User login

Five-day treatment of ear infections

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

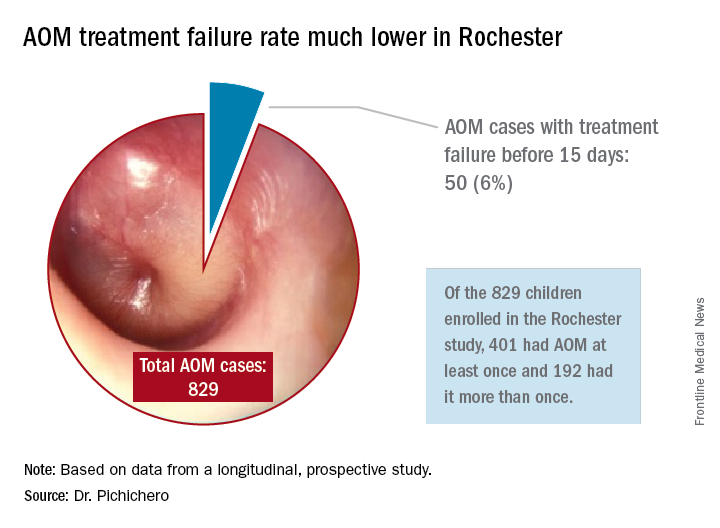

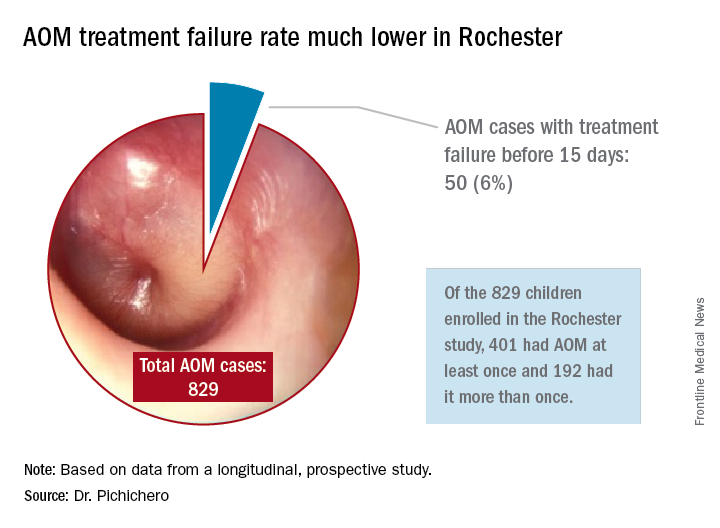

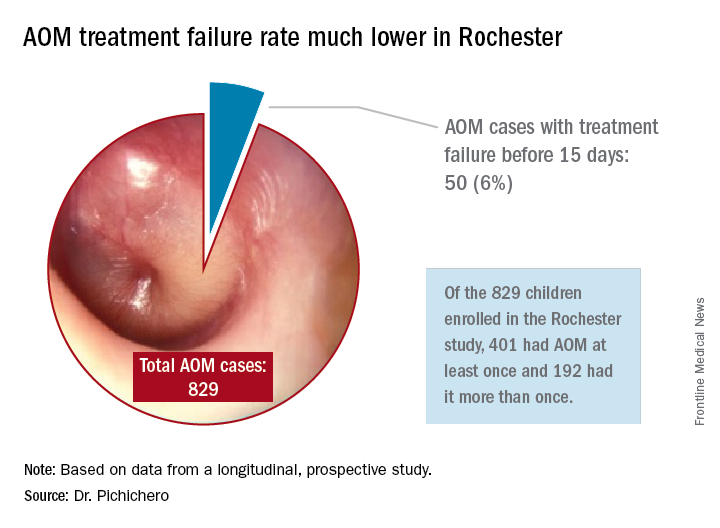

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

In December 2016, the results of a randomized, controlled trial of 5-day vs. 10-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6-23 months was reported by Hoberman et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).1 Predefined criteria for clinical failure were used that considered both symptoms and signs of AOM, assessed on days 12-14 after start of treatment with 5 vs. 10 days of treatment with the antibiotic. The conclusion reached was clear: The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen was 34% vs. 16% in the 10-day group, supporting a preference for the 10-day treatment.

I was surprised. The clinical failure rate for the 5-day regimen seemed very high for treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanate. If it is 34% with amoxicillin/clavulanate, then what would it have been with amoxicillin, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics?

So, why did the systematic review conclude that there was a minimal difference between shortened treatments and the standard 10-day when the NEJM study reported such a striking difference?

In Rochester, N.Y., we have been conducting a longitudinal, prospective study of AOM that is NIH-sponsored to better understand the immune response to AOM, especially in otitis-prone children.3,4 In that study we are treating all children aged 6-23 months with amoxicillin/clavulanate using the same dose as used in the study by Hoberman et al. We have two exceptions: If the child has a second AOM within 30 days of a prior episode or they have an eardrum rupture, we treat for 10 days.5 Our clinical failure rate is 6%. Why is the failure rate in Rochester so much lower than that in Pittsburgh and Bardstown, Ky., where the Hoberman et al. study was done?

One possibility is an important difference in our study design, compared with that of the NEJM study. All the children in our prospective study have a tympanocentesis to confirm the clinical diagnosis, and our research has shown that tympanocentesis results in immediate relief of ear pain and reduces the frequency of antibiotic treatment failure about twofold, compared with children diagnosed and treated by the same physicians in the same clinic practice.6 So, if the tympanocentesis is factored out of the equation, the Rochester clinical failure comes out to 14% for 5-day treatment. Why would the children in Rochester not getting a tympanocentesis, being treated with the same antibiotic, same dose, and same definition of clinical failure, during the same time frame, and having the same bacteria with the same antibiotic resistance rates have a clinical failure rate of 14%, compared with the 34% in the NEJM study?

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 34% fit according to past studies of shortened course antibiotic treatment of AOM? Besides the systematic review and meta-analysis noted above, in many countries outside the United States the 5-day regimen is standard, so, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, that would have been noticeable for sure.8 So, if health care providers were seeing a 34% failure rate, would that not have been noticeable? And would not a 16% failure rate, nearly 1 of 5 cases, be noticeable for children treated for 10 days?

Was there something different about the children who were in the Hoberman et al. study and the children treated in countries outside the United States and in our practice in Rochester? My group has collaborated and published on studies of AOM with the Pittsburgh and Kentucky groups, and we have not found significant site to site differences in outcomes, demonstrating that a population difference is unlikely.9-11

Next question: How does a clinical failure rate of 16% fit according to past studies of 10 days’ antibiotic treatment of AOM? It is on target with the meta-analysis and two other recent studies in the NEJM.12,13 However, if the failure rate was 16% with amoxicillin/clavulanate (which is effective against beta-lactamase–producing Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis, whereas amoxicillin is not), then the predicted failure rate with amoxicillin for 10 days should be double (34%) or triple (51%) had amoxicillin been used as recommended by the AAP in light of the bacterial resistance of otopathogens. That calculation is based on the prevalence of beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis in the Pittsburgh and Kentucky populations, the same prevalence seen in the Rochester population.” 14

So, I conclude that this wonderful study does not convince me to change my practice from standard use of 5-day amoxicillin/clavulanate treatment of AOM. Besides, outside of a study setting, most parents don’t give the full 10-day treatment. They stop when their child seems normal (a few days after starting treatment) and save the remainder of the medicine in the refrigerator for the next illness to save a trip to the doctor. Plus, in this column, I did not even get into the issue of disturbing the microbiome with longer courses of antibiotic treatment, a topic for a future discussion.

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2016 Dec 22;375(25):2446-56.

2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Sep 8;(9):CD001095.

3. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1027-32.

4. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Sep;35(9):1033-9.

5. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):381-7.

6. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013 May;32(5):473-8.

7. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Mar;25(3):211-8.

8. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000 Sep;19(9):929-37.

9. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999 Aug;18(8):741-4.

10. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008 Nov;47(9):901-6.

11. Drugs. 2012 Oct 22;72(15):1991-7.

12. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):105-15.

13. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):116-26.

14. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016 Aug;35(8):901-6.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. He has no disclosures.

Ticagrelor improves platelet reactivity, but not clinical outcomes, in Chinese stroke patients

HOUSTON – The combination of ticagrelor and aspirin reduced the incidence of high on-treatment platelet reactivity compared with clopidogrel plus aspirin in an interim analysis of a trial of patients with minor acute ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack, but was associated with more treatment-limiting side effects.

Significantly more patients taking the ticagrelor combination dropped out because of dyspnea and minor bleeding, Yilong Wang, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Although the ticagrelor combination also prevented a few more recurrent strokes than did clopidogrel plus aspirin, the difference was not statistically significant.

Dr. Wang of Beijing Tiantan Hospital reported the results as part of an interim safety and efficacy analysis of the Platelet Reactivity in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (PRINCE) trial.

“Ticagrelor has been shown to be more effective in acute coronary syndromes than clopidogrel, regardless of genotype, as it is primarily metabolized by the cytochrome P3A4 enzyme,” Dr. Wang said. “In the SOCRATES Asian substudy, we saw a trend of better efficacy in reducing the risk of subsequent vascular events in the ticagrelor group. But there are limited data on the safety and efficacy of ticagrelor, compared with clopidogrel, over background aspirin in stroke patients.”

PRINCE sought to determine the safety of ticagrelor plus aspirin and their effect on platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in Asian patients who had experienced a minor stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA). The 90-day trial is being conducted in 26 centers in China. Its primary endpoints are P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) and the number of patients with high on-treatment platelet reactivity. Secondary outcomes were the incidence of stroke at 90 days, and a composite vascular outcome of any stroke, heart attack, or vascular death within 90 days.

The primary safety outcomes were major and minor bleeding, intracerebral hemorrhage, and total mortality. The study’s researchers hope to enroll 952 patients. The interim analysis was conducted in 476 who have completed the treatment and follow-up period.

The ticagrelor group (237) received an initial loading dose of 180 mg with 100-300 mg aspirin on day 1, followed by 180 mg ticagrelor plus 100 mg aspirin for 21 days. Thereafter, they discontinued the aspirin and continued with 180 mg ticagrelor.

The clopidogrel group (239) received a 300-mg clopidogrel loading dose plus 100-300 mg aspirin on day 1, followed by 75 mg clopidogrel and 100 mg aspirin daily for 21 days. Thereafter they discontinued the aspirin and took 75 mg clopidogrel daily.

Patients were a median of 60 years old. Most (75%) were male. The median blood pressure was 152/90; 60% were hypertensive. About a quarter had diabetes. The qualifying stroke was a TIA in 22%; the rest had a minor ischemic stroke. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 2.

Platelet function was measured at baseline and 2 hours after the initial loading dose, and then again at 24 hours, and at 7, 21, and 90 days.

The baseline PRU was about 250 in each group. Two hours after the loading dose, it dropped significantly more among those taking ticagrelor than in those on clopidogrel (45.7 vs. 222.32). It remained significantly lower at every time point. At 90 days, the PRU favored ticagrelor (69 vs. 175).

Ticagrelor was also associated with significantly less high on-treatment platelet reactivity at every time point. The final separation at 90 days significantly favored ticagrelor (13% vs. 30%).

Clinical endpoints numerically favored ticagrelor, although none of the findings were statistically significant. Any stroke occurred in 4.6% of the ticagrelor group and 7.5% of the clopidogrel group. The rate of ischemic stroke was 4.2% and 6.7%, respectively.

There were three deaths: two in the ticagrelor and one in the clopidogrel group, and three major bleeds in each group. There was no significant difference in minor bleeding or intracerebral hemorrhage. However, ticagrelor was associated with significantly more incidents of minimal bleeding (17% vs. 7%). This difference drove the final, statistically significant doubling of bleeding risk associated with ticagrelor (hazard ratio, 2.26).

There were 49 adverse events leading to dropouts. Most of these were due to bleeding, which was significantly higher in those taking ticagrelor (12 vs. 5 events). Dyspnea was the next-leading cause of study dropout (5 vs. 1 case). The remainder of the dropouts were due to study noncompliance and patient decisions.

The study will continue, Dr. Wang noted.

PRINCE is being sponsored by the Chinese government. Dr. Wang had no financial disclosures. AstraZeneca is providing the study drug at no charge, and is not otherwise involved in the trial.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

HOUSTON – The combination of ticagrelor and aspirin reduced the incidence of high on-treatment platelet reactivity compared with clopidogrel plus aspirin in an interim analysis of a trial of patients with minor acute ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack, but was associated with more treatment-limiting side effects.

Significantly more patients taking the ticagrelor combination dropped out because of dyspnea and minor bleeding, Yilong Wang, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Although the ticagrelor combination also prevented a few more recurrent strokes than did clopidogrel plus aspirin, the difference was not statistically significant.

Dr. Wang of Beijing Tiantan Hospital reported the results as part of an interim safety and efficacy analysis of the Platelet Reactivity in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (PRINCE) trial.

“Ticagrelor has been shown to be more effective in acute coronary syndromes than clopidogrel, regardless of genotype, as it is primarily metabolized by the cytochrome P3A4 enzyme,” Dr. Wang said. “In the SOCRATES Asian substudy, we saw a trend of better efficacy in reducing the risk of subsequent vascular events in the ticagrelor group. But there are limited data on the safety and efficacy of ticagrelor, compared with clopidogrel, over background aspirin in stroke patients.”

PRINCE sought to determine the safety of ticagrelor plus aspirin and their effect on platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in Asian patients who had experienced a minor stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA). The 90-day trial is being conducted in 26 centers in China. Its primary endpoints are P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) and the number of patients with high on-treatment platelet reactivity. Secondary outcomes were the incidence of stroke at 90 days, and a composite vascular outcome of any stroke, heart attack, or vascular death within 90 days.

The primary safety outcomes were major and minor bleeding, intracerebral hemorrhage, and total mortality. The study’s researchers hope to enroll 952 patients. The interim analysis was conducted in 476 who have completed the treatment and follow-up period.

The ticagrelor group (237) received an initial loading dose of 180 mg with 100-300 mg aspirin on day 1, followed by 180 mg ticagrelor plus 100 mg aspirin for 21 days. Thereafter, they discontinued the aspirin and continued with 180 mg ticagrelor.

The clopidogrel group (239) received a 300-mg clopidogrel loading dose plus 100-300 mg aspirin on day 1, followed by 75 mg clopidogrel and 100 mg aspirin daily for 21 days. Thereafter they discontinued the aspirin and took 75 mg clopidogrel daily.

Patients were a median of 60 years old. Most (75%) were male. The median blood pressure was 152/90; 60% were hypertensive. About a quarter had diabetes. The qualifying stroke was a TIA in 22%; the rest had a minor ischemic stroke. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 2.

Platelet function was measured at baseline and 2 hours after the initial loading dose, and then again at 24 hours, and at 7, 21, and 90 days.

The baseline PRU was about 250 in each group. Two hours after the loading dose, it dropped significantly more among those taking ticagrelor than in those on clopidogrel (45.7 vs. 222.32). It remained significantly lower at every time point. At 90 days, the PRU favored ticagrelor (69 vs. 175).

Ticagrelor was also associated with significantly less high on-treatment platelet reactivity at every time point. The final separation at 90 days significantly favored ticagrelor (13% vs. 30%).

Clinical endpoints numerically favored ticagrelor, although none of the findings were statistically significant. Any stroke occurred in 4.6% of the ticagrelor group and 7.5% of the clopidogrel group. The rate of ischemic stroke was 4.2% and 6.7%, respectively.

There were three deaths: two in the ticagrelor and one in the clopidogrel group, and three major bleeds in each group. There was no significant difference in minor bleeding or intracerebral hemorrhage. However, ticagrelor was associated with significantly more incidents of minimal bleeding (17% vs. 7%). This difference drove the final, statistically significant doubling of bleeding risk associated with ticagrelor (hazard ratio, 2.26).

There were 49 adverse events leading to dropouts. Most of these were due to bleeding, which was significantly higher in those taking ticagrelor (12 vs. 5 events). Dyspnea was the next-leading cause of study dropout (5 vs. 1 case). The remainder of the dropouts were due to study noncompliance and patient decisions.

The study will continue, Dr. Wang noted.

PRINCE is being sponsored by the Chinese government. Dr. Wang had no financial disclosures. AstraZeneca is providing the study drug at no charge, and is not otherwise involved in the trial.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

HOUSTON – The combination of ticagrelor and aspirin reduced the incidence of high on-treatment platelet reactivity compared with clopidogrel plus aspirin in an interim analysis of a trial of patients with minor acute ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack, but was associated with more treatment-limiting side effects.

Significantly more patients taking the ticagrelor combination dropped out because of dyspnea and minor bleeding, Yilong Wang, MD, said at the International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association. Although the ticagrelor combination also prevented a few more recurrent strokes than did clopidogrel plus aspirin, the difference was not statistically significant.

Dr. Wang of Beijing Tiantan Hospital reported the results as part of an interim safety and efficacy analysis of the Platelet Reactivity in Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (PRINCE) trial.

“Ticagrelor has been shown to be more effective in acute coronary syndromes than clopidogrel, regardless of genotype, as it is primarily metabolized by the cytochrome P3A4 enzyme,” Dr. Wang said. “In the SOCRATES Asian substudy, we saw a trend of better efficacy in reducing the risk of subsequent vascular events in the ticagrelor group. But there are limited data on the safety and efficacy of ticagrelor, compared with clopidogrel, over background aspirin in stroke patients.”

PRINCE sought to determine the safety of ticagrelor plus aspirin and their effect on platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes in Asian patients who had experienced a minor stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack (TIA). The 90-day trial is being conducted in 26 centers in China. Its primary endpoints are P2Y12 reaction units (PRU) and the number of patients with high on-treatment platelet reactivity. Secondary outcomes were the incidence of stroke at 90 days, and a composite vascular outcome of any stroke, heart attack, or vascular death within 90 days.

The primary safety outcomes were major and minor bleeding, intracerebral hemorrhage, and total mortality. The study’s researchers hope to enroll 952 patients. The interim analysis was conducted in 476 who have completed the treatment and follow-up period.

The ticagrelor group (237) received an initial loading dose of 180 mg with 100-300 mg aspirin on day 1, followed by 180 mg ticagrelor plus 100 mg aspirin for 21 days. Thereafter, they discontinued the aspirin and continued with 180 mg ticagrelor.

The clopidogrel group (239) received a 300-mg clopidogrel loading dose plus 100-300 mg aspirin on day 1, followed by 75 mg clopidogrel and 100 mg aspirin daily for 21 days. Thereafter they discontinued the aspirin and took 75 mg clopidogrel daily.

Patients were a median of 60 years old. Most (75%) were male. The median blood pressure was 152/90; 60% were hypertensive. About a quarter had diabetes. The qualifying stroke was a TIA in 22%; the rest had a minor ischemic stroke. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 2.

Platelet function was measured at baseline and 2 hours after the initial loading dose, and then again at 24 hours, and at 7, 21, and 90 days.

The baseline PRU was about 250 in each group. Two hours after the loading dose, it dropped significantly more among those taking ticagrelor than in those on clopidogrel (45.7 vs. 222.32). It remained significantly lower at every time point. At 90 days, the PRU favored ticagrelor (69 vs. 175).

Ticagrelor was also associated with significantly less high on-treatment platelet reactivity at every time point. The final separation at 90 days significantly favored ticagrelor (13% vs. 30%).

Clinical endpoints numerically favored ticagrelor, although none of the findings were statistically significant. Any stroke occurred in 4.6% of the ticagrelor group and 7.5% of the clopidogrel group. The rate of ischemic stroke was 4.2% and 6.7%, respectively.

There were three deaths: two in the ticagrelor and one in the clopidogrel group, and three major bleeds in each group. There was no significant difference in minor bleeding or intracerebral hemorrhage. However, ticagrelor was associated with significantly more incidents of minimal bleeding (17% vs. 7%). This difference drove the final, statistically significant doubling of bleeding risk associated with ticagrelor (hazard ratio, 2.26).

There were 49 adverse events leading to dropouts. Most of these were due to bleeding, which was significantly higher in those taking ticagrelor (12 vs. 5 events). Dyspnea was the next-leading cause of study dropout (5 vs. 1 case). The remainder of the dropouts were due to study noncompliance and patient decisions.

The study will continue, Dr. Wang noted.

PRINCE is being sponsored by the Chinese government. Dr. Wang had no financial disclosures. AstraZeneca is providing the study drug at no charge, and is not otherwise involved in the trial.

[email protected]

On Twitter @alz_gal

AT THE INTERNATIONAL STROKE CONFERENCE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 90 days, P2Y12 reaction units favored ticagrelor (69 vs. 175).

Data source: The interim analysis of the PRINCE trial comprised 476 patients with minor acute ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack.

Disclosures: PRINCE is being sponsored by the Chinese government. Dr. Wang had no financial disclosures. AstraZeneca is providing the study drug at no charge, and is not otherwise involved in the trial.

President’s report Strategic planning, travel ban, CHEST 2017

Dear Colleagues,

It doesn’t seem possible, but I have just completed the first quarter of my term as your 79th President and recently returned from chairing my first board meeting – a scary experience to be sure. All in all, it went well. We officially offered Steve Welch the position of Executive Vice President, thereby ushering in one of our own to lead the organization. Steve has successfully served as CHEST’s interim EVP/CEO since May 2016, after 22 years of service with this organization, most recently as Senior Vice President of Publications and Digital Content. I am utterly and completely confident in our choice and want you to know he has the full backing of the board, the Past Presidents, and nearly every doctor he has come in contact with.

One of our strategic areas of focus for the past 5 years is how we serve our international members. CHEST is now truly a global organization. Our international membership continues to grow, and that impacts all areas of the College. In 2016, we provided education for more than 4,300 international members through our national meeting and courses provided all around the globe. In addition, the College has, in partnership with Chinese CHEST leadership and ministry of health officials, led the effort to begin the first pulmonary and critical care fellowship training programs in China. This was an amazing undertaking. The first four graduates were introduced and honored at CHEST 2016, and 20 more are scheduled to graduate next year. An additional 25 more fellowship training programs are to start this next year, and the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission recently approved the program as one of only three official fellowship training programs in China. I firmly believe we will look back on this endeavor as one of the greatest accomplishments in our organization’s long and storied history. Countless lives of patients with pulmonary diseases and critical illness are likely to be saved or extended in that country because of this work.

This brings me to CHEST’s position on the travel ban recently imposed and currently on hold in the United States. We, along with 11 other medical societies, sent a letter to the Secretary of Homeland Security underscoring our concern for such a ban, as it could most definitely adversely affect health-care delivery worldwide in ways not previously contemplated. For example, international medical graduates reportedly make up 25% of our physician workforce and provide a disproportionate amount of care to underserved communities. Should we not allow them to come and train here, we could be putting patients in those areas at risk. The ban could result in patients who need specialized health care being denied entrance to the country. We worry that our global physician colleagues will be unable to travel to the United States for educational programs meant to provide them with the tools they need to care for their patients back home. I encourage you to read the full letter if you are interested.

On a brighter note, the program committee is busy planning CHEST 2017, which will be held in Toronto, Oct 28 to Nov 1. Our theme is Team-Based: Patient-Centered. Our advanced practice providers, critical care nurses, and respiratory therapists, among others, will participate in the planning and help shape different aspects of the program. We encourage our physician members to invite a friend, and come and enjoy the meeting. The traditional CHEST program with simulation and interactive, interdisciplinary symposia will be back by popular demand. There will be something in this meeting for everyone. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that we are working closely with the American Board of Internal Medicine on Maintenance of Certification (MOC) and getting credit by using CHEST products, such as CHEST SEEK, e-learning modules, and live learning opportunities. In fact, CHEST 2016 made getting MOC points easy. Much of the program this year will qualify for MOC, and I would encourage you to take advantage of it. For those who I have had the pleasure of working with and hearing from this year, I thank you for your comments, welcome all opinions, and hope to hear from any member who has something CHEST-related on their mind.

Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

President

Dear Colleagues,

It doesn’t seem possible, but I have just completed the first quarter of my term as your 79th President and recently returned from chairing my first board meeting – a scary experience to be sure. All in all, it went well. We officially offered Steve Welch the position of Executive Vice President, thereby ushering in one of our own to lead the organization. Steve has successfully served as CHEST’s interim EVP/CEO since May 2016, after 22 years of service with this organization, most recently as Senior Vice President of Publications and Digital Content. I am utterly and completely confident in our choice and want you to know he has the full backing of the board, the Past Presidents, and nearly every doctor he has come in contact with.

One of our strategic areas of focus for the past 5 years is how we serve our international members. CHEST is now truly a global organization. Our international membership continues to grow, and that impacts all areas of the College. In 2016, we provided education for more than 4,300 international members through our national meeting and courses provided all around the globe. In addition, the College has, in partnership with Chinese CHEST leadership and ministry of health officials, led the effort to begin the first pulmonary and critical care fellowship training programs in China. This was an amazing undertaking. The first four graduates were introduced and honored at CHEST 2016, and 20 more are scheduled to graduate next year. An additional 25 more fellowship training programs are to start this next year, and the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission recently approved the program as one of only three official fellowship training programs in China. I firmly believe we will look back on this endeavor as one of the greatest accomplishments in our organization’s long and storied history. Countless lives of patients with pulmonary diseases and critical illness are likely to be saved or extended in that country because of this work.

This brings me to CHEST’s position on the travel ban recently imposed and currently on hold in the United States. We, along with 11 other medical societies, sent a letter to the Secretary of Homeland Security underscoring our concern for such a ban, as it could most definitely adversely affect health-care delivery worldwide in ways not previously contemplated. For example, international medical graduates reportedly make up 25% of our physician workforce and provide a disproportionate amount of care to underserved communities. Should we not allow them to come and train here, we could be putting patients in those areas at risk. The ban could result in patients who need specialized health care being denied entrance to the country. We worry that our global physician colleagues will be unable to travel to the United States for educational programs meant to provide them with the tools they need to care for their patients back home. I encourage you to read the full letter if you are interested.

On a brighter note, the program committee is busy planning CHEST 2017, which will be held in Toronto, Oct 28 to Nov 1. Our theme is Team-Based: Patient-Centered. Our advanced practice providers, critical care nurses, and respiratory therapists, among others, will participate in the planning and help shape different aspects of the program. We encourage our physician members to invite a friend, and come and enjoy the meeting. The traditional CHEST program with simulation and interactive, interdisciplinary symposia will be back by popular demand. There will be something in this meeting for everyone. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that we are working closely with the American Board of Internal Medicine on Maintenance of Certification (MOC) and getting credit by using CHEST products, such as CHEST SEEK, e-learning modules, and live learning opportunities. In fact, CHEST 2016 made getting MOC points easy. Much of the program this year will qualify for MOC, and I would encourage you to take advantage of it. For those who I have had the pleasure of working with and hearing from this year, I thank you for your comments, welcome all opinions, and hope to hear from any member who has something CHEST-related on their mind.

Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

President

Dear Colleagues,

It doesn’t seem possible, but I have just completed the first quarter of my term as your 79th President and recently returned from chairing my first board meeting – a scary experience to be sure. All in all, it went well. We officially offered Steve Welch the position of Executive Vice President, thereby ushering in one of our own to lead the organization. Steve has successfully served as CHEST’s interim EVP/CEO since May 2016, after 22 years of service with this organization, most recently as Senior Vice President of Publications and Digital Content. I am utterly and completely confident in our choice and want you to know he has the full backing of the board, the Past Presidents, and nearly every doctor he has come in contact with.

One of our strategic areas of focus for the past 5 years is how we serve our international members. CHEST is now truly a global organization. Our international membership continues to grow, and that impacts all areas of the College. In 2016, we provided education for more than 4,300 international members through our national meeting and courses provided all around the globe. In addition, the College has, in partnership with Chinese CHEST leadership and ministry of health officials, led the effort to begin the first pulmonary and critical care fellowship training programs in China. This was an amazing undertaking. The first four graduates were introduced and honored at CHEST 2016, and 20 more are scheduled to graduate next year. An additional 25 more fellowship training programs are to start this next year, and the Chinese National Health and Family Planning Commission recently approved the program as one of only three official fellowship training programs in China. I firmly believe we will look back on this endeavor as one of the greatest accomplishments in our organization’s long and storied history. Countless lives of patients with pulmonary diseases and critical illness are likely to be saved or extended in that country because of this work.

This brings me to CHEST’s position on the travel ban recently imposed and currently on hold in the United States. We, along with 11 other medical societies, sent a letter to the Secretary of Homeland Security underscoring our concern for such a ban, as it could most definitely adversely affect health-care delivery worldwide in ways not previously contemplated. For example, international medical graduates reportedly make up 25% of our physician workforce and provide a disproportionate amount of care to underserved communities. Should we not allow them to come and train here, we could be putting patients in those areas at risk. The ban could result in patients who need specialized health care being denied entrance to the country. We worry that our global physician colleagues will be unable to travel to the United States for educational programs meant to provide them with the tools they need to care for their patients back home. I encourage you to read the full letter if you are interested.

On a brighter note, the program committee is busy planning CHEST 2017, which will be held in Toronto, Oct 28 to Nov 1. Our theme is Team-Based: Patient-Centered. Our advanced practice providers, critical care nurses, and respiratory therapists, among others, will participate in the planning and help shape different aspects of the program. We encourage our physician members to invite a friend, and come and enjoy the meeting. The traditional CHEST program with simulation and interactive, interdisciplinary symposia will be back by popular demand. There will be something in this meeting for everyone. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that we are working closely with the American Board of Internal Medicine on Maintenance of Certification (MOC) and getting credit by using CHEST products, such as CHEST SEEK, e-learning modules, and live learning opportunities. In fact, CHEST 2016 made getting MOC points easy. Much of the program this year will qualify for MOC, and I would encourage you to take advantage of it. For those who I have had the pleasure of working with and hearing from this year, I thank you for your comments, welcome all opinions, and hope to hear from any member who has something CHEST-related on their mind.

Gerard A. Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

President

Cosmetic Treatments for Skin of Color: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Update on Confocal Microscopy and Skin Cancer Imaging: Report from the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Lung cancer pathways reduce cost of care without compromising outcomes

ORLANDO – Implementation of clinical pathways aimed at improving appropriate, evidence-based care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) reduces costs without negatively affecting survival, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s experience suggests.

“At Dana-Farber ... we have looked toward pathways as a potential tool to help manage complexity and resource utilization,” senior author David M. Jackman, MD, explained at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. “We see pathways as a patient-centered platform that provides real-time decision-making support across the continuum of cancer care. We think that these should be based on preemptive decision making, reflect current standards of care, incorporate feedback from which we can learn from our practice patterns, and support clinical research.”

After the customized Dana-Farber Lung Pathways were implemented in 2014, the cost of outpatient care per patient in the first year after diagnosis fell by about $17,000, or 25%, primarily driven by reduced use of antineoplastic agents, according to data reported at the symposium and simultaneously published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 Mar 4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.021741). Meanwhile, median survival remained at about 11 months, even trending slightly upward.

“Frankly, I’d like to think that we were delivering reasonable and expert care prior to 2014, so I did not anticipate that we were going to see a major change in terms of improvement in survival. But it is important for us to make sure that as we implemented Pathways, there was certainly no decrease in such care,”said Dr. Jackman, medical director of Clinical Pathways at Dana-Farber and an assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

He and his colleagues plan to expand Pathways to cover the full spectrum of cancer care at their center, encompassing medical, radiation, and surgical oncology, he said.

“We also think that pathways can have a major impact on things like symptom management and survivorship care,” he added. “And as we work to embed all of our trials within our Pathways system, and as we push to have our trials in our satellites and in our network affiliates, we hope that this combination of activity can help move us from being not just a good care network, but also a research network.”

The pathways will still have to address some of the thornier issues related to the value of care, Dr. Jackman acknowledged “It’s incredibly easy for us to look at two equivalent therapies in terms of toxicity and efficacy and pick the cheaper one. The harder conversations are to come, that is, what if something is x dollars more expensive and only improves things by a small number of months, is it really worth it?

“Finally, we hope that pathways can be an area for innovation, not used solely to manage costs and to make decisions based on yesteryear, but also to help us move forward and to be the watering hole where everybody comes, as we build out our system that is looking granularly at genomics in order to help match patients with trial opportunities, and for researchers, to help them find specific patients for their trials,” he said. “Pathways can potentially be the nexus where everyone comes and where doctors are informed in real time about opportunities for their patients.”

More evidence of benefit

The Dana-Farber study adds to others showing that the benefits of pathways are real and reproducible, according to invited discussant Thomas J. Smith, MD, professor of oncology and palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

“More importantly, I think, for patients, who are getting hit with these bills and might have a 20% copay, it’s going to reduce their copays and for all the right reasons,” Dr. Smith concluded.

Pathways development

In developing the pathways, Dana-Farber began with lung cancer in part because the center sees a high volume of patients with the disease. In addition, decision making for this malignancy is complex, and there was considerable variation in oncologists’ practices.

“Our platform exists as an independent web-based system that currently lives outside of our EMR. Physicians can access this in real time, in the clinic room with the patient if they so choose,” Dr. Jackman explained. “From our EMR, we are flagged every time a provider orders a new start [of therapy], whether it’s IV chemo, oral chemo, or hormonal therapy. From our vendor, we receive granular treatment decision information made within the pathways system – information about the provider and site, information about the patients, their disease, and the line of therapy, as well as other important factors that drive decision making. Finally, from our clinical trials system interface, we can confirm trial enrollment data.”

Oncologists are free to leave the suggested pathway if their clinical judgment favors an alternate course, according to Dr. Jackman.

“We always want our physicians to feel comfortable treating the patients in front of them however they see best fit. If that means an off-pathway therapy, we want them to have the freedom to do that,” he said. “But we think one of the major tools of the pathways is to help capture the reasons why. So if they think it’s warranted and appropriate, go ahead, go off pathway, but tell us why you are doing it so we can learn from it.”

Using Pathways has not proved burdensome, according to Dr. Jackman. Navigating through the system requires about a minute or two, and use is required only when a patient is starting a new therapy, which typically occurs less than once per half-day clinic session.

Study details

In the study, he and colleagues compared costs of care in the first year after diagnosis of stage IV NSCLC between 160 patients treated at Dana-Farber in 2012 (before Pathways implementation) and 210 patients treated there in 2014 (after Pathways implementation).

“It should be noted that because we are a free-standing outpatient cancer center, all of the costs that we were able to gather are intramural and therefore related only to outpatient activities,” he pointed out.

The total annual costs of care per patient, adjusted for potential confounders (age, sex, race, distance to the institute, clinical trial enrollment, and EGFR and ALK status) fell by $17,085 after implementation of Pathways, from $69,122 to $52,037 (P = .01), he reported.

The largest source of cost savings by far, accounting for 73% of the total, was reduced use of antineoplastic agents (chemotherapy, biologics, and other anticancer agents). Cost for this component fell from $44,237 per patient to $31,846 (P less than .01).

“The majority of this savings came through a reduction in the use of what we considered unwarranted use of combination chemotherapy,” Dr. Jackman said. “In the first-line setting, we specifically went after the regimen of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab; based on our interpretation of the PointBreak study, we felt that that regimen did not bring additional efficacy but did essentially double drug costs. In going after that, we reduced not only use of that but also the subsequent use of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab maintenance. In the second-line setting, with the implementation of Pathways, we saw a decrease in the use of inappropriate platinum-based doublet therapy in those patients who had previously progressed on a platinum-based doublet.”

Median overall survival did not decrease and in fact increased slightly, from 10.7 months before Pathways implementation to 11.2 months afterward (P = .08). Corresponding 1-year rates of survival were 52% and 64%.

“We stand on the shoulders of those who came before us, who have also shown savings associated with implementation of pathways,” concluded Dr. Jackman. “But we hope that we add our voice and our data to this argument that pathways, I think, are a reasonable tool as we try to manage complexity and resource utilization. In addition, we do so without impinging upon clinical outcomes.”

The study was limited by its inclusion of only outpatient costs at Dana-Farber, he acknowledged. “You and we would be very interested in being able to know whether our Pathways implementation affected ED [emergency department] visits or hospitalizations. To that end, we are working with some of our regional payers to try to transparently share data around outcomes, costs, and usage, so that we can learn more in this regard.”

Dr. Jackman disclosed that he is an adviser or consultant to Bayer, Celgene, CVS Caremark, Genentech, and Lilly.

ORLANDO – Implementation of clinical pathways aimed at improving appropriate, evidence-based care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) reduces costs without negatively affecting survival, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s experience suggests.

“At Dana-Farber ... we have looked toward pathways as a potential tool to help manage complexity and resource utilization,” senior author David M. Jackman, MD, explained at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. “We see pathways as a patient-centered platform that provides real-time decision-making support across the continuum of cancer care. We think that these should be based on preemptive decision making, reflect current standards of care, incorporate feedback from which we can learn from our practice patterns, and support clinical research.”

After the customized Dana-Farber Lung Pathways were implemented in 2014, the cost of outpatient care per patient in the first year after diagnosis fell by about $17,000, or 25%, primarily driven by reduced use of antineoplastic agents, according to data reported at the symposium and simultaneously published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 Mar 4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.021741). Meanwhile, median survival remained at about 11 months, even trending slightly upward.

“Frankly, I’d like to think that we were delivering reasonable and expert care prior to 2014, so I did not anticipate that we were going to see a major change in terms of improvement in survival. But it is important for us to make sure that as we implemented Pathways, there was certainly no decrease in such care,”said Dr. Jackman, medical director of Clinical Pathways at Dana-Farber and an assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

He and his colleagues plan to expand Pathways to cover the full spectrum of cancer care at their center, encompassing medical, radiation, and surgical oncology, he said.

“We also think that pathways can have a major impact on things like symptom management and survivorship care,” he added. “And as we work to embed all of our trials within our Pathways system, and as we push to have our trials in our satellites and in our network affiliates, we hope that this combination of activity can help move us from being not just a good care network, but also a research network.”

The pathways will still have to address some of the thornier issues related to the value of care, Dr. Jackman acknowledged “It’s incredibly easy for us to look at two equivalent therapies in terms of toxicity and efficacy and pick the cheaper one. The harder conversations are to come, that is, what if something is x dollars more expensive and only improves things by a small number of months, is it really worth it?

“Finally, we hope that pathways can be an area for innovation, not used solely to manage costs and to make decisions based on yesteryear, but also to help us move forward and to be the watering hole where everybody comes, as we build out our system that is looking granularly at genomics in order to help match patients with trial opportunities, and for researchers, to help them find specific patients for their trials,” he said. “Pathways can potentially be the nexus where everyone comes and where doctors are informed in real time about opportunities for their patients.”

More evidence of benefit

The Dana-Farber study adds to others showing that the benefits of pathways are real and reproducible, according to invited discussant Thomas J. Smith, MD, professor of oncology and palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

“More importantly, I think, for patients, who are getting hit with these bills and might have a 20% copay, it’s going to reduce their copays and for all the right reasons,” Dr. Smith concluded.

Pathways development

In developing the pathways, Dana-Farber began with lung cancer in part because the center sees a high volume of patients with the disease. In addition, decision making for this malignancy is complex, and there was considerable variation in oncologists’ practices.

“Our platform exists as an independent web-based system that currently lives outside of our EMR. Physicians can access this in real time, in the clinic room with the patient if they so choose,” Dr. Jackman explained. “From our EMR, we are flagged every time a provider orders a new start [of therapy], whether it’s IV chemo, oral chemo, or hormonal therapy. From our vendor, we receive granular treatment decision information made within the pathways system – information about the provider and site, information about the patients, their disease, and the line of therapy, as well as other important factors that drive decision making. Finally, from our clinical trials system interface, we can confirm trial enrollment data.”

Oncologists are free to leave the suggested pathway if their clinical judgment favors an alternate course, according to Dr. Jackman.

“We always want our physicians to feel comfortable treating the patients in front of them however they see best fit. If that means an off-pathway therapy, we want them to have the freedom to do that,” he said. “But we think one of the major tools of the pathways is to help capture the reasons why. So if they think it’s warranted and appropriate, go ahead, go off pathway, but tell us why you are doing it so we can learn from it.”

Using Pathways has not proved burdensome, according to Dr. Jackman. Navigating through the system requires about a minute or two, and use is required only when a patient is starting a new therapy, which typically occurs less than once per half-day clinic session.

Study details

In the study, he and colleagues compared costs of care in the first year after diagnosis of stage IV NSCLC between 160 patients treated at Dana-Farber in 2012 (before Pathways implementation) and 210 patients treated there in 2014 (after Pathways implementation).

“It should be noted that because we are a free-standing outpatient cancer center, all of the costs that we were able to gather are intramural and therefore related only to outpatient activities,” he pointed out.

The total annual costs of care per patient, adjusted for potential confounders (age, sex, race, distance to the institute, clinical trial enrollment, and EGFR and ALK status) fell by $17,085 after implementation of Pathways, from $69,122 to $52,037 (P = .01), he reported.

The largest source of cost savings by far, accounting for 73% of the total, was reduced use of antineoplastic agents (chemotherapy, biologics, and other anticancer agents). Cost for this component fell from $44,237 per patient to $31,846 (P less than .01).

“The majority of this savings came through a reduction in the use of what we considered unwarranted use of combination chemotherapy,” Dr. Jackman said. “In the first-line setting, we specifically went after the regimen of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab; based on our interpretation of the PointBreak study, we felt that that regimen did not bring additional efficacy but did essentially double drug costs. In going after that, we reduced not only use of that but also the subsequent use of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab maintenance. In the second-line setting, with the implementation of Pathways, we saw a decrease in the use of inappropriate platinum-based doublet therapy in those patients who had previously progressed on a platinum-based doublet.”

Median overall survival did not decrease and in fact increased slightly, from 10.7 months before Pathways implementation to 11.2 months afterward (P = .08). Corresponding 1-year rates of survival were 52% and 64%.

“We stand on the shoulders of those who came before us, who have also shown savings associated with implementation of pathways,” concluded Dr. Jackman. “But we hope that we add our voice and our data to this argument that pathways, I think, are a reasonable tool as we try to manage complexity and resource utilization. In addition, we do so without impinging upon clinical outcomes.”

The study was limited by its inclusion of only outpatient costs at Dana-Farber, he acknowledged. “You and we would be very interested in being able to know whether our Pathways implementation affected ED [emergency department] visits or hospitalizations. To that end, we are working with some of our regional payers to try to transparently share data around outcomes, costs, and usage, so that we can learn more in this regard.”

Dr. Jackman disclosed that he is an adviser or consultant to Bayer, Celgene, CVS Caremark, Genentech, and Lilly.

ORLANDO – Implementation of clinical pathways aimed at improving appropriate, evidence-based care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) reduces costs without negatively affecting survival, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute’s experience suggests.

“At Dana-Farber ... we have looked toward pathways as a potential tool to help manage complexity and resource utilization,” senior author David M. Jackman, MD, explained at a symposium on quality care sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. “We see pathways as a patient-centered platform that provides real-time decision-making support across the continuum of cancer care. We think that these should be based on preemptive decision making, reflect current standards of care, incorporate feedback from which we can learn from our practice patterns, and support clinical research.”

After the customized Dana-Farber Lung Pathways were implemented in 2014, the cost of outpatient care per patient in the first year after diagnosis fell by about $17,000, or 25%, primarily driven by reduced use of antineoplastic agents, according to data reported at the symposium and simultaneously published (J Oncol Pract. 2017 Mar 4. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.021741). Meanwhile, median survival remained at about 11 months, even trending slightly upward.

“Frankly, I’d like to think that we were delivering reasonable and expert care prior to 2014, so I did not anticipate that we were going to see a major change in terms of improvement in survival. But it is important for us to make sure that as we implemented Pathways, there was certainly no decrease in such care,”said Dr. Jackman, medical director of Clinical Pathways at Dana-Farber and an assistant professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

He and his colleagues plan to expand Pathways to cover the full spectrum of cancer care at their center, encompassing medical, radiation, and surgical oncology, he said.

“We also think that pathways can have a major impact on things like symptom management and survivorship care,” he added. “And as we work to embed all of our trials within our Pathways system, and as we push to have our trials in our satellites and in our network affiliates, we hope that this combination of activity can help move us from being not just a good care network, but also a research network.”

The pathways will still have to address some of the thornier issues related to the value of care, Dr. Jackman acknowledged “It’s incredibly easy for us to look at two equivalent therapies in terms of toxicity and efficacy and pick the cheaper one. The harder conversations are to come, that is, what if something is x dollars more expensive and only improves things by a small number of months, is it really worth it?

“Finally, we hope that pathways can be an area for innovation, not used solely to manage costs and to make decisions based on yesteryear, but also to help us move forward and to be the watering hole where everybody comes, as we build out our system that is looking granularly at genomics in order to help match patients with trial opportunities, and for researchers, to help them find specific patients for their trials,” he said. “Pathways can potentially be the nexus where everyone comes and where doctors are informed in real time about opportunities for their patients.”

More evidence of benefit

The Dana-Farber study adds to others showing that the benefits of pathways are real and reproducible, according to invited discussant Thomas J. Smith, MD, professor of oncology and palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore.

“More importantly, I think, for patients, who are getting hit with these bills and might have a 20% copay, it’s going to reduce their copays and for all the right reasons,” Dr. Smith concluded.

Pathways development

In developing the pathways, Dana-Farber began with lung cancer in part because the center sees a high volume of patients with the disease. In addition, decision making for this malignancy is complex, and there was considerable variation in oncologists’ practices.

“Our platform exists as an independent web-based system that currently lives outside of our EMR. Physicians can access this in real time, in the clinic room with the patient if they so choose,” Dr. Jackman explained. “From our EMR, we are flagged every time a provider orders a new start [of therapy], whether it’s IV chemo, oral chemo, or hormonal therapy. From our vendor, we receive granular treatment decision information made within the pathways system – information about the provider and site, information about the patients, their disease, and the line of therapy, as well as other important factors that drive decision making. Finally, from our clinical trials system interface, we can confirm trial enrollment data.”

Oncologists are free to leave the suggested pathway if their clinical judgment favors an alternate course, according to Dr. Jackman.

“We always want our physicians to feel comfortable treating the patients in front of them however they see best fit. If that means an off-pathway therapy, we want them to have the freedom to do that,” he said. “But we think one of the major tools of the pathways is to help capture the reasons why. So if they think it’s warranted and appropriate, go ahead, go off pathway, but tell us why you are doing it so we can learn from it.”

Using Pathways has not proved burdensome, according to Dr. Jackman. Navigating through the system requires about a minute or two, and use is required only when a patient is starting a new therapy, which typically occurs less than once per half-day clinic session.

Study details

In the study, he and colleagues compared costs of care in the first year after diagnosis of stage IV NSCLC between 160 patients treated at Dana-Farber in 2012 (before Pathways implementation) and 210 patients treated there in 2014 (after Pathways implementation).

“It should be noted that because we are a free-standing outpatient cancer center, all of the costs that we were able to gather are intramural and therefore related only to outpatient activities,” he pointed out.

The total annual costs of care per patient, adjusted for potential confounders (age, sex, race, distance to the institute, clinical trial enrollment, and EGFR and ALK status) fell by $17,085 after implementation of Pathways, from $69,122 to $52,037 (P = .01), he reported.

The largest source of cost savings by far, accounting for 73% of the total, was reduced use of antineoplastic agents (chemotherapy, biologics, and other anticancer agents). Cost for this component fell from $44,237 per patient to $31,846 (P less than .01).

“The majority of this savings came through a reduction in the use of what we considered unwarranted use of combination chemotherapy,” Dr. Jackman said. “In the first-line setting, we specifically went after the regimen of carboplatin, pemetrexed, and bevacizumab; based on our interpretation of the PointBreak study, we felt that that regimen did not bring additional efficacy but did essentially double drug costs. In going after that, we reduced not only use of that but also the subsequent use of pemetrexed plus bevacizumab maintenance. In the second-line setting, with the implementation of Pathways, we saw a decrease in the use of inappropriate platinum-based doublet therapy in those patients who had previously progressed on a platinum-based doublet.”

Median overall survival did not decrease and in fact increased slightly, from 10.7 months before Pathways implementation to 11.2 months afterward (P = .08). Corresponding 1-year rates of survival were 52% and 64%.

“We stand on the shoulders of those who came before us, who have also shown savings associated with implementation of pathways,” concluded Dr. Jackman. “But we hope that we add our voice and our data to this argument that pathways, I think, are a reasonable tool as we try to manage complexity and resource utilization. In addition, we do so without impinging upon clinical outcomes.”

The study was limited by its inclusion of only outpatient costs at Dana-Farber, he acknowledged. “You and we would be very interested in being able to know whether our Pathways implementation affected ED [emergency department] visits or hospitalizations. To that end, we are working with some of our regional payers to try to transparently share data around outcomes, costs, and usage, so that we can learn more in this regard.”

Dr. Jackman disclosed that he is an adviser or consultant to Bayer, Celgene, CVS Caremark, Genentech, and Lilly.

AT THE QUALITY CARE SYMPOSIUM

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The annual cost of outpatient care per patient fell by $17,085, mainly because of reduced use of antineoplastic agents, whereas median survival remained at about 11 months.

Data source: A cohort study among patients with newly diagnosed metastatic NSCLC, comparing 160 treated before and 210 treated after pathways implementation.

Disclosures: Dr. Jackman disclosed that he is an adviser or consultant to Bayer, Celgene, CVS Caremark, Genentech, and Lilly.

Book Review: Psychiatrist rejects ‘physician as cog’ model of care

The title of the book, “Passion for Patients,” by Lee H. Beecher, MD, DLFAPA, FASAM, with writer Dave Racer, MLitt (St. Paul, Minn., Alethos Press, 2017), clearly represents Dr. Beecher’s approach to his professional life: His focal interest has been his patients ever since he went to medical school and started a very long and successful practice.

Dr. Beecher’s years of practice encompass many of the changes that the practice of medicine has seen in the last 50 years.

He attended medical school when an office was the place where a physician and his patients would get together to exchange thoughts, feelings, ideas, and plans so that they would eventually work together directly and unencumbered on the same concepts that they share and that they considered crucial to their relationship.

Shortly after Dr. Beecher graduated, Medicaid and Medicare came into medical practice, together with progressive limitations, threats, and a great many unwelcome interlopers, whose mission drastically changed the doctor-patient relationship. No matter how one examines the actions of the numerous new participants – be they auditors, insurance companies, employers, or money managers – one of their main missions was to modify, qualify, re-identify, and limit the interaction between the doctor and the patient.

“What is amazing – and contrary to truth – about the current evolution of medical care reform is its manifold references to safeguarding the best interests of the patient,” Dr. Beecher wrote. “On the contrary, the medical care reformers in current vogue see the physician as but one cog in the production of a specified medical care outcome – a cog that must be greased by evidence-based medicine and managed by analytical applications derived from data, cured in the crucible of number crunching, and controlled by payment systems.”

We live in an age when forces other than medical thinking and practice are trying to define what psychiatrists do, how we do it, and whether our effort is worth being paid for. This has created lack of satisfaction in the exercise of psychiatry, early retirements, and lack of growth in many quarters. When one considers that practically all psychiatric endeavors can be traced to the efforts of devoted practitioners interested in improving the profession, one can see that the future might look bleak because people other than psychiatrists define, quantify, and evaluate the practice of our specialty.

“I escaped from managed care into the practice model that had served so well for decades prior to HMOs, [preferred provider organizations], and other externally controlled practice models,” he wrote. “My patients paid me directly.”

Dr. Beecher is a witness and protester, as well as a thinking innovator, coming to defend patients and physicians at a time when they are under attack from precisely the same forces that were supposed to help and support them.

Throughout his book, Dr. Beecher tells us the story of his many points of disagreement with the intruders and his many arguments in favor of patients and doctors, going back to the beginning of the forces that are controlling and destroying their relationship at this time and advocating principled resistance and a careful search for independence. The reader easily accompanies the author to the points when independence blends with excellence – accepting that neither one exists without the other.

Dr. Muñoz, a former president of the American Psychiatric Association, has written eight books and more than 200 articles about various aspects of psychiatry. He is a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and has a private practice. Dr. Muñoz and Dr. Beecher serve on the Editorial Advisory Board of Clinical Psychiatry News.

The title of the book, “Passion for Patients,” by Lee H. Beecher, MD, DLFAPA, FASAM, with writer Dave Racer, MLitt (St. Paul, Minn., Alethos Press, 2017), clearly represents Dr. Beecher’s approach to his professional life: His focal interest has been his patients ever since he went to medical school and started a very long and successful practice.

Dr. Beecher’s years of practice encompass many of the changes that the practice of medicine has seen in the last 50 years.

He attended medical school when an office was the place where a physician and his patients would get together to exchange thoughts, feelings, ideas, and plans so that they would eventually work together directly and unencumbered on the same concepts that they share and that they considered crucial to their relationship.