User login

Drug eases existential anxiety in cancer patients

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

One-time treatment with the hallucinogenic drug psilocybin may provide long-term relief of existential anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancers, according to a small study.

After receiving a single high dose of the drug, most of the patients studied reported decreases in depression and anxiety as well as increases in quality of life and optimism.

These improvements were sustained at 6 months of follow-up.

“The most interesting and remarkable finding is that a single dose of psilocybin, which lasts 4 to 6 hours, produced enduring decreases in depression and anxiety symptoms, and this may represent a fascinating new model for treating some psychiatric conditions,” said study author Roland Griffiths, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Griffiths said this study grew out of a decade of research at Johns Hopkins on the effects of psilocybin in healthy volunteers, which showed that psilocybin can consistently produce positive changes in mood, behavior, and spirituality when administered to carefully screened and prepared participants.

The current study was designed to see if psilocybin could produce similar results in psychologically distressed cancer patients.

The results were published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology alongside a similar study and 11 accompanying editorials.

For their study, Dr Griffiths and his colleagues recruited 51 participants diagnosed with life-threatening cancers, most of which were recurrent or metastatic.

Types of cancer included breast (n=13), upper aerodigestive (n=7), gastrointestinal (n=4), genitourinary (n=18), and “other” cancers (n=1), as well as hematologic malignancies (n=8).

All participants had been given a formal psychiatric diagnosis, including an anxiety or depressive disorder.

Half of the participants were female, and they had an average age of 56. Ninety-two percent were white, 4% were black, and 2% were Asian.

Treatment

Each participant had 2 treatment sessions scheduled 5 weeks apart. In 1 session, they received a capsule containing a very low dose (1 or 3 mg per 70 kg) of psilocybin that was meant to act as a “control” because the dose was too low to produce effects.

In the other session, participants received a capsule with what is considered a moderate or high dose (22 or 30 mg per 70 kg).

To minimize expectancy effects, the participants and the staff members supervising the sessions were told that participants would receive psilocybin on both sessions, but they did not know that all participants would receive a high dose and a low dose.

Blood pressure and mood were monitored throughout the sessions.

Two monitors aided participants during each session, encouraging them to lie down, wear an eye mask, listen to music through headphones, and direct their attention on their inner experience. If anxiety or confusion arose, the monitors provided reassurance to the participants.

Participants, staff, and community observers rated participants’ moods, attitudes, and behaviors throughout the study.

The researchers assessed each participant via questionnaires and structured interviews before the first session, 7 hours after taking the psilocybin, 5 weeks after each session, and 6 months after the second session.

Adverse events

Thirty-four percent of participants had an episode of elevated systolic blood pressure (>160 mm Hg at 1 or more time-point) in the high-dose psilocybin session, and 17% of participants had such an episode in the low-dose session.

Thirteen percent and 2%, respectively, had an episode of elevated diastolic blood pressure (>100 mm Hg at 1 or more time-point). None of these episodes met criteria for medical intervention.

During the high-dose psilocybin session, 15% of patients experienced nausea or vomiting. There were no such events during the low-dose session.

Three participants reported mild to moderate headaches after the high-dose session.

Twenty-one percent of patients reported physical discomfort during the high-dose session, as did 8% of patients during the low-dose session.

Psychological discomfort occurred in 32% and 12% of participants, respectively. The researchers said there were no cases of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder or prolonged psychosis.

Efficacy outcomes

Most participants reported experiencing changes in visual perception, emotions, and thinking after taking high-dose psilocybin. They also reported experiences of psychological insight and profound, deeply meaningful experiences.

Six months after the final session of treatment, about 80% of participants continued to show clinically significant decreases in depressed mood and anxiety, according to clinician assessment.

According to the participants themselves, 83% had increases in well-being or life satisfaction at 6 months after treatment.

Sixty-seven percent of participants rated the experience as one of the top 5 meaningful experiences in their lives, and 70% rated the experience as one of their top 5 spiritually significant lifetime events.

“Before beginning the study, it wasn’t clear to me that this treatment would be helpful, since cancer patients may experience profound hopelessness in response to their diagnosis, which is often followed by multiple surgeries and prolonged chemotherapy,” Dr Griffiths said.

“I could imagine that cancer patients would receive psilocybin, look into the existential void, and come out even more fearful. However, the positive changes in attitudes, moods, and behavior that we documented in healthy volunteers were replicated in cancer patients.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

One-time treatment with the hallucinogenic drug psilocybin may provide long-term relief of existential anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancers, according to a small study.

After receiving a single high dose of the drug, most of the patients studied reported decreases in depression and anxiety as well as increases in quality of life and optimism.

These improvements were sustained at 6 months of follow-up.

“The most interesting and remarkable finding is that a single dose of psilocybin, which lasts 4 to 6 hours, produced enduring decreases in depression and anxiety symptoms, and this may represent a fascinating new model for treating some psychiatric conditions,” said study author Roland Griffiths, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Griffiths said this study grew out of a decade of research at Johns Hopkins on the effects of psilocybin in healthy volunteers, which showed that psilocybin can consistently produce positive changes in mood, behavior, and spirituality when administered to carefully screened and prepared participants.

The current study was designed to see if psilocybin could produce similar results in psychologically distressed cancer patients.

The results were published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology alongside a similar study and 11 accompanying editorials.

For their study, Dr Griffiths and his colleagues recruited 51 participants diagnosed with life-threatening cancers, most of which were recurrent or metastatic.

Types of cancer included breast (n=13), upper aerodigestive (n=7), gastrointestinal (n=4), genitourinary (n=18), and “other” cancers (n=1), as well as hematologic malignancies (n=8).

All participants had been given a formal psychiatric diagnosis, including an anxiety or depressive disorder.

Half of the participants were female, and they had an average age of 56. Ninety-two percent were white, 4% were black, and 2% were Asian.

Treatment

Each participant had 2 treatment sessions scheduled 5 weeks apart. In 1 session, they received a capsule containing a very low dose (1 or 3 mg per 70 kg) of psilocybin that was meant to act as a “control” because the dose was too low to produce effects.

In the other session, participants received a capsule with what is considered a moderate or high dose (22 or 30 mg per 70 kg).

To minimize expectancy effects, the participants and the staff members supervising the sessions were told that participants would receive psilocybin on both sessions, but they did not know that all participants would receive a high dose and a low dose.

Blood pressure and mood were monitored throughout the sessions.

Two monitors aided participants during each session, encouraging them to lie down, wear an eye mask, listen to music through headphones, and direct their attention on their inner experience. If anxiety or confusion arose, the monitors provided reassurance to the participants.

Participants, staff, and community observers rated participants’ moods, attitudes, and behaviors throughout the study.

The researchers assessed each participant via questionnaires and structured interviews before the first session, 7 hours after taking the psilocybin, 5 weeks after each session, and 6 months after the second session.

Adverse events

Thirty-four percent of participants had an episode of elevated systolic blood pressure (>160 mm Hg at 1 or more time-point) in the high-dose psilocybin session, and 17% of participants had such an episode in the low-dose session.

Thirteen percent and 2%, respectively, had an episode of elevated diastolic blood pressure (>100 mm Hg at 1 or more time-point). None of these episodes met criteria for medical intervention.

During the high-dose psilocybin session, 15% of patients experienced nausea or vomiting. There were no such events during the low-dose session.

Three participants reported mild to moderate headaches after the high-dose session.

Twenty-one percent of patients reported physical discomfort during the high-dose session, as did 8% of patients during the low-dose session.

Psychological discomfort occurred in 32% and 12% of participants, respectively. The researchers said there were no cases of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder or prolonged psychosis.

Efficacy outcomes

Most participants reported experiencing changes in visual perception, emotions, and thinking after taking high-dose psilocybin. They also reported experiences of psychological insight and profound, deeply meaningful experiences.

Six months after the final session of treatment, about 80% of participants continued to show clinically significant decreases in depressed mood and anxiety, according to clinician assessment.

According to the participants themselves, 83% had increases in well-being or life satisfaction at 6 months after treatment.

Sixty-seven percent of participants rated the experience as one of the top 5 meaningful experiences in their lives, and 70% rated the experience as one of their top 5 spiritually significant lifetime events.

“Before beginning the study, it wasn’t clear to me that this treatment would be helpful, since cancer patients may experience profound hopelessness in response to their diagnosis, which is often followed by multiple surgeries and prolonged chemotherapy,” Dr Griffiths said.

“I could imagine that cancer patients would receive psilocybin, look into the existential void, and come out even more fearful. However, the positive changes in attitudes, moods, and behavior that we documented in healthy volunteers were replicated in cancer patients.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

One-time treatment with the hallucinogenic drug psilocybin may provide long-term relief of existential anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancers, according to a small study.

After receiving a single high dose of the drug, most of the patients studied reported decreases in depression and anxiety as well as increases in quality of life and optimism.

These improvements were sustained at 6 months of follow-up.

“The most interesting and remarkable finding is that a single dose of psilocybin, which lasts 4 to 6 hours, produced enduring decreases in depression and anxiety symptoms, and this may represent a fascinating new model for treating some psychiatric conditions,” said study author Roland Griffiths, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Griffiths said this study grew out of a decade of research at Johns Hopkins on the effects of psilocybin in healthy volunteers, which showed that psilocybin can consistently produce positive changes in mood, behavior, and spirituality when administered to carefully screened and prepared participants.

The current study was designed to see if psilocybin could produce similar results in psychologically distressed cancer patients.

The results were published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology alongside a similar study and 11 accompanying editorials.

For their study, Dr Griffiths and his colleagues recruited 51 participants diagnosed with life-threatening cancers, most of which were recurrent or metastatic.

Types of cancer included breast (n=13), upper aerodigestive (n=7), gastrointestinal (n=4), genitourinary (n=18), and “other” cancers (n=1), as well as hematologic malignancies (n=8).

All participants had been given a formal psychiatric diagnosis, including an anxiety or depressive disorder.

Half of the participants were female, and they had an average age of 56. Ninety-two percent were white, 4% were black, and 2% were Asian.

Treatment

Each participant had 2 treatment sessions scheduled 5 weeks apart. In 1 session, they received a capsule containing a very low dose (1 or 3 mg per 70 kg) of psilocybin that was meant to act as a “control” because the dose was too low to produce effects.

In the other session, participants received a capsule with what is considered a moderate or high dose (22 or 30 mg per 70 kg).

To minimize expectancy effects, the participants and the staff members supervising the sessions were told that participants would receive psilocybin on both sessions, but they did not know that all participants would receive a high dose and a low dose.

Blood pressure and mood were monitored throughout the sessions.

Two monitors aided participants during each session, encouraging them to lie down, wear an eye mask, listen to music through headphones, and direct their attention on their inner experience. If anxiety or confusion arose, the monitors provided reassurance to the participants.

Participants, staff, and community observers rated participants’ moods, attitudes, and behaviors throughout the study.

The researchers assessed each participant via questionnaires and structured interviews before the first session, 7 hours after taking the psilocybin, 5 weeks after each session, and 6 months after the second session.

Adverse events

Thirty-four percent of participants had an episode of elevated systolic blood pressure (>160 mm Hg at 1 or more time-point) in the high-dose psilocybin session, and 17% of participants had such an episode in the low-dose session.

Thirteen percent and 2%, respectively, had an episode of elevated diastolic blood pressure (>100 mm Hg at 1 or more time-point). None of these episodes met criteria for medical intervention.

During the high-dose psilocybin session, 15% of patients experienced nausea or vomiting. There were no such events during the low-dose session.

Three participants reported mild to moderate headaches after the high-dose session.

Twenty-one percent of patients reported physical discomfort during the high-dose session, as did 8% of patients during the low-dose session.

Psychological discomfort occurred in 32% and 12% of participants, respectively. The researchers said there were no cases of hallucinogen persisting perception disorder or prolonged psychosis.

Efficacy outcomes

Most participants reported experiencing changes in visual perception, emotions, and thinking after taking high-dose psilocybin. They also reported experiences of psychological insight and profound, deeply meaningful experiences.

Six months after the final session of treatment, about 80% of participants continued to show clinically significant decreases in depressed mood and anxiety, according to clinician assessment.

According to the participants themselves, 83% had increases in well-being or life satisfaction at 6 months after treatment.

Sixty-seven percent of participants rated the experience as one of the top 5 meaningful experiences in their lives, and 70% rated the experience as one of their top 5 spiritually significant lifetime events.

“Before beginning the study, it wasn’t clear to me that this treatment would be helpful, since cancer patients may experience profound hopelessness in response to their diagnosis, which is often followed by multiple surgeries and prolonged chemotherapy,” Dr Griffiths said.

“I could imagine that cancer patients would receive psilocybin, look into the existential void, and come out even more fearful. However, the positive changes in attitudes, moods, and behavior that we documented in healthy volunteers were replicated in cancer patients.” ![]()

Study reveals potential therapeutic targets for MDS

Preclinical research has revealed potential therapeutic targets for

myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Investigators

found evidence to suggest that TRAF6, a toll-like receptor effector

with ubiquitin ligase activity, plays a key role in MDS.

So TRAF6 and

proteins regulated by TRAF6 may be therapeutic targets for MDS.

Daniel Starczynowski, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Immunology.

The investigators first found that TRAF6 is overexpressed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells from MDS patients.

To more closely examine the role of TRAF6 in MDS, the team created mouse models in which the protein was overexpressed.

“We found that TRAF6 overexpression in mouse hematopoietic stem cells results in impaired blood cell formation and bone marrow failure,” Dr Starczynowski said.

Further investigation revealed that hnRNPA1, an RNA-binding protein and auxiliary splicing factor, is a substrate of TRAF6. And TRAF6 ubiquitination of hnRNPA1 regulates alternative splicing of Arhgap1.

This activates the GTP-binding Rho family protein Cdc42 and accounts for the defects observed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells that express TRAF6.

All of these proteins could be potential treatment targets for cases of MDS triggered by overexpression of TRAF6, according to Dr Starczynowski, who said future studies will test their therapeutic potential in mouse models of MDS.

“Based on our paper, a number of therapeutic approaches can be tested and directed against TRAF6 and other related proteins responsible for MDS,” he said.

Beyond the potential for new therapeutic approaches in MDS, this research revealed a new and critical immune-related function for TRAF6, according to the investigators.

TRAF6 regulates RNA isoform expression in response to various pathogens. In the context of the current study, TRAF6’s regulation of RNA isoform expression is important to the function of hematopoietic cells and reveals another dimension to how cells respond to infection, Dr Starczynowski said. ![]()

Preclinical research has revealed potential therapeutic targets for

myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Investigators

found evidence to suggest that TRAF6, a toll-like receptor effector

with ubiquitin ligase activity, plays a key role in MDS.

So TRAF6 and

proteins regulated by TRAF6 may be therapeutic targets for MDS.

Daniel Starczynowski, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Immunology.

The investigators first found that TRAF6 is overexpressed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells from MDS patients.

To more closely examine the role of TRAF6 in MDS, the team created mouse models in which the protein was overexpressed.

“We found that TRAF6 overexpression in mouse hematopoietic stem cells results in impaired blood cell formation and bone marrow failure,” Dr Starczynowski said.

Further investigation revealed that hnRNPA1, an RNA-binding protein and auxiliary splicing factor, is a substrate of TRAF6. And TRAF6 ubiquitination of hnRNPA1 regulates alternative splicing of Arhgap1.

This activates the GTP-binding Rho family protein Cdc42 and accounts for the defects observed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells that express TRAF6.

All of these proteins could be potential treatment targets for cases of MDS triggered by overexpression of TRAF6, according to Dr Starczynowski, who said future studies will test their therapeutic potential in mouse models of MDS.

“Based on our paper, a number of therapeutic approaches can be tested and directed against TRAF6 and other related proteins responsible for MDS,” he said.

Beyond the potential for new therapeutic approaches in MDS, this research revealed a new and critical immune-related function for TRAF6, according to the investigators.

TRAF6 regulates RNA isoform expression in response to various pathogens. In the context of the current study, TRAF6’s regulation of RNA isoform expression is important to the function of hematopoietic cells and reveals another dimension to how cells respond to infection, Dr Starczynowski said. ![]()

Preclinical research has revealed potential therapeutic targets for

myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

Investigators

found evidence to suggest that TRAF6, a toll-like receptor effector

with ubiquitin ligase activity, plays a key role in MDS.

So TRAF6 and

proteins regulated by TRAF6 may be therapeutic targets for MDS.

Daniel Starczynowski, PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature Immunology.

The investigators first found that TRAF6 is overexpressed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells from MDS patients.

To more closely examine the role of TRAF6 in MDS, the team created mouse models in which the protein was overexpressed.

“We found that TRAF6 overexpression in mouse hematopoietic stem cells results in impaired blood cell formation and bone marrow failure,” Dr Starczynowski said.

Further investigation revealed that hnRNPA1, an RNA-binding protein and auxiliary splicing factor, is a substrate of TRAF6. And TRAF6 ubiquitination of hnRNPA1 regulates alternative splicing of Arhgap1.

This activates the GTP-binding Rho family protein Cdc42 and accounts for the defects observed in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells that express TRAF6.

All of these proteins could be potential treatment targets for cases of MDS triggered by overexpression of TRAF6, according to Dr Starczynowski, who said future studies will test their therapeutic potential in mouse models of MDS.

“Based on our paper, a number of therapeutic approaches can be tested and directed against TRAF6 and other related proteins responsible for MDS,” he said.

Beyond the potential for new therapeutic approaches in MDS, this research revealed a new and critical immune-related function for TRAF6, according to the investigators.

TRAF6 regulates RNA isoform expression in response to various pathogens. In the context of the current study, TRAF6’s regulation of RNA isoform expression is important to the function of hematopoietic cells and reveals another dimension to how cells respond to infection, Dr Starczynowski said. ![]()

Robot-assisted laparoscopic resection of a noncommunicating cavitary rudimentary horn

A unicornuate uterus with a noncommunicating rudimentary horn is a rare mullerian duct anomaly (MDA). It often goes undiagnosed due to the absence of functional endometrium in the anomalous horn. However, when the rudimentary horn is lined with endometrium, obstructed menstrual flow can lead to severe cyclic pelvic pain, development of a pelvic mass, and endometriosis from retrograde menstruation. For these reasons, surgical resection is recommended for patients with this anomaly.

In this video the surgical patient is a 15-year-old adolescent with a 1-year history of progressive dysmenorrhea. Imaging studies revealed a noncommunicating cavitary right uterine horn and confirmed a normal urinary tract system.

We present a stepwise demonstration of our technique for surgical resection of a noncommunicating cavitary uterine horn and conclude that robotic surgery is a safe and feasible route for surgical management of this pathology.

I am pleased to bring you this video to kick off the New Year. We are delighted that our work won "Best Video on Robotic Technology" at the annual AAGL meeting in November 2016, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A unicornuate uterus with a noncommunicating rudimentary horn is a rare mullerian duct anomaly (MDA). It often goes undiagnosed due to the absence of functional endometrium in the anomalous horn. However, when the rudimentary horn is lined with endometrium, obstructed menstrual flow can lead to severe cyclic pelvic pain, development of a pelvic mass, and endometriosis from retrograde menstruation. For these reasons, surgical resection is recommended for patients with this anomaly.

In this video the surgical patient is a 15-year-old adolescent with a 1-year history of progressive dysmenorrhea. Imaging studies revealed a noncommunicating cavitary right uterine horn and confirmed a normal urinary tract system.

We present a stepwise demonstration of our technique for surgical resection of a noncommunicating cavitary uterine horn and conclude that robotic surgery is a safe and feasible route for surgical management of this pathology.

I am pleased to bring you this video to kick off the New Year. We are delighted that our work won "Best Video on Robotic Technology" at the annual AAGL meeting in November 2016, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A unicornuate uterus with a noncommunicating rudimentary horn is a rare mullerian duct anomaly (MDA). It often goes undiagnosed due to the absence of functional endometrium in the anomalous horn. However, when the rudimentary horn is lined with endometrium, obstructed menstrual flow can lead to severe cyclic pelvic pain, development of a pelvic mass, and endometriosis from retrograde menstruation. For these reasons, surgical resection is recommended for patients with this anomaly.

In this video the surgical patient is a 15-year-old adolescent with a 1-year history of progressive dysmenorrhea. Imaging studies revealed a noncommunicating cavitary right uterine horn and confirmed a normal urinary tract system.

We present a stepwise demonstration of our technique for surgical resection of a noncommunicating cavitary uterine horn and conclude that robotic surgery is a safe and feasible route for surgical management of this pathology.

I am pleased to bring you this video to kick off the New Year. We are delighted that our work won "Best Video on Robotic Technology" at the annual AAGL meeting in November 2016, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Epilepsy Raises Risks for Veterans

Iraq and Afghanistan veterans (IAV) with epilepsy have more than twice the risk of dying than do those without epilepsy, according to VA researchers.

In the study of 320,583 veterans, 2,187 met the epilepsy criteria. About 5 times more veterans with epilepsy had died by the end of follow-up compared with those without epilepsy. Veterans with epilepsy also are more likely to have mental and physical comorbidities, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, traumatic brain injury, substance use disorder, and hypertension.

Related: Providing Quality Epilepsy Care for Veterans

Before their study, which is the first examining mortality in IAV with epilepsy, the researchers say little information existed about comorbidities and mortality. Epilepsy in veterans usually develops during or after service. People with epilepsy usually are excluded from military service (DoD standards require a 5-year period without seizures or treatment for seizures prior to enlistment). The age-adjusted prevalence of seizure disorder in IAV is 6.1 per 1,000 compared with 7.1 to 10 per 1,000 in the general population.

In response to the higher risk of epilepsy in IAV with traumatic brain injury, the VA established the Epilepsy Centers of Excellence, the researchers note, to increase access to comprehensive multidisciplinary epilepsy specialty care. However, the significantly higher prevalence of comorbidities in this population suggests that “closer integration of primary care, epilepsy specialty care, and mental health care might be needed to reduce excess mortality.”

Related: VA to Reexamine 24,000 Veterans for TBI

The researchers suggest that public health agencies, including the VA, implement evidence-based, chronic disease self-management programs and supports that target physical and psychiatric comorbidity, study long-term outcomes, and ensure links to appropriate clinical and community health care facilities and social service providers.

Iraq and Afghanistan veterans (IAV) with epilepsy have more than twice the risk of dying than do those without epilepsy, according to VA researchers.

In the study of 320,583 veterans, 2,187 met the epilepsy criteria. About 5 times more veterans with epilepsy had died by the end of follow-up compared with those without epilepsy. Veterans with epilepsy also are more likely to have mental and physical comorbidities, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, traumatic brain injury, substance use disorder, and hypertension.

Related: Providing Quality Epilepsy Care for Veterans

Before their study, which is the first examining mortality in IAV with epilepsy, the researchers say little information existed about comorbidities and mortality. Epilepsy in veterans usually develops during or after service. People with epilepsy usually are excluded from military service (DoD standards require a 5-year period without seizures or treatment for seizures prior to enlistment). The age-adjusted prevalence of seizure disorder in IAV is 6.1 per 1,000 compared with 7.1 to 10 per 1,000 in the general population.

In response to the higher risk of epilepsy in IAV with traumatic brain injury, the VA established the Epilepsy Centers of Excellence, the researchers note, to increase access to comprehensive multidisciplinary epilepsy specialty care. However, the significantly higher prevalence of comorbidities in this population suggests that “closer integration of primary care, epilepsy specialty care, and mental health care might be needed to reduce excess mortality.”

Related: VA to Reexamine 24,000 Veterans for TBI

The researchers suggest that public health agencies, including the VA, implement evidence-based, chronic disease self-management programs and supports that target physical and psychiatric comorbidity, study long-term outcomes, and ensure links to appropriate clinical and community health care facilities and social service providers.

Iraq and Afghanistan veterans (IAV) with epilepsy have more than twice the risk of dying than do those without epilepsy, according to VA researchers.

In the study of 320,583 veterans, 2,187 met the epilepsy criteria. About 5 times more veterans with epilepsy had died by the end of follow-up compared with those without epilepsy. Veterans with epilepsy also are more likely to have mental and physical comorbidities, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, traumatic brain injury, substance use disorder, and hypertension.

Related: Providing Quality Epilepsy Care for Veterans

Before their study, which is the first examining mortality in IAV with epilepsy, the researchers say little information existed about comorbidities and mortality. Epilepsy in veterans usually develops during or after service. People with epilepsy usually are excluded from military service (DoD standards require a 5-year period without seizures or treatment for seizures prior to enlistment). The age-adjusted prevalence of seizure disorder in IAV is 6.1 per 1,000 compared with 7.1 to 10 per 1,000 in the general population.

In response to the higher risk of epilepsy in IAV with traumatic brain injury, the VA established the Epilepsy Centers of Excellence, the researchers note, to increase access to comprehensive multidisciplinary epilepsy specialty care. However, the significantly higher prevalence of comorbidities in this population suggests that “closer integration of primary care, epilepsy specialty care, and mental health care might be needed to reduce excess mortality.”

Related: VA to Reexamine 24,000 Veterans for TBI

The researchers suggest that public health agencies, including the VA, implement evidence-based, chronic disease self-management programs and supports that target physical and psychiatric comorbidity, study long-term outcomes, and ensure links to appropriate clinical and community health care facilities and social service providers.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives and acne in adolescents

Examining the impact of contraception on acne in adolescents is clinically important because acne affects about 85% of adolescents, and contraceptives may influence the course of acne disease. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives cause a significant improvement in acne.1,2 By contrast, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and the etonogestrel contraceptive implant may exacerbate acne. In this editorial we review the hormonal contraception−acne relationship, available acne treatments, and appropriate management.

Related article:

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

Combination oral contraception and acne

As noted, combination oral contraceptives generally result in acne improvement.1,2 Estrogen-progestin contraceptives improve the condition through two mechanisms. Primarily, estrogen-progestin contraceptives suppress pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion, thereby decreasing ovarian testosterone production. These contraceptives also increase liver production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing bound testosterone and decreasing free testosterone. The decrease in ovarian testosterone production and the increase in SHBG-bound testosterone reduce sebum production, resulting in acne improvement.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 estrogen-progestin contraceptives for acne treatment:

- Estrostep (norethindrone acetate-ethinyl estradiol plus ferrous fumarate)

- Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol)

- Yaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol)

- BeYaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol plus levomefolate).

LARC and acne

The levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs), including the levonorgestrel intrauterine systems Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, and Kyleena, and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon) are among the most effective contraceptives available for women. Over the last decade there has been a marked increase in the use of LARC. In 2002, 1.3% of women aged 15 to 24 years used an IUD or progestin implant, and this percentage increased to 10% by 2013.3

Progestin-containing LARC may cause acne to worsen. In a large 3-year prospective study of more than 2,900 women using the progestin implant or the copper IUD (ParaGard), use of the progestin implant was associated with a higher rate of reported acne than the copper IUD (18% vs 13%, respectively; relative risk, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.20−1.56; P<.0001).4 In a retrospective review of 991 women who used the etonogestrel implant, 24% of the women requested that the implant be removed; the 3 most common reasons for removal were: bleeding disturbances (45%), worsening acne, (12%) and desire to conceive (12%).5

Similar differences in reported acne are seen between the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD. In a study of 320 women using the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD, an increase in acne was reported by 17% and 7%, respectively (P<.025).6 In a small prospective study of the LNG-IUD versus the copper IUD over the first 12 months of use, use of the LNG-IUD was associated with a statistically significant worsening of acne scores while use of the copper IUD had no impact on acne scores.7

Related article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

In a study of 2,147 consecutive women using a hormonal contraceptive who presented to a dermatologist for the treatment of acne, patients were asked to assess how the contraceptive affected their acne. By type of contraceptive, the percent of women who reported that the contraceptive made their acne worse was: LNG-IUD, 36%; progestin implant, 33%; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), 27%; levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive, 10%; norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol (EE), 6%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 4%; drospirenone-EE, 3%; and desogestrel-EE, 2%. The percent of women who reported that the contraceptive significantly improved their acne was: drospirenone-EE, 26%; norgestimate-EE, 17%; desogestrel-EE, 15%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 14%; norethindrone-EE, 8%; levonorgestrel-EE, 6%; depot MPA, 5%; LNG-IUD, 3%; and progestin implant, 1%.8

In adolescents with acne, switching from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or an etonogestrel implant may cause the patient to report that her acne has worsened. As mentioned, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives reduce free testosterone, thereby improving acne. When an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is discontinued, free testosterone levels will increase. If a LARC method is initiated and the patient’s acne worsens, the patient may attribute this change to the LARC. For clinicians planning on switching a patient from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or etonogestrel implant, evaluation of current acne symptoms and acne history may be particularly important.

Acne treatment

Acne is caused by follicular hyperproliferation and abnormal desquamation, excess sebum production, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.

First-line agents. An expert guideline developed under the auspices of the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that topical agents including retinoids and antimicrobials be first-line treatments for acne.9,10

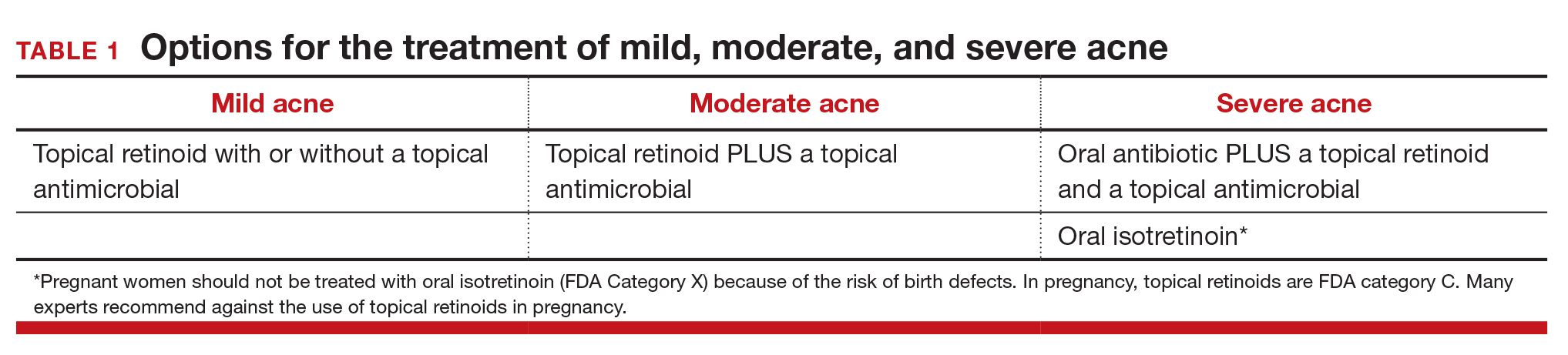

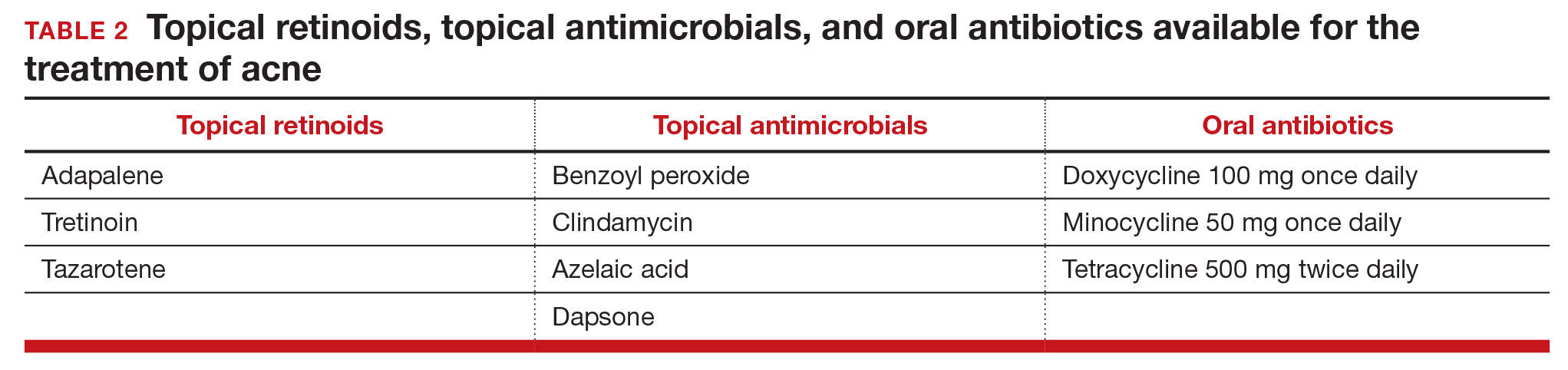

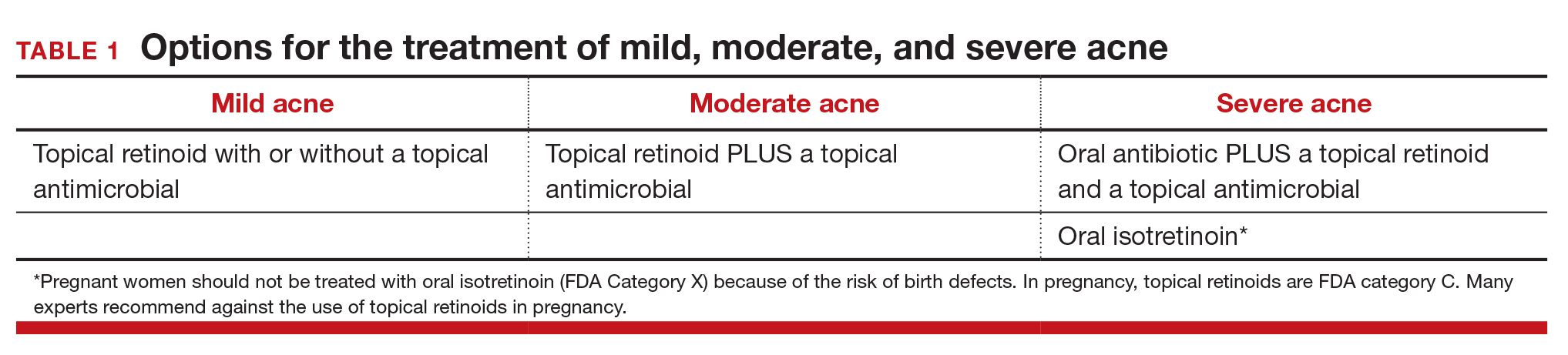

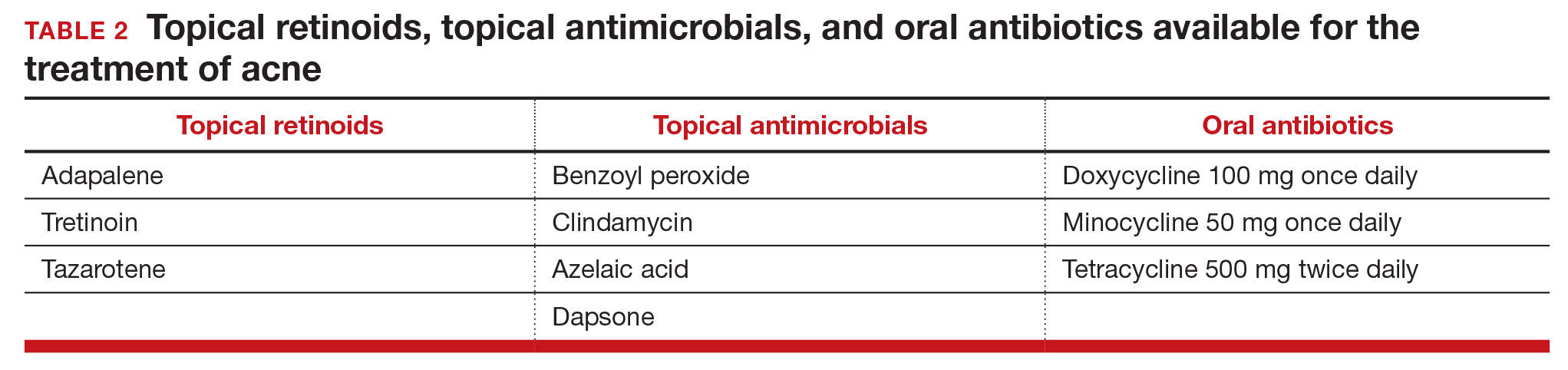

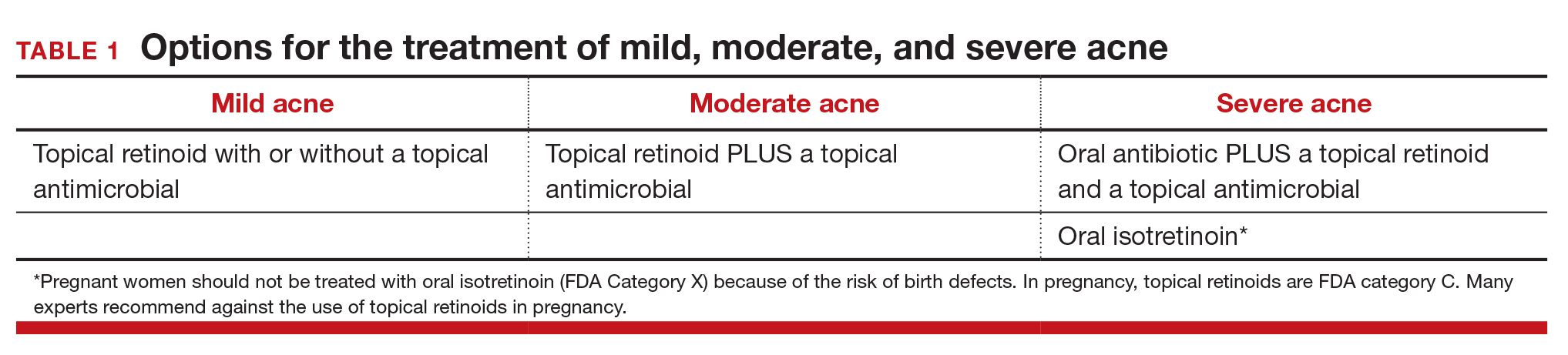

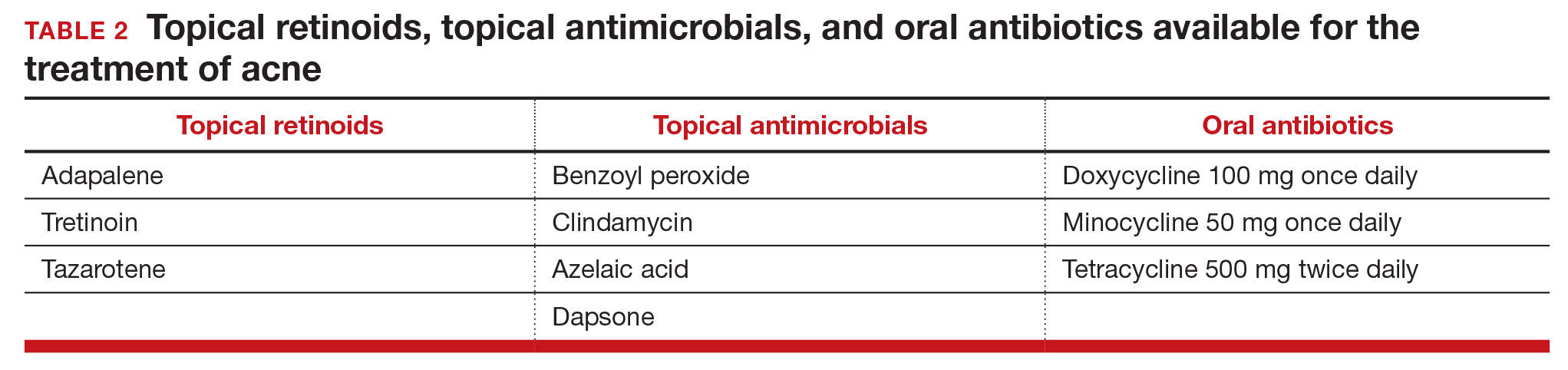

Topical retinoids are the primary component of topical acne treatment and can be used as monotherapy or in combination with topical antimicrobials (TABLE 1). Three topical retinoids are approved for use in the United States: tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. Adapalene is available by prescription, 0.1% and 0.3% gel, and over the counter, 0.1% gel (Differin Gel) (TABLE 2). The topical retinoids are applied once daily at bedtime and can cause local skin irritation and dryness. Pregnant women should not be treated with topical retinoids.

Topical antimicrobials for the treatment of acne include: benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, azelaic acid, and dapsone. Clindamycin is only recommended for use in combination with benzoyl peroxide in order to reduce the development of bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.

Related article:

Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweigh the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception?

Approach to mild, moderate, and severe acne. In adolescents with mild acne a topical retinoid or benzoyl peroxide can be used as monotherapy or used together. Referral to a dermatologist is recommended for moderate to severe acne. Moderate acne is treated with combination topical therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). Severe acne is treated with 3 months of oral antibiotics plus topical combination therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). In cases of severe nodular acne or acne that produces scarring the patient may require oral isotretinoin treatment.

Acne management for adolescents seeking LARC

Given the data that the LNG-IUD and the etonogestrel implant may worsen acne, it may be wise to preemptively ensure that adolescents with acne who are initiating these contraceptives are also being adequately treated for their acne. Gynecologists should provide anticipatory guidance for adolescents with mild acne who initiate progestin-based LARC. Topical benzoyl peroxide is available over-the-counter and can be recommended to these patients. Follow-up in clinic a few months after initiation also may be helpful to assess side effects.

In moderate and severe cases, coordination with dermatology is recommended. For these patients, gynecologists could consider prescribing a topical retinoid or antibiotic medication in conjunction with a new progestin-based LARC method. Those with severe acne also may benefit from concurrent use of oral contraceptives. In adolescents who do not tolerate progestin-based LARC, the copper IUD is a highly effective alternative and can be paired with estrogen-progestin contraception for acne treatment.

Related article:

With no budge in more than 20 years, are US unintended pregnancy rates finally on the decline?

Acne is but one consideration for contraceptive choice

With the above methods, acne can be managed in adolescents seeking a LNG-IUD or implant and should not be considered a contraindication or reason to avoid progestin-based LARC. Adolescents are more likely to continue LARC than estrogen-progestin contraceptives and LARC methods are associated with substantially lower pregnancy rates in this patient population.11 LARC is recommended as first-line contraception for adolescents by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.12,13

In choosing contraception with your adolescent patient, the risk of unintended pregnancy should be weighed against the risk of acne and other potential side effects. Do not select a contraceptive based on the presence or absence of acne disease. However, be aware that contraceptives can either improve or worsen acne. Patients with mild and moderate acne disease should be considered for treatment with topical retinoids and/or antimicrobial agents.

Dr. Barbieri reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Dr. Roe reports receiving grant or research support from the Society of Family Planning.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):450-459.

- Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, Mosher W. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15 to 44: United States 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;(86):1-14.

- Bahamondes L, Brache V, Meirik O, Ali M, Habib N, Landoulsi S; WHO Study Group on Contraceptive Implants for Women. A 3-year multicentre randomized controlled trial of etonogestrel- and levonorgestrel-releasing contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2527-2538.

- Bitzer J, Tschudin S, Adler J; Swiss Implanon Study Group. Acceptability and side-effects of Implanon in Switzerland: a retrospective study by the Implanon Swiss Study Group. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004;9(4):278-284.

- Nilsson CG, Luukkainen T, Diaz J, Allonen H. Clinical performance of a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. A randomized comparison with a Nova-T-copper device. Contraception. 1982;25(4):345-356.

- Kelekci S, Kelecki KH, Yilmaz B. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and T380A intrauterine copper device on dysmenorrhea and days of bleeding in women with and without adenomyosis. Contraception. 2012;86(5):458-463.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973.

- Roman CJ, Cifu AD, Stein SL. Management of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1402-1403.

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998-2007.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1244-e1256.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. Committee Opinion No. 539. Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(4):983-988.

Examining the impact of contraception on acne in adolescents is clinically important because acne affects about 85% of adolescents, and contraceptives may influence the course of acne disease. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives cause a significant improvement in acne.1,2 By contrast, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and the etonogestrel contraceptive implant may exacerbate acne. In this editorial we review the hormonal contraception−acne relationship, available acne treatments, and appropriate management.

Related article:

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

Combination oral contraception and acne

As noted, combination oral contraceptives generally result in acne improvement.1,2 Estrogen-progestin contraceptives improve the condition through two mechanisms. Primarily, estrogen-progestin contraceptives suppress pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion, thereby decreasing ovarian testosterone production. These contraceptives also increase liver production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing bound testosterone and decreasing free testosterone. The decrease in ovarian testosterone production and the increase in SHBG-bound testosterone reduce sebum production, resulting in acne improvement.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 estrogen-progestin contraceptives for acne treatment:

- Estrostep (norethindrone acetate-ethinyl estradiol plus ferrous fumarate)

- Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol)

- Yaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol)

- BeYaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol plus levomefolate).

LARC and acne

The levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs), including the levonorgestrel intrauterine systems Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, and Kyleena, and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon) are among the most effective contraceptives available for women. Over the last decade there has been a marked increase in the use of LARC. In 2002, 1.3% of women aged 15 to 24 years used an IUD or progestin implant, and this percentage increased to 10% by 2013.3

Progestin-containing LARC may cause acne to worsen. In a large 3-year prospective study of more than 2,900 women using the progestin implant or the copper IUD (ParaGard), use of the progestin implant was associated with a higher rate of reported acne than the copper IUD (18% vs 13%, respectively; relative risk, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.20−1.56; P<.0001).4 In a retrospective review of 991 women who used the etonogestrel implant, 24% of the women requested that the implant be removed; the 3 most common reasons for removal were: bleeding disturbances (45%), worsening acne, (12%) and desire to conceive (12%).5

Similar differences in reported acne are seen between the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD. In a study of 320 women using the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD, an increase in acne was reported by 17% and 7%, respectively (P<.025).6 In a small prospective study of the LNG-IUD versus the copper IUD over the first 12 months of use, use of the LNG-IUD was associated with a statistically significant worsening of acne scores while use of the copper IUD had no impact on acne scores.7

Related article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

In a study of 2,147 consecutive women using a hormonal contraceptive who presented to a dermatologist for the treatment of acne, patients were asked to assess how the contraceptive affected their acne. By type of contraceptive, the percent of women who reported that the contraceptive made their acne worse was: LNG-IUD, 36%; progestin implant, 33%; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), 27%; levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive, 10%; norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol (EE), 6%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 4%; drospirenone-EE, 3%; and desogestrel-EE, 2%. The percent of women who reported that the contraceptive significantly improved their acne was: drospirenone-EE, 26%; norgestimate-EE, 17%; desogestrel-EE, 15%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 14%; norethindrone-EE, 8%; levonorgestrel-EE, 6%; depot MPA, 5%; LNG-IUD, 3%; and progestin implant, 1%.8

In adolescents with acne, switching from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or an etonogestrel implant may cause the patient to report that her acne has worsened. As mentioned, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives reduce free testosterone, thereby improving acne. When an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is discontinued, free testosterone levels will increase. If a LARC method is initiated and the patient’s acne worsens, the patient may attribute this change to the LARC. For clinicians planning on switching a patient from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or etonogestrel implant, evaluation of current acne symptoms and acne history may be particularly important.

Acne treatment

Acne is caused by follicular hyperproliferation and abnormal desquamation, excess sebum production, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.

First-line agents. An expert guideline developed under the auspices of the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that topical agents including retinoids and antimicrobials be first-line treatments for acne.9,10

Topical retinoids are the primary component of topical acne treatment and can be used as monotherapy or in combination with topical antimicrobials (TABLE 1). Three topical retinoids are approved for use in the United States: tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. Adapalene is available by prescription, 0.1% and 0.3% gel, and over the counter, 0.1% gel (Differin Gel) (TABLE 2). The topical retinoids are applied once daily at bedtime and can cause local skin irritation and dryness. Pregnant women should not be treated with topical retinoids.

Topical antimicrobials for the treatment of acne include: benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, azelaic acid, and dapsone. Clindamycin is only recommended for use in combination with benzoyl peroxide in order to reduce the development of bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.

Related article:

Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweigh the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception?

Approach to mild, moderate, and severe acne. In adolescents with mild acne a topical retinoid or benzoyl peroxide can be used as monotherapy or used together. Referral to a dermatologist is recommended for moderate to severe acne. Moderate acne is treated with combination topical therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). Severe acne is treated with 3 months of oral antibiotics plus topical combination therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). In cases of severe nodular acne or acne that produces scarring the patient may require oral isotretinoin treatment.

Acne management for adolescents seeking LARC

Given the data that the LNG-IUD and the etonogestrel implant may worsen acne, it may be wise to preemptively ensure that adolescents with acne who are initiating these contraceptives are also being adequately treated for their acne. Gynecologists should provide anticipatory guidance for adolescents with mild acne who initiate progestin-based LARC. Topical benzoyl peroxide is available over-the-counter and can be recommended to these patients. Follow-up in clinic a few months after initiation also may be helpful to assess side effects.

In moderate and severe cases, coordination with dermatology is recommended. For these patients, gynecologists could consider prescribing a topical retinoid or antibiotic medication in conjunction with a new progestin-based LARC method. Those with severe acne also may benefit from concurrent use of oral contraceptives. In adolescents who do not tolerate progestin-based LARC, the copper IUD is a highly effective alternative and can be paired with estrogen-progestin contraception for acne treatment.

Related article:

With no budge in more than 20 years, are US unintended pregnancy rates finally on the decline?

Acne is but one consideration for contraceptive choice

With the above methods, acne can be managed in adolescents seeking a LNG-IUD or implant and should not be considered a contraindication or reason to avoid progestin-based LARC. Adolescents are more likely to continue LARC than estrogen-progestin contraceptives and LARC methods are associated with substantially lower pregnancy rates in this patient population.11 LARC is recommended as first-line contraception for adolescents by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.12,13

In choosing contraception with your adolescent patient, the risk of unintended pregnancy should be weighed against the risk of acne and other potential side effects. Do not select a contraceptive based on the presence or absence of acne disease. However, be aware that contraceptives can either improve or worsen acne. Patients with mild and moderate acne disease should be considered for treatment with topical retinoids and/or antimicrobial agents.

Dr. Barbieri reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Dr. Roe reports receiving grant or research support from the Society of Family Planning.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Examining the impact of contraception on acne in adolescents is clinically important because acne affects about 85% of adolescents, and contraceptives may influence the course of acne disease. Estrogen-progestin contraceptives cause a significant improvement in acne.1,2 By contrast, the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device and the etonogestrel contraceptive implant may exacerbate acne. In this editorial we review the hormonal contraception−acne relationship, available acne treatments, and appropriate management.

Related article:

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

Combination oral contraception and acne

As noted, combination oral contraceptives generally result in acne improvement.1,2 Estrogen-progestin contraceptives improve the condition through two mechanisms. Primarily, estrogen-progestin contraceptives suppress pituitary luteinizing hormone secretion, thereby decreasing ovarian testosterone production. These contraceptives also increase liver production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), thereby increasing bound testosterone and decreasing free testosterone. The decrease in ovarian testosterone production and the increase in SHBG-bound testosterone reduce sebum production, resulting in acne improvement.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved 4 estrogen-progestin contraceptives for acne treatment:

- Estrostep (norethindrone acetate-ethinyl estradiol plus ferrous fumarate)

- Ortho Tri-Cyclen (norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol)

- Yaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol)

- BeYaz (drospirenone-ethinyl estradiol plus levomefolate).

LARC and acne

The levonorgestrel intrauterine devices (LNG-IUDs), including the levonorgestrel intrauterine systems Mirena, Liletta, Skyla, and Kyleena, and the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon) are among the most effective contraceptives available for women. Over the last decade there has been a marked increase in the use of LARC. In 2002, 1.3% of women aged 15 to 24 years used an IUD or progestin implant, and this percentage increased to 10% by 2013.3

Progestin-containing LARC may cause acne to worsen. In a large 3-year prospective study of more than 2,900 women using the progestin implant or the copper IUD (ParaGard), use of the progestin implant was associated with a higher rate of reported acne than the copper IUD (18% vs 13%, respectively; relative risk, 1.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.20−1.56; P<.0001).4 In a retrospective review of 991 women who used the etonogestrel implant, 24% of the women requested that the implant be removed; the 3 most common reasons for removal were: bleeding disturbances (45%), worsening acne, (12%) and desire to conceive (12%).5

Similar differences in reported acne are seen between the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD. In a study of 320 women using the LNG-IUD and the copper IUD, an increase in acne was reported by 17% and 7%, respectively (P<.025).6 In a small prospective study of the LNG-IUD versus the copper IUD over the first 12 months of use, use of the LNG-IUD was associated with a statistically significant worsening of acne scores while use of the copper IUD had no impact on acne scores.7

Related article:

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

In a study of 2,147 consecutive women using a hormonal contraceptive who presented to a dermatologist for the treatment of acne, patients were asked to assess how the contraceptive affected their acne. By type of contraceptive, the percent of women who reported that the contraceptive made their acne worse was: LNG-IUD, 36%; progestin implant, 33%; depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), 27%; levonorgestrel-ethinyl estradiol oral contraceptive, 10%; norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol (EE), 6%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 4%; drospirenone-EE, 3%; and desogestrel-EE, 2%. The percent of women who reported that the contraceptive significantly improved their acne was: drospirenone-EE, 26%; norgestimate-EE, 17%; desogestrel-EE, 15%; etonogestrel-EE vaginal ring, 14%; norethindrone-EE, 8%; levonorgestrel-EE, 6%; depot MPA, 5%; LNG-IUD, 3%; and progestin implant, 1%.8

In adolescents with acne, switching from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or an etonogestrel implant may cause the patient to report that her acne has worsened. As mentioned, combination estrogen-progestin contraceptives reduce free testosterone, thereby improving acne. When an estrogen-progestin contraceptive is discontinued, free testosterone levels will increase. If a LARC method is initiated and the patient’s acne worsens, the patient may attribute this change to the LARC. For clinicians planning on switching a patient from an estrogen-progestin contraceptive to a LNG-IUD or etonogestrel implant, evaluation of current acne symptoms and acne history may be particularly important.

Acne treatment

Acne is caused by follicular hyperproliferation and abnormal desquamation, excess sebum production, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes, and inflammation.

First-line agents. An expert guideline developed under the auspices of the American Academy of Dermatology recommends that topical agents including retinoids and antimicrobials be first-line treatments for acne.9,10

Topical retinoids are the primary component of topical acne treatment and can be used as monotherapy or in combination with topical antimicrobials (TABLE 1). Three topical retinoids are approved for use in the United States: tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene. Adapalene is available by prescription, 0.1% and 0.3% gel, and over the counter, 0.1% gel (Differin Gel) (TABLE 2). The topical retinoids are applied once daily at bedtime and can cause local skin irritation and dryness. Pregnant women should not be treated with topical retinoids.

Topical antimicrobials for the treatment of acne include: benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, azelaic acid, and dapsone. Clindamycin is only recommended for use in combination with benzoyl peroxide in order to reduce the development of bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.

Related article:

Does the risk of unplanned pregnancy outweigh the risk of VTE from hormonal contraception?

Approach to mild, moderate, and severe acne. In adolescents with mild acne a topical retinoid or benzoyl peroxide can be used as monotherapy or used together. Referral to a dermatologist is recommended for moderate to severe acne. Moderate acne is treated with combination topical therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). Severe acne is treated with 3 months of oral antibiotics plus topical combination therapy (benzoyl peroxide plus a topical retinoid, a topical antibiotic, or both). In cases of severe nodular acne or acne that produces scarring the patient may require oral isotretinoin treatment.

Acne management for adolescents seeking LARC

Given the data that the LNG-IUD and the etonogestrel implant may worsen acne, it may be wise to preemptively ensure that adolescents with acne who are initiating these contraceptives are also being adequately treated for their acne. Gynecologists should provide anticipatory guidance for adolescents with mild acne who initiate progestin-based LARC. Topical benzoyl peroxide is available over-the-counter and can be recommended to these patients. Follow-up in clinic a few months after initiation also may be helpful to assess side effects.

In moderate and severe cases, coordination with dermatology is recommended. For these patients, gynecologists could consider prescribing a topical retinoid or antibiotic medication in conjunction with a new progestin-based LARC method. Those with severe acne also may benefit from concurrent use of oral contraceptives. In adolescents who do not tolerate progestin-based LARC, the copper IUD is a highly effective alternative and can be paired with estrogen-progestin contraception for acne treatment.

Related article:

With no budge in more than 20 years, are US unintended pregnancy rates finally on the decline?

Acne is but one consideration for contraceptive choice

With the above methods, acne can be managed in adolescents seeking a LNG-IUD or implant and should not be considered a contraindication or reason to avoid progestin-based LARC. Adolescents are more likely to continue LARC than estrogen-progestin contraceptives and LARC methods are associated with substantially lower pregnancy rates in this patient population.11 LARC is recommended as first-line contraception for adolescents by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.12,13

In choosing contraception with your adolescent patient, the risk of unintended pregnancy should be weighed against the risk of acne and other potential side effects. Do not select a contraceptive based on the presence or absence of acne disease. However, be aware that contraceptives can either improve or worsen acne. Patients with mild and moderate acne disease should be considered for treatment with topical retinoids and/or antimicrobial agents.

Dr. Barbieri reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Dr. Roe reports receiving grant or research support from the Society of Family Planning.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):450-459.

- Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, Mosher W. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15 to 44: United States 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;(86):1-14.

- Bahamondes L, Brache V, Meirik O, Ali M, Habib N, Landoulsi S; WHO Study Group on Contraceptive Implants for Women. A 3-year multicentre randomized controlled trial of etonogestrel- and levonorgestrel-releasing contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2527-2538.

- Bitzer J, Tschudin S, Adler J; Swiss Implanon Study Group. Acceptability and side-effects of Implanon in Switzerland: a retrospective study by the Implanon Swiss Study Group. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004;9(4):278-284.

- Nilsson CG, Luukkainen T, Diaz J, Allonen H. Clinical performance of a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. A randomized comparison with a Nova-T-copper device. Contraception. 1982;25(4):345-356.

- Kelekci S, Kelecki KH, Yilmaz B. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and T380A intrauterine copper device on dysmenorrhea and days of bleeding in women with and without adenomyosis. Contraception. 2012;86(5):458-463.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973.

- Roman CJ, Cifu AD, Stein SL. Management of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1402-1403.

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998-2007.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1244-e1256.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. Committee Opinion No. 539. Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(4):983-988.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(7):CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):450-459.

- Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J, Mosher W. Current contraceptive use and variation by selected characteristics among women aged 15 to 44: United States 2011-2013. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;(86):1-14.

- Bahamondes L, Brache V, Meirik O, Ali M, Habib N, Landoulsi S; WHO Study Group on Contraceptive Implants for Women. A 3-year multicentre randomized controlled trial of etonogestrel- and levonorgestrel-releasing contraceptive implants, with non-randomized matched copper-intrauterine device controls. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(11):2527-2538.

- Bitzer J, Tschudin S, Adler J; Swiss Implanon Study Group. Acceptability and side-effects of Implanon in Switzerland: a retrospective study by the Implanon Swiss Study Group. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004;9(4):278-284.

- Nilsson CG, Luukkainen T, Diaz J, Allonen H. Clinical performance of a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device. A randomized comparison with a Nova-T-copper device. Contraception. 1982;25(4):345-356.

- Kelekci S, Kelecki KH, Yilmaz B. Effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and T380A intrauterine copper device on dysmenorrhea and days of bleeding in women with and without adenomyosis. Contraception. 2012;86(5):458-463.

- Lortscher D, Admani S, Satur N, Eichenfield LF. Hormonal contraceptives and acne: a retrospective analysis of 2147 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(6):670-674.

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-973.

- Roman CJ, Cifu AD, Stein SL. Management of acne vulgaris. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1402-1403.

- Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1998-2007.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1244-e1256.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group. Committee Opinion No. 539. Adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120(4):983-988.

NIOSH Adds to Hazardous-Drugs List

Afatinib, axitinib, and belinostat head the list of 34 additions to the updated National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) List of Antineoplastic and Other Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare Settings. The list is “an important resource as well as a tool to raise awareness among workers about the hazards of some drugs,” said NIOSH Director John Howard, MD, “enabling workers to take the necessary steps to protect themselves from exposure while doing their job.”

The list includes drugs used for cancer chemotherapy, antiviral drugs, hormones, and bioengineered drugs. The 3 main categories are antineoplastic drugs (including those with manufacturer’s safe-handling guidance [MSHG]), nonantineoplastic drugs that meet ≥ 1 of the NIOSH criteria for hazardous drugs (including those with MSHG), and nonantineoplastic drugs that primarily have adverse reproductive effects.

NIOSH estimates that 8 million U.S. health care workers are potentially exposed to hazardous drugs in the workplace. Some drugs defined as hazardous may not pose a significant risk of direct occupational exposure until the formulations are altered (as when coated tablets are crushed). Other hazards include, for example, skin contact with or inhalation of dust as uncoated tablets are counted. Five of the newly added drugs have safe-handling recommendations.

NIOSH says “no single approach can cover the diverse potential occupational exposures to the drugs” and notes that safe-handling precautions can vary with the activity and formulation of the drug. Still, the list also provides general guidance for “possible scenarios” that might be encountered in health care settings where hazardous drugs are handled. It addresses situations such as receiving, unpacking, and placing drugs in storage; administering an intact tablet or capsule from a unit-dose package; cutting, crushing, or manipulating tablets or capsules; and compounding oral liquid drugs or topical drugs.

The new report also provides health care organizations with guidance on generating their own list of hazardous drugs. Hazardous drug evaluation is “a continual process,” NIOSH says, advising that every facility must assess each new drug that enters its workplace and when appropriate reassess its list of hazardous drugs as new toxicologic data become available.

The list of hazardous drugs is updated periodically at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hazdrug/.

Afatinib, axitinib, and belinostat head the list of 34 additions to the updated National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) List of Antineoplastic and Other Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare Settings. The list is “an important resource as well as a tool to raise awareness among workers about the hazards of some drugs,” said NIOSH Director John Howard, MD, “enabling workers to take the necessary steps to protect themselves from exposure while doing their job.”

The list includes drugs used for cancer chemotherapy, antiviral drugs, hormones, and bioengineered drugs. The 3 main categories are antineoplastic drugs (including those with manufacturer’s safe-handling guidance [MSHG]), nonantineoplastic drugs that meet ≥ 1 of the NIOSH criteria for hazardous drugs (including those with MSHG), and nonantineoplastic drugs that primarily have adverse reproductive effects.

NIOSH estimates that 8 million U.S. health care workers are potentially exposed to hazardous drugs in the workplace. Some drugs defined as hazardous may not pose a significant risk of direct occupational exposure until the formulations are altered (as when coated tablets are crushed). Other hazards include, for example, skin contact with or inhalation of dust as uncoated tablets are counted. Five of the newly added drugs have safe-handling recommendations.

NIOSH says “no single approach can cover the diverse potential occupational exposures to the drugs” and notes that safe-handling precautions can vary with the activity and formulation of the drug. Still, the list also provides general guidance for “possible scenarios” that might be encountered in health care settings where hazardous drugs are handled. It addresses situations such as receiving, unpacking, and placing drugs in storage; administering an intact tablet or capsule from a unit-dose package; cutting, crushing, or manipulating tablets or capsules; and compounding oral liquid drugs or topical drugs.

The new report also provides health care organizations with guidance on generating their own list of hazardous drugs. Hazardous drug evaluation is “a continual process,” NIOSH says, advising that every facility must assess each new drug that enters its workplace and when appropriate reassess its list of hazardous drugs as new toxicologic data become available.

The list of hazardous drugs is updated periodically at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hazdrug/.

Afatinib, axitinib, and belinostat head the list of 34 additions to the updated National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) List of Antineoplastic and Other Hazardous Drugs in Healthcare Settings. The list is “an important resource as well as a tool to raise awareness among workers about the hazards of some drugs,” said NIOSH Director John Howard, MD, “enabling workers to take the necessary steps to protect themselves from exposure while doing their job.”

The list includes drugs used for cancer chemotherapy, antiviral drugs, hormones, and bioengineered drugs. The 3 main categories are antineoplastic drugs (including those with manufacturer’s safe-handling guidance [MSHG]), nonantineoplastic drugs that meet ≥ 1 of the NIOSH criteria for hazardous drugs (including those with MSHG), and nonantineoplastic drugs that primarily have adverse reproductive effects.

NIOSH estimates that 8 million U.S. health care workers are potentially exposed to hazardous drugs in the workplace. Some drugs defined as hazardous may not pose a significant risk of direct occupational exposure until the formulations are altered (as when coated tablets are crushed). Other hazards include, for example, skin contact with or inhalation of dust as uncoated tablets are counted. Five of the newly added drugs have safe-handling recommendations.

NIOSH says “no single approach can cover the diverse potential occupational exposures to the drugs” and notes that safe-handling precautions can vary with the activity and formulation of the drug. Still, the list also provides general guidance for “possible scenarios” that might be encountered in health care settings where hazardous drugs are handled. It addresses situations such as receiving, unpacking, and placing drugs in storage; administering an intact tablet or capsule from a unit-dose package; cutting, crushing, or manipulating tablets or capsules; and compounding oral liquid drugs or topical drugs.

The new report also provides health care organizations with guidance on generating their own list of hazardous drugs. Hazardous drug evaluation is “a continual process,” NIOSH says, advising that every facility must assess each new drug that enters its workplace and when appropriate reassess its list of hazardous drugs as new toxicologic data become available.

The list of hazardous drugs is updated periodically at http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hazdrug/.

Letters to the Editor: Benefit of self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel in IUD placement

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures

The recent article by Dr. Kaunitz on the use of self-administered lidocaine gel prior to intrauterine device (IUD) placement was excellent. Having been known as the “lidocaine queen” in the Department of ObGyn at the Mayo Clinic, I feel strongly that gynecologic office procedures should always involve some form of anesthesia, whether with topical lidocaine, intracervical lidocaine, or paracervical block. Such anesthesia often makes the procedure a “nonevent” for the patient. While Dr. Kaunitz describes the use of a fine-toothed tenaculum, I have found that after administration of lidocaine gel, an Allis clamp applied superficially to the cervix provides sufficient traction, is often not detected by the patient, and does not leave any holes. It is unusual for it to slip off.

It is important to teach residents that it is not necessary for women to “tolerate” pain to have good health. I use the above techniques for endometrial biopsy and cervical biopsy as well—there is never a reason for a woman’s biopsy to be done without anesthesia.

Ingrid Carlson, MD

Ponte Vedra, Florida

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

“BENEFIT OF SELF-ADMINISTERED VAGINAL LIDOCAINE GEL IN IUD PLACEMENT"

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD (COMMENTARY; DECEMBER 2016)

Use anesthesia for in-office GYN procedures