User login

Transition to adult epilepsy care done right

Has this ever happened to you? You are an adult neurologist who has been asked to take on the care of a pediatric neurology patient. The patient who comes to your clinic is a 20-year-old young woman with a history of moderate developmental delay and intractable epilepsy. She is on numerous medications including valproic acid with a previous trial of the ketogenic diet. You receive a report that she has focal epilepsy and is having frequent seizures and last had an MRI at age 2 years. Prior notes talk about her summer vacations but not much about the future plans for her epilepsy. You see the patient in clinic, and the family is not happy to be in the adult clinic. They are disappointed that you don’t spend more time with them or fill out myriad forms. You find out that they have not obtained legal guardianship for their daughter and have no plan for work placement after school. She also has various other medical comorbidities that were previously addressed by the pediatric neurologist.

There is a not much evidence on the right way to do this. In 2013, the American Epilepsy Society approved a Transition Tool that is helpful in outlining the steps for a successful transition, and in 2016, the Child Neurology Foundation put forth a consensus statement with eight principles to guide a successful transition. Transitions are an expectation of good care and they recommend that a written policy be present for all offices.

Talking about transitioning should start as early as 10-12 years of age and should be discussed every year. Thinking about prognosis and a realistic plan for each child as they enter adult life is important. Patients and families should be able to understand how the disease affects them, what their medications are and how to independently obtain them, what comorbidities are associated with their disease, how to stay healthy, how to improve their quality of life, and how to advocate for themselves. As children become teenagers they should have a concrete plan for ongoing education, work, women’s issues, and an understanding of decision-making capacity and whether legal guardianship or a power of attorney needs to be implemented.

, even if they are still seen in the pediatric setting. A transition packet should be created that includes a summary of the diagnosis, work-up, previous treatments, and considerations for future treatments and emergency care. Also included is a plan for who will continue to address any non–seizure-related diagnoses the pediatric neurologist may have been managing. The patient and family also have an opportunity to review and contribute to this. This packet enables the adult neurologist to easily understand all issues and assume care of the patient, easing this aspect of the transition.

An advance meeting of the patient and family with the adult provider should be arranged whenever possible. To address this, some centers are now creating a transition clinic staffed by both pediatric and adult neurologists and/or nurses. This ideally takes place in the adult setting and is an excellent way to smooth the transition for the patient, family, and providers. Good transition is important to help prevent gaps in care, avoid reinventing the wheel, and improve satisfaction for everyone involved (patient, family, nurses, and neurologists). The key points are that transition discussions start early, patients and families should be involved and empowered in the process, and the creation of a transition packet for the adult provider is very helpful. Care transitions are something we will be hearing a lot more about in the upcoming years. And, hopefully, next time, the patient scenario seen above will go more smoothly!

Dr. Felton is an epilepsy specialist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and Dr. Kelley is director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Monitoring Unit at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. This editorial reflects the content of a presentation given by Dr. Felton and Dr. Kelley at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society in Houston. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Has this ever happened to you? You are an adult neurologist who has been asked to take on the care of a pediatric neurology patient. The patient who comes to your clinic is a 20-year-old young woman with a history of moderate developmental delay and intractable epilepsy. She is on numerous medications including valproic acid with a previous trial of the ketogenic diet. You receive a report that she has focal epilepsy and is having frequent seizures and last had an MRI at age 2 years. Prior notes talk about her summer vacations but not much about the future plans for her epilepsy. You see the patient in clinic, and the family is not happy to be in the adult clinic. They are disappointed that you don’t spend more time with them or fill out myriad forms. You find out that they have not obtained legal guardianship for their daughter and have no plan for work placement after school. She also has various other medical comorbidities that were previously addressed by the pediatric neurologist.

There is a not much evidence on the right way to do this. In 2013, the American Epilepsy Society approved a Transition Tool that is helpful in outlining the steps for a successful transition, and in 2016, the Child Neurology Foundation put forth a consensus statement with eight principles to guide a successful transition. Transitions are an expectation of good care and they recommend that a written policy be present for all offices.

Talking about transitioning should start as early as 10-12 years of age and should be discussed every year. Thinking about prognosis and a realistic plan for each child as they enter adult life is important. Patients and families should be able to understand how the disease affects them, what their medications are and how to independently obtain them, what comorbidities are associated with their disease, how to stay healthy, how to improve their quality of life, and how to advocate for themselves. As children become teenagers they should have a concrete plan for ongoing education, work, women’s issues, and an understanding of decision-making capacity and whether legal guardianship or a power of attorney needs to be implemented.

, even if they are still seen in the pediatric setting. A transition packet should be created that includes a summary of the diagnosis, work-up, previous treatments, and considerations for future treatments and emergency care. Also included is a plan for who will continue to address any non–seizure-related diagnoses the pediatric neurologist may have been managing. The patient and family also have an opportunity to review and contribute to this. This packet enables the adult neurologist to easily understand all issues and assume care of the patient, easing this aspect of the transition.

An advance meeting of the patient and family with the adult provider should be arranged whenever possible. To address this, some centers are now creating a transition clinic staffed by both pediatric and adult neurologists and/or nurses. This ideally takes place in the adult setting and is an excellent way to smooth the transition for the patient, family, and providers. Good transition is important to help prevent gaps in care, avoid reinventing the wheel, and improve satisfaction for everyone involved (patient, family, nurses, and neurologists). The key points are that transition discussions start early, patients and families should be involved and empowered in the process, and the creation of a transition packet for the adult provider is very helpful. Care transitions are something we will be hearing a lot more about in the upcoming years. And, hopefully, next time, the patient scenario seen above will go more smoothly!

Dr. Felton is an epilepsy specialist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and Dr. Kelley is director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Monitoring Unit at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. This editorial reflects the content of a presentation given by Dr. Felton and Dr. Kelley at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society in Houston. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Has this ever happened to you? You are an adult neurologist who has been asked to take on the care of a pediatric neurology patient. The patient who comes to your clinic is a 20-year-old young woman with a history of moderate developmental delay and intractable epilepsy. She is on numerous medications including valproic acid with a previous trial of the ketogenic diet. You receive a report that she has focal epilepsy and is having frequent seizures and last had an MRI at age 2 years. Prior notes talk about her summer vacations but not much about the future plans for her epilepsy. You see the patient in clinic, and the family is not happy to be in the adult clinic. They are disappointed that you don’t spend more time with them or fill out myriad forms. You find out that they have not obtained legal guardianship for their daughter and have no plan for work placement after school. She also has various other medical comorbidities that were previously addressed by the pediatric neurologist.

There is a not much evidence on the right way to do this. In 2013, the American Epilepsy Society approved a Transition Tool that is helpful in outlining the steps for a successful transition, and in 2016, the Child Neurology Foundation put forth a consensus statement with eight principles to guide a successful transition. Transitions are an expectation of good care and they recommend that a written policy be present for all offices.

Talking about transitioning should start as early as 10-12 years of age and should be discussed every year. Thinking about prognosis and a realistic plan for each child as they enter adult life is important. Patients and families should be able to understand how the disease affects them, what their medications are and how to independently obtain them, what comorbidities are associated with their disease, how to stay healthy, how to improve their quality of life, and how to advocate for themselves. As children become teenagers they should have a concrete plan for ongoing education, work, women’s issues, and an understanding of decision-making capacity and whether legal guardianship or a power of attorney needs to be implemented.

, even if they are still seen in the pediatric setting. A transition packet should be created that includes a summary of the diagnosis, work-up, previous treatments, and considerations for future treatments and emergency care. Also included is a plan for who will continue to address any non–seizure-related diagnoses the pediatric neurologist may have been managing. The patient and family also have an opportunity to review and contribute to this. This packet enables the adult neurologist to easily understand all issues and assume care of the patient, easing this aspect of the transition.

An advance meeting of the patient and family with the adult provider should be arranged whenever possible. To address this, some centers are now creating a transition clinic staffed by both pediatric and adult neurologists and/or nurses. This ideally takes place in the adult setting and is an excellent way to smooth the transition for the patient, family, and providers. Good transition is important to help prevent gaps in care, avoid reinventing the wheel, and improve satisfaction for everyone involved (patient, family, nurses, and neurologists). The key points are that transition discussions start early, patients and families should be involved and empowered in the process, and the creation of a transition packet for the adult provider is very helpful. Care transitions are something we will be hearing a lot more about in the upcoming years. And, hopefully, next time, the patient scenario seen above will go more smoothly!

Dr. Felton is an epilepsy specialist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and Dr. Kelley is director of the Pediatric Epilepsy Monitoring Unit at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. This editorial reflects the content of a presentation given by Dr. Felton and Dr. Kelley at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society in Houston. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Treatment adherence makes big impact in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

HOUSTON – Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures who stick with evidence-based treatment have significantly fewer seizures and have less associated disability than do those who don’t make it to therapy and psychiatry visits, a study showed.

Reporting preliminary data from 59 patients in a 123-patient study, Benjamin Tolchin, MD, and his colleagues said that patients who adhered to their treatment plans were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in seizure frequency of more than 50%, compared with nonadherent patients (P = .018). Treatment dropout was positively associated with having a prior psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) diagnosis and with having less concern about the illness.

These figures, he said, are consistent with what’s been reported in the PNES literature. Others have found that after diagnosis, 20%-30% of patients don’t attend their first appointment, although psychiatric treatment and therapy constitute evidence-based care that is effective in treating PNES.

Dr. Tolchin said previous studies have found that “over 71% of patients were found to have seizures and associated disability at the 4-year follow-up mark.”

In addition to tracking adherence, Dr. Tolchin and his coinvestigators attempted to identify risk factors for nonadherence among their patient cohort, all of whom had documented PNES. Study participants provided general demographic data, and investigators also gathered information about PNES event frequency; any prior diagnosis of PNES or other psychiatric comorbidities; history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; and health care resource utilization. Patients also were asked about their quality of life and time from symptom onset to receiving the PNES diagnosis.

Finally, patients filled out the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ). This instrument measures various aspects of patients’ cognitive and emotional representations of illness, using a nine-item questionnaire. Higher scores indicate that the patient sees the illness as more concerning.

All patients were referred for both psychotherapy and four follow-up visits with a psychiatrist. The first psychiatric visit was to occur within 1-2 months after receiving the PNES diagnosis, with the next two visits occurring at 1.5- to 3-month intervals following the first visit. The final scheduled follow-up visit was to occur 6-9 months after the third visit.

Most patients (85%) were female and non-Hispanic white (77%), with a mean age of 38 years (range, 18-80). About one-third of patients were single, and another third were married. The remainder were evenly split between having a live-in partner and being separated or divorced, with just 2% being widowed.

By self-report, more than one-third of patients (37%) were on disability, and nearly one-quarter (24%) were unemployed. Just 18% were working full time; another 11% worked part time, and 8% were students.

The median weekly number of PNES episodes per patient was two, although reported events per week ranged from 0 to 350.

Psychiatric comorbidities were very frequent: 94% of patients reported some variety of psychiatric disorder. Depressive disorders were reported by 78% of patients, anxiety disorders by 61%, and posttraumatic stress disorder by 54%. Other commonly reported psychiatric diagnoses included panic disorder (40%), phobias (38%), and personality disorders (31%).

Almost a quarter of patients (23%) had attempted suicide in the past, and the same percentage reported a history of substance abuse. Patient reports of emotional (57%), physical (45%), and sexual (42%) abuse were also common.

Having a prior diagnosis of PNES was identified as a significant risk factor for dropping out of treatment (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.46; P = .046]. Patients with a higher concern for their illness, as evidenced by a higher BIPQ score, were less likely to drop out of treatment (HR, 0.77 for 10-point increment; 95% CI, 0.64-0.93; P = .008).

“Neurologists and behavioral health specialists need new interventions to improve adherence with treatment and prevent long-term disability,” Dr. Tolchin said.

The study, which won the Kaufman Honor for the highest-ranking abstract in the comorbidities topic category at the meeting, was supported by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures who stick with evidence-based treatment have significantly fewer seizures and have less associated disability than do those who don’t make it to therapy and psychiatry visits, a study showed.

Reporting preliminary data from 59 patients in a 123-patient study, Benjamin Tolchin, MD, and his colleagues said that patients who adhered to their treatment plans were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in seizure frequency of more than 50%, compared with nonadherent patients (P = .018). Treatment dropout was positively associated with having a prior psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) diagnosis and with having less concern about the illness.

These figures, he said, are consistent with what’s been reported in the PNES literature. Others have found that after diagnosis, 20%-30% of patients don’t attend their first appointment, although psychiatric treatment and therapy constitute evidence-based care that is effective in treating PNES.

Dr. Tolchin said previous studies have found that “over 71% of patients were found to have seizures and associated disability at the 4-year follow-up mark.”

In addition to tracking adherence, Dr. Tolchin and his coinvestigators attempted to identify risk factors for nonadherence among their patient cohort, all of whom had documented PNES. Study participants provided general demographic data, and investigators also gathered information about PNES event frequency; any prior diagnosis of PNES or other psychiatric comorbidities; history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; and health care resource utilization. Patients also were asked about their quality of life and time from symptom onset to receiving the PNES diagnosis.

Finally, patients filled out the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ). This instrument measures various aspects of patients’ cognitive and emotional representations of illness, using a nine-item questionnaire. Higher scores indicate that the patient sees the illness as more concerning.

All patients were referred for both psychotherapy and four follow-up visits with a psychiatrist. The first psychiatric visit was to occur within 1-2 months after receiving the PNES diagnosis, with the next two visits occurring at 1.5- to 3-month intervals following the first visit. The final scheduled follow-up visit was to occur 6-9 months after the third visit.

Most patients (85%) were female and non-Hispanic white (77%), with a mean age of 38 years (range, 18-80). About one-third of patients were single, and another third were married. The remainder were evenly split between having a live-in partner and being separated or divorced, with just 2% being widowed.

By self-report, more than one-third of patients (37%) were on disability, and nearly one-quarter (24%) were unemployed. Just 18% were working full time; another 11% worked part time, and 8% were students.

The median weekly number of PNES episodes per patient was two, although reported events per week ranged from 0 to 350.

Psychiatric comorbidities were very frequent: 94% of patients reported some variety of psychiatric disorder. Depressive disorders were reported by 78% of patients, anxiety disorders by 61%, and posttraumatic stress disorder by 54%. Other commonly reported psychiatric diagnoses included panic disorder (40%), phobias (38%), and personality disorders (31%).

Almost a quarter of patients (23%) had attempted suicide in the past, and the same percentage reported a history of substance abuse. Patient reports of emotional (57%), physical (45%), and sexual (42%) abuse were also common.

Having a prior diagnosis of PNES was identified as a significant risk factor for dropping out of treatment (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.46; P = .046]. Patients with a higher concern for their illness, as evidenced by a higher BIPQ score, were less likely to drop out of treatment (HR, 0.77 for 10-point increment; 95% CI, 0.64-0.93; P = .008).

“Neurologists and behavioral health specialists need new interventions to improve adherence with treatment and prevent long-term disability,” Dr. Tolchin said.

The study, which won the Kaufman Honor for the highest-ranking abstract in the comorbidities topic category at the meeting, was supported by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures who stick with evidence-based treatment have significantly fewer seizures and have less associated disability than do those who don’t make it to therapy and psychiatry visits, a study showed.

Reporting preliminary data from 59 patients in a 123-patient study, Benjamin Tolchin, MD, and his colleagues said that patients who adhered to their treatment plans were significantly more likely to experience a reduction in seizure frequency of more than 50%, compared with nonadherent patients (P = .018). Treatment dropout was positively associated with having a prior psychogenic nonepileptic seizure (PNES) diagnosis and with having less concern about the illness.

These figures, he said, are consistent with what’s been reported in the PNES literature. Others have found that after diagnosis, 20%-30% of patients don’t attend their first appointment, although psychiatric treatment and therapy constitute evidence-based care that is effective in treating PNES.

Dr. Tolchin said previous studies have found that “over 71% of patients were found to have seizures and associated disability at the 4-year follow-up mark.”

In addition to tracking adherence, Dr. Tolchin and his coinvestigators attempted to identify risk factors for nonadherence among their patient cohort, all of whom had documented PNES. Study participants provided general demographic data, and investigators also gathered information about PNES event frequency; any prior diagnosis of PNES or other psychiatric comorbidities; history of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse; and health care resource utilization. Patients also were asked about their quality of life and time from symptom onset to receiving the PNES diagnosis.

Finally, patients filled out the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ). This instrument measures various aspects of patients’ cognitive and emotional representations of illness, using a nine-item questionnaire. Higher scores indicate that the patient sees the illness as more concerning.

All patients were referred for both psychotherapy and four follow-up visits with a psychiatrist. The first psychiatric visit was to occur within 1-2 months after receiving the PNES diagnosis, with the next two visits occurring at 1.5- to 3-month intervals following the first visit. The final scheduled follow-up visit was to occur 6-9 months after the third visit.

Most patients (85%) were female and non-Hispanic white (77%), with a mean age of 38 years (range, 18-80). About one-third of patients were single, and another third were married. The remainder were evenly split between having a live-in partner and being separated or divorced, with just 2% being widowed.

By self-report, more than one-third of patients (37%) were on disability, and nearly one-quarter (24%) were unemployed. Just 18% were working full time; another 11% worked part time, and 8% were students.

The median weekly number of PNES episodes per patient was two, although reported events per week ranged from 0 to 350.

Psychiatric comorbidities were very frequent: 94% of patients reported some variety of psychiatric disorder. Depressive disorders were reported by 78% of patients, anxiety disorders by 61%, and posttraumatic stress disorder by 54%. Other commonly reported psychiatric diagnoses included panic disorder (40%), phobias (38%), and personality disorders (31%).

Almost a quarter of patients (23%) had attempted suicide in the past, and the same percentage reported a history of substance abuse. Patient reports of emotional (57%), physical (45%), and sexual (42%) abuse were also common.

Having a prior diagnosis of PNES was identified as a significant risk factor for dropping out of treatment (hazard ratio, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-2.46; P = .046]. Patients with a higher concern for their illness, as evidenced by a higher BIPQ score, were less likely to drop out of treatment (HR, 0.77 for 10-point increment; 95% CI, 0.64-0.93; P = .008).

“Neurologists and behavioral health specialists need new interventions to improve adherence with treatment and prevent long-term disability,” Dr. Tolchin said.

The study, which won the Kaufman Honor for the highest-ranking abstract in the comorbidities topic category at the meeting, was supported by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Adherent patients were more likely to reduce their seizures by half or more (P = .018).

Data source: A study of 123 patients with documented PNES.

Disclosures: The study was funded by a practice research training fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Brain Foundation. Dr. Tolchin reported no other disclosures.

Clinical Challenges - January 2017

What’s your diagnosis?

The diagnosis

The radiographic and pathologic findings and the patient’s clinical presentation were most consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, which are manifestations of IgG4-related disease. IgG4-related disease is a fibroinflammatory condition that has been described in almost every organ system. Elevated serum IgG4 levels suggest this diagnosis, but many times remain normal.1,2 Therefore, a strong clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy of the affected tissue, which will show a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate organized in a matted and irregularly whorled pattern.2,3 Making a diagnosis requires immunohistochemical confirmation with IgG4 immunostaining of plasma cells.

The patient was started on prednisone followed by azathioprine and experienced a rapid and sustained clinical and biochemical response even after stopping immunosuppressive therapy. After treatment, repeat imaging studies were performed, which showed dramatic improvement in the above-mentioned abnormalities. Abdominal CT showed a decrease in size of the pancreatic head (Figure C) and repeat cholangiogram showed resolution of biliary stenoses (Figure D).

References

1. Oseini, A.M., Chaiteerakij, R., Shire, A.M., et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940-8.

2. Takuma, K., Kamisawa, T., Gopalakrishna, R., et al. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1015-20.

3. Stone, J.H., Zen, Y., Deshpande, V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539-51.

The diagnosis

The radiographic and pathologic findings and the patient’s clinical presentation were most consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, which are manifestations of IgG4-related disease. IgG4-related disease is a fibroinflammatory condition that has been described in almost every organ system. Elevated serum IgG4 levels suggest this diagnosis, but many times remain normal.1,2 Therefore, a strong clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy of the affected tissue, which will show a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate organized in a matted and irregularly whorled pattern.2,3 Making a diagnosis requires immunohistochemical confirmation with IgG4 immunostaining of plasma cells.

The patient was started on prednisone followed by azathioprine and experienced a rapid and sustained clinical and biochemical response even after stopping immunosuppressive therapy. After treatment, repeat imaging studies were performed, which showed dramatic improvement in the above-mentioned abnormalities. Abdominal CT showed a decrease in size of the pancreatic head (Figure C) and repeat cholangiogram showed resolution of biliary stenoses (Figure D).

References

1. Oseini, A.M., Chaiteerakij, R., Shire, A.M., et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940-8.

2. Takuma, K., Kamisawa, T., Gopalakrishna, R., et al. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1015-20.

3. Stone, J.H., Zen, Y., Deshpande, V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539-51.

The diagnosis

The radiographic and pathologic findings and the patient’s clinical presentation were most consistent with autoimmune pancreatitis and IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis, which are manifestations of IgG4-related disease. IgG4-related disease is a fibroinflammatory condition that has been described in almost every organ system. Elevated serum IgG4 levels suggest this diagnosis, but many times remain normal.1,2 Therefore, a strong clinical suspicion should prompt a biopsy of the affected tissue, which will show a dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate organized in a matted and irregularly whorled pattern.2,3 Making a diagnosis requires immunohistochemical confirmation with IgG4 immunostaining of plasma cells.

The patient was started on prednisone followed by azathioprine and experienced a rapid and sustained clinical and biochemical response even after stopping immunosuppressive therapy. After treatment, repeat imaging studies were performed, which showed dramatic improvement in the above-mentioned abnormalities. Abdominal CT showed a decrease in size of the pancreatic head (Figure C) and repeat cholangiogram showed resolution of biliary stenoses (Figure D).

References

1. Oseini, A.M., Chaiteerakij, R., Shire, A.M., et al. Utility of serum immunoglobulin G4 in distinguishing immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis from cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 2011;54:940-8.

2. Takuma, K., Kamisawa, T., Gopalakrishna, R., et al. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1015-20.

3. Stone, J.H., Zen, Y., Deshpande, V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539-51.

What’s your diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

What’s your diagnosis?

By Victoria Gómez, MD, and Jaime Aranda-Michel, MD. Published previously in Gastroenterology (2012 Dec;143[6]:1441, 1694).

A 65-year-old woman was evaluated for recurrent painless jaundice. Prior investigations at an outside institution included an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography that showed a stricture in the distal common bile duct with a negative cytology for malignant cells. She underwent laparotomy, during which a pancreatic head mass was found and biopsies revealed no malignancy. A palliative cholecystojejunostomy with gastroenterostomy was performed. Postoperatively, the jaundice improved but she had epigastric pain, persistent nausea, anorexia, and a 20-pound weight loss. Two weeks later she developed recurrent jaundice, and a second endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography demonstrated a hilar stricture. A presumptive diagnosis of multicentric cholangiocarcinoma was made and she was referred to hospice care. She then sought another opinion regarding her condition at our institution.

Patch Testing for Adverse Drug Reactions

Adverse drug reactions account for 3% to 6% of hospital admissions in the United States and occur in 10% to 15% of hospitalized patients.1,2 The most common culprits are antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-12 In most cases, diagnoses are made clinically without diagnostic testing. To identify drug allergies associated with diagnostic testing, one center selected patients with suspected cutaneous drug reactions (2006-2010) for further evaluation.13 Of 612 patients who were evaluated, 141 had a high suspicion of drug allergy and were included in the analysis. The excluded patients had pseudoallergic reactions, reactive exanthemas due to infection, histopathologic exclusion of drug allergy, angioedema, or other dermatological conditions such as contact dermatitis and eczema. Of the included patients, 107 were diagnosed with drug reactions, while the remainder had non–drug-related exanthemas or unknown etiology after testing. Identified culprit drugs were predominantly antibiotics (39.8%) and NSAIDs (21.2%); contrast media, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, antimalarials, antifungals, glucocorticoids, antihypertensives, and proton pump inhibitors also were implicated. They were identified with skin prick, intradermal, and patch tests (62.6%); lymphocyte transformation test (17.7%); oral rechallenge (5.6%); or without skin testing (6.5%). One quarter of patients with a high suspicion for drug allergy did not have a confirmed drug eruption in this study. Another study found that 10% to 20% of patients with reported penicillin allergy had confirmation via skin prick testing.14 These findings suggest that confirmation of suspected drug allergy may require more than one diagnostic test.

Tests for Adverse Drug Reactions

The following tests have been shown to aid in the identification of cutaneous drug eruptions: (1) patch tests15-21; (2) intradermal tests14,15,19,20; (3) drug provocation tests15,20; and (4) lymphocyte transformation tests.20 Intradermal or skin prick tests are most useful in urticarial eruptions but can be considered in nonurticarial eruptions with delayed inspection of test sites up to 1 week after testing. Drug provocation tests are considered the gold standard but involve patient risk. Lymphocyte transformation tests use the principle that T lymphocytes proliferate in the presence of drugs to which the patient is sensitized. Patch tests will be discussed in greater detail below. Immunohistochemistry can determine immunologic mechanisms of eruptions but cannot identify causative agents.16,17,22

A retrospective study of patients referred for evaluation of adverse drug reactions between 1996 and 2006 found the collective negative predictive value (NPV)—the percentage of truly negative skin tests based on provocation or substitution testing—of cutaneous drug tests including patch, prick, and intradermal tests to be 89.6% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-93.3%).23 The NPVs of each test were not reported. Patients with negative cutaneous tests had subsequent oral rechallenge or substitution testing with medication from the same drug class.23 Another study16 found the NPV of patch testing to be at least 79% after review of data from other studies using patch and provocation testing.16,24 These studies suggest that cutaneous testing can be useful, albeit imperfect, in the evaluation and diagnosis of drug allergy.

Review of the Patch Test

Patch tests can be helpful in diagnosis of delayed hypersensitivities.18 Patch testing is most commonly and effectively used to diagnose allergic contact dermatitis, but its utility in other applications, such as diagnosis of cutaneous drug eruptions, has not been extensively studied.

The development of patch tests to diagnose systemic drug allergies is inhibited by the uncertainty of percutaneous drug penetration, a dearth of studies to determine the best test concentrations of active drug in the patch test, and the potential for nonimmunologic contact urticaria upon skin exposure. Furthermore, cutaneous metabolism of many antigens is well documented, but correlation to systemic metabolism often is unknown, which can confound patch test results and lead to false-negative results when the skin’s metabolic capacity does not match the body’s capacity to generate antigens capable of eliciting immunogenic responses.21 Additionally, the method used to suspend and disperse drugs in patch test vehicles is unfamiliar to most pharmacists, and standardized concentrations and vehicles are available only for some medications.25 Studies sufficient to obtain US Food and Drug Administration approval of patch tests for systemic drug eruptions would be costly and therefore prohibitive to investigators. The majority of the literature consists of case reports and data extrapolated from reviews. Patch test results of many drugs have been reported in the literature, with the highest frequencies of positive results associated with anticonvulsants,26 antibiotics, corticosteroids, calcium channel blockers, and benzodiazepines.21

Patch test placement affects the diagnostic value of the test. Placing patch tests on previously involved sites of fixed drug eruptions improves yield over placement on uninvolved skin.27 Placing patch tests on previously involved sites of other drug eruptions such as toxic epidermal necrolysis also may aid in diagnosis, though the literature is sparse.25,26,28

Patch Testing in Drug Eruptions

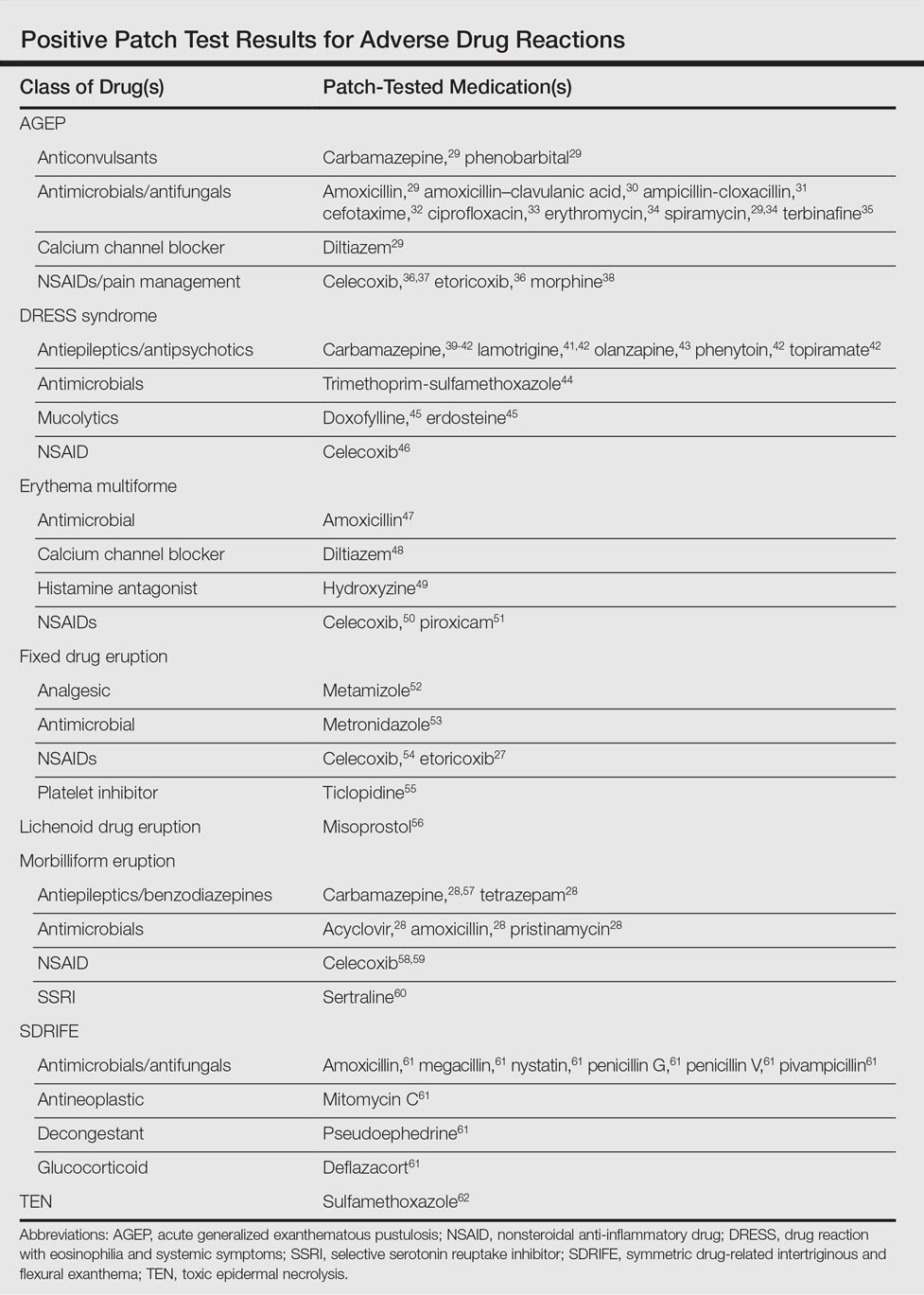

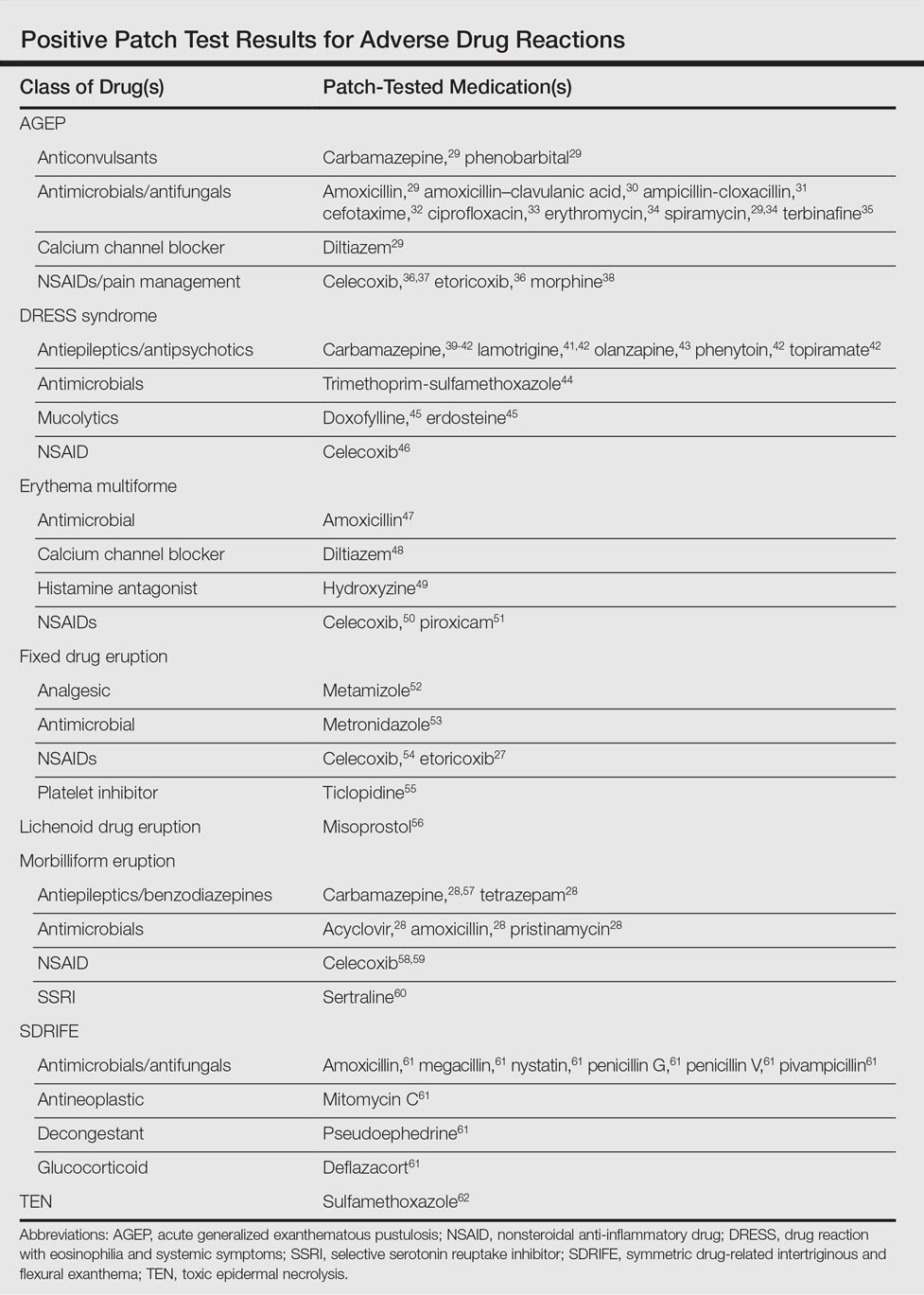

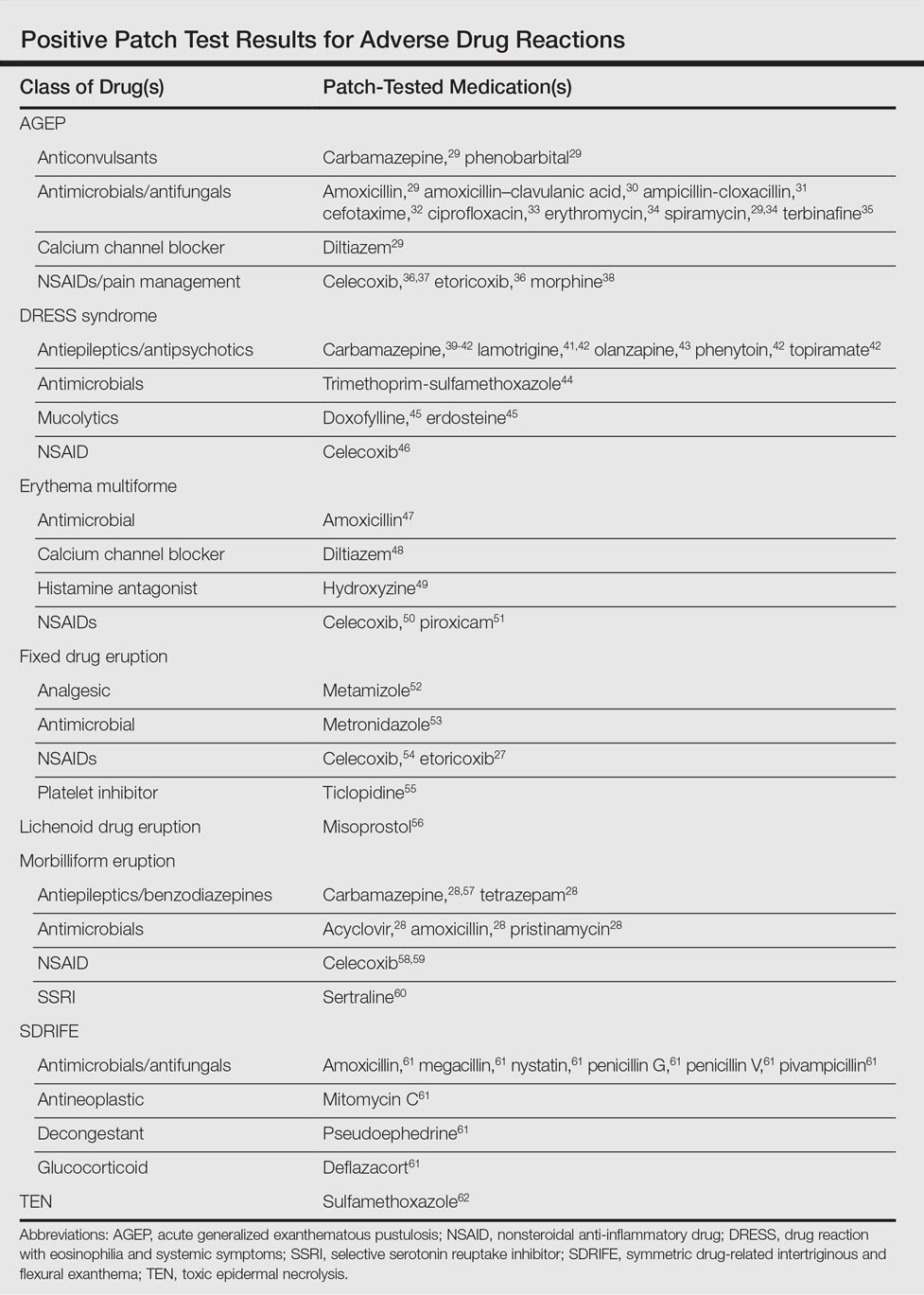

Morbilliform eruptions account for 48% to 91% of patients with adverse drug reactions.4-6 Other drug eruptions include urticarial eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, lichenoid drug eruption, symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE), erythema multiforme (EM), and systemic contact dermatitis. The Table summarizes reports of positive patch tests with various medications for these drug eruptions.

In general, antimicrobials and NSAIDs were the most implicated drugs with positive patch test results in AGEP, DRESS syndrome, EM, fixed drug eruptions, and morbilliform eruptions. In AGEP, positive results also were reported for other drugs, including terbinafine and morphine.29-38 In fixed drug eruptions, patch testing on involved skin showed positive results to NSAIDs, analgesics, platelet inhibitors, and antimicrobials.27,52-55 Patch testing in DRESS syndrome has shown many positive reactions to antiepileptics and antipsychotics.39-43 One study used patch tests in SDRIFE, reporting positive results with antimicrobials, antineoplastics, decongestants, and glucocorticoids.61 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobials, calcium channel blockers, and histamine antagonists were implicated in EM.47-51 Positive patch tests were seen in morbilliform eruptions with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antiepileptics/benzodiazepines, NSAIDs, and antimicrobials.28,57-60 In toxic epidermal necrolysis, diagnosis with patch testing was made using patches placed on previously involved skin with sulfamethoxazole.62

Systemic Contact Dermatitis

Drugs historically recognized as causing allergic contact dermatitis (eg, topical gentamycin) can cause systemic contact dermatitis, which can be patch tested. In these situations, systemic contact dermatitis may be due to either the active drug or excipients in the medication formulation. Excipients are inactive ingredients in medications that provide a suitable consistency, appearance, or form. Often overlooked as culprits of drug hypersensitivity because they are theoretically inert, excipients are increasingly implicated in drug allergy. Swerlick and Campbell63 described 11 cases in which chronic unexplained pruritus responded to medication changes to avoid coloring agents. The most common culprits were FD&C Blue No. 1 and FD&C Blue No. 2. Patch testing for allergies to dyes can be clinically useful, though a lack of commercially available patch tests makes diagnosis difficult.64

Other excipients can cause cutaneous reactions. Propylene glycol, commonly implicated in allergic contact dermatitis, also can cause cutaneous eruptions upon systemic exposure.65 Corticosteroid-induced systemic contact dermatitis has been reported, though it is less prevalent than allergic contact dermatitis.66 These reactions usually are due to nonmethylated and nonhalogenated corticosteroids including budesonide, cortisone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone.67,68 Patch testing in these situations is complicated by the possibility of false-negative results due to the anti-inflammatory effects of the corticosteroids. Therefore, patch testing should be performed using standardized and not treatment concentrations.

In our clinic, we have anecdotally observed several patients with chronic dermatitis and suspected NSAID allergies have positive patch test results with propylene glycol and not the suspected drug. Excipients encountered in multiple drugs and foods are more likely to present as chronic dermatitis, while active drug ingredients started in hospital settings more often present as acute dermatitis.

Our Experience

We have patch tested a handful of patients with suspected drug eruptions (University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center institutional review board #07-12-27). Medications, excipients, and their concentrations (in % weight per weight) and vehicles that were tested include ibuprofen (10% petrolatum), aspirin (10% petrolatum), hydrochlorothiazide (10% petrolatum), captopril (5% petrolatum), and propylene glycol (30% water or 5% petrolatum). Patch tests were read at 48 and 72 hours and scored according to the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group patch test scoring guidelines.69 Two patients tested for ibuprofen reacted positively only to propylene glycol; the 3 other patients did not react to aspirin, hydrochlorothiazide, and captopril. Overall, we observed no positive patch tests to medications and 2 positive tests to propylene glycol in 5 patients tested (unpublished data).

Areas of Uncertainty

Although tests for immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions to drugs exist as skin prick tests, diagnostic testing for the majority of drug reactions does not exist. Drug allergy diagnosis is made with history and temporality, potentially resulting in unnecessary avoidance of helpful medications. Ideal patch test concentrations and vehicles as well as the sensitivity and specificity of these tests are unknown.

Guidelines From Professional Societies

Drug allergy testing guidelines are available from the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology70 and American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.71 The guidelines recommend diagnosis by history and temporality, and it is stated that patch testing is potentially useful in maculopapular rashes, AGEP, fixed drug eruptions, and DRESS syndrome.

Conclusion

Case reports in the literature suggest the utility of patch testing in some drug allergies. We suggest testing excipients such as propylene glycol and benzoic acid to rule out systemic contact dermatitis when patch testing with active drugs to confirm cause of suspected adverse cutaneous reactions to medications.

- Arndt KA, Jick H. Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. JAMA. 1976;235:918-922.

- Bigby M, Jick S, Jick H, et al. Drug-induced cutaneous reactions. a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program on 15,483 consecutive inpatients, 1975 to 1982. JAMA. 1986;256:3358-3363.

- Fiszenson-Albala F, Auzerie V, Mahe E, et al. A 6-month prospective survey of cutaneous drug reactions in a hospital setting. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1018-1022.

- Thong BY, Leong KP, Tang CY, et al. Drug allergy in a general hospital: results of a novel prospective inpatient reporting system. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:342-347.

- Hunziker T, Kunzi UP, Braunschweig S, et al. Comprehensive hospital drug monitoring (CHDM): adverse skin reactions, a 20-year survey. Allergy. 1997;52:388-393.

- Swanbeck G, Dahlberg E. Cutaneous drug reactions. an attempt to quantitative estimation. Arch Dermatol Res. 1992;284:215-218.

- Naldi L, Conforti A, Venegoni M, et al. Cutaneous reactions to drugs. an analysis of spontaneous reports in four Italian regions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;48:839-846.

- French LE, Prins C. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. In: Bolognia, JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:319-333.

- Vasconcelos C, Magina S, Quirino P, et al. Cutaneous drug reactions to piroxicam. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;39:145.

- Gerber D. Adverse reactions of piroxicam. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1987;21:707-710.

- Revuz J, Valeyrie-Allanore L. Drug reactions. In: Bolognia, JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:335-356.

- Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: part II. management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:709.e1-709.e9; quiz 718-720.

- Heinzerling LM, Tomsitz D, Anliker MD. Is drug allergy less prevalent than previously assumed? a 5-year analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:107-114.

- Salkind AR, Cuddy PG. Is this patient allergic to penicillin?: an evidence-based analysis of the likelihood of penicillin allergy. JAMA. 2001;285:2498-2505.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Cham PM, Warshaw EM. Patch testing for evaluating drug reactions due to systemic antibiotics. Dermatitis. 2007;18:63-77.

- Andrade P, Brinca A, Gonçalo M. Patch testing in fixed drug eruptions—a 20-year review. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;65:195-201.

- Romano A, Viola M, Gaeta F, et al. Patch testing in non-immediate drug eruptions. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2008;4:66-74.

- Rosso R, Mattiacci G, Bernardi ML, et al. Very delayed reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:293-295.

- Romano A, Torres MJ, Castells M, et al. Diagnosis and management of drug hypersensitivity reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3 suppl):S67-S73.

- Friedmann PS, Ardern-Jones M. Patch testing in drug allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:291-296.

- Torres MJ, Mayorga C, Blanca M. Nonimmediate allergic reactions induced by drugs: pathogenesis and diagnostic tests. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19:80-90.

- Waton J, Tréchot P, Loss-Ayay C, et al. Negative predictive value of drug skin tests in investigating cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:786-794.

- Romano A, Viola M, Mondino C, et al. Diagnosing nonimmediate reactions to penicillins by in vivo tests. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2002;129:169-174.

- De Groot AC. Patch Testing. Test Concentrations and Vehicles for 4350 Chemicals. 3rd ed. Wapserveen, Netherlands: acdegroot publishing; 2008.

- Elzagallaai AA, Knowles SR, Rieder MJ, et al. Patch testing for the diagnosis of anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32:391-408.

- Andrade P, Gonçalo M. Fixed drug eruption caused by etoricoxib—2 cases confirmed by patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2011;64:118-120.

- Barbaud A, Reichert-Penetrat S, Tréchot P, et al. The use of skin testing in the investigation of cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:49-58.

- Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O, Fléchet ML, et al. Patch testing in severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions, including Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:234-236.

- Harries MJ, McIntyre SJ, Kingston TP. Co-amoxiclav-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by patch testing. Contact Dermatitis. 2006;55:372.

- Matsumoto Y, Okubo Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Case of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by ampicillin/cloxacillin sodium in a pregnant woman. J Dermatol. 2008;35:362-364.

- Chaabane A, Aouam K, Gassab L, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) induced by cefotaxime. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2010;24:429-432.

- Hausermann P, Scherer K, Weber M, et al. Ciprofloxacin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis mimicking bullous drug eruption confirmed by a positive patch test. Dermatology. 2005;211:277-280.

- Moreau A, Dompmartin A, Castel B, et al. Drug-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with positive patch tests. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:263-266.

- Kempinaire A, De Raevea L, Merckx M, et al. Terbinafine-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by a positive patch-test result. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:653-655.

- Mäkelä L, Lammintausta K. Etoricoxib-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:200-201.

- Yang CC, Lee JY, Chen WC. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by celecoxib. J Formos Med Assoc. 2004;103:555-557.

- Kardaun SH, de Monchy JG. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by morphine, confirmed by positive patch test and lymphocyte transformation test. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2 suppl):S21-S23.

- Inadomi T. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): changing carbamazepine to phenobarbital controlled epilepsy without the recurrence of DRESS. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:220-222.

- Buyuktiryaki AB, Bezirganoglu H, Sahiner UM, et al. Patch testing is an effective method for the diagnosis of carbamazepine-induced drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome in an 8-year-old girl. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:274-277.

- Aouam K, Ben Romdhane F, Loussaief C, et al. Hypersensitivity syndrome induced by anticonvulsants: possible cross-reactivity between carbamazepine and lamotrigine. J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;49:1488-1491.

- Santiago F, Gonçalo M, Vieira R, et al. Epicutaneous patch testing in drug hypersensitivity syndrome (DRESS). Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62:47-53.

- Prevost P, Bédry R, Lacoste D, et al. Hypersensitivity syndrome with olanzapine confirmed by patch tests. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:126-127.

- Hubiche T, Milpied B, Cazeau C, et al. Association of immunologically confirmed delayed drug reaction and human herpesvirus 6 viremia in a pediatric case of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Dermatology. 2011;222:140-141.

- Song WJ, Shim EJ, Kang MG, et al. Severe drug hypersensitivity induced by erdosteine and doxofylline as confirmed by patch and lymphocyte transformation tests: a case report. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2012;22:230-232.

- Lee JH, Park HK, Heo J, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome induced by celecoxib and anti-tuberculosis drugs. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:521-525.

- González-Delgado P, Blanes M, Soriano V, et al. Erythema multiforme to amoxicillin with concurrent infection by Epstein-Barr virus. Allergol Immunopathol. 2006;34:76-78.

- Gonzalo Garijo MA, Pérez Calderón R, de Argila Fernández-Durán D, et al. Cutaneous reactions due to diltiazem and cross reactivity with other calcium channel blockers. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2005;33:238-240.

- Peña AL, Henriquezsantana A, Gonzalez-Seco E, et al. Exudative erythema multiforme induced by hydroxyzine. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:194-195.

- Arakawa Y, Nakai N, Katoh N. Celecoxib-induced erythema multiforme-type drug eruption with a positive patch test. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1185-1188.

- Prieto A, De barrio M, Pérez C, et al. Piroxicam-induced erythema multiforme. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:263.

- Dalmau J, Serra-baldrich E, Roé E, et al. Use of patch test in fixed drug eruption due to metamizole (Nolotil). Contact Dermatitis. 2006;54:127-128.

- Gastaminza G, Anda M, Audicana MT, et al. Fixed-drug eruption due to metronidazole with positive topical provocation. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:36.

- Bellini V, Stingeni L, Lisi P. Multifocal fixed drug eruption due to celecoxib. Dermatitis. 2009;20:174-176.

- García CM, Carmena R, García R, et al. Fixed drug eruption from ticlopidine, with positive lesional patch test. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44:40-41.

- Cruz MJ, Duarte AF, Baudrier T, et al. Lichenoid drug eruption induced by misoprostol. Contact Dermatitis. 2009;61:240-242.

- Alanko K. Patch testing in cutaneous reactions caused by carbamazepine. Contact Dermatitis. 1993;29:254-257.

- Grob M, Scheidegger P, Wüthrich B. Allergic skin reaction to celecoxib. Dermatology. 2000;201:383.

- Alonso JC, Ortega JD, Gonzalo MJ. Cutaneous reaction to oral celecoxib with positive patch test. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:48-49.

- Fernandes B, Brites M, Gonçalo M, et al. Maculopapular eruption from sertraline with positive patch tests. Contact Dermatitis. 2000;42:287.

- Häusermann P, Harr T, Bircher AJ. Baboon syndrome resulting from systemic drugs: is there strife between SDRIFE and allergic contact dermatitis syndrome? Contact Dermatitis. 2004;51:297-310.

- Klein CE, Trautmann A, Zillikens D, et al. Patch testing in an unusual case of toxic epidermal necrolysis. Contact Dermatitis. 1996;35:175-176.

- Swerlick RA, Campbell CF. Medication dyes as a source of drug allergy. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:99-102.

- Guin JD. Patch testing to FD&C and D&C dyes. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:217-218.

- Lowther A, McCormick T, Nedorost S. Systemic contact dermatitis from propylene glycol. Dermatitis. 2008;19:105-108.

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Systemic contact dermatitis to corticosteroids. Allergy. 2012;67:1580-1585.

- Baeck M, Goossens A. Immediate and delayed allergic hypersensitivity to corticosteroids: practical guidelines. Contact Dermatitis. 2012;66:38-45.

- Basedow S, Eigelshoven S, Homey B. Immediate and delayed hypersensitivity to corticosteroids. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:885-888.

- Johansen JD, Aalto-korte K, Agner T, et al. European Society of Contact Dermatitis guideline for diagnostic patch testing—recommendations on best practice. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73:195-221.

- Mirakian R, Ewan PW, Durham SR, et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of drug allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:43-61.

- Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:259-273.

Adverse drug reactions account for 3% to 6% of hospital admissions in the United States and occur in 10% to 15% of hospitalized patients.1,2 The most common culprits are antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-12 In most cases, diagnoses are made clinically without diagnostic testing. To identify drug allergies associated with diagnostic testing, one center selected patients with suspected cutaneous drug reactions (2006-2010) for further evaluation.13 Of 612 patients who were evaluated, 141 had a high suspicion of drug allergy and were included in the analysis. The excluded patients had pseudoallergic reactions, reactive exanthemas due to infection, histopathologic exclusion of drug allergy, angioedema, or other dermatological conditions such as contact dermatitis and eczema. Of the included patients, 107 were diagnosed with drug reactions, while the remainder had non–drug-related exanthemas or unknown etiology after testing. Identified culprit drugs were predominantly antibiotics (39.8%) and NSAIDs (21.2%); contrast media, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, antimalarials, antifungals, glucocorticoids, antihypertensives, and proton pump inhibitors also were implicated. They were identified with skin prick, intradermal, and patch tests (62.6%); lymphocyte transformation test (17.7%); oral rechallenge (5.6%); or without skin testing (6.5%). One quarter of patients with a high suspicion for drug allergy did not have a confirmed drug eruption in this study. Another study found that 10% to 20% of patients with reported penicillin allergy had confirmation via skin prick testing.14 These findings suggest that confirmation of suspected drug allergy may require more than one diagnostic test.

Tests for Adverse Drug Reactions

The following tests have been shown to aid in the identification of cutaneous drug eruptions: (1) patch tests15-21; (2) intradermal tests14,15,19,20; (3) drug provocation tests15,20; and (4) lymphocyte transformation tests.20 Intradermal or skin prick tests are most useful in urticarial eruptions but can be considered in nonurticarial eruptions with delayed inspection of test sites up to 1 week after testing. Drug provocation tests are considered the gold standard but involve patient risk. Lymphocyte transformation tests use the principle that T lymphocytes proliferate in the presence of drugs to which the patient is sensitized. Patch tests will be discussed in greater detail below. Immunohistochemistry can determine immunologic mechanisms of eruptions but cannot identify causative agents.16,17,22

A retrospective study of patients referred for evaluation of adverse drug reactions between 1996 and 2006 found the collective negative predictive value (NPV)—the percentage of truly negative skin tests based on provocation or substitution testing—of cutaneous drug tests including patch, prick, and intradermal tests to be 89.6% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-93.3%).23 The NPVs of each test were not reported. Patients with negative cutaneous tests had subsequent oral rechallenge or substitution testing with medication from the same drug class.23 Another study16 found the NPV of patch testing to be at least 79% after review of data from other studies using patch and provocation testing.16,24 These studies suggest that cutaneous testing can be useful, albeit imperfect, in the evaluation and diagnosis of drug allergy.

Review of the Patch Test

Patch tests can be helpful in diagnosis of delayed hypersensitivities.18 Patch testing is most commonly and effectively used to diagnose allergic contact dermatitis, but its utility in other applications, such as diagnosis of cutaneous drug eruptions, has not been extensively studied.

The development of patch tests to diagnose systemic drug allergies is inhibited by the uncertainty of percutaneous drug penetration, a dearth of studies to determine the best test concentrations of active drug in the patch test, and the potential for nonimmunologic contact urticaria upon skin exposure. Furthermore, cutaneous metabolism of many antigens is well documented, but correlation to systemic metabolism often is unknown, which can confound patch test results and lead to false-negative results when the skin’s metabolic capacity does not match the body’s capacity to generate antigens capable of eliciting immunogenic responses.21 Additionally, the method used to suspend and disperse drugs in patch test vehicles is unfamiliar to most pharmacists, and standardized concentrations and vehicles are available only for some medications.25 Studies sufficient to obtain US Food and Drug Administration approval of patch tests for systemic drug eruptions would be costly and therefore prohibitive to investigators. The majority of the literature consists of case reports and data extrapolated from reviews. Patch test results of many drugs have been reported in the literature, with the highest frequencies of positive results associated with anticonvulsants,26 antibiotics, corticosteroids, calcium channel blockers, and benzodiazepines.21

Patch test placement affects the diagnostic value of the test. Placing patch tests on previously involved sites of fixed drug eruptions improves yield over placement on uninvolved skin.27 Placing patch tests on previously involved sites of other drug eruptions such as toxic epidermal necrolysis also may aid in diagnosis, though the literature is sparse.25,26,28

Patch Testing in Drug Eruptions

Morbilliform eruptions account for 48% to 91% of patients with adverse drug reactions.4-6 Other drug eruptions include urticarial eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, lichenoid drug eruption, symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE), erythema multiforme (EM), and systemic contact dermatitis. The Table summarizes reports of positive patch tests with various medications for these drug eruptions.

In general, antimicrobials and NSAIDs were the most implicated drugs with positive patch test results in AGEP, DRESS syndrome, EM, fixed drug eruptions, and morbilliform eruptions. In AGEP, positive results also were reported for other drugs, including terbinafine and morphine.29-38 In fixed drug eruptions, patch testing on involved skin showed positive results to NSAIDs, analgesics, platelet inhibitors, and antimicrobials.27,52-55 Patch testing in DRESS syndrome has shown many positive reactions to antiepileptics and antipsychotics.39-43 One study used patch tests in SDRIFE, reporting positive results with antimicrobials, antineoplastics, decongestants, and glucocorticoids.61 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobials, calcium channel blockers, and histamine antagonists were implicated in EM.47-51 Positive patch tests were seen in morbilliform eruptions with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antiepileptics/benzodiazepines, NSAIDs, and antimicrobials.28,57-60 In toxic epidermal necrolysis, diagnosis with patch testing was made using patches placed on previously involved skin with sulfamethoxazole.62

Systemic Contact Dermatitis

Drugs historically recognized as causing allergic contact dermatitis (eg, topical gentamycin) can cause systemic contact dermatitis, which can be patch tested. In these situations, systemic contact dermatitis may be due to either the active drug or excipients in the medication formulation. Excipients are inactive ingredients in medications that provide a suitable consistency, appearance, or form. Often overlooked as culprits of drug hypersensitivity because they are theoretically inert, excipients are increasingly implicated in drug allergy. Swerlick and Campbell63 described 11 cases in which chronic unexplained pruritus responded to medication changes to avoid coloring agents. The most common culprits were FD&C Blue No. 1 and FD&C Blue No. 2. Patch testing for allergies to dyes can be clinically useful, though a lack of commercially available patch tests makes diagnosis difficult.64

Other excipients can cause cutaneous reactions. Propylene glycol, commonly implicated in allergic contact dermatitis, also can cause cutaneous eruptions upon systemic exposure.65 Corticosteroid-induced systemic contact dermatitis has been reported, though it is less prevalent than allergic contact dermatitis.66 These reactions usually are due to nonmethylated and nonhalogenated corticosteroids including budesonide, cortisone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone.67,68 Patch testing in these situations is complicated by the possibility of false-negative results due to the anti-inflammatory effects of the corticosteroids. Therefore, patch testing should be performed using standardized and not treatment concentrations.

In our clinic, we have anecdotally observed several patients with chronic dermatitis and suspected NSAID allergies have positive patch test results with propylene glycol and not the suspected drug. Excipients encountered in multiple drugs and foods are more likely to present as chronic dermatitis, while active drug ingredients started in hospital settings more often present as acute dermatitis.

Our Experience

We have patch tested a handful of patients with suspected drug eruptions (University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center institutional review board #07-12-27). Medications, excipients, and their concentrations (in % weight per weight) and vehicles that were tested include ibuprofen (10% petrolatum), aspirin (10% petrolatum), hydrochlorothiazide (10% petrolatum), captopril (5% petrolatum), and propylene glycol (30% water or 5% petrolatum). Patch tests were read at 48 and 72 hours and scored according to the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group patch test scoring guidelines.69 Two patients tested for ibuprofen reacted positively only to propylene glycol; the 3 other patients did not react to aspirin, hydrochlorothiazide, and captopril. Overall, we observed no positive patch tests to medications and 2 positive tests to propylene glycol in 5 patients tested (unpublished data).

Areas of Uncertainty

Although tests for immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions to drugs exist as skin prick tests, diagnostic testing for the majority of drug reactions does not exist. Drug allergy diagnosis is made with history and temporality, potentially resulting in unnecessary avoidance of helpful medications. Ideal patch test concentrations and vehicles as well as the sensitivity and specificity of these tests are unknown.

Guidelines From Professional Societies

Drug allergy testing guidelines are available from the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology70 and American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.71 The guidelines recommend diagnosis by history and temporality, and it is stated that patch testing is potentially useful in maculopapular rashes, AGEP, fixed drug eruptions, and DRESS syndrome.

Conclusion

Case reports in the literature suggest the utility of patch testing in some drug allergies. We suggest testing excipients such as propylene glycol and benzoic acid to rule out systemic contact dermatitis when patch testing with active drugs to confirm cause of suspected adverse cutaneous reactions to medications.

Adverse drug reactions account for 3% to 6% of hospital admissions in the United States and occur in 10% to 15% of hospitalized patients.1,2 The most common culprits are antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3-12 In most cases, diagnoses are made clinically without diagnostic testing. To identify drug allergies associated with diagnostic testing, one center selected patients with suspected cutaneous drug reactions (2006-2010) for further evaluation.13 Of 612 patients who were evaluated, 141 had a high suspicion of drug allergy and were included in the analysis. The excluded patients had pseudoallergic reactions, reactive exanthemas due to infection, histopathologic exclusion of drug allergy, angioedema, or other dermatological conditions such as contact dermatitis and eczema. Of the included patients, 107 were diagnosed with drug reactions, while the remainder had non–drug-related exanthemas or unknown etiology after testing. Identified culprit drugs were predominantly antibiotics (39.8%) and NSAIDs (21.2%); contrast media, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, antimalarials, antifungals, glucocorticoids, antihypertensives, and proton pump inhibitors also were implicated. They were identified with skin prick, intradermal, and patch tests (62.6%); lymphocyte transformation test (17.7%); oral rechallenge (5.6%); or without skin testing (6.5%). One quarter of patients with a high suspicion for drug allergy did not have a confirmed drug eruption in this study. Another study found that 10% to 20% of patients with reported penicillin allergy had confirmation via skin prick testing.14 These findings suggest that confirmation of suspected drug allergy may require more than one diagnostic test.

Tests for Adverse Drug Reactions

The following tests have been shown to aid in the identification of cutaneous drug eruptions: (1) patch tests15-21; (2) intradermal tests14,15,19,20; (3) drug provocation tests15,20; and (4) lymphocyte transformation tests.20 Intradermal or skin prick tests are most useful in urticarial eruptions but can be considered in nonurticarial eruptions with delayed inspection of test sites up to 1 week after testing. Drug provocation tests are considered the gold standard but involve patient risk. Lymphocyte transformation tests use the principle that T lymphocytes proliferate in the presence of drugs to which the patient is sensitized. Patch tests will be discussed in greater detail below. Immunohistochemistry can determine immunologic mechanisms of eruptions but cannot identify causative agents.16,17,22

A retrospective study of patients referred for evaluation of adverse drug reactions between 1996 and 2006 found the collective negative predictive value (NPV)—the percentage of truly negative skin tests based on provocation or substitution testing—of cutaneous drug tests including patch, prick, and intradermal tests to be 89.6% (95% confidence interval, 85.9%-93.3%).23 The NPVs of each test were not reported. Patients with negative cutaneous tests had subsequent oral rechallenge or substitution testing with medication from the same drug class.23 Another study16 found the NPV of patch testing to be at least 79% after review of data from other studies using patch and provocation testing.16,24 These studies suggest that cutaneous testing can be useful, albeit imperfect, in the evaluation and diagnosis of drug allergy.

Review of the Patch Test

Patch tests can be helpful in diagnosis of delayed hypersensitivities.18 Patch testing is most commonly and effectively used to diagnose allergic contact dermatitis, but its utility in other applications, such as diagnosis of cutaneous drug eruptions, has not been extensively studied.

The development of patch tests to diagnose systemic drug allergies is inhibited by the uncertainty of percutaneous drug penetration, a dearth of studies to determine the best test concentrations of active drug in the patch test, and the potential for nonimmunologic contact urticaria upon skin exposure. Furthermore, cutaneous metabolism of many antigens is well documented, but correlation to systemic metabolism often is unknown, which can confound patch test results and lead to false-negative results when the skin’s metabolic capacity does not match the body’s capacity to generate antigens capable of eliciting immunogenic responses.21 Additionally, the method used to suspend and disperse drugs in patch test vehicles is unfamiliar to most pharmacists, and standardized concentrations and vehicles are available only for some medications.25 Studies sufficient to obtain US Food and Drug Administration approval of patch tests for systemic drug eruptions would be costly and therefore prohibitive to investigators. The majority of the literature consists of case reports and data extrapolated from reviews. Patch test results of many drugs have been reported in the literature, with the highest frequencies of positive results associated with anticonvulsants,26 antibiotics, corticosteroids, calcium channel blockers, and benzodiazepines.21

Patch test placement affects the diagnostic value of the test. Placing patch tests on previously involved sites of fixed drug eruptions improves yield over placement on uninvolved skin.27 Placing patch tests on previously involved sites of other drug eruptions such as toxic epidermal necrolysis also may aid in diagnosis, though the literature is sparse.25,26,28

Patch Testing in Drug Eruptions

Morbilliform eruptions account for 48% to 91% of patients with adverse drug reactions.4-6 Other drug eruptions include urticarial eruptions, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, lichenoid drug eruption, symmetric drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema (SDRIFE), erythema multiforme (EM), and systemic contact dermatitis. The Table summarizes reports of positive patch tests with various medications for these drug eruptions.

In general, antimicrobials and NSAIDs were the most implicated drugs with positive patch test results in AGEP, DRESS syndrome, EM, fixed drug eruptions, and morbilliform eruptions. In AGEP, positive results also were reported for other drugs, including terbinafine and morphine.29-38 In fixed drug eruptions, patch testing on involved skin showed positive results to NSAIDs, analgesics, platelet inhibitors, and antimicrobials.27,52-55 Patch testing in DRESS syndrome has shown many positive reactions to antiepileptics and antipsychotics.39-43 One study used patch tests in SDRIFE, reporting positive results with antimicrobials, antineoplastics, decongestants, and glucocorticoids.61 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimicrobials, calcium channel blockers, and histamine antagonists were implicated in EM.47-51 Positive patch tests were seen in morbilliform eruptions with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antiepileptics/benzodiazepines, NSAIDs, and antimicrobials.28,57-60 In toxic epidermal necrolysis, diagnosis with patch testing was made using patches placed on previously involved skin with sulfamethoxazole.62

Systemic Contact Dermatitis

Drugs historically recognized as causing allergic contact dermatitis (eg, topical gentamycin) can cause systemic contact dermatitis, which can be patch tested. In these situations, systemic contact dermatitis may be due to either the active drug or excipients in the medication formulation. Excipients are inactive ingredients in medications that provide a suitable consistency, appearance, or form. Often overlooked as culprits of drug hypersensitivity because they are theoretically inert, excipients are increasingly implicated in drug allergy. Swerlick and Campbell63 described 11 cases in which chronic unexplained pruritus responded to medication changes to avoid coloring agents. The most common culprits were FD&C Blue No. 1 and FD&C Blue No. 2. Patch testing for allergies to dyes can be clinically useful, though a lack of commercially available patch tests makes diagnosis difficult.64

Other excipients can cause cutaneous reactions. Propylene glycol, commonly implicated in allergic contact dermatitis, also can cause cutaneous eruptions upon systemic exposure.65 Corticosteroid-induced systemic contact dermatitis has been reported, though it is less prevalent than allergic contact dermatitis.66 These reactions usually are due to nonmethylated and nonhalogenated corticosteroids including budesonide, cortisone, hydrocortisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone.67,68 Patch testing in these situations is complicated by the possibility of false-negative results due to the anti-inflammatory effects of the corticosteroids. Therefore, patch testing should be performed using standardized and not treatment concentrations.

In our clinic, we have anecdotally observed several patients with chronic dermatitis and suspected NSAID allergies have positive patch test results with propylene glycol and not the suspected drug. Excipients encountered in multiple drugs and foods are more likely to present as chronic dermatitis, while active drug ingredients started in hospital settings more often present as acute dermatitis.

Our Experience

We have patch tested a handful of patients with suspected drug eruptions (University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center institutional review board #07-12-27). Medications, excipients, and their concentrations (in % weight per weight) and vehicles that were tested include ibuprofen (10% petrolatum), aspirin (10% petrolatum), hydrochlorothiazide (10% petrolatum), captopril (5% petrolatum), and propylene glycol (30% water or 5% petrolatum). Patch tests were read at 48 and 72 hours and scored according to the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group patch test scoring guidelines.69 Two patients tested for ibuprofen reacted positively only to propylene glycol; the 3 other patients did not react to aspirin, hydrochlorothiazide, and captopril. Overall, we observed no positive patch tests to medications and 2 positive tests to propylene glycol in 5 patients tested (unpublished data).

Areas of Uncertainty

Although tests for immediate-type hypersensitivity reactions to drugs exist as skin prick tests, diagnostic testing for the majority of drug reactions does not exist. Drug allergy diagnosis is made with history and temporality, potentially resulting in unnecessary avoidance of helpful medications. Ideal patch test concentrations and vehicles as well as the sensitivity and specificity of these tests are unknown.

Guidelines From Professional Societies

Drug allergy testing guidelines are available from the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology70 and American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology.71 The guidelines recommend diagnosis by history and temporality, and it is stated that patch testing is potentially useful in maculopapular rashes, AGEP, fixed drug eruptions, and DRESS syndrome.

Conclusion

Case reports in the literature suggest the utility of patch testing in some drug allergies. We suggest testing excipients such as propylene glycol and benzoic acid to rule out systemic contact dermatitis when patch testing with active drugs to confirm cause of suspected adverse cutaneous reactions to medications.

- Arndt KA, Jick H. Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program. JAMA. 1976;235:918-922.

- Bigby M, Jick S, Jick H, et al. Drug-induced cutaneous reactions. a report from the Boston Collaborative Drug Surveillance Program on 15,483 consecutive inpatients, 1975 to 1982. JAMA. 1986;256:3358-3363.

- Fiszenson-Albala F, Auzerie V, Mahe E, et al. A 6-month prospective survey of cutaneous drug reactions in a hospital setting. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1018-1022.

- Thong BY, Leong KP, Tang CY, et al. Drug allergy in a general hospital: results of a novel prospective inpatient reporting system. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:342-347.

- Hunziker T, Kunzi UP, Braunschweig S, et al. Comprehensive hospital drug monitoring (CHDM): adverse skin reactions, a 20-year survey. Allergy. 1997;52:388-393.

- Swanbeck G, Dahlberg E. Cutaneous drug reactions. an attempt to quantitative estimation. Arch Dermatol Res. 1992;284:215-218.