User login

QI enthusiast turns QI leader

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.

“I get the greatest fulfillment from the opportunity to be creative … and to implement projects that are important to me and help patients,” he said. “As long as the projects align with organizational goals, I can usually find the support we need to be successful.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.

“I get the greatest fulfillment from the opportunity to be creative … and to implement projects that are important to me and help patients,” he said. “As long as the projects align with organizational goals, I can usually find the support we need to be successful.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: This new series highlights the professional pathways of quality improvement leaders. This month features the story of Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Kevin O’Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, chose a career path in hospital medicine for the reasons that attract many to the specialty – a love of “a little bit of everything, clinically” and the opportunity to problem-solve a diverse range of professional challenges on a daily basis.

“I was frustrated with our internal inefficiencies, and motivated by wanting to provide optimal care to patients,” Dr. O’Leary said, recalling his entry into the world of quality improvement. “It was the first time as a physician that I felt like quality was a problem that I owned – and if anyone was going to address it, it would have to be a hospitalist.”

That epiphany 16 years ago led Dr. O’Leary, now chief of hospital medicine at the same institution, on a path of enacting change. He began volunteering on small improvement projects around the hospital, which led to an invitation to chair the Quality Management Committee in the hospital medicine department. He continued to build his skills by enrolling in Six Sigma training and in Northwestern University’s Master in Healthcare Quality and Patient Safety program.

“That was transformative,” Dr. O’Leary said. “The master’s program, coupled with performance training, changed the trajectory of my career in quality improvement.”

While he encourages anyone with an interest in QI to seek additional training opportunities, he says personal qualities – tenacity, curiosity, and a willingness to collaborate—are better predictors of success. For those wondering how to get started, “look for a niche, an unmet need that is valuable to your organization, and fill it,” he advised. “You don’t have to be an expert in that area, but you can become one.”

Making strong connections within the hospital system is essential. Reach out to the contacts you know, he said, and if they are not the ones to help you solve the problem, they often know who can.

“That’s key to quality improvement success, as well as career success,” he said. “Find a mentor. It might be someone who is more senior within the hospitalist group, in medicine, or even outside the hospital. Meet with them regularly and ask them for feedback on your ideas.”

Newcomers to QI should embrace opportunities to change care and not get discouraged when a project has unintended outcomes.

“Failure is when a team never gets to the point of implementing the intervention or when a team doesn’t know whether the intervention has actually changed results,” he said. “Learning why an intervention isn’t effective can be as valuable as implementing one that is. If every project is successful, it just means that you’re not taking enough risks.”

Dr. O’Leary spends about 25% of his professional time providing clinical care, and another 15% meeting his responsibilities as division chief. He uses the other protected time in his schedule to lead QI and teach QI skills in programs like Northwestern Medicine’s Academy for Quality and Safety Improvement (AQSI).

As a former faculty member in SHM’s Quality and Safety Educator’s Academy (QSEA), he has trained medical educators to develop curricula in quality improvement and patient safety. He says both AQSI and QSEA are especially effective because they encourage interaction, which is valuable to professionals at all levels looking to advance their skill in QI.

“Even in a teaching capacity,” he noted, “what I learned from other faculty and participants in QSEA was critical.”

Residents and junior hospitalists often have the impression that they lack the skills to lead quality initiatives, but Dr. O’Leary says medical school provides the nuts and bolts – analytical skills, statistical knowledge, critical thinking. He encouraged hospitalists to move ahead, even without formal QI training.

“If you have strong interpersonal skills – the willingness to make friends and build connections – you will be successful,” he said.

It’s also an excellent way to learn about the ins and outs of the hospital system and the work of other departments and specialties. Dr. O’Leary especially enjoys that aspect of his work, as well as the ability to address systemic issues that he values.

“I get the greatest fulfillment from the opportunity to be creative … and to implement projects that are important to me and help patients,” he said. “As long as the projects align with organizational goals, I can usually find the support we need to be successful.”

Claudia Stahl is a content manager for the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Marijuana abuse linked to increased MI risk

Washington – Marijuana abuse was independently associated with an eye-opening doubled risk of acute MI in a large, retrospective, age-matched cohort study, Ahmad Tarek Chami, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The link was strongest by far in young adult marijuana abusers, with an adjusted 3.2-fold increased risk of MI in 25- to 29-year-olds with marijuana abuse noted in their medical records, compared with age-matched controls and a 4.56-fold greater risk among the 30- to 34-year-old cannabis abusers, according to Dr. Chami of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

These data constitute a signal warranting further research. Public opinion regarding potheads has undergone a huge shift. Medical and/or recreational marijuana is now legal in 28 states and the District of Columbia. Surveys indicate that, in 2015, 8.3% of Americans aged 12 years and older had used marijuana during the previous month, and 13.5% had used it within the past year.

“Cardiologists and other physicians are more likely than ever before to encounter patients who use marijuana or even ask them to prescribe it,” Dr. Chami said.

The cannabis plant contains more than 60 cannabinoids. Although marijuana is widely prescribed for treatment of nausea, anorexia, neuropathic pain, glaucoma, seizure disorders, and other conditions, the long-term effects of marijuana on the cardiovascular system are largely unknown, he continued.

This ambiguity was the impetus for Dr. Chami’s study. In it, he utilized a database incorporating 26 health care systems across the United States with nearly 50 million patients, which is maintained by Explorys, an 8-year-old Cleveland-based company.

Dr. Chami identified 210,700 patients with cannabis abuse noted in their medical records, covering provider/patient encounters between October 2011 and September 2016. Their mean age was 36.8 years. The abusers were age-matched to 10,395,060 non–marijuana abuser controls.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of MI in this skewed–young patient population was significantly higher than in the marijuana abuser group: 1.28%, compared with 0.89%, for a 44% increase in relative risk.

However, the marijuana abusers also had a significantly higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors than did their non–cannabis abusing counterparts. They were 2.85 times more likely to have hypertension, 1.59 times more likely to be dyslipidemic, and 7.2 times more likely to be cigarette smokers, and they had a 2.8 times greater prevalence of diabetes. Of note, they were also 17.6 times more likely to have been diagnosed with alcohol abuse, and 61 times more likely to abuse cocaine.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, marijuana abuse remained independently associated with a 1.73-fold increased risk of acute MI. Moreover, after eliminating patients with known coronary artery disease, the strongest risk factor for MI, from the analysis, marijuana abuse was independently associated with a twofold increased risk of MI.

This was a retrospective study, one limitation of which was the standard caveat regarding the possibility of unrecognized confounders that couldn’t be taken into account.

Another study limitation is the uncertainty regarding the diagnosis of “cannabis abuser” in patients’ charts. The Explorys cloud-based database relies on ICD codes to capture data. It doesn’t include specific information on how much marijuana a patient who was labeled as an abuser was actually using. This limitation raises an unanswered question: Were young adults who abused marijuana at highest risk for MI because of heavier use, or are younger patients’ coronary arteries somehow more vulnerable to marijuana’s potential adverse cardiovascular effects?

Several audience members called Dr. Chami’s study “very provocative.” Aaron D. Kugelmass, MD, said that the fundamental question in his mind is whether the cardiovascular hazard of marijuana identified in this study is the result of the practice of smoking the raw product, usually associated with illicit marijuana abusers.

Today, legalized marijuana is often consumed in the form of edible products, tinctures, and other derivatives that don’t involve inhalation of smoke. Whether these alternative forms of consumption pose any cardiovascular risk is an important unresolved issue in this era of widespread decriminalization of cannabis, noted Dr. Kugelmass, chief of cardiology and medical director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

Dr. Chami reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

Washington – Marijuana abuse was independently associated with an eye-opening doubled risk of acute MI in a large, retrospective, age-matched cohort study, Ahmad Tarek Chami, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The link was strongest by far in young adult marijuana abusers, with an adjusted 3.2-fold increased risk of MI in 25- to 29-year-olds with marijuana abuse noted in their medical records, compared with age-matched controls and a 4.56-fold greater risk among the 30- to 34-year-old cannabis abusers, according to Dr. Chami of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

These data constitute a signal warranting further research. Public opinion regarding potheads has undergone a huge shift. Medical and/or recreational marijuana is now legal in 28 states and the District of Columbia. Surveys indicate that, in 2015, 8.3% of Americans aged 12 years and older had used marijuana during the previous month, and 13.5% had used it within the past year.

“Cardiologists and other physicians are more likely than ever before to encounter patients who use marijuana or even ask them to prescribe it,” Dr. Chami said.

The cannabis plant contains more than 60 cannabinoids. Although marijuana is widely prescribed for treatment of nausea, anorexia, neuropathic pain, glaucoma, seizure disorders, and other conditions, the long-term effects of marijuana on the cardiovascular system are largely unknown, he continued.

This ambiguity was the impetus for Dr. Chami’s study. In it, he utilized a database incorporating 26 health care systems across the United States with nearly 50 million patients, which is maintained by Explorys, an 8-year-old Cleveland-based company.

Dr. Chami identified 210,700 patients with cannabis abuse noted in their medical records, covering provider/patient encounters between October 2011 and September 2016. Their mean age was 36.8 years. The abusers were age-matched to 10,395,060 non–marijuana abuser controls.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of MI in this skewed–young patient population was significantly higher than in the marijuana abuser group: 1.28%, compared with 0.89%, for a 44% increase in relative risk.

However, the marijuana abusers also had a significantly higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors than did their non–cannabis abusing counterparts. They were 2.85 times more likely to have hypertension, 1.59 times more likely to be dyslipidemic, and 7.2 times more likely to be cigarette smokers, and they had a 2.8 times greater prevalence of diabetes. Of note, they were also 17.6 times more likely to have been diagnosed with alcohol abuse, and 61 times more likely to abuse cocaine.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, marijuana abuse remained independently associated with a 1.73-fold increased risk of acute MI. Moreover, after eliminating patients with known coronary artery disease, the strongest risk factor for MI, from the analysis, marijuana abuse was independently associated with a twofold increased risk of MI.

This was a retrospective study, one limitation of which was the standard caveat regarding the possibility of unrecognized confounders that couldn’t be taken into account.

Another study limitation is the uncertainty regarding the diagnosis of “cannabis abuser” in patients’ charts. The Explorys cloud-based database relies on ICD codes to capture data. It doesn’t include specific information on how much marijuana a patient who was labeled as an abuser was actually using. This limitation raises an unanswered question: Were young adults who abused marijuana at highest risk for MI because of heavier use, or are younger patients’ coronary arteries somehow more vulnerable to marijuana’s potential adverse cardiovascular effects?

Several audience members called Dr. Chami’s study “very provocative.” Aaron D. Kugelmass, MD, said that the fundamental question in his mind is whether the cardiovascular hazard of marijuana identified in this study is the result of the practice of smoking the raw product, usually associated with illicit marijuana abusers.

Today, legalized marijuana is often consumed in the form of edible products, tinctures, and other derivatives that don’t involve inhalation of smoke. Whether these alternative forms of consumption pose any cardiovascular risk is an important unresolved issue in this era of widespread decriminalization of cannabis, noted Dr. Kugelmass, chief of cardiology and medical director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

Dr. Chami reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

Washington – Marijuana abuse was independently associated with an eye-opening doubled risk of acute MI in a large, retrospective, age-matched cohort study, Ahmad Tarek Chami, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

The link was strongest by far in young adult marijuana abusers, with an adjusted 3.2-fold increased risk of MI in 25- to 29-year-olds with marijuana abuse noted in their medical records, compared with age-matched controls and a 4.56-fold greater risk among the 30- to 34-year-old cannabis abusers, according to Dr. Chami of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

These data constitute a signal warranting further research. Public opinion regarding potheads has undergone a huge shift. Medical and/or recreational marijuana is now legal in 28 states and the District of Columbia. Surveys indicate that, in 2015, 8.3% of Americans aged 12 years and older had used marijuana during the previous month, and 13.5% had used it within the past year.

“Cardiologists and other physicians are more likely than ever before to encounter patients who use marijuana or even ask them to prescribe it,” Dr. Chami said.

The cannabis plant contains more than 60 cannabinoids. Although marijuana is widely prescribed for treatment of nausea, anorexia, neuropathic pain, glaucoma, seizure disorders, and other conditions, the long-term effects of marijuana on the cardiovascular system are largely unknown, he continued.

This ambiguity was the impetus for Dr. Chami’s study. In it, he utilized a database incorporating 26 health care systems across the United States with nearly 50 million patients, which is maintained by Explorys, an 8-year-old Cleveland-based company.

Dr. Chami identified 210,700 patients with cannabis abuse noted in their medical records, covering provider/patient encounters between October 2011 and September 2016. Their mean age was 36.8 years. The abusers were age-matched to 10,395,060 non–marijuana abuser controls.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of MI in this skewed–young patient population was significantly higher than in the marijuana abuser group: 1.28%, compared with 0.89%, for a 44% increase in relative risk.

However, the marijuana abusers also had a significantly higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors than did their non–cannabis abusing counterparts. They were 2.85 times more likely to have hypertension, 1.59 times more likely to be dyslipidemic, and 7.2 times more likely to be cigarette smokers, and they had a 2.8 times greater prevalence of diabetes. Of note, they were also 17.6 times more likely to have been diagnosed with alcohol abuse, and 61 times more likely to abuse cocaine.

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for these and other potential confounders, marijuana abuse remained independently associated with a 1.73-fold increased risk of acute MI. Moreover, after eliminating patients with known coronary artery disease, the strongest risk factor for MI, from the analysis, marijuana abuse was independently associated with a twofold increased risk of MI.

This was a retrospective study, one limitation of which was the standard caveat regarding the possibility of unrecognized confounders that couldn’t be taken into account.

Another study limitation is the uncertainty regarding the diagnosis of “cannabis abuser” in patients’ charts. The Explorys cloud-based database relies on ICD codes to capture data. It doesn’t include specific information on how much marijuana a patient who was labeled as an abuser was actually using. This limitation raises an unanswered question: Were young adults who abused marijuana at highest risk for MI because of heavier use, or are younger patients’ coronary arteries somehow more vulnerable to marijuana’s potential adverse cardiovascular effects?

Several audience members called Dr. Chami’s study “very provocative.” Aaron D. Kugelmass, MD, said that the fundamental question in his mind is whether the cardiovascular hazard of marijuana identified in this study is the result of the practice of smoking the raw product, usually associated with illicit marijuana abusers.

Today, legalized marijuana is often consumed in the form of edible products, tinctures, and other derivatives that don’t involve inhalation of smoke. Whether these alternative forms of consumption pose any cardiovascular risk is an important unresolved issue in this era of widespread decriminalization of cannabis, noted Dr. Kugelmass, chief of cardiology and medical director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass.

Dr. Chami reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

At ACC 17

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Marijuana abuse was associated with a twofold increased risk of acute MI independent of cardiovascular risk factor levels.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study including 210,700 patients with cannabis abuse noted in their medical record and 10,395,060 age-matched controls.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

A Game for All Seasons

Sports and sports figures provide both a welcome relief from the stress of dealing with life and death in the ED and memorable ways of characterizing serious health care issues. When the Institute of Medicine issued its 2006 report “Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point,” we thought that a quote about a popular restaurant by the late, great New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra better described the severely overcrowded EDs and ambulance diversion: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In late winter and early spring of this year, after vigorous attempts to repeal/revise the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), a replacement bill was withdrawn immediately prior to a Congressional vote on March 24 due to a lack of support. Seven years earlier, when President Obama also seemed to have little chance of getting the ACA through Congress, we thought that there would be “many more balks before the president and Congress finally pitched a viable health care package to the nation.” Only a month later, however, with the ACA now the law, we suggested that our erroneous prediction was similar to that of “a father who convinces his son to leave for the parking lot during the bottom of the ninth inning of a 3-0 game only to hear the roar of the crowd from the exit ramp as the rookie batter hits a grand-slam home run to win the game.”

In June 2012, when the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of the ACA, many reporters quickly read the Court’s rejection of the first two arguments defending the ACA, and rushed to report that it was dead, without considering that the government had “one more out to go…[the one] casting ACA as a tax—considered to be the weakest player in the lineup—[which] managed to score the winning run to uphold ACA. Game over. Final score: ACA wins 5 to 4.”

But with the 2017 baseball season finally underway, it is a recent football game that provides the perfect paradigm for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs). The New England Patriots were slight favorites to win Super Bowl 51 over the Atlanta Falcons on February 5,and the first quarter ended with no score. But by halftime, Atlanta was leading 21-3. In 50 years of Super Bowls, no team had ever overcome more than a 10-point deficit to win the game, and with a little over 8 minutes left in the third quarter, the deficit had widened even further to 28-3. Then the Patriots began to turn things around. Though the Patriots never led during regulation play, and no Super Bowl had ever gone into overtime, the fourth quarter ended in a 28-28 tie, and the Patriots went on to win 34-28 in overtime.

Coming out of the locker room to play the second half of that game in front of over 111 million viewers must have been a daunting experience for the Patriots, but no more so than the experience depicted in EP/cinematographer Ryan McGarry’s award-winning documentary “Code Black,” in which he shows young EM residents walking through a packed waiting room to begin their shift, realizing that in the next 12 hours, they could never treat all of the ill patients waiting to be seen. But the young residents proceeded to treat one patient after another without ever giving up or losing their idealism, until in the end, they, too, had won the game against all odds.

Many patients arrive in EDs so ill that there is no reasonable expectation any intervention can save them, but we nevertheless try and sometimes succeed in doing the seemingly impossible. It is the type of medicine we have chosen to devote our careers to, and we are no less heroes than were the Patriots on February 5, 2017. Each time we go out to “play ball” in our overcrowded EDs, it is worth remembering another famous Yogi Berra quote: “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Sports and sports figures provide both a welcome relief from the stress of dealing with life and death in the ED and memorable ways of characterizing serious health care issues. When the Institute of Medicine issued its 2006 report “Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point,” we thought that a quote about a popular restaurant by the late, great New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra better described the severely overcrowded EDs and ambulance diversion: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In late winter and early spring of this year, after vigorous attempts to repeal/revise the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), a replacement bill was withdrawn immediately prior to a Congressional vote on March 24 due to a lack of support. Seven years earlier, when President Obama also seemed to have little chance of getting the ACA through Congress, we thought that there would be “many more balks before the president and Congress finally pitched a viable health care package to the nation.” Only a month later, however, with the ACA now the law, we suggested that our erroneous prediction was similar to that of “a father who convinces his son to leave for the parking lot during the bottom of the ninth inning of a 3-0 game only to hear the roar of the crowd from the exit ramp as the rookie batter hits a grand-slam home run to win the game.”

In June 2012, when the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of the ACA, many reporters quickly read the Court’s rejection of the first two arguments defending the ACA, and rushed to report that it was dead, without considering that the government had “one more out to go…[the one] casting ACA as a tax—considered to be the weakest player in the lineup—[which] managed to score the winning run to uphold ACA. Game over. Final score: ACA wins 5 to 4.”

But with the 2017 baseball season finally underway, it is a recent football game that provides the perfect paradigm for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs). The New England Patriots were slight favorites to win Super Bowl 51 over the Atlanta Falcons on February 5,and the first quarter ended with no score. But by halftime, Atlanta was leading 21-3. In 50 years of Super Bowls, no team had ever overcome more than a 10-point deficit to win the game, and with a little over 8 minutes left in the third quarter, the deficit had widened even further to 28-3. Then the Patriots began to turn things around. Though the Patriots never led during regulation play, and no Super Bowl had ever gone into overtime, the fourth quarter ended in a 28-28 tie, and the Patriots went on to win 34-28 in overtime.

Coming out of the locker room to play the second half of that game in front of over 111 million viewers must have been a daunting experience for the Patriots, but no more so than the experience depicted in EP/cinematographer Ryan McGarry’s award-winning documentary “Code Black,” in which he shows young EM residents walking through a packed waiting room to begin their shift, realizing that in the next 12 hours, they could never treat all of the ill patients waiting to be seen. But the young residents proceeded to treat one patient after another without ever giving up or losing their idealism, until in the end, they, too, had won the game against all odds.

Many patients arrive in EDs so ill that there is no reasonable expectation any intervention can save them, but we nevertheless try and sometimes succeed in doing the seemingly impossible. It is the type of medicine we have chosen to devote our careers to, and we are no less heroes than were the Patriots on February 5, 2017. Each time we go out to “play ball” in our overcrowded EDs, it is worth remembering another famous Yogi Berra quote: “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Sports and sports figures provide both a welcome relief from the stress of dealing with life and death in the ED and memorable ways of characterizing serious health care issues. When the Institute of Medicine issued its 2006 report “Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point,” we thought that a quote about a popular restaurant by the late, great New York Yankees catcher Yogi Berra better described the severely overcrowded EDs and ambulance diversion: “Nobody goes there anymore—it’s too crowded.”

In late winter and early spring of this year, after vigorous attempts to repeal/revise the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), a replacement bill was withdrawn immediately prior to a Congressional vote on March 24 due to a lack of support. Seven years earlier, when President Obama also seemed to have little chance of getting the ACA through Congress, we thought that there would be “many more balks before the president and Congress finally pitched a viable health care package to the nation.” Only a month later, however, with the ACA now the law, we suggested that our erroneous prediction was similar to that of “a father who convinces his son to leave for the parking lot during the bottom of the ninth inning of a 3-0 game only to hear the roar of the crowd from the exit ramp as the rookie batter hits a grand-slam home run to win the game.”

In June 2012, when the Supreme Court ruled on the constitutionality of the ACA, many reporters quickly read the Court’s rejection of the first two arguments defending the ACA, and rushed to report that it was dead, without considering that the government had “one more out to go…[the one] casting ACA as a tax—considered to be the weakest player in the lineup—[which] managed to score the winning run to uphold ACA. Game over. Final score: ACA wins 5 to 4.”

But with the 2017 baseball season finally underway, it is a recent football game that provides the perfect paradigm for emergency medicine (EM) and emergency physicians (EPs). The New England Patriots were slight favorites to win Super Bowl 51 over the Atlanta Falcons on February 5,and the first quarter ended with no score. But by halftime, Atlanta was leading 21-3. In 50 years of Super Bowls, no team had ever overcome more than a 10-point deficit to win the game, and with a little over 8 minutes left in the third quarter, the deficit had widened even further to 28-3. Then the Patriots began to turn things around. Though the Patriots never led during regulation play, and no Super Bowl had ever gone into overtime, the fourth quarter ended in a 28-28 tie, and the Patriots went on to win 34-28 in overtime.

Coming out of the locker room to play the second half of that game in front of over 111 million viewers must have been a daunting experience for the Patriots, but no more so than the experience depicted in EP/cinematographer Ryan McGarry’s award-winning documentary “Code Black,” in which he shows young EM residents walking through a packed waiting room to begin their shift, realizing that in the next 12 hours, they could never treat all of the ill patients waiting to be seen. But the young residents proceeded to treat one patient after another without ever giving up or losing their idealism, until in the end, they, too, had won the game against all odds.

Many patients arrive in EDs so ill that there is no reasonable expectation any intervention can save them, but we nevertheless try and sometimes succeed in doing the seemingly impossible. It is the type of medicine we have chosen to devote our careers to, and we are no less heroes than were the Patriots on February 5, 2017. Each time we go out to “play ball” in our overcrowded EDs, it is worth remembering another famous Yogi Berra quote: “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Paraspinous Cervical Nerve Block for Primary Headache

Headaches—pain or discomfort in the head, scalp, or neck—are a very common reason for ED visits.1 In 2011, the World Health Organization estimated that 46.5% of the population in North and South America aged 18 to 65 years old experienced at least one headache within the previous year.1

Migraine is a recurrent headache disorder that afflicts 18% of US women and 9% of US men,2 resulting in at least 1.2 million visits to US EDs annually.1 The economic cost resulting from migraine-related loss of productive time in the US workforce is more than $13 billion per year, most of which is in the form of reduced work productivity.3 Management and treatment for migraine headache in the ED commonly include intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) medications, fluids, or oxygen. While ultimately effective, these methods require nursing care and additional time for posttreatment monitoring, both of which adversely affect patient flow.

In 2006, Mellick et al4 described the safety and effectiveness of paraspinous cervical nerve block (PCNB) to abort migraine headaches. Despite its demonstrated efficacy and safety, a decade later, PCNB is still rarely used. Friedman et al5 ranked peripheral nerve blocks as the fourth step in management suggestions for primary headache.

Case Reports of Headache Patients

We report on seven headache patients we treated in our ED with PCNB who had good-to-complete resolution of pain, suggesting that PCNB is efficacious and can potentially shorten the ED length of stay. This series of seven patients (six female, one male) was a convenience sample of primary headache patients who presented over a 10-month period and were safely and rapidly treated with PCNB (Table).

In each case, the PCNB procedure was explained to the patient and consent was obtained. Each patient was treated with a total of 3 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine injected into the posterior neck according to the method described by Mellick et al.4 Our seven patients achieved an average 5-point reduction in pain on a 10-point pain scale, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worse possible pain.

Other than the provision of medications, no nursing assistance was required. Only one of the patients required further treatment after the PCNB, and none had an adverse reaction. All of the patients reported that their headaches were similar in nature to past headaches. Based on their history and physical examination, none were diagnosed to be experiencing a secondary, more serious cause of headache, and none subsequently returned to our institution with a secondary type of headache.

The Paraspinal Cervical Nerve Block

Paraspinous cervical nerve block requires less time to administer and recovery is shorter than that from IM or IV opioids, sedatives, or neuroleptics. It is an easy technique to teach since it requires bilateral injections.

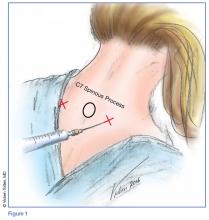

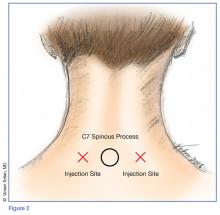

Technique

Prior to the procedure, cleanse the bilateral paravertebral zones surrounding C6 and C7 with chlorhexidine. Next, fill a 3 cc syringe using 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Once the injection is complete, withdraw the needle completely, and compress and massage the injection site to facilitate anesthetic diffusion to surrounding tissues.

Indications

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is an appropriate treatment only for patients who are having a typical episode of chronic, recurring headaches, whose history and physical examination do not suggest the need for any further diagnostic work-up, and who, in the judgment of the treating clinician, require only pain relief.

Contraindications

A patient should not be considered for PCNB if he or she has a new-onset headache, fever, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, meningismus, findings suggestive of meningitis, papilledema, increased intracranial pressure from a space-occupying lesion, recent head trauma with concern for intracranial hemorrhage, or suspicion of an alternate diagnosis.

Efficacy and Patient Response

Paraspinous cervical nerve block has been shown to decrease pain in patients who had failed standard migraine therapy and patients reported no complications. Of the seven patients in this case report, only one patient received opioids in the ED and none received prescriptions for opioids upon discharge for outpatient use.

Mellick and Mellick6 have postulated that pain may be modified due to the PCNB effect on the convergence of the trigeminal nerve with sensory fibers from the upper cervical roots. Since cervical innervation provides feeling to the head and upper neck, blocking this input can ameliorate pain.6

Summary

This series of seven patients provides further evidence of the effectiveness of PCNB in relieving headache symptoms for patients with recurrent, primary headaches when a secondary, more serious cause has been clinically excluded. Each of the seven patients had marked improvement of their pain and required only minimal nursing attention; moreover, all stated they would willingly undergo the procedure for future painful episodes.

Although there were no reported complications, this series is too small to demonstrate complete safety of the procedure. While this report is limited by a small sample size, it demonstrates that this is a quick, effective, and easily learned method of addressing a common ED complaint that obviates the need for parenteral medications and offers a potentially decreased patient length of stay.

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is a promising modality of treatment of ED patients who present with headache and migraine symptoms who do not respond to their outpatient “rescue” therapy. This procedure should be considered as an early treatment for migraine and other primary headaches unless contraindicated.

1. World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders_results.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(9):1065-1072. doi:10.1177/0333102409355601.

3. Chawla J. Migraine headache. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview. Accessed February 9, 2017.

4. Mellick LB, McIlrath ST, Mellick GA. Treatment of headaches in the ED with lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections: a 1-year retrospective review of 417 patients. Headache. 2006;46(9):1441-1449.

5. Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, et al. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:301-309.

6. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections—another treatment option for headaches. http://www.neurologist-doctor.com/images/Mellick_Headache_injections.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

Headaches—pain or discomfort in the head, scalp, or neck—are a very common reason for ED visits.1 In 2011, the World Health Organization estimated that 46.5% of the population in North and South America aged 18 to 65 years old experienced at least one headache within the previous year.1

Migraine is a recurrent headache disorder that afflicts 18% of US women and 9% of US men,2 resulting in at least 1.2 million visits to US EDs annually.1 The economic cost resulting from migraine-related loss of productive time in the US workforce is more than $13 billion per year, most of which is in the form of reduced work productivity.3 Management and treatment for migraine headache in the ED commonly include intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) medications, fluids, or oxygen. While ultimately effective, these methods require nursing care and additional time for posttreatment monitoring, both of which adversely affect patient flow.

In 2006, Mellick et al4 described the safety and effectiveness of paraspinous cervical nerve block (PCNB) to abort migraine headaches. Despite its demonstrated efficacy and safety, a decade later, PCNB is still rarely used. Friedman et al5 ranked peripheral nerve blocks as the fourth step in management suggestions for primary headache.

Case Reports of Headache Patients

We report on seven headache patients we treated in our ED with PCNB who had good-to-complete resolution of pain, suggesting that PCNB is efficacious and can potentially shorten the ED length of stay. This series of seven patients (six female, one male) was a convenience sample of primary headache patients who presented over a 10-month period and were safely and rapidly treated with PCNB (Table).

In each case, the PCNB procedure was explained to the patient and consent was obtained. Each patient was treated with a total of 3 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine injected into the posterior neck according to the method described by Mellick et al.4 Our seven patients achieved an average 5-point reduction in pain on a 10-point pain scale, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worse possible pain.

Other than the provision of medications, no nursing assistance was required. Only one of the patients required further treatment after the PCNB, and none had an adverse reaction. All of the patients reported that their headaches were similar in nature to past headaches. Based on their history and physical examination, none were diagnosed to be experiencing a secondary, more serious cause of headache, and none subsequently returned to our institution with a secondary type of headache.

The Paraspinal Cervical Nerve Block

Paraspinous cervical nerve block requires less time to administer and recovery is shorter than that from IM or IV opioids, sedatives, or neuroleptics. It is an easy technique to teach since it requires bilateral injections.

Technique

Prior to the procedure, cleanse the bilateral paravertebral zones surrounding C6 and C7 with chlorhexidine. Next, fill a 3 cc syringe using 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Once the injection is complete, withdraw the needle completely, and compress and massage the injection site to facilitate anesthetic diffusion to surrounding tissues.

Indications

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is an appropriate treatment only for patients who are having a typical episode of chronic, recurring headaches, whose history and physical examination do not suggest the need for any further diagnostic work-up, and who, in the judgment of the treating clinician, require only pain relief.

Contraindications

A patient should not be considered for PCNB if he or she has a new-onset headache, fever, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, meningismus, findings suggestive of meningitis, papilledema, increased intracranial pressure from a space-occupying lesion, recent head trauma with concern for intracranial hemorrhage, or suspicion of an alternate diagnosis.

Efficacy and Patient Response

Paraspinous cervical nerve block has been shown to decrease pain in patients who had failed standard migraine therapy and patients reported no complications. Of the seven patients in this case report, only one patient received opioids in the ED and none received prescriptions for opioids upon discharge for outpatient use.

Mellick and Mellick6 have postulated that pain may be modified due to the PCNB effect on the convergence of the trigeminal nerve with sensory fibers from the upper cervical roots. Since cervical innervation provides feeling to the head and upper neck, blocking this input can ameliorate pain.6

Summary

This series of seven patients provides further evidence of the effectiveness of PCNB in relieving headache symptoms for patients with recurrent, primary headaches when a secondary, more serious cause has been clinically excluded. Each of the seven patients had marked improvement of their pain and required only minimal nursing attention; moreover, all stated they would willingly undergo the procedure for future painful episodes.

Although there were no reported complications, this series is too small to demonstrate complete safety of the procedure. While this report is limited by a small sample size, it demonstrates that this is a quick, effective, and easily learned method of addressing a common ED complaint that obviates the need for parenteral medications and offers a potentially decreased patient length of stay.

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is a promising modality of treatment of ED patients who present with headache and migraine symptoms who do not respond to their outpatient “rescue” therapy. This procedure should be considered as an early treatment for migraine and other primary headaches unless contraindicated.

Headaches—pain or discomfort in the head, scalp, or neck—are a very common reason for ED visits.1 In 2011, the World Health Organization estimated that 46.5% of the population in North and South America aged 18 to 65 years old experienced at least one headache within the previous year.1

Migraine is a recurrent headache disorder that afflicts 18% of US women and 9% of US men,2 resulting in at least 1.2 million visits to US EDs annually.1 The economic cost resulting from migraine-related loss of productive time in the US workforce is more than $13 billion per year, most of which is in the form of reduced work productivity.3 Management and treatment for migraine headache in the ED commonly include intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) medications, fluids, or oxygen. While ultimately effective, these methods require nursing care and additional time for posttreatment monitoring, both of which adversely affect patient flow.

In 2006, Mellick et al4 described the safety and effectiveness of paraspinous cervical nerve block (PCNB) to abort migraine headaches. Despite its demonstrated efficacy and safety, a decade later, PCNB is still rarely used. Friedman et al5 ranked peripheral nerve blocks as the fourth step in management suggestions for primary headache.

Case Reports of Headache Patients

We report on seven headache patients we treated in our ED with PCNB who had good-to-complete resolution of pain, suggesting that PCNB is efficacious and can potentially shorten the ED length of stay. This series of seven patients (six female, one male) was a convenience sample of primary headache patients who presented over a 10-month period and were safely and rapidly treated with PCNB (Table).

In each case, the PCNB procedure was explained to the patient and consent was obtained. Each patient was treated with a total of 3 cc of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine injected into the posterior neck according to the method described by Mellick et al.4 Our seven patients achieved an average 5-point reduction in pain on a 10-point pain scale, with 0 = no pain and 10 = worse possible pain.

Other than the provision of medications, no nursing assistance was required. Only one of the patients required further treatment after the PCNB, and none had an adverse reaction. All of the patients reported that their headaches were similar in nature to past headaches. Based on their history and physical examination, none were diagnosed to be experiencing a secondary, more serious cause of headache, and none subsequently returned to our institution with a secondary type of headache.

The Paraspinal Cervical Nerve Block

Paraspinous cervical nerve block requires less time to administer and recovery is shorter than that from IM or IV opioids, sedatives, or neuroleptics. It is an easy technique to teach since it requires bilateral injections.

Technique

Prior to the procedure, cleanse the bilateral paravertebral zones surrounding C6 and C7 with chlorhexidine. Next, fill a 3 cc syringe using 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

Once the injection is complete, withdraw the needle completely, and compress and massage the injection site to facilitate anesthetic diffusion to surrounding tissues.

Indications

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is an appropriate treatment only for patients who are having a typical episode of chronic, recurring headaches, whose history and physical examination do not suggest the need for any further diagnostic work-up, and who, in the judgment of the treating clinician, require only pain relief.

Contraindications

A patient should not be considered for PCNB if he or she has a new-onset headache, fever, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, meningismus, findings suggestive of meningitis, papilledema, increased intracranial pressure from a space-occupying lesion, recent head trauma with concern for intracranial hemorrhage, or suspicion of an alternate diagnosis.

Efficacy and Patient Response

Paraspinous cervical nerve block has been shown to decrease pain in patients who had failed standard migraine therapy and patients reported no complications. Of the seven patients in this case report, only one patient received opioids in the ED and none received prescriptions for opioids upon discharge for outpatient use.

Mellick and Mellick6 have postulated that pain may be modified due to the PCNB effect on the convergence of the trigeminal nerve with sensory fibers from the upper cervical roots. Since cervical innervation provides feeling to the head and upper neck, blocking this input can ameliorate pain.6

Summary

This series of seven patients provides further evidence of the effectiveness of PCNB in relieving headache symptoms for patients with recurrent, primary headaches when a secondary, more serious cause has been clinically excluded. Each of the seven patients had marked improvement of their pain and required only minimal nursing attention; moreover, all stated they would willingly undergo the procedure for future painful episodes.

Although there were no reported complications, this series is too small to demonstrate complete safety of the procedure. While this report is limited by a small sample size, it demonstrates that this is a quick, effective, and easily learned method of addressing a common ED complaint that obviates the need for parenteral medications and offers a potentially decreased patient length of stay.

Paraspinous cervical nerve block is a promising modality of treatment of ED patients who present with headache and migraine symptoms who do not respond to their outpatient “rescue” therapy. This procedure should be considered as an early treatment for migraine and other primary headaches unless contraindicated.

1. World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders_results.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(9):1065-1072. doi:10.1177/0333102409355601.

3. Chawla J. Migraine headache. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview. Accessed February 9, 2017.

4. Mellick LB, McIlrath ST, Mellick GA. Treatment of headaches in the ED with lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections: a 1-year retrospective review of 417 patients. Headache. 2006;46(9):1441-1449.

5. Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, et al. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:301-309.

6. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections—another treatment option for headaches. http://www.neurologist-doctor.com/images/Mellick_Headache_injections.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

1. World Health Organization. Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders_results.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

2. Victor TW, Hu X, Campbell JC, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Migraine prevalence by age and sex in the United States: a life-span study. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(9):1065-1072. doi:10.1177/0333102409355601.

3. Chawla J. Migraine headache. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview. Accessed February 9, 2017.

4. Mellick LB, McIlrath ST, Mellick GA. Treatment of headaches in the ED with lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections: a 1-year retrospective review of 417 patients. Headache. 2006;46(9):1441-1449.

5. Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, et al. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:301-309.

6. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Lower cervical intramuscular bupivacaine injections—another treatment option for headaches. http://www.neurologist-doctor.com/images/Mellick_Headache_injections.pdf. Accessed February 9, 2017.

Hypothyroidism-Induced Stercoral Sigmoid Colonic Perforation

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, abdominal pain is the leading reason for ED visits in the United States, with approximately 10 million visits per year.1 Though a large number of presentations are due to nontraumatic causes of abdominal pain, one etiology is among the most time-sensitive and critical diagnoses: acute colonic perforation.

Colonic perforations can be caused by diverticulitis, trauma, malignancy, ulcerative colitis, and other etiologies.2 A rare, yet life-threatening cause of colonic perforation, of which only a few cases have been documented in the literature, is stercoral colonic perforation.2

Regardless of the etiology, the critical actions for any colonic perforation are quick recognition, medical stabilization, and surgical evaluation. This case report highlights the diagnosis and treatment of acute stercoral colonic perforation with peritonitis secondary to hypothyroidism.

Case

A 49-year-old woman with a medical history significant for hypothyroidism presented to the ED for evaluation of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting that started in the early evening of presentation. The patient denied any previous pain or associated symptoms, and said she had a small, hard bowel movement 1 day prior to arrival. She began experiencing mild abdominal pain on the morning of presentation. Her symptoms acutely worsened at approximately 5:00

On physical examination, her vital signs were: heart rate, 156 beats/min; blood pressure, 134/84 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min, and temperature, 97.4°F. The patient appeared ill and diaphoretic, writhing on the stretcher. Abdominal examination was significant for diminished bowel sounds, diffuse abdominal distension, rigidity, and tenderness with light palpation.

Laboratory evaluation showed an elevated lactic acid level of 7.7 mmol/L, a white blood cell count of 7,200 cells/mm3 (segment form, 69.5%), and the following abnormal blood chemistry results: creatinine, 2.08 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 176 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 138 U/L; and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), 225.3 mcIU/mL. Other laboratory results were within normal range. Her electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with a rate of 154 beats/min, a QTc within normal limits, and no ST elevations or depressions.

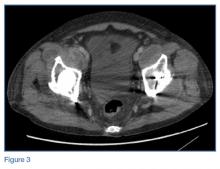

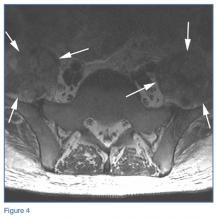

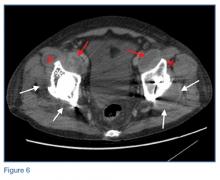

An abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed free air, free fluid, and possibly stool within the abdomen and pelvis. The findings were consistent with a ruptured hollow viscus, possibly a sigmoid colonic perforation. The radiologist also noted hepatomegaly and significant hepatic steatosis. A surgeon was immediately notified and evaluated the patient in the ED. The working diagnosis was stercoral colonic perforation secondary to severe hypothyroidism, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating room for repair.

Intraoperatively, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, which revealed gross fecal contamination of the abdomen. The surgeon noted that there was fecal staining along the serosal surface of the small bowel and throughout the pelvis. There were also large, hard stool balls outside of the colon. The perforation was along the mesenteric surface of the sigmoid just above the rectosigmoid junction.

The abdomen was copiously irrigated, the perforated segment was resected, and a Hartmann colostomy was created. The diagnosis was stercoral sigmoid perforation with peritonitis, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for antibiotic treatment and further medical care, including intravenous (IV) levothyroxine.

She was extubated uneventfully on postoperative day 2, and the acute renal failure improved with supportive care only. Her bowel function slowly returned without complication. She was switched to oral levothyroxine on postoperative day 3. On day 13, she was given strict instructions for continuation of her thyroid medication and close monitoring for postsurgical complications, and was discharged home with appropriate follow-up.

Discussion

Multiple contributing factors can lead to bowel perforation. In this case, severe hypothyroidism with constipation caused a colonic perforation. Our patient had severe constipation that increased intraluminal pressure, causing the bowel wall to become ischemic and subsequently perforate.3 Any disease that causes significant constipation or obstruction of transit could lead to the same catastrophic result.

According to Huang et al,4 as of 2002, fewer than 90 cases of general stercoral bowel perforation had been reported, with no clear age range. However, patients in their mid-50s to mid-60s appear to be the most commonly affected age group.4 Our patient was younger than this age group, making identification of the problem by age alone difficult.

Hypothyroidism

The incidence of hypothyroidism in iodine-replete communities varies between 1% to 2% of the general population.5 The condition is more common in older women, affecting approximately 10% of those over age 65 years. In the United States, the prevalence of biochemical hypothyroidism is 4.6%; however, clinically evident hypothyroidism is present in only 0.3%.6 Common causes for hypothyroidism are listed in the Table.7,8

Myxedema Coma

Untreated, hypothyroidism can lead to potentially fatal conditions, such as myxedema coma, which is characterized by hypothermia, hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression, and altered mental status.7 Severe myxedema coma can result in cardiovascular collapse, and eventual death. Electrocardiography findings of severe hypothyroidism include bradycardia, low-voltage QRS, and widespread T-wave inversions.7 Our patient was tachycardic and did not have any acute findings to suggest myxedema coma.

Treatment for myxedema coma includes supportive care with ventilatory support and pressor support if necessary. Patients should be given IV hydrocortisone, 100 mg, to treat possible adrenal insufficiency and T4, 4 mcg/kg by slow IV infusion.7 Caution should be taken if giving a patient T3 due to the risk of dysrhythmias and myocardial infarction (MI).7 As our patient was not displaying myxedema coma, the surgeon elected not to start IV thyroid replacement to avoid exacerbating the patient’s tachycardia and possibly precipitating an MI intraoperatively.

Conclusion

Our case underscores the importance of promptly recognizing the signs and symptoms of stercoral colonic perforation in patients who present with nontraumatic abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting. Although stercoral colonic perforation is a rare cause of nontraumatic abdominal pain, as with any type of colonic perforation, it constitutes a life-threatening medical emergency. As our case illustrates, prompt diagnosis through a thorough history taking, physical examination, and laboratory and imaging studies is critical to ensure medical stabilization and surgical management to reduce morbidity and mortality.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Table 10. Ten leading principal reasons for emergency department visits, by patient age and sex: United States, 2013. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/2013_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2017.

2. Nam JK, Kim BS, Kim KS, Moon DJ. Clinical analysis of stercoral perforation of the colon. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;55:46-51.

3. Heffernan C, Pachter HL, Megibow AJ, Macari M. Stercoral colitis leading to fatal peritonitis: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(4):1189-1193. doi:10.2214/ajr.184.4.01841189.

4. Huang WS, Wang CS, Hsieh CC, Lin PY, Chin CC, Wang JY. Management of patients with stercoral perforation of the sigmoid colon: Report of five cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(3):500-503.

5. Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado thyroid disease prevalence study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(4):526-534.

6. Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, Flanders WD, et al. Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):489-499.

7. Idrose AM. Hypothyroidism. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 8th Edition. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:1469-1472.

8. Skugor M. Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism. Cleveland Clinic Center for Continuing Education. August 2014. http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/endocrinology/hypothyroidism-and-hyperthyroidism/. Accessed March 3, 2017.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, abdominal pain is the leading reason for ED visits in the United States, with approximately 10 million visits per year.1 Though a large number of presentations are due to nontraumatic causes of abdominal pain, one etiology is among the most time-sensitive and critical diagnoses: acute colonic perforation.

Colonic perforations can be caused by diverticulitis, trauma, malignancy, ulcerative colitis, and other etiologies.2 A rare, yet life-threatening cause of colonic perforation, of which only a few cases have been documented in the literature, is stercoral colonic perforation.2

Regardless of the etiology, the critical actions for any colonic perforation are quick recognition, medical stabilization, and surgical evaluation. This case report highlights the diagnosis and treatment of acute stercoral colonic perforation with peritonitis secondary to hypothyroidism.

Case

A 49-year-old woman with a medical history significant for hypothyroidism presented to the ED for evaluation of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting that started in the early evening of presentation. The patient denied any previous pain or associated symptoms, and said she had a small, hard bowel movement 1 day prior to arrival. She began experiencing mild abdominal pain on the morning of presentation. Her symptoms acutely worsened at approximately 5:00

On physical examination, her vital signs were: heart rate, 156 beats/min; blood pressure, 134/84 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min, and temperature, 97.4°F. The patient appeared ill and diaphoretic, writhing on the stretcher. Abdominal examination was significant for diminished bowel sounds, diffuse abdominal distension, rigidity, and tenderness with light palpation.

Laboratory evaluation showed an elevated lactic acid level of 7.7 mmol/L, a white blood cell count of 7,200 cells/mm3 (segment form, 69.5%), and the following abnormal blood chemistry results: creatinine, 2.08 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase, 176 U/L; alanine aminotransferase, 138 U/L; and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), 225.3 mcIU/mL. Other laboratory results were within normal range. Her electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia with a rate of 154 beats/min, a QTc within normal limits, and no ST elevations or depressions.

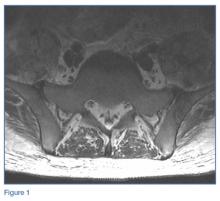

An abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed free air, free fluid, and possibly stool within the abdomen and pelvis. The findings were consistent with a ruptured hollow viscus, possibly a sigmoid colonic perforation. The radiologist also noted hepatomegaly and significant hepatic steatosis. A surgeon was immediately notified and evaluated the patient in the ED. The working diagnosis was stercoral colonic perforation secondary to severe hypothyroidism, and the patient was taken emergently to the operating room for repair.

Intraoperatively, the patient underwent exploratory laparotomy, which revealed gross fecal contamination of the abdomen. The surgeon noted that there was fecal staining along the serosal surface of the small bowel and throughout the pelvis. There were also large, hard stool balls outside of the colon. The perforation was along the mesenteric surface of the sigmoid just above the rectosigmoid junction.

The abdomen was copiously irrigated, the perforated segment was resected, and a Hartmann colostomy was created. The diagnosis was stercoral sigmoid perforation with peritonitis, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for antibiotic treatment and further medical care, including intravenous (IV) levothyroxine.

She was extubated uneventfully on postoperative day 2, and the acute renal failure improved with supportive care only. Her bowel function slowly returned without complication. She was switched to oral levothyroxine on postoperative day 3. On day 13, she was given strict instructions for continuation of her thyroid medication and close monitoring for postsurgical complications, and was discharged home with appropriate follow-up.

Discussion

Multiple contributing factors can lead to bowel perforation. In this case, severe hypothyroidism with constipation caused a colonic perforation. Our patient had severe constipation that increased intraluminal pressure, causing the bowel wall to become ischemic and subsequently perforate.3 Any disease that causes significant constipation or obstruction of transit could lead to the same catastrophic result.

According to Huang et al,4 as of 2002, fewer than 90 cases of general stercoral bowel perforation had been reported, with no clear age range. However, patients in their mid-50s to mid-60s appear to be the most commonly affected age group.4 Our patient was younger than this age group, making identification of the problem by age alone difficult.

Hypothyroidism

The incidence of hypothyroidism in iodine-replete communities varies between 1% to 2% of the general population.5 The condition is more common in older women, affecting approximately 10% of those over age 65 years. In the United States, the prevalence of biochemical hypothyroidism is 4.6%; however, clinically evident hypothyroidism is present in only 0.3%.6 Common causes for hypothyroidism are listed in the Table.7,8

Myxedema Coma

Untreated, hypothyroidism can lead to potentially fatal conditions, such as myxedema coma, which is characterized by hypothermia, hypotension, bradycardia, respiratory depression, and altered mental status.7 Severe myxedema coma can result in cardiovascular collapse, and eventual death. Electrocardiography findings of severe hypothyroidism include bradycardia, low-voltage QRS, and widespread T-wave inversions.7 Our patient was tachycardic and did not have any acute findings to suggest myxedema coma.

Treatment for myxedema coma includes supportive care with ventilatory support and pressor support if necessary. Patients should be given IV hydrocortisone, 100 mg, to treat possible adrenal insufficiency and T4, 4 mcg/kg by slow IV infusion.7 Caution should be taken if giving a patient T3 due to the risk of dysrhythmias and myocardial infarction (MI).7 As our patient was not displaying myxedema coma, the surgeon elected not to start IV thyroid replacement to avoid exacerbating the patient’s tachycardia and possibly precipitating an MI intraoperatively.

Conclusion

Our case underscores the importance of promptly recognizing the signs and symptoms of stercoral colonic perforation in patients who present with nontraumatic abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting. Although stercoral colonic perforation is a rare cause of nontraumatic abdominal pain, as with any type of colonic perforation, it constitutes a life-threatening medical emergency. As our case illustrates, prompt diagnosis through a thorough history taking, physical examination, and laboratory and imaging studies is critical to ensure medical stabilization and surgical management to reduce morbidity and mortality.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, abdominal pain is the leading reason for ED visits in the United States, with approximately 10 million visits per year.1 Though a large number of presentations are due to nontraumatic causes of abdominal pain, one etiology is among the most time-sensitive and critical diagnoses: acute colonic perforation.

Colonic perforations can be caused by diverticulitis, trauma, malignancy, ulcerative colitis, and other etiologies.2 A rare, yet life-threatening cause of colonic perforation, of which only a few cases have been documented in the literature, is stercoral colonic perforation.2

Regardless of the etiology, the critical actions for any colonic perforation are quick recognition, medical stabilization, and surgical evaluation. This case report highlights the diagnosis and treatment of acute stercoral colonic perforation with peritonitis secondary to hypothyroidism.

Case

A 49-year-old woman with a medical history significant for hypothyroidism presented to the ED for evaluation of diffuse abdominal pain, nausea, and nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting that started in the early evening of presentation. The patient denied any previous pain or associated symptoms, and said she had a small, hard bowel movement 1 day prior to arrival. She began experiencing mild abdominal pain on the morning of presentation. Her symptoms acutely worsened at approximately 5:00

On physical examination, her vital signs were: heart rate, 156 beats/min; blood pressure, 134/84 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min, and temperature, 97.4°F. The patient appeared ill and diaphoretic, writhing on the stretcher. Abdominal examination was significant for diminished bowel sounds, diffuse abdominal distension, rigidity, and tenderness with light palpation.