium (1-3 cm), large (3-5 cm), massive (>5 cm). The surgeon also recorded the number of suture anchors used, repair technique, biceps treatment, execution of subacromial decompression, execution of distal clavicle excision, and intraoperative complications. TO repair surgical technique is described in the next section. TOE repair was double-row repair with suture anchors. The number of suture anchors varied by tear size: small (3 anchors), medium (2-5 anchors), large (4-6 anchors), massive (4-5 anchors).

Secondary outcome measures were operative time (time from cut to close) and scores on pain VAS (visual analog scale), SANE (Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation), and SST (Simple Shoulder Test). Demographic information was also obtained: age, sex, body mass index, smoking status (Table 1). All patients were asked to fill out questionnaires before surgery and 3, 6, and >12 months after surgery. Outcome surveys were scored by a single research coordinator, who recorded each patient’s outcome scores at the preoperative and postoperative intervals. Follow-up of >12 months was reached by 17 (81%) of the 21 TO patients and 14 (67%) of the 21 TOE patients. For >12 months, the overall rate of follow-up was 74%.

All patients followed the same postoperative rehabilitation protocol: sling immobilization with pendulums for 6 weeks starting at 2 weeks, passive range of motion starting at 6 weeks, and active range of motion starting at 8 weeks. At 3 months, they were allowed progressive resistant exercises with a 10-pound limit, and at 4.5 months they progressed to a 20-pound limit. At 6 months, they were cleared for discharge.

Surgical Technique: Arthroscopic Transosseous Repair

Surgery was performed with the patient in either the beach-chair position or the lateral decubitus position, based on surgeon preference. Our technique is similar to what has been described in the past.22,28 The glenohumeral joint is accessed through a standard posterior portal, followed by an anterior accessory portal through the rotator interval. Standard diagnostic arthroscopy is performed and intra-articular pathology addressed. Next, the scope is placed in the subacromial space through the posterior portal. A lateral subacromial portal is established and cannulated, and a bursectomy performed. The scope is then placed in a posterolateral portal for better visualization of the rotator cuff tear. The greater tuberosity is débrided with a curette to prepare the bed for repair. An ArthroTunneler (Tornier) is used to pass sutures through the greater tuberosity. For standard 2-tunnel repair, 3 sutures are placed through each tunnel. All 6 sutures are next passed (using a suture passer) through the rotator cuff. The second and fifth suture ends that are passed through the cuff are brought out through the cannula and tied together. They are then brought into the shoulder by pulling on the opposite ends and tied alongside the greater tuberosity to create a box stitch. The box stitch acts as a medial row fixation and as a rip stitch that strengthens the vertical mattress sutures against pullout. The other 4 sutures are tied in vertical mattress configuration.

Statistical Analysis

After obtaining the TO and TOE implant costs, we compared them using a generalized linear model with negative binomial distribution and an identity link function so returned parameters were in additive dollars. This comparison included evaluation of tear size and concomitant procedures. Operative times for TO and TOE were obtained and evaluated, and then compared using time-to-event analysis and the log-rank test. Outcome scores were obtained from patients at baseline and 3, 6, and >12 months after surgery and were compared using a linear mixed model that identified change in outcome scores over time, and difference in outcome scores between the TO and TOE groups.

Results

Table 1 lists patient demographics, including age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, and concomitant procedures. The TO and TOE groups had identical tear-size distributions. In addition, they had similar numbers of concomitant procedures, though our study was underpowered to confirm equivalence. Treatment techniques differed: more biceps tenodesis cases in the TO group (n = 12) than in the TOE group (n = 2) and more biceps tenotomy cases in the TOE group (n = 8) than in the TO group (n = 1).

TO implant cost was significantly lower than TOE implant cost for all tear sizes and independent of concomitant procedures (Figure 1).

Operative time was not significantly different between the TO and TOE groups. Mean (SD) operative time was 82.38 (24.09) minutes for the TO group and 81.71 (17.27) minutes for the TOE group. With all other factors controlled, mean operative time was 5.96 minutes shorter for the TOE group, but the difference was not significant (P = .549).

There was no significant difference in preoperative pain VAS (P = .93), SANE (P = .35), or SST (P = .36) scores between the TO and TOE groups.

Discussion

RCR is one of the most common orthopedic surgical procedures, and its use has increased over the past decade.9,21 This increase coincides with the emergence of new repair techniques and implants. These advancements come at a cost. Given the increasingly cost-conscious healthcare environment and its changing reimbursement models, now surgeons must evaluate the economics of their surgical procedures in an attempt to decrease costs without compromising outcomes. We hypothesized that arthroscopic TO-RCR can be performed at lower cost relative to arthroscopic TOE-RCR and without increasing operative time or compromising short-term outcomes.

Studies on the cost-effectiveness of different RCR techniques have been conducted.19-21 Adla and colleagues19 found that open RCR was more cost-effective than arthroscopic RCR, with most of the difference attributable to disposables and suture anchors. Genuario and colleagues21 found that double-row RCR was not as cost-effective as single-row RCR in treating tears of any size. They attributed the difference to 2 more anchors and about 15 more minutes in the operating room.

The increased interest in healthcare costs and the understanding that a substantial part of the cost of arthroscopic RCR is attributable to implants (suture anchors, specifically) led to recent efforts to eliminate the need for anchors. Newly available instrumentation was designed to assist in arthroscopic anchorless repair constructs using the concepts of traditional TO repair.22 Although still considered to be the RCR gold standard, TO fixation has been used less often in recent years, owing to the shift from open to arthroscopic surgery.24 Arthroscopic TO-RCR allows for all the benefits of arthroscopic surgery, plus the biological and mechanical benefits of traditional open or mini-open TO repair. In addition, this technique eliminates the cost of anchors. Kummer and colleagues25 confirmed with biomechanical testing that arthroscopic TO repair and double-row TOE repair are similar in strength, with a trend of less tendon displacement in the TO group.

Our study results support the hypothesis that arthroscopic TO repair provides significant cost savings over tear size–matched arthroscopic TOE repair. Implant cost was substantially higher for TOE repair than for TO repair. Mean (SD) total savings of $946.91 ($100.70) (P < .0001) can be realized performing TO rather than TOE repair. In the United States, where about 250,000 RCRs are performed each year, the use of TO repair would result in an annual savings of almost $250 million.6Operative time was analyzed as well. Running an operating room in the United States costs an estimated $62 per minute (range, $22-$133 per minute).29 Much of this cost is indirect, unrelated to the surgery (eg, capital investment, personnel, insurance), and is being paid even when the operating room is not in use. Therefore, for the hospital’s bottom line, operative time savings are less important than direct cost savings (supplies, implants). However, operative time has more of an effect on the surgeon’s bottom line, and longer procedures reduce the number of surgeries that can be performed and billed. We found no significant difference in operative time between TO and TOE repairs. Critical evaluation revealed that operative time was 5.96 minutes shorter for TOE repairs, but this difference was not significant (P = .677).

Our study results showed no significant difference in clinical outcomes between TO and TOE repair patients. Both groups’ outcome scores improved. At all follow-ups, both groups’ VAS, SANE, and SST scores were significantly improved. Overall, this is the first study to validate the proposed cost benefit of arthroscopic TO repair and confirm no compromise in patient outcomes.

This study had limitations. First, it enrolled relatively few patients, particularly those with small tears. In addition, despite the fact that patients were matched on tear size and concomitant procedures, the groups differed in their biceps pathology treatments. Of the 13 TO patients who had biceps treatment, 12 underwent tenodesis (1 had tenotomy); in contrast, of the 10 TOE patients who had biceps treatment, only 2 underwent tenodesis (8 had tenotomy). The difference is explained by the consecutive course of this study and the increasing popularity of tenodesis over tenotomy. The TOE group underwent surgery before the TO group did, at a time when the involved surgeons were routinely performing tenotomy more than tenodesis. We did not include the costs of implants related to biceps treatment in our analysis, as our focus was on the implant cost of RCR. As for operative time, biceps tenodesis would be expected to extend surgery and potentially affect the comparison of operative times between the TO and TOE groups. However, despite the fact that 12 of the 13 TO patients underwent biceps tenodesis, there was no significant difference in overall operative time. Last, regarding the effect of biceps treatment on clinical outcomes, there are no data showing improved outcomes with tenodesis over tenotomy in the setting of RCR.

A final limitation is lack of data from longer term (>12 months) follow-up for all patients. Our analysis included cost and operative time data for all 42 enrolled patients, but our clinical outcome data represent only 74% of the patients enrolled. Eleven of the 42 patients were lost to follow-up at >12 months, and outcome scores could not be obtained, despite multiple attempts at contact (phone, mail, email). The study design and primary outcome variable focused on cost analysis rather than clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, our data support our hypothesis that there is no difference in clinical outcomes between TO and TOE repairs.

Conclusion

Arthroscopic TO-RCR provides significant cost savings over arthroscopic TOE-RCR without increasing operative time or compromising outcomes. Arthroscopic TO-RCR may have an important role in the evolving healthcare environment and its changing reimbursement models.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E415-E420. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

The rate of medical visits for rotator cuff pathology and the US incidence of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR) have increased over the past 10 years.1 The increased use of RCR has been justified with improved patient outcomes.2,3 Advances in surgical techniques and instrumentation have contributed to better outcomes for patients with rotator cuff pathology.3-5 Several studies have validated RCR with functional outcome measures, cost–benefit analysis, and health-related quality-of-life measurements.6-9