User login

GAP malaria vaccine shows early promise

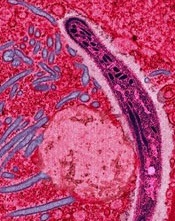

Image from Margaret Shear

and Ute Frevert

A next-generation malaria vaccine that uses genetically attenuated parasites (GAPs) has demonstrated promise in a phase 1 trial and in experiments with mice, according to researchers.

The team generated a genetically attenuated Plasmodium falciparum parasite by knocking out 3 genes that are required for the parasite to cause malaria in humans.

Healthy volunteers infected with this parasite, Pf GAP3KO, exhibited strong antibody responses, according to researchers, and experienced only mild or moderate adverse events (AEs).

When antibodies from these patients were transferred to humanized mice, they inhibited malaria infection in the liver.

The researchers described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

“This most recent publication builds on our previous work,” said study author Sebastian Mikolajczak, PhD, of the Center for Infectious Disease Research in Seattle, Washington.

“We had already good indicators in preclinical studies that this new ‘triple knock-out’ GAP (GAP3KO), which has 3 genes removed, is completely attenuated. The clinical study now shows that the GAP3KO vaccine is completely attenuated in humans and also shows that, even after only a single administration, it elicits a robust immune response against the malaria parasite. Together, these findings are critical milestones for malaria vaccine development.”

Dr Mikolajczak and his colleagues created GAP3KO by knocking out 3 genes in P falciparum that are required for the parasite to successfully infect and cause disease in humans—Pf p52−/p36−/sap1−.

The researchers then tested Pf GAP3KO sporozoites in 10 healthy human volunteers. The sporozoites were delivered via bites from infected mosquitoes.

All subjects experienced grade 1 AEs, and 70% had grade 2 AEs. There were no grade 3 or higher AEs.

Grade 2 AEs included 1 case of fatigue and several cases of administration-site reactions, including erythema (n=6), pruritus (n=2), and swelling (n=3).

All 10 volunteers completed the 28-day study period without exhibiting any symptoms of malaria. They also remained negative for blood-stage parasitemia throughout the study period.

All subjects experienced antibody responses as well. The researchers collected sera from the volunteers on day 0, 7, 13, and 28 after immunization and analyzed it for anti-circumsporozoite protein (CSP) antibody responses.

The team measured anti-CSP immunoglobulin G (IgG) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using full-length recombinant PfCSP protein.

At day 0, volunteers’ sera showed an average of 1436 ± 257.3 arbitrary units (AU) of anti-CSP titers by ELISA. However, 3 volunteers were slightly above the 2000 AU cutoff for positivity.

At day 7, 8 of the 10 volunteers were positive for anti-CSP IgG, with an average titer of 3821 ± 808.1 AU. At day 13, all volunteers were positive, with an average of 11,547 ± 2084 AU. Positivity was maintained through day 28, with an average of 5774± 840 AU.

To determine whether these antibodies could inhibit Pf sporozoite invasion in vivo, the researchers transferred them to FRG huHep liver chimeric humanized mice, which allow for complete development of liver-stage parasites.

The researchers chose 5 volunteers whose immune serum showed high levels of invasion inhibition in vitro and varying CSP IgG titers. The mice received purified IgG from these volunteers from day 0 and day 13 immune samples (5 mice per volunteer per time point).

The mice were then challenged with bites from mosquitoes infected with sporozoites of a green fluorescent protein–luciferase–expressing P falciparum strain.

The researchers calculated inhibition of infection by comparing the liver-stage burden of mice receiving day 13 IgG samples to the mean value of liver-stage burden in mice receiving day 0 IgG samples.

The day 13 IgG samples inhibited liver infection by an average of 23.18 ± 57%, 32.23 ± 29.16%, 69.38 ± 18.64%, 76.63 ± 19.98%, and 87.99 ± 15.56% (per volunteer).

The 3 volunteers whose serum exhibited the highest inhibition had the lowest Pf CSP titers of the 5 samples.

The researchers said these promising results in mice and humans pave the way to a phase 1b trial of the GAP3KO vaccine candidate using controlled human malaria infection. ![]()

Image from Margaret Shear

and Ute Frevert

A next-generation malaria vaccine that uses genetically attenuated parasites (GAPs) has demonstrated promise in a phase 1 trial and in experiments with mice, according to researchers.

The team generated a genetically attenuated Plasmodium falciparum parasite by knocking out 3 genes that are required for the parasite to cause malaria in humans.

Healthy volunteers infected with this parasite, Pf GAP3KO, exhibited strong antibody responses, according to researchers, and experienced only mild or moderate adverse events (AEs).

When antibodies from these patients were transferred to humanized mice, they inhibited malaria infection in the liver.

The researchers described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

“This most recent publication builds on our previous work,” said study author Sebastian Mikolajczak, PhD, of the Center for Infectious Disease Research in Seattle, Washington.

“We had already good indicators in preclinical studies that this new ‘triple knock-out’ GAP (GAP3KO), which has 3 genes removed, is completely attenuated. The clinical study now shows that the GAP3KO vaccine is completely attenuated in humans and also shows that, even after only a single administration, it elicits a robust immune response against the malaria parasite. Together, these findings are critical milestones for malaria vaccine development.”

Dr Mikolajczak and his colleagues created GAP3KO by knocking out 3 genes in P falciparum that are required for the parasite to successfully infect and cause disease in humans—Pf p52−/p36−/sap1−.

The researchers then tested Pf GAP3KO sporozoites in 10 healthy human volunteers. The sporozoites were delivered via bites from infected mosquitoes.

All subjects experienced grade 1 AEs, and 70% had grade 2 AEs. There were no grade 3 or higher AEs.

Grade 2 AEs included 1 case of fatigue and several cases of administration-site reactions, including erythema (n=6), pruritus (n=2), and swelling (n=3).

All 10 volunteers completed the 28-day study period without exhibiting any symptoms of malaria. They also remained negative for blood-stage parasitemia throughout the study period.

All subjects experienced antibody responses as well. The researchers collected sera from the volunteers on day 0, 7, 13, and 28 after immunization and analyzed it for anti-circumsporozoite protein (CSP) antibody responses.

The team measured anti-CSP immunoglobulin G (IgG) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using full-length recombinant PfCSP protein.

At day 0, volunteers’ sera showed an average of 1436 ± 257.3 arbitrary units (AU) of anti-CSP titers by ELISA. However, 3 volunteers were slightly above the 2000 AU cutoff for positivity.

At day 7, 8 of the 10 volunteers were positive for anti-CSP IgG, with an average titer of 3821 ± 808.1 AU. At day 13, all volunteers were positive, with an average of 11,547 ± 2084 AU. Positivity was maintained through day 28, with an average of 5774± 840 AU.

To determine whether these antibodies could inhibit Pf sporozoite invasion in vivo, the researchers transferred them to FRG huHep liver chimeric humanized mice, which allow for complete development of liver-stage parasites.

The researchers chose 5 volunteers whose immune serum showed high levels of invasion inhibition in vitro and varying CSP IgG titers. The mice received purified IgG from these volunteers from day 0 and day 13 immune samples (5 mice per volunteer per time point).

The mice were then challenged with bites from mosquitoes infected with sporozoites of a green fluorescent protein–luciferase–expressing P falciparum strain.

The researchers calculated inhibition of infection by comparing the liver-stage burden of mice receiving day 13 IgG samples to the mean value of liver-stage burden in mice receiving day 0 IgG samples.

The day 13 IgG samples inhibited liver infection by an average of 23.18 ± 57%, 32.23 ± 29.16%, 69.38 ± 18.64%, 76.63 ± 19.98%, and 87.99 ± 15.56% (per volunteer).

The 3 volunteers whose serum exhibited the highest inhibition had the lowest Pf CSP titers of the 5 samples.

The researchers said these promising results in mice and humans pave the way to a phase 1b trial of the GAP3KO vaccine candidate using controlled human malaria infection. ![]()

Image from Margaret Shear

and Ute Frevert

A next-generation malaria vaccine that uses genetically attenuated parasites (GAPs) has demonstrated promise in a phase 1 trial and in experiments with mice, according to researchers.

The team generated a genetically attenuated Plasmodium falciparum parasite by knocking out 3 genes that are required for the parasite to cause malaria in humans.

Healthy volunteers infected with this parasite, Pf GAP3KO, exhibited strong antibody responses, according to researchers, and experienced only mild or moderate adverse events (AEs).

When antibodies from these patients were transferred to humanized mice, they inhibited malaria infection in the liver.

The researchers described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

“This most recent publication builds on our previous work,” said study author Sebastian Mikolajczak, PhD, of the Center for Infectious Disease Research in Seattle, Washington.

“We had already good indicators in preclinical studies that this new ‘triple knock-out’ GAP (GAP3KO), which has 3 genes removed, is completely attenuated. The clinical study now shows that the GAP3KO vaccine is completely attenuated in humans and also shows that, even after only a single administration, it elicits a robust immune response against the malaria parasite. Together, these findings are critical milestones for malaria vaccine development.”

Dr Mikolajczak and his colleagues created GAP3KO by knocking out 3 genes in P falciparum that are required for the parasite to successfully infect and cause disease in humans—Pf p52−/p36−/sap1−.

The researchers then tested Pf GAP3KO sporozoites in 10 healthy human volunteers. The sporozoites were delivered via bites from infected mosquitoes.

All subjects experienced grade 1 AEs, and 70% had grade 2 AEs. There were no grade 3 or higher AEs.

Grade 2 AEs included 1 case of fatigue and several cases of administration-site reactions, including erythema (n=6), pruritus (n=2), and swelling (n=3).

All 10 volunteers completed the 28-day study period without exhibiting any symptoms of malaria. They also remained negative for blood-stage parasitemia throughout the study period.

All subjects experienced antibody responses as well. The researchers collected sera from the volunteers on day 0, 7, 13, and 28 after immunization and analyzed it for anti-circumsporozoite protein (CSP) antibody responses.

The team measured anti-CSP immunoglobulin G (IgG) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using full-length recombinant PfCSP protein.

At day 0, volunteers’ sera showed an average of 1436 ± 257.3 arbitrary units (AU) of anti-CSP titers by ELISA. However, 3 volunteers were slightly above the 2000 AU cutoff for positivity.

At day 7, 8 of the 10 volunteers were positive for anti-CSP IgG, with an average titer of 3821 ± 808.1 AU. At day 13, all volunteers were positive, with an average of 11,547 ± 2084 AU. Positivity was maintained through day 28, with an average of 5774± 840 AU.

To determine whether these antibodies could inhibit Pf sporozoite invasion in vivo, the researchers transferred them to FRG huHep liver chimeric humanized mice, which allow for complete development of liver-stage parasites.

The researchers chose 5 volunteers whose immune serum showed high levels of invasion inhibition in vitro and varying CSP IgG titers. The mice received purified IgG from these volunteers from day 0 and day 13 immune samples (5 mice per volunteer per time point).

The mice were then challenged with bites from mosquitoes infected with sporozoites of a green fluorescent protein–luciferase–expressing P falciparum strain.

The researchers calculated inhibition of infection by comparing the liver-stage burden of mice receiving day 13 IgG samples to the mean value of liver-stage burden in mice receiving day 0 IgG samples.

The day 13 IgG samples inhibited liver infection by an average of 23.18 ± 57%, 32.23 ± 29.16%, 69.38 ± 18.64%, 76.63 ± 19.98%, and 87.99 ± 15.56% (per volunteer).

The 3 volunteers whose serum exhibited the highest inhibition had the lowest Pf CSP titers of the 5 samples.

The researchers said these promising results in mice and humans pave the way to a phase 1b trial of the GAP3KO vaccine candidate using controlled human malaria infection. ![]()

IHS Gets Emergency Help

An “innovative collaboration” will bring best practices of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) to 26 emergency departments (EDs) in rural and remote Native communities. The IHS and ACEP are building on “the aggressive strategy at IHS to improve quality health care,” said IHS Principal Deputy Director Mary Smith.

Related: Dangerous Staff Shortages in the IHS

Top-level physicians and emergency medical professionals will share training resources and knowledge of telehealth and emergency care. At a work session in Winnebago, Nevada, participants covered topics, including ED leadership; responsibility, accountability, workflow, and workforce issues in rural facilities; how emergency telemedicine can help meet rural health care needs; and identifying areas for leveraging resources.

The new partnership’s plans dovetail with the Quality Framework, announced in November, which “provides a road map for quality at every level of IHS,” Smith said. The Quality Framework is the brainchild of experts from IHS, tribal partners, and HHS. Specific objectives include promoting a culture of patient safety in which all staff feel comfortable reporting medical errors, instituting processes to support learning from experiences, and reducing patient wait times for appointments.

Related: Pharmacists in the Emergency Department: Feasibility and Cost

The Quality Framework is but one product of a year in which IHS has been collaborating with tribal leaders and local health partners on a series of actions “to aggressively confront some long-standing health care service challenges.” Other actions include awarding a contract to the Joint Commission for accreditation services, technical assistance and training, and a contract with Avera Health to expand telehealth and emergency services in the Great Plains.

An “innovative collaboration” will bring best practices of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) to 26 emergency departments (EDs) in rural and remote Native communities. The IHS and ACEP are building on “the aggressive strategy at IHS to improve quality health care,” said IHS Principal Deputy Director Mary Smith.

Related: Dangerous Staff Shortages in the IHS

Top-level physicians and emergency medical professionals will share training resources and knowledge of telehealth and emergency care. At a work session in Winnebago, Nevada, participants covered topics, including ED leadership; responsibility, accountability, workflow, and workforce issues in rural facilities; how emergency telemedicine can help meet rural health care needs; and identifying areas for leveraging resources.

The new partnership’s plans dovetail with the Quality Framework, announced in November, which “provides a road map for quality at every level of IHS,” Smith said. The Quality Framework is the brainchild of experts from IHS, tribal partners, and HHS. Specific objectives include promoting a culture of patient safety in which all staff feel comfortable reporting medical errors, instituting processes to support learning from experiences, and reducing patient wait times for appointments.

Related: Pharmacists in the Emergency Department: Feasibility and Cost

The Quality Framework is but one product of a year in which IHS has been collaborating with tribal leaders and local health partners on a series of actions “to aggressively confront some long-standing health care service challenges.” Other actions include awarding a contract to the Joint Commission for accreditation services, technical assistance and training, and a contract with Avera Health to expand telehealth and emergency services in the Great Plains.

An “innovative collaboration” will bring best practices of the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) to 26 emergency departments (EDs) in rural and remote Native communities. The IHS and ACEP are building on “the aggressive strategy at IHS to improve quality health care,” said IHS Principal Deputy Director Mary Smith.

Related: Dangerous Staff Shortages in the IHS

Top-level physicians and emergency medical professionals will share training resources and knowledge of telehealth and emergency care. At a work session in Winnebago, Nevada, participants covered topics, including ED leadership; responsibility, accountability, workflow, and workforce issues in rural facilities; how emergency telemedicine can help meet rural health care needs; and identifying areas for leveraging resources.

The new partnership’s plans dovetail with the Quality Framework, announced in November, which “provides a road map for quality at every level of IHS,” Smith said. The Quality Framework is the brainchild of experts from IHS, tribal partners, and HHS. Specific objectives include promoting a culture of patient safety in which all staff feel comfortable reporting medical errors, instituting processes to support learning from experiences, and reducing patient wait times for appointments.

Related: Pharmacists in the Emergency Department: Feasibility and Cost

The Quality Framework is but one product of a year in which IHS has been collaborating with tribal leaders and local health partners on a series of actions “to aggressively confront some long-standing health care service challenges.” Other actions include awarding a contract to the Joint Commission for accreditation services, technical assistance and training, and a contract with Avera Health to expand telehealth and emergency services in the Great Plains.

White spots on back

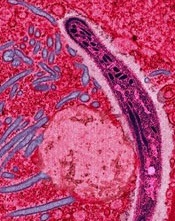

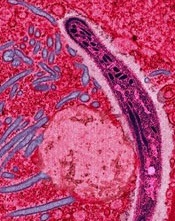

The FP considered the diagnoses of vitiligo and tinea versicolor. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and saw the “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern of Malassezia furfur. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The “spaghetti” or “ziti” is the short mycelial form of M furfur and the “meatballs” are the round yeast form (Pityrosporum).

This was definitive proof that the patient had tinea versicolor caused by M furfur, a lipophilic yeast that can be found on healthy skin. Tinea versicolor starts when the yeast that normally colonizes the skin changes from the round form to the pathologic mycelial form and then invades the stratum corneum. M furfur thrives on sebum and moisture and tends to grow on the skin in areas where there are sebaceous follicles secreting sebum. Patients with tinea versicolor present with skin discolorations that are white, pink, or brown.

The patient in this case chose a single oral dose of 400 mg fluconazole to be repeated one week later. The condition cleared and the patient's skin color returned to normal in the following months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Tinea versicolor. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:566-569.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered the diagnoses of vitiligo and tinea versicolor. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and saw the “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern of Malassezia furfur. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The “spaghetti” or “ziti” is the short mycelial form of M furfur and the “meatballs” are the round yeast form (Pityrosporum).

This was definitive proof that the patient had tinea versicolor caused by M furfur, a lipophilic yeast that can be found on healthy skin. Tinea versicolor starts when the yeast that normally colonizes the skin changes from the round form to the pathologic mycelial form and then invades the stratum corneum. M furfur thrives on sebum and moisture and tends to grow on the skin in areas where there are sebaceous follicles secreting sebum. Patients with tinea versicolor present with skin discolorations that are white, pink, or brown.

The patient in this case chose a single oral dose of 400 mg fluconazole to be repeated one week later. The condition cleared and the patient's skin color returned to normal in the following months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Tinea versicolor. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:566-569.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

The FP considered the diagnoses of vitiligo and tinea versicolor. He performed a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation and saw the “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern of Malassezia furfur. (See a video on how to perform a KOH preparation.) The “spaghetti” or “ziti” is the short mycelial form of M furfur and the “meatballs” are the round yeast form (Pityrosporum).

This was definitive proof that the patient had tinea versicolor caused by M furfur, a lipophilic yeast that can be found on healthy skin. Tinea versicolor starts when the yeast that normally colonizes the skin changes from the round form to the pathologic mycelial form and then invades the stratum corneum. M furfur thrives on sebum and moisture and tends to grow on the skin in areas where there are sebaceous follicles secreting sebum. Patients with tinea versicolor present with skin discolorations that are white, pink, or brown.

The patient in this case chose a single oral dose of 400 mg fluconazole to be repeated one week later. The condition cleared and the patient's skin color returned to normal in the following months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Usatine R. Tinea versicolor. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:566-569.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: usatinemedia.com

Thinking Pimple? That’s Too Simple

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a punch biopsy (choice “b”). This will help establish the exact nature of the problem, which will dictate rational treatment.

The patient doesn’t have acne, so the suggested treatment options (choices “a,” “c,” and “d”) would be of no use. With cryotherapy, furthermore, there is a risk of leaving a permanent blemish on her skin.

DISCUSSION

A sample of one lesion was obtained via 3-mm punch biopsy and the resulting defect closed with a single suture. Pathologic examination showed the specimen to be a vellus hair cyst (VHC). In this case, it was one of many, making the diagnosis eruptive vellus hair cysts.

VHC, which can be acquired or inherited, typically manifests in the first two decades of life. In this developmental abnormality, a gradual disruption occurs between the proximal and distal portions of the vellus hair follicle, usually at the level of the infundibulum. As a result, the characteristic papule (which holds the retained hair) forms and the hair bulb atrophies.

The lesions may be solitary or appear in clusters on the body; they are easily mistaken for acne, milia, or even molluscum. As this case demonstrates, biopsy is often necessary to establish the correct diagnosis.

One final note about biopsy: It is best to incise each lesion with an 18-gauge needle tip or #11 blade and express the contents. This tedious process causes some discomfort for the patient, but it is quite effective and, if done correctly, should not leave a permanent mark on the skin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a punch biopsy (choice “b”). This will help establish the exact nature of the problem, which will dictate rational treatment.

The patient doesn’t have acne, so the suggested treatment options (choices “a,” “c,” and “d”) would be of no use. With cryotherapy, furthermore, there is a risk of leaving a permanent blemish on her skin.

DISCUSSION

A sample of one lesion was obtained via 3-mm punch biopsy and the resulting defect closed with a single suture. Pathologic examination showed the specimen to be a vellus hair cyst (VHC). In this case, it was one of many, making the diagnosis eruptive vellus hair cysts.

VHC, which can be acquired or inherited, typically manifests in the first two decades of life. In this developmental abnormality, a gradual disruption occurs between the proximal and distal portions of the vellus hair follicle, usually at the level of the infundibulum. As a result, the characteristic papule (which holds the retained hair) forms and the hair bulb atrophies.

The lesions may be solitary or appear in clusters on the body; they are easily mistaken for acne, milia, or even molluscum. As this case demonstrates, biopsy is often necessary to establish the correct diagnosis.

One final note about biopsy: It is best to incise each lesion with an 18-gauge needle tip or #11 blade and express the contents. This tedious process causes some discomfort for the patient, but it is quite effective and, if done correctly, should not leave a permanent mark on the skin.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a punch biopsy (choice “b”). This will help establish the exact nature of the problem, which will dictate rational treatment.

The patient doesn’t have acne, so the suggested treatment options (choices “a,” “c,” and “d”) would be of no use. With cryotherapy, furthermore, there is a risk of leaving a permanent blemish on her skin.

DISCUSSION

A sample of one lesion was obtained via 3-mm punch biopsy and the resulting defect closed with a single suture. Pathologic examination showed the specimen to be a vellus hair cyst (VHC). In this case, it was one of many, making the diagnosis eruptive vellus hair cysts.

VHC, which can be acquired or inherited, typically manifests in the first two decades of life. In this developmental abnormality, a gradual disruption occurs between the proximal and distal portions of the vellus hair follicle, usually at the level of the infundibulum. As a result, the characteristic papule (which holds the retained hair) forms and the hair bulb atrophies.

The lesions may be solitary or appear in clusters on the body; they are easily mistaken for acne, milia, or even molluscum. As this case demonstrates, biopsy is often necessary to establish the correct diagnosis.

One final note about biopsy: It is best to incise each lesion with an 18-gauge needle tip or #11 blade and express the contents. This tedious process causes some discomfort for the patient, but it is quite effective and, if done correctly, should not leave a permanent mark on the skin.

A 13-year-old African-American girl is brought in by her mother for evaluation of lesions that manifested on her forehead several years ago. Over time, the lesions have multiplied from just a few papules to a current total of about 30. Attempted treatment with topical benzoyl peroxide and two retinoids (tazarotene and adapalene)—for a presumptive diagnosis of acne—has yielded no improvement.

The lesions are quite obvious but asymptomatic; they are not tender, inflamed, or pustulant. The soft, 2- to 3-mm intradermal papules are grouped in a fairly round 7-cm area of the patient’s forehead. No punctum is seen with any of the lesions.

The child’s type V skin is otherwise clear, with no sign of acne. Her hair, teeth, and nails appear normal. According to her mother, the patient is healthy apart from this eruption.

Bundled payments reduce costs in joint patients

Clinical question: Does bundled payment for lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR) reduce cost without compromising the quality of care?

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: BPCI-participating hospitals.

Synopsis: At BPCI-participating hospitals, there were 29,441 LEJR episodes in the baseline period and 31,700 episodes in the intervention period; these were compared with a control group of 29,440 episodes in the baseline period and 31,696 episodes in the intervention period. The BPCI initiative was associated with a significant reduction in Medicare per-episode payments, which declined by an estimated $1,166 more (95% confidence interval, –$1634 to –$699; P less than .001) for the BPCI group than for the comparison group (between baseline and intervention periods).

There were no statistical differences in claims-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations, which included 30- and 90-day unplanned readmissions, ED visits, and postdischarge mortality.

Bottom line: Bundled payments for joint replacements may have the potential to decrease cost while maintaining quality of care.

Citation: Dummit L, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint e replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: Does bundled payment for lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR) reduce cost without compromising the quality of care?

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: BPCI-participating hospitals.

Synopsis: At BPCI-participating hospitals, there were 29,441 LEJR episodes in the baseline period and 31,700 episodes in the intervention period; these were compared with a control group of 29,440 episodes in the baseline period and 31,696 episodes in the intervention period. The BPCI initiative was associated with a significant reduction in Medicare per-episode payments, which declined by an estimated $1,166 more (95% confidence interval, –$1634 to –$699; P less than .001) for the BPCI group than for the comparison group (between baseline and intervention periods).

There were no statistical differences in claims-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations, which included 30- and 90-day unplanned readmissions, ED visits, and postdischarge mortality.

Bottom line: Bundled payments for joint replacements may have the potential to decrease cost while maintaining quality of care.

Citation: Dummit L, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint e replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: Does bundled payment for lower extremity joint replacement (LEJR) reduce cost without compromising the quality of care?

Study design: Observational study.

Setting: BPCI-participating hospitals.

Synopsis: At BPCI-participating hospitals, there were 29,441 LEJR episodes in the baseline period and 31,700 episodes in the intervention period; these were compared with a control group of 29,440 episodes in the baseline period and 31,696 episodes in the intervention period. The BPCI initiative was associated with a significant reduction in Medicare per-episode payments, which declined by an estimated $1,166 more (95% confidence interval, –$1634 to –$699; P less than .001) for the BPCI group than for the comparison group (between baseline and intervention periods).

There were no statistical differences in claims-based quality measures between the BPCI and comparison populations, which included 30- and 90-day unplanned readmissions, ED visits, and postdischarge mortality.

Bottom line: Bundled payments for joint replacements may have the potential to decrease cost while maintaining quality of care.

Citation: Dummit L, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint e replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316(12):1267-1278.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Myth of the Month: CT scan before lumbar puncture in suspected meningitis?

A 28-year-old male presents to the emergency department with fever and severe headache. He has had a fever for 24 hours. Headache began that morning. On exam, he has marked nuchal rigidity, with a temperature of 103.5° F. He is fully oriented and has a nonfocal neurologic examination.

What would you do?

A) Lumbar puncture (LP).

B) CT scan, then LP.

C) Antibiotics, CT scan, then LP.

D) MRI, then LP.

E) Antibiotics, MRI, then LP.

The practice of obtaining a head CT scan (or MRI) before performing a lumbar puncture (LP) is commonplace in emergency departments. The concern is that if a lumbar puncture is done in a patient with increased intracranial pressure, then brain herniation could occur. How common is brain herniation, are there useful clinical indicators that make a CT scan not helpful, and does this concern reach myth status?

In a retrospective study well before CT scans were available, 401 patients with brain tumors who had LP were reviewed, and 32% of the patients had papilledema.3 There was only one poor outcome because of the LP. This would be considered a high-risk group for complications, because many of these patients had clear focal neurologic signs, and one-third of them had papilledema.

There have been a number of studies looking at whether there is utility in obtaining a CT scan prior to LP in patients with suspected acute bacterial meningitis.

Dr. N.D. Baker of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 112 patients who had a routine CT before LP for suspected meningitis.2 Regardless of CT scan result, all patients received a lumbar puncture. Four patients had mass lesions on CT scan, though none of these patients had an increased opening pressure. No patient had an adverse outcome from LP.

Dr. Paul Greig and Dr. D. Goroszeniuk of Horton General Hospital, Banbury, England, reported on a retrospective study of all patients over a 6-month period considered for a LP.4 A total of 64 LPs were considered; 54 of these patients had a CT before LP. No patients had a bad outcome from the lumbar puncture.

The sensitivity and negative predictive value of a normal neurologic exam were very good in this study, leading to the conclusion from the authors that a normal neurologic exam and fundoscopic exam is an accurate predictor of a normal CT scan. The authors were dismayed that only 45% of the patients in the study received a fundoscopic exam.

Rodrigo Hasbun, MD, formerly of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues did a prospective study of 301 patients with suspected meningitis to see if clinical signs and symptoms could help guide utilization of CT scans.5 A total of 235 patients got CT scans, and 24% were abnormal.

The clinical features associated with higher likelihood of an abnormal CT were age greater than 60 years, immunosuppression, known CNS disease, and a seizure within the past week. On exam, altered mental status, aphasia, and focal neurologic findings were associated with higher likelihood of an abnormal CT scan.

Of the 96 patients who did not have any of these features, 93 had a normal CT exam, giving a negative predictive value of 97%.

No patients in the study had herniation from lumbar puncture. The only patients in the study who had brain herniations were two patients who had severe mass effect on CT, and did not receive lumbar punctures.

I think the patient in this case should have a lumbar puncture and does not need any imaging. I think that there is no reason to get neuroimaging in patients with suspected meningitis who are alert and have a nonfocal neurologic exam, and do not have papilledema.

References

1. Br J Radiol. 1999 Mar;72(855):319.

2. J Emerg Med. 1994 Sep-Oct;12(5):597-601.

3. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1954 Nov;72(5):568-72.

4. Postgrad Med J. 2006 Mar;82(965):162-5.

5. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec 13;345(24):1727-33.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 28-year-old male presents to the emergency department with fever and severe headache. He has had a fever for 24 hours. Headache began that morning. On exam, he has marked nuchal rigidity, with a temperature of 103.5° F. He is fully oriented and has a nonfocal neurologic examination.

What would you do?

A) Lumbar puncture (LP).

B) CT scan, then LP.

C) Antibiotics, CT scan, then LP.

D) MRI, then LP.

E) Antibiotics, MRI, then LP.

The practice of obtaining a head CT scan (or MRI) before performing a lumbar puncture (LP) is commonplace in emergency departments. The concern is that if a lumbar puncture is done in a patient with increased intracranial pressure, then brain herniation could occur. How common is brain herniation, are there useful clinical indicators that make a CT scan not helpful, and does this concern reach myth status?

In a retrospective study well before CT scans were available, 401 patients with brain tumors who had LP were reviewed, and 32% of the patients had papilledema.3 There was only one poor outcome because of the LP. This would be considered a high-risk group for complications, because many of these patients had clear focal neurologic signs, and one-third of them had papilledema.

There have been a number of studies looking at whether there is utility in obtaining a CT scan prior to LP in patients with suspected acute bacterial meningitis.

Dr. N.D. Baker of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 112 patients who had a routine CT before LP for suspected meningitis.2 Regardless of CT scan result, all patients received a lumbar puncture. Four patients had mass lesions on CT scan, though none of these patients had an increased opening pressure. No patient had an adverse outcome from LP.

Dr. Paul Greig and Dr. D. Goroszeniuk of Horton General Hospital, Banbury, England, reported on a retrospective study of all patients over a 6-month period considered for a LP.4 A total of 64 LPs were considered; 54 of these patients had a CT before LP. No patients had a bad outcome from the lumbar puncture.

The sensitivity and negative predictive value of a normal neurologic exam were very good in this study, leading to the conclusion from the authors that a normal neurologic exam and fundoscopic exam is an accurate predictor of a normal CT scan. The authors were dismayed that only 45% of the patients in the study received a fundoscopic exam.

Rodrigo Hasbun, MD, formerly of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues did a prospective study of 301 patients with suspected meningitis to see if clinical signs and symptoms could help guide utilization of CT scans.5 A total of 235 patients got CT scans, and 24% were abnormal.

The clinical features associated with higher likelihood of an abnormal CT were age greater than 60 years, immunosuppression, known CNS disease, and a seizure within the past week. On exam, altered mental status, aphasia, and focal neurologic findings were associated with higher likelihood of an abnormal CT scan.

Of the 96 patients who did not have any of these features, 93 had a normal CT exam, giving a negative predictive value of 97%.

No patients in the study had herniation from lumbar puncture. The only patients in the study who had brain herniations were two patients who had severe mass effect on CT, and did not receive lumbar punctures.

I think the patient in this case should have a lumbar puncture and does not need any imaging. I think that there is no reason to get neuroimaging in patients with suspected meningitis who are alert and have a nonfocal neurologic exam, and do not have papilledema.

References

1. Br J Radiol. 1999 Mar;72(855):319.

2. J Emerg Med. 1994 Sep-Oct;12(5):597-601.

3. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1954 Nov;72(5):568-72.

4. Postgrad Med J. 2006 Mar;82(965):162-5.

5. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec 13;345(24):1727-33.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

A 28-year-old male presents to the emergency department with fever and severe headache. He has had a fever for 24 hours. Headache began that morning. On exam, he has marked nuchal rigidity, with a temperature of 103.5° F. He is fully oriented and has a nonfocal neurologic examination.

What would you do?

A) Lumbar puncture (LP).

B) CT scan, then LP.

C) Antibiotics, CT scan, then LP.

D) MRI, then LP.

E) Antibiotics, MRI, then LP.

The practice of obtaining a head CT scan (or MRI) before performing a lumbar puncture (LP) is commonplace in emergency departments. The concern is that if a lumbar puncture is done in a patient with increased intracranial pressure, then brain herniation could occur. How common is brain herniation, are there useful clinical indicators that make a CT scan not helpful, and does this concern reach myth status?

In a retrospective study well before CT scans were available, 401 patients with brain tumors who had LP were reviewed, and 32% of the patients had papilledema.3 There was only one poor outcome because of the LP. This would be considered a high-risk group for complications, because many of these patients had clear focal neurologic signs, and one-third of them had papilledema.

There have been a number of studies looking at whether there is utility in obtaining a CT scan prior to LP in patients with suspected acute bacterial meningitis.

Dr. N.D. Baker of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues retrospectively reviewed the records of 112 patients who had a routine CT before LP for suspected meningitis.2 Regardless of CT scan result, all patients received a lumbar puncture. Four patients had mass lesions on CT scan, though none of these patients had an increased opening pressure. No patient had an adverse outcome from LP.

Dr. Paul Greig and Dr. D. Goroszeniuk of Horton General Hospital, Banbury, England, reported on a retrospective study of all patients over a 6-month period considered for a LP.4 A total of 64 LPs were considered; 54 of these patients had a CT before LP. No patients had a bad outcome from the lumbar puncture.

The sensitivity and negative predictive value of a normal neurologic exam were very good in this study, leading to the conclusion from the authors that a normal neurologic exam and fundoscopic exam is an accurate predictor of a normal CT scan. The authors were dismayed that only 45% of the patients in the study received a fundoscopic exam.

Rodrigo Hasbun, MD, formerly of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his colleagues did a prospective study of 301 patients with suspected meningitis to see if clinical signs and symptoms could help guide utilization of CT scans.5 A total of 235 patients got CT scans, and 24% were abnormal.

The clinical features associated with higher likelihood of an abnormal CT were age greater than 60 years, immunosuppression, known CNS disease, and a seizure within the past week. On exam, altered mental status, aphasia, and focal neurologic findings were associated with higher likelihood of an abnormal CT scan.

Of the 96 patients who did not have any of these features, 93 had a normal CT exam, giving a negative predictive value of 97%.

No patients in the study had herniation from lumbar puncture. The only patients in the study who had brain herniations were two patients who had severe mass effect on CT, and did not receive lumbar punctures.

I think the patient in this case should have a lumbar puncture and does not need any imaging. I think that there is no reason to get neuroimaging in patients with suspected meningitis who are alert and have a nonfocal neurologic exam, and do not have papilledema.

References

1. Br J Radiol. 1999 Mar;72(855):319.

2. J Emerg Med. 1994 Sep-Oct;12(5):597-601.

3. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1954 Nov;72(5):568-72.

4. Postgrad Med J. 2006 Mar;82(965):162-5.

5. N Engl J Med. 2001 Dec 13;345(24):1727-33.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

Neoadjuvant AI plus Ki67 info could deescalate adjuvant breast cancer treatment

Triage to chemotherapy using a Ki67-based Preoperative Endocrine Prognostic Index (PEPI), which also integrates residual disease burden, appears useful for deescalating adjuvant treatment after neoadjuvant aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy for breast cancer, investigators report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Only 4 of 109 patients (3.7%) in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1031B trial with a PEPI score of 0 relapsed after a median of 5.5 years (and were therefore unlikely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy), compared with 49 (14.4%) of 341 patients with a PEPI score greater than 0 (recurrence hazard ratio, 0.27), reported Matthew J. Ellis, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and his associates.

“The low pCR rate for ACOSOG Z1031B patients who switched to neoadjuvant chemotherapy contradicts the hypothesis that AI-resistant proliferation in ER-rich tumors is associated with enhanced chemotherapy response,” they said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.4406).

Study subjects were postmenopausal women with stage II or III ER+ breast cancer who were randomly assigned to receive neoadjuvant AI therapy with anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole, then triaged to neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on Ki67 level. The efficacy of chemotherapy was lower than expected in this population, suggesting that optimal therapy for intrinsically AI-resistant disease – which will “likely depend on new insights into the molecular basis for primary endocrine therapy resistance”– should be further investigated, they wrote, noting that the triage approaches used in this study are being evaluated in the ongoing phase III ALTERNATE trial.

Dr. Ellis disclosed financial and other relationships with Bioclassifier, Novartis, Pfizer, Celgene, AstraZeneca, NanoString Technologies, and Prosigna.

Triage to chemotherapy using a Ki67-based Preoperative Endocrine Prognostic Index (PEPI), which also integrates residual disease burden, appears useful for deescalating adjuvant treatment after neoadjuvant aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy for breast cancer, investigators report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Only 4 of 109 patients (3.7%) in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1031B trial with a PEPI score of 0 relapsed after a median of 5.5 years (and were therefore unlikely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy), compared with 49 (14.4%) of 341 patients with a PEPI score greater than 0 (recurrence hazard ratio, 0.27), reported Matthew J. Ellis, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and his associates.

“The low pCR rate for ACOSOG Z1031B patients who switched to neoadjuvant chemotherapy contradicts the hypothesis that AI-resistant proliferation in ER-rich tumors is associated with enhanced chemotherapy response,” they said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.4406).

Study subjects were postmenopausal women with stage II or III ER+ breast cancer who were randomly assigned to receive neoadjuvant AI therapy with anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole, then triaged to neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on Ki67 level. The efficacy of chemotherapy was lower than expected in this population, suggesting that optimal therapy for intrinsically AI-resistant disease – which will “likely depend on new insights into the molecular basis for primary endocrine therapy resistance”– should be further investigated, they wrote, noting that the triage approaches used in this study are being evaluated in the ongoing phase III ALTERNATE trial.

Dr. Ellis disclosed financial and other relationships with Bioclassifier, Novartis, Pfizer, Celgene, AstraZeneca, NanoString Technologies, and Prosigna.

Triage to chemotherapy using a Ki67-based Preoperative Endocrine Prognostic Index (PEPI), which also integrates residual disease burden, appears useful for deescalating adjuvant treatment after neoadjuvant aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy for breast cancer, investigators report in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Only 4 of 109 patients (3.7%) in the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z1031B trial with a PEPI score of 0 relapsed after a median of 5.5 years (and were therefore unlikely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy), compared with 49 (14.4%) of 341 patients with a PEPI score greater than 0 (recurrence hazard ratio, 0.27), reported Matthew J. Ellis, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, and his associates.

“The low pCR rate for ACOSOG Z1031B patients who switched to neoadjuvant chemotherapy contradicts the hypothesis that AI-resistant proliferation in ER-rich tumors is associated with enhanced chemotherapy response,” they said (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jan 3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.4406).

Study subjects were postmenopausal women with stage II or III ER+ breast cancer who were randomly assigned to receive neoadjuvant AI therapy with anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole, then triaged to neoadjuvant chemotherapy based on Ki67 level. The efficacy of chemotherapy was lower than expected in this population, suggesting that optimal therapy for intrinsically AI-resistant disease – which will “likely depend on new insights into the molecular basis for primary endocrine therapy resistance”– should be further investigated, they wrote, noting that the triage approaches used in this study are being evaluated in the ongoing phase III ALTERNATE trial.

Dr. Ellis disclosed financial and other relationships with Bioclassifier, Novartis, Pfizer, Celgene, AstraZeneca, NanoString Technologies, and Prosigna.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Four of 109 patients (3.7%) with a PEPI score of 0 relapsed after a median of 5.5 years (and were therefore unlikely to benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy), compared with 49 (14.4%) of 341 patients with a PEPI score greater than 0 (recurrence HR, 0.27).

Data source: The randomized phase II ACOSOG Z1031B trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Ellis disclosed financial and other relationships with Bioclassifier, Novartis, Pfizer, Celgene, AstraZeneca, NanoString Technologies, and Prosigna.

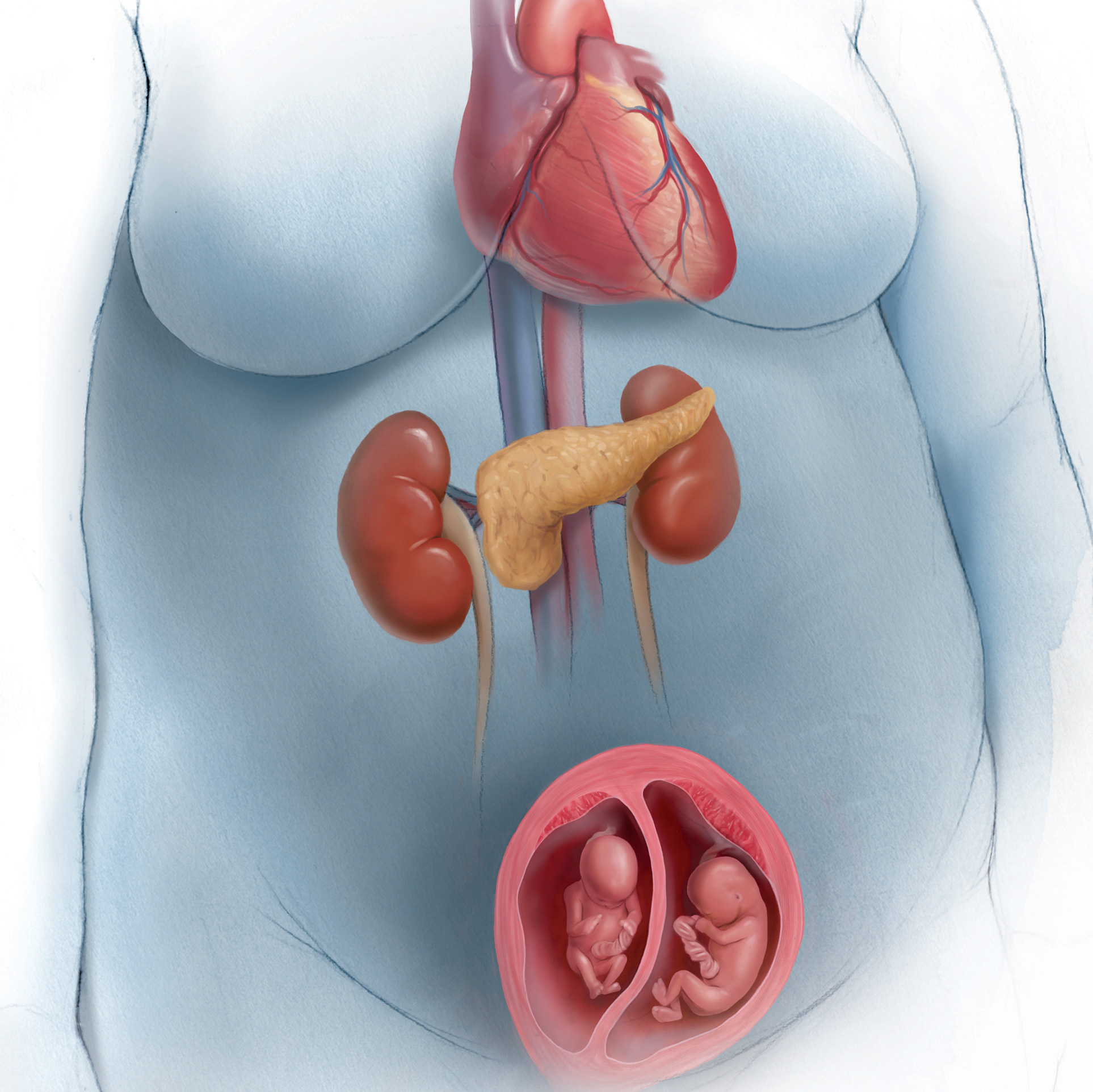

2017 Update on obstetrics

In this Update we discuss several exciting new recommendations for preventive treatments in pregnancy and prenatal diagnostic tests. Our A-to-Z coverage includes:

- antenatal steroids in late preterm pregnancy

- expanded list of high-risk conditions warranting low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

- chromosomal microarray analysis versus karyotype for specific clinical situations

- Zika virus infection evolving information.

Next: New recommendation for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

New recommendation offered for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al; for the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1311-1320.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 677. Antenatal corticosteroidtherapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e187-e194.

Kamath-Rayne BD, Rozance PJ, Goldenberg RL, Jobe AH. Antenatal corticosteroids beyond 34 weeks gestation: what do we do now? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):423-430.

A dramatic recommendation for obstetric practice change occurred in 2016: the option of administering antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturity after 34 weeks. In the Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial of betamethasone in the late preterm period in patients at "high risk" of imminent delivery, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues demonstrated that the treated group had a significant decrease in the rate of neonatal respiratory complications.

The primary outcome, a composite of respiratory morbidities (including transient tachypnea of the newborn, surfactant use, and need for resuscitation at birth) within the first 72 hours of life, had significant differences between groups, occurring in 165 of 1,427 infants (11.6%) in the betamethasone-treated group and 202 of 1,400 (14.4%) in the placebo group (relative risk in the betamethasone group, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.97; P = .02). However, there was no statistically significant difference in respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, or pneumonia between groups, and the significant difference noted in bronchopulmonary dysplasia was based on a total number of 11 cases.

In response to these findings, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) released practice advisories and interim updates, culminating in a final recommendation for a single course of betamethasone in patients at high risk of preterm delivery between 34 and 36 6/7 weeks who have not received a previous course.

Related article:

When could use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period be beneficial?

In a thorough review of the literature on antenatal steroid use, Kamath-Rayne and colleagues highlighted several factors that should be considered before adopting universal use of steroids at >34 weeks. These include:

- The definition of "high risk of imminent delivery" as preterm labor with at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement, or spontaneous rupture of membranes. The effect of less stringent inclusion criteria in real-world clinical practice is not known, and many patients who will go on to deliver at term will receive steroids unnecessarily.

- Multiple gestation, patients with pre-existing diabetes, women who had previously received a course of steroids, and fetuses with anomalies were excluded from the ALPS study. Use of antenatal steroids in these groups at >34 weeks should be evaluated before universal adoption.

Related article:

What is the ideal gestational age for twin delivery to minimize perinatal deaths?

- The incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the treated group was significantly increased. This affects our colleagues in pediatrics considerably from a systems standpoint (need for changes to newborn protocols and communication between services).

- The long-term outcomes of patients exposed to steroids in the late preterm period are yet to be delineated, specifically, the potential neurodevelopmental effects of a medication known to alter preterm brain development as well as cardiovascular and metabolic consequences.

Next: Low-dose aspirin for reducing preeclampsia risk

Low-dose aspirin clearly is effective for reducing the risk of preeclampsia

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122-1131.

Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):695-703.

LeFevre ML; US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):819-826.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

In the 2013 ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy report, low-dose aspirin (60-80 mg) was recommended to be initiated in the late first trimester to reduce preeclampsia risk for women with:

- prior early onset preeclampsia with preterm delivery at <34 weeks' gestation, or

- preeclampsia in more than one prior pregnancy.

This recommendation was based on several meta-analyses that demonstrated a 10% to 17% reduction in risk with no increase in bleeding, placental abruption, or other adverse events.

In 2014, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) conducted a systematic evidence review of low-dose aspirin use for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia. That report revealed a 24% risk reduction of preeclampsia in high-risk women treated with low-dose aspirin, as well as a 14% reduction in preterm birth and a 20% reduction in fetal growth restriction. A final statement from the USPSTF in 2014 recommended low-dose aspirin (60-150 mg) starting between 12 and 28 weeks' gestation for women at "high" risk who have:

- a history of preeclampsia, especially if accompanied by an adverse outcome

- multifetal gestation

- chronic hypertension

- diabetes (type 1 or type 2)

- renal disease

- autoimmune disease (such as systematic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome).

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

As of July 11, 2016, ACOG supports this expanded list of high-risk conditions. Additionally, the USPSTF identified a "moderate" risk group in which low-dose aspirin may be considered if a patient has several risk factors, such as obesity, nulliparity, family history of preeclampsia, age 35 years or older, or another poor pregnancy outcome. ACOG notes, however, that the evidence supporting this practice is uncertain and does not make a recommendation regarding aspirin use in this population. Further study should be conducted to determine the benefit of low-dose aspirin in these patients as well as the long-term effects of treatment on maternal and child outcomes.

Next: CMA for prenatal genetic diagnosis

Chromosomal microarray analysis is preferable to karyotype in certain situations

Pauli JM, Repke JT. Update on obstetrics. OBG Manag. 2013;25(1):28-32.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Dugoff L, Norton ME, Kuller JA. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):B2-B9.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 682. Microarrays and next- generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology.Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):e262-e268.

We previously addressed the use of chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) for prenatal diagnosis in our 2013 "Update on obstetrics," specifically, the question of whether CMA could replace karyotype. The main differences between karyotype and CMA are that 1) only karyotype can detect balanced translocations/inversions and 2) only CMA can detect copy number variants (CNV). There are some differences in the technology and capabilities of the 2 types of CMA currently available as well.

In our 2013 article we concluded that "The total costs of such an approach--test, interpretation, counseling, and long-term follow-up of uncertain results--are unknown at this time and may prove to be unaffordable on a population-wide basis." Today, the cost of CMA is still higher than karyotype, but it is expected to decrease and insurance coverage for this test is expected to increase.

Related article:

Cell-free DNA screening for women at low risk for fetal aneuploidy

Both SMFM and ACOG released recommendations in 2016 regarding the use of CMA in prenatal genetic diagnosis, summarized as follows:

- CMA is recommended over karyotype for fetuses with structural abnormalities on ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant abnormal CNVs in this population is about 6%

- CMA is recommended for diagnosis for stillbirth specimens

- CMA does not require dividing cells and may be a quicker and more reliable test in this population

- Karotype or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is recommended for fetuses with ultrasound findings suggestive of aneuploidy

- If it is negative, then CMA is recommended

- Karyotype or CMA is recommended for patients desiring prenatal diagnostic testing with a normal fetal ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant CNVs in this population (advanced maternal age, abnormal serum screening, prior aneuploidy, parental anxiety) is about 1%

- Pretest and posttest counseling about the limitations of CMA and a 2% risk of detection of variants of unknown significance (VUS) should be performed by a provider who has expertise in CMA and who has access to databases with genotype/phenotype information for VUS

- This counseling should also include the possibility of diagnosis of nonpaternity, consanguinity, and adult-onset disease

- Karyotype is recommended for couples with recurrent pregnancy loss

- The identification of balanced translocations in this population is most relevant in this patient population

- Prenatal diagnosis with routine use of whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing is not recommended.

Next: Zika virus: Check for updates

Zika virus infection: Check often for the latest updates

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Practice advisory on Zika virus. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Interim-Guidance-for-Care-of-Obstetric-Patients- During-a-Zika-Virus-Outbreak. Published December 5, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pregnancy/index.html. Updated August 22, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.

A yearly update on obstetrics would be remiss without mention of the Zika virus and its impact on pregnancy and reproduction. That being said, any recommendations we offer may be out of date by the time this article is published given the rapidly changing picture of Zika virus since it first dominated the headlines in 2016. Here are the basics as summarized from ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

Viral spread. Zika virus may be spread in several ways: by an infected Aedes species mosquito, mother to fetus, sexual contact, blood transfusion, or laboratory exposure.

Symptoms of infection include conjunctivitis, fever, rash, and arthralgia, but most patients (4/5) are asymptomatic.

Sequelae. Zika virus infection during pregnancy is believed to cause fetal and neonatal microcephaly, intracranial calcifications, and brain and eye abnormalities. The rate of these findings in infected individuals, as well as the rate of vertical transmission, is not known.

Travel advisory. Pregnant women should not travel to areas with active Zika infection (the CDC website regularly updates these restricted areas).

Preventive measures. If traveling to an area of active Zika infection, pregnant women should take preventative measures day and night against mosquito bites, such as use of insect repellents approved by the Environmental Protection Agency, clothing that covers exposed skin, and staying indoors.

Safe sex. Abstinence or consistent condom use is recommended for pregnant women with partners who travel to or live in areas of active Zika infection.

Delay conception. Conception should be postponed for at least 6 months in men with Zika infection and at least 8 weeks in women with Zika infection.

Testing recommendations. Pregnant women with Zika virus exposure should be tested, regardless of symptoms. Symptomatic exposed nonpregnant women and all men should be tested.

Prenatal surveillance. High-risk consultation and serial ultrasounds for fetal anatomy and growth should be considered in patients with Zika virus infection during pregnancy. Amniocentesis can be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Related article:

Zika virus update: A rapidly moving target

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

In this Update we discuss several exciting new recommendations for preventive treatments in pregnancy and prenatal diagnostic tests. Our A-to-Z coverage includes:

- antenatal steroids in late preterm pregnancy

- expanded list of high-risk conditions warranting low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prevention

- chromosomal microarray analysis versus karyotype for specific clinical situations

- Zika virus infection evolving information.

Next: New recommendation for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

New recommendation offered for timing of late preterm antenatal steroids

Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC, et al; for the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Antenatal betamethasone for women at risk for late preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1311-1320.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 677. Antenatal corticosteroidtherapy for fetal maturation. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(4):e187-e194.

Kamath-Rayne BD, Rozance PJ, Goldenberg RL, Jobe AH. Antenatal corticosteroids beyond 34 weeks gestation: what do we do now? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):423-430.

A dramatic recommendation for obstetric practice change occurred in 2016: the option of administering antenatal steroids for fetal lung maturity after 34 weeks. In the Antenatal Late Preterm Steroids (ALPS) trial of betamethasone in the late preterm period in patients at "high risk" of imminent delivery, Gyamfi-Bannerman and colleagues demonstrated that the treated group had a significant decrease in the rate of neonatal respiratory complications.

The primary outcome, a composite of respiratory morbidities (including transient tachypnea of the newborn, surfactant use, and need for resuscitation at birth) within the first 72 hours of life, had significant differences between groups, occurring in 165 of 1,427 infants (11.6%) in the betamethasone-treated group and 202 of 1,400 (14.4%) in the placebo group (relative risk in the betamethasone group, 0.80; 95% confidence interval, 0.66-0.97; P = .02). However, there was no statistically significant difference in respiratory distress syndrome, apnea, or pneumonia between groups, and the significant difference noted in bronchopulmonary dysplasia was based on a total number of 11 cases.

In response to these findings, both the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) released practice advisories and interim updates, culminating in a final recommendation for a single course of betamethasone in patients at high risk of preterm delivery between 34 and 36 6/7 weeks who have not received a previous course.

Related article:

When could use of antenatal corticosteroids in the late preterm birth period be beneficial?

In a thorough review of the literature on antenatal steroid use, Kamath-Rayne and colleagues highlighted several factors that should be considered before adopting universal use of steroids at >34 weeks. These include:

- The definition of "high risk of imminent delivery" as preterm labor with at least 3-cm dilation or 75% effacement, or spontaneous rupture of membranes. The effect of less stringent inclusion criteria in real-world clinical practice is not known, and many patients who will go on to deliver at term will receive steroids unnecessarily.

- Multiple gestation, patients with pre-existing diabetes, women who had previously received a course of steroids, and fetuses with anomalies were excluded from the ALPS study. Use of antenatal steroids in these groups at >34 weeks should be evaluated before universal adoption.

Related article:

What is the ideal gestational age for twin delivery to minimize perinatal deaths?

- The incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in the treated group was significantly increased. This affects our colleagues in pediatrics considerably from a systems standpoint (need for changes to newborn protocols and communication between services).

- The long-term outcomes of patients exposed to steroids in the late preterm period are yet to be delineated, specifically, the potential neurodevelopmental effects of a medication known to alter preterm brain development as well as cardiovascular and metabolic consequences.

Next: Low-dose aspirin for reducing preeclampsia risk

Low-dose aspirin clearly is effective for reducing the risk of preeclampsia

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122-1131.

Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O'Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):695-703.

LeFevre ML; US Preventive Services Task Force. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):819-826.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice advisory on low-dose aspirin and prevention of preeclampsia: updated recommendations. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Low-Dose-Aspirin-and-Prevention-of-Preeclampsia-Updated-Recommendations. Published July 11, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

In the 2013 ACOG Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy report, low-dose aspirin (60-80 mg) was recommended to be initiated in the late first trimester to reduce preeclampsia risk for women with:

- prior early onset preeclampsia with preterm delivery at <34 weeks' gestation, or

- preeclampsia in more than one prior pregnancy.

This recommendation was based on several meta-analyses that demonstrated a 10% to 17% reduction in risk with no increase in bleeding, placental abruption, or other adverse events.

In 2014, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) conducted a systematic evidence review of low-dose aspirin use for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia. That report revealed a 24% risk reduction of preeclampsia in high-risk women treated with low-dose aspirin, as well as a 14% reduction in preterm birth and a 20% reduction in fetal growth restriction. A final statement from the USPSTF in 2014 recommended low-dose aspirin (60-150 mg) starting between 12 and 28 weeks' gestation for women at "high" risk who have:

- a history of preeclampsia, especially if accompanied by an adverse outcome

- multifetal gestation

- chronic hypertension

- diabetes (type 1 or type 2)

- renal disease

- autoimmune disease (such as systematic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome).

Related article:

Start offering aspirin to pregnant women at high risk for preeclampsia

As of July 11, 2016, ACOG supports this expanded list of high-risk conditions. Additionally, the USPSTF identified a "moderate" risk group in which low-dose aspirin may be considered if a patient has several risk factors, such as obesity, nulliparity, family history of preeclampsia, age 35 years or older, or another poor pregnancy outcome. ACOG notes, however, that the evidence supporting this practice is uncertain and does not make a recommendation regarding aspirin use in this population. Further study should be conducted to determine the benefit of low-dose aspirin in these patients as well as the long-term effects of treatment on maternal and child outcomes.

Next: CMA for prenatal genetic diagnosis

Chromosomal microarray analysis is preferable to karyotype in certain situations

Pauli JM, Repke JT. Update on obstetrics. OBG Manag. 2013;25(1):28-32.

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), Dugoff L, Norton ME, Kuller JA. The use of chromosomal microarray for prenatal diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(4):B2-B9.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 682. Microarrays and next- generation sequencing technology: the use of advanced genetic diagnostic tools in obstetrics and gynecology.Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(6):e262-e268.

We previously addressed the use of chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) for prenatal diagnosis in our 2013 "Update on obstetrics," specifically, the question of whether CMA could replace karyotype. The main differences between karyotype and CMA are that 1) only karyotype can detect balanced translocations/inversions and 2) only CMA can detect copy number variants (CNV). There are some differences in the technology and capabilities of the 2 types of CMA currently available as well.

In our 2013 article we concluded that "The total costs of such an approach--test, interpretation, counseling, and long-term follow-up of uncertain results--are unknown at this time and may prove to be unaffordable on a population-wide basis." Today, the cost of CMA is still higher than karyotype, but it is expected to decrease and insurance coverage for this test is expected to increase.

Related article:

Cell-free DNA screening for women at low risk for fetal aneuploidy

Both SMFM and ACOG released recommendations in 2016 regarding the use of CMA in prenatal genetic diagnosis, summarized as follows:

- CMA is recommended over karyotype for fetuses with structural abnormalities on ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant abnormal CNVs in this population is about 6%

- CMA is recommended for diagnosis for stillbirth specimens

- CMA does not require dividing cells and may be a quicker and more reliable test in this population

- Karotype or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is recommended for fetuses with ultrasound findings suggestive of aneuploidy

- If it is negative, then CMA is recommended

- Karyotype or CMA is recommended for patients desiring prenatal diagnostic testing with a normal fetal ultrasound

- The detection rate for clinically relevant CNVs in this population (advanced maternal age, abnormal serum screening, prior aneuploidy, parental anxiety) is about 1%

- Pretest and posttest counseling about the limitations of CMA and a 2% risk of detection of variants of unknown significance (VUS) should be performed by a provider who has expertise in CMA and who has access to databases with genotype/phenotype information for VUS

- This counseling should also include the possibility of diagnosis of nonpaternity, consanguinity, and adult-onset disease

- Karyotype is recommended for couples with recurrent pregnancy loss

- The identification of balanced translocations in this population is most relevant in this patient population

- Prenatal diagnosis with routine use of whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing is not recommended.

Next: Zika virus: Check for updates

Zika virus infection: Check often for the latest updates

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Practice advisory on Zika virus. http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/News-Room/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Interim-Guidance-for-Care-of-Obstetric-Patients- During-a-Zika-Virus-Outbreak. Published December 5, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika virus. http://www.cdc.gov/zika/pregnancy/index.html. Updated August 22, 2016. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Petersen EE, Meaney-Delman D, Neblett-Fanfair R, et al. Update: interim guidance for preconception counseling and prevention of sexual transmission of Zika virus for persons with possible Zika virus exposure--United States, September 2016. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(39):1077-1081.